Submitted:

06 January 2025

Posted:

07 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Simulation Model and Method

2.1. Atomistic Model Preparation

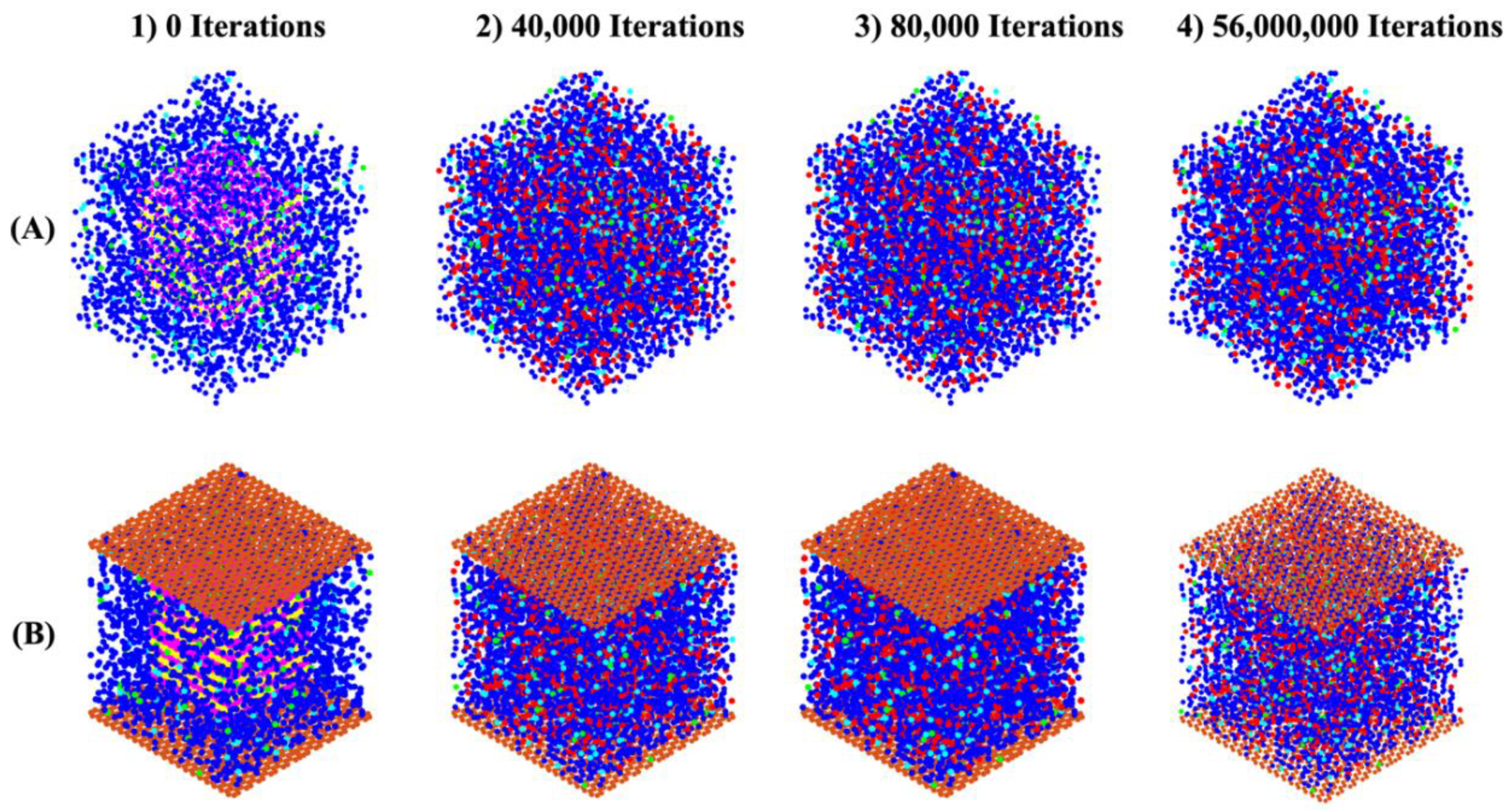

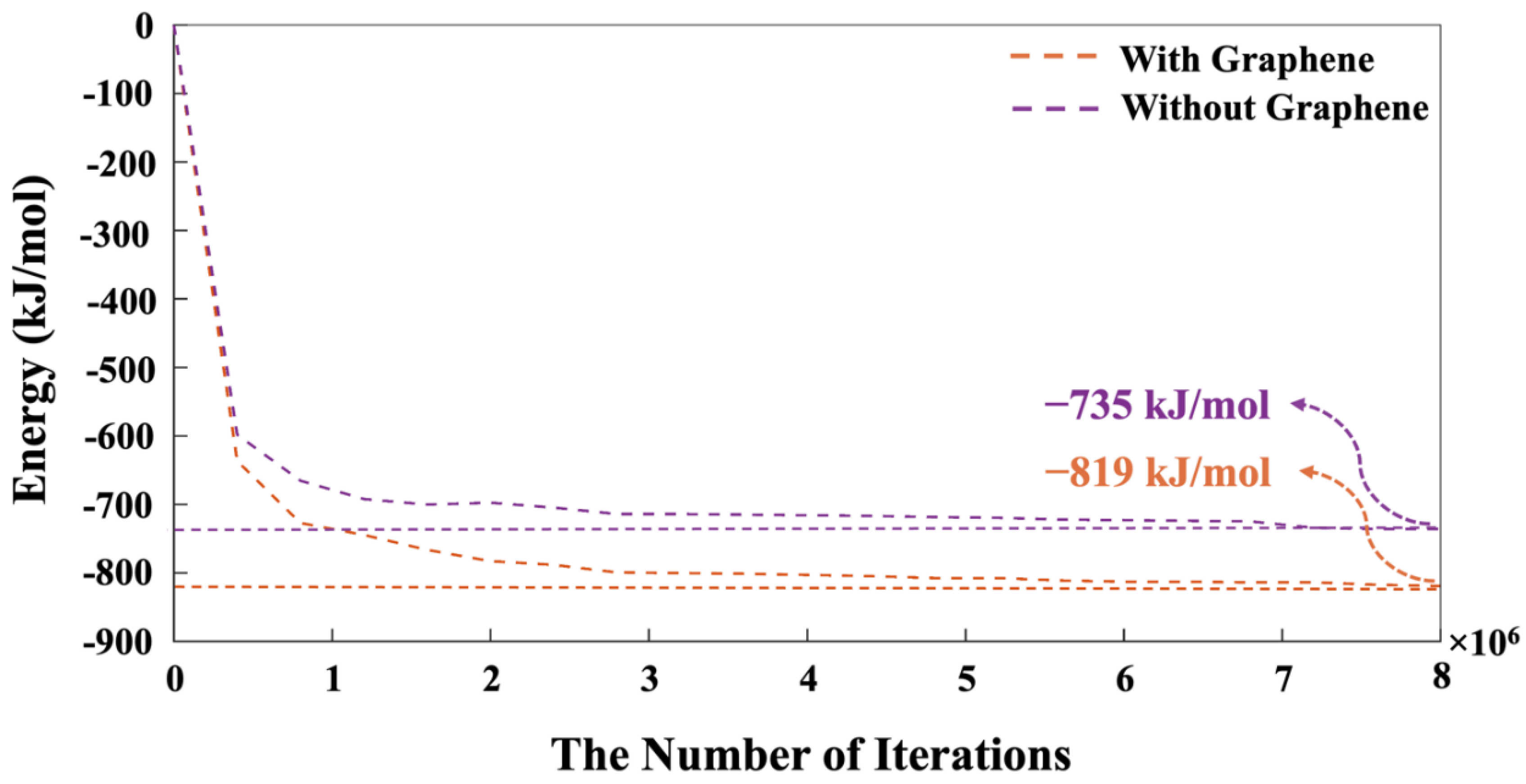

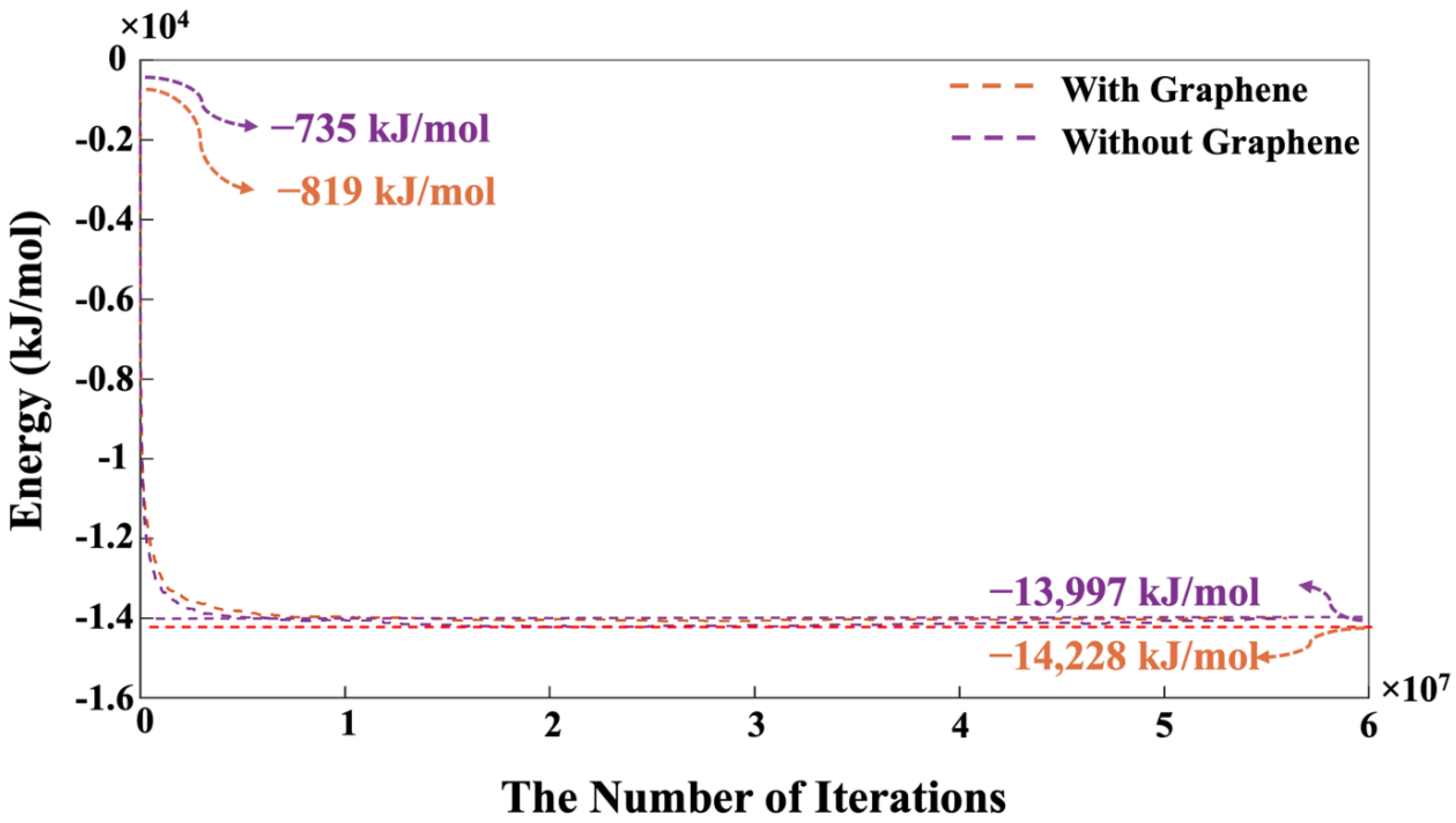

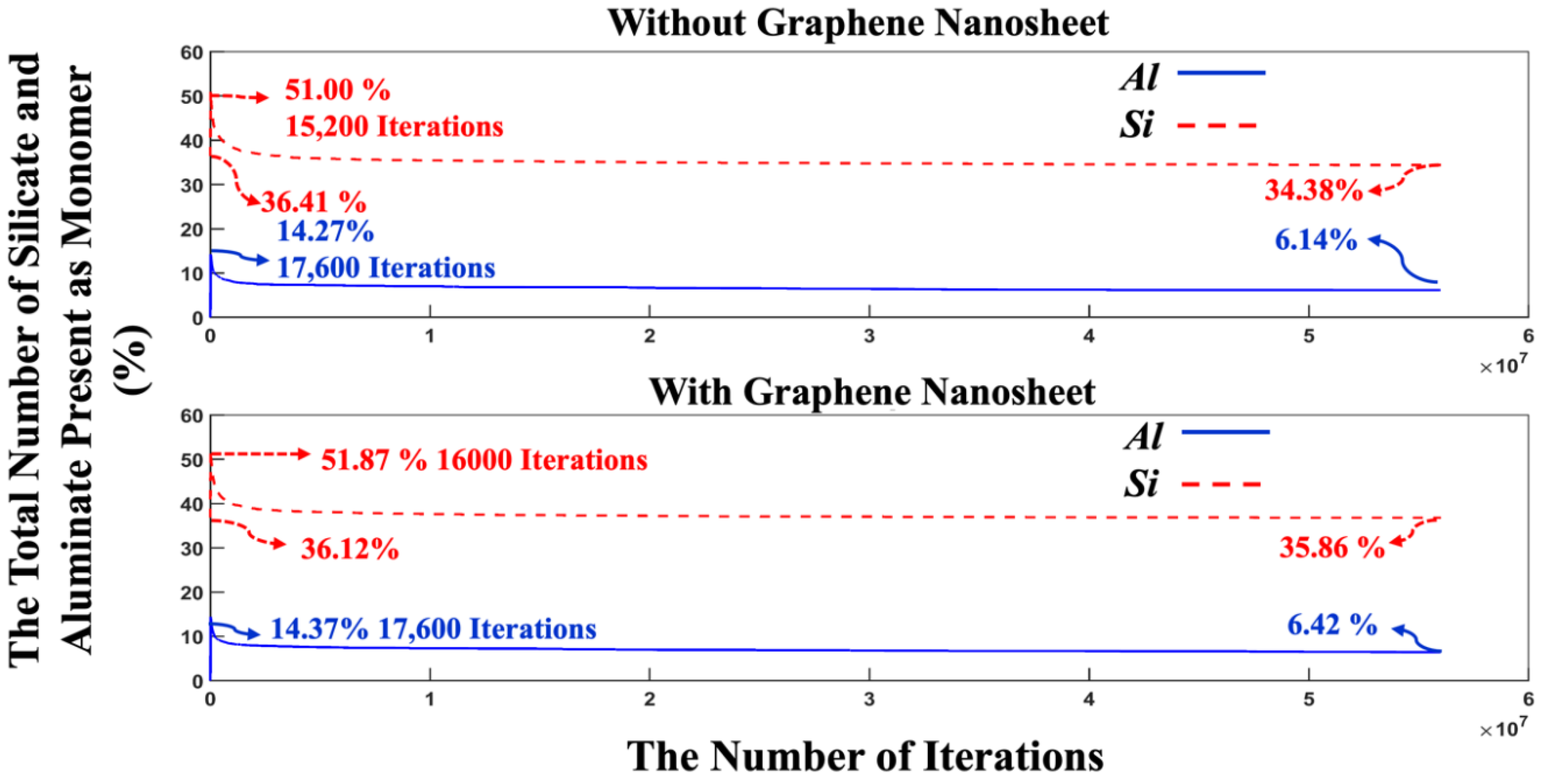

2.2. Monte Carlo Approach: Implementation in MATLAB Code

2.3. Octree Cells Approach: MATLAB Program Development

2.4. Density Functional Theory (DFT) Computational Modeling Method

3. Results and Discussions

4. Conclusions

Acknowledgements

Declaration of Competing Interest

References

- J. Davidovits, “Geopolymers: Inorganic polymeric new materials,” Journal of Thermal Analysis, vol. 37, no. 8, pp. 1633–1656, Aug. 1991. [CrossRef]

- S. Chitsaz and A. Tarighat, “Molecular dynamics simulation of N-A-S-H geopolymer macro molecule model for prediction of its modulus of elasticity,” Construction and Building Materials, vol. 243, p. 118176, May 2020. [CrossRef]

- P. Duxson, A. Fernández-Jiménez, J. L. Provis, G. C. Lukey, A. Palomo, and J. S. J. van Deventer, “Geopolymer technology: the current state of the art,” J Mater Sci, vol. 42, no. 9, pp. 2917–2933, May 2007. [CrossRef]

- M. Izadifar, N. Ukrainczyk, and E. Koenders, “Silicate Dissolution Mechanism from Metakaolinite Using Density Functional Theory,” Nanomaterials, vol. 13, no. 7, Art. no. 7, Mar. 2023. [CrossRef]

- M. Izadifar, N. Ukrainczyk, and E. Koenders, “Atomistic Insights into Silicate Dissolution of Metakaolinite under Alkaline Conditions: Ab Initio Quantum Mechanical Investigation,” Langmuir, vol. 40, no. 37, pp. 19332–19342, Sep. 2024. [CrossRef]

- A. Buchwald, H.-D. Zellmann, and Ch. Kaps, “Condensation of aluminosilicate gels—model system for geopolymer binders,” Journal of Non-Crystalline Solids, vol. 357, no. 5, pp. 1376–1382, Mar. 2011. [CrossRef]

- C. E. White, J. L. Provis, T. Proffen, and J. S. J. van Deventer, “Molecular mechanisms responsible for the structural changes occurring during geopolymerization: Multiscale simulation,” AIChE J., vol. 58, no. 7, pp. 2241–2253, Jul. 2012. [CrossRef]

- M. Izadifar et al., “COMPREHENSIVE EXAMINATION OF DEHYDROXYLATION OF KAOLINITE, DISORDERED KAOLINITE, AND DICKITE: EXPERIMENTAL STUDIES AND DENSITY FUNCTIONAL THEORY,” Clays and Clay Minerals, vol. 68, no. 4, pp. 319–333, 2020. [CrossRef]

- T. Bakharev, “Resistance of geopolymer materials to acid attack,” Cement and Concrete Research, vol. 35, no. 4, pp. 658–670, Apr. 2005. [CrossRef]

- N. Ukrainczyk, M. Muthu, O. Vogt, and E. Koenders, “Geopolymer, Calcium Aluminate, and Portland Cement-Based Mortars: Comparing Degradation Using Acetic Acid,” Materials, vol. 12, no. 19, p. 3115, Sep. 2019. [CrossRef]

- A. Koenig, A. Herrmann, S. Overmann, and F. Dehn, “Resistance of alkali-activated binders to organic acid attack: Assessment of evaluation criteria and damage mechanisms,” Construction and Building Materials, vol. 151, pp. 405–413, Oct. 2017. [CrossRef]

- M. Amran, S.-S. Huang, S. Debbarma, and R. S. M. Rashid, “Fire resistance of geopolymer concrete: A critical review,” Construction and Building Materials, vol. 324, p. 126722, Mar. 2022. [CrossRef]

- M. R. Sadat, K. Muralidharan, G. N. Frantziskonis, and L. Zhang, “From atomic-scale to mesoscale: A characterization of geopolymer composites using molecular dynamics and peridynamics simulations,” Computational Materials Science, vol. 186, p. 110038, Jan. 2021. [CrossRef]

- J. Henon, F. Pennec, A. Alzina, J. Absi, D. S. Smith, and S. Rossignol, “Analytical and numerical identification of the skeleton thermal conductivity of a geopolymer foam using a multi-scale analysis,” Computational Materials Science, vol. 82, pp. 264–273, Feb. 2014. [CrossRef]

- F. Lolli, H. Manzano, J. L. Provis, M. C. Bignozzi, and E. Masoero, “Atomistic Simulations of Geopolymer Models: The Impact of Disorder on Structure and Mechanics,” ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces, vol. 10, no. 26, pp. 22809–22820, Jul. 2018. [CrossRef]

- M. Izadifar, N. C. Valencia, P. Xiao, N. Ukrainczyk, and E. Koenders, “3D Off-Lattice Coarse-Grained Monte Carlo Simulations for Nucleation of Alkaline Aluminosilicate Gels,” Materials, vol. 16, no. 5, Art. no. 5, Feb. 2023. [CrossRef]

- C. E. White, J. L. Provis, G. J. Kearley, D. P. Riley, and J. S. J. Van Deventer, “Density functional modelling of silicate and aluminosilicate dimerisation solution chemistry,” Dalton Trans., vol. 40, no. 6, Art. no. 6, 2011. [CrossRef]

- N. C. Valencia, M. Izadifar, N. Ukrainczyk, and E. Koenders, “Coarse-Grained Monte Carlo Simulations with Octree Cells for Geopolymer Nucleation at Different pH Values,” Materials, vol. 17, no. 1, p. 95, Dec. 2023. [CrossRef]

- L. Prasittisopin and I. Sereewatthanawut, “Effects of seeding nucleation agent on geopolymerization process of fly-ash geopolymer,” Front. Struct. Civ. Eng., vol. 12, no. 1, pp. 16–25, Mar. 2018. [CrossRef]

- K. Yang and C. E. White, “Modeling the Formation of Alkali Aluminosilicate Gels at the Mesoscale Using Coarse-Grained Monte Carlo,” Langmuir, vol. 32, no. 44, pp. 11580–11590, Nov. 2016. [CrossRef]

- M. Izadifar, J. S. Dolado, P. Thissen, N. Ukrainczyk, E. Koenders, and A. Ayuela, “Theoretical Elastic Constants of Tobermorite Enhanced with Reduced Graphene Oxide through Hydroxyl vs Epoxy Functionalization: A First-Principles Study,” J. Phys. Chem. C, vol. 127, no. 36, pp. 18117–18126, Sep. 2023. [CrossRef]

- C. E. White, J. L. Provis, T. Proffen, and J. S. J. van Deventer, “Quantitative Mechanistic Modeling of Silica Solubility and Precipitation during the Initial Period of Zeolite Synthesis,” J. Phys. Chem. C, vol. 115, no. 20, pp. 9879–9888, May 2011. [CrossRef]

- K. S. Novoselov et al., “Electric Field Effect in Atomically Thin Carbon Films,” Science, vol. 306, no. 5696, pp. 666–669, 2004. [CrossRef]

- A. A. Balandin et al., “Superior Thermal Conductivity of Single-Layer Graphene,” Nano Letters, vol. 8, no. 3, pp. 902–907, Mar. 2008. [CrossRef]

- B. Mortazavi, “Ultra high stiffness and thermal conductivity of graphene like C3N,” Carbon, vol. 118, pp. 25–34, 2017. [CrossRef]

- B. Mortazavi, M. Pötschke, and G. Cuniberti, “Multiscale modeling of thermal conductivity of polycrystalline graphene sheets,” Nanoscale, vol. 6, no. 6, pp. 3344–3352, 2014. [CrossRef]

- B. Mortazavi and S. Ahzi, “Thermal conductivity and tensile response of defective graphene: A molecular dynamics study,” Carbon, vol. 63, pp. 460–470, Nov. 2013. [CrossRef]

- C. Lee, X. Wei, J. W. Kysar, and J. Hone, “Measurement of the Elastic Properties and Intrinsic Strength of Monolayer Graphene,” Science, vol. 321, no. 5887, pp. 385–388, 2008. [CrossRef]

- B. Mortazavi and G. Cuniberti, “Atomistic modeling of mechanical properties of polycrystalline graphene,” Nanotechnology, vol. 25, no. 21, p. 215704, May 2014. [CrossRef]

- M. Izadifar et al., “Fracture toughness of various percentage of doping of boron atoms on the mechanical properties of polycrystalline graphene: A molecular dynamics study,” Physica E: Low-dimensional Systems and Nanostructures, vol. 114, p. 113614, 2019. [CrossRef]

- M. Izadifar, R. Abadi, A. N. Jam, and T. Rabczuk, “Investigation into the effect of doping of boron and nitrogen atoms in the mechanical properties of single-layer polycrystalline graphene,” Computational Materials Science, vol. 138, pp. 435–447, 2017. [CrossRef]

- J. R. Williams, L. DiCarlo, and C. M. Marcus, “Quantum Hall Effect in a Gate-Controlled p-n Junction of Graphene,” Science, vol. 317, no. 5838, pp. 638–641, 2007. [CrossRef]

- R. S. Krishna, J. Mishra, B. Nanda, S. K. Patro, A. Adetayo, and T. S. Qureshi, “The role of graphene and its derivatives in modifying different phases of geopolymer composites: A review,” Construction and Building Materials, vol. 306, p. 124774, Nov. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Y. J. Zhang, P. Y. He, M. Y. Yang, and L. Kang, “A new graphene bottom ash geopolymeric composite for photocatalytic H 2 production and degradation of dyeing wastewater,” International Journal of Hydrogen Energy, vol. 42, no. 32, pp. 20589–20598, Aug. 2017. [CrossRef]

- J. Zhong, G.-X. Zhou, P.-G. He, Z.-H. Yang, and D.-C. Jia, “3D printing strong and conductive geo-polymer nanocomposite structures modified by graphene oxide,” Carbon, vol. 117, pp. 421–426, 2017. [CrossRef]

- M. Izadifar, W. Sekkal, L. Dubyey, N. Ukrainczyk, A. Zaoui, and E. Koenders, “Theoretical Studies of Adsorption Reactions of Aluminosilicate Aqueous Species on Graphene-Based Nanomaterials: Implications for Geopolymer Binders,” ACS Appl. Nano Mater., p. acsanm.3c02438, Sep. 2023. [CrossRef]

- J. Šefčík and A. V. McCormick, “Thermochemistry of aqueous silicate solution precursors to ceramics,” AIChE J., vol. 43, no. S11, pp. 2773–2784, 1997. [CrossRef]

- M. Izadifar, N. Ukrainczyk, K. M. Salah Uddin, B. Middendorf, and E. Koenders, “Dissolution of β-C2S Cement Clinker: Part 2 Atomistic Kinetic Monte Carlo (KMC) Upscaling Approach,” Materials, vol. 15, no. 19, p. 6716, Sep. 2022. [CrossRef]

- M. Izadifar, N. Ukrainczyk, K. Salah Uddin, B. Middendorf, and E. Koenders, “Dissolution of Portlandite in Pure Water: Part 2 Atomistic Kinetic Monte Carlo (KMC) Approach,” Materials, vol. 15, no. 4, p. 1442, Feb. 2022. [CrossRef]

- M. Jorge, S. M. Auerbach, and P. A. Monson, “Modeling Spontaneous Formation of Precursor Nanoparticles in Clear-Solution Zeolite Synthesis,” J. Am. Chem. Soc., vol. 127, no. 41, Art. no. 41, Oct. 2005. [CrossRef]

- W. Kohn and L. J. Sham, “Self-Consistent Equations Including Exchange and Correlation Effects,” Phys. Rev., vol. 140, no. 4A, p. A1133—-A1138, Nov. 1965. [CrossRef]

- G. Kresse and J. Hafner, “Ab initio molecular dynamics for liquid metals,” Phys. Rev. B, vol. 47, no. 1, pp. 558–561, Jan. 1993. [CrossRef]

- G. Kresse and J. Furthmüller, “Efficiency of ab-initio total energy calculations for metals and semiconductors using a plane-wave basis set,” Computational Materials Science, vol. 6, no. 1, pp. 15–50, 1996. [CrossRef]

- G. Kresse and J. Furthmüller, “Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set,” Phys. Rev. B, vol. 54, no. 16, pp. 11169–11186, Oct. 1996. [CrossRef]

- J. Hafner, “Ab-initio simulations of materials using VASP: Density-functional theory and beyond,” J Comput Chem, vol. 29, no. 13, pp. 2044–2078, Oct. 2008. [CrossRef]

- G. Sun, J. Kürti, P. Rajczy, M. Kertesz, J. Hafner, and G. Kresse, “Performance of the Vienna ab initio simulation package (VASP) in chemical applications,” Journal of Molecular Structure: THEOCHEM, vol. 624, no. 1–3, pp. 37–45, Apr. 2003. [CrossRef]

- G. Kresse and D. Joubert, “From ultrasoft pseudopotentials to the projector augmented-wave method,” Phys. Rev. B, vol. 59, no. 3, pp. 1758–1775, Jan. 1999. [CrossRef]

- J. P. Perdew, K. Burke, and M. Ernzerhof, “Generalized Gradient Approximation Made Simple,” Phys. Rev. Lett., vol. 77, no. 18, pp. 3865–3868, Oct. 1996. [CrossRef]

- H. J. Monkhorst and J. D. Pack, “Special points for Brillouin-zone integrations,” Phys. Rev. B, vol. 13, no. 12, pp. 5188–5192, Jun. 1976. [CrossRef]

- K. Momma and F. Izumi, “ıt VESTA: a three-dimensional visualization system for electronic and structural analysis,” Journal of Applied Crystallography, vol. 41, no. 3, pp. 653–658, Jun. 2008. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).