1. Introduction

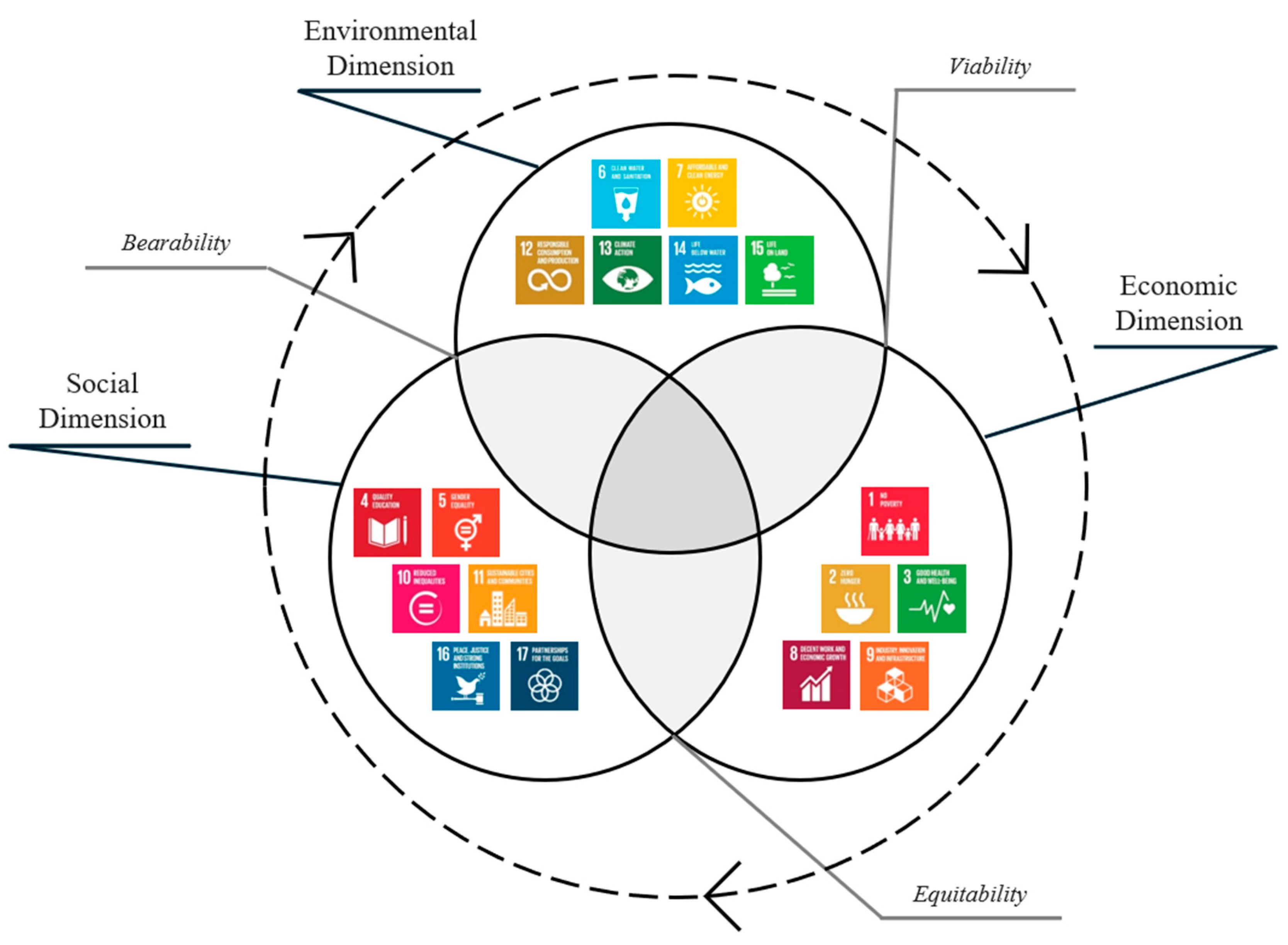

Within the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) (UN, 2015), the one that concerns cities as a global vision of a sustainable community implies a rethinking of various roles, especially those linked to efficient planning and management, and the very conditions of life, inclusion, and access to these areas. It is evident that this goal does not exist in isolation from the others. Therefore, it is essential to comprehend it as part of a more intricate whole (Gupta & Vegelin, 2016; WCED, 1987). To achieve this, it is necessary to have citizens who are capable of understanding past actions, reflecting on present actions and promoting future actions that respond to the complexity inherent in sustainability issues. To this end, it is crucial to promote opportunities for the development of key competences in sustainability. The promotion of competences for sustainability is based not only on its conception as a broad concept of ’ecology’, but as something more complex and interconnected, as can be seen in the adapted 3 key dimensions or pillars of sustainability (presented at

Figure 1).

On

Figure 1 is presented the blending of the SDG and one of the most common Venn diagram of sustainability, emerging also, the interconnectedness of sustainability three pillars. This figure shows the effective connections between Sustainable Development and Sustainability, facilitating an external comprehension of the concepts and its implications. Although its friendly-viewer characteristics, as Lozano (2008) stated, its use can induce a static understating of sustainability, which may lead to poor envisions and actions concerning further enhancement initiatives. Although not focused on this argument, several researchers highlighted that while competences for sustainability are well-established (Redman & Wiek, 2021), its assessment can lead to ambiguity (Annelin & Boström, 2022). Despite all the research on sustainability and its competences, there is a need concerning expanding the studies about its operationalisation (Cebrián et al., 2021) and assessment (Annelin & Boström, 2022). These features, in a broader range, the need of contextualized actions, adapted to specific contexts.

Considering these characteristics, it is essential that activities are developed which not only promote the development of sustainability competences, but also assess their mobilisation or acquisition.

The aim of this paper is to inform about the rationale of using GreenComp framework (Bianchi et al., 2022) as the basis of the development of a data collection tool, namely, a questionnaire, which aims to be an instrument to assess data about sustainability competences-oriented activities.

This paper represents the second of three academic articles developed as part of the EduCITY Research and Development project (

https://educity.web.ua.pt/). The first and previous paper (Ferreira-Santos, Pombo, et al., 2024) describes a systematized literature review process which, although it didn’t provide the expected information, allowed the EduCITY team to get acquaintance of the GreenComp, the European Sustainability framework which was essential for the development of the data collection tool used by the EduCITY team. The third and last paper (Ferreira-Santos, Marques, et al., 2024) explains the development of the data collection tool based on Greencomp. In between, this current paper takes a different approach from the other two, in terms of its structure. The context is emphasised more than the methodology itself, which is discussed in the first and third papers.

Thus, this paper is divided into nine sections. The first section is focused on a contextual introduction and the background of this study. The second section concerns an insight into competences for sustainability frameworks by Wiek and colleagues. In the third section is briefly presented the methodology, based on a overview review of literature, informed by previous research works and by the first paper (Ferreira-Santos, Pombo, et al., 2024) of this series of three papers. The fourth section is about the analyses and rationality of using GreenComp framework (Bianchi et al., 2022). The fifth section concerns the EduCITY project, that enhanced this own broader study. The sixth and seventh sections concerns the conclusion and future work. These sections are followed by the Acknowledgments, and then by technical aspects of this work. The last section concerns the References.

2. Insights on Competences for Sustainability Frameworks by Wiek and Colleagues

The interconnected environmental, economic, and social challenges of the present era require transformative approaches to Education for Sustainable Development (ESD), with the objective of equipping individuals with the essential competences required to navigate and address complex sustainability issues. Wiek, Withycombe, and Redman (2011) presented a framework that outlined five key-competences: systems-thinking, anticipatory competence, normative competence, strategic competence, and interpersonal competence. These competences are essential for the comprehension, analysis and active engagement towards sustainability in both practical and transformative paths. Each competence contributes to sustainability and sustainable development in a unique approach, enabling citizens (learners, educators and general public) to surpass mere theoretical knowledge and cultivate the critical thinking and ethical decision-making abilities essential for practical applications. In 2021, Redman and Wiek presented a renewed literature-based framework concerning more competences, focusing on its transformative role.

2.1. The core Competences

The works of Wiek et al. (2011) and Redman and Wiek (2021) specify a thorough range of abilities necessary for empowering sustainability practitioners to deal with the challenges posed by sustainability problems. The fundamental competences - systems thinking, futures (or anticipatory) thinking, values (or normative) thinking, strategic planning, and interpersonal collaboration - furnish a structured, multifaceted methodology for cultivating well-rounded sustainability professionals. Each of these competences assumes a pivotal role in comprehending and addressing sustainability issues, and collectively they empower individuals to perceive challenges from interrelated perspectives, thereby enhancing their capacity to devise adaptive, holistic solutions. The fundamental competences constitute foundational proficiencies that furnish a robust framework for sustainability education and practice. Systems thinking enables experts to see the comprehensive landscape and pinpoint interconnections within social, environmental, and economic structures. Futures thinking stimulates the envisioning and strategizing for potential scenarios, enabling professionals to prepare for uncertainties and long-term ramifications. Normative (values) thinking underscores ethical consciousness, directing individuals to make choices anchored in social justice, equity, and responsibility. Strategic competence cultivates the ability to formulate actionable plans that can adjust to evolving circumstances, bridging the divide between theory and practice. Lastly, interpersonal competence accentuates the significance of collaboration and empathy, facilitating effective partnerships across sectors and communities.

Redman and Wiek’s (2021) introduction of emergent competences - intrapersonal, implementation, and integration - addresses the progressive requirements of sustainability endeavors, underscoring personal resilience, practical skills, and an integrative methodology. Intrapersonal competence concentrates on self-care and emotional resilience, acknowledging the personal toll that sustainability endeavors can impose and advocating for sustained well-being. This resilience also bolsters effective collaboration, which is correlated with interpersonal competence. Implementation competence connects core strategic thinking skills by emphasizing the practical execution of plans, ensuring that sustainability strategies can be adapted and scaled for tangible impact. Finally, integration competence extends systems thinking by promoting the ability to amalgamate insights from multiple domains - such as anticipatory, normative, and strategic thinking - into cohesive, adaptive solutions. This integrative methodology enables sustainability practitioners to formulate responses that are as interconnected as the challenges they confront.

Wiek et al. (2011) furnish a foundational comprehension of systems-thinking, delineating it as indispensable for “mapping out” intricate relationships across environmental, social, and economic spheres. They underscore that systems-thinking transcends mere understanding of connections; it encompasses the capacity to dynamically model and scrutinize systemic structures, empowering learners to discern patterns and leverage points for strategic intervention. This process entails integrating both qualitative and quantitative data, facilitating students to grasp how social, economic, and environmental systems interact in both predictable and unforeseen manners.

Building upon this foundation, Redman and Wiek (2021) accentuate the significance of systems-thinking as a fundamental competency for future sustainability professionals. This competence enables learners to confront sustainability challenges not as discrete issues but as components of larger, intricate systems with complex interdependencies. Comprehending how, for instance, energy policies might influence environmental health, social equity, and economic growth is imperative for devising solutions that are both robust and holistic. By nurturing this skill, students learn to identify feedback loops, cascading effects, and systemic leverage points that can yield substantial positive impacts.

The two works converge in their mutual emphasis on systems-thinking as a essential framework for impactful sustainability problem-solving. In their 2011 work, Wiek and colleagues explore the underlying theories necessary for creating organized, systematic models, unlike Redman and Wiek (2021), who focus on real-world applications, demonstrating how systems-thinking helps professionals uncover hidden links and lessen unforeseen effects. Collectively, they reinforce systems-thinking as an essential approach for anyone aspiring to make meaningful, long-term contributions to sustainability. This competence is particularly pertinent in contexts where participants analyse urban environments as dynamic systems, recognising the intricate interconnections between factors such as public health, waste management and resource allocation. For instance, activities concentrating on urban waste can illustrate the cascading effects of waste practices on pollution, public health and economic resources, thereby reinforcing the significance of systems thinking in sustainability contexts.

Wiek et al (2011) define anticipatory competence, or futures-thinking, as the ability to imagine and plan for different possible futures. This skill equips students to deal with uncertainty in sustainability by encouraging them to explore different future scenarios, work backwards from ideal outcomes, and map out actionable steps to achieve these goals. The process includes tools such as backcasting and scenario planning, which help students develop resilient strategies that can adapt to changing conditions.

In their extended framework, Redman and Wiek (2021) emphasise the value of anticipatory competence for sustainability practitioners, urging them to think beyond immediate solutions and consider the long-term implications of current actions. This competency involves creating scenarios and forecasts that account for future changes, helping students prepare for unexpected shifts in sustainability challenges. By honing this skill, learners can develop adaptable, forward-looking strategies that promote a proactive rather than reactive approach to sustainability.

The connection between the two documents lies in their shared emphasis on anticipatory competence as a cornerstone of sustainability education. While Wiek et al. (2011) focus on conceptual tools for implementing futures thinking, Redman and Wiek (2021) highlight the growing complexity of sustainability challenges and encourage students to refine these anticipatory skills to meet emerging trends. Together, they frame anticipatory competence as essential for creating adaptable, resilient sustainability strategies.

Wiek et al (2011) introduce ‘normative competence’ (values-thinking) as the ability to recognise and integrate sustainability values, ethics and principles into decision-making. They emphasise that this ability goes beyond understanding values; it involves actively engaging with ethical dilemmas and conflicts that arise when sustainability ideals intersect with societal constraints. Normative competence encourages learners to assess sustainability from a range of cultural, social and environmental perspectives, promoting a balanced approach that respects both immediate needs and long-term equity.

Redman and Wiek (2021) expand on this by highlighting normative competence as essential to the development of socially responsible professionals who can address real-world ethical dilemmas. This competence enables students to evaluate issues through the lenses of social justice, environmental responsibility and ethical integrity, and guides them to make fair and just decisions. It is presented as both a reflective and action-oriented approach, enabling students to promote environmental and social justice in their work.

The synergy between the two documents is evident in their shared commitment to embedding normative competence in sustainability education. Wiek et al. (2011) lay the groundwork by emphasising ethical engagement, while Redman and Wiek (2021) emphasise its practical relevance in preparing students to deal with complex, real-world ethical challenges. Together, they frame normative competence as an essential component for advancing sustainability responsibly and equitably. In practical applications, learners may be prompted to consider the social justice aspects of sustainability by evaluating the impact of specific urban interventions on different demographic groups.

Wiek et al. (2011) describe ‘strategic competence’ as the capability to convert sustainability visions into practical strategies. They highlight a hands-on learning method that motivates students to create, evaluate, and improve strategies in practical situations. This practical education fosters the resilience and flexibility required to tackle changing sustainability issues. Strategic competence, as they define it, encompasses the capability to modify plans in reaction to shifting conditions and is vital for sustainability experts.

Redman and Wiek (2021) strengthen and expand strategic competence, highlighting its importance in connecting theory to practice. This skill set includes practical abilities in planning, project management, and adaptability that enable students to convert sustainability knowledge into impactful, real-world actions. By developing strategic skills, learners transform into proactive change agents capable of executing sustainable solutions that tackle both technical and social aspects.

The two studies are connected through their shared emphasis on action-based learning. Although Wiek et al. (2011) offer a fundamental framework for strategic competence, Redman and Wiek (2021) revise it by highlighting the growing necessity for adaptability and responsiveness to modern sustainability issues. Collectively, they establish strategic competence as crucial for transitioning from theoretical comprehension to practical, flexible solutions in actual situations. The formulation of strategies for addressing tangible issues, such as energy conservation or water management, provides an opportunity for participants to develop decision-making and planning abilities, which are crucial for facilitating systemic change. This competency is in close alignment with Redman and Wiek’s (2021) assertion that strategic planning is a crucial element in driving transformative action.

Wiek et al. (2011) highlight ‘interpersonal competence’ as a critical skill for sustainability professionals, noting that many sustainability efforts depend on effective teamwork and collaboration. This competence includes active listening, empathy, and conflict resolution, which are vital for fostering collaboration and navigating diverse perspectives. Interpersonal competence is particularly valuable in education models that prioritize experiential and project-based learning, helping students to manage complex social dynamics in sustainability projects.

Redman and Wiek (2021) build on this foundation, emphasizing interpersonal competence as a necessary skill for engaging with diverse stakeholders in sustainability settings. This competence enables students to work effectively with communities, policymakers, and colleagues across disciplines, fostering inclusive and cooperative approaches. By cultivating interpersonal skills, students learn to bridge differences, build trust, and facilitate group cohesion around shared sustainability goals, ensuring that solutions are socially inclusive and culturally sensitive. Also, Wiek et al. (2011) advances that interpersonal competence is instrumental in enabling learners to navigate the complexities of multiple perspectives and to function effectively within diverse teams. Group-based tasks, in which participants are required to collaborate in addressing sustainability issues, facilitate the development of communication and teamwork abilities, which are pivotal for the advancement of shared sustainability objectives.

2.2. The Emerging Competences in Sustainability

In their 2021 update, Redman and Wiek introduce three new competences—Intrapersonal, Implementation, and Integration—that capture some of the latest demands in sustainability work. These competences address the importance of personal resilience, turning plans into real-world action, and seeing sustainability through a holistic lens. They build on the foundational skills from 2011, bringing a more nuanced and practical approach to sustainability education and practice.

The ‘intrapersonal competence’ focuses on self-care, emotional resilience and maintaining personal well-being. Sustainability work can be incredibly rewarding, but it’s also challenging and often involves navigating emotionally charged issues, from climate crises to social injustice. These situations can lead to stress, frustration and even burnout. Redman and Wiek (2021) emphasise the need for sustainability professionals to develop skills to manage this personal toll - cultivating self-awareness, practicing stress management, and engaging in reflection to sustain themselves over the long term.

This personal focus enhances interpersonal competence, as people who take care of their own well-being are often more empathetic and open, which is crucial for working together. Intrapersonal competence is also closely linked to normative competence, as self-reflection allows practitioners to stay grounded in their values and make ethically sound decisions, even under pressure. By prioritising self-care and resilience, this competency helps ensure that practitioners can cope with the inevitable challenges of sustainability work without compromising their principles or burning out.

The term ’implementation competence’ is used to describe the process of bridging the gap between the planning and the actual doing of a task. While sustainability education frequently places an emphasis on theoretical knowledge and strategy, Redman and Wiek (2021) highlight the importance of providing students with the skills necessary to effectively implement these plans. Implementation competence encompasses project management, practical planning, and adaptability, all of which are vital for transforming ideas into actions that have a tangible impact. In essence, it is about ensuring that well-conceived sustainability strategies are not merely ideas on paper but rather become concrete, quantifiable changes in the world.

This competence is closely linked to strategic competence. While strategic thinking helps professionals map out what needs to be done, implementation competence ensures they know how to make it happen and adapt as they go. Together, these skills prepare professionals not only to create smart, sustainable plans but also to execute them effectively, managing resources and overcoming obstacles along the way. By honing both strategy and implementation, sustainability practitioners are better prepared to drive real, lasting change.

The ‘integration competence’ refers to the ability to understand the whole of a particular situation and to combine different components into a cohesive viewpoint. Sustainability efforts rarely focus on simple, one-dimensional challenges; instead, they involve understanding the complexities of issues that span the domains of the environment, social factors, and the economy. Integration competence empowers professionals to combine knowledge from various fields of expertise, thus enabling the creation of solutions that tackle interconnected issues in a cohesive and flexible way. Redman and Wiek (2021) highlight the importance of this skill in tackling today’s complex sustainability challenges, as solutions that are overly specialized often fall short.This comprehensive method relies on the idea of systems thinking, highlighting the significance of recognizing the connections among various components. Nonetheless, integration competence goes further, allowing professionals to not only recognize these connections but also to merge varied skills and perspectives into a cohesive approach. Through the combination of insights from anticipatory, normative, and strategic skills, integration competence enables the creation of flexible solutions capable of adjusting to the complexities of real-world issues. This type of integrative thinking provides professionals with the ability to react swiftly and effectively to the complex requirements of sustainability efforts.

Together, these core and emerging competences create a holistic framework for sustainability education and practice. The blend of foundational knowledge, personal resilience, practical application, and interdisciplinary integration equips sustainability professionals to navigate the complexity of sustainability challenges with both clarity and flexibility, preparing them to make a meaningful and lasting impact.

2.3. Integrating and Assessing Competences for Sustainability

Wiek et al. (2011) also emphasises the necessity of integrating these competences, given that sustainability issues rarely present in isolation. Redman and Wiek (2021) further develop this concept by introducing the concept of integrative competence, which involves the simultaneous application of multiple competences to develop comprehensive solutions to sustainability challenges. The concept of integrative competence is particularly pertinent in the context of complex, real-world applications of sustainability, where the ability to balance ethical considerations, systems thinking and strategic planning is of paramount importance. Those engaged in integrative learning may derive benefit from tasks requiring the application of a range of competences in a simultaneous manner. This approach allows for the analysis, planning and action to be undertaken concurrently, thereby capturing the interconnected and multidimensional nature of sustainability work.

Although these competences are crucial for enabling learners to drive sustainable development, evaluating them remains a significant challenge. The limitations of traditional assessment methods are such that they are unable to adequately capture the complexity and situational nature of competences such as systems thinking or anticipatory skills, particularly in the context of real-world applications (Wiek et al., 2011). Redman and Wiek (2021) posit that competences such as interpersonal skills and normative judgement are inherently subjective and context-dependent, necessitating the development of innovative assessment tools that transcend the limitations of quantitative measures.

In order to address these challenges, alternative approaches are being increasingly valued, including in-depth project assessments, reflective journals and progressive tracking over time. In contrast to the use of single-time evaluations, these methods facilitate the capture of the nuanced evolution of competences, enabling assessment across a range of contexts and time periods (Redman & Wiek, 2021). The provision of real-time feedback, the elicitation of qualitative reflections, and the analysis of how participants interact with real-world tasks facilitate a more profound comprehension of competences. For example, the evaluation of interpersonal competence can be conducted through the observation of learners engaged in collaborative tasks, whereas the assessment of systems thinking may be based on the insights provided by participants regarding the connections they have identified within complex systems. The implementation of these diverse forms of evaluation enables assessments to more accurately reflect the evolution and integration of competences, thereby providing a comprehensive perspective on learners’ transformative growth.

Wiek et al. (2011) highlight the importance of situational assessments, which reflect real-world applications, as experiential learning is a fundamental aspect of sustainability education. Longitudinal studies, in particular, offer valuable insights by tracking competency development over extended periods, thereby capturing how learners apply and refine their skills as they encounter new sustainability challenges. This method assists educators and researchers in comprehending the enduring influence of ESD initiatives, offering a more comprehensive perspective on the evolution of competences for sustainability in dynamic and diverse contexts.

It is essential to develop activities that promote the development of competences for sustainability, as this is an indispensable step towards raising awareness of the various challenges related to sustainable development.

Despite the amount of information available, there is a need for concrete actions and activities that explore the development of these competences for a wide range of audiences and its assessment.

Although the initial proposal by Wiek et al. (2011) concentrated on the development of competences in the training of professionals within the context of higher education (Kudo et al., 2018), it was quickly recognised that, given the potential for future action by this target group, activities to develop and acquire competences for sustainability should start downstream (Olsson et al., 2022; Vesterinen & Ratinen, 2024). It is crucial to acknowledge the significance of promoting competences for sustainability among students at the initial stages of their academic journey. To this end, it is vital to implement initiatives that address this necessity and offer educational and training experiences that are contextualised and aligned with the specificities and curricular needs of school-age target audience, and educators, but also targeting to wider public. These features are a core concerning on a recent sustainability competences framework, GreenComp (Bianchi et al., 2022). This framework, also known as ‘The European sustainability competence framework’ became essential to the development of the EduCITY’s data tool collection. Although recognizeing the pivotal works by Wiek and collegueas, the aims of the GreenComp connected with EduCITY own research question (see end of section 4).

3. Methodology

This paper adopts a overview literature review approach, as outlined by Grant and Booth (2009), building on the methods established in previous work. Whereas the first and third papers in this series relied on systematic review methods to provide depth and rigour, the approach in this paper focuses on a broad, integrative review that synthesises key contributions to the field. An overview approach, also known as a ’review of reviews’, provides a structured, high-level summary that captures the breadth of existing research while allowing for flexible engagement with studies of varying rigour and design. This approach aims to map the existing literature on sustainability competences and their assessment, providing valuable insights for researchers and practitioners new to the field. The rationale for using a review approach lies in its ability to accommodate the broad mapping required for a thorough examination of sustainability competencies and assessment frameworks. By encompassing a wide range of studies, this method allows for the identification of essential works that define the field, with a particular focus on key frameworks such as GreenComp (Bianchi et al., 2022). This overview approach complements the systematic review carried out in the first article of this series, allowing this paper to contextualise the findings with a diachronic perspective. Through this broad-based methodology, the study provides a holistic understanding of the landscape of sustainability competences, revealing patterns and gaps that may not be apparent in a narrower, more limited systematic review.

The mapping of sustainability competencies and assessment frameworks in this paper was conducted using major literature databases, specifically Scopus and Web of Science, to ensure comprehensive coverage. This process took place in three stages. First, the research identified foundational works essential to the field of sustainability competences. This initial selection provided a basis for understanding the key issues, trends and theoretical frameworks that shape this area of research. The second stage involved a diachronic collection of relevant literature, providing a chronological perspective on the development of the field. This phase ran in parallel with the systematized review for the first paper and promoted a multi-layered understanding of key developments and shifts within the literature. In the third stage, the research extended the previous stages, leading to the identification of the GreenComp framework. This final stage enabled an in-depth exploration of sustainability competencies and facilitated alignment with the GreenComp model to provide a nuanced understanding of current assessment strategies and their practical applications.

A key strength of the overview approach is its ability to provide a comprehensive summary of a broad field, which is particularly useful for readers who are new to the topic or seeking a panoramic view of sustainability competencies. By identifying overarching themes and trends, this approach provides an accessible gateway to understanding a complex, multifaceted research landscape. A limitation of the overview approach, however, is its variable degree of rigour, which can occasionally affect the specificity and perceived reliability of findings. Recognising this limitation, organisations such as the Cochrane Collaboration (Higgins et al., 2019) have sought to distinguish rigorous ’systematic overviews’ from more general overviews that may lack explicit methodology. To address this concern, the current study established clear inclusion criteria and used a structured, multistage mapping process, which enhances transparency, rigour and reproducibility. This methodological clarity strengthens the reliability of the findings and supports their utility as a basis for future research and practice.

4. The GreenCOMP Framework

The knowledge about GreenCOMP (Bianchi, et al., 2022) was derived from the systematized literature review presented in the initial article (Ferreira-Santos, Pombo, et al., 2024). Even though this literature review did not yield the anticipated outcomes, the specific reading of two results deemed pertinent for future investigation, namely the article by Hyytinen et al. (2023), facilitated the identification of this framework.

The GreenComp framework (Bianchi, et al., 2022) established by the European Commission is an initiative aimed at enhancing sustainability-oriented competences across educational, professional and wider social domains in Europe. Presented in 2022, GreenComp provides a systematic model for cultivating the knowledge, skills and attitudes considered essential towards the promotion of sustainable development (Bianchi et al., 2022). This framework aligns with the European Union’s persistent goal of achieving climate neutrality by 2050, as well as broader global projects such as the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (UN, 2015) and must be considered as part of a wider set of frameworks published by European institutions, like the “European Green Deal”(European Commision, 2019).

As stated on this framework, its foundations was driven by literature and by experts’ work. Considering this, it is possible to link GreenComp with Wiek and colleagues’ pivotal works. This is demonstrated on

Table 1.

GreenComp is based on four fundamental competence areas: “Emboding sustainability values”, “Embracing complexity in sustainability”, “Envisioning sustainable futures”, and “Acting for sustainability” (Bianchi et al., 2022). These areas are divided into three distinctive competences, whose order concerns wider connections other than being sequential or hierarchized (Bianchi et al., 2022).

The competence area of “Embodying sustainability values” requires a critical review of personal beliefs about sustainability and intergenerational equity, emphasizing humanity’s connection with nature, while addressing the complex socio-ecological challenges that require a comprehensive understanding shaped by our values; thus, transformative learning in educational contexts, incorporating cognitive, psychomotor, and affective elements, can empower individuals to drive significant awareness towards sustainability. The competence area “Embracing complexity in sustainability” focuses on fostering systemic and critical thinking among learners and wider community, promoting the assessment of information, and framing sustainability challenges to understand the interconnectedness of vast socioecological issues. It underscores the importance of understanding the connections between environmental degradation and socio-economic issues, especially for disadvantaged groups, to effectively understand sustainability as a complex challenge. The area of “Envisioning sustainability futures” empowers learners to formulate diverse future scenarios and strategies concerning sustainability, demanding adaptability to address the future uncertainties and effective sustainable development while fostering innovative, interdisciplinary thinking to advance towards circular economy and to cultivate visionary perspectives on future possibilities. Related to this is the need for a self and global analysis of current complex systems that understands them in terms of values and experience to guide sustainable decision-making. “Acting for sustainability” promotes both individual and collective participation to ensure people’s and leaders’ accountability, as sustained anthropogenic warming over the past forty years requires comprehensive technological, cultural, and institutional reforms; thus, local stakeholder collaboration is essential to global sustainability efforts, highlighting that lasting change depends on sustained commitment rather than sporadic initiatives, and ultimately cultivating an attitude of environmental sustainability that empowers individuals with the necessary competences and knowledge to reduce their ecological impact and enhance environmental well-being.

The GreenComp framework has considerable relevance for the integration of sustainability into education and into employment systems, as it is based on broader actions and purposes than education or training. By providing a well-defined, systematic model of sustainability-related competences, GreenComp empowers educators, policy makers and employers to design curricula, training programmes and policies that support sustainable practices (Bianchi et al., 2022). This integration is vital to enhance ecologically aware citizens, which is essential for achieving the goals outlined in the European Green Deal (European Commission, 2019). Furthermore, GreenComp promotes interdisciplinary collaboration and innovation, ensuring that sustainability is recognised as a fundamental component of social, economic and environmental progress, rather than a specialised field. As a result, GreenComp plays an essential role in Europe’s progress towards a sustainable future.

All these characteristics were decisive in defining GreenComp as the basis for the development of the data collection tool used to understand the validity of the EduCITY activities in relation to its research question, which is: “How does an intelligent urban learning environment that integrates a user-friendly application with co-created augmented reality games and resources with pathways and challenges, designed to involve educational actors and the community in general, promote changes in citizens’ knowledge, skills, values and attitudes, empowering them for sustainable development?” (Marques & Pombo, 2022).

Considering the importance of this topic, and in-direct connection between Sustainability-initiatives-based, educational, and technology innovation, the EduCITY project (

https://educity.web.ua.pt/project.php) was developed by a research team of the University of Aveiro. This project aims to aware and enhance the advancement of sustainable urban development through the establishment of a transformative smart learning environment, sustained by a mobile application comprising active location-based games based on challenges, with Augmented Reality and multimedia educational resources.

5. The EduCITY Project

The EduCITY research and development project involves four research units of the University of Aveiro, with researchers from a range of educational and expertise backgrounds.

In light of the necessity for citizens to be aware and adopt more sustainable lifestyles to support healthy ecosystems within urban environments, the project’s primary goal is to contribute to a novel approach in ESD, by addressing the essential research question: How does EduCITY – a smart learning city environment, integrating a user-friendly mobile app with co-created games and appealing Augmented Reality resources, with paths and challenges, targeting educational stakeholders and the wider community – promote changes in knowledge, skills, values and attitudes in citizens to empower them towards sustainable development?

Hence, the EduCITY project is based on the integration of mobile devices and smart technology with educational resources in augmented reality (AR), which are triggered by natural markers selected along a pre-established urban path. While the EduCITY project is designed to capitalise urban space as a learning environment, its purposes are not limited to this humanized context. Rather, it can be used in any development setting, regardless of geographical location. The transformative aspect of the EduCITY innovation is to address a new action-oriented transformative pedagogy that is essential for the development of key competences for sustainable development, by using smart technology, as mobile AR games grounded on challenging paths that move education outside of the classroom. This new knowledge in addition to the technology-enhanced practical solution – the smart learning city environment – can be replicated elsewhere, challenging conventional thinking about how people can learn about their city and change their habits towards sustainable and resilient cities.

The aim of EduCITY games is not merely to provide entertainment or to indulge in ludicism; rather, they are designed with an educational goal at their core. Accordingly, each question is structured according to a quiz-type typology with four answer possibilities. The questions are preceded by an introduction and followed by feedback, which is presented in the form of a positive or incorrect answer, respectively. The construction-process of the questions also makes use of multimedia resources, including images, audio, video and AR. The questions are designed around points of interest, which collectively constitute a pre-established and guided path. The answers to these questions are the data-based material to the EduCITY project research set.

Also, given the essential academic research component inherent within the EduCITY project, concerning the articulation of the project’s research question, which influenced and guided the entire project development process, it was imperative to use or develop an appropriate data collection tool. The rationales for using the questionnaire to collect data is central to the third paper (Ferreira-Santos, Marques, et al., 2024). Although it is important to acknowledge that the construction of this questionnaire was informed by the GreenComp framework.

6. Conclusions

This paper has provided an in-depth exploration of the EduCITY project, with a particular focus on the selection of the GreenComp framework for the design and development of a data collection tool. As part of a series of three papers, this second paper is distinguished by its focus on the broader contextual and theoretical framework, as opposed to the methodological specifics which are discussed in the first and third papers. The contextual approach allows for a deeper understanding of the way in which EduCITY aligns with contemporary trends in education for sustainability and its expanding field of competences and sustainable development.

The decision to adopt GreenComp as the basis for the EduCITY data collection tool was of great significance. As outlined by Bianchi et al. (2022), the GreenCOMP as a framework provides a systematic approach to the development of sustainability competences, which are essential for empowering individuals to engage in sustainable practices in everyday life. The comprehensive focus on the values and complexities of sustainability, aligned with the promotion of active participation, is aligned with the main objective of the EduCITY project and the activities and dynamics derived from it, which is to create educational experiences that foster both the acquisition of knowledge and awareness of possible behavioural changes. This focus is aligned with the broader policy goals of the European Union, as exemplified by the European Green Deal (European Commision, 2019), which aims to integrate sustainability into all aspects of European society, including education.

The use of augmented reality (AR) as an educational tool within the urban space allows for innovative learning methodologies that use physical spaces combined with digital resources to create contextual, interactive and engaging experiences. This approach not only enhances the learning process, but also promotes active citizenship by integrating sustainability education into the lived experience of learners or the wider community. The planning of EduCITY’s AR resources, games, and activities with GreenComp facilitates the practical application of the framework’s key competency areas. The interactive nature of AR enables learners to engage with sustainability challenges in a more meaningful way, fostering deeper connections between knowledge, values, and action (Hyytinen et al., 2023).

Furthermore, the interdisciplinary nature of the EduCITY project, which brings together different research units from the University of Aveiro, adds an additional layer of relevance. The collaboration between experts from different fields allows for the integration of multiple perspectives, thereby enhancing the dimension of the project to address the complex and multifaceted nature of sustainability challenges. As mentioned, Horn et al. (2023), interdisciplinary approaches are essential for effectively addressing sustainability issues, as they draw on a wide range of knowledge and expertise to address socio-environmental challenges.

It is crucial to promote sustainability competences at an early stage of the educational process. Engaging learners in sustainability education from an early age has been shown to have a significant and lasting impact on their attitudes and behaviours towards the environment (UNESCO, 2021). By reaching out to school-age learners, the EduCITY project harnesses their potential and ensures that future generations will be better equipped with the knowledge to address the pressing sustainability challenges of their time.

7. Future Work

Although this paper has examined the incorporation of GreenComp into the construction of the EduCITY data collection tool, there are numerous paths for future research and development that could enhance the effectiveness and impact of this endeavour. These directions represent potential opportunities for further research, a broader scope and the exploration of innovative uses of the EduCITY project.

The third paper in this series will focus on the methodological aspects of development and implementation of the GreenComp-based questionnaire within EduCITY’s games and activities. Also, further research could focus on extending the questionnaire to include more sophisticated metrics that capture behavioural changes, long-term impacts on sustainability competences and potential disparities between different demographic groups. Furthermore, adapting the questionnaire to different cultural and geographical contexts would enhance its relevance and applicability. All these will imply posterior and frequent refinement, like the use of longitudinal studies to ascertain the impact of the EduCITY project on learners’ sustainability competences over time. By examining changes in knowledge, attitudes and behaviours related to sustainability, researchers could assess the long-term effectiveness of the AR-enhanced educational experiences. Such studies could also evaluate whether early engagement with sustainability topics through projects such as EduCITY leads to more sustainable environmental attitudes in later life.

Furthermore, future work should investigate the scalability of EduCITY and assess how it can be integrated into different education systems, possibly in collaboration with schools, communities, and international institutions.

By pursuing these future directions, the EduCITY project has the potential to make an even more significant contribution to sustainability education, empowering citizens and communities to address the pressing environmental challenges of our time.

The third paper in this series (Ferreira-Santos, Marques, et al., 2024) will examine the specific methods used to implement the questionnaire and analyse the data collected from the EduCITY activities. This will provide a deeper understanding of how the GreenComp-based data collection tool can be further refined and adapted to different contexts.

Acknowledgments

The EduCITY project is funded by National Funds through the FCT - Foundation for Science and Technology, I.P., under the PTDC/CED-EDG/0197/2021 project. The first author’s work is financed by National Funds through FCT, under research grant no. 2023.00257.BD. The second author’s work is funded by national funds through FCT, under the Scientific Employment Stimulus - Individual Call (

https://doi.org/10.54499/2022.02153.CEECIND/CP1720/CT0037).

Data Availability Statement

No data is available or was used in this paper. Any secondary data is referenced directly in the text.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conficts of interest.

References

- Annelin, A., & Boström, G. O. (2022). An assessment of key sustainability competencies: a review of scales and propositions for validation. International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education, 24(9), 53–69. [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, G., Pisiotis, U., Cabrera, M., Punie, Y., & Bacigalupo, M. (2022). The European sustainability competence framework. In Publications Office of the European Union. [CrossRef]

- Cebrián, G., Junyent, M., & Mulà, I. (2021). Current practices and future pathways towards competencies in education for sustainable development. Sustainability (Switzerland), 13(16), 8733. [CrossRef]

- European Commision. (2019). The European Green Deal. https://commission.europa.eu/strategy-and-policy/priorities-2019-2024/european-green-deal_en.

- Ferreira-Santos, J., Marques, M. M., & Pombo, L. (2024). GreenComp-Based Questionnaire (GCQuest): Questionnaire Development and Validation. In [unpublished work]. [CrossRef]

- Ferreira-Santos, J., Pombo, L., Marques, M. M., & Rodrigues, R. (2024). Designing a Sustainability Competencies Questionnaire: Insights from a literature review. [Unpublished Work]. [CrossRef]

- Grant, M., & Booth, A. (2009). A typology of reviews: an analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Information & Libraries Journal, 26(2), 91–108. [CrossRef]

- Gupta, J., & Vegelin, C. (2016). Sustainable development goals and inclusive development. International Environmental Agreements: Politics, Law and Economics, 16(3), 433–448. [CrossRef]

- Higgins, J. P. T., Thomas, J., Chandler, J., Cumpston, M., Li, T., Page, M. J., & Welch, V. A. (Eds.). (2019). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Wiley. [CrossRef]

- Horn, A., Urias, E., Klein, J. T., Hess, A., & Zweekhorst, M. B. M. (2023). Expert and non-expert at the same time: knowledge integration processes and dynamics in interdisciplinary teamwork. Sustainability Science, 18(5), 2357–2371. [CrossRef]

- Hyytinen, H., Laakso, S., Pietikäinen, J., Ratvio, R., Ruippo, L., Tuononen, T., & Vainio, A. (2023). Perceived interest in learning sustainability competencies among higher education students. International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education, 24(9), 118–137. [CrossRef]

- Kudo, S., Mursaleen, H., Ness, B., & Nagao, M. (2018). Exercise on Transdisciplinarity: Lessons from a Field-Based Course on Rural Sustainability in an Aging Society. Sustainability, 10(4), 1155. [CrossRef]

- Lozano, R. (2008). Envisioning sustainability three-dimensionally. Journal of Cleaner Production, 16(17), 1838–1846. [CrossRef]

- Marques, M. M., & Pombo, L. (2022). EduCITY as a smart learning city environment towards education for sustainability - work in progress. In T. Bastiaens (Ed.), Proceedings of EdMedia + Innovate Learning (pp. 5595–5601). Association for the Advancement of Computing in Education (AACE). [CrossRef]

- Mebratu, D. (1998). Sustainability and sustainable development. Environmental Impact Assessment Review, 18(6), 493–520. [CrossRef]

- Olsson, D., Gericke, N., & Boeve-de Pauw, J. (2022). The effectiveness of education for sustainable development revisited – a longitudinal study on secondary students’ action competence for sustainability. Environmental Education Research, 28(3), 405–429. [CrossRef]

- Redman, A., & Wiek, A. (2021). Competencies for Advancing Transformations Towards Sustainability. Frontiers in Education, 6(November), 1–11. [CrossRef]

- UN. (2015). Transforming our world: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (A/RES/70/1). UN General Assembly. [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. (2021). Reimagining Our Futures Together: A New Social Contract for Education. https://en.unesco.org/futuresofeducation/.

- Vesterinen, M., & Ratinen, I. (2024). Sustainability competences in primary school education – a systematic literature review. Environmental Education Research, 30(1), 56–67. [CrossRef]

- WCED. (1987). Our Common Future: Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development. http://www.un-documents.net/ocf-ov.htm.

- Wiek, A., Withycombe, L., & Redman, C. (2011). Key competencies in sustainability: A reference framework for academic program development. Sustainability Science, 6(2), 203–218. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).