Submitted:

19 April 2025

Posted:

21 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

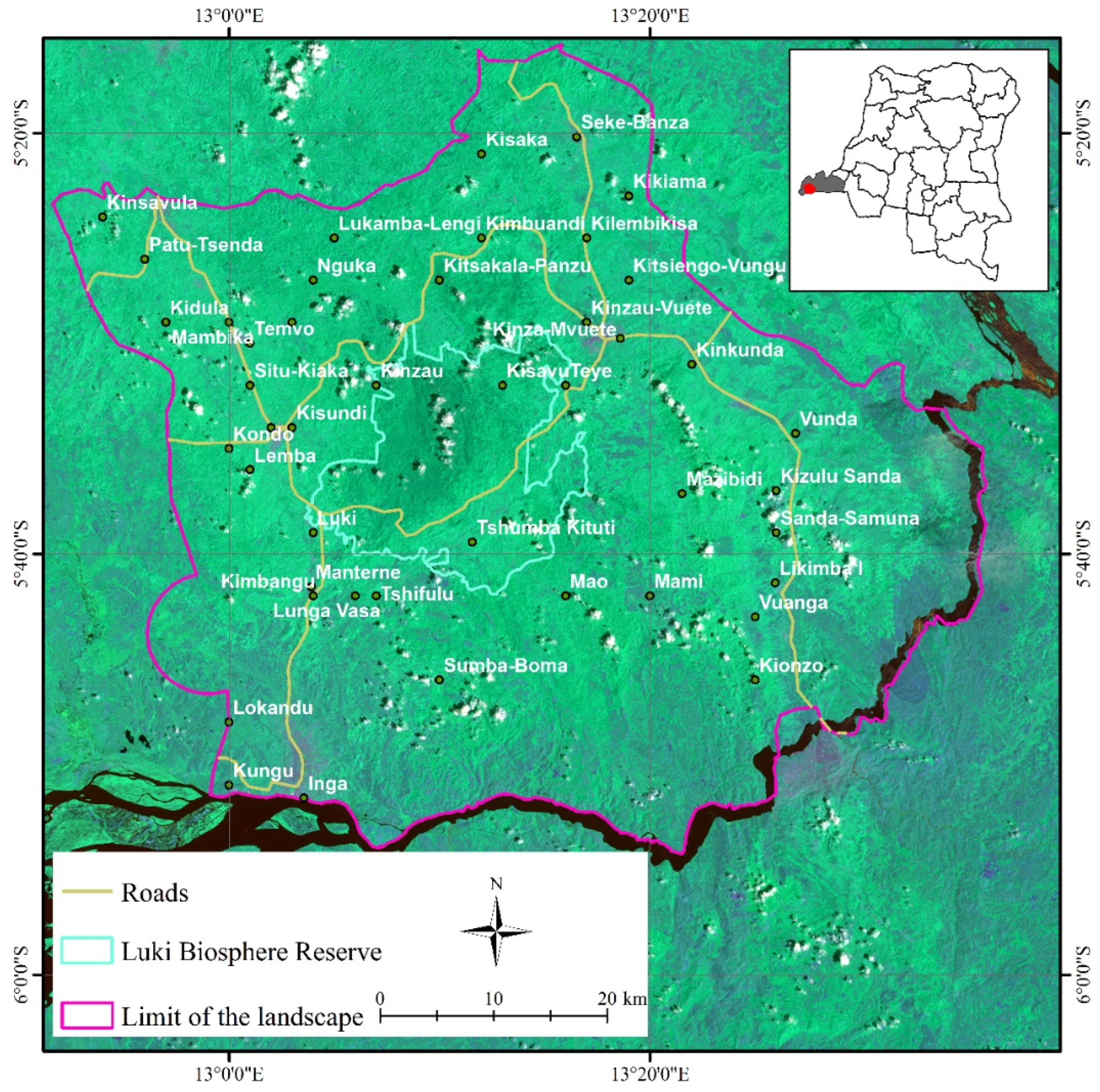

2.1. Characteristics of the Study Area

2.2. Satellite Data

2.3. Pre-Processing of Landsat Images

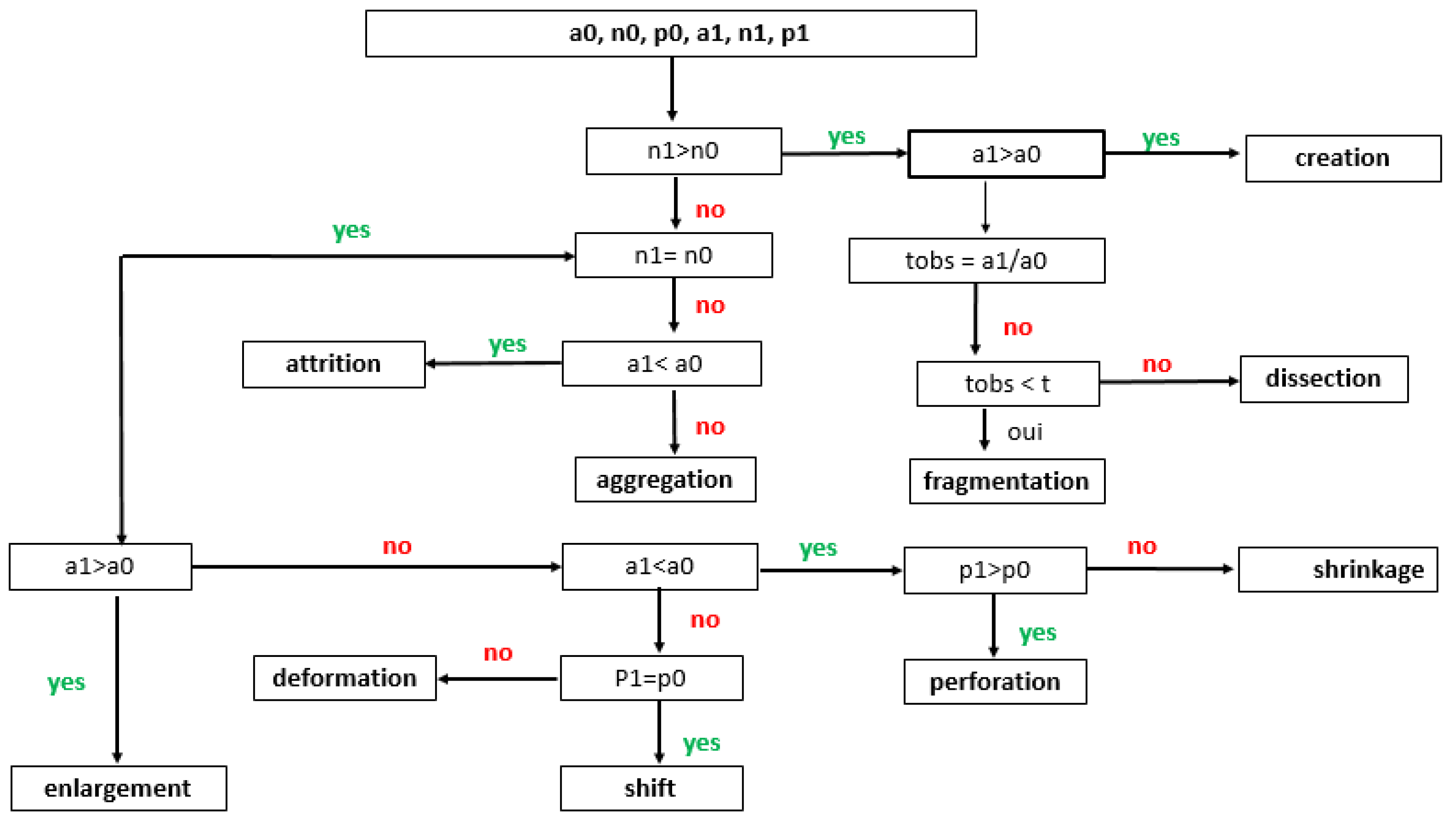

2.4. Assessment of Landscape Dynamics

3. Results

3.1. Accurate Classification and Mapping

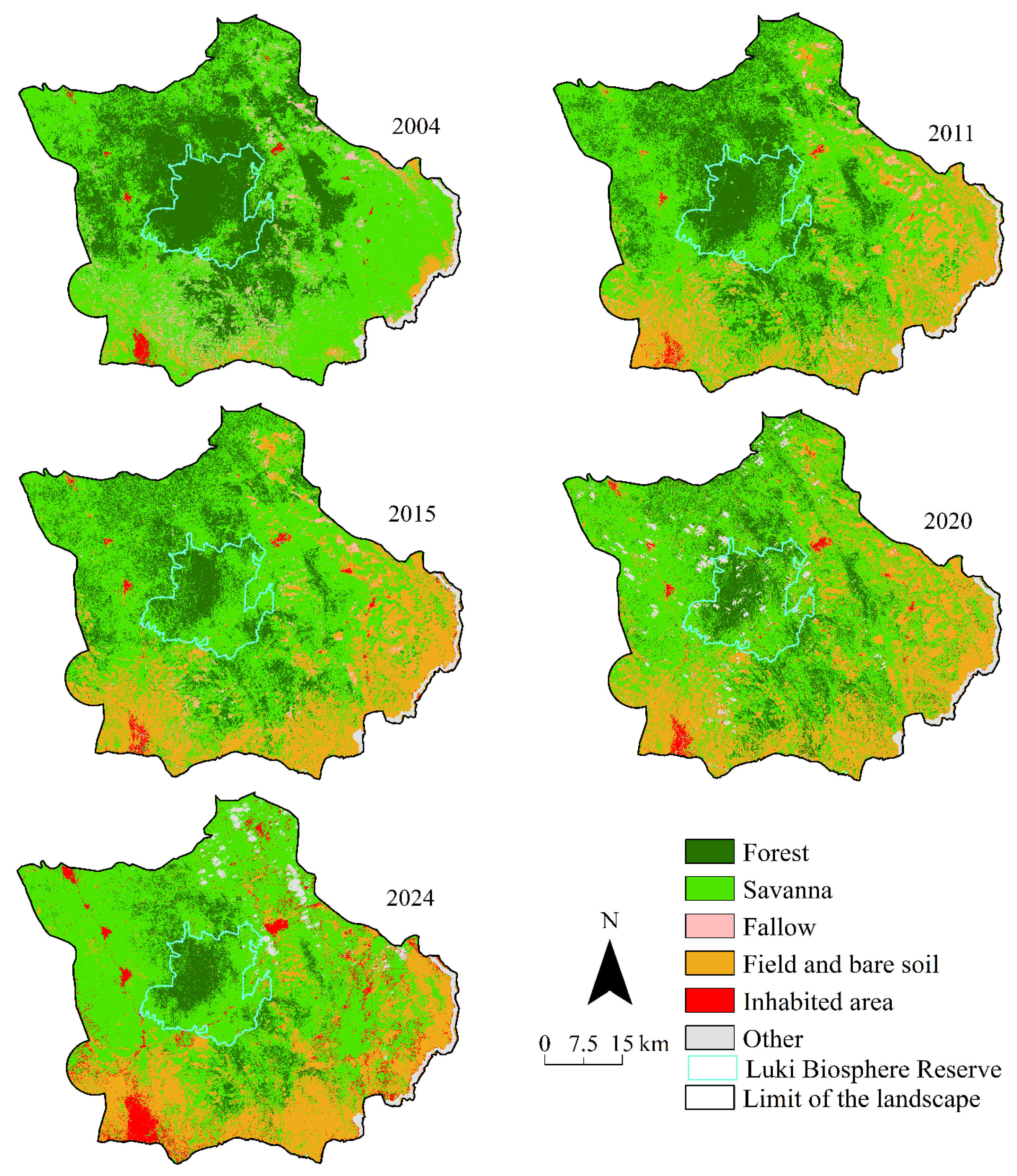

3.2. Landscape Composition Dynamics and Land-Use Change

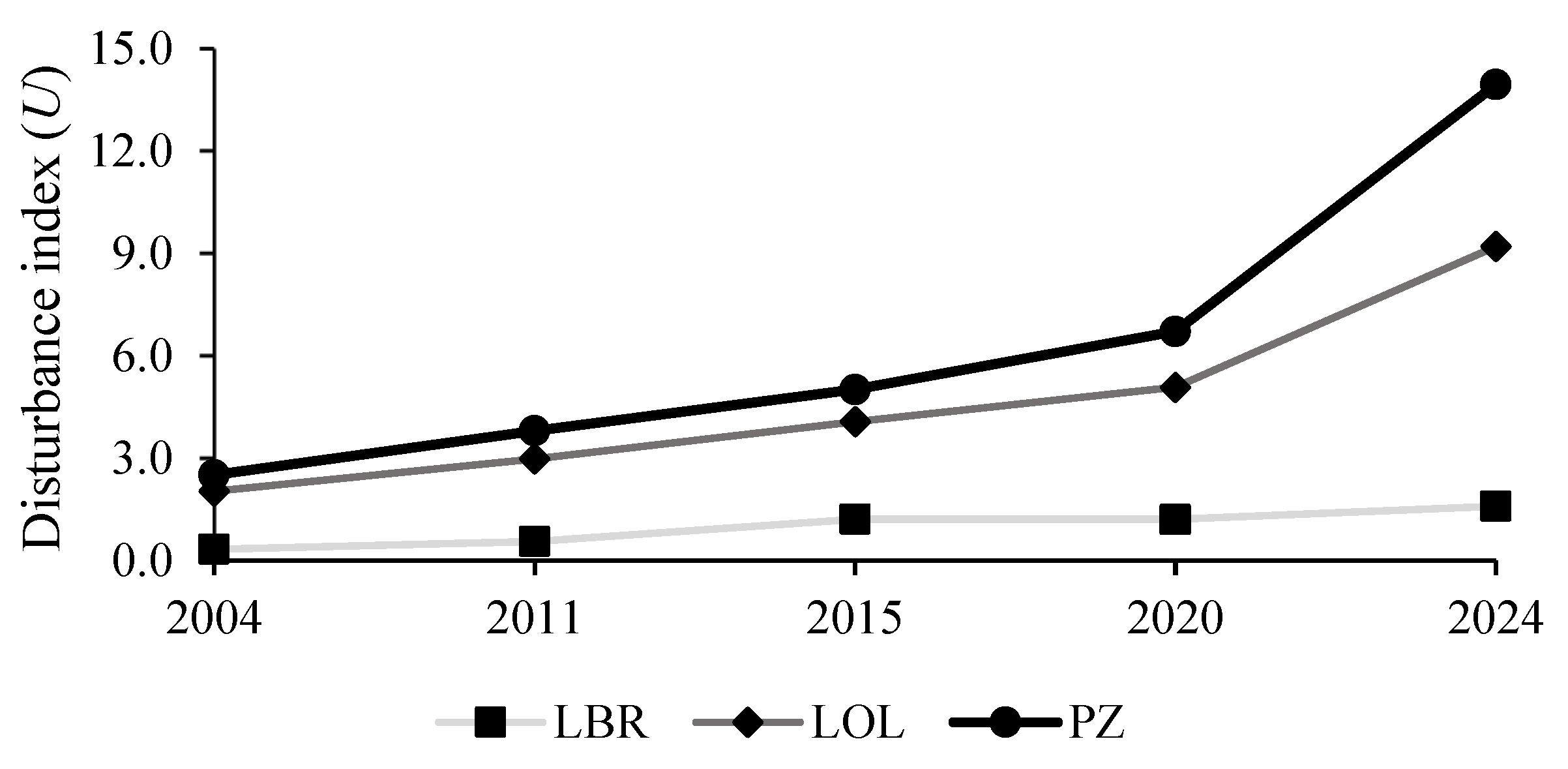

3.3. Spatial Structure of Caterpillar Habitats and Anthropization of the LBR Landscape

4. Discussion

4.1. Methodological Approach

4.2. A Landscape with Disturbed Edible Caterpillar Habitats

4.3. Implications of the Study Results and Practical Application

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Giradoux, p. La santé des écosystèmes: quelle définition ? Bull. Acad.Vet, 2022, France, 175: 120-139. https://www.persee.fr/doc/bavf_0001-4192_2022_num_175_1_15831.

- Amar, R. Impact de l’anthropisation sur la biodiversité et le fonctionnement des écosystèmes marins. Exemple de la Manche-mer du nord. Vertigo 2010, 8 : 1-13. https://www.erudit.org/en/journals/vertigo/2010-n8-vertigo3983/045528ar/abstract/.

- Teyssèdre, A. Les services écosystémiques, notion clé pour explorer et préserver le fonctionnement des (socio)écosystèmes. Regard R4 SFE2 2010. sfecologie.org. Available online : https://sfecologie.org/wp-content/uploads/2010/10/R4-Teyssedre-2010.pdf (Accessed on 02.01.2025). [CrossRef]

- Bitamba, F.J.; Bazirukize, K.E.; Zikama, N.L.; Ntahondi, H.A. Impact des activités humaines sur les écosystèmes forestiers du groupement Kamuronza en territoire de Massisi, Nord-Kivu. Bull. Inf. Tour. et env. 2012, 122-132. https://www.istougoma.ac.cd/pdf/publication/640f295d51fd2.pdf.

- Brun, L. E.; Sinasson, G.; Azihou, A.F.; Gibigaye, M.; Tente, B.A.H. Perceptions des facteurs déterminants de dégradation de la flore des zones humides dans la commune d’Allada, Sud – Bénin. Afri. sci. 2020, 16(4) : 52 – 67. http://afriquescience.net/PDF/16/4/5.pdf.

- FAO; PNUD. La situation des forêts dans le monde 2020. Forêts, biodiversité et activités humaines. Rome 2020. Fao.org. Available online : (Accessed on 02.01.2025). [CrossRef]

- Global Forest Watch. Global Annual Tree Cover Loss. Global Forest Watch, 2023. https://www.globalforestwatch.org/dashboards/global/.

- IPBES. Summary for policymakers of the global assessment report on biodiversity and ecosystem services of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services 2019. 39p https://www.dropbox.com/.

- Vancutsem, C.; Achard, F.; Pekel, J-F.; Vieilledent, G.; Carboni S.; Simonetti, D.; Gallego, J.; Aragão, L.E.O.C.; Nasi, R. Long-term (1990–2019) monitoring of forest coverchanges in the humid tropics. Sci. Adv. 2021, 7(10) : 1-21. [CrossRef]

- Dalimier, J.; Achard, F.; Delhez, B.; Desclée, D.; Bourgoin, C.; Eva, H.; Gourlet,-Fleury, S.; Hansen, M.; Kibambe, J.P.; Mortier, M.; Ploton, P.; Réjou-Méchain, M.; Vancutsem, C.; Langner, A.; Sannier, C.; Ghomsi, H.; Jungers, Q.; Defourny, P. Répartition des types de forêts et évolution selon leur affectation. Etat des forêts de l’Afrique centrale, UC-Louvain-Geomatics, Louvain, Belgique 2022 ; pp. 1-36. https://www.cifor-icraf.org/publications/pdf_files/Books/Etat-des-forets-2021.pdf.

- Molinaro, G.; Hansen, M.C.; Patapov, P. Forest cover dynamics of shifting cultivation in the Democratic Republic of Congo: remote sensing-based assessment for 2000-2010. Environ. Res. Lett. 2015, 10, 094009. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/281671562.

- Molinaro, G.; Hansen, M.C.; Patapov, P.; Tyukavina, A.; Stehman, S. Contextualizing landscape-scale forest cover loss in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) between 2000 and 2015. Land 2020, 9(1) :23. https://www.mdpi.com/2073-445X/9/1/23.

- Kyale, Koy, J.; Wardell, D. A.; Mikwa, J.-F.; Kabuanga, J. M.; Monga, Ngonga, A.M.; Oszwald, J.; Doumenge, C. Dynamique de la déforestation dans la Réserve de biosphère de Yangambi (République démocratique du Congo) : variabilité spatiale et temporelle au cours des 30 dernières années. BFT 2019, n° 341 : 15-28.

- Tingu, C.; Mathunabo, A. Analyse de la situation socio- économique et alimentaire des ménages des provinces du Nord et Sud Ubangi en RDC. Rev. Mar. Sci. Agron. Vét. 2019, 7: 203-211. https://www.agrimaroc.org/index.php/Actes_IAVH2/article/view/683/739.

- Semeki, N.J.; Linchant, J.; Quevauvillers, S.; Kahindo, M. J-M.; Lejeune, P.; Vermeulen, C. Cartographie de la dynamique de terroirs villageois à l’aide d’un drone dans les aires protégées de la République démocratique du Congo. BFT 2016, 330(4) : 70-83. https://revues.cirad.fr/index.php/BFT/article/view/31320.

- Nyembo, F.; Mertens, B.; Cherif, M.; Inza, K. Menaces d’origine anthropique et Habitat de Pan Paniscus dans La reserve naturelle de Sankuru, en République démocratique du Congo. Eur. Sci. J. 2021, 16 (21) : 290-309. https://hal.science/hal-03285049/document.

- Cirezi, C. N.; Tshibasu, E.; Lutete, E.; Mushagalusa, A.; Mugumaarhahama, Y.; Ganza, D.; Karume, K.; Michel, B.; Lumbuenamo, R.; Bogaert, J. Fire risk assessment, spatiotemporal clustering and hotspot analysis in the Luki biosphere reserve region, Western DR Congo. Trees For. People 2021, vol 5, 22p. [CrossRef]

- Cirezi, C.N.; Bastin, J.F.; Tsibasu, E.; Lonpi, T.E.; Chuma, G.B.; Mugumaarhahama Y.; Sambieni K.R.; Karume K-C.; Lumbuenamo S.R.; Bogaert J. Contribution of human induced fires to forest and savannah land conversion dynamics in the Luki biosphere reserve landscape, western Democratic Republic of Congo. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2022, 43(17) :6406-6429. [CrossRef]

- Semeki, N.J.; Tongo, Y. M. Livelihoods Means and Local Populations Strategies of the Luki’s Biosphere Reserve in Democratic Republic of Congo. IJNREM 2019, 4(2): 42-49.https://article.sciencepublishinggroup.com/pdf/10.11648.j.ijnrem.20190402.12.pdf.

- Kaleba, C.S.; Sikuzani, U.Y.; Sambieni, K.R.; Bogaert, J.; Munyemba, K.F. Dynamique des écosystèmes forestiers de l’arc cuprifère katangais en République Démocratique du Congo. Causes, transformations spatiales et ampleur. Tropicultura 2017, 35(3) : 192-202. https://popups.uliege.be/2295-8010/index.php?file=1&id=1266.

- Sikuzani, U.Y.; Malaisse, F.; Kaleba, C.S.; Munyemba, K.F.; Bogaert, J. Rayon de déforestation autour de la ville de Lubumbashi (Haut-Katanga, RD. Congo), Synthèse. Tropicultura 2017, 35(3) : 215-221. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/320258544.

- Opelele, O.M.; Ying, Y.; Wengi, F.; Chen, C.; Kachaka, S.K. Examining land use/land cover and its prediction based on a multilayer perception Markov Approach in the Luki biosphere reserve, Democratic Republic of Congo. Sustainability 2021a, 13 (12):68-98. [CrossRef]

- Opelele, O.M.; Ying,Y.; Wenyi, F.; Lubalega, T.; Chen, C.; Kachaka, S.K. Analysis of the impact of land-use/land-cover change on land-surface temperature in the villages withing the Luki biosphere reserve. Sustainability 2021b, 13 (20):11242. https://www.mdpi.com/2071-1050/13/20/11242.

- Opelele, O.M.; Ying, Y.; Wenyi, F.; Lubalega, T.; Chen, C.; Kachaka, S.K.C. Impact of land use change on tree diversity and aboveground carbon storage in the Mayumbe Tropival forest of the Democratic Republic Congo. Land 2022, 11:787. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/360914210.

- Kwidja, D.Y; Fonteyn, D.; Semeki, N.J.; Mvuezolo, N.M.; Poulain, P.; Lonpi, T.E.; Vermeulen, C. État des populations des mammifères terrestres dans la Réserve de Biosphère de Luki (République démocratique du Congo). Biotechnol. Agron. Soc. Environ. 2023, 27(4), 13p. https://popups.uliege.be/1780-4507/index.php?id=20430.

- Lonpi, T.E.; Sambieni, K. R.; Messina, N. J-P.; Nsevolo, M.P.; Boyombe, L.L.; Kasali, J.L.; Khasa D.; Malaisse F.; Bogaert J. Diversity and availability of edible caterpillar host plants in the Luki biosphere reserve landscape in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Trees For. People 2024, 18, 100719, 12p. [CrossRef]

- Lonpi, T.E. RDC: comment les atteintes à la biodiversité affectent les habitudes alimentaires. The Conversation, 2022. https://theconversation.com/en-rdc.

- Lonpi, T. E.; Sambieni, K. R.; Khasa, D.; Bogaert, J.; Kasali, J. L.; Huart, A.; Konda, K. M. A.; Malaisse, F. Les chenilles consommées dans la région de la réserve de biosphère de Luki en République démocratique du Congo : acteurs, connaissances locales et pressions. BFT 2023, 355 : 21-34.

- Bomolo, O.; Niassy, S.; Chocha, A.; Longanza, B.; Bugeme, D.M.; Ekesi S. & Tanga C.M. Ecological diversity of edible insects and their potential contribution to household food security in Haut-Katanga Province, Democratic Republic of Congo. Afri. J. of Ecol. 2017, 55(4): 640-653. https://www.gov.uk. [CrossRef]

- Looli B.L.; Dowiga, B.; Bosela, O.; Salamu, P.; Manzenga, J.C.; Posho, B.; Mabossy-Mobouna, G.; Latham, P.; Malaisse, F. Techniques de récolte et exploitation durable des chenilles comestibles dans la région de Yangambi, R.D. Congo. Geo-Eco-Trop 2021, 45(1): 113-129. https://www.geoecotrop.be/uploads/publications/pub_451_10.pdf.

- Koua, K. A. N.; Bamba, I.; Barima, Y. S. S.; Kouakou, A. T. M.; Kouakou, K.A.; Sangne, Y.C. Echelle spatiale et dynamique de la forêt classée du Haut-Sassandra (Centre Ouest de la Côte d’Ivoire) en période de conflits. Rev. Env. et Bio. 2017,-PASRES 2 (1) : 54 - 68.

- Mama, A.; Bamba, I.; Sinsin, B.; Bogaert, J.; De Cannière, C. Déforestation, savanisation et développement agricole des paysages de savanes-forêts dans la zone soudano-guinéenne du Bénin. BFT 2014, 322(4) : 65-75. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/321638655.

- Nyangue, N.M. Participation des communautés locales et gestion durable de forêts : cas de la réserve de la biosphère de Luki en République Démocratique du Congo. Thèse de Doctorat en Sciences forestières 2014, Université Laval Québec, 205 p. Available online :https://corpus.ulaval.ca/jspui/bitstream/20.500.11794/25349/1/30892.pdf (Accessed on 15.09.2024).

- Desclee, D.; Michel, B.; Trefon, T. Enquête et étude de diagnostic des capitaux et stratégies d’existence des ménages dépendant de ressources de la Réserve de Biosphère de Luki en République Démocratique du Congo. Tropicultura 2018, 36(3): 492-505. http://www.tropicultura.org/text/v36n3/492.pdf.

- Lubini, A. La végétation de la réserve de biosphère de Luki au Mayombe (Zaïre). Opera Botanica Belgica 1997, 10: 155 p. ISBN 90-72619-33-1/ ISSN 0775-9592.

- Kergomard, C. Pratique des corrections atmosphériques en télédétection : utilisation du logiciel 5S-PC. Eur.J.Geogr. 1996, document 181. http://journals.openedition.org/cybergeo/1679 ;

- Nkwunonwo, U.C. Land use/Land cover mapping of the Lagos Metropolis of Nigeria using 2012 SLC-off Landsat ETM+ Satellite Images. Int. J. Sci. Eng. Res. 2013, 4(11) : 1217–1223. https://www.ijser.org/.

- Sikuzani, U.Y.; Mukenza, M.M.; Malaisse, F.; Kazaba, K.P.; Bogaert, J. The spatiotemporal changing dynamics of Miombo deforestation and illegal human activities for forest fire in Kundelungu National park, Democratic Republic of the Congo. Fire 2023, 6(5):174. https://www.mdpi.com/2571-6255/6/5/174.

- Barima, Y.S.S.; Barbier, N.; Bamba, I.; Traore, D.; Lejoly, J.; Bogaert, J. Dynamique paysagère en milieu de transition forêt-savane ivoirienne. BFT 2009, 299(1) : 15-25. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/323203516.

- Mama, A.; Sinsin, B.; De Cannière, C.; Bogaert, J. Anthropisation et dynamique des paysages en zone soudanienne au Nord du Bénin. Tropicultura 2013, 31(1) :78-88. http://www.tropicultura.org/text/v31n1/78.pdf.

- Kabuanga, M.J.; Guguya, B.A.; Okito, N.E.; Maestripieri, N.; Saqalli, M.; Rossi, V.; Iyongo, W.M.L. Suivi de l’anthropisation du paysage dans la région forestière de Babagulu, République Démocratique du Congo. Vertigo 2020, 20(2) : 1-27. https://www.erudit.org/en/journals/vertigo/2020-v20-n2-vertigo06186/1079241ar.pdf.

- Skupinski, G.; Tran, D.B.; Weber C. Les images satellites Spot multi-dates et la métrique spatiale dans l’étude du changement urbain et suburbain: le cas de la basse vallée de la Bruche (Bas-Rhin, France). EJG, 2009. Systèmes, Modélisation, Géostatistiques, document 439. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/49133802.

- Mukenza, M.M.; Muteya, K.H.; Nghonda, N.D.; Sambieni, K.R.; Malaisse, F.; Kaleba, C.S.; Bogaert, J.; Sikuzani, U.Y. Uncontrolled Exploitation of Pterocarpus tinctorius Welw. and Associated Landscape Dynamics in the Kasenga Territory: Case of the Rural Area of Kasomeno (DR Congo). Land 2022, 11, 1541. [CrossRef]

- O’Neill, R.V.; Krumme, J.R.; Gardner, R.H.; Sugihara, G.; Jackson, B.; DeAngelist, D.L. Indices of landscape pattern. JLECOL 1988, 1(3) : 153-162. https://turnerlab.ibio.wisc.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/43/2021/12/ONeill1988LE.pdf.

- Bogaert, J.; Ceulemans, R.; Salvador-Van, E.D. Decision Tree Algorythm in landscape transformation. JEM 2004, 33 :62-73. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/8932193_.

- De Haulleville, T.; Rakotondrasoa, O.L.; Rakoto, R.H.; Bastin, J.F.; Brostaux, Y.; Verheggen, F.J.; Rajoelison, L.G.; Malaisse, F. ; Bogaert, J. et al. Fourteen years of anthropization dynamics in the Uapaca bojeri Baill. forest of Madagascar. Landsc. Ecol. Eng. 2018, 14:135–14. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/322764337.

- Kabulu, D.J.; Bamba, I.; Munyemba, K.F.; Defourny, P.; Vancutsem, C.; Nyembwe, N.S.; Ngongo, L.M.; Bogaert, J. Analyse de la structure spatiale des forêts du Katanga. Ann.for.Sci.Agro. 2008, 1(12) :12-18. http://bakasbl.org/news/doc/177.pdf.

- Mohamed, M.E.; Abdelghani H.; Mohamed E.F. Apport de la télédétection et du SIG au suivi de la dynamique spatiotemporelle des forêts des massifs numidien de Jbel Outka (Rift central, Maroc). GOT 2017, 1(11): 171-187. [CrossRef]

- Mcgarigal, K. FRAGSTATS Help. Department of Environmental Conservation, University of Massachusetts, Amherst, 2015. www.Researchgate.net. Available online:http://www.umass.edu/landeco/research/fragstats/documents/fragstats.help.4.2.pdf (Accessed on 15.02.2024).

- Mama, A.; Oumorou, M.; Sinsin, B.; De Canniere, C.; Bogaert, J. Anthropisation des paysages naturels des aires protégées au Bénin : cas de la forêt classée de l’Alibori Supérieur (FC-AS). AJIRAS 2020, ISSN 2429-5396. www.american-jiras.com.

- Girou, D.; Deschamps, N.; Delorme, M. Apports et limites de la télédétection aérienne et satellitale pour la gestion des milieux en Guyane : exemple du zonage écologique et humain de la région de Saül. JATBA 40ème bulletin 1998, 1(2) : 423-432. https://www.persee.fr/doc/jatba_0183-5173_1998_num_40_1_3683.

- Mihai, B.; Savulescu, I.; Sandric, I.; Oprea, R. Application de la télédétection des changements de l’étude de la dynamique de la végétation des monts de Becegi (Carpates méridionales, Roumanie). Télédétection 2006, 6(3) :215-231. https://www.academia.edu/2920144/.

- Soro, G.; Ahoussi, K.E.; Koudio, K.E.; Soro, D.T.; Oulare, S.; Saley, B.M.; Soro, N.; Biemi, J. Apport de la télédétection à la cartographie de l’évolution spatiotemporelle de la dynamique de l’occupation du sol dans la région des lacs (centre de la Côte d’Ivoire). Afrique Science 2014, 10(3) :146-160, ISSN 1813-548X. http://www.afriquescience.info/docannexe.php?id=3925.

- Koh, L.P.; Wich, S.A. Dawn of Drone Ecology: Low-Cost Autonomous Aerial Vehicles for Conservation. Tropical Conservation Science 2012, 5 : 121-132. [CrossRef]

- Vermeulen, C.; Lejeune, P.; Lisein, J. ; Sawadogo, P.; Bouché, P. Unmanned aerial survey of elephants. PLoS ONE 2013, 8: e54700. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/235605299.

- Linchant, J.; Lisein, J.; Semeki, J.; Lejeune, P.; Vermeulen, C. Are unmanned aircraft systems (UAS) the future of wildlife monitoring? A review of the accomplishments and challenges. Mammal Review 2015, 45: 239-252. https://www.oipr.net/storage/publications/1674725676.pdf.

- Andrieu, J.; Mering C. Cartographie par télédétection des changements de la couverture végétale sur la bande littorale ouest-africaine: exemple des Rivières du Sud du delta du Saloum au Rio Geba. Télédétection 2008, 8 (2) : 93-118. https://shs.hal.science/halshs-00388170/.

- Nicet, J-B.; Porcher, M.; Pennober, G.; Mouquet, P.; Alloncle, N.; et al. Aide pour la réalisation et la commande de cartes d’habitats normalisées par télédétection en milieu récifal sur les territoires français. Guide de mise en œuvre à l’attention des gestionnaires. Document de synthèse IFRECOR 2016. https://hal.science/hal-01467027/.

- Kilensele, M.T. Limites des stratégies de conservation forestière en République Démocratique du Congo. Cas de la réserve de biosphère de Luki. Thèse de doctorat, faculté des sciences institut de gestion de l’environnement et d’aménagement du territoire, Université Libre de Bruxelles, Bruxelles, Belgique, 2015. www.academia.edu. Available online : https://www.academia.edu/85872793/Limites (Accessed on 15.09.2024).

- Bwazani, B.J.; Meniko To Hulu, J.P.P.; Bogaert, J. Anthropisation et modélisation prospective des paysages forestiers dans la Province de la Tshopo, RD Congo « Cas de la Réserve de Biosphère de Yangambi et de la Réserve Forestière de Masako ». Mémoire de Master de l’Université de Kinshasa, Kinshasa, RD Congo 2023. Researchgate.net. Available online : https://www.researchgate.net/publication/375756179 (Accessed on 15.09.2024).

- Abdou, K.I.; Abasse, T.A.; Massaoudou, M.; Rabiou, H.; Soumana, I.; Bogaert, J. Influence des pressions anthropiques sur la dynamique paysagère de la réserve partielle de faune de Dosso (Niger). IJBCS 2016, 13(2):1094-1108. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/334884515.

- Inoussa, M.M.; Mahamane, A.; Mbow, C.; Saadou, M.; Yvonne, B. Dynamique spatio-temporelle des forêts claires dans le Parc national du W du Niger (Afrique de l’Ouest). JLE 2011, 22(2) : 108-116, 10.1684/sec.2011.0305.

- Toyi, M.S.S.; Andre, M.; Sikuzani, Y.U.I.; Bogaert, J.; Sinsin, B. Trente ans d’anthropisation des paysages forestiers au sud du Bénin (Afrique de l’Ouest). AJOL 2019, 23 (2) : 183-197, ISSN 1659 – 5009. https://orbi.uliege.be/bitstream/2268/289325/1/toyi_asa_2019.pdf.

- Razafimahefa, A. L. Impact de la fragmentation d’habitat chez Adansonia rubrostipa dans la région Menabe. Mémoire de master en biologie végétale, université d’Antananarivo, Madagascar, 2016. Protectedareas.mg. Available online : https://protectedareas.mg/ (Accessed on 15.09.2024).

- Bouko, B.S.; Dossous, P. J.; Amadou, B.; Sinsin, B. Exploitation des ressources biologiques et dynamique de la forêt classée de la Mekrou au Benin. ESJ 2016, 12(36) : 228-244.

- Dejace, D. Perspectives de mise en place de la Régénération Naturelle Assistée pour l'amélioration de jachères apicoles, en périphérie de la Réserve de Biosphère de Luki (RDC). Mémoire de Master en bioingénieur, Université de Liège, Gembloux, Belgique, 2019. www.ulb-coopération.org. Available online : https://www.ulb-cooperation.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/ (Accessed on 15.09.2022).

- Boissier, O. Impact des pressions anthropiques sur les communautés de frugivores et la dispersion des graines en forêt guyanaise. Museum national d'histoire naturelle, Paris, France, 2012.www.researchgate.net. Available online : https://www.researchgate.net/ (Accessed on 15.10.2024).

- Cateau, E. Reponse des coleopteres saproxyliques apteres aux perturbations anthropiques des forets et des paysages. Thèse de doctorat, université de Toulouse, France, 2016. Available online : https://hal.inrae.fr/tel-02796092v2/file/Cateau_Eugenie.pdf (Accessed on 15.09.2024).

- Alongo, S.; Kombele, F.; Bogaert, J. Etude des relations sol-plante après la fragmentation de la forêt par l’agriculture itinérante sur abattis brûlis dans la région de Yangambi, R.D. Congo. JAECOLER 2022, 1(2) : 74-83. https://laecolie.org/wp-content/uploads/2023.

| Land use | Characteristics | ROI* | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Forests | Forests are habitats for edible caterpillars in the study area, with a high diversity of host trees (Lonpi et al., 2024). They include primary forest, secondary forest (plantations and savannahs under protection for natural regeneration) and forest galleries. | 30 | |

| Savannahs | Savannahs were considered to be grassy savannahs and shrub savannahs of anthropogenic origin, regularly subjected to bush fires and without fencing. The caterpillars consumed by the population in the study area are not dependent on the grasses of grassy savannahs. Also, repeated bushfires in anthropogenic savannahs do not allow the regeneration of forest forage species for the caterpillars consumed by the population. | 36 | |

| Fallow land | Fallows are pioneer vegetation that recolonizes bare soils. Like forests, fallow lands in the study area are a preferred habitat for caterpillar feeding populations in the LBR landscape. | 39 | |

| Fields and bare soil | These are areas where cassava, groundnuts, maize, and other crop plants are grown. According to the regional agricultural calendar, from mid-May to mid-October, there is a long dry season marked by field preparation operations (tree felling, clearing, and burning) leaving the soil devoid of plant cover. Because of their agricultural vocation and the need for charcoal, generally, the fields in the study area have no woody vegetation providing fodder for edible caterpillars, as trees are systematically felled during field preparation. | 59 | |

| Inhabited areas | Inhabited areas are settlements that were mostly established before and during the creation of the LBR. More recent settlements have been established over the last 30 years as a result of population growth. These settlements are surrounded by tree vegetation characterized by low diversity and irregularity of edible caterpillar host species (Lonpi et al., 2024). | 36 | |

| Image classification results:2004 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Forests | Savannahs | Fallow lands | Fields and bare soils | Inhabited areas | Others | |||

| Ua | 100.0 | 95.0 | 82.5 | 97.5 | 72.5 | 100.0 | ||

| Pa | 95.2 | 95.0 | 97.1 | 68.4 | 72.5 | 100.0 | ||

| Overall accuracy 2004 : 90.90% | ||||||||

| Image classification results : 2011 | ||||||||

| Ua | 85.1 | 91.9 | 97.4 | 98.4 | 100.0 | 100.0 | ||

| Pa | 94.0 | 86.0 | 98.4 | 94.9 | 100.0 | 100.0 | ||

| Overall accuracy: 94.91% | ||||||||

| Image classification results : 2015 | ||||||||

| Ua | 100.0 | 100.0 | 93.5 | 91.7 | 94.9 | 100.0 | ||

| Pa | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 91.7 | 89.2 | 100.0 | ||

| Overall accuracy: 97.47% | ||||||||

| Image classification results : 2020 | ||||||||

| Ua | 100.0 | 95.7 | 100.0 | 95.9 | 97.9 | 100.0 | ||

| Pa | 97.9 | 95.9 | 100.0 | 97.9 | 97.9 | 100.0 | ||

| Overall accuracy 2020 : 93.89% | ||||||||

| Image classification results : 2024 | ||||||||

| Ua | 100.0 | 96.7 | 98.0 | 93.9 | 94.9 | 100.0 | ||

| Pa | 98.6 | 92.6 | 100.0 | 94.7 | 98.6 | 100.0 | ||

| Overall accuracy2024 : 95.70% | ||||||||

| Changes in % | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2004 | 2011 | 2015 | 2020 | 2024 | 2011-2004 | 2015-2011 | 2020-2015 | 2024-2020 | 2024-2004 | ||||||

| Km2 | % | Km2 | % | Km2 | % | Km2 | % | Km2 | % | ||||||

| Luki Biosphere Reserve | |||||||||||||||

| Forest | 283.14 | 84.51 | 215.67 | 64.38 | 151.53 | 45.2 | 145.45 | 43.39 | 128.56 | 38.37 | -20.14 | -19.17 | -1.81 | -5.01 | -46.13 |

| Savannah | 49.44 | 14.76 | 115.88 | 34.59 | 180.25 | 53.77 | 158.54 | 47.29 | 196.59 | 58.68 | 19.82 | 19.18 | -6.47 | 11.39 | 43.93 |

| Fallow | 2.11 | 0.63 | 0.43 | 0.13 | 0.33 | 0.1 | 0.15 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.01 | -0.5 | -0.02 | -0.05 | -0.03 | -0.61 |

| Field & bare soil | 0.05 | 0.02 | 2.44 | 0.73 | 2.53 | 0.75 | 14.83 | 4.43 | 6.32 | 1.9 | 0.71 | 0.02 | 3.67 | -2.53 | 1.87 |

| Inhabited area | 0.25 | 0.08 | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.18 | 0.06 | 0.63 | 0.2 | 2.17 | 0.64 | -0.06 | 0.04 | 0.13 | 0.46 | -0.07 |

| Other | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.55 | 0.16 | 0.39 | 0.12 | 15.59 | 4.65 | 1.28 | 0.4 | 0.16 | -0.04 | 4.53 | -4.26 | 0.38 |

| Total | 335.00 | 100 | 335.00 | 100.00 | 335.00 | 100.00 | 335.00 | 100.00 | 335.00 | 100 | |||||

| Peripheral zone | |||||||||||||||

| Forest | 878.40 | 277 | 655 | 20.62 | 521.55 | 16.42 | 398.00 | 12.52 | 206.00 | 6.48 | -7.03 | -4.2 | -3.89 | -6.04 | -21.17 |

| Savanna | 1937.58 | 61 | 1650 | 51.94 | 1698.83 | 53.48 | 1666.70 | 52.46 | 1856.00 | 58.42 | -9.06 | 1.53 | -1 | 5.96 | -2.57 |

| Fallow | 160.40 | 5.04 | 57.28 | 1.8 | 39.29 | 1.23 | 8.72 | 0.27 | 0.71 | 0.02 | -3.24 | -0.56 | -0.96 | -0.25 | -5.02 |

| Field & bare soil | 121.63 | 3.82 | 764 | 24.05 | 847.12 | 26.66 | 962.49 | 30.29 | 828.40 | 26.1 | 20.22 | 2.61 | 3.63 | -4.21 | 22.25 |

| Inhabited area | 29.51 | 0.93 | 17.22 | 0.54 | 29.25 | 0.92 | 33.73 | 1.06 | 188.00 | 5.9 | -0.38 | 0.37 | 0.14 | 4.84 | 4.97 |

| Other | 49.00 | 1.54 | 33.3 | 1.05 | 41.01 | 1.29 | 107.42 | 3.4 | 97.97 | 3.08 | -0.49 | 0.24 | 2.09 | -0.29 | 1.54 |

| Total | 3177.00 | 100.00 | 3177.00 | 100.00 | 3177.00 | 100.00 | 3177.00 | 100.00 | 3177.00 | 100 | |||||

| Landscape | |||||||||||||||

| Forest | 1162.41 | 33.1 | 871.16 | 24.8 | 673.36 | 19.16 | 543.56 | 15.47 | 334.70 | 9.5 | -8.28 | -5.61 | -3.69 | -5.94 | -23.54 |

| Savanna | 1987.91 | 56.55 | 1766.7 | 50.26 | 1879.8 | 53.5 | 1826.00 | 51.96 | 2053.77 | 58.4 | -6.29 | 3.24 | -1.53 | 6.48 | 1.89 |

| Fallow | 162.62 | 4.63 | 57.746 | 1.64 | 39.619 | 1.12 | 8.87 | 0.25 | 0.75 | 0.02 | -2.98 | -0.51 | -0.87 | -0.23 | -4.6 |

| Field & bare soil | 121.79 | 3.501 | 766.82 | 21.81 | 849.85 | 24.2 | 977.55 | 27.82 | 835.02 | 23.76 | 18.35 | 2.37 | 3.63 | -4.05 | 20.29 |

| Inhabited area | 29.78 | 0.84 | 17.27 | 0.5 | 29.443 | 0.83 | 34.37 | 1 | 189.92 | 5.4 | -0.35 | 0.34 | 0.14 | 4.42 | 4.55 |

| Other | 49.26 | 1.40 | 34.058 | 1 | 41.517 | 1.2 | 123.18 | 3.5 | 99.60 | 3 | -0.43 | 0.21 | 2.32 | -0.67 | 1.43 |

| Total | 3514.00 | 100 | 3514.00 | 100.00 | 3514.00 | 100.00 | 3514.00 | 100.00 | 3514.00 | 100 | |||||

| Spatial scales | Forest | Savannah | Fallow land | Inhabited area | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a | n | a | n | a | n | a | n | |

| LBR2004 | 283.14 | 864 | 49.45 | 2366 | 2.11 | 311 | 0.25 | 42 |

| Peripheral zone2004 | 878.40 | 18804 | 1937.58 | 19872 | 160.40 | 32379 | 29.51 | 2246 |

| Landscape2004 | 1162.41 | 19561 | 1987.91 | 22107 | 162.62 | 32730 | 29.78 | 2289 |

| LBR2011 | 215.67 | 1440 | 115.88 | 3373 | 0.43 | 89 | 0.04 | 13 |

| Peripheral zone2011 | 655.00 | 18729 | 1650.95 | 17647 | 57.28 | 8866 | 17.82 | 1770 |

| Landcape2011 | 871.16 | 20011 | 1766.7 | 20820 | 57.74 | 8945 | 17.27 | 1781 |

| LBR2015 | 151.53 | 3123 | 180.25 | 3102 | 0.33 | 74 | 0.2 | 33 |

| Peripheral zone2015 | 521.55 | 26999 | 1698.83 | 15598 | 39.29 | 7011 | 29.25 | 1495 |

| Landscape2015 | 673.36 | 29900 | 1879.8 | 18526 | 39.61 | 7082 | 29.44 | 1526 |

| LBR2020 | 145.45 | 3601 | 158.54 | 3778 | 0.15 | 112 | 0.63 | 160 |

| Peripheral zone2020 | 398.00 | 39268 | 1666.70 | 15834 | 8.72 | 7353 | 33.73 | 3057 |

| Landscape2020 | 543.56 | 42631 | 1826.00 | 19427 | 8.87 | 7466 | 34.37 | 3213 |

| LBR2024 | 128.56 | 3022 | 196.59 | 3844 | 0.04 | 49 | 2.17 | 725 |

| Peripheral zone2024 | 206.1 | 18248 | 1856.00 | 20386 | 0.7 | 569 | 188.00 | 29870 |

| Landscape2024 | 334.7 | 21125 | 2053.77 | 24103 | 0.75 | 618 | 189.92 | 30631 |

| Luki Biosphere Reserve | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2004 | 2011 | 2015 | 2020 | 2024 | |

| Forest | 80.68 | 54.96 | 32.43 | 30.41 | 32.65 |

| Fallow | 0.05 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Savanna | 6.77 | 18.14 | 38.88 | 30.95 | 50.47 |

| Inhabited area | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.07 |

| Peripheral zone | |||||

| Forest | 11.74 | 8.16 | 2.61 | 0.91 | 0.70 |

| Fallow | 0.10 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Savanna | 55.45 | 43.30 | 47.34 | 44.58 | 52.61 |

| Inhabited area | 0.40 | 0.15 | 0.25 | 0.39 | 1.28 |

| Landscape | |||||

| Forest | 22.99 | 7.74 | 3.92 | 2.48 | 4.24 |

| Fallow | 0.09 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Savanna | 51.13 | 25.28 | 28.67 | 26.63 | 52.77 |

| Inhabited area | 0.36 | 0.08 | 0.14 | 0.21 | 1.16 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).