3.1. Sample Size

In São Paulo,

properties used for agricultural activities were registered, covering

ha. Of this area,

ha are earmarked for preservation and represent approximately

of the total area of rural properties in the state [

42]. In the state of São Paulo, legislation requires that

of the area of each rural property be set aside for LR. According to the state’s Rural Registry System data, around

LRs and

PPAs are registered. This research used approximately

LRs and

PPAs, analyzing around

ha of PPA and

LR.

Table 4 provides more detailed information on using this data.

For the LR studied, the average is

ha compared to

for the PPA. This difference in size is mainly due to federal environmental legislation (by the Brazilian Forest Code), which defines LR as a higher mandatory percentage of the total area of rural properties than PPA. PPA, however, are delimited by specific criteria, such as a preservation area relating to watercourses, springs, and hilltops, and are not directly linked to the property’s total area. This pattern highlights the predominance of smaller areas among PPA. According to Schober (2018) [

43], the differences and variations reported in the quantity and size of areas can have significant geospatial implications. In environmental terms, smaller areas suggest a lower concentration of vegetation and are potentially vulnerable regarding their ecological functionality. Preserved areas of small size generally show less resilience to disturbance and less effectiveness in conserving biodiversity, especially for species that require extensive and connected habitats.

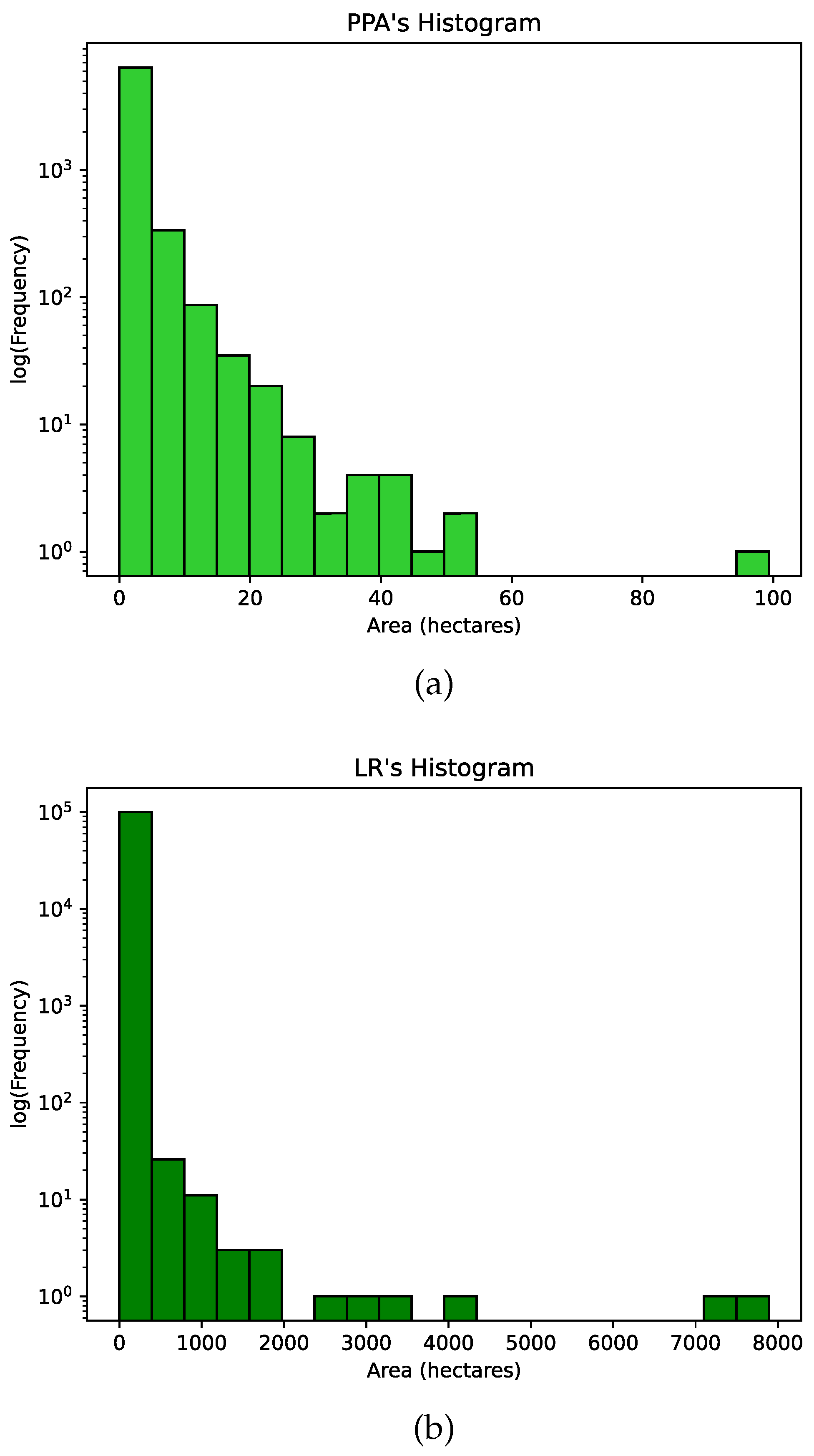

Figure 3 (a) shows the size distribution of the PPA. One highlight is the asymmetrical distribution to the left in the corresponding histogram, indicating a greater concentration of smaller fragments. In particular, the peak of the histogram reveals that most of the fragments have areas of less than 5 ha. This pattern suggests that areas with more irregular configurations could benefit from specific management interventions, such as implementing buffer zones to reduce edge effects. The asymmetry observed in the distribution of LR in

Figure 3 (b) is similar to the pattern found in PPAs, suggesting that these areas are larger. The histogram shows a higher concentration in fragments of up to 11 ha. Larger fragments, over

ha, are fewer in number, with decreasing frequencies as they increase in size. The logarithmic scale in the frequency highlights the contrast between the number of small and large fragments, reinforcing the predominance of the smaller ones.

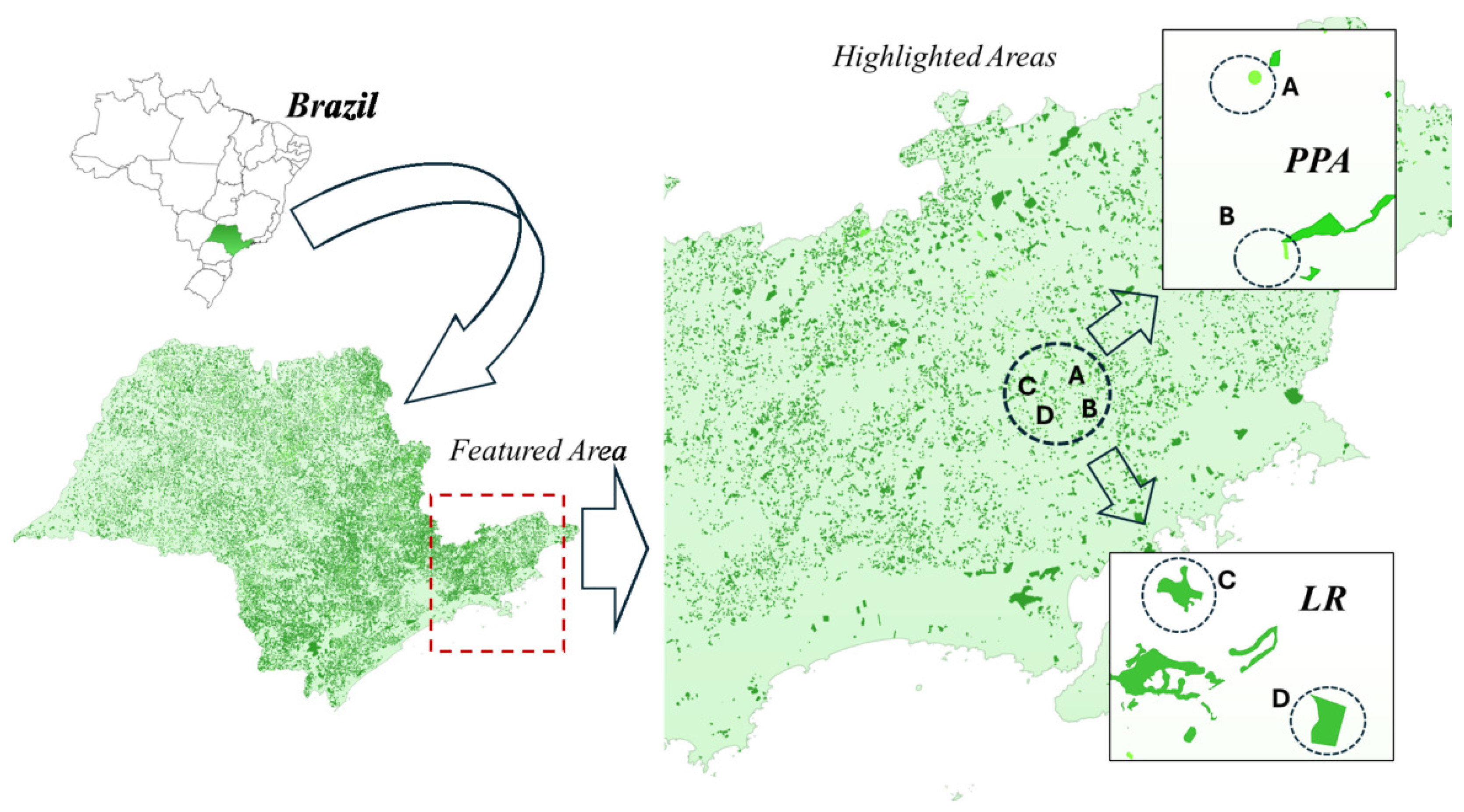

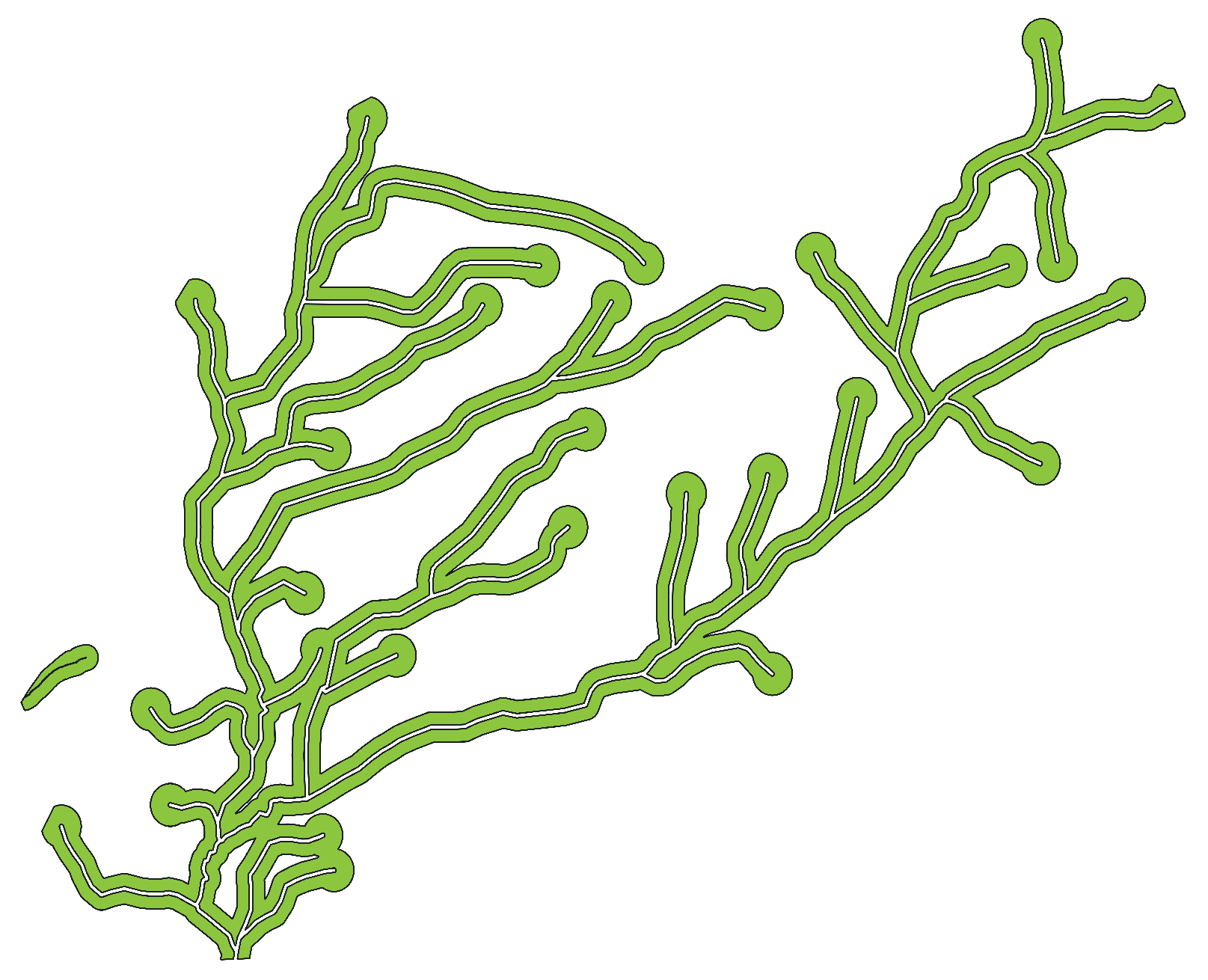

3.3. Geospatial Data Sample Results

Figure 4 presents examples of PPA and LR geospatial fragments, highlighted in

Figure 3 (a, b). They illustrate the spatial distribution of areas in São Paulo, highlighting the differences in shapes and sizes between PPA and LR. This spatial characterization is essential for the analysis and interpretation of the results. Computational refinement eliminated small redundant areas and corrected topological errors to ensure integrity and accuracy. We randomly selected all areas from this set. This process removed overlaps, corrected gaps, and eliminated invalid polygons, significantly reducing geometric inconsistencies. In this way, we improved the quality of the input data for mathematical modeling and subsequent metrics calculations. This preprocessing aimed to ensure the accuracy of the geometric complexity of the areas studied. The fragments of the selected study areas are presented in Tables

Table 4 and

Table 5, subdivided into two main categories (PPA and LR) so that we could monitor the procedures carried out during the information collection stage.

Table 5 presents two fragments of selected PPA (forms A and B), while Table

Table 5 shows two LR (forms C and D), displaying the geometric differences between the fragments. Each fragment presents its corresponding metrics and indexes, (

), (

), (

), and (

), to characterize the degree of fragmentation and spatial configuration of these sites.

Fragment A,

Table 5, has a total area of

ha and a perimeter of

meters. We can observe a highly regular shape, with a Circularity Index (

) close to 1, suggesting an almost circular appearance. This regularity is confirmed by the Edge Factor (

), indicating well-defined and simple edges, and by the Fractal Dimension (

), which reflects the average geometric complexity. The Compactness Index (

) also presents a geometry close to a circle with a

value close to 1.

However, Fragment B,

Table 5, presents a less regular shape, with a total area of

ha and a perimeter of

meters, with a Circularity Index (

), suggesting a more irregular shape. The Edge Factor (

) and the Fractal Dimension (

) indicate a more complex edge and a more fragmented geometric configuration than Fragment A, as also shown by the Compactness Index (

). It is interesting to observe large differences in the shapes of these fragments and how they are reflected in the metric values. In

Table 5, two fragments of selected LR can be observed. Similarly, the images highlight each fragment’s shape and perimeter, representing the geometric variability in the analyzed areas and their metrics.

The first fragment analyzed is an LR (Fragment C), with a total area of

ha and a perimeter of

meters (

Table 6). It is characterized by a highly irregular shape, with a Circularity Index (

), indicating low circularity and a more elongated shape. The Edge Factor (

) suggests a complex and fragmented edge, while the Fractal Dimension (

) reveals high geometric complexity, reflecting the irregularities of the edges and shape (

). Fragment D,

Table 6, in turn, is also an LR with a total area of

ha and a perimeter of

meters and has a more compact shape, with a Circularity Index (

), presenting a slightly more regular shape than Fragment C. However, there are still irregularities, such as the edge factor (

), the fractal dimension (

), and the compactness index (

), indicating moderate complexity and less complexity at the edges.

The data generated by the computational extractions and applied to the selected fragments were compiled and summarized in

Table 7. It presents a comparative relationship between the fragments considered and their diversity in sizes and shapes, revealing numbers related to their characteristics. Correlations can be observed between the contours and outlines of shapes and the quantitative representation of their geometric attributes. For instance, as in

, values approaching

correspond to shapes with circular characteristics.

Table 7 compares measured factors (area and perimeter) and calculated parameters (Circularity Index, Edge Factor, Fractal Dimension, and Compactness Index) for four fragments categorized as Permanent Preservation Areas (PPA) and Legal Reserves (LR). PPA generally exhibits higher circularity and compactness, with Fragment A being the most circular and compact (

,

) despite having a large perimeter relative to its small area. In contrast, LR shows greater variability in shape and complexity, as evidenced by their lower circularity and compactness indices but higher edge factors and fractal dimensions, with Fragment C being the most irregular. These differences highlight distinct spatial characteristics between PPA and LR, which are critical for understanding their ecological functions and guiding conservation efforts [

17].

3.4. Data Obtained from Shape Refinement in PPA and LR Metrics

The volume of data obtained and the geometric complexity of these areas justify the need for larger segmentations to ensure that the calculated metrics reflect the spatial characteristics of the set. Regarding PPA,

of the fragments, as shown in the histogram in

Figure 3 (a), are located below areas with around

to 5 ha. Since the histogram shows a logarithmic relationship, approximately 6 thousand properties (approximately

) are in this range. Therefore,

Table 8 shows the results of the area segments of these groups of fragments in three distinct size classes: (S) small fragments in the range up to

ha, (M) medium fragments of

to 20 ha and (L) large fragments equal to or greater than 20 ha, according to the histogram in

Figure 3 (a). In this way, it was possible to reconcile the distribution of areas to assess this set’s distribution better.

The segmentation results for the PPA are reproduced in

Table 9, which presents the statistical values of the metrics studied (

,

,

, and

), distributed according to the segmentation in

Table 9. The mean values, median, mode, variance, standard deviation, standard error, and other statistics for each set of classes are briefly demonstrated.

The segmentation of PPA areas into distinct size classes aimed to facilitate the analysis of their spatial distribution and associated metrics. Based on the histogram in

Figure 3 (a), the majority (approximately

) of PPA fragments have areas smaller than

ha (classified as small, S). A smaller proportion of fragments (about

) fall within the range of

to 20 hectares (medium, M), and only

are larger than 20 ha (large, L), as detailed in

Table 8. This classification allows for a more precise examination of how fragment size correlates with geometric metrics (

,

,

, and

). For instance, smaller fragments (S) typically exhibit lower compactness (

) and higher edge factors (

), reflecting their susceptibility to external pressures such as edge effects and microclimatic variations. In contrast, larger fragments (L) tend to have greater compactness and lower edge factors, suggesting better interior habitat conditions.

Table 9 provides statistical summaries of these metrics, including the mean, median, and variance across the three size categories. The segmentation and resulting metrics underscore the ecological importance of addressing the vulnerabilities of smaller fragments. Restoration efforts and the creation of ecological corridors could mitigate their exposure to edge effects, while large fragments should be prioritized for strict preservation to maintain their ecological integrity. It should also be recognized that the high proportion of smaller and irregular PPA fragments (those with sizes (

ha) highlights significant ecological challenges. These areas, characterized by low compaction (

) and high edge factors (

), are more susceptible to edge effects, such as increased exposure to sunlight, wind penetration, and temperature fluctuations. These conditions can degrade habitat quality, reduce biodiversity, and increase vulnerability to invasive species. In contrast, larger and more compact fragments (

ha) demonstrate greater ecological stability, as indicated by their higher compactness (

) and lower edge factors (

). These fragments are more suitable for interior-dependent species and more resilient to external pressures. However, the small number of these larger fragments (

) highlights the need for targeted conservation efforts to protect and expand these critical areas.

Moreover, the LR segmentation follows the same organization and the order of the values proposed for the PPA areas. In this case, the histogram in

Figure 3 (b) contains approximately

properties, corresponding to

of the total, within the range of up to 15 ha, and a smaller range indicated in the histogram contains properties of approximately 200 ha.

Table 10 shows the area segments in 3 distinct size classes: (S) small fragments in the range of up to 11 ha, (M) medium fragments from 11 to 70 ha, and (L) large fragments equal to or greater than 70 ha, according to the histogram in

Figure 3 (b).

Similarly, the results of the refinements for the LR are in

Table 10. The statistical results of the metrics studied (

,

,

, and

) are subdivided into classes, as described in

Table 10.

Table 11 presents the mean values, median, mode, variance, standard deviation, standard error, and other statistics for each set of classes.

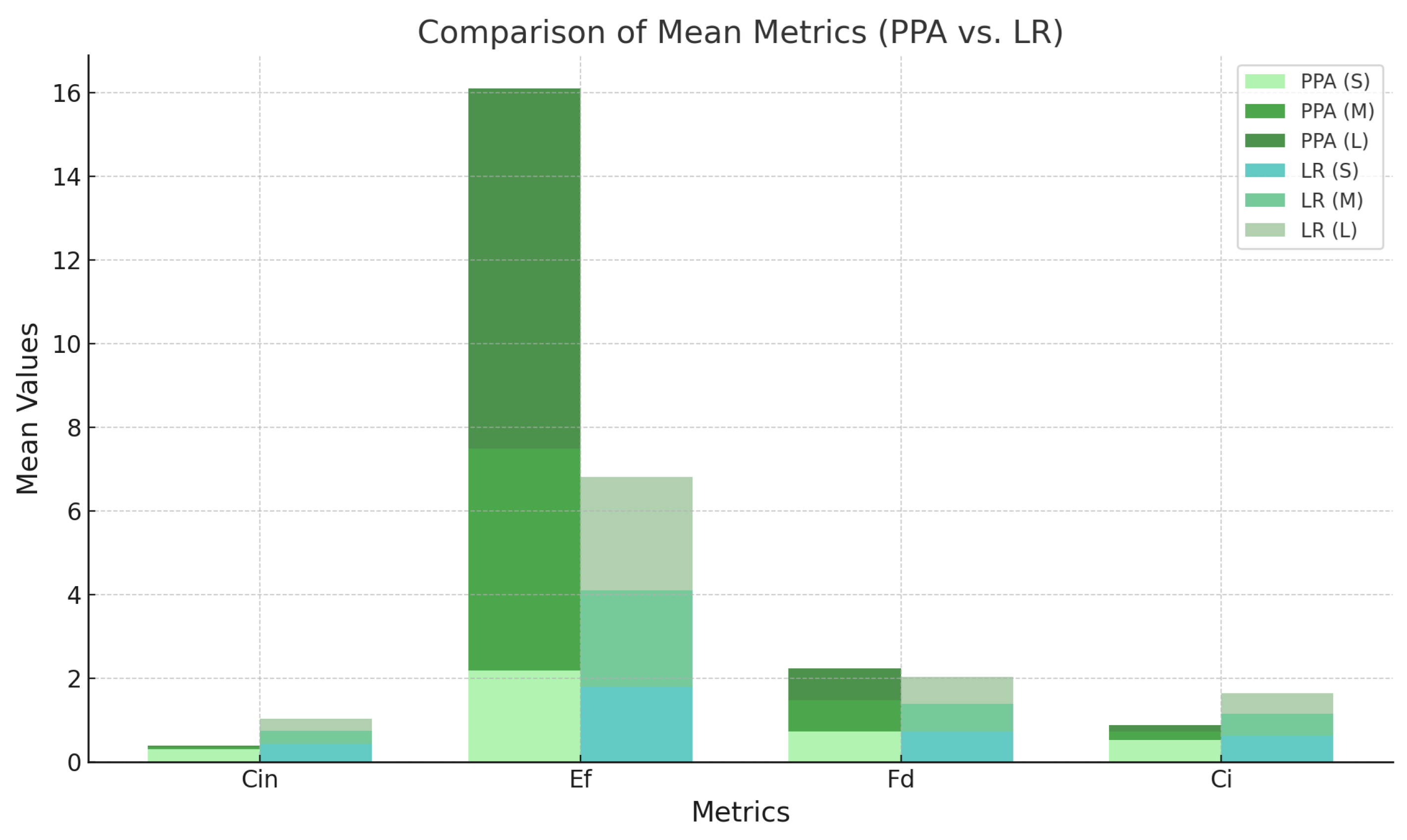

The analysis of the LR dataset highlights significant ecological patterns across the 3 size classes: Small (S), Medium (M), and Large (L),

Table 10. For the

, small fragments (mean

) exhibit higher variability, as reflected by their standard deviation

, indicating that these fragments are more prone to fragmentation effects. As shown in

Table 11, medium fragments

mean

show intermediate compactness, while large fragments

mean

maintain slightly lower compactness. Despite this, larger fragments benefit from their size, offering better ecological stability.

The

reveals heightened vulnerability for all size classes, with small fragments showing a mean

of

. This suggests a significant exposure to external pressures such as sunlight, temperature fluctuations, and invasive species. Medium fragments have the highest

mean of

, indicating they are the most susceptible to edge effects. Large fragments also exhibit considerable edge exposure

mean

, likely due to irregular shapes or high perimeter-to-area ratios, despite their size advantage. Regarding the

, small fragments (mean

) tend to have simpler, less complex boundaries, whereas medium fragments

mean

and large fragments

mean

display decreasing boundary complexity. This pattern reflects increasing regularity in shape as fragment size increases, which enhances ecological resilience. The

further underscores this trend, with small fragments (mean

) maintaining greater shape regularity. In contrast, medium

mean

and large

mean

fragments exhibit slightly lower compactness, possibly due to fragmentation or irregularity in shape.

Figure 5 shows the mean of each size and type for metrics.

Ecologically, small fragments are particularly vulnerable due to their high edge factors and moderate compactness, which expose them to habitat degradation, reduced biodiversity, and increased risk of invasive species [

17]. Restoration efforts, such as creating ecological corridors, are crucial to mitigate these vulnerabilities. Medium fragments, despite their larger size, face the highest edge-related pressures and require strategic preservation measures to enhance their stability. Large fragments, while relatively more stable due to their size, still experience significant edge effects, emphasizing the need for strict conservation and restoration practices to maintain their ecological integrity. Overall, the LR dataset highlights the critical importance of targeted interventions to preserve and restore habitat quality across all fragment sizes. The implications of these findings suggest that restoration strategies, such as creating buffer zones and ecological corridors, are essential to increase connectivity between smaller fragments and mitigate edge effects. Ecological functionality and landscape resilience can be significantly improved by integrating these approaches.

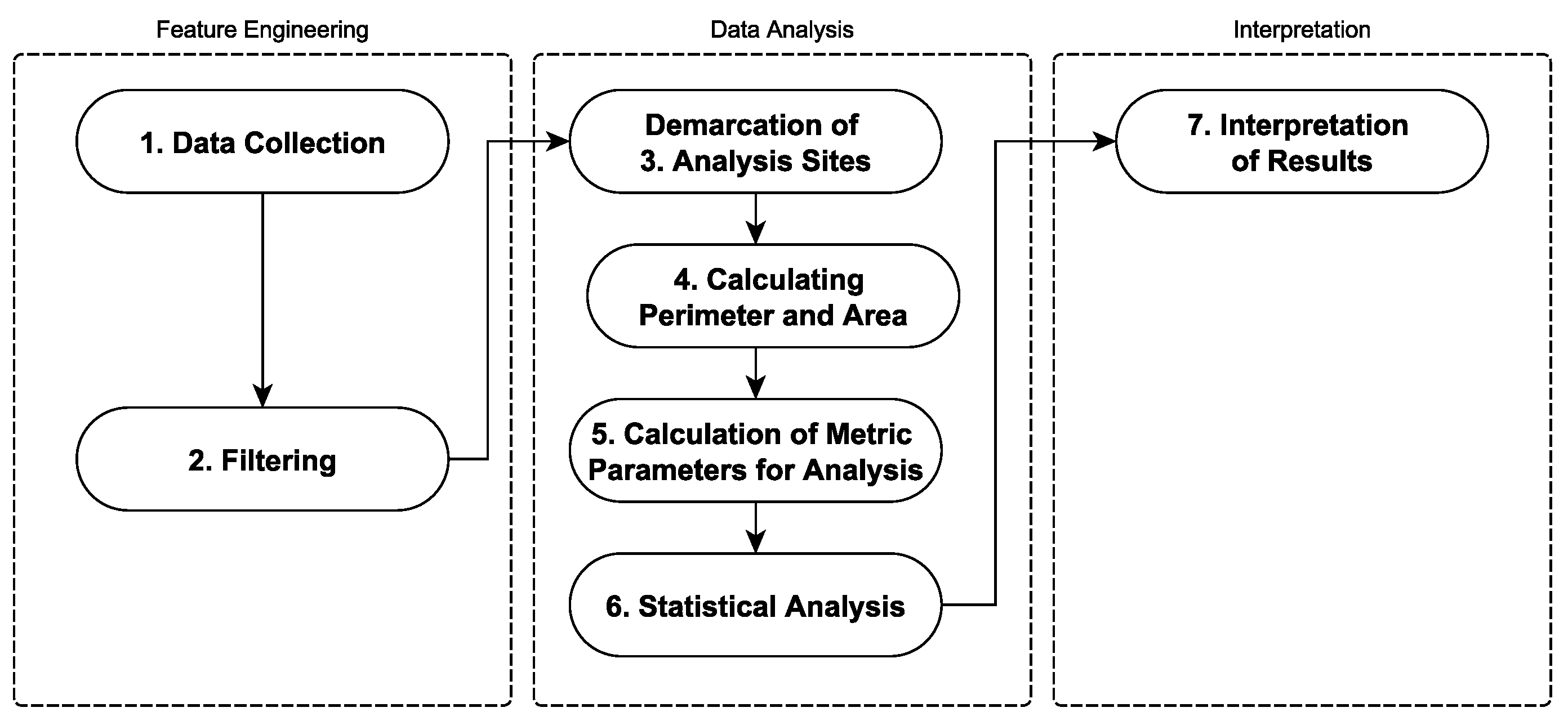

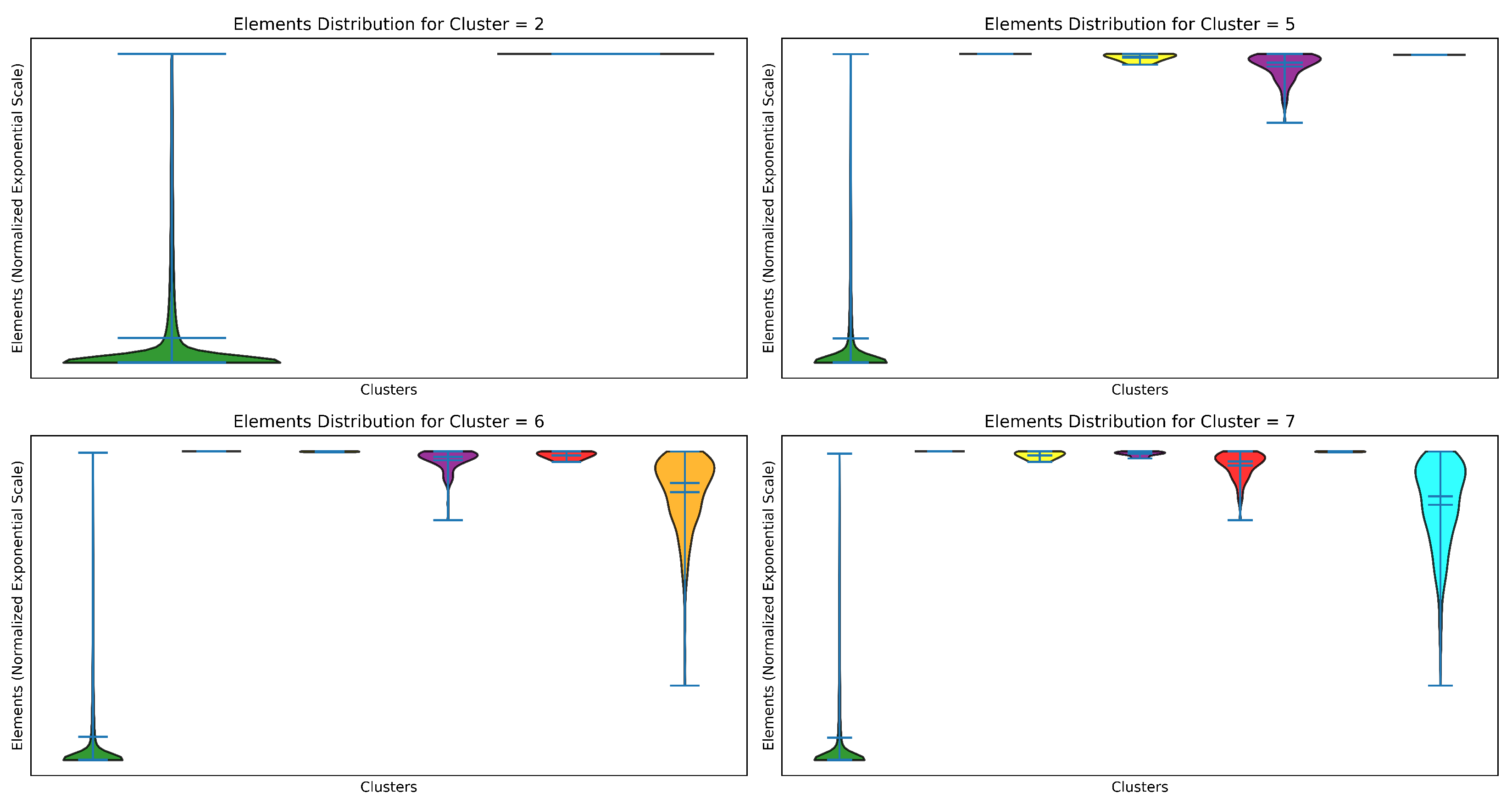

3.6. Data Segmentation Analysis

Cluster segmentation allows for accurately visualizing the structural distribution of PPA and LR. For example, by grouping small fragments into the same cluster, it is possible to evaluate how these fragments share characteristics of geometric irregularity and exposure to edges, which facilitates the identification of critical areas that require restoration. On the other hand, clusters formed by large and compact fragments provide evidence of areas to protect and maintain functional stability. This approach is in line with the citations already reported. Furthermore, applying clusters simplifies complex data sets by condensing thousands of fragments into analyzable groups. It is particularly useful in scenarios where the amount of raw data would make it difficult to identify clear patterns. In the case of PPA and LR, clusters effectively described spatial data variability and highlighted the structural differences between the two types of protected areas.

The

k-Means method is an unsupervised learning algorithm for data clustering. The algorithm separates the data into

k clusters, where

k is the number of user-defined groups. The algorithm groups the elements according to the objective of minimizing the sum of the squared Euclidean distances between the data points and the centroids of the clusters [

37]. Because of this, one of the first activities is normalizing the values. We used the metrics area, perimeter, radius, circle area,

,

,

,

latitude, longitude, and altitude as features. Also, we evaluate the value of

k varying from 2 to 10, as shown in

Figure 2. The results demonstrated that adopting a

k equal to 5 can group the data set to simplify the analysis without losing quality. Above this value, there were no significant differences in the results.

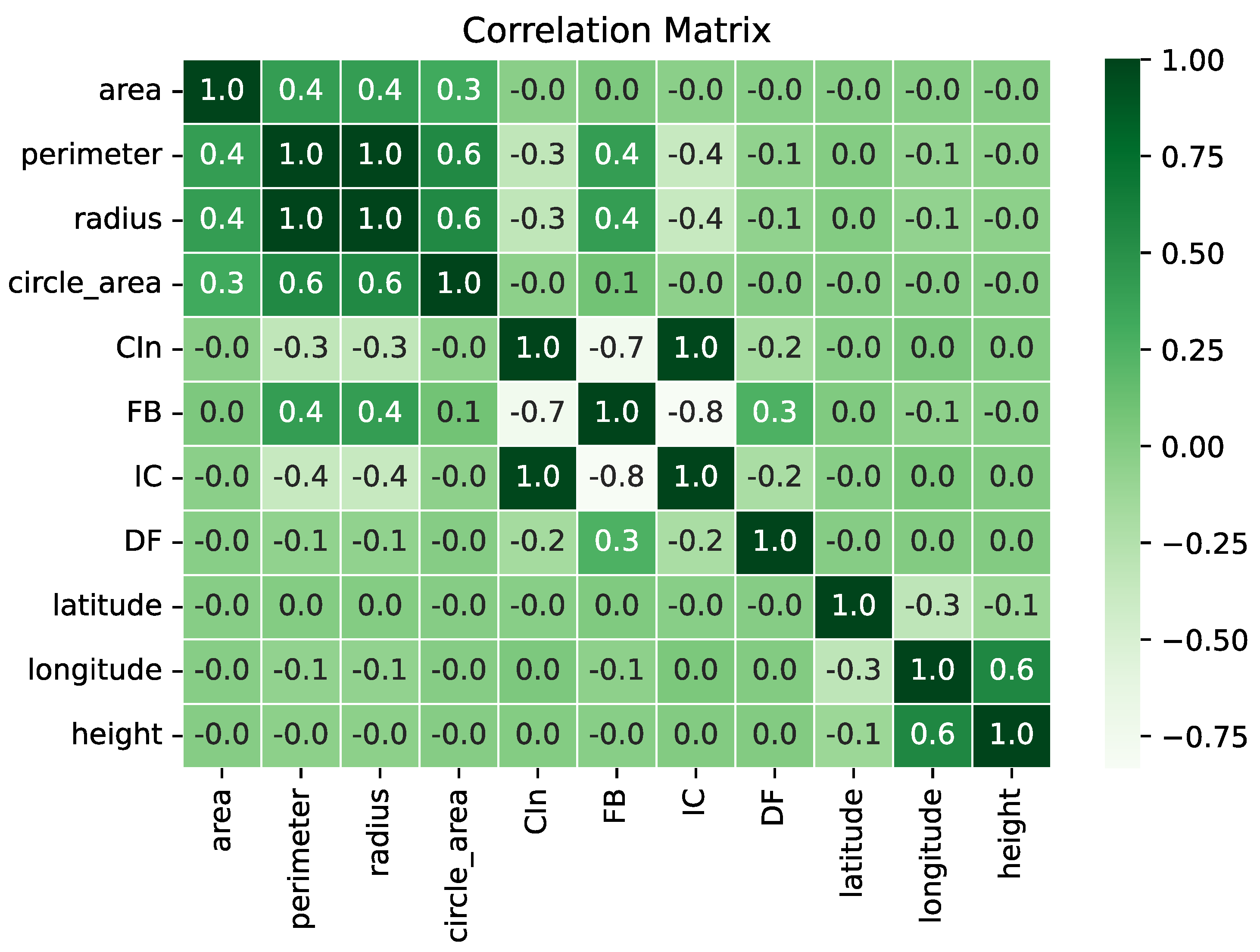

Figure 6 shows the resulting matrix that shows the correlation of the different variables of the system. Geospatial data from PPA and LR can reveal significant patterns in the configuration of these areas and provide insights into structural complexity and vulnerability.

Grouping variables based on their correlations allows for categorizing the fragments of the studied areas based on geometric and spatial attributes. The main idea is to group fragments that share similar patterns, facilitating the interpretation of spatial trends and allowing a targeted analysis of the vulnerabilities and potentialities of each group analyzed based on the metrics applied here. Each matrix cell (

Figure 6) represents a correlation coefficient that quantifies the relationship between two specific parameters. The circularity index (

), edge factor (

), fractal dimension (

), and compactness index (

) are the variables obtained from the parameters rotated in the simulation between the perimeter and area data. The values plotted in the matrix vary from (

to

), according to the color legend indicating the intensity and type of correlation. Values close to (

) indicate a strong positive correlation between the metrics, which means that as one metric increases, the other tends to increase as well, as shown in the positive correlation between the edge factor and the fractal dimension, which suggests that fragments with more complex edges tend to have more intricate spatial geometry.

Therefore, values close to () indicate a strong negative correlation, where an increase in one metric corresponds to a decrease in the other. The negative correlation between the compactness index and the fractal dimension shows that more compact areas tend to be less geometrically complex. In this case, values close to (0) are null, indicating a weak or non-existent correlation between the metrics, suggesting that one does not directly influence the other. The metrics , , , and have a low correlation with the primary metrics: area, perimeter, radius, and area of the circle. This low correlation between these metrics imposes that the formulas used to calculate the first metrics from the second metrics are independent and can be used to improve the classification into groups.

The metric analyses and geospatial data results highlight relevant patterns in the configuration and distribution of PPA and LR in São Paulo. The application of metrics Circularity Index (

), Edge Factor (

), Fractal Dimension (

), and Compactness Index (

) provided a quantitative basis for understanding the structural differences between these protected areas, revealing aspects related to fragmentation, geometric irregularity and exposure to external pressures. It allows for exploring the variation in the shapes and sizes of the fragments and evaluating structural differences that impact the functionality and continuity of the analyzed areas. PPA, generally associated with smaller and more irregular fragments, contrasts with LR, which presents larger and more compact fragments. The shape of an area directly influences its vulnerability to external factors and environmental disturbances, such as the invasion of exotic species and microclimatic changes [

13,

18,

39,

40].

Furthermore, these analyses of the size distributions between the study areas reveal marked differences in spatial continuity. The application of the metrics highlighted in this work can provide a multidimensional view of the configuration of fragmented forests. As pointed out by Blackman [

41], precision in the delimitation of polygonal areas and the use of metrics are essential in large-scale geospatial analyses, especially in scenarios involving high volumes of data and complex shapes, as in this study. The results presented in the structural characterization of PPA and LR also contribute to more detailed analyses that can be used in data-based environmental planning. These findings reinforce the need to integrate quantitative approaches in future studies, using advanced geoprocessing techniques to increase the representativeness and applicability of metrics in protected area management.

Thus, these results align with global efforts to achieve the

United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) 10, particularly Goal 15 (Life on Land), which emphasizes protecting and restoring terrestrial ecosystems. The methodologies and insights presented in this study can serve as a model for other tropical regions facing similar challenges in balancing agricultural expansion with biodiversity conservation. By applying these metrics, policymakers and researchers can contribute to global strategies for sustainable land use and enhanced ecosystem resilience.

3.7. Geospatial Data and Fragment Analysis in Large Scale

We analyzed statistical information relating to the total dataset. This may affect how the results work since the quantitative values impact the analysis of the metrics in decision-making regarding the spatial configuration, degree of fragmentation, and connectivity of the PPA and LR. These results indicate a significant distribution between the two types of areas studied, reflecting the structural differences imposed by the Brazilian Forest Code. This disparity highlights the challenge of managing smaller areas more susceptible to edge effects and fragmentation, a pattern typical of the Atlantic Forest, which originally covered around

of São Paulo’s territory. However, there was a drastic decline in forest cover due to accelerated industrialization and urban sprawl, especially in the 20th century. Forest fragments throughout the Atlantic Rainforest today in the São Paulo region tend to be smaller and not exceed 50 ha [

44,

45], while in Brazil, the Atlantic Rainforest reaches 100 ha [

46]. It poses significant challenges to ecological connectivity and environmental resilience.

Table 8 shows that the segmentation of PPA into small fragments (S) (less than

ha) concentrates lower values of Circularity Index (

) and high values of Edge Factors (

), indicating elongated shapes and greater exposure to edge effects in most cases. This combination suggests greater environmental vulnerability for this group of fragments with lower structural resilience. The high standard deviation in these indices for small fragments also reveals significant variability between fragments, indicating the coexistence of even more irregular shapes within this class. Medium-sized fragments (M) of

to 20 ha show a transition with a slight increase in

and a reduction in

, reflecting a worsening geometric regularity. In fragments larger than 20 ha (L),

values are higher, and

values are lower, indicating more irregular and less compact shapes, which are more susceptible to environmental disturbances. However, the low relative frequency of large fragments limits the functionality of ecological connectivity, perhaps reinforcing specific restoration and connectivity needs to minimize fragmentation. These results reinforce that the predominance of small fragments, representing more than

of the PPA, is a structural challenge for preservation, requiring concentrated connectivity and restoration strategies for degraded and altered areas.

Following the same logic, in

Table 10, which covers the metrics of the LR specifically, both the small fragments (S), smaller than 11 ha, and the medium fragments (M), intermediate values between 11 and 70 ha, do not seem to alter the metrics described in the cases of the PPA, but for the larger fragments (L), larger than 70 ha, high Fractal Dimension (

) values stand out, indicating high geometric complexity. This characteristic is generally associated with greater structural diversity within the fragments, which can benefit ecosystem functionality.

Table 10 summarizes the relationship between fragment size and spatial metrics, showing how increasing area affects shape metrics. As the size of an irregular fragment increases, there is a decrease in the

Index and an increase in

and

. It indicates that larger areas are more complex and less regular in geometric terms. The average

drops from

for small areas in the (S) group to

for the larger areas in the (L) group, showing that larger areas are less circular and have more irregular edges, as evidenced by the increasing

values (

for small areas to

for larger areas). This geometric complexity, represented by the

values (which range from

to

), requires greater computing power to accurately calculate the shape of the fragments, especially in larger areas where the variation in geometry can be significant.

Furthermore, the Compactness Index

in the medium and large fragments of the LR reveals more regular shapes than the PPA, contributing to greater structural stability. However, smaller fragments still show significant irregularities, indicating that these fragments may also be vulnerable to environmental disturbances. Moreover, the average value of the Edge Factor, also in the case of the smaller property areas in the group (S), is

, and for the larger property areas (L), it is

(

Table 10). The increase in the Edge factor suggests that the size of the regions is increasing, and the edges are becoming more complex and irregular. Homogeneous areas have

values close to 1 and exhibit defined boundaries. However, as the size increases, more fragmentation and complex edges are observed, and fragmented and complex forms are more integrated with topographical features or human activities.

Also, the fractal dimension indicates the complexity of the shape, which is a relationship between perimeter and area. The perimeter increases, and the scale of measurement is reduced. For small property areas of less than 11 ha, the asymmetry for

is

; for larger areas (L greater than 70), it is

(

Table 8). Complex shapes suggest larger areas and lower

values, increasing complexity. Irregular property areas or fragmentation along their edges can result in interactions with the environment. The compactness index compares the shape of an area with the most compact shape, similar to a circle. The average

for areas smaller than 11 ha is

, while for larger areas (

), the corresponding average value is

. The decrease in

indicates that larger areas tend to be less compact and dispersed in shape. The irregularity comes from increasing the shape’s size,

Figure 6. This holds regardless of the values found for the compactness index of the PPA.

3.8. Statistical Analysis of the set of Metrics and their Spatial Configuration

The implications of the presented statistical data suggest that PPA faces greater challenges in fulfilling their environmental protection functions due to the high number of small and irregular fragments. LR, on the other hand, shows a more robust spatial configuration, with a higher proportion of large and compact fragments, which favors their ability to contribute to conservation. The mean values, standard deviation, and variance highlighted validate their fragmentation and connectivity patterns. This statistical information improves the foundation and provides a basis for creating public policies that address these areas.

Overall, the calculated metrics (

,

,

,

) for the grouped cases offer a robust overview to support the spatial management of these areas, providing quantitative parameters for ongoing assessment and long-term strategic planning. The distribution of the data, marked by asymmetry and high kurtosis, indicates highly complex fragments and requires robust computational analysis. The presence of outliers, such as fragments with extreme

and

values, can influence the conclusions and require robust processing to guarantee the integrity of the results. Calculating metrics such as the Circularity Index (

), the Edge Factor (

), and the Fractal Dimension (

) requires high computational capacity, especially in larger and more complex areas. The tables show significant variations between the smaller and larger fragments, which indicates that fragmentation potentially affects connectivity due to the size and complexity of the areas. The high statistical variability, such as the asymmetry and kurtosis observed, reinforces the need for computational analysis. The high kurtosis (

for

in small areas) indicates the presence of outliers, fragments with circularity, or edge values that are different from the rest of the sample. These discrepant values represent extremely irregular or highly fragmented fragments, as shown in

Figure 7.

Assis (2008) [

51] describes fractal dimension and edge factor as excellent indicators for abnormal or irregular complex shapes. In these metrics (Edge Factor and Fractal Dimension), the values grow exponentially as the polygon tends to zero (

Table 10 and

Figure 7). The proposed fractal dimension reduces traditional errors in the data, demonstrating superior performance compared to the polygon. By definition, Mcgarigal & Marks (1995) [

9], Fractal Dimension ranges from 0 to 2; values greater than 2 indicate greater complexity, and in our metric data, results between moderate and high complexity (

to

) are observed.

Therefore, the metrics reveal challenges in the PPA in most protected areas,

of those with less than 11 ha, such as the Circularity indicator of

and the Edge indicator of

, which suggests increased edge effects and habitat fragmentation. The compactness index of

and the fractal dimension of

show moderate complexity and irregularities that affect management and conservation. There is an urgent need to integrate agriculture with environmental, social, and governance aspects to increase positive impacts in the real world [

53]. Landscape fragmentation can hinder the movement of species and connectivity between habitats. At the same time, the increase in vegetation patches (forest fragments) can favor the maintenance of viable populations, the provision of ecosystem services, and the recovery of PPA in nearby forest patches. The regular shape approximating a circle minimizes the perimeter relative to the area, thus reducing edge effects and decreasing vulnerability to external disturbances.

Moreover, LR usually has a homogeneous shape and a circularity index (

) that is consistently higher than the size of the PPA, with an increase of

(

) in LR. However, as the size of the area increases, in LR, there is a drop of approximately

in the value of

, while for PPA, this drop is

. PPA refers to forests that must be preserved on riverbanks, slopes, hilltops, and springs. They protect water resources, geological stability, biodiversity, and soil protection. An interesting dynamic inversion occurs with the PPA,

reduced as the area size increases. It should be measured in fragments and not in its entirety. Geoprocessing and spatial analysis of PPA and LR are essential for analyzing the landscape in detail, allowing us to qualify these areas’ fragmentation and connectivity, improving our understanding of geospatial dynamics and conservation needs [

54,

55].

The scatterplot of

Figure 8 visualizes clusters in a two-dimensional space derived from Principal Component Analysis (PCA), plotting both axes on a logarithmic scale. Each cluster, represented by a distinct color, highlights patterns of separation among data points based on their PCA-transformed features. Cluster 1 (green) appears to dominate the lower-left region, spreading widely along the horizontal axis, indicating a high density of points with smaller principal component values. Clusters 2 (blue) and 3 (purple) gradually transition toward higher values along both components, showing a clear progression. Cluster 4 (red) demonstrates significant concentration in the upper-right region, indicating a distinct group with higher principal component values, possibly outliers or a unique subset of the data. Clusters 5 (orange) and 6 (yellow) scatter in the higher principal component range, with fewer data points, suggesting sparse but distinct patterns. The logarithmic scale amplifies subtle variations, making this separation across clusters more pronounced. This plot effectively highlights the clustering results and their alignment with PCA dimensions.

3.9. Correlation Matrix and Clustering Results

The results obtained from the clustering revealed patterns in the fragments of the PPAs and LRs according to their metrics. The correlation matrix (

Figure 6) highlights important structural relationships between the spatial variables, area and perimeter, and the geometric metrics. It contains a lot of useful information about the attributes of the data sets related to each other in terms of direction and intensity. The metrics presented in the matrix have been duplicated on each axis (vertical and horizontal). The possible values range from

to 1. It indicates the different degrees of correlation. A value of 1 means that two variables are positively correlated, i.e., when one increases, the other also increases proportionally. On the other hand, a value of 0 indicates no linear correlation between the variables, suggesting that they have no apparent direct relationship. A value of

indicates a perfect negative correlation, where an increase in one variable is associated with a proportional decrease in the other.

The strong positive correlation between area and perimeter confirmed that larger fragments have proportionally greater perimeters, while smaller fragments have greater geometric complexity, especially in

. On the other hand, the negative correlations between

and

indicate that more regular shapes have less relative exposure to edges. These patterns reinforce the trends observed in the clustering, showing structural homogeneity within each group of fragments. Thus, the interpretation of the clusters, supported by these metrics, provides subsidies for specific management strategies, such as preserving regularity in larger fragments and reducing fragmentation in smaller fragments. These values are important for understanding the internal relationships of the data and how these relationships can influence the formation of clusters by

K-Means [

37]. For example, variables with a correlation close to 1 can provide redundant information, while uncorrelated or negatively correlated variables can provide complementary perspectives on separating groups. The correlation matrix, therefore, provides insight into the relationships between attributes and helps assess the quality and relevance of the variables used in the clustering process.

Based on the correlation matrix, it is possible to draw some conclusions. The correlation between Area and Circle Area is . As such, they are moderately directly correlated. It is also true for the radius and circle, which is and directly related to the circle. The and () metrics indicate that the other tends to decrease when one increases due to their formulas. One is similar to the inverse of the other. However, and (values equal to 1 correlate strongly due to their equations. One of the two metrics can be removed to use k-Means for segmentation. The Latitude and Longitude variables have a moderate negative correlation (approximately ). Longitude and altitude have a moderate positive correlation (). It may be related to the mountainous region of the state of São Paulo towards the coast, where the altitude drops to zero. It is due to the change in longitude. Latitude and altitude, however, have a practically zero relationship (). Another conclusion is that no metric (, , , or ) is related to its position or altitude.

,

, and

showed significant positive and negative relationships. In other words, they are directly or inversely linked. As expected, area, radius, perimeter, and circle area have moderate positive correlations. It confirms that they are directly related to similar physical properties. The division represented by clusters made it possible to identify homogeneous groups of fragments, which play an important role in analyzing spatial data by identifying homogeneous groups of fragments with similar characteristics. As explained, a

was used to segment the data set [

38].

The clusters formed did not, at first, provide any major conclusions. A large part of the data set, around , was grouped into a single fragment. However, the fragment with the fewest elements showed that this group represents the most distant elements in the set. In an extreme situation, this could even be characterized as an outlier. The use of k-Means was the first attempt in this direction. Perhaps the most significant result of this algorithm was the matrix that provided relevant information on the correlation between the variables studied.