1. Introduction

Sugarcane (

Saccharum spp.) is a critical cash crop for India, underpinning the country's significant sugar industry and contributing to the livelihoods of millions of farmers. The largest sugarcane-producing state of India is Uttar Pradesh, which has a 48.46% share in overall sugarcane production as per 2019-20 figure. Maharashtra and Karnataka are the second and third largest sugarcane-producing states, respectively. The other main sugarcane-producing states of India include Bihar, Haryana, Gujarat, Andhra Pradesh, and Tamil Nadu [

1,

22]. The crop suffers a number of difficulties, such as soil deterioration, pest pressures, and variable yields, despite its economic significance. Recent advancements of high-throughput sequencing (HTS) technologies, offer a novel approach to address these challenges by providing insights into the rhizospheric microbiome— the community of microorganisms residing in the soil surrounding plant roots [

2,

3]. The rhizosphere is a dynamic and nutrient-rich zone where plant roots interact closely with soil microorganisms. This zone is home to a complex and diverse array of microbes, including bacteria, fungi, and archaea, which play crucial roles in plant health and productivity. These microorganisms can enhance nutrient availability, promote plant growth, protect against soil-borne pathogens, and improve stress tolerance. The composition and functionality of the rhizospheric microbiome are thus integral to understanding plant performance and soil health [

4].

In sugarcane cultivation, the rhizosphere microbiome can significantly influence yield outcomes. High-yielding sugarcane is associated with more favorable microbial communities that enhance nutrient uptake, improve disease resistance, and support overall plant health [

5]. Conversely, low-yielding sugarcane may be linked to less optimal rhizosphere conditions, negatively impact the growth and productivity. Therefore, analyzing and comparing the rhizospheric microbiome of high-yielding and low-yielding sugarcane varieties could provide valuable insights into the microbial factors that underpin yield differences [

2,

6].

Traditional methods for studying soil microbiomes, such as culturing techniques and microscopy, are limited in their ability to capture the full diversity and complexity of microbial communities. These methods often fail to identify many soil microorganisms, which are either non-culturable or present in very low abundances [

7]. High-throughput sequencing (HTS) technologies have revolutionized microbial ecology by allowing researchers to analyze the entire microbial community without culturing. Techniques such as 16S ribosomal RNA (rRNA) gene sequencing and metagenomic sequencing provide detailed microbial diversity profiles and functional potential [

8,

18].

16S rRNA gene sequencing focuses on the bacterial component of the microbiome, offering insights into bacterial diversity, community composition, and abundance. This method relies on amplifying and sequencing a specific region of the 16S rRNA gene, which is conserved across bacterial species but contains variable regions that are unique to different taxa [

9]. Metagenomic sequencing, on the other hand, involves sequencing all the DNA present in a sample, providing a broader perspective that includes not only bacterial but also fungal, archaeal, and viral communities. This approach enables the exploration of functional potentials, such as metabolic pathways and interactions with the host plant [

10,

20].

Recent studies utilizing HTS technologies have revealed significant differences in microbial communities associated with various plant species, including crops. For example, research by Finkel et al. (2020) demonstrated that HTS can identify microbial biomarkers that are associated with plant growth and stress responses [

11]. Similarly, studies on other crops, such as maize and wheat, have shown that high-yielding varieties often have distinct microbial communities compared to low-yielding ones, suggesting a role for the microbiome in crop performance [

12].

The role of soil microbiomes in agriculture has been well-documented in recent literature. For instance, Finkel et al. (2020) highlighted the importance of soil microbiomes in crop productivity, noting that microbial communities can influence nutrient availability and plant health [

11]. In the context of sugarcane, the high-yielding exhibit higher microbial diversity and beneficial microbial interactions compared to low-yielding varieties. Furthermore, Chauhan et al. (2023) emphasized the utility of HTS technologies in uncovering microbial features associated with improved crop performance [

13].

Despite these advances, specific studies on sugarcane in Uttar Pradesh using HTS are limited. This research seeks to fill this gap by providing a detailed comparative analysis of rhizosphere microbiomes in Shamli (high-yielding) and Hapur (low-yielding) sugarcane, using High-throughput sequencing.

This research aims to advance our understanding of the rhizosphere microbiome in sugarcane by conducting a comparative analysis of high-yielding and low-yielding sugarcane microbiomes using high-throughput sequencing. By elucidating the microbial differences and their functional implications, this study will contribute to develop the strategies for improving sugarcane production and promoting sustainable agricultural practices in Uttar Pradesh.

2. Materials and Methods

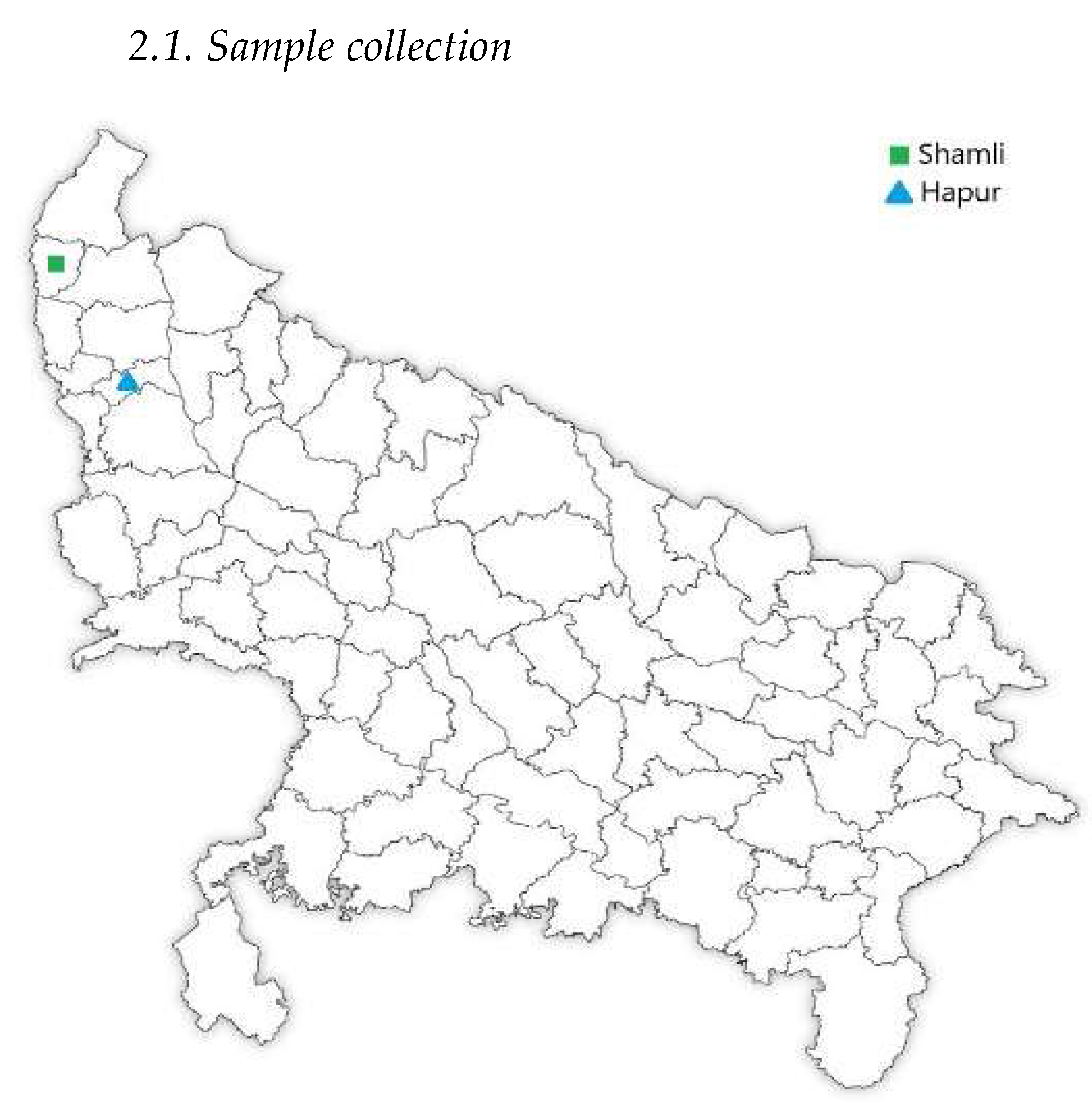

2.1. Sample collection

A total of 50 rhizosphere soil samples from sugarcane plants were collected and analyzed. These samples were gathered from two districts in Uttar Pradesh— Shamli (high-yielding) and Hapur (low-yielding) (

Figure 1) —each from five distinct sites with five replicates per site. The sampling locations in Hapur were at the following coordinates: N 28°45'13", E 77°54'02"; N 28°45'10", E 77°51'10"; N 28°47'31", E 77°49'09"; N 28°44'56", E 77°50'52"; N 28°44'56", E 77°50'54". In Shamli, the sample locations were: N 29°29'50", E 77°26'27"; N 29°30'03", E 77°26'57"; N 29°30'33", E 77°26'57"; N 29°30'33", E 77°27'12"; N 29°29'60", E 77°26'58". The samples were collected in May 2023 during the elongation stage of sugarcane. The five blocks sampling method was used, and five fields were selected from each sample block. The soil around the roots were collected along with roots using shovel. They were placed in sterile polybags, transported in ice boxes, and stored at -80°C until further analysis [

14].

2.2. Genomic DNA extraction and sequencing

A culture-independent method was employed to examine the bacterial composition of the rhizosphere microbiome. Microbial DNA was extracted from the rhizosphere soil samples using the Quick-DNA Fecal/Soil Microbe DNA Miniprep Kit (ZYMO, USA), following the manufacturer's guidelines. The purity and concentration of the extracted DNA were evaluated using 1% agarose gel electrophoresis. DNA samples were then diluted to a concentration of 1 ng/μL using sterile water for further analysis. To generate six composite sample, DNA extracts from each sugarcane rhizosphere sample were combined in equal amounts (

Table S1). These composite samples were subsequently used for sequencing. The sequencing process was carried out using 16S rRNA amplicon, paired-end Illumina Nextera DNA sequencing was conducted at Centyle Biotech Pvt. Ltd., New Delhi [

15].

2.3. Bioinformatics Data analysis

The obtained sequences were processed and analyzed using the QIIME2 pipeline (v2024.5) (

https://qiime2.org/). Initially, the raw FASTQ files were imported into QIIME2. The paired-end sequences were subsequently trimmed at the first 20 bases and truncated to a length of 200 bases. These sequences underwent quality filtering, denoising, and merging with DADA2 via the q2-dada2 plugin in QIIME2. The representative sequences were aligned using the MAFFT program. Alpha and Beta diversity analyses were conducted using the core-metrics-phylogenetic pipeline within the q2-diversity plugin of QIIME2. This process involved rarefying ASV tables to 50,000 reads and calculating alpha diversity metrics, including Shannon’s diversity index, observed ASVs, Faith’s phylogenetic diversity, and evenness. It also calculates Jaccard, Bray–Curtis, and both weighted and unweighted UniFrac distances to assess beta diversity, while generating PCoA plots for each of these beta diversity metrics. The relationship between categorical metadata groups and alpha diversity metrics was assessed using the Kruskal–Wallis test, with results corrected via the Benjamini–Hochberg method. For beta diversity, PERMANOVA was used for analysis, followed by correction with the Benjamini–Hochberg method, all performed using the R software packages "stats" and "vegan" [

16].

3. Results

3.1.16. S rRNA sequencing and bacterial classification

High-throughput sequencing of the bacterial 16S rRNA gene generated a total of 659,435 paired-end reads. After screening and trimming, 601,072 high-quality sequences remained, each with an average length of approximately 270 base pairs (

Table 1).

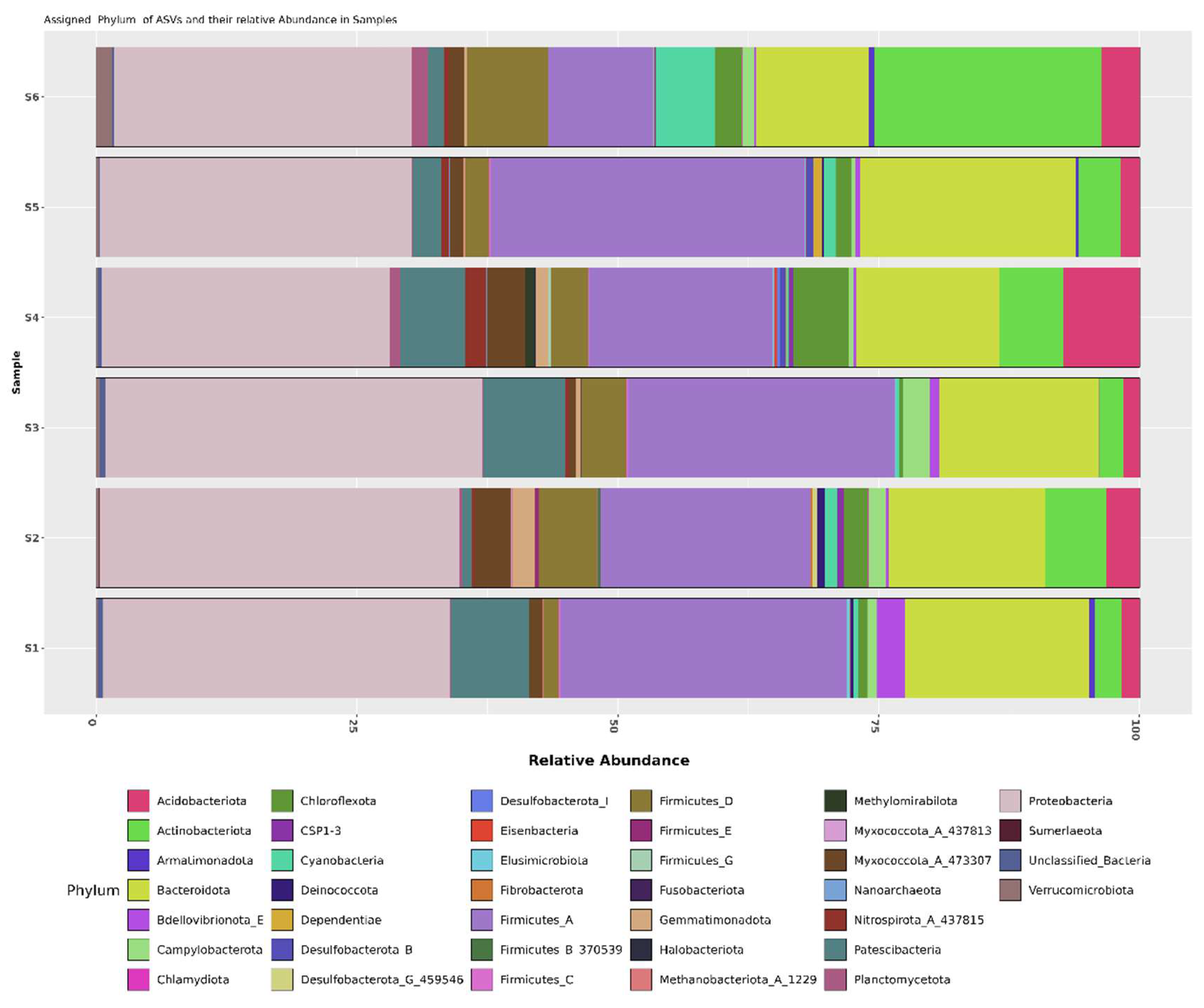

3.2. Bacterial community composition

The abundance of bacterial communities in the rhizosphere soil was analyzed across all taxonomic levels. The findings were displayed using taxonomic bar plots. The taxonomic composition of the Sugarcane rhizosphere microbiome was mainly dominated by

Proteobacteria, accounting together for the 31.64% , followed by

Firmicutes_

A (21.82% ),

Bacteroidetes(15.51%),

Actinobacteriota (7.08%),

Patescibacteria (4.47%),

Firmicutes_

D (4.14%),

Acidobacteriota (3.22%),

Chloroflexota(2.16%),

Myxococcota_

A_473307 (1.94%),

Cyanobacteria (1.50%) and other phyla accounting for less than 1% (

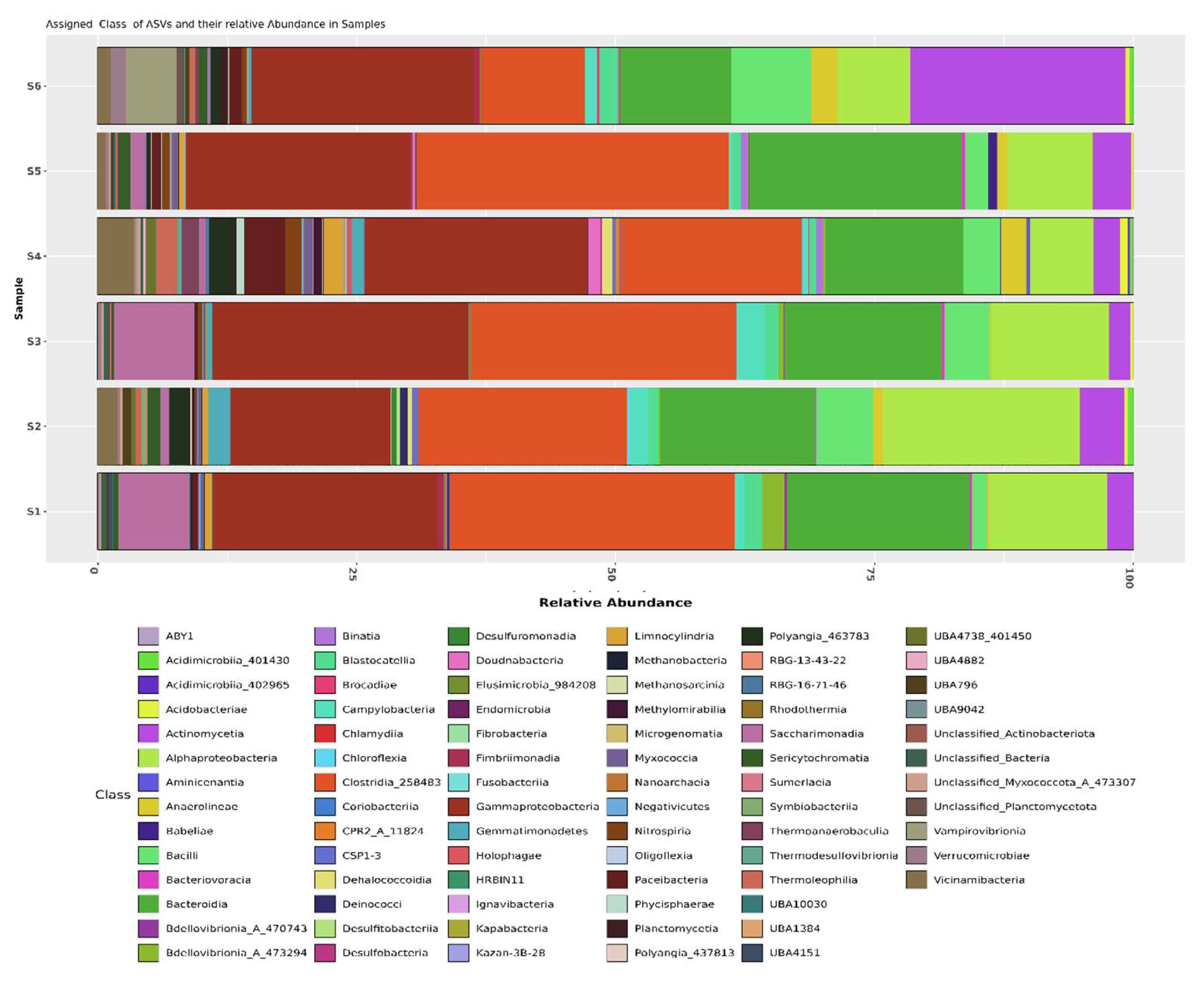

Figure 2(a)). In Shamli, the class level showed higher abundance of bacteria

Clostridia_258483 (24.39%),

Gammaproteobacteria (20.67%),

Bacteroidia (15.90%),

Alphaproteobacteria (13.93%),

Saccharimonadia (5.18%),

Bacilli (3.76%),

Actinomycetia (2.96%),

Campylobacteria (1.72%),

Blastocatellia (1.35%), and other and In Hapur, the class level showed higher abundance of bacteria

Gammaproteobacteria (21.52%),

Clostridia_258483 (19.25%),

Bacteroidia (14.86%),

Actinomycetia (9.02%),

Alphaproteobacteria (7.16%),

Bacilli (4.53%),

Paceibacteria (2.07%),

Anaerolineae (1.96%),

Vicinamibacteria (1.82%),

Vampirovibrionia (1.82%), (

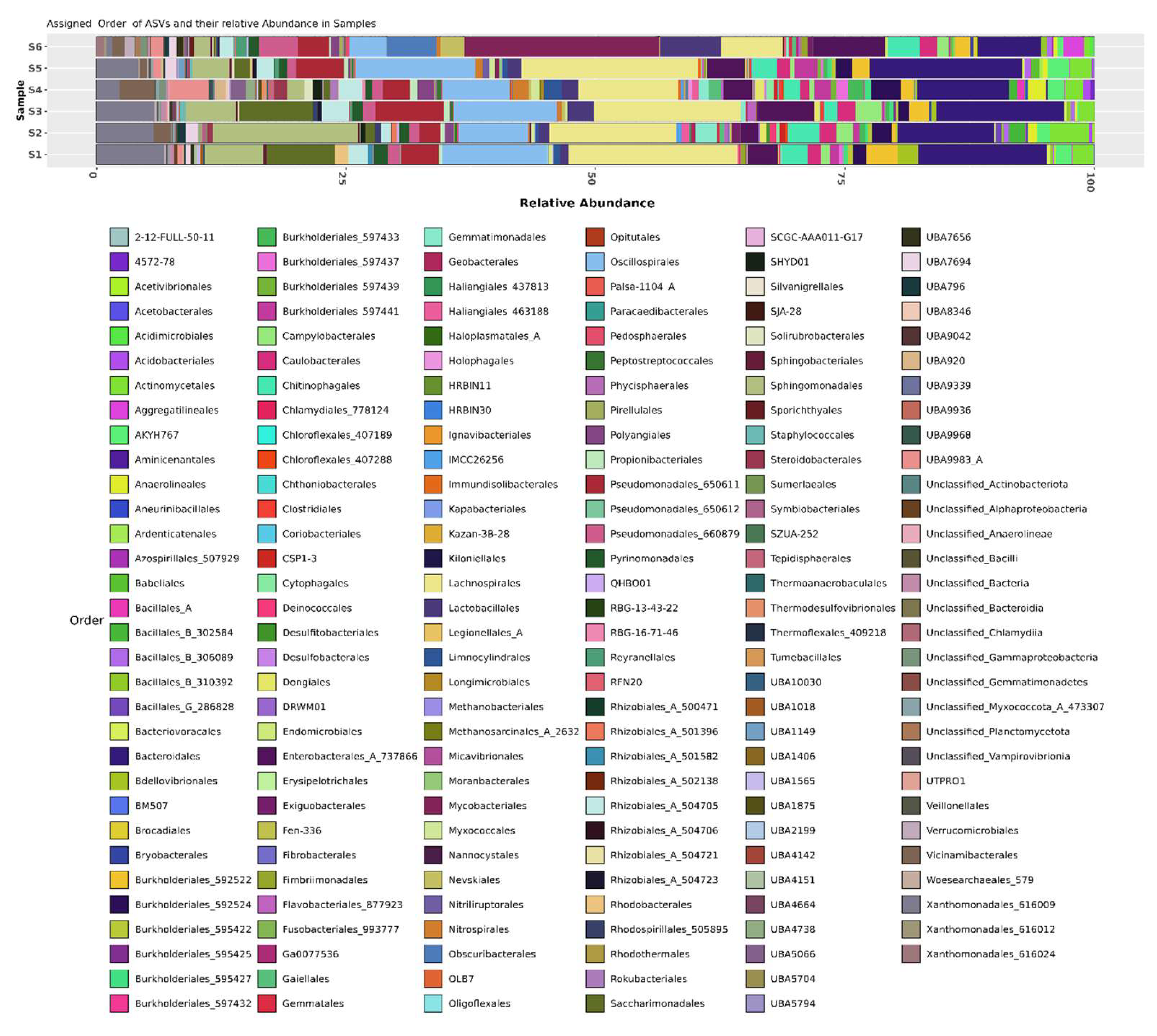

Figure 2(b)). In Shamli, the highest relative abundance at order level shown

Lachnospirales (14.77%),

Bacteroidales (11.80%),

Oscillospirales (9.26%),

Sphingomonadales (8.47%),

Xanthomonadales_616009 (6.09%),

Saccharimonadales (5.05%),

Pseudomonadales_650611 (4.25%),

Enterobacterales_A_737866 (3.5%),

Actinomycetales (2.51%),

Chitinophagales (2.25%),

Rhizobiales_A_504705 (1.89%),

Burkholderiales_

592522 (1.82%),

Campylobacterales (1.72%),

Caulobacterales (1.61%),

Lactobacillales (1.53%),

Burkholderiales_592524 (1.47%),

Pyrinomonadales (1.17%), and other order accounting for less than 1%. In Hapur, the highest relative abundance at order level shown

Lachnospirales (11.32 %),

Bacteroidales (10.27 %),

Oscillospirales (7.48%),

Mycobacteriales (6.65%),

Enterobacterales_A_737866 (4.62%),

Pseudomonadales_650611 (3.53%),

Lactobacillales (3.04%),

Chitinophagales (2.41%),

Xanthomonadales_616009 (2.37%),

Sphingomonadales (2.37%),

UBA9983_A (1.97%),

Pseudomonadales_660879 (1.96%),

Rhizobiales_

A_504705 (1.84%),

Vicinamibacterales (1.84%),

Obscuribacterales (1.82%),

Actinomycetales (1.66%), and other order accounting for less than 1%. (Figure. 2(c))

3.3. Diversity dynamics of rhizosphere bacterial communities

The diversity of each growth phase sample was assessed through alpha diversity, which provides an estimate of the species richness, abundance, and distribution within the microbial community of the rhizosphere. Alpha diversity was quantified using the Shannon and Simpson indices. Shannon diversity ranged from 4.54 to 5.21, with an average of 4.90, while the Simpson index varied between 0.97 and 0.99, showing only minor variations across the locations. Notably, samples from Shamli exhibited higher diversity compared to those from Hapur, which had the lowest diversity (

Table 2).

Sample 02 recorded the highest Shannon index (5.20), indicating greater species abundance and evenness, followed by sample 01 (4.96), sample 04 (5.14), sample 05 (4.88), sample 03 (4.70), and sample 06 (4.54). The Simpson index, which reflects species richness and evenness, was also highest in sample 02 and lowest in sample 06, with relatively little variation between the other samples (

Figure 3(a), (b)).

Beta diversity, which measures the variation in species composition across different samples or environments, was evaluated through Principal Coordinate Analysis (PCoA) of the 16S rRNA gene in the sugarcane rhizosphere soil. Our analysis revealed significant differences in the microbiota composition of the rhizosphere soil across the samples. Unconstrained PCoA, based on Bray–Curtis distances, showed that the microbiota from each sample formed distinct clusters, clearly separated along the coordinate axes. Principal coordinate axes 1 (Coordinate 1) and 2 (Coordinate 2) explained 24.5% and 21.4% of the variation, respectively, highlighting the influence of environmental factors on the microbial community structure across the different samples (

Figure 4). This analysis underscores the spatial variation in rhizosphere microbiota diversity across sampling locations.

We found that the composition of the rhizosphere soil microbiota differed with respect to fertilizer regime. Unconstrained principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) Of bray-Curtis Distances revealed that the rhizosphere microbiota of both Hapur and Shamli formed two distinct cluster.

3.4. Differentiated Rhizosphere bacterial communities in high yield and low yield sugarcane

LEfSe analysis revealed taxonomic differences among the two bacterial groups. The predominant bacterial taxa in the preceding sugarcane rhizosphere (PSR) encompassed and bacterial components with significant differences among groups were explored (Figure.5). The results demonstrated difference between the Shamli and Hapur groups in terms of bacterial abundance in rhizosphere soil microbiome.

In total, 64 bacterial taxa were found to be differentially abundant in both high and low yield. Of these, 42 taxa had significant in abundance, considering a p-value≤0.01 in low yielding sugarcane. Among them, are the phylum

Nitrospirota and

Desulfobacterota, the seven class and the six order were differentially abundant in low yielding sugarcane. In the high yielding sugarcane, 22 taxa were differentially abundant in relation to the low yielding, considering a p-value≤0.01. among these, four families are,

Sphingomonadaceae,

Xanthomonadaceae,

Aeromonadaceae and

UAE5946 (

Saccharimonadales). The seven genera identified were most abundant in the high yielding sugarcane rhizosphere (

Figure 6). Moreover, at the genus level, the abundance distribution of the top genera with greatest significant difference were analyzed (

Figure 7).

4. Discussion

The primary aim of this study was to conduct a comparative analysis of microbial communities in the rhizosphere of high-yield and low-yield sugarcane, with the goal of understanding their ecological dynamics in terms of composition and diversity. Soil microorganisms that interact with host plants are known to stimulate the production of rich and different repertoire of metabolites in plants [

28]. We expected difference between the sample analyzed, in high yield and low yield sugarcane rhizosphere associated in change in structure and taxonomic composition of plant microbiome. Alawiye et al. shoed that there was no significant difference (p > 0.05) between the microbial diversity of the two locations [

27]. The Alpha diversity index results showed that microbial richness and microbial diversity [

32]. Our outcome showed, the alpha diversity indices did not show significant difference between Shamli (high-yielding) and Hapur (low-yielding) (considering a p-value≤0.1). However, Shannon and Simpson index show slightly high diversity in Shamli (

Figure 3(a), (b)). Pang et al. showed that the structure of the bacterial community was affected after continuous cropping of sugarcane and indicated that the bacterial community structures in the CC (Continuous Cropping) soil samples were distinctly different from the NCC (No Continuous Cropping) soil samples [

25,

30]. For the beta diversity indices, Principal coordinates analysis (PCoA) showed that there is significant compositional difference (considering a p-value≤0.1) when evaluating the location (Shamli and Hapur).

As seen in a previous research by De souza et al., core microorganisms in sugarcane rhizosphere, regardless of yielding, can bring benefits and plant vitality [

17]. In our study, we identified members of the sugarcane rhizosphere microbiome predominantly populated by bacteria, with a notable presence of phyla

Proteobacteria,

Bacteroidota,

Actinobacteriota,

Patescibacteria,

Firmicutes_D,

Acidobacteriota,

Chloroflexota,

Myxococcota,

Cyanobacteria,

Campylobacterota. The most abundant genra

Phocaeicola,

Lachnospira,

Faecalibacterium,

Pseudomonas,

Agathobacter,

Mycobacterium,

Limisoma,

Sphingomicrobium,

Thermomonas,

Enterobacteriaceae,

Serratia,

Lysobacter. The same was observed for phyla

Proteobacteria,

Actinobacteria,

Bacteroidetes,

Gemmatimonadetes,

Firmicutes, and

Acidobacteria were reported in canola, wheat, field pea and lentil rhizosphere. According to Yuan et al. Bacteria phyla relative abundance showed that

Proteobacteria (24.85–29.28%),

Actinobacteria (15.53–19.09%),

Chloroflexi (7.63–18.89%),

Acidobacteria (6.53–11.05%),

Firmicutes (5.59–37.36%) were the dominant bacteria, followed

Bacteroidetes (1.51–2.69%),

Gemmatimonadetes (1.50–6.95%),

Planctomycetes (0.99–2.60%) and

Saccharibacteria (0.65–3.01%) [

19]. Other previous studies showed abundance of the microbial community of phyla

Proteobacteria (16.68%),

Chloroflexi (26.73%),

Gemmatimonadetes (29.26%) and

Actinobacteria (35.68%) in rhizosphere of plant crop [

26]. LEfSe analysis, showed that

Gammaproteobacteria,

Alphaproteobacteria,

Burkholderiaceae,

Rhizobials, and

Burkholderia were all significantly enriched in the root compartment, while

Actinobacteria,

Intrasporangiaceae,

Firmicutes, and

Bacillus were enriched biomarkers in the rhizosphere compartment [

29,

34].

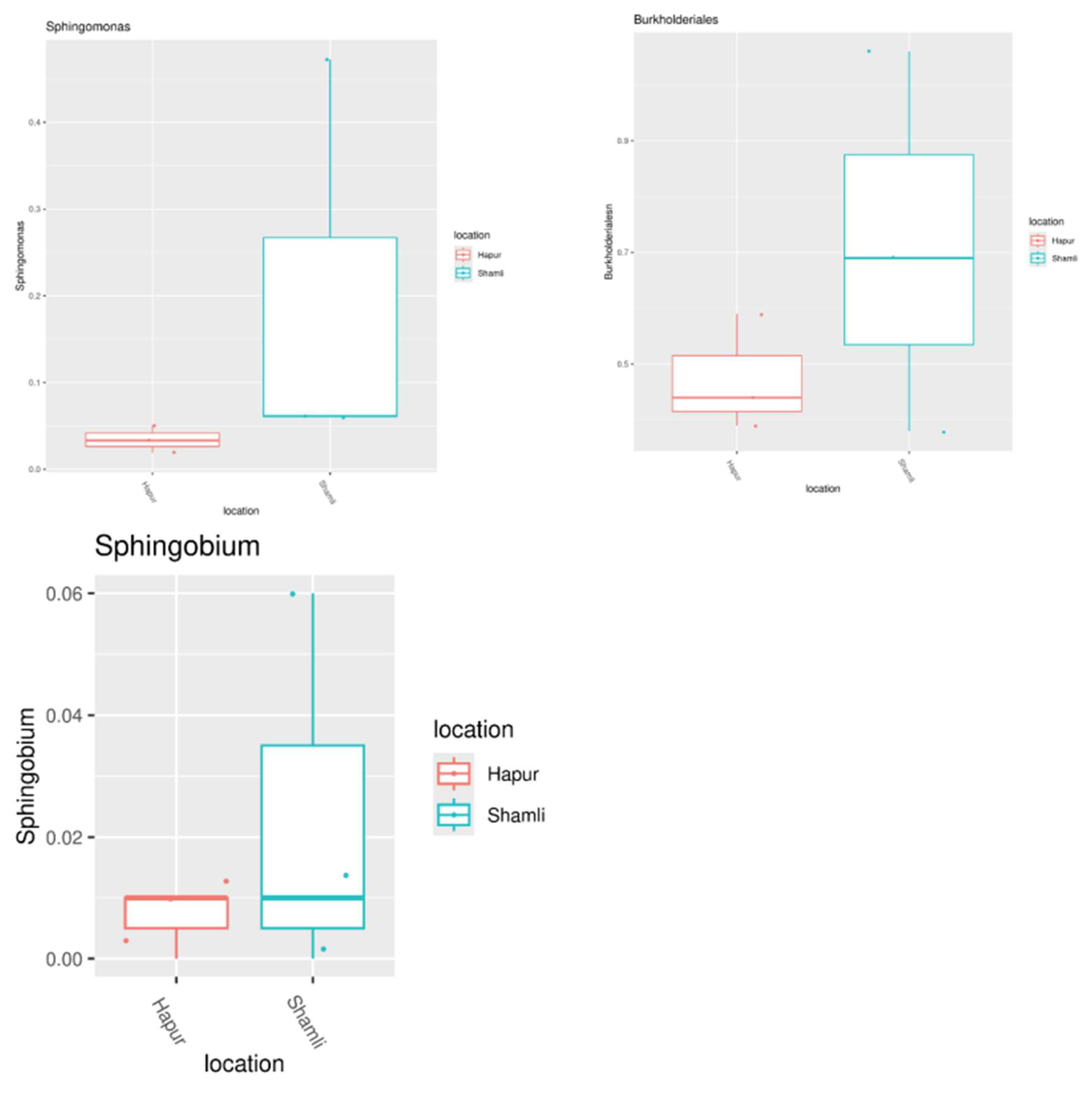

Rhizosphere microbial diversity play a key role in the promotion of plant growth and health. Our findings indicated that

Burkholderia,

Sphingomonas, and

Sphingobium were the predominant genera within the bacterial community of the sugarcane rhizosphere (

Figure 7). Previous studies have demonstrated that the

Burkholderia group possesses a broad host range and is recognized as one of the most effective plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria. These bacteria are found in both bulk soil and the rhizosphere and have been documented to colonize over 30 plant species [

23,

31,

33].

Sphingomonas exhibits a strong capacity to break down environmental pollutants and enhances plant uptake of nutrients, thereby supporting plant growth. It has also been shown that

Sphingomonas is the primary antimicrobial agent in soil communities and that this group has an inhibitory effect on plant pathogenic fungi [

21]. Various

Sphingobium species promote the synthesis of phytohormones, including salicylic acid (SA), indole-3-acetic acid (IAA), and zeatin abscisic acid (ABA), as well as other critical biosynthetic pathways in host plants, highlighting the genus's potential as plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR) [

24].

5. Conclusions

The study revealed the presence of numerous uncultured and unidentified core bacterial genera in the sugarcane rhizosphere, many of which likely interacted with the host plant and other microorganisms. Furthermore, several core genera known to promote plant growth were identified within the sugarcane rhizosphere. we could identify slight variations in the rhizosphere microbiome of high yield and low yield sugarcane field. we analyzed the rhizosphere microbial community using 16sRNA-based high-throughput sequencing. There were differences in the dominant rhizosphere bacterial taxonomic composition among the different sugarcane fields. The richness of the rhizosphere bacterial communities and the abundance of microbes, such as Proteobacteria, Firmicutes_A, Bacteroidetes, Actinobacteriota, Patescibacteria, Firmicutes_D, Acidobacteriota, Chloroflexota, Myxococcota_A, and Cyanobacteria. Thus, these findings could provide a way for promoting sugarcane health and growth by improving soil bacterial communities.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org. Table S1

Author Contributions

For research articles with several authors, a short paragraph specifying their individual contributions must be provided. The following statements should be used “Conceptualization, H.K. and P.K.; methodology, H.K. and P.K.; validation, H.K. and P.K.; formal analysis, H.K.; investigation, H.K. and M.R.P.; data curation, H.K.; writing—original draft preparation, H.K. and A.P.; writing—review and editing, P.K., M.K.B., S.P. R.D. K.K. and S.K.; visualization, H.K.; supervision, P.K. and M.R.P.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.”

Funding

“This research received no external funding”.

Data Availability

The sequencing reads were deposited in the Sequence Reads Archive database of the National Center for Biotechnology with the BioProject Accession No.: PRJNA1147258 (Accession: SRX25674071- SRX25674076).

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| HTS |

High-throughput sequencing |

| rRNA |

ribosomal RNA |

| QIIME |

Quantitative Insights Into Microbial Ecology |

| MAFFT |

Multiple Alignment using Fast Fourier Transform |

| PCoA |

Principal Coordinates Analysis |

| PERMANOVA |

Permutational multivariate analysis of variance |

| LEfSe |

Linear discriminant analysis Effect Size |

References

- Shukla, S. K., Sharma, L., Awasthi, S. K., & Pathak, A. D. (2017), Sugarcane in India: Package of Practices for Different Agro-climatic Zones. ICAR (Vol. 1, pp. 7).

- Malviya, M. K., Solanki, M. K., Li, C. N., Wang, Z., Zeng, Y., Verma, K. K., Singh, R. K., Singh, P., Huang, H. R., Yang, L. T., Song, X. P., & Li, Y. R. (2021). Sugarcane-Legume Intercropping Can Enrich the Soil Microbiome and Plant Growth. Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems, 5. [CrossRef]

- Li, X., Liu, Y., Wang, Z., Yang, C., Zhang, R., Luo, Y., Ma, Y., & Deng, Y. (2022). Microbiome analysis and biocontrol bacteria isolation from rhizosphere soils associated with different sugarcane root rot severity. Frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotechnology, 10. [CrossRef]

- Thepbandit, W., & Athinuwat, D. (2024). Rhizosphere Microorganisms Supply Availability of Soil Nutrients and Induce Plant Defense. In Microorganisms. Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute (MDPI). (Vol. 12, Issue 3). [CrossRef]

- Yao, Z., Khan, A., Xu, Y., Pan, K., & Zhang, M. (2024). Profiling of rhizosphere bacterial community associated with sugarcane and banana rotation system. Chemical and Biological Technologies in Agriculture, 11(1). [CrossRef]

- Pang, Z., Dong, F., Liu, Q., Lin, W., Hu, C., & Yuan, Z. (2021). Soil Metagenomics Reveals Effects of Continuous Sugarcane Cropping on the Structure and Functional Pathway of Rhizospheric Microbial Community. Frontiers in Microbiology, 12. [CrossRef]

- DeFord, L., & Yoon, J. Y. (2024). Soil microbiome characterization and its future directions with biosensing. In Journal of Biological Engineering (Vol. 18, Issue 1). BioMed Central Ltd. [CrossRef]

- Wang, H., Wang, Y., Yang, L., Feng, J., Tian, S., Chen, L., Huang, W., Liu, J., & Wang, X. (2024). Integrated 16S rRNA sequencing and metagenomics insights into microbial dysbiosis and distinct virulence factors in inflammatory bowel disease. Frontiers in Microbiology, 15. [CrossRef]

- Beaudry, M. S., Wang, J., Kieran, T. J., Thomas, J., Bayona-Vásquez, N. J., Gao, B., Devault, A., Brunelle, B., Lu, K., Wang, J. S., Rhodes, O. E., & Glenn, T. C. (2021). Improved Microbial Community Characterization of 16S rRNA via Metagenome Hybridization Capture Enrichment. Frontiers in Microbiology, 12. [CrossRef]

- Gökdemir, F. Ş., İşeri, Ö. D., Sharma, A., Achar, P. N., & Eyidoğan, F. (2022). Metagenomics Next Generation Sequencing (mNGS): An Exciting Tool for Early and Accurate Diagnostic of Fungal Pathogens in Plants. In Journal of Fungi (Vol. 8, Issue 11). MDPI. [CrossRef]

- Finkel, O. M., Salas-González, I., Castrillo, G., Conway, J. M., Law, T. F., Teixeira, P. J. P. L., Wilson, E. D., Fitzpatrick, C. R., Jones, C. D., & Dangl, J. L. (2020). A single bacterial genus maintains root growth in a complex microbiome. Nature, 587(7832), 103–108. [CrossRef]

- Kumaishi, K., Usui, E., Suzuki, K., Kobori, S., Sato, T., Toda, Y., Takanashi, H., Shinozaki, S., Noda, M., Takakura, A., Matsumoto, K., Yamasaki, Y., Tsujimoto, H., Iwata, H., & Ichihashi, Y. (2022). High throughput method of 16S rRNA gene sequencing library preparation for plant root microbial community profiling. Scientific Reports, 12(1). [CrossRef]

- Chauhan, P., Sharma, N., Tapwal, A., Kumar, A., Verma, G. S., Meena, M., Seth, C. S., & Swapnil, P. (2023). Soil Microbiome: Diversity, Benefits, and Interactions with Plants. In Sustainability (Switzerland) (Vol. 15, Issue 19). Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute (MDPI). [CrossRef]

- Malviya, M. K., Li, C. N., Lakshmanan, P., Solanki, M. K., Wang, Z., Solanki, A. C., Nong, Q., Verma, K. K., Singh, R. K., Singh, P., Sharma, A., Guo, D. J., Dessoky, E. S., Song, X. P., & Li, Y. R. (2022). High-Throughput Sequencing-Based Analysis of Rhizosphere and Diazotrophic Bacterial Diversity Among Wild Progenitor and Closely Related Species of Sugarcane (Saccharum spp. Inter-Specific Hybrids). Frontiers in Plant Science, 13. [CrossRef]

- Bez, C., Esposito, A., Musonerimana, S., Nguyen, T. H., Navarro-Escalante, L., Tesfaye, K., Turello, L., Navarini, L., Piazza, S., & Venturi, V. (2023). Comparative study of the rhizosphere microbiome of Coffea arabica grown in different countries reveals a small set of prevalent and keystone taxa. Rhizosphere, 25. [CrossRef]

- Yamazaki, S., Mardani-korrani, H., Kaida, R., Ochiai, K., Kobayashi, M., Nagano, A. J., Fujii, Y., Sugiyama, A., & Aoki, Y. (2021). Field multi-omics analysis reveals a close association between bacterial communities and mineral properties in the soybean rhizosphere. Scientific Reports, 11(1). [CrossRef]

- De Sousa, L. P., Guerreiro-Filho, O., & Mondego, J. M. C. (2022). The Rhizosphere Microbiomes of Five Species of Coffee Trees. Microbiology Spectrum, 10(2). [CrossRef]

- Khoiri, A. N., Cheevadhanarak, S., Jirakkakul, J., Dulsawat, S., Prommeenate, P., Tachaleat, A., Kusonmano, K., Wattanachaisaereekul, S., & Sutheeworapong, S. (2021). Comparative Metagenomics Reveals Microbial Signatures of Sugarcane Phyllosphere in Organic Management. Frontiers in Microbiology, 12. [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Z., Liu, Q., Pang, Z., Fallah, N., Liu, Y., Hu, C., & Lin, W. (2022). Sugarcane Rhizosphere Bacteria Community Migration Correlates with Growth Stages and Soil Nutrient. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 23(18). [CrossRef]

- Nam, N. N., Do, H. D. K., Loan Trinh, K. T., & Lee, N. Y. (2023). Metagenomics: An Effective Approach for Exploring Microbial Diversity and Functions. In Foods (Vol. 12, Issue 11). MDPI. [CrossRef]

- Gao, X., Wu, Z., Liu, R., Wu, J., Zeng, Q., & Qi, Y. (2019). Rhizosphere Bacterial Community Characteristics over Different Years of Sugarcane Ratooning in Consecutive Monoculture. BioMed Research International, 2019. [CrossRef]

- India production of sugarcane. Agriexchange.apeda.gov.in. (2022).

- Dos Santos, I. B., Pereira, A. P. de A., de Souza, A. J., Cardoso, E. J. B. N., da Silva, F. G., Oliveira, J. T. C., Verdi, M. C. Q., & Sobral, J. K. (2021). Selection and Characterization of Burkholderia spp. for Their Plant-Growth Promoting Effects and Influence on Maize Seed Germination. Frontiers in Soil Science, 1. [CrossRef]

- Jou, Y. T., Tarigan, E. J., Prayogo, C., Kobua, C. K., Weng, Y. T., & Wang, Y. M. (2022). Effects of Sphingobium yanoikuyae SJTF8 on Rice (Oryza sativa) Seed Germination and Root Development. Agriculture (Switzerland), 12(11). [CrossRef]

- Pang, Z., Tayyab, M., Kong, C., Liu, Q., Liu, Y., Hu, C., Huang, J., Weng, P., Islam, W., Lin, W., & Yuan, Z. (2021). Continuous sugarcane planting negatively impacts soil microbial community structure, soil fertility, and sugarcane agronomic parameters. Microorganisms, 9(10). [CrossRef]

- Chandra, A., Gaur, V., & Tripathi, P. (2021). Microbiome analysis of rhizospheres of plant and winter-initiated ratoon crops of sugarcane grown in sub-tropical India: utility to improve ratoon crop productivity. 3 Biotech, 11(1). [CrossRef]

- Alawiye, T. T., & Babalola, O. O. (2021). Metagenomic Insight into the Community Structure and Functional Genes in the Sunflower Rhizosphere Microbiome. Agriculture, 11(2), 167. [CrossRef]

- Prashar, P., Kapoor, N., & Sachdeva, S. (2014). Rhizosphere: Its structure, bacterial diversity and significance. In Reviews in Environmental Science and Biotechnology (Vol. 13, Issue 1, pp. 63–77). [CrossRef]

- Li, M., Liu, R., Li, Y., Wang, C., Ma, W., Zheng, L., Zhang, K., Fu, X., Li, X., Su, Y., Huang, G., Zhong, Y., & Liao, H. (2022). Functional Investigation of Plant Growth Promoting Rhizobacterial Communities in Sugarcane. Frontiers in Microbiology, 12. [CrossRef]

- Khan, A., Jiang, H., Bu, J., Adnan, M., Gillani, S. W., Hussain, M. A., & Zhang, M. (2022). Untangling the Rhizosphere Bacterial Community Composition and Response of Soil Physiochemical Properties to Different Nitrogen Applications in Sugarcane Field. Frontiers in Microbiology, 13. [CrossRef]

- Shahid, M.; Zeyad, M.T.; Syed, A.; Singh, U.B.; Mohamed, A.; Bahkali, A.H.; Elgorban, A.M.; Pichtel, J. Stress-tolerant endophytic isolate Priestia aryabhattai BPR-9 modulates physio-biochemical mechanisms in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) for enhanced salt tolerance. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 10883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, M., Sun, H., & Xu, Z. (2024). Characterization of Rhizosphere Microbial Diversity and Selection of Plant-Growth-Promoting Bacteria at the Flowering and Fruiting Stages of Rapeseed. Plants, 13(2). [CrossRef]

- Zelaya-Molina, L.X.; Guerra-Camacho, J.E.; Ortiz-Alvarez, J.M.; Vigueras-Cortés, J.M.; Villa-Tanaca, L.; Hernández-Rodríguez, C. Plant growth-promoting and heavy metal-resistant Priestia and Bacillus strains associated with pioneer plants from mine tailings. Arch. Microbiol. 2023, 205, 318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, M., Cui, L., Sun, H., Zhang, X., Zheng, X., & Jiang, J. (2021). Effects of spartina alterniflora invasion on soil microbial community structure and ecological functions. Microorganisms, 9(1), 1–16. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).