Submitted:

21 January 2025

Posted:

21 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

As global populations age, supporting older adults to age in place—remaining in their homes and communities—emerges as a critical challenge. This study investigates how interior architectural design can integrate human-centered, biophilic, and technology-driven principles with sustainable strategies to enhance the autonomy, safety, and well-being of older adults. Employing a multi-phase methodology, the research synthesizes literature on aging, interior architecture, and technology to establish a comprehensive framework. This framework emphasizes user participation, nature-inspired design, assistive technologies, and adaptable spatial planning. Key findings reveal actionable strategies, such as integrating biophilic elements like daylighting and greenery, employing user-friendly smart technologies, and incorporating universal design features like adjustable countertops and slip-resistant flooring. The proposed framework aligns design interventions with the physical, cognitive, and emotional needs of older adults, promoting environments that foster independence and dignity. Ultimately, the study underscores the importance of interdisciplinary collaboration in creating adaptable, sustainable, and empowering living spaces that enhance quality of life for aging populations.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Background and Significance

1.2. Aim and Scope of the Paper

2. Methodology

2.1. Research Design

- Literature Review:

- 2.

- Conceptual Framework Development:

2.2. Data Collection

- Database Selection:

- 2.

- Selection Criteria:

- o Articles that addressed design or architectural solutions for older adults.

- o Empirical or theoretical contributions to aging in place.

- o Practical interventions relevant to human-centered design, biophilia, or technology integration.

- 3.

- Screening and Quality Assessment (QA):

2.3. Data Analysis

- Coding and Categorization:

- 2.

- Methodology Referencing:

- 3.

- Cross-Comparison and Consensus:

2.4. Ethical Considerations

3. Literature Review

3.1. Aging in Place: Concepts and Gerontological Foundations

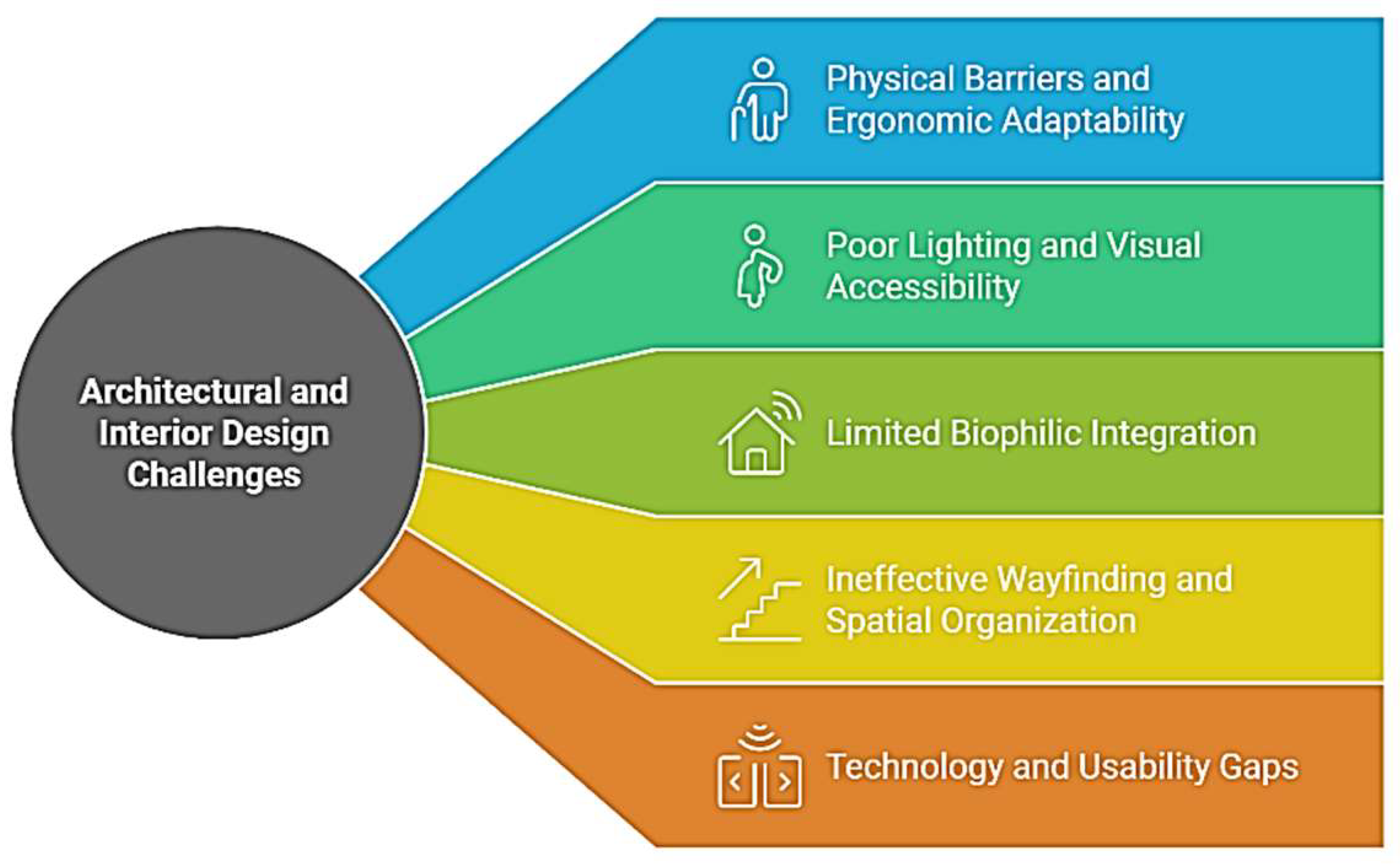

3.2. Architectural and Interior Design Challenges for Older Adults

3.3. Universal Design, Biophilia, and Technology Integration: Existing Approaches

3.4. Gaps and the Need for an Integrated Framework

4. Findings and Recommendations

4.1. Spatial Design Challenges: A Detailed Analysis

4.2. Proposed Solutions for Each Challenge

4.3. Examples and Evidence-Based Benefits

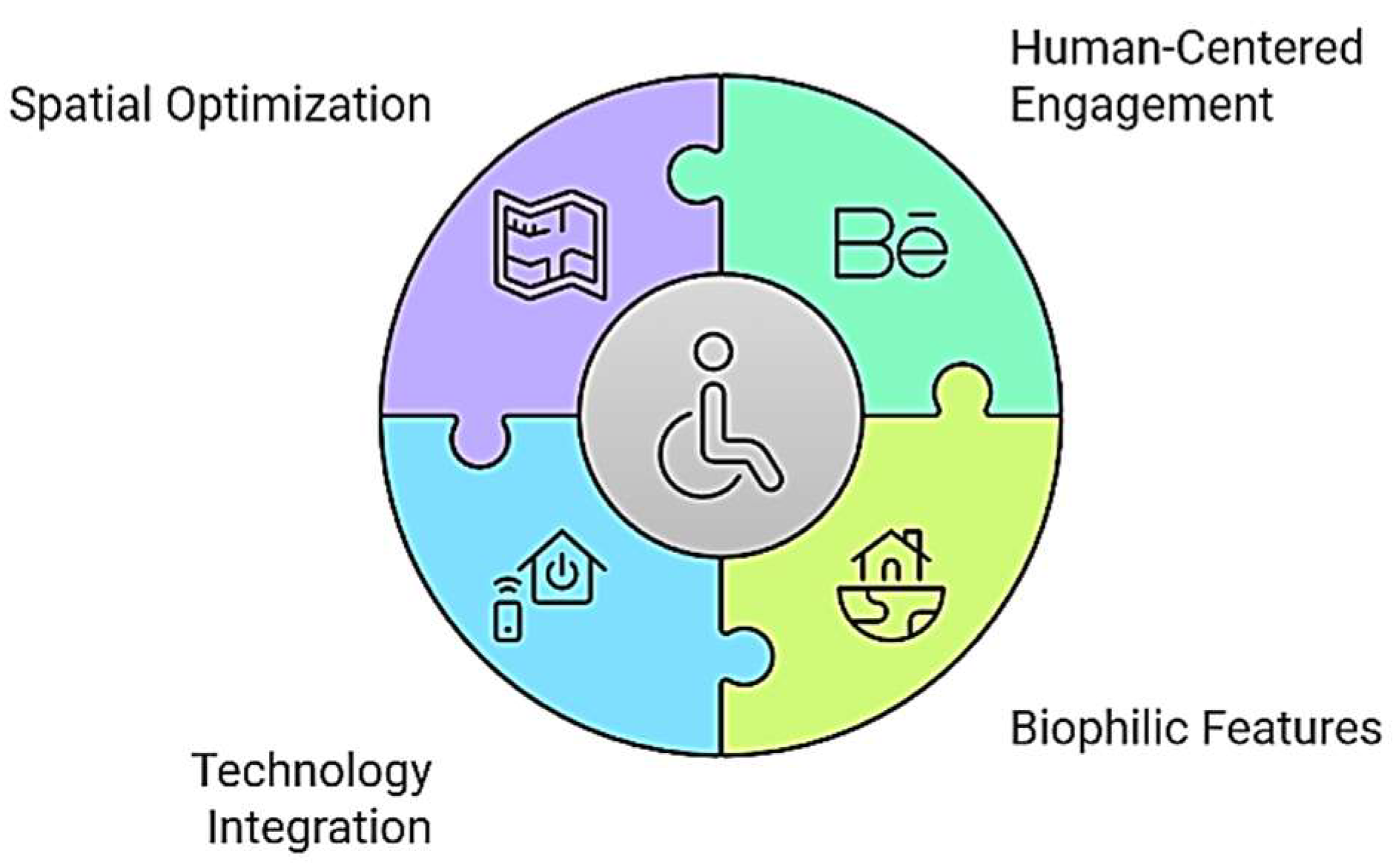

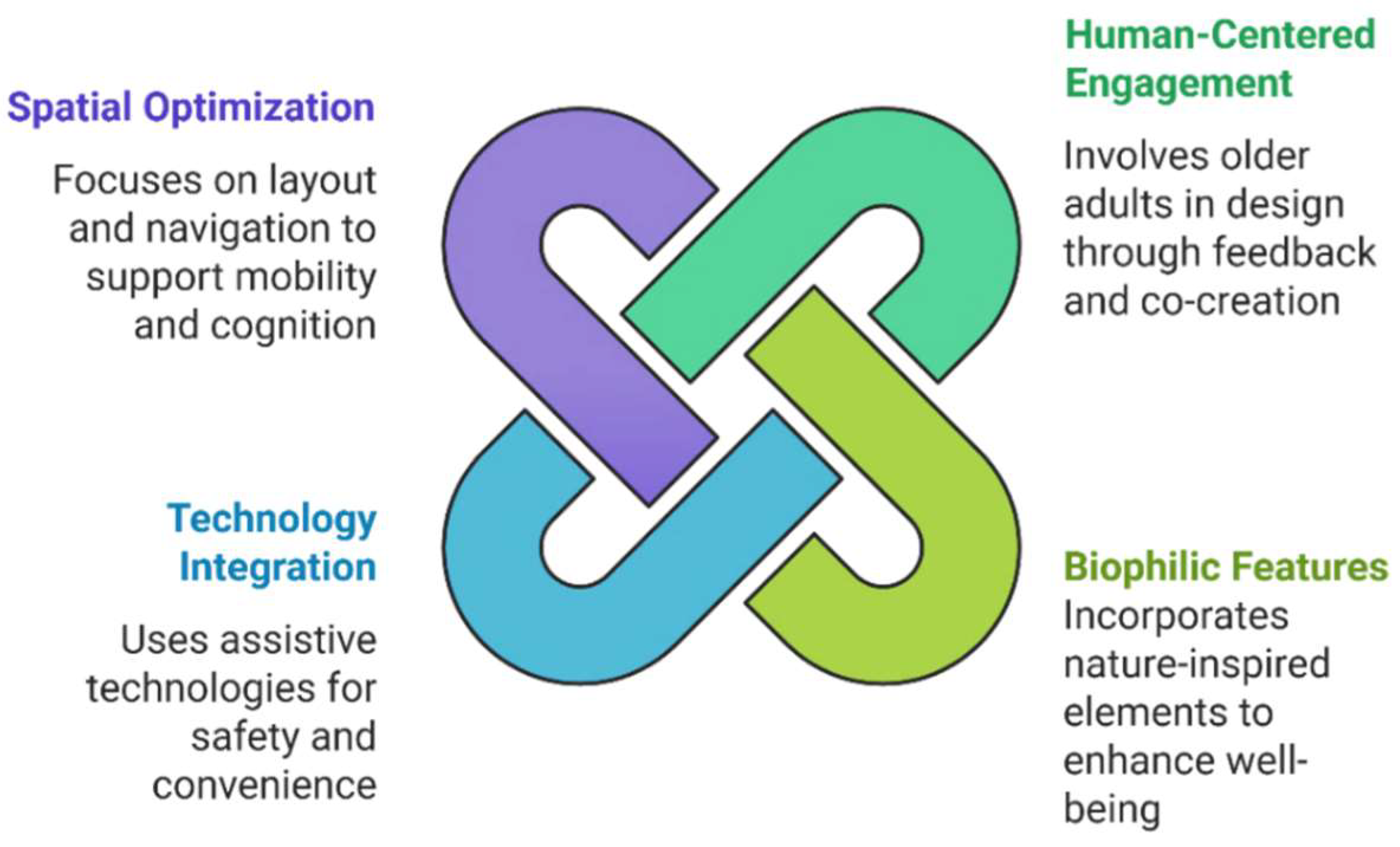

5. Conceptual Framework

5.1. Core Principles

5.2. Framework Components

5.2.1. Human-Centered Engagement

- Focus Groups and Mock-Ups: Invite older adults and caregivers to simulate daily tasks—e.g., traversing corridors, using kitchen counters, reading signage—to gather firsthand feedback on spatial adequacy (Das, Arai, & Kim, 2022; Ahmed et al., 2023a).

- Iterative Adjustments: Fine-tune hallway widths, placement of furniture, or color schemes based on user input, ensuring the space truly aligns with their physical abilities and preferences (D’haeseleer, Gielis, & Abeele, 2021).

- Varying Aesthetics: Recognize that color preferences, material choices, or privacy needs may differ by culture, thus influencing corridor brightness or bedroom layout (Demirkan & Olguntuerk, 2013; Ling, T.et al., 2023).

- Personal Artifacts: Design built-in shelves or display areas for mementos, reinforcing identity and emotional comfort (Mnea & Zairul, 2023). By systematically incorporating older adults’ perspectives, designers can create truly inclusive environments rather than merely retrofitting standard designs (Sandholdt, C. et al., 2020; Zhuan, S. 2023).

5.2.2. Biophilic and Sustainable Features

- Daylighting Strategies: Incorporate oversized windows, skylights, or light wells in living rooms and corridors, ensuring older adults can easily navigate and remain oriented to the time of day (Fox et al., 2007).

- Indoor Green Zones: Convert unused nooks into small indoor gardens or planters, offering micro-restorative spots that encourage gentle activity and reduce stress (Manca et al., 2019).

- Natural Ventilation: Cross-ventilation strategies, indoor planters, or green walls to bring in fresh air and visual stimuli (Van Hoof et al., 2019).

- Eco-Friendly Materials: Use low-VOC paints, recycled flooring, or ethically sourced timber to improve indoor air quality and reduce environmental impact (Park & Kim, 2018).

- Energy-Efficient Systems: Combine LED-based circadian lighting with sensor-driven controls, reducing energy costs and enhancing occupant well-being (Sander et al., 2015; Miller, Vine, & Amin, 2016).

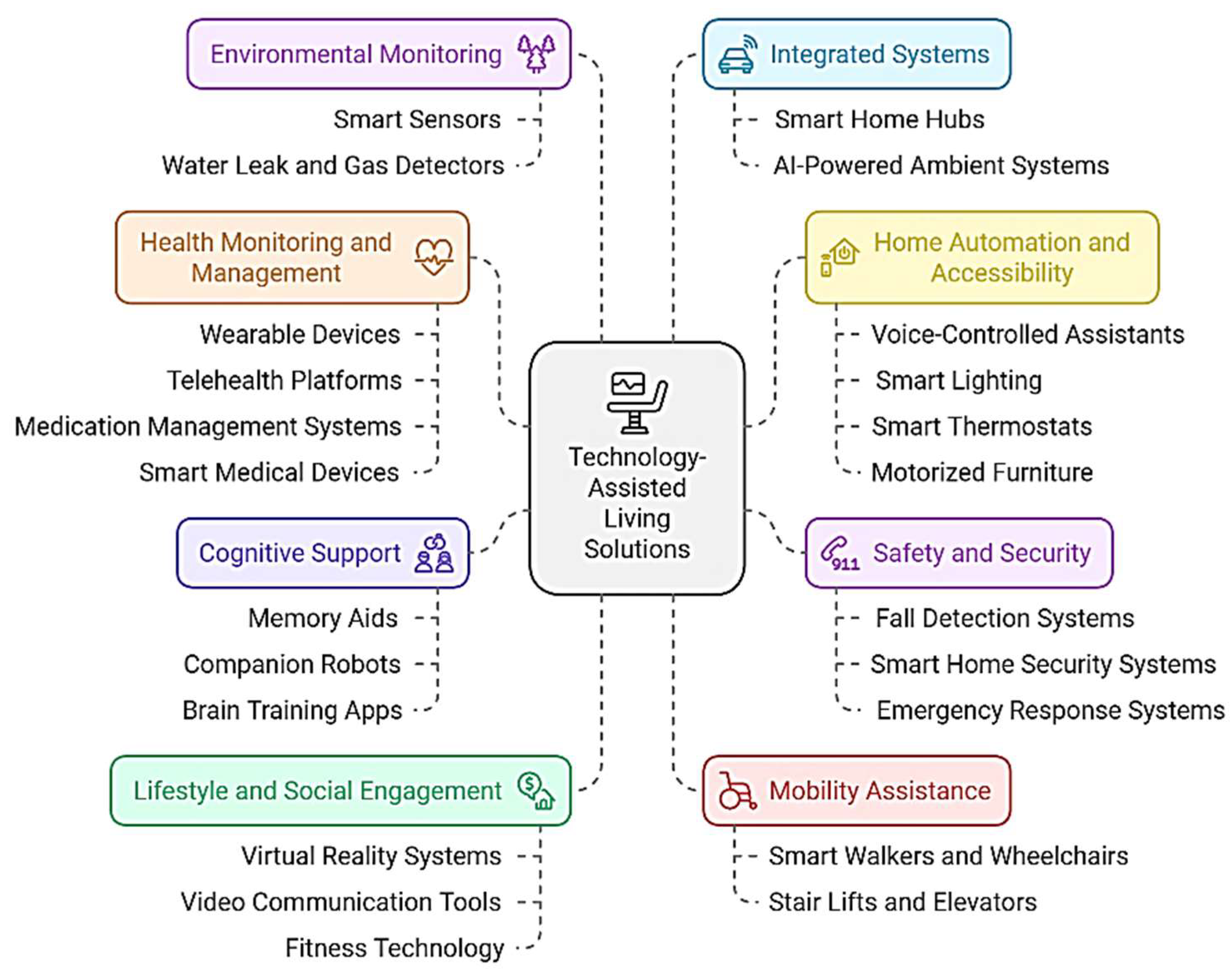

5.2.3. Technology Integration

- Non-Intrusive Sensors: Place fall-detection sensors at corridor transitions or changes in floor level (Engineer et al., 2018). Calibrate them to older adults’ traffic patterns, especially near bathrooms and bedrooms (Borelli et al., 2019).

- Smart Lighting Controls: Integrate voice-activated or motion-based triggers for corridor lights, ensuring safe and intuitive illumination (Jo, Ma, & Cha, 2021).

- Emergency Call Systems: Easily accessible panic buttons or voice-activated calls for help, especially in living rooms and kitchens (Engineer et al., 2018).

- Larger Screens and Clear Icons: Situate control panels in accessible heights at corridor intersections or near seating areas, with simple icons and large text (Shu & Liu, 2022).

- Voice-Activated Controls: For lights, heating, appliances—reducing the manual dexterity needed (Jo et al., 2021).

- Predictive Analytics: Machine learning algorithms can analyze daily routines, offering early warnings of health risks, cognitive changes, or functional decline (Shu & Liu, 2022).

- Provide clear consent options and user training to mitigate concerns about continuous monitoring (Lee, Gu, & Kwon, 2020).

- Organize onboarding sessions for older adults to learn device operations at their own pace, ensuring technology does not become an additional barrier (Peng & Maing, 2021).

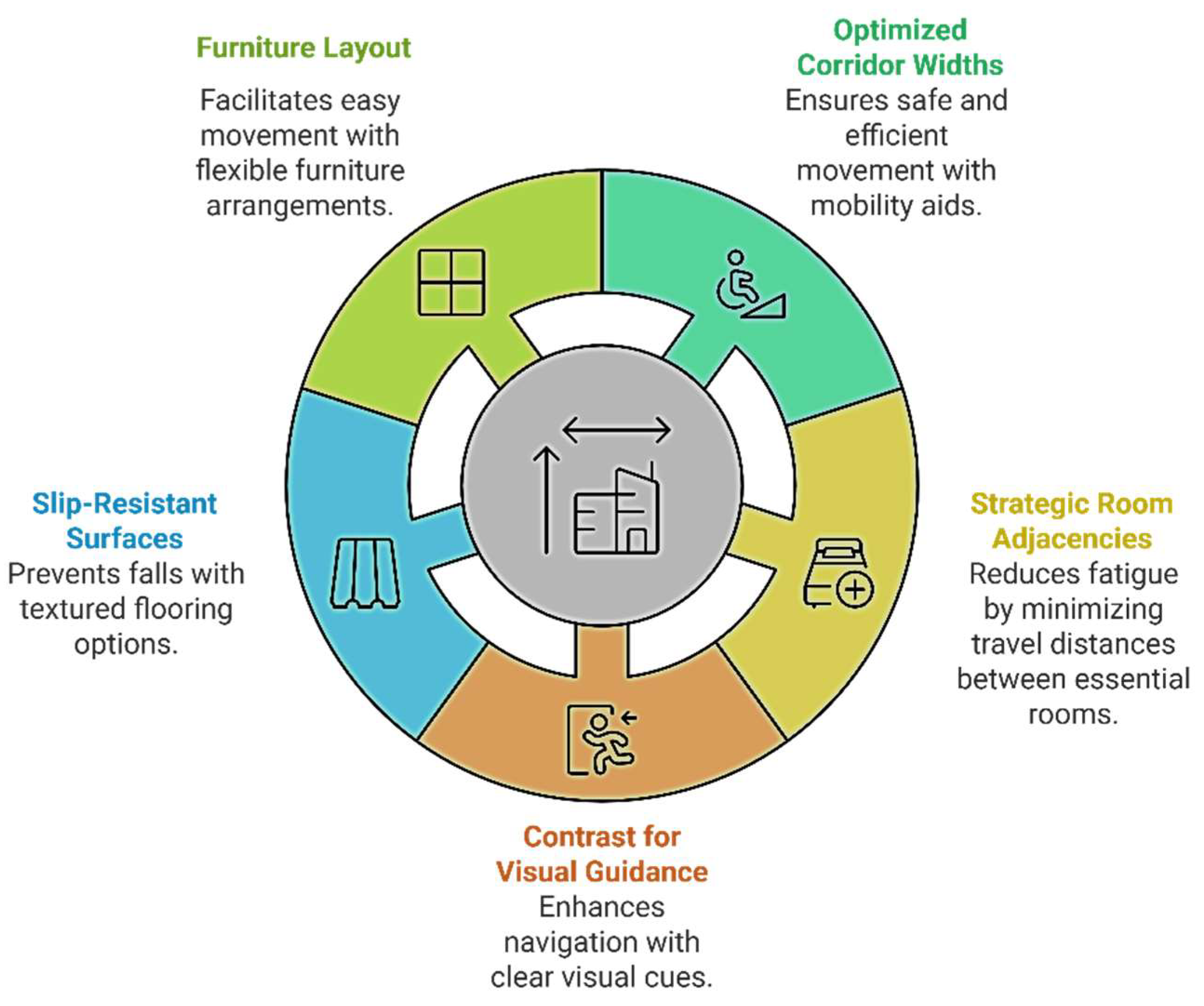

5.2.4. Spatial Factors

- Optimized Corridor Widths: Aim for hallways of at least 1.2 to 1.5 meters, minimizing collision risks with mobility aids and allowing two-way passage (Ahmed et al., 2023a; Das et al., 2022).

- Strategic Room Adjacencies: Position high-use rooms (e.g., bathrooms) near bedrooms to reduce fatigue; reduce the need for older adults to traverse long distances (Demirkan & Olguntuerk, 2013).

- Contrast for Visual Guidance: Use distinct floor–wall color contrasts or trim details that visually mark changes in level or indicate doorways (Fox et al., 2007).

- Slip-Resistant Surfaces: Select textured tiles or anti-slip coatings in kitchens, entry areas, and bathrooms to avoid falls (Romli et al., 2016; Moreland B. et al., 2020).

- Furniture Layout: Arrange seating and tables to create clear circulation routes. Favor lightweight or modular furniture for flexible reconfiguration as health needs evolve (Mnea & Zairul, 2023).

- Movable Partitions: Allow older adults to shrink or expand spaces depending on mobility or caregiving demands (Engineer et al., 2018).

- Low-Threshold Transitions: Eliminate floor-level disparities between rooms, ensuring smooth movement for walkers or wheelchairs (Lee et al., 2020).

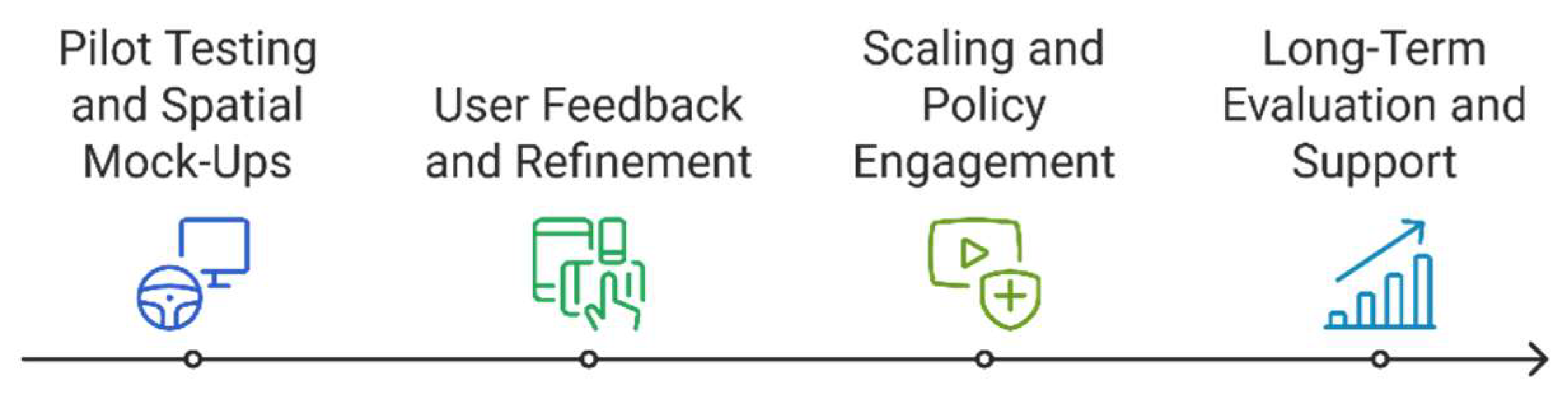

5.3. Implementation Pathway

-

Pilot Testing and Spatial Mock-Ups

- ○

- Construct full-scale prototypes of key areas (corridors, kitchens, bathrooms) for observation and co-creation with older adults and caregivers (Mnea & Zairul, 2023).

- 2.

-

User Feedback and Refinement

- ○

- Adjust corridor widths, color schemes, lighting intensity, or device positioning based on occupant preferences and safety metrics (D’haeseleer et al., 2021).

- 3.

-

Scaling and Policy Engagement

- ○

- Encourage local authorities to adopt building codes mandating universal hallway widths, step-free entries, and slip-resistant finishes (Means, 2007; Park & Kim, 2018).

- ○

- Offer grants or subsidies for homeowners and developers implementing these design changes (Miller, Vine, & Amin, 2016).

- 4.

-

Long-Term Evaluation and Support

- ○

- Conduct post-occupancy evaluations over multiple years, documenting changes in fall rates, user satisfaction, and cost-effectiveness (Shu & Liu, 2022).

- ○

- Provide maintenance plans, technology updates, and ongoing user training to keep solutions aligned with evolving abilities (Peng & Maing, 2021).

6. Discussion

6.1. Implications for Policy and Practice

6.2. Theoretical and Practical Contributions

6.3. Barriers and Limitations

6.4. Future Research Directions

7. Conclusions

References

- Ahmed, M. N., M Hassan, N., & Morghany, E. (2023a). A Conceptional Framework for Integration of Architecture and Gerontology to Create Elderly-Friendly Home Environments in Egypt. JES. Journal of Engineering Sciences, 51(6), 468-500. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, M. N., M Hassan, N., & Morghany, E. (2023b). Exploring elderly challenges, needs, and adaptive strategies to promote aging in place. JES. Journal of Engineering Sciences, 51(4), 260-286. [CrossRef]

- Akl, A., Snoek, J., & Mihailidis, A. (2017). Unobtrusive Detection of Mild Cognitive Impairment in Older Adults Through Home Monitoring. IEEE Journal of Biomedical and Health Informatics, 21, 339-348. [CrossRef]

- Akl, A., Chikhaoui, B., Mattek, N., Kaye, J., Austin, D., & Mihailidis, A. (2016). Clustering home activity distributions for automatic detection of mild cognitive impairment in older adults. Journal of ambient intelligence and smart environments, 8 4, 437-451 . [CrossRef]

- Bennetts, H., Arakawa Martins, L., van Hoof, J., & Soebarto, V. (2020). Thermal Personalities of Older People in South Australia: A Personas-Based Approach to Develop Thermal Comfort Guidelines. International journal of environmental research and public health, 17(22), 8402. [CrossRef]

- Binette Joanne. (2021). Home and Community Preferences Survey. AARP Research. [CrossRef]

- Borelli, E., Paolini, G., Antoniazzi, F., Barbiroli, M., Benassi, F., Chesani, F., Chiari, L., Fantini, M., Fuschini, F., Galassi, A., Giacobone, G. A., Imbesi, S., Licciardello, M., Loreti, D., Marchi, M., Masotti, D., Mello, P., Mellone, S., Mincolelli, G., ... Costanzo, A. (2019). HABITAT: An IoT Solution for Independent Elderly. Sensors, 19(5), 1258. [CrossRef]

- Castilla, D., Suso-Ribera, C., Zaragoza, I., Garcia-Palacios, A., & Botella, C. (2020). Designing ICTs for Users with Mild Cognitive Impairment: A Usability Study. International journal of environmental research and public health, 17(14), 5153. [CrossRef]

- Chen, L., & Liu, Y. (2022). Interface Design for Products for Users with Advanced Age and Cognitive Impairment. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19. [CrossRef]

- Chen, L., & Liu, Y. (2017). Affordance and Intuitive Interface Design for Elder Users with Dementia. Procedia CIRP, 60, 470-475. [CrossRef]

- Connell, B. R., Jones, M., Mace, R., Mueller, J., Mullick, A., Ostroff, E., Sanford, J., Steinfeld, E., Story, M., & Vanderheiden, G. (1997). The principles of universal design (Version 2.0). The Center for Universal Design, N.C. State University.

- Das, Maitreyi Bordia; Arai, Yuko; Chapman, Terri B.; Jain, Vibhu. (2022). Silver Hues: Building Age-Ready Cities. © World Bank, Washington, DC. http://hdl.handle.net/10986/37259 License: CC BY 3.0 IGO.”.

- Demirkan, H., & Olguntürk, N. (2013). A priority-based ‘design for all’ approach to guide home designers for independent living. Architectural Science Review, 57(2), 90–104. [CrossRef]

- D'haeseleer, I., Gielis, K., & Abeele, V. (2021). Human-centred design of self-management health systems with and for older adults: Challenges and practical guidelines, 90-102. [CrossRef]

- Engineer, A., Sternberg, E. M., & Najafi, B. (2018). Designing Interiors to Mitigate Physical and Cognitive Deficits Related to Aging and to Promote Longevity in Older Adults: A Review. Gerontology, 64(6), 612–622. [CrossRef]

- Forsyth, A., & Molinsky, J. (2023). Climate Change, Aging, and Well-being: How Residential Setting Matters. Housing Policy Debate, 33(5), 1029–1054. [CrossRef]

- Fournier, H., Kondratova, I., & Katsuragawa, K. (2021). Smart technologies and the Internet of Things designed for aging in place. In Moallem, A. (Ed.), HCI for Cybersecurity, Privacy and Trust. HCII 2021. Lecture Notes in Computer Science, vol 12788. Springer, Cham. [CrossRef]

- Fox, K., Stathi, A., McKenna, J., & Davis, M. G. (2007). Physical activity and mental well-being in older people participating in the Better Ageing Project. European Journal of Applied Physiology, 100(6), 591-602. [CrossRef]

- Granbom, M., Slaug, B., Löfqvist, C., Oswald, F., & Iwarsson, S. (2016). Community Relocation in Very Old Age: Changes in Housing Accessibility. The American journal of occupational therapy : Official publication of the American Occupational Therapy Association, 70(2), 7002270020p1–7002270020p9. [CrossRef]

- Jo, T. H., Ma, J. H., & Cha, S. H. (2021). Elderly Perception on the Internet of Things-Based Integrated Smart-Home System. Sensors, 21(4), 1284. [CrossRef]

- Kahana, E. (1982). A congruence model of person-environment interaction. Aging and the environment: Theoretical approaches, 97-121.

- Lawton, M. P., & Nahemow, L. (1973). Ecology and the aging process. In C. Eisdorfer & M. P. Lawton (Eds.), The psychology of adult development and aging (pp. 619–674). American Psychological Association. [CrossRef]

- Lee LN and Kim MJ (2020) A Critical Review of Smart Residential Environments for Older Adults With a Focus on Pleasurable Experience. Front. Psychol. [CrossRef]

- Ling, T.-Y., Lu, H.-T., Kao, Y.-P., Chien, S.-C., Chen, H.-C., & Lin, L.-F. (2023). Understanding the meaningful places for aging-in-place: A human-centric approach toward inter-domain design criteria consideration in Taiwan. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(2), 1373. [CrossRef]

- Manca, S., Cerina, V., & Fornara, F. (2019). Residential satisfaction, psychological well-being and perceived environmental qualities in high- vs. low-humanized residential facilities for the elderly. Social Psychological Bulletin, 14(2), 1–19. [CrossRef]

- Mayo, C., Kenny, R., Scarapicchia, V., Ohlhauser, L., Syme, R., & Gawryluk, J. (2021). Aging in Place: Challenges of Older Adults with Self-Reported Cognitive Decline. Canadian Geriatrics Journal, 24, 138 - 143. [CrossRef]

- Means, R. (2007). Safe as houses? Ageing in place and vulnerable older people in the UK. Social Policy & Administration, 41(1), 65–85. [CrossRef]

- Miller, W., Vine, D., & Amin, Z.M. (2017). Energy efficiency of housing for older citizens: Does it matter? Energy Policy, 101, 216-224. [CrossRef]

- Mnea, A., & Zairul, M. (2023). Evaluating the Impact of Housing Interior Design on Elderly Independence and Activity: A Thematic Review. Buildings, 13(4), 1099. [CrossRef]

- Moreland B, Kakara R, Henry A. (2020). Trends in Nonfatal Falls and Fall-Related Injuries Among Adults Aged ≥65 Years — United States, 2012–2018. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR) Rep 2020;69:875–881 . [CrossRef]

- Park, S. J., & Kim, M. J. (2018). A Framework for Green Remodeling Enabling Energy Efficiency and Healthy Living for the Elderly. Energies, 11(8), 2031. [CrossRef]

- Peng, S., & Maing, M. (2021). Influential factors of age-friendly neighborhood open space under high-density high-rise housing context in hot weather: A case study of public housing in Hong Kong. Cities, 115, 103231. [CrossRef]

- Piau, A., Wild, K., Mattek, N., & Kaye, J. (2019). Current State of Digital Biomarker Technologies for Real-Life, Home-Based Monitoring of Cognitive Function for Mild Cognitive Impairment to Mild Alzheimer Disease and Implications for Clinical Care: Systematic Review. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 21. [CrossRef]

- Ramsamy-Iranah, S., Rosunee, S., Kistamah, N. (2016). Introducing Assistive Tactile Colour Symbols for Children with Visual Impairment: A Preliminary Research. In: Langdon, P., Lazar, J., Heylighen, A., Dong, H. (eds) Designing Around People. Springer, Cham. [CrossRef]

- Ratnayake, M., Lukas, S., Brathwaite, S., Neave, J., & Henry, H. (2022). Aging in Place. Delaware Journal of Public Health, 8, 28–31. [CrossRef]

- Romli, M. H., Mackenzie, L., Lovarini, M., & Tan, M. P. (2016). Pilot study to investigate the feasibility of the Home Falls and Accidents Screening Tool (HOME FAST) to identify older Malaysian people at risk of falls. BMJ open, 6(8), e012048. [CrossRef]

- Sander, B., Markvart, J., Kessel, L., Argyraki, A., & Johnsen, K. (2015). Can sleep quality and wellbeing be improved by changing the indoor lighting in the homes of healthy, elderly citizens?. Chronobiology international, 32(8), 1049–1060. [CrossRef]

- Sandholdt, C., Cunningham, J., Westendorp, R., & Kristiansen, M. (2020). Towards inclusive healthcare delivery: Potentials and challenges of human-centred design in health innovation processes to increase healthy aging. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17. [CrossRef]

- Shu, Q., & Liu, H. (2022). Application of Artificial Intelligence Computing in the Universal Design of Aging and Healthy Housing. Computational intelligence and neuroscience, 2022, 4576397. [CrossRef]

- Sokullu, R., Akkaş, M., & Demir, E. (2020). IoT supported smart home for the elderly. Internet Things. [CrossRef]

- Stavrotheodoros, S., Kaklanis, N., Votis, K., Tzovaras, D. (2018). A Smart-Home IoT Infrastructure for the Support of Independent Living of Older Adults. In: Iliadis, L., Maglogiannis, I., Plagianakos, V. (eds) Artificial Intelligence Applications and Innovations. AIAI 2018. IFIP Advances in Information and Communication Technology, vol 520. Springer, Cham. [CrossRef]

- Tsuchiya-Ito, R., Iwarsson, S., & Slaug, B. (2019). Environmental Challenges in the Home for Ageing Societies: A Comparison of Sweden and Japan. Journal of cross-cultural gerontology, 34(3), 265–289. [CrossRef]

- van Hoof, J., Bennetts, H., Hansen, A., Kazak, J. K., & Soebarto, V. (2019). The Living Environment and Thermal Behaviours of Older South Australians: A Multi-Focus Group Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(6), 935. [CrossRef]

- Vitiello, G., & Sebillo, M. (2018). The importance of empowerment goals in elderly-centered interaction design. Proceedings of the 2018 International Conference on Advanced Visual Interfaces. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y., Lin, D., & Huang, Z. (2022). Research on the Aging-Friendly Kitchen Based on Space Syntax Theory. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(9), 5393. [CrossRef]

- WHO (World Health Organization). (2015). World report on ageing and health. World Health Organization. https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/186463.

- Zhuan, S. (2023). Research on Aging-friendly Home Space Design Based on Humanization. Academic Journal of Architecture and Geotechnical Engineering. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).