Submitted:

20 October 2025

Posted:

24 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Material Preparation Protocol

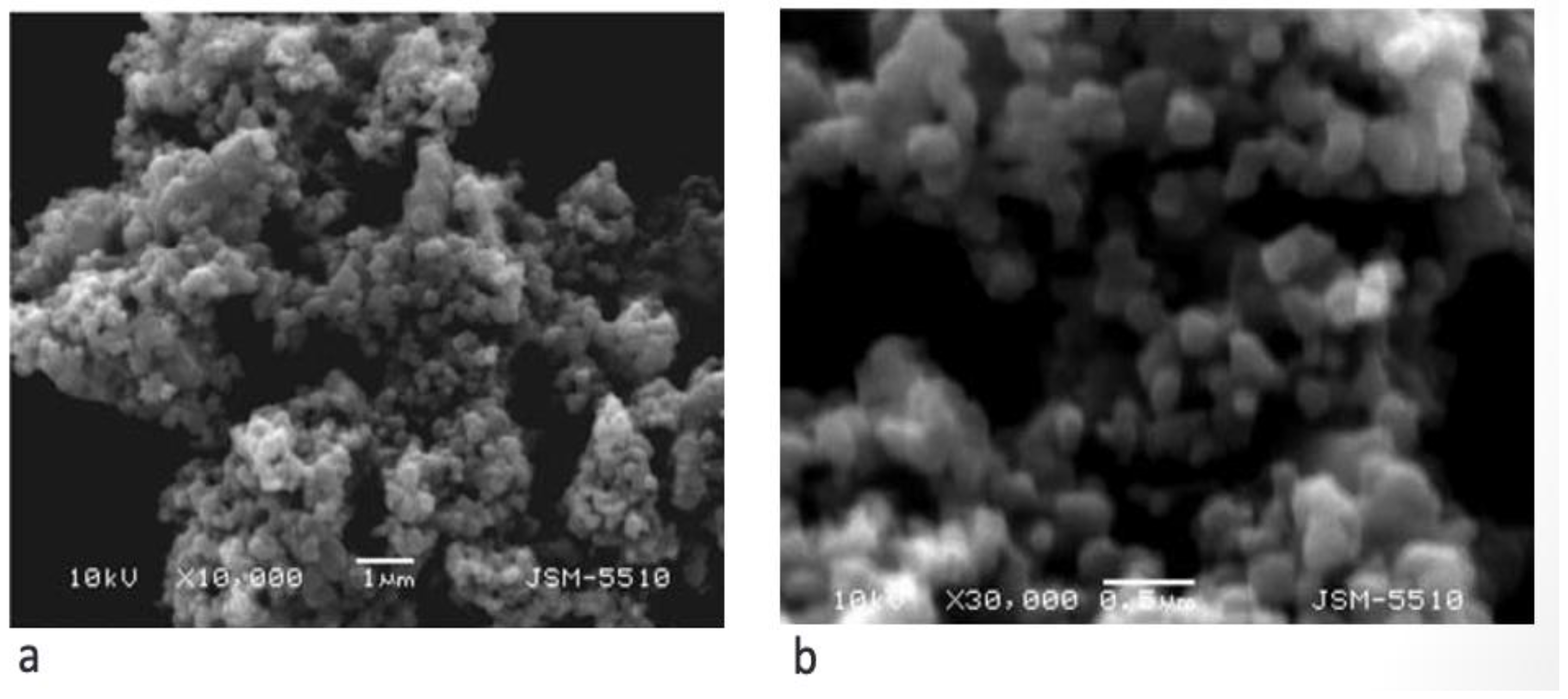

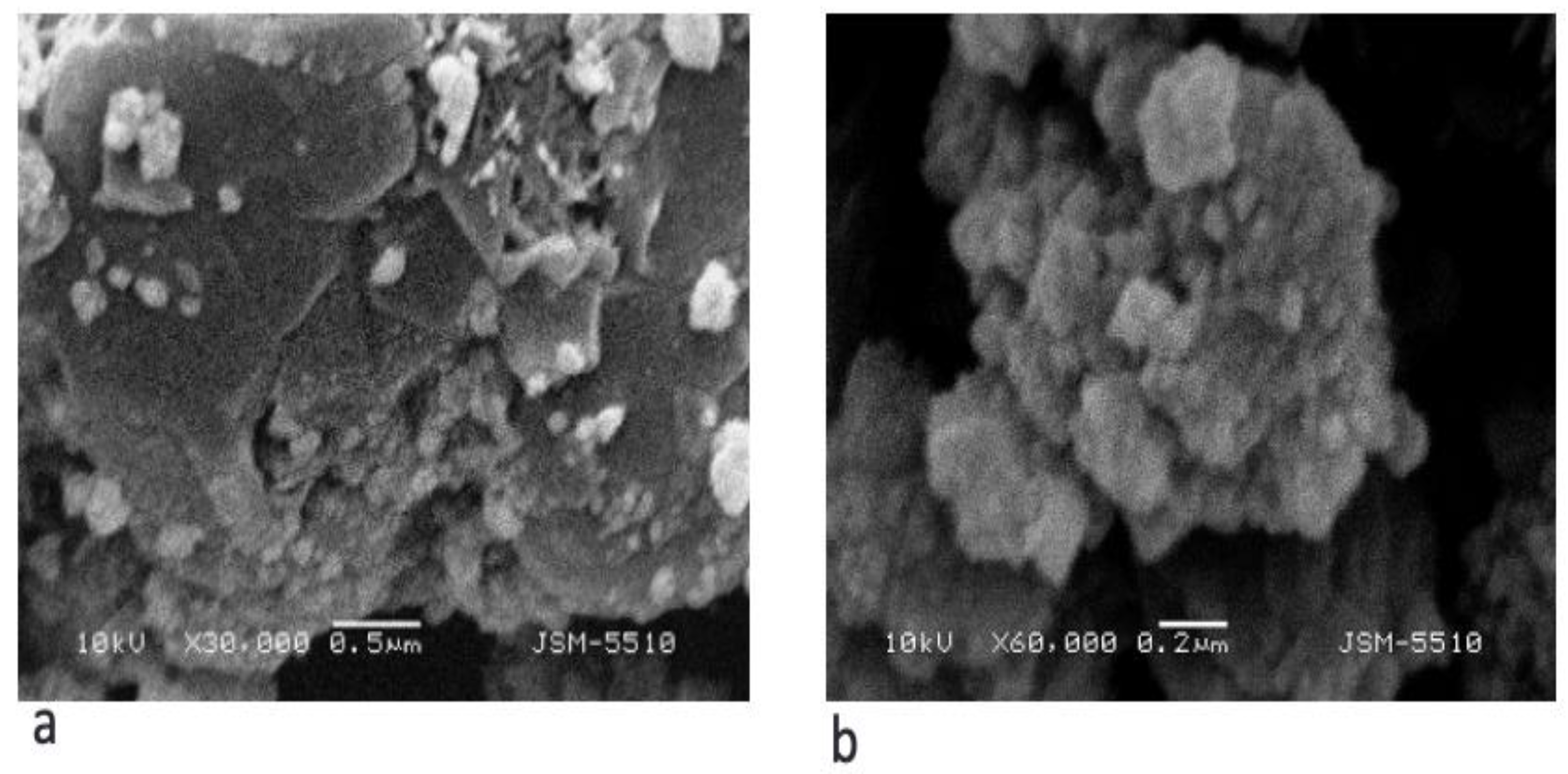

2.2. Material Characteristics

2.3. Retrospective Clinical Follow-Up Design

2.4. Clinical Protocol

2.5. Follow-Up and Outcome

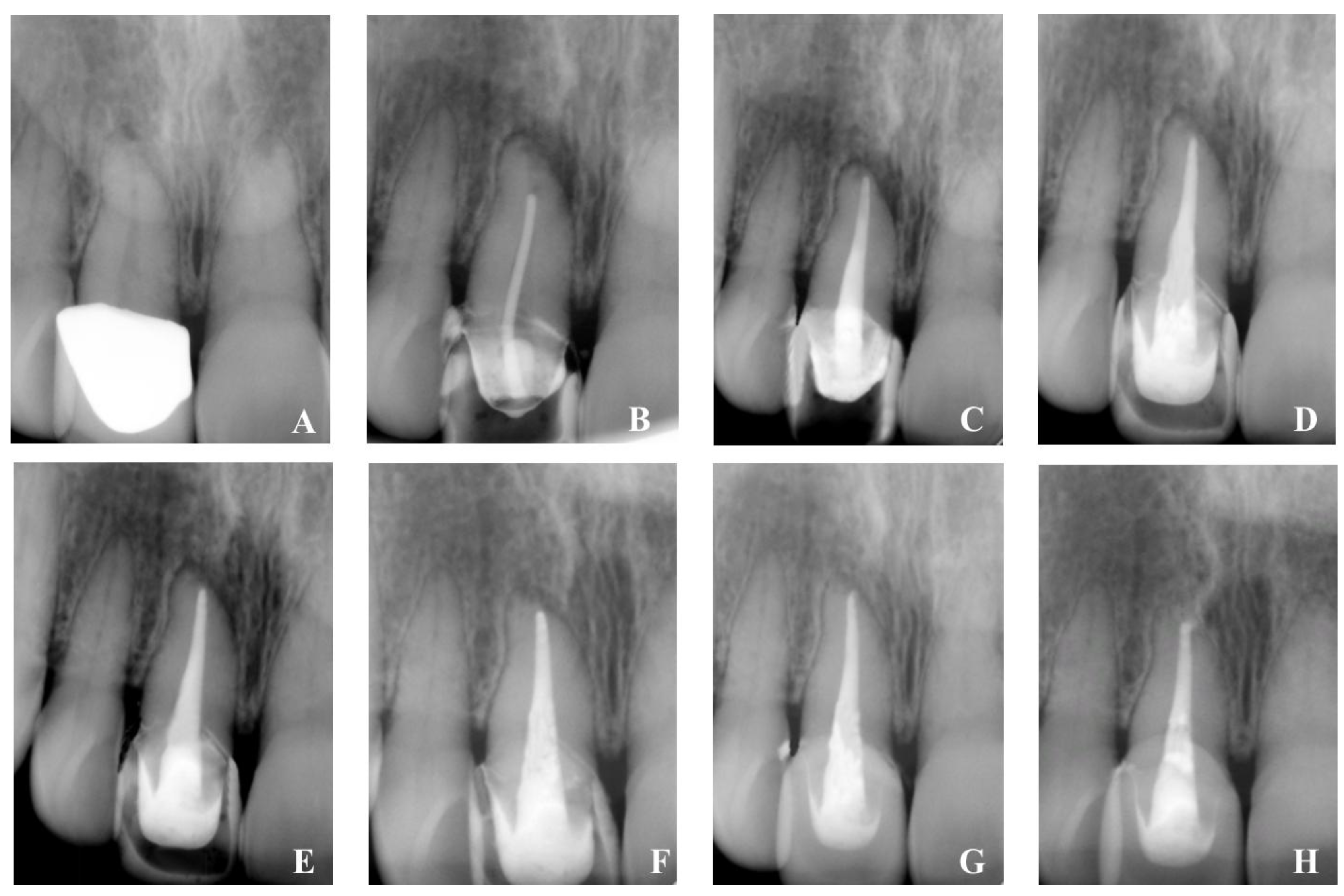

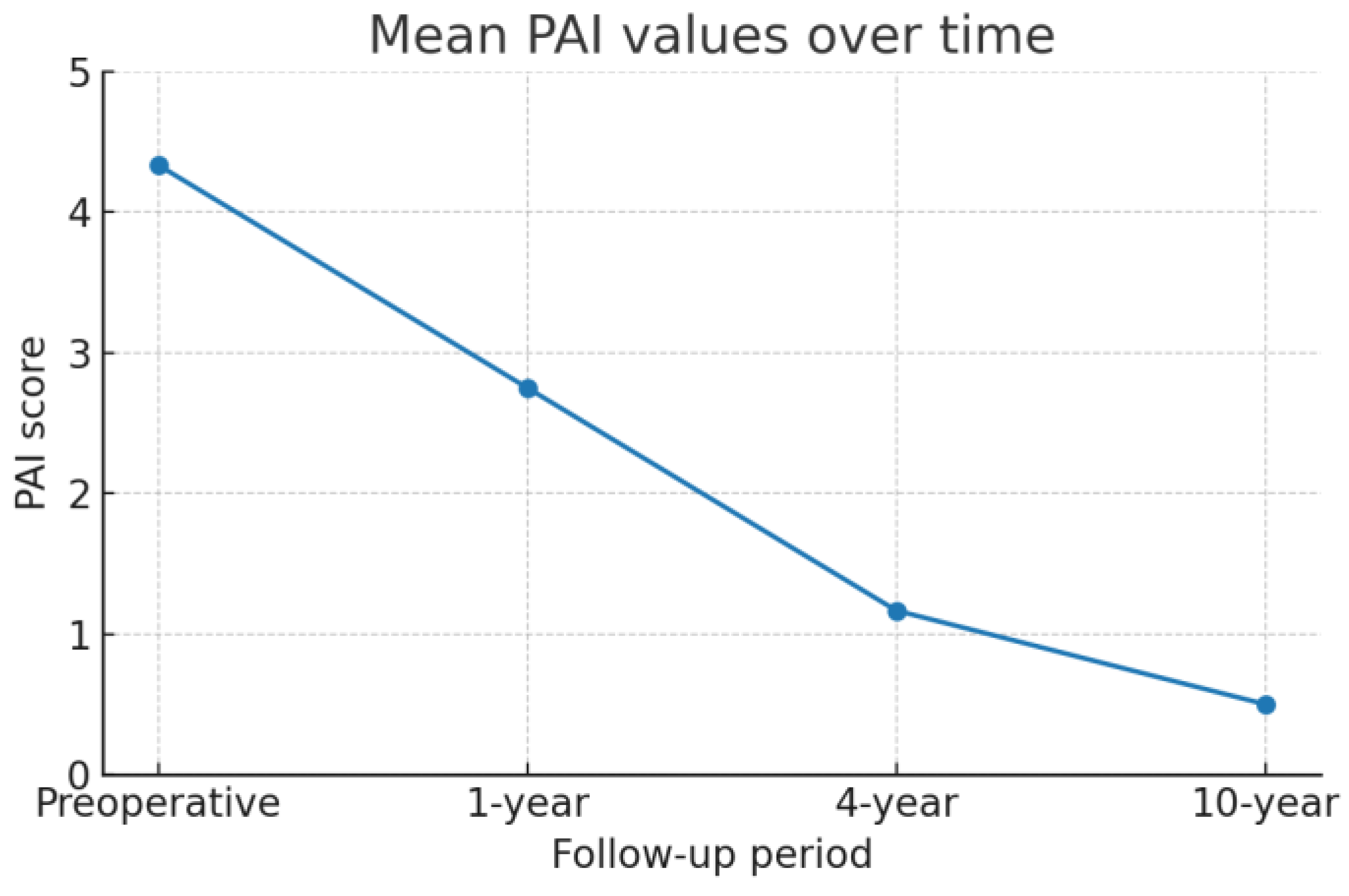

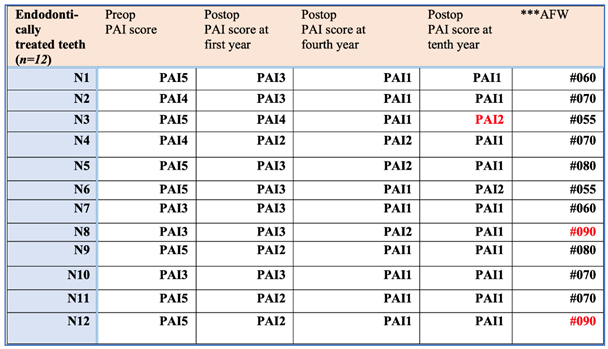

- The result of healing was evaluated using an X-ray examination as well as the periapical index scoring method developed by Ørstavik, which ranged from an initial PAI4 to PAI1 [32].

- The follow-up process demonstrates good clinical and radiographic healing possibilities.

- The use of hybrid HA/HyA biomimetic nano-hybrid material in the treatment of chronic apical lesions as an attempt to improve a regenerative healing process and to create conditions for exact canal obturation.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgements

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CAP | Chronic apical periodontitis |

| nHA | nano-crystalline hydroxyapatite |

| SEM | Scanning Electron Microscopy |

| PAI | Periapical index |

References

- Pihlstrom, B. L.; Michalowicz, B. S.; Johnson, N. W. Periodontal diseases. Lancet 2005, 366(9499), 1809–1820.

- Silva, N.; Abusleme, L.; Bravo, D.; et al. Host response mechanisms in periodontal diseases. J. Appl. Oral Sci. 2015, 23(3), 329–355. [CrossRef]

- Andreasen, J. O.; Andreasen, F. M. Textbook and Color Atlas of Traumatic Injuries to the Teeth, 3rd ed.; Munksgaard & Mosby: St. Louis, 1994; pp 370–372. [CrossRef]

- Leonardo, M.; Silva, A.; Leonardo, R.; et al. Histological evaluation of therapy using a calcium hydroxide dressing for teeth with incompletely formed apices and periapical lesions. J. Endod. 1993, 19, 348–352. . [CrossRef]

- Maroto, M.; Barbería, E.; Planells, P.; Vera, V. Treatment of non-vital immature incisor with mineral trioxide aggregate (MTA). Dent. Traumatol. 2003, 19(3), 165–169. [CrossRef]

- Webber, R. T. Apexogenesis versus apexification. Dent. Clin. North Am. 1984, 28, 669–697. [CrossRef]

- Tibbitt, M.; Anseth, K. Hydrogels as extracellular matrix mimics for 3D cell culture. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2009, 103(4), 655–663. . [CrossRef]

- Tsiklin, I. L.; Shabunin, A. V.; Kolsanov, A. V.; Volova, L. T. In Vivo Bone Tissue Engineering Strategies: Advances and Prospects. Polymers (Basel) 2022, 14(15), 3222. [CrossRef]

- Bergenholtz, G.; Spangberg, L. Controversies in Endodontics. Crit. Rev. Oral Biol. Med. 2004, 15(2), 99–114. [CrossRef]

- Gusiyska, A. In vivo analysis of some key characteristics of the apical zone in teeth with chronic apical periodontitis. J. IMAB 2014, 20(5), 638–641. [CrossRef]

- Lyu, P.; Song, Y.; Bi, R.; et al. Protective Actions in Apical Periodontitis: The Regenerative Bioactivities Led by Mesenchymal Stem Cells. Biomolecules 2022, 12(12), 1737. [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Soto, E.; Elmsmari, F.; Mahmoud, O.; González, J. A. Case Report: Apical periodontitis due to calculus-like deposit on the external surface of the root apex. Front. Oral Health 2025, 6, 1615050. [CrossRef]

- Gusiyska, A.; Dyulgerova, E. Calcium Phosphate Bioceramic as Apical Barrier Material in Complicated Endodontic Cases—A Case Report. Int. J. Sci. Res. 2015, 4(2), 2177–2181.

- Benyus, J. M. Biomimicry: Innovation Inspired by Nature; William Morrow: New York, 1997. .

- Vaiani, L.; Boccaccio, A.; Uva, A. E.; et al. Ceramic Materials for Biomedical Applications: An Overview on Properties and Fabrication Processes. J. Funct. Biomater. 2023, 14(3), 146. [CrossRef]

- Gusiyska, A.; Ilieva, R. Nanosize Biphasic Calcium Phosphate used for Treatment of Periapical Lesions. Int. J. Curr. Res. 2015, 7(1), 11564–11567.

- Nicolae, C.-L.; Pîrvulescu, D.-C.; Niculescu, A.-G.; et al. An Overview of Nanotechnology in Dental Medicine. J. Compos. Sci. 2024, 8, 352. [CrossRef]

- Zhai, P.; Peng, X.; Li, B.; et al. The application of hyaluronic acid in bone regeneration. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 151, 1224–1239. [CrossRef]

- Ilieva, R.; Dyulgerova, E.;Petrov, O.;Tarassov. M.;Gusiyska, A.; Vasileva, R. Preparation of hydroxyapatite/hyaluronan biomimetic nanohybrid material for reconstruction of critical size bone defects. Bulgar. Chem. Commun. 2018, 50, 97–105.

- Suzuki, K.; Anada, T.; et al. Effect of addition of hyaluronic acids on the osteoconductivity and biodegradability of synthetic octacalcium phosphate. Acta Biomater. 2014, 10, 531–543. [CrossRef]

- Combes, C.; Rey, C. Adsorption of Proteins and Calcium Phosphate Materials Bioactivity. Biomaterials 2002, 23(13), 2817–2823. [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Wang, Y.; Ji, C.; et al. The impact of hydroxyapatite crystal structures and protein interactions on bone's mechanical properties. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14(1), 9786. [CrossRef]

- Hench, L. Bioceramics: From Concept to Clinic. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 1991, 74(7), 1487.

- Todros, S.; Todesco, M.; Bagno, A. Biomaterials and Their Biomedical Applications: From Replacement to Regeneration. Processes 2021, 9(11), 1949. [CrossRef]

- Fang, C.; Lin, Y.; et al. Biomimetic Synthesis of Nanocrystalline Hydroxyapatite Composites: Therapeutic Potential and Effects on Bone Regeneration. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20(23), 6002. [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, K.; Goto, T.; et al. Apatite-coated hyaluronan for bone regeneration. J. Dent. Res. 2011, 90(7), 906–911. [CrossRef]

- Bohner, M. Design of ceramic-based cements and putties for bone graft substitution. Eur. Cell Mater. 2010, 20(1), 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Laurent, T.; Frazer, J. Hyaluronan. FASEB J. 1992, 6(7), 2397–2404.

- Lorenzi, C.; Leggeri, A.; et al. Hyaluronic Acid in Bone Regeneration: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Dent. J. 2024, 12(8), 263. [CrossRef]

- Valachová, K.; Hassan, M. E.; Šoltés, L. Hyaluronan: Sources, Structure, Features and Applications. Molecules 2024, 29(3), 739. [CrossRef]

- Simeonov, M.; Gusiyska, A.; et al. Novel hybrid chitosan/calcium phosphates microgels for remineralization of demineralized enamel – A model study. Eur. Polym. J. 2019, 119, 14–21.

- Ørstavik, D.; Kerekes, K.; Eriksen, H. The periapical index: a scoring system for radiographic assessment of apical periodontitis. Endod. Dent. Traumatol. 1986, 2, 20–34. [CrossRef]

- Ilieva, R.; Dyulgerova, E.; Petrov, O.; et al. Effects of high energy dry milling on biphase calcium phosphates. Adv. Appl. Ceram. 2013, 112(4), 219–226. [CrossRef]

- Sabeti, M.; Chung, Y. J.; Aghamohammadi, N.; et al. Outcome of Contemporary Nonsurgical Endodontic Retreatment: A Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Trials and Cohort Studies. J. Endod. 2024, 50(4), 414–433. [CrossRef]

- Almufleh, L. S. The outcomes of nonsurgical root canal treatment and retreatment assessed by CBCT: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Saudi Dent. J. 2025, 37, 14. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Zuo, J.; Chen, S. H.; Holiday, L. S. Calcium hydroxide reduces lipopolysaccharide-stimulated osteoclast formation. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. Endod. 2003, 95(3), 348–354. [CrossRef]

- Thomas, R. P.; Moule, A. J.; Bryant, R. Root canal morphology of maxillary permanent first molar teeth at various ages. Int. J. Endod. 1993, 26(5), 257–267. [CrossRef]

- Bergenholtz, G. Biologische Grundlagen der Endodontie [Fundamental biologic considerations in endodontics]. Dtsch. Zahnarztl. Z. 1990, 45(4), 187–191.

- Segvich, S.; Biswas, S.; Becker, U.; Kohn, D. H. Identification of peptides with targeted adhesion to bone-like mineral via phage display and computational modeling. Cells Tissues Organs 2009, 189(14), 245–251. [CrossRef]

- Opalchenova, G.; Dyulgerova, E.; Petrov, O. Effect of calcium phosphate ceramics on gram-negative bacteria resistant to antibiotics. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 1996, 32(3), 473–479.

- Kyaw, M. S.; Kamano, Y.; Yahata, Y.; et al. Endodontic Regeneration Therapy: Current Strategies and Tissue Engineering Solutions. Cells 2025, 14, 422. [CrossRef]

- Delpierre, A.; Savard, G.; Renaud, M.; Rochefort, G. Y. Tissue Engineering Strategies Applied in Bone Regeneration and Bone Repair. Bioengineering 2023, 10(6), 644. [CrossRef]

- Kulild, J. C.; Peters, D. D. Incidence and configuration of canal systems in the mesiobuccal root of maxillary first and second molars. J. Endod. 1990, 16(7), 311–317.

- Gorni, F. G.; Gagliani, M. M. The outcome of endodontic retreatment: a 2-year follow-up. J. Endod. 2004, 30(1), 1–4. [CrossRef]

- Gusiyska, A. Periapical resorptive processes in chronic apical periodontitis: an overview and discussion of the literature. J. IMAB 2014, 20(5), 601–605. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, N.; Maher, N.; Amin, F.; et al. Biomimetic Approaches in Clinical Endodontics. Biomimetics (Basel) 2022, 7(4), 229. [CrossRef]

- Gusiyska, A.; Gateva, N.; Kabaktchieva, R.; et al. Retrospective study of the healing processes of endodontically treated teeth characterized by osteolytic defects of the periapical area: four-year follow-up. Biotechnol. Biotechnol. Equip. 2017, 31(1), 187–192. [CrossRef]

- Farhana, F.; et al. Biomimetic materials: A realm in the field of restorative dentistry and endodontics: A review. Int. J. Appl. Dent. Sci. 2020, 6(1), 31–34.

| Comparison | W-statistic | Raw p-value |

Adjusted p-value (Holm) |

Effect size r |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Preop. PAI score vs 1st year |

0.0 | 0.0069 | 0.0138 | 0.88 |

| Preop. PAI score vs 4th year |

0.0 | 0.0005 | 0.0029 | 0.88 |

| Preop. PAI score vs 10th year |

0.0 | 0.0005 | 0.0029 | 0.88 |

| 1st year PAI score vs 4th year |

0.0 | 0.0028 | 0.0083 | 0.88 |

| 1st year PAI score vs 10th year |

0.0 | 0.0005 | 0.0029 | 0.88 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).