1. Introduction

Maize (

Zea mays L.) is one of the most widely used grains in the world, particularly in Mesoamerica where it is widely distributed and one of the most diverse crops. The center of origin, domestication and diversity of maize is in Mexico, where there is a wide genetic diversity expressed through the different maize landraces as result of natural and sociocultural processes [

1,

2,

3,

4]. In the southern region of Mexico, Orozco-Ramírez et al. [

5] considered the Chiapas state as one of the areas with the highest maize diversity, with 18 different races. The most commonly cultivated among them are Oloton, Olotillo, Tuxpeño, Zapalote chico, Zapalote grande and Comiteco. The management, cultivation and uses that have been given to these races by local farmers through time have allowed the development of a wide diversity of maize landraces which can be distinguished by different characteristics such as grain color, ear size and cultivation cycle [

6,

7].

Despite the importance of the diversity of maize landraces present in Chiapas state, very few studies have focused on the genetic diversity of maize landraces throughout the entire region [

8]. Instead, the Frailesca region of Chiapas, which covers six municipalities (Villaflores, Villa Corzo, El Parral, Angel Albino Corzo, La Concordia and Montecristo de Guerrero), have received all the attention. These studies have covered various aspects related to maize landraces, such as ethnobotanical studies [

9], morphological diversity [

7,

10,

11], historical or cultural process [

3], and genetic diversity [

4,

12]. The results of these works offer a general overview of the diversity present in the maize landraces cultivated in the Frailesca region of Chiapas and highlighting the importance of further evaluating the genetic diversity present in maize landraces from the other regions of Chiapas.

One region where local farmers use and preserve a wide diversity of maize landraces is the Zoque region of Chiapas. However, until now the genetic diversity of these maize landraces has not been studied. In this regard, a series of genetic markers have been developed to analyze and evaluate the genetic diversity of plants [

13]. Among different molecular markers used to study genetic diversity in maize the inter simple sequence repeats (ISSR) have been widely used [

12,

14,

15,

16]. The ISSR markers are dominant, allowing detection of polymorphism without previous knowledge of DNA sequences. They are also rapid, simple and cheap for assessing diversity and genetic structure among crops plants [

17,

18]. In this study, ISSR markers were used for the first time to analyze the diversity and genetic structure of maize landraces cultivated in the Zoque Region of Chiapas, Mexico.

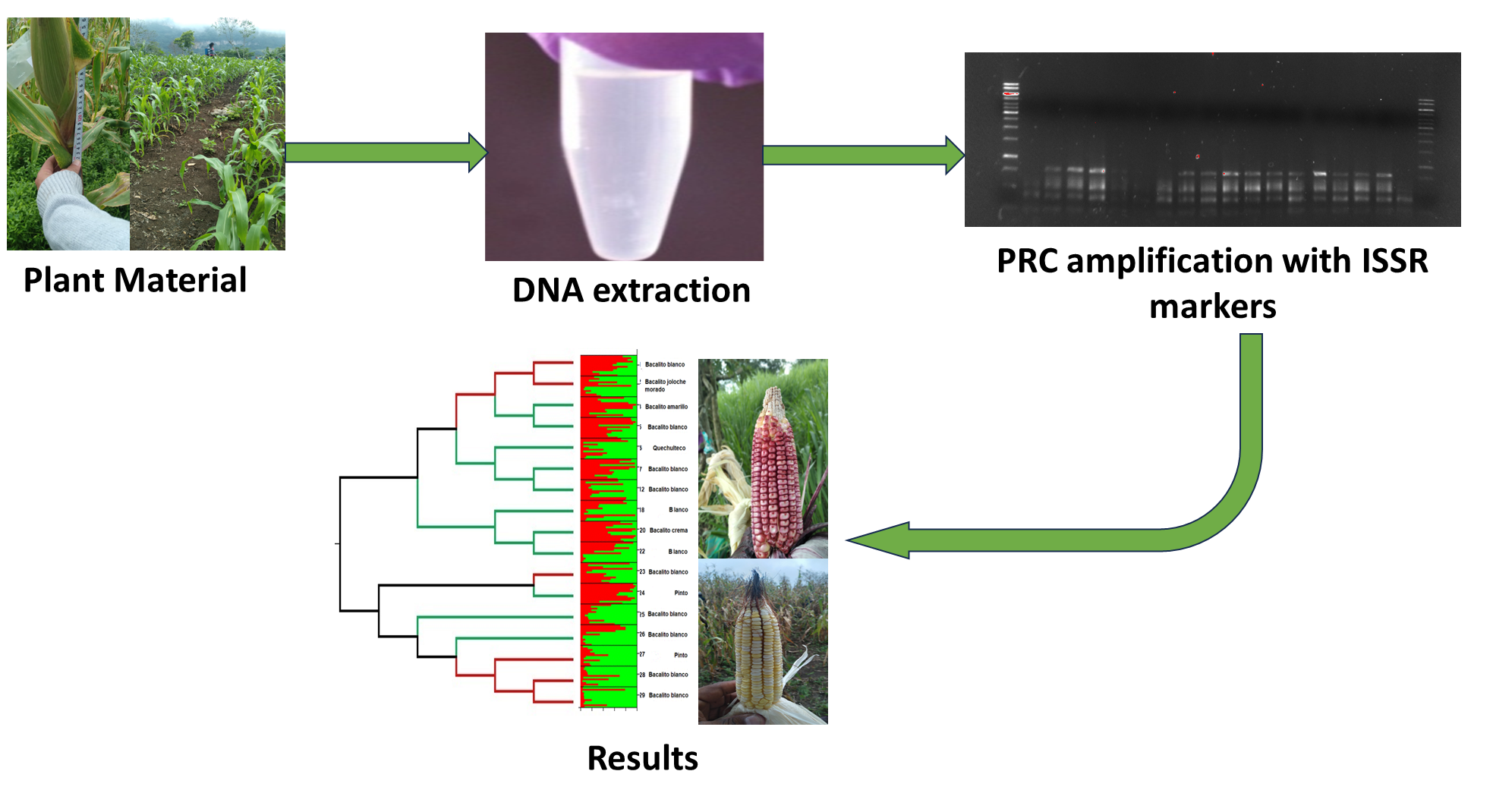

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Maize Collection

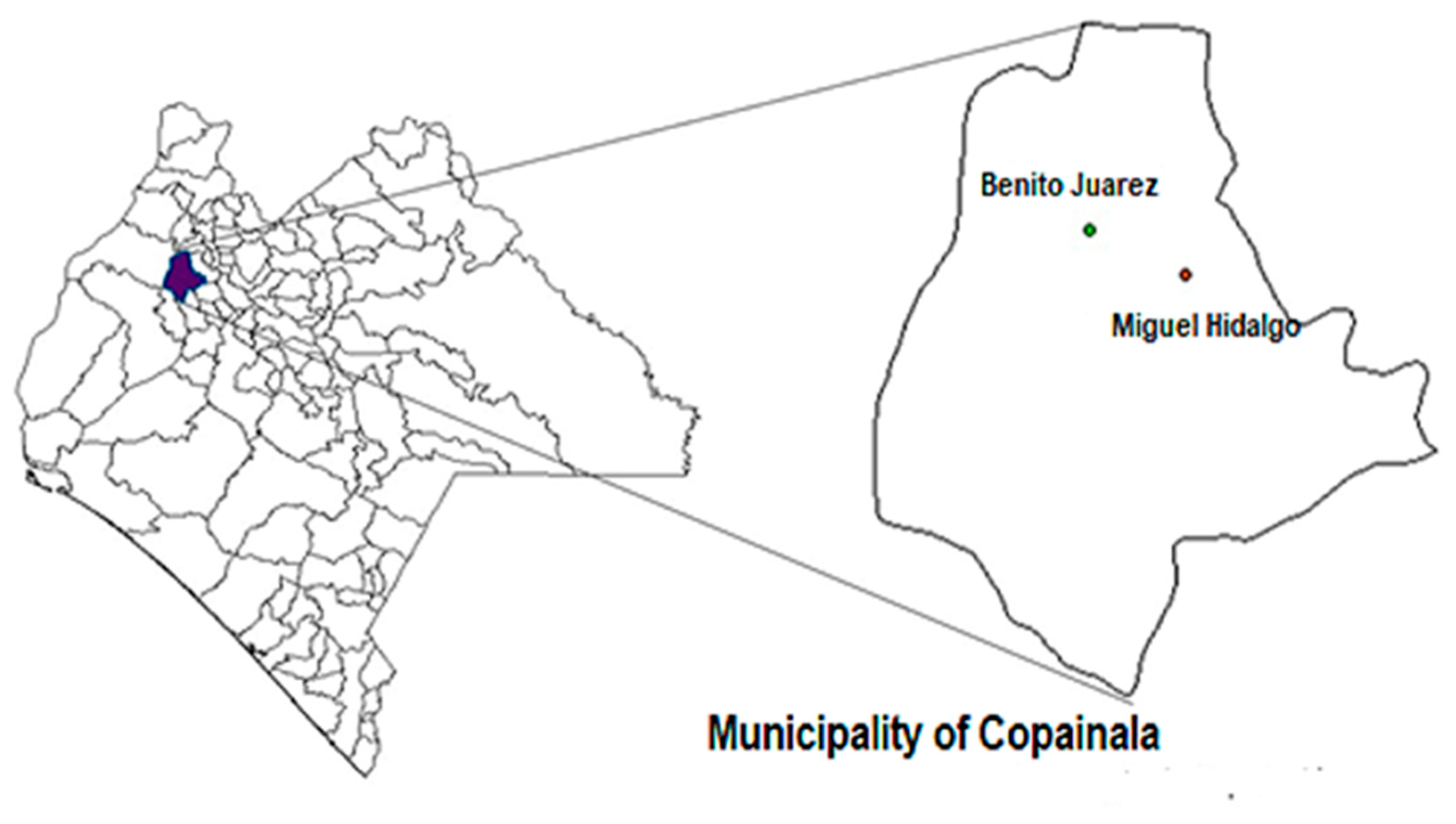

A total of 17 maize landraces were collected directly from the farmers’ fields (in their traditional farming systems called “Milpa”) in two communities: Benito Juárez and Miguel Hidalgo in the municipality of Copainala from the Zoque region located in the north of the state of Chiapas, Mexico (

Figure 1).

The maize landraces were identified according to a collection number, local name and collection site. Seven maize landraces from Benito Juárez and 10 from Miguel Hidalgo were collected from the farmers´ fields (

Table 1).

2.2. Extraction and Amplification of DNA

The genomic DNA extraction was carried out in the Molecular Genetics Laboratory of Tecnológico Nacional of México, Conkal campus. Twenty seeds from each maize landrace were germinated using the between-paper method described by Rao et al. [

19]. Genomic DNA was extracted from young leaves free of pests and diseases and without mechanical damage from a total of 12 individual plants for each maize landrace using DNeasy® Plant Mini Kit (QIAGEN) following the supplier’s indications. The quality of DNA was verified by electrophoresis in 1% agarose gel stained with 1 μl of Uview 6x loading dye (BioRad) in 1x TBE buffer solution. For PCR amplification for a total of 15 ISSR primers tested, seven were selected that yielded good amplification and high polymorphism levels for maize [

12,

20] (

Table 2). The PCR amplifications were carried out in a total volume of 20 µL containing 10µL of iTaq Universal SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad), 2 µL of ISSR primer, 1 µL of template DNA (50 ng/reaction), and 7 µL of ultra-pure water. DNA amplification was performed in a thermal cycler C1000 Touch (BioRad) programed for 4 min at 94 °C for initial denaturing, followed by 35 cycles of 2 min at 94 °C, 1.5 min annealing at 52 or 54 °C depending on the primer used, 1 min at 72 °C and a final extension of 7 min at 72 °C. The amplification products were separated by electrophoresis in 1% agarose gel stained with 1 μl of Uview 6x loading dye (BioRad) with 1x TBE buffer solution at a constant 110 V for 45 min. A 1 kb molecular marker standard was included in each gel, and the bands were visualized using the Gel Doc EZ Imager program (BioRad).

2.3. Data Analysis

Each ISSR band was considered as an independent locus, and polymorphic bands were scored as absent (0) or present (1) for all samples. Only clear and reproducible bands were used for the analysis.

2.4. Genetic Structure

The genetic structure was analysed based on two methods. In the first method, an individual assignment test was performed using Bayesian clustering approaches as implemented in the program STRUCTURE 2.3.4 [

21]. We used the admixture model with uncorrelated allele frequencies with a burn-in period of 100,000 and a run length of 1,000,000 Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) steps. Ten independent simulations were run for each value of K ranging from K = 1 to K = 5. The optimal value of K was determined according to Evanno et al. [

22] using the program StructureSelector [

23]. Finally, the ancestry graphs for the optimum K value were generated using STRUCTURE. The second method used to analyse the genetic structure was an analysis of molecular variance (AMOVA) considering three levels: total (including all maize landraces), between maize landraces, and within maize landraces, using the GenAlEx 6.5 software.

2.5. Genetic Relationships

To analyse the genetic relationships among maize landraces from the Zoque region, Chiapas, the genetic data were analysed with an UPGMA dendrogram using the Euclidian distance. The tree topology was evaluated with 1000 bootstrap replicates with the PAST program [

24]. Finally, to support the results obtained with the UPGMA, a principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) was carried out using the covariance not standardized method with the GenAlex program [

25].

2.6. Genetic Diversity

The genetic diversity was evaluated on two levels: maize landraces and observed groups through allelic richness indices: percentage of polymorphic loci (% P), observed number of alleles (na), effective number of alleles (ne), and the better estimators of genetic diversity for analysing dominant markers data, the Shannon–Weaver diversity index (I) and expected heterozygosity with a Bayesian approach (HBay). The allelic richness indices and Shannon–Weaver diversity index, were obtained using the POPGENE v. 1.31 program [

26]. The expected heterozygosity (HBay) was calculated using AFLPSURV v. 1.0 [

27].

3. Results

3.1. Genetic Structure

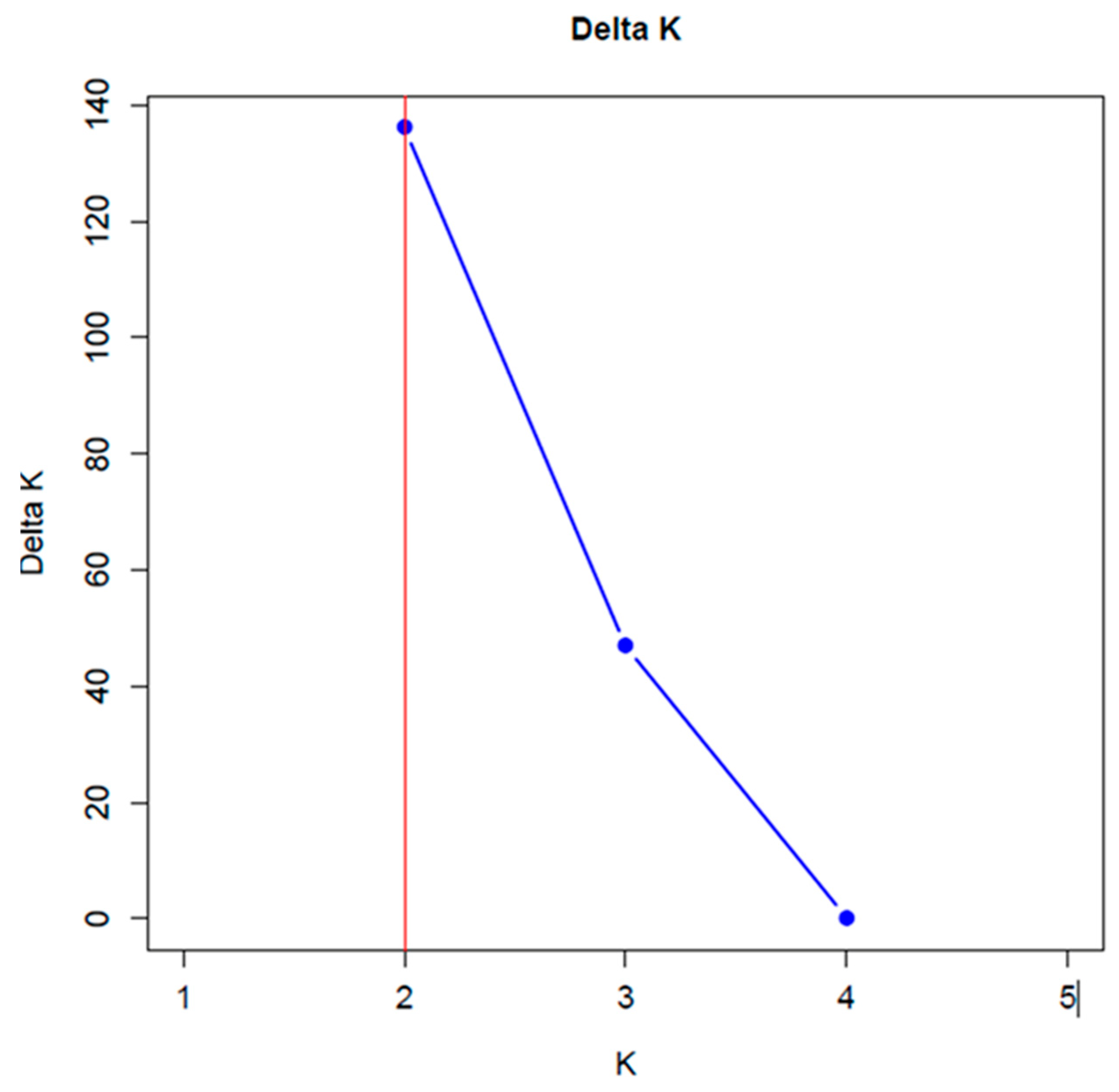

The Evanno method results [

22] showed a maximum point of inflection at K=2 for all of accessions analyzed, indicating the existence of two genetically distinct groups (

Figure 2).

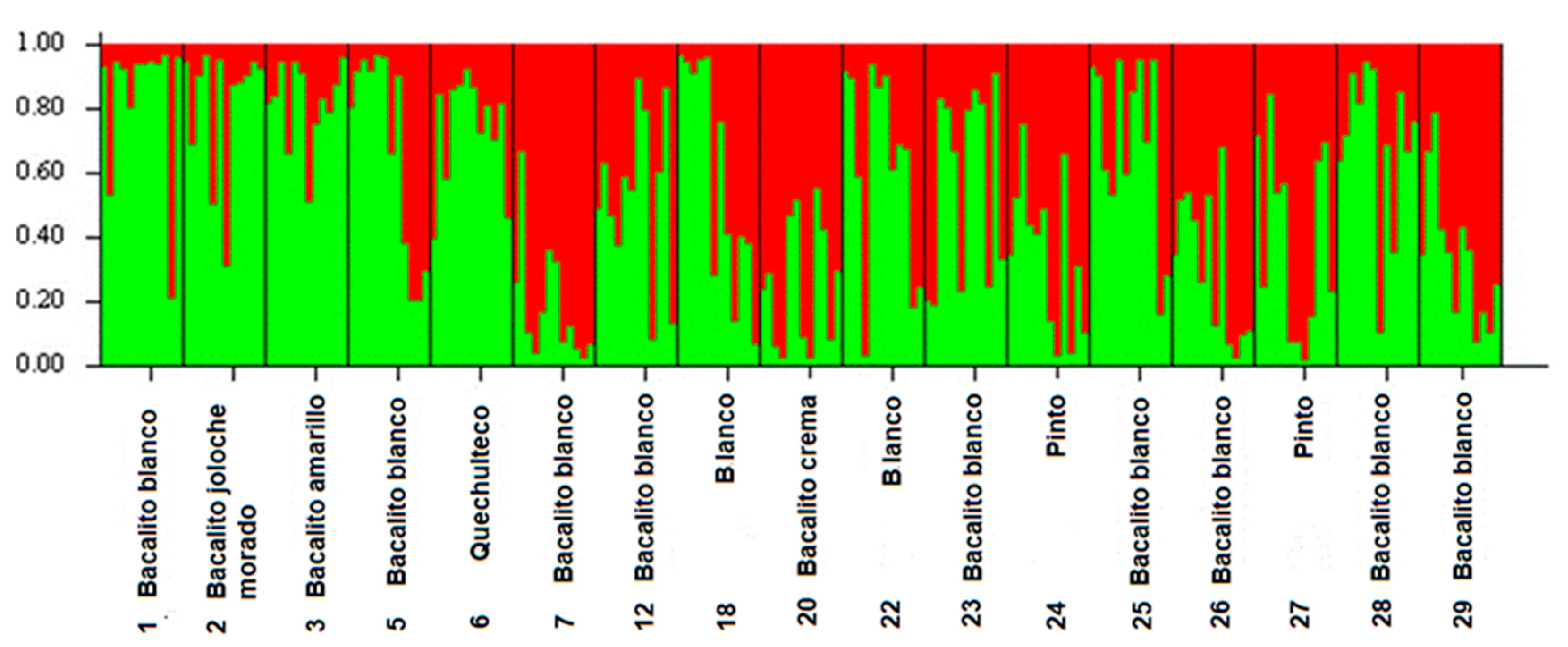

The bar graph (

Figure 3), shows the ancestry coefficients of the 204 samples analyzed in the 17 maize landraces studied. Two genetically differentiated groups can be observed. Group I (in green) was the most diverse and included 11 maize landraces, eight of which are white seed (six of which are part of the Olotillo race named locally Bacalito 1, 5, 12, 23, 25, 28 and two belong to the Tuxpeño race locally called Blanco 18 and 22), one purple-colored maize landrace (which is part of the Olotillo race, Bacalito morado, landrace 2), one yellow seed landrace (belonging to the Olotillo race, Bacalito amarillo, landrace 3) and the quechulteco landrace (belonging to the Tehua race landrace 6). Of these 11 accessions, six were collected in the Benito Juárez locality (landraces 1, 2, 3, 5, 6 and 12) and five accessions were collected in the Miguel Hidalgo locality (landraces 18, 22, 23, 25 and 28). Group II (in red) grouped six maize landraces, of which three corresponded to white seed maize landraces belonging to the Olotillo race (Bacalito blanco, landraces 7, 26 and 29), one Cream seed landrace from the Olotillo race (named Bacalito crema, landrace 20) and two maize landraces of colored seeds belonging to the Tuxpeño race (named Pinto 24 and 27). This group was less diverse and included five accessions collected in the Miguel Hidalgo area and one in the Benito Juárez area.

Molecular variance analysis (AMOVA) at the maize landraces level indicated that the greatest genetic variability is distributed within the maize landraces with 70% of the total variability, while only 30% of the observed variability was distributed between accessions. At the level of genetic groups, greater variability was observed within the formed groups (96%) compared to that observed between groups (4%) (

Table 3).

3.2. Genetic Relationships

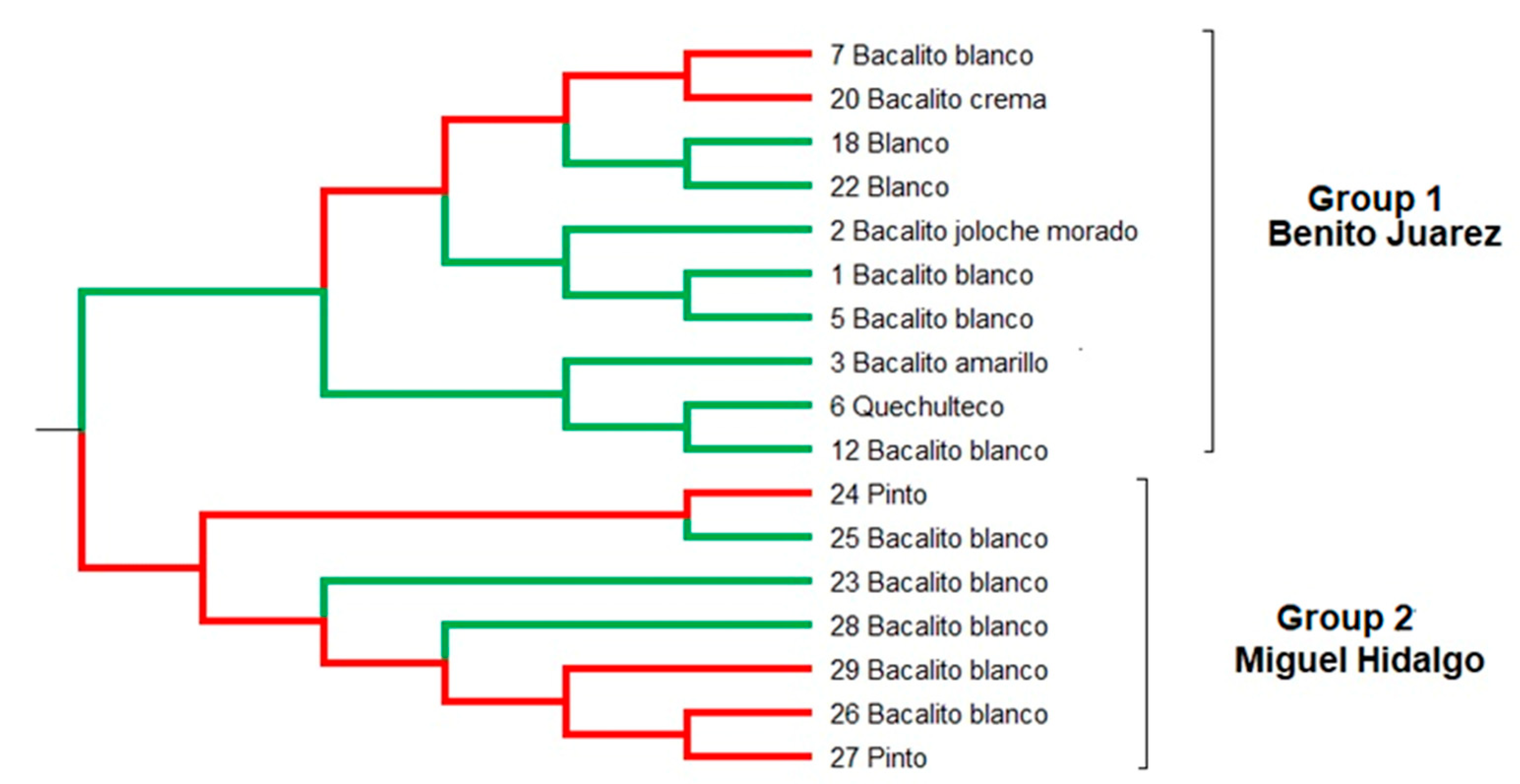

The results of the UPGMA analysis (

Figure 4) grouped the 17 maize landraces into two main groups, showing a general grouping based on the geographical origin of the maize landraces. The first group is made up of 10 landraces of which seven belong to the Olotillo race (landraces 7 Bacalito blanco, 20 Bacalito crema, 12 Bacalito blanco, 2 Bacalito morado, 1 Bacalito blanco, 5 Bacalito blanco, 3 Bacalito amarillo), one landrace belonging to the Tehua race (landrace 6 quechulteco) and two maize landraces belonging to the Tuxpeño race (landraces 18 blanco and 22 blanco). These landraces were collected in the Benito Juárez area and only the landraces 18, 20 and 22 were collected in the Miguel Hidalgo area. The second group was composed of seven maize landraces, five of which have white seeds and belong to the Olotillo race (landraces 25 Bacalito blanco, 23 Bacalito blanco, 28 Bacalito blanco, 29 bacalito blanco and 26 bacalito) and the two remaining landraces are from maize colorful seed and belong to the Tuxpeño race (Maize landraces 24 and 27 named Pinto). All the accessions that belong to this group were collected in the Miguel Hidalgo area. With some exceptions, the topology observed in UPGMA (

Figure 4) is consistent with the groups observed in the structure analysis (

Figure 3). The exceptions are the inclusion of the maize landraces 7 and 20 in group 1 of the UPGMA, whereas in the Structure analysis, these two accessions were grouped together in group 2. By contrast, maize landraces 23, 25 and 28 were included in group 2 of the UPGMA, but in the Structure analysis these three accessions were in group 1.

3.3. Genetic Diversity

The seven ISSR primers generated a total of 48 loci, 32 of which were polymorphic.

Table 4, shows the indices of allelic richness and genetic diversity of the 17 maize landraces collected in the two communities of the Zoque region of Chiapas, with a general average of 31 polymorphic loci corresponding to 66% of polymorphic loci. The maize landrace 28 named Bacalito blanco presented the highest number of polymorphic loci, while 6 Quechulteco and 12 Bacalito blanco maize landraces presented the lowest number of polymorphic loci with 50% in both landraces.

The average number of alleles observed in the whole sample was 1.86±0.46, with the maize landrace 28 named Bacalito blanco, presenting the highest average number of observed alleles with 1.83±0.37, while landraces 6 Quechulteco and 12 Bacalito blanco, presented the lowest number of observed alleles. The average number of effective alleles was 1.43±0.38, with maize landrace 22 named Bacalito blanco which presented the highest number of effective alleles with 1.56±0.38, while the landraces 1 Bacalito blanco and 24 Pinto, were those that obtained the lowest number of effective alleles with 1.30 in both landraces. With respect to the index of genetic diversity evaluated by the expected heterozygosity under a Bayesian approach (Hbay) an overall average of 0.29±0.01 was found. The maize landrace 22 named Bacalito blanco presented the greatest genetic diversity with 0.36±0.02 and the maize landrace 12 named Bacalito blanco presented the least genetic diversity with 0.24±0.02. When genetic diversity was evaluated using the Shannon index (I), the average genetic diversity was 0.36 and landraces 22 and 28, both named Bacalito blanco, were the ones with the highest genetic diversity with 0.45 (

Table 4).

4. Discussion

4.1. Genetic Structure

The results based on the individual assignment test and the UPGMA cluster analysis show that the genetic structure of the maize landraces studied is integrated in two genetic groups consistent with their geographical origin. Similar results have been reported in other studies where a clustering pattern was observed based on geographical origin [

12,

28,

29] and not due to genotype characteristics, environmental adaptation, color or grain type of the maize landraces evaluated as reported by Adu et al. [

30]. The association between genetic groups and their geographical origin observed in this study may be due to the fact that farmers from the communities of the Zoque region of Chiapas, Mexico, preserve their maize landraces because of characteristics related to the handling and consumption of the maize such as greater ease for kernel removal, kernels of greater weight and size, and shorter cooking time.

The AMOVA results show that the distribution of genetic diversity was higher within maize landraces and within observed genetic groups. This finding is consistent with the results of Dube et al. [

31] and Da Silva et al. [

32] that observed that the partition of genetic diversity between and within populations was significantly greater within populations when studying the diversity and genetic structure of maize races. This result has been also found in general in allogamous plants where there is a high genetic variation within populations and low among them [

32,

33]. In addition, in allogamous species, molecular markers typically reveal high heterozygosis within populations, which results in low differentiation between them [

32].

4.2. Genetic Relationships

The UPGMA analysis of genetic relationships are in agreement with the formation of two genetic groups, but presented some differences with the individuals assignment analysis (

Figure 3 and

Figure 4). Similar results were reported by Santos et al. [

12] for maize landraces from southeastern Mexico. In the present work, five exceptions were found between the UPGMA and the Structure analysis (7, 20, 23, 25 and 28). In case of maize landrace 7 named Bacalito blanco, it was collected in the Benito Juárez area, however in the structure analysis, it was grouped with the maize landraces collected in the Miguel Hidalgo area. For landrace 20, opposite outcome occurred, it was collected in the Miguel Hidalgo area, but in the Structure analysis it was grouped with the accessions collected in Benito Juárez area. Similarly, the landraces 23, 25 and 28 were collected in Miguel Hidalgo area, however in the Structure analysis, these accessions were grouped with the maize landraces collected in Benito Juárez. Cömertpay et al. [

34] mention that the reasons for the non-relatedness of landraces from the same region could be due to the unconscious selection of favorable alleles by farmers who select landraces with better adaptation to local agroclimatic conditions, the exchange of seeds by farmers from distant regions, and the migration of landraces among regions followed by mixing and introgression with preexisting germplasm.

In this study the five maize landraces which were not grouped with the landraces of the same collection area are maize landraces belonging to the Olotillo race and share the following characteristics: they are short cycle maize landraces, present greater ease for kernel removal, higher grain yield, have shorter cooking times, yield higher dough quantities, and produce better tasting tortillas. These characteristics make farmers and housewives prefer them for sowing and consumption. A possible explanation for the lack of grouping between these five maize landraces (7, 20, 23, 35 and 28) and the landraces belonging to the same area could be due to the exchange of seeds by farmers between the two studied localities with the aim of obtaining the maize landraces with the best characteristics for sowing and consumption.

4.3. Genetic Diversity

The seven ISSR primers used were successful in this study, presenting polymorphism in the maize landraces from the Zoque area of northern Chiapas, with a percentage of general polymorphic loci of 66% and a range between landraces of 50 to 83%. Similar results have been reported in other studies of genetic diversity and structure of maize landraces using dominant ISSR and RAPD markers [

12,

16,

35,

36]. Moreover, four primers used in this study (GACA4, AG8C, AG8T and CA8T) have shown their usefulness to evaluate genetic polymorphism in native maize populations reaching polymorphism levels in a range of 85 to 100% [

12,

14]. The average levels of genetic diversity with both estimators (Hbay = 0.29 and I = 0.36) was moderate. These values of genetic diversity were below the genetic diversity of maize landraces reported by other authors [

4,

28,

29,

31,

36,

37], but similar to those reported by Adu et al. [

30] on inbred lines of tropical maize, Da Silva et al. [

32] on popcorn accessions from the Brazilian germplasm bank, Soliman et al. [

16] in accessions of maize from Genebank of the Institute of Plant Genetics and Crop Plant Research (IPK), Germany, and Santos et al. [

12] in maize landraces from Mexico. The variation between our results and the findings reported by the authors mentioned above could be attributed to the differences in the markers used, the area explored in each study, the number of landraces evaluated and the number of markers involved in the studies.

In this work we also found that maize landraces 22 and 28, called Bacalito blanco of the Olotillo race, had the greatest genetic diversity. This may occur because these maize landraces are the most cultivated by local farmers, and therefore more adapted to the local conditions of the studied region. In general, the local varieties belonging to the Olotillo race were the most genetically diverse. This result is consistent with Barrera et al. [

38] who observed that the populations of maize belonging to the Olotillo race presented high levels of diversity. In general, the levels of diversity observed in this study may be largely due to the fact that maize is a species of open pollination. In addition, maize landraces were sampled in two regions with variable environmental and geographical conditions, which could also influence the level of diversity observed.

5. Conclusions

The results of this study contribute to gain insight into the structure and genetic diversity of maize landraces in the Zoque region from Chiapas, Mexico. The results showed that the genetic diversity of the local varieties in the Zoque region of Chiapas are structured in two genetic groups based on their geographic origin. The greatest genetic diversity is distributed within local varieties and within observed genetic groups. Five maize landraces (7, 20, 23, 35 and 28) were not grouped according to their geographical origin. The level of total genetic diversity was moderate. The maize landraces 22 and 28, called Bacalitos, which are part of the Olotillo race, showed the greatest genetic diversity. Our results indicate that the landraces collected in the Zoque region from Chiapas, Mexico constitute a valuable genetic resource that can be used for genetic improvement and conservation programs both ex situ and in situ.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.L.M., E.R.S., G.R.P. and E.C.H.; methodology, E.C.H. and R.H.A.N.; formal analysis, E.C.H., R.H.A.N. and M.G.C.; investigation, E.C.H.; writing—original draft preparation, R.H.A.N. and E.C.H.; writing—review and editing, R.H.A.N., L.L.M., E.R.S., G.R.P., M.G.C.; visualization, R.H.A.N. and E.C.H.; supervision, L.L.M., E.R.S. and G.R.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the

corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the farmers who donated genetic materials (maize landraces) and Dra. Emily Zamudio Moreno for technical support. The first author thanks the Consejo Nacional de Humanidades, Ciencia y Tecnología-Mexico for a postgraduate scholarship (scholarship number: 780593).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Matsuoka, Y.; Vigouroux, Y.; Goodman, M.M.; Sanchez, G.J.; Buckler, E.; Doebley, J. A. Single domes tication for maize shown by multilocus microsat ellite genotyping. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2002, 99, 6080–6084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muñoz, O.A.; Miranda, C.S.; Cuevas, S.J.A.; Santacruz, V.A. .; Sánchez, D.S. Resistencias, prehistoria, historia y diferencias de teocintle a maíz. Impresos América, Texcoco, México, 2009; 7–32. [Google Scholar]

- Caballero, M.A.; Cordova, L.; Lopez, A.J. Validación empírica de la teoría multicéntrica del origen y diversidad del maíz en México. Rev. fitotec. mex. 2019, 42, 357–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, B.; Rocandio, M.; Santacruz, A.; Córdova, L. , Coutiño, B.; López, H. Genetic diversity characterization of maize populations using molecular markers. Ital. J. Agron. 2023, 18. [Google Scholar]

- Orozco, Q.; Perales, H.; Hijmans, R.J. Geographical distribution and diversity of maize (Zea mays L. subsp. mays) races in Mexico. Genet. Resour. Crop. Evol. 2017, 64, 855–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salinas, Y.; Cruz, F.J.; Díaz, S.A.; Castillo, F. Granos de maíces pigmentados de Chiapas, características físicas, contenido de antocianinas y valor nutracéutico. Rev. Fitotec. Mex. 2012, 35, 33–41. [Google Scholar]

- Coutiño, B.; Vidal, V.A.; Cruz, C.; Gómez, M. Características eloteras y de grano de variedades nativas de maíz de Chiapas. REMEXCA. 2015, 6, 1119–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perales, H; Golicher, D. Mapping the Diversity of Maize Races in Mexico. PLoS one. 2014, 9, 14657. [Google Scholar]

- Guevara-Hernández, F.; Hernández, M.A.; Bastarrechea, J.L.; Fonseca, M.A.; Delgado, F.; Ocaña, M.; Acosta, R. Riqueza de maíces locales (Zea mays L.) en la región Frailesca, Chiapas, México: un estudio etnobotánico. Rev. Fac. Agron. 2020, 37, 223–243. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández-Ramos, M.A.; Guevara, F.; Basterrechea, J.L.; Coutiño, B.; O-Arias, M.; Pinto, R. Diversidad y conservación de maíces locales de la Frailesca, Chiapas, México. Rev. Fitotec. Mex. 2020, 43, 471–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, B.; Rocandio, M.; Santacruz, A.; Córdova, L.; Coutiño, B.; López, H. Morphological and agronomic diversity of seven corn races from the state of Chiapas. REMEXCA. 2022, 13, 687–699. [Google Scholar]

- Santos, L.P.; Andueza-Noh, R. H; Ruíz, E.; Latournerie, L.; Garruña, R.; Mijangos, J. O; Martínez, J. Characterization of the genetic structure and diversity of maize (Zea mays L.) landrace populations from Mexico. Maydica 2017, 62. [Google Scholar]

- Li, S.; Gan, X.; Han, H. Low within-population genetic diversity and high genetic differentiation among populations of the endangered plant Tetracentron sinense Oliver revealed by inter-simple sequence repeat analysis. Ann. For. Sci. 2018, 75, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández, M.A.; Rodríguez, L.A.; Guevara, F.; Rosales, M.Á.; Pinto, R.; Ortiz, R. Caracterización molecular de maíces locales de la Reserva de la Biosfera La Sepultura, México. Agron. Mesoam. 2017, 28, 69–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcón, F.; Martínez, E.J.; Rodríguez, G.R.; Zilli, A.L.; Brugnoli, E. A.; Acuña, C.A. Genetic distance and the relationship with heterosis and reproductive behavior in tetraploid bahiagrass hybrids. Mol. Breeding. 2019, 39, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soliman, R.S.; El, H.H.; Börner, A.; Badr, A. Genetic diversity of a global collection of maize genetic resources in relation to their subspecies assignments, geographic origin, and drought tolerance. Breed. sci. 2021, 71, 313–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, V.P; Ruas, P.M; Ruas, C.F. , Ferreira, J.M.; Moreira, R.M.P. Assessment of genetic diversity in maize (Zea mays L.) landraces using inter simple sequence repeat (ISSR) markers. Crop. Breed. App.l Biotechnol. 2002, 2, 557–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenka, D.; Tripathy, S.K.; Kumar, R.; Behera, M.; Ranjan, R. Assessment of genetic diversity in quality protein maize (QPM) inbreds using ISSR markers. J. Environ. Biol. 2015, 36, 985–992. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rao, N.K.; Hanson, J.; Dulloo, M.E.; Ghosh, K.; Novell, D. Larinde, M. Manual of seed handling in genebanks. Handbooks for Genebanks. Bioversity International, Rome 2006, 8. [Google Scholar]

- Idris, A.E.; Hamza, N.B.; Yagoub, S.O.; Ibrahim, A.I.A.; Hamin, H.K.A. Maize (Zea mays L.) genotypes diversity study by utilization of Inter Simple Sequence Repeat (ISSR) markers. Aust. J. Basic. Appl. Sci. 2012, 6, 42–47. [Google Scholar]

- Pritchard, J.K.; Stephens, M.; Donnelly, P. Inference of population structure using multilocus genotype data. Genetics. 2000, 155, 945–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evanno, G.; Regnaut, S.; Goudet, J. Detecting the number of clusters of individuals using the software STRUCTURE: A simulation study. Mol. Ecol. 2005, 1, 2611–2620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.L.; and Liu, J.X. StructureSelector: A web-based software to select and visualize the optimal number of clusters using multiple methods. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 2018, 18, 176–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hammer, Ø.; Harper, D. A.; Ryan, P. D. PAST: Paleontological statistics software package for education and data analysis. Palaeonton. Electron. 2001, 4, 4–9. [Google Scholar]

- Peakall, R.; Smouse, R.P.P. GenAlEx 6.5: genetic analysis in Excel. Population genetic software for teaching and research—an update. Bioinformatics. 2012, 28, 2537–2539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeh, F.C.; Boyle, T.J. POPGENE v. 1.31. Microsoft Windows-Based Freeware for Population Analysis; University of Alberta and Centre for International Forestry Research. University of Alberta: Edmonton. AB, Canada. 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Vekemans, X. AFLP-SURV version 1.0: Distributed by the autor. Laboratoire de genetique et Ecologie Vegetale. Universite Libre de Bruxelles, Belgium. 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Patel, R.; Memon, J.; Kumar, S.; Patel, D.A.; Sakure, A.A.; Patel, M.B.; Das, A.; Karjagi, C.G.; Patel, S.; Patel, U.; Roychowdhury, R. Genetic Diversity and Population Structure of Maize (Zea mays L.) Inbred Lines in Association with Phenotypic and Grain Qualitative Traits Using SSR Genotyping. Plants. 2024, 13, 823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aci, M.M.; Lupini, A.; Mauceri, A.; Morsli, A.; Khelifi, L.; Sunseri, F. Genetic variation and structure of maize populations from Saoura and Gourara oasis in Algerian Sahara. B.M.C. Genet. 2018, 1, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adu, G.B.; Badu-Apraku, B.; Akromah, R.; Garcia-Oliveira, A.L.; Awuku, F.J; Gedil, M. Genetic diversity and population structure of early-maturing tropical maize inbred lines using SNP markers. PloS One. 2019, 14, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Dube, S.P.; Sibiya, J.; Kutu, F. ; Genetic diversity and population structure of maize inbred lines using phenotypic traits and single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) markers. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 17851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Silva, T.A.; T. ; Cantagalli, L.B.; Saavedra, J.; Lopes, A.D.; Mangolin, C.A.; Da silva, M.F.P.; Scapim, C.A. Population structure and genetic diversity of Brazilian popcorn germplasm inferred by microsatellite markers. Electron. J. Biotech. 2015, 18, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, R.; Zong, Z.; Yu, W.; Ying, W. Genetic variation and genetic structure within metapopulations of two closely related selfing and outcrossing Zingiber species (Zingiberaceae). Aoplants 2021, 13, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Cömertpay, G.; Baloch, F.S.; Kilian, B. Diversity Assessment of Turkish Maize Landraces Based on Fluorescent Labelled SSR Markers. Plant. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2012, 30, 261–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molin, D.; Coelho, C.J.; Máximo, D.S.; Ferreira, F.S.; Gardingo, J.R.; Matiello, R.R. Genetic diversity in the germplasm of tropical maize landraces determined using molecular markers. Genet. Mol. Res. 2013, 12, 99–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chňapek, M.; Balážová, Ž.; Špaleková, A. Genetic diversity of maize resources revealed by different molecular markers. Genet. Resour. Crop. Evol. 2024, 71, 4685–4703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romay, M.C.; Butrón, A.; Ordás, A.; Revilla, P.; Ordás, B. Effect of Recurrent Selection on the Genetic Structure of Two Broad-Based Spanish Maize Populations. Crop Science. 2012, 52, 1493–1502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrera, L. A.; Legaria, Juan P. ; Ortega, R. Diversidad genética en poblaciones de razas mexicanas de maíz. Rev. fitotec. mex. 2020, 43, 121–125. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).