1. Introduction

Tomato (Solanum Lycopersicum) is a common vegetable crop that is universally consumed (Tejada-Alvarado et al., 2023). It is a subtropical and annual plant that belongs to nightshade family which has high sunlight and temperature requirements for growth (Lee et al., 2016; Vermeiren et al., 2020; Chikkeri et al., 2023; Alani et al., 2023). Tomato has a diploid chromosome number of 2n=2x=24 (Waiba et al., 2021; Brake et al., 2022). Domestication of tomato started from the Andean region of Peru and Ecuador, and extended to Mesoamerica (Ercolano et al., 2020). Solanum lycopersicum is the most cultivated of the wild relatives that include Solanum juglandifolium, Solanum chimiewelskii, Solanum neorickii, Solanum pimpinellifollium, Solanum sitiens, Solanum chilense, Solanum galapagence, Solanum ochrantium, Solanum corneliomuelleri and Solanum habrochaites (Gutierrez, 2018). The determinate type of tomato is small and has regulated growth while the indeterminate species are generally large and have continuous growth (Altemimi et al., 2017). Different soil types are used in tomato cultivation but sandy loamy soil is best because of good water drainage (Tuan, 2015). Tomato does best between pH of 6.0 to 7.0 and requires high amount of nutrients for growth and productivity. Tomato fruits have many nutritive components that include lutein, β-carotene and lycopene that have health advantages associated with reduced cancer rate and diseases of the heart (Islam et al., 2023; Ahmed et al., 2023). There are many factors that cause poor yield of tomato production which include attack by pathogens (Arah et al., 2016).

Fungi is one of the major pathogens that cause spoilage of tomato (Onuorah and Orji, 2015; Bello et al., 2016; Ezikanyi, 2016; Sajad et al., 2017; Lamidi et al., 2020). Phytophthora infestans (P. infestans) and Aspergillus niger (A. niger) are among fungi that cause serious effects during infection of various parts of tomato (Santos et al., 2016; Mekapogu et al., 2021; Gwa and Lum., 2023). High moisture composition of fruits makes tomato prone to attack by these fungi which causes lots of health problems to man due to mycotoxins secreted (Santos et al., 2016; Agbabiaka et al., 2020). Factors such as rain, dew and irrigation support the germination of fungi spores on fruit surfaces that subsequently penetrates tomato epicarp, while fragile and injured tissues of tomato are the major sources of entry by fungi pathogens such as P. infestans and A. niger.

Extensive studies on spoilage of tomato by fungi has been done (Abioye et al., 2021; Sola et al.,2022; Sobowale et al., 2022; Danaski et al., 2022; Ya et al., 2022; Sani et al., 2023; Akotowanou et al., 2023; Okolo and Abubakar, 2023). However, information on genetic resistance of tomato to P. infestans and A. niger is scarce. Additionally, the estimates of heritability, genetic advance and variance components on morphological characteristics of tomato to disease resistance of fungi Trichoderma, Alternaria alternata, Alternaria solani, Alternaria tomatophila, Alternaria linariae, and Septoria lycopersici has also been studied (Ohlson and Foolad, 2016; Bharathkumar et al., 2017; Kouam et al., 2018; Plouznikoff et al., 2019; Rubio et al., 2019; Panthee et al., 2024). The study of heritability estimates, genetic advance and components of variance on resistance of tomato characters to P. infestans, as reported in the works of Sullenberger et al. (2018); Copati et al. (2019), Elafifi et al., (2019), Jia and Foolad, (2020), Panthee et al. (2018) were limited to ancestral and wild forms like Solanum Pimpinellifolium and Solanum habrachaites. Presently, there is limited knowledge on the resistance of morphological characters in currently cultivated germplasm accessions of tomato to P.infestans, while there is no traceable information on resistance of the agro-morphological characters of tomato to A. niger. Therefore, this study investigated genetic resistance of thirty tomato accessions to P. infestans and A. niger, the effect of these fungi on the chromosomes and heritability estimates, genetic advance and component of variance on resistance of morphological characters in tomato.

4. Discussion

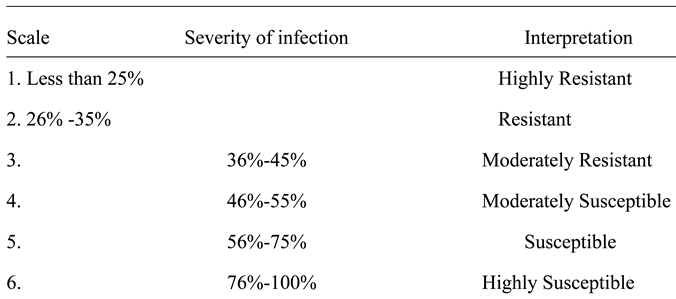

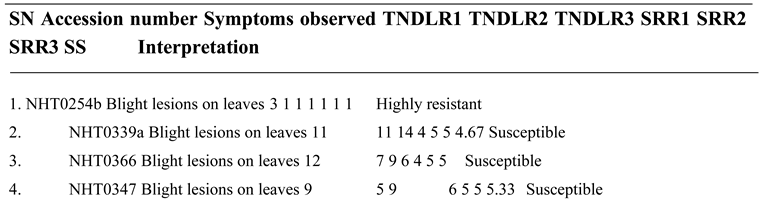

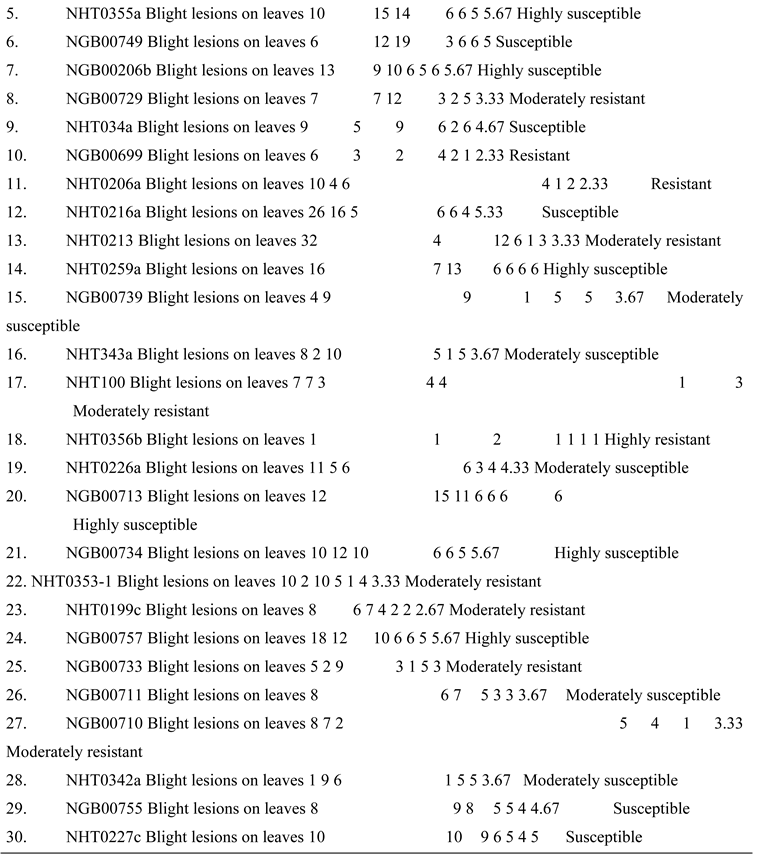

4.1. Genetic Resistance of Accessions to P. infestans and A. niger

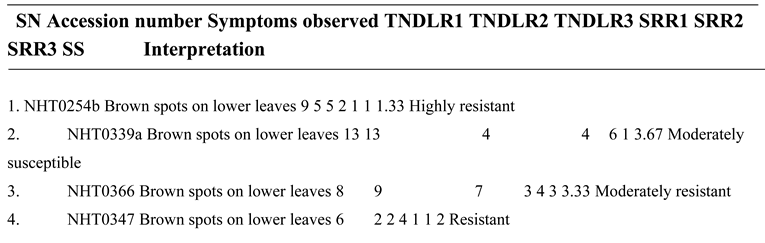

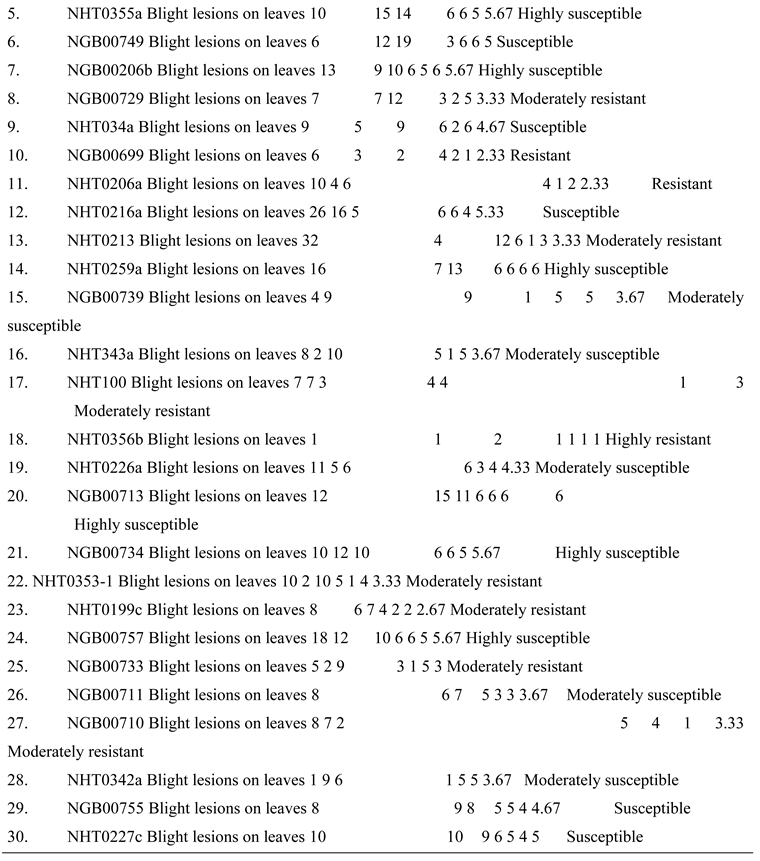

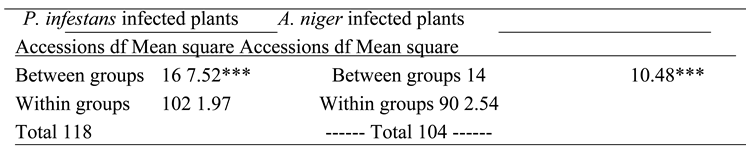

High level of resistance reported in NHT0254b and NHT0343b is consistent with Arafa et al. (2017) that reported similar findings in LA1777 accession. The resistance of NGB00699 and NHT0206a is also in line with LA1352, LA2855, LA1347, LA1718 and LA1295 that also showed good level of resistance. Occurrence of moderate resistance in NGB00729, NHT0213, NHT100, NHT0353-1, NHT0199c, NGB00733 and NGB00710 is in accordance with LA1269, LA1578, LA3152 (Ph-2), LA3151 (Ph-2) and LA4286 (Ph-3) accessions. Moderate susceptibility as reported in NGB00739, NHT343a, NHT0226a, NGB00711 and NHT0342a is similar to LA2196. Susceptibility of NHT0339a, NHT0366, NHT0347, NGB00749, NHT034a, NHT0216a, NGB00755 and NHT0227c is consistent with LA1252, LA1772, LA1223, LA1378, LA1367, LA1340, LA0716, LA1674, LA1478, LA1594, LA2646 and LA2009 (Ph-1) accessions while, high susceptibility in NHT0355a, NGB00206b, NHT0259a, NGB00713, NGB00734 and NGB00757 is in accordance with LA1303, LA1302, LA0751, LA1649, LA0443, LA1586, LA1561, LA0413, LA2147, LA1579, LA1617, LA1633, LA2391, LA3123, LA3161, LA1246, LA0375, LA0114, LA1237, LA1469, LA1256, LA1242, LA1343, LA1935, LA0446, LA2581, LA1333 and Super Strain B accessions of Arafa et al. (2017).

High level of resistance observed in NHT0254b, NGB00749, NGB00729, NGB00699, NHT0213, NHT356b and NHT0199c is in line with the work of Aguilar-Gonzalez et al. (2017) that reported high level of resistance of tomato to A. niger in three treatments using essential oil. The level of resistance observed in NHT0347, NGB0206b, NHT70206a, NHT0216a, NHT100 and NHT0226 is consistent with similar study that used 3/4M treatment which revealed 8/20 positive cases after inoculation with A. niger while, moderate resistance observed in NHT0366, NHT0355a, NHT034a, NHT343a, NGB0734, NGB00757, NHT0342a, NGB00755 and NHT0227c is also in line with Aguilar-Gonzalez et al. (2017) after observing 10/20 infection rate on tomatoes after inoculation of A. niger using 1/2M concentration of essential oil treatment. The susceptibility of NHT0339a, NHT0259a, NGB00739, NGB00713, NGB03531, NGB00733, NGB00711 and NGB00710 is consistent with the findings of Sale et al. (2018) that reported susceptibility of Siria and UTC varieties of tomatoes (Solanum lycopersicum).

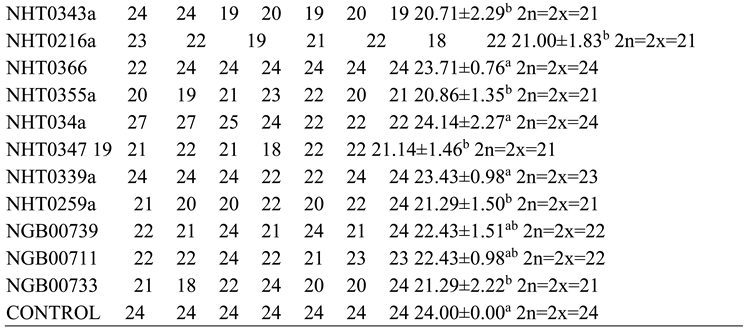

4.2. Variations in Chromosome Number and Ploidy Levels after Fungi Infection

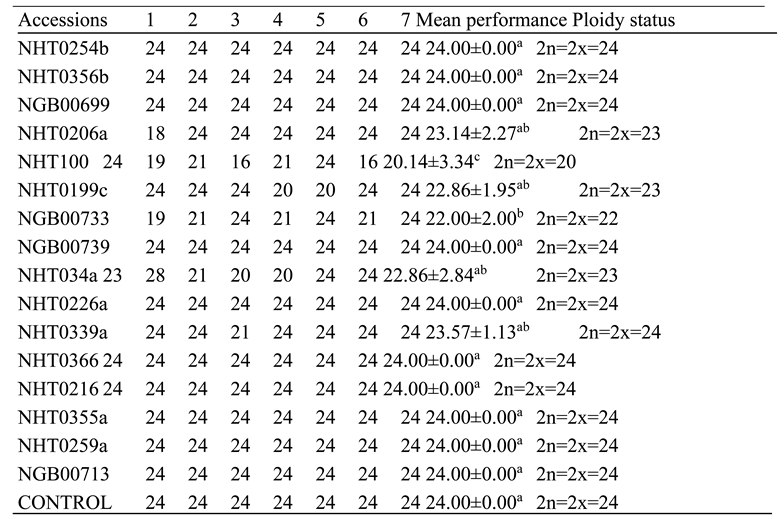

This study revealed that variations in chromosomes of tomato occur during infection by P. infestans and A. niger which highlights intricate host pathogen interaction and likely cytological effects. Infections by these pathogens trigger genomic stress in tomato which potentially lead to alterations in chromosomes. The P. infestans that causes late blight can induce significant variations in the regulation of genes related to resistance and control of reactive oxygen in tomato cultivars which can affect genomic composition that include changes in chromosome numbers especially in susceptible tomato accessions (Ayala-Usma et al., 2021; Liu et al., 2021). Similarly, A. niger is associated with metabolic changes that can disturb genome stability. This study suggests that chromosome instability such as deletions that lead to aneuploidy can occur in tomato during infection by both fungi as a result of pressure from the pathogen with the aim of compromising the defense mechanisms of tomato (Panthee et al., 2024).

The deletions observed in NHT0206a, NHT100, NHT0199c, NGB00733 and NHT034a treated with P. infestans is not in line with Bal and Abak. (2007) and El-Mansy et al. (2021) that reported the least number of chromosomes in tomato roots to be 2n=2x=24 which is the diploid state. This suggests that chromosomal deletions is a mechanism used by P. infestans during infection. Similarly, the highest chromosome numbers of 2n=2x=26 reported by Bal and Abak. (2007) and El-Mansy et al. (2021) is also not in accordance to the diploid (2n=2x=24) chromosome number observed in NHT0254b, NHT0356b, NGB00699, NGB00739, NHT0226a, NHT0339a, NHT0366, NHT0216a, NHT0355a, NHT0259a, NGB00713 and control. The differences in results observed in present study compared to Bal and Abak. (2007) and El-Mansy et al. (2021) can be attributed to differences in treatments used in the various experiments. The occurrence of 2n=2x=24 chromosomes in the accessions earlier mentioned is in accordance with Wang et al. (2006), Song et al. (2012), Gerszberg et al. (2015), Singh et al. (2015), Mesquita et al. (2019) and Waiba et al. (2021).

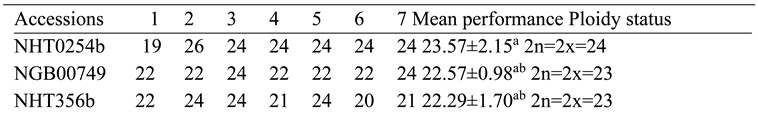

Chromosomal deletions were observed in NGB00749, NHT356b, NHT0343a, NHT0216a, NHT0355a, NHT0347, NHT0339a, NHT0259a, NGB00739, NGB00711 and NGB00733, while NHT0254b, NHT0366, NHT034a and control were observed to have diploid state of 2n=2x=24 chromosomes in A. niger treated plants. The deletion of chromosomes in present study is not in line with Bal and Abak. (2007) and El-Mansy et al. (2021) that reported 2n=2x=26 chromosomes in tomato. The variations observed between both studies can be attributed to differences in the treatments used between the two experiments. The reduction of chromosomes observed in some accessions imply that A. niger functions by deleting chromosomes in susceptible accessions of tomato. The diploid state (2n=2x=24) of chromosomes observed earlier is consistent with reports from Brasileiro-Vidal et al. (2009), Pavan et al. (2009), Bhala and Verma. (2018) and Brake et al. (2022).

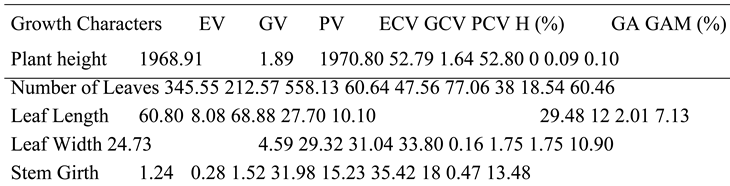

4.3. Variance Components and Heritability, Genetic Advance of Growth Characters

The PV was highly susceptible to P. infestans, as supported by EV compared to GV for growth characters. The ECV was high, indicating a strong influence on PCV, which was highest over the GCV, suggesting susceptibility of growth characters to the fungus. The H also revealed susceptibility of growth characters to P. infestans. The GA was low for all characters, while GAM was moderate, with the exception of the NL, which was high. Low GA compared to H further confirms that the growth characters were susceptible to P. infestans. Moderate GCV, GAM and high PCV scores reported in this study for PH are not consistent with the work of Meena et al. (2018), which reported low GCV, GAM and PCV scores for PH; however, low scores for GA are consistent with this study.

The higher PV than GV in the present study is consistent with PV and GV by Pooja et al. (2022). The high ECV, GCV and PCV for NL in present study are not in line with the moderate ECV, GCV and PCV scores of Phom et al. (2016). The observed differences can be attributed to different genotypes and treatments used between Nigeria and India. The high PCV and moderate GCV for LL are not consistent with moderate PCV and low GCV observed by Yadav et al. (2016). Moderate GAM in this study is also not in accordance with low GAM, while low GA is consistent with GA reported by Yadav et al. (2016). The H in this study showed that LL was susceptible to P. infestans, while that of Yadav et al. (2016) reported the strongest effect to be from genetic factors. Differences between accessions, genotypes, and treatments used can account for the observed variations.

Similarly, high PCV and moderate GCV for LW are further in line with reports from Yadav et al. (2016), which observed PCV and moderate GCV values. The moderate GAM in this study is not in line with GAM reported by Yadav et al. (2016), while low GA is in accordance with the GA of similar studies. However, H for LW in this study implied susceptibility, while Yadav et al. (2016) observed the strongest influence on observed phenotypes to be resistant. The differences between accessions, genotypes, and treatments used can account for the observed variations. The low GV and higher PV for SG in this study are in line with GV and PV observed by Tripura et al. (2016); however, H in present study reported implied susceptibility, while Tripura et al. (2016) observed that a greater portion of observed phenotypes were influenced by genes. The differences can be attributed to the different species of Solanum plants used in the two experiments.

The PH was susceptible to A. niger. The PV had a higher score than GV, indicating susceptibility to the fungus as supported by high EV. The PCV also confirmed a stronger influence of A. niger on observed phenotypes over resistance genes, as seen by GCV, and this was supported by high values observed in the ECV. The H shows that there was no effect of resistant genes on observed phenotypes, and this was further supported by low GA and GAM. The higher PV than GV scores for PH in this study are consistent with PV and GV reported by Shah et al. (2022). The H shows that observed variances in PH are purely caused by the effect of A. niger, whereas H reported by Shah et al. (2022) implies that greater proportion of observed variations are influenced by dominant genes.

This is corroborated by the low GAM and higher GAM between the two studies. The differences in accessions, genotypes, and treatments used for the two experiments can account for observed variations. The effect of A. niger was also greater on NL than genetic effect. The higher PV than GV, which is confirmed by EV, which was highest, is proof of strong effect of A. niger on observed variations for NL. This is further supported by higher scores for PCV than GCV, which is supported by ECV, which was highest. The H for NL reports that lesser proportion of observed characters were influenced by genes, while greater percentage was influenced by the fungus, and low GA further agrees that the fungus had the strongest effect. The higher PV and GV observed in this study are in line with the PV and GV reported by Saini et al. (2018).

The higher PCV than GCV reported in this work is also in line with PCV and GCV findings of Saini et al. (2018). However, H in this study reveals that A. niger had the strongest influence on observed characters, while Saini et al. (2018) reported that higher portion of observed characters were influenced by genes. This is further corroborated by low GA in this study compared to high GA reported by Saini et al. (2018). The different accessions, genotypes, and treatments used in the two studies can account for the observed differences. The effect of A. niger was strongest on LL for the observed variations. The PV that was higher than the GV is consistent with the PV and GV observed by Saini et al. (2018). Similar trend observed in PCV and GCV is also consistent with Saini et al. (2018).

The H for LL in this study showed that lesser percentage of the observed variances were influenced by genes, whereas greater proportion of the observed variances were influenced by the treatment. This is not consistent with the study by Saini et al. (2018), that reported higher proportion for effect of genes on observed characters than environmental factors on observed variances. The different accessions, genotypes, and treatments used can account for observed differences. Low GA and GAM for leaf length in this study further support the strong effect of A. niger on observed phenotypes. The H for leaf width shows that dominant genes are responsible for the observed variances. This is consistent with the report of Saini et al. (2018), which found that higher proportion of the observed variances for LW were influenced by dominant genes.

The treatment effect had strongest influence on the observed variations for LW. The PV was higher than the GV, which was further supported by the high EV. A similar trend was observed for PCV, GCV, and ECV, while GA and GAM were low and moderate, respectively. The PV that was higher than GV for SG in this study is consistent with the findings of Tripura et al. (2016) for PV and GV. However, H for SG showed that lesser portion of the observed phenotypes were influenced by genes, while Tripura et al. (2016) observed that higher proportion of observed phenotypes for SG were influenced by genes. The differences can be attributed to different plants of the Solanum family used in the various experiments.

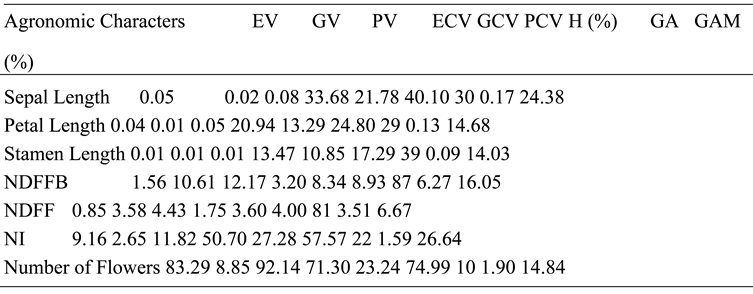

4.4. Variance Components, Heritability and Genetic Advance of Agronomic Characters

The PV was higher than GV for SL, followed by EV, implying that P. infestans had a greater effect on SL than resistance genes, as supported by high EV. Similarly, PCV was higher than GCV, while ECV was relatively high, further supporting the effect of P. infestans on SL. The H further confirms that the fungus had a stronger effect on SL than genetic factors. Low GA and GAM also prove the effect of the treatment on the observed variances. PV was further higher than GV in PL, while EV was next to PV. The PCV similarly higher than GCV, while ECV was also relatively higher. This suggests that P. infestans had strongest effect on the observed variations. The H showed that lesser proportion of the observed variations in PL were influenced by genes, while most of the observed variations were influenced by the treatment, which further confirms that P. infestans had the strongest effect on PL. The GA was low, while the GAM was moderate.

Low GA further confirms the strength of the treatment based on the observed variations. The EV, GV, and PV were same for STL; however, PVC was higher than GCV, while ECV was also relatively high, implying that the fungus had the strongest effect on the observed phenotypes. The H reveals that a lesser percentage of the observed variations are from dominant genes, while higher proportion of the variations were from the effect of P. infestans. The GA was low, while GAM was moderate. Low GA further confirms that the strongest effect on observed variations was from the fungus. The PV had the highest score for NDFFB, while GC was next and EV was least. This suggests that the resistance genes had stronger influence on the observed phenotype compared to the treatment. The PCV, GCV, and ECV also followed the same pattern, implying that the strongest effect on the observed variations was genetic in nature.

The H showed that most of the observed variations were influenced by dominant genes, while a lesser portion were influenced by P. infestans. This confirms that the resistance genes had stronger effect on the observed phenotypes. The GA and GAM were respectively low and moderate. Low GA further confirms that the dominant genes had stronger effect on NDFFB. The PV was highest for NDFF, while GV was lower and EV was least. This suggests that the influence on observed variations is largely genetic. Similarly, PCV was higher than the PCV, while the ECV was least likely, suggesting a stronger effect of genes on observed variations. The H reported that higher percentage of the observed variations were from dominant genes, while a lesser proportion were influenced by the fungus. This confirms that the dominant genes are the major influencers NF. The PV was higher than the GV for NI, while EV was relatively high, suggesting that the treatment effect was stronger than genetic effect. A similar trend that was observed for PCV, GCV, and ECV further agrees that P. infestans had a stronger effect than genes on observed phenotypes.

The H showed that lesser portion of observed variances were influenced by genes, while greater proportion was influenced by the treatment. This confirms that the treatment effect was stronger than genetic effect. The GA and GAM were respectively low and high. Low GA further confirms that the effect of P. infestans was stronger than that of dominant genes. The PV for NF was higher than the GV, while the EV was relatively high implying that the fungus effect was stronger than resistance genes. Similar trend was observed for PCV, GCV, and ECV, while H revealed that a smaller percentage of the observed variances were influenced by genes than greater portion that was affected by P. infestans. The GA was low, while GAM was moderate. Low GA further confirms that the fungus effect was stronger than genetic factors. The genetic effect that had stronger effect on NDFF is in line with Singh et al. (2015). The NI that was largely influenced by P. infestans is consistent with observations of Pandey et al. (2018). The fungus effect that was strongest for NF in present study is also in line with Pandey et al. (2018).

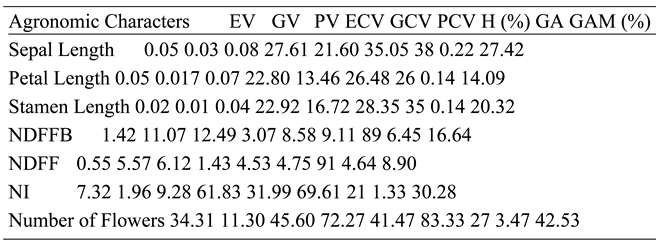

The PV was higher than GV for SL, while EV was also relatively high, suggesting that the effect of A. niger on SL was stronger than that of dominant genes. The PCV was also greater than GCV, while ECV was relatively high, further implying that A. niger had stronger effect on SL than resistance genes. The H shows that lower percentage of observed phenotype was influenced by genes, while a greater portion was from the effects of A. niger. The GA and GAM for SL were respectively low and high. Low GA further supports stronger effect of fungus compared to genetic factors. The PV was greater, followed by EV and GV for PL, implying that the effect of A. niger was stronger on the observed variances than genetic factors. Similar trends were followed for PCV, ECV, and GCV, further supporting that the fungus effect was stronger. The H reported a lesser percentage of the observed variances for SL were influenced by genes, while higher proportion were due to the effects of A. niger. This confirms that the treatment effect was stronger than the effect of the dominant genes.

The GA and GAM were respectively low and moderate. The low GA further confirms that A. niger had stronger influence than resistance genes for the observed variations in PL. This implies that the effect of A. niger was stronger on STL than genetic factors as implied by PV that was higher, followed by EV and GV, respectively. The PCV was greater than GCV, followed by ECV, further suggesting strength of A. niger over dominant genes for STL. The H revealed that lower proportion of observed variances for STL were influenced by dominant genes, while most portion was from the treatment effect. This confirms that the effect of A. niger on STL was stronger than that of genetic factors. The GA and GAM were low and high, respectively. Low GA further confirms that the fungus effect was stronger than genetic factors. The PV was slightly above GV, while EV was low for NDFFB. A similar trend was observed for PCV, GCV, and ECV; however, H showed that most of the observed variations for NDFFB were controlled by dominant genes, while lesser were from treatment effect.

This shows that genetic factors had stronger effects on NDFFB. The GA and GAM were respectively low and moderate. PV was higher than GV for NDFF, while EV was least; however, the difference between PV and GV was not much. Similarly, the same trend was observed for PCV, GCV, and ECV. The H for NDFF reports that most of the observed phenotypes were influenced by genes, while a little portion were from the fungus. This suggests that the stronger influence on the observed variations was from genes; however, GA and GAM were low. The PV was higher than GV for NI, while EV was also relatively high, suggesting that the effect of A. niger on NI was stronger than genetic factors. The PCV was also higher than GCV, while ECV was also relatively high, further supporting the stronger effect of treatment than genes. The H showed that a little portion of the observed variances were influenced by genes, while higher proportion was from the treatment. This confirms that the effect of A. niger on NI was stronger than resistance factors.

The GA and GAM were respectively low and high. Low GA further proves that the effect of A. niger was strongest on NI. The PV for NF was higher than GV, while EV was also high, suggesting that the observed phenotypes for NF were from the effect of A. niger rather than genes. The PCV was higher than GCV, while ECV was also high, further implying a stronger effect of treatment compared to genetic factors. The H revealed that lesser proportion of the observed phenotypes were controlled by genes, while a greater portion was influenced by the fungus. This confirms that the effect of A. niger was more on NF compared to genetic factors. The GA and GAM were respectively low and high. The low GA further proves the stronger effect of treatment over genetic factors. The stronger genetic effect that was observed for NDFF is in line with Mohamed et al. (2012). The NI that was influenced by treatment in this study is in line with Pandey et al. (2018). The NF that was influenced by treatment is in accordance with Pandey et al. (2018).

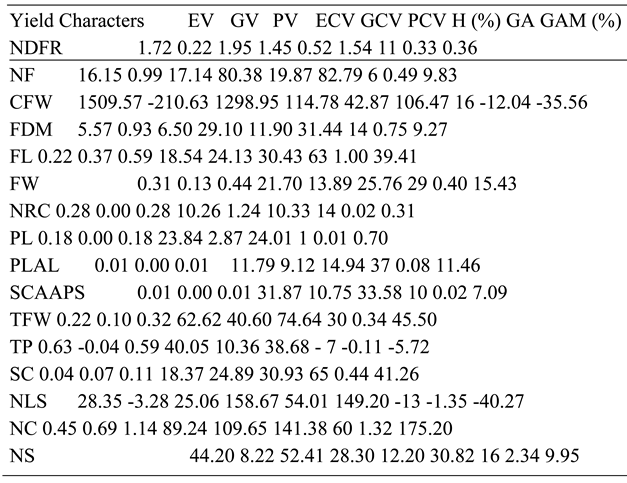

4.5. Variance Components, Heritability and Genetic Advance of Yield Characters

The NDFR, NFS, CFW, FDM, FW, NRC, PL, PLAL, SCAAPS, TFW, TP, NLS, and NS were strongly influenced by the effect of P. infestans rather than genes. This was indicated by high PV score for all the mentioned characters, which is backed up by a relatively high EV compared to GV. The PCV for all the mentioned characters was also high, while the ECV was higher than the GCV, further implying that treatment effect was stronger than the effect of resistance genes on observed variances. The H for similar characters showed the percentage of observed variances that were influenced by dominant genes were respectively lower than the effect of P. infestans for the characters. These confirm that the treatment effect was stronger than those of genetic factors for the observed characters. The low genetic advance for the tested characters earlier mentioned also confirms the stronger effect of P. infestans over genes.

The FL, SC and NC were strongly influenced by dominant genes rather than treatment effects. These were indicated by GV, which was higher than EV, and GCV, which was higher than ECV. The H for FL, SC and NC showed that higher percentages of observed phenotypes were influenced by the dominant genes, which confirms that genetic effect was stronger than treatment effect for the three characters. Low genetic advance was observed for FL and NC, and moderate for SC. These are further proofs that genetic effect was stronger than effect of the fungus on the characters. The H in this study shows that NFS, CFW, NS and NLS were strongly influenced by the treatment effect, which is not consistent with Bhandari et al. (2017), who reported a stronger effect from dominant genes. The accessions, genotypes, and treatments used between the two studies can account for the observed differences. The H in FDM, TP and NLS that showed a stronger effect from treatment in the present study are not consistent with Pooja et al. (2022), who reported the strongest influence to be dominant genes. The accessions, treatments, and environment used can account for the various differences. The strong effect of dominant genes on FL is in accordance with Pooja et al. (2022). The FW in this study was influenced by treatment, while that of Somraj et al. (2017) was influenced by genetic factors. Variations in results can be attributed to different treatments used in the two experiments.

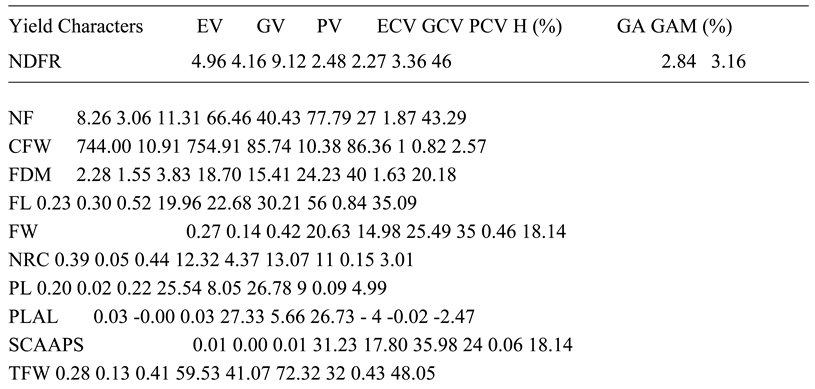

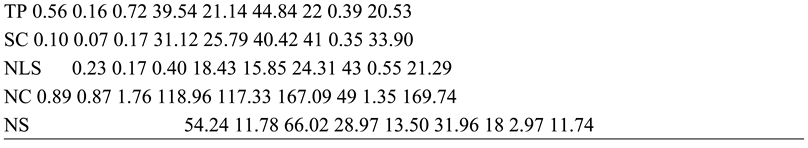

The NDFR, NFS, CFW, FDM, FW, NRC, PL, PLAL, SCAAPS, TFW, TP, SC, NLS, NC and NS were more influenced by A. niger than genetic factors for the observed characters. This is indicated by high PV backed up by high EV, while GV was least. The PCV was also high for the aforementioned characters and was supported by a high ECV, while the GCV was least. This further supports that the effect of A. niger on the characters was stronger than that of the dominant genes. The H for NDFR, NFS, CFW, FDM, FW, NRC, PL, PLAL, SCAAPS, TFW, TP, SC, NLS, NC and NS showed that the percentage of observed variances that were influenced by resistance genes were respectively lower than the effect of A. niger which confirms that the strongest effect for the observed variations was influenced by A. niger. Low GA for all the said characters further supports that the treatment effect was higher than genetic effect. The NDFR, CFW, NRC, PL and PLAL had low GAM.

The FW, SCAAPS and NS were moderate for GAM, while NF, FDM, TFW, TP, SC, NLS and NC had high GAM. Low and moderate GAM further prove that influence of A. niger on observed characters was greater than genetic effect. The FL was the only character that was strongly influenced by dominant genes. This was indicated by GV, which was higher than EV, and the GCV, which was also higher than ECV. The H for fruit length showed that most of the observed phenotype was influenced by dominant genes, compared to A. niger. This confirms that genetic response for FL was stronger than the fungus effect. The NLS in present study that were highly influenced by treatment effect is not in line with the report of Rasheed et al. (2023), which found that NLS was influenced by genetic factors. The TP and CFW that were influenced by treatment effect in this work are not in line with the findings of Meena et al. (2018), which reported these to be strongly influenced by dominant genes. The FL in this study was influenced by genetic factors, while Meena et al. (2018) reported that FL was controlled by treatment.

The NC in the present study was influenced by the environment, while Meena et al. (2018) observed this character to be controlled by dominant genes. The observed variations can be attributed to different treatments used for the two studies. The FDM and NF were controlled by treatment effect in this study, while Singh et al. (2015) reported these characters to be controlled by genes, suggesting that A. niger had a strong influence on the characters. The NS in this work was influenced by treatment, while Aralikatti et al. (2018) reported seed number to be controlled by dominant genes. The differences in results are attributed to various treatments used in the two studies.