1. Introduction

With the growing digitization trend, graphic design has become a vital skill (Rafiyev et al., 2024). However, this skill usually has a steep learning curve for beginners and requires intense effort to understand and master. Such a challenge is largely associated with traditional graphic design software like Adobe Illustrator, Adobe Photoshop, and CorelDRAW, developed with a focus on users with professional skills. In other words, these traditional tools are characterized by complex interfaces and complicated features, that cause users without prior experience of usage to struggle to acquire practical design skills(Atuweni & Mtende, 2024; Fahmi Romisa & Dewi Rosita, 2024; M. Fakhri Sholahuddin & Tata Sutabri, 2024; Nouraei et al., 2024; Tang, Zhang, et al., 2024). The prominence of this problem is mostly seen in settings where access to technical knowledge regarding graphic design is limited. Again, as software applications keep getting more sophisticated with regular updates due to changes in demand, the technical expertise required for their use also grows proportionally (Baltes & Diehl, 2018; de Campos et al., 2023, 2024; Glazunova et al., 2022). In the graphic design field, this has created the urgency of seeking alternatives that provide beginner-friendly solutions, allowing a wider pool of students to easily gain relevant practical design skills. Such user-friendly solutions aim to simplify the learning process and eliminate the initial difficulty surrounding the acquisition of practical design skills. As noted in (Tella et al., 2024) , traditional design tools are usually cost-demanding since they need to run on computers with high hardware specifications to ensure a smooth flow of work. Additionally, on cost, they pose a challenge of time-consuming skill acquisition and require users to have the prerequisite technical knowledge of various design concepts (Atuweni & Mtende, 2024). To make it worse, Kyrylashchuk & Kolomiiets (2024) argue that the sophisticated environments of these traditional graphic design tools are not enabling enough to encourage self-learning for the average student. Therefore, users usually need to bear the exclusive cost of engaging experts for such foundational knowledge. Such high cost and resource demands tend to disincentivize learners from wanting to further the graphic design learning process. Moreover, even for students whose interests remain intact amidst the cost and resource challenges, realistically, accessibility becomes an issue in cases where such students are from underprivileged communities. In graphic design education, because these gaps cause a decline in the level of interest of beginners, especially for those in resource-constrained areas, they need to be urgently addressed (Salim et al., 2021). In this paper, we present the Invest-In-Her AI-Assisted Learning and Practice (IHH-AILP) Model, a pedagogical framework that leverages AI-powered graphic design platforms to improve the practical design skills of beginner students. AI-powered graphic design platforms like Canva and Adobe Firefly, are designed to reduce graphic design sophistication and enable beginner learners to seamlessly enhance their creative skills (Salim et al., 2021; Torta & Saalmuller, 2024). Contrary to traditional tools, they are developed with a focus on ease of use and user-friendliness and offer features like real-time feedback, relatable templates and automation of design recommendations (Salim et al., 2021). Such features eliminate the possibility of beginners being overwhelmed and help in actively sustaining their interests in learning graphic design. In our proposed beginner-friendly model, an AI-emphasized structured pathway is provided to help learners gradually grasp practical design skills. This structure is such that it starts with very basic activities, and as learners gain a good understanding of concepts, it conveniently transitions into complex tasks. Additionally, with the integration of AI to support at every step, the IIH-AILP fosters an enabling environment for self-learning and focuses on addressing challenges in conventional design education by making available a cost-effective, inclusive, and accessible learning engagement for beginners. This research has three main objectives. The first is to assess how AI-driven platforms enhance learners' ability to acquire practical graphic design skills and produce creative, original outputs compared to traditional tools; the second is to measure the extent to which AI-powered tools improve task completion times, sustain user engagement, and motivate learners throughout the design process; and finally, to determine how AI-powered tools create an accessible and inclusive learning environment, particularly for individuals with little to no prior technical expertise.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows; in

Section 2 we present a review of related literature. In

Section 3 we present the proposed framework.

Section 4 focuses on the analysis of the results presented, and finally,

Section 5 provides the Summary and Conclusion of the paper.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Challenges in Acquiring Graphic Design Skills Using Traditional Tools.

There are significant limitations beginners face regarding the use of traditional graphic design tools like Adobe Photoshop, CorelDRAW, Adobe Illustrator, etc. Wang & Chen (2024) highlighted that traditional tools are usually characterized by complex interfaces that can overwhelm beginners. They also argued that for beginners a lot of features in the traditional end up not being used because of the sophistication in the software environment. Additionally, in (Materne, 2024; Wang & Chen, 2024), authors also discussed the learning curve challenge beginner learners are faced with regarding the use of traditional graphic design tools. They opined that these learners are usually left to battle their way through gaining mastery over the complex functionalities of traditional tools. Again, in most instances, individuals with little to no prior technical design skills are unable to seamlessly adapt to the use of traditional tools, as they don’t appear beginner-friendly (Materne, 2024; Wang & Chen, 2024). Niu & Guan (2024) also, note another perspective of the limitation of traditional tools like Adobe Photoshop present. They indicated that these traditional graphic design applications only suit high system requirements that as such may narrow the accessibility scope, especially for the majority of beginner learners. On computers with less powerful features, these applications will be made to run slowly and hence affect the creative processes and outputs. The focus of this study is more geared towards addressing the challenges of steep learning curves and complex functionalities through the proposed model framework, to boost the incentives of beginner learners to actively engage in the learning process and hence enhance their practical design skills.

2.2. The Uniqueness of AI-Driven Platforms

Generally, the field of graphic design has been hugely impacted by the revolution of AI-powered platforms like Canva AI. These platforms have proved to be more suitable for beginners as they drastically reduce the learning process complexities and make the design process more accessible and interactive(Tahsin & Azzahra, 2024). The AI-driven platforms present engagement-enabling environments where beginners do not require any critical prior technical expertise to navigate through with ease due to their user0firndy interfaces that enhance the design process(Tahsin & Azzahra, 2024). In (Qu et al., 2021), it was stated that AI platforms like Canva AI, reduce difficulties for learners and make the platform more accessible to all kinds of individuals irrespective of their level of design expertise. Tang, Ciancia, et al. (2024) also explained that AI-driven platforms foster real-time collaboration among designers and automate repetitive tasks to allow users to focus on more challenging tasks and eliminate delays and redundancies. Furthermore, there is a heightened user engagement on such platforms (Tang, Ciancia, et al., 2024). This viewpoint is also highlighted in (“The Impact of Artificial Intelligence on the Graphic Design Industry,” 2023). Another unique advantage presented by AI-powered tools is the provision of feedback and support during the design process which encourages self-learning and cuts down reliance on external assistance (Atuweni & Mtende, 2024). These unique benefits characterizing AI-driven platforms are the reasons why our proposed IIH-AILP mode framework leveraged them as the core tools for implementation.

2.3. Pedagogical Models for Practical Skill Development

Within pedagogy, traditional teaching methods are mostly unable blend theoretical understanding with the hands-on practical when required (Patel et al., 2021; Yue, 2024). In (Yue, 2024) , the author explains that pedagogical theories or frameworks with good emphasis on practical applications, like the proposed IIH-AIP model, accelerate student motivation and engagement. Various pedagogical model frameworks to boost the practical understanding of students in different fields of study other than computing have been presented in (Lits, 2024; Shilkova et al., 2023; Vasylyshyna, 2022; Zharov et al., 2022). In (Curcic, 2024; Duong & Nguyen, 2024; Headleand & James, 2024; HORINCHOI & POLYAKOV, 2023; Maksymchuk et al., 2024; Mayor-Peña et al., 2024; Rui & Yang, 2024) however, pedagogical frameworks were implemented to specifically enhance the graphic design skills of learners. None of which leveraged AI-driven tools for such facilitation or provides any cost-effective framework that incorporates variety of features for addressing different needs and levels of learners to enhance engagement and inclusivity. Muji et al., (2023) and Atuweni & Mtende, (2024) present methodologies that explore the use of AI tools to enhance the practical graphic design skills of respective groups of individuals. The studies come with noticeable gaps which are addressed by our proposed IIH-AILP model. In (Muji et al., 2023), there is a lack of a structured pedagogical framework to integrate AI tools for practical development. Additionally, the methodological frameworks in (Atuweni & Mtende, 2024; Muji et al., 2023) assume some prior expertise on the part of learners and hence do not fully accommodate beginners. Again, there is no provision for comparative analysis against traditional tools to validate the proposed frameworks’ superiority. Furthermore, no clear-cut strategy id provided to sustain the incentive of learners through features like gamification via rewards and leaderboard systems. Finally, just like in many other studies, the methodology in (Muji et al., 2023) is almost entirely conceptual with limited validation of its practical feasibility. Such gaps were fundamental to what we sought to achieve by developing the IIH-AIP model framework.

Figure 1.

Overview of Methodology (Flowchart).

Figure 1.

Overview of Methodology (Flowchart).

3. Methodology

3.1. Implementation Overview

3.2. Participants Selection

The study engaged 55 students of the Invest-In-Her program at AAMUSTED, Kumasi, Ghana. The Invest-In-Her program was a collaboration between AAMUSTED, World University Service of Canada (WUSC), and the Ghana Chamber of Construction Industry (GCCI), and sponsored by Global Affairs Canada (AAMUSTED, 2024). The participants, all females, were selected because the study focuses on beginner-level students with little to no prior graphic design expertise.

3.3. Demography & Pre-Intervention Assessments

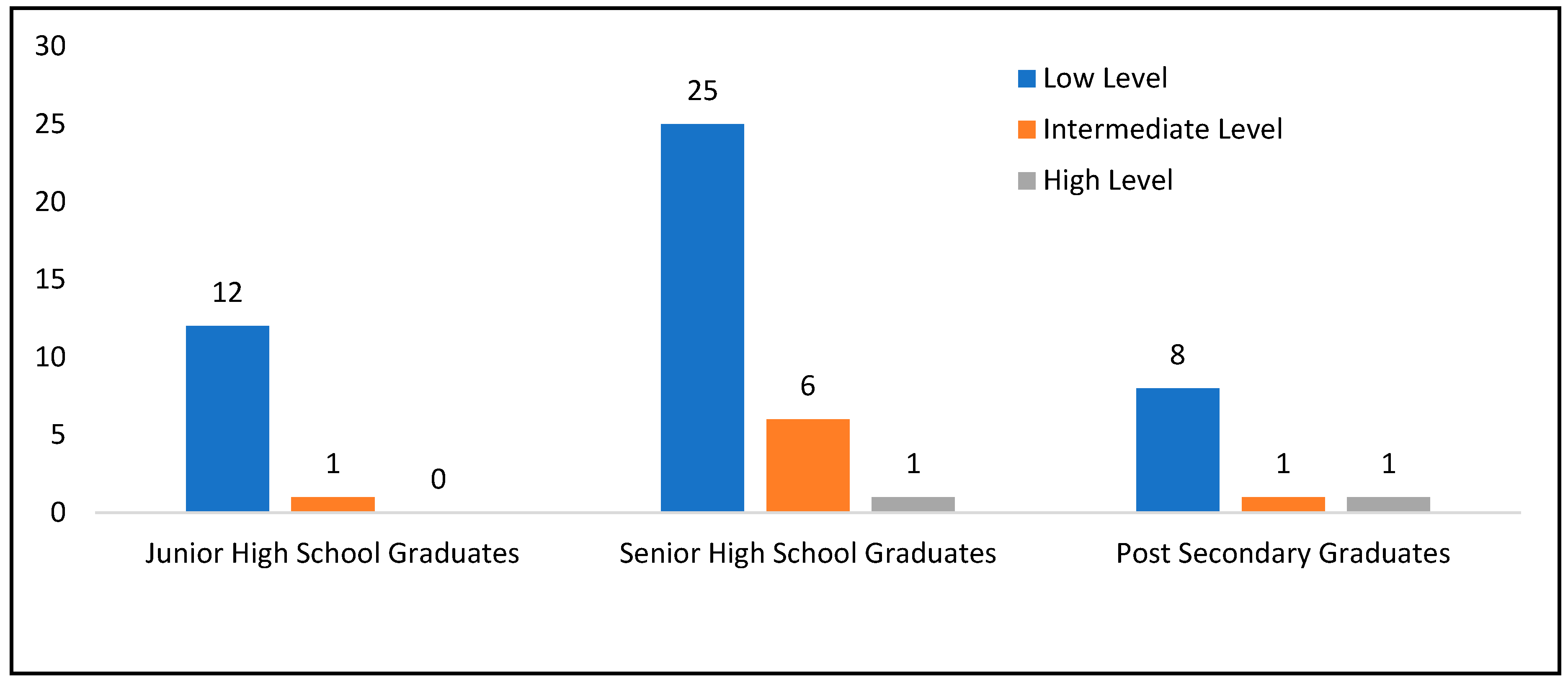

Both

Figure 2 and

Table 1 present an elaborative breakdown of the participant’s demography. These participants aged 16 to 25 years, are categorized under three levels as beginner learners; low-level, intermediate-level, and high-level beginners. This categorization was determined at the start of the Invest-In-Her program after participants were interviewed. The reason for categorizing was to help inform instructors on the diverse teaching strategies to adopt to ensure student-centered hands-on practical sessions. Even though all learners were considered beginners, such sub-categorization was relevant to appreciating the individual differences among the groups of learners to avoid a blanket generalization of their prior knowledge of graphic design tools. While

Table 1 provides further details on what it means for a participant to be categorized under each sub-level (low, Intermediate, and High) , ,

Figure 2 also gives a breakdown of the participants’ academic levels. In both illustrations, it is seen that the participants categorized as low-level beginners form the greatest percentage of the sample (approximately 82%), followed by the intermediate-level (approximately 14%), and then finally the high-level beginners who make up just 4% (approximately).

3.4. Implementation of the IIH-AILP Model (Intervention)

The IIH-AILP Model is a pedagogical framework that leverages AI-powered graphic design platforms to improve the practical design skills of beginner students. This novel framework is developed to structurally enhance the practical design skills of beginner students by incorporating Artificial Intelligence (AI) as a scaffolding tool. The idea of the IIH-AILP framework is to take advantage of the guided automation and easy-to-understand interface features of AI-powered platforms to drive the ease of comprehension among students. It was implemented over 12 weeks. The intervention adopted multiple AI-powered tools with very similar features and functionalities. Canva was used for beginner-level designs, while Adobe Firefly was later introduced for advanced designs. Participants were introduced to traditional tools like Adobe Photoshop to satisfy the comparative evaluation phase of the proposed model.

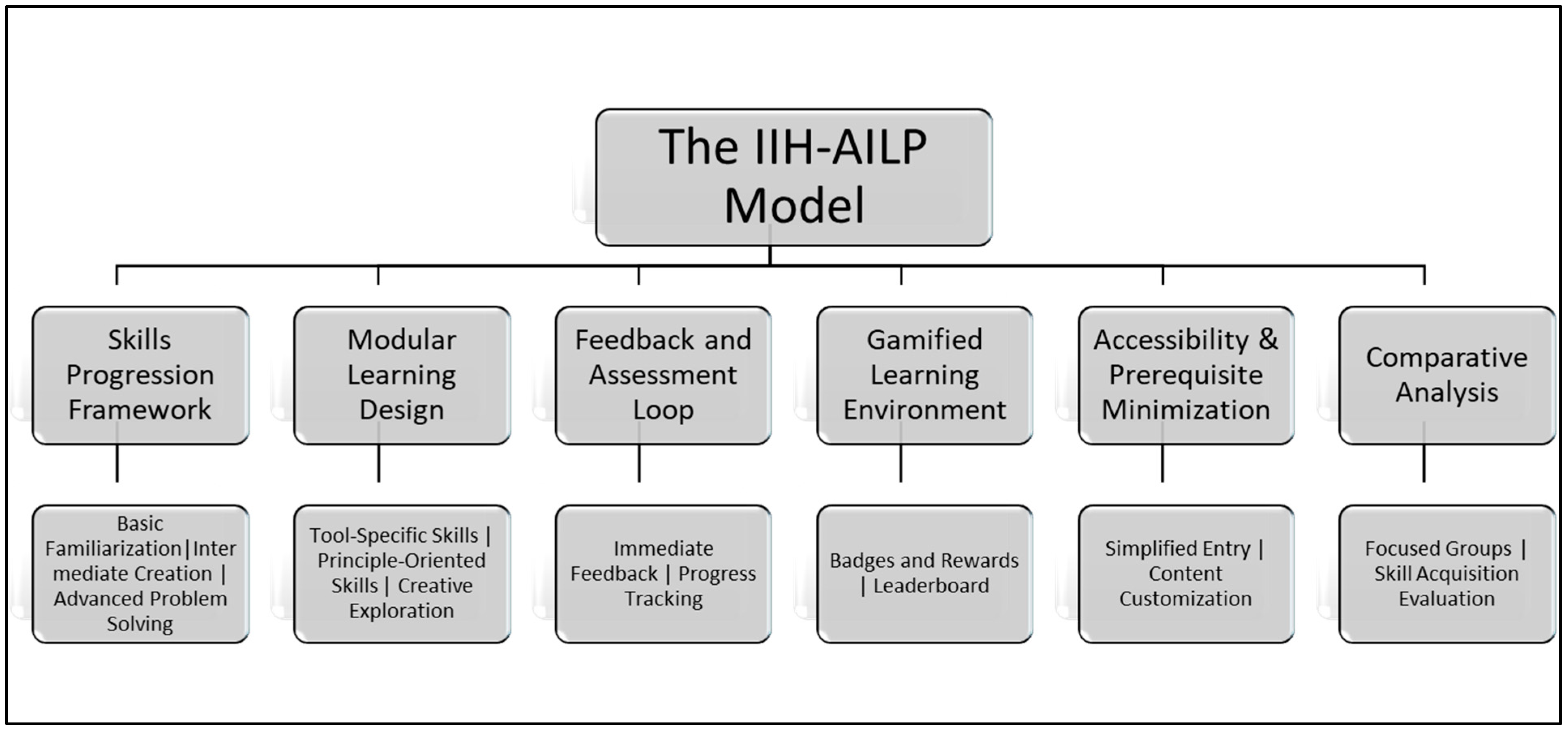

Figure 3 gives a visual illustration of the IIH-AILP’s conceptual framework. The model comprises 6 innovative components that are interwoven to structurally guide learners to first understand the use of basic graphic tools and then conveniently transition to more challenging and creative problem-solving tasks.

The Skills Progression component is a core highlight of the entire model. It constitutes three (3) stages. The first is the basic familiarization or foundation stage where learners are introduced to the selected AI-driven platform’s tools, workflows and user interface. At this stage, the role of the AI tool is to make navigation easy via automated suggestions and pop-up features. At the intermediate creation which we also call the application stage, through the application of concepts like layering and composition, the learners are made to modify designs created by AI. The assistance provided by the AI at this stage is offering feedback on alignments, highlighting design incoherence or redundancies, and making change suggestions. Finally, learners are then made to create original designs independently, while the AI feature gives an option for users to either accept or reject recommendations on improvements. Again, the AI feature gives an automated assessment of the quality of the work.

The Modular Learning design decomposes the learning process into independent units comprising of skills that are tool-specific, principle-oriented, and creative explorative. The goal here is to make learners have mastery over each independent skill. The tool-specific skills comprise color palettes, auto-layouts, and text alignment. The principle-oriented abilities to be checked and applied appropriately are proximity, contrast, alignment, and repetition. Finally, in creative exploration participants are urged to craft originality by experimenting with designs created by AI.

The Feedback and Assessment Loop Is Ir essential component of the IIH-AILP, as it leverages AI to give instant feedback from instructors through real-time collaborative features. It also incorporates the use third-party AI analytics tools like Feng-GUI, and Attention Insight, for assessing design complexity, and Toggl Track, and Clockify to track the growth of learners via time spent on tasks. This component allows for documentation of students’ development and easy tracking of their progress. Additionally, instructors can conventionally give real-time feedback to learners as a result of the real-time collaborative feature present within AI-powered graphic design tools. This component also includes collaborative group discussions between instructors and learners to collectively assess and critique designs of different kinds.

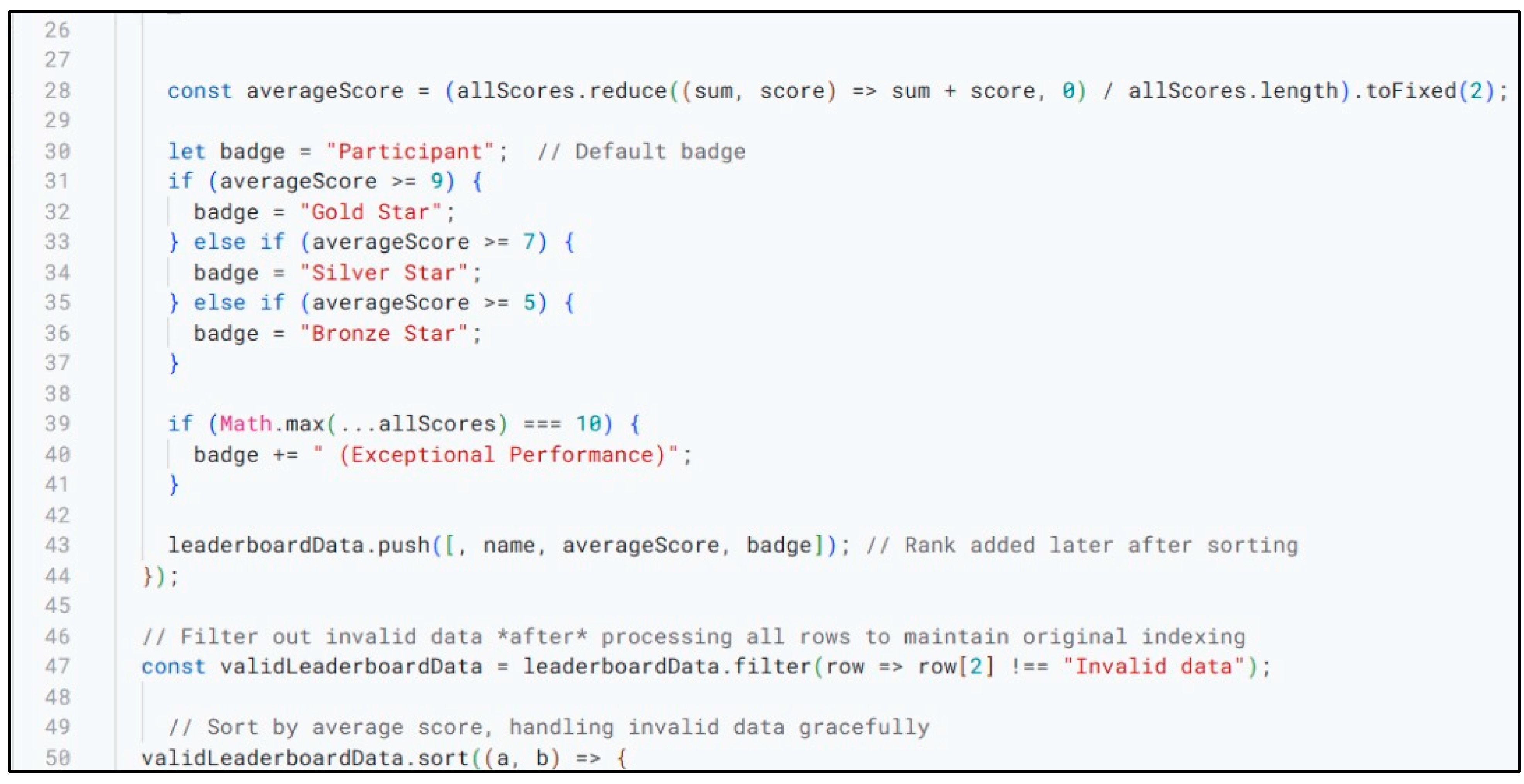

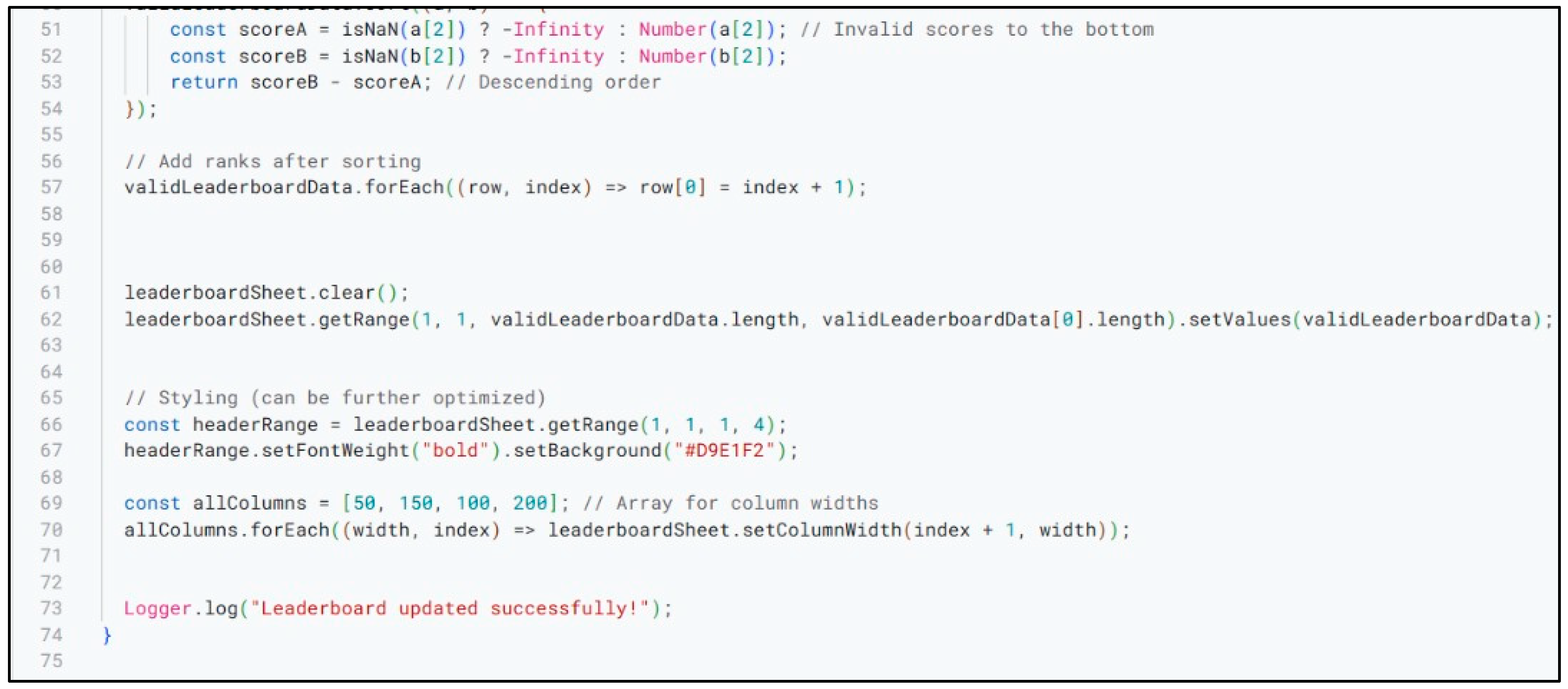

As a pedagogical framework, the IIH-ALP requires the incorporation of a Gamified Learning Environment that is used to boost the incentive and sustain the interest of learners. Our proposed system implements such components via the Apps Script feature in Google Sheets where Badges and Leaderboards are automatically generated with inputs of students’ scores by instructors.

Figure 4,

Figure 5 and

Figure 6 represent sections of the implemented script with inputs from a Sheet named “Scores” that contains the Name of Learners on one column and 6 other columns for the entry of their scores for each task under the Skills Progression component and Modular Learning design. The badges are automatically generated depending on the average score of the student while the Leaderboard is automatically sorted to display the name of the best performing student on top. Instructors collaboratively share access to the “Score” sheet to make inputs while learners access updated Leaderboards via the HTML view feature in Google Sheets.

The Accessibility and Prerequisite Minimization unit was included purposely to ensure that learners who lack prior technical expertise are still able to seamlessly access and effectively learn graphic design. This is achieved through simplified entry features where learners use drag-and-drop functionality. It is also implemented via customized tutorials and tasks streamlined to fit each learner’s level of skill and pace to yield a user-centered learning experience. This component is considered implicit after the setup at the initial stage of the model implementation.

The final component of the proposed model illustrated in

Figure 3 allows for a Comparative analysis of the perception of students about the intervention which leverages AI-powered platforms like (Canva and Adobe Firefly), and the use of traditional graphic design tools (Adobe Photoshop, Adobe Illustrator). These comparatives pave the way for a thorough assessment of the model’s effectiveness through metrics like skill acquisition speed, ease of use, accessibility, retention rate, motivation, task completion accuracy, etc. Again, since generally the Invest-In-Her program curriculum already incorporates the exclusive introduction of learners to traditional graphic design tools, it makes it possible for such effective and unbiased comparative analysis on various metrics to be implemented.

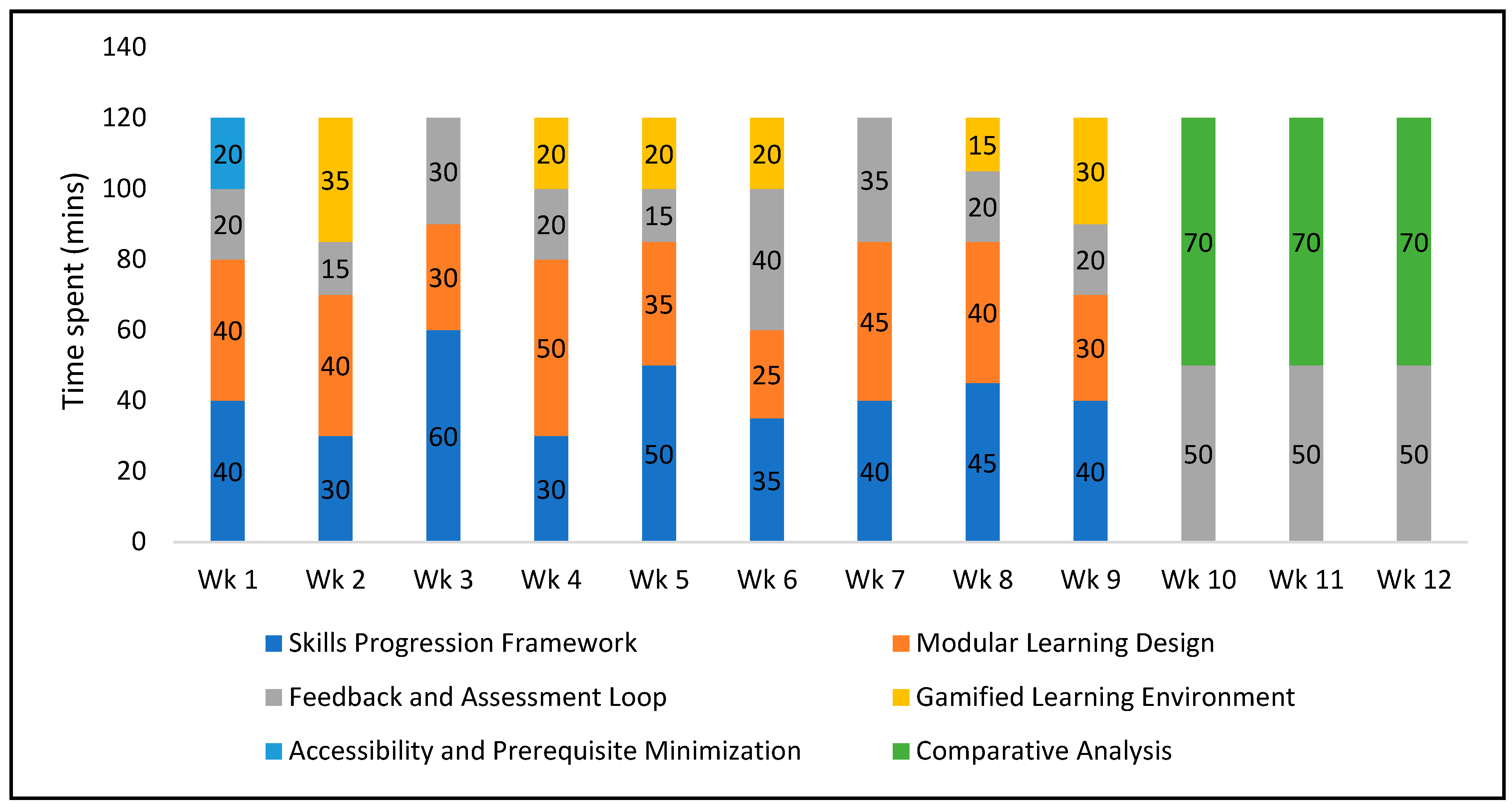

Table 2 details the weeks in which components of the IIH-ALP were implemented and their respective mode of execution (i.e sequential, parallel, or integrated). For each weak, Facilitators are allowed 120 minutes to exclusively engage learners on AI-driven graphic design. Aside from the Feedback & Assessment Loop that runs through from Week 1- 12, all other components were implemented in selected weeks. In (Adarkwah, 2021; Bhagya Prabhashini C & M. Latha, 2024; Ray et al., 2022), authors explained the crucial role feedback and assessment play within pedagogy. They argued feedback and assessment help continuously enhance teaching methodologies, boost student engagement, and yield enhanced educational outcomes. It was deemed fit to include this component in all weeks’ activities. However, unlike the other weeks where the focus was placed on learners’ designs, Feedback and Assessment for Weeks 11 and 12 were specifically targeted at group assessment and critiquing of a variety of graphic designs.

Figure 6, provides a breakdown of exactly how much time (out of the total 120 minutes) is allocated to executing the tasks under the given components in the IIH-ALP. For example, in Week 1, time allocations were as follows; 20 minutes for Accessibility and Prerequisite Minimization, 40 minutes for Skills Progression Framework, 40 minutes for Modular Learning Design, and finally, 20 minutes for Feedback and Assessment Loop.

Figure 7.

Time spent on each task for the 12-week intervention period.

Figure 7.

Time spent on each task for the 12-week intervention period.

3.5. Measurement Evaluation Metrics

To properly evaluate the IIH-AILP model framework’s effectiveness, the following evaluation metrics were selected. These align with the study’s objectives and the AI-driven tools’ unique features. Generally, these metrics were used to assess learners under the respective beginner category (i.e. Low-level beginners, Intermediate-level beginners, and High-level beginners).

3.5.1. Learning Curve/ Skill Acquisition

This metric is used to assess the rate at which learners with little to no prior technical knowledge can grasp graphic design skills after going through the IIH-AILP intervention. As a means of effective assessment, a productivity threshold or benchmark score of 14 out of 20 (70%) was set by instructors, such that any participant who attains such score or more is declared as capable of producing independent works. The Participants’ learning curves were estimated by administering weekly design projects to track progress. Learning curves are created for each beginner category (low-level, intermediate-level, and high-level) and compared to verify the proposed model’s accessibility and inclusivity goal. Below is the rubric used for scoring learners to determine their learning curve.

Table 3.

Learning Curve Evaluation Rubric.

Table 3.

Learning Curve Evaluation Rubric.

| Criteria |

Excellent (4) |

Good (3) |

Fair (2) |

Poor (1)

|

Task Completion

|

The tasks were of a high standard and completed within the given time.

|

Most tasks were completed within the given time and were of good quality. |

Quality is below average standard and struggled to complete tasks on time. |

Failed to complete tasks on time with unsatisfactory quality. |

Tools Proficiency

|

Completed tasks independently with Excellent Mastery of all AI-powered tools.

|

Showed mastery over most tools and needed occasional guidance. |

Needed frequent guidance and has limited mastery over tools. |

Challenged with the use of basic tools and relies heavily on assistance. |

Problem-Solving Skills

|

Identified design problems and addressed them independently.

|

Required occasional assistance but resolved most design problems independently

|

Struggled to address challenges independently when not assisted. |

Entirely relied on others to resolve design problems. |

Design Principles

|

Consistent with the effective application of principles like alignment, balance, and contrast.

|

Design principles were applied in the majority of tasks with negligible flaws. |

Applied design principles, but inconsistently and with occasional errors. |

Barely applied any principles of design and had too many obvious errors

. |

Improvement Overtime

|

Significant progress and independence from the first to the last week. |

Needed occasional assistance but resolved most challenges independently. |

Whenever not assisted, struggles with addressing design challenges. |

Entirely relied on others to resolve design challenges. |

3.5.2. Task Completion Time and Efficiency

This metric leverage the average time used by learners under various beginner categories to quickly complete design tasks. These were compared to the average time instructors would expect an average intelligent person to complete the task. A percentage reduction in the completion time is estimated after participants are made to repeat a task.

3.5.3. Creativity of Output

This metric is used to evaluate the originality and level of innovation of designs produced by participants. Facilitators evaluate submitted designs on originality and execution of the concept with the guide of the rubric provided in

Table 4. Just like in the case of the Learning Curve metric, the benchmark score here is 14 out of 20 (70%).

3.5.4. Comparative Analysis IIH-AILP and Traditional Tools

Finally, the paper’s methodology adopted a comparative analysis approach to weigh the opinions of learners about using AI-driven and traditional graphic design platforms. These opinions were based on “Ease of Use” and Participants’ Engagement and Motivation” metrics. It is important to note that, beyond the implementation of the IIH-AILP and as a curriculum requirement of the Invest-In-Her program, learners were concurrently introduced to traditional graphic design tools; the basis for an effective comparative analysis of design outputs and perceptions of participants.

4. Results & Analysis

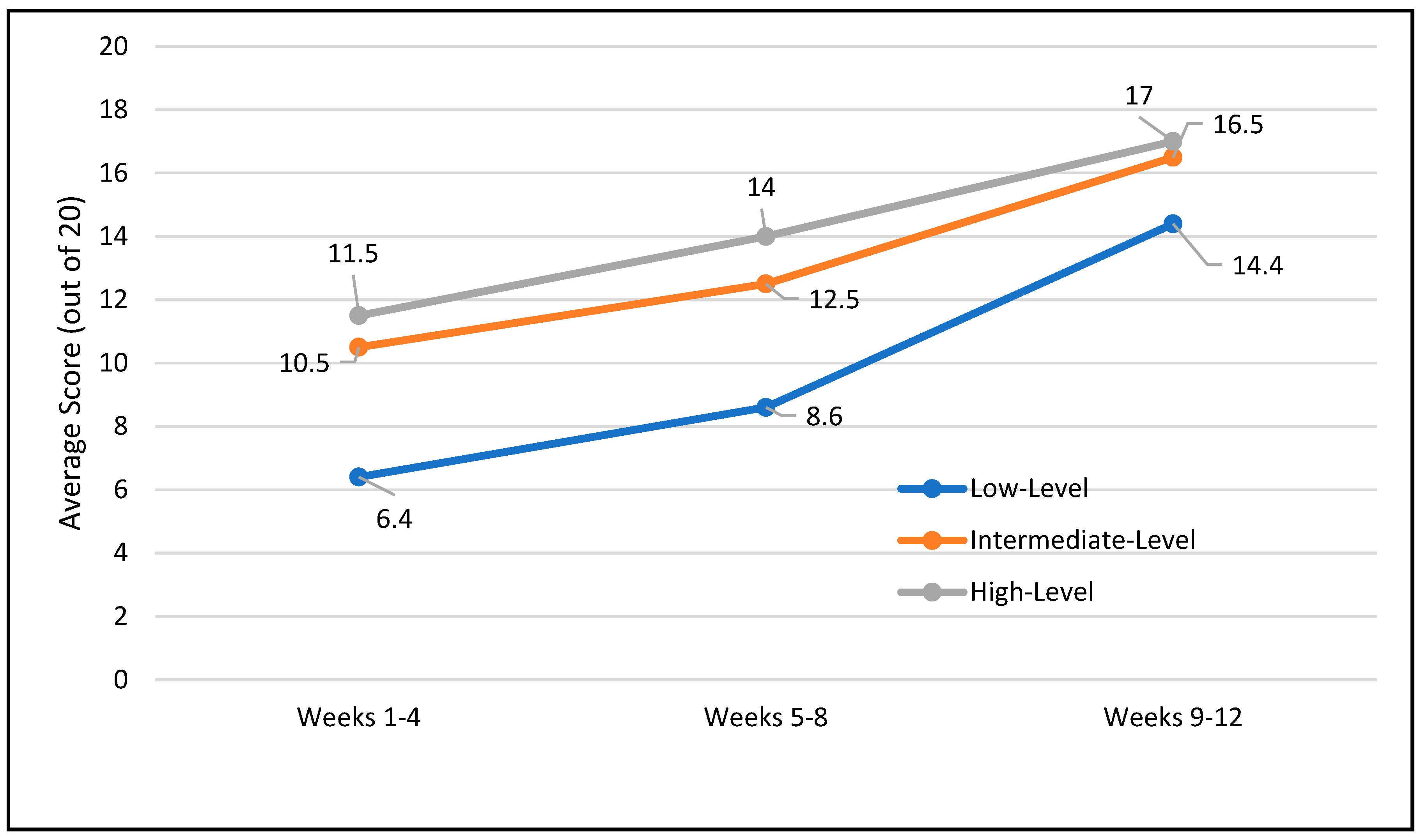

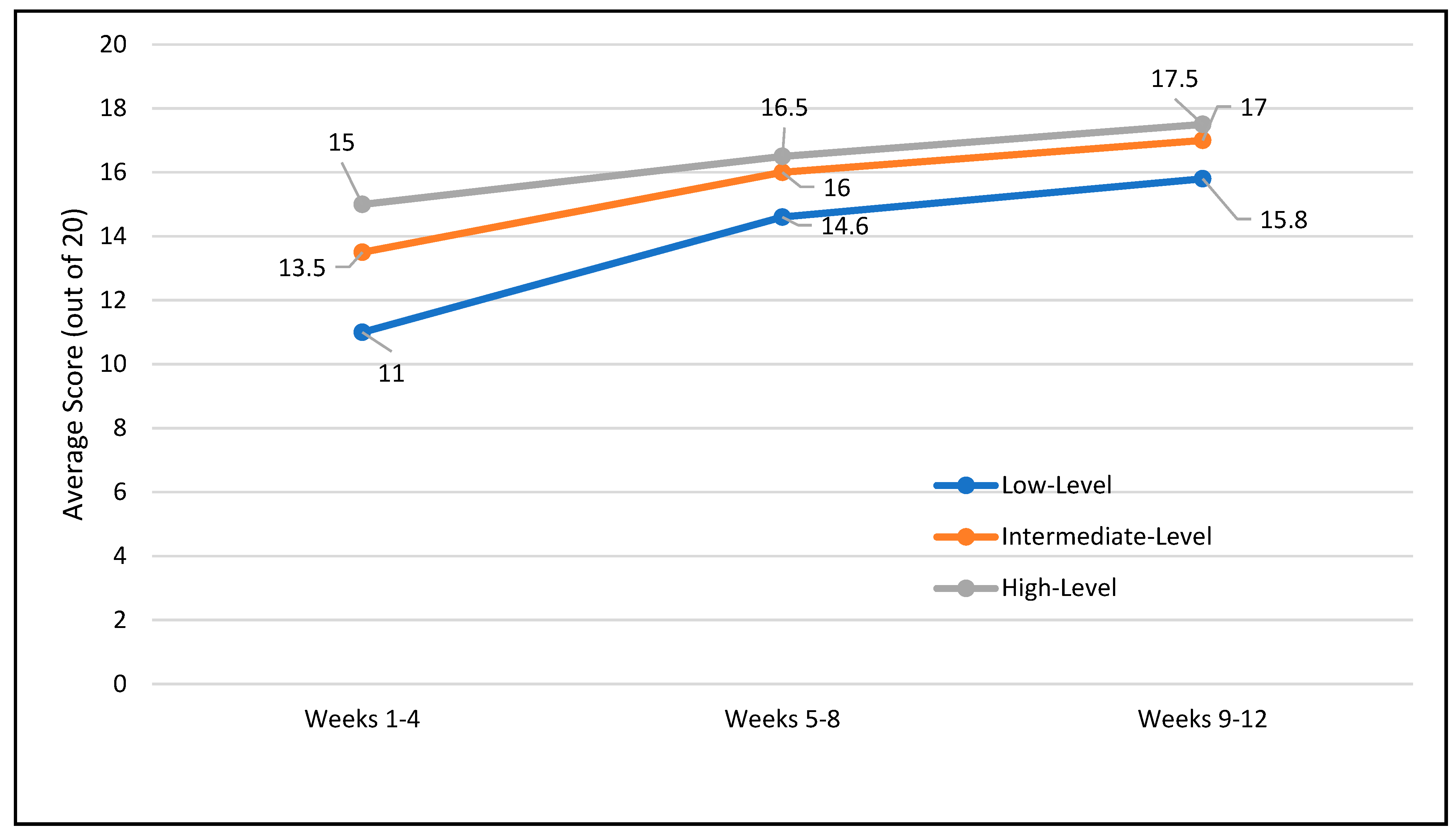

4.1. Learning Curve/Skill Acquisition

Figure 8 is an illustration of the averages of beginner learners at the three levels (low, Intermediate and High) as detailed in

Table 1, for each third (4 weeks) of the intervention. With final averages of 14.4 (72%) for low -level beginners, 16.5 (82.5%) for intermediate-level learners and 16.9 (85%) for high-level learners, the figure shows that all categories of beginner learners had impressively grasped graphic design skills. The IIH-AILP model can then be said to be effective regarding accessibility irrespective of an individual’s lack of prior technical knowledge in graphic design, because participants categorized as low-level beginners who had no prior technical skill or understanding in graphic design, and constitute 82% of the sample population, had a rise from 6.4 in the first quarter to 14.4 in the third quarter.

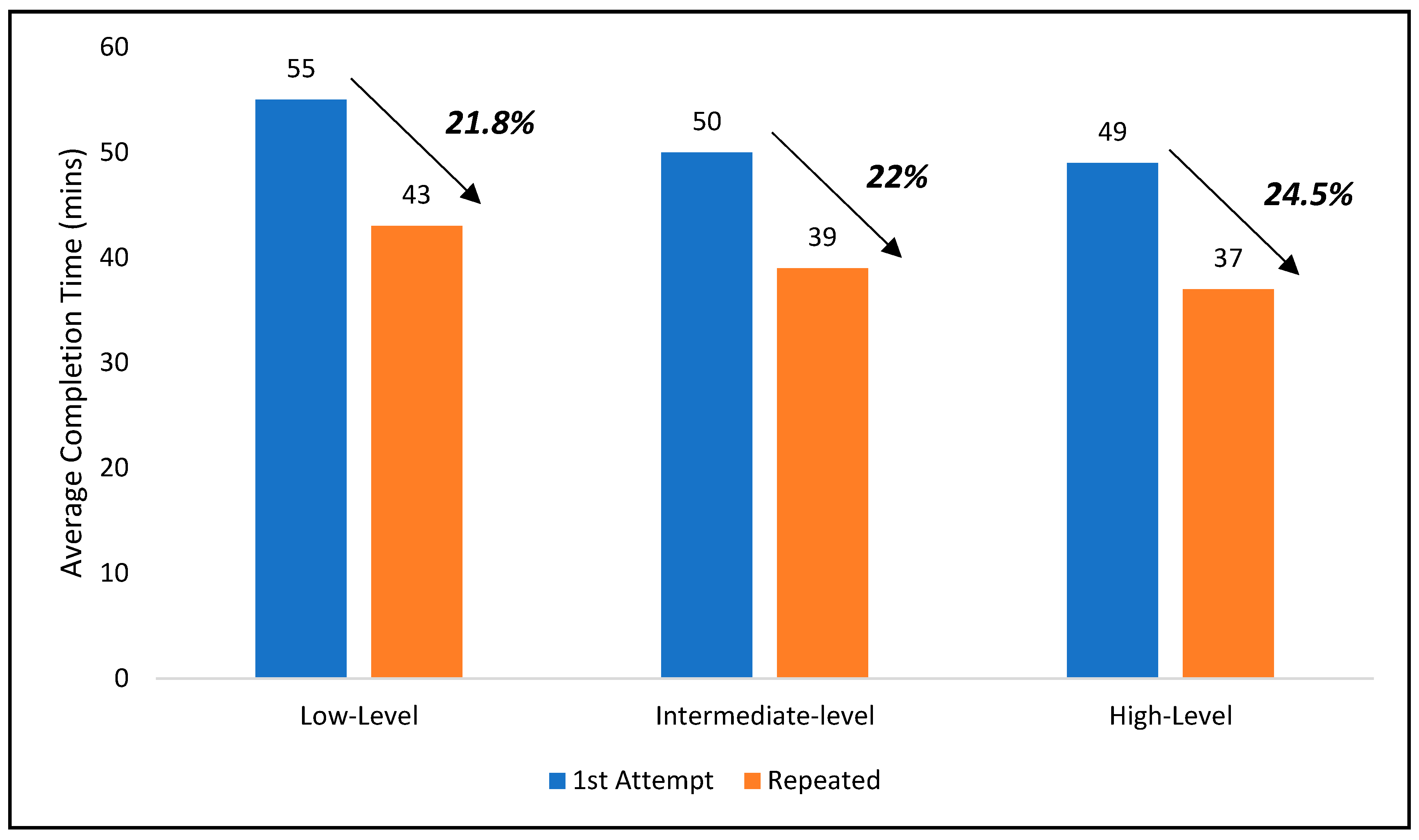

4.2. Task Completion Time and Efficiency

The task completion time assessment was done according to the categories of projects learners were assigned to and the average completion time of each level of beginner learners was compared to the average estimated time for completing the task (as determined by instructors) provided in

Table 5. Additionally, for each task, the average time for executing it the first time was compared to when it was repeated to determine the reduction time percentage.

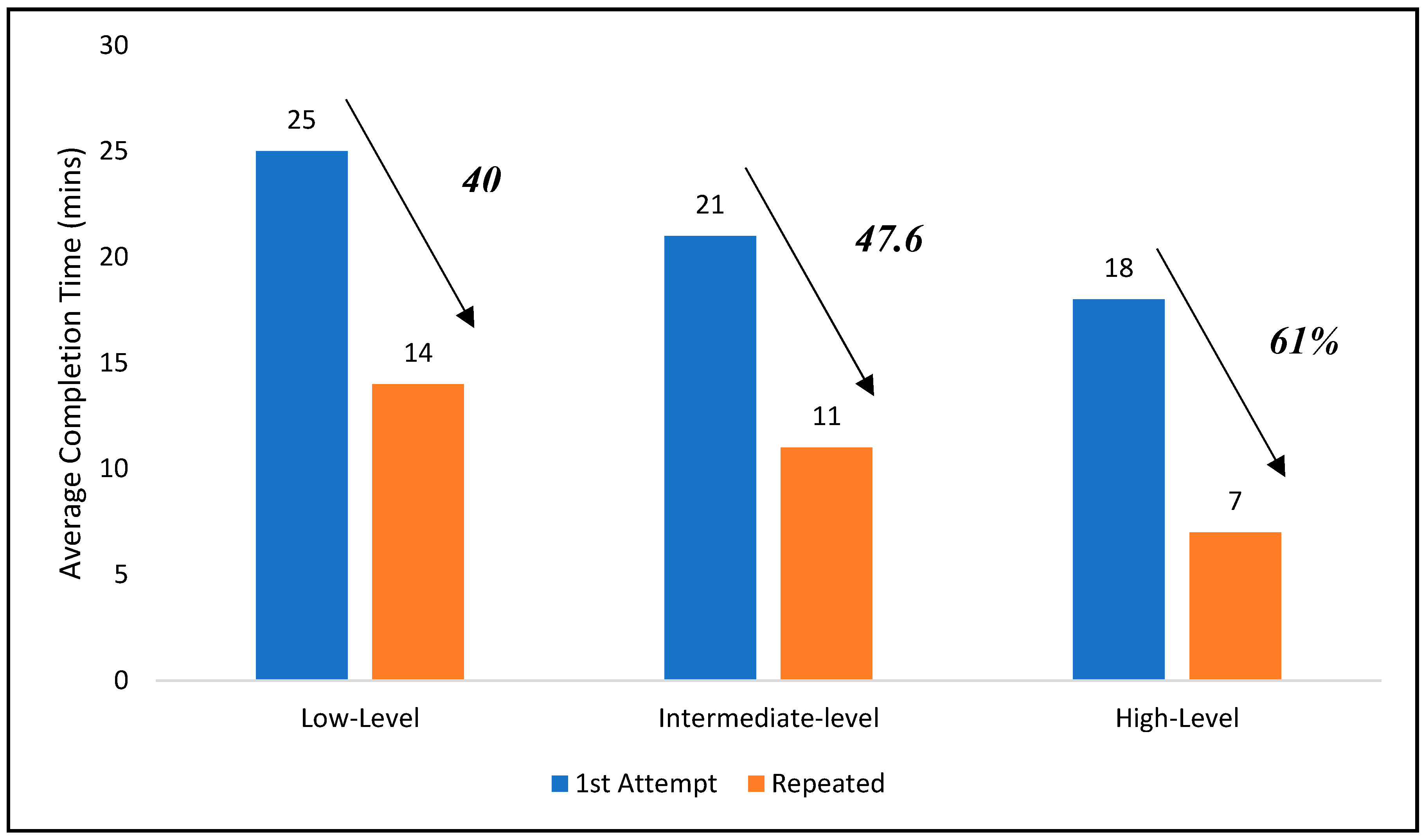

Figure 9 is an illustration of the average task completion time each category of beginner learners used for creating a personalized name tag. For each group of learners, a remarkable reduction in average completion time was recorded after when the intervention went further and tasks were repeated. The estimated time for completing this task (as indicated in

Table 5) was 15-20 minutes. It is logically consistent that participants categorized as high-level beginners who before the intervention, had some casual exposure to AI-driven platforms and basic design understanding, used an average of 18 minutes to complete the task. As earlier stated,

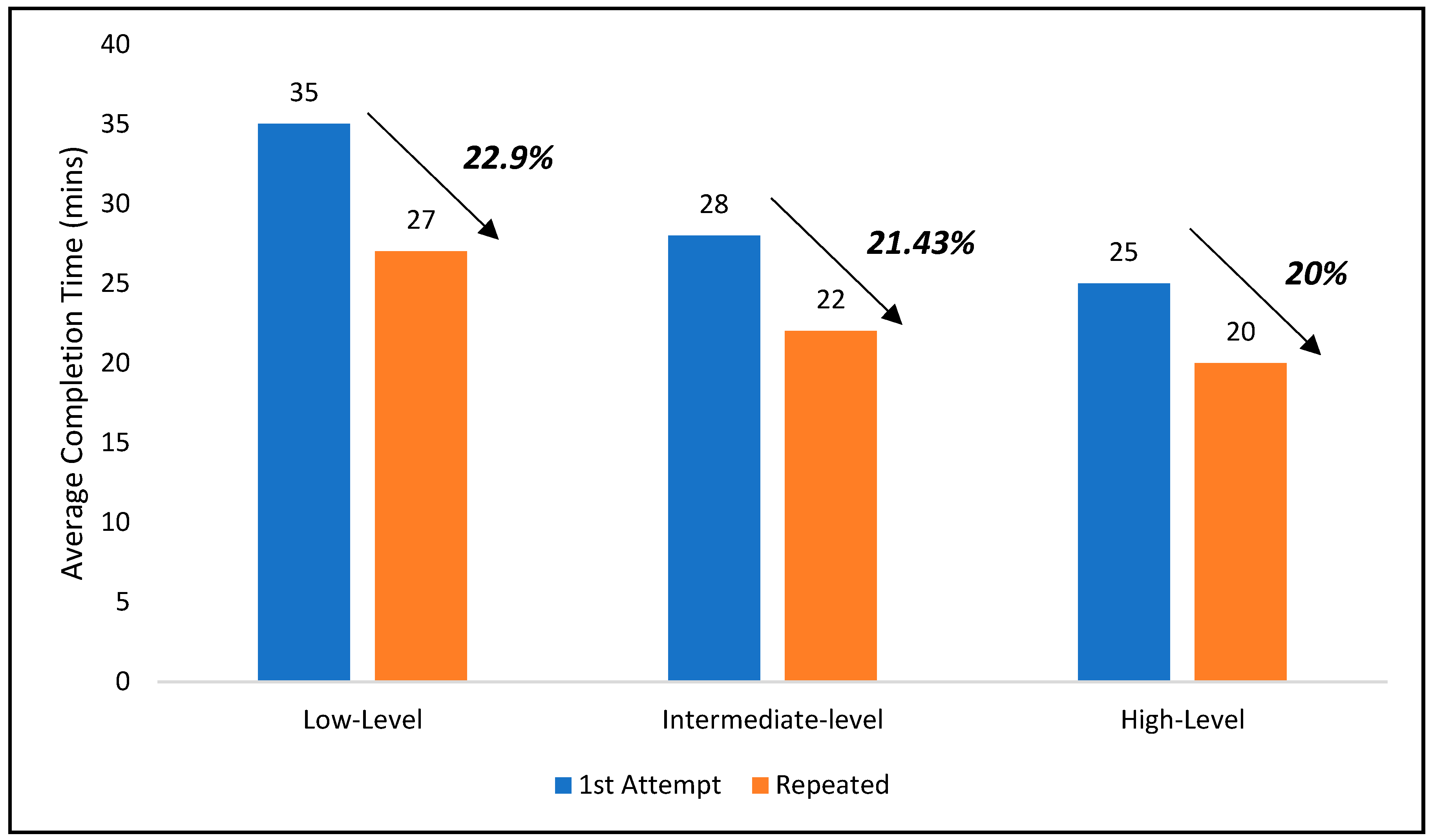

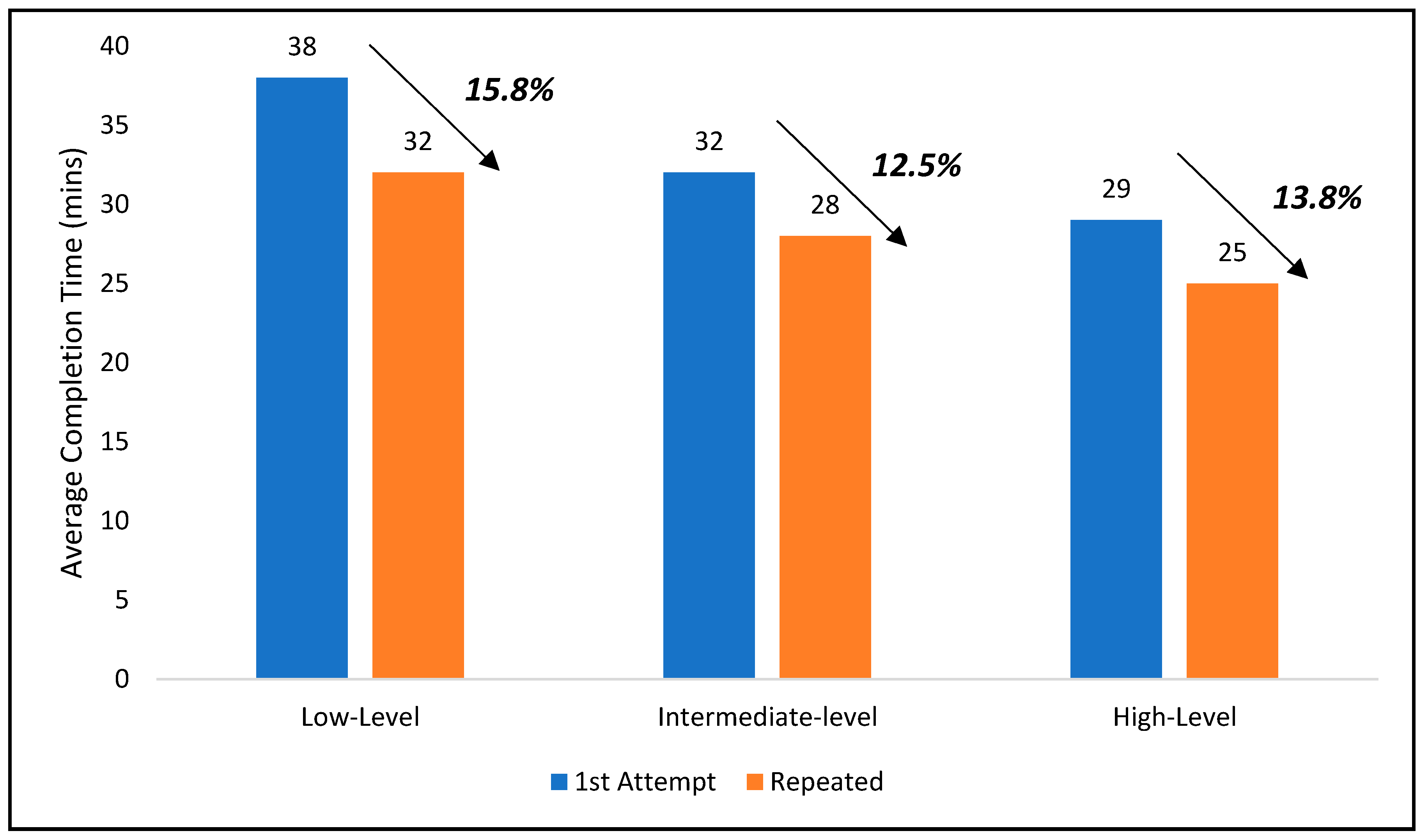

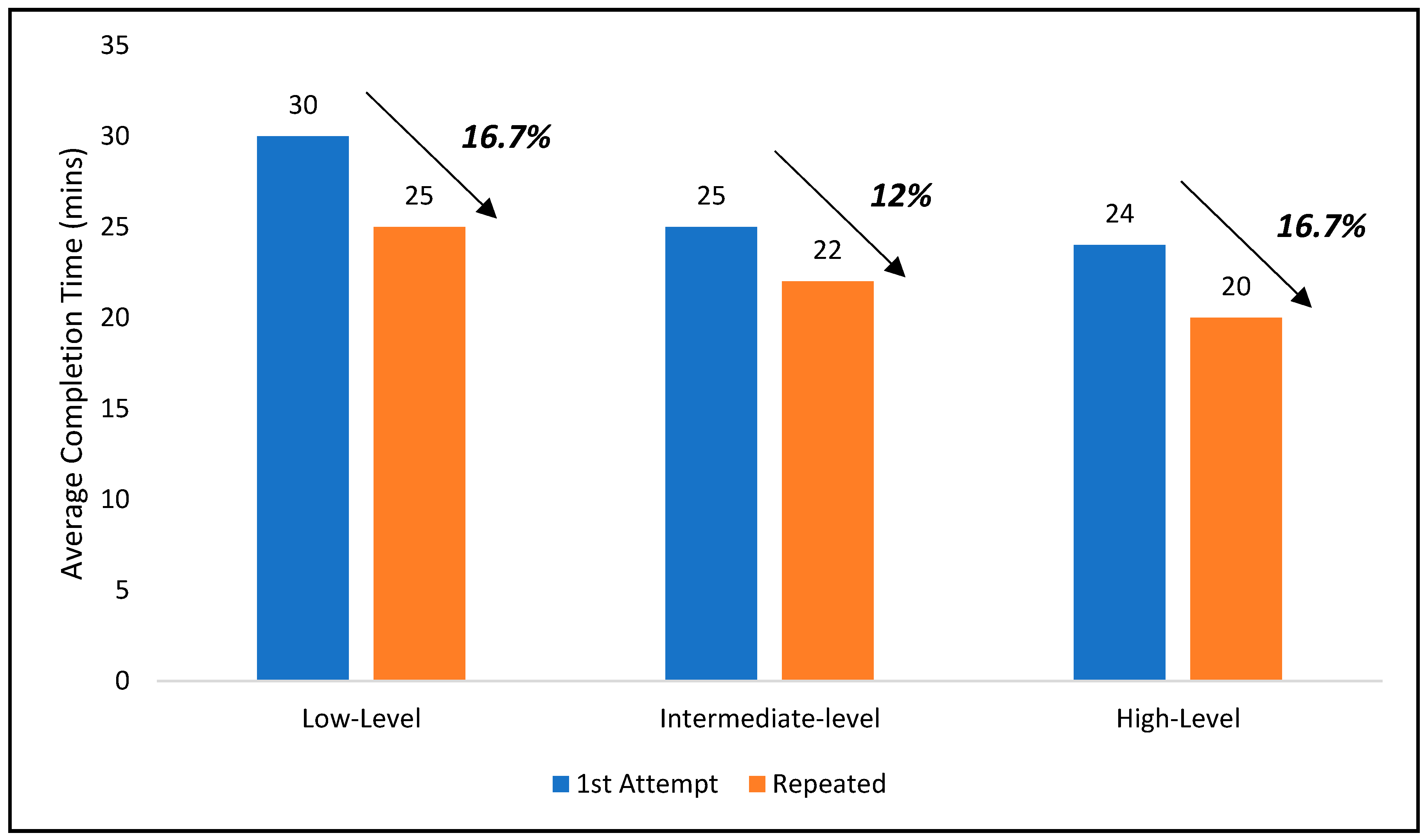

Figure 9 shows a 40%, 47.6%, and 61% reduction in average task completion times for low-level, intermediate-level, and high-level beginners respectively. This affirms the efficiency of the IIH-AILP model as it progressively causes learners to easily adapt to the use of AI-driven platforms hence making them faster at using their tools over time. The reduction in completion times is also attributed to learners’ ability to effectively utilize feedback suggestions from instructors and AI features. Similar observations regarding the remaining tasks as shown in

Figure 10,

Figure 11,

Figure 12, &

Figure 13; designing a simple event flyer (using a pre-made template), developing a business card (customized layout and colors), designing a social media post, and designing an infographic (custom layout, icons, and visuals)

Finally, it can be noted that for each progressing task, learners got better at meeting the expected completion time set by instructors even at their first attempt. This shows the progressive impact the AI-driven platforms had on learners via constant engagement, and how it positively affects their productivity as designers.

4.3. Creativity Output

Figure 14 illustrates the average scores of the participants regarding the creativity of their design outputs after each third (4 weeks) of the intervention. Just like in the case of the Learning Curve evaluation, the benchmark score set for creativity output was 14 out of 20 (70%), determined by the guide of the rubric presented in

Table 4. As shown in

Figure 14, by the 8

th week of the intervention, all three categories of beginner learners had successfully reached beyond the estimated threshold. The import here is that the IIH-AILP model was effective at enhancing the creativity sense among a group of learners characterized by 82% of individuals who were without any prior graphic design expertise. The results also indicate that as participants kept engaging with the AI-powered platforms, their creativity sense also grew proportionally. This can be mainly attributed to factors like user-friendliness, pre-requisite minimization, prompt feedback, and collaborative features of AI-driven platforms.

4.4. Comparative Analysis

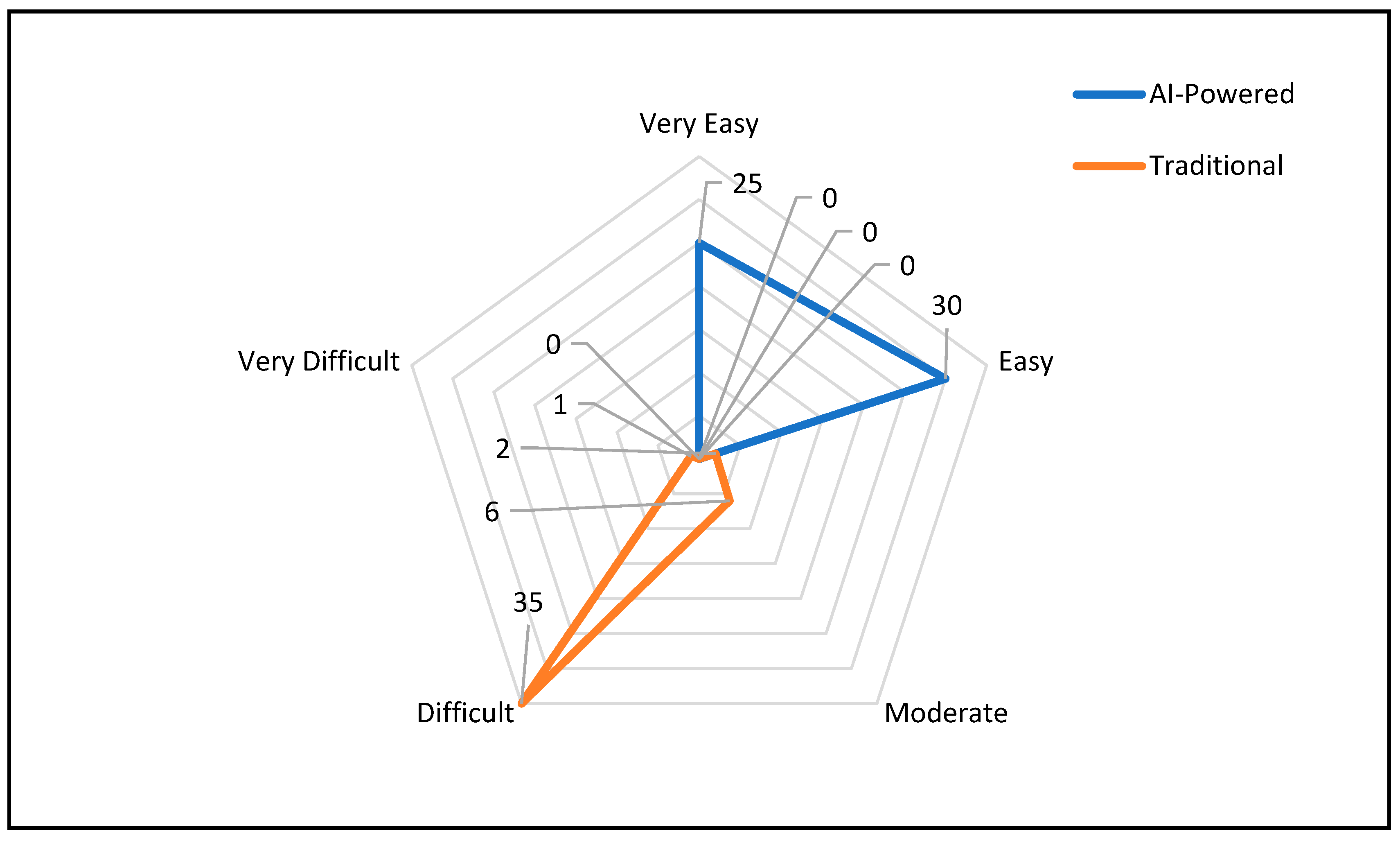

4.4.1. Perception of Ease of Use

Table 6 details the descriptions provided to participants regarding their choice of answer to the “Ease of Use” survey conducted on both traditional graphic design tools (Photoshop and Adobe Illustrator) and AI-powered ones (Canva AI and Adobe Firefly).

Figure 14 then provides insight into the perception of the 55 participants regarding the ease of use of traditional and AI-driven graphic design tools. From the illustration, 35 out of 55 participants, constituting 63.6%, rate traditional design tools as “Difficult” in terms of their ease of use generally. Meanwhile, regarding AI-driven tools’ ease of use, 25 out of the 55 participants, rated it as “Very Easy”, and the remaining 30 rather chose “Easy”. Unlike the case of traditional tools, from the results, participants did not think that AI-powered tools were anything but easy to use or user-friendly as 100% of the population sample rated the AI-powered tools as either Very Easy or Easy. This implies that the IIH-AILP model, which leverages AI-driven tools is comparatively more effective at being user-friendlier than approaches that adopt traditional tools. The descriptions for the respective ratings (very Easy, Easy, etc.) as seen in

Table 6, which were provided to participants to inform their choice of rating, give further insight to justify the IIH-AILP’s superiority in the “ease of use” metric.

Figure 15.

Participants’ Responses on Ease of Use of AI-powered and Traditional Graphic Design Tools.

Figure 15.

Participants’ Responses on Ease of Use of AI-powered and Traditional Graphic Design Tools.

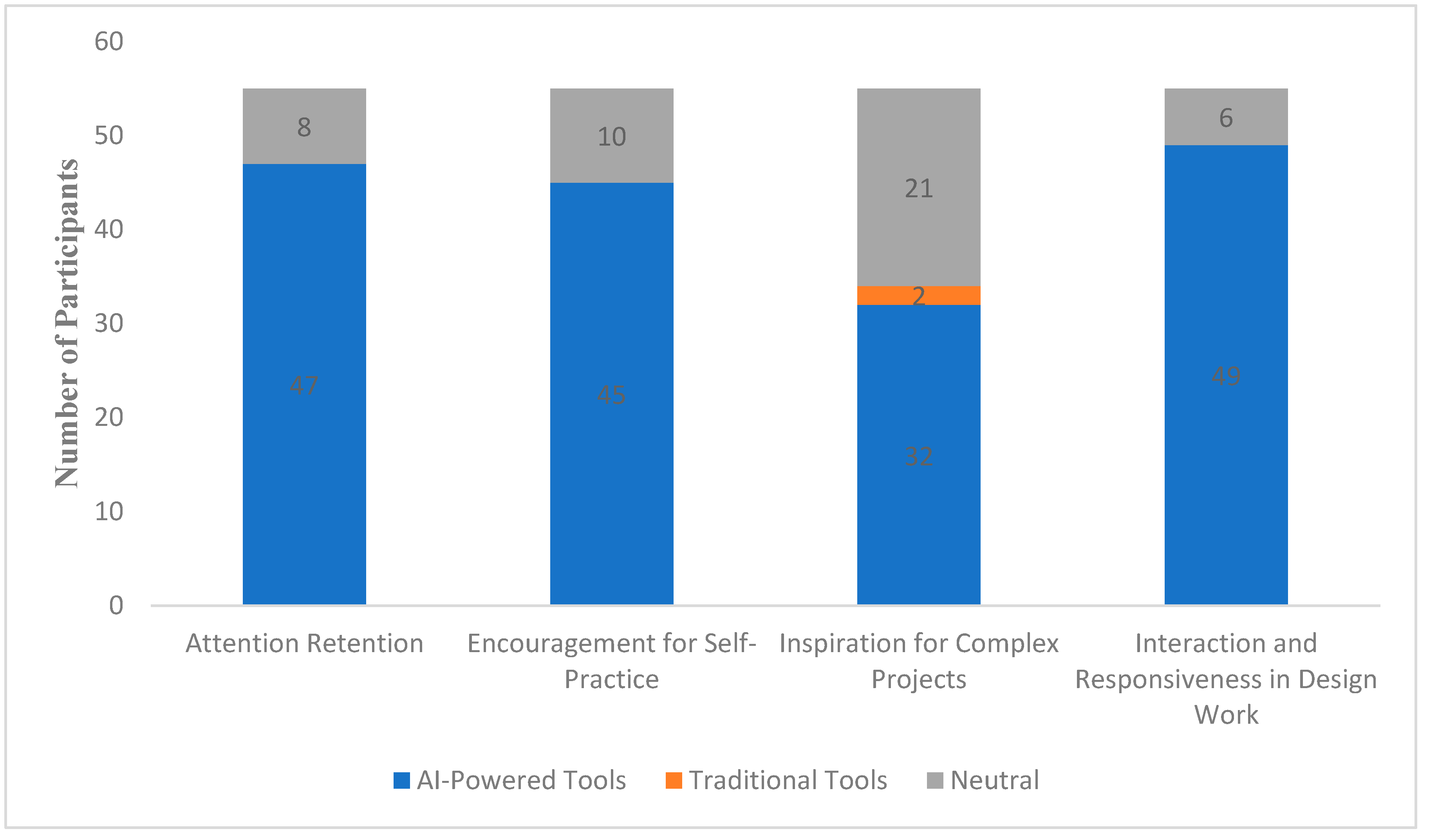

4.4.2. Participants’ Engagement and Motivation

Figure 16 presents results on the opinions of participants regarding which graphic design tools propel their engagement in the learning process and motivate them to take up self-projects after the IIH-AILP intervention was implemented. 47 out of the 55 learners, constituting 85.5%, opined that they had better attention retention when using AI-powered tools for graphic design. On encouragement for self-practice at their leisure, 81.8% of the learners indicated that AI-driven tools like Canva AI are better at boosting their incentive than traditional tools. Just 2 out of the 55 participants opted for traditional tools as their choice of inspiration for complex tasks, while 32 of them chose AI-driven tools. Finally, 89% of the sample population indicated that they had better interaction and responsiveness via the IIH-AILP model implementation than when they were engaged in traditional approaches. Overall, considering all four subcategories (attention retention, encouragement for self-practice, inspiration for complex projects, and responsiveness in design work), it can be deduced that an average of 78.6% of the participants affirmed the IIH-AILP model’s superiority over traditional tools, regarding the “Participants’ Engagement and Motivation” metric.

5. Summary & Conclusion

This study emphasizes the limitations faced by beginner learners regarding the acquisition of graphic design skills while using traditional tools like Adobe Photoshop and CorelDRAW. These tools are characterized by advanced features that are usually suitable for individuals with a good level of prior technical expertise but are not friendly for beginners; an indication of a steep learning curve. More precisely, traditional graphic design tools or applications have sophisticated functionalities and complex interfaces that narrow accessibility to individuals with a good level of expertise. Furthermore, these resource-intensive traditional tools pose the tendency of being a disincentive for novices to want to engage in graphic design learning, hence the need for viable and cost-effective alternatives for boosting practical graphic design skills that can seamlessly accommodate learners with little to no graphic design experience. In this paper, we proposed the IIH-AILP, a pedagogical framework that leverages AI-powered platforms to reduce the complexity of the graphic design learning process for beginner learners. The framework is constituted of six key components; Skills Progression, Modular Learning Design, Feedback and Assessment Loop, Gamified Learning Environment, Accessibility and Prerequisite Minimization, and finally a Comparative Analysis component. This novel framework is designed to structurally enhance the practical design skills of beginner students by incorporating Artificial Intelligence (AI) as a scaffolding tool. The IIH-AILP framework leverages the guided automation and easy-to-understand interface features of AI-driven platforms to water down sophistication in graphic design learning. Results from the study indicate that the IIHP-AILP framework successfully boosted the graphic design skills of the intervention’s participants. This was specifically shown via enhancements in the participants’ design creativity, their time for task completion, and the general learning curve. Additionally, on the “Ease of Use” and “Engagement and Motivation” metrics, the proposed framework, by leveraging AI-driven platforms, was seen to have demonstrated superiority over traditional graphic design tools. Finally, while the paper provides a concrete pathway for creating accessibility in graphic design learning, future research could explore the integration of more diverse AI-powered tools into the IIH-AILP framework to cater to a wider range of graphic design tasks, including animation, 3D modeling, and augmented reality.

Funding

The authors did not receive support from any organization for the submitted work.

Data Availability Statements

The authors declare that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper.

Competing Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest related to this research. This work was conducted independently, and there were no external influences that could compromise the integrity of the study

Compliance with Ethical Standards

The authors declare that the research described in this paper has been conducted by all ethical standards and guidelines.

Informed Consent

All participants in this study provided their consent to participate in the research. Consent was obtained either directly through participant agreement or, in the case of minors, through their legal guardians. Participation was entirely voluntary, and participants were informed about the nature and scope of the study before registering. Data collection was conducted using Google Forms, where participants explicitly agreed to have their information used for research and system evaluation purposes. This study involved no sensitive personal information, and all collected data were anonymized and stored securely. The need for additional formal consent was waived by the approving ethics committee, as the research complied with institutional guidelines and ethical standards for minimal-risk studies.

References

- AAMUSTED. (2024, April 25). 73 Young Females Begin Training under Invest-In-Her Programme at AAMUSTED. Https://Aamusted.Edu.Gh/73-Young-Females-Begin-Training-under-Invest-in-Her-Programme-at-Aamusted/.

- Adarkwah, M. A. (2021). The power of assessment feedback in teaching and learning: a narrative review and synthesis of the literature. SN Social Sciences, 1(3), 75. [CrossRef]

- Atuweni, Y. M., & Mtende, M. (2024). AI-aided design studio: Enhancing graphic design and user interface with machine learning. I-Manager’s Journal on Artificial Intelligence & Machine Learning, 2(2), 10. [CrossRef]

- Baltes, S., & Diehl, S. (2018). Towards a theory of software development expertise. Proceedings of the 2018 26th ACM Joint Meeting on European Software Engineering Conference and Symposium on the Foundations of Software Engineering, 187–200. [CrossRef]

- Bhagya Prabhashini C, & M. Latha. (2024). Language Assessment Feedback Towards Pedagogical Conversational Agent. Sino-US English Teaching, 21(5). [CrossRef]

- Curcic, D. (2024). Enhancing Digital Drawing Proficiency: An Examination of Assignment Redesign and Instructional Approaches in Higher Education Contexts. International Journal of Technology in Education and Science, 8(4), 602–626. [CrossRef]

- de Campos, V., David, J. M. N., Ströele, V., & Braga, R. (2023). Supporting the recruitment of software development experts: aligning technical knowledge to an industry domain. Anais Do XVIII Simpósio Brasileiro de Sistemas Colaborativos (SBSC 2023), 183–192. [CrossRef]

- de Campos, V., David, J. M. N., Ströele, V., & Braga, R. (2024). Aligning technical knowledge to an industry domain in global software development: A systematic mapping. Journal of Software: Evolution and Process, 36(12). [CrossRef]

- Duong, K. H., & Nguyen, L. T. (2024). Technology and Graphic Design: Building a STEM Education Ecosystem for the Future. 2024 9th International STEM Education Conference (ISTEM-Ed), 1–4. [CrossRef]

- Fahmi Romisa, & Dewi Rosita. (2024). Rancang Bangun Media Pembelajaran Interaktif pada Mata Pelajaran Desain Grafis. JURNAL ILMIAH SAINS TEKNOLOGI DAN INFORMASI, 2(3), 18–24. [CrossRef]

- Glazunova, O. G., Parkhomenko, O. V., Korolchuk, V. I., & Voloshyna, T. V. (2022). BUILDING THE PROFESSIONAL COMPETENCE OF FUTURE PROGRAMMERS USING METHODS AND TOOLS OF FLEXIBLE DEVELOPMENT OF SOFTWARE APPLICATIONS. Information Technologies and Learning Tools, 89(3), 48–63. [CrossRef]

- Headleand, C., & James, D. (2024). Games Design Frameworks: A Novel Approach for Games Design Pedagogy. European Conference on Games Based Learning, 18(1), 426–431. [CrossRef]

- HORINCHOI, R., & POLYAKOV, S. (2023). PEDAGOGICAL APPROACHES TO THE DEVELOPMENT OF GRAPHIC CULTURE OF 8-9 GRADE STUDENTS IN TECHNOLOGY LESSONS. ТHE SOURCES OF PEDAGOGICAL SKILLS, 32, 44–52. [CrossRef]

- Kyrylashchuk, S., & Kolomiiets, A. (2024). Formation of graphic competence of future specialists in technical specialities by means of artificial intelligence. Health and Safety Pedagogy, 9(1), 50–56. [CrossRef]

- Li, X., Lam, S. W., Zhang, Y., & Chu, S. K. W. (2023). Pedagogical Models for Plagiarism-Free Learning in Academia (pp. 85–95). [CrossRef]

- Lits, M. O. (2024). Teaching International Law to Students: Traditional Teaching Methods and New Approaches. Legal Education and Science, 21–26. [CrossRef]

- M. Fakhri Sholahuddin, & Tata Sutabri. (2024). Analisis Efektifitas UI/UX Design Software Pengolah Gambar Menggunakan Metode Design Thingking terhadap Kenyamanan Pengguna dalam Industry Animasi. Router : Jurnal Teknik Informatika Dan Terapan, 2(4), 66–72. [CrossRef]

- Maksymchuk, A., Shvets, O., Shtainer, T., Petrova, I., Kravchenko, N., & Abramova, O. (2024). Developing Art and Graphic Skills among Future Designers: An Integrative Principle and A Methodical Model. Revista Romaneasca Pentru Educatie Multidimensionala, 16(2), 105–117. [CrossRef]

- Materne, A. (2024). „Grafika komputerowa” – nauczyciel i uczeń w cyfrowym świecie obrazów. Notatki pedagogiczne. Studia Edukacyjne, 70, 93–109. [CrossRef]

- Mayor-Peña, F. C. Y., Barrera-Animas, A. Y., Escobar-Castillejos, D., Noguez, J., & Escobar-Castillejos, D. (2024). Designing a gamified approach for digital design education aligned with Education 4.0. Frontiers in Education, 9. [CrossRef]

- Muji, S., Svensson, E., & Faraon, M. (2023). Engaging With Artificial Intelligence in Graphic Design Education. 2023 5th International Workshop on Artificial Intelligence and Education (WAIE), 31–37. [CrossRef]

- Niu, Y., & Guan, Z. (2024). Performance Improvement of Art Design Drawing Tools Based on Multi-Objective Optimization Algorithm. 2024 3rd International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Autonomous Robot Systems (AIARS), 630–636. [CrossRef]

- Nouraei, F., Siu, A., Rossi, R., & Lipka, N. (2024). Thinking Outside the Box: Non-Designer Perspectives and Recommendations for Template-Based Graphic Design Tools. Extended Abstracts of the CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Patel, B. C., Goel, N., & Deshmukh, K. (2021). Traditional Teaching Pedagogy (pp. 42–57). [CrossRef]

- Qu, M., Liu, Y., & Feng, Y. (2021). Artificial Intelligence Empowered Visual Communication Graphic Design. 2021 International Conference on Networking Systems of AI (INSAI), 50–53. [CrossRef]

- Rafiyev, R., Novruzova, M., Aghamaliyeva, Y., & Salehzadeh, G. (2024). Contemporary trends in graphic design. InterConf, 43(193), 570–574. [CrossRef]

- Ray, S., Ngomba, R. T., & Ahmed, S. I. (2022). The impact of assessment and feedback practice on the student learning experiences in higher education. Essays in Biochemistry, 66(1), 83–88. [CrossRef]

- Rui, L., & Yang, C. (2024). Promoting Effect of Art Design Competition on Teaching Reform of Visual Communication Design Specialty. International Journal of High Speed Electronics and Systems. [CrossRef]

- Salim, M. S., Saad, M. N., & Nor, B. M. (2021). Comparative Study of Low-Cost Tools to Create Effective Educational Infographics Content. 2021 11th IEEE International Conference on Control System, Computing and Engineering (ICCSCE), 23–28. [CrossRef]

- Shilkova, T. V., Yefimova, N. V., & Semenova, M. V. (2023). Methodological approaches to teaching biological disciplines in a pedagogical university. Samara Journal of Science, 12(3), 331–338. [CrossRef]

- Tahsin, M., & Azzahra, P. L. (2024). Penerapan Kecerdasan Buatan untuk Meningkatkan Pembelajaran Desain Logo dalam Industri Kreatif. Design Journal, 2(1), 23–32. [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y., Ciancia, M., Wang, Z., & Gao, Z. (2024). What’s Next? Exploring Utilization, Challenges, and Future Directions of AI-Generated Image Tools in Graphic Design. http://arxiv.org/abs/2406.13436.

- Tang, Y., Zhang, N., Ciancia, M., & Wang, Z. (2024). Exploring the Impact of AI-generated Image Tools on Professional and Non-professional Users in the Art and Design Fields. http://arxiv.org/abs/2406.10640.

- Tella, R. R., Agarwal, S., & Kondepu, K. (2024). Exploiting Open Source Tools for FPGA Design Flow. 2024 16th International Conference on COMmunication Systems & NETworkS (COMSNETS), 324–326. [CrossRef]

- The Impact of Artificial Intelligence on the Graphic Design Industry. (2023). Arts and Design Studies. [CrossRef]

- Torta, S., & Saalmuller, L. (2024). Adobe InDesign. De Gruyter. [CrossRef]

- Vasylyshyna, N. (2022). CONTEMPORARY ACTIVE ENGLISH LANGUAGE TEACHING METHODS: THEORETICAL REVIEW AND PRACTICAL ASSIGNMENTS. Modern Information Technologies and Innovation Methodologies of Education in Professional Training Methodology Theory Experience Problems, 184–191. [CrossRef]

- Wang, K., & Chen, Q. (2024). Analysis and Recommendations on Empowering Non-Art Background College Students to Generate Visual and Textual Content Using AIGC Tools. Curriculum Learning and Exploration, 2(3). [CrossRef]

- Yue, S. (2024). The Evolution of Pedagogical Theory: from Traditional to Modern Approaches and Their Impact on Student Engagement and Success. Journal of Education and Educational Research, 7(3), 226–230. [CrossRef]

- Zharov, V. K., Mardanov, A. P., & Okbayeva, N. U. (2022). ON THE ISSUE OF MODELING THE METHODOLOGY OF TEACHING DISCIPLINES IN PEDAGOGY. RSUH/RGGU Bulletin. Series Information Science. Information Security. Mathematics, 1, 120–136. [CrossRef]

Figure 2.

Academic Levels of Participants.

Figure 2.

Academic Levels of Participants.

Figure 3.

The Conceptual Framework of the IIH-AILP Model.

Figure 3.

The Conceptual Framework of the IIH-AILP Model.

Figure 4.

Script for Implementing Badges and Leaderboard (Lines 1-25).

Figure 4.

Script for Implementing Badges and Leaderboard (Lines 1-25).

Figure 5.

Script for Implementing Badges and Leaderboard (Lines 26-50).

Figure 5.

Script for Implementing Badges and Leaderboard (Lines 26-50).

Figure 6.

Script for Implementing Badges and Leaderboard (Lines 51-75).

Figure 6.

Script for Implementing Badges and Leaderboard (Lines 51-75).

Figure 8.

Learning Curve Averages of Participants.

Figure 8.

Learning Curve Averages of Participants.

Figure 9.

“Creating a personalized name tag or badge” task completion time.

Figure 9.

“Creating a personalized name tag or badge” task completion time.

Figure 10.

“Designing a simple event flyer (using a pre-made template)” task completion time.

Figure 10.

“Designing a simple event flyer (using a pre-made template)” task completion time.

Figure 11.

“Developing a business card (customized layout and colors)” task completion time.

Figure 11.

“Developing a business card (customized layout and colors)” task completion time.

Figure 12.

“Designing a social media post” task completion time.

Figure 12.

“Designing a social media post” task completion time.

Figure 13.

Designing an infographic (custom layout, icons, and visuals).

Figure 13.

Designing an infographic (custom layout, icons, and visuals).

Figure 14.

Creativity Output Averages of Participants.

Figure 14.

Creativity Output Averages of Participants.

Figure 16.

Participants’ responses on “Engagement and Motivation” of AI-powered and Traditional Graphic Design Tools.

Figure 16.

Participants’ responses on “Engagement and Motivation” of AI-powered and Traditional Graphic Design Tools.

Table 1.

Demography of Participants.

Table 1.

Demography of Participants.

| Beginner Level Details |

Number of Participants |

Percentage

(Approximated)

|

| Level |

Description |

Low |

Participants in this category have zero knowledge of any graphic design software. They require a comprehensive introduction to design concepts and basic functionalities of graphic design tools.

|

45 |

82% |

Intermediate |

Participants with minimal exposure to traditional graphic design tools. They somehow understand basic design principles but need guidance in navigating traditional tools. They have no exposure to AI-driven platforms.

|

8 |

14% |

High |

Similar to intermediate-level participants but with some casual exposure to AI-driven graphic design platforms.

|

2 |

4% |

| TOTAL |

55 |

100% |

Table 2.

Components of the IIH-ALP Model Framework.

Table 2.

Components of the IIH-ALP Model Framework.

Component

|

Weeks |

Mode of Execution |

Skills Progression Framework

|

Week 1-9 |

Sequential |

| Modular Learning Experience |

Week 1-9 |

Parallel with the Progression Framework |

| Feedback & Assessment Loop |

Weeks 1-12 |

Integrated into all components

|

| Gamified Learning Environment |

Weeks 2,4,5,6,8 &9 |

Integrated

|

| Accessibility & Prerequisite Minimization |

Week 1 & Continuous

|

Foundational & Integrated |

| Comparative Analysis |

Weeks 10-12 |

Sequential &Final Evaluation

|

Table 4.

Creativity Output Evaluation Rubric.

Table 4.

Creativity Output Evaluation Rubric.

| Criteria |

Excellent (4) |

Good (3) |

Fair (2) |

Poor (1)

|

Conceptual Depth

|

A unique interpretation and deep understanding of the set of instructions for the task.

|

A clear understanding of the set of instructions for the task. |

Basic interpretation of the set of instructions. |

Generic design that has no conceptual depth. |

Innovation

|

Introduced novel approaches to design. |

Demonstrated some creativity with common ideas.

|

The design is too simplistic and has little creativity. |

Design lacked creativity. |

Adaptability

|

Excellent integration of AI-generated feedback and suggestions along with personal touches.

|

An effective blend of AI suggestions with personal flair. |

Relied mainly on AI suggestions with little personal touches. |

Depends entirely on AI suggestions. |

Quality of Output

|

A flawless output with no errors in spacing, alignment, or typography. |

High-quality output with few inconsistencies or minor errors. |

Obvious errors that diminish the overall quality of the work. |

Too many technical flaws in the design

. |

Visual Appeal

|

Excellent use of layouts, colors, and fonts. |

Minor design flaws but aesthetically pleasing output. |

Moderately pleasing design with some visual element flaws. |

The design lacks aesthetic appeal with a poor choice of layouts, colors, and fonts. |

Table 5.

Creativity Output Evaluation Rubric.

Table 5.

Creativity Output Evaluation Rubric.

| Task |

Difficulty Level

|

Expected Time Completion Time |

| Creating a personalized name tag or badge |

Basic |

15-20 minutes

|

Designing a simple event flyer (using a pre-made template)

|

Basic |

30 minutes |

Developing a business card (customized layout and colors)

|

Intermediate |

40 minutes |

| Designing a social media post |

Intermediate |

35 minutes

|

| Designing an infographic (custom layout, icons, and visuals) |

Advanced |

60 minutes |

Table 6.

Interpretation of participant ratings for both AI-powered tools and traditional tools.

Table 6.

Interpretation of participant ratings for both AI-powered tools and traditional tools.

| |

Description |

| Very Easy |

Straightforward tools and interface for navigation. Consistently produced results with a few manual corrections. Minimal to no assistance is required for tasks to be completed on time. Easy accessibility functionalities that require minimal effort of use. |

| Easy |

Smooth and manageable process generally, with minimal challenges. Simple to use overall, with a few challenges in understanding some features. Tasks are completed with negligible delays. Minimal reliance on external resources in addressing frequent challenges. |

| Moderate |

Due to some features’ sophistication, tasks take longer than expected. Requires reliance on assistance to effectively complete tasks. Some workflows are unclear and hence require a good amount of effort is required in using the tool. Requires significant adjustments to produce expected results. |

| Difficult |

Heavy dependence on external assistance to address frequent challenges. Tasks require more time to be used to complete than expected. Tools appear insufficient for needs and/or processes seem too complex. Interface is not user-friendly. |

| Very Difficult |

The entire experience is tedious and tools are difficult to use. Little clarity in features and workflows that require heavy dependence on external assistance. Tasks are completed with very significant delays. Little to no motivation to keep using the tool. |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).