1. Introduction

Prolonged exposure of diabetes can alter glial cell functions of astrocytes and microglia. Astrocytes modulate the synthesis and transport of nutrients and support neurotransmitter function, whereas microglia respond quickly to CNS injury and insult [

1,

2]. Astrocytic end feet and blood vessels are the major component of the blood brain barrier (BBB) which provides metabolic support to neurons inside the neuroependyma. Thus, any changes in morphology of glial cells not only affect the morphology of cerebral blood vessels, but also cause the breakdown of physiological effects including metabolism and synaptic transmission between the CNS and PNS [

3,

4].

Earlier studies have shown that the diabetic environment can increase glial cell death that impacts neural cells and may contribute to cognitive impairment [

5]. Previous research in our laboratory showed that the type-2 diabetic mouse is susceptible to neuronal cell death very early following ischemic insult. These defects increased BBB permeability especially in the caudate at 4 h post ischemia and the cortex by 24 h [

6].

A completely different pattern of temporal changes in microglia and astrocytic activation and cytokine expression occurred in the diabetic mouse in comparison to non-diabetic animals. The glial cell response was delayed in diabetic brain, and cell death occurred early following ischemic insult [

7,

8] . Similar patterns of mRNA expression were observed at 10 and 24 h post ischemic injury as shown in

Figure 1. Therefore, we hypothesized that changes in the baseline activation of glial cells due to persistent hyperglycemia may make diabetic brains more susceptible to neuronal cell death post ischemia.

Astrocytes are dynamic partners of neurons and provide a substantial amount of energy both as a source of glucose and lactate and help to remove excessive lactate to prevent toxicity [

9,

10]. Microglia is the first line of defense against any injury to preserve a healthy brain. It continuously guards the brain to remove any pathogen or debris to preserve a healthy brain [

11]. Therefore, the integrity and function of the glial cells are utmost important. Hence, in this study, we examined three different brain regions including the motor cortex, caudate and hippocampus because these regions are responsible for motor coordination and memory functions. In addition, these regions of the brain are more vulnerable to death post ischemic insult.

High levels of blood glucose adversely affect the endothelial cells of the cerebrovascular system and consequently cause oxidative stress resulting in the abnormal pathology of neuron and glia cells. Previously, we have observed the significant increase of metalloproteinases activity and loss of tight junctional proteins in diabetic brain upon ischemic insult [

12].

In this study, we examined brains from uninjured mice to establish the baseline changes in glial cell morphology and function in diabetic and normal animals. The number of astrocytes and microglia in the motor cortex, caudate, and CA3 region of the hippocampus were quantitated. Glial functions were assessed by blood vessel permeability in the motor cortex and caudate. We found a significant increase in the number of activated astrocytes in the cortex and caudate and the number of microglia/macrophages in the caudate of db/db mice at 12-weeks, along with leaky blood vessels and loss of tight junction protein comparison to non-diabetic animals.

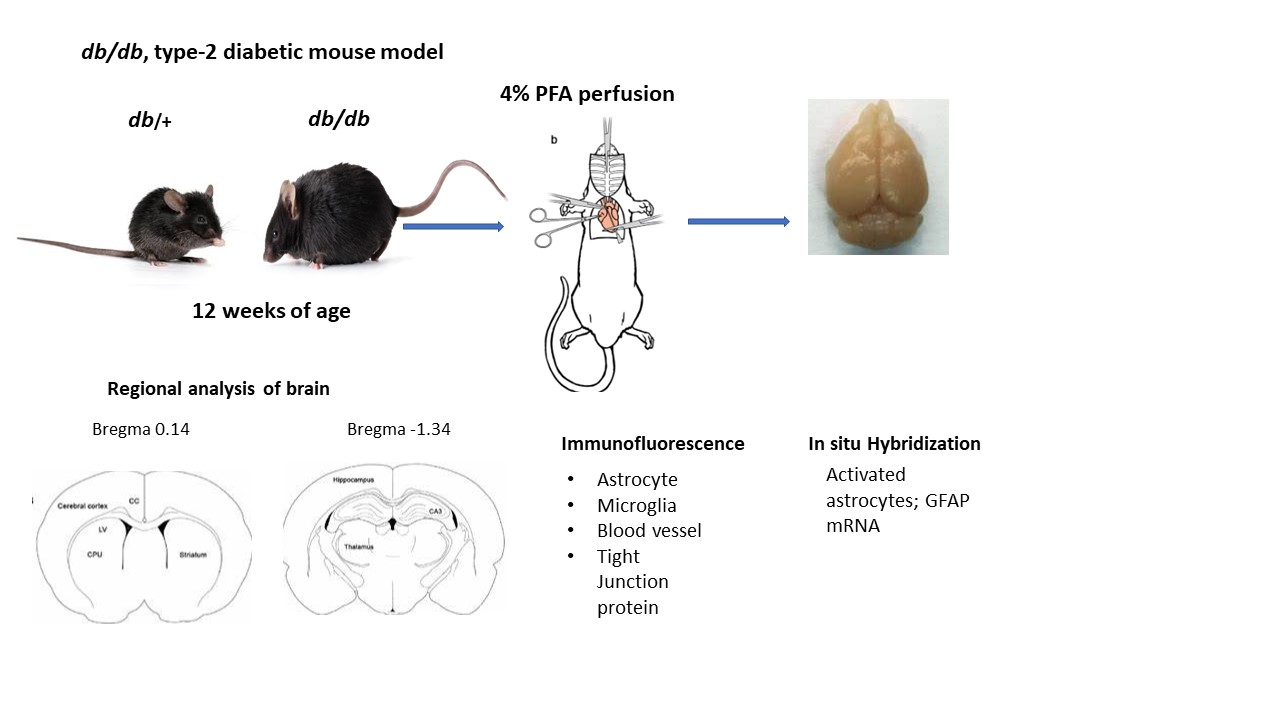

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Collection and Tissue Processing

All the experimental procedures in this study were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Penn State University. Male type-2 diabetic db/db and their heterozygous nondiabetic control db/+ mice were obtained from Jackson laboratory (JAX stock #004456) at 11–12 weeks of age. All mice were housed (2 per cage) in ventilated cages, maintained on a 12 h dark-light cycle with free access to food and water. Post acclimatization, body weight and blood glucose were measured using a tail prick with the BD Logic TM Meter (BD Pharmingen, San Jose, CA, USA). Mice were anesthetized with ketamine/xylazine and intracardiac perfused with 1X phosphate buffered saline (PBS)/ 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA). The fixed brain samples were collected and post fixed in 4% PFA overnight, then cryoprotected with 15% and 30% sucrose gradient. The brains were quickly rinsed with 1xPBS and immersed in cold isopentane (-400C) and stored at -800C until processing for immunolabeling. For in situ hybridization, mouse brains were collected at 10 and 24 h post hypoxic-ischemic injury and fresh frozen in cold isopentane (-400C) and stored at -800C for further processing.

2.2. Immunofluorescence Staining

Brain sections (16 µm) were obtained at different levels, bregma 0.14 mm for motor cortex and caudate and bregma -1.34 for hippocampal region. Brain tissue was washed with 1x PBS for 10 minutes followed by 1 h incubation with 0.5% H

2O

2 at room temperature, washed with 0.3% Triton /1xPBS three times for 5 minutes and blocked with 10% normal goat serum in 0.3% Triton/1xPBS/1% bovine serum albumin for 1 h at room temperature. The sections were incubated with one of the following antibodies: mouse monoclonal GFAP (1:500, MAB 360, Millipore Sigma), rabbit polyclonal Iba-1 (1:100, 013-27681, Fujifilm Wako), rabbit anti-mouse occludin (1:50, Invitrogen), rabbit polyclonal IgG (1:500, ab150077, abcam) and tomato lectin (1:500, DL-1178-1, Vector lab) in blocking solution overnight at 4

0C. The next day, sections were washed with slow agitation in 0.3% triton/1x PBS for 3 times for 15 minutes each followed by incubation with either Alexa Fluor 488 or 546 conjugated goat anti-rabbit or goat anti- mouse secondary antibody (1:500, Jackson Laboratory) at room temperature for 1 h. The sections were washed with agitation with h 1X PBS for 15 minutes followed with DAPI (1: 5000, D9542, Sigma) staining for 10 min. Post nuclear staining, sections were washed with 1x PBS, twice and mounted with Aqua Poly/ Mount. The images were captured using a Zeiss LSM 900 with Aairy scan/2 Confocal microscope[

13].

2.3. Regional Analysis of Glial Cells

Images of different brain regions of

db/+ and

db/db mice were captured at the same setting under confocal microscope (Zeiss LSM 900). The images were analyzed by Image J software as described earlier [

14,

15]. The images were color deconvoluted and the threshold was adjusted to reduce the background. The numbers of activated astrocytes that were above 25 pixels and microglia above 10 pixels were counted. At least 4 different brain sections for each region and mouse condition were analyzed and the numbers of cells averaged.

2.4. In Situ Hybridization

Cryosections (16µm) were analyzed for glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) mRNA by

in situ hybridization as described earlier[

7,

16] . Rat GFAP (1159 base pair) was transcribed by enzyme T7 and SP6 polymerase for antisense and sense and linearized by PVU II. This probe was labelled

35S to generate riboprobes for in situ hybridization. The brain sections were hybridized with riboprobe at 58

0C for 16 h and then washed with 0.1x SSC at 50

0C for 15 minutes. The sections were exposed to autoradiographic film for 48 h and scanned for analysis.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

All data are expressed as mean + SEM. Two tailed, unpaired Student “t” test was applied to compare the data between non-diabetic and diabetic mice. Data were analyzed by GraphPad Prism 8.0 and statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

3. Results

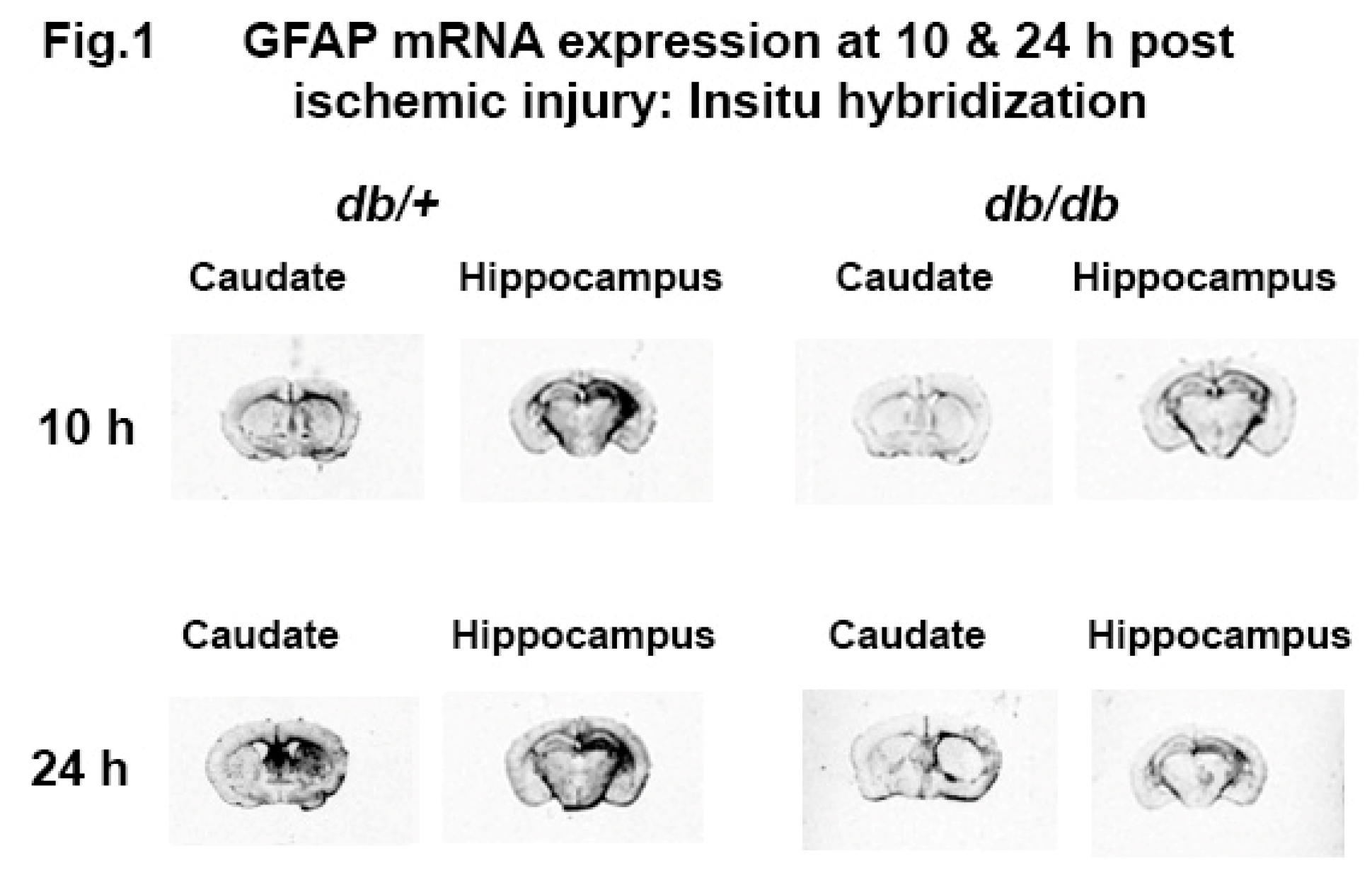

3.1. GFAP mRNA Changes with Diabetes

An overall reduced expression of GFAP mRNA was observed in

db/db mouse brain compared to

db/+ both in caudate and hippocampus at 10 and 24 h post ischemic (HI) injury. GFAP mRNA expression was remarkably increased in the caudate of the

db/+ mouse at 24 h whereas, the GFAP mRNA expression in the hippocampus remained elevated at 24 h as shown in

Figure 1. However, the low levels of expression were lost in

db/db mouse from 10 to 24 h in caudate and remain same in hippocampus until 24 h post HI. Similar temporal changes have been shown earlier for both activated astrocytes (GFAP), microglia (bfl-1) and proinflammatory cytokines (IL1β) in diabetic mouse brain following post HI. These data prompted our current investigation on the baseline activation of glial cells as the cause of impaired response to injury in diabetic mouse brain.

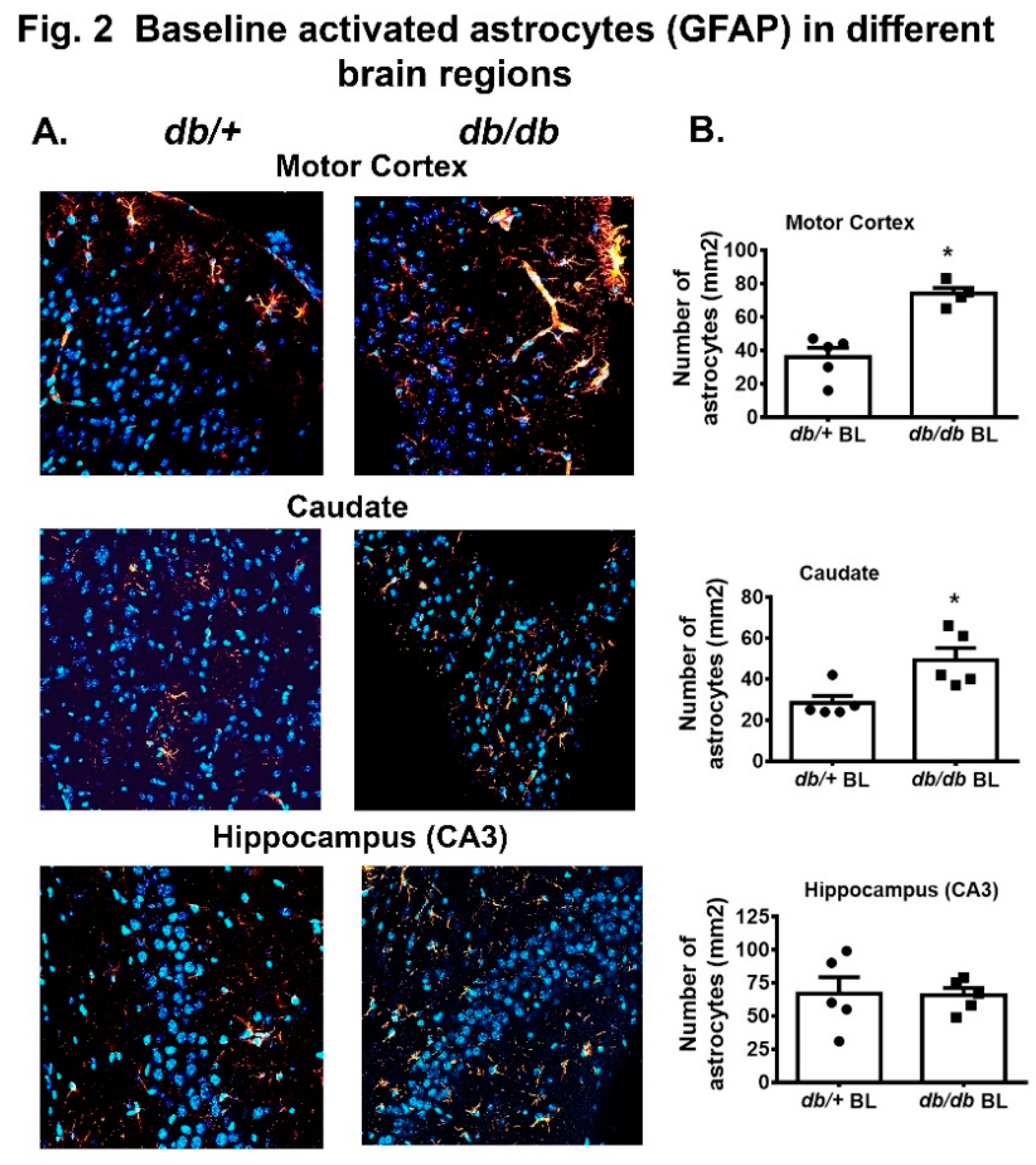

3.2. Baseline Changes in Astrocytes Activation with Diabetes

In this study, we compared the activated astrocytes (GFAP positive cells) in motor cortex, caudate and hippocampus (CA3) in both

db/+ and

db/db mice. We chose to analyze these brain areas based on our previous observations that they were more vulnerable to significant neuronal cell death post HI injury. A significant increase in the number of activated astrocytes were recorded in motor cortex and caudate in

db/db mouse brain compared to

db/+ as shown in

Figure 2A,B. No difference in GFAP+ cells was observed in CA3 region between these two groups.

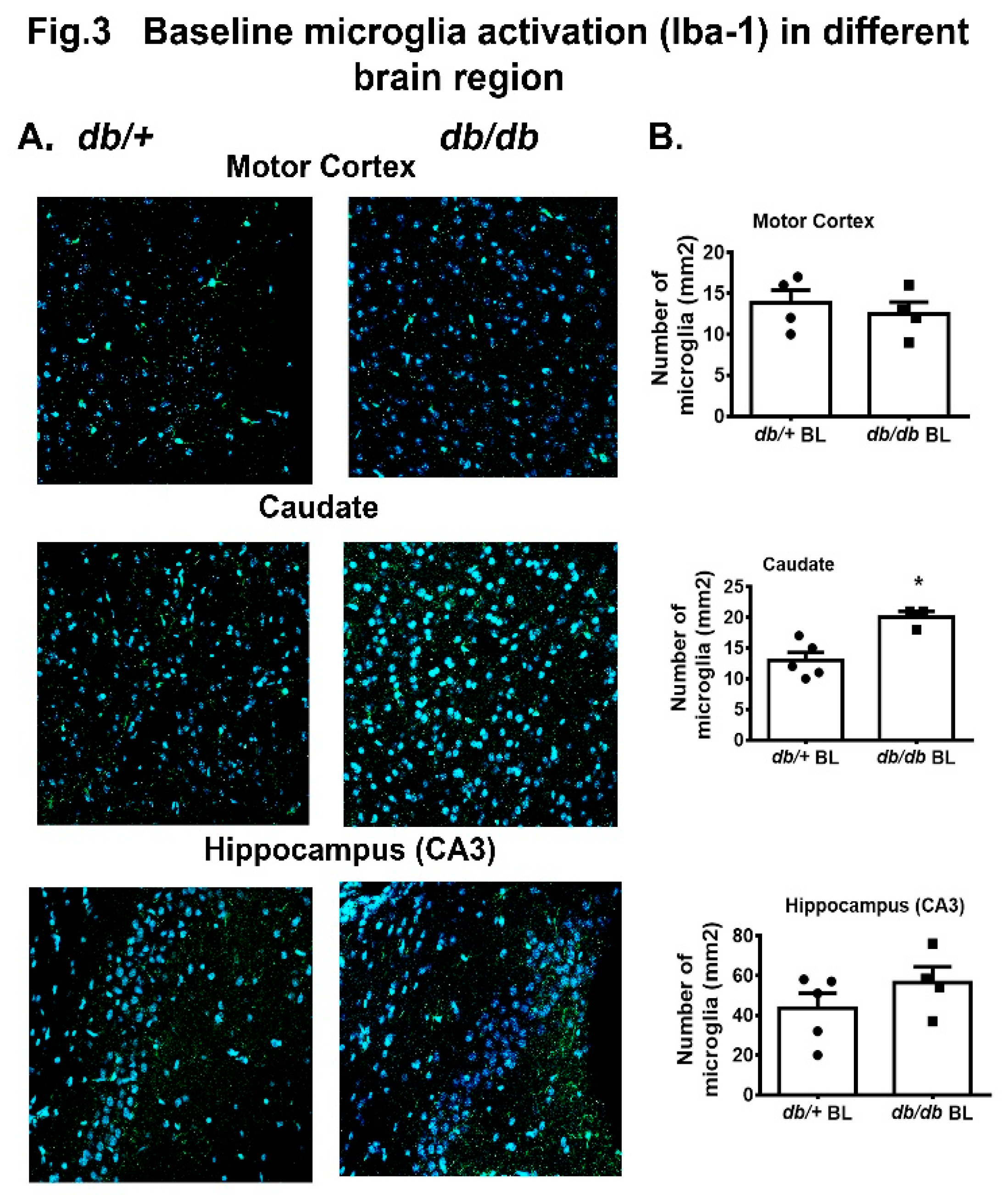

3.3. Baseline Changes in Microglia/Macrophage with Diabetes

In earlier studies, microglial expression or activation was found to be reduced / delayed in diabetic mouse brain post HI injury and a greater number of macrophages were measured by 48 h post HI[

17]. In this study, we measured the Iba-1 positive cells in motor cortex, caudate and hippocampus (CA3) region of both

db/db and

db/+ mouse at 12 weeks of age. We observed a significant increase in microglial expression in the

db/db+ caudate compared to

db/+ mice as shown in

Figure 3A,B. There were no significant changes observed between

db/+ and

db/db mice in motor cortex and hippocampus (CA3).

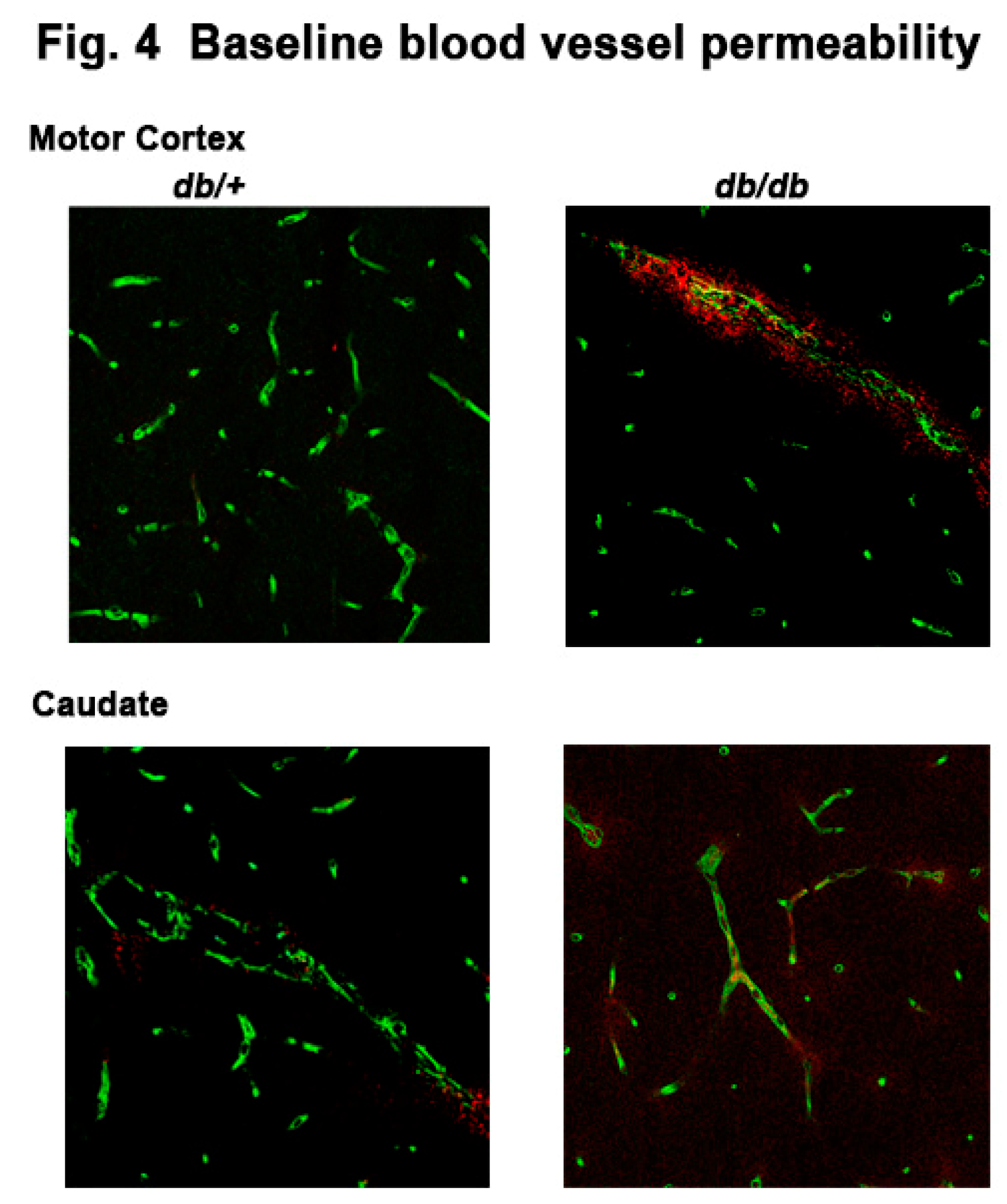

3.4. Baseline Changes in Blood Vessel Integrity with Diabetes

Previously, we observed albumin permeability as early as 4 h post HI injury in caudate of

db/db mouse brain[

6,

12]. In this study, we investigated the effect of diabetes on blood vessel integrity in different brain regions. We performed double staining with specific DyLight

™ 488 labeled tomato lectin (green) specific for the blood vessel marker and anti IgG antibody conjugated with CF® Dyes red. We observed a leakage of serum IgG around the blood vessels both in the motor cortex and caudate of the diabetic mouse brain compared to

db/+ mice as shown in

Figure 4, suggesting degenerating blood vessels in diabetic mouse brain at 12 weeks of age.

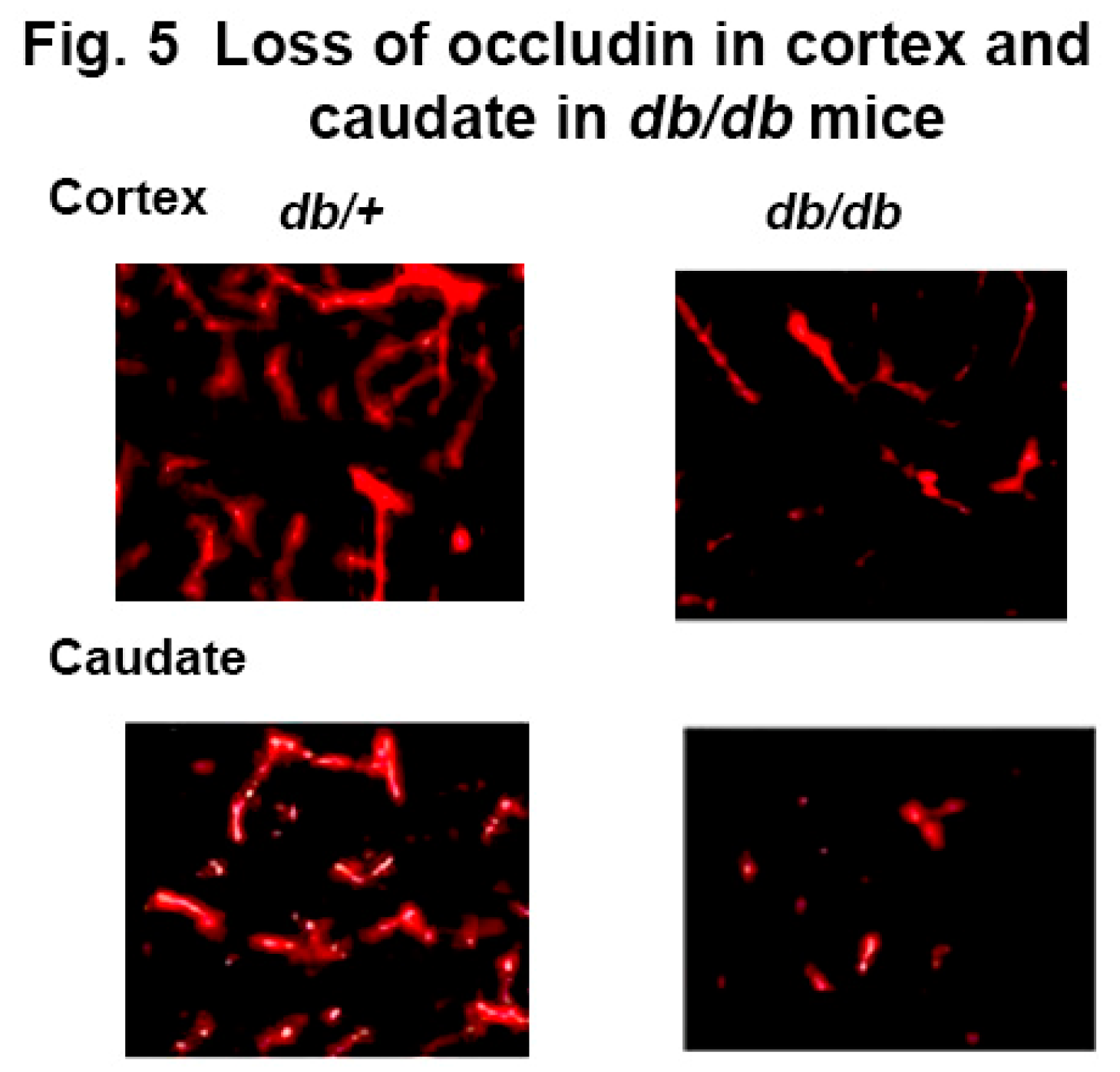

3.5. Loss of Tight Junction Protein with Diabetes

To further confirm the blood vessel leakage in diabetic mice, we examined tight junctions as the cause of the leakage of serum IgG. Using occludin, a well-known marker of the blood brain barrier permeability, we stained the

db/db and

db+ mouse brain with anti-occludin antibody to assess the integrity of the tight junction protein. Images revealed significantly less staining of occludin in the cortex and caudate of

db/db mouse brain compared to

db/+ as shown in

Figure 5 suggesting a compromised blood brain barrier in the

db/db mouse brain due to diabetes.

4. Discussion

In this study, we determined the changes in baseline expression and activity of astrocytes and microglia in different brain regions in type-2 diabetic mice. The data suggest that there are significantly greater numbers of GFAP positive astrocytes in cortex and caudate, whereas Iba-1 positive microglia/macrophage are only increased in the caudate of db/db mouse compared to db/+. These effects were associated with increased serum IgG permeability in the cortex and caudate and loss of occludin in the vessels in diabetic mice in comparison to non-diabetic controls.

The effect of diabetes on neuroglial cells and vascular changes is the focus of study after several years of study showing that diabetic patients are more susceptible to various neurological and neurodegenerative diseases including to cerebral ischemic injury [

18,

19,

20]. High blood glucose has been shown to cause the higher neuronal glucose toxicity and may be the underlying reason that compromises glial cell activity, necessary for neuronal survival [

21]. Thus, it is important to understand the changes in glial cell activity in type-2 diabetic brain.

The studies from our laboratory disclosed that astrocytes and microglial activations are diminished or delayed in

db/db and

ob/ob mouse post ischemic injury accompanied with increased MMP-9 activity and BBB permeability. These changes led, over time, to significantly greater neuronal cell deaths and compromised recovery post HI injury [

8,

12]. Therefore, in this study we confirm and extend our studies to investigate the baseline changes happening in different brain region to understand the pathological changes within the diabetic brain, while evaluating the repair and response of recovery post ischemic insult.

In general, astrocytes are more resistant to cellular damage. However stressed astrocytes lose their control over water movement, release of glutamate, and the balance between intracellular Ca

2+ and extracellular K+ resulting in edema and neuronal excitability that leads to failed protection of neurons[

22,

23,

24]. In this study, we observed a greater number of activated astrocytes in motor cortex and caudate without any injury in diabetic mice, which suggests that persistent hyperglycemia may activate the astrocytes, therefore regular functions of astrocytes are compromised, and they are more vulnerable to death post injury. Though, we have seen a rapid decline in GFAP mRNA (

Figure 1) and a significant neuronal cell death in

db/db mice post HI in previous studies, we did not find any significant change in activated astrocytes in the hippocampal (CA3) region as shown in

Figure 2. Similar to our report, Liu et al showed a rapid decline of GFAP mRNA starting at 1h post HI in spontaneously hypertensive rat preceding neuronal death [

25]. These data on compromised neuronal-glial interaction confirm their critical role in determining the outcome and repair of CNS injury.

Another important brain cell which maintains the CNS health is microglia, which produces essential cytokines to mediate brain immunological responses [

2,

26]. Previously we reported less activation of microglia and concomitantly delayed cytokines release in

db/db mice in post ischemic brain [

7]. In this study, we observed a greater number of activated microglia in caudate without any insult suggesting a compromised state of microglia in type-2 diabetic mouse brain (

Figure 3). In this state, the microglia cannot properly respond during post injury, often leading to immune depression within the brain and consequently greater neuronal cell death.

CNS microglia are very sensitive to any alterations such as stress, diet and aging. Several studies have suggested that diabetic persons are more vulnerable for developing dementia and Alzheimer’s disease and the changes in the microglial population and phenotype may play a significant role [

27,

28]. However, we did not find any significant change in Iba-1 positive microglia in hippocampus (CA3) region. Our data are supported by other studies that did not find any change in microglial densities in hippocampal region in high fat diet induced obese male mice, rather suggested that the phagocytic phenotype of microglia causes synaptic engulfment on hippocampal neuron and promotes cognitive decline [

29,

30] .

Lastly, we evaluated the vascular changes in

db/db mouse without any insult or injury because altered BBB structure in diabetes is not clearly defined [

31,

32,

33]. Type-2 diabetic patients have shown higher susceptibility to cerebrovascular disease and underlying defects are unknown. We and others have shown an increased BBB permeability very early in type-2 diabetic mice following ischemic injury [

6,

12,

34,

35]. In this study, we recorded signs of degenerating blood vessels along with loss of a tight junctional protein in the motor cortex and caudate of

db/db mice (

Figure 4 and

Figure 5). Similarly, Acharya et al reported a leak of plasma IgG in the cortex of the porcine model which was affected by diabetes and hypercholesterolemia from 6 months [

36].

In conclusion, the study suggests that constant elevated blood glucose in the diabetic mouse causes a milieu of subclinical inflammation, which leads to a reactive state of astrocytes and microglia in different brain regions, and the compromised state of the glial cell leads to increased BBB permeability. These defects may be the reason of impaired response and early glial cell death post ischemic insult in the diabetic brain. These data are insightful and may serve to understand the development of other neurodegenerative diseases and compromised recovery post CNS insult in growing diabetic populations.

Author Contributions

R.K.: Conceptualization, data analysis, and manuscript preparation. L.W.: Animal study, histology, editing of the manuscript. P.J.M.: Conceptualization, analysis, and manuscript preparation. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

No funding obtained for this study.

Institutional Review Board Statement

All the experimental procedures in this study were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee, College of Medicine, Penn State University under protocol number: # 201901187.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be available upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Chowen JA, Frago LM, Fernández-Alfonso MS. (2019)Physiological and pathophysiological roles of hypothalamic astrocytes in metabolism. J Neuroendocrinol.31(5):e12671. [CrossRef]

- Hammond BP, Manek R, Kerr BJ, Macauley MS, Plemel JR. (2021)Regulation of microglia population dynamics throughout development, health, and disease. Glia.69(12):2771-97. [CrossRef]

- Argente-Arizón P, Guerra-Cantera S, Garcia-Segura LM, Argente J, Chowen JA. (2017)Glial cells and energy balance. J Mol Endocrinol.58(1):R59-r71. [CrossRef]

- Alvarez JI, Katayama T, Prat A. (2013)Glial influence on the blood brain barrier. Glia.61(12):1939-58. [CrossRef]

- Li W, Roy Choudhury G, Winters A, Prah J, Lin W, Liu R, et al. (2018)Hyperglycemia Alters Astrocyte Metabolism and Inhibits Astrocyte Proliferation. Aging Dis.9(4):674-84. [CrossRef]

- Kumari R, Bettermann K, Willing L, Sinha K, Simpson IA. (2020)The role of neutrophils in mediating stroke injury in the diabetic db/db mouse brain following hypoxia-ischemia. Neurochem Int.139:104790. [CrossRef]

- Kumari R, Willing LB, Krady JK, Vannucci SJ, Simpson IA. (2007)Impaired wound healing after cerebral hypoxia-ischemia in the diabetic mouse. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab.27(4):710-8. [CrossRef]

- Kumari R, Willing LB, Patel SD, Krady JK, Zavadoski WJ, Gibbs EM, et al. (2010)The PPAR-gamma agonist, darglitazone, restores acute inflammatory responses to cerebral hypoxia-ischemia in the diabetic ob/ob mouse. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab.30(2):352-60. [CrossRef]

- Magistretti, PJ. (2006)Neuron-glia metabolic coupling and plasticity. J Exp Biol.209(Pt 12):2304-11. [CrossRef]

- Patel AB, Lai JC, Chowdhury GM, Hyder F, Rothman DL, Shulman RG, et al. (2014)Direct evidence for activity-dependent glucose phosphorylation in neurons with implications for the astrocyte-to-neuron lactate shuttle. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A.111(14):5385-90. [CrossRef]

- Chavda V, Yadav D, Patel S, Song M. (2024)Effects of a Diabetic Microenvironment on Neurodegeneration: Special Focus on Neurological Cells. Brain Sci.14(3). [CrossRef]

- Kumari R, Willing LB, Patel SD, Baskerville KA, Simpson IA. (2011)Increased cerebral matrix metalloprotease-9 activity is associated with compromised recovery in the diabetic db/db mouse following a stroke. J Neurochem.119(5):1029-40. [CrossRef]

- Kareem ZY, McLaughlin PJ, Kumari R. (2023)Opioid growth factor receptor: Anatomical distribution and receptor colocalization in neurons of the adult mouse brain. Neuropeptides.99:102325. [CrossRef]

- Kumari R, Kareem ZY, McLaughlin PJ. (2023)Acute Low Dose Naltrexone Increases β-Endorphin and Promotes Neuronal Recovery Following Hypoxia-Ischemic Stroke in Type-2 Diabetic Mice. Neurochem Res. [CrossRef]

- O'Brien J, Hayder H, Peng C. (2016)Automated Quantification and Analysis of Cell Counting Procedures Using ImageJ Plugins. J Vis Exp(117). [CrossRef]

- Vannucci SJ, Maher F, Simpson IA. (1997)Glucose transporter proteins in brain: delivery of glucose to neurons and glia. Glia.21(1):2-21. [CrossRef]

- Zhang L, Nair A, Krady K, Corpe C, Bonneau RH, Simpson IA, et al. (2004)Estrogen stimulates microglia and brain recovery from hypoxia-ischemia in normoglycemic but not diabetic female mice. J Clin Invest.113(1):85-95. [CrossRef]

- Damanik J, Yunir E. (2021)Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus and Cognitive Impairment. Acta Med Indones.53(2):213-20.

- Serlin Y, Levy J, Shalev H. (2011)Vascular pathology and blood-brain barrier disruption in cognitive and psychiatric complications of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Cardiovasc Psychiatry Neurol.2011:609202. [CrossRef]

- McCall, AL. (1992)The impact of diabetes on the CNS. Diabetes.41(5):557-70. [CrossRef]

- Bahniwal M, Little JP, Klegeris A. (2017)High Glucose Enhances Neurotoxicity and Inflammatory Cytokine Secretion by Stimulated Human Astrocytes. Curr Alzheimer Res.14(7):731-41. [CrossRef]

- Bélanger M, Allaman I, Magistretti PJ. (2011)Brain energy metabolism: focus on astrocyte-neuron metabolic cooperation. Cell Metab.14(6):724-38. [CrossRef]

- Kaminsky N, Bihari O, Kanner S, Barzilai A. (2016)Connecting Malfunctioning Glial Cells and Brain Degenerative Disorders. Genomics Proteomics Bioinformatics.14(3):155-65. [CrossRef]

- Volterra A, Meldolesi J. (2005)Astrocytes, from brain glue to communication elements: the revolution continues. Nat Rev Neurosci.6(8):626-40. [CrossRef]

- Liu D, Smith CL, Barone FC, Ellison JA, Lysko PG, Li K, et al. (1999)Astrocytic demise precedes delayed neuronal death in focal ischemic rat brain. Brain Res Mol Brain Res.68(1-2):29-41. [CrossRef]

- Colonna M, Butovsky O. (2017)Microglia Function in the Central Nervous System During Health and Neurodegeneration. Annu Rev Immunol.35:441-68. [CrossRef]

- Li Y, Jiang T, Du M, He S, Huang N, Cheng B, et al. (2023)Ketohexokinase-dependent metabolism of cerebral endogenous fructose in microglia drives diabetes-associated cognitive dysfunction. Exp Mol Med.55(11):2417-32. [CrossRef]

- Lin L, Basu R, Chatterjee D, Templin AT, Flak JN, Johnson TS. (2023)Disease-associated astrocytes and microglia markers are upregulated in mice fed high fat diet. Sci Rep.13(1):12919. [CrossRef]

- Cope EC, LaMarca EA, Monari PK, Olson LB, Martinez S, Zych AD, et al. (2018)Microglia Play an Active Role in Obesity-Associated Cognitive Decline. J Neurosci.38(41):8889-904. [CrossRef]

- Hao S, Dey A, Yu X, Stranahan AM. (2016)Dietary obesity reversibly induces synaptic stripping by microglia and impairs hippocampal plasticity. Brain Behav Immun.51:230-9. [CrossRef]

- Hovsepyan MR, Haas MJ, Boyajyan AS, Guevorkyan AA, Mamikonyan AA, Myers SE, et al. (2004)Astrocytic and neuronal biochemical markers in the sera of subjects with diabetes mellitus. Neurosci Lett.369(3):224-7. [CrossRef]

- Dai J, Vrensen GF, Schlingemann RO. (2002)Blood-brain barrier integrity is unaltered in human brain cortex with diabetes mellitus. Brain Res.954(2):311-6. [CrossRef]

- Horani MH, Mooradian AD. (2003)Effect of diabetes on the blood brain barrier. Curr Pharm Des.9(10):833-40. [CrossRef]

- Dietrich WD, Alonso O, Busto R. (1993)Moderate hyperglycemia worsens acute blood-brain barrier injury after forebrain ischemia in rats. Stroke.24(1):111-6. [CrossRef]

- Kamada H, Yu F, Nito C, Chan PH. (2007)Influence of hyperglycemia on oxidative stress and matrix metalloproteinase-9 activation after focal cerebral ischemia/reperfusion in rats: relation to blood-brain barrier dysfunction. Stroke.38(3):1044-9. [CrossRef]

- Acharya NK, Levin EC, Clifford PM, Han M, Tourtellotte R, Chamberlain D, et al. (2013)Diabetes and hypercholesterolemia increase blood-brain barrier permeability and brain amyloid deposition: beneficial effects of the LpPLA2 inhibitor darapladib. J Alzheimers Dis.35(1):179-98. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).