Submitted:

10 January 2025

Posted:

13 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Background

Molecular Insights into Tooth Development

Genomic and Epigenomic Regulation of Tooth Morphogenesis

Cutting-Edge Techniques (e.g., Single-Cell Sequencing) in Studying Molecular Signaling Pathways

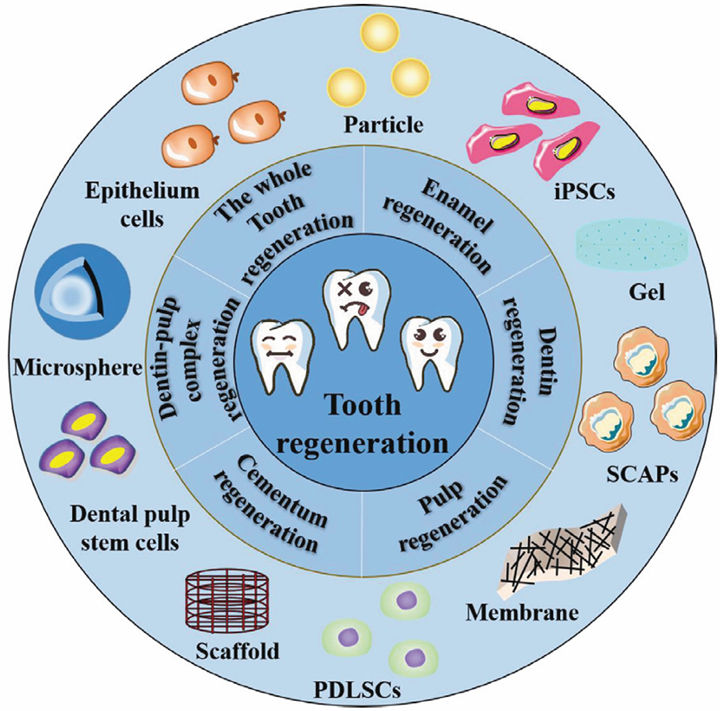

Emerging Frontiers in Stem Cell-Based Tooth Regeneration

Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells (iPSCs) and Their Application in Dental Tissue Engineering

Organoid Cultures and Their Potential in Modeling Tooth Development

Advances in Biomaterials for Tooth Tissue Engineering

Smart Materials, Nanotechnology, and 3D Printing in Scaffold Design

Integration of Bioactive Molecules for Enhanced Regeneration

Bioengineering Approaches for Tooth Replacement

Whole-Tooth Biofabrication: Progress and Challenges

Biofunctionalization and Vascularization of Tooth Constructs

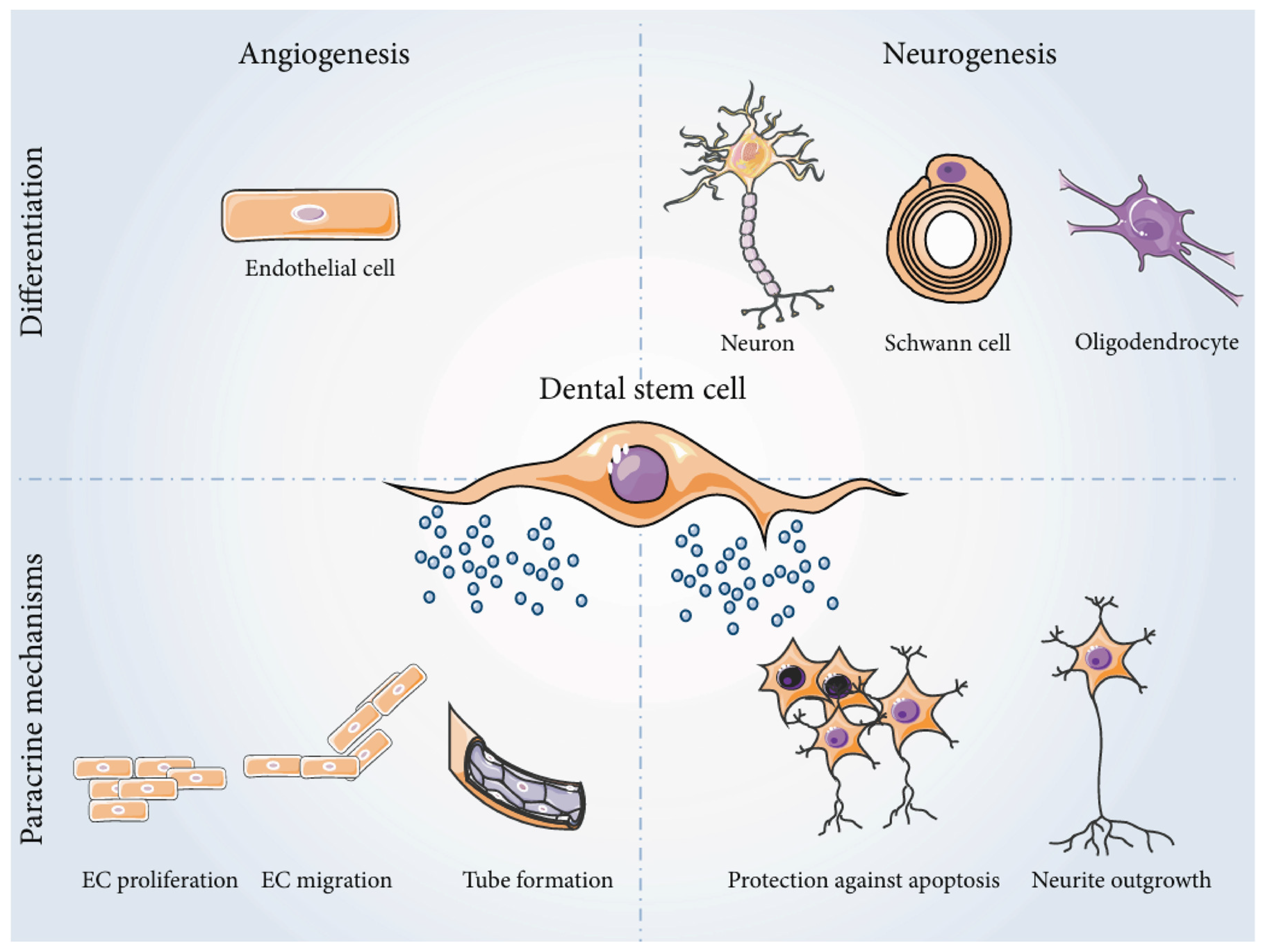

Neurovascular Integration in Tooth Regeneration

Nerve and Blood Vessel Network Formation in Engineered Teeth

Immune Responses and Host-Material Interactions

Immunomodulatory Strategies in Tissue Engineering for Tooth Regeneration

Biomaterial Compatibility and Long-Term Integration with Host Tissues

Conclusions

List of Abbreviations

| iPSCs | Induced pluripotent stem cells |

| DNA | Deoxyribonucleic acid |

| RNAs | Ribonucleic acid |

| BMP | Bone Morphogenetic Protein |

| FGF | Fibroblast Growth Factor |

| SHH | Sonic Hedgehog |

| FGF8 | Fibroblast Growth Factor 8 |

| WNT | Wingless-Type MMTV Integration Site Family |

| BMPR1a | Bone Morphogenetic Protein Receptor Type 1a |

| FGFR2b | Fibroblast Growth Factor Receptor 2b |

| NCCs | Neural Crest Cells |

| MSCs | mesenchymal stem or stromal cells |

| ASF-CM | ameloblasts serum-free conditioned medium |

| BMP4 | Bone Morphogenetic Protein 4 |

| AMBN | Ameloblastin |

| AMGN | Amelogenin |

| CK14 | Cytokeratin 14 |

| sci-RNA-seq | single-cell combinatorial indexing RNA sequencing |

| isAM | Induced secretory ameloblasts |

| 3D | three-dimensional |

| 2D | two-dimensional |

| PSCs | pluripotent stem cells |

| ERM | epithelial cell rests of Malassez |

| HA/TCP | hydroxyapatite/tricalcium phosphate |

| SHED | human exfoliated deciduous teeth |

| DPSCs | dental pulp stem cells |

| SCD-1 | Stearoyl-CoA Desaturase-1 |

| STRO-1 | Stromal precursor antigen-1 |

| CD44 | Cluster of Differentiation 44 |

| CD146 | Cluster of Differentiation 146 |

| pH | power of Hydrogen |

| PGA | polyglycolic acid |

| PLLA | poly-l-lactic acid |

| PLGA | polylactide-co-glycolic acid |

| GFs | Growth factors |

| FDA | Food and Drug administration |

| EMD | enamel matrix derivative |

| rhPDGF-BB | binant human platelet-derived growth factor-BB |

| PCs | platelet concentrates |

| PRP | platelet-rich plasma |

| PRF | platelet-rich fibrin |

| PDLSCs | periodontal ligament stem cells |

| PDGF | Platelet Derived Growth Factor |

| GFSCS | Gingival Fibroblast-Derived Stem Cells |

| SCAPSCS | Stem Cells from Apical papilla |

| BMSCs | Bone Marrow Stromal Cells |

| E12 | embryonic day 12 |

| Epi | Epithelial |

| Mes | mesenchyme |

| RGD | arginine-glycine-aspartic acid |

| VEGF | vascular endothelial growth factor |

| GelMA | gelatin methacrylate |

| mm | millimeter |

| DP-SC | dental pulp stromal stem cells |

| DSC | dental stem cell |

| EGF | epidermal growth factor |

| bFGF | Basic Fibroblast Growth Factor |

| ITS | insulin-transferrin-sodium selenite |

| L-PRF | leukocyte-platelet-rich fibrin |

| BMP-2 | Bone Morphogenetic Protein-2 |

| FGF-2 | Fibroblast Growth Factor-2 |

| TGF-β | transforming growth factor-beta |

Funding

Ethics approval

Consent to participate

Consent for publication

Availability of data and materials

Competing interests

Authors' contributions

Acknowledgments

Declaration Regarding the Use of AI-Assisted Readability Enhancement

References

- Bei, M. Molecular genetics of tooth development. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2009; 19:504–10. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y., Wang, X., Wu, Z., Jia, S., & Wan, M. Epigenetic regulation of dental-derived stem cells and their application in pulp and periodontal regeneration. PeerJ. 2023;11:14550. [CrossRef]

- Jing, J., Feng, J., Yuan, Y., Guo, T., Lei, J., Pei, F., Ho, T., & Chai, Y. Spatiotemporal single-cell regulatory atlas reveals neural crest lineage diversification and cellular function during tooth morphogenesis. Nat Commun. 2022; 13:4803. [CrossRef]

- Radwan, I. A., Rady, D., Abbass, M. M. S., Moshy, S. E., AbuBakr, N., Dörfer, C. E., & El-Sayed, K. M. F. Induced Pluripotent stem cells in dental and nondental tissue regeneration: a review of an unexploited potential. Stem Cells Int.2020;2020: 1941629. [CrossRef]

- Alghadeer, A., Hanson-Drury, S., Patni, A. P., Ehnes, D. D., Zhao, Y. T., Li, Z., Phal, A., Vincent, T. L., Lim, Y. B., O’Day, D. R., Spurrell, C. H., Gogate, A. A., Zhang, H., Devi, A., Wang, Y., Starita, L. M., Doherty, D., Glass, I. A., Shendure, J., . . . Ruohola-Baker, H. Single-cell census of human tooth development enables generation of human enamel. Dev Cell. 2023; 58:2163-2180,9. [CrossRef]

- Hosseinpour, S., Walsh, L. J., & Moharamzadeh, K. Regenerative Approaches in Dentistry. Springer Nature. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Tucker, A. S., & Sharpe, P. T. Molecular genetics of tooth morphogenesis and patterning: the right shape in the right place. J Dent Res. 1999; 78:826-34. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y., Zhao, X., Sun, M., Pei, D., & Li, A. (2022). Deciphering the epigenetic code of stem cells derived from dental tissues. Frontiers in Dental Medicine, 2. [CrossRef]

- Zeng, B., Liu, G., & Huang, J. (2022). DNA methylation and histone modification in dental-derived mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cell Reviews and Reports, 18(8), 2797–2816. [CrossRef]

- Hussain, A., Tebyanian, H., & Khayatan, D. (2022). The role of epigenetic in dental and oral regenerative medicine by different types of dental stem cells: A comprehensive overview. Stem Cells International, 2022, 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Thesleff, I. The genetic basis of tooth development and dental defects. Am J Med Genet A. 2006; 140:2530-5. [CrossRef]

- Hu, X., Zhang, S., Chen, G., Lin, C., Huang, Z., Chen, Y., & Zhang, Y. (2013). Expression of SHH signaling molecules in the developing human primary dentition. BMC Developmental Biology, 13(1). [CrossRef]

- Yu, T., & Klein, O. D. Molecular and cellular mechanisms of tooth development, homeostasis and repair. Development. 2020; 147:184754. [CrossRef]

- Baena, A. R. Y., Casasco, A., & Monti, M. (2022). Hypes and Hopes of Stem Cell Therapies in Dentistry: a Review. Stem Cell Reviews and Reports, 18(4), 1294–1308. [CrossRef]

- Hynes, K., Menichanin, D., Bright, R., Ivanovski, S., Hutmacher, D. W., Gronthos, S., & Bartold, P. M. Induced pluripotent stem cells: a new frontier for stem cells in dentistry. J Dent Res. 2015; 94: 1508-15. [CrossRef]

- Hamano, S., Sugiura, R., Yamashita, D., Tomokiyo, A., Hasegawa, D., & Maeda, H. (2022). Current application of IPS cells in the dental tissue regeneration. Biomedicines, 10(12), 3269. [CrossRef]

- Gao, P., Liu, S., Wang, X., & Ikeya, M. Dental applications of induced pluripotent stem cells and their derivatives. Jpn Dent Sci Rev. 2022; 58:162-71. [CrossRef]

- Cho, Y., Kim, K., Lee, Y., & Seol, Y. (2022). Dental-derived cells for regenerative medicine: stem cells, cell reprogramming, and transdifferentiation. Journal of Periodontal & Implant Science, 52(6), 437. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J., Zhao, Z., Yang, K., & Bai, Y. (2024). Research progress in cell therapy for oral diseases: focus on cell sources and strategies to optimize cell function. Frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotechnology, 12, 1340728. [CrossRef]

- Hermans, F., Hasevoets, S., Vankelecom, H., Bronckaers, A., & Lambrichts, I. (2024). From pluripotent stem cells to organoids and bioprinting: recent advances in dental epithelium and ameloblast models to study tooth biology and regeneration. Stem Cell Reviews and Reports. [CrossRef]

- Liu, L., Liu, Y. F., Zhang, J., Duan, Y. Z., & Jin, Y. Ameloblasts serum-free conditioned medium: bone morphogenic protein 4-induced odontogenic differentiation of mouse induced pluripotent stem cells. J Tissue Eng Regen Med. 2016 Jun;10(6):466-74. [CrossRef]

- Gao, X., Wu, Y., Liao, L., & Tian, W. Oral organoids: progress and challenges. J Dent Res. 2021; 100: 454-63. [CrossRef]

- Mendes-Pinheiro, B., Campos, J., Marote, A., Soares-Cunha, C., Nickels, S. L., Monzel, A. S., ... & Salgado, A. J. (2023). Treating Parkinson’s Disease with Human Bone Marrow Mesenchymal Stem Cell Secretome: A Translational Investigation Using Human Brain Organoids and Different Routes of In Vivo Administration. Cells, 12(21), 2565. [CrossRef]

- Hermans, F., Hemeryck, L., Bueds, C., Pereiro, M. T., Hasevoets, S., Kobayashi, H., Lambrechts, D., Lambrichts, I., Bronckaers, A., & Vankelecom, H. Organoids from mouse molar and incisor as new tools to study tooth-specific biology and development. Stem Cell Reports. 2023; 18:1166–81. [CrossRef]

- Hemeryck, L., Hermans, F., Chappell, J., Kobayashi, H., Lambrechts, D., Lambrichts, I., Bronckaers, A., & Vankelecom, H. Organoids from human tooth showing epithelial stemness phenotype and differentiation potential. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2022; 79:153. [CrossRef]

- Ma, L., Rao, N., Jiang, H., Dai, Y., Wang, C., Yang, H., & Hu, J. (2022). Small extracellular vesicles from dental follicle stem cells provide biochemical cues for periodontal tissue regeneration. Stem Cell Research & Therapy, 13(1). [CrossRef]

- Bi, R., Lyu, P., Song, Y., Li, P., Song, D., Cui, C., & Fan, Y. (2021). Function of dental follicle Progenitor/Stem cells and their potential in regenerative Medicine: From mechanisms to applications. Biomolecules, 11(7), 997. [CrossRef]

- Fu, Z., Zhuang, Y., Cui, J., Sheng, R., Tomás, H., Rodrigues, J.,... & Lin, K. Development and challenges of cells-and materials-based tooth regeneration. Eng Regen.2022; 3:163-81. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y., & Chen, Y. Bioengineering of a human whole tooth: progress and challenge. Cell Regen.2014; 3:8. [CrossRef]

- Smith, E. E., & Yelick, P. C. Progress in bioengineered whole tooth research: from bench to dental patient chair. Curr Oral Health Rep. 2016; 3:302-8. [CrossRef]

- Horst, O. V., Chavez, M. G., Jheon, A. H., Desai, T. A., & Klein, O. D. (2012). Stem cell and biomaterials research in dental tissue engineering and regeneration. Dental Clinics of North America/the Dental Clinics of North America, 56(3), 495–520. [CrossRef]

- EzEldeen, M., Moroni, L., Nejad, Z. M., Jacobs, R., & Mota, C. Biofabrication of engineered dento-alveolar tissue. Biomater Adv. 2023; :148:213371. [CrossRef]

- Lymperi, S., Ligoudistianou, C., Taraslia, Kontakiotis, E. G., & Anastasiadou, E. (2013). Dental Stem Cells and their Applications in Dental Tissue Engineering. the Open Dentistry Journal, 7(1), 76–81. [CrossRef]

- Grawish, M. E., Grawish, L. M., Grawish, H. M., Grawish, M. M., & El-Negoly, S. A. Challenges of engineering biomimetic dental and paradental tissues. Tissue Eng Regen Med. 2020; 17:403-21. [CrossRef]

- Ostrovidov, S. Ramalingam, M., Bae, H., Orive, G., Fujie, T., Shi, X., & Kaji, H. Bioprinting and biomaterials for dental alveolar tissue regeneration. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 2023; 14:11:991821. [CrossRef]

- Athirasala, A. Lins, F., Tahayeri, A., Hinds, M., Smith, A. J., Sedgley, C.,... & Bertassoni, L. E. A novel strategy to engineer prevascularized full-length dental pulp-like tissue constructs. Sci Rep.2017; 7:3323. [CrossRef]

- Palkowitz, A. L. Tuna, T., Bishti, S., Böke, F., Steinke, N., Müller-Newen, G., Wolfart, S., & Fischer, H. Biofunctionalization of dental abutment surfaces by crosslinked ECM proteins strongly enhances adhesion and proliferation of gingival fibroblasts. Advan Healthc Mater. 2021; 10: 2100132. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y., Wen, S., Li, Y., Jiang, M., Zhang, Y., Chen, X., & Zhai, Y. (2023). Research progress on nanomaterials for tissue engineering in oral diseases. Journal of Functional Biomaterials, 14(8), 404. [CrossRef]

- Rombouts, C. Giraud, T., Jeanneau, C., & About, I. Pulp Vascularization during Tooth Development, Regeneration, and Therapy. J Dent Res.2016; 96:137–44. [CrossRef]

- Smith, E. E. & Yelick, P. C. Bioengineering Tooth Bud constructs using GELMA hydrogel. In Methods mol biol.2019; 1922:139-50. [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y., Sun, J., Wang, W., Wang, Y., & Friedrich, R. E. (2024). How to make full use of dental pulp stem cells: an optimized cell culture method based on explant technology. Frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotechnology, 12. [CrossRef]

- Qiao, R., Tan, S., Guo, L., Ma, D., & Wen, J. (2023). Prevascularization techniques for dental pulp regeneration: potential cell sources, intercellular communication and construction strategies. Frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotechnology, 11. [CrossRef]

- Hashemibeni, B., & Moradi-Gharibvand, N. (2023). The effect of stem cells and vascular endothelial growth factor on cancer angiogenesis. Advanced Biomedical Research, 12(1), 124. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z. Oh, M. J., Sasaki, J., & Nör, J. E. (2021). Inverse and reciprocal regulation of p53/p21 and Bmi-1 modulates vasculogenic differentiation of dental pulp stem cells. Cell Death and Disease, 12(7). [CrossRef]

- Demarco, F. F., Conde, M. C. M., Cavalcanti, B. N., Casagrande, L., Sakai, V. T., & Nör, J. E. Dental pulp tissue engineering. Braz Dent J. 2011; 22:3-13. [CrossRef]

- Kökten, T., Becavin, T., Keller, L., Weickert, J. L., Kuchler-Bopp, S., & Lesot, H. Immunomodulation stimulates the innervation of engineered tooth organ. PLoS One. 2014; 9:86011. [CrossRef]

- Ratajczak, J. Bronckaers, A., Dillen, Y., Gervois, P., Vangansewinkel, T., Driesen, R. B.,... & Hilkens, P. The neurovascular properties of dental stem cells and their importance in dental tissue engineering. Stem Cells Int. 2016; 2016:9762871. [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Z., Nie, H., Wang, S., Lee, C. H., Li, A., Fu, S. Y., Zhou, H., Chen, L., & Mao, J. J. (2011). Biomaterial selection for tooth regeneration. Tissue Engineering Part B Reviews, 17(5), 373–388. [CrossRef]

- Ashtiani, R. E., Alam, M., Tavakolizadeh, S., & Abbasi, K. (2021). The role of biomaterials and biocompatible materials in Implant-Supported dental prosthesis. Evidence-based Complementary and Alternative Medicine, 2021, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- D, R. (2020). Dental stem cells- potential for tooth regeneration. Global Journal of Otolaryngology, 23(4). [CrossRef]

- Kuo, T., Sheu, S., Jiang, C., Chang, H., Chen, S., Chen, R., Hsieh, C., & Chen, M. (2015). TOOTH REGENERATION WITH DENTAL STEM CELL RESEARCH IN MINIATURE PIG MODEL. Taiwan Veterinary Journal, 41(03), 197–203. [CrossRef]

- Dal-Fabbro, R., Swanson, W. B., Capalbo, L. C., Sasaki, H., & Bottino, M. C. (2023). Next-generation biomaterials for dental pulp tissue immunomodulation. Dental Materials, 39(4), 333–349. [CrossRef]

- Nakao, K., & Tsuji, T. (2008). Dental regenerative therapy: Stem cell transplantation and bioengineered tooth replacement. Japanese Dental Science Review, 44(1), 70–75. [CrossRef]

- Mahajan, S. Singh, H., Suneja, E. S., Baweja, P. S., Sood, P., & Bajaj, K. Stem Cell Mediated Bioroot Regeneration: It’s Your Future whether you Know It or Not. [CrossRef]

- Yildirim, S., Fu, S. Y., Kim, K., Zhou, H., Lee, C. H., Li, A., Kim, S. G., Wang, S., & Mao, J. J. (2011). Tooth regeneration: a revolution in stomatology and evolution in regenerative medicine. International Journal of Oral Science, 3(3), 107–116. [CrossRef]

- Shivrayan, A. Jhajharia, K., & Sharma, P. (2014). Stem cells and their potential role in making a biotooth: A review. Indian Journal of Contemporary Dentistry, 2(1), 1-6. [CrossRef]

- Haugen, H. J., Basu, P., Sukul, M., Mano, J. F., & Reseland, J. E. (2020). Injectable biomaterials for dental tissue regeneration. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 21(10), 3442. [CrossRef]

- Kim, J., Park, J., Kim, S., Im, G., Kim, B., Lee, J., Choi, E., Song, J., Cho, K., & Kim, C. (2013). Treatment of FGF-2 on stem cells from inflamed dental pulp tissue from human deciduous teeth. Oral Diseases, 20(2), 191–204. [CrossRef]

- Marques, N. L. a. R. V., Da Costa Júnior, N. E. A., Lotif, N. M. a. L., Neto, N. E. M. R., Da Silva, N. F. F. C., & De Queiroz Martiniano, N. C. R. (2016). Application of BMP-2 for bone graft in Dentistry. RSBO, 12(1), 88–93. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).