1. Introduction

The widespread use of fertilizers and pesticides in agriculture, particularly herbicides, poses a significant threat to water quality. Herbicides are the most extensively employed class of pesticides and are recognized as persistent organic pollutants due to their low biodegradability. During their biotic and abiotic transformations in soil, herbicides form complex metabolites that can infiltrate groundwater at relatively high concentrations, raising concerns about potential human health risks [

1,

2]. Consequently, the global scientific community has intensified its focus on developing effective treatment methods for herbicide-contaminated wastewater.

Over the past two decades, the worldwide consumption of herbicides has escalated, compounding worries about their environmental fate and slow decomposition rates [

3]. Advanced oxidation processes (AOPs) have gained traction as a promising solution for degrading commercial herbicides. For example, the tandem process of sonolysis and photocatalysis (sonophotocatalysis), which employs an ultrasound source of 20 kHz combined with UV light, has shown notable efficacy in degrading herbicides such as alazine and gesaprim [

4,

5]. These approaches have achieved nearly complete mineralization of active compounds when ultrasound is used alongside a TiO₂ catalyst, highlighting the potential of sonophotocatalysis in mitigating herbicide pollution.

Despite these promising results, the sonophotocatalytic degradation of commercial herbicides remains complex, influenced by factors such as radiant energy balance, spatial distribution of absorbed radiation, and the generation of radical species. Given the nonlinear and multifaceted nature of the degradation process, traditional linear modeling methods often fall short [

6,

7]. To address this limitation, researchers have turned to more sophisticated computational approaches, particularly artificial intelligence (AI) techniques.

Among AI methods, Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs) are especially suited for predicting water quality and simulating complex treatment processes [

8,

9]. By capturing both linear and nonlinear relationships without requiring explicit mathematical formulations, ANNs can effectively model intricate photochemical and sonophotocatalytic systems [

10,

11]. Over the past decade, ANN-based models have seen widespread use in environmental engineering, including photochemical water treatment [

12], activated sludge processes [

13], real-time control in wastewater treatment plants [

14], dye removal via AOPs [

15,

16], and river pollution monitoring through biochemical oxygen demand analysis [

17].

Recent investigations have further demonstrated the utility of ANNs for modeling herbicide degradation in AOPs. Examples include optimizing solar photo-Fenton processes for herbicide mixtures [

18] and modeling the TiO₂-mediated photocatalytic degradation of atrazine [

19]. However, few studies have thoroughly explored ANN-based approaches for predicting and optimizing sonophotocatalytic processes.

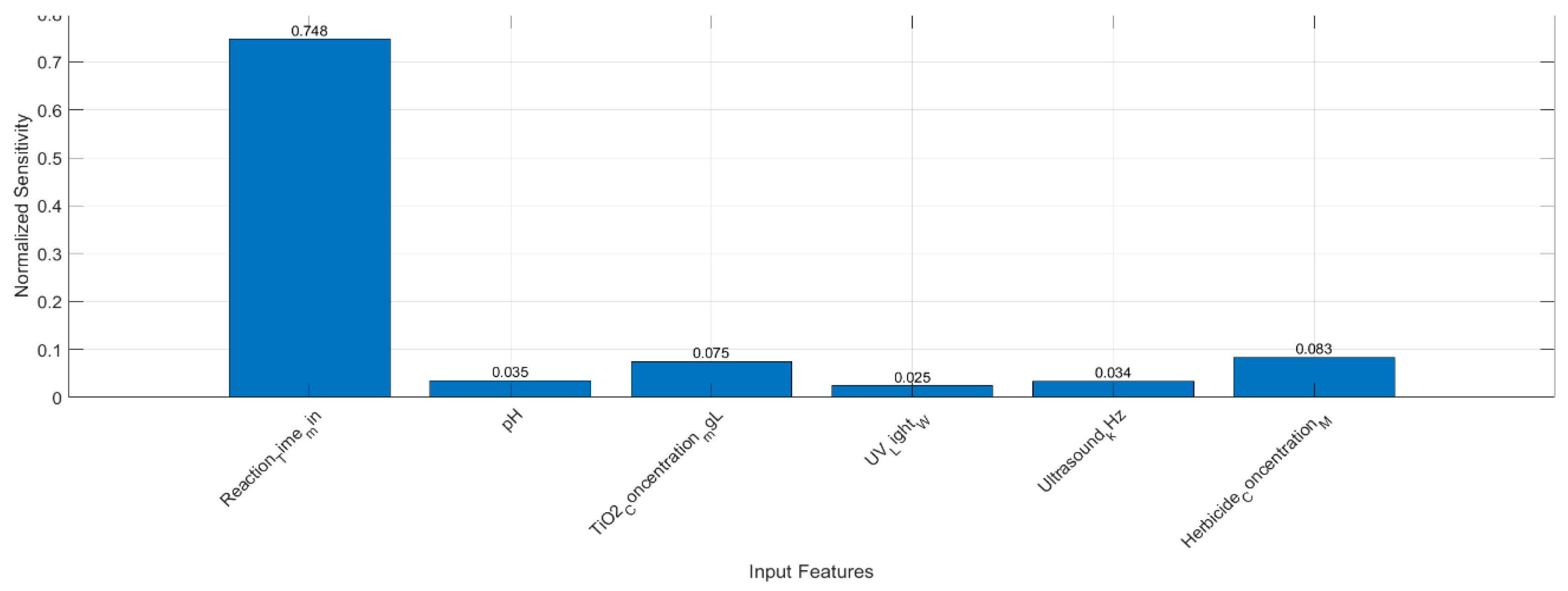

In this context, the present work pursues two main objectives. First, we develop a multilayer feed-forward neural network trained with various backpropagation algorithms to reliably predict Chemical Oxygen Demand (COD) removal during the sonophotocatalytic degradation of alazine and gesaprim herbicides in TiO₂ suspensions under UV irradiation. Second, we perform a sensitivity analysis to identify the most influential parameters governing COD removal efficiency.

Overall, this study contributes to the growing body of literature on AI-driven environmental remediation, emphasizing ANN’s capability for modeling and optimizing AOPs in herbicide-laden wastewater. By harnessing the predictive strength of ANNs and employing systematic sensitivity analyses, we aim to advance the design and operational strategies of wastewater treatment processes, ultimately improving their efficiency and effectiveness for large-scale applications.

2. Related Works

This section reviews significant research on herbicide degradation, wastewater treatment, and the application of Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs) in these fields. Numerous studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of ANNs in modeling complex environmental processes, including water quality monitoring, real-time plant operation, and advanced oxidation processes (AOPs).

2.1. ANN Applications in Wastewater Treatment

Several researchers have explored ANN-based frameworks to enhance wastewater treatment operations. For instance, an ANN-driven intelligent monitoring system was proposed to track key variables in real-time [

13], underscoring the role of machine learning in improving both monitoring and control. Similarly, another study utilized a hybrid ANN–genetic algorithm approach to model and optimize activated sludge bulking [

14], illustrating how ANNs can be combined with optimization techniques to address operational challenges in wastewater plants.

2.2. ANN Models for Predicting Water Quality Parameters

The predictive capabilities of ANNs have also been widely employed in modeling specific water quality indicators. In one study, ANNs were coupled with response surface methodology to model dye removal by adsorption onto water treatment residuals [

15], showcasing the synergy between ANNs and statistical modeling tools. Other work successfully applied ANNs to predict the combined toxicity of phenol and cadmium in wastewater treatment [

16], demonstrating their ability to handle multi-component systems. A broader review of machine learning applications in water quality management further highlighted ANNs as a robust tool for both prediction and optimization [

17].

2.3. ANNs in Herbicide Degradation and Advanced Oxidation Processes

Moving toward herbicide-specific applications, ANNs have been employed to optimize solar photo-Fenton processes for degrading herbicide mixtures [

18]. This research is particularly pertinent to AOPs, revealing how neural network–based models can facilitate more efficient pollutant breakdown. A comprehensive review of AOPs also emphasized the integration of ANNs with two- and multi-way calibration methods, reinforcing the value of neural networks in managing the inherent complexity of oxidation processes [

19].

2.4. Environmental Fate of Herbicides

Studies focusing on herbicide persistence underscore the importance of advanced treatment technologies for contaminated waters [

1,

2]. In addition to environmental impact considerations, food safety concerns drive ongoing efforts to develop more effective and sustainable remediation strategies [

3]. These findings further validate the need for targeted research on innovative degradation methods.

2.5. Advanced Oxidation Processes for Herbicide Degradation

Sonophotocatalysis, involving simultaneous ultrasound and photocatalytic treatment, has shown promise for degrading persistent herbicides [

4,

5]. These processes are inherently complex, involving radical generation, energy transfer, and a multitude of reaction pathways. Consequently, modeling them requires sophisticated data-driven tools such as ANNs to capture nonlinear interactions and optimize operational parameters.

Uniqueness of the Present Work

While the aforementioned studies highlight the growing importance of ANNs for wastewater treatment and herbicide degradation, none directly compare to the specific aims of this work. Here, we focus on evaluating multiple backpropagation algorithms within ANN models to predict Chemical Oxygen Demand (COD) removal during the sonophotocatalytic degradation of commercial herbicides. Additionally, we integrate a sensitivity analysis to pinpoint the most influential parameters governing COD removal. Furthermore, unlike previous approaches, we have developed a detailed “Neural Networks for Statistical Modeling” methodology, accompanied by a comprehensive Graphical User Interface (GUI) and advanced statistical tests, specifically tailored to scientifically predict the degradation of commercial herbicides. This distinctive combination of algorithmic comparison, in-depth statistical modeling, parameter sensitivity analysis, and user-friendly tools provides novel insights into optimizing herbicide degradation processes, thereby contributing a fresh perspective to the existing body of research.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Chemicals

The commercial herbicides used in this study were Alazine (30/18 LM) and Gesaprim (90 GDA), both obtained directly from Syngenta Crop Protection Inc. (USA). Alazine (30/18 LM) is a complex formulation that contains 30% w/v of alachlor (2-chloro-2’,6’-diethyl-N-methoxymethylacetanilide) and 18% w/v of atrazine (2-chloro-4-ethylamino-6-isopropylamino-1,3,5-triazine) along with various formulating agents. Gesaprim (90 GDA), on the other hand, comprises 90% w/w atrazine and is widely employed for pre- and post-emergence weed control in numerous crop systems.

Titanium dioxide (TiO₂) Degussa P25—sourced from Sigma-Aldrich without further modification—was used as the photocatalyst. P25 is considered a “gold standard” in photocatalytic research due to its well-documented physicochemical properties and consistent performance in degrading organic pollutants. Sulfuric acid (Sigma-Aldrich) was employed for pH adjustments throughout the experiments, ensuring precise control of reaction conditions.

No additional purification or pretreatment was performed on the chemicals to better simulate real-world conditions, where commercial herbicides are often discharged with their full range of formulating agents. Distilled water (Baxter México S.A.) was used for all experiments to minimize interference from background impurities that could affect either the degradation rates or Chemical Oxygen Demand (COD) measurements.

3.2. Herbicide Degradation Experiments

The experimental design was adapted from a Hach Company protocol [

20], allowing for methodological consistency and direct comparability with established wastewater treatment practices. The photodegradation experiments were conducted on both Alazine and Gesaprim in a recirculating photochemical reactor:

3.2.1. Reactor Configuration

A total volume of 250 mL of herbicide solution was processed at a constant flow rate of 5.63 L·min-1, ensuring uniform contact of the solution with the photocatalyst and ultrasonic probe. Recirculation-based reactors are widely used benchmarks in photocatalytic research, owing to their reproducible flow patterns and even distribution of reactants.

3.2.2. Ultrasonic Cell Setup

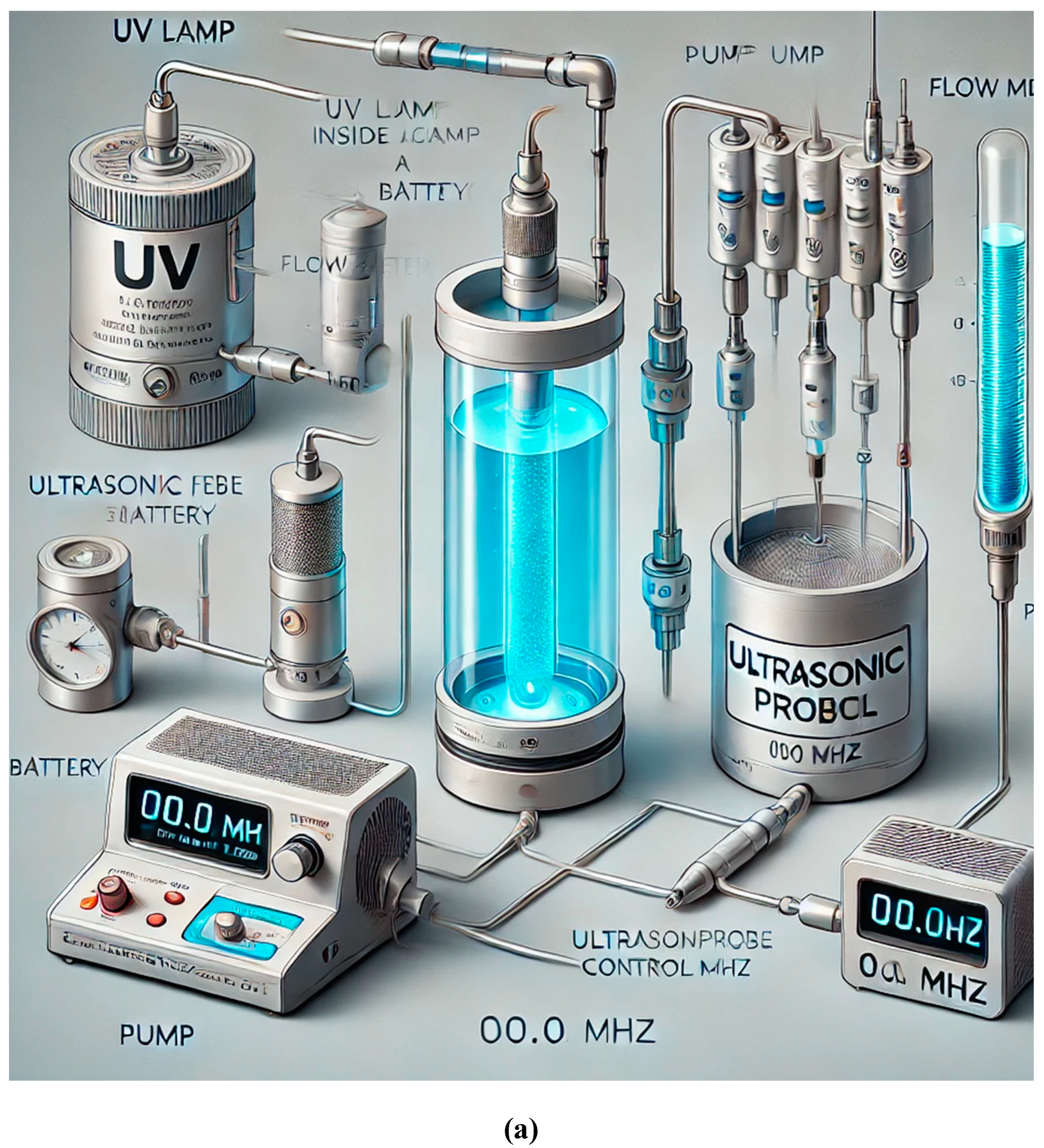

A jacketed ultrasonic cell (150 cm³ capacity) served as the core reaction chamber (

Figure 1). Equipped with an ultrasonic probe (500 W, 20 kHz, Cole Parmer), the cell generated high-frequency waves that produced cavitation bubbles. Upon collapse, these bubbles generate localized microenvironments of extreme temperature and pressure, thereby enhancing chemical degradation.

3.2.3. Temperature Control

Water recirculation through the jacketed cell maintained a stable temperature during sonophotocatalysis, isolating the effects of ultrasound and photocatalysis from thermal decomposition. Such temperature regulation is a key step in benchmark experiments, ensuring that observed degradation is attributable to the intended oxidative processes.

3.2.4. UV Irradiation

A 15 W UV lamp (352 nm, Cole Parmer) was positioned to irradiate the reactor contents. The selected wavelength efficiently excites TiO₂, creating electron–hole pairs that drive photodegradation reactions. This approach is a standard method in photocatalytic studies, facilitating direct comparison of results across different laboratories.

3.2.5. Sampling Protocol

Samples were withdrawn at predetermined intervals, ensuring that the total volume removed did not exceed 10% of the initial 250 mL. This minimized disturbances to the reaction kinetics, a practice aligned with established sampling protocols in sonophotocatalytic research.

3.2.6. Sample Filtration and Analysis

- ➢

Immediately following collection, each sample was filtered to remove suspended TiO₂ particles that might interfere with subsequent analyses. High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) was then used to quantify atrazine and alachlor concentrations.

- ➢

Chemical Oxygen Demand (COD) was measured using standard methods and commercially available Hach COD test tubes, providing a comprehensive overview of the organic load reduction during the degradation process. Adhering to Hach or APHA-based COD protocols ensures that data are consistent with benchmarks in environmental testing.

This integrated approach allowed for a thorough investigation of the sonophotocatalytic degradation of both Alazine and Gesaprim. By leveraging P25 TiO₂, adhering to standardized Hach methodologies, and maintaining precise control over reaction parameters, the study aligns with recognized benchmarks in photocatalytic and environmental engineering research. Consequently, the resulting data on the degradation kinetics of alachlor and atrazine—alongside overall COD reduction—can be reliably compared to similar studies worldwide.

3.3. Sonophotocatalytic Process

Sonophotocatalysis combines sonolysis with TiO₂ photocatalysis under UV irradiation (λ ≤ 400 nm), generating highly reactive oxidant species capable of breaking down toxic, non-biodegradable organic pollutants into relatively harmless end products such as CO₂, H₂O, and mineral acids [

18].

In this process, the active herbicide compounds (alachlor and atrazine) adsorbed onto the TiO₂ surface are oxidized by these reactive species. When TiO₂ is illuminated by photons (hν), charge carriers (electron–hole pairs) form, initiating the oxidative reactions that drive pollutant degradation [

19]. The simplified mechanism can be represented by Equation (1):

The photogenerated electron–hole pairs (e

cb-) in the conduction band and (h

vb+) in the valence band) migrate to the TiO₂ surface, where they react with species such as H₂O, OH⁻, and O₂ to form highly reactive hydroxyl radicals (·OH), superoxide radicals (O₂·⁻), and hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂) [

20,

21]. Simultaneously, ultrasonic irradiation induces cavitation microbubbles, generating localized hot spots with transient high pressures (∼50,000 kPa) and temperatures (∼5,000 K) [

22]. The ensuing shock waves enhance mass transfer and further activate the TiO₂ surface, as described in Eq. (2), thereby accelerating the decomposition of the herbicides’ active compounds. Ultimately, these compounds are oxidized by the reactive species formed during sonophotocatalysis, leading to a marked reduction in Chemical Oxygen Demand (COD).

3.4. Experimental

Alazine contains alachlor, atrazine, and various formulating agents, whereas Gesaprim primarily consists of atrazine and formulating agents. Both herbicide formulations were obtained from Syngenta Crop Protection, Inc. (USA). Titanium dioxide (TiO₂, Degussa P25) and sulfuric acid (H₂SO₄) were of analytical grade (Sigma–Aldrich). Further details on the apparatus, experimental setup, and procedures are provided in [

2].

Briefly, a series of photodegradation experiments for each herbicide was carried out in a photochemical reactor operating in recirculating mode, using a total volume of 250 mL at a flow rate of 5.63 L·min⁻¹. The reactor featured a jacketed ultrasonic cell (150 cm³) with an ultrasonic probe (500 W, 20 kHz, Cole Parmer). Temperature control was maintained via water recirculation, and a UV lamp (15 W, 352 nm, Cole Parmer) was used to activate photocatalysis. Samples were withdrawn at predetermined intervals to measure Chemical Oxygen Demand (COD) using standard methods and commercially available test tubes [

23].

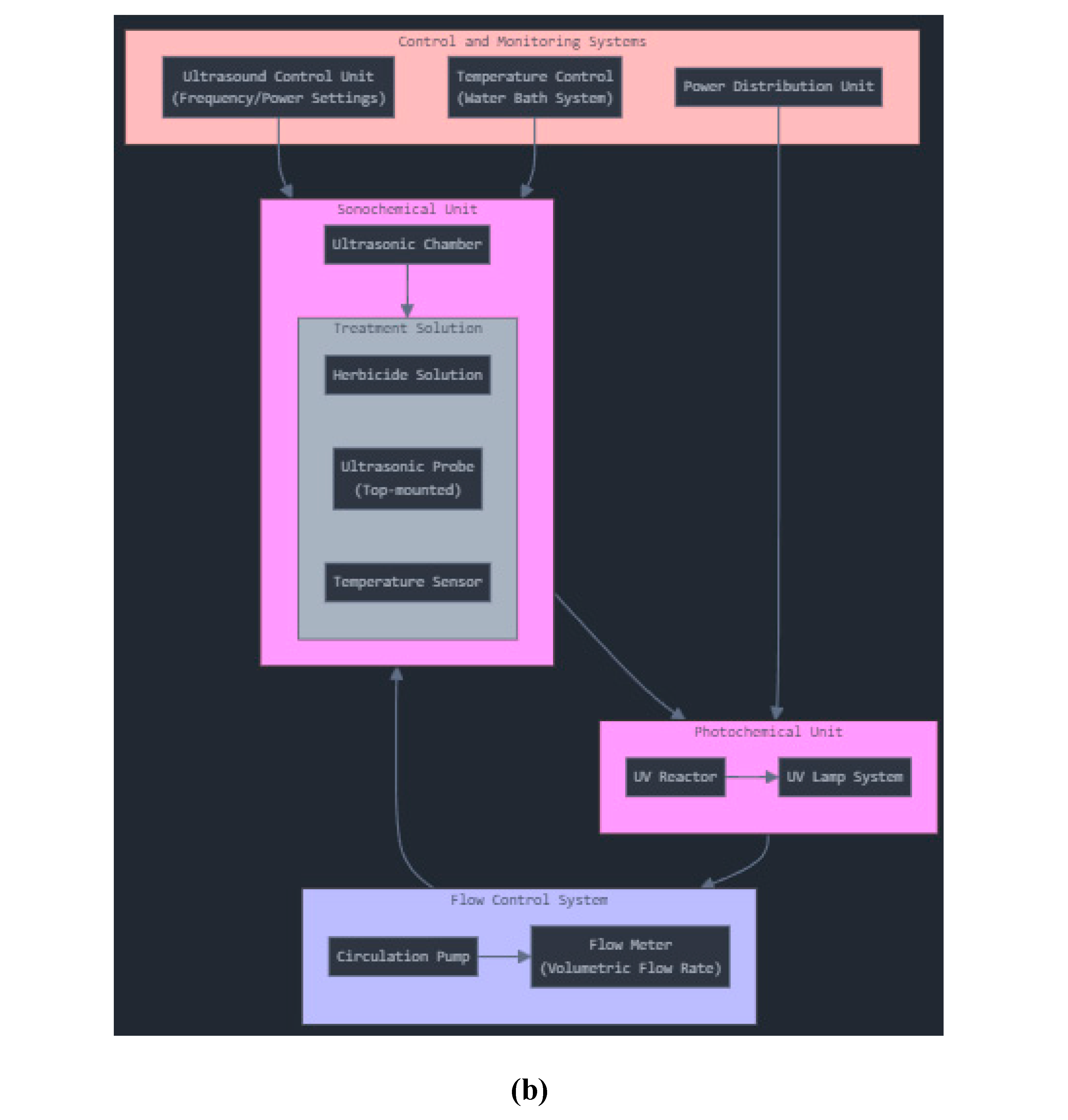

Table 1 presents the experimental COD values for Alazine and Gesaprim, along with the corresponding reactions for mineralizing the active compounds in each herbicide. The photochemical reactor setup for herbicide removal is illustrated in

Figures 1(a) and 1(b).

4. Exploratory Data Analysis

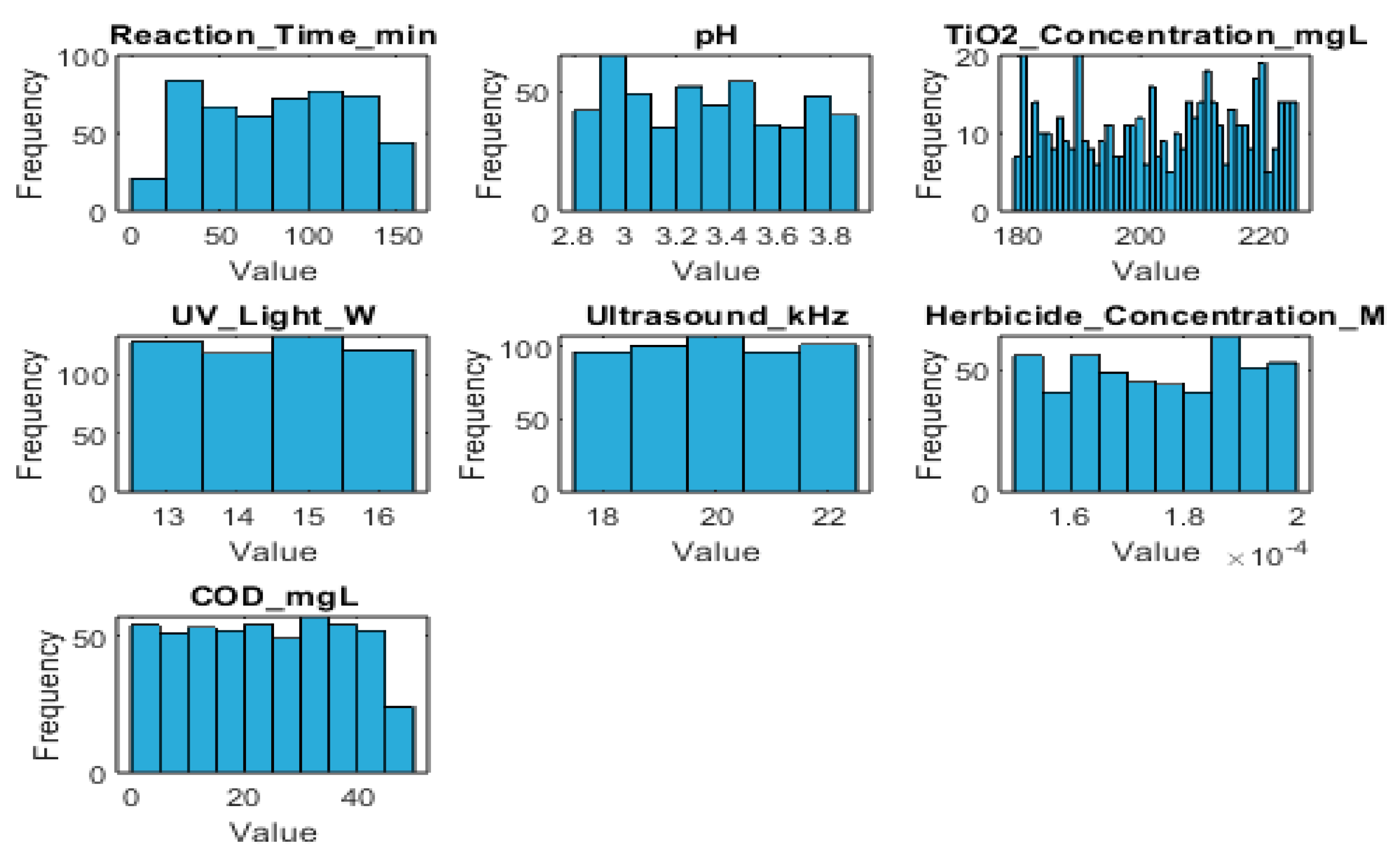

This section presents a comprehensive exploratory data analysis (EDA) of a synthetic herbicide dataset, aiming to uncover distributions, relationships, patterns, and potential data quality issues. The primary goal is to establish a thorough understanding of the dataset, serving as a solid foundation for more advanced modeling. The EDA encompasses eight key tasks:

- 1.

-

Data Loading and Inspection

- ○

The dataset was initially examined by viewing sample rows and assessing structural integrity (e.g., data types, missing values).

- ○

Summary statistics (mean, median, standard deviation) were computed to provide an initial overview of each variable.

- 2.

-

Data Visualization

- ○

Histograms and box plots were generated for each continuous variable, including Reaction Time (min), pH, TiO₂ Concentration (mg/L), UV Light (W), Ultrasound (kHz), Herbicide Concentration (M), and COD (mg/L).

- ○

Pair plots and correlation heatmaps were used to illustrate inter-variable relationships.

- ○

Time series plots captured changes in Herbicide Concentration over Reaction Time, while scatter plots provided insights into pairwise interactions.

- 3.

-

Detailed Statistics

- ○

A correlation matrix offered a visual map of how variables relate to each other.

- ○

Univariate analysis (density plots, histograms) and bivariate analysis (scatter, box, violin plots) delved deeper into each variable’s distribution and pairwise relationships.

- 4.

-

Handling Missing Values

- ○

Missing data points were identified and visualized.

- ○

Various imputation strategies (e.g., mean or median imputation) were explored and applied to achieve a complete dataset suitable for analysis.

- 5.

-

Outlier Detection

- ○

Box plots and scatter plots highlighted potential outliers.

- ○

Identified anomalies were considered for possible exclusion or transformation, depending on their impact on subsequent modeling.

- 6.

-

Distribution Analysis

- ○

Each continuous variable was assessed for normality.

- ○

Suggested transformations were discussed for variables significantly deviating from normal distributions.

- 7.

-

Target Variable Analysis

- ○

Special attention was paid to the target variable, COD (mg/L).

- ○

Its distribution and relationships with other variables were thoroughly evaluated and visualized.

- 8.

-

Final Summary and Insights

- ○

The EDA concluded with a synthesis of major findings, highlighting data patterns and quality.

- ○

These insights set the stage for more informed decision-making in subsequent modeling tasks.

The dataset contains 500 entries and 7 columns, representing the following variables:

Reaction_Time_min (Integer): Reaction time in minutes.

pH (Float): pH values.

TiO2_Concentration_mgL (Integer): Titanium dioxide concentration in mg/L.

UV_Light_W (Integer): UV light intensity in Watts.

Ultrasound_kHz (Integer): Ultrasound frequency in kHz.

Herbicide_Concentration_M (Float): Herbicide concentration in molarity (M).

COD_mgL (Float): Chemical Oxygen Demand in mg/L.

Next, descriptive statistics—such as mean, median, mode, standard deviation, and range—will be computed for these variables to provide additional insights into the dataset’s structure and variability.

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

A summary of the descriptive statistics for each variable in the dataset is provided below:

- 1.

-

Reaction Time (min)

- ○

Mean: 82.32

- ○

Median: 84.00

- ○

Mode: 53.00

- ○

Standard Deviation: 40.63

- ○

Range: 15.00 to 150.00 (135.00 total)

- 2.

-

pH

- ○

Mean: 3.33

- ○

Median: 3.32

- ○

Mode: 2.95

- ○

Standard Deviation: 0.31

- ○

Range: 2.81 to 3.90 (1.09 total)

- 3.

-

TiO₂ Concentration (mg/L)

- ○

Mean: 203.29

- ○

Median: 204.00

- ○

Mode: 181.00

- ○

Standard Deviation: 13.66

- ○

Range: 180.00 to 225.00 (45.00 total)

- 4.

-

UV Light (W)

- ○

Mean: 14.49

- ○

Median: 15.00

- ○

Mode: 15.00

- ○

Standard Deviation: 1.12

- ○

Range: 13.00 to 16.00 (3.00 total)

- 5.

-

Ultrasound (kHz)

- ○

Mean: 20.01

- ○

Median: 20.00

- ○

Mode: 20.00

- ○

Standard Deviation: 1.40

- ○

Range: 18.00 to 22.00 (4.00 total)

- 6.

-

Herbicide Concentration (M)

- ○

Mean: 0.000175

- ○

Median: 0.000175

- ○

Mode: 0.000164

- ○

Standard Deviation: 0.000015

- ○

Range: 0.000150 to 0.000200 (0.000050 total)

- 7.

-

Chemical Oxygen Demand (mg/L)

- ○

Mean: 23.68

- ○

Median: 23.77

- ○

Mode: 0.00

- ○

Standard Deviation: 13.77

- ○

Range: 0.00 to 49.53 (49.53 total)

These statistics serve as an essential foundation for comprehending the herbicide degradation process and can guide further experimental design and optimization efforts.

Figure 2 presents the histogram frequency distributions for each variable.

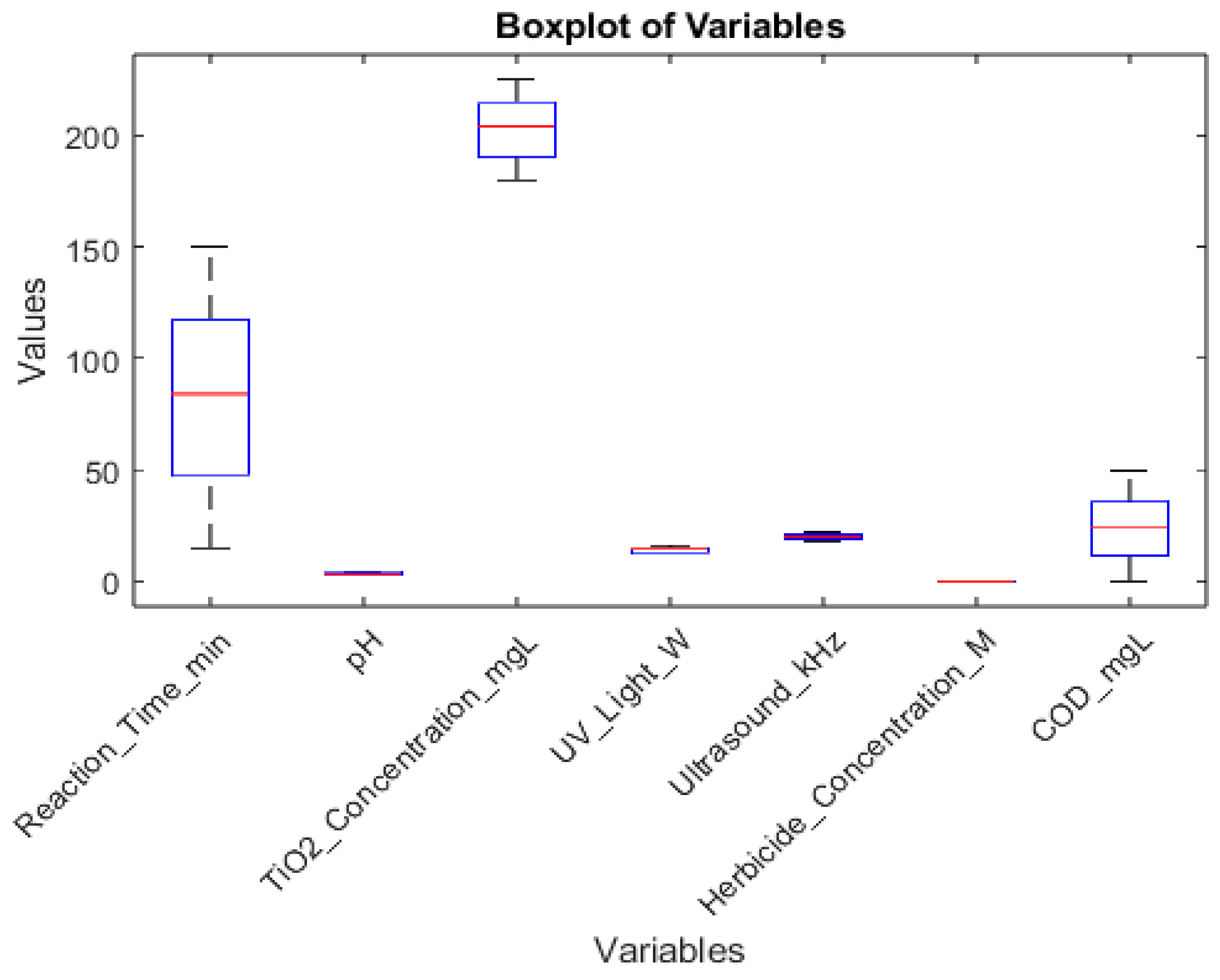

Boxplots (

Figure 3) are indeed a very effective way to represent the performance of different neural network algorithms, especially when comparing multiple runs. Here's why boxplots are particularly useful in this context:

Distribution visualization: Boxplots show the entire distribution of results, including the median, quartiles, and potential outliers. This gives a comprehensive view of how each algorithm performs across multiple runs.

Easy comparison: With boxplots side by side, it's easy to compare the performance of different algorithms at a glance. You can quickly see which algorithms have higher medians, less variability, or more consistent results.

Variability assessment: The box in a boxplot represents the interquartile range (IQR), which shows the spread of the middle 50% of the data. This helps in understanding how consistent each algorithm is across different runs.

Outlier detection: Boxplots clearly show outliers as individual points, making it easy to identify runs that performed unusually well or poorly.

Compact representation: Boxplots can display a lot of information in a compact form, which is especially useful when comparing multiple algorithms or metrics.

Non-parametric: Boxplots do not assume any underlying distribution of the data, making them suitable for various types of performance metrics.

Robustness: The median and quartiles used in boxplots are less sensitive to extreme values compared to means, providing a more robust representation of central tendency.

While other representations like bar charts or line plots can be useful for certain aspects, boxplots provide a more comprehensive view of the data distribution, which is crucial when assessing the performance and reliability of different neural network training algorithms across multiple runs.

4.2. Relationships Between Variables

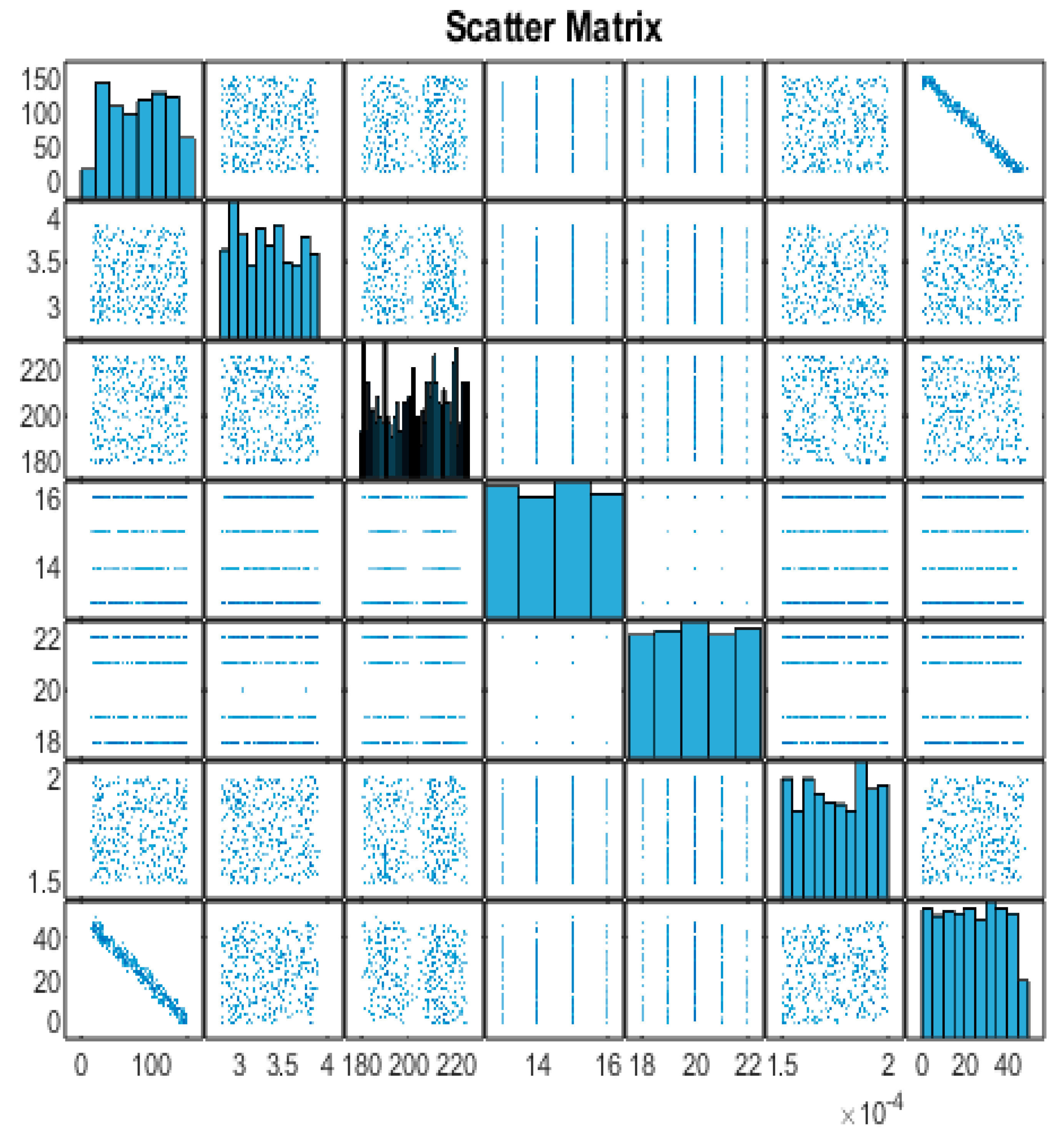

Next, we will create a scatter matrix to visualize the relationships between the variables (

Figure 4). The scatter matrix provides a visual representation of the relationships between the variables in the dataset. Each scatter plot shows the relationship between two variables, and the histograms on the diagonal represent the distribution of each variable. However,

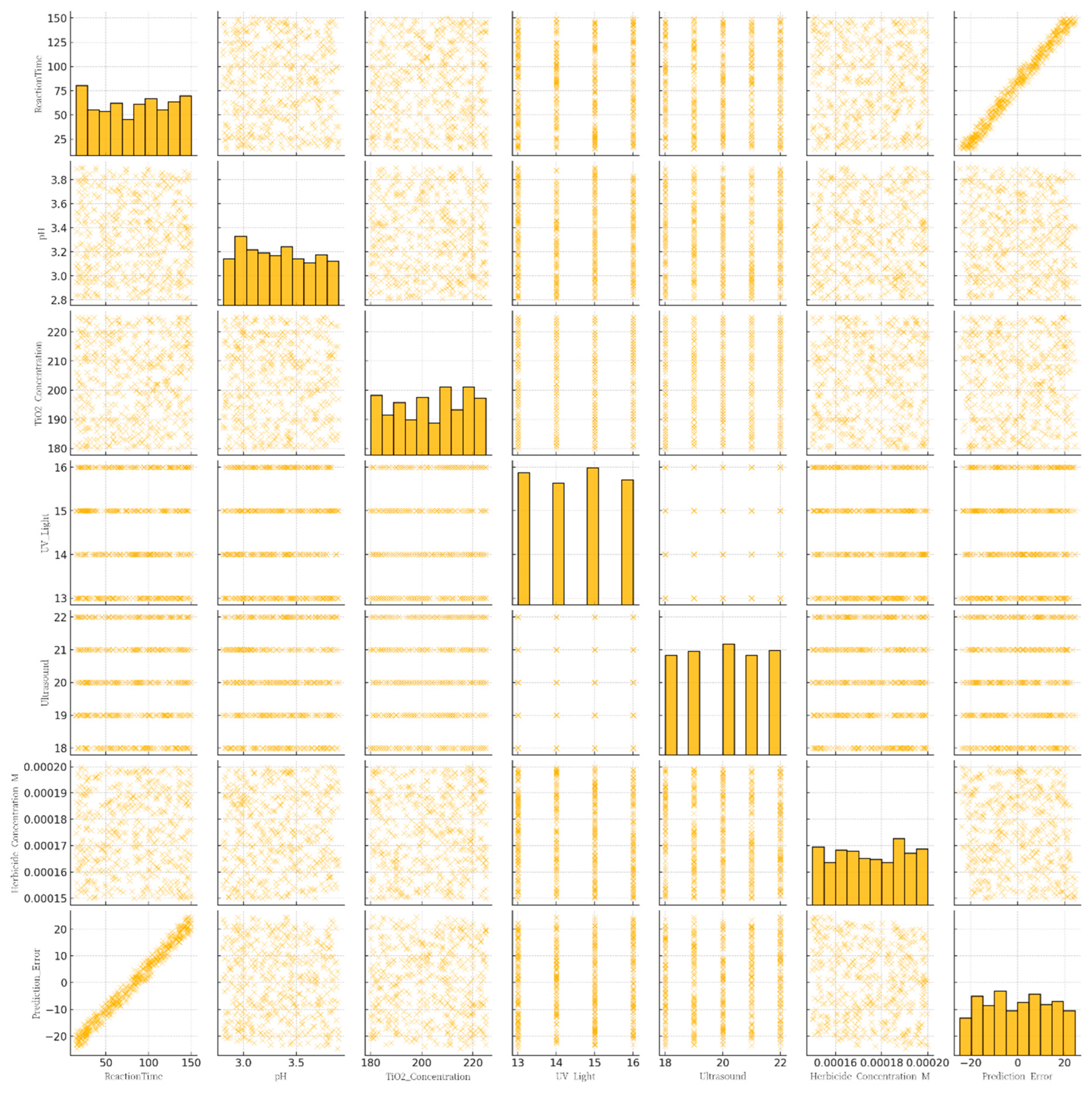

Figure 5 shows Pair plot of prediction errors across different experimental conditions.

This multi-panel figure displays a pairwise comparison (pair plot) among seven variables: Reaction Time (minutes), pH, TiO₂ Concentration (mg/L), UV Light (Watts), Ultrasound (kHz), Herbicide Concentration (M), and the model’s Prediction Error (COD). Each diagonal cell shows a histogram reflecting the distribution of a single variable, while the off-diagonal cells are scatter plots depicting the relationship between every pair of variables.

Together, the pair plot provides a quick, comprehensive overview of variable interactions and highlights where modeling inaccuracies are most pronounced, aiding in refining both data-driven models and experimental setups for COD prediction in herbicide-contaminated wastewater.

Therefore, we will create a parallel coordinate plot to analyze the multivariate data that will discuss in section 8. The parallel coordinate plot allows us to analyze the relationships between multiple variables. Each line represents an observation from the dataset, showing how its values across different variables relate to one another, the lines colored based on the herbicide concentration, indicating how variations in other variables correlate with different levels of herbicide concentration. The plot will help to identify clusters and trends among the observations: as the herbicide concentration increases, there might be distinct patterns in COD_mgL, TiO2 concentration, and reaction time.

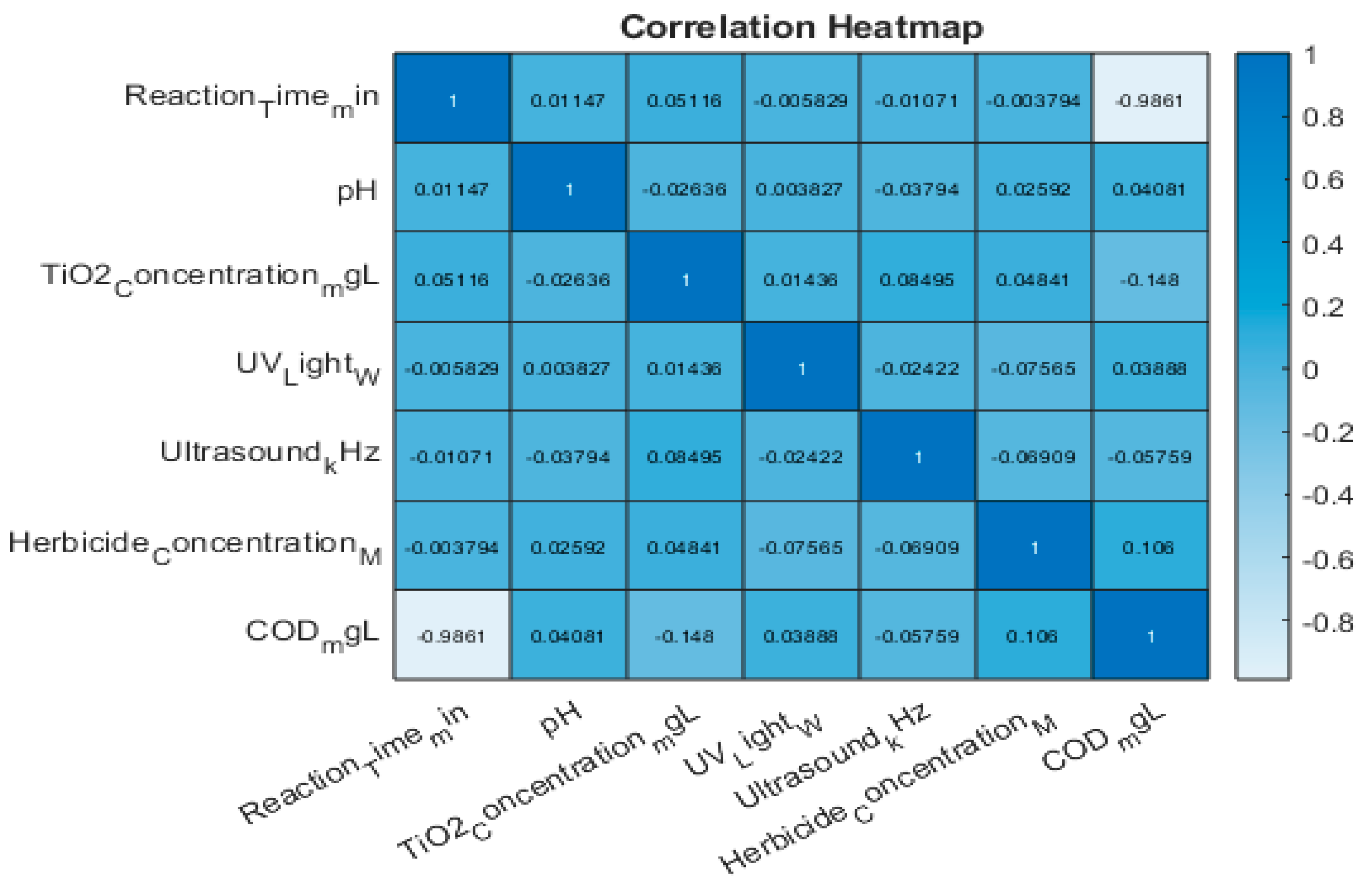

In addition, we will create a heat map based on the Pearson correlation coefficients to identify relationships between the variables that we will discuss extensively in section 7.6.

5. Chemical Oxygen Demand

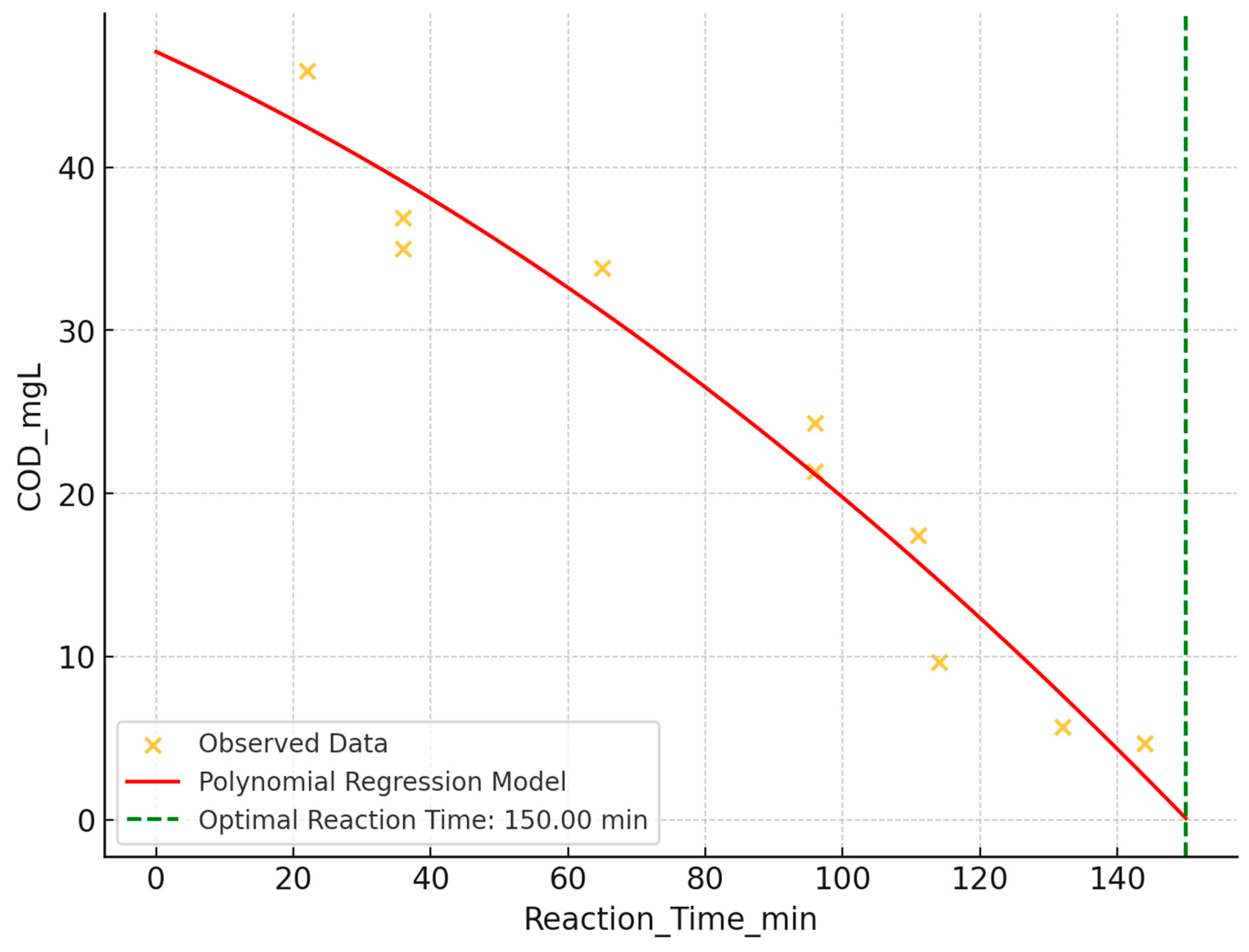

5.1. The Impact of Reaction Time on Chemical Oxygen Demand Reduction

The impact of reaction time on Chemical Oxygen Demand (COD) reduction was analyzed using scatter plot analysis and polynomial regression. A strong negative correlation (r ≈ -0.973) was observed between reaction time and COD levels, indicating significant COD decrease with increased reaction time (

Figure 6). The polynomial regression model suggested an optimal reaction time of approximately 150 minutes for minimizing COD levels.

Visual analysis of the scatter plot with polynomial regression overlay revealed a steep reduction in COD at lower reaction times, gradually leveling off at higher reaction times. This supports the finding that longer reaction times correlate with more effective COD reduction, with an optimal point around 150 minutes, after which diminishing returns were observed.

To further refine these results, additional analyses are recommended, including:

Exploration of higher-degree polynomial or non-linear models for better trend capture.

Application of piecewise regression to accurately model distinct reaction phases.

Incorporation of multivariate analysis to account for additional influential variables (e.g., pH, TiO₂ concentration).

Utilization of model validation techniques and comparison of different models using statistical metrics like Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) or Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC).

These extended analyses could provide deeper insights into the COD reduction process, potentially improving the efficiency and effectiveness of the treatment while considering real-world complexities.

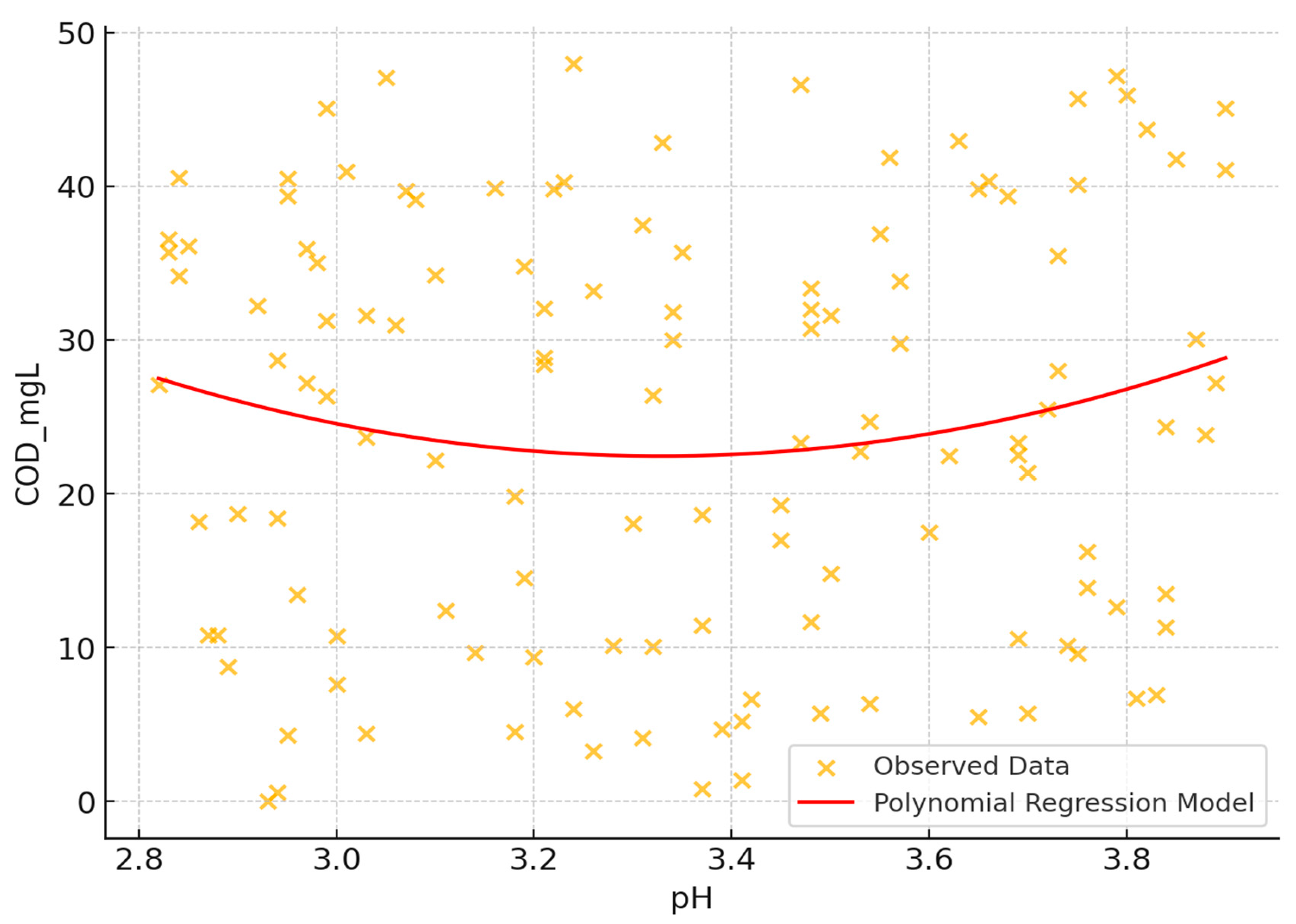

5.2. Investigating the Influence of pH on Chemical Oxygen Demand

The influence of pH on Chemical Oxygen Demand (COD) was investigated using scatter plot analysis and statistical methods. The study examined COD levels ranging from 0 to 50 mg/L across a pH span of 2.8 to 4.0, indicating an acidic environment (

Figure 7).

- 1.

Correlation analysis: A very weak linear relationship between pH and COD was observed, with a correlation coefficient of approximately 0.026. This suggests that pH alone may not significantly influence COD in a linear manner.

- 2.

Visual analysis: The scatter plot revealed wide dispersion of data points without a distinct trend, implying that factors other than pH may substantially contribute to COD fluctuations.

- 3.

Polynomial regression: A second-degree polynomial regression model was fitted to capture potential non-linear relationships. However, given the weak correlation, substantial non-linear effects were not evident.

- 4.

Optimal pH: No clear optimal pH for minimizing COD was identified, reinforcing that pH might not be the sole factor affecting COD reduction.

- 5.

Data complexity: Clustered data points and outliers with very low COD values were observed, indicating a complex interaction between pH and COD, possibly involving other variables not depicted in the scatter plot.

These findings highlight the complexity of the pH-COD relationship and suggest that other factors may play significant roles in COD variation.

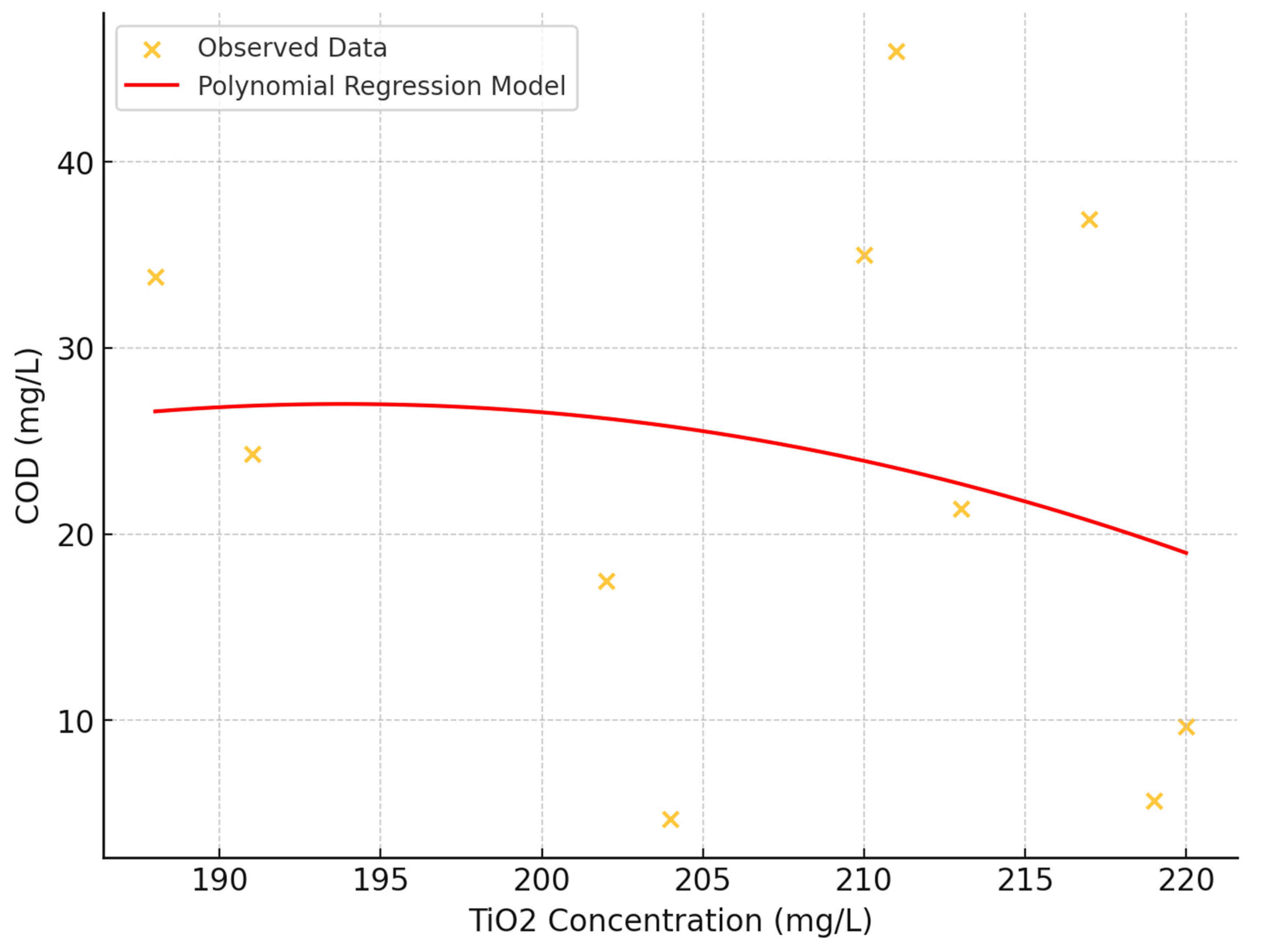

5.3. Evaluating the Impact of TiO2 Concentration on Chemical Oxygen Demand

The impact of TiO₂ concentration on Chemical Oxygen Demand (COD) was investigated using scatter plot analysis and statistical methods. The study examined TiO₂ concentrations ranging from approximately 180 to 225 mg/L and COD levels from 0 to 50 mg/L (

Figure 8).

- 1.

Correlation Analysis: A weak negative linear relationship between TiO₂ concentration and COD was observed, with a correlation coefficient of approximately -0.189. This suggests that as TiO₂ concentration increases, there might be a slight tendency for COD values to decrease, though the relationship is not strong.

- 2.

Visual Assessment: The scatter plot revealed a dispersed arrangement of data points, indicating the absence of a strong linear relationship between TiO₂ concentration and COD. The consistent distribution of COD values across the entire TiO₂ concentration range suggests uniform variability.

- 3.

Polynomial regression: A second-degree polynomial regression model was fitted to capture potential non-linear relationships. However, no strong, straightforward trend was evident.

- 4.

Data Complexity: Vertical clustering of data points, particularly at lower COD levels, was observed, potentially indicating underlying experimental or treatment conditions that warrant further exploration.

- 5.

Absence of Threshold Effect: No distinct outlier pattern or threshold effect was observed where a specific TiO₂ concentration drastically altered COD values.

These findings suggest that while TiO₂ concentration may have a limited direct effect on COD, the relationship is complex and likely influenced by additional factors not captured in this analysis.

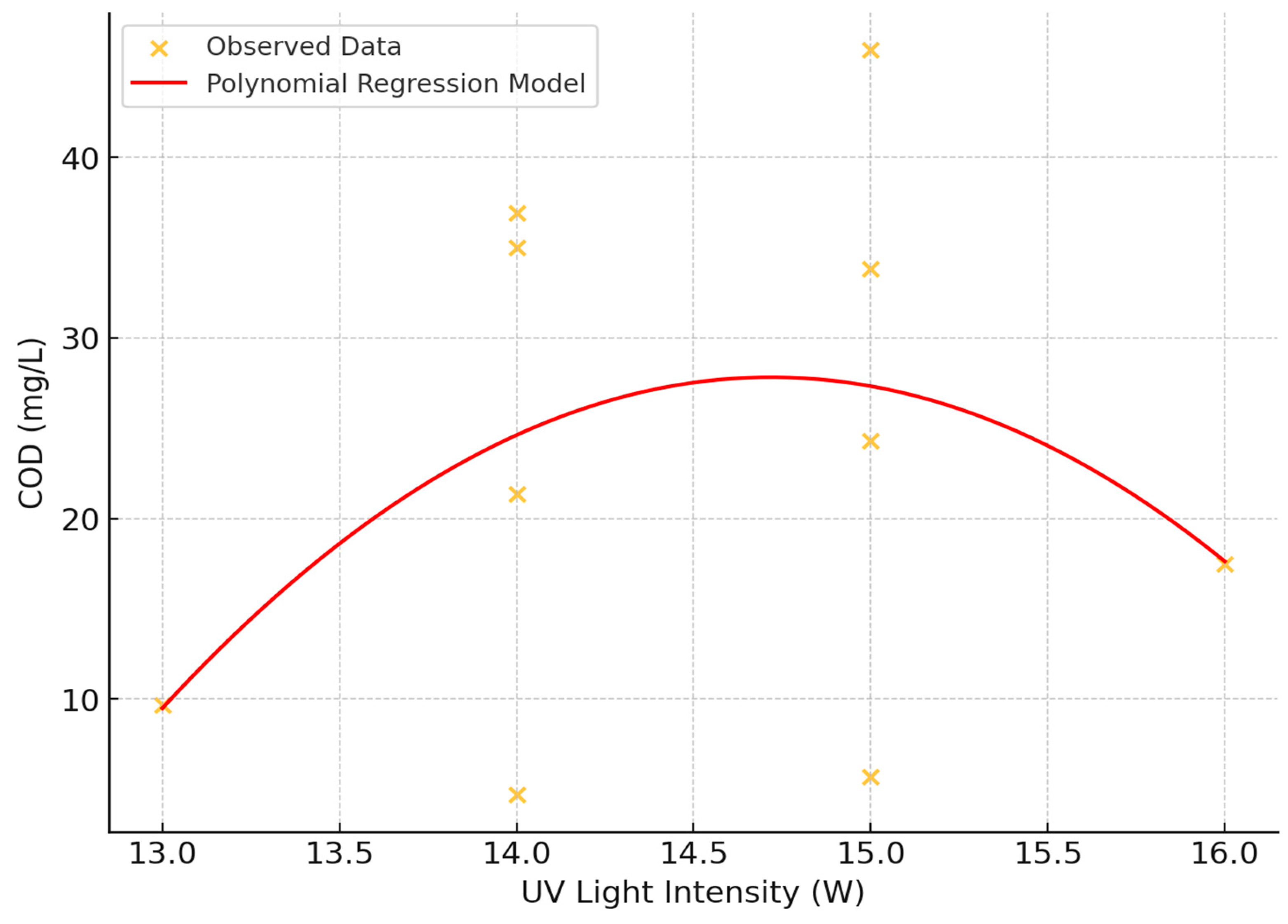

5.4. The Influence of Ultraviolet (UV) Light Intensity on Chemical Oxygen Demand

The impact of Ultraviolet (UV) light intensity on Chemical Oxygen Demand (COD) was investigated using scatter plot analysis and statistical methods (

Figure 9). The study examined UV light intensities ranging from 13 to 16 Watts and COD values from 0 to 50 mg/L.

- 1.

Correlation analysis: A weak positive linear relationship between UV light intensity and COD was observed, with a correlation coefficient of approximately 0.162. This suggests a slight tendency for COD values to increase with increasing UV light intensity, though the relationship is not strong.

- 2.

Visual assessment: The scatter plot revealed a consistent spread and pattern of COD values across all levels of UV exposure, indicating that UV light intensity alone may not exert a strong direct influence on COD within the experimental setup.

- 3.

Polynomial regression: A second-degree polynomial regression model was fitted to capture potential non-linear relationships. However, no clear trend, either linear or non-linear, correlating UV light intensity to COD reduction was observed.

- 4.

Data distribution: High variability in COD values was observed at each UV intensity level, suggesting that other factors may play a significant role in determining COD beyond the influence of UV light alone.

- 5.

Absence of threshold effect: No clear threshold effect was observed where variations in UV light intensity significantly altered COD levels.

These findings indicate that while UV light intensity may have a weak positive correlation with COD, the relationship is complex and likely influenced by additional factors not captured in this analysis. The consistent variability across UV intensities suggests that other variables may be more influential in determining COD levels.

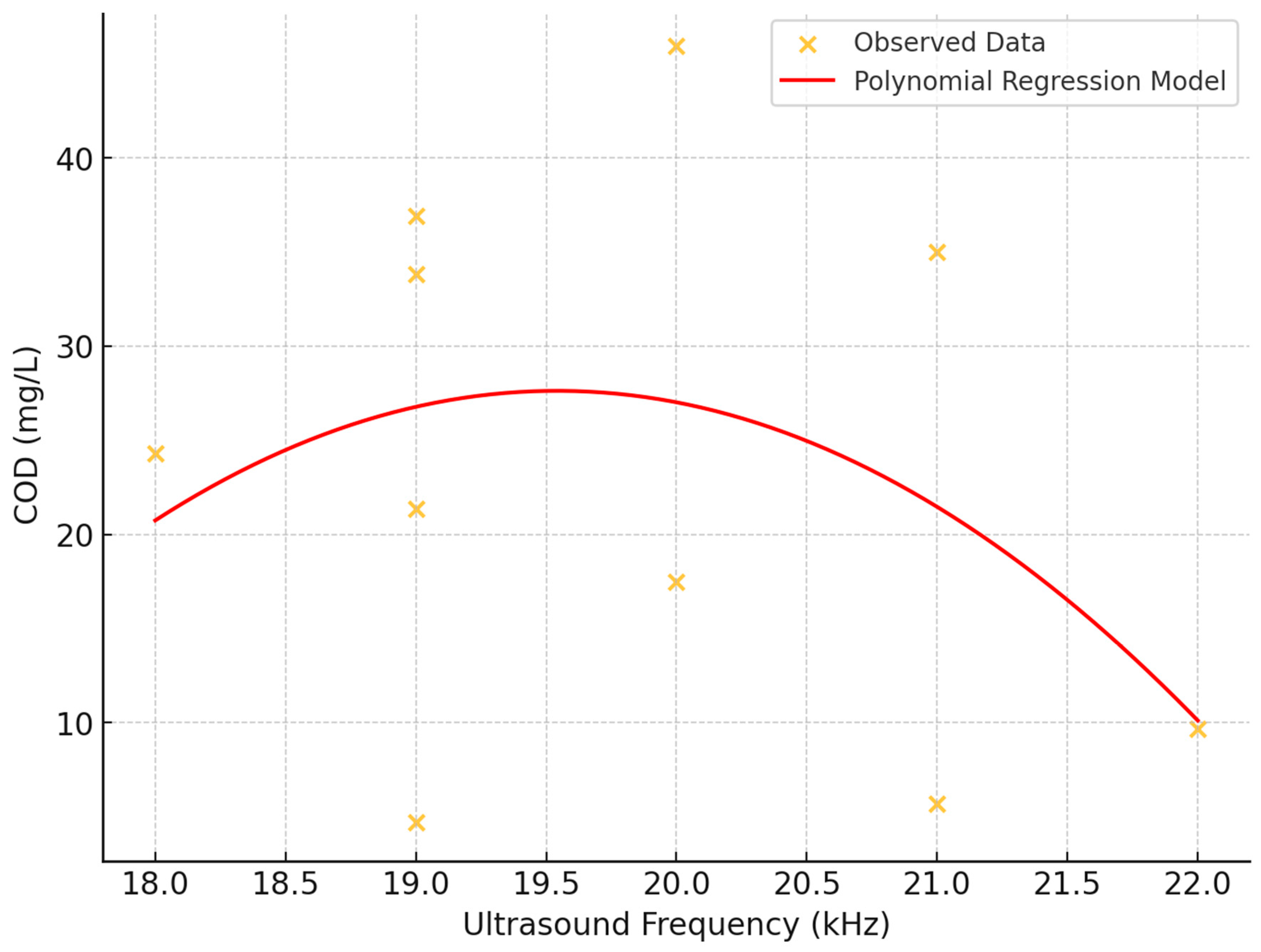

5.5. The Effect of Ultrasound Frequency on Chemical Oxygen Demand (COD)

The impact of ultrasound frequency on Chemical Oxygen Demand (COD) was investigated using scatter plot analysis and statistical methods (

Figure 10). The study examined ultrasound frequencies ranging from 18 to 22 Hz and COD values from 0 to 50 mg/L.

- 1.

Correlation Analysis: A weak negative linear relationship between ultrasound frequency and COD was observed, with a correlation coefficient of approximately -0.244. This suggests a slight tendency for COD values to decrease as ultrasound frequency increases, though the relationship is not strong.

- 2.

Visual Assessment: The scatter plot revealed a consistent and wide variance of COD values across all tested frequencies, indicating that variations in ultrasound frequency within the tested range may not exert a significant direct effect on COD.

- 3.

Polynomial regression: A second-degree polynomial regression model was fitted to capture potential non-linear relationships. However, no discernible trend, either linear or non-linear, emerged between ultrasound frequency and COD levels.

- 4.

Data Distribution: Data density skewed towards lower COD values at all frequency levels, with fewer instances at higher COD values, suggesting the influence of other factors not captured in this analysis.

- 5.

Absence of Threshold Effect: No evident threshold effects were observed where specific ultrasound frequencies dramatically altered COD levels.

These findings suggest that while ultrasound frequency may have a weak negative correlation with COD, the relationship is complex and likely influenced by additional factors not captured in this analysis. The consistent variability across frequencies indicates that other variables may play a more significant role in determining COD levels.

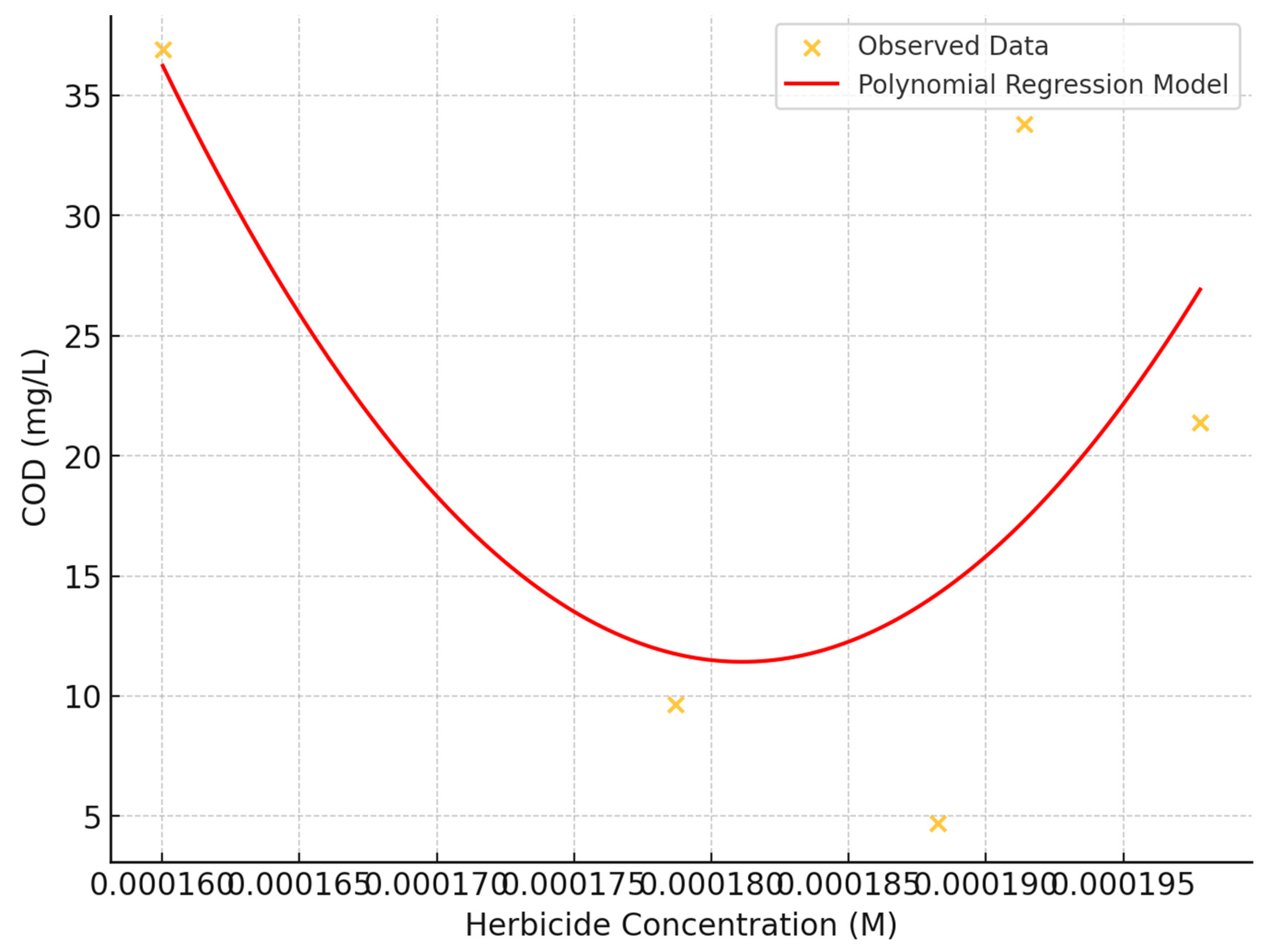

5.6. The Effect of Herbicide Concentration on Chemical Oxygen Demand (COD)

The influence of herbicide concentration on Chemical Oxygen Demand (COD) was investigated using scatter plot analysis and statistical methods (

Figure 11). The study examined herbicide concentrations ranging from approximately:

to

and COD values from 0 to 50 mg/L.

Correlation Analysis: A moderate negative linear relationship between herbicide concentration and COD was observed, with a correlation coefficient of approximately -0.346. This suggests a tendency for COD values to decrease as herbicide concentration increases, though the relationship is not overly strong.

Visual Assessment: The scatter plot revealed a dispersed pattern of data points across the plot, indicating no evident strong linear or non-linear relationship between herbicide concentration and COD.

Polynomial regression: A second-degree polynomial regression model was fitted to capture potential non-linear relationships, helping to visualize nuanced trends beyond simple linear relationships.

Data Distribution: A slightly higher density of data points was noted in the lower to mid-range of COD values (10-30 mg/L) across all herbicide concentrations, suggesting potential complex interactions or influences from variables not captured in this analysis.

Absence of Threshold Effect: No distinct threshold effect was observed where dramatic changes in COD occurred at specific herbicide concentrations.

These findings suggest that while herbicide concentration may have a moderate negative correlation with COD, the relationship is complex and likely influenced by additional factors not captured in this analysis. The consistent variability across concentrations indicates that other variables may play significant roles in determining COD levels.

6. Artificial Neural Network

Inspired by the intricate architecture of the human brain, artificial neural networks consist of neurons organized into distinct layers, with each connection between neurons carrying a unique weight that influences the network's function. Much like in nature, the strength and pattern of these connections are vital in shaping the network's behavior. A commonly used structure for function approximation is the multi-layer perceptron, often referred to as a feed-forward network. This type of network typically features one or more hidden layers composed of sigmoid neurons, followed by an output layer of linear neurons. The hidden layers enable the network to capture both nonlinear and linear relationships between inputs and outputs, while the linear output layer allows the network to generate values beyond the constrained range of –1 to +1. In the realm of neural networks, a two-layer notation is often employed for such configurations, reflecting the layered complexity and potential for learning inherent in these systems.

Table 2 shows Neural Networks Model Development Workflow.

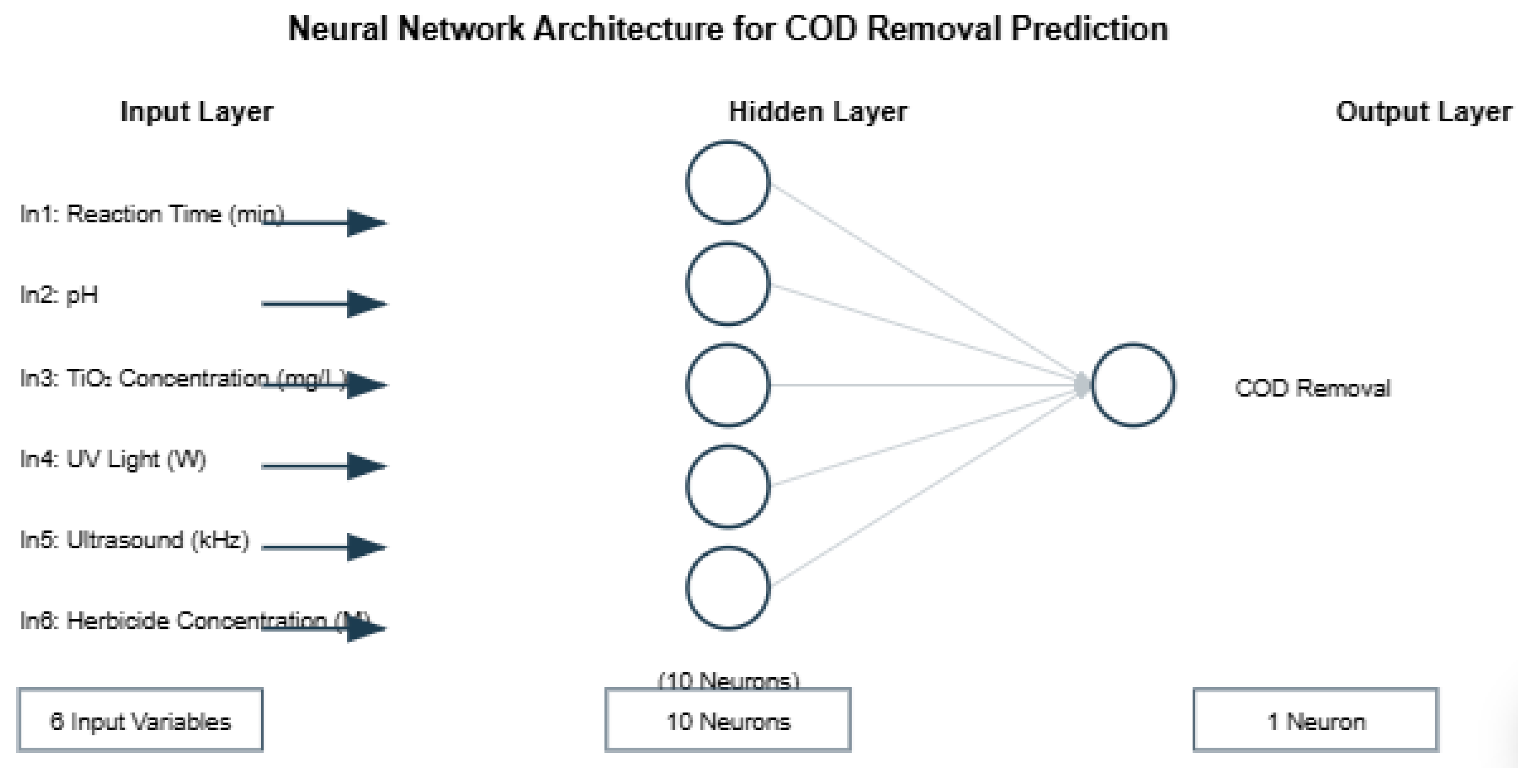

The number of neurons in the input and output layers is given respectively by the number of input and output variables in the process under investigation. In this work, a feed-forward is proposed, the input layer consists of nine variables (reaction time, pH (potential of hydrogen), TiO2 , UV light intensity, Ultrasound frecuency (fUS) and herbicide concentration (HC). However, the output layer contains one variable (COD). The optimal number of neurons in the hidden layer(s) ns is difficult to specify, and depends on the type and complexity of the task. This number is usually determined iteratively. Each neuron in the hidden layer has a bias b (threshold), which was added to the weighted inputs to form the neuron n (Eq. 3). This sum, n, is the argument of the transfer function f.

The number of neurons in the input and output layers was intrinsically tied to the variables we seek to understand within a given process. In this study, we propose a feed-forward network where the input layer encompasses nine key variables: reaction time, pH (potential of hydrogen), TiO2 concentration, UV light intensity, ultrasound frequency (fUS), and herbicide concentration (HC). These inputs collectively guide the network towards a single output variable—COD. Determining the optimal number of neurons within the hidden layers is a nuanced challenge, influenced by the complexity and nature of the task at hand. This optimal number is typically found through iterative refinement. Each hidden neuron carries a bias (threshold) that, when combined with the weighted inputs, forms the neuron's output (n), which is then passed through the transfer function (f). This process, though technical, echoes the underlying elegance of neural networks in their ability to model and understand complex relationships within data.

A structure capable of being trained with data will be able to follow the model over time. So, a single-layer ANN with inputs

and a single output

, is proposed. The proposed ANN model with

hidden neurons takes the form:

where the column vectors

and

of size

contain the inputs and output weights, respectively. The same size vector

contains the input biases while the scalar

contains the output bias. However, the function

stands for the activation function, which, in this case, after some exploration, the hyperbolic tangent sigmoid transfer function was selected, which takes the form as Eq. 4.

It is applied to all the elements of its input vector , with which for a network with 10 hidden nodes. While a linear transfer function (PURELIN) was selected for the output layer. Indeed, the activations functions play an essential role in achieving good performance.

If considering the transfer functions, in the account that, the Eq. 5 may be expressed as follows:

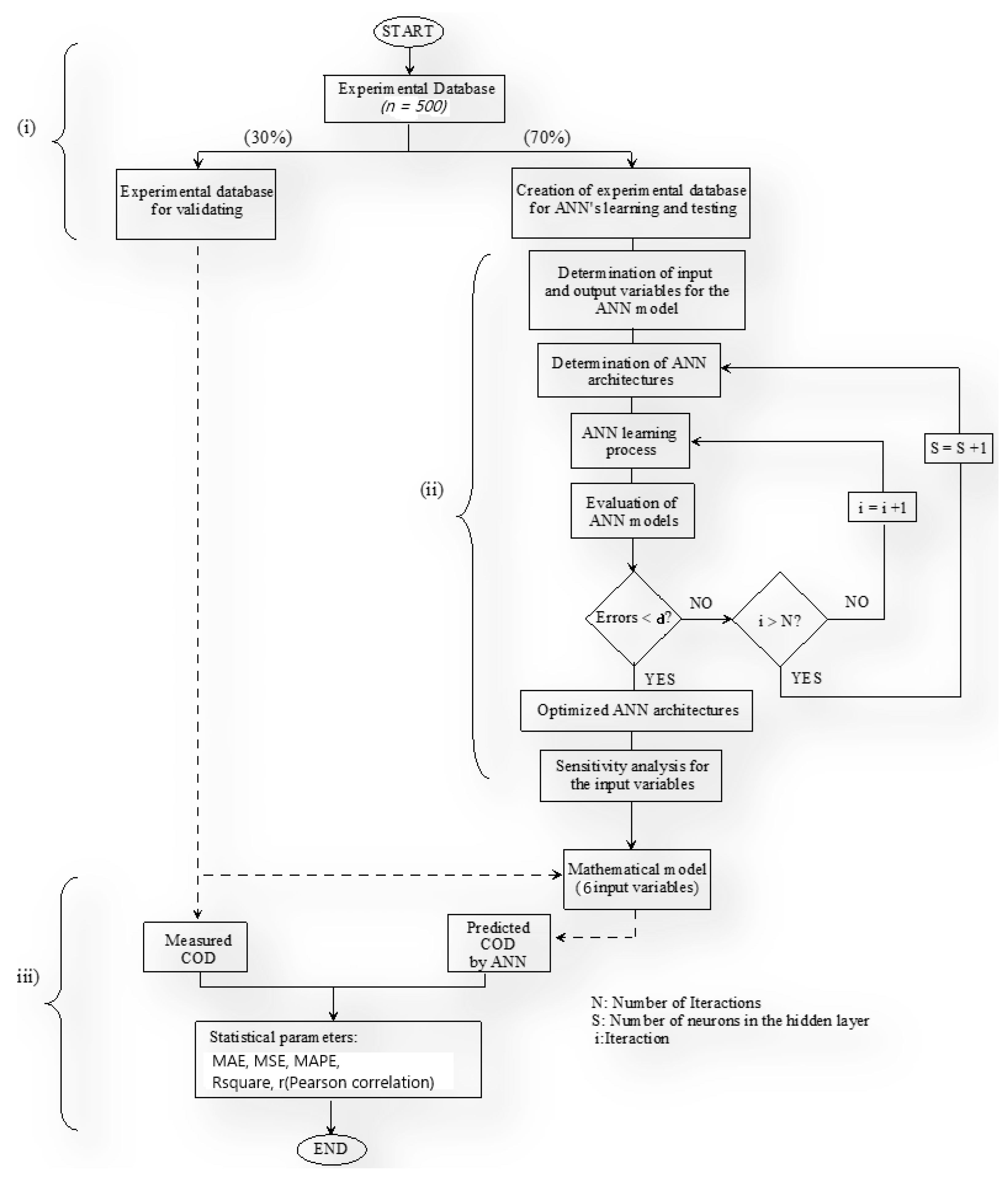

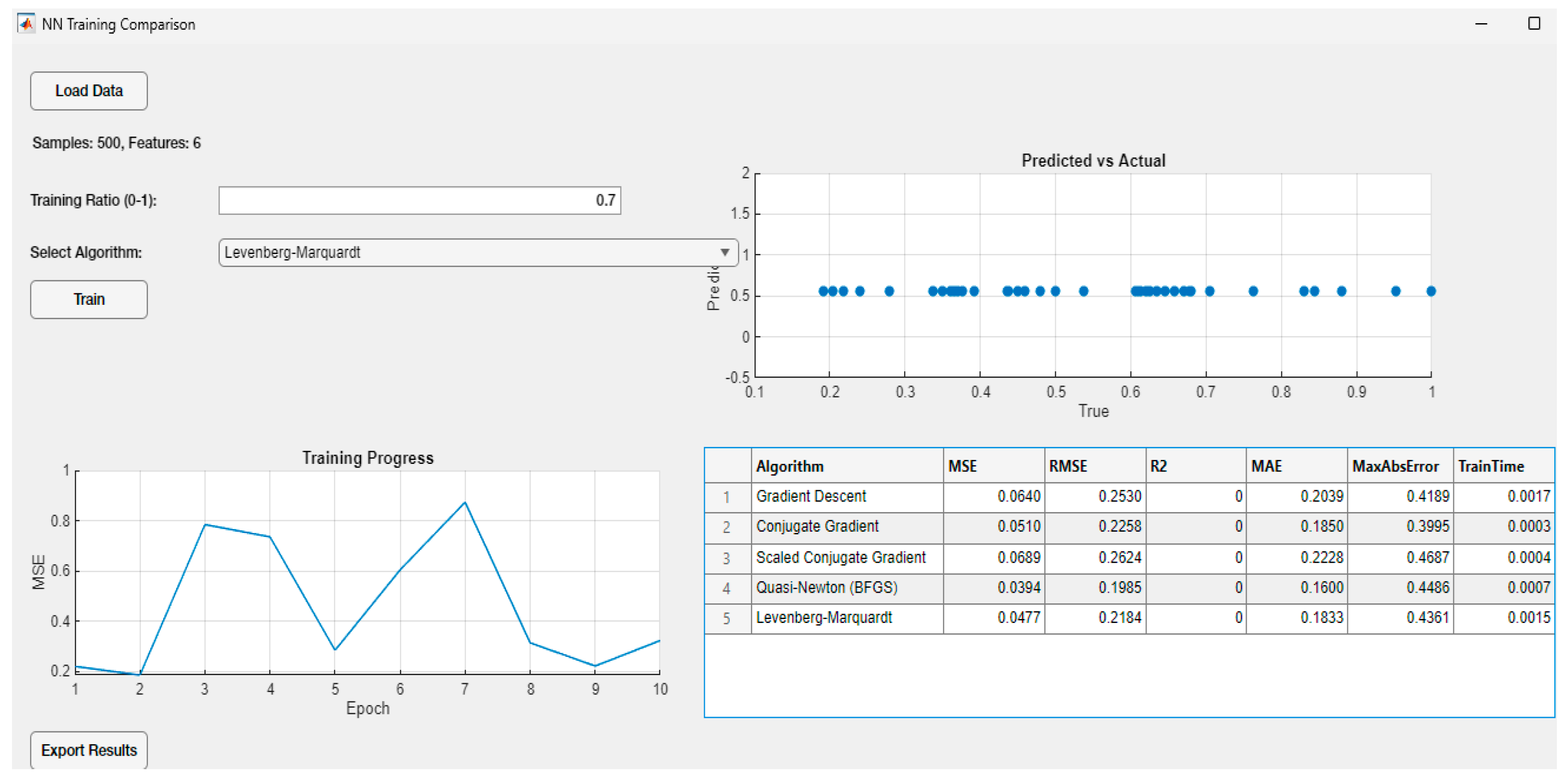

In this study, a multilayer feed-forward artificial neural network (ANN) with a single hidden layer was employed across all data sets, trained by different kinds of backpropagation algorithms as Gradient Descent Algorithm, Conjugate Gradient Algorithm, Scaled Conjugate Gradient Algorithm, Quasi-Newton Algorithm, Levenberg-Marquardt Algorithm. In the final stage of the design a predictive modeling system, which serves to predict various sets of input data into their respective classes, as showed in

Figure 12 and

Figure 13, respectively.

The systematic analysis and reproduction of our methodological flowchart using appropriate formatting and technical specifications.

Implementation Specifications:

1. Initial Data Management Protocol

%%%

Data = ExperimentalDB(n=500)

TrainingSet = Data [0:350] # 70%

ValidationSet = Data[350:500] # 30%

%%%

2. Architectural Definition Parameters

%%%

S: Network architecture parameter

N: Maximum iteration limit

i: Current iteration index

α: Error threshold criterion

%%%

3. Iterative Learning Algorithm

%%%

while True:

error = train_network(S, i)

if error <α:

break

if i > N:

S = S + 1

i = 1

else:

i = i + 1

%%%

4. Statistical Validation Metrics

%%%

MAE = mean(|predicted - measured|)

MSE = mean((predicted - measured)²)

MAPE = mean(|predicted - measured|/measured × 100)

R² = 1 - SSres/SStot

%%%

This methodological framework ensures systematic optimization of the ANN architecture while maintaining rigorous validation protocols through statistical assessment metrics. The iterative process continues until either convergence criteria are met (error < α) or maximum architectural complexity is reached.

7. Backpropagation Algorithms and Experimental Setup

Backpropagation was developed as a sophisticated enhancement of the Widrow-Hoff learning rule, specifically designed for multi-layer networks and nonlinear differentiable transfer functions. This method has become a cornerstone in training neural networks, allowing them to learn complex patterns and relationships within data. By repeatedly presenting the network with input vectors alongside their corresponding target outputs, backpropagation adjusts the network’s internal weights, guiding it to approximate intricate functions with increasing accuracy. This iterative process not only helps the network to associate specific input vectors with their correct outputs but also enables it to classify and generalize new inputs in ways that are meaningful and precise, as defined by the parameters you set.

The beauty of backpropagation lies in its ability to refine the network's understanding layer by layer, gradually reducing the error between the predicted and actual outputs. Through this method, the network learns to navigate the complexities of nonlinear relationships, adapting its internal structure to reflect the underlying patterns of the data. This powerful technique has proven indispensable in a wide range of applications, from function approximation to classification tasks, making it a fundamental tool in the advancement of neural network research [

22].

Gradient Descent Algorithm, Conjugate Gradient Algorithm, Scaled Conjugate Gradient Algorithm, Quasi-Newton Algorithms and Levenbergo-Marquardt Algorithm [

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28]. For each algorithm, we performed 30 independent runs. The choice of 30 runs in the neural network training process is based on statistical principles and practical considerations in machine learning. Here's why 30 runs are often used:

- ✓

Statistical significance: In statistics, 30 often considered the minimum sample size for the Central Limit Theorem to apply. This theorem states that the distribution of sample means approximates a normal distribution as the sample size becomes large, regardless of the population's distribution.

- ✓

Reducing randomness: Neural network training involves random initialization of weights and often random sampling of data. Multiple runs help to average out the effects of this randomness, providing a more reliable estimate of the model's performance.

- ✓

Assessing variability: With 30 runs, you can get a good sense of the variability in model performance. This helps in understanding how stable the results are across different initializations and data splits.

- ✓

Balancing computation time and reliability: While more runs (e.g., 100 or 1000) would provide even more reliable results, 30 runs strike a balance between computational efficiency and statistical robustness.

- ✓

Common practice: In machine learning and neural network research, 30 runs have become a common practice, making results more comparable across different studies.

However, the number of runs can be adjusted based on specific needs, computational resources, or the complexity of the problem. In some cases, fewer runs might be sufficient, while in others, more runs might be necessary for higher confidence in the results. In each run, the problem data was split into a training and testing set, where the former contains 70% of the data samples and the latter 30%. The datasets were randomly partitioned before each run, and while training performance will be reported the critical result will be the prediction accuracy of the evolved models over the test data. In particular, the algorithms were compared using the Mean Squared Error (MSE) and the coefficient of determination (R

2), computed over the ground truth output and the estimated output of each algorithm, for the training and testing data.

Table 3 summarizes all parameters for five backpropagation algorithms. We will also report an analysis of the size of the solutions generated by the algorithms that achieved the best performance, as an approximation of model complexity.

Table 3,

Table 4,

Table 5 and

Table 6, highlighted parameters for Gradient Desent Algorithm, Conjugate Gradient Algorithm, Scaled Conjugate Gradient Algorithm, Quasi-Newton Algorithms and Levenberg-Marquardt Algorithm, respectively.

7.1. Parameters of Gradient Descent Algorithm:

Gradient Descent is an optimization algorithm used to minimize a cost function by iteratively moving in the direction of steepest descent. Here are the key parameters of the Gradient Descent Algorithm:

Table 3.

Parameters for Gradient Descent Algorithm.

Table 3.

Parameters for Gradient Descent Algorithm.

| Parameter |

Value |

Description |

| Learning rate (lr) |

0.01 |

This is the step size at each iteration while moving toward a minimum of the loss function. |

| Maximum number of epochs |

1000 |

An epoch is a complete pass through the entire training dataset |

| Performance goal |

0 |

Training stops if the performance function falls below this value |

| Maximum validation failures |

6 |

Training stops if the validation performance has increased more than max_fail times since the last time it decreased. |

| Minimum performance gradient |

1e-5 |

Training stops if the magnitude of the gradient is less than this value. |

| Initial mu |

0.001 |

Initial value for mu. mu is used for regulating the indefiniteness of the Hessian. |

| mu decrease factor |

0.1 |

Factor by which mu is decreased |

| mu increase factor |

10 |

Factor by which mu is increased |

| Maximum mu |

1.0e10 |

Maximum value for mu |

7.2. Parameters of Conjugate Gradient Algorithm

The Conjugate Gradient algorithm is an optimization technique used primarily for solving large-scale linear systems and unconstrained optimization problems, an overview of its objective and advantages are shown in

Table 4.

Table 4.

Parameters of Conjugate Gradient Algorithm.

Table 4.

Parameters of Conjugate Gradient Algorithm.

| Parameter |

Value |

Description |

| Maximum number of epochs |

1000 |

This parameter sets the maximum number of times the learning algorithm will work through the entire training dataset. |

| Performance goal |

0 |

It serves as a stopping criterion for the training algorithm. |

| Maximum validation failures |

6 |

It serves as an early stopping mechanism to prevent overfitting. |

| Minimum performance gradient |

1e-6 |

It serves as a stopping criterion to determine when the training has converged or is making insignificant progress |

| Initial sigma |

5.0e-5 |

Determines change in weight for second derivative approximation. |

| Sigma decrease factor |

0.5 |

It helps in adjusting the step size for calculating the second derivative approximation during training. |

| Sigma increase factor |

1.5 |

It helps in adjusting the step size for calculating the second derivative approximation during training, allowing for larger steps when appropriate. |

| Maximum sigma |

1.0e10 |

It prevents sigma from growing excessively large during training, which could lead to numerical instability or inefficient computations. |

| Minimum sigma |

1.0e-15 |

It prevents sigma from becoming too small during training, which could lead to numerical instability or ineffective computations. |

| Alpha |

0.001 |

Scale factor for sigma |

| Beta |

0.1 |

Scale factor for backtracking |

| Delta |

0.01 |

Minimum change in lambda for line search |

| Lambda |

1.0e-7 |

Parameter for regulating the indefiniteness of the Hessian |

7.3. Parameters of Scaled Conjugate Gradient Algorithm

The Scaled Conjugate Gradient (SCG) algorithm is an advanced variation of the Conjugate Gradient method, specifically designed for training neural networks (

Table 5).

Table 5.

Parameters of Scaled Conjugate Gradient algorithm.

Table 5.

Parameters of Scaled Conjugate Gradient algorithm.

| Parameter |

Value |

Description |

| Maximum number of epochs |

1000 |

Limits the number of training iterations to prevent excessive training time. |

| Performance goal |

0 |

Sets a target performance level. Training stops if this goal was reached. |

| Maximum training time |

Inf |

Sets a time limit for training. 'Inf' means no time limit. |

| Minimum performance gradient |

1.0e-6 |

Training stops if the performance gradient falls below this value, indicating minimal improvement |

| Maximum validation failures |

6 |

Stops training if the validation performance fails to improve for this many consecutive epochs. |

| Sigma |

5.0e-5 |

Determines the change in weight for the second derivative approximation. |

| Lambda |

5.0e-7 |

Regulates the indefiniteness of the Hessian, affecting the scale of the step size. |

| Show |

25 |

Controls how often (in epochs) the training progress was displayed. |

| Show Command Line |

false |

Determines whether to display progress in the command window. |

| Show Window |

true |

Controls whether to display the training progress window |

7.4. Parameters of Quasi-Newton Algorithm

The primary objective of Quasi-Newton algorithms is to solve unconstrained nonlinear optimization problems efficiently by approximating the Hessian matrix (or its inverse) of the objective function, rather than computing it directly (

Table 5).

Table 5.

Parameters of Quasi-Newton Algorithm.

Table 5.

Parameters of Quasi-Newton Algorithm.

| Parameter |

Value |

Description |

| Maximum number of epochs |

1000 |

Sets the maximum number of training iterations to prevent excessive training time. |

| Performance goal: 0 |

0 |

Specifies the target performance level. Training stops if this goal was reached. |

| Maximum training time |

Inf |

Sets a time limit for training. 'Inf' means no time limit. |

| Minimum performance gradient |

1.0e-5 |

Training stops if the performance gradient falls below this value, indicating minimal improvement. |

| Maximum validation failures |

6 |

Stops training if the validation performance fails to improve for this many consecutive epochs. |

| Minimum Lambda |

1.0e-7 |

Sets the lower bound for Lambda, which affects the size of the weight update. |

| Maximum Lambda |

1.0e10 |

Sets the upper bound for Lambda. |

| Initial Lambda |

0.001 |

Sets the starting value for Lambda. |

| Lambda increase factor |

10 |

Determines how much Lambda increases when a step would increase the performance. |

| Lambda decrease factor |

0.1 |

Determines how much Lambda decreases after a successful step. |

| Show |

25 |

Controls how often (in epochs) the training progress was displayed. |

| Show Command Line |

false |

Determines whether to display progress in the command window. |

| Show Window |

true |

Controls whether to display the training progress window. |

7.5. Parameters of Levenberg-Marquardt Algorithm

The primary objective of the Levenberg-Marquardt (LM) algorithm is to solve non-linear least squares problems, particularly in the context of curve fitting and non-linear optimization (

Table 6). It was specifically designed to find the minimum of a function that is expressed as the sum of squares of nonlinear functions.

Table 6.

Parameters of Levenberg-Marquardt Algorithm.

Table 6.

Parameters of Levenberg-Marquardt Algorithm.

| Parameter |

Value |

Description |

| Maximum number of epochs |

1000 |

Limits the number of training iterations to prevent excessive training time. |

| Performance goal |

0 |

Sets a target performance level. Training stops if this goal was reached. |

| Maximum training time |

Inf |

Sets a time limit for training. 'Inf' means no time limit. |

| Minimum performance gradient |

1.0e-7 |

Training stops if the performance gradient falls below this value, indicating minimal improvement. |

| Maximum validation failures |

6 |

Stops training if the validation performance fails to improve for this many consecutive epochs. |

| Initial mu |

0.001 |

Sets the initial value of mu, which determines the step size and direction. |

| mu decrease factor |

0.1 |

Factor by which mu was decreased after a successful step. |

| mu increase factor |

10 |

Factor by which mu was increased after an unsuccessful step. |

| Maximum mu |

1e10 |

Sets the upper limit for mu to prevent it from becoming too large. |

| Minimum gradient |

1e-6 |

Minimum norm of gradient for which the algorithm continues training. |

| Show |

25 |

Controls how often (in epochs) the training progress was displayed. |

| Show Command Line |

false |

Determines whether to display progress in the command window. |

| Show Window |

true |

Controls whether to display the training progress window. |

| Maximum mu |

1.0e10 |

Sets the upper limit for mu to prevent it from becoming too large. |

7.6. Performance of the ANN Model

However, the performance of the ANN model was statistically measured by the mean square error (MSE) and regression coefficient, which were calculated with the experimental values and network predictions. These calculations were used as a criterion for model adequacy, obtained as follows:

Different assessment measures were used to assess the accuracy of the proposed machine learning algorithms. These measures include Mean Square Error (MSE), Mean Absolute Error (MAE), Mean Absolute Percentage Error (MAPE), and Coefficient of Determination (R2).

(a) Mean Absolute Error: It measures the mean absolute difference between the values that a model predicts and the values that are actually in a dataset. It is given by the following formula:

where the yi is the actual value of the experimental oxygen demand at point , n represents the number of data points, and ŷi is predicted value of chemical oxygen demand at point.

(b) Mean Square Error: It calculates the square of the average squared variances between the actual and anticipated values in a dataset. Mathematically, MSE is calculated as:

(c) Mean Absolute Percentage Error: It calculates the mean absolute percentage difference between a dataset’s actual values and its predicted values. Mathematically, MAPE is calculated as:

(d) Correlation coefficient: It demonstrates the percentage of a neural network model’s dependent variable’s variance that can be predicted based on the independent variables, quantifying the goodness of fit of the model to the actual data. It is given by the following formula:

(e) The Pearson correlation coefficient, often denoted as r, is a measure of the linear correlation between two variables X and Y. It ranges from -1 to +1, where:

- ✓

A value of +1 indicates a perfect positive linear correlation

- ✓

A value of 0 indicates no linear correlation

- ✓

A value of -1 indicates a perfect negative linear correlation

The formula for the Pearson correlation coefficient is:

where:

- ✓

r is the Pearson correlation coefficient

- ✓

x and y are individual sample points

- ✓

x̄ (x-bar) is the mean of the x values

- ✓

ȳ (y-bar) is the mean of the y values

- ✓

Σ represents the sum

Alternatively, it can also be expressed as:

where:

- ✓

is the covariance of and .

- ✓

is the standard deviation of

- ✓

is the standard deviation of

-

The Pearson correlation coefficient measures the strength and direction of the linear relationship between two continuous variables (

Figure 14). Some pairs of variables show potential linear relationships. For example:

The herbicide concentration seems to correlate with COD_mgL, suggesting higher herbicide concentrations might be associated with higher chemical oxygen demand.

Other variables like reaction time and TiO2 concentration also warrant further investigation.

8. Model Discussion

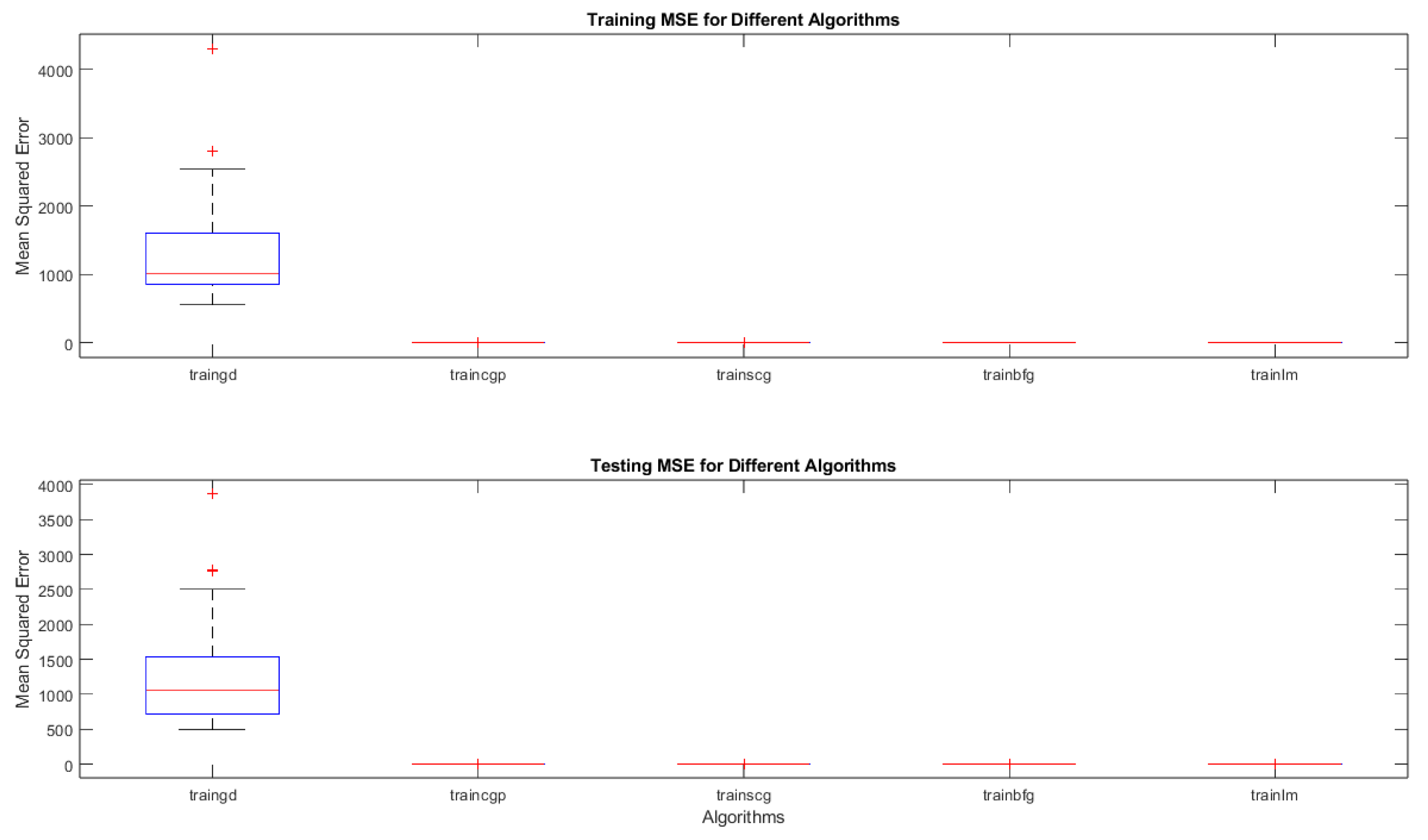

Boxplots that show the MSE performance of each algorithm on the training (

Figure 15 a) and testing (

Figure 15 b) data over all thirty runs. Numerical values represent the median.

9. Training Progress Plot

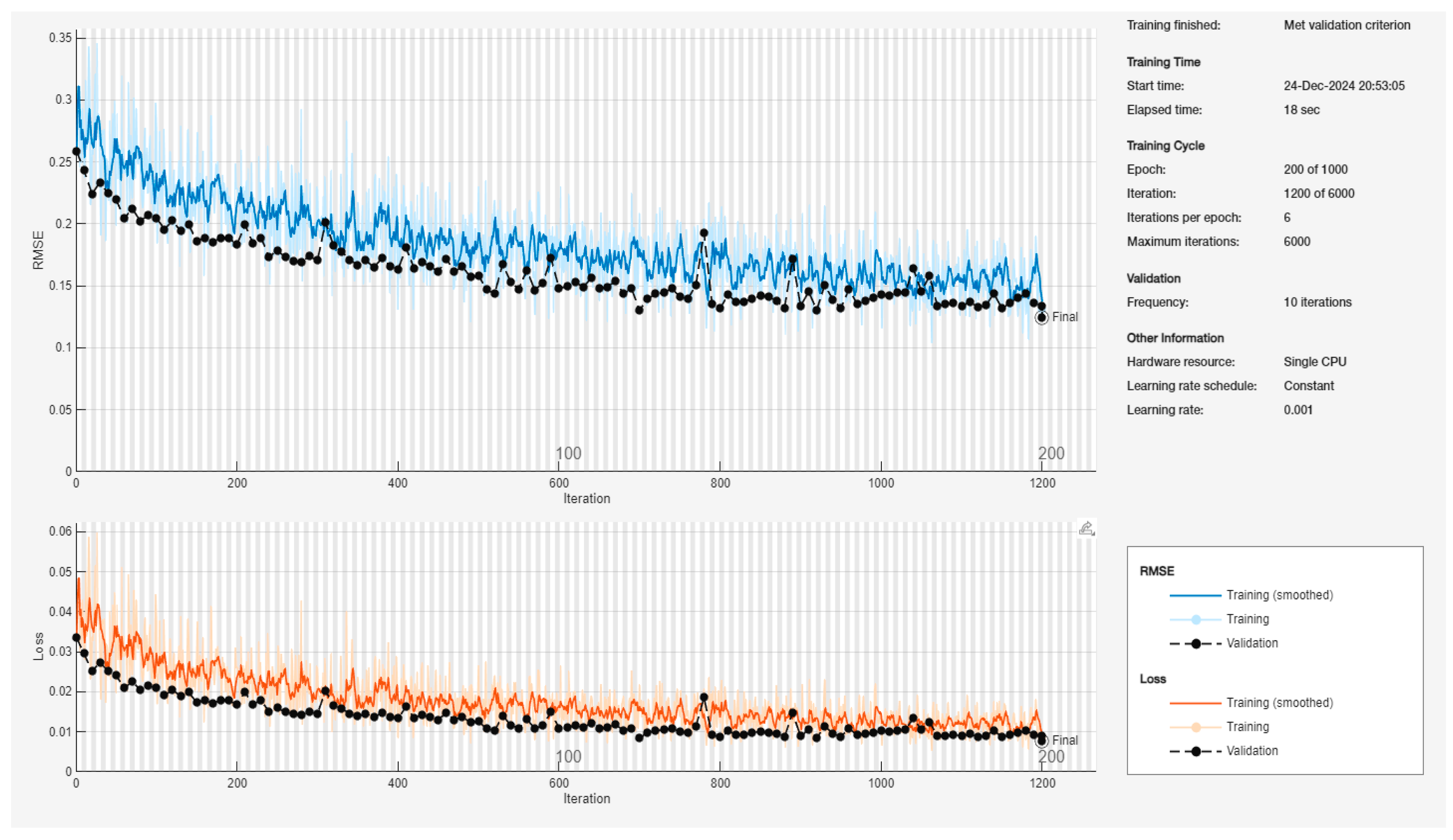

The

Figure 15 presents a comprehensive visualization of the neural network's training progression over 1200 iterations, comprising two primary performance metrics: Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) and Loss, plotted against the iteration count.

- ✓

Total Epochs: 200 of 1000 planned

- ✓

Iterations per epoch: 6

- ✓

Maximum iterations: 6000

- ✓

Learning rate: 0.001 (constant schedule)

- ✓

Hardware utilization: Single CPU

- ✓

Validation frequency: Every 10 iterations

- ✓

Final validation RMSE: 0.12451

- ✓

Initial RMSE values commence at approximately 0.35

- ✓

Exhibits rapid convergence in the first 200 iterations

- ✓

Training curve (blue) demonstrates characteristic oscillatory behavior

- ✓

Validation curve (black dotted) shows more stable progression

- ✓

Final convergence achieved at approximately 0.13-0.14 RMSE

- ✓

Notable stabilization observed after iteration 800

- ✓

Initial loss values begin at approximately 0.05

- ✓

Training loss (orange) displays higher variance compared to validation loss

- ✓

Validation loss (black dotted) demonstrates consistent downward trajectory

- ✓

Final loss values stabilize around 0.01

- ✓

Minimal gap between training and validation loss suggests good generalization

- ✓

The training process successfully met the validation criterion

- ✓

Total elapsed time: 18 seconds

- ✓

Smooth convergence pattern without significant overfitting

- ✓

Training and validation curves maintain parallel trajectories, indicating robust learning

This figure effectively demonstrates the neural network's learning stability and predictive capability for COD estimation. The relatively low final RMSE (0.0140) suggests strong predictive performance for herbicide-contaminated wastewater analysis.

Meanwhile, the

Figure 16 summarizes the mean squared error (MSE) performance of five neural-network training algorithms—traingd (gradient descent), traincgp (conjugate gradient Polak-Ribiere), trainscg (scaled conjugate gradient), trainbfg (BFGS quasi-Newton), and trainlm (Levenberg–Marquardt)—across 30 independent runs. The top panel (

Figure 16a) shows the training MSE distributions, while the bottom panel (

Figure 16b) shows the testing MSE distributions for the same algorithms.

- 1.

-

Boxplots and Medians

Each box corresponds to one of the five algorithms. The central line in each box is the median MSE across the 30 runs, and the top and bottom edges of the box represent the 25th and 75th percentiles, respectively. The whiskers extend to data points within 1.5 times the interquartile range from the box boundaries, and any points beyond these whisker limits (marked with “+”) are statistical outliers.

-

2.

-

Overall Comparison

- ○

Gradient Descent (traingd) exhibits noticeably higher MSE values (both in training and testing) compared to the other four algorithms. This is reflected by the larger box and several outliers.

- ○

Conjugate Gradient (traincgp, trainscg), BFGS (trainbfg), and Levenberg–Marquardt (trainlm) all show substantially lower MSE values, with their boxplots grouped near the lower portion of each panel. Their medians are also close to one another, indicating relatively comparable performance.

- ○

Among these advanced algorithms, trainlm tends to have the most consistently low MSE, often yielding the best median and least variability.

-

3.

-

Insights and Practical Implications

- ○

Training Data (

Figure 16a): The distribution for traingd is both higher and broader, implying that plain gradient descent is not converging as effectively (or stably) as the advanced methods. In contrast, trainlm, traincgp, trainscg, and trainbfg converge to solutions with much lower and more consistent training errors.

- ○

Testing Data (

Figure 16b): A similar pattern emerges on the test set, suggesting that the benefit of the advanced algorithms generalizes well. trainlm in particular shows minimal spread, hinting at both strong fitting ability and good generalization (less overfitting).

- ○

Statistical Robustness: The low variability among trainlm and conjugate-gradient-based methods indicates these algorithms are more robust to random initializations and data variations, which is crucial for reliable chemical oxygen demand (COD) prediction in herbicide-contaminated wastewater.

- 4.

-

Relevance to COD Prediction

For highly accurate chemical oxygen demand prediction—where measured outcomes can vary significantly due to complex chemical dynamics—trainlm and the conjugate-gradient methods appear superior. Achieving low MSE in both training and testing highlights their potential for yielding stable, reliable models in environmental engineering contexts.

Whereas,

Table 7, illustrates a summary of MSE by each algorithm on the training and testing sets, showing the median, first and third quartiles.

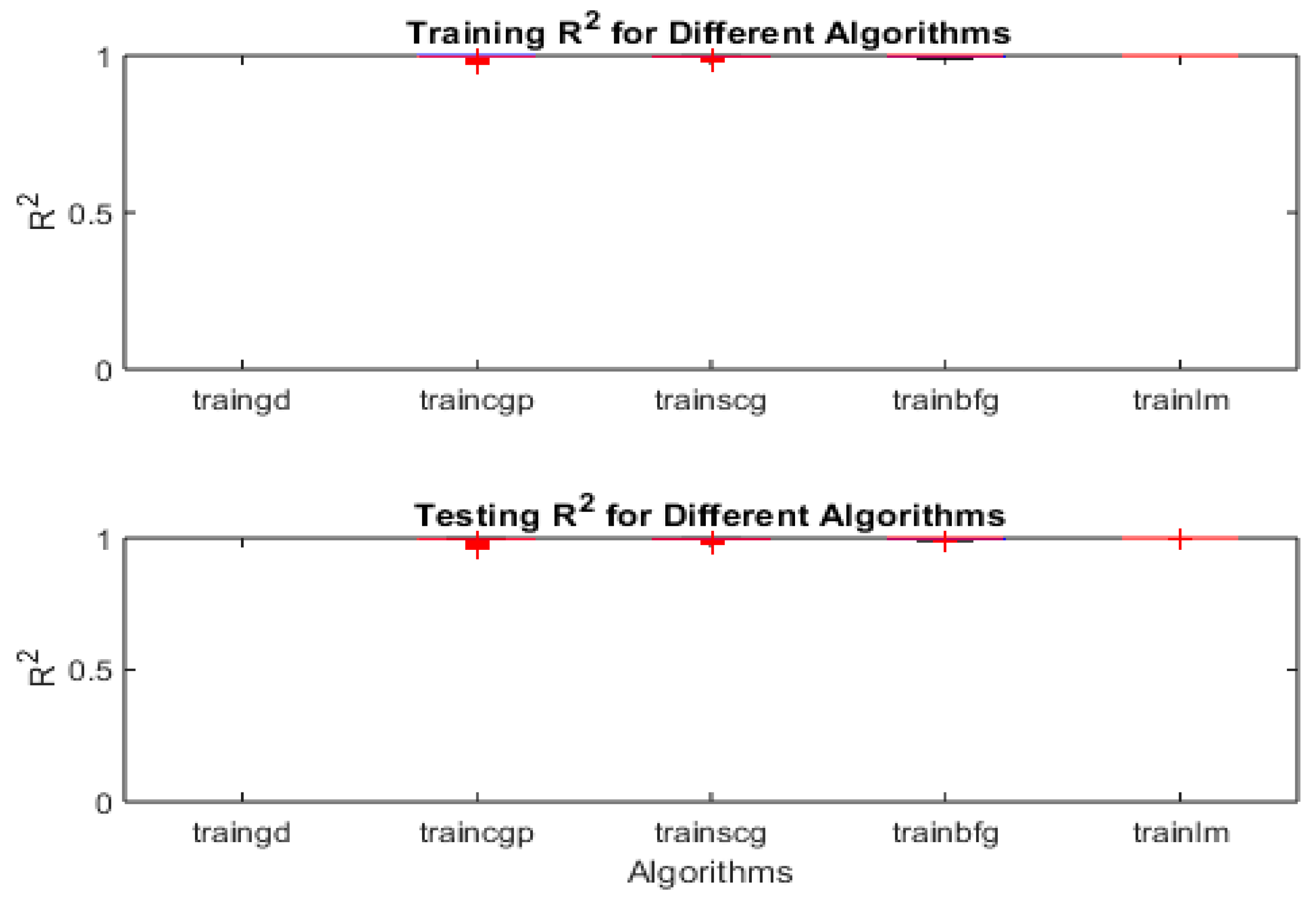

On the other hand, the Figure 17 presents boxplots illustrating the coefficient of determination (R2) values achieved by the five neural-network training algorithms on (a) training data (top panel) and (b) testing data (bottom panel) over 30 separate runs. The algorithms include:

traingd (gradient descent)

traincgp (conjugate gradient Polak–Ribiere)

trainscg (scaled conjugate gradient)

trainbfg (BFGS quasi-Newton)

trainlm (Levenberg–Marquardt)

-

1.

-

Boxplot Features

- ○

Each box represents the distribution of R2 values for the respective algorithm.

- ○

The horizontal line inside each box indicates the median R2

- ○

The box edges mark the 25th and 75th percentiles, and the whiskers extend to data points within 1.5 times the interquartile range.

- ○

Any red “+” symbols beyond the whiskers denote outliers.

-

2.

-

Overall Performance Trends

- ○

Near-Perfect R2: In both panels, most of the advanced algorithms (traincgp, trainscg, trainbfg, and trainlm) achieve R2 values close to 1 for both training and testing. Their median lines are typically near or at 1, indicating a very strong correlation between predicted and actual values.

- ○

Gradient Descent (traingd): Compared to the other methods, plain gradient descent shows somewhat lower R2 values and potentially greater variability (broader whiskers or more outliers). This suggests it struggles to learn as effectively or consistently as the more sophisticated algorithms.

-

3.

-

Detailed Observations

- ○

-

Training Data (Figure 17a):

- ▪

trainlm, trainbfg, traincgp, and trainscg cluster around R2≈1 with minimal spread, implying they effectively fit the training set.

- ▪

traingd typically yields a lower median R2, indicating a less optimal fit on average.

- ○

-

Testing Data (Figure 17b):

- ▪

The patterns largely mirror the training results, indicating the models’ strong performance generalizes well.

- ▪

trainlm, trainbfg, traincgp, and trainscg retain R2 values close to 1, while traingd lags behind, showing a broader distribution and lower medians.

-

4.

-

Practical Significance for COD Prediction

Achieving R2 near 1 is crucial for accurate chemical oxygen demand (COD) prediction in herbicide-contaminated wastewater, where complex interactions often lead to wide-ranging target values. The high R2 values indicate these advanced training algorithms can capture the underlying relationships with both accuracy and consistency, outperforming standard gradient descent in terms of predictive power.

-

5.

-

Implications for Model Selection

- ○

Robustness: With their tight boxplots and few outliers, trainlm, trainbfg, traincgp, and trainscg are shown to be robust against randomness in initial weights and data shuffling.

- ○

Generalization: The close alignment between training and testing R2 distributions points to good generalization—a desirable trait for real-world applications where data can be variable.

- ○

Recommendation: For practitioners aiming to deploy neural networks for COD predictions, focusing on algorithms like Levenberg–Marquardt (trainlm) or conjugate gradient approaches (traincgp, trainscg, trainbfg) may yield higher and more consistent R2 values than basic gradient descent.

Although,

Table 8 shows Summary of R

2 by each algorithm on the training and testing sets, showing the median, first and third quartiles.

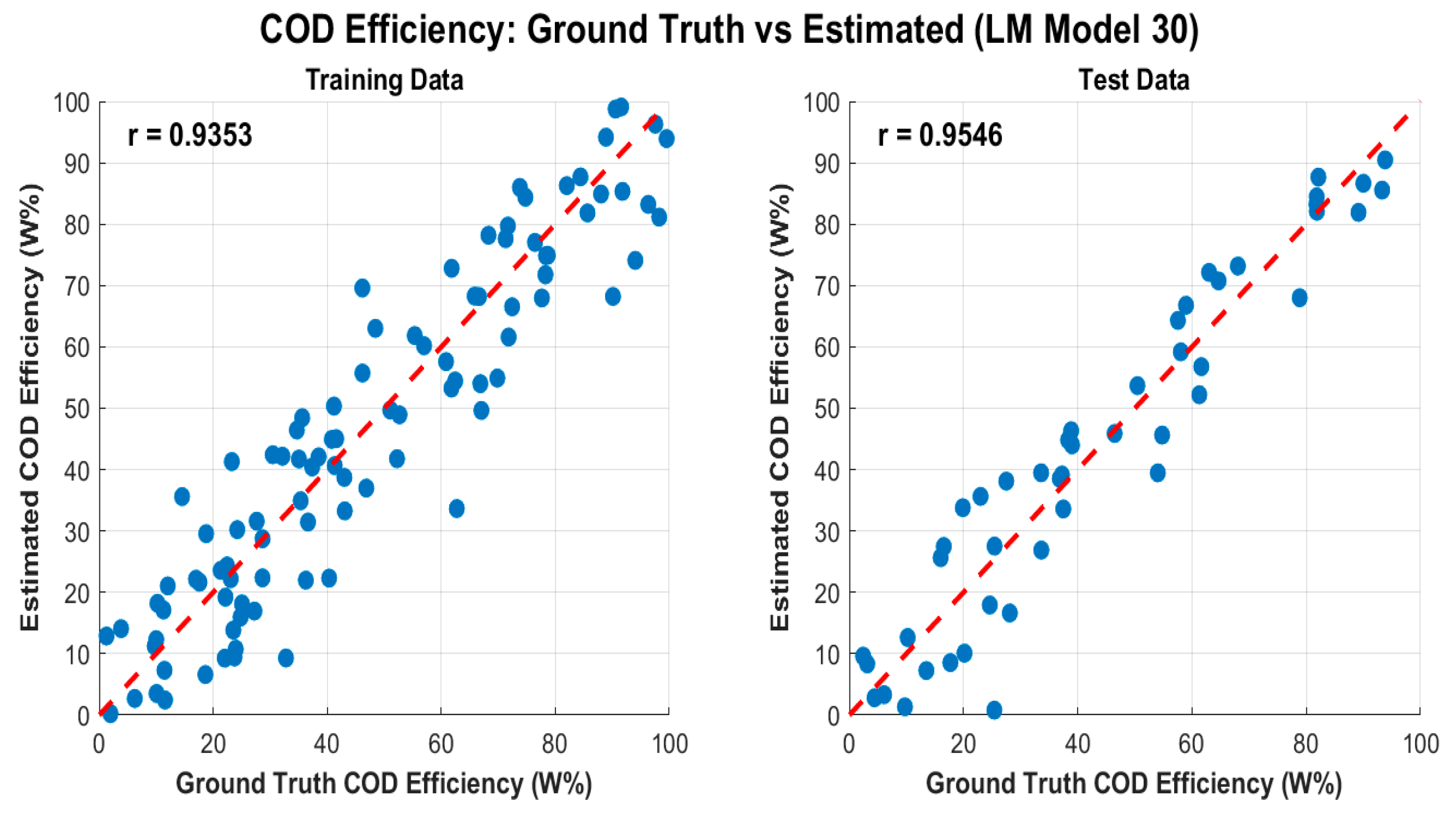

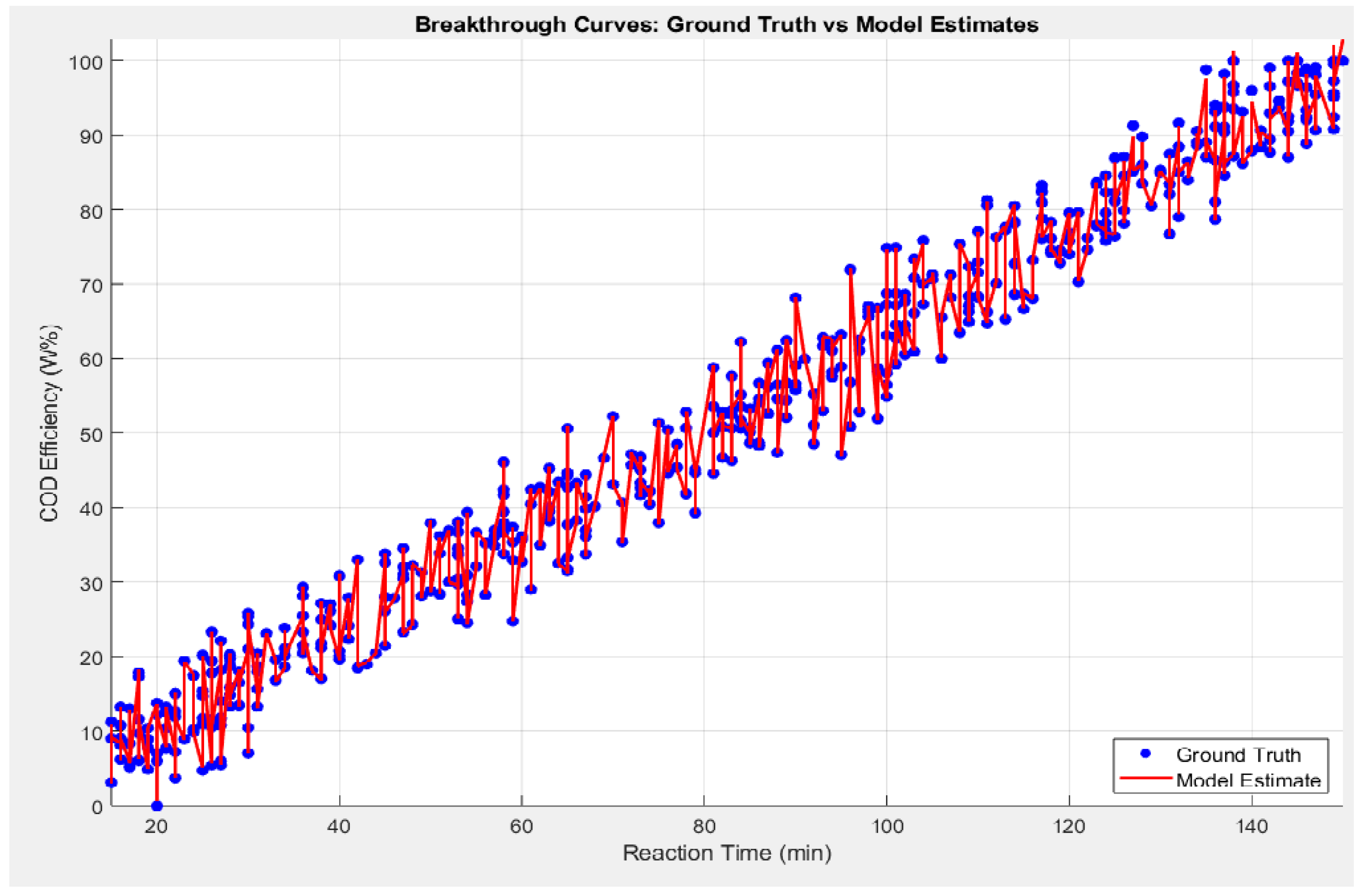

Whilst, the COD efficiency: Ground truth vs estimated by Levenberg-Marquardt Model, as shown in

Figure 18.

- ✓

Intercept: 49.8160

- ✓

Reaction_Time_min: -0.3326

- ✓

pH: 1.9594

- ✓

TiO2_Concentration_mgL: -0.0988

- ✓

UV_Light_W: 0.5074

- ✓

Ultrasound_kHz: -0.4882

- ✓

Herbicide_Concentration_M: 98288.1273

- ✓

R-squared: 0.9998

A multiple regression model was applied to the COD database obtained from sonophotocatalysis, taking into account the initial COD concentration and operational conditions such as reaction time (t), pH, titanium dioxide [TiO

2]

o, UV_Light_W, Ultrasound_kHz and herbicide concentration (C

0). As one knows, the regression analysis could be used to establish the relationship among variables. A general regression analysis equation that includes nine independent variables is illustrated in Eq. (12).

where

is the dependent variable represented by the COD. However,

and

have been pointed out as the intercepts

and coefficients of the regression, respectively,

); where

Figure 18 presents scatter plots of observed (ground-truth) COD efficiency versus the values predicted by the Levenberg–Marquardt (LM) neural network model for both (a) training and (b) testing datasets. The red dashed line in each plot represents the ideal 1:1 relationship (i.e., if the prediction perfectly matched the true COD efficiency, all points would lie on this line). The figure also provides the Pearson correlation coefficient (r) for each dataset: r=0.9353r = 0.9353 for training and r=0.9546r = 0.9546 for testing.

High correlation (r > 0.93): Both training and test sets exhibit strong linear relationships between estimated and observed COD efficiency, illustrating that the LM-based model has learned and generalized the underlying chemical and operational relationships effectively.

Minimal scatter: Visually, most points fall close to the 1:1 line, indicating a low prediction error. This tight clustering implies that the model not only performs well in fitting the training data but also generalizes effectively to unseen data (testing set).

Comparable correlation values: The similarity between training (r=0.9353r=0.9353) and testing (r=0.9546r=0.9546) correlation coefficients suggests that overfitting is minimal. A model suffering from overfitting would typically show very high performance on training data but a pronounced drop on test data. Here, the LM approach appears robust, successfully balancing fit quality and generalization.

Slightly higher rr for testing: It is not uncommon to see a marginally higher rr on the test dataset—particularly if the test set is relatively smaller or if certain influential outliers are present in the training data. This outcome further supports the model’s reliability.

Negative vs. Positive Coefficients: A negative coefficient (e.g., Reaction_Time_min, TiO2_2_Concentration, Ultrasound_kHz) indicates that increasing that variable reduces the predicted COD efficiency under the specific experimental or operational conditions. Conversely, positive coefficients (pH, UV_Light_W) suggest that increasing those parameters enhances COD removal efficiency.

Magnitude of Coefficients: Larger absolute values for Herbicide_Concentration_M) may indicate a stronger sensitivity of the COD efficiency to changes in that variable, although it is crucial to consider the scale or units of each predictor when interpreting these coefficients.

Near-Perfect R2 (0.9998): Although R2 near 1.0 indicates an extremely tight fit, one should also confirm that this is not influenced by any small data range or a disproportionately large effect of certain variables. Nevertheless, it underscores the very strong predictive capability of your model in capturing the relationships among the chosen parameters.

COD Efficiency Insights: These results confirm that your chosen operational parameters—reaction time, pH, titanium dioxide concentration, UV light power, ultrasound frequency, and herbicide concentration—can reliably predict COD removal performance.

Process Optimization: High predictive accuracy implies that you can use the model to explore ‘what-if’ scenarios (e.g., adjusting reaction times, TiO2_2 load, or pH) to maximize COD removal while minimizing resource consumption.

Environmental Engineering Applications: In industrial or environmental settings, such predictive strength is particularly valuable for designing more cost-effective and efficient wastewater treatment processes.

Overall, Figure 18 affirms that the Levenberg–Marquardt neural network model offers highly accurate COD efficiency predictions, both in training and real-world testing scenarios. The strong correlations, minimal scatter around the 1:1 line, and supportive regression analysis underscore the model’s potential as a valuable tool for practical wastewater treatment design and optimization in herbicide-contaminated environments.

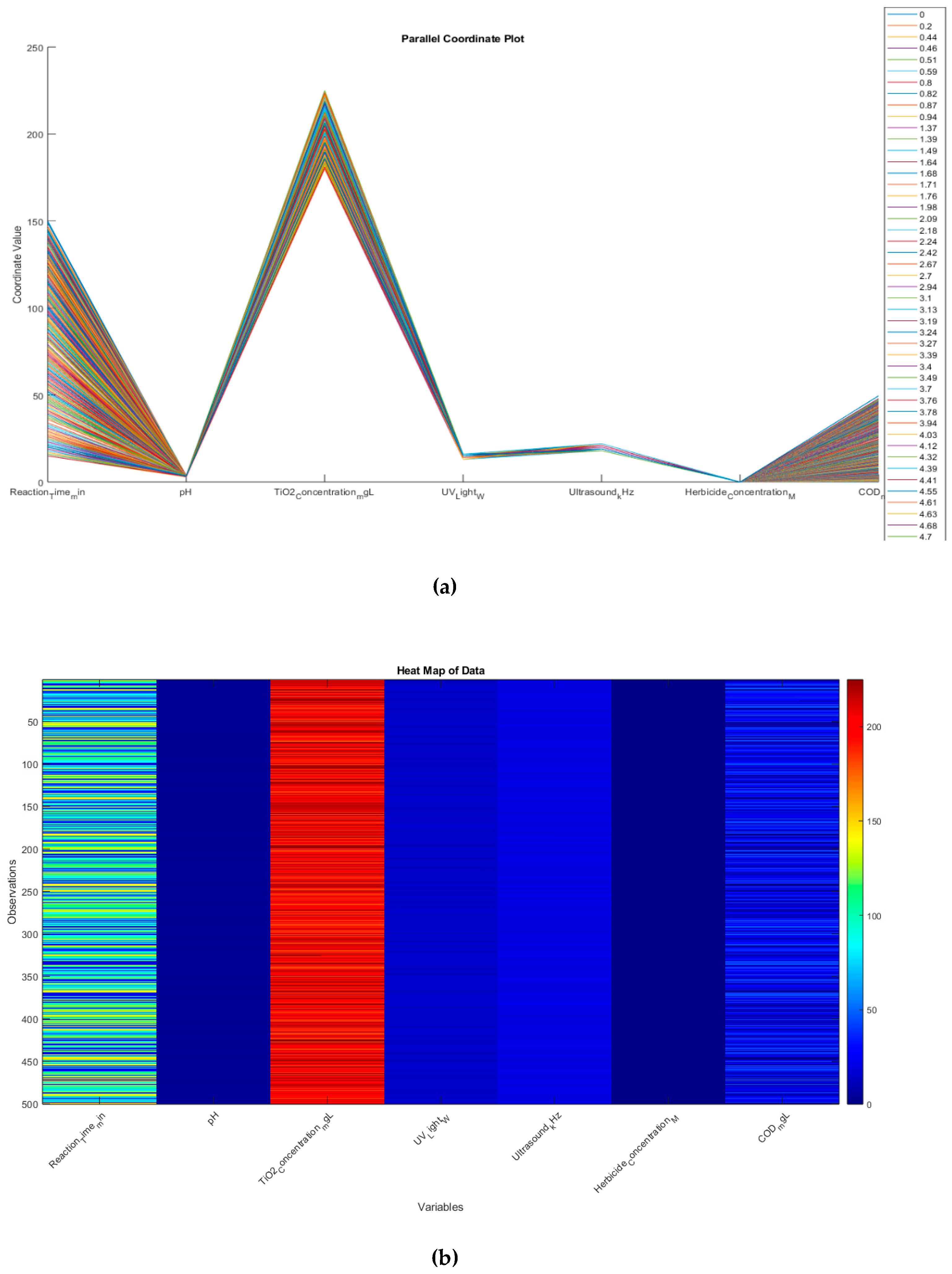

While,

Figure 19 combines two powerful, high-dimensional visualization methods—a parallel coordinate plot and a heat map—to explore chemical oxygen demand (COD) alongside various operational and chemical parameters. These approaches provide complementary perspectives on the same dataset, allowing for a more comprehensive understanding of inter-variable relationships and data patterns. On the other hand, in order to analyze high-dimension data. A parallel coordinate plot is a useful visualization techniques. The parallel coordinate plot underlines the multidimensional nature of chemical oxygen demand respect to attributes variables as reaction times, pH, TiO

2, UV_Light, Ultrasound_Khz and herbicide concentration. It is high level visualization plot offering graphical relationship between, more than 3 dimensions, otherwise would not be posible through any other graphing method. Consequently, it helps us to trace out values of the tuning parameters for the optimal fitness function as illustrated in

Figure 19.

- 1.

-

Multidimensional Nature

The parallel coordinate plot underscores the multidimensional nature of the dataset. Each line (or “trace”) represents one observation (or experimental run), and it traverses parallel axes corresponding to reaction time, pH, TiO2_22 concentration, UV light intensity, ultrasound frequency, herbicide concentration, and COD measurements. By visually following a single line across all axes, one can see how each experimental run’s values compare across all parameters.

- 2.

-

Visual Clustering and Outliers

- ○

Pattern Identification: Lines that run similarly across all axes suggest that those observations share similar parameter settings and COD outcomes.

- ○

Outlier Detection: A trace that deviates sharply at any axis may indicate unusual or extreme values for a given variable (e.g., significantly higher pH or particularly long reaction time). These potential outliers can be key to further investigation—perhaps they correspond to unexpectedly high or low COD removal.

- 3.

-

Complex Relationships

Unlike traditional 2D or 3D plots, parallel coordinates allow more than three dimensions to be visualized simultaneously. This is especially crucial in environmental engineering and wastewater treatment contexts, where multiple interacting variables (e.g., chemical concentrations, reaction times) can jointly influence COD removal efficiency.

- 4.

-

Parameter Tuning

By analyzing how lines cluster or separate on each axis, one can gain insights into optimal ranges for each parameter. For example, if lines yielding high COD removal show characteristic ranges for pH, TiO2_22 concentration, or herbicide concentration, this can guide tuning decisions for maximizing COD removal.

This heat map visualizes the entire dataset, with each row representing an observation and each column representing a variable. The color of each cell represents the value of that variable for that observation. Where, each column represents a different variable, and each row represents a single observation, the color intensity indicates the relative value of each data point, warmer colors (red) represent higher values, while cooler colors (blue) represent lower values. However, this visualization allows you to see patterns and trends across all variables and observations simultaneously, looking for any visible patterns or clusters in the data, which might indicate relationships between variables or groups of similar observations. We could pay attention to the COD_mgL column (the last column) and how it relates to patterns in other variables.

- 1.

-

Holistic Overview

The heat map offers a compact, bird’s-eye view of the same dataset, with each row corresponding to one observation and each column corresponding to a different variable. The color scale (red = higher values, blue = lower values) reveals at a glance where certain variables are clustered at high or low intensities.

- 2.

-

Identifying Patterns and Clusters

- ○

Column-by-Column Inspection: By scanning down the columns, one can see if there are specific “bands” of color that reappear. These bands may indicate consistent parameter ranges across many observations—for instance, a group of runs with high TiO2_22 concentration or long reaction times.

- ○

COD Column: Focusing on the COD column (far right) shows how COD levels vary across the dataset. Observations near the top might display high COD values (red hues), whereas those at the bottom might be low COD (blue hues). One can then look horizontally to see if those high- or low-COD observations align with specific patterns in pH, UV light intensity, etc.

- 3.

-

Correlation and Co-occurrences

If certain columns tend to share similar color patterns (e.g., if high COD often co-occurs with high herbicide concentration or low reaction time), that hints at possible correlations or interactive effects among the variables. Although a heat map by itself does not provide a direct correlation measure, it is an excellent visual prompt for further statistical analysis or modeling.

- 4.

-

Data Quality and Consistency

Heat maps can also help detect missing data, strange anomalies, or uniform variables. If a column is entirely one color, it could indicate either a constant parameter or a measurement artifact that might need re-checking or further explanation.