Submitted:

12 January 2025

Posted:

13 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

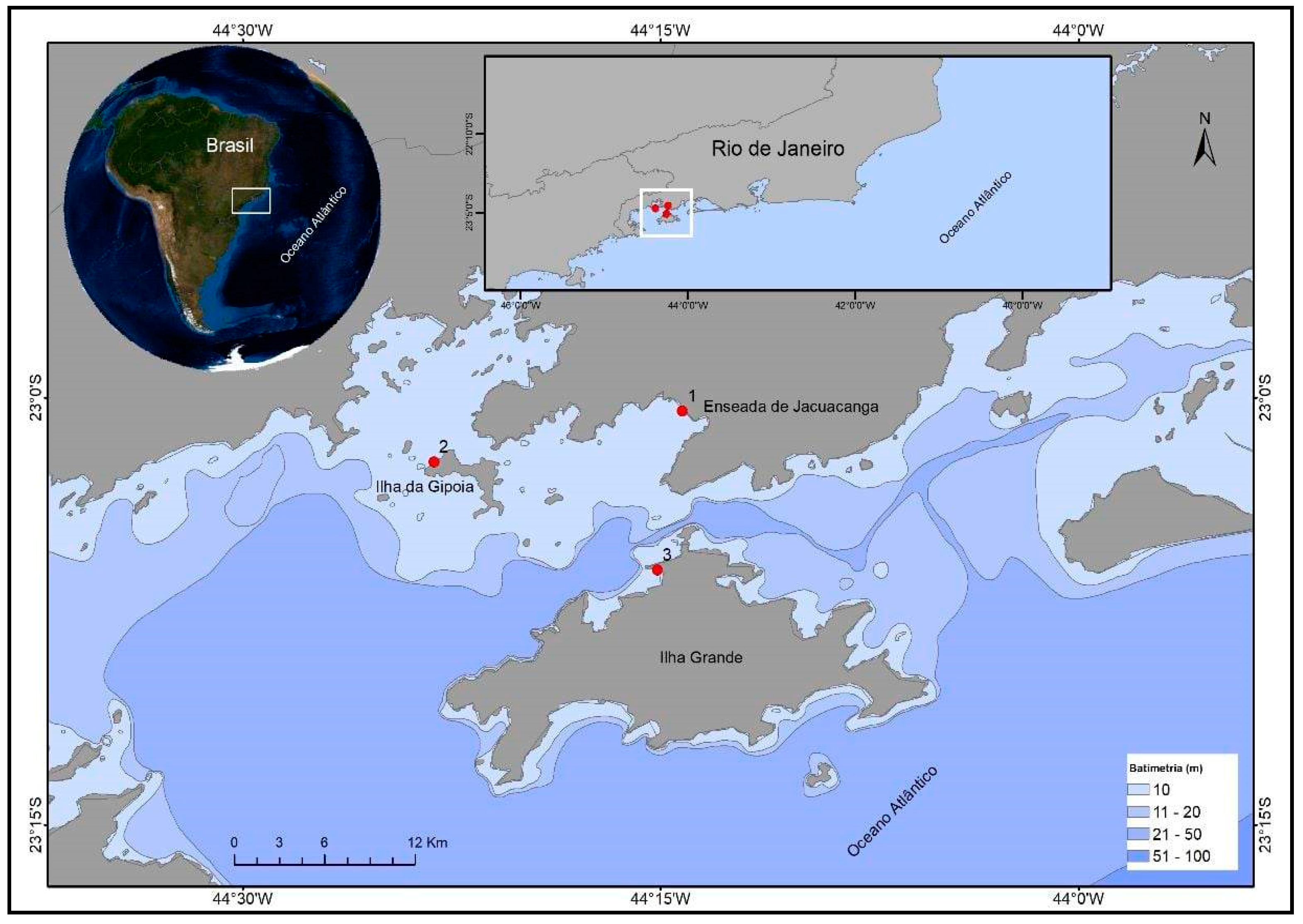

2.1. Sample Collection

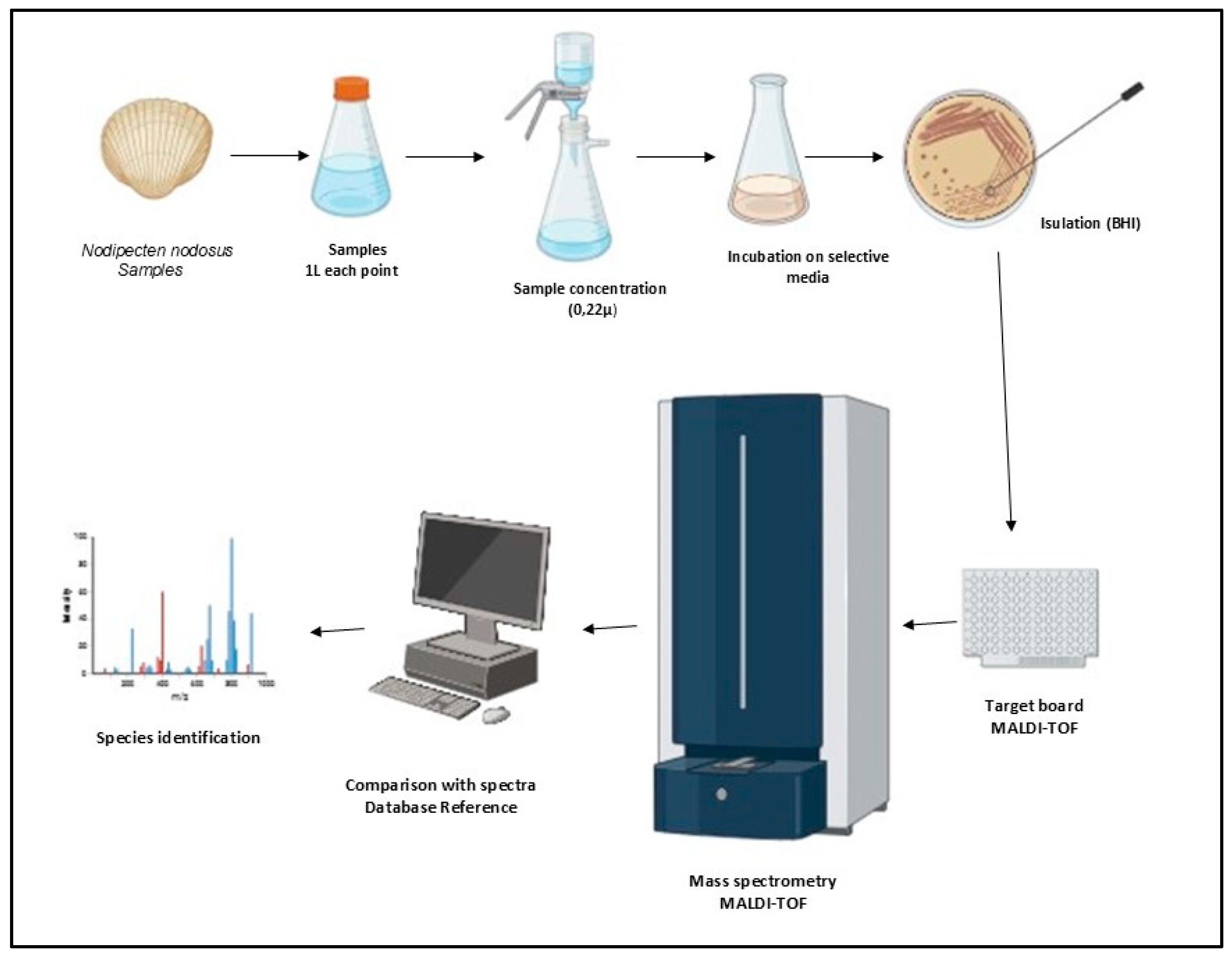

2.2. Sample Preparation

2.3. Sample Processing

2.4. Criteria for Classifying Samples

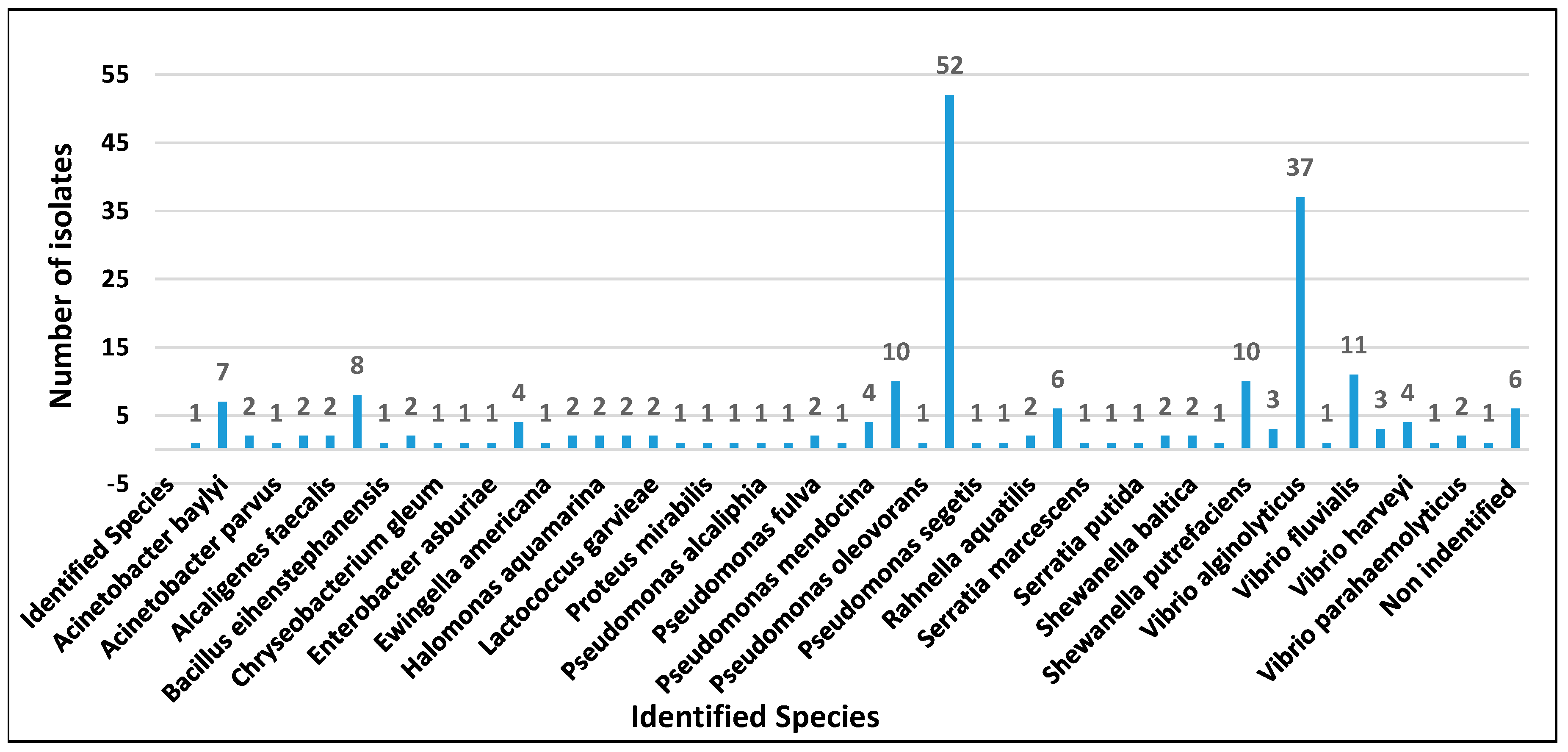

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Determination of the Antimicrobial Susceptibility Profile

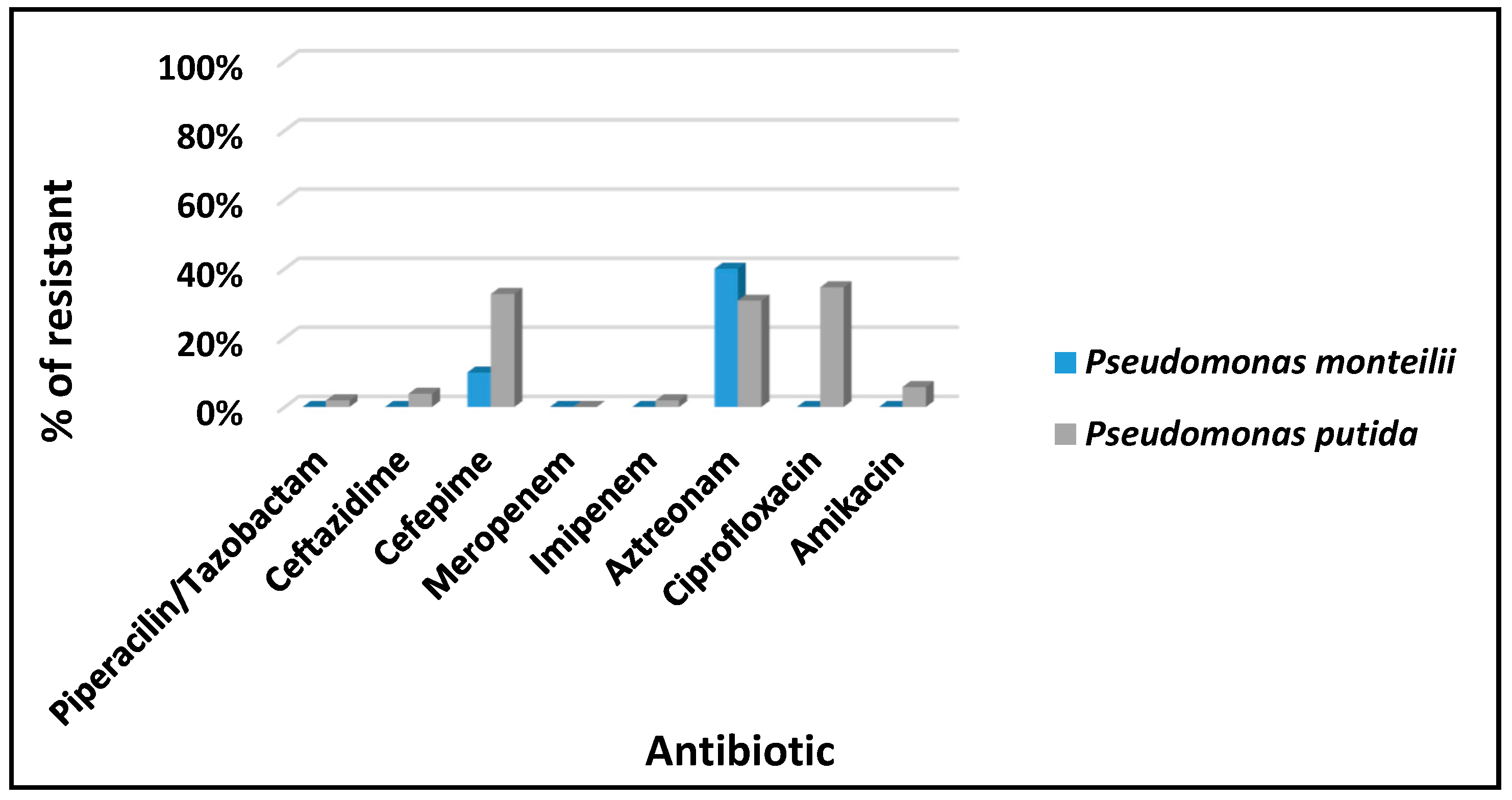

3.2. Antimicrobial Susceptibility: Pseudomonas spp.

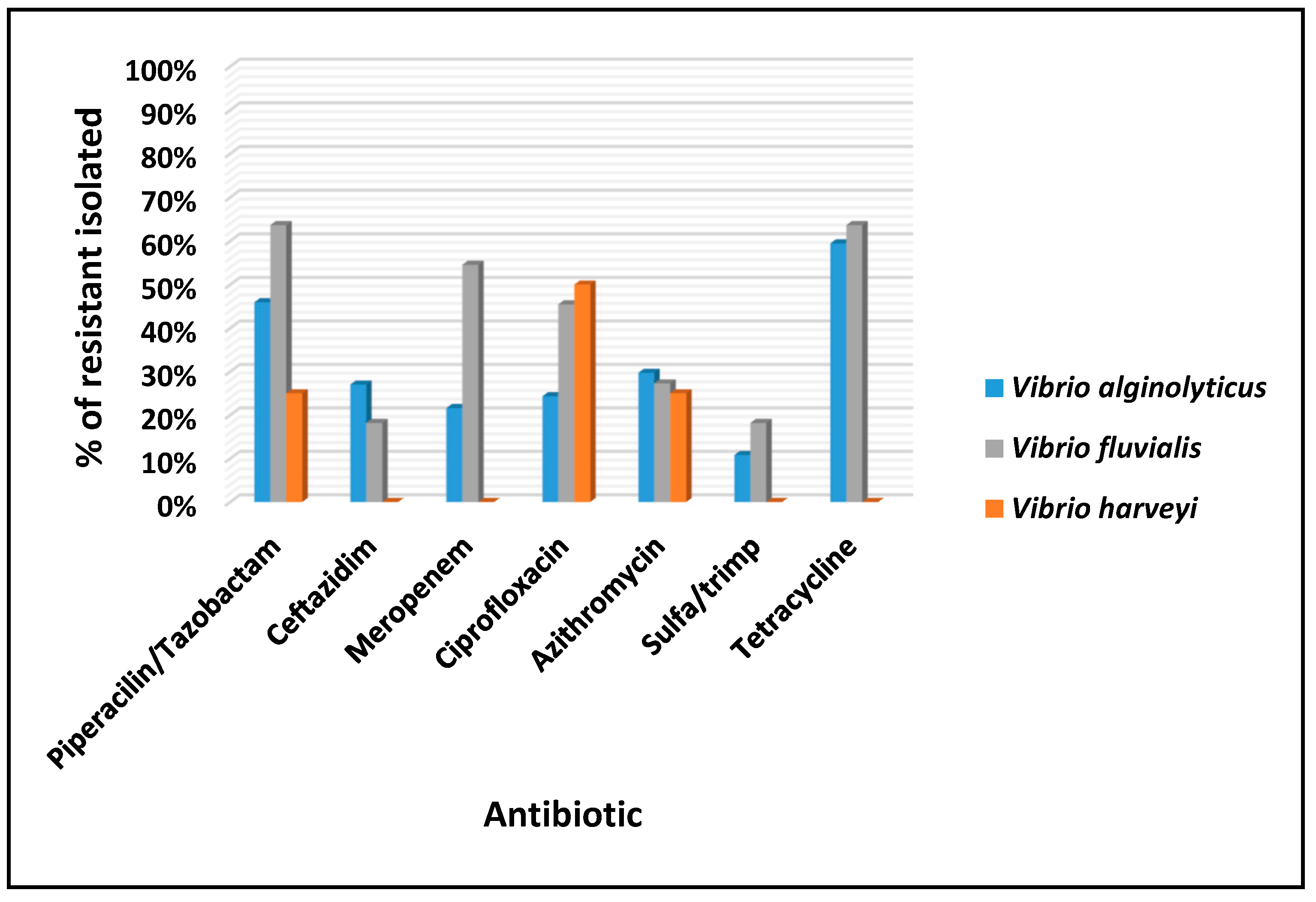

3.3. Susceptibilidade aos Antimicrobianos: Vibrio spp.

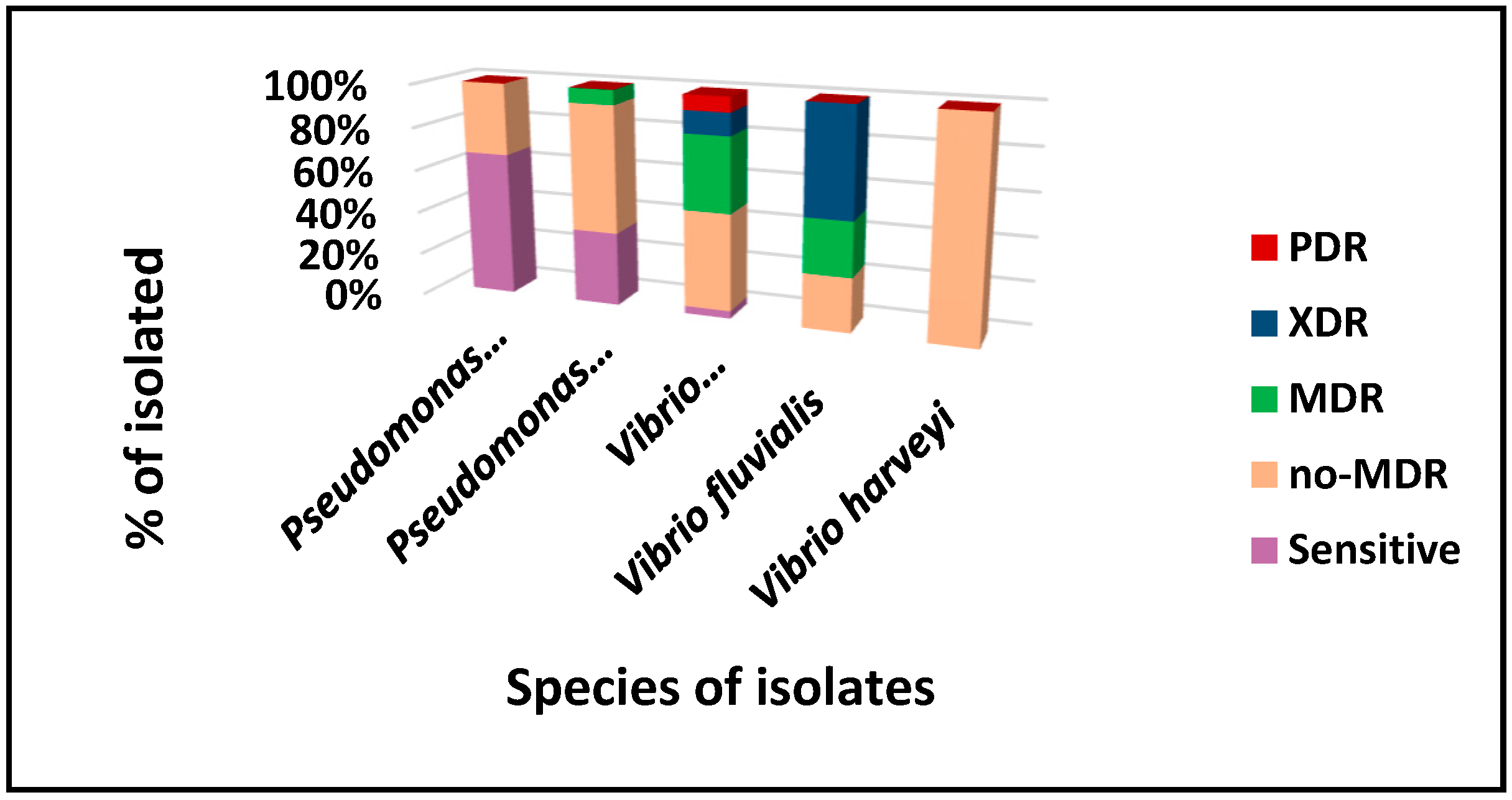

3.4. Assessment of Antimicrobial Susceptibility Profile

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Linnaeus C (1758) Systema naturae per regna tria naturae, secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis. Editio decima, reformata [10th revised edition], Laurentius Salvius: Holmiae 1758, 824. [CrossRef]

- Rupp. G.S.; Parsons, G.J. Aquaculture of the Scallop Nodipecten nodosus in Brazil. Develop Aquacult Fisheries Sci 2016, 40, 999–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson C, Bacha L, Paz PHC, de Assis Passos Oliveira M, Oliveira BCV, Omachi C, Chueke C, de Lima Hilário M, Lima M, Leomil L, et al., Collapse of scallop Nodipecten nodosus production in the tropical Southeast Brazil as a possible consequence of global warming and water pollution. Sci Total Environ 2023, 904, 166873. 904. [CrossRef]

- de Abreu Corrêa, A.; Huaman, M.E.D.; Siciliano, G.M.; Silva, R.R.E.; Zaganelli, J.L.; Pinto, A.M.V.; Dos Santos, A.L.; Vieira, C.B. First investigation of Ostreid herpesvirus-1 and human enteric viruses in a major scallop production area in Brazil. Environ Monit Assess 2024, 196, 1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beeby, A. What do sentinels stand for? Environ Pollut. 2001, 112, 285–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Qu, P.; Fu, F.; Tennenbaum, N.; Tatters, A. O.; Hutchins, D.A. Understanding the blob bloom: warming increases toxicity and abundance of the harmful bloom diatom Pseudo-nitzschia in California coastal waters. Harmful Algae 2017, 67, 36–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco, J.; Moroño, Á.; Arévalo, F.; Correa, J.; Salgado, C.; Rossignoli, A. E.; Lamas, J. P. Twenty-five years of domoic acid monitoring in Galicia (NW Spain): Spatial, temporal and interspecific variations. Toxins 2021, 13, 756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scanes, E.; Byrne, M. Warming and hypoxia threaten a valuable scallop fishery: a warning for commercial bivalve ventures in climate change hotspots. Glob Chang Biol 2023, 29, 2043–2045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomasetti, S.J.; Hallinan, B.D.; Tettelbach, S.T.; Volkenborn, N.; Doherty, O.W.; Allam, B.; Gobler, C.J. Warming and hypoxia reduce the performance and survival of northern bay scallops (Argopecten irradians irradians) amid a fishery collapse. Glob Chang Biol 2023, 9, 2092–2107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lattos, A.; Chaligiannnis, I.; Papadopoulos, D.; Giantsis, I. A.; Petridou, E.I.; et al. How safe to eat are raw bivalves? Host pathogenic and public health concern microbes within mussels, oysters, and clams in Greek markets. Foods 2021, 10, 279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sallenave-Namont, C.; Pouchus, Y. F.; Du Pont, R. T.; Lassus, P.; Verbist, J. F. Toxigenic saprophytic fungi in marine shellfish farming areas. Mycopathologia 2000, 149, 21–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potasman, I.; Paz, A.; Odeh, M. Infectious outbreaks associated with bivalve shellfish consumption: a worldwide perspective. Clin Infect Dis 2002, 35, 921–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pereira, C.S.; Possas, C. de A.; Viana, C.M.; Rodrigues, D. dos P. Vibrio spp. Isolated from fresh and pre-cooked mussels (Perna perna) from the Experimental Cultivation Station, Rio de Janeiro, RJ, Brazil. Food Sci Technol 2007, 27, 387–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leal, D.A.G; Franco, R.M.B. Bivalve mollusks intended for human consumption with vectors of pathogenic protozoa: Detection methodologies and control standards. Rev Panam Infectol 2018, 10, 48–57. [Google Scholar]

- Lévesque, B.; Barthe, C.; Dixon, B. R.; Parrington, L. J.; Martin, D.; Doidge, B. , Proulx, J. F.; Murphy, D. Microbiological quality of blue mussels (Mytilus edulis) in Nunavik, Quebec: a pilot study. Can J Microbiol 2010, 56, 968–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, A.L. dos, Hauser-Davis, R.A., Santos, M.J.S., De-Simone, S.G. Potentially toxic filamentous fungi associated to the economically important Nodipecten nodosus (Linnaeus, 1758) scallop farmed in southeastern Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Mar Pollut Bull 2017, 115, 75–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mau, A.; JHA, R. Aquaculture of two commercially important mollusks (abalone and limpet): existing knowledge and future prospects. Rev Aquicul 2018, 10, 611–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijsman, J.W.M.; Troost, K.; Fang, J.; Roncarati, A. Global Production of Marine Bivalves. Trends and Challenges. In: Smaal, A.; Ferreira, J.; Grant, J.; Petersen, J.; Strand, Ø. (eds) Goods and Services of Marine Bivalves. Springer, Cham. 2019. [CrossRef]

- FAO. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture 2022: Towards Blue transformation. p. 236. Rome, 2022. Available online: https://openknowledge.fao.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/a2090042-8cda-4f35-9881-16f6302ce757/content.

- Garbossa, L.H.; Souza, R.V.; Campos, C.J.; Vanz, A.; Vianna, L.F.; Rupp, G.S. Thermotolerant coliform loadings to coastal areas of Santa Catarina (Brazil) evidence the effect of growing urbanization and insufficient provision of sewerage infrastructure. Environ Monit Assess 2017, 189, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Souza, R.V.; De Campos C., J.A.; Garbossa, L.H.P.; Vianna, L.F.N.; Seiffert, W.Q. Optimizing statistical models to predict faecal pollution in coastal areas based on geographic and meteorological parameters. Mar Pollut Bull 2018, 129, 284–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Souza, R.V.; De Campos, C.J.A.; Garbossa, L.H.P.; Seiffert, W.Q. Developing, cross-validating and applying regression models to predict the concentrations of faecal indicator organisms in coastal waters under different environmental scenarios. Sci Total Environ 2018, 630, 20–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, M.M.; Soares, H.K.S.S.; Souza, A.M.; Bezerra, N.P.C.; Cantanhede, S.P.D.; Souza Serra, I.M.R. Mapping of the world scientific production on bacterial and fungal microbiota in mollusks. Lat Am J Aquat Res 2023, 51, 268–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lino, A.S.; Galvão, P.M.A.; Longo, R.T.L.; Azevedo-Silva, C.E; Dorneles, P.R.; Torres, J.P.M.; Malm, O. Metal bioaccumulation in consumed marine bivalves in Southeast Brazilian coast. J Trace Elem Med Biol, 2016, 34, 50–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coleman, S.; Kiffney, T.; Tanaka, KR.; Morse, D.; Brady, D.C. Meta-Analysis of growth and mortality rates of net cultured sea scallops across the North Atlantic. Aquaculture 2022, 546, 737392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler AJ, Thomas MK, Pintar KD. Expert elicitation as a means to attribute 28 enteric pathogens to foodborne, waterborne, animal contact, and person-to-person transmission routes in Canada. Foodborne Pathog Dis 2015, 12, 335–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, A.L.; Medeiros, J.V.F.; Grault, C.E.; Santos, M.J.S.; Souza, A.L.A.; Carvalho, R.W. The fungus Pestalotiopsis sp., isolated from Perna perna (Bivalvia: Mytilidae) cultured on marine farms in Southeastern Brazil and destined for human consumption. Marine Pollut Bull 2020, 153, 110976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Organization for Animal Health (WOAH). Manual of diagnostic tests for aquatic animals. (2021). Available online: https://www.oie.int/en/what-we-do/standards/codesand-manuals/aquatic-manual-online-access/.

- Garnier, M.; Labreuche, Y; Nicolas, J. L. Molecular and phenotypic characterization of Vibrio aestuarianus subsp. Francensis subsp nov, a pathogen of the oyster Crassostrea gigas. Syst Appl Microbiol 2008, 31, 358–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ottaviani, D.; Parlani, C.; Citterio, B.; Masini, L.; Leoni, F.; Canonico, C.; Sabatini, L.; Bruscolini, F.; Pianetti, A. Putative virulence properties of Aeromonas strains isolated from food, environmental and clinical sources in Italy: a comparative study. Int J Food Microbiol 2011, 144, 538–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borzykh, O.G. , Zvereva, L.V. Comparison of fungal complexes of Japanese scallop Mizuhopecten yessoensis (Jay, 1856) from different areas in the Peter the Great Bay of the Sea of Japan. Microbiology 2014, 83, 684–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwan, T.N.; Bolch, C.J. Genetic diversity of culturable Vibrio in an Australian blue mussel Mytilus galloprovincialis hatchery. Dis Aquat Organ 2015, 116, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dos Santos, A.L.; de Medeiros, J.V.F.; Grault, C.E.; Santos, M.J.S.; Souza, A.L.A.; de Carvalho, R.W. The fungus Pestalotiopsis sp., isolated from Perna perna (Bivalvia:Mytilidae) cultured on marine farms in Southeastern Brazil and destined for human consumption. Mar Pollut Bull 2020, 153, 110976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silveira, C.S.D.; Sousa, O.V.D.; Evangelista-Barreto, N.S. Propagation of antimicrobial resistant Salmonella spp. in bivalve mollusks from estuary areas of Bahia, Brazil. Rev Caatinga 2016, 29, 450–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eliseikina, M.G.; Beleneva, I.A.; Kukhlevsky, A.D.; Shamshurina, E.V. Identification and analysis of the biological activity of the new strain of Pseudoalteromonas piscicida isolated from the hemal fluid of the bivalve Modiolus kurilensis (F. R. Bernard, 1983). Arch Microbiol 2021, 203, 4461–4473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, C.; Bacha, L.; Paz, P. H. C.; Oliveira, M. de A. P.; Oliveira, B. C. V.; Chueke, C. O. C.; Hilário, M. de L.; Lima, M.; Leomil, L.; Felix-Cordeiro, T.; et al., Collapse of scallop Nodipecten nodosus production in the tropical Southeast Brazil as a possible consequence of global warming and water pollution. Sci Total Environm 2023, 904, 166873. [CrossRef]

- Cai, S.-H.; Wu, Z.-H.; Jian, J.-C; Lu, Y.-S. Cloning and expression of gene encoding the thermostable direct hemolysin from Vibrio alginolyticus strain HY9901, the causative agent of vibriosis of crimson snapper (Lutjanus erythopterus). J Appl Microbiol 2007, 103, 289–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amézquita-López, B.A.; Soto-Beltrán, M.; Lee, B.G.; Yambao, J.C.; Quiñones, B. Isolation, genotyping and antimicrobial resistance of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli. J Microbiol Immunol Infect 2018, 51, 425–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Instituto Brazileiro de Geografia e Estatística (IBGE), 2021. Favelas e Comunidades Urbanas: aglomerados subnormais. Available online: https://www.ibge.gov.br/geociencias/organizacao-do-territorio/tipologiasdo-territorio/15788-aglomerados-subnormais.html.

- World Organization for Animal Health (WOAH). Manual of diagnostic tests for aquatic animals. 2021. Available online: https://www.oie.int/en/what-we-do/standards/codesand-manuals/aquatic-manual-online-access/.

- Brazil, Ministério da Saúde, Microrganismos resistentes aos carbapenêmicos e sua distribuição no Brasil, 2015 a 2022. Secretária de Vigilância em Saúde e Ambiente. Boletim Epidemiológico 2024, 55. Availabre at: Boletim_epidemiologico_SVSA_2_2024.pdf.

- BraziL. Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock and Food Supply. Secretariat of Agricultural Defense (MAPA/DAS). Ordinance No. 171, of December 13, 2018. Informs about the intention to prohibit the use of antimicrobials for the purpose of additives to improve food performance and opens a period for manifestation. Official Gazette of the Federative Republic of Brazil. Brasília, 2018.

- Thompson C, Bacha L, Paz PHC, de Assis Passos Oliveira M, Oliveira BCV, Omachi C, Chueke C, de Lima Hilário M, Lima M, Leomil L, et al., Collapse of scallop Nodipecten nodosus production in the tropical Southeast Brazil as a possible consequence of global warming and water pollution. Sci Total Environ 2023, 904, 166873. [CrossRef]

- MAPA 2012. Brazil. Ministry of Fisheries and Aquaculture. Interministerial Normative Instruction MPA/MAPA No. 7, of May 8, 2012. Institutes the National Program for Hygienic-Sanitary Control of Bivalve Molluscs (PNCMB) establishes the Procedures for its implementation and contains other provisions. Official Gazette [of the] Federative Republic of Brazil. Brasília, 2012.

- APHA. Standard methods for the examination of water and wastewater, 22nd Ed. American Public Health Association: Washington, DC. 2012.

- AOAC. Official methods of analysis. 16th Edition, Association of Official Analytical Chemists: Washington, DC. 1995.

- EUCAST. The European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. Breakpoint tables for interpretation of MICs and zone diameters. Version 10.0, 2020 (valid from 2020-01-01). Available online: http://www.eucast.org/fileadmin/src/media/DFs/EUCASTfiles/Breakpoint.tables/v_10.0_Breakpoint_Tables.pdf.

- Mohammed, S.E.; Hamid, O.M.; Ali, S.S.; Allam, M.; Elhussein, A.M. Prevalence of multidrug-resistant, extensively drug-resistant and pandrug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa clinical isolates in Khartoum State, Sudan. Am J Infect Dis Microbiol 2023, 11, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neill, J. Tackling drug-resistant Infections globally: Final report and recommendations. Review on antimicrobial resistance. Welcome Trust and HM Government. Arch Pharm Practice 2016, 7, 110, Available at: https://www.scirp.org/reference/references papers? referenceid= 2618400.. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. Cholera. 2017. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/cholera.

- Marathe, N.P.; Regina, V.R.; Walujkar, S.A.; Charan, S.S.; Moore, E.R.; Larsson, D.G.; Shouche, Y.S. A treatment planreceiving wastewater from multiple bulk drug manufacturers is a reservoir for highly multidrug resistant integron-bearing bacteria. PLoS One 2013, 8, e77310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettibone, G.W.; Mear, J.P.; Sampsell, B.M. Incidence of antibiotic and metal resistance and plasmid carriage in Aeromonas isolated from brown bullhead (ictalurus nebulosus). Lett Appl Microbiol 1996, 23, 234–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathak, S.P.; Gopal, K. Occurrence of antibiotic and metal resistance in bacteria from organs of river fish. Environ Res 2005, 98, 100–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rolain, J.M. Food, and human gut as reservoirs of transferable antibiotic resistance encoding genes. Front Microbiol 2013, 4, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volke, D.C.; Calero, P.; Nikel, P. I. Pseudomonas putida . Trends Microbiol 2020, 28, 512–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nelson, K.E.; Weinel, C.; Paulsen, I.T.; Dodson, R.J.; Hilbert, H.; Martins dos Santos, V.A.P.; Fouts, D. E.; Gill, S.R.; Pop, M.; Holmes, M.; et al. Complete genome sequence and comparative analysis of the metabolically versatile Pseudomonas putida KT2440. Environ Microbiol 2002, 4, 799-808. doi: 10.1046/ j.1462-2920.2002.00366.x. Erratum in: Environ Microbiol 2003, 5, 630. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Livermore, D. M. Multiple mechanisms of antimicrobial resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: our worst nightmare? Clin Infect Dis 2002, 34, 634–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magiorakos, A.P.; Srinivasan, A.; Carey, R.B.; Carmeli, Y.; Falagas, M.E.; Giske, C.G.; Harbarth, S.; Hindler, J.F.; Kahlmeter, G.; Olsson-Liljequist, B.; et al. , Multidrug-resistant, extensively drug-resistant and pan drug-resistant bacteria: an international expert proposal for interim standard definitions for acquired resistance. Clin Microbiol Infect 2012, 18, 268–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Duin, D.; Paterson, D.L. Multidrug-resistant bacteria in the community: trends and lessons learned. Infect Dis Clin North Am 2016, 30, 377–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Baño, J.; Alcalá, J.C.; Cisneros, J.M.; Grill, F.; Oliver, A.; Horcajada, J.P.; Tórtola, T.; Mirelis, B.; Navarro, G.; Cuenca, M.; et al. , Community infections caused by extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli. Arch Intern Med 2008, 168, 1897–1902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, D.J.; Moehring, R.W.; Sloane, R.; Schmader, K.E.; Weber, D.J.; Fowlerm-JR, V.G.; Smathers, E.; Sexton, D.J. Bloodstream infections in community hospitals in the 21st century: a multicenter cohort study. PLoS One 2014, 9, e91713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, Z.; Raudonis, R.; Glick, B.R.; Lin, T.J.; Cheng, Z. Antibiotic resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: mechanisms and alternative therapeutic strategies. Biotechnol Adv 2019, 37, 177–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalluf, K. O, Arend, L.N, Wuicik, T.E, Pilonetto, M, Tuon, F.F. Molecular epidemiology of SPM-1-producing Pseudomonas aeruginosa by rep-PCR in hospitals in Parana. Brazil. Infect Genet Evol 2017, 49, 130–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulug, M.; Gedik, E.; Girgin, S.; Celen, M. K.; Ayaz, C. Pyogenic liver abscess caused by community-acquired multidrug resistance Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Braz J Infect Dis 2010, 14, 218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkey, P.M.; Jones, A.M. The changing epidemiology of resistance. J Antimicrob Chemother 2009, 64, i3–i10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Newton, A.; Kendall, M.; Vugia, D.J.; Henao, O.L.; Mahon, B.E. Increasing rates of vibriosis in the United States, 1996-2010: review of surveillance data from 2 systems. Clin Infect Dis 2012, 54s5, S391–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morris-JR, J.G.; Black, R.E. Cholera and other vibrioses in the United States. New Engl J Med 1985, 312, 343–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scallan, E.; Hoekstra, R.M.; Angulo, F.J.; Tauxe, RV.; Widdowson, M.A.; ROY, S.L.; Jones, J.L.; Griffin, P.M. Foodborne illness acquired in the United States--major pathogens. Emerg Infect Dis 2011, 17, 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okoh, A.I.; Igbinosa, E.O. Antibiotic susceptibility profiles of some Vibrio strains isolated from wastewater final effluents in a rural community of the Eastern Cape Province of South Africa. BMC Microbiol 2010, 10, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokashvili, T.; Whitehouse, C.A.; Tskhvediani, A.; Grim, C. J.; Elbaidze, T.; Mitaishvili, N.; Janelidze, N.; Jaiani, E.; Jaley, B. J.; Lashhi, N.; et al. , Occurrence and diversity of clinically important Vibrio species in the aquatic environment of Georgia. Front Public Health 2015, 3, 232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. World Health Organization Global Strategy for Containment of Antimicrobial Resistance 2001. Scanes, E, Bryne, M., Warming and hypoxia threaten a valuable scallop fishery: a warning for commercial bivalve ventures in climate change hotspots. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Canellas, A.L.B. Isolation and characterization of bacteria of the genus Vibrio from the waters of Guanabara Bay, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Advisor: Marinella Silva Laport. 2020. 150f. Undergraduate Course Completion Work (Bachelor’s degree in Biological Sciences) – Paulo de Goés Institute of Microbiology, Federal University of Rio de Janeiro. Rio de Janeiro, 2020. Available online: https://pantheon.ufrj.br/bitstream/11422/17503/a/ALBCanellas.pdf.

- Hackbusch, S.; Wichels, A.; Gimenez, L.; Döpke, H.; Gerdts, G. Potentially human pathogenic Vibrio spp. in a coastal transect: Occurrence and multiple virulence factors. Sci Total Environ 2020, 707, 136113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mechri, B.; Monastiri, A.; Medhioub, A.; Medhioub, M.N.; Aouni, M. Molecular characterization and phylogenetic analysis of highly pathogenic vibrio alginolyticus strains isolated during mortality outbreaks in cultured ruditapes decussatus juvenile. Microb Pathog 2017, 111, 487–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Q.; Liu, M.; Xiao, H.; Wu, S.; Qin, X.; Ke, K.; Li, S.; Mi, H.; Shi, D.; Li, P. Development of novel aptamer-based enzyme-linked apta-sorbent assay (ELISA) for rapid detection of mariculture pathogen Vibrio alginolyticus. J Fish Dis 2019, 42, 1523–1529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, Y.; Zhao, L.; Xu, X.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, J.; Yan, Q.; Huang, L. Mechanisms underlying the virulence regulation of new Vibrio alginolyticus ncRNA Vvrr1 with a comparative proteomic analysis. Emerg Microbes Infect 2019, 8, 1604–1618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Y.; Xu, L.; Chen, H.; Liu, S.; Guo, Z.; Cheng, C.; Ma, H.; Feng, J. Prevalence, virulence genes, and antimicrobial resistance of Vibrio species isolated from diseased marine fish in South China. Sci Rep 2020, 10, 14329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, L.H.; Mutabilib, N.S.A.; Law, J.W.F.; Wong, S.H.; Letchumanan, V. Discovery on antibiotic resistance patterns of Vibrio parahaemolyticus in Selangor reveals carbapenemase-producing Vibrio parahaemolyticus in marine and freshwater fish. Front Microbiol 2018, 25, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeong, H.H.; Kin, J.A.; Jeon, S.J.; Choi, S.S.; Kim, M.K.; YI, H.J.; CHO, S.J.; Kim, I.Y.; Chon, J.W.; Kim, D.H.; et al. , Prevalence, antibiotic-resistance, and virulence characteristics of Vibrio parahaemolyticus in restaurant fish tanks in Seoul, South Korea. Foodborne Pathog Dis 2020, 17, 209–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations). The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture 2020: sustainability in action. p. 224. Rome, 2020. Available online: https://openknowledge.fao.org/server/API/core/bitstreams/170b89c1-7946-4f4d-914a-fc56e54769de/content.

- Loo, K.-Y.; Letchumanan, V.; Law, J.W.-F.; Pusparajah, P.; Goh, B.-H.; AB Mutalib, N.-S.; He, Y.-W.; Lee, L.-H. Incidence of antibiotic resistance in Vibrio spp. Rev Aquacult 2020, 12, 2590–2608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Boeckel, T.P.; Gandra, S.; Ashok, A.; Caudron, Q.; Grenfell, B.T.; Levin, S.A.; Laxminarayan, R. Global antibiotic consumption 2000 to 2010: an analysis of national pharmaceutical sales data. Lancet Infect Dis 2014, 14, 742–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, T.; Jiang, F.; He, M.; Zhang, J.; Zeng, H.; Chen, M.; Pang, R. U.; Wei, L.; Wang, J.; Ding, Y.; Wu, Q. Prevalence, virulence, antimicrobial resistance, and molecular characterization of fluoroquinolone resistance of Vibrio paraemolyticus from different types of food samples in China. Int J Food Microbiol 2020, 317, 108461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, S.Q.; Cabello, F.C.; L'Abée-Lund, T.M.; Tomova, A.; Godfrey, H.P.; Buschmann, A.H.; Sørum, H. Antimicrobial resistance and antimicrobial resistance genes in marine bacteria from salmon aquaculture and non-aquaculture sites. Environ Microbiol 2014, 16, 1310–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Håkonsholm, F.; Lunestad, B.T.; Aguirre Sánchez, J.R.; Martinez-Urtaza, J.; Marathe, N.P.; Svanevik, C.S. Vibrios from the Norwegian marine environment: Characterization of associated antibiotic resistance and virulence genes. Microbiologyopen 2020, 9, e1093–2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; HE, K.; Luo, J.; Sun, J.; Liao, L.; Tang, X.; Liu, Q.; Yang, S. Co-modulation of liver genes and intestinal microbiome of largemouth bass larvae (Micropterus salmoides) during weaning. Front Microbiol 2020, 11, 1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; LI, H.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Liao, M.; Rong, X.; LI, B.; Wang, C.; GE, J.; Zhang, X. Antibiotic resistance, virulence and genetic characteristics of Vibrio alginolyticus isolates from the aquatic environment in coastal mariculture areas in China. Mar Pollut Bull 2022, 185, 114219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.H.; Cheng, W.; Hsu, J.P.; Chen, J.C. Vibrio alginolyticus infection in the white shrimp Litopenaeus vannamei confirmed by polymerase chain reaction and 16S rDNA sequencing. Dis Aquat Org 2004, 61, 169–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohamad, N.; Mohd Roseli, F.A.; Azmai, M.N.A.; Saad, M. Z.; MD Yasin, I.S.; Zuliply, N.A.; Nasruddin, N.S. Natural concurrent infection of Vibrio harveyi and V. alginolyticus in cultured hybrid groupers in Malaysia. J Aquat Anim Health 2019, 31, 88–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Wang, B.; Chen, G.; Jian, J.; Lu, Y.; Xu, Y.; Wu, Z. Transcriptome analysis of the pearl oyster (Pinctada fucata) hemocytes in response to Vibrio alginolyticus infection. Gene 2016, 575, 421–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Ding, Q.; Yang, Q.; Fan, H.; Yu, G.; Liu, F.; Bello, B.K.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, T.; Dong, J.; et al. , Vibrio alginolyticus triggers inflammatory response in mouse peritoneal macrophages via activation of NLRP3 Inflammasome. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2021, 11, 769777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Robles, M.F.; Álvarez-Contreras, A.K.; Juárez-García, P.; Natividad-Bonifacio, I.; Curiel-Quesada, E.; Vázquez-Salinas, C.; Quiñones-Ramírez, E. I. Virulence factors and antimicrobial resistance in environmental strains of Vibrio alginolyticus. Int Microbiol 2016, 19, 191–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, C.H.; Shin, Y.; Jang, S.; Jung, Y.; So, J.S. Antimicrobial susceptibility of vibrio alginolyticus isolated from oysters in Korea. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int 2016, 23, 21106–21112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zavala-Norzagaray, A.A.; Aguirre, A.A.; Velazquez-Roman, J.; Flores-Villaseñor, H.; León-Sicairos, N.; Ley-Quiñonez, C.P.; Hernández-Díaz, L. de J.; Canizalez-Roman, A. Isolation, characterization, and antibiotic resistance of Vibrio spp. in sea turtles from Northwestern Mexico. Front Microbiol 2015, 6, 635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).