3.1. AI in Wind Energy

In pertinent literature, several reviews discuss the use of AI in wind energy [

26,

27,

28,

29,

30]. In [

26,

27], a brief overview of existing statistical, physical, correlation and neural network approaches for power and wind speed estimation is presented. An overview of data mining methods used for the estimation of wind power is provided in [

28]. In this work, the extremely short, intermediate, medium, and long-term wind power estimations are covered in four categories. Similarly, [

30] examined data mining techniques for forecasting short-term wind speed and power. Three categories of probabilistic models: short, medium, and long term, for forecasting wind power are listed in [

29].

Relevant research indicates three main categories of AI used in wind energy: neural, statistical, and evolutionary learning. These categories are integrated to create hybrid AI methods [

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37,

38,

39,

40,

41,

42,

43,

44,

45,

46,

47,

48,

49,

50,

51,

52,

53,

54,

55,

56,

57,

58,

59]. Many studies focus on wind power and speed prediction using AI neural learning techniques [

31,

32,

33]. Mabel et al. estimate wind output over three years from seven wind farms using a neural network with feed-forward backpropagation (BPNN) [

31]. The training and test data sets’ Root Mean Square Errors (RMSEs), for the BPNN, are 0.0070 and 0.0065, respectively, indicating excellent prediction accuracy. Three different ANN approaches, Radial Basis Function Neural Network (RBFNN), BPNN, and Adaptive Linear Element Network (ADALINE) have been used to estimate wind speed from the two locations. There has also been a comparison of the three models’ performances [

32]. While the effectiveness of ANN approaches varies depending on the location of wind farms, the RBF approach yields the best results (minimum RMSE of 1.444) for a single site. The BPNN yields RMSE of 1.254 at minimum for a single site. Through trial and error, Mabel et al. [

33] improved the BPNN setup for wind power estimation. With relative humidity, generation hours and wind speed as inputs, a 3-5-1 ANN yields the optimal estimating results (Mean Square Error (MSE) of

).

Since ANN techniques’ performances are inconsistent, certain changes have been recommended to increase their efficiency [

34]. In certain studies, additional methods have also been incorporated for comparison [

35,

36,

37,

38,

39]. Recurrent high-order neural networks, an advanced kind of ANN, were used for wind power estimation by Karnataka’s et al. [

34]. The ANN model’s performance is juxtaposed with the Naïve Bayes (NB) approach. The lowest RMSE of 4.2 is achieved by the ANN in comparison to the NB. For the years 1993–1997, the Marmara’s wind speed was spatially forecasted using the BPNN approach [

35]. A comparison is made between the efficiency of the ANN model and the Trigonometric Point Cumulative Semi Variogram (TPCSV) method. For the majority of months and sites, ANN yields an increased coefficient of correlation between predicted and actual wind speed. For instance, in January, for the Canakkale site, the correlation coefficients for ANN and TPCSV were 0.95 and 0.88, respectively. According to Alexiadis et al.’s research [

36], the BPNN approach significantly increases wind speed and wind power estimation accuracy by

when compared to the persistent forecasting model. To anticipate wind speed from the two wind farms, the Bayesian Combination (BC) methodology, ADALINE, BPNN, and RBFNN techniques were used by Li et al. [

37]. When compared to ANN approaches, the BC method yields a more reliable and superior result estimation (RSME of 1.5). The analysis of twelve estimating strategies, with the non-linear ANN methods of Neural Logic Networks (NLN) and the Auto Regressive Moving Averages (ARMA) approaches, has been reported [

38]. The approaches applied wind speed data having hourly resolution. Compared to other approaches, NLN demonstrates the best results (RMSE improvement of 4.9%). During two years, from 2004 to 2005, Cadenas et al. [

39] employed BPNN to forecast wind speed with information gathered from Mexico’s Chetumal wind farm in Quintana Roo. The ANN and Single Exponential Smoothing (SES) methods’ performances are compared. Compared to the SES approach (MAE of 0.5617), the earlier approach works better (MAE of 0.5251).

Fuzzy logic [

40] and its integration with ANN approaches were also investigated in various papers [

40,

41,

42] for wind power forecasting. Simoes et al. [

40] designed a wind generation system of 3.5 kW using fuzzy logic. The designed system can be implemented in the field and performs well. The combination of fuzzy logic with ANN, and RBFNN approaches was applied by Sideratos et al. [

41] for wind power estimation. Findings are useful for the operational planning of wind farms, one to forty-eight hours in advance. Monfared et al. [

42] have estimated the wind speed using the fuzzy and BPNN techniques. The suggested methods perform better than the conventional ones (RMSE of 3.27 and 3.30 for two strategies, respectively, in one situation).

Several statistical techniques were covered in [

43,

44]. A probabilistic approach for estimating short-term wind output was presented by Juban et al. [

43]. The process yields a predictive probability density function for estimation based on the kernel density function. The model’s reliability is within the range of 2 to

, consistent with findings from related studies. Mohandes et al. [

44] employed the Support Vector Machines (SVM) approach to estimate wind speed utilizing at Madina, Saudi Arabia, wind data. Additionally, a comparison is made between the Multilayer Perceptron (MLP) neural networks and SVM performance. Compared to the ANN approach (MSE of 0.0078), SVM achieves worse estimation accuracy (MSE of 0.009).

Several studies [

45,

46,

47,

48] have employed the Adaptive-Neuro-Fuzzy-Inference-System (ANFIS), a combination of fuzzy and neural approaches, to enhance the performance of the ANN method. Potter et al. [

45] use the wind data from the Australian state of Tasmania along with ANFIS to predict wind power on an extremely short basis. When wind data is examined from a session in a different year, the MAE is consistently less than eight. Based on the speed of wind data at altitudes of 10, 20, 30, and 40 meters, Mohandes et al. [

46] computed wind speed up to a height of 100 meters using ANFIS. Compared to the actual speed of wind at the same height, the ANFIS projected wind speed at 40 m has a 3% Mean-Absolute Percentage Error (MAPE). Yang et al. [

47] interpolate the information about the lost wind calculated from China’s twelve wind farms using the ANFIS approach. The actual observed wind speed and the ANFIS forecasted wind speed had an RMSE of 0.22. Maximum-power-point-tracking (MPPT) has been designed by Meharrar et al. [

48] using an ANFIS wind generator. As an input, wind speed is used by the ANFIS to estimate the rotational speed of wind turbines. In training, the ANFIS performs effectively with an error of 0.005.

In addition to ANFIS, ANN is also combined with other techniques to improve prediction performance [

30,

49,

51,

52]. For example, Yang et al. [

49] used BPNN along with Wavelet Analysis (WT) to diagnose faults in the wind turbine gearbox, successfully identifying two typical situations, three fault situations, one severe fault situation, and two light fault situations. To choose the input parameters and variables of the ANN and the closest neighbor techniques used to estimate wind power in the short-term and network traffic analysis, Jursa et al. [

50] implemented two evolutionary algorithms: Differential Evolution (DE) and Particle Swarm Optimisation (PSO). Prediction accuracy is 2.8% higher with the PSO-optimized ANN than with the manually structured ANN. An enhanced version of the FNN and the Empirical Mode Decomposition (EMD) technique for wind speed estimate has been created by Guo et al. [

51]. The performance of the improved EMD&FNN is better (MSE of 0.1647) than that of the FNN (MSE of 0.1512) and EMD-FMM (MSE of 0.1295). Pourmousavi et al. [

52] have presented an ANN-Markov chain (MC) technique for short-term wind speed forecasting. For larger margins, the ANN-MC has a lower error (94.83) than the ANN (96.04).

Hybrid AI techniques are described in detail [

53,

54,

55,

56,

57,

58,

59]. Fuzzy techniques based on the two GA models (real-coded GA and binary-coded GA) were developed by Damousis et al. [

53] for wind power and speed prediction. When the statistics about wind energy from a remote site were analyzed by applying wireless modems, the fuzzy approach produced higher accuracy than the persistent technique for the next hour and longer, respectively, by 29.7% and 39.8%. The SVM and EEMD approaches are combined by Hu et al. [

54] to construct and evaluate a hybrid forecasting method. Using the suggested hybrid method, the monthly average wind speed measured at three different locations in China was determined. When EEMD is placed against two conventional time series approaches; Seasonal Autoregressive Integrated Moving Average (SARIMA) and Autoregressive Integrated Moving Average (ARIMA); EMD-SVM and SVM yield an MAE of 0.12. Cadenas et al. [

55] created a novel hybrid model that combined BPNN and ARIMA techniques to forecast wind speed at three distinct locations in Mexico. In comparison to the ARIMA (MSE of 4.1) and ANN (MSE of 5.65), the hybrid approach has an MSE of 0.49. For short-term wind speed prediction, a hybridized ANN approach with the fifth-generation Mesoscale Model (MM5) has been proposed by Salcedo-Sanz et al. [

56]. By using the MM5 output, the ANN technique yields higher accuracy in estimating, with MAE ranging from

for varying hidden layer neuron counts (9-5) and wind turbine sites. Liu et al.’s [

57] proposed a hybrid AI method with WT, GA, SVM, and deep quantitative analysis. The GA is applied for the modification of SVM parameters. The WT, SVM, GA model fared improved (MAE of 0.6168) than the persevering method (MAE of 0.8355) and SVM-GA (MAE of 0.7844). Kong et al. [

58] developed a novel hybrid model for forecasting wind speed using PSO and PCA for SVM parameter optimization, and a refined form of SVR called Reduced Support Vector Machine (RSVM). Effective estimating accuracy is demonstrated by the RSVM. In Rahmani et al.’s [

59] proposed hybrid intelligence technology, PSO and Ant Colony Optimisation (ACO), for the hourly wind power forecast for 43 data using temperature and wind speed as external variables. The hybrid approach produces the best MAPE of 3.50% when compared to PSO (MAPE of 10.50%) and ACO (MAPE of 5.8%). Pousinho et al. [

60] have developed a hybrid approach for risk optimization in trading wind energy that combines WT, PSO, and ANFIS. Portugal uses this hybrid approach to analyze data from wind farms. The predicted profit was accurately projected to be between 18719 and 18487 euros for various levels of risk values between 1 and 0. An outline of the studies discussed above is shown in

Table 1.

3.2. AI in Solar Energy

There has been much discussion in the literature about the significance of AI in solar energy applications [

61,

62]. The specific uses of ANN techniques in solar energy, including building heating load calculations and solar system design and modeling, are described in [

61]. Mellita et al. evaluated the use of AI in weather data modeling and on and off-grid PV system size [

62,

63] in addition to discussing its applications in PV system modeling, simulation, and control. In particular, [

61] provides a summary of the specific uses of ANN approaches in design and modeling, building heating load, etc. A brief overview of the research conducted by Mellita et al. on applying AI to meteorological data modeling, PV system sizing, control and simulation is provided in [

62]. The application of AI approaches to the dimensions of standalone and grid-connected photovoltaic systems has also been reviewed by Mellita et al. [

63]. A compilation of building energy consumption estimation techniques utilizing AI and statistics are found in [

63]. Dounis et al. [

61] gave an overview of the use of agent-based intelligent automation systems for building energy management. AI is being applied in both single and hybrid approaches to solar energy research [

64,

65,

66,

67,

68,

69,

70,

71,

72,

73,

74,

75,

76,

77,

78,

79,

80,

81,

82,

83,

84,

85,

86,

87,

88,

89,

90,

91,

92,

93,

94,

95,

96,

97,

98,

99,

100,

101,

102]. The most popular approach in solar energy research is ANN. It is utilized in PV connected to the grid to anticipate solar irradiance [

64,

65,

66,

67,

68,

69,

70,

71,

72,

73,

74,

75]. It is possible to attain a correlation in comparison with the actual and expected solar radiations of 98-99% and 94-96% on sunny days and gloomy days, respectively. Using temperature and humidity as inputs, the BPNN forecasts Global Solar Radiation (GSR) for the years 1998–2002 [

64]. The RMSE value between the actual and BPNN forecasted GSR was

. Kalogirou et al. [

65] employ BPNN to estimate the performance of heating systems based on solar water. The improved performance of BPNN is confirmed by the higher coefficient of determination values (

of 0.9808 and 0.9914 for the maximum temperature rise and extracted energy, respectively). Using the BPNN, beam solar irradiance was calculated by examining data from eleven distinct stations. The radiation model’s projected values and actual values had an RMSE of

to

[

66]. The daily ambient temperature is estimated with a BPNN of

, with an RMSE of 1.96 [

67]. The BPNN was used to estimate the daily sun irradiation with an RMSE of 5.5-7.5% [

68]. With an RMSE of 3.29%, a High Concentration Photovoltaic (HCPV) system with the maximum power was estimated using the BPNN [

69]. The BPNN was used to estimate the average monthly solar radiation around the globe, and the relation between the predicted and real solar irradiation was 0.97 [

70]. Using the BPNN, hot water quantity and solar energy production were calculated and the results showed

values of 0.9973 and 0.9978, respectively [

71].

Several studies in research [

72,

73,

74,

75] compare the effectiveness of the BPNN model to various methods. Tasadduq et al. [

72] utilize BPNN to estimate the ambient temperature 24 hours in advance, and they compare the effectiveness of BPNN with batch-learning ANN. Using BPNN for three years, the Mean Percentage Deviation (MPD) values attained were 3.16, 4.17, and 2.13. Alam et al. [

73] forecast diffuse solar radiation, both hourly and daily, with an RMSE of 4.5% using the BPNN, in contrast to 37.4% for alternative empirical techniques. Tymvios et al. [

74] predicted worldwide solar radiation using Ångström’s linear techniques and BPNN. Ångström’s linear technique and the BPNN method perform similarly (RMSE of 5.67–6.57%). The eight Chinese cities’ GSR estimates from 1995 to 2004 were estimated using the BPNN approach, and the results were compared to those obtained using empirical regression techniques. With a minimum RMSE of 0.867, the BPNN outperforms empirical regression techniques [

75]. For solar energy analysis, a few more techniques were employed in addition to ANN [

76,

77,

78]. The SVM approach, for example, is compared to the AR and RBFNN in terms of performance when used to predict short-term solar power [

76]. The SVM approach (MAE of 33.72

) outperforms the AR (MAE 62

) and RBF (MAE of 43

) approaches. Li et al. [

77] examined the performance of SVR and ANN for estimating solar PV energy production. The two approaches’ RMSEs were nearly identical. When estimating solar electricity generation, the RBF-SVM method performs better than the two forecasting techniques currently in use, PPF and Cloudy. Compared to the other two methods, SVM shows a 27% greater estimation accuracy [

78].

Applications for solar energy have also made use of several evolutionary AI techniques [

79,

80,

81]. Mashohor et al. [

79] proposed GA in solar tracking to enhance PV system performance. The optimal GA-solar system is produced by a GA with an initial population size of 100, 50 epochs, and probabilities of crossover and mutation of 0.7 and 0.001, respectively. The generating gain’s low standard deviation (1.55), which indicates higher system efficiency, further supports this claim. The best possible design for a solar water heating system takes advantage of GA. In particular, the GA is used to optimize the plate collector area to 63

, which yields a solar fraction value of 98% [

80]. Tracking PV arrays’ MPPT coupled to batteries was implemented by Kumar et al. [

81] using GA. The conventional Perturb and Observe (PO) algorithm’s performance is compared with the GA. The 400-line voltage is attained by the boost converter.

It has also been observed that combining AI techniques improves prediction efficiency [

82,

83,

84,

85,

86,

87,

88]. The ANN and TRNSYS are combined to forecast the performance of an Integrated Collector Storage (ICS) solar water heater, with an

value of 0.9392 [

82]. GA was used by Monteiro et al. [

83] to optimize the parameters of the Historical Similar Mining (HISIMI) model, which is used to estimate PV system power. The performance of the modal of GA-HISIMI (RMSE of 283.89) is compared with that of the classical persistence (RMSE of 445.48) and BPNN (RMSE of 286.11) approaches. In Algeria, the optimization of PV system size is achieved using the amalgamation of limitless impulsive response (IIR) filter and RBFNN [

84]. The RBF-IIR approach was used to estimate the optimal sizing coefficients, and its performance was compared with the MLP-IIR approach, BPNN, RBFNN, and classical models. Using the RBF-IIR approach, the sizing coefficients were computed with high accuracy (correlation of 98%). For the forecasting of solar radiation levels, WT and BPNN were combined [

85]. WT-BPNN outperformed the traditional approaches (ARMA, AR, MTM), recurrent, BPNN and RBFNN methods in terms of accuracy (97%) and performance. Without using exogenous inputs, GA-optimized BPNN is used to anticipate solar power output [

86]. GA-BPNN’s performance is compared with that of the k-nearest neighbor (KNN), ARIMA, BPNN, and persistent model techniques. The minimal RMSE of 72.86 kW is obtained using the GA-BPNN. To estimate PV system power, Mandal et al. [

87] combined WT and RBFNN and evaluated the results against, RBF, BPNN and WT-BPNN. The minimum RMSE for the WT-RBF is 0.23. The economic benefits of solar energy are optimized by the application of NN and GA in the group method of data handling (GMDH) [

88]. The ideal solution increases life cycle savings by 3.1-4.9%. Multiple studies [

89,

90,

91,

92,

93,

94] have employed the ANFIS method. These include modeling a PV power supply system with an accuracy rate of 98% [

89], satellite image data for the prediction of hourly global radiation [

90], average temperature and length of sunshine to predict solar radiation [

91], simulating a PS power supply [

92], and forecasting a solar chimney power plant’s performance [

93].

A variety of hybrid AI approaches have also been employed by solar energy systems [

94,

95,

96,

97,

98]. The following are a few of these: ARMA and Time Delay Neural Network (TDNN) are used to predict solar radiation [

96], For GSR prediction, a hybrid of the SVM and Firefly algorithm (FFA) is created, and its effectiveness is compared with that of the BPNN and Genetic Programming (GP) approaches (RMSE of 1.8661 for SVM-FFA), and PV connected to the grid power prediction is achieved through a hybrid of SVM and SARIMA methods [

97].

Table 2, provides an overview of the results of AI approaches, discussed above, for solar energy systems.

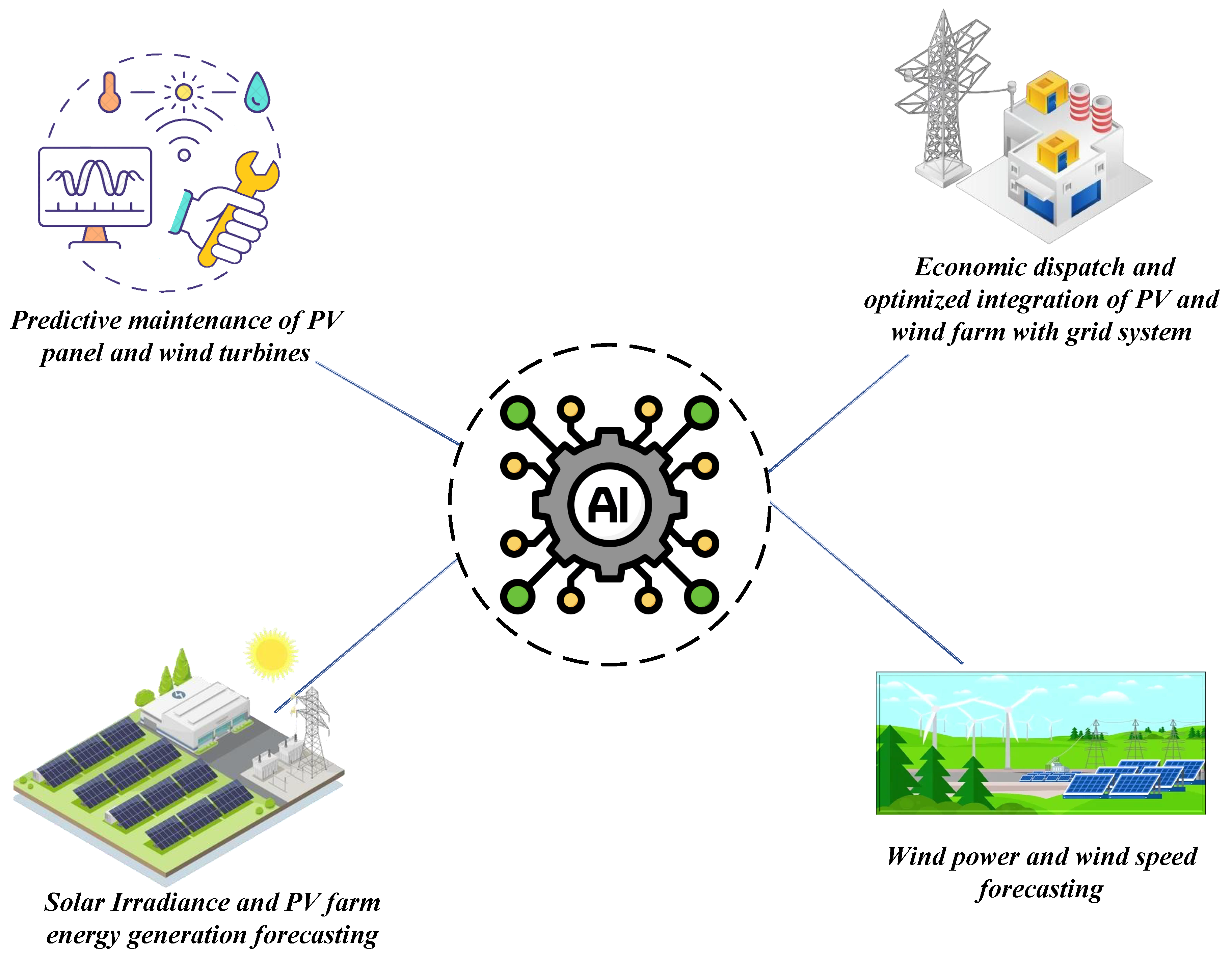

Figure 1 illustrates the application of AI for solar and wind energy resources.

3.3. AI in Geothermal Energy

Studies [

99,

100,

101,

102,

103] provide an overview of the use of AI approaches in geothermal applications. The authors in [

99] have given a brief overview of the potential applications of AI approaches with sensors and robots in geothermal well drilling design, control, optimization, computer modelling, and simulation of geothermal reservoir and its impact on the advancement of geothermal energy. Additional evaluations [

100] examine numerical models for geothermal reservoirs and enhanced geothermal systems by O’Sullivan et al. [

101,

102]. Study [

103] also provides a synopsis of the development of numerical modeling for geothermal reservoirs.

Table 3 outlines the use of AI in geothermal energy-related applications, both in standalone and hybrid forms [

104,

105,

106,

107,

108,

109,

110,

111,

112,

113,

114,

115,

116,

117,

118,

119,

120,

121,

122,

123]. To forecast the performance of Vertical Ground Coupled Heat pump (VGCHP) systems, Esen et al. [

104] employed BPNN with the Levenberg-Marguardt (LM), Pola-Ribiere Conjugate Gradient (PRCG), and Scaled Conjugate Gradient (SCG) algorithms. Better prediction efficiency is achieved with the eight neurons in the hidden layer of the LM-based BPNN (RMS of 0.0432). To predict the geothermal well’s Static Formation Temperature (SFT), LM-based BPNN was used by Bassam et al. [

105]. With five neurons in the buried layer of the BPNN, the prediction error is less than

. The best operating conditions for a geothermal well are determined using BPNN (with LM, CGP, and SCG) in [

106]. Using the temperature and vapor fraction of geothermal water with the ammonia fraction as inputs, the best-predicted values of generated and circulatory pump power are obtained by the seven-neuron BPNN hidden layer (RMSE of 1.5289). The ANN and BPNN (with CGP, LM, and SCG) are utilized for power cycle optimization, similar to ORC-Binary [

107]. For generating and needed pump circulation power, with 14–16 neurons in a hidden layer, the LM-based BPNN produced the greatest results (RMSE of 0.0001 for the

and

cycles). The cycle

input variable is comparable to the one outlined in [

106], but the cycle

analysis includes an extra input variable called outlet pressure. Using the real values for the 96.5% of data points, BPNN is utilized to generate a geothermal map at various depths with less than a 5% variance [

108]. In the Afyonkarahisar Geothermal District Heating System (AGDHS), thermal performance and energy destructions are predicted using the LM-based BPNN with good accuracy (RMSE of 0.0053) [

109]. Using eight distinct input parameters, the geothermal well’s Void Percent (VF) data were forecasted using BPNN, which has a foundation with the LM training approach. With an RMSE of 0.0966, six neurons in the hidden layer of BPNN produce the best forecast accuracy [

110]. The VF-ANN is used for predicting the stormwater treated by geothermal energy’s Biochemical Demand for Oxygen (BOD), nitrate-nitrogen, ortho-phosphate-phosphorus, ammonia and nitrogen. The QN-based BPNN yields the best accuracy for predicting ammonia and nitrogen [

111]. The AGDHS PID controller, which increases energy efficiency by 13%, is tested using BPNN [

112]. Greater accuracy in ORC-Binary geothermal plant modeling is achieved by using BPNN with LM for the

and

cycles (20 and 22 neurons in the hidden layer, respectively) and for the

type cycle [

113]. The site placements planning model [

114] makes use of geographic information data with the BPNN, which depends on the LM and SCG algorithms. With BPNN, conductivity maps of the ground can be created more accurately (83% of projected data have deviations of less than 10%) [

115]. With the use of the wellbore production database, BPNN, which is based on the LM algorithm, showed improved pressure drop prediction efficiency in geothermal wells [

116].

In certain investigations, the study of the geothermal system also used fuzzy logic and EA [

117,

118,

119,

120]. For VGSHP, Sayyaadi et al. [

117] used multi-objective optimizations with the EA and single-objective thermodynamic and Thermos Economic (TE) optimizations. Six EAs (two DE, GA, PSO Monte-Carlo random search) were used in another study [

118] to determine the ideal location of Borehole Heat Exchangers (BHEs). In Recirculation Aquaculture Systems (RAS), for geothermal heat [

119] and to control water temperature for maximum RAS output [

120], it has been possible to create a fuzzy logic controlled (FLC) system. Some analytical studies on geothermal energy [

121,

122,

123] used ANFIS and hybrid AI approaches. For example, VGSHP performance is assessed using ANFIS, and the results are compared with BPNN techniques (SCG, LM, and CGP algorithms). In this instance, ANFIS is more effective than BPNN techniques [

121]. ANFIS is also used to assess the AGDHS system (forecast of energy and energy rates) and compare it with BPNN techniques [

122]. In geothermal reservoir temperature prediction, GMDHNN based on GA and Singular Value Decomposition (SVD) is used and the results reveal that ANFIS outperforms BPNN approaches [

123].

3.4. AI In Hydro Energy

Different studies discussed the application of AI approaches in the hydro energy sector. Kishor et al. [

124] focused on the planning and management of hydropower facilities using both conventional techniques and contemporary AI methodologies such as GA, ANN, Fuzzy, ANFIS, etc. Nourani et al. discussed the importance and use of hybrid AI techniques based on wavelet pre-processors in hydro-climatology [

125], particularly in the assessment of the importance of hydrologic cycle operations. In hydro energy applications,

Table 4 summarises the utilization of both the single and hybrid AI approaches [

126,

127,

128,

129,

130,

131,

132,

133,

134,

135,

136,

137,

138,

139,

140].

In Taiwan, eight reservoirs are utilized to optimally schedule hydropower plant operations using the BPNN technique [

126]. Compared to Differential Dynamic Programming (DDP) and K-Nearest Neighbor (KNN), the BPNN is more economical. For linear and non-linear reservoirs, the discharge peak and peak time must be estimated. Smith et al. [

127] employed the BPNN technique in their modeling of the rainfall-runoff process. When predicting peak discharge for non-linear reservoirs and time to peak for linear reservoirs, BPNN achieves higher accuracy. For seventeen years, the San Juan River basin’s steam flow has been accurately predicted using the BPNN model in two distinct seasons [

128]. The most important components in the generation of hydroelectric power are the potential head and flow of water. Moreover, Kisi et al. [

129] investigated river flow modeling with the BPNN and gradient descent (GD) and compared the results with the autoregressive (AR) approach. Approximations using BPNN are more precise than those using AR. Estoperez et al. [

130] estimate the monthly power outage in advance (RMSE of 0.061) and used BPNN for micro-hydro power plant scheduling. In the research of hydro energy, the GA [

131,

132,

133] and fuzzy [

134] methodologies have also been employed. To plan a hydrothermal power system in Brazil, for instance, Carneiro et al. [

135] employed GA, and they compared the outcomes with those of a traditional non-linear programming (NP) optimization technique. For the years 1971–1973, the GA’s operating costs (726,742.2 MW) are lower than the NP’s (745,020 MW). For a comparable application, Gil et al. [

132] created a new GA (with the help of a group of skilled operators) and assessed how well it performed in comparison to other GA implementations. A new kind of GA known as Chaotic Hybrid (CH)-GA has been created by Yuan et al. [

133] to solve the issue of the short-term hydrogenation schedule being hampered by the water delay time. When compared to the conventional S-GA and NP, the CHGA yields a higher profit. Adhikary et al. [

134] examine the use of a fuzzy logic-based method to determine which of the four penstock materials, asbestos cement, steel, and GRP, is best for hydro turbines. The best material with the highest degree of index was determined to be GRP.

ANFIS and hybrid AI techniques’ role in the production of hydropower has also been covered in a few research [

135,

136,

137,

138,

139,

140]. In Taiwan, the Shihmen reservoir is controlled by the ANFIS approach, which predicts the release of water. The M-5 rule curves are also used to compare the method’s performance [

135]. The ANFIS performs better (there is less water scarcity) than the M-5 rule curves. Firat et al. [

136] estimated the Menderes River’s flow effectively using the ANFIS model. Multiple Regressions (MR) and ANN are used to compare ANFIS’s performance (the minimum relative error for ANFIS is 0.073). An ANN is integrated with an expert system through the use of Learning Vector Quantization (LVQ) and ART-MAP for hydropower plant predictive maintenance (PM) and Acoustic Prediction (AP) [

137]. The AP and PM come up with more accurate projections. GA and PSO-adjusted FLC have been developed by Sinha et al. [

138] regarding Automated Generation Control (AGC) in hydroelectric systems. In terms of settling time and peak overshoot, the GA-FLC and PSO-FLC outperform the conventional FLC. An AI hybrid approach for estimating river flow known as case-based reasoning (CBR) has been created making use of Elman ANN, modular ANN, Fourier Frequency Transform (FFT) and Hierarchical Clustering (HC) [

139]. The models’ performances are compared with CBR (minimum MAE of 17. 11 for CRB). The hydraulic energy production in Turkey is predicted by BPNN using the Artificial Bee colony (ABC) model (ABC is used to optimize BPNN) with a relative error of 0.23 [

140].

Figure 2 depicts AI applications for geothermal and hydro energy resources.

3.5. AI in Ocean Energy

The studies [

141,

142,

143,

144] provide a summary of how various AI approaches are being used for ocean energy. Essentially, [

141] discusses AI’s involvement in generating energy from oceans, while Aartrijk et al. [

142] provide an overview of AI’s role in ocean energy. According to Jain et al., [

143], there are numerous ocean engineering applications of ANN. The availability of renewable energy resources has been extensively covered by Iglesias et al. Authors of [

144] have discussed the potential of wave farms producing energy located in the Canary Islands, which will eventually be one of the first islands to run exclusively on renewable energy.

The studies [

145,

146,

147,

148,

149,

150,

151,

152,

153] discuss the involvement of several single and mixed AI techniques for ocean energy and the

Table 5 summarizes the key findings. The sea level variation along Western Australia’s coast is forecasted using a three-layer BPNN approach (correlation coefficient of 0.7–0.9) [

145]. The BPNN algorithm with six different options for number of neurons in the layer has been used by Londhe et al. [

146] to estimate ocean wave conditions for one day with decent precision (for lead times of 12 hours, there is a 67% correlation between the predicted wave height). Three architects analyzed data obtained from Tasmania between 1985 and 1993 (

of 0.92) to forecast wave parameters using the BPNN approach, which takes the coastal environment factors as input [

147]. Using sixty datasets and thirty US rivers, the longitudinal dispersal coefficient in streams was predicted. A study by Toprak et al. [

148] employed the RBFNN, BPNN, and Generalized Regression Neural Network (GRNN). The FLC has been created by Chen et al. [

149] to lessen the effects of external wave force in the ocean and the proposed method demonstrates good stability. Ghorbani et al. [

150] predict sea level using the GP and ANN. The GP prediction accuracy (MSE of 22.5–28.2) outperformed the LM algorithm-based BPNN.

To increase the prediction accuracy, mixed AI methods [

152,

153] and ANFIS [

154] approaches have also been employed. Karimi et al.’s investigation [

153] highlights the effectiveness of eleven different ARMA model variants, BPNN (LM), BPNN (CG), BPNN (GD), and ANFIS (five variations, each with a unique membership function) in sea level prediction. Results from ANFIS and ANN approaches are nearly identical, however they outperform ARMA techniques. For wave hindcasting, a hybrid method combining the Numerical Wave Model (NWM) and BPNN is employed [

151]. In comparison to the BPNN and NWM methods, the hybrid strategy performs better. The authors in [

152] have developed a hybrid intelligence system that utilizes SVR and case-based reasoning to improve

flux prediction and investigate the understanding of how air and ocean interact. Different applications of AI in ocean energy are demonstrated in

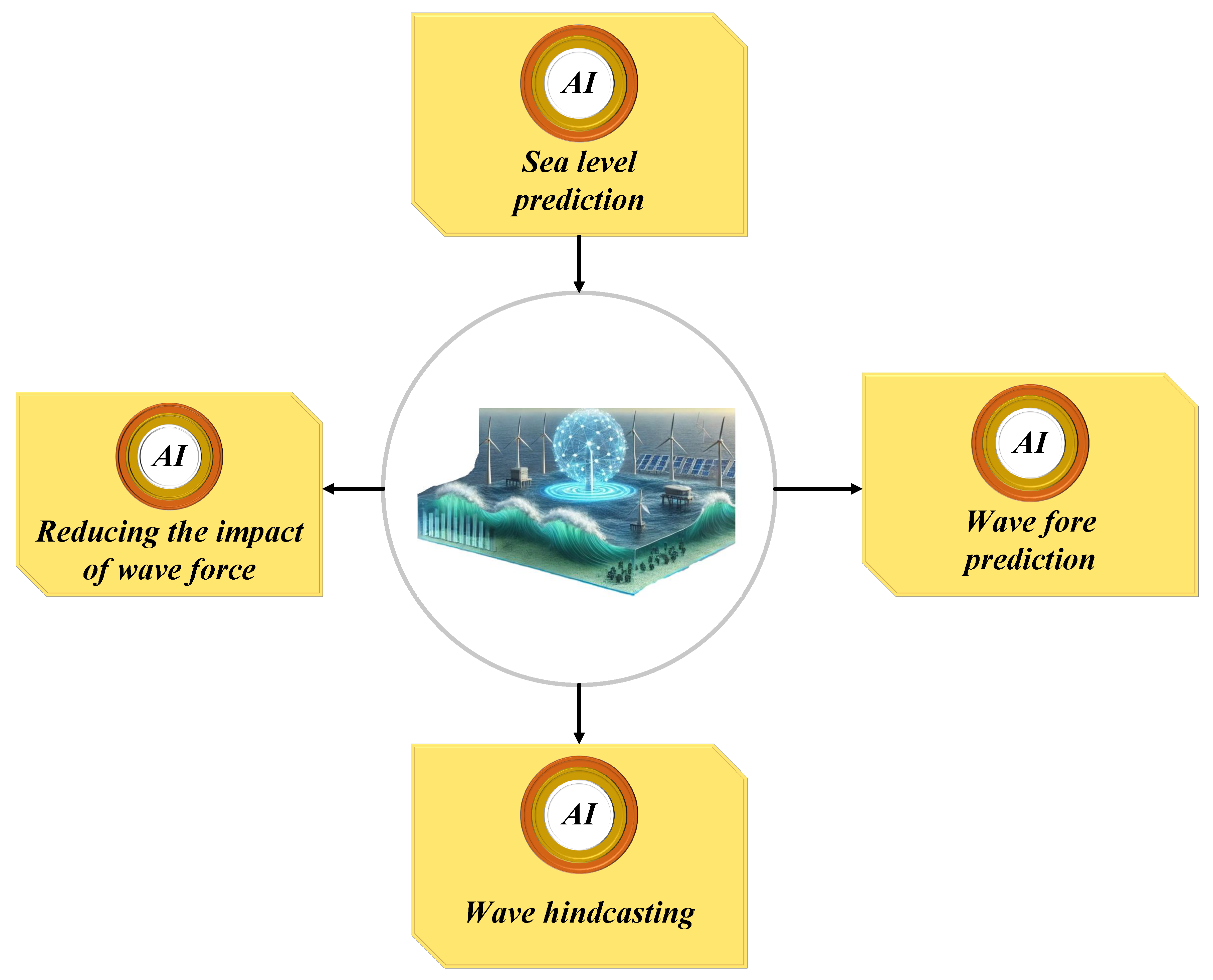

Figure 3

3.6. AI in Bioenergy

Shabani et al. [

154] provide a succinct overview of predictable and stochastic mathematical models for foresting biomass energy, optimization and the ideal supply chain architecture in renewable energy generation. Several studies [

155,

156,

157,

158,

159,

160,

161,

162,

163,

164,

165,

166,

167] describe the usage of both standalone and combined AI systems for analysis of bioenergy, which is summarized in

Table 6. Studies [

155,

156,

157,

158,

159,

160] about bioenergy use ANN architectures. Yang et al. [

155] forecasts the density and fuel’s cetane number for diesel using BPNN, RBFNN, GRNN, and Recurrent Neural Network (RNN) to detect the fatty acid composition (BPNN performs best in this case). To measure the amount of methane in biomass from bioreactors by using temperature, alkalinity, conductivity, pH, sulfate, BOD, and chloride as input parameters, ten different kinds of BPNN are analyzed in [

156,

157,

158,

159](RMSE ranges from 0.00263-0.00250). The RBFNN trained with inputs of pressure, blend, load, compression ratio, and injection time (accuracy range 69–96%) for the performance of biodiesel engines (engine emissions, exhaust temperature, and thermal efficiency/energy consumption of the break) is examined in [

160]. To estimate the density, viscosity, water and methanol content, and other properties of biodiesel, the polynomial and Spline Partial Least Squares Regression (SPLS), Principal Component Regression (PCR), Multiple Linear Regression (MLR) are studied and compared with the BPNN (the BPNN performed better than the other approaches) [

159]. Apart from SVM and KNN [

161], PSO [

162], and GP [

163], ANN has also been applied in bioenergy analysis work. Based on Near-Infrared (NIR) data, Balabin et al. [

161] classified biodiesel into ten categories (based on origin) using regularized discriminant evaluation, KNN, SPLS, and SVM algorithms. The SVM produces an accuracy for classification that is superior to the other three approaches. To optimize the biomass supply chain (flows from the producing sources), an improved version of PSO is used [

162]. A comparison is made between the performance of the current Higher Heating Value (HHV) models and biomass fuels estimated HHV utilized by GP and BPNN [

163]. The GP and BPNN forecasted accuracy is superior to that of the traditional models (RMSE of 0.942 and 0.987, respectively).

Hybrid AI techniques are also applied in the investigation of bioenergy [

164,

165,

166,

167]. For the years 1964–2006, Koutroumanidis et al. [

164] estimated fuelwood costs in Greece using ARIMA, ANN, and a hybrid of ANN-ARIMA. Compared to the ANN and ARIMA approaches separately, the ANN-ARIMA model predicts better estimation (MAPE of 14%). A hybrid system that maximizes heat transfer and enhances biomass boiler cleaning using fuzzy logic and ANN saves 12-gigawatt hours annually [

165]. Methane may be produced from waste digesters using a hybrid AI method based on BPNN and GA [

166]. The hybrid approach produces 6.9% more methane when the settings are optimized. Similar hybrid technology is applied in a different study [

167] to optimize the production of biogas from cow manure, banana stems, rice bran, paper waste, and sawdust which resulted in produciton of

of biogas. Various fields of bioenergy resources in which AI can play an active role are demonstrated in

Figure 4.

3.7. AI in Hydrogen Energy

Petrone et al. [

168] summarized model-based machine learning methods for proton exchange membranes fuel cell system (PEMFC) diagnosis. Similarly, for a related topic, three sorts of non-modal-based methods, including statistics, signal processing, and AI techniques, are described in [

169]. A summary of scientific approaches consisting of AI techniques in hydrogen energy is provided in

Table 7 and is documented in multiple studies [

40,

170,

171,

172,

173,

174,

175,

176,

177,

178,

179,

180,

181,

182,

183,

184,

185,

186,

187,

188,

189,

190,

191,

192,

193,

194]. The ANN is a commonly used technique in the hydrogen energy industry [

40,

170,

171,

172,

173,

174,

175,

176,

177,

178]. Three AI techniques, namely BPNN, MGGP, and SVR are employed to forecast the output voltage of Microbial Fuel cells (MFCs), with MGGP yielding the highest accuracy [

170]. The

hydrogenation activity is predicted by BPNN [

171]. BPNN with eleven training approaches are used to forecast the impact of hydrogen vehicle engine operating parameters on

, carbon monoxide,

, and hydrocarbon emissions [

172] and record 100% accuracy in the carbon emission prediction. The PEM fuel cell’s stability and fault detection are observed using the Bayesian method and LM with BPNN [

173]. The cathode temperature and voltage of the fuel cell with a Polymeric Electrolyte Membrane (PEMFC) are predicted with good precision [

174]. Using two inputs, throttle position and engine speed, the parameters of hydrogen engines (mass airflow (MAF)) are forecasted with the twelve distinct training techniques of BPNN [

195]. Moreover, BPNN is used in other studies [

175,

176,

177,

178] to forecast the Solid Oxide Fuel Cell (SOFC) stack voltage [

177], parameters, emissions of the hydrogen engine [

175] (RMSE of ±

), the MFC power density (RMSE of

for a single configuration), and the hydrogen-functionalized graphene tensile strength prediction [

176].

Hydrogen energy analysis has also been carried out using fuzzy logic methods [

179,

180,

181] and EU techniques [

182,

183,

184]. Fuel Cell Hybrid Vehicles (FCHV) employ a parameter-based fuzzy logic controller optimized with GA to regulate the amount of hydrogen consumed [

181]. The SOFC’s current density properties are modeled by a recurrent fuzzy system [

180], and the ignition time of a hydrogen automobile is predicted using a fuzzy logic technique utilizing three distinct kinds of membership functions [

179]. The PSO is used in addition to fuzzy logic and GA for FCHV energy optimization [

182]. Nath et al. [

183] reviewed the use of GA, PCA, and BPNN in modelling of hydrogen generation. The Bird Mating Optimization (BMO) method for modeling the PEMFC system is proposed by Askarzadeh et al. [

184].

Studies [

185,

186,

187,

188,

189,

190,

191,

192,

193,

194] described the ANFIS and other hybrid AI methods. ANFIS is utilized in the forecast of various safety parameters of hydrogen (such as hydrogen pressure, flow rate and explosive limit), applied with ten input requirements [

186]. Based on various training procedures, the effectiveness of ANFIS is compared with different types of eleven BPNN (RMS of 1.4 in the ANFIS-powered hydrogen pressure forecast). The parameters of Stack Current and Voltage (SOFC) are predicted using ANFIS and the results are compared with the ANN approach (RMSE of less than 2 for ANFIS forecast). Emissions (CO,

, HC and

) from the hydrogen automobile were forecasted using ANFIS and BPNN-LM. The BPNN performs better than ANFIS in this regard (HC emission RMSE of 1.58% using the BPNN) [

187]. The performance of the PEM electrolyzer (

flow rate, system, and stack efficiencies) is predicted using ANFIS (the predicted inaccuracy of hydrogen flow rate is 1.06%) [

188]. Effective PEMFC cell voltage prediction is possible using ANFIS [

189]. A hybrid AI method based on full logic and wavelet technique has been applied to decrease HEV energy usage (0.06962 kMol

), and the findings are compared with RBFNN and BPNN [

190]. High precision temperature forecasting of the hydrogen reactor is achieved by using a hybrid technique based on SVR and PSO, and its performance is compared with that of SVR and BPNN [

190]. When compared to PSO and GA, the hybrid ABC algorithm outperforms other approaches in terms of minimizing the Sum of Squared Errors (SSEs) for parameteric prediction of PEMFC [

194]. Combining GA and BPNN results in a 54 ml/g increase in biohydrogen output [

193]. A similar set of techniques is applied in different research [

192] to maximize the SOFC cell characteristics (1.705% standard error of prediction achieved).

3.8. AI in Hybrid Renewable Energy

In [

196,

197,

198], a brief discussion about the application of AI techniques in the hybrids RERs is presented. An overview of the methods developed for ideal sizing has been provided by Luna Rubio et al. [

196]. Zhau et al. [

197] presented the design techniques for the solar-wind hybrid system, and [

198] provides an overview of the various EA approaches used in optimization.

Table 8 compiles a few hybrid RER applications using both the single and hybrid AI techniques [

199,

200,

201,

202,

203,

204,

205,

206,

207,

208,

209,

210]. For a hybrid RER system based on a water power source, BPNN is utilized to predict generator state (on/off) and power [

199]. FLC has been employed by Chavez-Ramirez et al. [

200] for energy management, while the BPNN technique was used for hybrid RE power prediction. A different study [

201] used PSO in conjunction with the FLC and Cuckoo Search (CS) algorithms to investigate the energy control of a hybrid renewable energy system (with the CS and a levelized energy cost of 2.01

$). Hakimi et al. [

202] use PSO to optimize the hybrid RER system’s size in an attempt to cut expenses. The hybrid RER system’s operation is optimized using an improved GA, which outperforms the conventional GA approach [

203]. The hybrid RER system’s performance parameters (energy cost, net current cost, and generating cost) are optimized using the bee algorithm [

204]. GA has been used by Khatib et al. [

205] to maximize the storage capability, size of PV array, and windmill size of hybrid wind-photovoltaic system. In hybrid energy (photo voltaic, fuel cell, windmill) systems, the optimization of size and distribution is carried out using a multi-objective ABC method [

206], which produces a high voltage stability index. The hybrid wind-PV-diesel system’s size optimization is done by Markov-based GA [

207].

According to [

208], four methods, PSO, Simulated Annealing (SA), Tabu Search (TS) and Harmony Search (HS), perform better concerning wind-PV-battery and wind-PV-FC system size optimization. The PSO performs better than the other three techniques. In hybrid AI approaches, the wind-PV-battery system size is optimized using ANFIS to minimize production costs. Additionally, the hybrid optimization (HO)-GA and the hybrid renewable energy optimization model for electric power are compared with ANFIS’s performance [

209]. Fuzzy logic-based and ANN controllers are devised as hybrid AI technology to manage power flow between energy and storage units of hybrid RER systems and to generate high storage of charge [

210].

The ANFIS is also used for estimating wind power [

211], biodiesel modeling [

212], and radiation of solar [

213]. The ARIMA-SVR is used for tidal energy real-time estimation in [

214]. For solar radiation forecast, empirical decomposition, wavelet decomposition, ANN, and autoregressive approaches are used [

215]. In PV system load estimation, enhanced and hybrid ANN are used [

216]. Several recent studies [

217,

218,

219,

220,

221,

222,

222] have also covered the specific applications of AI methods, including solar PV system power tracking [

218], estimation of wind and solar energy [

218,

219], decision systems in RER [

221], PV solar systems controllers [

223], and energy management [

222].