Submitted:

23 August 2024

Posted:

26 August 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

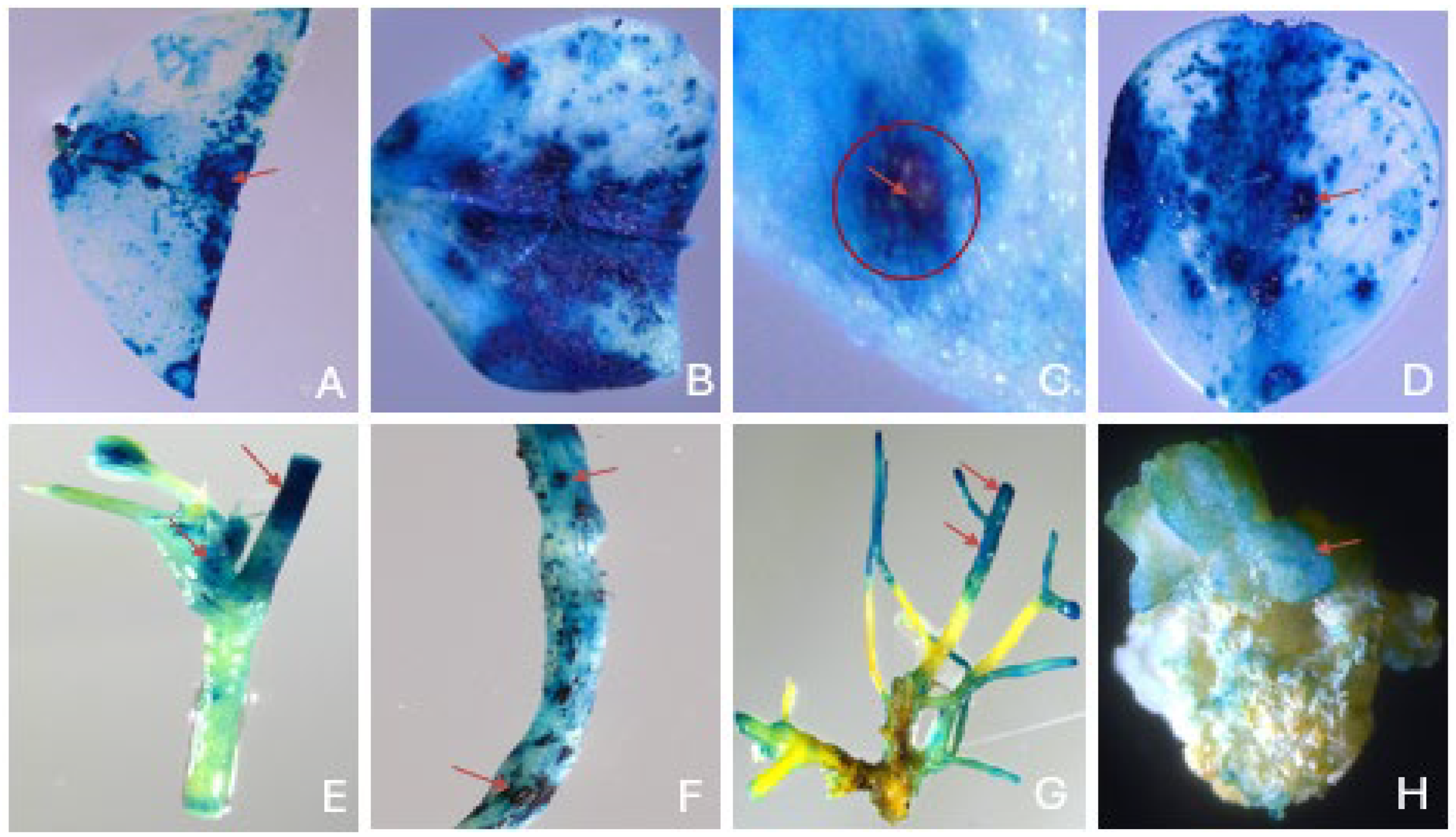

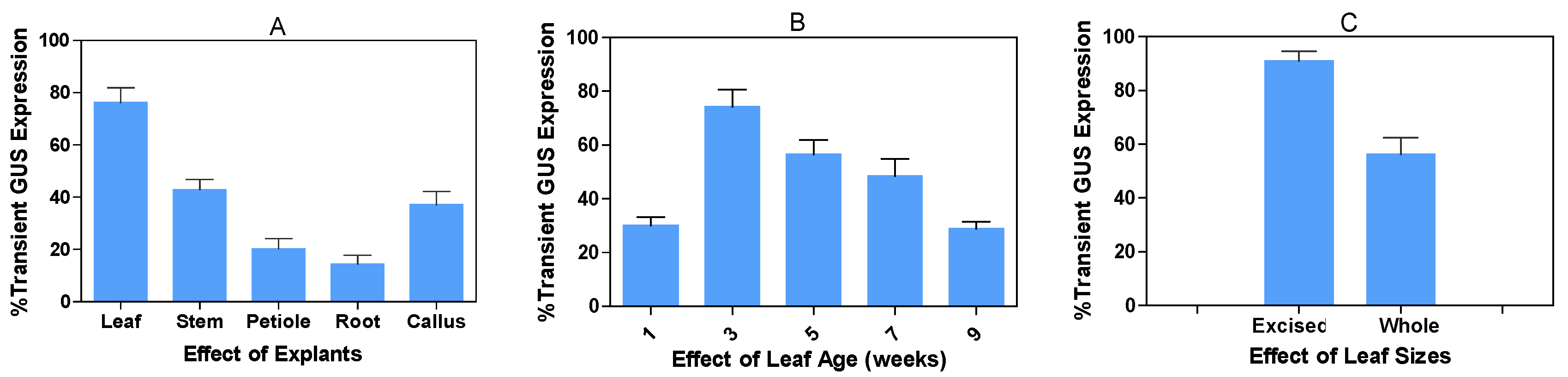

2.1. Effects of explant types, leaf age, and sizes of explants on transient GUS expression

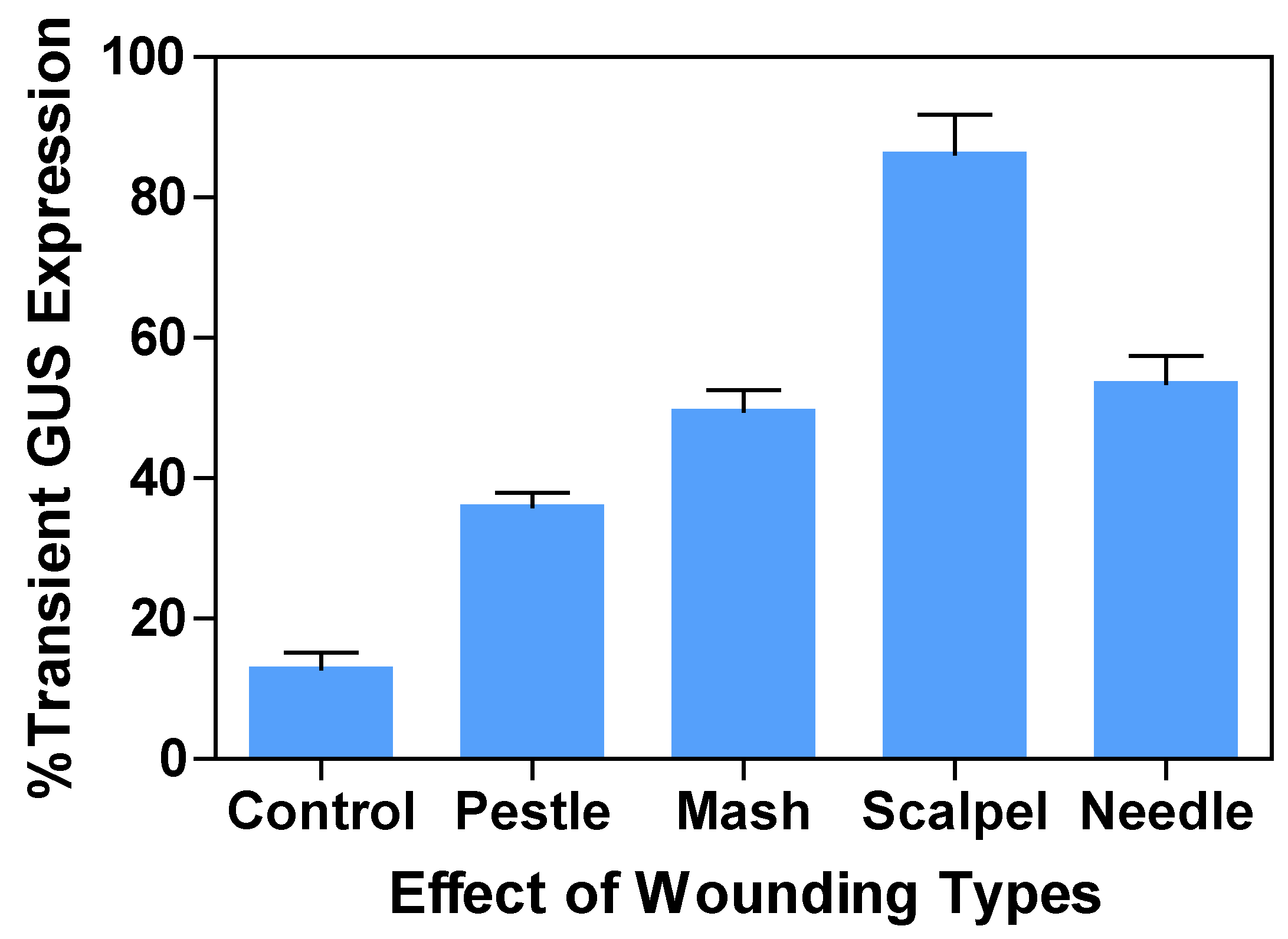

2.2. Effect of wounding types on transient GUS expression

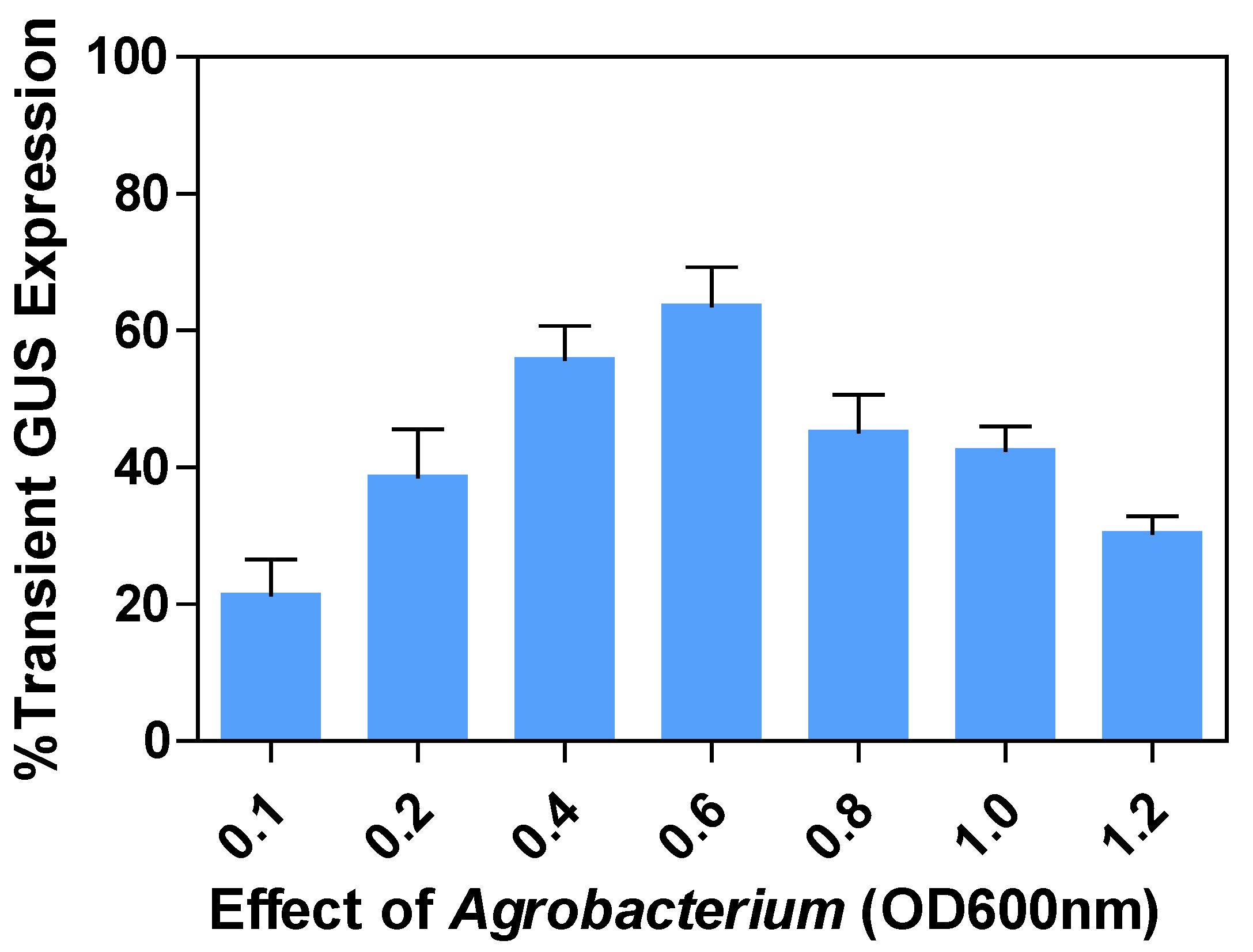

2.3. Effects of Agrobacterium concentration or optimal density (OD600nm) on transient GUS expression

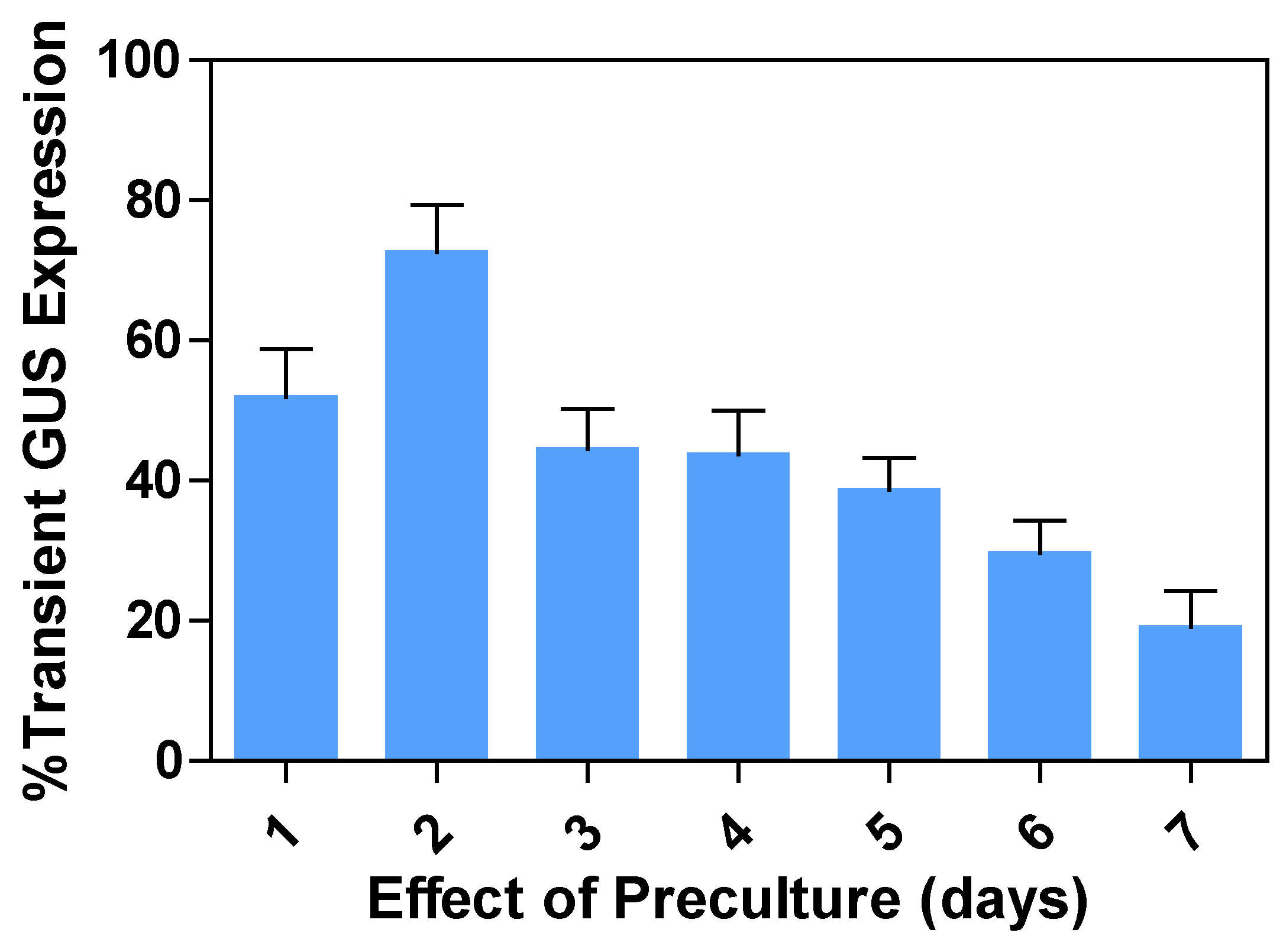

2.4. Effects of preculture periods on transient GUS expression

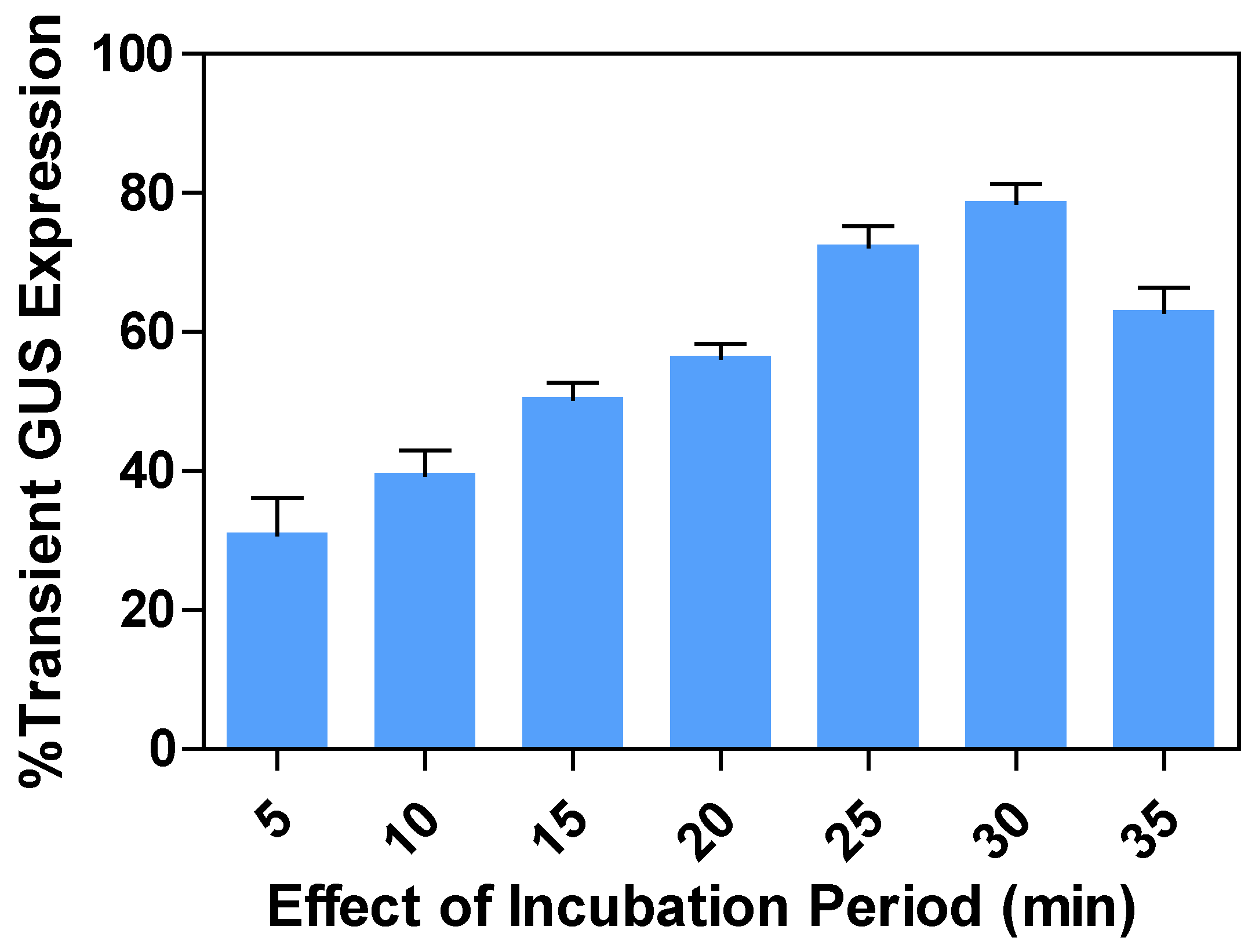

2.5. Effects of incubation periods on transient GUS expression

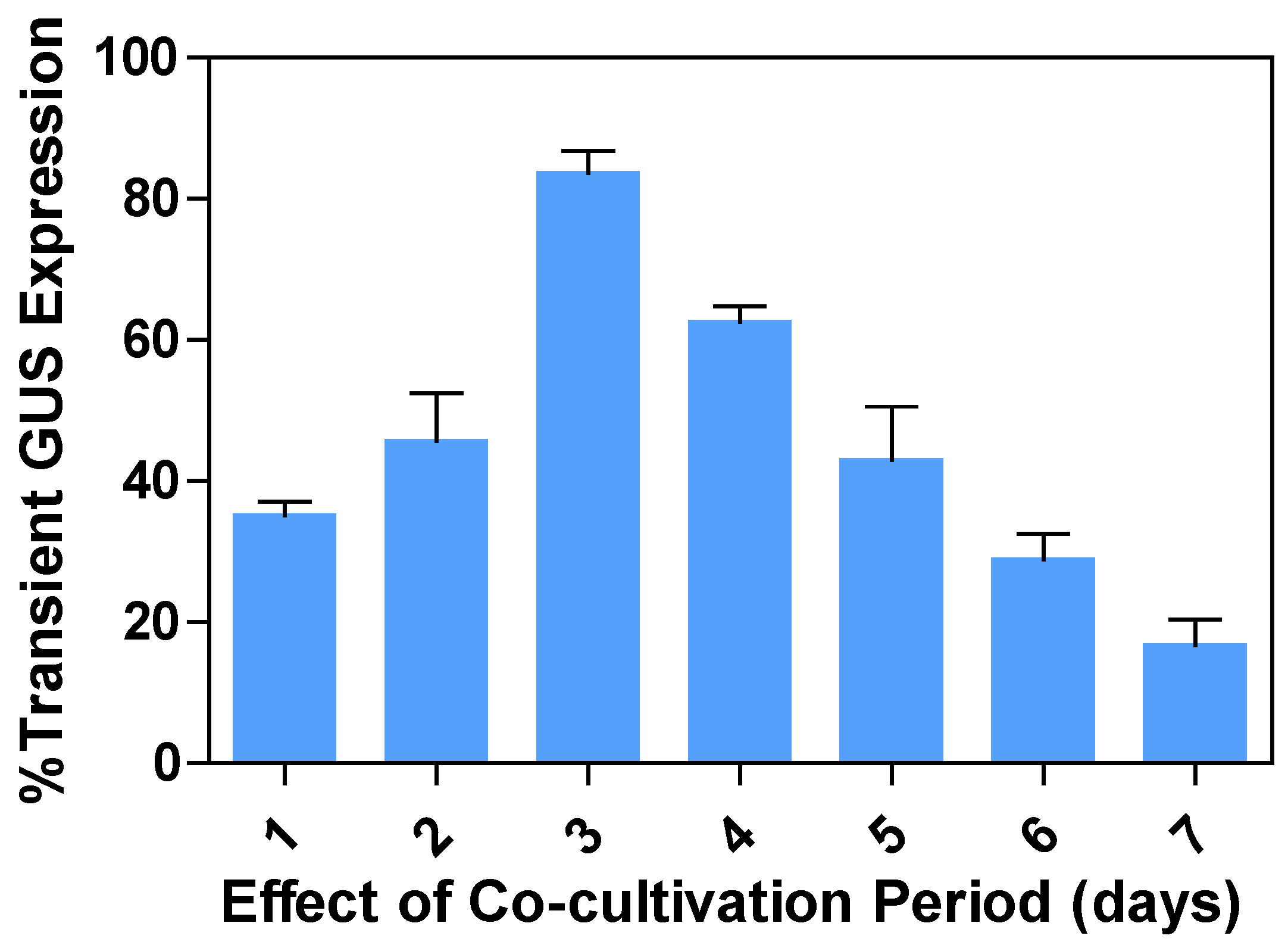

2.6. Effects of the co-cultivation or post-incubation period on transient GUS expression

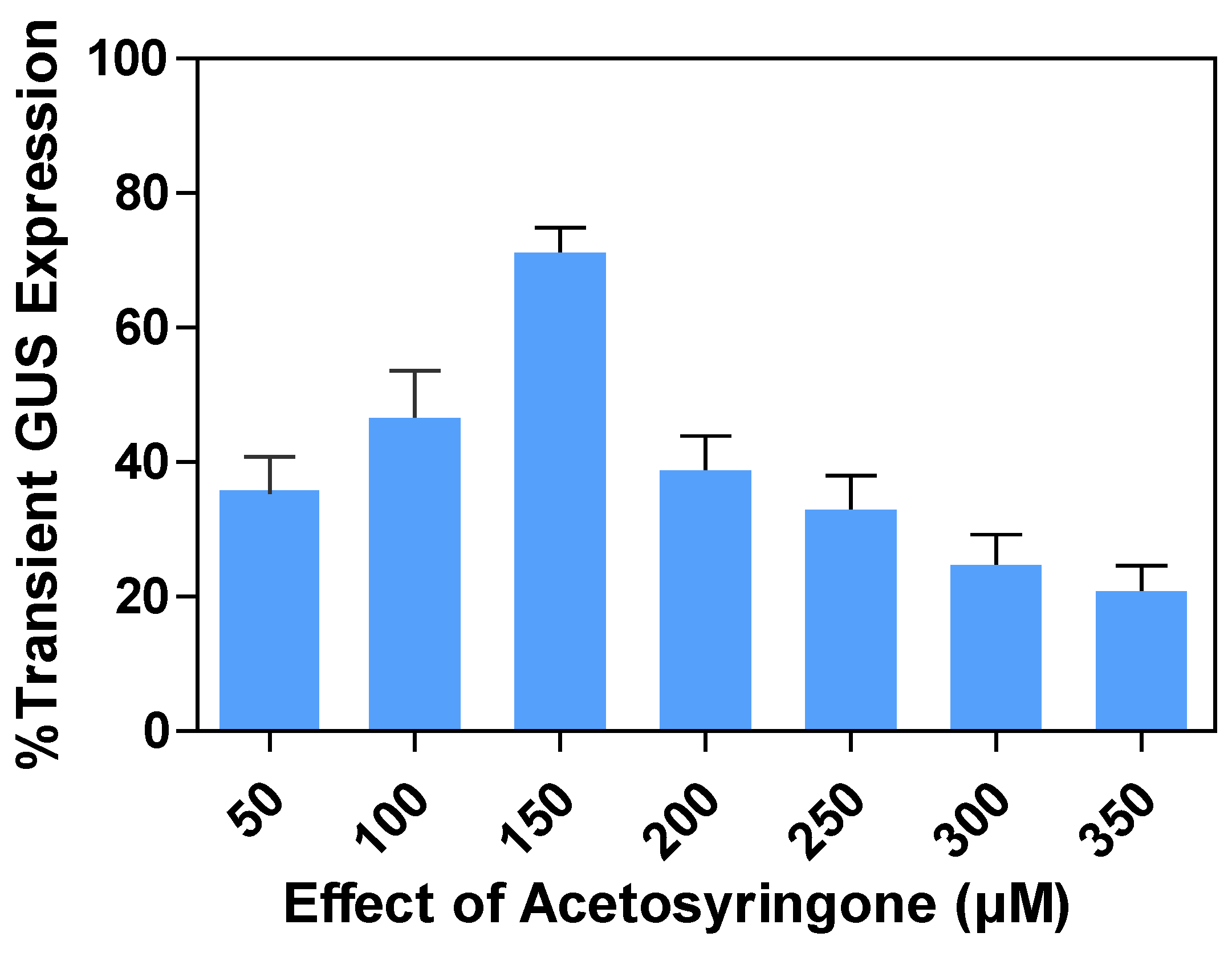

2.7. Effects of acetosyringone concentrations on transient GUS expression

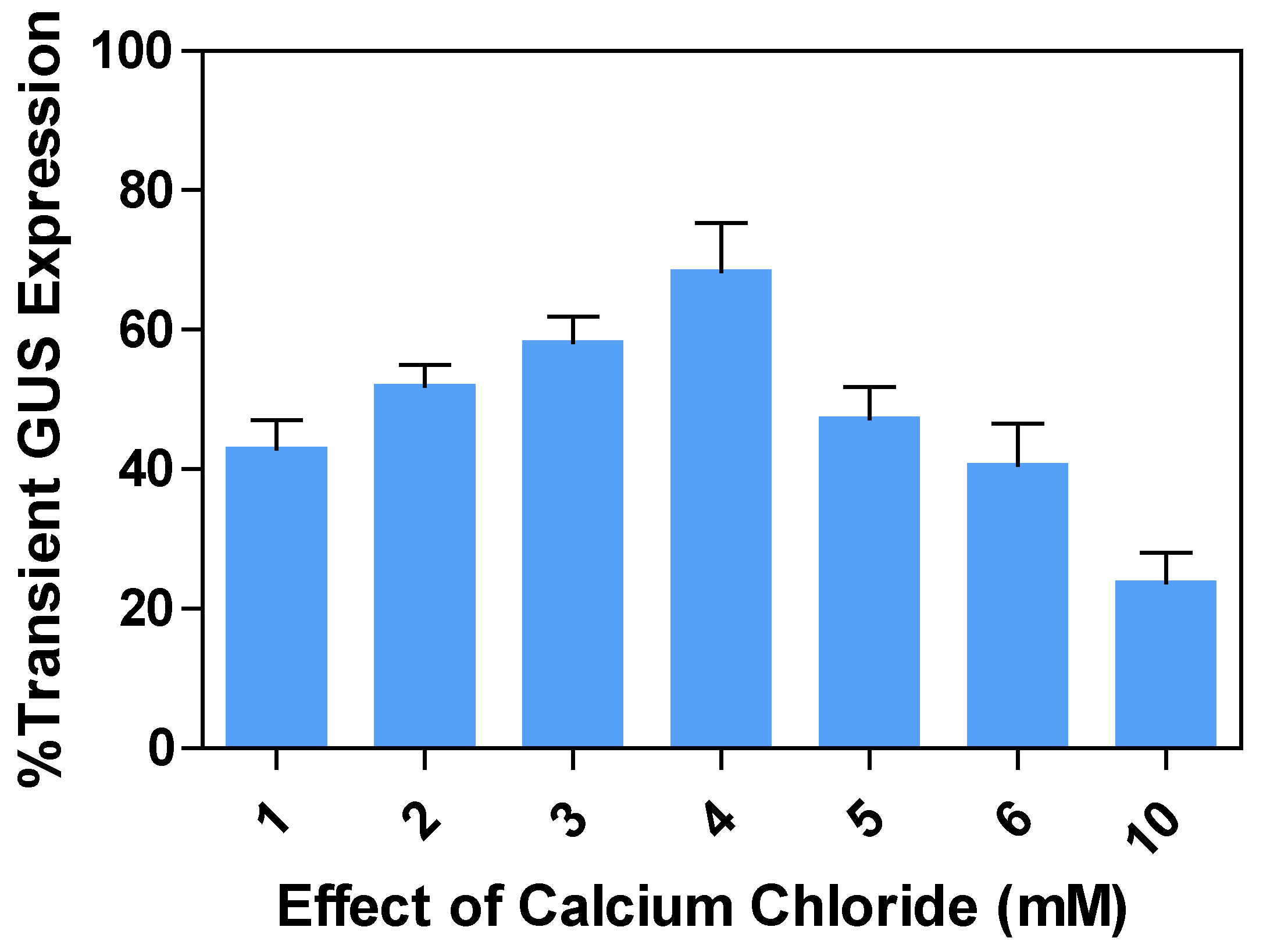

2.8. Effects of calcium chloride (CaCl2) concentrations on transient GUS expression

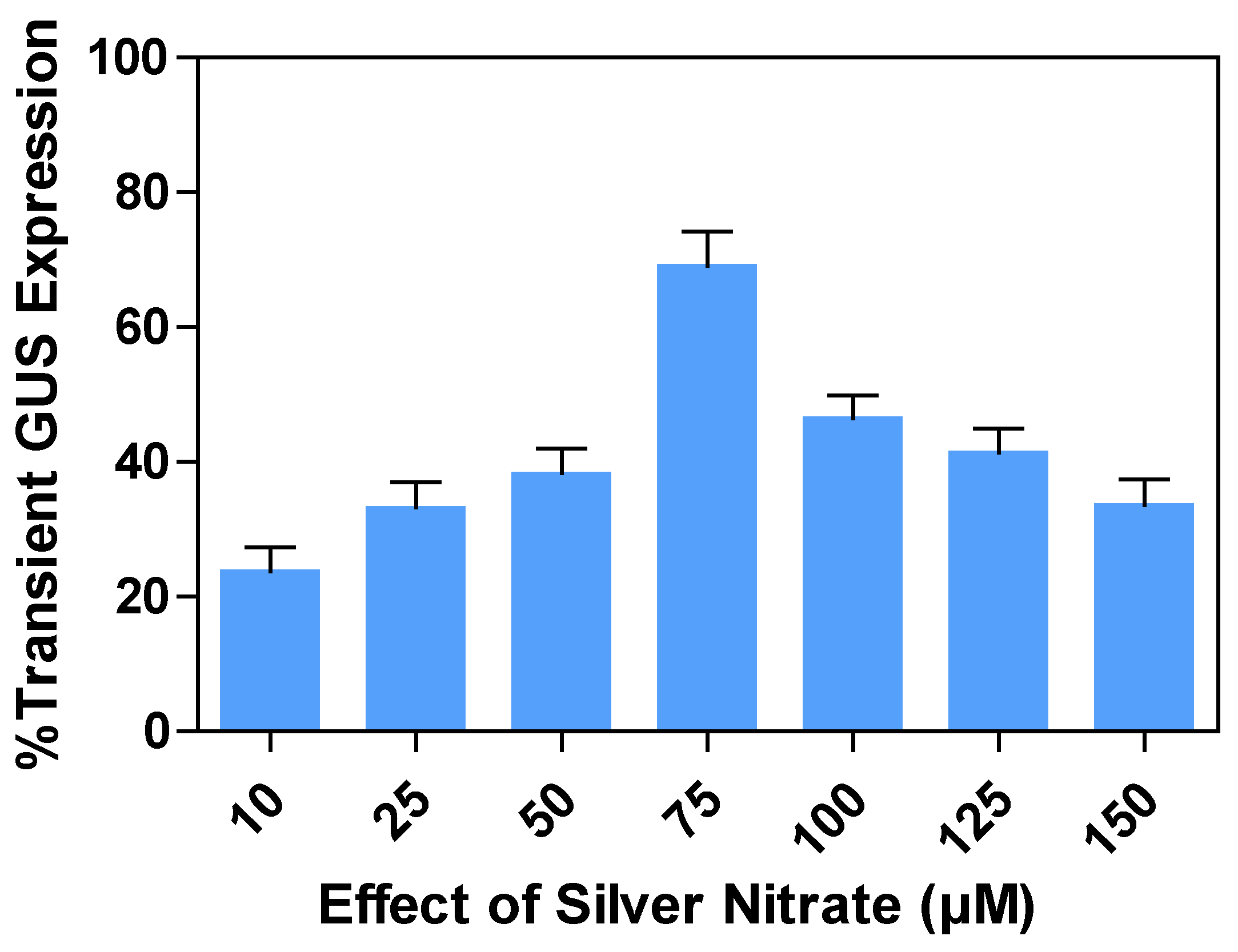

2.9. Effects of silver nitrate (AgNO3) concentrations on transient GUS expression

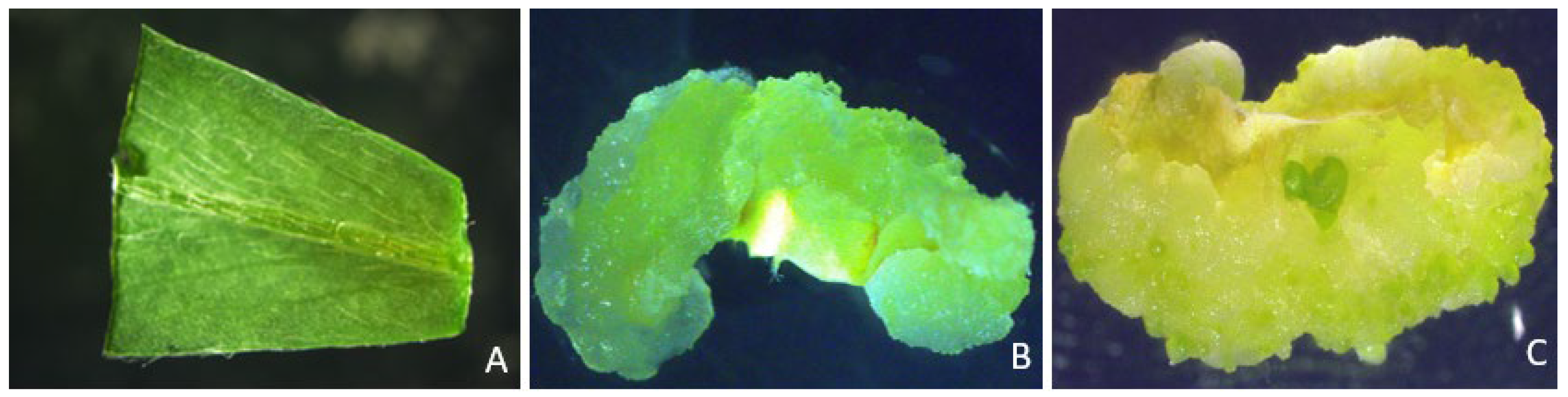

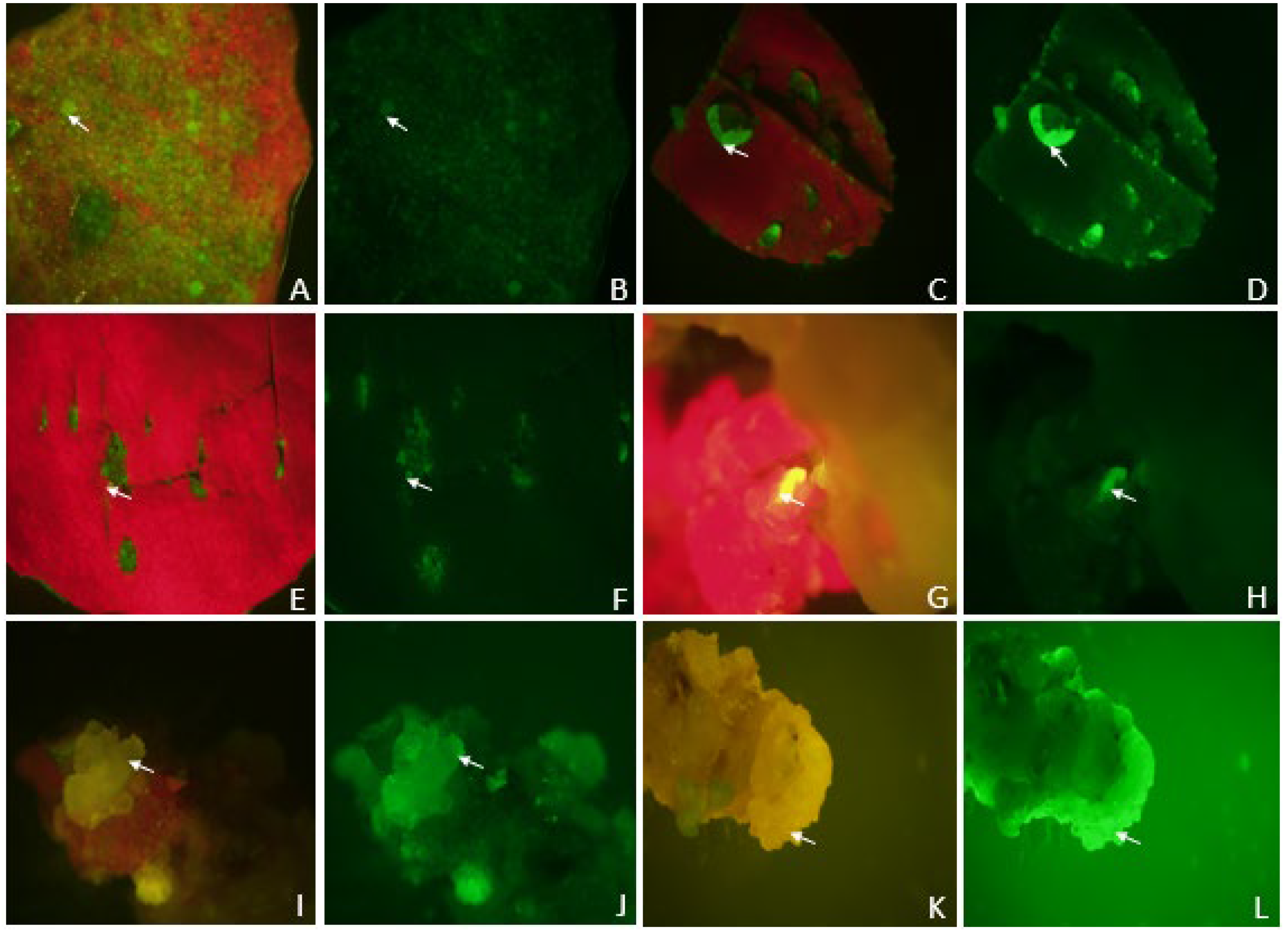

2.10. Green Fluorescence Protein (GFP) gene transient expression

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Establishment of In vitro cultures

4.2. Agrobacterium Strain and Plasmid Vector

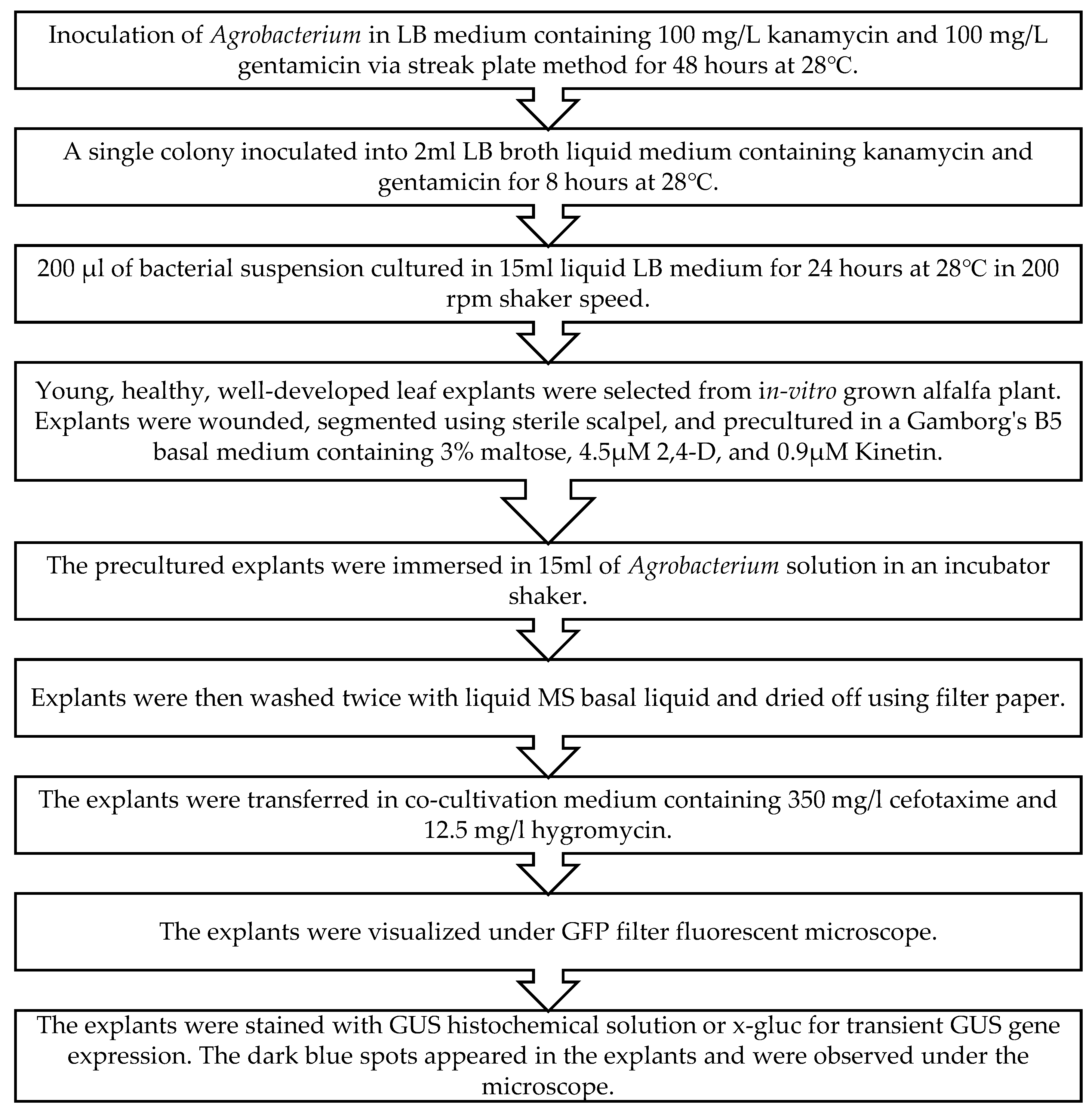

4.3. Inoculation and co-cultivation of alfalfa with A. tumefaciens

4.4. Optimization of transient gene expression parameters

4.5. GUS histochemical activity assay and GFP assay

4.6. Determination of Agrobacterium Infection Efficiency and Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yazicilar, B.; Chang, Y.L. Embryogenic Callus Differentiation in Short-Term Callus Derived from Leaf Explants of Alfalfa Cultivars. Natural Products and Biotechnology 2022, 2, 99–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bora, K.S.; Sharma, A. Phytochemical and pharmacological potential of Medicago sativa: A review. Pharmaceutical Biology 2011, 49, 211–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, G.; Grbic, V.; Ma, S.; Tian, L. Evaluation of somatic embryos of alfalfa for recombinant protein expression. Plant Cell Reports 2015, 34, 211–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nirola, R.; Megharaj, M.; Beecham, S.; Aryal, R.; Thavamani, P.; Vankateswarlu, K.; Saint, C. Remediation of metalliferous mines, revegetation challenges and emerging prospects in semi-arid and arid conditions. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 2016, 23, 20131–20150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, S. Biotechnological advancements in alfalfa improvement. Journal of Applied Genetics 2011, 52, 111–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tichá, M.; Illésová, P.; Hrbáčková, M.; Basheer, J.; Novák, D.; Hlaváčková, K.; Šamajová, O.; Niehaus, K.; Ovečka, M.; Šamaj, J. Tissue culture, genetic transformation, interaction with beneficial microbes, and modern bio-imaging techniques in alfalfa research. Critical Reviews in Biotechnology 2020, 40, 1265–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vignesh, M.; Shanmugavadivel, P.S.; Prabha, M.; Kokiladevi, E. Transformation Studies in Pea–A Review. Agricultural Reviews 2010, 31, 68–72. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, K.; Yang, Q.; Yang, T.; Wu, Y.; Wang, G.; Yang, F.; Wang, R.; Lin, X.; Li, G. Development of Agrobacterium-mediated transient expression system in Caragana intermedia and characterization of CiDREB1C in stress response. BMC Plant Biology 2019, 19, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Liang, Z.; Shan, C.; Marsolais, F.; Tian, L. Genetic transformation and full recovery of alfalfa plants via secondary somatic embryogenesis. In Vitro Cellular Developmental Biology-Plant 2013, 49, 17–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azizi-Dargahlou, S.; Pouresmaeil, M. (2023). Agrobacterium tumefaciens-mediated Plant Transformation: A Review. Molecular Biotechnology, 2023; 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Deak, M.; Kiss, G.B.; Koncz, C.; Dudits, D. Transformation of Medicago by Agrobacterium-mediated gene transfer. Plant Cell Reports 1986, 5, 97–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tohidfar, M.; Zare, N.; Jouzani, G.S.; Eftekhari, S.M. Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of alfalfa (Medicago sativa) using a synthetic cry3a gene to enhance resistance against alfalfa weevil. Plant Cell, Tissue and Organ Culture (PCTOC) 2013, 113, 227–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, T.; Chang, Q.; Li, W.; Yin, D.; Li, Z.; Wang, D.; Liu, B.; Liu, L. Stress-inducible expression of GmDREB1 conferred salt tolerance in transgenic alfalfa. Plant Cell, Tissue and Organ Culture (PCTOC) 2010, 100, 219–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.J.; Wang, T. Enhanced salt tolerance of alfalfa (Medicago sativa) by rstB gene transformation. Plant Science 2015, 234, 110–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avraham, T.; Badani, H.; Galili, S.; Amir, R. (2005). Enhanced levels of methionine and cysteine in transgenic alfalfa (Medicago sativa L.) plants over-expressing the Arabidopsis cystathionine γ-synthase gene. Plant Biotechnology Journal 2005, 3, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calderini, O.; Bovone, T.; Scotti, C.; Pupilli, F.; Piano, E.; Arcioni, S. Delay of leaf senescence in Medicago sativa transformed with the ipt gene controlled by the senescence-specific promoter SAG12. Plant Cell Reports 2007, 26, 611–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, B.; Gao, Y.; Wu, X.; Ma, H.; Zheng, C.; Wang, X.; Zhang, H.; Yang, H. The relative contributions of pH, organic anions, and phosphatase to rhizosphere soil phosphorus mobilization and crop phosphorus uptake in maize/alfalfa polyculture. Plant and Soil 2020, 447, 117–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komel, T.; Bosnjak, M.; Sersa, G.; Cemazar, M. Expression of GFP and DsRed fluorescent proteins after gene electrotransfer of tumor cells in vitro. Bioelectrochemistry 2023, 108490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Udayabhanu, J.; Huang, T.; Xin, S.; Cheng, J.; Hua, Y.; Huang, H. Optimization of the transformation protocol for increased efficiency of genetic transformation in Hevea brasiliensis. Plants 2022, 11, 1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sreeramanan, S.; Maziah, M.; Abdullah, M.P.; Sariah, M.; Xavier, R. Transient expression of gusA and gfp gene in Agrobacterium-mediated banana transformation using single tiny meristematic bud. Asian Journal of Plant Science 2006, 5, 468–480. [Google Scholar]

- Jefferson, R.A. Assaying chimeric genes in plants: the GUS gene fusion system. Plant Molecular Biology Reporter 1987, 5, 387–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimomura, O.; Johnson, F.H.; Saiga, Y. Extraction, purification and properties of aequorin, a bioluminescent protein from the luminous hydromedusan, Aequorea. Journal of Cellular and Comparative Physiology 1962, 59, 223–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Y.; Wang, D.; Fu, J.; Zhang, Z.; Qin, Y.; Hu, G.; Zhao, J. Agrobacterium rhizogenes-mediated hairy root transformation as an efficient system for gene function analysis in Litchi chinensis. Plant Methods 2021, 17, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.Y.; Brummer, E.C. Is genetic engineering ever going to take off in forage, turf and bioenergy crop breeding? Annals of Botany 2012, 110, 1317–1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Austin, S.; Bingham, E.T.; Mathews, D.E.; Shahan, M.N.; Will, J.; Burgess, R.R. Production and field performance of transgenic alfalfa (Medicago sativa L.) expressing alpha-amylase and manganese-dependent lignin peroxidase. In The Methodology of Plant Genetic Manipulation: Criteria for Decision Making: Proceedings of the Eucarpia Plant Genetic Manipulation Section Meeting held at Cork, Ireland. Springer Netherlands, 1995, September 11 to September 14, pp. 381–393.

- Samac, D.A.; Austin-Phillips, S. Alfalfa (Medicago sativa L.). Agrobacterium Protocols 2006, 301–312. [Google Scholar]

- Shahin, E.A.; Spielmann, A.; Sukhapinda, K.; Simpson, R.B.; Yashar, M. Transformation of Cultivated Alfalfa Using Disarmed Agrobacterium tumefaciens. Crop Science 1986, 26, 1235–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bingham, E.T. Registration of alfalfa hybrid Regen-SY germplasm for tissue culture and transformation research. Crop Science 1991, 31, 1098–1118. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, F.; Srinivasa Reddy, M.S.; Temple, S.; Jackson, L.; Shadle, G.; Dixon, R.A. Multi-site genetic modulation of monolignol biosynthesis suggests new routes for formation of syringyl lignin and wall-bound ferulic acid in alfalfa (Medicago sativa L.). The Plant Journal 2006, 48, 113–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, H.Z.; Min, X.; Zhang, B.; Kim, D.S.; Yan, X.; Zhang, C.J. Optimization and establishment of Agrobacterium-mediated transformation in alfalfa (Medicago sativa L.) using eGFP as a visual reporter. Plant Cell, Tissue and Organ Culture (PCTOC) 2024, 156, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Q.; Fu, C.; Wang, Z.Y. A unified Agrobacterium-mediated transformation protocol for alfalfa (Medicago sativa L.) and Medicago truncatula. Transgenic Plants: Methods and Protocols 2019, 153–163. [Google Scholar]

- Ninkovié, S. ; J. Miljus-Djukic, J.; Vinterhalter, B.; Neskovic, M. Improved transformation of alfalfa somatic embryos using a superbinary vector. Acta Biologica Cracoviensia Series Botanica, 2004; 46, 139–143. [Google Scholar]

- Rosellini, D. , Stefano, C.; Nicoletta, F.; Maria, L.S.S.; Alessandro, N.; Fabio, V. Non-antibiotic, efficient selection for alfalfa genetic engineering. Plant cell reports 2007, 26, 1035–1044. [Google Scholar]

- Weeks, J.T.; Ye, J.; Rommens, C.M. Development of an in-planta method for transformation of alfalfa (Medicago sativa). Transgenic Research 2008, 17, 587–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Huang, Q.M.; Jin, S.U. Development of alfalfa (Medicago sativa L.) regeneration system and Agrobacterium-mediated genetic transformation. Agricultural Sciences in China 2010, 9, 170–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Chang, Q.; Huang, L.; Wei, P.; Song, Y.; Guo, Z.; Peng, Y.; Fan, J. An Agrobacterium-mediated Transient Expression Method for Functional Assay of Genes Promoting Disease in Monocots. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2023, 24, 7636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dubey, N.K.; Eizenberg, H.; Edelstein, M.; Gal-On, A.; Aly, R. Enhanced host-parasite resistance based on down-regulation of Phelipanche aegyptiaca target genes is likely by mobile small RNA. Frontiers in Plant Science 2017, 8, 251119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, M.; Manchanda, P.; Kalia, A.; Ahmed, F.K.; Nepovimova, E.; Kuca, K.; Abd-Elsalam, K.A. Agroinfiltration mediated scalable transient gene expression in genome-edited crop plants. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2021, 22, 10882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.Y.; Liu, K.H.; Wang, Y.C.; Wu, J.F.; Chiu, W.L.; Chen, C.Y.; Wu, S.H.; Sheen, J.; Lai, E.M. AGROBEST: an efficient Agrobacterium-mediated transient expression method for versatile gene function analyses in Arabidopsis seedlings. Plant Methods 2014, 10, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spiegel, H.; Schillberg, S.; Nölke, G. Production of Recombinant Proteins by Agrobacterium-mediated Transient Expression. In Recombinant Proteins in Plants: Methods and Protocols. New York, NY: Springer US, 2022, pp. 89–102.

- Laforest, L.C.; Nadakuduti, S.S. Advances in delivery mechanisms of CRISPR gene-editing reagents in plants. Frontiers in Genome Editing 2022, 4, 830178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatt, R.; Asopa, P.P.; Jain, R.; Kothari-Chajer, A.; Kothari, S.L.; Kachhwaha, S. Optimization of Agrobacterium mediated genetic transformation in Paspalum scrobiculatum L. (Kodo Millet). Agronomy 2021, 11, 1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atif, R.M.; Patat-Ochatt, E.M.; Svabova, L.; Ondrej, V.; Klenoticova, H.; Jacas, L.; Griga, M.; Ochatt, S.J. Gene transfer in legumes. In Progress in Botany: Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 2012, Vol. 74, pp. 37–100.

- Li, S.; Cong, Y.; Liu, Y.; Wang, T.; Shuai, Q.; Chen, N.; Gai, J.; Li, Y. Optimization of Agrobacterium-mediated transformation in soybean. Frontiers in Plant Science 2017, 8, 246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naderi, D.; Zohrabi, Z.; Shakib, A.M.; Mahmoudi, E.; Khasmakhi-Sabet, S.A.; Olfati, J.A. Optimization of micropropagation and Agrobacterium-mediated gene transformation to spinach (Spinacia oleracea L.). Advances in Bioscience and Biotechnology 2012, 3, 876–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadhu, S.K.; Jogam, P.; Gande, K.; Banoth, R.; Penna, S.; Peddaboina, V. Optimization of different factors for an Agrobacterium-mediated genetic transformation system using embryo axis explants of chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.). Journal of Plant Biotechnology 2022, 49, 61–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salazar-González, J.; Castro-Medina, M.; Martínez-Terrazas, E.; Casson, S.A.; Urrea-Lopez, R. Leaf wounding and jasmonic acid act synergistically to enable efficient Agrobacterium-mediated transient transformation of Persea americana. Research Square 2022, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Hada, A.; Krishnan, V.; Mohamed Jaabir, M.S.; Kumari, A.; Jolly, M.; Praveen, S.; Sachdev, A. Improved Agrobacterium tumefaciens-mediated transformation of soybean [Glycine max (L.) Merr.] following optimization of culture conditions and mechanical techniques. In Vitro Cellular Developmental Biology-Plant 2018, 54, 672–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koetle, M.J.; Baskaran, P.; Finnie, J.F.; Soos, V.; Balázs, E.; Van Staden, J. Optimization of transient GUS expression of Agrobacterium-mediated transformation in Dierama erectum Hilliard using sonication and Agrobacterium. South African Journal of Botany 2017, 111, 307–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.L.; Xu, M.X.; Yin, G.X.; Tao, L.L.; Wang, D.W.; Ye, X.G. Transgenic wheat plants derived from Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of mature embryo tissues. Cereal Research Communications 2009, 37, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, J.; Datta, S.; Mishra, S.P. Development of an efficient Agrobacterium- mediated transformation system for chickpeas (Cicer arietinum). Biologia 2017, 72, 153–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, S.K.; Katikala, S.; Yellisetty, V.; Kannepalle, A.; Narayana, J.L.; Maddi, V.; Mandapaka, M.; Shanker, A.K.; Bandi, V.; Bharadwaja, K.P. Optimization of Agrobacterium-mediated genetic transformation of cotyledonary node explants of Vigna radiata. Springer Plus 2012, 1, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahman, Z.A.; Seman, Z.A.; Basirun, N.; Julkifle, A.L.; Zainal, Z.; Subramaniam, S. Preliminary investigations of Agrobacterium-mediated transformation in indica rice MR219 embryogenic callus using gusA gene. African Journal of Biotechnology 2011, 10, 7805–7813. [Google Scholar]

- Tripathi, L.; Singh, A.K.; Singh, S.; Singh, R.; Chaudhary, S.; Sanyal, I.; Amla, D.V. Optimization of regeneration and Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of immature cotyledons of chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.). Plant Cell, Tissue and Organ Culture (PCTOC) 2013, 113, 513–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, A.; Datta, S.; Thakur, S.; Shukla, A.; Ansari, J.; Sujayanand, G.K.; Chaturvedi, S.K.; Kumar, P.A.; Singh, N.P. Expression of a chimeric gene encoding insecticidal crystal protein Cry1Aabc of Bacillus thuringiensis in chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.) confers resistance to gram pod borer (Helicoverpa armigera Hubner.). Frontiers in Plant Science 2017, 8, 1423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das Bhowmik, S.S.; Cheng, A.Y.; Long, H.; Tan, G.Z.H.; Hoang, T.M.L.; Karbaschi, M.R.; Williams, B.; Higgins, T.J.V.; Mundree, S.G. Robust genetic transformation system to obtain non-chimeric transgenic chickpeas. Frontiers in Plant Science 2019, 10, 524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Lin, M.; Chen, H.; Chen, X. Agrobacterium tumefaciens-mediated transformation of drumstick (Moringa oleifera Lam.). Biotechnology Biotechnological Equipment 2017, 31, 1126–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.J.; Wei, Z.M.; Huang, J.Q. The effect of co-cultivation and selection parameters on Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of Chinese soybean varieties. Plant Cell Reports 2008, 27, 489–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dutt, M.; Grosser, J.W. Evaluation of parameters affecting Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of citrus. Plant Cell, Tissue and Organ Culture (PCTOC) 2009, 98, 331–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina-Risco, M.; Ibarra, O.; Faion-Molina, M.; Kim, B.; Septiningsih, E.M.; Thomson, M.J. Optimizing Agrobacterium-mediated transformation and CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing in the tropical japonica rice variety presidio. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2021, 22, 10909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benny, A.; Alex, S.; Soni, K.B.; Anith, K.N.; Kiran, A.G.; Viji, M.M. (2022). Improved transformation of Agrobacterium assisted by silver nanoparticles. BioTechnologia 2022, 103, 311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruce, M.A.; Shoup Rupp, J.L. Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of Solanum tuberosum L.; potato. Transgenic Plants: Methods and Protocols 2019, 203–223. [Google Scholar]

- Gill, A.R.; Siwach, P. Agrobacterium rhizogenes mediated genetic transformation in Ficus religiosa L. and optimization of acetylcholinesterase inhibitory activity in hairy roots. South African Journal of Botany 2022, 151, 349–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prem Kumar, G.; Sivakumar, S.; Siva, G.; Vigneswaran, M.; Senthil Kumar, T.; Jayabalan, N. Silver nitrate promotes high-frequency multiple-shoot regeneration in cotton (Gossypium hirsutum L.) by inhibiting ethylene production and phenolic secretion. In Vitro Cellular Developmental Biology-Plant 2016, 52, 408–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arraes, F.B.M.; Beneventi, M.A.; Lisei de Sa, M.E.; Paixao, J.F.R.; Albuquerque, E.V.S.; Marin, S.R.R.; Purgatto, E.; Nepomuceno, A.L.; Grossi-de-Sa, M.F. Implications of ethylene biosynthesis and signaling in soybean drought stress tolerance. BMC Plant Biology 2015, 15, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Namukwaya, B.; Magambo, B.; Arinaitwe, G.; Oweitu, C.; Erima, R.; Tarengera, D.; Bossa, D.L.; Karamura, G.; Muwonge, A.; Kubiriba, J.; Tushemereirwe, W. Antioxidants enhance banana embryogenic cell competence to Agrobacterium-mediated transformation. African Journal of Biotechnology 2019, 18, 735–743. [Google Scholar]

- Sainger, M.; Chaudhary, D.; Dahiya, S.; Jaiwal, R.; Jaiwal, P.K. Development of an efficient in vitro plant regeneration system amenable to Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of a recalcitrant grain legume black gram (Vigna mungo L. Hepper). Physiology and Molecular Biology of Plants 2015, 21, 505–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- An, X.; Wang, B.; Liu, L.; Jiang, H.; Chen, J.; Ye, S.; Chen, L.; Guo, P.; Huang, X.; Peng, D. Agrobacterium-mediated genetic transformation and regeneration of transgenic plants using leaf midribs as explants in ramie [Boehmeria nivea (L. ) Gaud]. Molecular Biology Reports 2014, 41, 3257–3269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tiwari, V.; Chaturvedi, A.K.; Mishra, A.; Jha, B. An efficient method of Agrobacterium-mediated genetic transformation and regeneration in local Indian cultivar of groundnut (Arachis hypogaea) using grafting. Applied Biochemistry and Biotechnology 2015, 175, 436–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karthik, S.; Pavan, G.; Sathish, S.; Siva, R.; Kumar, P.S.; Manickavasagam, M. Genotype-independent and enhanced in planta Agrobacterium tumefaciens-mediated genetic transformation of peanut [Arachis hypogaea (L.)]. 3 Biotech 2018, 8, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arun, M.; Subramanyam, K.; Mariashibu, T.S.; Theboral, J.; Shivanandhan, G.; Manickavasagam, M.; Ganapathi, A. Application of sonication in combination with vacuum infiltration enhances the Agrobacterium-mediated genetic transformation in Indian soybean cultivars. Applied Biochemistry and Biotechnology 2015, 175, 2266–2287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mekala, G.K.; Juturu, V.N.; Mallikarjuna, G.; Kirti, P.B.; Yadav, S.K. Optimization of Agrobacterium-mediated genetic transformation of shoot tip explants of green gram (Vigna radiata (L. ) Wilczek). Plant Cell, Tissue and Organ Culture (PCTOC) 2016, 127, 651–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yong, W.T.L.; Abdullah, J.O.; Mahmood, M. Optimization of Agrobacterium-mediated transformation parameters for Melastomataceae spp. using green fluorescent protein (GFP) as a reporter. Scientia Horticulturae 2006, 109, 78–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Yang, D.; Liu, Y.; Han, F.; Li, Z. A highly efficient genetic transformation system for broccoli and subcellular localization. Frontiers in Plant Science 2023, 14, 1091588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapildev, G.; Chinnathambi, A.; Sivanandhan, G.; Rajesh, M.; Vasudevan, V.; Mayavan, S.; Arun, M.; Jeyaraj, M.; Alharbi, S.A.; Selvaraj, N.; Ganapathi, A. High-efficient Agrobacterium-mediated in planta transformation in black gram (Vigna mungo (L. ) Hepper). Acta Physiologiae Plantarum 2016, 38, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Tang, D.; Liu, Z.; Chen, J.; Cheng, B.; Kumar, R.; Yer, H.; Li, Y. An improved procedure for Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of ‘Carrizo’Citrange. Plants 2022, 11, 1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bett, B.; Gollasch, S.; Moore, A.; Harding, R.; Higgins, T.J. An improved transformation system for cowpea (Vigna unguiculata L. Walp) via sonication and a kanamycin-geneticin selection regime. Frontiers in Plant Science 2019, 10, 219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sabir, M.; Anwar, Y.; Khan, A.; Ali, M.; Yousuf, P.Y.; Al-Ghamdi, K. ChiC Gene Enhances Fungal Resistance in Indigenous Potato Variety (Diamant) via Agrobacterium-mediated Transformation. Biosciences Biotechnology Research Asia 2019, 16, 343–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cody, J.P.; Maher, M.F.; Nasti, R.A.; Starker, C.G.; Chamness, J.C.; Voytas, D.F. Direct delivery and fast-treated Agrobacterium co-culture (Fast-TrACC) plant transformation methods for Nicotiana benthamiana. Nature Protocols 2023, 18, 81–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sgamma, T.; Thomas, B.; Muleo, R. Ethylene inhibitor silver nitrate enhances regeneration and genetic transformation of Prunus avium (L. ) cv Stella. Plant Cell, Tissue and Organ Culture (PCTOC) 2015, 120, 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivanandhan, G.; Moon, J.; Sung, C.; Bae, S.; Yang, Z.H.; Jeong, S.Y.; Choi, S.R.; Kim, S.G.; Lim, Y.P. L-Cysteine increases the transformation efficiency of Chinese cabbage (Brassica rapa ssp. pekinensis). Frontiers in Plant Science 2021, 12, 767140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, X.F.; Yu, X.Q.; Zhou, Z.; Ma, W.J.; Tang, G.X. A high-efficiency Agrobacterium tumefaciens mediated transformation system using cotyledonary nodes as explants in soybean (Glycine max L. ). Acta Physiologiae Plantarum 2016, 38, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Yin, Q.; Kong, H.; Huang, Q.; Zuo, J.; He, L.; Guo, A. Effect of silver nitrate on Agrobacterium-mediated genetic transformation of cassava. Biotechnology Bulletin 2013, 166–170. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, H.; Zhang, Z.J. Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of maize (Zea mays) immature embryos. Cereal Genomics: Methods and Protocols 2014, 273–280. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.; Naing, A.H.; Park, K.I.; Kim, C.K. Silver nitrate reduces hyperhydricity in shoots regenerated from the hypocotyl of snapdragon cv. Maryland Apple Blossom. Scientia Horticulturae 2023, 308, 111593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kala, R.G.; Abraham, V.; Sobha, S.; Jayasree, P.K.; Suni, A.M.; Thulaseedharan, A. Agrobacterium-mediated genetic transformation and somatic embryogenesis from leaf callus of Hevea brasiliensis: effect of silver nitrate. In Prospects in Bioscience: Addressing the Issues. Springer India2013, 303–315.

- Hassan, M.F.; Islam, S.S. Effect of silver nitrate and growth regulators to enhance anther culture response in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). Heliyon 2021, 7.

- Sangra, A.; Shahin, L.; Dhir, S.K. Long-term maintainable somatic embryogenesis system in alfalfa (Medicago sativa) using leaf explants: embryogenic sustainability approach. Plants 2019, 8, 278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Gupta, S.; Bhat, V.; Gupta, M.G. Somatic embryogenesis and Agrobacterium-mediated genetic transformation in Indian accessions of lucerne (Medicago sativa L.). Indian Journal of Biotechnology 2006, 5, 269–275. [Google Scholar]

- Basak, S.; Parajulee, D.; Brearley, T.; Dhir, S. High-efficiency Somatic Embryogenesis and Plant Regeneration in Alfalfa (Medicago sativa L.). Society for In Vitro Biology (SIVB), Virginia, USA, 10-14 June 2023, P-2034.

- Parajulee, D.; Basak, S.; Dhir, S. (2023) Somatic Embryogenesis and Plant Regeneration from in vitro grown leaf explants from Alfalfa (Medicago sativa L.). American Society of Plant Biologist, Savannah, Georgia, USA, 5-9 August 2023, P-80039.

- Xia, P.; Hu, W.; Liang, T.; Yang, D.; Liang, Z. An attempt to establish an Agrobacterium-mediated transient expression system in medicinal plants. Protoplasma 2020, 257, 1497–1505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ratanasut, K.; Rod-In, W.; Sujipuli, K. In planta Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of rice. Rice Science 2017, 24, 181–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heidari Japelaghi, R.; Haddad, R.; Valizadeh, M.; Dorani Uliaie, E.; Jalali Javaran, M. High-efficiency Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum). Journal of Plant Molecular Breeding 2018, 6, 38–50. [Google Scholar]

- Pinthong, R.; Sujipuli, K.; Ratanasut, K. Agroinfiltration for transient gene expression in floral tissues of Dendrobium sonia ‘Earsakul’. Journal of Agricultural Technology 2014, 10, 459–465. [Google Scholar]

- Duncan, D.B. Multiple range and multiple F tests. Biometrics 1995, 11, 1–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).