Submitted:

24 June 2024

Posted:

25 June 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. The preparation of Materials

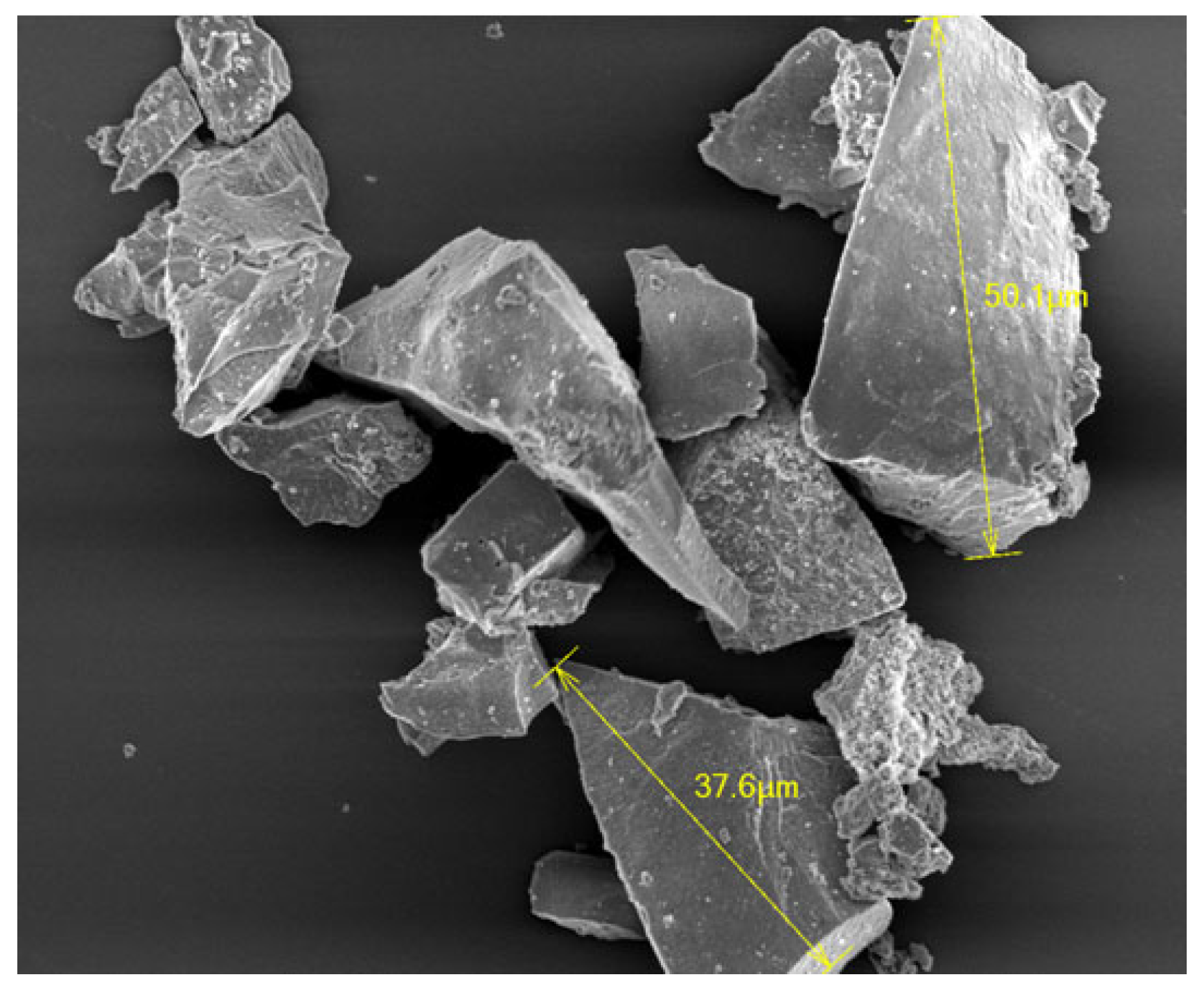

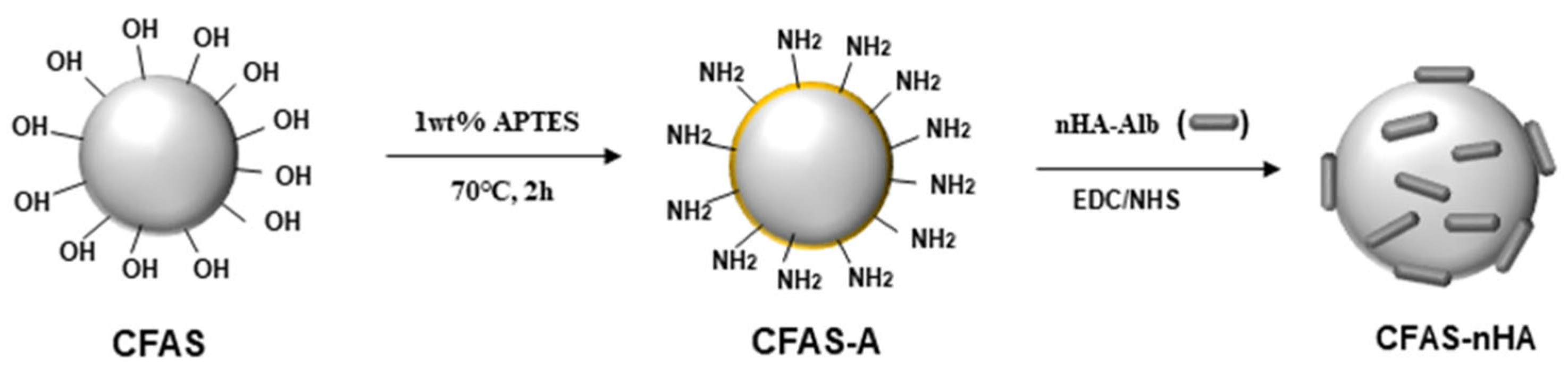

2.2. Synthesis and Surface Modification of CFAS

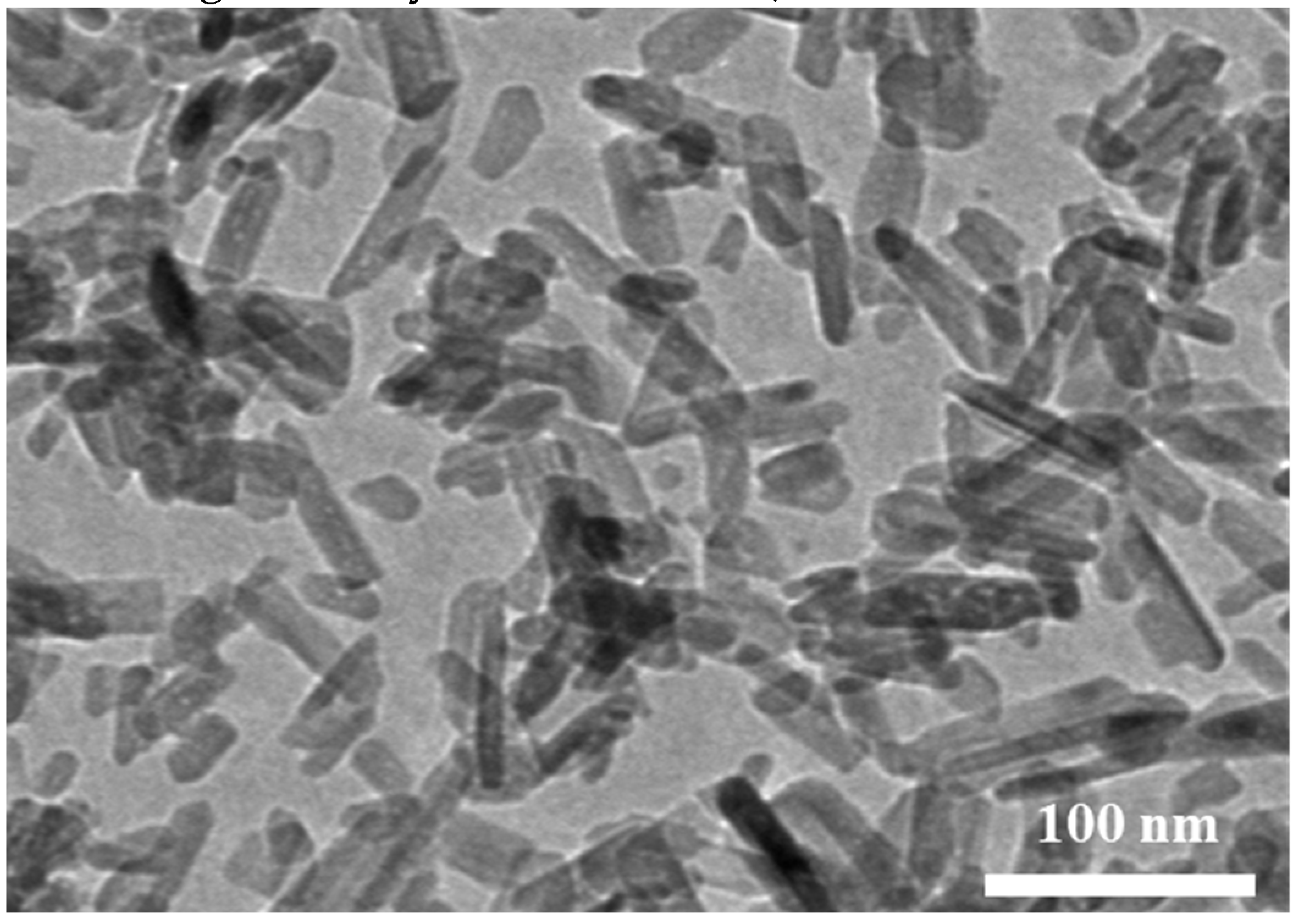

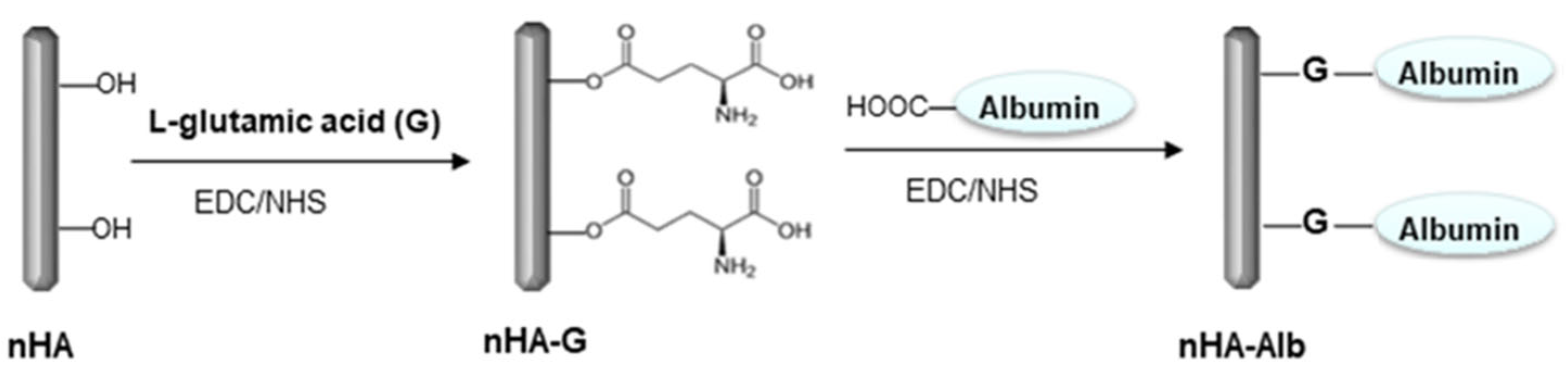

2.3. Surface Modification of nHA

2.4. Chemical Bonding of nHA to the CFAS Surface

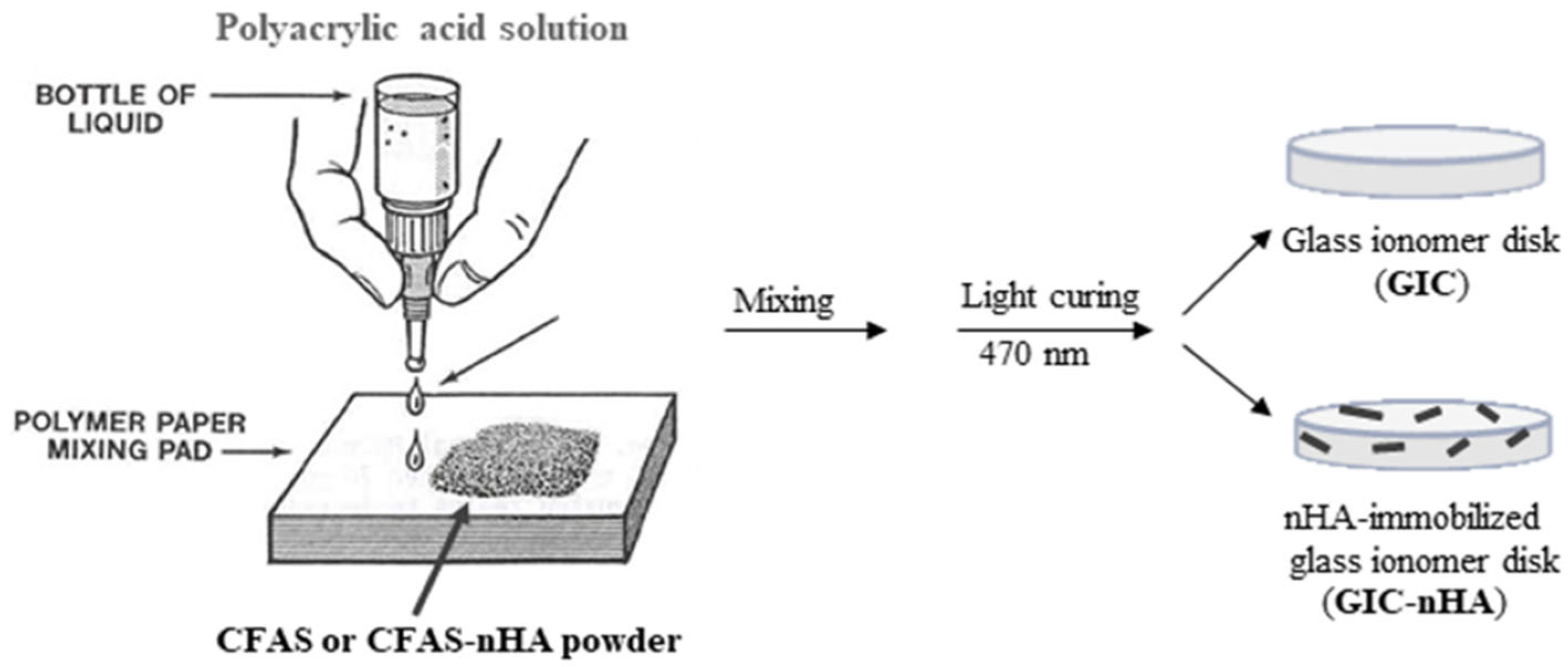

2.5. Preparation of GIC-nHA discs

2.6. Cytocompatibility of GIC-nHA

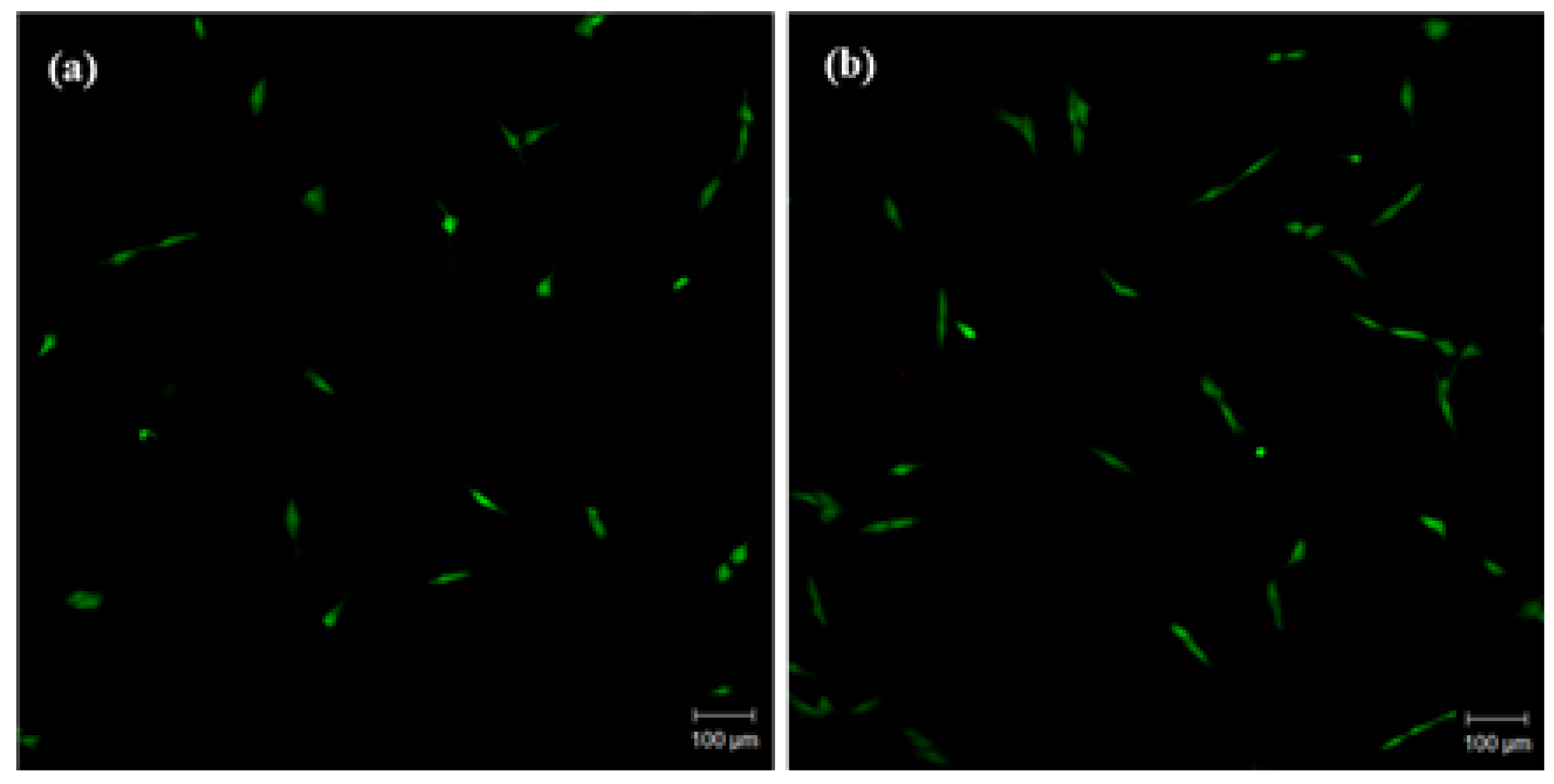

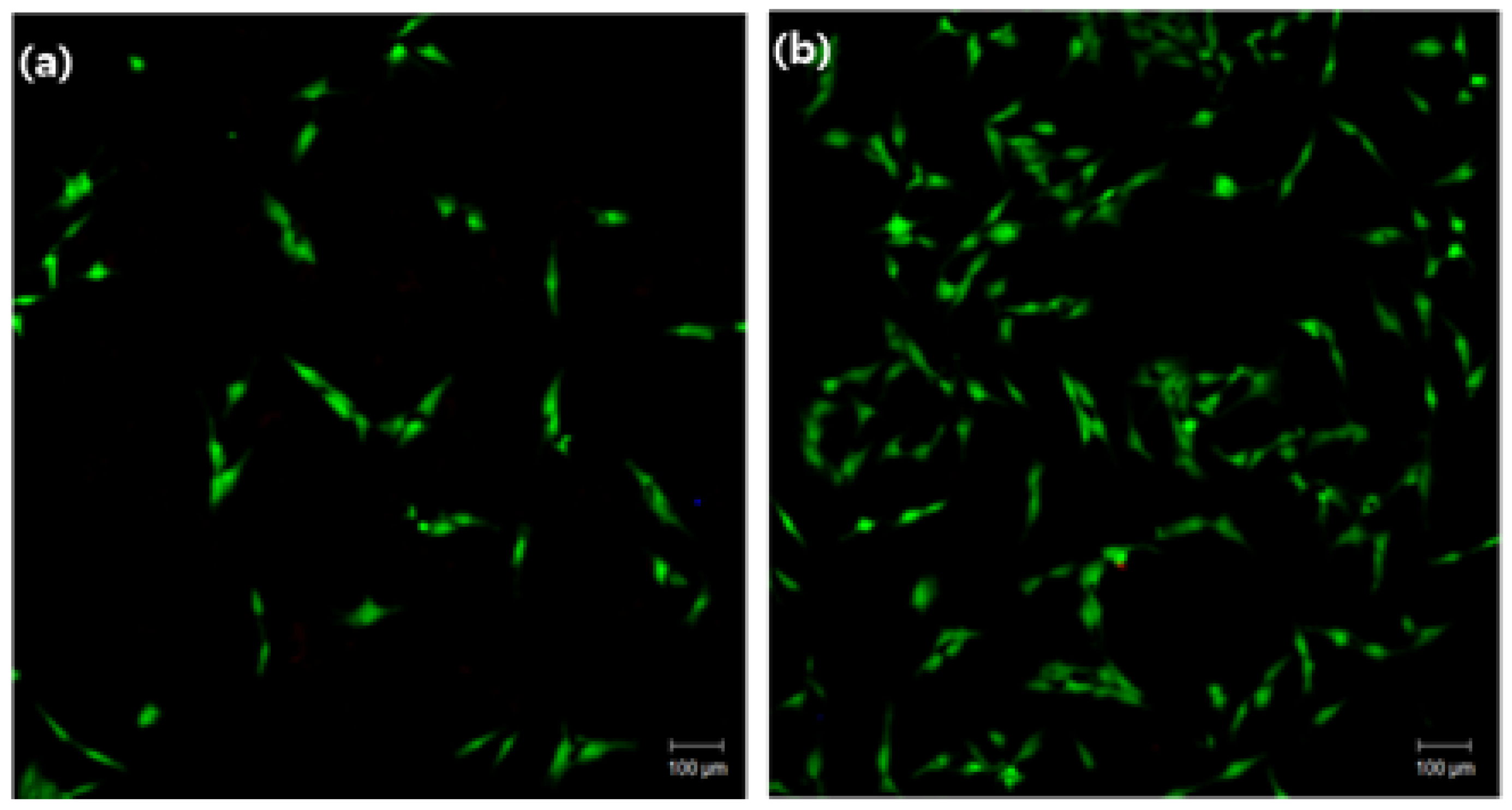

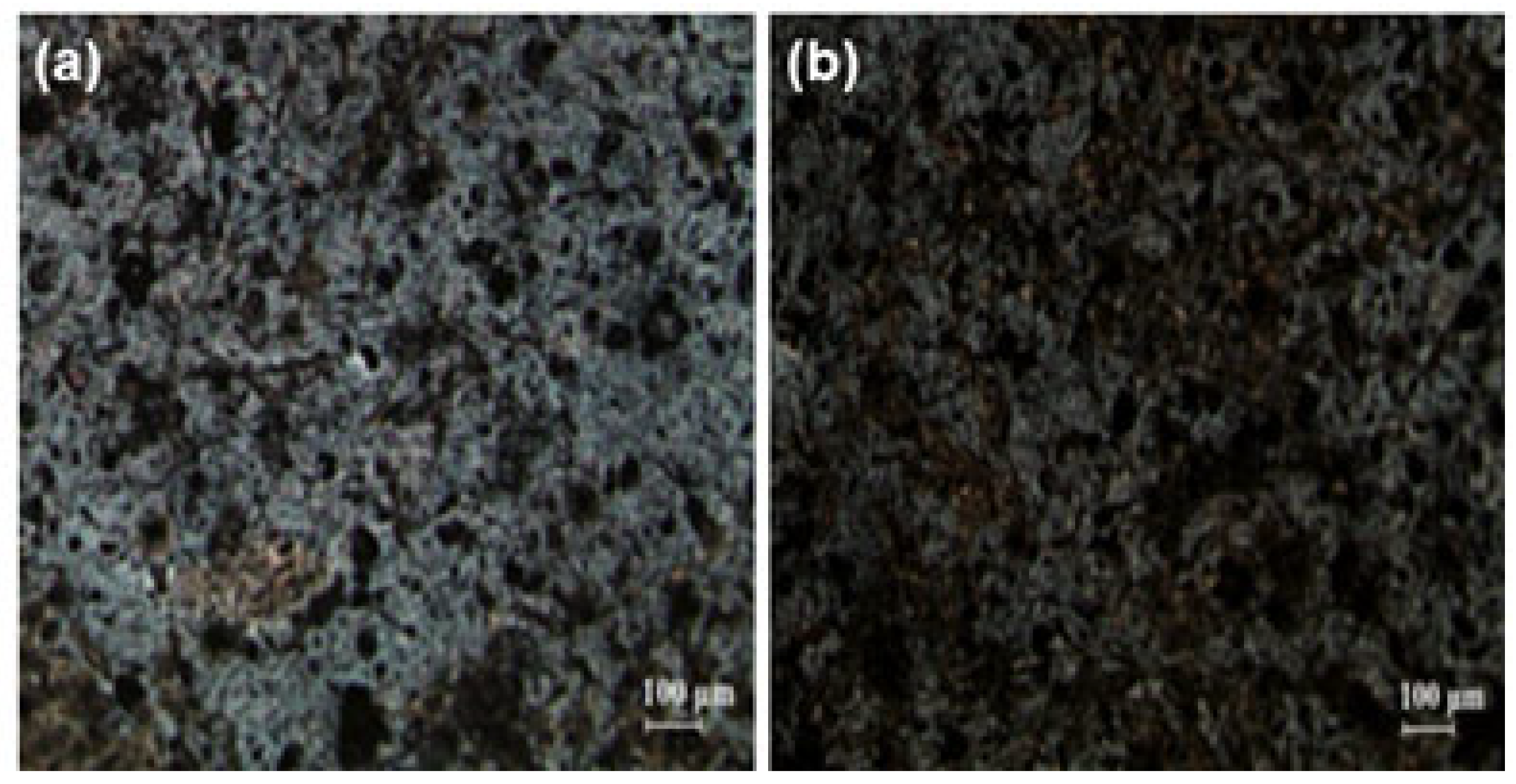

2.6.1. Cell Adhesion

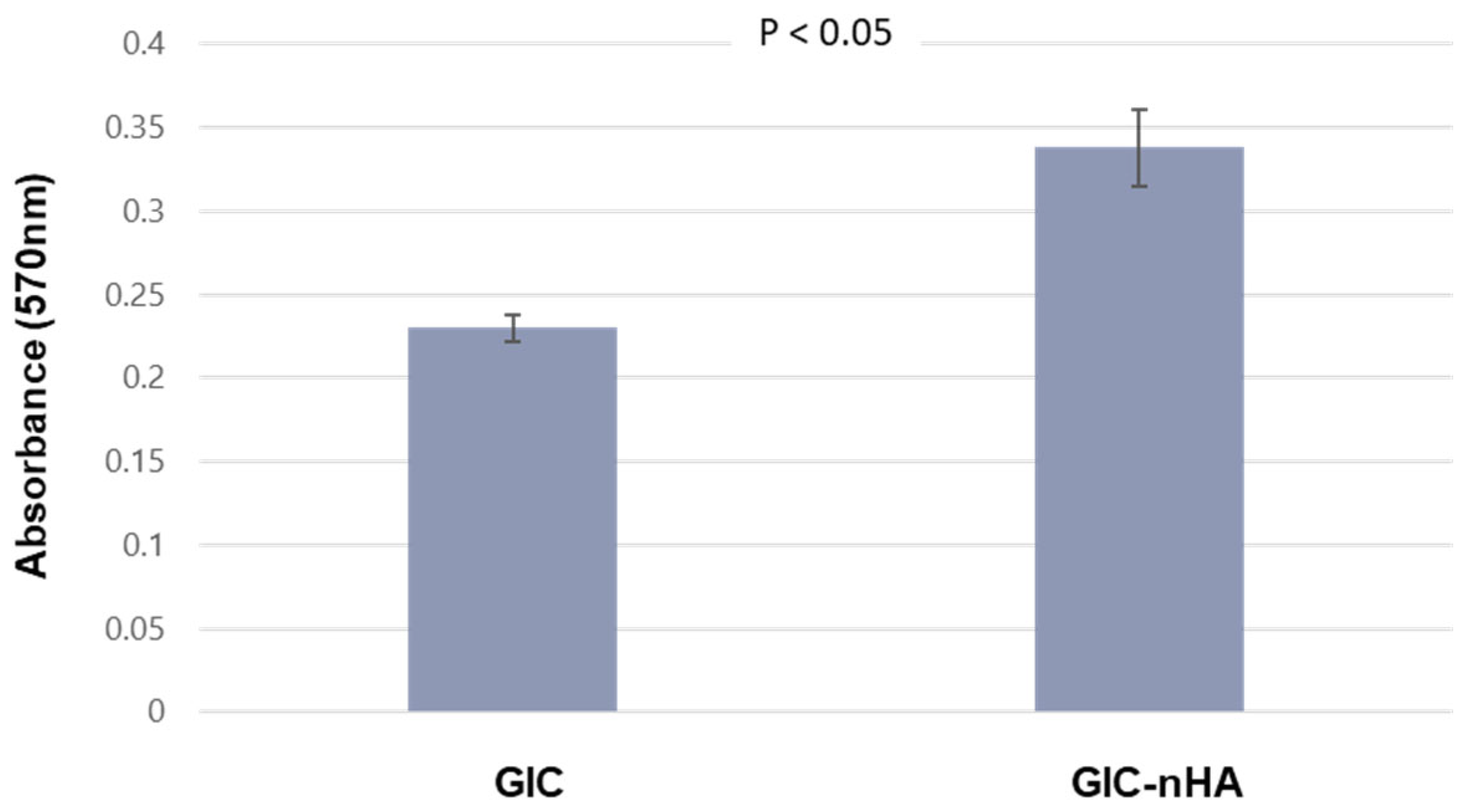

2.6.2. MTT Assay

2.6.3. Cytotoxicity

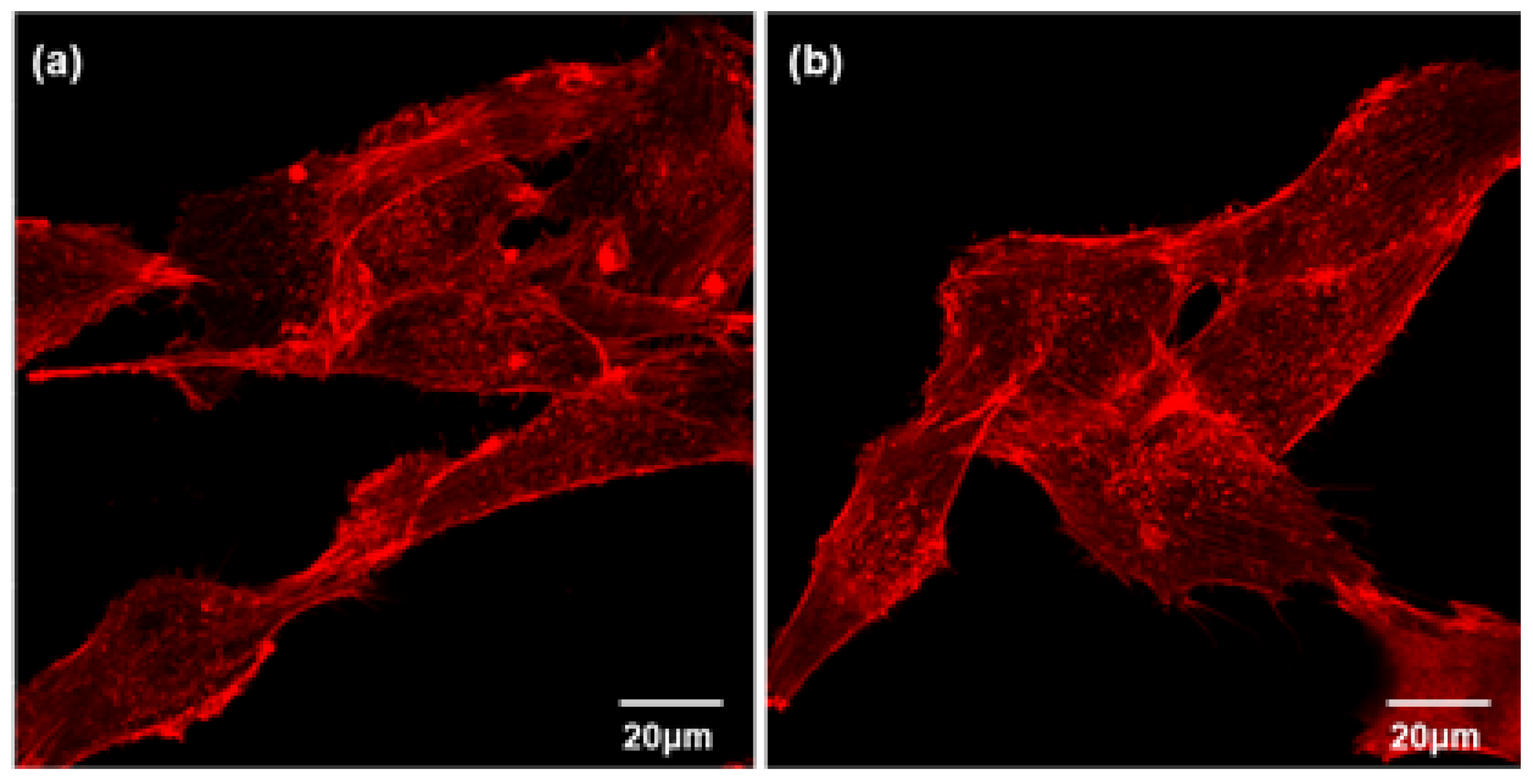

2.6.4. Actin Cytoskeleton Assay

2.6.5. von Kossa Assay

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Result

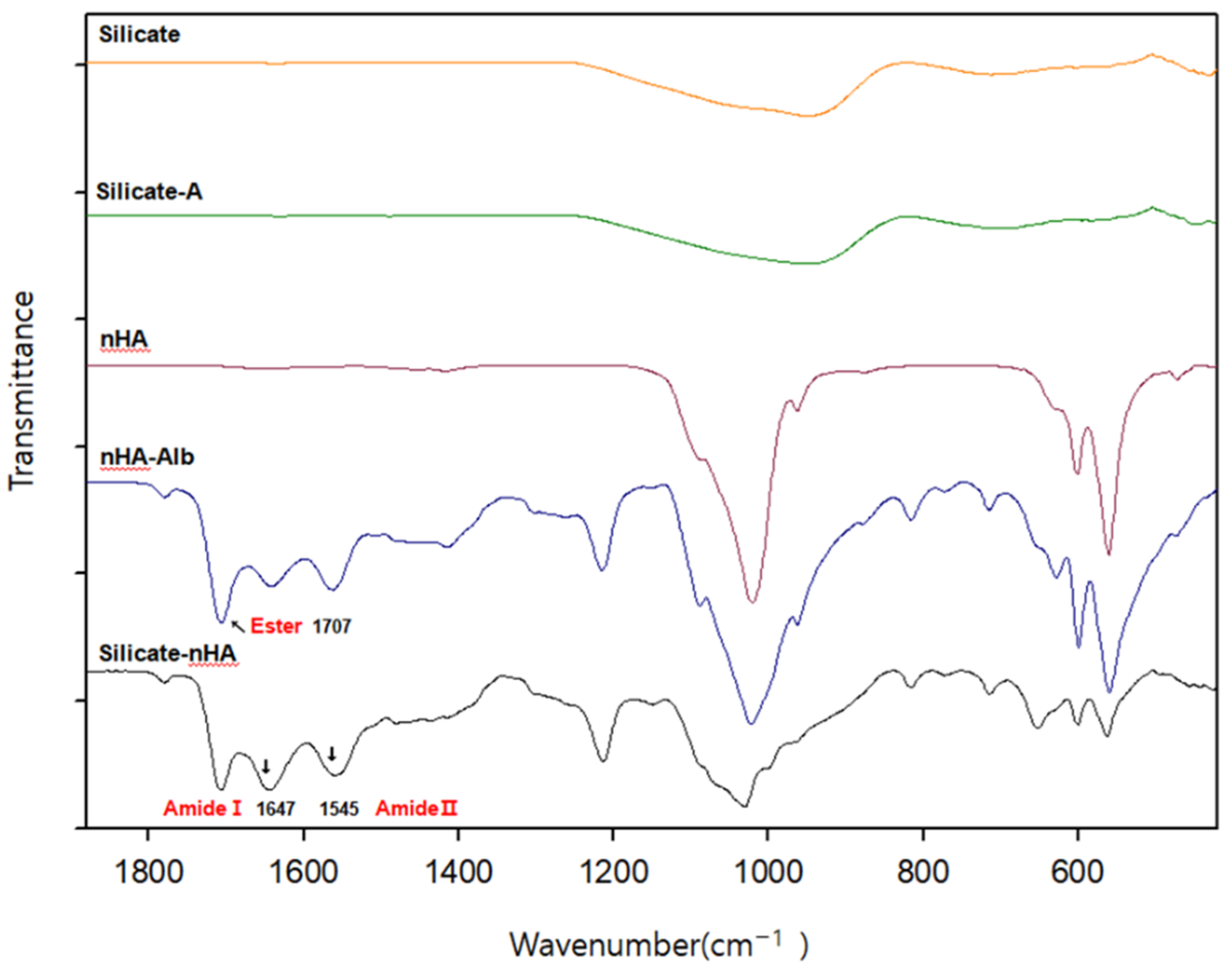

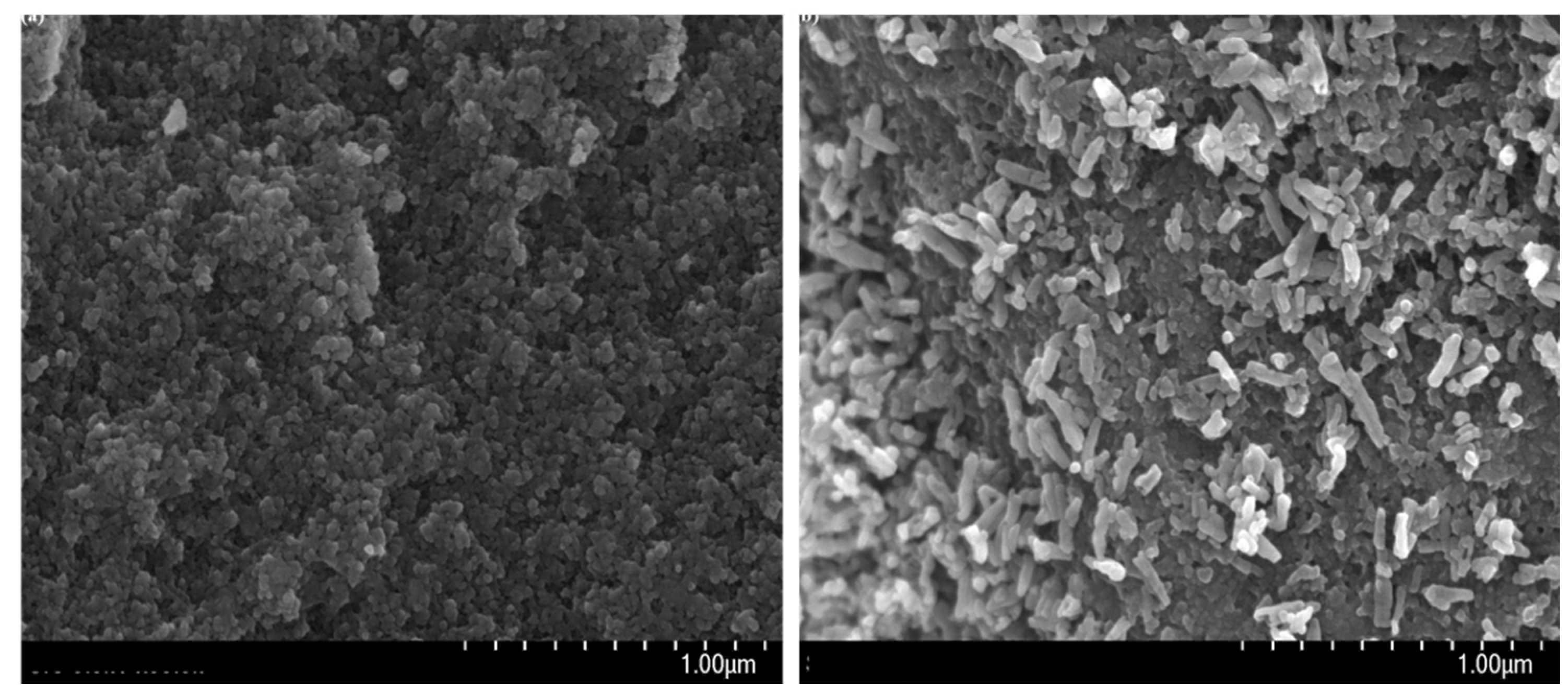

3.1. Immobilization of nHA on CFAS particle surface

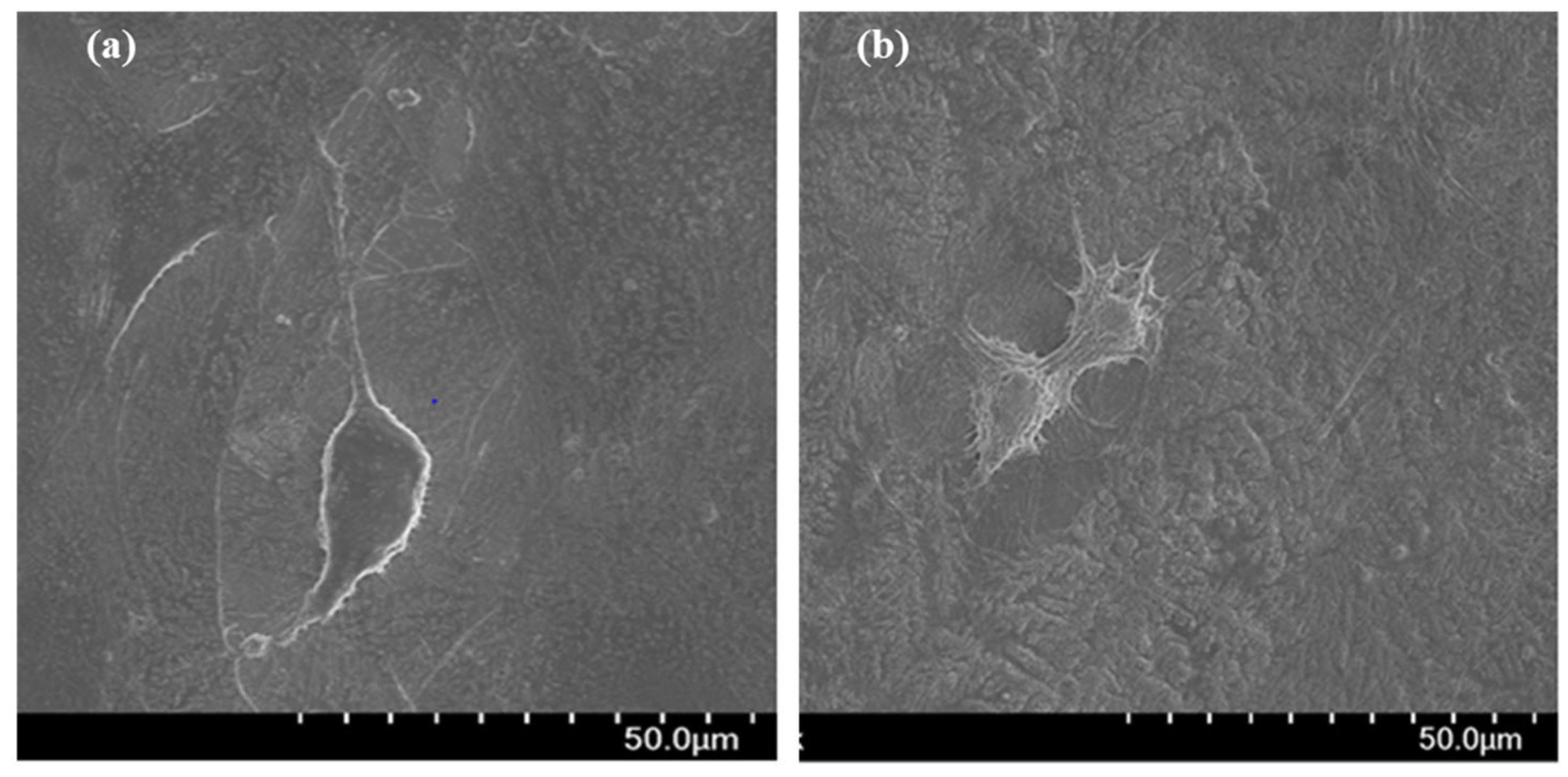

3.2. Cytocompatibility of GIC-nHA

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sharanbir, K.S.; John, W.N. A review of glass-ionomer cements for clinical dentistry. J. Funct. Biomater. 2016, 7, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farahnaz, S.; Ali, A.A.; Saba, S.; Mina, S. Comparison of shear bond strength of three types of glass ionomer cements containing hydroxyapatite nanoparticles to deep and superficial dentin. J. Dent. 2020, 21, 132–140. [Google Scholar]

- Maja, B.P.; Valentina, B.R.; Ana, I.; Ana, P.; Sevil, G.; Ivana, M. Mechanical properties of glass ionomer cements after incorporation of marine derived hydroxyapatite. Materials 2020, 13, 3542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, F.; Rahman, S.; Khurshid, Z.; Zafar, M.S.; Sefat, F.; Kumar, N. Effect of nanostructures on the properties of glass ionomer dental restoratives/cements: A comprehensive narrative review. Materials 2021, 14, 6260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arita, K.; Yamamoto, A.; Shinonaga, Y.; Harada, K.; Abe, Y.; Nakagawa, K.; Sugiyama, S. Hydroxyapatite particle characteristics influence the enhancement of the mechanical and chemical properties of conventional restorative glass ionomer cement. Dent. Mater. J. 2011, 30, 672–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohd Pu'ad, N.A.S.; Abdul Haq, R.H.; Mohd, N.; Abdullah, H.Z.; Idris, M.I.; Lee, T.C. Synthesis method of hydroxyapatite: A review. Materials Today: Proceedings 2020, 29, 233–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haider, A.; Haider, S.; Han, S.S.; Kang, I.-K. Recent advances in the synthesis, functionalization and biomedical applications of hydroxyapatite: A review. RSC Adv. 2017, 7, 7442–7458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadat-Shojai, M.; Khorasani, M.T.; Dinpanah-Khoshdargi, E.; Jamshidi, A. Synthesis methods for nanosized hydroxyapatite with diverse structures. Acta Biomater. 2013, 9, 7591–7621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, I.G.; Park, C.I.; Lee, H.; Kim, H.E.; Lee, S.M. Hydroxyapatite microspheres as an additive to enhance radiopacity, biocompatibility and osteoconductivity of poly(methylmethacrylate) bone cement. Materials 2018, 11, 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Praveen, B.; Attiguppe, R.P.; Nadig, B. An in vitro comparative evaluation of compressive strength and antibacterial activity of conventional GIC and hydroxyapatite reinforced GIC in different storage media. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 2015, 9, ZC51–ZC55. [Google Scholar]

- Haider, A.; Gupta, K.C.; Kang, I.K. Morphological effects of HA on the cell compatibility of electrospun HA/PLGA composite nanofiber scaffolds. Biomed. Res. Int. 2014, 2014, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, S.J.; Gupta, K.C.; Kim, H.; Kim, S.; Kang, I.-K. Osteoblast behaviours on nanorod hydroxyapatite-grafted glass surfaces. Biomater. Res. 2019, 23, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khiri, M.Z.A.; Matori, K.A.; Zaid, M.H.M.; Abdullah, A.C.; Zainuddin, N.; Jusoh, W.N.W.; Jalil, R.A.; Rahman, N.A.A.; Kul, E.; Wahab, S.A.A.; Effendy, N. Soda lime silicate glass and clam shell act as precursor in synthesize calciumfluoroaluminosilicate glass to fabricate glass ionomer cement with different ageing time. J. Mater. Res. Tech. 2020, 9, 6125–6134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, S.; Liu, Y.; Ma, Z.; Liu, C.; Chai, J.; Li, Z.; Song, W.; Hu, K. A novel vertical aligned mesoporous silica coated nanohydroxyapatite particle as efficient dexamethasone carrier for potential application in osteogenesis. Biomed. Mater. 2021, 16, 035030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aykol, M.; Montoya, J.H.; Hummelshøj, J. Rational solid-state synthesis routes for inorganic materials. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143, 9244–9259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haider, A.; Versace, D.; Gupta, K.C.; Kang, I.-K. Pamidronic acid-grafted nHA/PLGA hybrid nanofiber scaffolds suppress osteoclastic cell viability and enhance osteoblastic cell activity. J. Mater. Chem. B 2016, 4, 7596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamiya, H.; Iijima, M. Surface modification and characterization for dispersion stability of inorganic nanometer-scaled particles in liquid media. Sci. Tech. Adv. Mater. 2010, 11, 044304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwon, G.; Kim, H.; Gupta, K.C.; Kang, I.-K. Enhanced tissue compatibility of polyetheretherketone disks by dopamine-mediated protein immobilization. Macromol. Res. 2018, 25, 128–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, Z.-C.; Han, S.-J.; Shin, Y.-S.; Koo, T.-H.; Moon, S.; Jeong, Y.; Kang, I.-K. Enhanced osteoblast responses to poly(methyl methacrylate)/hydroxyapatite electrospun nanocomposites for bone tissue engineering. J. Biomater. Sci. Polym. Ed. 2013, 24, 61–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiernan, H.; Byrne, B.; Kazarian, S.G. ATR-FTIR spectroscopy and spectroscopic imaging for the analysis of biopharmaceuticals. Spectrochim Acta A Mol Biomol Spectrosc. 2020, 241, 118636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhazmi, H.A. FT-IR spectroscopy for the identification of binding sites and measurements of the binding interactions of important metal ions with bovine serum albumin. Sci. Pharm. 2019, 87, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.J.; Kim, B.S.; Gupta, K.C.; Lee, D.Y.; Kang, I.-K. Hydroxyapatite nanorod-modified sand blasted titanium disk for endosseous dental implant applications. Tissue Eng. Regen. Med. 2018, 15, 601–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haider, A.; Kim, S.; Huh, M.-W.; Kang, I.-K. BMP-2 grafted nHA/PLGA hybrid nanofiber scaffold stimulates osteoblastic cells growth. Biomed. Res. Int. 2015, 2015, 281909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fletcher, D.A.; Mullins, R.D. Cell mechanics and the cytoskeleton. Nature 2010, 28, 485–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tayalia, P.; Mooney, D.J. Controlled growth factor delivery for tissue engineering. Adv. Mater. (Weinheim, Ger.) 2009, 21, 3269–3285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moshaverinia, A.; Ansari, S.; Moshaverinia, M.; Roohpour, N.; Darr, J.A.; Rehman, I. Effects of incorporation of hydroxyapatite and fluoroapatite nanobioceramics into conventional glass ionomer cements (GIC). Acta Biomater. 2008, 4, 432–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilić-Prcić, M.; Brzović Rajić, V.; Ivanišević, A.; Pilipović, A.; Gurgan, S.; Miletić, I. Mechanical Properties of Glass Ionomer Cements after Incorporation of Marine Derived Hydroxyapatite. Materials (Basel) 2020, 13, 3542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barandehfard, F.; Kianpour Rad, M.; Hosseinnia, A.; Khoshroo, K.; Tahriri, M.; Jazayeri, H.E.; Moharamzadeh, K.; Tayebi, L. The addition of synthesized hydroxyapatite and fluorapatite nanoparticles to a glass-ionomer cement for dental restoration and its effects on mechanical properties. Ceram. Int. 2016, 42, 17866–17875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noorani, T.Y.; Luddin, N.; Ab. Rahman, I.; Masudi, S.M. In vitro cytotoxicity evaluation of novel nano-hydroxyapatite-silica incorporated glass ionomer cement. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 2017, 11, ZC105–ZC109. [Google Scholar]

- Stanislawski, L.; Daniau, X.; Lautié, A.; Goldberg, M. Factors responsible for pulp cell cytotoxicity induced by resin-modified glass ionomer cements. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 1999, 48, 277–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, Y.D.; Yang, D.H.; Lee, D.W. A titanium surface-modified with nano-sized hydroxyapatite and simvastatin enhances bone formation and osseointegration. J. Biomed. Nanotech. 2015, 11, 1007–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Lee, Y.H.; Kim, N.K.; Kang, I.K. Bioactive surface of zirconia implant prepared by nano-hydroxyapatite and type I collagen. Coatings 2022, 12, 1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, S.; Haider, A.; Gupta, K.C.; Kim, H.; Kang, I. Chemical bonding of biomolecules to the surface of nano-hydroxyapatite to enhance its bioactivity. Coatings 2022, 12, 999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliva, A.; Della Ragione, F.; Salerno, A.; Riccio, V.; Tartaro, G.; Cozzolino, A.; D'Amato, S.; Pontoni, G.; Zappia, V. Biocompatibility studies on glass ionomer cements by primary cultures of human osteoblasts. Biomater. 1996, 17, 1351–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, D.; Gittings, J.P.; Turner, I.G.; Bowen, C.R.; Bastida-Hidalgo, A.; Cartmell, S.H. Polarization of hydroxyapatite: Influence on osteoblast cell proliferation. Acta Biomater. 2010, 6, 1549–1554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, M.R. Von Kossa and his staining technique. Histochem. Cell Biol. 2021, 156, 523–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.S.; Chang, J.H.; Srimaneepong, V.; Wen, J.Y.; Tung, O.H.; Yang, C.H.; Lin, H.C.; Lee, T.H.; Han, Y.; Huang, H.H. Improving the in vitro cell differentiation and in vivo osseointegration of titanium dental implant through oxygen plasma immersion ion implantation treatment. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2020, 399, 126125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Ingredient | Chemical formular | Molar ratio | 50 mmol (amount used in the experiment) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tetraethylorthosilicate | Si(OC2H5)4 | 2.133 | 23.89 ml |

| Ammoniumdihydrogen phosphate | NH4H2PO4 | 0.160 | 0.92 g |

| Fluorosilicic acid | H2SiF6 | 0.167 | 2.95 ml |

| Aluminum nitrate | Al(NO3)3 | 2.200 | 41.27 g |

| Calcium nitrate | Ca(NO3)3 | 1.000 | 11.81 g |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).