1. Introduction

1.1. Accident Situation

In tree care arborists use chainsaws. The work with chainsaws bears a risk of injuries. In 1994 in the United States the use of chainsaws caused the most injuries at the arm and hand area and the leg area [

1]. In Italy from 2007 until 2012 mainly head, trunk and leg were injured by accidents with the chainsaw [

2]. 1757 accidents with arborists were reported to the German insurance SVLFG in 2018. Sawing was the most common reason for injuries (785 cases). After injuries by branches and a hand-held saw, the chainsaw (185 cases) is on the 3rd place of the things and tools which caused the accident. The main activity which causes an accident is getting hit by something on second place is that the arborists cut themselves (251 cases including chainsaws and handsaws). The most dangerous work situation is sawing. Either the arborist gets hit by branches or the arborists cuts itself with a saw during the sawing activity. The most affected body part by chainsaws is the hand (414 of 1041 cases). Arborists often do not see their arms or hands because they are hidden by branches. [

3]

1.2. Gloves Used by Arborists

Function Principle of the protective gloves: Current cut protective gloves have several layers of cut protective fabric sewn into the back of the hand. The cut protection is often a warp-knitted fabric made of chemical fibers which are pulled out of the glove when it comes into contact with the saw and blocks the saw. These gloves must meet the standard EN ISO 11393-4:2019 [

4] when the chain is spinning out. In the standard are four different protective classes (class 0 at 16 m/s, class 1 at 20 m/s, class 2 at 24 m/s and class 3 at 28 m/s) dependent on the speed of the chain when the saw comes in contact with the textile. All classes refer to a chain speed when no gas is given.

Current protective gloves: The gloves available on the market meet the standard up to cut pro-tection class 2. Forest workers often work without class 2 gloves due to the limited comfort. Most glove models meet cut protection class 1.

Gloves worn by the arborists without protection: Since arborists not only have to work with the saw, but also have to climb in the trees, they often prefer thin gloves that allow a secure grip when climbing in the trees. Thick, multi-layered gloves are particularly disadvantageous for arborists. During the work the fingers should be protected by a glove. But thick gloves can hinder the secure handling of the chain saw [

5]. That's why arborists often only use thin knitted gloves that have a non-slip coating on the palm. These knitted gloves do not provide any protection against the chainsaw.

Lack of comfort and limitation of the protection: All personal protective equipment (PPE) for chainsaws currently includes several layers of cut protection textile. This protective textile is in gloves only on the top of the fingers and hands. In order to be able to achieve cut protection class 3 with the current textile cut protection, more than 7-10 layers of textile are used in cut protection trousers. For a glove, a 10-layer construction would mean the loss of tactility and freedom of movement. Since the cut protective gloves available on the market only protect up to a maximum of protection class 2, exists a market gap for cut protection class 3. At full throttle, a chainsaw can reach speeds of up to 35 m/s. Currently no glove on the market stops the chainsaw at full speed.

1.3. Current Trends in PPE and Chainsaws for Smart Personal Protective Systems (SPPS) in Forestry

Development of electrical chainsaws: Future electrically powered chainsaws will no longer have a run-off. Electric chainsaws have only two operating states, either a stationary chain or a chain speed faster than 28 m/s. Especially for arborists, there is a great risk that the saw will come into contact with their fingers. Branches are often lifted with one hand and the saw is operated with the other hand. The further development of top handle saws (motorized tree care saws) also means that arborists who have the appropriate training are increasingly operating the chainsaws with just one hand. Due to the high-risk potential of this type of saw, the manufacturers point out that top handle saws must not be operated with one hand and may only be used as intended for tree care. Therefore, the current textile-based PPE will no longer provide a sufficient protection.

Further development of smart PPE: Research has made progress in personal protective equipment by combining textiles and new technologies. These smart textiles can improve the protective effect of PPE [

6]. By extending PPE with smart functions a protection of the wearer at full chain speed could be achieved. Marchal et al. call this new type of PPE “smart personal protective systems (SPPS)” [

7]. With SPPS the protection and comfort level can be higher compared to state-of-the-art solutions [

8]. In a research project Beringer et al. developed a chain saw protective trousers with sensors [

9].

1.4. Aim of the Work

The aim of the work is to develop a glove which contains smart protective elements and which is accepted by the arborists at work. The purpose of this work is to elaborate a concept for future smart gloves for arborists.

2. Materials and Methods

For the development of the glove, accident statistics and accident situations were an-alyzed. For the correct selection of textiles and the pattern of the glove, various classic work situations of an arborist were discussed and categorized. In addition, tree care pro-fessionals were asked how they imagine a smart protective glove. The advice of the arbor-ists was also incorporated into the design of the glove. The glove belongs to PPE class 3, the legal and normative requirements for such a product also had to be considered. Since the glove is designed for the European market, regulations and standards that are valid in the EU for placing the PPE category class 3 on the market were reviewed and the relevant requirements that specifically concern the product were listed and transferred in to specifications and requirements. Based on the requirements developed above, several gloves were produced. The prototypes were discussed with the project team and with ar-borists. When evaluating the gloves, three aspects in particular were important: fulfillment of the legal aspects, wearing and working comfort for the user and durability and reliability of the integrated electronics. At the end a final prototype was tested together with a modified electrical chainsaw in a laboratory environment. During the test, particular attention was paid to ensuring that the saw stops in time if it comes too close to the glove.

3. Results

3.1. Regulations and Standards for Protective Clothing Against Chainsaws

To be allowed to sell a smart protective glove on the European market the product must comply with REGULATION (EU) 2016/425 [

10]. In order to develop a reliable product, the gloves must meet certain requirements and therefore also undergo testing procedures. PPE must provide protection against the hazards it is intended to protect against. The sensory protective glove for arborists is intended to protect against chainsaw cuts. In addition, the PPE regulation stipulates that other risks that may arise during the intended use must be considered. For this purpose, a risk analysis of the work situations on the tree was carried out. It emerged that mechanical risks exist in every work situation. Therefore, protection against mechanical risks and protection against chainsaw cuts were defined as basic requirements for the protective effect of the sensory protective glove. The general requirements for protective clothing are described in DIN EN ISO 13688:2022-04 [

11]. This standard is relevant for general ergonomic aspects, the safety of the material and what kind of information the user should receive about the PPE. In this work, the standard DIN EN ISO 11393-4 [

4] is therefore important for protective gloves intended for users of hand-held chainsaws and this standard describes the requirements for protective gloves against chainsaw cuts. The most basic standard for gloves is DIN EN ISO 21420 [

12], which deals with general requirements and testing procedures of protective gloves. Due to the variable areas of application of protective gloves, it is necessary to use standards that relate to the specific areas of application. This standard in turn refers to the standard DIN EN ISO 388:2019-03 [

13], which deals with protective gloves against mechanical risks.

Therefore, protection against mechanical risks and protection against chainsaw cuts were defined as basic requirements for the protective effect of the sensory protective glove. The standards and examples for the development of an arborist specific product are listed in

Table 1.

3.2. Additional Regulations and Standards Because of the Smart Function in the Glove

The developed glove can be classified as smart PPE with electronics according to the classification in [

8] and it interacts with a machine. Therefore, regulations and standards from the area of electronical products and machine construction are also relevant. The glove contains electronics which should be safe to use. The LVD (2014/35/EU) [

14] sets out essential safety requirements to protect users from electric shock and other hazards. For the interaction between the saw and the glove it is important, that the system is not disturbed by electromagnetic inferences. The requirements on electromagnetic compatibility are listed in EMC Directive (2014/30/EU) [

15]. In order to comply with the RoHS Directive (2011/65/EU) [

16], the electronic components must not contain any harmful substances or substances prohibited in the EU. Because of the interaction between the glove and the saw the glove can be seen as an additional part of a machine. Therefore the Machinery Directive (2006/42/EC) [

17] should be considered to guarantee the safety of the interacting system.

Table 2 shows the standards mentioned above with specific examples for the arborist´s glove.

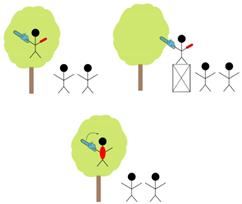

3.3. Different Work Situations and Their Risk of Getting Injured By the Chainsaw

Together with the project team and an instructor for arborists the typical work situations of arborists were identified. The work situations can be divided into three categories (

Table 3): working with the ropes, doing tree care in the tree and to tidy up.

3.4. Requirements on the Design and Pattern of the Glove Dependent on the Work Situation

For the development of the glove the work of arborists was analysed and discussed with arborists and tree care instructors. During the work analysis, attention was paid to which objects and surfaces the glove comes into contact with and which hand movements the arborist performs.

Requirements when working with the rope: Since the arborist´s hands grip, hold, pull and tie the ropes, there is a lot of friction on the insides of the hands and fingers. The ropes also have a rough surface. It was therefore concluded that the protective gloves on the insides of the hands and fingers should have sufficient protection against mechanical injuries such as high abrasion resistance and tear resistance. In addition, the fingers need to have a high level of tactility, mobility and grip so that the climbing tools can be operated and the ropes can be gripped and tied tightly. Therefore, the protective gloves should allow for a high level of finger mobility and have a high level of grip and tactile sensitivity at the fingertips. In addition, fingers can get caught between the ropes or in the climbing tools such as carabiners or ropes when tying knots, which can lead to crush injuries. When the arborists were questioned, it emerged that it is important that the glove has no tabs, buckles or raised areas and that it fits very tightly so that nothing gets pulled into the safety device when working with the rope or the rope is blocked as a result.

Requirements when the arborist climbs: The rough and sharp-edged surfaces of the tree can lead to cuts and abrasions. It was therefore deduced that the protective gloves should offer protection against mechanical injuries such as high abrasion resistance, cut resistance and tear resistance. The German Social Accident Insurance (DGUV) also describes the risk that the hands can come into contact with plant parts, splinters, spines and thorns, which can penetrate the skin and cause inflammation or allergies [

18]. Furthermore, dirt and small branches can disturb the arborists at work if they get into the gloves. Dirt with a certain amount of residual moisture on the gloves can also impair the sensitivity and grip of the hand as well as the functionality of the sensors and electronics. It was therefore deduced that the protective gloves and the electronics should be resistant to small branches and dirt getting in.

Requirements when the arborist saws: There is a high risk of cuts when sawing with a chainsaw, as the arborist can saw into his free hand when operating the chainsaw with one hand. Branches and leaves can increase the risk of cuts if they restrict the view of the hands. The arborist could also injure himself with the chainsaw by slipping from the working position. There is also a risk of injury from escaping substances such as petrol or oil if the hand slips, as these can make the handle of the saw slippery. There is a risk of cuts for both hands. Splinters of wood can be thrown into the air when sawing, which can cause injuries if they hit the body. Finally, the DGUV sees frequent hazards in one-handed operation of the chainsaw, sawing in unsafe positions, kickback of the chainsaw, flying chips and splinters and fuel [

19]. From this, requirements for protective gloves were derived, such as very high protection against chainsaw cuts on both hands, a very high grip on the palms of the hands and impermeability to wood splinters. The electronic cut protection must provide complete cut protection on all fingers of both hands and arms. In addition, the protective gloves should be water and oil repellent and clearly visible. The integrated electronics and sensors should also be protected from water and oil.

Requirements when the arborist tidies up: Rough and sharp-edged surfaces of the tree can lead to cuts and abrasions. Therefore, the protective gloves should offer protection against mechanical injuries such as high abrasion resistance, cut resistance and tear resistance. It is important that the glove has a tight hem to avoid dirt or small branches inside of the glove.

The requirements dependent on the work situation are listed in the table below.

Table 4.

construction requirements for the glove dependent on the work situation.

Table 4.

construction requirements for the glove dependent on the work situation.

| |

To attach the ropes/

to rope down |

To climb |

To saw |

To tidy up |

| Tactility |

High |

High |

Low |

Middle |

| Covered fingers |

All fingers must be covered by a glove |

All fingers must be covered by a glove |

All fingers must be covered by a glove |

All fingers must be covered by a glove |

| Fit |

Tight |

Tight |

Tight hem to avoid dirt inside of the glove |

Loose or tight fit |

| Fabric |

Thin, good grip, robust, resistant to abrasion, moisture and dirt repellent |

Thin, good grip, robust, resistant to abrasion, moisture and dirt repellent |

Good grip, signal color (left), robust |

Robust, moisture and dirt repellent, resistant to abrasion |

| Sensors |

Active |

Active |

Active |

Not active |

| Influences |

Moisture, mud, abrasive surfaces |

Moisture, mud, abrasive surfaces, sharp edges |

Oil, dust, petrol |

Moisture, mud, abrasive surface, sharp edges |

3.5. Different Patterns and Designs for the Glove

According to the requirements listed in 3.1., 3.2., 3.3. and 3.4. several glove patterns were created. At the beginning, four gloves were made without sensors in order to find the right fit for the intended use.

Climbing glove: This glove model which is shown in

Figure 1 (a). It was inspired by a traditional climbing glove because arborists climb a lot during their work. To achieve a good tactility for the ropes and the tree care the glove has open fingers. For a better movement and fit the glove is made with elastic fabric (white fabric in (a)). The cuff of the glove reaches the elbow to achieve a cut protection by sensors for the underarm. For the climbing with the ropes the palm is reinforced with a non-elastic durable fabric (dark grey fabric in (a)). This glove model consists of several different fabrics and pattern parts. Therfore this glove is more time consuming to sew.

Underarm cuff: This model shown in

Figure 1 (b) consists of one pattern part and can be sewn very quickly. The knitted elastic fabric allows the arborist a high freedom of movement. The fingers are open and the thumb hole avoids that the cuff slides up. The idea of this model was, that the sensors can be integrated at the underarm and the arborists can choose and change their preferred gloves for the protection against dirt and scratches.

5-fingers glove with non-elastic fabric: The 5-fingers glove shown in

Figure 1 (c) consists of two identic pattern parts. This glove can be sewn with an automated sewing machine or embroidery machine. The back of the hand is made with an elastic fabric to have enough freedom of movement, when the hand is bend. The non-elastic fabric is at the palm of the hand. The non-elastic fabric can be used to embroider sensors on the fabric.

5-fingers glove with elastic fabric only: The 5-fingers glove shown in

Figure 1 (d) has two identic pattern parts and can be sewn automatically. Both sides of the glove are made out of elastic fabric. Therefore, this glove has more freedom of movement and fits to more persons. The disadvantage is that sensors and conductive paths can´t be applied on the fabric as easily as on non-elastic fabrics.

3.6. Asking Arborists about the Four Glove Models and Their Wearing Behavior of Gloves

The gloves listed in 3.5. have been discussed with arborists and industry partners. Four glove designs without sensors were sewn to ask arborists about their preferred glove design. The results for each glove model were:

Climbing glove: The climbing glove was not preferred by any arborist because of the open fingers. During the work dirt, dust, small branches and needles can accumulate in the glove.

Underarm cuff: The arborists think that this glove is suitable to wear. One big advantage for them was that they still can wear their personally preferred working gloves above the smart protective underarm cuff.

5-fingers glove with non-elastic fabric: The non-elastic fabric causes to many pleats when the hand grabs something. The arborists were concerned that fabric could be pulled into the rope safety device while working with the rope.

5-fingers glove with elastic fabric only: All arborists liked this model because of the high flexibility and tactility. Arborists expressed concerns when the glove is equipped with smart functions. The glove will only last a few days because of the highly abrasive work and it would be expensive to throw away the dirty and broken glove with the electronics.

Wearing behaviour: It turned out that arborists prefer very individually different gloves. Gloves with protection against chainsaw are not worn. The reason is that arborists and forest workers prefer a variety of different gloves and change them several times a day depending on the operation. As a result of the discussion it was decided to continue the development with the arm cuff and a flexible 5 finger glove. The cuff has the advantage that arborists still can wear their own gloves and change them individually dependent on the current work situation. Another advantage is that the electronics of the cuff can be protected by the glove worn above. The cheap working gloves can be thrown away, when they are broken and the smart cuff remains. An extended underarm cuff could enlarge the cut protected area and could be used for the integration of electronics.

3.7. Asking Arborists about the Preferred Position of the Electronics

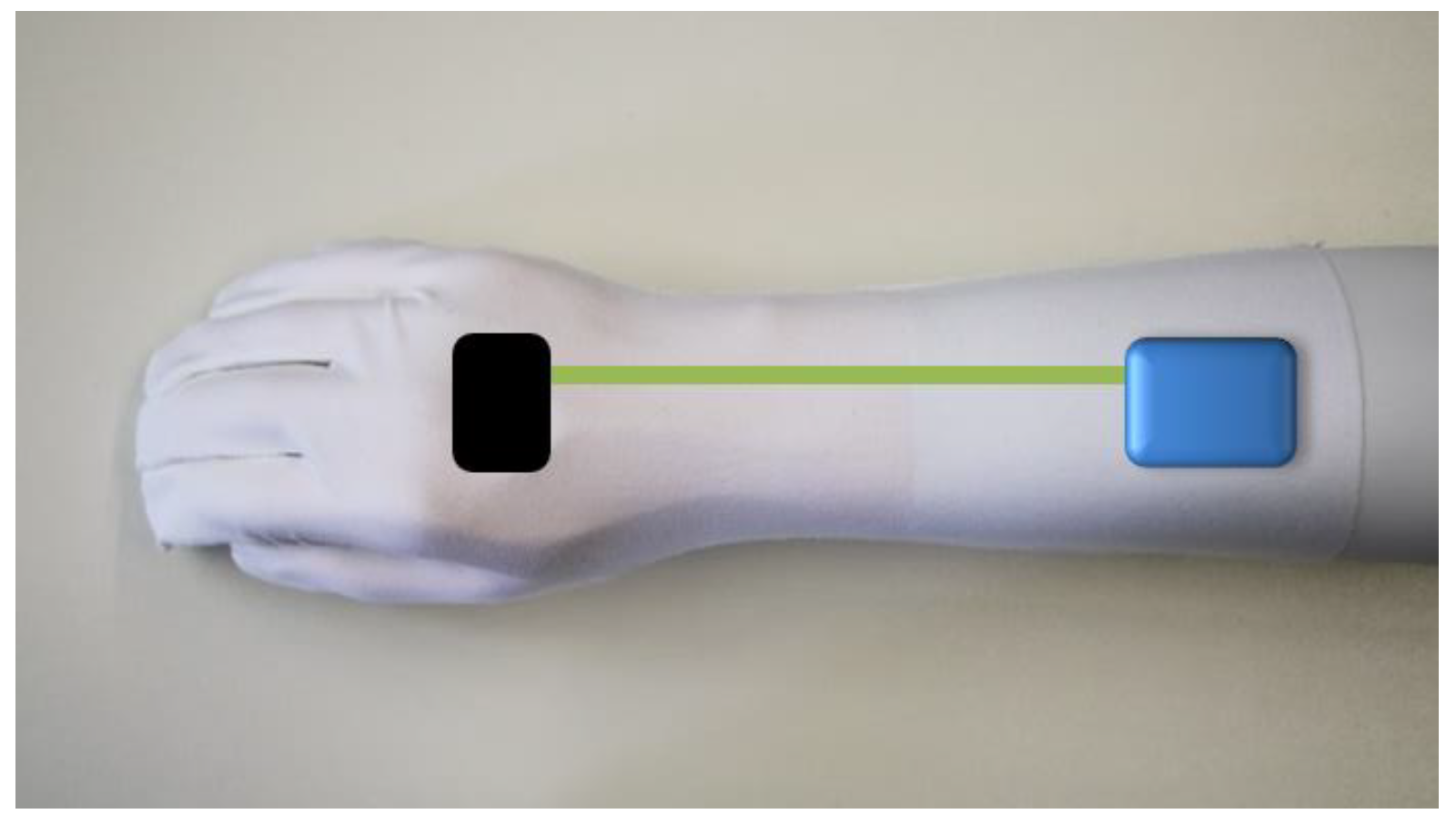

In addition to the design of the gloves, the arborists were also asked where the electronics on the gloves should best be placed. Since the battery and Bluetooth modules are housed in a solid housing, this component is not deformable and protrudes beyond the glove. Since this protrusion represents a potential risk when working with the rope, it was decided to attach the solid housing to the forearm as shown in

Figure 2. The connection between the sensors on the wrist and the electronics housing is made via conductor tracks.

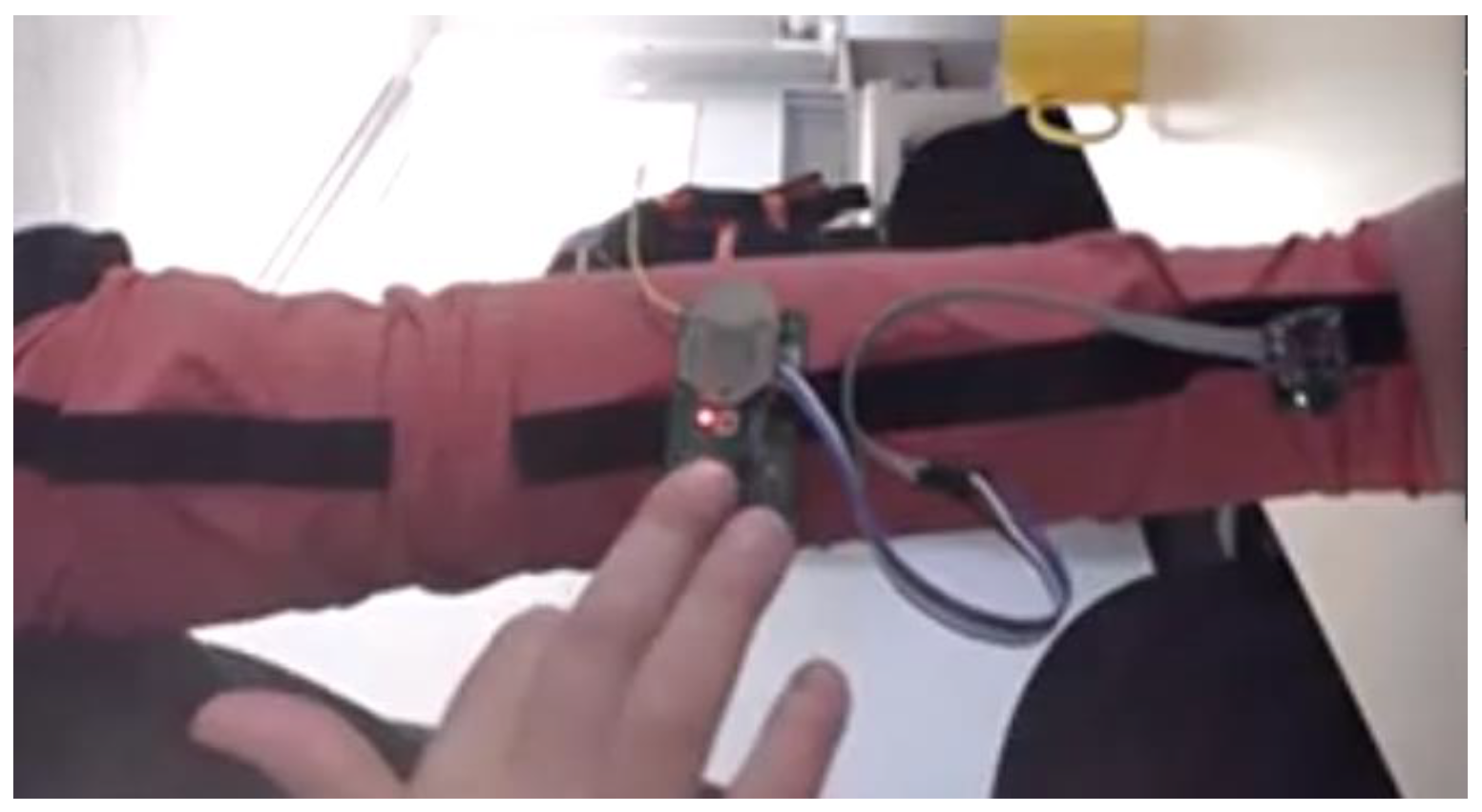

3.8. Integrating Sensors and Electronics into the Arm Cuff

As a result of the discussion with arborists an elastic arm cuff was equipped with electronics, shown in figure 3. To achieve an interaction between the arm cuff and the electrical chainsaw the cuff contains the following electronic parts: battery, conductive paths and sensors. The placement of the electrical parts in the cuff is shown in

Figure 3.

3.9. Testing the Arm Cuff under Laboratory Conditions

To validate the concept of the protective function the underarm cuff was tested together with a modified electrical chainsaw. The aim of the test was to observe the interaction between the arm cuff and the chainsaw. The arm cuff was worn by a test person at the left arm. After a calibration of the system the test person held the modified electrical chainsaw in the hand. To see whether the saw and the glove interact and are coupled with each other, an LED has been attached to the saw and the arm cuff, the LED is green, both products are connected to each other during the work situations and the interaction behavior was analyzed. The result of the test was that the system interacted well. The chainsaw stopped timely when the arm cuff came too close.

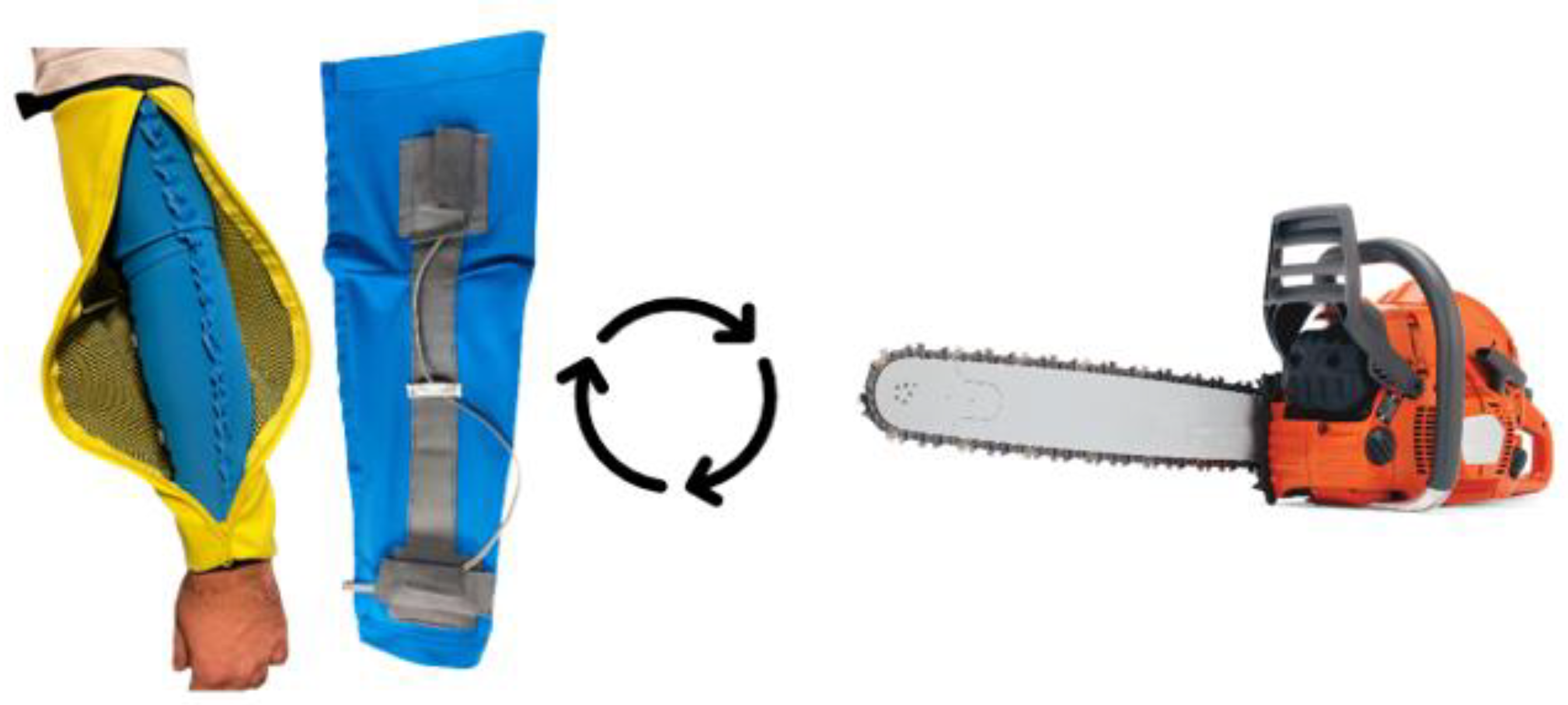

3.10. Final Arm Cuff

After the tests a final arm cuff was made. This arm cuff has an additional protective layer (yellow fabric in

Figure 4). The yellow fabric is a protection for the conductive paths and the sensors. The cuff can be opened by a zipper. The zipper allows the operator to change the battery and to control the electronics optically.

4. Discussion

4.1. Design and Electronics

The authors agree to Buchweiller et al. that electronics and circuits which are part of PPE should have at least the same protection reliability as traditional PPE. There should not exist new risks and there must be confidence into new SPPS [

20]. For example it is important for the end user to have an indicator light that shows that the system is working. This allows the arborists to rely on the system because they can see that the saw and the glove are connected.

4.2. Test Area and Amount of Tests

The functional tests were carried out on a small scale. The final arm cuff was tested together with the configured electrical saw. The tests took place in a laboratory environment. For further developments and research, it is desirable to have the functional tests take place in a working environment. In the working environment human influences (sweat) and environmental influences (dirt and abrasion) can be analyzed. To get more information about the reliability of the system the safety function of the glove and the saw should be tested over a longer period of time and in different work situations. Above all, the reliability of the electronics must be checked. The saw's shutdown function should work in every work situation so that the arborist does not feel hindered in his work by the smart functions.

4.3. Missing Standards and Test Methods

A reliable test environment should be created not only in a real work situation, but also under laboratory conditions especially for notified bodies. The new protective functions must be developed with a high reliability and tested properly. New test methods and standards for smart PPE must be elaborated. Not only the individual components of the system, but also the reliability of the entire system must be tested. As well the acceptance of the user is important for the success of such new technologies at work. Therefore, they must be well informed [

8]. The authors agree to the current or foreseeable problems of smart PPE listed by Dolez et al. in [

21]. To move forward in the area of smart PPE more specific standards and guidelines are needed. Companies which start to produce smart PPE need guidelines to design and develop it. Notified bodies need standards and test methods to proof the conformity of smart PPE.

5. Conclusions

The protection against chainsaws by textiles is often limited by the thickness and the lack of comfort. Smart textiles can overcome this limitation by creating lightweight protective solutions. New concepts of textile based smart protection systems can offer better ways of protection. The arm cuff shows how accidents can be avoided in future by the connectivity and interaction between machines and operators. In the project, it turned out that arborists had difficulty accepting a smart glove with fingers because they want to wear and choose their own gloves. An intelligent arm cuff was the solution. The functional tests showed that an interaction between the arm cuff and the saw works. The saw was stopped as soon as the worker's arm came too close to the saw.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization ideas S.B., D.W., D.F. and M.S., data curation management M.S., funding acquisition S.B., investigation conducting a research S.B., D.W., D.F. and M.S., project administration management S.B., resources provision of study materials, laboratory samples, computing resources, or other analysis tools. S.B., D.W., D.F. and M.S., software programming M.S., validation verification S.B., D.W., D.F. and M.S., visualization preparation S.B. and D.F., writing - original draft preparation S.B., Writing - review & editing preparation S.B..

Funding

This Project ZF4060070CJ9 was supported by the Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Climate Action (BMWK) on the basis of a decision by the German Bundestag.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Occupational Safety and Health Administration, ‘eTool : Logging - Manual Operations - Logger - Chain Saw - Chain Saw Injury Locations | Occupational Safety and Health Administration’, Chain Saw Injury Locations. Accessed: May 08, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.osha.gov/etools/logging/manual-operations/logger/chain-saw/saw-injuries.

- S. R. S. Cividino, R. Gubiani, G. Pergher, D. Dell’Antonia, and E. Maroncelli, ‘Accident investigation related to the use of chainsaw’, J. Agric. Eng., vol. 44, no. s2, Art. no. s2, Sep. 2013. [CrossRef]

- Sozialversicherung für Landwirtschaft, Forsten und Gartenbau, ‘Unfallstatistiken in der Baumpflege und Waldarbeit 2018’.

- ‘EN ISO 11393-4:2019 - Protective clothing for users of hand-held chainsaws - Part 4: Performance requirements and test methods for protective gloves (ISO 11393-4:2018)’, iTeh Standards. Accessed: May 08, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://standards.iteh.ai/catalog/standards/cen/2ed00dc9-f22a-42ff-a496-8c67b8628d28/en-iso-11393-4-2019.

- M. Huber, S. Hoffmann, F. Brieger, F. Hartsch, D. Jaeger, and U. H. Sauter, ‘Vibration and Noise Exposure during Pre-Commercial Thinning Operations: What Are the Ergonomic Benefits of the Latest Generation Professional-Grade Battery-Powered Chainsaws?’, Forests, vol. 12, no. 8, Art. no. 8, Aug. 2021. [CrossRef]

- P. I. Dolez, S. Marsha, and R. H. McQueen, ‘Fibers and Textiles for Personal Protective Equipment: Review of Recent Progress and Perspectives on Future Developments’, Textiles, vol. 2, no. 2, Art. no. 2, Jun. 2022. [CrossRef]

- P. Marchal and J. Baudoin, ‘Proposal for a method for analysing smart personal protective systems’, Int. J. Occup. Saf. Ergon. JOSE, pp. 1–11, 2021. [CrossRef]

- M. Thierbach, ‘EU_OSHA_discussion_paper_Smart_PPE’, Aug. 2020, [Online]. Available: https://cen.iso.org/livelink/livelink/open/centc248wg31.

- J. Beringer, A. Mahr-Erhardt, and P. Hoffmann, ‘C3.3 - Senor-based Personal Protective Equipment in forestry work with dangerous machines and equipment (power saws) – IGF No. 16119 N’, Proc. Sens. 2013, pp. 389–390, May 2013. [CrossRef]

- ‘REGULATION (EU) 2016/ 425 OF THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT AND OF THE COUNCIL - of 9 March 2016 - on personal protective equipment and repealing Council Directive 89/ 686/ EEC’.

-

DIN EN ISO 13688:2022-04, Protective clothing - General requirements (ISO 13688:2013 + Amd 1:2021); German version EN ISO 13688:2013 + A1:2021, Apr. 2022. [CrossRef]

- E. Standards, DIN EN ISO 21420 Protective gloves - General requirements and test methods (ISO 21420:2020). Accessed: Oct. 24, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.en-standard.eu/din-en-iso-21420-protective-gloves-general-requirements-and-test-methods-iso-21420-2020/.

-

DIN EN 388:2019-03, Protective gloves against mechanical risks, German version, Mar. 2019. [CrossRef]

-

Directive 2014/35/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 26 February 2014 on the harmonisation of the laws of the Member States relating to the making available on the market of electrical equipment designed for use within certain voltage limits (recast) Text with EEA relevance, vol. 096. 2014. Accessed: Oct. 25, 2024. [Online]. Available: http://data.europa.eu/eli/dir/2014/35/oj/eng.

-

Directive 2014/30/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 26 February 2014 on the harmonisation of the laws of the Member States relating to electromagnetic compatibility (recast) Text with EEA relevance, vol. 096. 2014. Accessed: Oct. 25, 2024. [Online]. Available: http://data.europa.eu/eli/dir/2014/30/oj/eng.

-

Directive 2011/65/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 8 June 2011 on the restriction of the use of certain hazardous substances in electrical and electronic equipment (recast) Text with EEA relevance, vol. 174. 2011. Accessed: Oct. 25, 2024. [Online]. Available: http://data.europa.eu/eli/dir/2011/65/oj/eng.

- ‘Directive - 2006/42 - EN - Machinery Directive - EUR-Lex’. Accessed: Oct. 25, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/dir/2006/42/oj.

- ‘DGUV Regel 114-018 Waldarbeiten’. Deutsche Gesetzliche Unfallversicherung (DGUV), 2011. [Online]. Available: https://publikationen.dguv.de/widgets/pdf/download/article/1019.

- ‘DGUV Information 214-046 Sichere Waldarbeiten’. Deutsche Gesetzliche Unfallversicherung e.V. (DGUV), May 2014. [Online]. Available: https://publikationen.dguv.de/widgets/pdf/download/article/1263.

- J.-P. Buchweiller et al., ‘Safety of electronic circuits integrated into personal protective equipment (PPE)’, Saf. Sci., vol. 41, no. 5, pp. 395–408, 2003. [CrossRef]

- P. I. Dolez, J. Decaens, T. Buns, D. Lachapelle, and O. Vermeersch, ‘Applications of smart textiles in occupational health and safety’, IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng., vol. 827, no. 1, p. 012014, Apr. 2020. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).