1. Introduction

Fujian Tulou, the primary residence for the Hakka people in Fujian for centuries, is a village that features rich natural resources and cultural heritage that integrate with the surrounding environment. These factors drive elderly people to age in place in their ancestral homes. The western region of Fujian Province is home to Tulou Villages. However, with the outflow of young labor, the declining birth rates, and longer life expectancies, the Tulou Villages are facing a severe aging population problem, bringing many challenges to age in place. The outdoor environment of Tulou Village serves as a critical support for aging in place, while the neighborhood open spaces (NOSs) [

1], as the core space for fostering village cohesion, is the central spatial resource for activities and interactions within the Tulou Village. Therefore, studying the age-friendly renewals of Tulou Villages NOSs is a significant topic. By researching the behavioral characteristics and needs profile of the elderly in Fujian Tulou Village NOSs, we can better understand their actual needs in these spaces. The government and designers can also use this as a basis to fully leverage the existing resource advantages of Tulou Villages, thereby promoting the development of age-friendly outdoor environments in Tulou Villages.

The behaviors of elderly people are influenced not only by physiological and psychological characteristics but also by various factors such as culture, built environment. There has been considerable research on the behavioral characteristics of elderly people. In the field of elderly behavior studies, Zhang Z. Q. et al. based on the gathering behavior patterns of elderly people in rural China, used behavior mapping to identify two kinds of aggregation phenomena in rural public spaces [

2]. Li B., Wang Y., and Li X. conducted observations and interviews with elderly residents in three village environments in Shanghai, using cluster analysis to reveal the characteristics and influencing factors of elderly walking behavior, also explore the relationship between walking behavior and the environment [

3]. Ren W. M. and Zhang X. C. analyzed the current state of elderly behavior patterns and spatial needs to explore age-friendly renewal strategies for the open space in the Cave Dweling Villages of Lüliang City [

4]. Xiao J. et al. integrated space syntax and cognitive surveys to establish an evaluation framework for the “publicness” of rural NOSs. He then used this framework to analyze elderly behavior patterns and the mechanisms influencing publicness [

5]. Basu R. and Sevtsuk A. explored pedestrian behavior preferences across various route attributes in Boston, Massachusetts, using a large GPS trajectory dataset [

6]. These studies focus on various aspects of elderly behavior, such as specific behaviors and behavior patterns. In terms of the factors influencing elderly behavioral characteristics, Qu Y. used a behavioral observation method to investigate the temporal and spatial characteristics of elderly leisure behavior across the four seasons in Shenyang Baicao Park. The study analyzed the impact of seasonal climate factors on elderly leisure behavior and, based on these findings, proposed spatial optimization design strategies for open parks in northern cities [

7]. Cai Y. Q. and Wang Y. M. conducted observations and interviews to study the behavioral characteristics of elderly people in residential streets during the winter in Shanghai, as well as the use of street space. They revealed the usage patterns of street spaces by the elderly [

8]. He S. Y. et al. approached the study from the perspective of villagers’ spatial behavior, using the comparative case study method combined with the questionnaire survey and the depth interview. They explored the impact of built environment elements on villagers’ spatial behavior [

9]. Liu C et al. based on survey data from rural China, found that family clan culture can reduce depressive behaviors in elderly people, with this effect being independent of gender [

10]. Mika Moran et al. conducted a literature review to identify five physical environmental factors that influence elderly physical activity. She then used qualitative methods to determine the most relevant factors [

11]. Xu, Hong-Chao et al. used qualitative research methods to analyze the elderly behavior characteristics in NOSs within urban communities in Wuhan. The factors influencing elderly behavior were categorized into two types: objective factors and subjective factors [

12]. Tanja Schmidt et al. conducted field survey to investigate the characteristics of village open spaces, and then evaluated the relationship between the identified characteristics and elderly social interactions and walking behaviors [

13]. Koo, B. W. et al. applied computer vision technology to quantify street-level factors in street view images from Atlanta, Georgia. He examined how these factors relate to walking behavior patterns [

14]. The above studies examine how climate, culture, and physical environments influence behavior of the elderly.

The elderly needs in public spaces are diverse, influenced by a variety of factors. Senetra, A. et al. conducted a study comparing elderly needs in “age-friendly housing communities” across different countries. The research found that while there were some variations in needs based on age and gender, cultural habits had a significant influence on the elderly needs [

15]. Li J. Q. first identified the public space demand factors for the elderly population in nursing institutions in Nanjing through standard and standardized research, as well as interview studies. Then, using the segmented KANO Model, she prioritized the elderly’s needs in public spaces [

16].Wan Ziliang et al. through a field survey of the NOSs in an old community in Beijing, analyzes the outdoor activity needs of the elderly and the age-friendliness of the built environment in the NOSs [

17].Wang Huanhuan et al. through questionnaires and interviews, analyzed the needs of elderly individuals with varying levels of physical ability in Hainan Century Park, proposing urban public space renovation strategies to accommodate these varying needs [

18].Zhang, H. et al. used the grounded theory approach, conducted interviews with elderly residents in four residential communities in China. The study analyzed their preferences regarding the acoustic needs of the community outdoor environment [

19]. Lim, X. J. et al. conducted interviews with elderly residents in Ipoh, Malaysia, using a semi-structured questionnaire to explore the unmet needs of the elderly. The study analyzed these unmet needs from multiple levels using the Active Aging 5P framework [

20].

As the studies show, existing research mainly focuses on urban elderly communities, elderly care facilities, and urban parks, with limited studies on rural areas, especially cultural heritage villages. In addition, most research targets specific elderly behaviors, such as social leisure and physical health, and lacks a comprehensive understanding of elderly behavior throughout the day. From the above studies, it is clear that existing research on the needs of the elderly in public spaces primarily focuses on urban elderly populations, with a primary emphasis on public spaces within elderly communities, nursing home public spaces, and age-friendly parks. Research on NOSs in rural areas, particularly in villages, is relatively scarce.

Based on the in-depth analysis above, this research primarily has three objectives and three significances. The objectives are as follows:1) To collect behavioral data of the elderly in Taxia Village NOSs, analyze and construct an assessment model for the behavioral activity of the elderly in the NOSs, and identify high-activity NOSs; 2) To collect and refine both behavioral and needs data of the elderly in Taxia Village within high-activity NOSs, and to analyze their behavioral characteristics and needs profile using a mixed-methods approach; 3) Based on the findings, to propose recommendations for the age-friendly renewals in Fujian Tulou Village NOSs, promoting the development of elderly-friendly outdoor environments in these villages. The significance of this research is as follows:1) Exploring the behavioral characteristics and needs profile of the elderly in Taxia Tulou Village NOSs, enriching research on elderly behavior and needs theory in specific cultural and regional contexts; 2)Providing some theoretical references for local governments in formulating age-friendly renovation policies and for design companies involved in age-friendly renewals; 3) Enhancing public awareness of the behaviors and needs of the elderly, promoting the shift from “elderly care” to “elderly inclusion” mindset, and advancing the development of an elderly-friendly and positive aging rural environment.

2. Research scope, research methodology and data collection

2.1. Research scope

The object of this study is Taxia Village, located in Nanjing County, Fujian Province, China. The village is divided into Area A and Area B (

Figure 1). The villagers in both areas belong to the same Zhang family clan. The village is surrounded by mountains on three sides and is built along a river, with a well-preserved spatial layout. As of October 2023, the registered population of the village is 1,436, with a permanent population of approximately 500, including 285 elderly individuals aged 60 and above. The research focuses on elderly individuals aged 60 and above in Taxia Village, specifically independent elderly and device-aided elderly, with the term “elderly” referring to this group throughout the text. The preliminary research scope includes all NOSs in the village, defined as outdoor open spaces within the village boundaries where public activities and interactions occur. By collecting behavioral data on the elderly in these spaces, the study analyzes their behavioral activity levels. High-activity NOSs are then identified as the primary research subject, forming the study’s focus. In this study, “the elderly” refer to these two groups. The scope of the research object is Taxia Village NOSs. Taxia Village was selected for two main reasons: first, it is a typical representative of Fujian Tulou Village. Second, the architecture and layout of the NOSs are well-preserved.

2.2. Research Methodology

Data Collection Phase:1) Preliminary research phase: The purpose of this phase has three main objectives. First, it aims to investigate the current status in Taxia Village NOSs, analyze the activity patterns of the elderly, and collect behavioral data on the elderly in these NOSs. Second, it involves collecting and analyzing the assessment factors for the Behavioral Activity Level of the Elderly in NOSs, in order to construct an assessment model for the Behavioral Activity Level. Third, it aims to assess the Behavioral Activity Level of the Elderly in NOSs and define the scope of the research areas. To achieve these objectives, we begin by collecting current information on the layout, functions, and quantity of NOSs in Taxia Village through literature review, field surveys, and drone aerial photography. Next, we use semi-structured interviews and field observations to collect data on the daily movement patterns of the elderly in Taxia Village, determining the appropriate time for collecting behavioral data in NOSs. We also use the non-participatory photography method to capture behavioral data on elderly individuals throughout the day, thereby establishing the Taxia Village elderly NOSs behavior database, DATE1. Finally, we determine the assessment indicators for the Behavioral Activity Level of the Elderly in NOSs through literature review and field research, and use these to construct an assessment model for the elderly’s behavioral activity level in these spaces. 2) In-depth research phase: The purpose of this phase is to collect behavioral data and spatial needs of the elderly in the NOSs. To achieve this, we first use the on-site counting method combined with the non-participatory photography method to collect behavioral data of the elderly in NOSs with a high behavioral activity level throughout the day, thereby establishing the Taxia Village elderly NOSs behavior database, DATE2. Next, we employ field surveys, literature review, and the KANO questionnaire method to collect and filter the elderly’s diverse needs regarding NOSs, and then classify these diverse needs into categories.

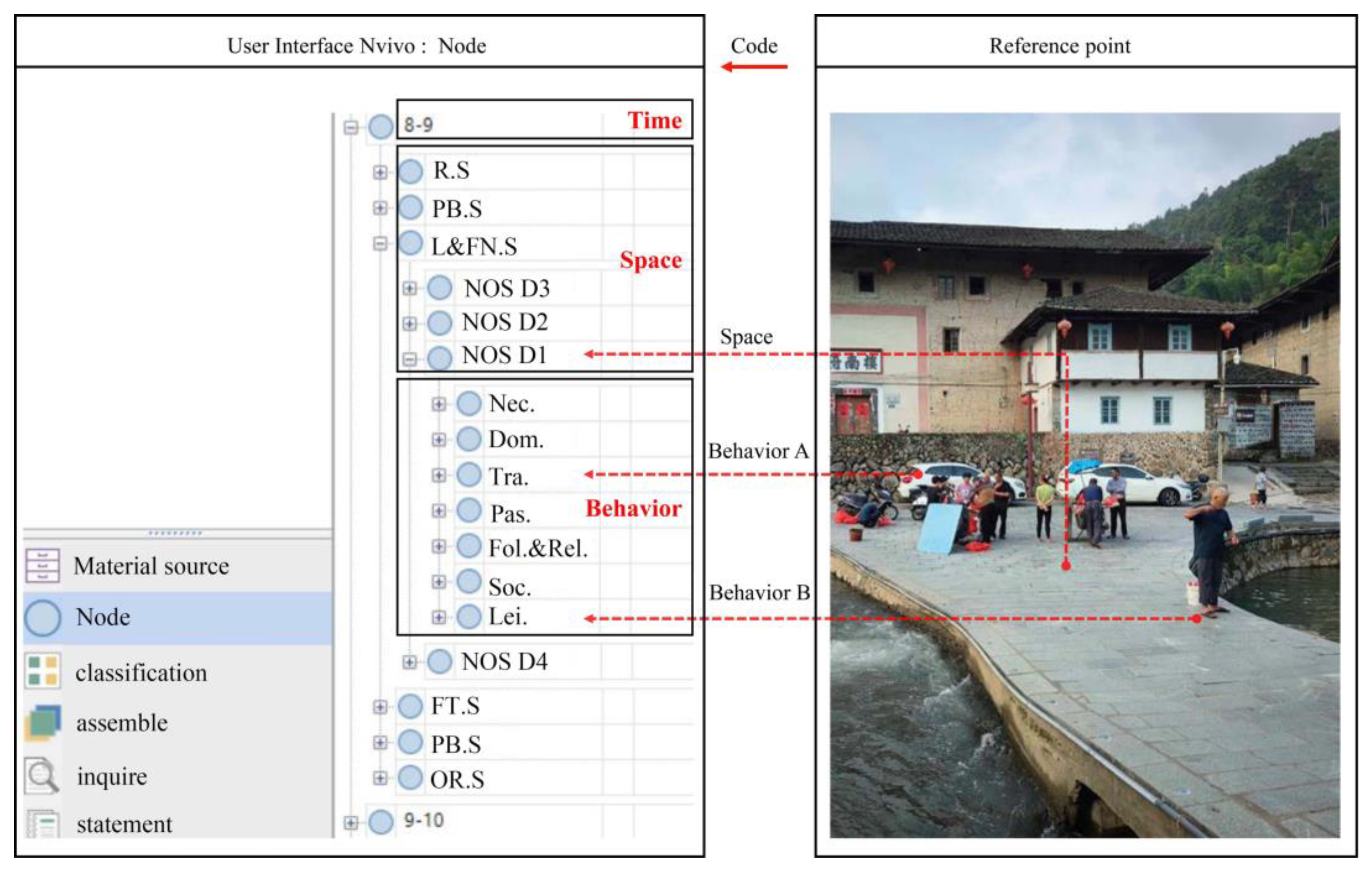

Data Analysis Phase:1) Assessment of the ehavioral Activity Level of the Elderly in NOSs: First, based on the behavioral data of the elderly in NOSs collected during the preliminary research phase and the constructed assessment model for the Behavioral Activity Level of the Elderly in NOSs, we use this model to assess the behavioral activity level of the elderly in each space. Then, NOSs with a high behavioral activity level are selected as the focus of further study. 2) Behavioral characteristics analysis: First, we used Nvivo software to code the daily behavioral data of the elderly in the NOSs with high behavioral activity levels, collected on two separate occasions. Then, we calculated the average values of the coded behavioral data and used Nvivo software and Excel to generate visual charts. Finally, we analyzed the behavioral characteristics through these visual charts. (3) Needs profile analysis: First, we use KANO Model to filter and classify the diverse elderly needs in NOSs. Then, we analyze the types of needs the elderly have in these spaces. Lastly, we apply the AHP (Analytic Hierarchy Process) method to evaluate the importance of the different needs of the elderly in NOSs and analyze the importance of these needs.

2.3. Data collection

2.3.1. Survey of the NOSs and behavior coding of the elderly in Taxia Village

We aim to collect data on the current state in Taxia Village Area A NOSs and Area B NOSs, as well as the behavioral data of the elderly in these spaces. Since Fujian Tulou is located in a tropical monsoon climate region, characterized by warm winters and cool summers, we have selected spring and summer as the representative seasons for data collection. The goal is to obtain comprehensive behavioral data.

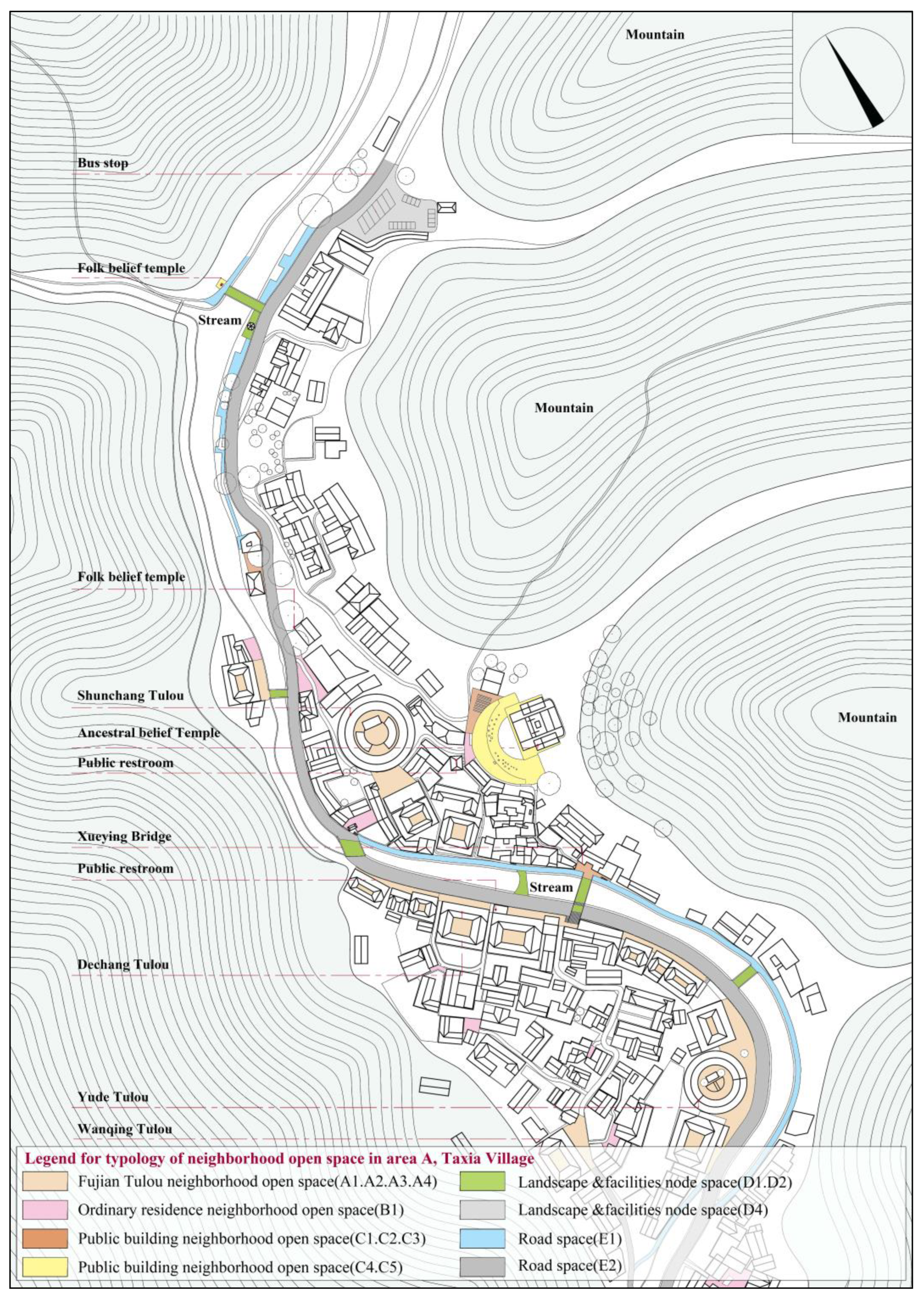

The preliminary research was conducted during the spring season, from April 1, 2024, to April 7, 2024. First, we compiled and analyzed Taxia Village NOSs through literature review and field survey. And based on architectural typology theory [

21], we classified the NOSs, the results are shown in

Figure 2. At the same time, we used the non-participatory photography method to record the behavioral activities of the elderly in the village, with data collected from 6:00 AM to 9:00 PM. Additionally, Semi-structured interviews were conducted to understand the daily travel patterns of the elderly. Also, the interviews focused on collecting information such as the respondents’ daily travel times and the types of activities they engage in at the NOSs. A total of 230 questionnaires were distributed, and 217 were returned. Next, we statistically analyzed the collected photos and questionnaire data and created the “Daily NOSs behavior-time correspondence chart (abbreviated as, i.e., A-t Chart).” Considering the comprehensiveness of data collection and operational feasibility, in this study, we defined one hour as a time cutoff to record the daily travel patterns of the elderly, collecting data every hour. Based on the activity patterns observed in the A-t chart, we excluded the low-activity time cutoffs of 12:00–14:00 and 19:00–21:00. The following time segments were selected for collecting behavioral data of the elderly in the NOSs: 6:00–7:00, 7:00–8:00, 8:00–9:00, 9:00–10:00, 10:00–11:00, 11:00–12:00, 14:00–15:00, 15:00–16:00, 16:00–17:00, 17:00–18:00, and 18:00–19:00. Meanwhile, based on field surveys and questionnaires, we assessed the usage of NOSs and created layout map of NOSs in Taxia Village Area A (

Figure 3), and Taxia Village Area B (

Figure 4). Finally, we used Nvivo software to code the photos of elderly behaviors in NOSs that were collected. The behavioral coding diagram is shown in

Figure 5. Based on the statistical data from the questionnaire interviews, observations, and photographs, and referring to the works of Gillian [

22] and Li B [

23], we classified the 36 types of elderly behaviors in Taxia Village NOSs into seven categories: leisure behavior, social behavior, passive observation behavior, transaction behavior, necessary behavior, domestic work behavior, and folk customs and religious behavior, as shown in

Table 1.”leisure behavior” refers to activities that elderly individuals engage in freely to achieve physical and mental pleasure and relaxation. It is divided into three subcategories: Exercising, hobbies and interests, and entertainment. “Social behavior” refers to activities through which elderly individuals participate in community life. This is divided into two subcategories: neighborhood interaction and group activities. “Passive observation behavior” refers to static behaviors such as daydreaming, observing, and taking short rests. This category is divided into two subcategories: rest and observation.” Transaction behavior” refers to activities related to the buying and selling of goods or services in the daily life of elderly individuals. This is divided into two subcategories: Buying and selling and lifestyle services.” Domestic work behavior” refers to activities where elderly individuals share household responsibilities, such as look after children, cleaning, and prepare the vegetables. This is divided into two subcategories: Looking after and physical labor. “Folk customs and religious behavior” refer to behaviors related to the customs and folk beliefs of Fujian Tulou Village. This is divided into two subcategories: Belief and traditional customs.

2.3.2. Assessment of the behavioral activity level and definition of the research scope

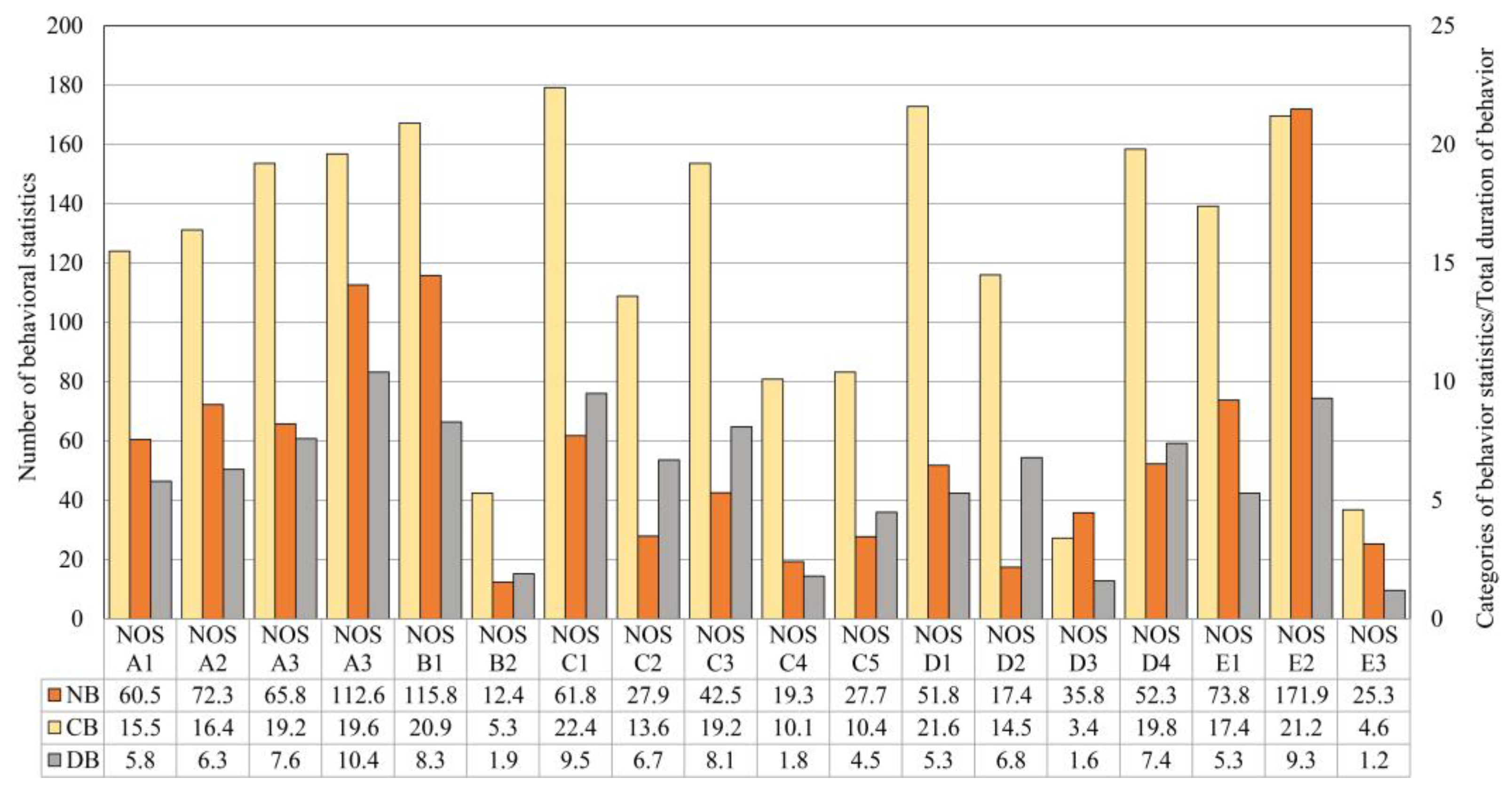

Through literature review, field research, we introduce three assessment indicators to assess the Behavioral Activity Level of the Elderly in NOSs (denoted as P): Space Usage Frequency (denoted as P

1), Spatial Function Complex Degree (denoted as P

2), and Space Usage Time Ratio (denoted as P

3) [

24,

25]. Specifically, P

1 is calculated as the ratio of the Number of Behavioral Statistics (denoted as NB) within a space during a day to the total number of behavioral statistics across all spaces. P

2 is calculated as the ratio of the Categories of Behavior Statistics (denoted as CB) within a space to the total number of behavior category across all spaces (a total of 36 categories). P

3 is calculated as the ratio of the Total Duration of Behavior (denoted as DB) within a space to the total time (a total of 11 hours) during which behavior data was collected. Therefore, P equals the sum of P

1, P

2, and P

3. In other words,

where k

1,k

2,k

3 are the weight coefficients for the three indicators. In this study, we assume that the weights for the three indicators are equal in evaluating the Behavioral Activity Level of the Elderly in NOSs, thus assigning

.

The data collection for this study took place from April 6 to April 20, 2024, during the spring season. First, we divided the research team into two groups, each consisting of four members, with each group responsible for one of the two areas. Based on the layout map of Taxia Village NOSs, we employed the on-site counting method combined with the non-participatory photography method. During the pre-determined time segments, we collected data on the elderly’s behavioral activities every hour, resulting in the creation of the elderly NOSs behavior database DATE1. Next, we used Nvivo software to code the data of the elderly in different NOSs. We then calculated the average values of the three assessment indicators over the fifteen-day from April 6, 2024, to April 20, 2024. The statistical results shown in

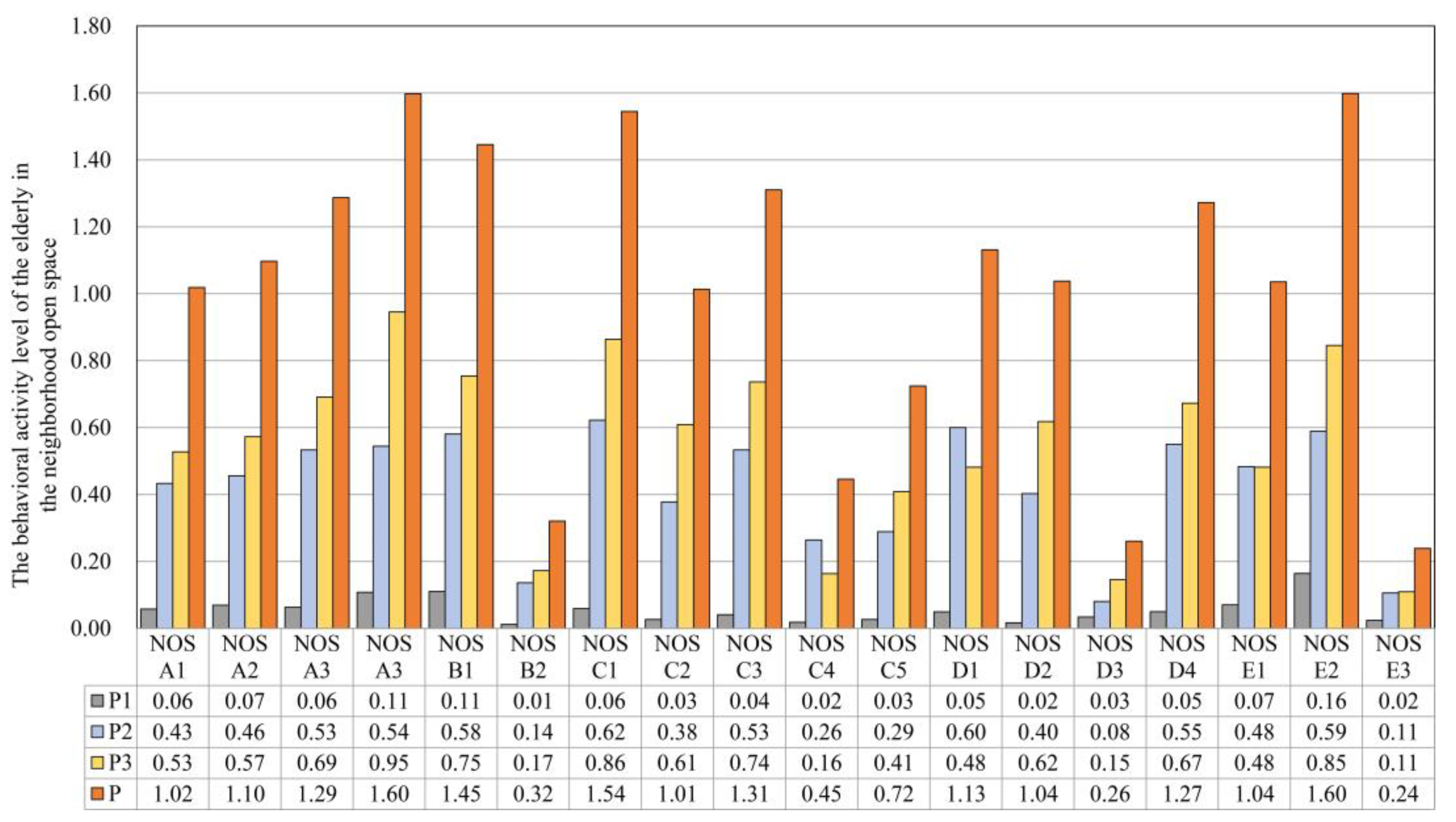

Figure 6. Finally, the behavioral activity level of the elderly in each space was calculated using the assessment model. The assessment results are shown in

Figure 7. The results indicate that P

1, P

2, and P

3 were relatively low in the farm green space, village parking lot, and pedestrian streets, and P remained consistently low in these spaces. Although the elderly behavioral activity level in the external space of the ancestral temple and folk belief spaces was low overall, their values were higher during special festivals. Additionally, some road spaces consistently exhibited low behavioral activity level of the elderly. Therefore, this study excluded the farm green space, village parking lot, and pedestrian streets, as well as sections of the waterfront walkway and mixed-use traffic, and focused on the remaining NOSs. The study area is shown in

Figure 8 and

Figure 9.

2.3.3. Assessment of the behavioral activity level and definition of the research scope

The data collection for this study took place during the summer, from July 1, 2024, to July 15, 2024. Similarly, we divided the research team into two groups, each consisting of four members, with each group responsible for one of the two areas. Based on the layout map of Taxia Village NOSs, we employed the on-site counting method combined with the non-participatory photography method. Behavioral activity data of the elderly was collected at designated time intervals, with data being recorded every hour, resulting in the elderly NOSs behavioral database DATE2.Additionally, we coded the recorded behavioral data of the elderly individually by using Nvivo software. It is important to note that, on the one hand, to minimize the impact of data collection on the elderly’s behavior, each research group was assigned one member who was required to accurately record the elderly’s activities in the NOSs. On the other hand, to reduce the influence of factors such as the randomness of the elderly’s travel activities and seasonal variations, the behavioral data collected from the highly active NOSs in both rounds were separately coded and then integrated. This approach allowed for the maximization of data collection and utilization, thereby facilitating a better understanding of the elderly’s behavioral characteristics in specific time periods and in highly active NOSs.

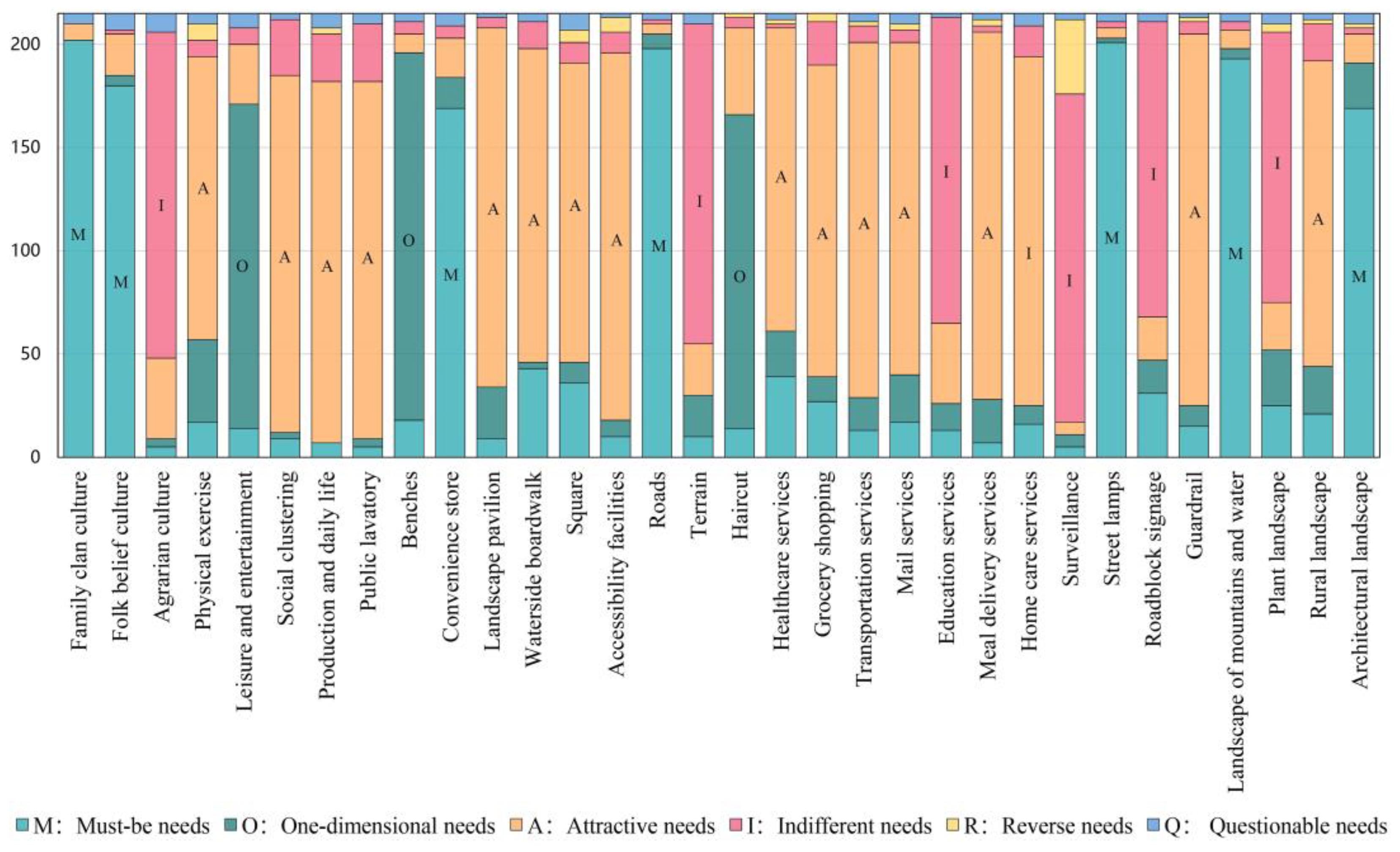

2.3.4. Collection and sorting of the elderly’s needs in the NOSs

Research on the needs profile of the elderly in Fujian Tulou Village NOSs: The key focus is on the categories and the importance of needs. Therefore, we first need to collect data on the categories of the elderly needs in these NOSs, and then further assess their importance. We initially selected 32 types of needs of the elderly in the NOSs through questionnaire interviews, field surveys, and literature research. Based on the attributes of these needs, we consolidated them into 7 categories, referred to as primary needs, with the 32 specific needs categorized as secondary needs, as shown in

Table 3. We then applied the KANO Model to further select and sort these needs. Then, we conducted a second round of sorting and classification of these needs using the KANO Model. Currently, there is no unified standard for categorizing the elderly’s needs in the research field. Therefore, based on the original questionnaire data, this study uses the KANO Model to sort out the associated factors that do not affect the subsequent evaluation of NOSs needs. The KANO Model, proposed by Noriaki KANO, categorizes people’s needs for a product or service into five types: must-be needs, one-dimensional needs, attractive needs, indifferent needs, and reverse needs [

26]. In this study, the KANO categories of the elderly’s needs for Taxia Village NOSs are as follows: 1) Must-be needs: These are the needs that must be considered when evaluating the elderly’s needs for the NOSs. While satisfying these needs may not necessarily increase satisfaction, their absence would cause significant inconvenience and even be intolerable for the elderly. 2)One-dimensional needs: These are the types of needs that the elderly expects to fulfill in NOSs. Fulfilling these needs will lead to satisfaction for the elderly.3) Attractive needs: These are unexpected needs that surprise and delight the elderly. Fulfilling these needs can significantly improve the elderly’s needs satisfaction with the NOSs.4) Indifferent needs: These are needs that the elderly does not focus on. Whether or not these needs are met has little impact on the elderly.5) Reverse needs: These are needs that the elderly does not want to have. The specific approach is as follows: First, a questionnaire on the elderly’s needs for the NOSs was designed based on the KANO Model, using 32 factors that had been preliminary selected as the survey questions. Each factor was asked in both positive and negative forms, with answer options as shown in in

Table A1. Each question has a fixed set of response combinations, and each combination corresponds to a specific KANO category. The KANO categories were designed based on these response combinations, as shown in

Table A2. The categories are as follows: “M” represents must-be needs, “O” represents one-dimensional needs, “A” represents attractive needs, “I” represents indifferent needs, “R” represents reverse needs, and “Q” represents questionable needs (needs that are unclear or uncertain to the elderly). The questionnaire survey was conducted from July 16, 2024, to July 25, 2024. The survey targeted elderly individuals aged 60 and above in Taxia Village, including both independent and device-aided elderly residents. A total of 228 questionnaires were distributed, with all 215 being valid. In practice, a combination of interviews and questionnaires was used to inquire about and discuss each question in the survey. The questionnaires were then organized, and according to the KANO evaluation table, the needs of each elderly participant for the 32 factors were counted. For each factor, the total number of responses in each KANO category was tallied, and the category with the highest count was determined to be the final classification for that factor.

Table 2.

The preliminary selected list of elderly needs in the NOSs.

Table 2.

The preliminary selected list of elderly needs in the NOSs.

| Number |

Primary needs |

Secondary needs |

Contents |

| 1 |

Cultural Characteristics |

Family clan culture |

Ancestor worship |

| 2 |

Folk belief culture |

Folk deity worship |

| 3 |

Agrarian culture |

Agricultural and tea culture |

| 4 |

Functionality |

Physical exercise |

Exercise equipment venues |

| 5 |

Leisure and entertainment |

Chess and card leisure venues |

| 6 |

Social clustering |

Social clustering venues |

| 7 |

Production and daily life |

Production and daily life venues |

| 8 |

Facilities |

Public restroom |

Outdoor activity use |

| 9 |

Bench |

Rest and stay |

| 10 |

Convenience store |

Daily shopping |

| 11 |

Landscape pavilion |

Rest and sightseeing |

| 12 |

Waterside boardwalk |

Strolling |

| 13 |

Square |

Group activities |

| 14 |

Accessibility |

Accessibility facilities |

Ramp handrails |

| 15 |

Road |

Safe passage routes |

| 16 |

Terrain |

Flat or steep |

| 17 |

Elderly Services |

Haircut |

Barbershop |

| 18 |

Healthcare services |

Health clinic |

| 19 |

Grocery shopping |

Small vegetable market |

| 20 |

Transportation services |

Bus stop |

| 21 |

Mail services |

Express delivery station |

| 22 |

Education services |

Calligraphy and painting |

| 23 |

Meal delivery services |

Affordable nutritious meals |

| 24 |

Home care services |

Providing daily living services |

| 25 |

Safety |

Surveillance |

Security monitoring |

| 26 |

Street lamps |

Night lighting |

| 27 |

Roadblock signage |

Safety Tips |

| 28 |

Guardrail |

Protective measures |

| 29 |

Landscape |

Landscape of mountains and water |

Stream pond and mountain |

| 30 |

Plant landscape |

Flora |

| 31 |

Rural landscape |

Farm garden |

| 32 |

Architectural landscape |

Traditional Hakka architecture |

4. Discussion

This study primarily examines the behavioral characteristics and needs profile of the elderly in Fujian Tulou Village NOSs. Secondly, it provides theoretical references for age-friendly renewals of these spaces based on the behavioral characteristics and needs profile of the elderly. Additionally, the study proposes design recommendations for renewing NOSs, addressing common issues observed across these spaces.

Before discussing the socio-cultural environmental factors influencing the behavioral characteristics and needs profile of the elderly in Fujian Tulou Village NOSs, we need to summarize the common features of Fujian Tulou Village NOSs. Through field surveys and literature review of several typical Fujian Tulou Village, the following common characteristics of NOSs can be identified:1) Organic and unified spatial layout: Fujian Tulou Village NOSs consist of both the orderly Tulou NOSs and the organically combined external Tulou NOSs. The Tulou NOSs is closely linked with the individual Tulou units, serving each Tulou settlement while connecting to the surrounding external space. The external Tulou NOSs are seamlessly integrated with the natural environment, while also flexibly organizing the functions of the external space of the Tulou, serving the entire family clan settlement. Tulou Villages NOSs blend well into the surrounding environment, taking into account the pros and cons of the natural environment and successfully uniting the whole family clan settlement;2) Reproduction of cultural thought and clan ideology: On one hand, the organization of Fujian Tulou NOSs not only aligns with the natural landscape but is also deeply influenced by traditional rites and feng shui concepts, thereby imbuing these spaces with a rich cultural atmosphere. On the other hand, due to the family-based living habits and defensive needs, families could only live and reproduce within a certain territorial range in the form of Tulou clusters. The distribution of Tulou settlements and the expansion of NOSs are directly influenced by the ideology of bloodline and clan. These spaces reflect the distribution of clans and the expansion of family lineages in spatial terms; [

31] 3) Continuity of place and community identity: As important living spaces, Fujian Tulou Village NOSs not only carry the collective functions and memories of generations, such as production, daily life, folk beliefs, and customs, but also profoundly reflect the core values of mutual support among clan members and community participation. These spaces maintain a significant level of vitality, representing the continuation of both place spirit and community identity. Next, we will first discuss the socio-cultural environmental factors that influence the behavioral characteristics and needs profile of elderly people, and then, based on the research findings and the common issues observed in NOSs, propose recommendations for the age-friendly renewals of these spaces.

4.1. The socio-cultural environmental factors influencing the behavioral characteristics and needs profile of the elderly

Fujian Tulou Village NOSs are not only physical spaces, but also carry strong place identity and cultural spirit. In these open spaces, such as courtyards, squares, and bridges, villagers engage in social interaction, mutual assistance, and the transmission of local traditions. Through shared activities and communication, the villagers develop a sense of belonging to the place. These activities are closely tied to the spaces that serve as cultural carriers, imbuing these spaces with spiritual significance. [

32] Field research indicates that in these spaces, elderly people exhibit a strong sense of community identity. They actively participate in belief-related management activities, following common cultural principles, and adhering to similar thought patterns and behavioral norms. [

33,

34]

Fujian Tulou is the primary form of residence for the Hakka people in Fujian. This housing style facilitates defense and mutual assistance, and it is the result of the interaction between cultural and geographical conditions. The close connection between individuals and the community, along with the rich folk belief activities, plays a crucial role in uniting the clan. Together, they create a friendly residential atmosphere and a family survival ethos based on mutual help. [

35] This culture of settlement and community identity is well-preserved, influencing the behavioral norms and needs characteristics of the elderly.

The Hakka people of Fujian migrated from the Central Plains to the western region of Fujian. The spatial forms of the Tulou villages they constructed, the architectural layouts, and the behaviors and psychology of the elderly are influenced by various factors, including Central Plains culture, the cultural characteristics formed through migration, and the natural and geographical environment of western Fujian. However, “clan” culture serves as the internal force driving the “social-cultural” dynamics within Fujian Tulou Village. The social order of the village, shaped by clan influence, profoundly affects the villagers’ thoughts and behavioral norms [

36].

4.2. Design recommendations for age-friendly update of the NOSs

Through field research on multiple typical Fujian Tulou Village, combined with the study of the behaviors and needs of the elderly in Taxia Village, we identified the following issues in Fujian Tulou Village NOSs:1) Underutilization of advantageous resources. Fujian Tulou Village possess natural environmental advantages, such as good air quality, water sources, and sound environment, all of which are potential elderly care resources for aging in place. Additionally, there is a strong clan culture among the elderly in these villages, with family members showing solidarity and mutual support, creating a strong community atmosphere. Moreover, the villages have abundant spatial resources, such as the Tulou NOSs. However, these advantageous resources have not been fully leveraged.2) Incomplete spatial functionality and poor senior-friendliness. Due to insufficient or outdated facilities, the functions of Fujian Tulou Village NOSs have not been fully realized, resulting in low behavioral activity level of the elderly.3) Inefficient facility layout, not considering elderly usage habits. The survey results indicate that the behavior patterns, behavior types, and spatiotemporal characteristics of the elderly in the Fujian Tulou Village have local-specific traits. These behaviors are influenced by factors such as culture, spatial form, elderly needs, and physical characteristics. Therefore, the layout of the facilities should be adjusted according to the behavior and needs of the elderly to improve convenience and comfort in their usage.4) Services cannot meet the diverse needs of the elderly. With improvements in living standards, the categories of elderly needs in the Fujian Tulou Village have become more diverse. However, the current services provided in the NOSs do not better meet the increasing and diversified elderly needs. Based on the identified issues in the NOSs and considering the behavioral characteristics and needs profile of the elderly in Taxia Village, we propose the following recommendations for the age-friendly renovation of the Fujian Tulou Village NOSs.

Micro-renovations should be made to the existing environment and spatial resources to better meet the needs of the elderly. In the Fujian Tulou Village, elderly people have a strong sense of family identity, with family members united and supportive, actively participating in community activities. This provides a solid foundation for the implementation of mutual aid elderly care [

37]. The “time bank” [

38] program can be introduced to encourage mutual assistance among the elderly and promoting active aging.

Based on the diverse behavior patterns and elderly needs, flexibly arrange the more frequently used NOSs. For example, integrate the Tulou front square and eaves spaces, and add necessary facilities for the elderly to meet their various activity needs. Space upgrading and facility layout should fully consider the usage habits of the elderly, such as seating arrangements that consider density, back support, and armrests. [

39] The design of accessible pathways should prioritize the actual needs and habits of the elderly.

The behavior of the elderly tends to cluster at multiple points. By analyzing the functions of these behavior clustering points, facility resources can be strategically allocated to best meet the needs of the elderly.

Add elderly service stations in underused spaces near clustering points in the NOSs, such as “convenience stores” or “bus stops.” These stations could offer services like meal delivery, haircuts, and health consultations, gradually improving the facility service network that increases social opportunities and enhances the well-being of the elderly [

41].

The NOSs can organize cultural activities led by elderly volunteers, such as small cultural classes, to spread excellent cultural traditions, thus enhancing the elderly’s self-identity and sense of belonging to the community [

41].

Following the priority of needs, the renewals should first focus on meeting the elderly’s needs for safety, convenient outdoor activities, and cultural identity. Second, enhance the comfort of the space, such as by adding benches and shade facilities. Lastly, improve transportation connectivity and design pleasant landscape elements to enhance the overall livability of the space.

Figure 1.

(a) The location of Fujian in China; (b) The location of Zhangzhou in Fujian Province; (c) The location of Taxia Village in Nanjing County.

Figure 1.

(a) The location of Fujian in China; (b) The location of Zhangzhou in Fujian Province; (c) The location of Taxia Village in Nanjing County.

Figure 2.

Survey and classification of the current status of Taxia Village NOSs.

Figure 2.

Survey and classification of the current status of Taxia Village NOSs.

Figure 3.

Layout map of NOSs in Taxia Village Area A.

Figure 3.

Layout map of NOSs in Taxia Village Area A.

Figure 4.

Layout map of NOSs in Taxia Village Area B.

Figure 4.

Layout map of NOSs in Taxia Village Area B.

Figure 5.

Behavioral coding diagram.

Figure 5.

Behavioral coding diagram.

Figure 6.

Average behavioral assessment indicators for the elderly (April 6, 2024 - April 20, 2024).

Figure 6.

Average behavioral assessment indicators for the elderly (April 6, 2024 - April 20, 2024).

Figure 7.

Average behavioral activity level of the elderly in the NOSs (April 6, 2024 - April 20, 2024).

Figure 7.

Average behavioral activity level of the elderly in the NOSs (April 6, 2024 - April 20, 2024).

Figure 8.

The distribution map of NOSs with a high behavioral activity level in Area A.

Figure 8.

The distribution map of NOSs with a high behavioral activity level in Area A.

Figure 9.

The distribution map of NOSs with a high behavioral activity level in Area B.

Figure 9.

The distribution map of NOSs with a high behavioral activity level in Area B.

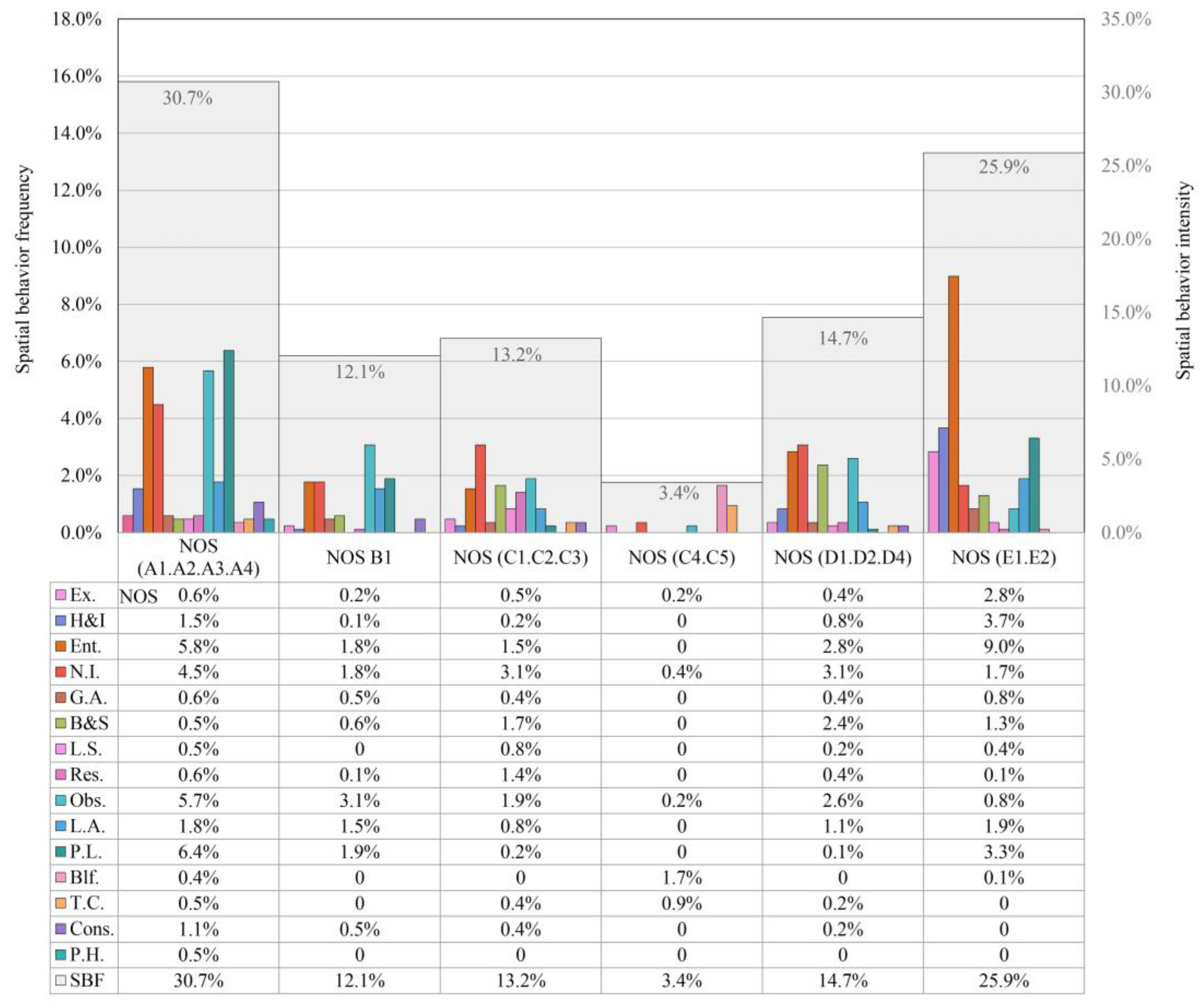

Figure 10.

Elderly’s average behavior frequency statistics chart from 30-day data sample.

Figure 10.

Elderly’s average behavior frequency statistics chart from 30-day data sample.

Figure 11.

Analysis of elderly behavior patterns.

Figure 11.

Analysis of elderly behavior patterns.

Figure 12.

Time-average instantaneous behavior frequency curve of the elderly from 30-day data sample.

Figure 12.

Time-average instantaneous behavior frequency curve of the elderly from 30-day data sample.

Figure 13.

The clustered bar chart of SBF for the primary NOSs from 30-day data sample.

Figure 13.

The clustered bar chart of SBF for the primary NOSs from 30-day data sample.

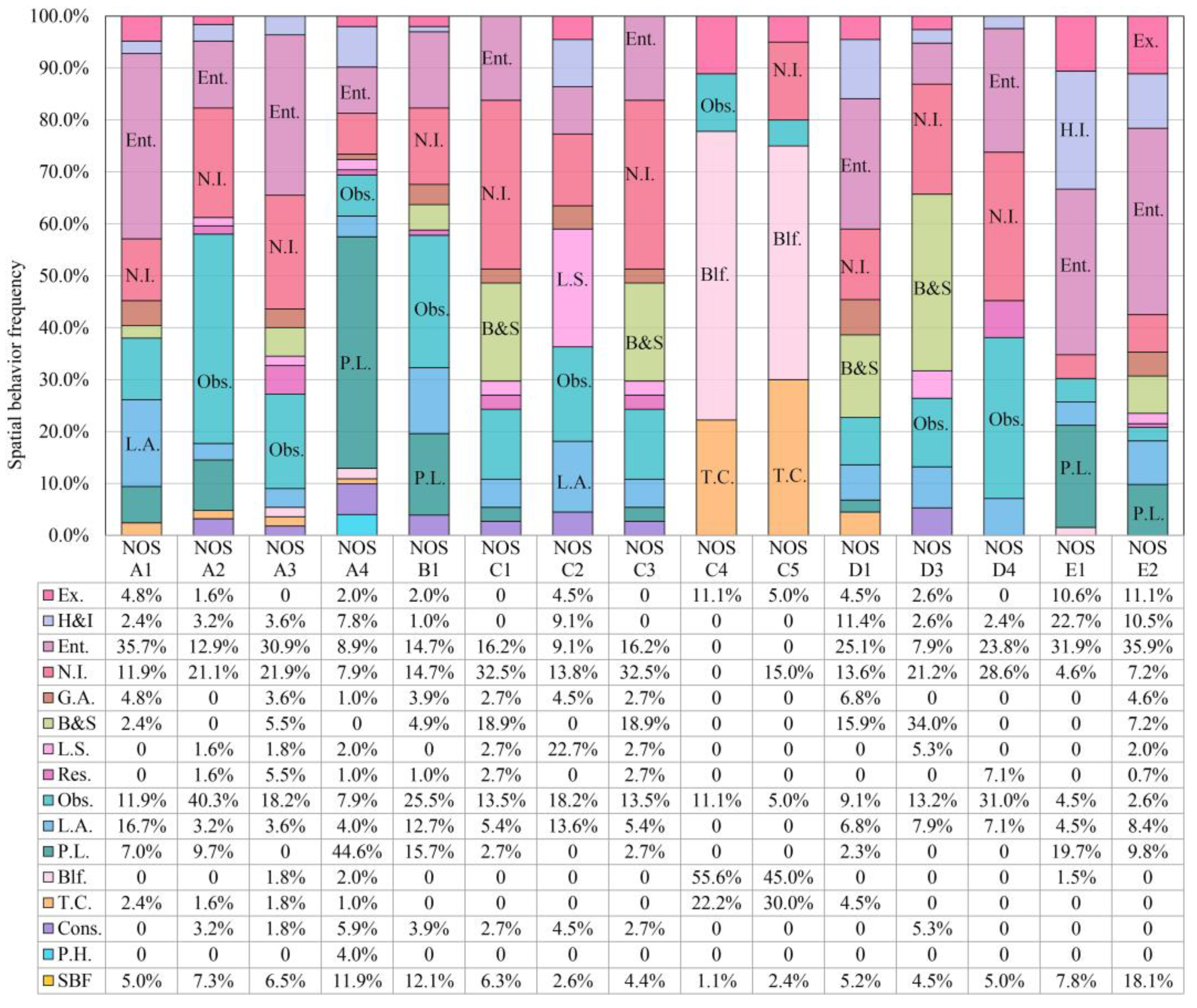

Figure 14.

The stacked bar chart of SBR for the secondary NOSs from 30-day data sample.

Figure 14.

The stacked bar chart of SBR for the secondary NOSs from 30-day data sample.

Figure 15.

Results of the KANO Model questionnaire survey on elderly needs in the NOSs.

Figure 15.

Results of the KANO Model questionnaire survey on elderly needs in the NOSs.

Table 1.

Behavioral classification of the elderly in Taxia Village NOSs.

Table 1.

Behavioral classification of the elderly in Taxia Village NOSs.

| Research Subjects |

Primary classification of behavior |

Secondary classification of behavior |

Content |

| Including elderly individuals aged 60 and above, both independent and device-aided types |

A. Leisure behavior (Lei.) |

A1. Exercising (Ex.) |

Walking |

| Cycling |

| A2. Hobbies and interests(H&I) |

Reading |

| Play an Instrument |

| Fishing |

| Net Fish |

| A3. Entertainment (Ent.) |

Play Chinese Chess and card |

| Play on the phone |

| Strolling |

| B. Social behavior (Soc.) |

B1. Neighborhood interaction (N.I.) |

Drink tea and chat |

| Gather and chat |

| B2. Group activities (G.A.) |

Group walking |

| Square dancing |

| C. Transaction behavior (Tra.) |

C1. Buying and selling(B&S) |

Grocery shopping |

| Selling local specialties |

| C2. Lifestyle services (L.S.) |

Mailing |

| Haircutting |

| See a doctor |

| D. Passive observation behavior (Pas.) |

D1. Rest (Res.) |

Take a short nap |

| Rest by the roadside |

| D2. Observation (Obs.) |

Enjoy the scenery |

| Watch others |

| E. Domestic work behavior (Dom.) |

E1. Looking after (L.A.) |

Look after children |

| Sun-dry crops |

| E2. Physical labor (P.L.) |

Washing |

| Prepare the vegetables |

| Cleaning |

| Grow vegetables |

F. Folk customs and religious behavior

(Fol. &Rel.) |

F1. Belief (Blf.) |

Ancestral belief |

| Folk belief |

| F2. Traditional customs (T.C.) |

Agricultural folk rituals |

| Marriage and funeral |

| G. Necessary behavior (Nec.) |

G1. Consuming (Cons.) |

Eating |

| Drinking |

| G2. Personal hygiene (P.H.) |

Wash face |

| Brush teeth |

Table 3.

Elderly needs list and weight calculation results after secondary sorting.

Table 3.

Elderly needs list and weight calculation results after secondary sorting.

| Number |

Evaluation Factor |

Criterion Layer Weight |

Evaluation Criteria |

Sub-Criterion Layer Weight |

Overall Weight |

| 1 |

Cultural Characteristics |

0.172 |

Family Clan Culture |

0.800 |

0.138 |

| 2 |

Folk belief culture |

0.200 |

0.034 |

| 3 |

Functionality |

0.341 |

Physical exercise |

0.150 |

0.051 |

| 4 |

Leisure and entertainment |

0.309 |

0.105 |

| 5 |

Social clustering |

0.435 |

0.148 |

| 6 |

Production and daily life |

0.106 |

0.036 |

| 7 |

Facilities |

0.107 |

Public restroom |

0.132 |

0.014 |

| 8 |

Benches |

0.442 |

0.047 |

| 9 |

Convenience store |

0.066 |

0.007 |

| 10 |

Landscape pavilion |

0.229 |

0.025 |

| 11 |

Waterside boardwalk |

0.034 |

0.004 |

| 12 |

Square |

0.097 |

0.010 |

| 13 |

Elderly Services |

0.074 |

Haircut |

0.115 |

0.009 |

| 14 |

Healthcare services |

0.364 |

0.027 |

| 15 |

Grocery shopping |

0.154 |

0.011 |

| 16 |

Transportation services |

0.036 |

0.003 |

| 17 |

Mail services |

0.089 |

0.007 |

| 18 |

Education services |

0.132 |

0.010 |

| 19 |

Meal delivery services |

0.110 |

0.008 |

| 20 |

Accessibility |

0.050 |

Accessibility facilities |

0.750 |

0.038 |

| 21 |

Roads |

0.250 |

0.013 |

| 22 |

Safety |

0.232 |

Street lamps |

0.857 |

0.199 |

| 23 |

Guardrail |

0.143 |

0.033 |

| 24 |

Landscape |

0.024 |

Landscape of mountains and water |

0.206 |

0.005 |

| 25 |

Rural landscape |

0.078 |

0.002 |

| 26 |

Architectural landscape |

0.716 |

0.017 |