1. Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) represents a significant global health burden, ranking as the fifth most commonly diagnosed malignancy and the second leading cause of cancer-related mortality worldwide [

1]. In Vietnam, CRC ranks as the fifth most prevalent malignancy. According to Globocan 2020 statistics, Vietnam reported approximately 16,000 new CRC cases and over 8,200 CRC-related fatalities. Early detection and accurate staging are critical for improving patient outcomes, as CRC prognosis varies considerably depending on the stage at diagnosis. While traditional diagnostic and staging methods primarily rely on imaging techniques and histopathological analyses, there is increasing interest in exploring immune-based biomarkers that could provide valuable insights into disease progression and treatment response.

The immune system plays a pivotal role in cancer development and progression, with both innate and adaptive immune components contributing to tumor surveillance, elimination and escape mechanisms [

2]. In CRC, dysregulation of the immune response is implicated in tumor growth, invasion and metastasis [

3]. Alterations of immune cell populations, including B, T and natural killer (NK) cells, as well as changes in cytokine profiles, have been reported in CRC patients compared to healthy individuals [

4,

5].

B cells, responsible for antibody production and antigen presentation to T cells, have demonstrated both pro-tumorigenic and anti-tumorigenic functions in the tumor microenvironment [

6]. Increased frequencies of regulatory B cells (Bregs) and alterations in B cell subsets have been associated with poor prognosis and metastasis due to suppression of anti-tumor immune responses [

7]. T cells, particularly CD8+ cytotoxic T cells and CD4+ helper cells, play a crucial role in anti-tumor immunity through their ability to recognize and eliminate tumor cells [

8]. However, the presence of immunosuppressive regulatory T cells (Tregs) and the exhaustion of effector T cells can impair anti-tumor immune responses in gastrointestinal cancers [

9]. NK cells, part of the innate immune system, can directly eliminate tumor cells and modulate the adaptive immune response through cytokine production [

10]. Dysregulation of NK cell activity has been linked to CRC progression and metastasis [

11].

In addition to cellular components, cytokines, which are signaling molecules produced by various leukocyte populations, play a crucial role in regulating the immune response in CRC [

12]. Pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as interleukin-6 (IL-6), tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), and interleukin-17 (IL-17), have been associated with tumor progression and poor prognosis, while anti-inflammatory cytokines like interleukin-10 (IL-10) and transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β) can suppress anti-tumor immunity [

13].

By comparing the distribution and functional characteristics of B cells, T cells, NK cells, and cytokine profiles between healthy individuals and CRC patients, this identifies immune-based biomarkers that could aid in early detection, prognostic evaluation and personalized treatment strategies for colorectal cancer.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population

The study population comprised 30 patients diagnosed with colorectal cancer (CRC) in late stage 1 or stage 2, recruited from the Vinmec Healthcare System and the 108 Military Central Hospital between September 25, 2021, and June 8, 2022. The cohort included 9 females and 21 males, with ages ranging from 32 to 91 years. All patients were treatment-naïve at the time of enrollment. Informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to their inclusion in the study.

For comparative analysis, data from the CRC patients were juxtaposed against reference values derived from a cohort of healthy Vietnamese subjects (n = 40; 25 females, 15 males; age range: 22-67 years), as reported in our recent publication [

14]. The healthy cohort was recruited contemporaneously with the CRC patients, employing identical methodologies for comprehensive immune system analysis to ensure comparability.

All study procedures were conducted in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments. The study protocol was approved by the Vinmec International Hospital Medical Ethics Committee (approval number 64/202/QD-VMEC).

2.2. Methodology

2.2.1. Flow Cytometry

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were isolated and processed as previously described [

14]. Leukocyte subtypes were identified using the IVD BD FACSuite clinical application kit. Cell staining was performed within 24 h of collection, with analysis conducted within 1 h post-staining, adhering to previously established protocols [

14].

2.2.2. Cytokine Analysis

Plasma samples were stored at -80°C until analysis. Cytokine levels were quantified using the Human ProcartaPlex Mix&Match 26-plex kit and the ProcartaPlex Human Basic kit (ThermoFisher Scientific, USA), following the manufacturer's instructions.

2.2.3. Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics for quantitative variables included means, standard deviations and 95% confidence intervals. The Shapiro-Wilk test was employed to assess the normality of distribution for all immune biomarkers. Due to heterogeneity in biomarker variance, the non-parametric Wilcoxon rank sum test was utilized to evaluate statistically significant differences between groups. All statistical analyses were performed using RStudio software, with a significance level of α = 0.05 maintained throughout the study. This methodological approach ensures a robust statistical framework, accounting for non-normal distribution of biomarkers and employing appropriate non-parametric tests to accurately determine statistically significant alterations.

3. Results

3.1. Lymphocyte Populations in Peripheral Blood

A comparative analysis of lymphocyte populations between CRC patients and healthy control subjects is shown in

Table 1. Several salient observations emerge from these data: (1) All evaluated T cell subsets, including CD3+, CD4+, and CD8+ populations, exhibit statistically significant reductions in CRC patients (p<0.001 for all comparisons). This observation suggests a comprehensive suppression of T cell-mediated immunity in the context of CRC. (2) CD19+ B lymphocytes are similarly diminished in CRC patients, with statistical significance (p=0.006). (3) Although natural killer (NK) cell (CD56+) counts appear reduced in CRC patients, this difference does not reach statistical significance (p=0.3).

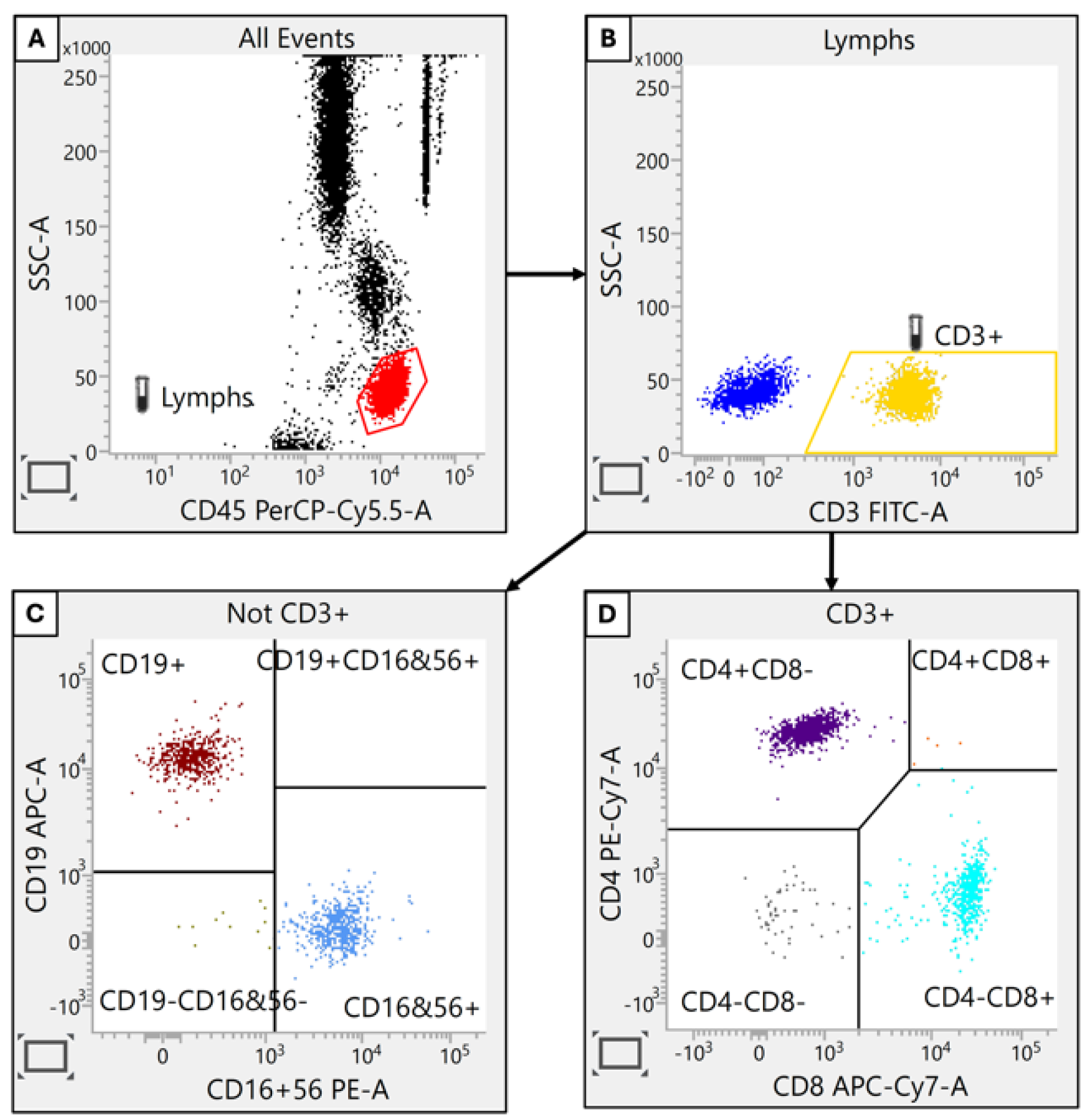

Figure 1.

Identification of Lymphocyte Subpopulations. Lymphocyte populations were distinguished based on their combined fluorescence intensity for CD45 and side scatter (SSC) properties. Subsequent gating defined T cells (CD3+), helper T cells (CD4+), cytotoxic T cells (CD8+), B cells (CD19+) and natural killer (NK) cells (CD56+).

Figure 1.

Identification of Lymphocyte Subpopulations. Lymphocyte populations were distinguished based on their combined fluorescence intensity for CD45 and side scatter (SSC) properties. Subsequent gating defined T cells (CD3+), helper T cells (CD4+), cytotoxic T cells (CD8+), B cells (CD19+) and natural killer (NK) cells (CD56+).

These findings collectively suggest that CRC is associated with significant alterations in immune system composition, particularly affecting T and B lymphocyte populations. Such immunological insights may prove invaluable for elucidating disease mechanisms and informing the development of novel immunotherapeutic approaches for CRC management.

3.2. Lymphocyte Subsets

We next analyzed functional subpopulations in these three major immune cell populations (B cells, T cells and NK cells). Our hypothese was that there exists variations in CRC patients compared to healthy people, which could provide new indicators of immune changes. The B cell component was gated and their subpopulations were evaluated (

Table 2).

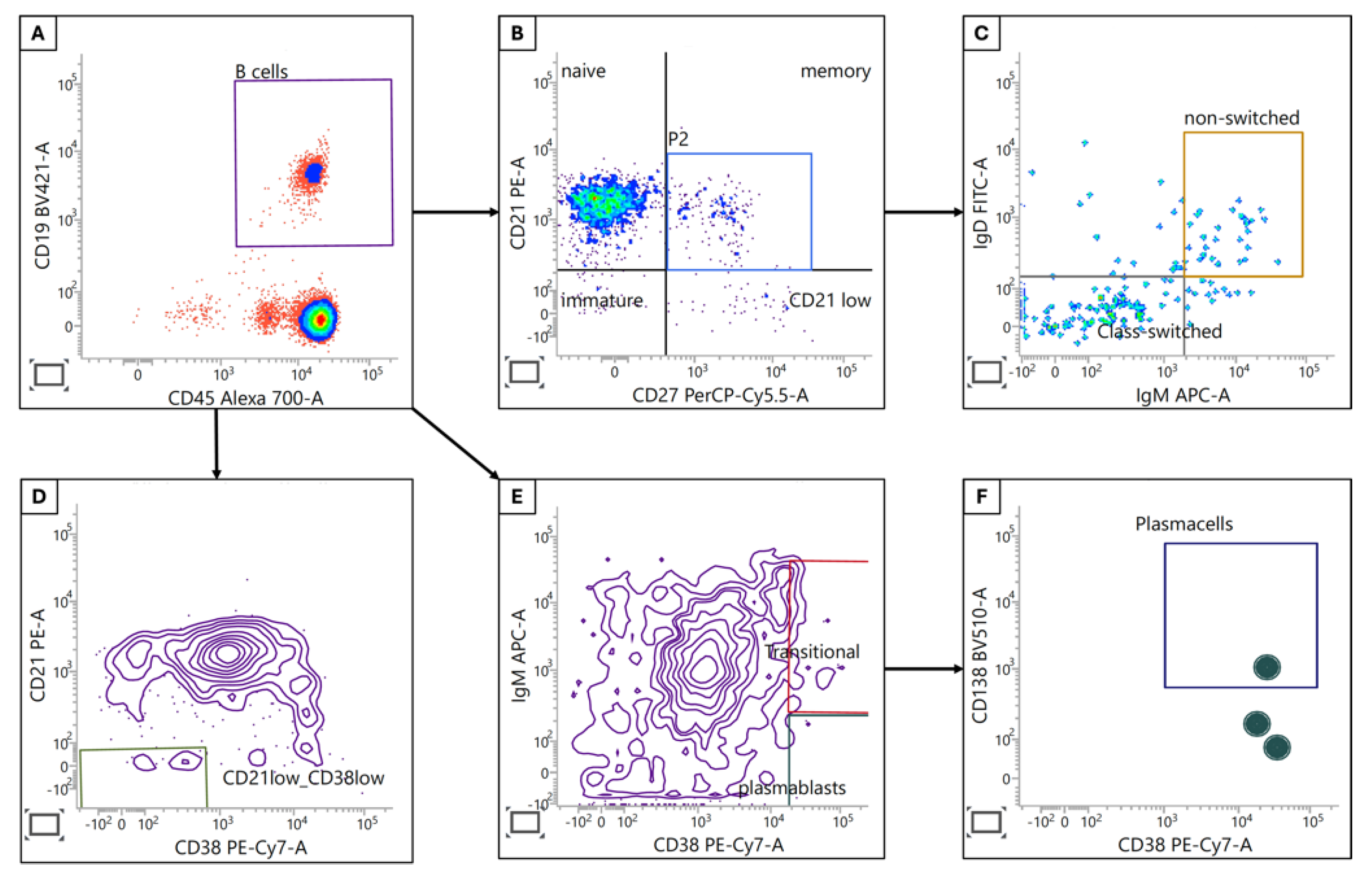

3.2.1. B Cells (Figure 2)

This approach reveals significant alterations in B cell subpopulations among CRC patients compared to healthy controls. Specifically, three B cell subsets demonstrated elevated proportions in CRC patients: CD21low, transitional (IgM+, CD38+) and class-switched (IgD-IgM-) cells. Conversely, two subpopulations exhibited marked reductions: naive (CD21+CD27-) and memory (CD21+CD27+) B cells.

The observed increase in CD21low, transitional, and class-switched B cells may be indicative of an augmented humoral immune response aimed at combating neoplastic cells. This shift could represent a compensatory mechanism within the adaptive immune system to counteract tumor growth. Conversely, the significant decline in naive and memory B cell populations suggests a potential compromise in immune system functionality. This reduction may be attributed to prolonged immune activation and subsequent exhaustion in the face of chronic tumor antigen exposure.

Figure 2.

B cell subpopulations. (A) B cells were identified by CD45 and CD19 expression. (B) Immature, naive, memory and CD21low B cells were identified using CD21/CD27 subgating. (C) Class-switched and non-switched memory B cells were separated by IgM and IgD expression. (D) Activated CD21low CD38low B cells were identified by using CD21 and CD38 staining from the B cell gate. (E) CD38+ transitional B cells and plasmablasts in the B cell population were discriminated by expression of IgM whereas plasma cells (CD138+IgM-) were identified by further subgating from plasmablasts (F).

Figure 2.

B cell subpopulations. (A) B cells were identified by CD45 and CD19 expression. (B) Immature, naive, memory and CD21low B cells were identified using CD21/CD27 subgating. (C) Class-switched and non-switched memory B cells were separated by IgM and IgD expression. (D) Activated CD21low CD38low B cells were identified by using CD21 and CD38 staining from the B cell gate. (E) CD38+ transitional B cells and plasmablasts in the B cell population were discriminated by expression of IgM whereas plasma cells (CD138+IgM-) were identified by further subgating from plasmablasts (F).

These findings collectively point to a complex remodeling of the B cell compartment in CRC patients. While some changes may reflect attempts at enhanced anti-tumor immunity, others suggest a degree of immune dysregulation or exhaustion. Further investigation into the functional implications of these alterations is warranted to elucidate their role in CRC pathogenesis and potential therapeutic interventions.

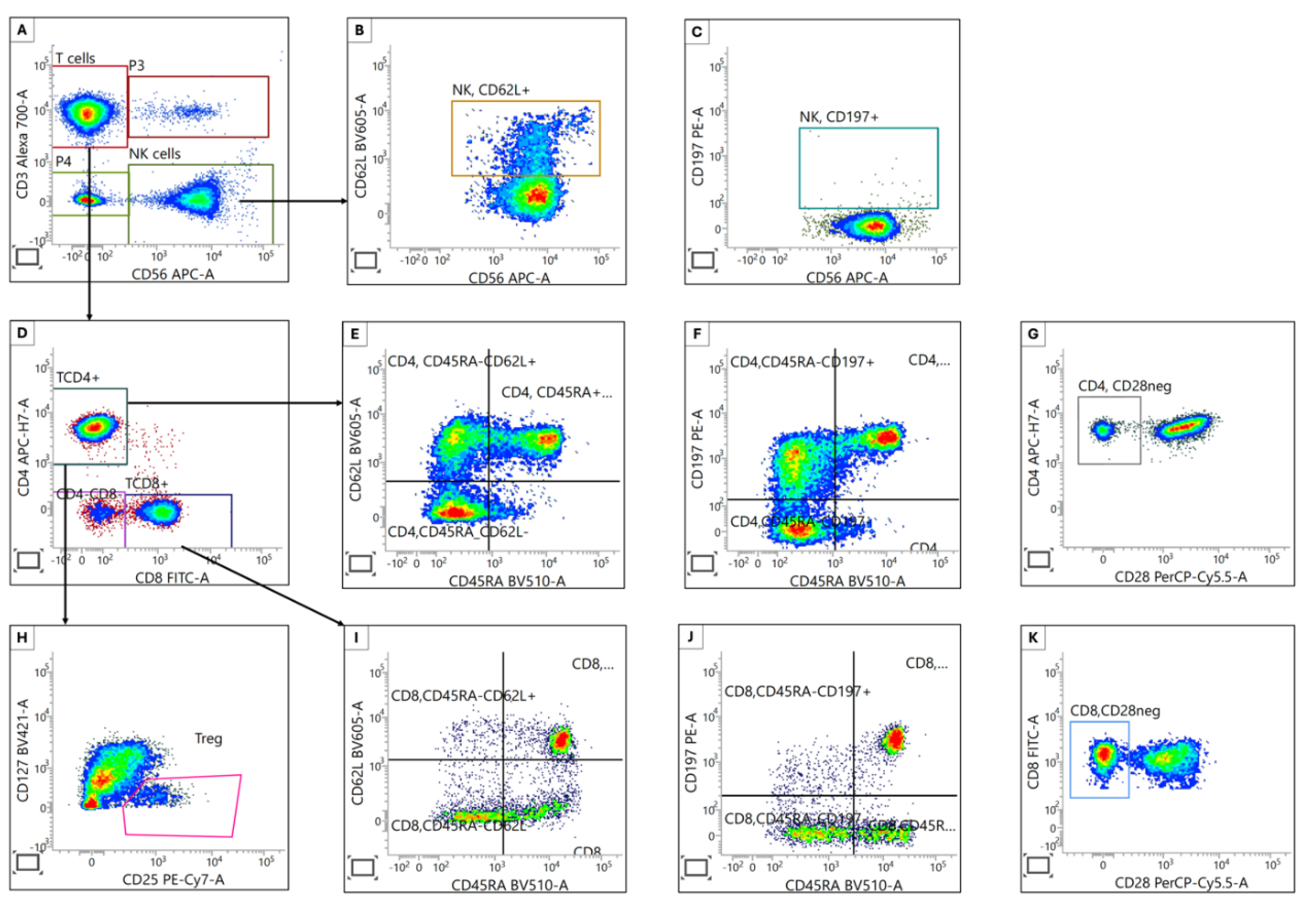

3.2.2. T and NK Cells

T and NK cells are critical components of the immune response against cancer, so we expanded our analyses to characterize a variety of T and NK cell subpopulations (

Table 3), and several changes were observed in CRC patients compared to healthy subjects.

CD4-CD8- T cells, known for their dual role in immune regulation and tumor surveillance, are significantly reduced in CRC patients (p<0.001). This subset has been reported to mediate antigen-specific cytotoxicity against effector T cells and produce cytotoxic molecules such as IFN-γ, TNF-α, granzymes and perforin. The reduction reported here suggests potential immunosuppression in CRC patients [

15,

16].

Among CD4+ T cell subsets, only the CD45RA-CD62L- effector population shows a significant increase in CRC patients (p=0.028). Other CD4+ subpopulations demonstrate no statistically significant differences. However, CD8+ T cell subsets exhibit more pronounced alterations. For example, in CRC patients, there is an increased proportion of CD28- (p<0.001), CD45RA-CD62L- (effector) (p=0.01), CD45RA-CD197- (effector) (p=0.002), CD45RA+CD62L- (effector memory) (p=0.001) and CD45RA+CD197- (effector memory) (p=0.044). In contrast, in these same CRC patients, we report reduced proportions of CD45RA+CD62L+ (naive) (p<0.001) and CD45RA+CD197+ (naive) (p<0.001). These shifts suggest a skewing towards effector and effector memory phenotypes at the expense of naive CD8+ T cells. NK cells also demonstrate alterations, with a significantly lower proportion of CD62L+ cells in CRC patients (p=0.003). This may indicate changes in NK cell activation or trafficking patterns.

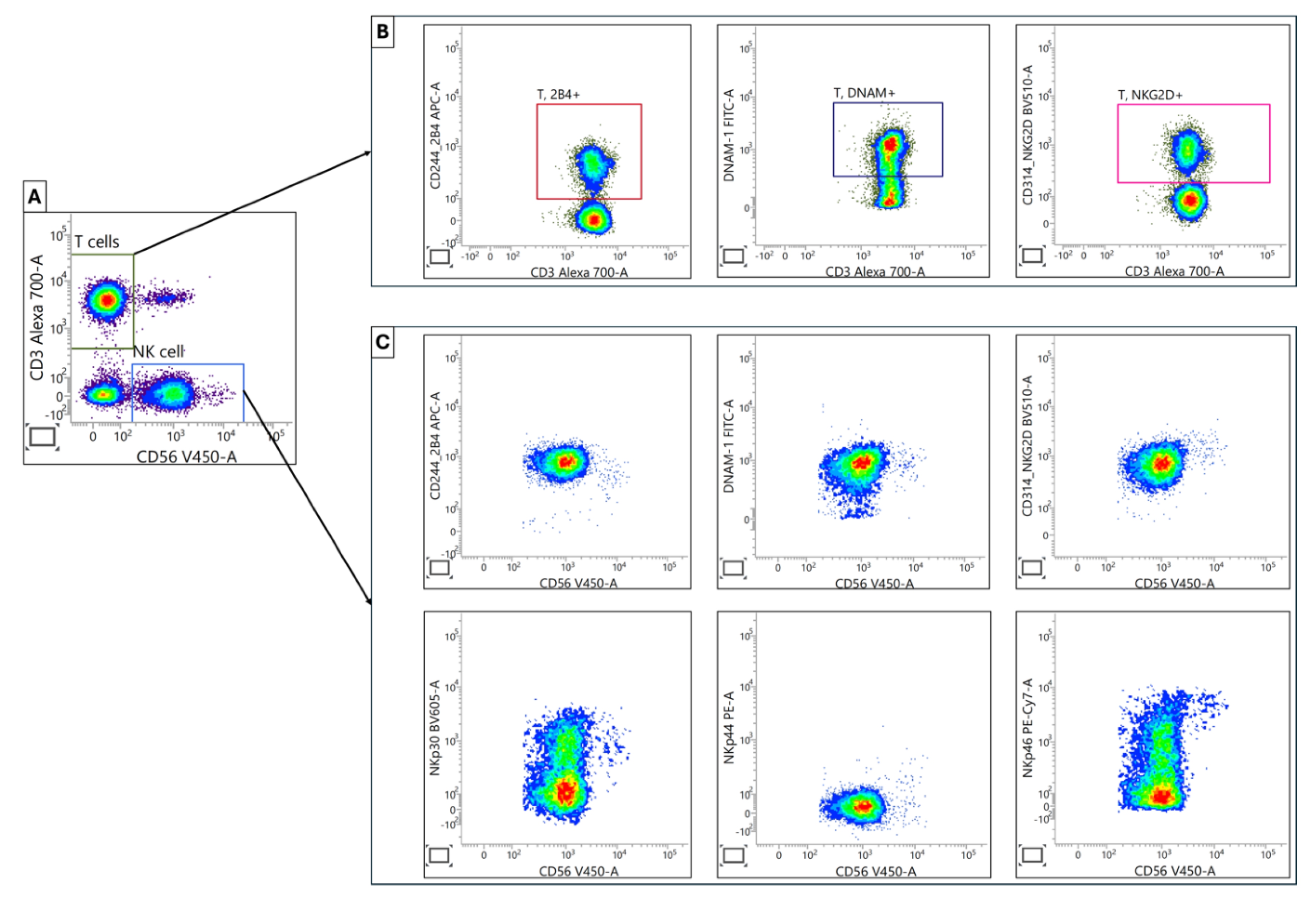

Figure 3.

Characterization of T and NK Cell Subpopulations. (A) T and NK cells were separated by using fluorescently labeled anti-CD3 and anti-CD56 antibodies. (B) & (C) Homing marker expression (CD62L and CD197) on NK cells was assessed. (D) Helper and cytotoxic T cells were identified using specific anti-CD4 and anti-CD8 antibodies. (E, F, G, and H) Helper T cell subpopulations were further categorized as regulatory T (CD25+CD127low), naive (CD45RA+CD62L+ or CD45RA+CD197+), memory (CD45RA-CD62L+ or CD45RA-CD197+) and aged-related (CD28-) cells, respectively. (I, J, and K) Cytotoxic T cell subpopulations included naive (CD45RA+CD62L+ or CD45RA+CD197+), memory (CD45RA-CD62L+ or CD45RA-CD197+) and aged-related (CD28-) cells, respectively.

Figure 3.

Characterization of T and NK Cell Subpopulations. (A) T and NK cells were separated by using fluorescently labeled anti-CD3 and anti-CD56 antibodies. (B) & (C) Homing marker expression (CD62L and CD197) on NK cells was assessed. (D) Helper and cytotoxic T cells were identified using specific anti-CD4 and anti-CD8 antibodies. (E, F, G, and H) Helper T cell subpopulations were further categorized as regulatory T (CD25+CD127low), naive (CD45RA+CD62L+ or CD45RA+CD197+), memory (CD45RA-CD62L+ or CD45RA-CD197+) and aged-related (CD28-) cells, respectively. (I, J, and K) Cytotoxic T cell subpopulations included naive (CD45RA+CD62L+ or CD45RA+CD197+), memory (CD45RA-CD62L+ or CD45RA-CD197+) and aged-related (CD28-) cells, respectively.

These findings collectively point to substantial remodeling of T and NK cell compartments in CRC, potentially reflecting ongoing anti-tumor responses and/or immune dysregulation.

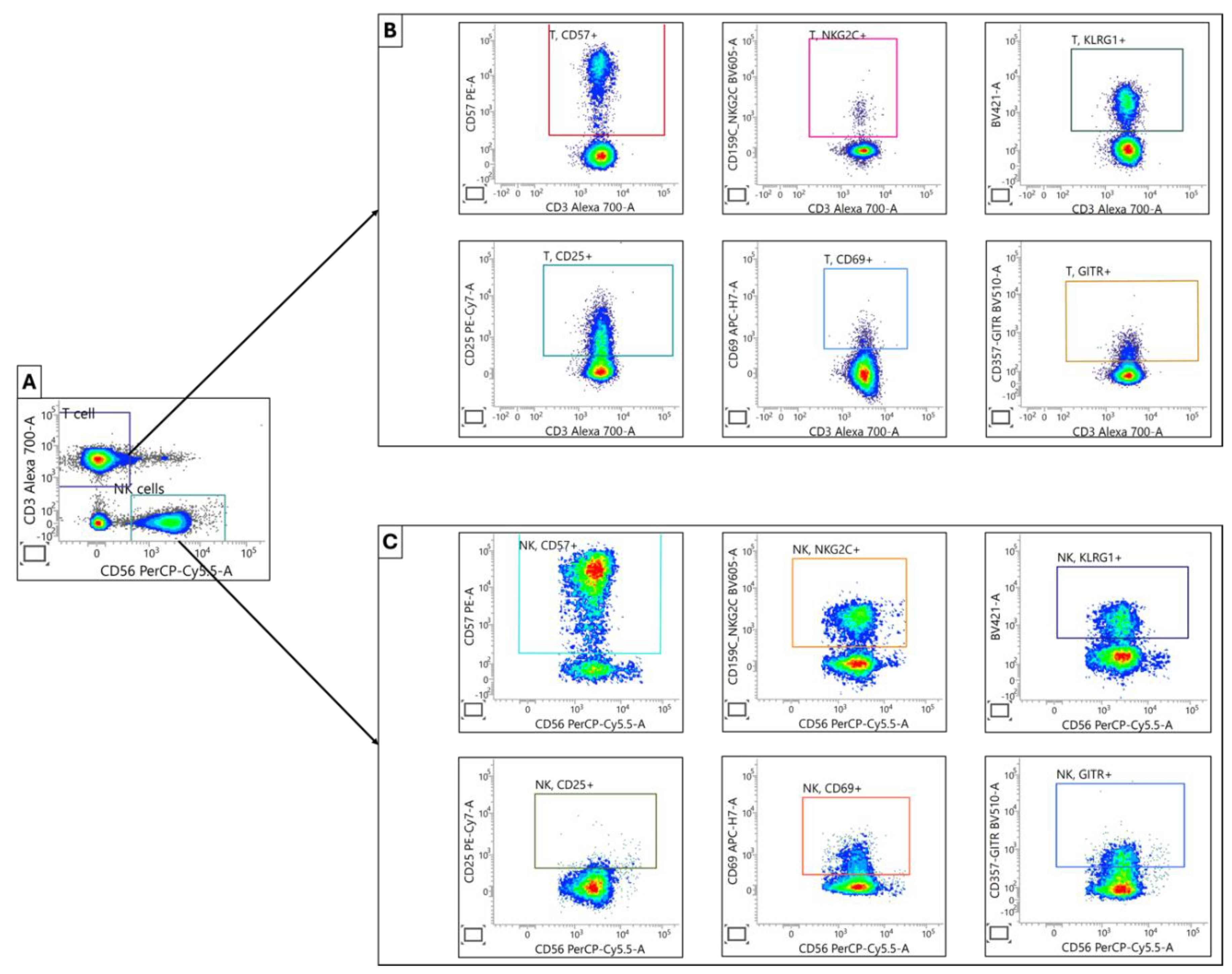

3.2.3. T and NK Cell Activation and Maturation

Analysis of T and NK cell activation and maturation markers in CRC patients and healthy controls revealed distinct patterns of immune cell modulation (

Table 4):

Among T cell subpopulations, only CD69+ T cells showed a significant increase in CRC patients (p<0.001). Other T cell markers (CD25, CD57, GITR, KLRG1, NKG2C) demonstrated no statistically significant differences between the two groups. In contrast, four out of six NK cell markers exhibited significant elevations in CRC patients: CD25+ (p=0.004), CD57+ (p<0.001), CD69+ (p<0.001) and KLRG1+ (p=0.026). GITR+ and NKG2C+ NK cells showed no significant differences between CRC patients and healthy subjects. It is important to note that no maturation or activation markers were reduced in CRC patients compared to healthy subjects. This finding suggests an immune landscape that tends towards enhanced immune activation rather than suppression.

Collectively, these findings demonstrate a more pronounced activation state of NK cells in CRC patients, as evidenced by the increased expression of multiple activation and maturation markers. In contrast, T cells display a more limited alteration, with only CD69 showing significant upregulation.

This table presents the mean ± SD (% ) and 95% CI data for key markers associated with activation and maturation of T and NK cells in the peripheral blood.

Figure 4.

Characterization of T and NK Cell Maturation and Activation Profiles. (A) Initial separation of T and NK cell populations was achieved by using anti-CD3 and anti-CD56 antibodies. (B)&(C) Subsequently identified T and NK cell populations were further analyzed based on specific surface markers associated with cellular maturation (CD57, NKG2C, KLRG1) and activation status (CD25, CD69, GITR).

Figure 4.

Characterization of T and NK Cell Maturation and Activation Profiles. (A) Initial separation of T and NK cell populations was achieved by using anti-CD3 and anti-CD56 antibodies. (B)&(C) Subsequently identified T and NK cell populations were further analyzed based on specific surface markers associated with cellular maturation (CD57, NKG2C, KLRG1) and activation status (CD25, CD69, GITR).

3.2.4. NK Cell Activating Receptors

An analysis of activating receptor expression on natural killer (NK) cells in colorectal cancer (CRC) patients compared to healthy subjects reveals a complex modulation of the NK cell receptor repertoire (

Table 5),

We found a significant upregulation for NKp44 cells in CRC patients (p=0.015), which suggests potential NK cell activation in the context of CRC. However, for the CD244 (2B4) subpopulation, there was a significant downregulation in CRC patients (p=0.049). This reduction may indicate altered NK cell functionality or responsiveness. Similarly, CD314 (NKG2D) cells were significantly lower in CRC patients (p=0.003). Given NKG2D's role in tumor immunosurveillance, this reduction could have implications for anti-tumor immunity. There were no statistically significant differences observed between CRC patients and healthy subjects in the remaining three subpopulations, DNAM-1, NKp30, and NKp46. These findings demonstrate a selective modulation of NK cell activating receptors in CRC patients. The divergent regulation of these receptors, with NKp44 cells increased while CD244 and CD314 decreased, which characterizes a complex remodeling of NK cell phenotypes and potential function in the context of CRC. These results also underscore the importance of comprehensively assessing multiple NK cell receptors to gain a nuanced understanding of NK cell status in cancer patients as individual receptors appear to be differentially regulated.

This table presents the mean ± standard deviation (MFI), and 95% CI data for a panel of activating receptors expressed by T and NK cells in 30 CRC patients and 40 healthy individuals. (The measurement unit of activated receptors is Mean Fluorescence Intencity, MFI)

Figure 5.

Characterization of Activating Receptors in T and NK Cell Populations. (A) Initial separation of NK and T cell populations was accomplished by using antibodies against CD3 and CD56. (B) Within the T cell population, activating receptors 2B4, DNA, and NKG2D were determined and presented as the percent positive cells. (C) For NK cells, activating receptors 2B4, DNAM, NKG2D, NKP30, NKP44 and NKP46 was quantified using the median fluorescence intensity (MFI) parameter.

Figure 5.

Characterization of Activating Receptors in T and NK Cell Populations. (A) Initial separation of NK and T cell populations was accomplished by using antibodies against CD3 and CD56. (B) Within the T cell population, activating receptors 2B4, DNA, and NKG2D were determined and presented as the percent positive cells. (C) For NK cells, activating receptors 2B4, DNAM, NKG2D, NKP30, NKP44 and NKP46 was quantified using the median fluorescence intensity (MFI) parameter.

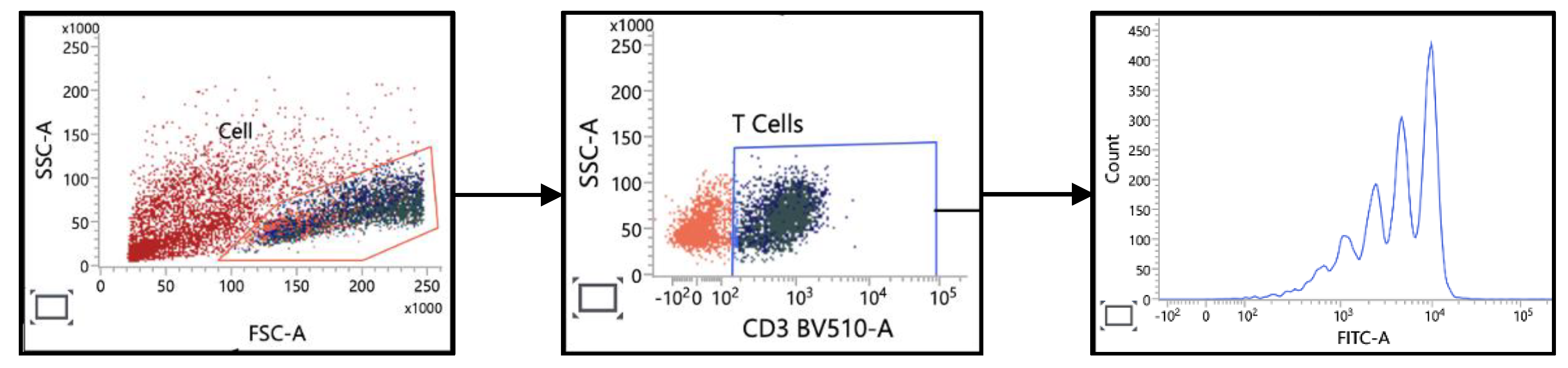

3.2.5. T Cell Proliferation Analysis

To assess the functional capacity of immune cells beyond mere enumeration, we examined the proliferative potential of T cells from colorectal cancer (CRC) patients and healthy individuals. Proliferation was assessed by analyzing the dilution of CFSE in CFSE-labeled T cells. Three key metrics were evaluated: Percent Divided, Division Index and Proliferation Index.

No significant differences in T cell proliferation between CRC patients and healthy individuals were detected across all three of proliferation metrics (

Table 6). These findings suggest that the proliferative capacity of T cells in CRC patients is largely preserved and comparable to that of healthy individuals. However, it is important to note that while proliferative capacity is maintained, this does not necessarily reflect the overall functional state of T cells in the tumor microenvironment.

Figure 6.

Characterization of T Cell Proliferation. PBMCs were labeled with CFSE and then stimulated with anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 antibodies. T cell responses were analysed based on forward scatter (FSC) and side scatter (SSC) after gating on the CD3 marker.

Figure 6.

Characterization of T Cell Proliferation. PBMCs were labeled with CFSE and then stimulated with anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 antibodies. T cell responses were analysed based on forward scatter (FSC) and side scatter (SSC) after gating on the CD3 marker.

This table presents the data from experiments analyzing the proliferative capacity of T cells in peripheral blood of cancer patients and healthy subjects. The table displays mean values (mean ± SD % and 95% CI) of various proliferation indices measured in this cell population.

3.2.6. NK Cell Cytotoxicity Analysis

We evaluated the cytotoxic capacity of NK cells from CRC patients and healthy subjects using a standard cytotoxicity assay. PBMCs served as effector cells, while K562 erythroleukemia cells were used as target cells. Cytotoxicity was assessed at four different effector-to-target (E:T) ratios: 5:1, 10:1, 20:1, and 40:1. The percentage of dead K562 cells was quantified for each condition. We found dose-dependent cytotoxicity in both CRC patients and healthy subjects, indicating a preserved dose-response relationship in NK cell function. Importantly, however, enhanced cytotoxicity in CRC patients was detected at the lower E:T ratios of 5:1 (p=0.007), 10:1 (p=0.021) and 20:1 (p=0.042). Convergence at high E:T ratio of 40:1 revealed no statistically significant difference between CRC patients (70.5%) and healthy subjects (65.1%) (p=0.2).

These results suggest that NK cells from CRC patients exhibit enhanced cytotoxic potential, particularly at lower E:T ratios. This heightened cytotoxicity may reflect an activated state of NK cells in CRC patients, possibly due to ongoing immune responses against the tumor. These findings highlight the importance of assessing NK cell function across a range of E:T ratios to fully characterize potential differences between patient and healthy populations. The enhanced NK cell cytotoxicity in CRC patients at lower E:T ratios may have implications for understanding anti-tumor immune responses and could be relevant for immunotherapeutic strategies in CRC.

The cytotoxicity percentage was computed using the formula outlined in the methods section, demonstrating the capacity of the NK cells within PBMCs to kill K562 cells.

3.3. Cytokine Profile Analysis

We conducted a comprehensive analysis of 15 cytokines in 30 CRC patients and 40 healthy subjects using the Human ProcartaPlex Mix & Match 26-plex kit and ProcartaPlex Human Basic kit (ThermoFisher Scientific, US;

Table 8). This analysis provides insight into the inflammatory and immunoregulatory milieu associated with CRC.

A number of cytokines are significantly elevated in CRC patients, including IL-1RA (p=0.023), IL-7 (p<0.001), IP-10/CXCL10 (p=0.002), PDGF-BB (p=0.037) and VEGF-A (p=0.001). No differences were detected in any of the other cytokines. We also measured 12 other cytokines including FGF-2, G-CSF/CSF-3, IFNγ, IL-1β, IL-2, IL-4, IL-5, IL-6, IL-8, IL-9, IL-13, IL-17A/CTLA-8. These cytokines were only detectable in 1-2 patients so that amounts are not reported here.

This cytokine profile suggests a complex immunological landscape in CRC patients. The elevated levels of pro-inflammatory (IL-7, IP-10) and angiogenic factors (VEGF-A) indicate an ongoing inflammatory process potentially aimed at tumor cell elimination. A noteworthy finding was the marked elevation of IL-1RA in CRC patients. The mean IL-1RA concentration in CRC patients (470 pg/mL) was approximately five-fold higher than that observed in healthy subjects (91 pg/mL), with this difference reaching statistical significance (p=0.023). The substantial increase in IL-1RA levels in CRC patients suggests a robust activation of anti-inflammatory mechanisms, likely in response to ongoing inflammatory processes associated with the tumor microenvironment.

This table presents the mean ± SD, (95% CI) values of various cytokines measured in the plasma of 30 CRC patients and 40 healthy donors. (The cytokines in the green rows are pro-inflammatory, pink are anti-inflammatory, blue are growth factors and yellow are angiogenesis).

It should be noted that IL-1RA exhibited a bimodal distribution in CRC patients, with approximately 50% showing markedly elevated levels while the remainder had undetectable levels (0 pg/mL). Multivariate analysis revealed that gender was the only significant factor associated with this dichotomy (

Table 9).

4. Discussion

4.1. Lymphocyte Populations in Peripheral Blood

The development of cancer is hypothesized to result from failures in the body's immune surveillance mechanisms. Both innate and adaptive immune components, particularly NK cells, T cells and B cells, may exhibit impaired functionality, potentially leading to uncontrolled proliferation of malignant cells. While previous research has explored the dual function of certain immune cells in either promoting or suppressing anti-tumor responses within the tumor microenvironment [

17], our study represents the first comprehensive analysis of nearly all immune cell subpopulations in the peripheral blood of colorectal cancer patients. This analysis enables us to evaluate their potential roles in the immune response. Dysregulation of these immune cells can significantly affect the balance between tumor progression and immune-mediated tumor suppression, highlighting the importance of understanding immune system dynamics in cancer development and progression.

4.1.1. Significant Decline in T, B, and NK Cell Populations in the Peripheral Blood of CRC Patients

Our investigation revealed a marked reduction in the absolute number of total lymphocytes and their subpopulations, including CD4+ T helper lymphocytes, CD8+ T cytotoxic lymphocytes, and CD19+ B lymphocytes in colorectal cancer (CRC) patients. These findings align with several previous studies [

18,

19].

In the context of anti-cancer immunity, CD8+ T lymphocytes serve as protective immune cells capable of directly targeting and eliminating tumor cells [

20]. Concurrently, CD4+ T lymphocytes function to stimulate B cells in producing antibodies against cancer antigens while secreting cytokines that activate phagocytes for tumor cell destruction. Additionally, CD4+ T cells play a crucial role in maintaining CD8+ T cell immune responses [

21]. The reduction in peripheral T and B cell numbers in CRC patients may be attributed to two primary factors: (1) the migration of these immune cells to tumor tissues, and (2) the immunosuppressive effects exerted by cancer cells, as highlighted below.

Previous research has indicated that the monocyte-to-lymphocyte ratio serves as a prognostic factor in peripheral whole blood samples of patients with colorectal cancer [

22], multiple myeloma [

23] and ovarian cancer [

24]. However, our study did not reveal such a correlation, perhaps due to the limited sample size.

Our data are consistent with earlier data that showed B cell counts in CRC patients to be reduced [

25], although some studies have observed elevated B cell levels in the serum of colon cancer patients compared to control groups [

26]. B cells exhibit both inhibitory and supportive influences on cancer cells. Their inhibitory role primarily involves the production of antibodies against cancer antigens and the activation of phagocytes, including macrophages and neutrophils, through proinflammatory cytokines [

27,

28]. Conversely, within the tumor microenvironment, pro-tumoral activity is predominantly mediated by regulatory B cells (Bregs) [

29]. Our study demonstrates a significant decrease in peripheral B cells in CRC patients compared to healthy individuals, suggesting potential inhibition by cancer cells, as noted in previous research. Several hypotheses may explain the decrease in B cell numbers in cancer patients: (1) Tumor-induced immunosuppression: Cancer cells can create an immunosuppressive environment by secreting factors that impair immune cell function and survival, including B cells. These factors may compromise cytokines, enzymes and metabolites that directly or indirectly inhibit B cell development, proliferation and survival [

30]. (2) B cell migration: The tendency for B cells to migrate to the tumor microenvironment may contribute to reduced B cell levels in peripheral blood [

31,

32]. (3) Aging and malnutrition: These factors are also potential causes of B cell decline in CRC patients [

33].

Regarding NK cells, studies have reported both decreased [

34,

35] and increased [

36] peripheral NK cell numbers. Some research even suggests that the percentage of NK cells in peripheral blood could serve as an independent prognostic indicator in CRC [

37]. Our study found no significant difference in peripheral NK cell numbers between CRC patients and healthy individuals, highlighting the variability in NK cell alterations in CRC. However, what’s new in our study is that we report statistically greater NK cytotoxic activity, an important finding that is further discussed below in the discussion of NK cell cytotoxicity.

Inflammation plays a crucial role in cancer progression and peripheral monocyte count has been correlated with prognosis in CRC patients [

38]. This hypothesis reflects the density of tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) in the cancer microenvironment [39-41]. Given that our study found no difference in monocyte numbers between CRC patients and healthy individuals, this may suggest a generally favorable prognosis for this patient cohort.

4.2. Gated Proportions of B Cell Subpopulations

4.2.1. Increased Proportions of CD21low, Transitional and Class-switched B Cells

The elevated frequencies of CD21low B cells, transitional B cells and class-switched B cells observed in colorectal cancer (CRC) patients compared to healthy individuals reflect the intricate interactions between the tumor and the host's immune system.

CD21low B Cells

CD21low B cells are polyclonal, unmutated IgM+IgD+ B cells with a distinct gene expression profile that differentiates them from conventional naive B cells [

42]. These cells exhibit reduced B cell receptor (BCR) signaling capacity and are frequently associated with chronic inflammation and autoimmunity [

43]. The observed increase in CD21low B cells in CRC patients may indicate uncontrolled chronic inflammation. Additionally, tumor-derived factors or tumor-induced cytokines, such as IL-6 and TNF-α, may contribute significantly to the phenomenon of inflamm-aging in elderly patients [

44], potentially leading to CD21 upregulation.

Transitional B Cells

Transitional B cells (TrB cells) are bone marrow-derived, immature B cells considered precursors to mature B cells [

45,

46]. The increased proportion of transitional B cells in CRC patients may be attributed to several factors: (1) Tumor-induced inflammation may disrupt normal B cell development, resulting in the premature release of transitional B cells from the bone marrow [

47]. (2) Elevated levels of cytokines such as B cell activating factor (BAFF), often observed in cancer, may promote the survival and accumulation of transitional B cells [

48,

49]. (3) Some transitional B cells may possess regulatory functions (Bregs) that suppress anti-tumor immune responses, potentially exploited by tumors for immune evasion [

50].

Class-switched B Cells

Class-switched B cells have undergone class-switch recombination (CSR) to alter their antibody isotype from IgM to IgG, IgA or IgE. The increased proportion of these cells in CRC patients may be explained by multiple possibilities: (1) Chronic tumor-associated inflammation providing a cytokine-rich milieu (e.g., IL-4, IL-5, TGF-β) that promotes CSR [

51]. (2) Persistent antigenic stimulation from tumor-associated antigens driving B cell activation and CSR [

52]. (3) Production of tumor-specific antibodies by some class-switched B cells, reflecting an ongoing anti-tumor humoral response [

53]. (4) Potential production of ineffective antibodies or those promoting tumor growth (e.g., by activating complement without causing cell death, leading to inflammation) [

54,

55].

4.2.2. T Cells and NK Cells

A notable observation regarding T cell subpopulations is the significant decrease in CD4-CD8- T cells in colorectal cancer (CRC) patients. These cells typically comprise 1-3% of mature peripheral CD3+ T cells in both human and mouse models [

56,

57]. While the exact cause of this decrease in CRC patients remains under investigation, several potential contributing factors have been identified. CD4-CD8- T cells have been shown to not only exist in peripheral blood but also infiltrate solid tumors [58-61]. This migration to the tumor microenvironment may contribute to the reduced proportion of these cells in peripheral blood compared to healthy individuals.

4.2.3. CD8+ and CD4+ T Cells

Preclinical and clinical studies have demonstrated the ability to induce functional memory T cells against cancer and the importance of such responses in therapeutic immunity [62-64]. However, the dynamic and heterogeneous nature of memory CD8+ T cell responses across host peripheral and lymphoid tissue compartments is only beginning to be explored [

65]. The present study reveals that T cell differentiation, particularly CD8+ T cells, is altered in CRC patients, leading to an increase in effector (CD45RA-CD62L- and CD45RA-CD197-) and effector memory (CD45RA+CD62L- and CD45RA+CD197-) CD8+ T cells, while reducing naive (CD45RA+CD62L+ and CD45RA+CD197+) CD8+ T cells. These results suggest a robust, long-standing anti-tumor enhancement of the immune system, which most likely is a positive indicator for CRC patients.

In addition to more CD8+ memory T cells, we also observed an increase in CD4+ (CD45RA-CD62L-) effector T cells. The ability of CD4+ effector cells to contribute to antitumor immunity independent of CD8+ T cells is increasingly recognized, though strategies to fully realize their potential remain undefined [66-69]. Some researchers have described a mechanism in which a small number of CD4+ T cells is sufficient to eliminate MHC-deficient tumors that cannot be directly targeted by CD8+ T cells [

70].

Compared to studies on autoimmune diseases, this change is similar to rheumatoid arthritis but not systemic lupus erythematosus [

71]. The increase in the proportion of effector T cells, including effector CD4+ cells, effector CD8+ cells, and effector CD8+ memory cells, further supports the immune escape theory of cancer pathology.

Naive T cells follow a restricted migratory pattern through blood, lymph nodes and efferent lymph due to their high expression of CD62L and CD197 and low expression of tissue-specific adhesion molecules and chemokine receptors [

72]. The decrease in naive T cells observed in our CRC patients is likely due to a combination of factors that impair the normal development and function of the immune system. One potential reason is that colorectal tumors constantly challenge the immune system. This chronic infiltration, activation and effector differentiation can lead to the depletion of the naive T cell pool, despite the presence of immunosuppressive mechanisms [

73].

4.2.4. CD62L+ NK Cells

CD62L (L-selectin) is a molecule that plays a crucial role in mediating lymphocyte homing to secondary lymphoid organs. NK cells expressing CD62L (CD62L+ NK cells) represent a multifunctional subset of NK cells that is associated with the extent of local immune responses to viral infections. These cells are capable of producing IFN-γ upon cytokine stimulation and often exhibit proliferation during viral infections as well as enhanced target cell killing capabilities [

74].

Recent studies have demonstrated that CD62L expression varies across different stages of human NK cell maturation, indicating its importance beyond leukocyte migration [

74]. The significant decline in CD62L+ NK cells observed in our study may be interpreted in two ways: (1) General immune cell depletion: This decrease may be part of a broader decline in immune cell populations, including the previously mentioned reduction in naive T cells. This general depletion could be attributed to the impact of cancer cells on the immune system. (2) Migration to the tumor microenvironment: Alternatively, the decrease in peripheral CD62L+ NK cells may result from their migration into the tumor microenvironment to perform cytotoxic functions against cancer cells.

These findings underscore the complex interplay between NK cell subsets and the tumor microenvironment in colorectal cancer patients. Further research is needed to elucidate the precise mechanisms underlying the observed changes in CD62L+ NK cell populations and their implications for anti-tumor immunity.

4.2.5. T and NK Cell Activation and Maturation

The elevated proportions of various markers on T cells and NK cells in colorectal cancer (CRC) patients compared to healthy subjects likely reflect the ongoing immune response against the tumor.

CD25, the α chain of the IL-2 receptor, exhibits increased expression on NK cells, suggesting enhanced activation and responsiveness to IL-2. This can augment NK cell proliferation and cytotoxicity [

75], potentially indicating ongoing stimulation by the tumor microenvironment [

76].

CD57, a marker of terminal differentiation in NK cells, is associated with highly cytotoxic cells that appear beneficial in several non-communicable diseases [

77]. Elevated frequencies of peripheral or tumor-associated CD57+ NK cells have been reported in cancer patients, consistent with enhanced tumor surveillance and cytotoxicity of this mature NK cell subset [

78]. Higher levels of CD57+ NK cells in cancer patients may indicate a more experienced or mature NK cell population, possibly due to chronic stimulation by tumor antigens.

CD69, an early activation marker, has recently been shown to regulate regulatory T (Treg) cell differentiation and the secretion of IFN-γ, IL-17 and IL-22. CD69 upregulation is observed after activation in most hematopoietic cells, indicating a general requirement for its regulatory effects [

79]. A study on melanoma patients demonstrated an inverse relationship between the rate of CD69+ NK cells development and patient survival time [

80], suggesting that an increase in CD69+ cells may be a poor prognostic factor. Our CRC patients exhibit significantly higher CD69+ levels than healthy individuals, which may also indicate a poor prognosis. However, this requires further validation through patient survival time monitoring, which was beyond the scope of our current study.

Killer cell lectin-like receptor G1 (KLRG1) is an immune checkpoint receptor expressed primarily on NK and T cell subsets and it was significantly elevated in our CRC patients. It regulates immune cell activation, proliferation and participates in cell-mediated immune responses [

81]. Recent advances have revealed KLRG1's important role in the pathogenesis and progression of autoimmune disorders, infectious diseases and malignancies, highlighting its potential as a promising immune cell marker for disease prediction, diagnosis and prognosis [

82,

83].

KLRG1 expression is increased in T cells of patients with solid tumors such as breast cancer and CRC compared to healthy individuals [84-87]. Research has demonstrated KLRG1's significant role in various tumor types, including solid and hematological malignancies [88-90]. In the tumor microenvironment, KLRG1 can inhibit anti-tumor immune responses and promote tumor escape [

91]. KLRG1 expression levels also significantly correlate with immunotherapy responses in patients with various diseases and may serve as a biomarker for tumor prognosis [

92,

93]. The increase in KLRG1 observed in our study aligns with these previous findings, suggesting that KLRG1 could be considered another biomarker for CRC in the Vietnamese population.

4.2.6. NK Cell Activating Receptors

Evidence suggests that NK cells require activation signals to recognize abnormal cells, such as those that are transformed or virally infected. Activating receptors include NKG2D, DNAM-1, 2B4 and several natural cytotoxicity receptors (NCRs) [

94]. The NCR family comprises NKp46, NKp44 and NKp30. While NKp46 and NKp30 are primarily expressed in resting cells, NKp44 is expressed only in activated cells. Early expression of p44 on NK cells may enhance target cell cytotoxicity and cytolysis, although p44-dependent target cell lysis accounts for only a small proportion of overall NK-induced target cell lysis (with the majority attributed to antibody-dependent cytotoxicity) [95, 96].

As shown in

Table 6, CRC patients exhibit significant changes in the ratios of p30, p44 and p46 markers compared to healthy individuals, with p30 and p46 reduced and p44 enhanced. This unique pattern warrants further investigation into its underlying causes.

The increased ratio of p44 on NK cells of CRC patients is consistent with its expression on activated NK cells, potentially indicating an attempt to augment the anti-cancer response. However, it is important to note that this does not necessarily correlate with improved anti-tumor efficacy. The depletion of p30 and p46 can be explained by two primary factors: (1) Chronic stimulation and exhaustion: The persistent attack against tumor cells in the CRC microenvironment may lead to chronic activation and exhaustion of NK cells, reflected in downregulation of activation receptors such as NKp30 [

97]. (2) Inhibitory microenvironment: Tumors can create an immunosuppressive microenvironment that includes factors such as TGF-β and IL-10. Both of these proteins can negatively affect NK cell function and potentially downregulate activating receptors such as NKp30 and NKp46 [

98].

4.2.7. T Cell Proliferation

Studies of T cell proliferation in CRC have demonstrated increased proliferative capacity in the tumor microenvironment, but these investigations have not addressed T cells in the peripheral blood [

99,

100]. Our study examined T cell proliferation (expressed through proliferation indexes: percent divided, division index and proliferation index) in the peripheral blood of CRC patients. No significant difference were detected when compared to healthy individuals. Several potential explanations for this observation include: (1) The proliferation indexes may not be sufficiently sensitive to detect differences in response to the specific antigens used in the assay. This technique employed general mitogens (CD3 and CD28) to stimulate proliferation, which may not be representative of the T cell response to tumor-specific antigens in CRC patients. (2) CRC is a heterogeneous disease with variations in tumor type, stage and immune microenvironment. This heterogeneity might obscure overall differences in T cell proliferation between patients when compared to a healthy control group. (3) The T cell proliferation indexes themselves may not be sensitive or specific enough to capture subtle differences in T cell responses, particularly in complex diseases like CRC.

4.2.8. NK Cell Cytotoxicity

A variety of methods are employed to assess natural killer (NK) cell cytotoxicity, including the chromium-51 (51Cr) release assay [

101], flow cytometry-based assays [

102,

103] and bioluminescence-based assays [

104]. For this study, we utilized a fluorescein-based method recommended by the supplier, which is considered a state-of-the-art approach for evaluating NK cell cytotoxicity.

Comparative analysis of peripheral blood mononuclear cell (PBMC) cytotoxicity against K562 cells at varying effector-to-target (E:T) ratios (

Table 8) revealed that both cancer patients and healthy individuals exhibited increased cytotoxicity with higher E:T ratios, as anticipated. However, cancer patients consistently demonstrated higher cytotoxicity percentages than healthy controls across all E:T ratios except 40:1. This elevated cytotoxicity in PBMCs derived from cancer patients substantiates an activated immune state in response to the malignancy, as suggested by previous research [105-107].

4.3. Cytokines

The inflammatory process plays a pivotal role in the development of colorectal cancer (CRC). Both pro- and anti-tumorigenic cytokines are implicated in malignant transformation, and the delicate balance between these factors is essential for maintaining homeostasis [

108]. Consequently, cytokine networks offer could valuable insights into the prognosis and pathogenesis of CRC and can facilitate cost-effective, non-invasive cancer detection. Numerous interleukins released by the immune system at various stages of CRC can serve as potential biomarkers [

109]. However, the role of cytokine networks in CRC diagnosis remains relatively unexplored. To address this knowledge gap, our study aimed to quantify 15 cytokines , including 10 pro-inflammatory cytokines, 2 anti-inflammatory cytokines and 3 angiogenesis & growth factors and identify those with diagnostic or prognostic utility. So, the subsequent discussion will focus on these 15 cytokines (

Table 9).

4.3.1. Pro-Inflammatory Cytokines

Among the pro-inflammatory cytokines, only interleukin-7 (IL-7) and interferon gamma-induced protein 10 (IP-10) were significantly elevated in CRC patients. These findings have significant implications. IL-7 is produced by non-hematopoietic cells and plays a crucial role in the adaptive immune response. Several studies have reported overexpression of IL-7 in solid tumors [110-113] and elevated serum levels in cancer patients [114-118]. Consistent with these findings, our study demonstrated significantly higher IL-7 levels in CRC patients compared to healthy controls [

119]. The significant of elevated IL-7 in CRC can could promote T cell survival and proliferation [

120], contribute to tumor growth and metastasis [

121] and also serve as a biomarker for CRC progression and prognosis [

122].

IP-10, a chemokine secreted by cells stimulated with type I and II interferons and lipopolysaccharide, has chemotactic effects on activated T cells [

123,

124]. In CRC, the chronic inflammatory tumor microenvironment leads to increased IP-10 production. The importance of IP-10 in CRC includes its involvement in angiogenesis and tumor cell migration, recruitment of immune cells to the tumor microenvironment and it potential prognostic value for CRC. The increased levels of IP-10 observed in our study align with previous research and may have practical implications for CRC prevention, diagnosis and treatment.

Additionally, we observed that the levels of IFN-γ and TNF-α, the two primary functional cytokines of NK cells [

125],did not increase despite significantly elevated NK activity in CRC patients. This suggests that the cytotoxic mechanism of NK cells in CRC is independent of serum IFN-γ and TNF-α levels. A previous study also demonstrated that the cytotoxic mechanism of NK cells in CRC is primarily mediated by lytic granules or by inducing death receptor-mediated apoptosis through the expression of Fas ligand or TRAIL [

126]. Therefore, it appears that NK cells in CRC, although exhibiting increased cytotoxic function, did not secrete IFN-γ and TNF-α as much as anticipated.

4.3.2. Anti-Inflammatory Cytokines

Among the anti-inflammatory cytokines evaluated, only interleukin-1 receptor antagonist (IL-1RA) showed a significant increase in colorectal cancer (CRC) patients. This finding corroborates previous research that reported significantly elevated serum IL-1RA levels in CRC patients compared to healthy controls [

127].

Notably, IL-1β was either undetectable or present at very low concentrations (0.75–1.05 pg/mL) in two patients. We hypothesize that the exceptionally high levels of IL-1RA may have completely neutralized IL-1β, rendering it unquantifiable by our methods. However, the precise role of IL-1RA in CRC pathogenesis remains to be elucidated.

A previous study reported a decreased IL-1RA/IL-6 ratio in CRC patients. However, we were unable to confirm this finding due to the low measurable IL-6 levels in our patient cohort (only 1 out of 30 patients). This discrepancy may be attributed to ethnic variations in CRC characteristics or differences in study populations.

These findings highlight the complex interplay of cytokines in CRC and underscore the need for further investigation into the role of anti-inflammatory mediators, particularly IL-1RA, in CRC progression and potential therapeutic interventions. Future studies should aim to elucidate the mechanisms underlying the elevated IL-1RA levels and their implications for CRC pathophysiology and treatment strategies.

4.3.3. Angiogenesis and Growth Factors

Both vascular endothelial growth factor-A (VEGF-A) and platelet-derived growth factor-BB (PDGF-BB) were elevated in our CRC patients. VEGF-A is a key regulator of angiogenesis while PDGF-BB is a growth factor and is also involved in angiogenesis and cell proliferation. Members of the VEGF family and their receptors have been recognized as crucial mediators of angiogenesis [

128]. Several studies have highlighted the roles of PDGF signaling in tumor angiogenesis, encompassing perivascular cell recruitment, induction of proangiogenic factors, endothelial cell proliferation and migration and promotion of lymphangiogenesis and subsequent lymphatic metastasis [129-131]. The importance of VEGF, PDGF, fibroblast growth factor (FGF) and transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β) in tumor angiogenesis, including colon carcinogenesis, has been extensively studied [132-134].

In general, these elevated factors (VEGF-A and PDGF-BB) contribute to tumor growth, angiogenesis and immune evasion in CRC. The elevated VEGF-A levels in CRC patients in our study may be attributed to several factors: (1) hypoxia in the tumor microenvironment, which stimulates VEGF-A production as described in previous studies [

135,

136]; (2) oncogenic mutations, such as in KRAS or TP53, which can lead to increased VEGF-A expression [

137,

138]; and (3) the crucial role of VEGF-A in tumor vascularization, supporting cancer growth and metastasis [

139].

The elevated PDGF-BB levels in our CRC patients can be explained by its role in promoting tumor angiogenesis and supporting blood vessel formation for tumor growth [

140,

141] as well as its stimulation of the proliferation of cancer-associated fibroblasts, thus contributing to tumor progression [

142].

4.3.4. Infrequently Detected Cytokines

Our study utilized a kit capable of measuring 27 distinct cytokines. While 15 cytokines were commonly detected in colorectal cancer (CRC) patients, the remaining 12 showed limited presence:

- Undetected in all healthy people and all CRC patients: FGF2, IL-4, IL-5, IL-13, IL-17A/CTLA8

- Detected in only 1-2 health subjects and 1-2 CRC patients: GM-CSF, IFN-γ, IL-1β, IL-2, IL-6, IL-8/CXCL8, IL-9

These findings suggest that including these 12 infrequently detected cytokines in routine cytokine profiles for CRC patients may be unnecessary. Their rare occurrence in both patient and healthy populations indicates limited diagnostic or prognostic value in the context of colorectal cancer.

As a brief summary of our key findings on the cytokine profile in CRC, we found that five cytokines (IL-7, IP-10, IL-1RA, PDGF-BB and VEGF-A) showed statistically significant increases in colorectal cancer (CRC) patients, suggesting their potential as biomarkers. However, their prognostic value for survival outcomes remains unexplored in our study, unlike some previous research [143-145]. We also found that ten cytokines (Eotaxin, G-CSF, IL-10, IL-12, IL-15, MCP-1, MIP-1α, MIP-1β, TNFα, RANTES) showed no significant difference between CRC patients and healthy subjects, indicating they may not play a crucial role in CRC pathogenesis. These data reveal a distinct systemic inflammatory profile in CRC patients that is characterized by elevated pro-inflammatory and angiogenic factors. The intricate interactions among these cytokines may influence tumor progression and modulate anti-tumor immune responses. Future research projects are needed to investigate the functional implications of these altered cytokine levels, evaluate their potential as diagnostic or prognostic biomarkers and explore their viability as therapeutic targets in CRC.

5. Conclusions

This study presents a comprehensive immunological profile of colorectal cancer (CRC) patients using multicolor flow cytometry. Our analysis comprehensively characterized three primary immune cell populations (T, B, and NK cells), including detailed examination of nine B cell subpopulations, 27 T cell subpopulations, and eight NK cell subpopulations. We additionally quantified 15 cytokines in the peripheral blood of CRC patients.

Key findings include:

Immune Cell Dynamics: We observed a generalized reduction in most leukocytes, concurrent with a significant increase in specific subpopulations. This pattern suggests a complex immune response potentially representing resistance mechanisms against cancer cell progression.

Natural Killer (NK) Cell Function: CRC patients demonstrated a statistically significant enhancement in NK cell cytotoxic capacity, suggesting potential immunotherapeutic implications ussing NK cells and improved treatment responsiveness.

Cytokine Landscape: The immunological microenvironment revealed marked elevations in five key proteins: two pro-inflammatory cytokines, one anti-inflammatory cytokine, and two factors associated with epithelial growth and angiogenesis. This profile indicates robust immunological activation characteristic of CRC pathogenesis.

Pathophysiological Markers: We documented a reduction across all major lymphoid lineages (B, T, and NK cells), accompanied by significant upregulation of five specific cytokines: IL-7, IP-10, IL-1RA, GF-BB, and VEGF-A.

These findings provide nuanced insights into the immunological complexities of CRC, identifying potential therapeutic targets and prognostic biomarkers. Our comprehensive immunological profiling advances understanding of CRC immunology, potentially facilitating more precise and personalized treatment strategies.

6. Limitations of Study

While this research provides valuable insights into the immune profiles of colorectal cancer (CRC) patients, some limitations should be considered when interpreting the results: (1) Patients were sampled only once upon admission, in the late stage 1 or stage 2 without follow-up sampling after treatment. This cross-sectional design, focusing on a single disease stage, limits our ability to assess dynamic changes in immune indices throughout the course of treatment and disease progression. (2) The study relied on peripheral blood samples rather than biopsies of cancerous tissue. While blood sampling provides a systemic view of immune status, it may not fully reflect the local immune environment within the tumor, potentially overlooking tissue-specific immune responses. (3) The sample size of thirty cancer patients is relatively small. This limitation may reduce the statistical power of our analyses and potentially limit the generalizability of our findings to the broader CRC patient population.

These limitations underscore the need for further research with larger, longitudinal sampling, and integration of tissue-specific analyses. Future studies addressing these limitations could provide a more comprehensive understanding of the immune dynamics in CRC and potentially inform more targeted therapeutic approaches.

Author Contributions

H.D.C. organized and drafted the entire manuscript. NMP and DNT contributed to participant recruitment and blood sample collection. NDT, MTH and LTH implemented measurement techniques in the laboratory and contributed to manuscript editing. HDC, HMD and NVH contributed to data analysis and drawing of graphs and figures. HDC, HMD, LKL and NKQ contributed to manuscript writing. HDC, NXH, HMD and KK contributed to manuscript organization, revision and editing.

Funding

This work has been made possible thanks to Seed Fund of VinUniversity, Hanoi, Vietnam. VinUniversity | Award Number: VUNI.2021.SG15 | Recipient: Chien Dinh Huynh.

Institutional Review Board Statement

All procedures performed in this study were approved by the Vinmec-VinUni Ethical Review Committee (ethics approval number: 64/202/QD-VMEC) and were in accordance with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments and comparable ethical standards.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our deepest gratitude to VinUniversity, the Vinmec Healthcare System, and Central Military Hospital 108 for their invaluable support and collaboration in the successful completion of this project. Their unwavering commitment and dedication were instrumental in advancing our research endeavors and contributing to the collective pursuit of knowledge. We are sincerely thankful for their support and partnership throughout this project.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, Bray F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021 May;71(3):209-249. doi: 10.3322/caac.21660. Epub 2021 Feb 4. PMID: 33538338.

- Gonzalez H, Hagerling C, Werb Z. Roles of the immune system in cancer: from tumor initiation to metastatic progression. Genes Dev. 2018 Oct 1;32(19-20):1267-1284. doi: 10.1101/gad.314617.118. PMID: 30275043; PMCID: PMC6169832.

- Zafari N, Khosravi F, Rezaee Z, Esfandyari S, Bahiraei M, Bahramy A, Ferns GA, Avan A. The role of the tumor microenvironment in colorectal cancer and the potential therapeutic approaches. J Clin Lab Anal. 2022 Aug;36(8):e24585. doi: 10.1002/jcla.24585. Epub 2022 Jul 8. PMID: 35808903; PMCID: PMC9396196.

- Sorrentino C, D'Antonio L, Fieni C, Ciummo SL, Di Carlo E. Colorectal Cancer-Associated Immune Exhaustion Involves T and B Lymphocytes and Conventional NK Cells and Correlates With a Shorter Overall Survival. Front Immunol. 2021 Dec 16;12:778329. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.778329. PMID: 34975867; PMCID: PMC8716410.

- Borowczak J, Szczerbowski K, Maniewski M, Kowalewski A, Janiczek-Polewska M, Szylberg A, Marszałek A, Szylberg Ł. The Role of Inflammatory Cytokines in the Pathogenesis of Colorectal Carcinoma-Recent Findings and Review. Biomedicines. 2022 Jul 11;10(7):1670. doi: 10.3390/biomedicines10071670. PMID: 35884974; PMCID: PMC9312930.

- Gupta SL, Khan N, Basu S, Soni V. B-Cell-Based Immunotherapy: A Promising New Alternative. Vaccines (Basel). 2022 May 31;10(6):879. doi: 10.3390/vaccines10060879. PMID: 35746487; PMCID: PMC9227543.

- Michaud D, Steward CR, Mirlekar B, Pylayeva-Gupta Y. Regulatory B cells in cancer. Immunol Rev. 2021 Jan;299(1):74-92. doi: 10.1111/imr.12939. Epub 2020 Dec 23. PMID: 33368346; PMCID: PMC7965344.

- Zheng Z, Wieder T, Mauerer B, Schäfer L, Kesselring R, Braumüller H. T Cells in Colorectal Cancer: Unravelling the Function of Different T Cell Subsets in the Tumor Microenvironment. Int J Mol Sci. 2023 Jul 19;24(14):11673. doi: 10.3390/ijms241411673. PMID: 37511431; PMCID: PMC10380781.

- Dwivedi M, Tiwari S, Kemp EH, Begum R. Implications of regulatory T cells in anti-cancer immunity: from pathogenesis to therapeutics. Heliyon. 2022 Aug 27;8(8):e10450. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e10450. PMID: 36082331; PMCID: PMC9445387.

- Malmberg KJ, Carlsten M, Björklund A, Sohlberg E, Bryceson YT, Ljunggren HG. Natural killer cell-mediated immunosurveillance of human cancer. Semin Immunol. 2017 Jun;31:20-29. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2017.08.002. Epub 2017 Sep 6. PMID: 28888619.

- Rocca YS, Roberti MP, Juliá EP, Pampena MB, Bruno L, Rivero S, Huertas E, Sánchez Loria F, Pairola A, Caignard A, Mordoh J, Levy EM. Phenotypic and Functional Dysregulated Blood NK Cells in Colorectal Cancer Patients Can Be Activated by Cetuximab Plus IL-2 or IL-15. Front Immunol. 2016 Oct 10;7:413. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2016.00413. PMID: 27777574; PMCID: PMC5056190.

- Bhat AA, Nisar S, Singh M, Ashraf B, Masoodi T, Prasad CP, Sharma A, Maacha S, Karedath T, Hashem S, Yasin SB, Bagga P, Reddy R, Frennaux MP, Uddin S, Dhawan P, Haris M, Macha MA. Cytokine- and chemokine-induced inflammatory colorectal tumor microenvironment: Emerging avenue for targeted therapy. Cancer Commun (Lond). 2022 Aug;42(8):689-715. doi: 10.1002/cac2.12295. Epub 2022 Jul 5. PMID: 35791509; PMCID: PMC9395317.

- Li J, Huang L, Zhao H, Yan Y, Lu J. The Role of Interleukins in Colorectal Cancer. Int J Biol Sci 2020; 16(13):2323-2339. doi:10.7150/ijbs.46651.

- https://www.ijbs.com/v16p2323.htm.

- Huynh Dinh Chien, Nguyen Minh Phuong, Ngo Dinh Trung, Nguyen Xuan Hung, Nguyen Dac Tu, Mai Thi Hien, Le Thi Huyen, Hoang Mai Duy, Le Khac Linh, Nguyen Khoi Quan, Nguyen Viet Hoang, Keith W. Kelley. A Comprehensive Analysis of The Immune System in Healthy Vietnamese People. Heliyon (2024). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e30647.

- Thomson, C.W., Lee, B.P.L. & Zhang, L. Double-negative regulatory T cells.Immunol Res 35, 163–177 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1385/IR:35:1:163.

- Wu Z, Zheng Y, Sheng J, Han Y, Yang Y, Pan H, Yao J. CD3+CD4-CD8- (Double-Negative) T Cells in Inflammation, Immune Disorders and Cancer. Front Immunol. 2022 Feb 10;13:816005. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.816005. PMID: 35222392; PMCID: PMC8866817.

- Peña-Romero AC, Orenes-Piñero E. Dual Effect of Immune Cells within Tumour Microenvironment: Pro- and Anti-Tumour Effects and Their Triggers. Cancers (Basel). 2022 Mar 25;14(7):1681. doi: 10.3390/cancers14071681. PMID: 35406451; PMCID: PMC8996887.

- Fernandez SV, MacFarlane AW 4th, Jillab M, Arisi MF, Yearley J, Annamalai L, Gong Y, Cai KQ, Alpaugh RK, Cristofanilli M, Campbell KS. Immune phenotype of patients with stage IV metastatic inflammatory breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 2020 Dec 2;22(1):134. doi: 10.1186/s13058-020-01371-x. PMID: 33267869; PMCID: PMC7709446.

- Choi J, Maeng HG, Lee SJ, Kim YJ, Kim DW, Lee HN, Namgung JH, Oh HM, Kim TJ, Jeong JE, Park SJ, Choi YM, Kang YW, Yoon SG, Lee JK. Diagnostic value of peripheral blood immune profiling in colorectal cancer. Ann Surg Treat Res. 2018 Jun;94(6):312-321. https://doi.org/10.4174/astr.2018.94.6.312.

- St Paul M, Ohashi PS. The Roles of CD8+ T Cell Subsets in Antitumor Immunity. Trends Cell Biol. 2020 Sep;30(9):695-704. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2020.06.003. Epub 2020 Jul 2. PMID: 32624246.

- Zander R, Schauder D, Xin G, Nguyen C, Wu X, Zajac A, Cui W. CD4+ T Cell Help Is Required for the Formation of a Cytolytic CD8+ T Cell Subset that Protects against Chronic Infection and Cancer. Immunity. 2019 Dec 17;51(6):1028-1042.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2019.10.009. Epub 2019 Dec 3. PMID: 31810883; PMCID: PMC6929322.

- Jakubowska K, Koda M, Grudzińska M, Kańczuga-Koda L, Famulski W. Monocyte-to-lymphocyte ratio as a prognostic factor in peripheral whole blood samples of colorectal cancer patients. World J Gastroenterol. 2020 Aug 21;26(31):4639-4655. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v26.i31.4639. PMID: 32884222; PMCID: PMC7445871.

- Tian Y, Zhang Y, Zhu WQ, Chen XL, Zhou HB, Chen WM. Peripheral Blood Lymphocyte-to-Monocyte Ratio as a Useful Prognostic Factor in Newly Diagnosed Multiple Myeloma. BioMed Res Int. 2018;2018:9434637. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar].

- Xiang J, Zhou L, Li X, Bao W, Chen T, Xi X, He Y, Wan X. Preoperative Monocyte-to-Lymphocyte Ratio in Peripheral Blood Predicts Stages, Metastasis, and Histological Grades in Patients with Ovarian Cancer. Transl Oncol. 2017 Feb;10(1):33-39. doi: 10.1016/j.tranon.2016.10.006. Epub 2016 Nov 24. PMID: 27888711; PMCID: PMC5124360.

- Waidhauser J, Nerlinger P, Arndt TT, Schiele S, Sommer F, Wolf S, Löhr P, Eser S, Müller G, Claus R, Märkl B, Rank A. Alterations of circulating lymphocyte subsets in patients with colorectal carcinoma. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2022 Aug;71(8):1937-1947. doi: 10.1007/s00262-021-03127-8. Epub 2021 Dec 20. PMID: 34928423; PMCID: PMC9293872.

- Spacek, Jan, Michal Vocka , Irena Netikova, Helena Skalova, Pavel Dundr, Bohuslav Konopasek, Eva Zavadova, and Petruzelka Lubos. 2018. “Immunological Examination of Peripheral Blood in Patients with Colorectal Cancer Compared to Healthy Controls.” Immunological Investigations 47 (7): 643–53. doi:10.1080/08820139.2018.1480030.

- Sharonov GV, Serebrovskaya EO, Yuzhakova DV, Britanova OV, Chudakov DM. B cells, plasma cells and antibody repertoires in the tumor microenvironment. Nat Rev Immunol (2020) 20(5):294–307. doi: 10.1038/s41577-019-0257-x [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar.

- Qin Y, Lu F, Lyu K, Chang AE, Li Q. Emerging concepts regarding pro- and anti tumor properties of B cells in tumor immunity. Front Immunol. 2022 Jul 28;13:881427. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.881427. PMID: 35967441; PMCID: PMC9366002.

- Largeot A, Pagano G, Gonder S, Moussay E, Paggetti J. The B-side of Cancer Immunity: The Underrated Tune. Cells. 2019 May 13;8(5):449. doi: 10.3390/cells8050449. PMID: 31086070; PMCID: PMC6562515.

- Pollock RE, Roth JA. Cancer-induced immunosuppression: implications for therapy? Semin Surg Oncol. 1989;5(6):414-9. doi: 10.1002/ssu.2980050607. PMID: 2688031.

- Yuen GJ, Demissie E, Pillai S. B lymphocytes and cancer: a love-hate relationship. Trends Cancer. 2016 Dec;2(12):747-757. doi: 10.1016/j.trecan.2016.10.010. PMID: 28626801; PMCID: PMC5472356.

- Griss J, Bauer W, Wagner C, Simon M, Chen M, Grabmeier-Pfistershammer K, Maurer-Granofszky M, Roka F, Penz T, Bock C, Zhang G, Herlyn M, Glatz K, Läubli H, Mertz KD, Petzelbauer P, Wiesner T, Hartl M, Pickl WF, Somasundaram R, Steinberger P, Wagner SN. B cells sustain inflammation and predict response to immune checkpoint blockade in human melanoma. Nat Commun. 2019 Sep 13;10(1):4186. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-12160-2. PMID: 31519915; PMCID: PMC6744450.

- Yu, Yifei, Chenxu Lu, Weiru Yu, Yumei Lei, Siyuan Sun, Ping Liu, Feirong Bai, Yu Chen, and Juan Chen. 2024. "B Cells Dynamic in Aging and the Implications of Nutritional Regulation" Nutrients 16, no. 4: 487. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16040487.

- Reitsam NG, Märkl B, Dintner S, Sipos E, Grochowski P, Grosser B, Sommer F, Eser S, Nerlinger P, Jordan F, Rank A, Löhr P, Waidhauser J. Alterations in Natural Killer Cells in Colorectal Cancer Patients with Stroma AReactive Invasion Front Areas (SARIFA). Cancers (Basel). 2023 Feb 3;15(3):994. doi: 10.3390/cancers15030994. PMID: 36765951; PMCID: PMC9913252.

- Zu, S., Lu, Y., Xing, R., Chen X., Zhang L. 2024. Changes in subset distribution and impaired function of circulating natural killer cells in patients with colorectal cancer. Sci Rep 14, 12188. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-63103-x.

- Liu, Dongshui & Sun, Xiaoshan & Du, Yue & Kong, Minmin. (2018). Propofol Promotes Activity and Tumor-Killing Ability of Natural Killer Cells in Peripheral Blood of Patients with Colon Cancer. Medical Science Monitor. 24. 6119-6128. 10.12659/MSM.911218.].

- Tang YP, Xie MZ, Li KZ, Li JL, Cai ZM, Hu BL. Prognostic value of peripheral blood natural killer cells in colorectal cancer. BMC Gastroenterol. 2020 Feb 7;20(1):31. doi: 10.1186/s12876-020-1177-8. PMID: 32028908; PMCID: PMC7006176.

- Shibutani M, Maeda K, Nagahara H, Fukuoka T, Nakao S, Matsutani S, Hirakawa K, Ohira M. The peripheral monocyte count is associated with the density of tumor-associated macrophages in the tumor microenvironment of colorectal cancer: a retrospective study. BMC Cancer. 2017 Jun 5;17(1):404. doi: 10.1186/s12885-017-3395-1. PMID: 28583114; PMCID: PMC5460583.

- Chan JC, Chan DL, Diakos CI, Engel A, Pavlakis N, Gill A, Clarke SJ. The Lymphocyte-to-Monocyte Ratio is a Superior Predictor of Overall Survival in Comparison to Established Biomarkers of Resectable Colorectal Cancer. Ann Surg. 2017 Mar;265(3):539-546. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000001743. PMID: 27070934; PMCID: PMC5300029.

- Shibutani M, Maeda K, Nagahara H, Iseki Y, Ikeya T, Hirakawa K. Prognostic significance of the preoperative lymphocyte-to-monocyte ratio in patients with colorectal cancer. Oncol Lett. 2017;13:1000–1006. [PMC free article][PubMed] [Google Scholar].

- Gosselin D, Link VM, Romanoski CE, Fonseca GJ, Eichenfield DZ, Spann NJ, Stender JD, Chun HB, Garner H, Geissmann F, Glass CK. Environment drives selection and function of enhancers controlling tissue-specific macrophage identities. Cell. 2014 Dec 4;159(6):1327-40. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.11.023. PMID: 25480297; PMCID: PMC4364385.

- Mirzokhid Rakhmanov, Baerbel Keller, Sylvia Gutenberger, Christian Foerster, Manfred Hoenig, Gertjan Driessen, Mirjam van der Burg, Jacques J. van Dongen, Elisabeth Wiech, Marcella Visentini, Isabella Quinti, Antje Prasse, Nadine Voelxen, Ulrich Salzer, Sigune Goldacker, Paul Fisch, Hermann Eibel, Klaus Schwarz, Hans-Hartmut Peter, and Klaus Warnatz. Circulating CD21low B cells in common variable immunodeficiency resemble tissue homing, innate-like B cells. PNAS August 11, (2009) vol. 106 no. 3213451–13456. www.pnas.orgcgidoi10.1073pnas.0901984106.

- Gjertsson I, McGrath S, Grimstad K, Jonsson CA, Camponeschi A, Thorarinsdottir K, Mårtensson IL. A close-up on the expanding landscape of CD21-/low B cells in humans. Clin Exp Immunol. 2022 Dec 31;210(3):217-229. doi: 10.1093/cei/uxac103. PMID: 36380692; PMCID: PMC9985162.

- Rea IM, Gibson DS, McGilligan V, McNerlan SE, Alexander HD and Ross OA (2018) Age and Age-Related Diseases: Role of Inflammation Triggers and Cytokines. Front. Immunol. 9:586. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.00586.

- Vossenkämper A, Blair PA, Safinia N, Fraser LD, Das L, Sanders TJ, Stagg AJ, Sanderson JD, Taylor K, Chang F, Choong LM, D'Cruz DP, Macdonald TT, Lombardi G, Spencer J. A role for gut-associated lymphoid tissue in shaping the human B cell repertoire. J Exp Med. 2013 Aug 26;210(9):1665-74. doi: 10.1084/jem.20122465. Epub 2013 Aug 12. PMID: 23940259; PMCID: PMC3754866.

- Loder F, Mutschler B, Ray RJ, Paige CJ, Sideras P, Torres R, Lamers MC, Carsetti R. B cell development in the spleen takes place in discrete steps and is determined by the quality of B cell receptor-derived signals. J Exp Med. 1999 Jul 5;190(1):75-89. doi: 10.1084/jem.190.1.75. PMID: 10429672; PMCID: PMC2195560.

- Cain D, Kondo M, Chen H, Kelsoe G. Effects of acute and chronic inflammation on B-cell development and differentiation. J Invest Dermatol. 2009 Feb;129(2):266-77. doi: 10.1038/jid.2008.286. PMID: 19148216; PMCID: PMC2778726.

- Rihacek M, Bienertova-Vasku J, Valik D, Sterba J, Pilatova K, Zdrazilova-Dubska L. B-Cell Activating Factor as a Cancer Biomarker and Its Implications in Cancer-Related Cachexia. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015:792187. doi: 10.1155/2015/792187. Epub 2015 Aug 3. PMID: 26339644; PMCID: PMC4538579.

- Carrillo-Ballesteros FJ, Oregon-Romero E, Franco-Topete RA, Govea-Camacho LH, Cruz A, Muñoz-Valle JF, Bustos-Rodríguez FJ, Pereira-Suárez AL, Palafox-Sánchez CA. B-cell activating factor receptor expression is associated with germinal center B-cell maintenance. Exp Ther Med. 2019 Mar;17(3):2053-2060. doi: 10.3892/etm.2019.7172. Epub 2019 Jan 15. PMID: 30783477; PMCID: PMC6364250.

- Zhou, Yang & Zhang, Ying & Han, Jinming & Yang, Meng-Ge & Zhu, Jie & Jin, Tao. (2020). Transitional B cells involved in autoimmunity and their impact on neuroimmunological diseases. Journal of Translational Medicine. 18. 10.1186/s12967-020-02289-w.

- Elissa K. Deenick, Jhagvaral Hasbold, Philip D. Hodgkin; Switching to IgG3, IgG2b, and IgA Is Division Linked and Independent, Revealing a Stochastic Framework for Describing Differentiation. J Immunol 1 November 1999; 163 (9): 4707–4714. https://doi.org/10.4049/jimmunol.163.9.4707.

- Kinker GS, Vitiello GAF, Ferreira WAS, Chaves AS, Cordeiro de Lima VC, Medina TDS. B Cell Orchestration of Anti-tumor Immune Responses: A Matter of Cell Localization and Communication. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2021 Jun 7;9:678127. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2021.678127. PMID: 34164398; PMCID: PMC8215448.

- Qin Y, Lu F, Lyu K, Chang AE, Li Q. Emerging concepts regarding pro- and anti tumor properties of B cells in tumor immunity. Front Immunol. 2022 Jul 28;13:881427. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.881427. PMID: 35967441; PMCID: PMC9366002.

- Qin ZH, Richter G, Schuler T, Ibe S, Cao XT, Blankenstein T. B cells inhibit induction of T cell-dependent tumor immunity. Nat Med (1998) 4(5):627–30. doi: 10.1038/nm0598-627 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar].

- Qin Y, Lu F, Lyu K, Chang AE, Li Q. Emerging concepts regarding pro- and anti tumor properties of B cells in tumor immunity. Front Immunol. 2022 Jul 28;13:881427. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.881427. PMID: 35967441; PMCID: PMC9366002.

- Fischer K, Voelkl S, Heymann J, Przybylski GK, Mondal K, Laumer M, Kunz-Schughart L, Schmidt CA, Andreesen R, Mackensen A. Isolation and characterization of human antigen-specific TCR alpha beta+ CD4(-)CD8- double-negative regulatory T cells. Blood. 2005 Apr 1;105(7):2828-35. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-07-2583. Epub 2004 Nov 30. PMID: 15572590.

- Zhang ZX, Yang L, Young KJ, DuTemple B, Zhang L. Identification of a previously unknown antigen-specific regulatory T cell and its mechanism of suppression. Nat Med. 2000 Jul;6(7):782-9. doi: 10.1038/77513. PMID: 10888927.

- Fang L, Ly D, Wang SS, Lee JB, Kang H, Xu H, Yao J, Tsao MS, Liu W, Zhang L. Targeting late-stage non-small cell lung cancer with a combination of DNT cellular therapy and PD-1 checkpoint blockade. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2019 Mar 11;38(1):123. doi: 10.1186/s13046-019-1126-y. PMID: 30857561; PMCID: PMC6413451.

- Di Blasi D, Boldanova T, Mori L, Terracciano L, Heim MH, De Libero G. Unique T-Cell Populations Define Immune-Inflamed Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;9(2):195-218. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmgh.2019.08.004. Epub 2019 Aug 22. PMID: 31445190; PMCID: PMC6957799.

- Liu Z, Meng Q, Bartek J Jr, Poiret T, Persson O, Rane L, Rangelova E, Illies C, Peredo IH, Luo X, Rao MV, Robertson RA, Dodoo E, Maeurer M. Tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) from patients with glioma. Oncoimmunology. 2016 Nov 29;6(2):e1252894. doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2016.1252894. PMID: 28344863; PMCID: PMC5353900.

- Hall M, Liu H, Malafa M, Centeno B, Hodul PJ, Pimiento J, Pilon-Thomas S, Sarnaik AA. Expansion of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TIL) from human pancreatic tumors. J Immunother Cancer. 2016 Oct 18;4:61. doi: 10.1186/s40425-016-0164-7. PMID: 27777771; PMCID: PMC5067894.

- Zangemeister-Wittke U, Kyewski B, Schirrmacher V. Recruitment and activation of tumor-specific immune T cells in situ. CD8+ cells predominate the secondary response in sponge matrices and exert both delayed-type hypersensitivity-like and cytotoxic T lymphocyte activity. J Immunol. 1989 Jul 1;143(1):379-85. PMID: 2499633.

- Tuttle TM, Inge TH, Lind DS, Bear HD. Adoptive transfer of bryostatin 1-activated T cells provides long-term protection from tumour metastases. Surg Oncol. 1992 Aug;1(4):299-307. doi: 10.1016/0960-7404(92)90091-x. PMID: 1341264.

- Jäger E, Höhn H, Necker A, Förster R, Karbach J, Freitag K, Neukirch C, Castelli C, Salter RD, Knuth A, Maeurer MJ. Peptide-specific CD8+ T-cell evolution in vivo: response to peptide vaccination with Melan-A/MART-1. Int J Cancer. 2002 Mar 20;98(3):376-88. doi: 10.1002/ijc.10165. PMID: 11920589.

- Han J, Khatwani N, Searles TG, Turk MJ, Angeles CV. Memory CD8+ T cell responses to cancer. Semin Immunol. 2020 Jun;49:101435. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2020.101435. Epub 2020 Nov 30. PMID: 33272898; PMCID: PMC7738415.

- Oh DY, Kwek SS, Raju SS, Li T, McCarthy E, Chow E, Aran D, Ilano A, Pai CS, Rancan C, Allaire K, Burra A, Sun Y, Spitzer MH, Mangul S, Porten S, Meng MV, Friedlander TW, Ye CJ, Fong L. Intratumoral CD4+ T Cells Mediate Anti-tumor Cytotoxicity in Human Bladder Cancer. Cell. 2020 Jun 25;181(7):1612-1625.e13. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.05.017. Epub 2020 Jun 3. PMID: 32497499; PMCID: PMC7321885.

- Melenhorst JJ, Chen GM, Wang M, Porter DL, Chen C, Collins MA, Gao P, Bandyopadhyay S, Sun H, Zhao Z, Lundh S, Pruteanu-Malinici I, Nobles CL, Maji S, Frey NV, Gill SI, Loren AW, Tian L, Kulikovskaya I, Gupta M, Ambrose DE, Davis MM, Fraietta JA, Brogdon JL, Young RM, Chew A, Levine BL, Siegel DL, Alanio C, Wherry EJ, Bushman FD, Lacey SF, Tan K, June CH. Decade-long leukaemia remissions with persistence of CD4+ CAR T cells. Nature. 2022 Feb;602(7897):503-509. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-04390-6. Epub 2022 Feb 2. Erratum in: Nature. 2022 Dec;612(7941):E22. doi: 10.1038/s41586-022-05376-8. PMID: 35110735; PMCID: PMC9166916.

- Veatch JR, Lee SM, Shasha C, Singhi N, Szeto JL, Moshiri AS, Kim TS, Smythe K, Kong P, Fitzgibbon M, Jesernig B, Bhatia S, Tykodi SS, Hall ET, Byrd DR, Thompson JA, Pillarisetty VG, Duhen T, McGarry Houghton A, Newell E, Gottardo R, Riddell SR. Neoantigen-specific CD4+ T cells in human melanoma have diverse differentiation states and correlate with CD8+ T cell, macrophage, and B cell function. Cancer Cell. 2022 Apr 11;40(4):393-409.e9. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2022.03.006. PMID: 35413271; PMCID: PMC9011147.

- Oliveira G, Stromhaug K, Cieri N, Iorgulescu JB, Klaeger S, Wolff JO, Rachimi S, Chea V, Krause K, Freeman SS, Zhang W, Li S, Braun DA, Neuberg D, Carr SA, Livak KJ, Frederick DT, Fritsch EF, Wind-Rotolo M, Hacohen N, Sade-Feldman M, Yoon CH, Keskin DB, Ott PA, Rodig SJ, Boland GM, Wu CJ. Landscape of helper and regulatory antitumour CD4+T cells in melanoma. Nature. 2022 May;605(7910):532-538. doi: 10.1038/s41586-022-04682-5. Epub 2022 May 4. PMID: 35508657; PMCID: PMC9815755.

- Kruse, B., Buzzai, A.C., Shridhar, N. et al. CD4+ T cell-induced inflammatory cell death controls immune-evasive tumours. Nature 618, 1033–1040 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-023-06199-x.