Introduction

The domain of Mobile Edge Computing (MEC) has shown a continuous growth in in our daily lives over the past few decades, leading to notable surge in the complexity and scale of embedded system manufacturing. Therefore, the demand for computational resources by mobile users is increasing significantly nowadays [

1,

2]. The amalgamation of MEC with wireless technology has gained tremendous recognition as it is the most viable alternative for the complex applications that have escalated with the advances in computational power over the decades [

3]. Sensors and instruments connected to the clouds through the gateway monitor and control things remotely through mobile phones. The hardware devices can not handle computationally intensive tasks, even in light computational applications, especially when millions of devices operate everywhere and anywhere [

4]. The alternative option to cloud edge appears to be a viable solution. To bridge the gap, cloud computing was the solution offered that increased productivity, speed, and efficiency. The challenge of delays that arose between the users equipage (UE) and the cloud server has raised a question about the feasibility of such recommended alternatives.

The European Telecommunication Standard Institute (ETSI) has proposed a method of placing a small edge server in close proximity to the end-user, referred to as MEC, in the form of a distributed network to minimise latency that is making the recommended methodology delay-sensitive [

5,

6]. The conventional mechanism of offloading has few issues that become a key factors in offloading decisions for MEC. The execution of MEC is compromised by the limited battery duration, storage, memory, and computational capacity of the UEs [

7]. Other crucial factors that are overlooked, include energy efficiency and outlying communication between UEs and remote cloud centres, which lead to latency in on-demand computing.

Research is being conducted to establish a new discipline that combines MEC data execution with wireless energy transfer, incorporating energy harvesting capability in user-equipage (UE) [

8]. Through the Hybrid Access Point (HAP) consisting of a power node and an information access node, the radio frequency signal will deliver energy the Wireless Powered Mobile Edge Computing (WP-MEC) to UE, eventually enhancing the computing capability and addressing issues related with challenges [

9]. The existing literature lacks a comprehensive approach to optimize time allocation between energy harvesting and data transfer in the HAP. Moreover, there is a lack of solutions for reducing the energy consumption and delay inherent in long-distance data transfers to remote cloud centers [

10,

11]. This gap highlights the need for a deep learning methodology that not only manages energy and data operations efficiently but also facilitates offloading tasks to nearby devices or cloudlets with limited resources. Further research is essential to develop and improve these strategies, which promise significant improvements in efficiency and resource management in cloud computing environments.

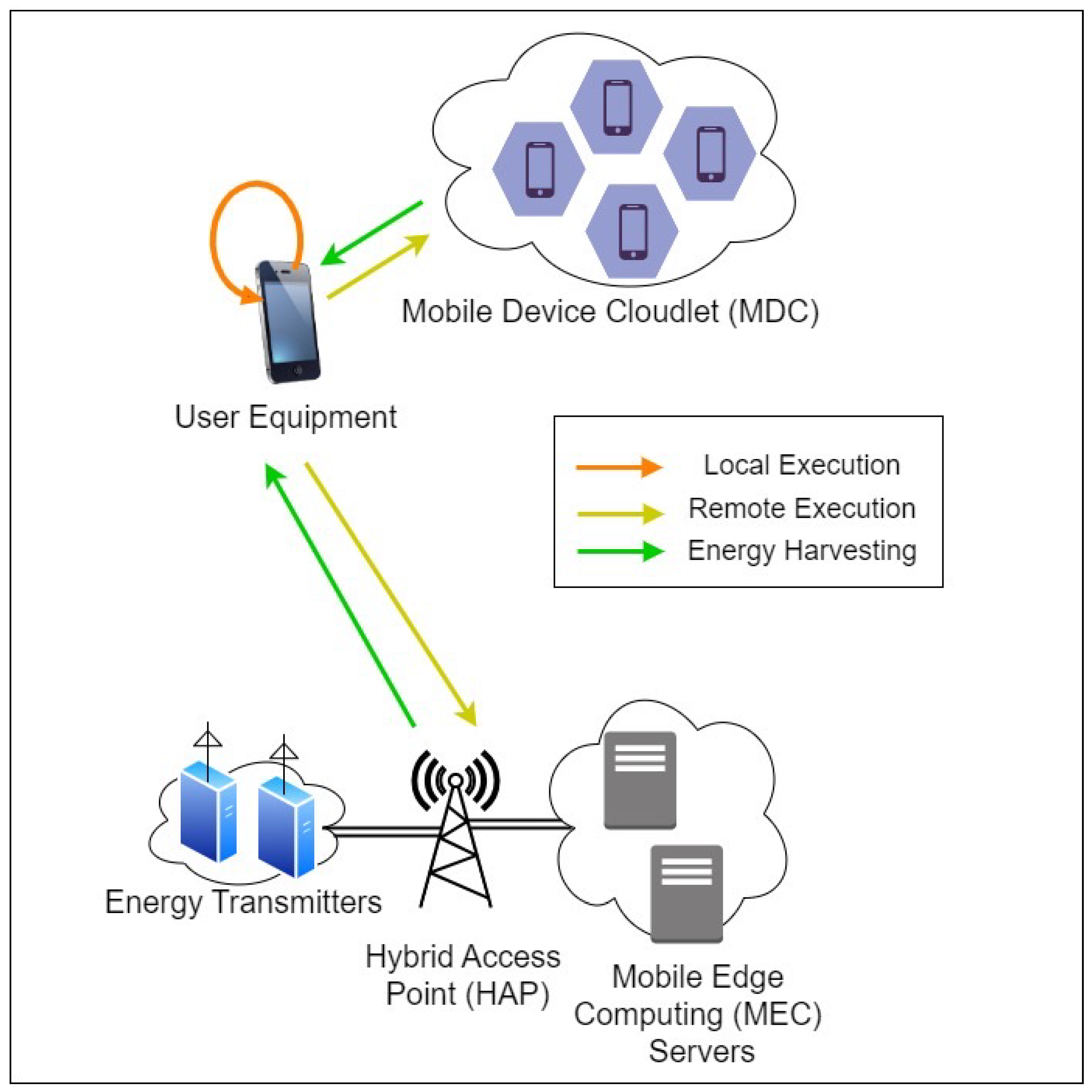

Offloading policies in Mobile Device Cloud include local execution, Mobile Edge Computing (MEC), and Mobile Device Cloud (MDC) execution as shown in

Figure 1. These policies determine how and where computational tasks are processed, either on the mobile device itself or through offloading to nearby servers or device clouds [

9]. This flexibility introduces significant complexity in balancing computational load, energy consumption, and latency [

12]. The primary challenges include optimizing resources allocation to minimize energy consumption, managing latency introduced by data transfer, and efficiently utilizing the available resources in MEC and MDC environments [

13]. This complexity requires sophisticated algorithms to achieve optimal performance, which complicates the implementation and management of offloading strategies. In addition, finding the optimal time allocation for energy harvesting and data transfer adds another layer of difficulty, affecting the overall efficiency and performance of the system [

14].

The methodology adopted in this work is to divide the mobile application into tasks and modules that are offloaded to the nearby external user equipages (UEs). We propose an algorithm that would generate a training dataset to train a deep neural network (DNN) that will simultaneously deduce whether the so partitioned components will be executed locally or offloaded via MEC or MDC as well as to allocate time to the UE for energy harvesting and information transfer. Our dataset simultaneously takes into account offloading policies along with all possible time allocation policies.

To summarize the contribution to improving the mathematical models of previous MEC solutions, the following key factors are presented.

- 1.

Concept of MEC systems integrated with heterogeneous networks and joint time allocation for energy efficient User-equipage (UE) performance. To the best of our knowledge, for the first time, in this is combined the above two concepts of time allocation and offloading to MEC and MDC simultaneously.

- 2.

The proposed technique, named as Joint Time Allocation and Offloading Policies (JTAOP), is compared with three benchmark cases—namely, total local computation, total offloading, and Joint Time Allocation, to demonstrate further the performance in terms of minimum cost, delay, and energy consumption.

- 3.

In the proposed setup, a deep learning approach has been used to integrate the concepts of MEC and MDC for both optimal offloading policy and optimal time fraction for harvesting energy and proposing a deep learning-based algorithm which provides minimum cost, in terms of delay and energy consumption, for computational offloading in MEC and MDC.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 presents the related work and

Section 1 discusses background and problem formulation.

Section 3 provides the mathematical modeling and analysis while

Section 4 explains the proposed algorithm.

Section 5 explains the results and discussion. Finally,

Section 6 concludes the paper and presents suggestions on the future work.

1. Background and Problem Formulation

The proliferation of Internet of Things (IoT) devices has necessitated advanced computational strategies to cope with increasing data processing and energy management requirements. Mobile Edge Computing (MEC) and Mobile Device Cloudlet (MDC) technologies have played pivotal role in enhancing these capabilities. These technologies enable the offloading of computational tasks from IoT devices to edge servers or nearby devices, thus reducing latency and optimizing energy consumption.

Despite these advancements, most current frameworks have primarily focused on MEC, and overlooked the potential integration of MDC [

9,

11]. This oversight restricts the flexibility and applicability of offloading strategies in diverse IoT environments where both MEC and MDC could be beneficial. Typically, offloading decisions in existing models are limited to a three-bit representation. This model is used to delineate different offloading actions based on whether tasks are executed locally or offloaded to an edge server, assuming all tasks are divided into three components.

In the context of OTPMDC Offloading Policies and Time Allocation Policies, there are types of offloading: namely, local, MEC, and MDC. Different combinations of these types constitute the offloading policies.

Time allocation policies follows the same format as shown in

Table 2. However, the authors have only included content for MEC, using three bits for the offloading policy, considering the task is divided into three components,

[

9]. To address this limitation, we have extended the format of offloading policies to

bits to include MDC as well. Therefore, the text in

Table 1 is a combination of the idea from the referenced paper and our own improvisation/contribution.

The bits , , and determine whether it is local or remote execution, while , , and determine whether it is MEC or MDC. If one of the initial three bits is 0, it signifies that local execution will take place, and will become 0 by default. However, if one of the first three bits is set to 1, it denotes remote execution. If the corresponding bit is 0, it is MEC; else it is MDC, if it is 1.

Table 1 shows an example of an offloading policy.

denotes local execution, so

will also have a value of 0 automatically. This means that the first task component will be executed locally. Both

and

equal to 1 will be indicating that these tasks performed remotely.

is the corresponding

bit of

.

has a value of 0 which represents MEC. Therefore, the second task component will be executed on the edges of the server.

is the corresponding

bit of

. While

has a value of 1, which represents MDC. Hence, the execution of the third component will be carried out in a Mobile Device Cloudlet (MDC).

Similarly, the number of possible time allocation policies depends on time resolution,

. For example, if

then there will be

possible time allocation policies, as shown in

Table 2, showing one of these policies will have a minimum cost.

2. Related Work

Enhancement in the performance of UEs has been the interest of many researchers and numerous studies are investigated in computational offloading, each study is featuring a distinctive approach to offloading methodology. There is an additional effort on computational processing and the energy reserves due to the need to calculate the computational cost of each additional unit [

15]. Nevertheless, the technique to use the intelligent approach to select optimal combination of units to decrease the latency, total energy consumption, and the size of data transfer is adopted. An idea has been proposed that allows fog nodes to collaborate on a larger task depending on the pre-determined fog parameters, known as the cooperative edge offloading method [

16]. Accordingly, their approach has been shown to be successful as data is executed in a timely manner at the edge level. However, the energy utilisation of fog nodes has not been considered. The researchers have proposed an improved algorithm in which the limited battery capacity of the UE and reduced power consumption are considered but the work does not consider the combined effect of power usage and time delay [

17]. In another work, the authors proposed an energy-efficient offloading strategy for mobile edge computing in 5G networks, focusing on minimizing energy consumption through optimal task offloading and radio resource management [

18].

Table 3 illustrates various studies that have approached computational offloading, focusing on aspects such as energy consumption, time delay, etc.

The Lyapunov optimization technique converts the offloading policies issue into a series of deterministic algorithms that examine closely the trade-off between energy efficiency and time delay [

19]. Still, the research does not assume a deep learning approach. A wireless offloading policy that determines optimally the offloading decision by adopting the approach of deep learning-based online offloading, considers a binary offloading policy [

20]. This scheme has proven to be a success in improving computational delay. In [

29], the authors have proposed an architecture called MEC system in a heterogeneous network (MECH), which provides energy reduction and improvement in execution time of UE. The application from UE is segregated into tasks, offloaded and activated in the MDC, keeping in view the factors such as routing cost and response time. However, they do not contemplate the time allocation policies.

In another work, the authors developed a dynamic offloading framework for mobile users, considering local overhead on mobile terminals and limited network communication and computation resources [

22]. The offloading decision problem is formulated as a multi-label classification problem, and the Deep Supervised Learning (DSL) method is employed to minimize computation and offloading overhead. However, their work did not consider to address the time allocation and energy harvesting. Using Markov Decision Processes (MDP), the authors formulates cooperative deep learning model inference and proposes a method to adjust sensing data sampling rates based on mobile device and access point communication conditions [

23]. They examined communication technologies and edge computing architectures for deep learning model offloading without comparing different technologies, however, it does not include a comparison of distinct methodologies. A mobile edge computing architecture for computation offloading is introduced, presenting methods for (i) resource optimization, (ii) deep learning model optimization, and 3) joint optimization of resources and deep learning models to support deep learning-based services within MEC frameworks[

24]. Emphasizing the challenges of high computational demands for such services, the study explored how joint optimization can effectively address dynamic network and device environments. However,their work lack to address resource optimization through the allocation of time for offloading and the implementation of energy harvesting techniques.

Similarly, the authors explored wirelessly transferring energy between personal devices and others, envisioning a communal energy resource [

25]. The key design considerations include compliance with international magnetic field guidelines, incentivization, and addressing user behaviour and trust in various collocated interactions. In another work, the researchers explored mobile social energy networks to facilitate battery power sharing among devices [

26]. They analysed the charging habits, identifies inefficiencies, and examines social interactions for power-sharing opportunities. By pairing devices as power-sharing buddies, They addressed the gap between battery capacity advancements and rising energy demand, demonstrating potential savings without altering user behavior.

In another work, the authors proposed an IoT energy services ecosystem for smart cities, leveraging the service paradigm to enable wireless energy crowd-sourcing for IoT device recharging [

27]. The ecosystem, designed for sustainable, ubiquitous, and cost-effective power access, includes three components: environment context, service-oriented architecture, and enabling technologies. Their sustainable approach fosters collaboration among IoT users, extending battery life and reducing carbon footprints by minimizing fossil fuel reliance. An architecture called MEC system in a heterogeneous network (MECH) is proposed, which provides energy reduction and improvement in execution time of UE [

28]. The application from UE is segregated into tasks, offloaded and activated in the MDC, keeping in view the factors such as routing cost and response time. However, they do not contemplate the time allocation policies.

3. Mathematical Modelling and Analysis

Overview

A single UE in a WP-MEC system is considered as shown in

Figure 1, in which the MEC server is connected with hybrid-access point (HAP) fitted with a double antenna, one for energy harvesting and the other for data processing. Such technological developments are utilised for remote controlling and monitoring in the emerging IoT style of internet-connectivity. We consider the tasks in the single UE in the system to be executed on an MDC that is formed by a number of nearby foreign UEs. The proposed model includes an HAP operating in time division duplex mode. We assume that the HAP has the ability to transmit power through RF signals to the UEs and WET technology is fully incorporated in MEC and MDC. The UEs follow the harvest-then-transmit protocol where the device first harvests energy from the HAP and then offloads the task components to the HAP. In the proposed study, it is assumed that the HAP is equipped with sufficient power energy and processing capacity.

In the case of partial offloading,

represents the time allocation policy. The parameters

and

are parts in percentage of one time slot. While

is the percent portion of one time slot in which a UE harvests energy. This means if

is calculated as 0.65 then it means 65% of one time slot will be used for energy scavenging and in the rest of the 35% of the time slot, the UE will transmit the data to the HAP. Therefore,

and

are continuous variables taking values from

. A variable

x for the

i-th component of a task, denoted as

, is a binary variable, that is,

, which is defined to determine the offloading policy. In the case of the battery level being more than 75%, local execution will occur as energy harvesting is not required, given the assumption that computational capability is enough for task execution. In the other case of the battery level

being less than 75%, remote execution will occur. If

is 0, the MEC remote execution is taking place. If

is 1, then MDC remote execution will occur. All the notations used in this work are listed in

Table 4.

3.1. Local Execution

When

is greater than 75%, local execution occurs. The time delay in the local execution model,

, is obtained by Equation (

1) of the relation in [

9].

Where

is the input data size of a component (measured in bytes) and

L is measured in cycles/byte (cpb). This

L indicates the number of clock cycles a microprocessor will use per byte of data processed in an algorithm. The parameter depends on the nature of the component and the complexity of the algorithm and

represents the frequency of UE. The energy consumption in this model is calculated as Equation (

2).

where

is defined as the effective switching capacitance factor which depends on chip architecture.

represents the computing power of the UE.

3.2. Remote Execution

Alternatively, when is less than 75%, remote execution will occur. The parameter will determine whether the task will be offloaded to the server, MEC, or it will be offloaded Mobile device cloudlet (MDC). For remote execution, when considering small scale fading channel power gain , independent and identically distributed (i.i.d.) channel fading is assumed. The channel power gain is , where is path loss and is reference distance. d equals in the case of MEC and equals in the case of MDC, where is the distance between UE and HAP of MEC and is the distance between UE and HAP of MDC.

3.2.1. MEC Remote Execution

In the case that

for the

i-th component of a task, the executed data offloads the components of the task to HAP for high processing power. For simplicity, it is assumed that MEC has strong computing capabilities and HAP has a high transmission capacity. This renders the downloading delay from HAP to UE negligible, implying

. Using the Shannon–Hartley theorem, the data rates can be calculated as given in Equation (

3) and Equation (

4).

and

Where

shows the noise spectral density for the uplink, and the available bandwidth is represented by

B. In order to obtain the time delay in the remote execution model, we consider the uplink time (time for data transmission), the downlink time (time for data reception), and the processing time in MEC. The time delay in transferring data from UE to MEC is represented by

, and is calculated as in Equation (

5).

Similar to uplink, the downlink delay time,

, is calculated as in Equation (

6).

The time for the processing of data in MEC is represented as

and is calculated as given in Equation (

7).

The total time delay,

, for component

i, is calculated as given in Equation (

8)

It is worth mentioning that, as the frequency at MES is high, the time delay for the execution of data at HAP can be neglected. Moreover,

, which is the output data at MEC, is small as compared to input data

, which renders the downlink time delay also negligible. Therefore, we can write as given in Equation (

9).

3.2.2. MDC Remote Execution

In the case that

for the

i-th component of a task, the executed information offloads the units of a task to HAP for high computational capacity. Throughout we have assumed that MDC has strong processing power and HAP has sturdy communication ability. The consequence of this makes the downloading latency insignificant between HAP and UE, implying

.

is the noise spectral density for the uplink and

B is considered to be the available bandwidth. Implementing the Shannon–Hartley theorem, the data rates can be calculated as given in Equation (

10) and Equation (

11) respectively.

and

To calculate the time delay in the remote execution model, we have considered the uplink time (time for data transmission), the downlink time (time for data reception), and the processing time in MDC. The time delay in transferring data from UE to MDC is represented by

as given in Equation (

12).

Similar to uplink, the downlink delay in duration,

, is calculated as given in Equation (

13).

The duration for the processing of data in MDC is represented as

, and is calculated as given in Equation (

14).

The total time delay,

, for component

i, is calculated as given in Equation (

15).

It is worth mentioning that, as the frequency at MES is high, the time delay for the execution of data at HAP can be neglected. Moreover,

, which is the output data at MDC, is small as compared to input data,

, which renders the downlink time delay also negligible. Therefore, we can write given in Equation (

16).

3.3. Total Whole Task Execution

The total time delay,

, can thus be calculated given in Equation (

17).

The energy consumption of the UE for input data,

, in this model, denoted as

, is calculated as given in Equation (

18)

Thus, the energy scavenged by the UE,

, is defined as given in Equation (

19).

The energy consumed by the UE for

is the sum of consumed energies in the local and remote models, and is given asgiven in Equation (

20).

For a meaningful comparison of our proposed technique with the benchmark techniques, we model the cost function,

for optimal time allocation and offloading policy, that considers energy consumption and time delay simultaneously, as given in Equation (

21).

where

and

where

and show the maximum energy consumed and time delay for the whole task, respectively, which are taken as constants for all components of a task. The parameters and represent the weight variants that are also optimized depending on the battery capacity of the UE.

4. Optimizing Offloading and Time Allocation with Deep Learning

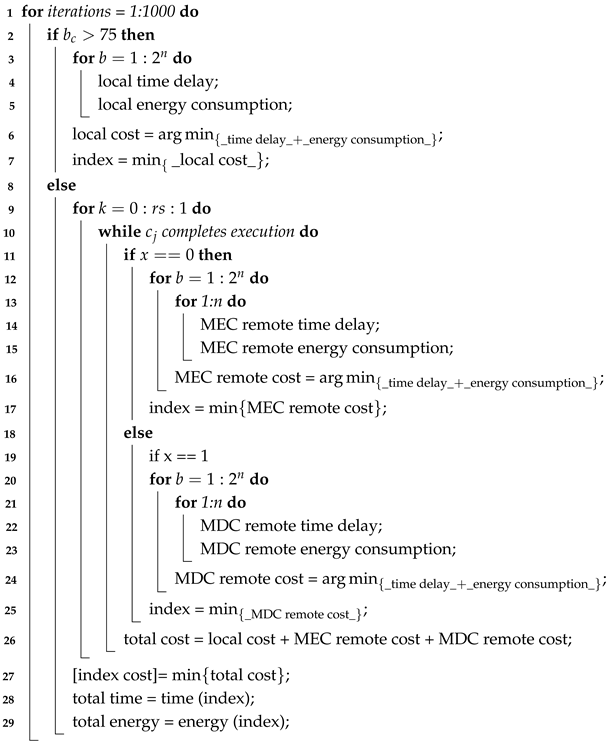

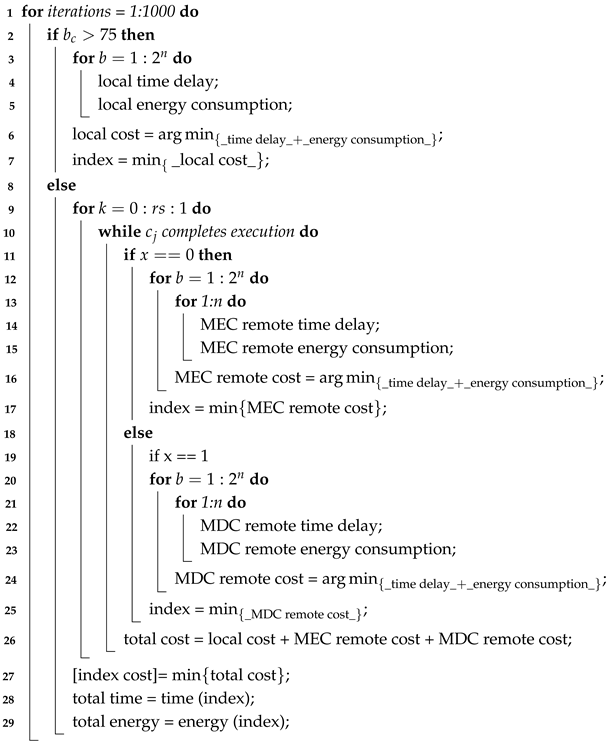

Algorithm 1 is designed and named as Offloading and Time Allocation Policy using MDC and MEC (OTPMDC). The algorithm basically processes the generation of input and output datasets for neural network training. Deep learning out of all the available artificial intelligence options, is chosen for its features of its high performance in terms of accuracy and its capability to handle complex computations in OTPMDC due to a large number of input neurons.

|

Algorithm 1: Offloading and Time Allocation Policies MDC and MEC |

Input: , , , , ,

|

Output: cost

|

|

cost = ; |

Save corresponding input data ; |

Save corresponding label ; |

Repeat for different task sizes; |

Train DNN ; |

Test Training DNN; |

For each unit, u, six parameters are considered in this algorithm. Size of each unit, frequency of the user equipage (UE) for execution, transmit power of UE, distance between UE and MEC, distance between UE and MDC, and battery capacity are generated randomly and stored in an array as input. The column size of the input array is where n is the number of units and 6 is the number of parameters. If the battery level of the UE is higher than 75%, it is assumed that the UE has the required computational power. Local computing takes place, and hence cost is calculated for local computing only as per the mathematical model. On the other hand, if the battery level does not fulfill the check conditions, remote computing takes place. If the random variable x has the value of ’0’, MEC cost is calculated and if x has the value of ’1’, MDC cost is calculated as per the mathematical model.

If the divided unit is locally executed, only the mathematical formulas for local computing are considered and calculated. However, if the unit is to be executed by remote computing, the time resolution is also taken into account in the mathematical calculations for both MEC and MDC and hence, the equations for remote computing are used for every possible time allocation policy. Cost is also calculated at every step and at the end, the indices of the minimum cost are saved to trace back the elements of the output array of offloading policies and time allocation policies.

The inputs and outputs are fed to the deep learning neural network with training, validation and testing data as 70%, 15% and 15% respectively. The outcome of the training of the deep neural network is with high accuracy whereas the output dataset our proposed approach when compared with previously used methods shows better efficiency and performance.

The format of the data that is feed as an input to our algorithm is as listed

Table 5, considering that the task is divided into

components. This makes the input column size to the algorithm as

. As a result 1000 random values under each column have been generated so rows = 1000. The algorithm calculates the minimum cost for the random input values and adds another column, named as Minimum Cost, which makes the column size

.

The algorithm also outputs offloading policies and time allocation policies as shown in

Table 6. Considering

, the column size of offloading policies is

, as given in

Table 1.

The number of time allocation policies depends on the value of

. For example, if

, then there will be

possible time allocation policies. In the coding phase, 11 policies are represented in a one-hot encoding format as listed in

Table 7 . Only the variable ,

, is included as an output, from which

is automatically calculated. For instance, in the 7th policy shown in

Table 2, where

and

, the output is encoded such that the 7th column has a value of ’1’, with all other columns set to ’0’.

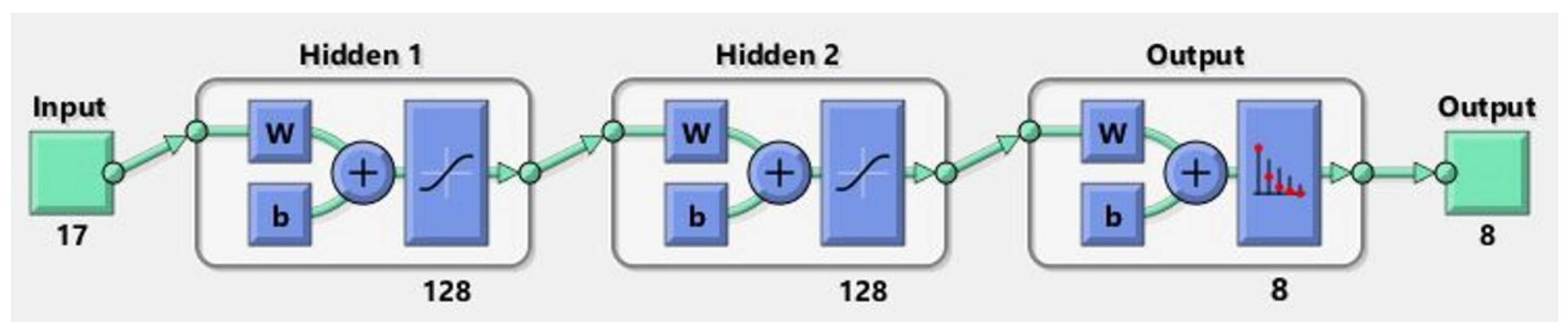

Regarding the Deep Neural Network (DNN) model, the input to the model consists of parameters, including all relevant parameters, battery capacity, and minimum cost. The output of the model is , which includes the offloading and time allocation policies.

We set

and

, resulting in 17 input neurons and 8 output neurons, as shown in

Figure 2. The network architecture comprises two hidden layers with 128 neurons each. The activation functions utilized are the default functions provided by MATLAB’s Neural Network Pattern Recognition Tool (nprtool), specifically

tansig for the hidden layers and

softmax for the output layer accordingly.

5. Results and Discussion

The simulations results for the optimal time allocation and offloading policies. Each task is divided into three components. The task size is considered as a uniform distribution in [0.1, 1] gigabit. The value of CPU cycles to process one bit of data is taken as 737.5 cycles per bit. The frequency of the UE is considered as a uniform distribution in [0.1, 1] GHz (see

Table 8 for simulation parameters). For simulation purposes only and to check the effect of the mobility in the training dataset, the distance between HAP and the UE for MEC is taken as a uniform distribution in the 100-300m range and the distance between HAP and UE for MDC is taken as a uniform distribution in the 100-300m rangem. However, the training dataset can be generated for any suitable range of distances between HAP and the UEs. The effective switching capacitance is taken as

. Efficiency

of UE is taken as 0.8.

is taken as

dB,

, and

. The available bandwidth is taken as 0.5 MHz. The noise spectral density

is

dBm/Hz. The weighing constants are taken as 0.5. The offloading transmission power of the UE is taken as a uniform distribution in the 1-15W range. Battery level is taken in the range 0-100 %. Within the 0-100 % range, a display of 0 % signifies the presence of built-in reserves, allowing devices to retain minimal power for critical operations such as data preservation and shutdown notifications, which remain concealed from user visibility.

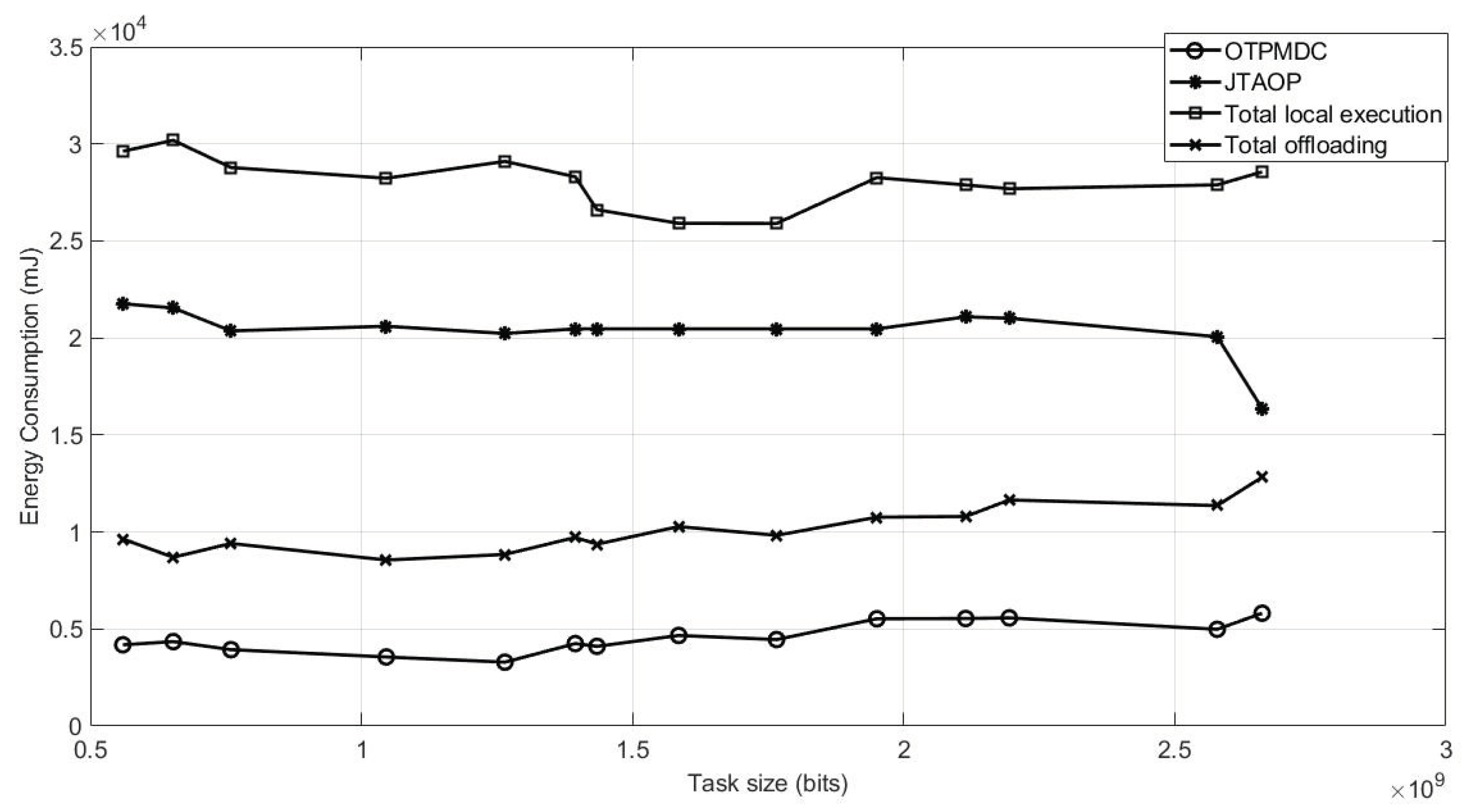

Figure 5 describes energy consumption by the UE using four different methods. Our proposed method, OTPMDC, shows the best results in terms of minimum energy consumption.

The validation of the dataset is determined by the proposed mathematical model because three datasets, namely, 1) the training dataset, 2) validation dataset, and 3) test dataset are generated. In each dataset, the input data contains the size of each unit, frequency of the user equipment for execution, transmit power of the UE, distance between UE and HAP for MEC, distance between UE and HAP for MDC, level of the battery of UE, and the minimum cost calculated by the mathematical model.

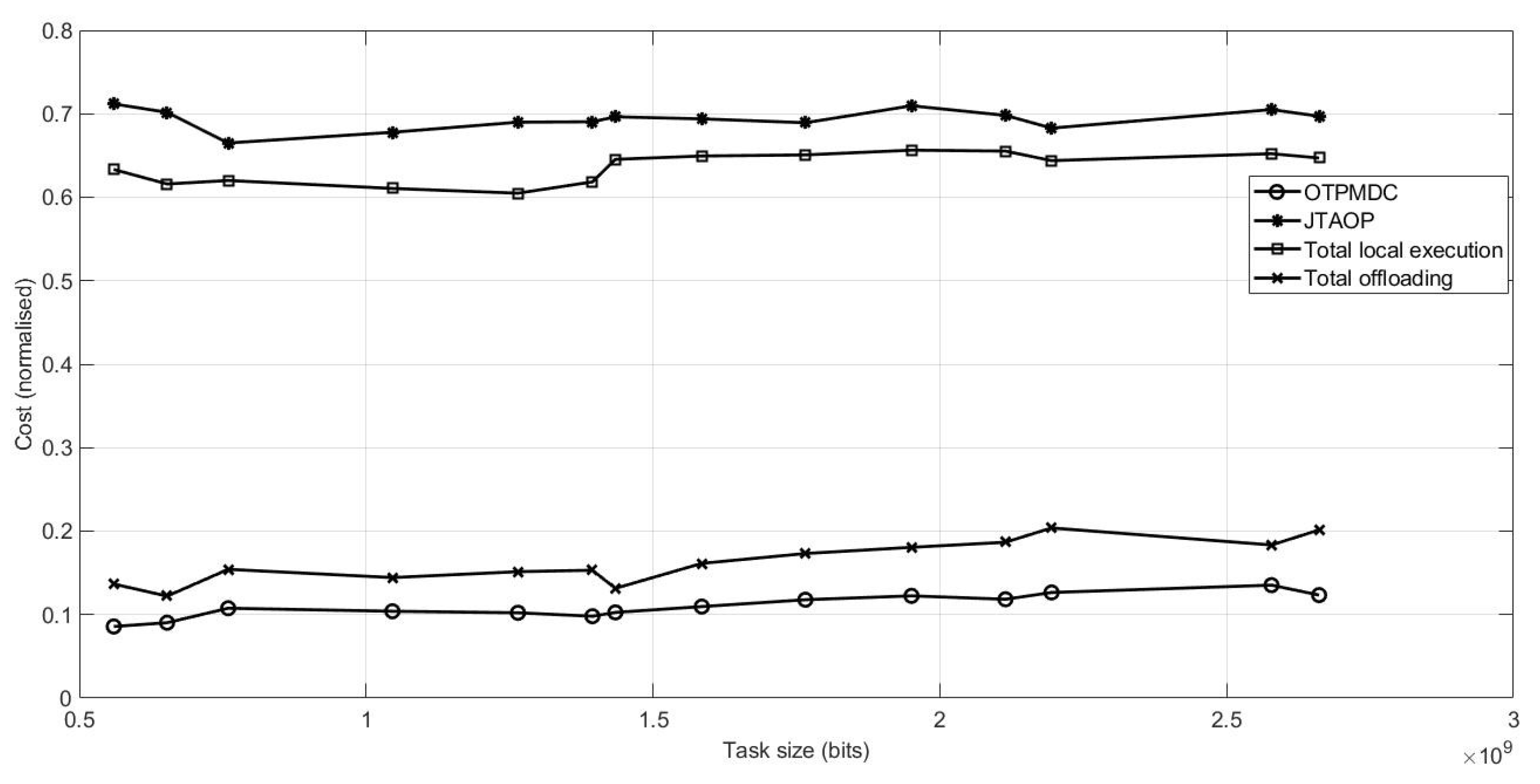

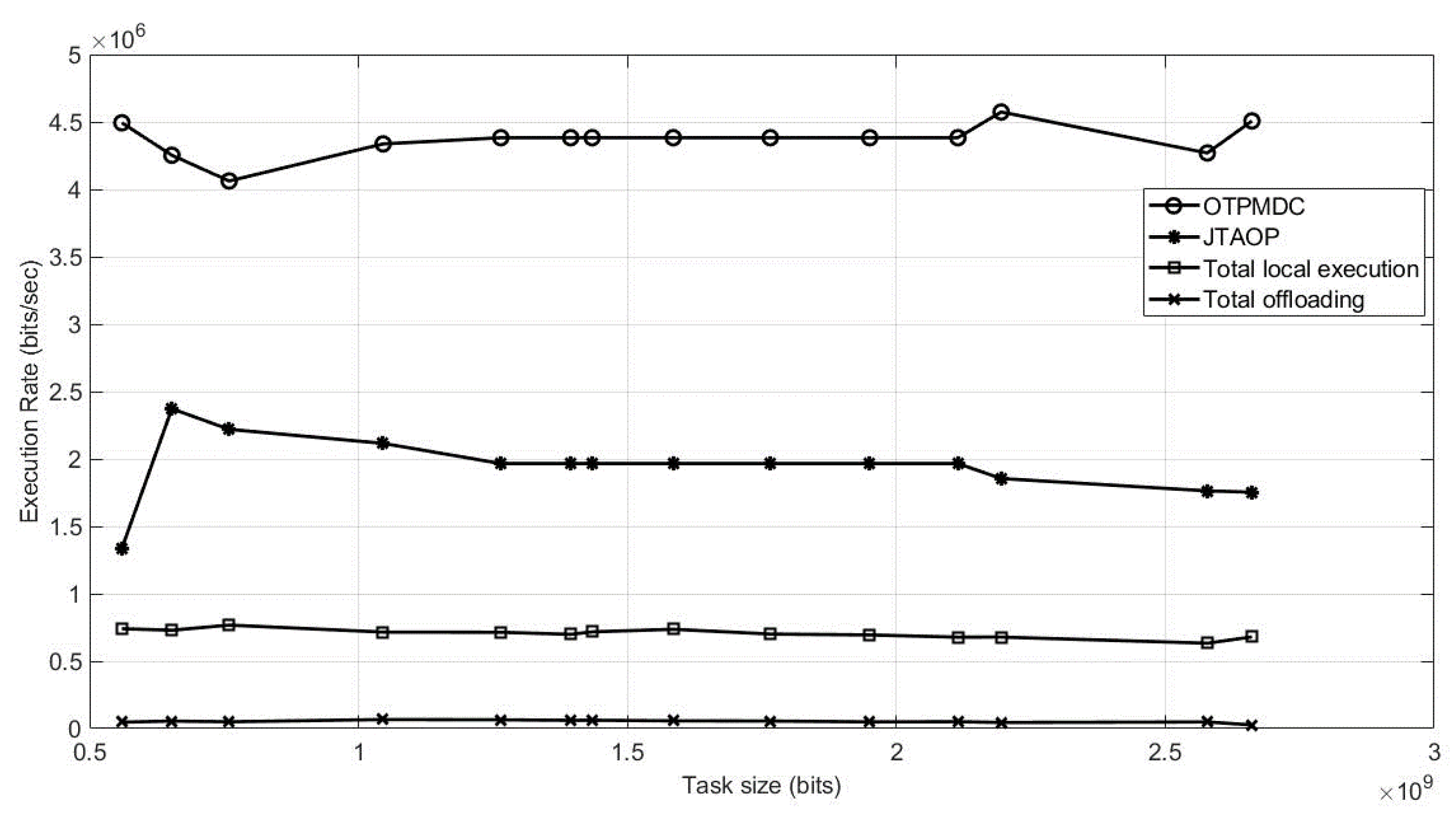

Figure 3 shows how the system executes local execution, MEC remote execution and MDC remote execution simultaneously with minimum cost. In the graph, we compare four methodologies that are JTAOP, total local execution, total offloading, and OTPMDC.

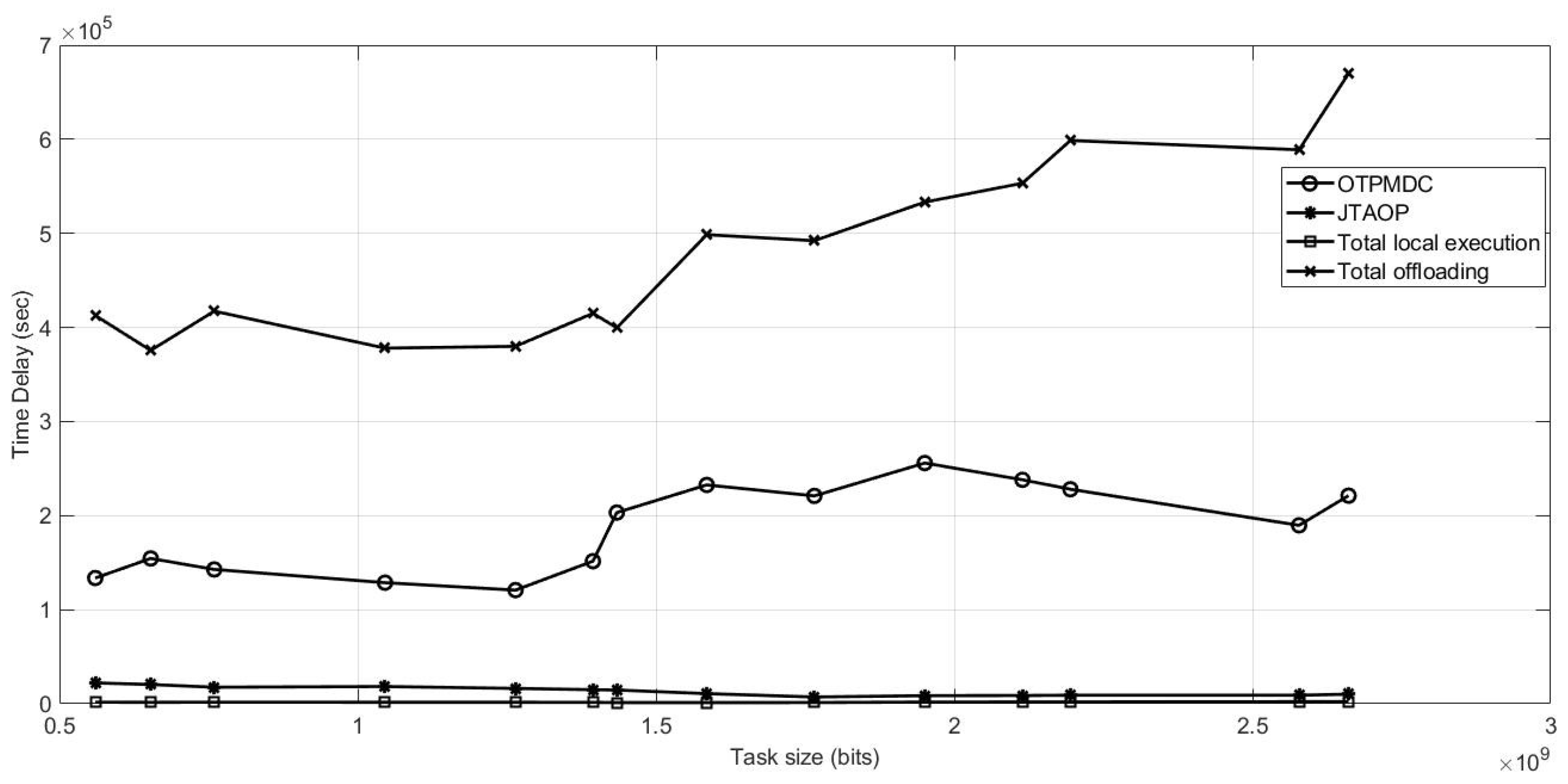

Figure 4 depicts time delay using four techniques for comparison. Despite the fact that the total local execution approach produces the most desirable outcomes, this technique gives inadequate consideration to computational power, memory, storage, or battery life, resulting in energy inefficiency. Similarly, although JTAOP has less time delay than OTPMDC, it is also energy inefficient as shown in

Figure 5. However, in our proposed technique, OTPMDC, we have taken into account factors like battery life and storage and also overall cost is best in our methodology as it is most energy efficient.

Figure 3.

Normalised Cost vs. Task Size.

Figure 3.

Normalised Cost vs. Task Size.

Figure 4.

Time Delay for Execution vs. Task Size.

Figure 4.

Time Delay for Execution vs. Task Size.

Figure 5.

Energy Consumption by UE vs. Task Size.

Figure 5.

Energy Consumption by UE vs. Task Size.

Figure 6 shows the four techniques being examined in this work in order to determine the optimal strategy, this time in terms of execution rate with OTPMDC has the best execution rate among all methodologies.

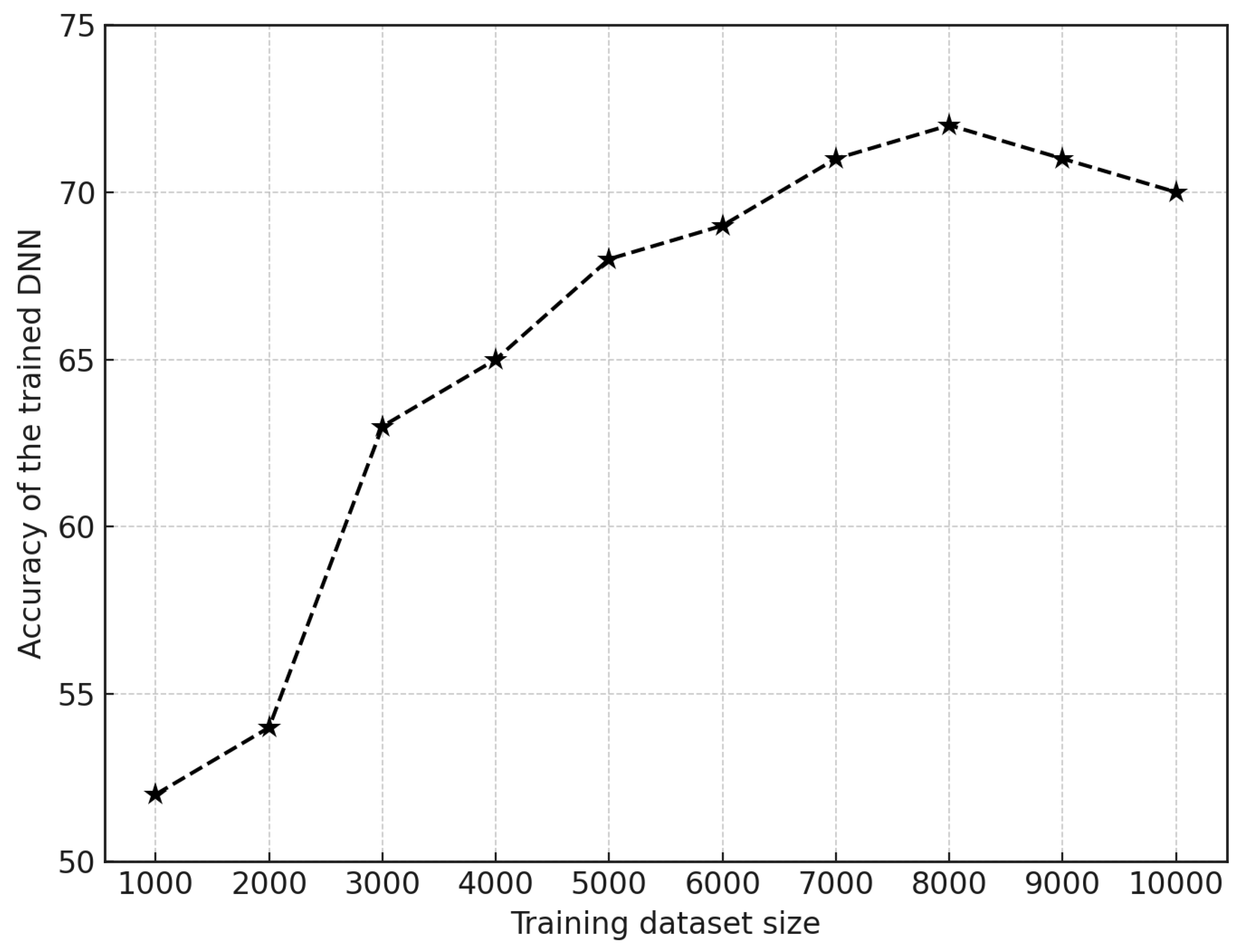

Initially, as the training dataset size increases from 1000 to 3000 samples, there is a notable from 52% to 63% improvement in accuracy. This significant increase indicates that the model has benefited greatly from the additional data during the early stages of training. As the dataset size continues to grow from 3000 to 6000 samples, the accuracy further improves but at a slower rate, reaching 69%. This step reflects a point of diminishing returns, where each additional data sample contributes relatively less proportionate to the overall accuracy improvement. Between 6000 and 8000 samples, the accuracy continues to increase slightly, reaching 72%. This shows that the model is still gaining from additional data stacks, although the gains are becoming narrowly marginal.

Finally, from 8000 to 10000 samples, the accuracy peaks to 72% and then slightly decreases bowing down to 70%. This slight drop suggests that beyond a certain point, adding more data items does not necessarily lead to proportionate better performance and might even cause the training to converge.

6. Conclusion

This paper has investigated the inclusion of crucial factors in a WP-MEC system such as the energy level of the battery of the UE. The proposed work is based a scalable algorithm in terms of resolution of time fraction and the number of components of a given task, and solved the issues related to the partial offloading scheme by considering a deep learning approach. Minimization of cost and energy consumption of the UE are studied by considering a UE and a double antenna-featured HAP both in MEC and MDC with the help of the trained DNN. The trade-off between energy consumption and time delay is also studied to find the optimal policy that gives the minimum cost, energy consumption and time delay, simultaneously. For future work, the paper has suggested a plan to consider user mobility along with health and emergency scenarios. Wearable devices such as blood glucose monitors, blood pressure monitors, and ECG sensors are crucial for real-time health monitoring and management, particularly in urgent situations. These devices are vital due to their roles in intensive data processing and sustained battery usage, making them indispensable in healthcare conditions demanding critical managing.

References

- Li, S.; Ma, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Xie, Y. Towards Enhanced Energy Aware Resource Optimization for Edge Devices Through Multi-cluster Communication Systems. Journal of Grid Computing 2024, 22, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaman, S.K.u.; Jehangiri, A.I.; Maqsood, T.; Ahmad, Z.; Umar, A.I.; Shuja, J.; Alanazi, E.; Alasmary, W. Mobility-aware computational offloading in mobile edge networks: a survey. Cluster Computing.

- Alhaddad, M.M. Unlocking the Potential of Mobile-Edge Cloud: A Comprehensive Review and Future Directions. Journal of Artificial Intelligence General science (JAIGS) ISSN: 3006-4023 2024, 4, 57–80. [Google Scholar]

- Kraemer, C.; Gelder, W.; Hester, J. User-directed Assembly Code Transformations Enabling Efficient Batteryless Arduino Applications. Proceedings of the ACM on Interactive, Mobile, Wearable and Ubiquitous Technologies 2024, 8, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hess, S.; Segarra, G.; Evensen, K.; Festag, A.; Weber, T.; Cadzow, S.; Arndt, M.; Wiles, A. Towards standards for sustainable ITS in Europe. In Proceedings of the 16th ITS World Congress and Exhibition, Stockholm, Sweden. Citeseer; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, Z.; Jiao, L.; Baker, T.; Abbas, G.; Abbas, Z.H.; Khaf, S. A deep learning approach for energy efficient computational offloading in mobile edge computing. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 149623–149633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Debroy, S. Resource management in mobile edge computing: a comprehensive survey. ACM Computing Surveys 2023, 55, 1–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, J.; Dai, L.; Tong, Z.; Deng, X.; Li, K. Throughput-aware dynamic task offloading under resource constant for MEC with energy harvesting devices. IEEE Transactions on Network and Service Management 2023, 20, 3460–3473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irshad, A.; Abbas, Z.H.; Ali, Z.; Abbas, G.; Baker, T.; Al-Jumeily, D. Wireless powered mobile edge computing systems: Simultaneous time allocation and offloading policies. Electronics 2021, 10, 965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Liu, J.; Xiong, Z.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, R.; Mao, S.; Han, Z. Cost-Effective Hybrid Computation Offloading in Satellite-Terrestrial Integrated Networks. IEEE Internet of Things Journal 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mapari, S.; Veeraiah, V.; Manchala, M.; Dhamodaran, S.; Anand, R.; Kaur, S. Challenges in Remote Big Data Transmission in Io’T Environment. In Proceedings of the 2024 2nd International Conference on Disruptive Technologies (ICDT). IEEE; 2024; pp. 1464–1468. [Google Scholar]

- Kong, G.; Hong, Y.G. Inference Latency Prediction Approaches Using Statistical Information for Object Detection in Edge Computing. Applied Sciences 2023, 13, 9222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qadir, J.; Sainz-De-Abajo, B.; Khan, A.; Garcia-Zapirain, B.; De La Torre-Diez, I.; Mahmood, H. Towards mobile edge computing: Taxonomy, challenges, applications and future realms. Ieee Access 2020, 8, 189129–189162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, S.; Chen, X.; Ni, W.; Wang, X.; Hossain, E. Modeling and analysis of energy harvesting and smart grid-powered wireless communication networks: A contemporary survey. IEEE Transactions on Green Communications and Networking 2020, 4, 461–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orsini, G.; Bade, D.; Lamersdorf, W. Cloudaware: A context-adaptive middleware for mobile edge and cloud computing applications. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE 1st International Workshops on Foundations and Applications of Self* Systems (FAS* W). IEEE; 2016; pp. 216–221. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, W.; Dustdar, S. The promise of edge computing. Computer 2016, 49, 78–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Song, M.; Zhang, L.; Chen, W.; Luo, Y. Offloading optimization and time allocation for multiuser wireless energy transfer based mobile edge computing system. Mobile Networks and Applications.

- Zhang, K.; Mao, Y.; Leng, S.; Zhao, Q.; Li, L.; Peng, X.; Pan, L.; Maharjan, S.; Zhang, Y. Energy-Efficient Offloading for Mobile Edge Computing in 5G Heterogeneous Networks. IEEE Access 2016, 4, 5896–5907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, S.; Leng, S.; Yang, K.; Huang, X.; Zhao, Q. Fair energy-efficient scheduling in wireless powered full-duplex mobile-edge computing systems. In Proceedings of the GLOBECOM 2017-2017 IEEE Global Communications Conference. IEEE; 2017; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Mao, S.; Leng, S.; Maharjan, S.; Zhang, Y. Energy efficiency and delay tradeoff for wireless powered mobile-edge computing systems with multi-access schemes. IEEE Transactions on Wireless Communications 2019, 19, 1855–1867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Jiao, L.; Li, W.; Fu, X. Efficient multi-user computation offloading for mobile-edge cloud computing. IEEE/ACM transactions on networking 2015, 24, 2795–2808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.; Wang, X.; Langar, R. Computation offloading for mobile edge computing: A deep learning approach. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE 28th Annual International Symposium on Personal, Indoor, 2017, and Mobile Radio Communications (PIMRC). IEEE; pp. 1–6.

- Lee, J.; Na, W. A survey on mobile edge computing architectures for deep learning models. In Proceedings of the 2022 13th International Conference on Information and Communication Technology Convergence (ICTC). IEEE; 2022; pp. 2346–2348. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, P.; Kwak, J. A Survey on mobile edge computing for deep learning. In Proceedings of the 2023 International Conference on Information Networking (ICOIN). IEEE; 2023; pp. 652–655. [Google Scholar]

- Worgan, P.; Knibbe, J.; Fraser, M.; Plasencia, D.M. Mobile energy sharing futures. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 18th International Conference on Human-Computer Interaction with Mobile Devices and Services Adjunct, New York, NY, USA, 2016. [CrossRef]

- Abusafia, A.; Lakhdari, A.; Bouguettaya, A. Service-Based Wireless Energy Crowdsourcing. In Proceedings of the Service-Oriented Computing; Troya, J.; Medjahed, B.; Piattini, M.; Yao, L.; Fernández, P.; Ruiz-Cortés, A., Eds., Cham; 2022; pp. 653–668. [Google Scholar]

- Lakhdari, A.; Bouguettaya, A.; Mistry, S.; Neiat, A.G. Composing Energy Services in a Crowdsourced IoT Environment. IEEE Transactions on Services Computing 2022, 15, 1280–1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schildt, S.; Büsching, F.; Jörns, E.; Wolf, L. Candis: Heterogenous mobile cloud framework and energy cost-aware scheduling. In Proceedings of the 2013 IEEE International Conference on Green Computing and Communications and IEEE Internet of Things and IEEE Cyber, Physical and Social Computing. IEEE; 2013; pp. 1986–1991. [Google Scholar]

- Sigwele, T.; Pillai, P.; Hu, Y.F. Saving energy in mobile devices using mobile device cloudlet in mobile edge computing for 5G. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Conference on Internet of Things (iThings) and IEEE Green Computing and Communications (GreenCom) and IEEE Cyber, Physical and Social Computing (CPSCom) and IEEE Smart Data (SmartData). IEEE; 2017; pp. 422–428. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).