Submitted:

06 January 2025

Posted:

08 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

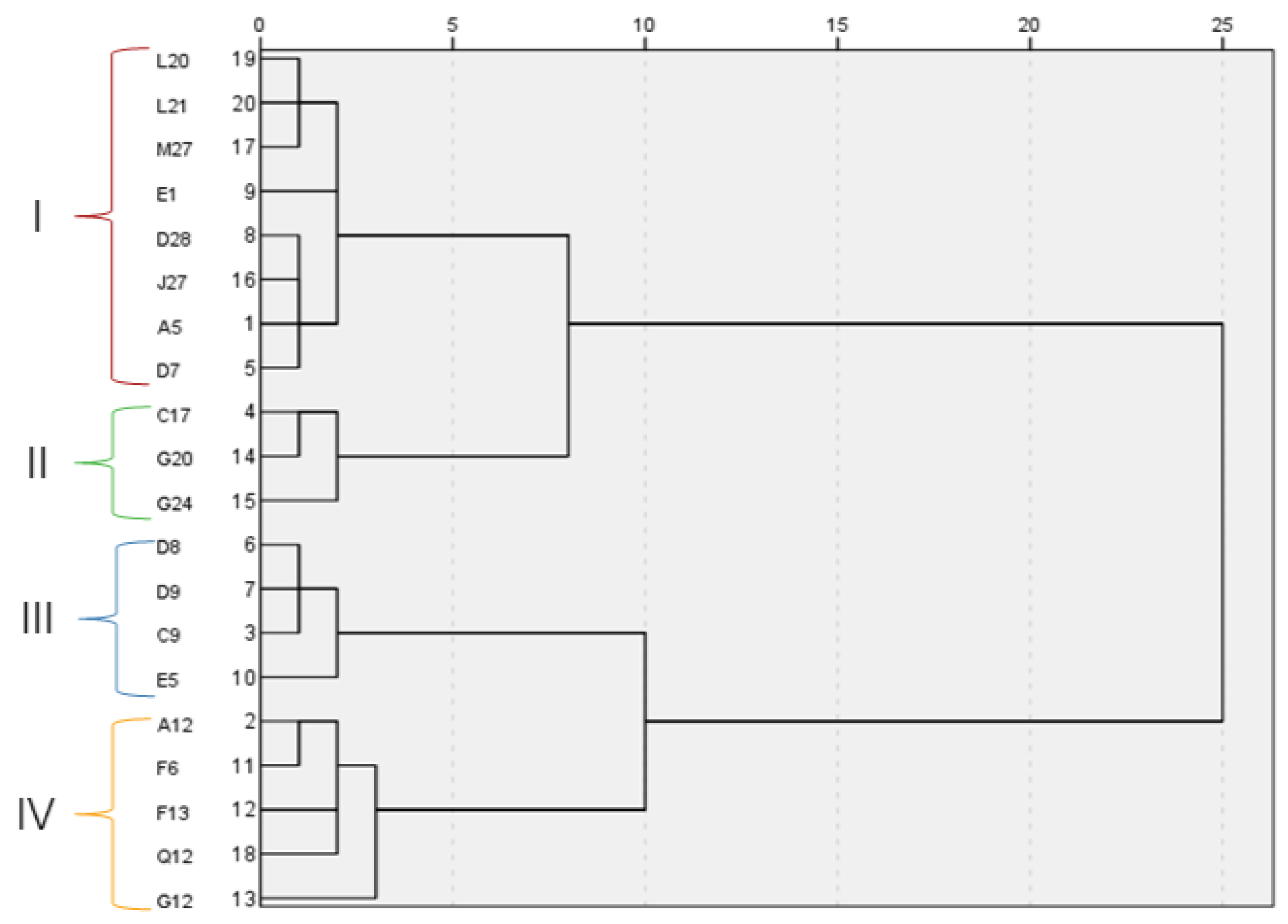

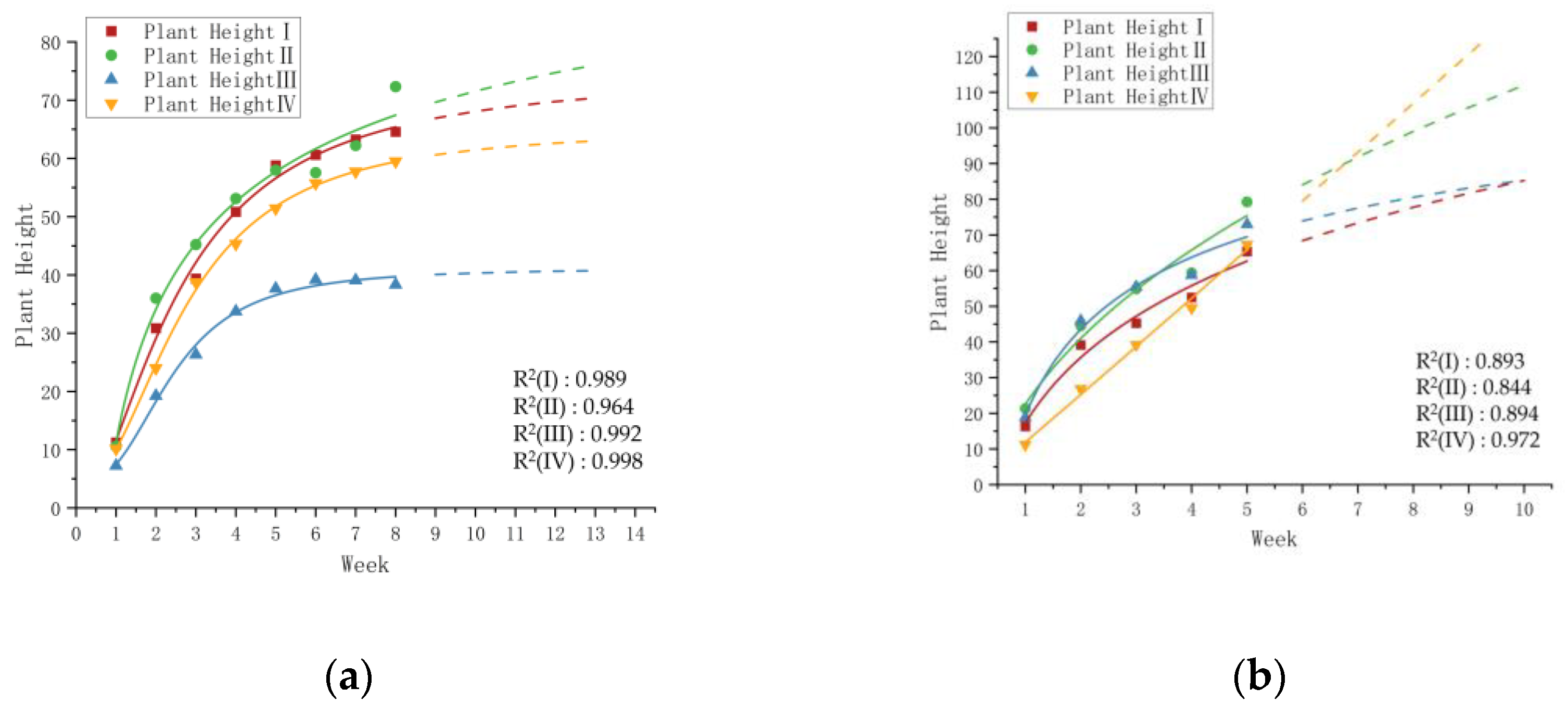

In alfalfa breeding, traditional recurrent selection methods often rely on extensive field trials and empirical judg-ment, which are inefficient and lack accuracy. This experiment attempts to introduce a logistic regression model combined with the analysis of alfalfa agronomic traits to select hybrid parents for alfalfa materials, thereby improving the efficiency and accuracy of recurrent selection. Using 20 alfalfa materials as subjects, the experiment involved agronomic trait analysis, variation analysis, cluster analysis, and the construction of a logistic model to evaluate and screen the alfalfa materials. The results showed that the 20 alfalfa materials were clustered into four clusters with similar performances. Based on the growth performance at the initial flowering stage, the best-performing alfalfa in autumn and spring was in cluster II. Around the 3.5th week of spring, cluster III > cluster II, showing the fastest growth. According to the predictions from the logistic fitting curve, the growth performance of cluster IV alfalfa surpassed that of cluster II around the 7th week, which was inconsistent with the growth performance before the initial flowering stage, revealing the genetic potential of cluster IV alfalfa in plant height traits. The results indicate that the Logistic model can improve the selection accuracy in alfalfa breeding, avoid the waste of genetic resources, and provide important reference value for the selection of parents in recurrent selection of alfalfa.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Materials

2.2. Experimental Site Overview

2.3. Agronomic Traits and Methods

2.4. Calculation of Alfalfa Variance Analysis

2.5. Fitting and Prediction of Alfalfa Growth Dynamic Curve

2.6. Data Statistics and Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Analysis of Agronomic Traits During the Initial Flowering Stage of Alfalfa

3.2. Analysis of Variability in Agronomic Traits of Alfalfa Material

| Trait | Year | Max | Min | variation range | Average | Standard deviation | Coefficient ofvariation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plant height (cm) | 2022 | 79.67 | 32.67 | 47.00 | 58.23 | 14.30 | 24.55% |

| 2023 | 90.47 | 21.13 | 69.34 | 66.84 | 16.49 | 24.67% | |

| Number of Branches | 2022 | 167 | 27 | 140 | 95.30 | 37.78 | 39.65% |

| 2023 | 313 | 35 | 278 | 164.30 | 71.19 | 43.33% | |

| leaf area(cm2) | 2022 | 10.71 | 3.26 | 7.45 | 5.77 | 2.10 | 36.35% |

| 2023 | 9.87 | 3.7 | 6.17 | 5.73 | 1.65 | 28.78% | |

| Multiple leaf rate (%) | 2022 | 0.91 | 0 | 0.91 | 0.21 | 0.30 | 144.44% |

| 2023 | 0.95 | 0 | 0.95 | 0.22 | 0.32 | 144.87% |

3.3. Clustering Analysis of Alfalfa Materials Based on the Recurrent Selection Method

3.4. Fitting and Predicting the Growth Dynamics Curve of Alfalfa Using a Logistic Model

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| S1 | The first self- fertilization generation |

| S2 | The second self- fertilization generation |

| BC1 | The first Backcross generation |

| BC2 | The second Backcross generation |

| F1 | The first filial generation |

References

- Shi, S.; Nan, L.; Smith, K.F. The Current Status, Problems, and Prospects of Alfalfa (Medicago sativa L.) Breeding in China. Agronomy 2017, 7, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tucak, M.; Horvat, D.; Čupić, T.; Krizmanić, G.; Ravlić, M. Assessment of Alfalfa Populations for Forage Productivity and Seed Yield Potential under a Multi-Year Field Trial. Agronomy 2023, 13, 349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horner, E.S.; Lundy, H.W.; Lutrick, M.C.; Chapman, W.H. Comparison of Three Methods of Recurrent Selection in Maize. Crop Sci. 1973, 43, 485–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Castro, A.P.; Breseghello, F.; Furtini, I.V.; Utumi, M.M.; Pereira, J.A.; Cao, T.-V.; Bartholomé, J. Population improvement via recurrent selection drives genetic gain in upland rice breeding. Heredity 2023, 131, 201–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerdes, J.T.; Tracy, W.F. Pedigree Diversity within the Lancaster Surecrop Heterotic Group of Maize. Crop Sci. 1993, 33, 334–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villegas, C.T.; Wilsie, C.P.; Frey, K.J. Recurrent Selection for High Self-Fertility in Vernal Alfalfa (Medicago sativa L.). Crop Sci. 1971, 11, 881–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertrand, A.; Rocher, S.; Claessens, A.; Bipfubusa, M.; Papadopoulos, Y.; Castonguay, Y. Biochemical and Molecular Responses during Overwintering of Red Clover Populations Recurrently Selected for Improved Freezing Tolerance. Plant Sci. 2020, 292, 110388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, M.; Nara, U.; Kumar, A.; et al. Enhancing genetic gains through marker-assisted recurrent selection: from phenotyping to genotyping. Cereal Research Communications 2022, 50, 523–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paudel, D.; Boogaard, H.; de Wit, A.; Janssen, S.; Osinga, S.; Pylianidis, C.; Athanasiadis, I.N. Machine Learning for Large-Scale Crop Yield Forecasting. Agric. Syst. 2021, 187, 103016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brejea, R.; Rosca, S.; Taut, F.D.; Bilașco, Ș.; Domuța, C.; Borza, I.M. Quantitative GIS Model for Evaluating the Favorability of Alfalfa (Medicago sativa L.) Culture for Suitable Varieties in Romania: Case Study Bihor County. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 4205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dillehay, B.L.; Curran, W.S.; Mortensen, D.A. Critical Period for Weed Control in Alfalfa. Weed Science 2011, 59, 68–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karadavut, U.; Palta, C. COMPARISON OF SOME MATHMATICAL GROWTH MODELS FOR ESTIMATING OF PYHSIOLOGICAL GROWTH CHARACTERS OF ALFALFA (Medicago Sativa L.). J. Glob. Innov. Agric. Sci. 2021, 9, 11–15. [Google Scholar]

- Vance, J.; Rasheed, K.; Missaoui, A.; Maier, F.; Adkins, C.; Whitmire, C. Comparing Machine Learning Techniques for Alfalfa Biomass Yield Prediction. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2210.11226. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, S.; Ge, Y.; Wang, J.; Liu, R.; Fu, L. Predicting Alfalfa Leaf Area Index by Non-Linear Models and Deep Learning Models. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bergua, M.; Luis-Arteaga, M.; Escriu, F. Comparison of Logistic Regression and Growth Function Models for the Analysis of the Incidence of Virus Infection. Span. J. Agric. Res. 2008, 6, 170–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Identification of Fertility Regimes That Enhance Long-Term Productivity of Alfalfa Using Cluster Analysis. Agronomy Journal 2010, 102, 580–591. [CrossRef]

- Monirifar, H. Path Analysis of Yield and Quality Traits in Alfalfa. Not. Bot. Horti Agrobot. Cluj-Napoca 2011, 39, 190–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genetic Mapping Forage Yield, Plant Height, and Regrowth at Multiple Harvests in Tetraploid Alfalfa (Medicago Sativa L.). Crop Science 2007, 47, 11–18. [CrossRef]

- Effects of Nitrogen and Phosphorus Fertilization on Photosynthetic Properties of Leaves and Agronomic Characters of Alfalfa over Three Consecutive Years. Agriculture 2022, 12, 1187. [CrossRef]

- Genetic Mapping of Leaf-Related Traits in Autotetraploid Alfalfa (Medicago Sativa L.). Molecular Breeding 2019, 39, 147. [CrossRef]

- Tucak, M.; Popović, S.; Grljušić, S.; Čupić, T.; Kozumplik, V.; Šimić, B. Variability and Relationships of Important Alfalfa Germplasm Agronomic Traits. Period. Biol. 2008, 110, 311–315. [Google Scholar]

- Genetic Diversity, Analysis of Some Agro-Morphological and Quality Traits and Utilization of Plant Resources of Alfalfa. Genes 2022, 13, 1521. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Genetic Diversity and Salt Tolerance Assessment of 51 Alfalfa (Medicago Sativa) Varieties under Saline Soil Conditions. Frontiers 2023, 7, 1278913. [CrossRef]

- Greveniotis, V.; Bouloumpasi, E.; Skendi, A.; Korkovelos, A.; Kantas, D.; Zotis, S.; Ipsilandis, C.G. Modeling Stability of Alfalfa Yield and Main Quality Traits. Agriculture 2024, 14, 542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farshadfar, M.; Kakaei, M.; Salehabadi, Y.; Baghaeifar, Z.; Jaffari, A. ashraf Study of Diversity for Yield and Quality Traits in Alfalfa Medicago Sativa L.) and Determination of the Best Population for Cultivation in Dryland Farming in Iran. J. Rangel. Sci. 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leveraging Logistic Models to Enhance Nutrient Dynamics Modeling in Intercropped Spring Wheat with Varied Nitrogen and Phosphorus Fertilization Strategies. PLOS ONE 2024, 19, e0314264. [CrossRef]

- Adjusting the growth curve of sugarcane varieties using nonlinear models. Cienc. Rural 2020. [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z. Research of applicability and growth feature for alfalfa in Jianghuai region of China. Doctoral, Gansu Agricultural University, Lanzhou, 2010. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Palosuo, T.; Kersebaum, K.C.; Angulo, C.; Hlavinka, P.; Moriondo, M.; Olesen, J.E.; Patil, R.H.; Ruget, F.; Rumbaur, C.; Takáč, J.; et al. Simulation of Winter Wheat Yield and Its Variability in Different Climates of Europe: A Comparison of Eight Crop Growth Models. Eur. J. Agron. 2011, 35, 103–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, M.; Technow, F.; Messina, C.; Gho, C.; Totir, L.R. Use of Crop Growth Models with Whole-Genome Prediction: Application to a Maize Multienvironment Trial. Crop Sci. 2016, 56, 2141–2156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, X.; Struik, P.C.; Kropff, M.J. Role of Crop Physiology in Predicting Gene-to-Phenotype Relationships. Trends Plant Sci. 2004, 9, 426–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| No. | Code | Strain/lines and sources | Origins | Region |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | A5 | S1 | Huaiyin alfalfa × Huaiyin alfalfa | Yangzhou |

| 2 | A12 | BC1 | F1 × Huaiyin alfalfa |

Yangzhou |

| 3 | C9 | Clone | Huaiyin Alfalfa Cutting | Yangzhou |

| 4 | C17 | BC2 | BC1 × Huaiyin alfalfa |

Yangzhou |

| 5 | D7 | BC1 | F1 × Huaiyin alfalfa |

Yangzhou |

| 6 | D8 | Clone | Huaiyin Alfalfa Cutting | Yangzhou |

| 7 | D9 | Clone | Huaiyin Alfalfa Cutting | Yangzhou |

| 8 | D28 | BC1 | F1 × Huaiyin alfalfa |

Yangzhou |

| 9 | E1 | Hangmu No. 1 | Space-induced mutation |

Lanzhou |

| 10 | E5 | S2 | S1 × S1 | Yangzhou |

| 11 | F6 | S2 | S1 × S1 | Yangzhou |

| 12 | F13 | BC2 | BC1 × Huaiyin alfalfa |

Yangzhou |

| 13 | G12 | S2 | S1 × S1 | Yangzhou |

| 14 | G20 | BC2 | BC1 × Huaiyin alfalfa |

Yangzhou |

| 15 | G24 | BC2 | BC1 × Huaiyin alfalfa |

Yangzhou |

| 16 | J27 | BC1 | F1 × Huaiyin alfalfa |

Yangzhou |

| 17 | M27 | BC2 | BC1 × Huaiyin alfalfa |

Yangzhou |

| 18 | Q12 | BC2 | BC1 × Huaiyin alfalfa |

Yangzhou |

| 19 | L20 | S1 | Huaiyin alfalfa × Huaiyin alfalfa | Yangzhou |

| 20 | L21 | S1 | Huaiyin alfalfa × Huaiyin alfalfa | Yangzhou |

| Strain/lines | Plant height | Number of Branches | leaf area | Multiple leaf rate | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2022 | 2023 | 2022 | 2023 | 2022 | 2023 | 2022 | 2023 | |

| A5 | 69±6.56abcd | 53.7±9.65fg | 130 | 184 | 10.71±2.15a | 9.87±3.89a | 0.32±0.23c | 0.3±0.09c |

| A12 | 58.67±2.08cdef | 62.7±10.03def | 112 | 84 | 4.07±1.16e | 9.69±3.31a | 0.63±0.2b | 0.67±0.07b |

| C9 | 37±15.39hi | 84.9±6.68abc | 37 | 84 | 5.36±2.89cde | 4.44±0.78cd | 0 | 0 |

| C17 | 72.33±4.73abc | 90.47±5.04a | 167 | 223 | 4.42±1.19de | 4.88±0.87cd | 0.05±0.03e | 0.05±0.01d |

| D7 | 52.33±5.51efg | 60.5±17.32def | 126 | 220 | 4.99±1.4cde | 5.25±0.74bcd | 0.32±0.02c | 0.3±0.09c |

| D8 | 35.33±6.11hi | 69.33±4.59cdef | 27 | 81 | 5.48±1.54cde | 4.81±1.09cd | 0 | 0 |

| D9 | 32.67±6.11i | 64.63±4.34def | 31 | 86 | 5.26±2.33cde | 3.7±0.55d | 0 | 0 |

| D28 | 68±4.36abcd | 64.93±10.4def | 97 | 220 | 8.23±2.13b | 4.76±0.49cd | 0.04±0.03e | 0.08±0.02d |

| E1 | 57.33±8.5def | 54.3±6.17fg | 104 | 170 | 7.33±2.5bc | 7.64±2.51ab | 0.91±0.08a | 0.95±0.05a |

| E5 | 48.33±4.04fgh | 21.13±1.2h | 86 | 35 | 8.3±2.06b | 6.55±0.78bc | 0.11±0.03de | 0.09±0.01d |

| F6 | 48±6.56fgh | 84.73±11.84abc | 63 | 138 | 6.81±2.67bcd | 5.94±1.42bcd | 0 | 0 |

| F13 | 55.33±3.51def | 59±7.11ef | 47 | 187 | 9.2±2.67ab | 4.83±1.23cd | 0.05±0.06e | 0.03±0.03d |

| G12 | 76±10.15ab | 87.87±6.72ab | 120 | 114 | 3.6±0.72e | 5.63±2.57bcd | 0.01±0.02e | 0.01±0.02d |

| G20 | 79.67±14.22a | 73.23±5.32bcde | 133 | 237 | 4.59±1.72de | 5.81±2.34bcd | 0.01±0.01e | 0.05±0.06d |

| G24 | 65±1.73abcde | 74.1±7.69bcde | 113 | 313 | 4.12±1.08e | 5.15±1.81bcd | 0.29±0.09cd | 0.3±0.02c |

| J27 | 68.33±8.02abcd | 62.27±11.83def | 73 | 255 | 3.64±1.19e | 4.47±1.08cd | 0.53±0.22b | 0.61±0.17b |

| M27 | 62±9.54bcdef | 75.8±4.56abcd | 118 | 161 | 4.13±1.11e | 4.55±0.94cd | 0.03±0.01e | 0.02±0.02d |

| Q12 | 39.67±2.52ghi | 42±5.47g | 104 | 112 | 7.26±1.34bc | 6.56±2.5bcd | 0.91±0.03a | 0.94±0.05a |

| L20 | 65±9.85abcde | 76.07±11.3abcd | 107 | 190 | 4.7±0.98cde | 4.77±0.75bcd | 0 | 0 |

| L21 | 74.67±6.66ab | 75.1±6.17abcde | 111 | 192 | 3.26±0.6e | 5.28±0.93bcd | 0 | 0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).