1. Introduction

The rapid advancement of artificial intelligence (AI) is fundamentally reshaping how knowledge is generated, disseminated, and applied in real-world problem-solving. AI technologies are redefining cognitive processes—transforming how humans think, learn, and engage with information. As the pace of knowledge creation accelerates exponentially, the “half-life of knowledge” shortens dramatically [1], resulting in an environment where learners can no longer rely solely on static, preexisting knowledge to solve emerging and complex problems.

This paradigm shift poses a critical challenge for education: how to determine not only what content should be taught but also how learning should be structured to prepare learners for an unpredictable future. Traditional instructional theories—such as behaviorism, cognitivism, and constructivism—have conceptualized learning primarily as the internalization of knowledge transmitted in structured formats. However, these models often fall short in equipping learners with the adaptive, real-world problem-solving skills demanded in AI-driven contexts.

In response, emerging frameworks such as connectivism emphasize that knowledge is not confined to the human brain but distributed across networks—including other people, digital resources, and AI systems [2,3]. Learning, in this view, is the capacity to access, connect, and navigate these networks effectively. This epistemological shift is further reinforced by extended mind theory, which posits those cognitive processes—such as memory, reasoning, and decision-making—can be meaningfully distributed across external tools and environments [4,5]

These shifts call for a new focus in education: not merely the acquisition of competency, which implies performance in familiar tasks, but the development of capability—the potential to adapt, create, and thrive amid uncertainty [6,7,8]. In an AI-mediated landscape, learners must engage in continuous learning, flexible thinking, and meta-cognitive reflection.

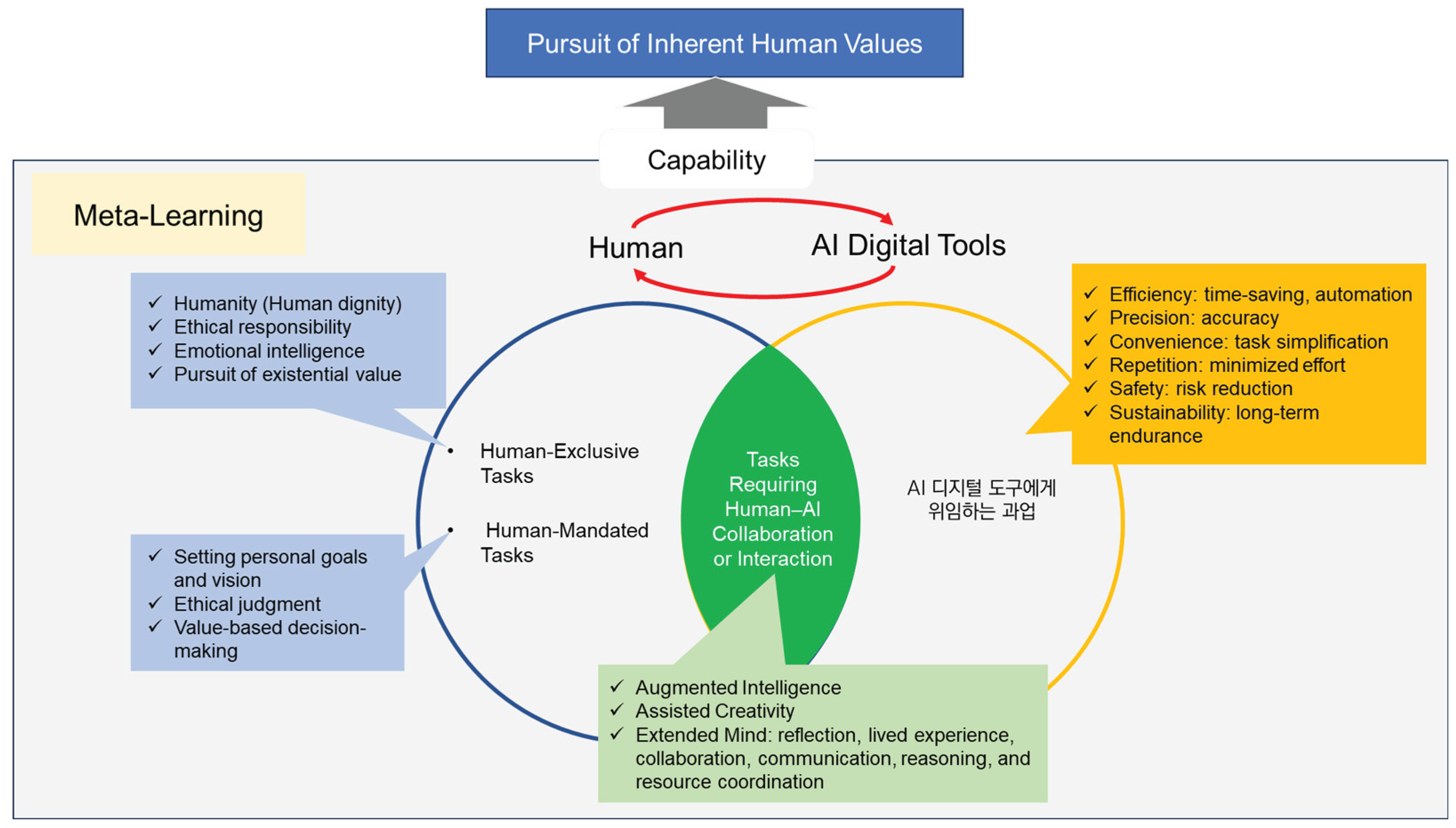

Moreover, AI should not be viewed solely as a tool for automation or information delivery, but rather as a partner in augmented intelligence—a human–AI collaborative model in which AI supports lower-order functions (e.g., pattern recognition, data processing) and humans contribute higher-order judgment, ethical reasoning, and creativity [9]. AI’s potential as a co-creative partner further enhances human originality, enabling learners to escape conventional thought patterns and reframe problems through novel perspectives [10].

Despite growing theoretical consensus on these developments, there remains a lack of integrative instructional design models that translate these ideas into actionable educational practice. In response, this study proposes a model called Intelligent Problem-Solving Learning (IPSL)—a capability-based instructional framework that places human–AI collaboration at its core.

IPSL aims to cultivate future-ready learners by guiding them to solve complex, unpredictable problems while preserving human agency and values. This study develops and validates a conceptual model and set of instructional design principles for IPSL using a design and development research (DDR) methodology. It seeks to contribute to a new educational paradigm that balances technological innovation with human-centered learning in the age of artificial intelligence.

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Paradigm Shift in the Concepts of Learning and Capability

The advent of artificial intelligence (AI) has ushered in an era of exponential knowledge growth—often referred to as a “knowledge explosion.” As the total volume of human knowledge doubles every few years, previously acquired information quickly becomes obsolete, a phenomenon known as the “half-life of knowledge” [1]. In this dynamic environment, traditional school-based education, which prioritizes content delivery and knowledge transmission, is increasingly showing its limitations.

Classical learning theories—behaviorism, cognitivism, and constructivism—have generally emphasized knowledge accumulation within the learner’s mind through content organized and delivered by teachers. However, in the AI era, where learners must continuously adapt to novel information landscapes, such inward-focused models are becoming insufficient. As a response, connectivism has emerged as an alternative paradigm [2,3].

Connectivism views knowledge as a distributed network, wherein learning involves building and navigating meaningful connections among various “nodes”—which may include people, databases, digital tools, or AI systems. Learning, in this sense, is not about storing facts in one’s brain, but about accessing, synthesizing, and applying knowledge across a dynamic system. According to AlDahdouh et al. [11], the act of linking, reorganizing, and innovating across these nodes constitutes the essence of learning in digital environments.

AI technologies serve as powerful external nodes that expand learners’ knowledge networks. In a world of rapidly evolving challenges and disappearing job predictability, lifelong learning and relearning are no longer optional. Relying on a fixed body of knowledge is no longer viable. In this context, connectivism offers a compelling theoretical foundation for cultivating agile and self-directed learners.

Siemens [2] emphasized that modern learners must develop not only the ability to “know what” or “know how,” but more importantly, the ability to “know where” and “know who”—that is, the ability to locate relevant information and expertise across distributed networks. In such a view, the flow of knowledge becomes more valuable than its content, and learning capacity becomes more crucial than static mastery.

This epistemological shift also calls into question the sufficiency of competency-based education, which typically focuses on pre-specified knowledge, skills, and attitudes for known tasks. Although valuable, competencies often fall short when applied to unfamiliar or rapidly changing situations [12]. In contrast, capability encompasses the learner’s justified confidence to act effectively even in unpredictable or novel contexts [6].

Capability-based education emphasizes adaptability, creativity, and the ability to generate new knowledge—rather than merely applying existing content. It fosters self-directed learning, situational responsiveness, and transferability of skills. In connectivist terms, capability aligns with the learner’s ability to form new connections, identify patterns, and engage in meta-cognitive inquiry. As such, capability—not just competency—must become the central aim of education in the AI era.

2.2. Human–AI Collaboration and Augmented Intelligence

In light of AI’s rapid progress, the focus of education is shifting from isolated human problem-solving to collaborative intelligence between humans and machines. Concepts such as augmented intelligence, intelligence amplification, and co-creativity are gaining prominence in educational discourse.

Augmented intelligence refers to the enhancement of human cognitive abilities through synergistic collaboration with AI. Rather than replacing human tasks, AI complements them by processing large-scale data, recognizing patterns, and generating alternatives. Dede et al. [9] argue that the combined performance of humans and AI exceeds the sum of their individual contributions, representing a new cognitive strategy rooted in cooperation—not substitution.

While AI excels at processing speed, accuracy, and data scalability, humans provide irreplaceable higher-order capabilities: moral reasoning, creative synthesis, empathy, and ethical decision-making [13]. Augmented intelligence thus proposes a division of cognitive labor, wherein machines support the analytic and procedural aspects, while humans retain judgment, interpretation, and accountability.

This division extends to creativity. Assisted creativity frames AI not as a substitute for human imagination but as a partner that stimulates novel thinking [10]. For instance, AI can quickly generate numerous idea variants, freeing learners from conventional constraints and encouraging exploration of innovative alternatives. Such synergy enhances human originality by offering unexpected perspectives and reducing cognitive fixation.

The Extended Mind Theory [4,5] provides the philosophical foundation for this collaborative model. It posits those cognitive processes—such as memory, learning, and problem-solving—can extend into external tools and environments. From this standpoint, AI serves not merely as a tool, but as part of a distributed cognitive system. Recording ideas with a smartphone or searching for patterns using an AI assistant are examples of how cognition now spans beyond the brain.

However, extended cognition is not about blind reliance. It demands metacognitive awareness—knowing how to manage and evaluate information across internal and external resources. Students must therefore be trained not only to use AI but to use it wisely: knowing when to delegate, how to interpret results, and where to retain human control. The theory offers a critical foundation for designing instructional models that support human–AI co-thinking.

Ultimately, the abilities required for productive human–AI collaboration—augmented intelligence, ethical discernment, meta-cognition, and collaborative creativity—are emerging as core competencies for the future. As automation redefines labor markets, most experts agree that AI will not fully replace human roles but will reconfigure them through intelligent partnerships [9,14]. Future education must prepare learners to thrive in this hybrid environment.

3. Methods

This study employed a Design and Development Research (DDR)[15] methodology to construct and validate the conceptual model and instructional design principles of Intelligent Problem-Solving Learning (IPSL). The research was conducted in three sequential stages: (1) model development through literature review, (2) expert validation, and (3) model refinement based on feedback.

3.1. Stage 1: Model Development through Literature Review

In the first stage, a comprehensive literature review was conducted to conceptualize IPSL and derive corresponding instructional design principles. The review focused on key themes such as educational transformation in the AI era, human–AI interaction, ethical dimensions of AI use, meta-learning strategies, and sustainability-oriented education.

Academic journal articles, books, and policy reports published between 2018 and 2024 were systematically collected from major databases including Web of Science, Scopus, ERIC, and ScienceDirect. Key search terms included: intelligent problem solving, AI in education, human–AI collaboration, meta-learning, sustainable capability development, and instructional design in AI-supported environments.

The literature screening process followed PRISMA guidelines to ensure transparency and reproducibility. Inclusion criteria were:

Studies addressing AI-based or intelligent problem-solving in educational settings,

Studies proposing or evaluating instructional design strategies or models,

Studies related to sustainability, digital competence, or ethical learning.

Studies lacking theoretical grounding, empirical evidence, or educational relevance were excluded. Through thematic synthesis, three core domains essential to intelligent problem-solving were identified:

Fostering sustainable human values (e.g., ethics, emotional intelligence, life purpose),

Structuring task execution through differentiated roles (human, AI-delegable, human–AI collaborative),

Promoting adaptive thinking via meta-learning strategies.

These domains formed the basis for developing a conceptual model of IPSL, accompanied by a preliminary set of instructional design principles applicable to AI-supported educational contexts.

3.2. Stage 2: Expert Validation

The expert panel included eight professionals with extensive backgrounds in instructional design, educational psychology, AI in education, and policy innovation. All experts held doctoral degrees and had over ten years of experience in relevant domains.

3.2.1. Expert Panel Composition

The expert panel included eight professionals with extensive backgrounds in instructional design, educational psychology, AI in education, and policy innovation. All experts held doctoral degrees and had over ten years of experience in relevant domains.

Selection criteria included:

Academic or practical expertise in instructional design, digital education, or AI-enhanced learning,

Publications in peer-reviewed (SCIE/SSCI) journals or participation in national-level projects,

Experience with curriculum evaluation or educational policy development.

The panel consisted of:,

Three university professors in instructional technology and future education,

Two researchers in AI-supported learning and digital innovation,

Two teacher educators with experience in pre-service training,

One policy expert specializing in sustainability and education.

Table 1.

Expert panel composition and profile.

Table 1.

Expert panel composition and profile.

| No |

Expert Code |

Affiliation |

Area of

Expertise |

Major Experience and Role |

Role

Category |

| 1 |

E1 |

XX University, Department of Education |

Instructional Design, Educational Technology |

Ph.D. in Educational Technology; 15+ years university teaching; AI-based instructional design research |

Instructional Design Expert |

| 2 |

E2 |

XX University, Future Education Research Institute |

Future Education, AI-based Instructional Design |

National advisor on digital education policy; multiple SSCI publications |

Future Education Expert |

| 3 |

E3 |

△△ Cyber University, Dept. of AI Education |

AI-based Learning Environment Design |

Participated in AI tutoring system development; Lead researcher on MOE R&D project |

AI-Based Learning Expert |

| 4 |

E4 |

XX National University of Education |

Pre-service Teacher Education |

Led teacher training programs; planned in-service training for schoolteachers |

Teacher Education Expert |

| 5 |

E5 |

□□ Educational Policy Research Institute |

Sustainability in Educational Policy |

Conducted SDG4-based education policy research |

Sustainability Policy Expert |

| 6 |

E6 |

OO University, Department of Educational Psychology |

Metacognition, Self-Regulated Learning |

Led development of learner cognitive and affective models |

Educational Psychology Expert |

| 7 |

E7 |

Private AI Education Company |

AI Content Development and UX Design |

Field expert in AI-based educational content and UX prototyping |

EdTech Industry Expert |

| 8 |

E8 |

△△ National University, Department of Education |

Curriculum and Assessment Design |

Participated in national project for AI-based performance assessment system |

Assessment Design Expert |

3.2.2. Review Process and Evaluation Criteria

In the first round of validation, experts were provided with the initial conceptual model of IPSL, including a visual diagram, detailed descriptions, and six preliminary instructional design principles derived from the literature. Each item was evaluated using a 4-point Likert scale (1 = Not valid at all; 4 = Highly valid). Alongside numerical ratings, participants were invited to offer qualitative feedback to guide subsequent revisions and refinements of the framework.

The conceptual model was assessed according to six evaluative criteria:

Conceptual clarity: Are the core concepts clearly defined and easily understandable?

Theoretical validity: Is the model grounded in established educational theory and conceptually coherent?

Internal coherence: Do the components demonstrate logical consistency and alignment with one another?

Comprehensiveness: Does the model encompass all essential elements required to support the development of human values?

Visual communicability: Does the diagram effectively illustrate the relationships among components and convey the overarching message?

Innovativeness: Does the model introduce novel or creative perspectives appropriate for AI-integrated educational contexts?

These criteria were developed with reference to prior research on instructional design model evaluation [16,17,18,19,20].

The instructional design principles were reviewed using five distinct criteria:

Validity: Is the principle appropriate and contextually relevant to IPSL?

Clarity: Are the statements expressed in clear, concise, and unambiguous terms?

Usefulness: Can the principle be practically applied in instructional settings?

Universality: Is the principle adaptable across various educational levels and contexts?

Comprehensibility: Is the principle easily understood by both instructors and learners?

These evaluative dimensions were adapted from existing frameworks for instructional design assessment [21,22,23].

Two quantitative indices were employed to analyze the evaluation results:

Content Validity Index (CVI): Calculated as the proportion of experts rating an item as either 3 or 4, divided by the total number of reviewers. A CVI of 0.80 or above was considered acceptable [24].

Inter-Rater Agreement (IRA): Used to assess the level of consistency among expert ratings. An IRA value of 0.75 or higher indicated satisfactory agreement [25]. In this study, consensus was defined as six or more experts assigning the same score to a given item.

In addition to quantitative measures, extensive qualitative feedback was solicited to inform the revision process. Particular attention was given to items that yielded low inter-rater agreement or borderline CVI values, with expert suggestions actively encouraged to enhance clarity, alignment, and applicability.

Following the feedback obtained during the first round of expert review, both the conceptual model of IPSL and the associated instructional design principles were systematically revised to enhance clarity, structural coherence, and theoretical alignment. The revised materials were then re-evaluated by the same panel of experts using the identical criteria and procedures established in Round 1.

During this second evaluation phase, both the Content Validity Index (CVI) and Inter-Rater Agreement (IRA) were recalculated to assess whether the revisions had improved expert consensus. Items that failed to achieve the threshold CVI value of 0.80 or exhibited low inter-rater reliability were flagged for potential modification or further refinement.

In addition to quantitative reassessment, qualitative feedback was actively solicited and analyzed to supplement interpretation of the results. Expert suggestions were particularly instrumental in identifying remaining ambiguities or inconsistencies. Through this iterative process, the IPSL conceptual model and its instructional design principles were finalized with significantly improved clarity, theoretical consistency, and consensus among experts.

4. Expert Review Results

To validate the conceptual model and instructional design principles of Intelligent Problem-Solving Learning (IPSL), two rounds of expert review were conducted with a panel of eight specialists. The results are detailed below

4.1. Validation of the IPSL Conceptual Model

Table 2.

Summary of Expert Validation Results for the IPSL Conceptual Model.

Table 2.

Summary of Expert Validation Results for the IPSL Conceptual Model.

| Domain |

Round 1 Experts (N = 8) |

Round 2 Experts (N = 8) |

| Mean |

CVI |

IRA |

Mean |

CVI |

IRA |

| Conceptual Clarity |

3.13 |

0.88 |

0.63 |

3.75 |

1.00 |

0.75 |

Theoretical

Validity |

4.00 |

1.00 |

1.00 |

4.00 |

1.00 |

1.00 |

Coherence Among

Components |

2.88 |

0.75 |

0.63 |

3.25 |

1.00 |

0.75 |

| Comprehensiveness |

3.50 |

0.88 |

0.63 |

4.00 |

1.00 |

1.00 |

| Visual Communicability |

3.25 |

1.00 |

0.75 |

4.00 |

1.00 |

1.00 |

| Innovativeness |

3.50 |

0.88 |

0.63 |

3.88 |

1.00 |

0.88 |

| Overall Average |

3.38 |

0.90 |

0.71 |

3.81 |

1.00 |

0.90 |

In the first round of expert review, the evaluation of the IPSL conceptual model yielded mean scores ranging from M = 2.88 to M = 4.00, with corresponding Content Validity Index (CVI) values between 0.75 and 1.00, and Inter-Rater Agreement (IRA) ranging from 0.63 to 1.00. Among the six evaluation criteria, theoretical validity (M = 4.00, CVI = 1.00, IRA = 1.00) and visual communicability (M = 3.25, CVI = 1.00, IRA = 0.75) received particularly strong ratings. Conversely, relatively lower IRA scores were recorded for coherence among components (M = 2.88, CVI = 0.75, IRA = 0.63) and conceptual clarity (M = 3.13, CVI = 0.88, IRA = 0.63), suggesting variations in expert interpretation and the need for further refinement.

In response, revisions were made to the model’s structure, terminology, and visual presentation. In the second round, all evaluation criteria achieved mean scores exceeding 3.25, while CVI values reached 1.00 across all items, indicating complete agreement on content validity. IRA scores also improved substantially, with all items meeting or exceeding the threshold of 0.75, including theoretical validity (IRA = 1.00) and innovativeness (IRA = 0.88).

A comparison of overall scores between the two rounds demonstrates significant improvement: the total average score rose from M = 3.38 (CVI = 0.90, IRA = 0.71) in Round 1 to M = 3.81 (CVI = 1.00, IRA = 0.90) in Round 2. These results affirm that iterative refinement based on expert feedback enhanced the model’s validity, reliability, and interpretability—particularly in the domains of conceptual clarity, theoretical alignment, structural coherence, practical relevance, and innovation.

In addition to quantitative results, qualitative feedback from experts highlighted several areas for improvement across the six evaluation domains.

First, in terms of conceptual clarity, experts pointed out that key constructs such as existential value, capability, and meta-learning were initially presented in ways that were too abstract or insufficiently defined. In response, the definitions of these core terms were refined, and consistency between visual and textual terminology was improved. These adjustments contributed to more favorable evaluations in the second round, particularly regarding clarity and communication.

Second, with regard to theoretical validity, while the use of foundational theories such as connectivism and extended mind theory was deemed appropriate, experts noted that the linkages between these theoretical underpinnings and the model’s components were not sufficiently explicit. To address this, the relationships between theory and structure were clearly mapped and conceptually reinforced, which led to improved consensus in the follow-up review.

Third, concerning coherence among components, experts acknowledged the model’s attempt to differentiate between human-exclusive tasks, human–AI collaboration, and AI-delegable tasks. However, some ambiguity remained in how these categories were demarcated. The revised model addressed this issue by explicitly defining the boundaries and roles within each task category, which in turn strengthened structural consistency.

Fourth, in relation to comprehensiveness, while the initial model incorporated meta-learning and human–AI collaboration, several experts expressed concern that it lacked sufficient attention to emotional and ethical dimensions of human experience. In response, human-centered values were more deeply embedded within the model, resulting in broader acknowledgment of its humanistic orientation during the second round.

Fifth, regarding visual communicability, although the overall layout was viewed as intuitive, some confusion arose due to unclear boundaries between model components. To enhance visual readability, revisions included refinements to color contrast and the addition of explanatory text boxes. These enhancements were well received and contributed to stronger agreement in the second review.

Sixth and finally, in the area of innovativeness, concepts such as existential value pursuit, role-based task distribution, and AI-assisted creativity were recognized as novel and meaningful. However, several experts noted that the model’s distinction from existing instructional design frameworks was not fully articulated. Accordingly, the introduction and conceptual rationale were revised to more clearly position IPSL as a unique contribution to AI-integrated educational design. These changes were positively received and helped solidify consensus on the model’s innovative character.

Taken together, the results of both rounds of expert review—quantitative and qualitative—demonstrate that the IPSL conceptual model achieved high levels of reliability, validity, and educational relevance. Through iterative refinement, the model evolved into a theoretically grounded and practically applicable framework suitable for designing future-oriented, AI-enhanced learning environments.

4.2. Expert Validation of Instructional Design Principles

In the first round of expert evaluation, the instructional design principles of the IPSL framework demonstrated a clear need for revision. The mean scores across the five evaluation criteria ranged from 2.38 to 3.00, with Content Validity Index (CVI) values falling below the generally accepted threshold of 0.80. Particularly low ratings were observed in the areas of clarity (M = 2.38, CVI = 0.38) and comprehensibility (M = 2.38, CVI = 0.38), largely due to concerns that the language used was overly abstract and the sentence structures unnecessarily complex.

Although the remaining criteria—validity (M = 2.75), usefulness (M = 3.00), and universality (M = 2.63)—met the minimum average score requirements, their CVI values also fell short, indicating insufficient expert consensus. Furthermore, the Inter-Rater Agreement (IRA) was calculated as 0.00, revealing a complete lack of consistency in expert ratings across all criteria.

To address these issues, the instructional design principles were extensively revised to enhance clarity, readability, theoretical alignment, and practical applicability. In the second round of expert review, all criteria received mean scores above 3.00, with CVI values reaching 1.00 for every item—indicating unanimous agreement among reviewers. Notably, both validity and comprehensibility achieved perfect scores (M = 4.00, CVI = 1.00), reflecting significant improvement. The recalculated IRA also reached 1.00, confirming a high level of consistency and consensus across the panel. These results represent a substantial improvement over the first round (IRA = 0.00; CVI = 0.38–0.63), affirming the reliability and educational soundness of the final version.

Table 3.

Summary of Expert Validation Results for IPSL Design Principles.

Table 3.

Summary of Expert Validation Results for IPSL Design Principles.

| Domain |

Round 1 Experts (N = 8) |

Round 2 Experts (N = 8) |

| Mean |

CVI |

IRA |

Mean |

CVI |

IRA |

| Validity |

2.75 |

0.63 |

0.50 |

4.00 |

1.00 |

1.00 |

| Clarity |

2.38 |

0.38 |

0.38 |

3.13 |

1.00 |

0.88 |

| Usefulness |

3.00 |

0.63 |

0.50 |

3.75 |

1.00 |

0.75 |

| Universality |

2.63 |

0.63 |

0.63 |

3.00 |

1.00 |

1.00 |

| Comprehensibility |

2.38 |

0.38 |

0.38 |

4.00 |

1.00 |

1.00 |

| Overall Average |

2.63 |

0.53 |

0.38 |

3.58 |

1.00 |

0.93 |

Based on expert feedback, five major revisions were made, corresponding to the five thematic categories of the IPSL framework.

First, in the category of Pursuit of Inherent Human Values, experts noted that the concepts of existential value and identity were overly abstract and lacked a clear hierarchical structure. In response, these were consolidated into a single, coherent principle. Additional revisions addressed emotional competence by integrating references to psychological well-being and social connectedness. Furthermore, statements regarding learner agency were streamlined to enhance clarity and focus. These changes were positively received for improving conceptual coherence and practical relevance.

Second, in the category of Value Pursuit Strategies (Meta-Learning), experts highlighted insufficient distinction between goal setting and strategy development. The revised principles addressed this concern by reorganizing the content into a sequential structure that reflected the logic of self-regulated learning. Furthermore, the newly integrated concept of meta-emotion, proposed during the first review, emphasized the importance of emotional self-awareness and regulation—further reinforcing the comprehensive nature of meta-learning.

Third, in the area of Complex Problem Solving in Unpredictable Situations, the original principles were considered verbose and lacking conceptual focus. The revised version introduced complex thinking as a central theme and explicitly emphasized the integration of disciplinary knowledge, real-world context, and AI-based tools in problem-solving. The inclusion of a principle that addressed learners’ ability to resolve ethical conflicts and dilemmas was regarded as a significant enhancement, adding depth to the model’s alignment with socially situated learning.

Fourth, the category of Future-Oriented Capability was restructured to emphasize the development of learnability and the strategic use of AI as a “second brain.” Rather than listing conventional types of knowledge transfer, the revised principles promoted transdisciplinary thinking to encourage learners to synthesize and apply knowledge across disciplinary and contextual boundaries. These modifications were well aligned with the educational goal of cultivating adaptive and future-ready learners.

Fifth, in the category of Human–AI Collaborative Structures, the task roles of humans and AI were more clearly delineated into three categories: tasks performed exclusively by humans, tasks requiring human–AI collaboration, and tasks that could be delegated to AI. Specific examples of AI-delegable tasks—such as repetitive data processing or risk-intensive operations—were added for greater clarity. Particularly well received was the principle encouraging learners to engage AI as a critical peer, which was praised for capturing the model’s aim of fostering autonomous and reflective thinking within AI-mediated learning environments.

In summary, the initial development of the instructional design principles was based on an extensive literature review and theoretical framework, resulting in an original set of 39 principles distributed across three main categories and eight subcategories (e.g., personal values, community values, meta-learning, complex thinking). Through two iterative rounds of expert review, this initial set was refined and consolidated into a final set of 18 validated instructional principles, maintaining the original categorical structure while eliminating redundancy and improving clarity, relevance, and applicability.

Table 4.

Final Instructional Design Principles for IPSL.

Table 4.

Final Instructional Design Principles for IPSL.

| Major Category |

Subcategory |

Final Instructional Design Principles |

| Pursuit of Inherent Human Values |

Personal Values |

● Guide learners to explore their existential value and identity, and to establish life goals and vision accordingly.

● Foster learners’ emotional competence to maintain psychological well-being and build healthy social relationships.

● Encourage learners to develop agency and ownership in their learning. |

| Community Values |

● Guide learners to internalize ethical values in society and continuously reflect on and update them.

● Promote learners’ recognition and practice of human dignity as the highest value.

● Encourage learners to pursue public values in communities with a sense of responsibility. |

Value Pursuit

Strategies |

Meta-Learning |

● Support learners in setting meaningful personal learning goals.

● Help learners develop and continuously revise their own learning strategies.

● Promote learners’ development of meta-emotional abilities (e.g., emotional self-awareness and regulation). |

| |

Complex Problem

Solving |

● Encourage learners to think complexly by considering diverse variables and factors in the problem-solving process.

● Enable learners to solve fusion problems integrating subject matter, life, and AI.

● Empower learners to resolve various conflicts and dilemmas during problem-solving. |

| |

Future-Oriented Capability |

● Enhance learners’ ability to learn (learnability).

● Promote learners’ use of AI as a “Second Brain” to expand cognitive capabilities.

● Strengthen learners’ knowledge transfer by encouraging transdisciplinary thinking. |

| Human–AI Collaborative Structure |

Human-Exclusive Tasks |

● Support learners in strategically dividing tasks between humans and AI.

● Guide learners to use AI ethically and recognize regulatory principles.

● Ensure that learners make all final decisions based on personal and community values. |

| |

Human–AI Collaborative Tasks |

● Encourage learners to collaborate with AI to redefine problems from multiple perspectives.

● Support learners in reconstructing meaning through co-creativity with AI.

● Enable learners to use AI as a critical peer to shift and expand their thinking. |

| |

AI-Delegated Tasks |

● Allow learners to delegate repetitive or efficiency-driven tasks to AI.

● Guide learners to assign tasks involving complex or large-scale data processing to AI. |

| |

|

● Encourage learners to delegate risky or sustainability-required tasks to AI. |

5. Conceptual Model and Design Principles of IPSL

Grounded in theoretical exploration and expert validation, Intelligent Problem-Solving Learning (IPSL) is defined as a strategic learning model for fostering future-oriented capabilities in learners—particularly their potential to adapt to and resolve complex, unpredictable problems in AI-mediated environments. The model positions the pursuit of inherent human values as its foundational educational aim and emphasizes the differentiated roles of humans and artificial intelligence in the learning process.

Through meta-learning, learners are guided to navigate and engage with three distinct categories of tasks:

those that must be performed exclusively by humans,

those that require collaboration between humans and AI, and

those that can be effectively delegated to AI systems.

By determining how best to approach each task type, learners cultivate cognitive flexibility, ethical discernment, and adaptive thinking—core attributes of sustainable, future-ready education.

The IPSL conceptual model, constructed on this definition, is illustrated in the figure below. It visualizes the interplay among human–AI task roles, meta-learning strategies, and capability development within a collaborative learning ecosystem.

Figure 1.

Conceptual Model of Intelligent Problem-Solving Learning.

Figure 1.

Conceptual Model of Intelligent Problem-Solving Learning.

5.1. Pursuit of Inherent Human Values

In the AI era, the ultimate goal of future-oriented education is to support learners in recognizing and pursuing their existential value as human beings. The rapid advancement of AI technologies—now capable of surpassing human performance in traditionally human-centric domains such as creativity—poses a profound challenge to the meaning and uniqueness of human existence [15]. Rubin [27] cautioned that the growing potential for AI to exceed human capabilities could fundamentally disrupt conceptions of identity and intrinsic value, calling into question what it means to be human in an increasingly automated world.

From this perspective, a key educational imperative is to cultivate learner capabilities that cannot be replicated or replaced by AI. The IPSL model responds to this need by placing existential value at the core of its design, and guiding learners to articulate a life purpose aligned with this value. Accordingly, the IPSL instructional principles are organized into two subcategories: personal values and community values. The personal values subcategory includes three key design principles, which aim to develop a coherent sense of identity, emotional competence, and learner agency.

5.1.1. Pursuit of Personal Values

First, learners are encouraged to systematically explore their existential value and identity in order to construct a life vision and set meaningful goals. Alamin and Sauri [28] argue that schools in the AI age must create space for students to reflect on personal values and ethical beliefs, prompting fundamental questions such as “Why do I exist?” Through this reflective process, learners rediscover their intrinsic worth and shape a distinct identity within their sociocultural context.

Second, the development of emotional competence is essential to sustaining psychological well-being and building healthy interpersonal relationships. The increasing prevalence of automation and digital communication can lead to a decline in direct human interaction, contributing to emotional detachment, isolation, and anxiety (Alamin & Sauri, 2024). In addition, the rapid pace of technological change may exacerbate stress by disrupting familiar learning environments, work roles, and social expectations. Cultivating emotional regulation, empathy, and interpersonal resilience enables learners to maintain psychological stability and a deeper sense of meaning in their lives—capacities that AI cannot replicate [29].

Third, the IPSL model emphasizes the importance of learner agency. As generative AI becomes more prevalent, learners risk becoming passive recipients of algorithmically generated information, which can weaken their creativity, critical thinking, and emotional insight [30]. To counter this tendency, learners must be equipped to critically evaluate AI-generated content, make socially and ethically sound decisions, and maintain a clear sense of personal purpose. Education, therefore, should not only teach students how to use AI effectively, but also empower them to take ownership of their learning and intentionally design lives that reflect their values and aspirations.

5.1.2. Pursuit of Community Values

From the perspective of community values, the IPSL framework emphasizes the development of learners’ ethical consciousness and social responsibility in the context of rapidly advancing AI technologies. While AI can process vast amounts of data with speed and efficiency, it lacks the capacity for ethical judgment. Moreover, AI-generated outputs may reflect bias, misinformation, or violations of privacy [28]. Therefore, it is imperative that learners be equipped to make autonomous and ethically sound decisions, particularly as they navigate emerging dilemmas in an increasingly complex digital society.

The first principle focuses on guiding learners to internalize ethical values and engage in continuous reflection on their relevance and application. Ethical literacy is not static; it requires ongoing evaluation and adjustment in light of evolving social norms, technologies, and global challenges. Education should support learners in developing this reflective capacity as a foundation for responsible citizenship and decision-making in AI-mediated contexts.

The second principle centers on the recognition and practice of human dignity as a foundational moral value. In a time when education is increasingly influenced by technology and automation, it becomes all the more important to reaffirm the uniqueness of human beings. Beyond technical competence, education must cultivate moral character and reinforce the belief that human dignity is inviolable. Teachers play a crucial role in this process, guiding students to make ethically grounded decisions rooted in empathy, respect, and shared humanity [28].

The third principle encourages learners to uphold and advance public values within their communities. As AI continues to reshape education, economics, and social systems, the complexity and uncertainty of societal issues are also intensifying. Without a strong ethical orientation toward the public good, AI-driven progress may result in fragmentation, inequality, or even social destabilization. Thus, IPSL calls for fostering a deep sense of responsibility in learners to contribute to the sustainability and well-being of their communities by prioritizing collective values over purely individual or technical outcomes.

5.2. Strategic Approaches for Value Pursuit

To pursue the inherent value of being human—particularly in ways that cannot be replicated by artificial intelligence—learners must be supported through a coherent set of strategies that reflect the demands of AI-integrated learning environments. Within the IPSL framework, these strategies emphasize the development of meta-learning as a foundation for self-directed and reflective learning, the enhancement of learners’ ability to solve unpredictable and complex problems, and the cultivation of future-oriented capabilities that enable flexible adaptation and creative response in uncertain contexts.

5.2.1. Meta-learning

Meta-learning, often described as “learning how to learn,” refers to the learner’s ability not only to acquire knowledge but also to understand and regulate their own learning processes through reflective thinking [31,32]. This capability allows learners to plan, monitor, and adjust their learning continuously, making it a fundamental competency in the age of artificial intelligence.

In contemporary educational contexts—where information retrieval and routine problem-solving are increasingly handled by AI—human adaptability and cognitive flexibility have emerged as essential educational advantages [31]. While AI systems can generate and deliver vast amounts of information, it remains the learner’s responsibility to critically interpret, contextualize, and apply that information to real-world problems.

Meta-learning comprises two interrelated dimensions: metacognition and meta-emotion. These dimensions work together to enhance the quality and depth of learning experiences [31]. Without sufficient metacognitive skills, learners may fall into a state of “metacognitive laziness”, passively accepting AI-generated content without engaging in critical evaluation or reflective thinking. Research shows that overreliance on generative AI can reduce cognitive engagement and suppress the development of independent thinking [21,32].

Thus, meta-learning is not only vital for navigating AI tools effectively but also for positioning AI as a cognitive partner—a facilitator that enhances rather than replaces human agency in learning.

The IPSL model incorporates three key instructional design principles related to meta-learning:

First, learners should be supported in setting meaningful and self-directed learning goals. Goal-setting serves as the foundation of self-regulated learning [33,34]. In AI-enhanced environments, where information overload is common and direction can easily be lost, clearly defined goals help learners prioritize and filter relevant knowledge [35,36,37].

Second, learners must develop the ability to independently plan, monitor, and revise their learning strategies. These executive skills allow learners to manage their cognitive processes and adopt strategies that maximize learning efficiency [38,39]. Given the accelerating pace of technological and epistemic change, learners must become flexible, autonomous, and capable of lifelong learning. As Garrison and Akyol [40] note, excessive dependence on AI can lead to uncritical acceptance of information, further underscoring the need for strong metacognitive regulation in digital learning environments.

Third, learners need to cultivate meta-emotional competence—the ability to recognize, understand, and regulate emotions during the learning process [41,42]. While positive emotions foster motivation and engagement, the effective management of negative emotions contributes to resilience and perseverance [43,44]. In AI-mediated learning environments, where human emotional support may be limited [45], such meta-emotional skills are even more critical. Furthermore, learners should be encouraged to develop empathy and engage in emotionally responsive communication with others. This deeply human capacity for emotional connection and mutual understanding cannot be replicated by AI and is essential for creating sustainable, human-centered learning environments.

5.2.2. Solving Unpredictable and Complex Problems

Contemporary educational theory has long emphasized the importance of developing learners’ ability to solve ill-structured problems—those that reflect the ambiguity, complexity, and uncertainty of real-world situations. Jonassen [46] criticized conventional schooling for relying too heavily on overly structured problems that fail to capture the dynamic nature of actual problem contexts. In reality, learners often face situations involving multiple variables, conflicting interests, and incomplete or evolving information, while traditional instruction tends to present simplified and static scenarios. This disconnect creates a significant gap between classroom learning and the competencies required in real-life contexts.

With the accelerating pace of technological advancement and the societal transformations driven by artificial intelligence, learners are increasingly required to address unpredictable and complex problems that cannot be resolved using standard procedures or pre-existing knowledge. These problems often feature multilayered structures, interdependent variables, and dynamic conditions that evolve over time and lead to uncertain outcomes [47,48]. To prepare learners for such challenges, IPSL emphasizes a set of instructional design strategies that foster cognitive adaptability and integrative reasoning.

Learners should be encouraged to consider multiple variables, stakeholders, and contextual uncertainties when engaging in problem-solving. As Jonassen [46] argued, linear and reductionist thinking is inadequate in addressing real-world complexity. Instructional approaches should therefore expose learners to authentic problems that incorporate competing values and perspectives to promote nuanced and holistic reasoning [48].

In addition, learners must be equipped to address fusion problems—problems that require the integration of academic knowledge, real-life experience, and AI-supported tools. Lombardi [49] emphasized that meaningful learning occurs when knowledge is applied to authentic, context-rich challenges. In today’s world, pressing societal issues such as climate change, algorithmic bias, or digital ethics demand a multidisciplinary approach that often involves human–AI collaboration [50,51,52].

Finally, learners must develop the capacity to manage ethical dilemmas and conflicting values that naturally arise during problem-solving processes. The rapid digital transformation powered by AI has intensified the complexity of such dilemmas, requiring learners to evaluate diverse viewpoints critically and construct socially responsible solutions [53,54]. Education should thus move beyond the pursuit of singular correct answers and instead guide learners to synthesize varied inputs and generate viable, context-sensitive resolutions.

5.2.3. Future-Oriented Capability

Traditional models of education and talent development have largely focused on competency—the mastery of specific knowledge and skills required to perform known tasks. However, in a rapidly changing and uncertain world, competency alone is no longer sufficient. What is increasingly needed is capability—the learner’s capacity to adapt, create, and act effectively in unfamiliar and evolving situations.

IPSL positions capability development as central to preparing learners for future-oriented education. Unlike competency, which often relates to predetermined outcomes, capability encompasses flexibility, curiosity, and continuous learning. Learners must be supported in developing the ability not only to acquire new skills, but also to unlearn outdated knowledge and approaches when necessary [55,56,57]. This learnability is now widely recognized as a critical criterion for employability and long-term professional growth.

Furthermore, learners should be guided to integrate artificial intelligence not merely as a functional tool, but as a “second brain”—an extension of their cognitive capacity. Effective human–AI collaboration allows for expanded data processing, deeper analytical thinking, and enhanced decision-making [58]. Learners must understand how to strategically engage AI in their thinking processes to approach problems from broader, more flexible perspectives [59,60].

Equally important is the cultivation of transdisciplinary thinking. Learners should be encouraged to apply their knowledge across disciplinary boundaries and transfer it to novel, unfamiliar contexts. Addressing complex societal issues—such as digital surveillance, public health, or climate resilience—requires integrated perspectives that transcend traditional subject-area silos[61,62]. Research supports those transdisciplinary approaches not only enhance knowledge transfer but also foster creativity and innovation in problem-solving across diverse domains.

5.3. Human–AI Collaborative Structures

As artificial intelligence continues to transform knowledge work and cognitive tasks, educational models must redefine the respective roles of humans and AI in learning. Within the IPSL framework, human–AI collaboration is operationalized through three distinct task categories: human-exclusive tasks, human–AI collaborative tasks, and AI-delegable tasks. This tripartite structure enables targeted instructional strategies that respect human dignity, maximize technological affordances, and prepare learners for hybrid problem-solving environments.

5.3.1. Tasks Exclusive to Humans

Even in the age of artificial intelligence, certain fundamental aspects of human nature—such as ethical reasoning, emotional depth, and existential reflection—remain irreplaceable by machines. Education must therefore continue to affirm human uniqueness and dignity, especially in contexts where the increasing efficiency and capability of AI might tempt overreliance. While AI may outperform humans in specific technical domains, excessive dependence risks undermining human creativity, autonomy, and ultimately, the sense of purpose that defines meaningful learning and living.

To safeguard these human dimensions, the IPSL framework emphasizes the importance of clearly identifying and preserving tasks that should be, or must be, carried out exclusively by humans—even when AI is technically capable of doing so.

First, learners should be guided to make final decisions based on their own values and ethical reasoning, particularly in socially and culturally embedded contexts. Although AI can offer algorithmic suggestions based on data patterns, it lacks the moral agency required to weigh competing values or assess ethical consequences. Therefore, human learners must take full responsibility for ethical judgment and decision-making throughout the learning process [26,28,63].

Second, students must develop a clear understanding of the ethical use and governance of AI. While AI systems function through data-driven logic, it is ultimately humans who define the normative frameworks—philosophical, legal, and social—that determine how AI should operate. These judgments require human-level abstraction and deliberation, which no algorithm can replicate [27,30].

Third, learners should be equipped to strategically allocate roles among tasks that are human-exclusive, human–AI collaborative, or AI-delegable. Understanding when and how to involve AI, and when to retain human responsibility, is a core competency for future professional and civic life. For collaboration to be effective, learners must be aware of AI’s affordances and limitations and possess the critical insight to design partnerships in which human and machine contributions are meaningfully integrated [26].

5.3.2. Human–AI Collaborative Tasks

Recent advances in artificial intelligence (AI) have underscored the potential of human–AI collaboration to enhance collective intelligence, yielding meaningful implications for education [14,64,65,66]. Studies have demonstrated that when humans and AI operate in complementary roles, they can produce more rational, creative, and nuanced decisions by reducing cognitive biases and expanding problem-solving capabilities [64,65].

In response to this, the IPSL model proposes three instructional design principles to foster effective human–AI collaboration in learning environments.

First, learners should be guided to define and approach problems from multiple perspectives in collaboration with AI. AI excels at processing large-scale and complex data sets, often exceeding the limits of human cognitive capacity [9]. When combined with human intuition and creativity, this synergy enables learners to restructure ill-defined problems in more integrated and multidimensional ways. Such tasks reposition learners from passive recipients of AI-generated output to active agents who co-investigate, reinterpret, and construct novel solutions informed by diverse data sources and perspectives.

Second, instructional designs should promote co-creativity, where learners use AI not as a substitute but as a catalyst for creative exploration. AI tools can offer diverse prompts, analogies, and iterations that expand learners’ cognitive reach, especially in artistic, design-based, and interdisciplinary learning contexts [10,67]. By helping to overcome fixation—rigid adherence to conventional thinking—AI facilitates divergent thinking and opens access to otherwise inaccessible ideas. Importantly, this form of assisted creativity enhances learners’ original thinking without undermining human emotion, judgment, or expressive intent.

Third, learners should be encouraged to engage with AI as a critical peer—a dialogic partner that not only provides information but also challenges assumptions, stimulates reflection, and promotes metacognitive development. Generative AI can prompt learners to examine problems from alternative angles, ask deeper questions, and refine their understanding through iterative reasoning [68,69]. This interaction fosters intellectual autonomy and encourages learners to become reflective and responsible thinkers in AI-mediated environments.

In sum, the augmentation of collective intelligence through human–AI collaboration must go beyond efficiency. It should intentionally cultivate learners’ creativity, critical thinking, and multidimensional reasoning. The three instructional principles—multi-perspective problem framing, co-creativity, and interaction with AI as a critical peer—are foundational to transforming learners into active, creative knowledge producers, rather than passive users of technology in the AI era.

5.3.3. Tasks Delegated to AI

As artificial intelligence (AI) becomes increasingly integrated into educational practice, collaborative problem-solving between learners and AI systems is rapidly becoming a practical reality. A key challenge in instructional design is determining which tasks should be appropriately delegated to AI without compromising the learner’s engagement, critical thinking, or sense of agency. Within the IPSL framework, three instructional design principles guide the identification and use of AI-delegable tasks.

The first principle highlights that repetitive and structured tasks—such as automated grading, instant feedback, content summarization, or scheduling—are best assigned to AI systems. These tasks often consume a significant portion of instructional time but contribute minimally to higher-order thinking. Delegating such tasks to AI allows educators and learners to focus on creative, reflective, and strategic dimensions of learning [70,71]. This approach not only improves efficiency but also fosters deeper engagement in self-directed learning and sustained problem-solving [72].

The second principle pertains to large-scale and cognitively intensive data processing. In contemporary educational settings, students are increasingly required to analyze complex datasets or navigate multilayered information structures. AI tools can effectively identify patterns, extract correlations, and generate real-time analytics that would be difficult for humans to process manually [73]. For example, in scientific research or social science contexts, AI can assist learners in interpreting big data, thereby freeing cognitive resources for conceptual understanding and critical analysis[10]. However, this delegation must be complemented with instructional designs that explicitly encourage critical reflection, ensuring that learners maintain active roles in interpreting AI-generated insights.

The third principle involves delegating physically hazardous or endurance-based tasks to AI. Laboratory experiments involving toxic substances, simulations of dangerous environments, or extended observation in field research may pose safety risks or induce fatigue. AI-driven robotics and virtual environments can mitigate these risks by taking over high-risk or monotonous components, allowing learners to safely engage with the theoretical and interpretive dimensions of the task [74]. Unlike humans, AI systems do not tire and are capable of sustaining operations over long durations, making them ideal for such scenarios.

Importantly, these instructional principles for AI task delegation are designed to maximize educational synergy between human and machine intelligence. However, for this synergy to be meaningful, learners must simultaneously develop both AI literacy and critical thinking skills [75]. Without this dual development, there is a risk of cognitive offloading, where learners passively accept AI outputs without reflective engagement. Educators must therefore create learning environments that actively prompt students to question, critique, and validate AI-generated information. Through such interactions, learners develop a clear sense of human-led decision-making and moral accountability, which are essential for ethical and effective learning in AI-integrated educational systems.

5. Conclusions

This study proposed Intelligent Problem-Solving Learning (IPSL) as a novel learning model tailored for the demands of the artificial intelligence (AI) era. Drawing on a comprehensive literature review and a two-phase expert validation process, the study developed a conceptual framework comprising three major categories and eight subcategories, culminating in the formulation of 18 instructional design principles.

At its core, the IPSL model places the pursuit of human existential value at the center of educational aims. It distinguishes the roles of humans and AI across three task domains—those that must be performed exclusively by humans, those requiring human–AI collaboration, and those that can be delegated to AI. Through meta-learning, learners are guided to strategically determine how to approach each task type, thereby enhancing their future-oriented capability to solve complex and unpredictable problems. A key feature of IPSL is this integration of role differentiation into instructional design, providing a concrete and actionable structure for human–AI collaboration.

Theoretically, IPSL offers several distinct contributions compared to existing instructional design models. First, it shifts the focus from competency-based education to capability-based learning, emphasizing adaptability, creativity, and transferability over the mastery of fixed knowledge [6,7]. Unlike fixed competencies, capabilities refer to a learner’s potential to continuously learn, unlearn, adapt, and act with confidence in unfamiliar and evolving contexts. Second, it advances a model of AI-integrated instructional design that moves beyond human-to-human collaboration, recognizing AI as a legitimate learning partner. This approach is grounded in Extended Mind Theory [4,5], which posits that cognitive processes extend into external tools, such as AI. Third, IPSL explicitly recenters human values and responsibilities in education. In a time when AI challenges human agency in creativity and decision-making, IPSL affirms that ethical judgment and final decisions must remain human-led [27].

Practically, the IPSL design principles offer clear strategies for implementation. By delegating repetitive or data-intensive tasks to AI, educators and learners can allocate more time to higher-order thinking, creativity, and reflection. When applied effectively, IPSL enhances both instructional efficiency and learner engagement.

Collectively, IPSL provides a robust framework for teaching with AI, —as a learning partner—rather than merely about AI as a subject. It offers a future-oriented paradigm that fosters co-creativity, critical thinking, and human–AI synergy in the classroom. Learners are encouraged to reconstruct problems from diverse perspectives and generate solutions in partnership with AI—aligning with research that shows how collaborative intelligence enhances decision-making and innovation [10,14].

Importantly, IPSL promotes a balanced approach to AI integration: one that embraces technological innovation while safeguarding human-centered judgment, autonomy, and ethical reflection. Several design principles within the model explicitly warn against metacognitive laziness and overreliance on AI, underscoring the importance of maintaining learner agency. In doing so, IPSL provides practical guidance for educators seeking to leverage AI’s affordances without compromising the fundamental human values that lie at the heart of meaningful education.

6. Future Research and Recommendations

Lastly, this study proposes several directions for future research and practical implementation to further advance the development and applicability of the IPSL framework.

First, empirical validation in real-world educational settings is essential. Applying IPSL and its instructional design principles in actual classrooms will enable researchers to assess its practical utility, effectiveness, and areas for refinement. For example, experimental studies could examine the impact of IPSL-based strategies on students’ meta-learning skills, problem-solving performance, and critical decision-making abilities.

Second, future research should prioritize teacher professional development. Given that the successful implementation of IPSL depends heavily on the teacher’s role, there is a need to design training programs and institutional support systems that enhance teachers’ capacity to design and facilitate human–AI collaborative learning environments.

Third, efforts should also be directed toward fostering AI literacy and ethical responsibility at the learner level. Consistent with the core philosophy of IPSL, instructional designs must help learners engage with AI ethically, while retaining the ability to make independent and value-based decisions.

In addition, due to the rapid evolution of AI technologies, the IPSL framework must remain flexible and adaptable. Future studies should explore how to update its design principles in response to emerging AI capabilities and investigate its applicability across diverse educational levels, subject areas, and learning contexts.

Such ongoing research is crucial not only to strengthen the theoretical foundation of IPSL, but also to ensure its viability as a sustainable instructional approach for cultivating creative, ethical, and future-ready learners.

In conclusion, the IPSL model presented in this study offers a forward-looking framework for developing learner competencies aligned with the demands of future society. Rather than viewing AI as a threat to education, IPSL positions it as a strategic partner—one that complements, rather than replaces, human cognition, creativity, and moral judgment.

By promoting a balanced integration of technology and human values, IPSL presents a design paradigm that is both technologically innovative and human-centered. With continued research and implementation, IPSL has the potential to serve as a catalyst for educational innovation, shaping a new generation of learning environments where artificial intelligence and human intelligence coexist and co-evolve.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Yuna Lee and Sang-Soo Lee; methodology, Sang-Soo Lee; formal analysis, Yuna Lee; investigation, Yuna Lee and Sang-Soo Lee; visualization, Yuna Lee; writing—original draft preparation, Yuna Lee and Sang-Soo Lee. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Utecht, J.; Keller, D. Becoming relevant again: Applying connectivism learning theory to today’s classrooms. Crit. Quest. Educ. 2019, 10, 107–119 Available online: https://ericedgov/. Available online: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1219672 (accessed on 27 May 2024).

- Siemens, G. Connectivism: Learning as network-creation. ASTD Learn. News 2005, 10, 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Downes, S. Places to go: Connectivism & connective knowledge. Innovate J. Online Educ. 2008, 5, Article 6 Available online: https://nsuworksnovaedu/innovate/vol5/iss1/6 (accessed on 27 May 2024). Available online: https://nsuworks.nova.edu/innovate/vol5/iss1/6 (accessed on 27 May 2024).

- Clark, A.; Chalmers, D. The extended mind. Anal. 1998, 58, 7–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, A.M. Extended Mind: The Power of Thinking Outside the Brain; Mariner Books: Boston, MA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Fraser, S.W.; Greenhalgh, T. Complexity science: Coping with complexity: educating for capability. BMJ 2001, 323, 799–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, V.; Oweis, E.; Woods, C.J. Mapping the Distance: From Competence to Capability. ATS Sch. 2023, 4, 400–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sakata, N. Capability Approach to Valued Pedagogical Practices in Tanzania: An Alternative to Learner-Centred Pedagogy? J. Hum. Dev. Capab. 2021, 22, 663–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dede, C.; Etemadi, A.; Forshaw, T. Intelligence Augmentation: Upskilling Humans to Complement AI; The Next Level Lab at the Harvard Graduate School of Education, President and Fellows of Harvard College: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Elfa, M.A.A.; Dawood, M.E.T. Using Artificial Intelligence for enhancing Human Creativity. J. Art, Des. Music. 2023, 2, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlDahdouh, A.A.; Osório, A.; Caires, S. Understanding knowledge network, learning and connectivism. Int. J. Instr. Technol. Distance Learn. 2015, 12, 3–21. [Google Scholar]

- Hase, S. Learner defined curriculum: Heutagogy and action learning in vocational training. South. Inst. Technol. J. Appl. Res. 2011, 1, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Li, D.H.; Towne, J.; How AI and human teachers can collaborate to transform education. World Economic Forum 2025. Available online: https://www.weforum.org/stories/2025/01/how-ai-and-human-teachers-can-collaborate-to-transform-education/ (accessed on 27 May 2024).

- Dellermann, D.; Calma, A.; Lipusch, N.; Weber, T.; Weigel, S.; Ebel, P. The Future of Human-AI Collaboration: A Taxonomy of Design Knowledge for Hybrid Intelligence Systems. Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences. LOCATION OF CONFERENCE, COUNTRYDATE OF CONFERENCE;

- Richey, R.C.; Klein, J.D. Design and Development Research: Methods, Strategies and Issues; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Churchill, D. Conceptual model design and learning uses. Interact. Learn. Environ. 2013, 21, 54–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, N.M.; Laughter, L.; Sadid-Zadeh, R.; Smith, C.; Dolan, T.A.; Crain, G.; Squarize, C.H. Adopting artificial intelligence in dental education: A model for academic leadership and innovation. J. Dent. Educ. 2022, 86, 1545–1551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luft, J.A.; Jeong, S.; Idsardi, R.; Gardner, G. Literature Reviews, Theoretical Frameworks, and Conceptual Frameworks: An Introduction for New Biology Education Researchers. CBE—Life Sci. Educ. 2022, 21, rm33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Selvik, J.T.; Abrahamsen, E.B.; Moen, V. Conceptualization and application of a healthcare systems thinking model for an educational system. Stud. High. Educ. 2022, 47, 1872–1889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sleegers, P.; Brok, P.D.; Verbiest, E.; Moolenaar, N.M.; Daly, A.J. Toward Conceptual Clarity. Elementary Sch. J. 2013, 114, 118–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, E.; Lim, R.; Kim, D. A Schema-Based Instructional Design Model for Self-Paced Learning Environments. Educ. Sci. 2022, 12, 271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 강, 정. The Development of Instructional Design Principles for Creativity Convergence Education. Korean J. Educ. Methodol. Stud. 2015, 27, 276–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu, G.T.; Park, K.O. Developing study on instructional design principles based on the social studies blended learning for students with disabilities in inclusive environments. J. Spec. Educ. Curric. Instr. 2022, 15, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynn, M.R.; R. , M. Determination and Quantification Of Content Validity. Nurs. Res. 1986, 35, 382–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gwet, K.L. Handbook of Inter-Rater Reliability: The Definitive Guide to Measuring the Extent of Agreement Among Raters, 4th ed.; Advanced Analytics, LLC: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Huo, Y.; How AI ideas affect the creativity, diversity, and evolution of human ideas. arXiv 2023, preprint. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/2401.13481 (accessed on 27 May 2024).

- Rubin, C. Artificial intelligence and human nature. New Atlantis 2003, 1, 88–100 Available online: https://thenewatlantiscom/wp. Available online: https://thenewatlantis.com/wp-content/uploads/legacy-pdfs/TNA01-Rubin.pdf (accessed on 27 May 2024).

- Alamin, F.; Sauri, S. EDUCATION IN THE ERA OF ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE: AXIOLOGICAL STUDY. PROGRES Pendidik. 2024, 5, 146–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garner, P.W. Emotional Competence and its Influences on Teaching and Learning. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 2010, 22, 297–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raza, A. Teaching with AI: Practical approaches to using generative AI in class. Harv Metacognition, meta-learning and metamind ard Bus. Publ. 2024.

- Fadel, C.; Black, A.; Tylor, R.; Slesinski, J.; Dunn, K. Education for the Age of AI; Center for Curriculum Redesign: Boston, MA, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Stanton, J.D.; Sebesta, A.J.; Dunlosky, J. Fostering Metacognition to Support Student Learning and Performance. CBE—Life Sci. Educ. 2021, 20, fe3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmerman, B.J. Becoming a Self-Regulated Learner: An Overview. Theory Into Pr. 2002, 41, 64–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schunk, D.H.; Greene, J.A. (Eds.) Handbook of Self-Regulation of Learning and Performance, 2nd ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Hyperspace. Achieve Goals with AI-enabled Goal Setting in VR Training. 2023. Available online: https://hyperspace.mv/ai-enabled-goal-setting-skills-development-in-vr/ (accessed on 27 May 2024).

- Tribe, AI.; The Problem of Content Overload in Higher Education—and How AI Solves It. Tribe AI 2025. Available online: https://www.tribe.ai/applied-ai/ai-and-content-overload-in-higher-education (accessed on 27 May 2024).

- Zakrajsek, T.D.; Teaching students AI strategies to enhance metacognitive processing. Scholarly Teach. 2023. Available online: https://www.scholarlyteacher.com/post/teaching-students-ai-strategies-to-enhance-metacognitive-processing (accessed on 27 May 2024).

- Flavell, J.H. Metacognition and cognitive monitoring: A new area of cognitive–developmental inquiry. Am. Psychol. 1979, 34, 906–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schraw, G.; Dennison, R.S. Assessing Metacognitive Awareness. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 1994, 19, 460–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrison, D.; Akyol, Z. Toward the development of a metacognition construct for communities of inquiry. Internet High. Educ. 2015, 24, 66–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, J.D.; Salovey, P. What is emotional intelligence. In Salovey, P.; Sluyter, D., Ed.; Emotional Development and Emotional Intelligence: Educational Implications; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1997; pp. 3–31. [Google Scholar]

- Pekrun, R. The Control-Value Theory of Achievement Emotions: Assumptions, Corollaries, and Implications for Educational Research and Practice. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 2006, 18, 315–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pekrun, R.; Goetz, T.; Titz, W.; Perry, R.P. Academic Emotions in Students' Self-Regulated Learning and Achievement: A Program of Qualitative and Quantitative Research. Educ. Psychol. 2002, 37, 91–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.; Cable, D.M.; Kim, S.; Wang, J. Emotional competence and work performance: The mediating effect of proactivity and the moderating effect of job autonomy. J. Organ. Behav. 2009, 30, 983–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, J.; Rheu, M. (.; Zhang, Y.; Dai, Y.; Peng, W. Mediated Social Support for Distress Reduction: AI Chatbots vs. Human. Proc. ACM Human-Computer Interact. 2023, 7, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonassen, D.H. Toward a design theory of problem solving. Educ. Technol. Res. Dev. 2000, 48, 63–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ADR Times. Complex vs Complicated Understanding the Differences. 2024. Available online: https://adrtimes.com/complex-vs-complicated/ (accessed on 27 May 2024).

- Iancu, P.; Lanteigne, I. Advances in social work practice: Understanding uncertainty and unpredictability of complex non-linear situations. J. Soc. Work. 2020, 22, 130–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lombardi, M.M.; Authentic learning for the 21st century: An overview. EDUCAUSE Learn. Initiat. 2007. Available online: https://library.educause.edu/resources/2007/1/authentic-learning-for-the-21st-century-an-overview (accessed on 27 May 2024).

- Aquino, Y.S.J.; Carter, S.M.; Houssami, N.; Braunack-Mayer, A.; Win, K.T.; Degeling, C.; Wang, L.; A Rogers, W. Practical, epistemic and normative implications of algorithmic bias in healthcare artificial intelligence: a qualitative study of multidisciplinary expert perspectives. J. Med Ethic-. [CrossRef]

- Garibay, O.O.; Winslow, B.; Andolina, S.; Antona, M.; Bodenschatz, A.; Coursaris, C.; Falco, G.; Fiore, S.M.; Garibay, I.; Grieman, K.; et al. Six Human-Centered Artificial Intelligence Grand Challenges. Int. J. Human–Computer Interact. 2023, 39, 391–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Rodríguez, N.; Del Ser, J.; Coeckelbergh, M.; de Prado, M.L.; Herrera-Viedma, E.; Herrera, F. Connecting the dots in trustworthy Artificial Intelligence: From AI principles, ethics, and key requirements to responsible AI systems and regulation. Inf. Fusion 2023, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, L.Y.; Albert, C.; Rutland, J.; Hennigan, C. The Fourth Industrial Revolution, Artificial Intelligence, and Domestic Conflict. Glob. Soc. 2022, 37, 375–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raisch, S.; Fomina, K. Combining Human and Artificial Intelligence: Hybrid Problem-Solving in Organizations. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2025, 50, 441–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holdsworth, S.; Thomas, I. Competencies or capabilities in the Australian higher education landscape and its implications for the development and delivery of sustainability education. High. Educ. Res. Dev. 2020, 40, 1466–1481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phelps, R.; Hase, S.; Ellis, A. Competency, capability, complexity and computers: exploring a new model for conceptualising end-user computer education. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 2004, 36, 67–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Lu, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Gong, S.; Li, B. Organisational unlearning, organisational flexibility and innovation capability: an empirical study of SMEs in China. Int. J. Technol. Manag. 2013, 61, 132–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malone, T.W. Superminds: The Surprising Power of People and Computers Thinking Together; Little, Brown Spark: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Brynjolfsson, E.; McAfee, A. Machine, Platform, Crowd: Harnessing Our Digital Future; W.W. Norton & Company: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Davenport, T.H.; Ronanki, R. Artificial intelligence for the real world. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2018, 96, 108–116 Available online: https://hbrorg/2018/01/artificial. Available online: https://hbr.org/2018/01/artificial-intelligence-for-the-real-world (accessed on 27 May 2024).

- Donelle, L.; Comer, L.; Hiebert, B.; Hall, J.; Smith, M.J.; Kothari, A.; Burkell, J.; Stranges, S.; Cooke, T.; Shelley, J.M.; et al. Use of digital technologies for public health surveillance during the COVID-19 pandemic: A scoping review. Digit. Heal. 2023, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morss, R.E.; Wilhelmi, O.V.; Meehl, G.A.; Dilling, L. Improving Societal Outcomes of Extreme Weather in a Changing Climate: An Integrated Perspective. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2011, 36, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]