Submitted:

06 January 2025

Posted:

07 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

In general, the conventional Lewis-Riesenfeld invariant-based inverse engineering is a nonadiabatic process that results in the adiabatic final states to achieve the shortcut to adiabaticity, which does not provide complete suppression of non-adiabaticity throughout the evolution. We propose a new method to accomplish the shortcut to adiabaticity through an entirely adiabatic path. This new method is developed using the number operator as an invariant of the Hamiltonian. This paper discusses the mathematical framework of the new method in two-level quantum system and analyzes its performance compared to the conventional Lewis-Riesenfeld invariant-based inverse engineering method.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

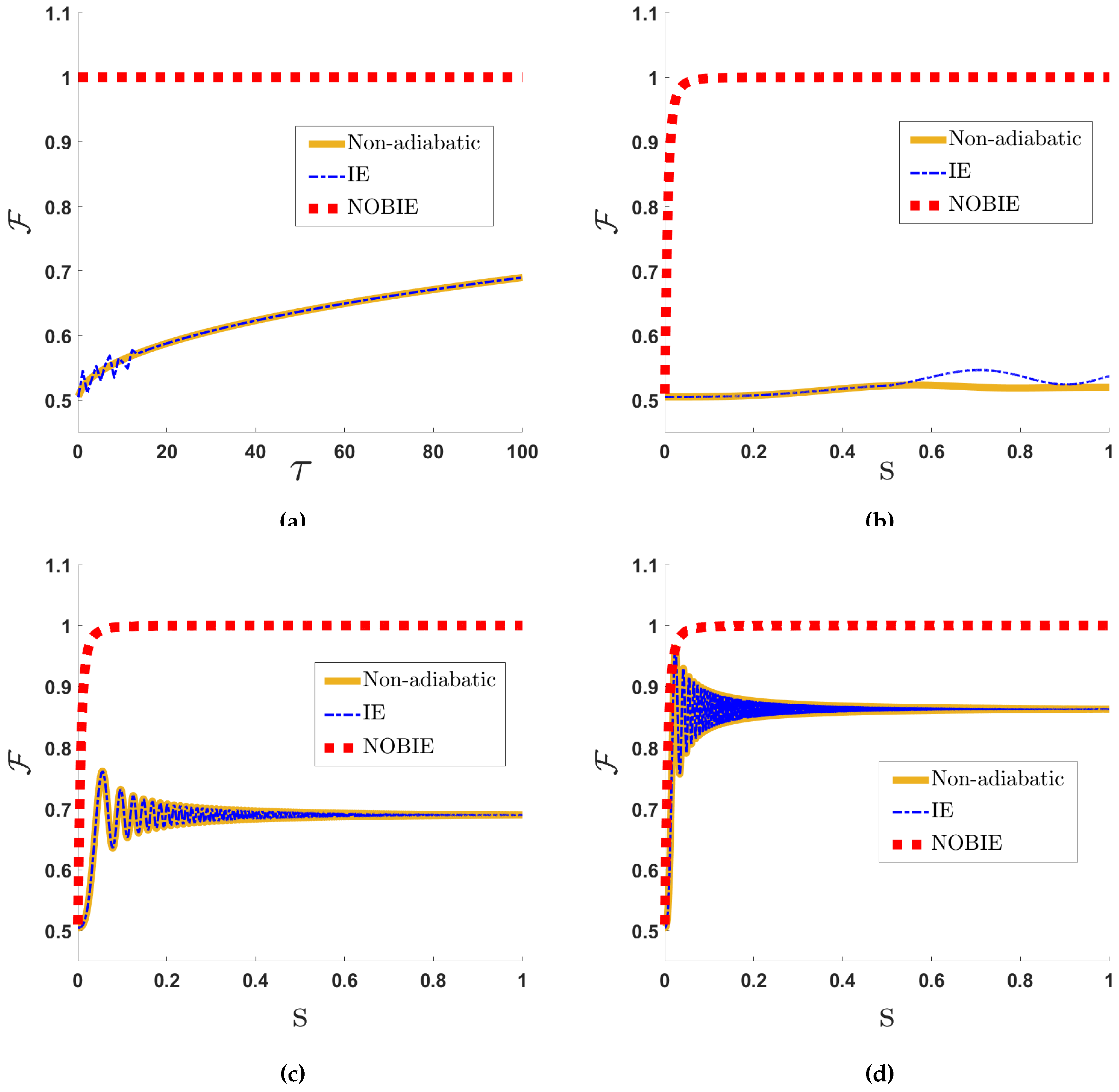

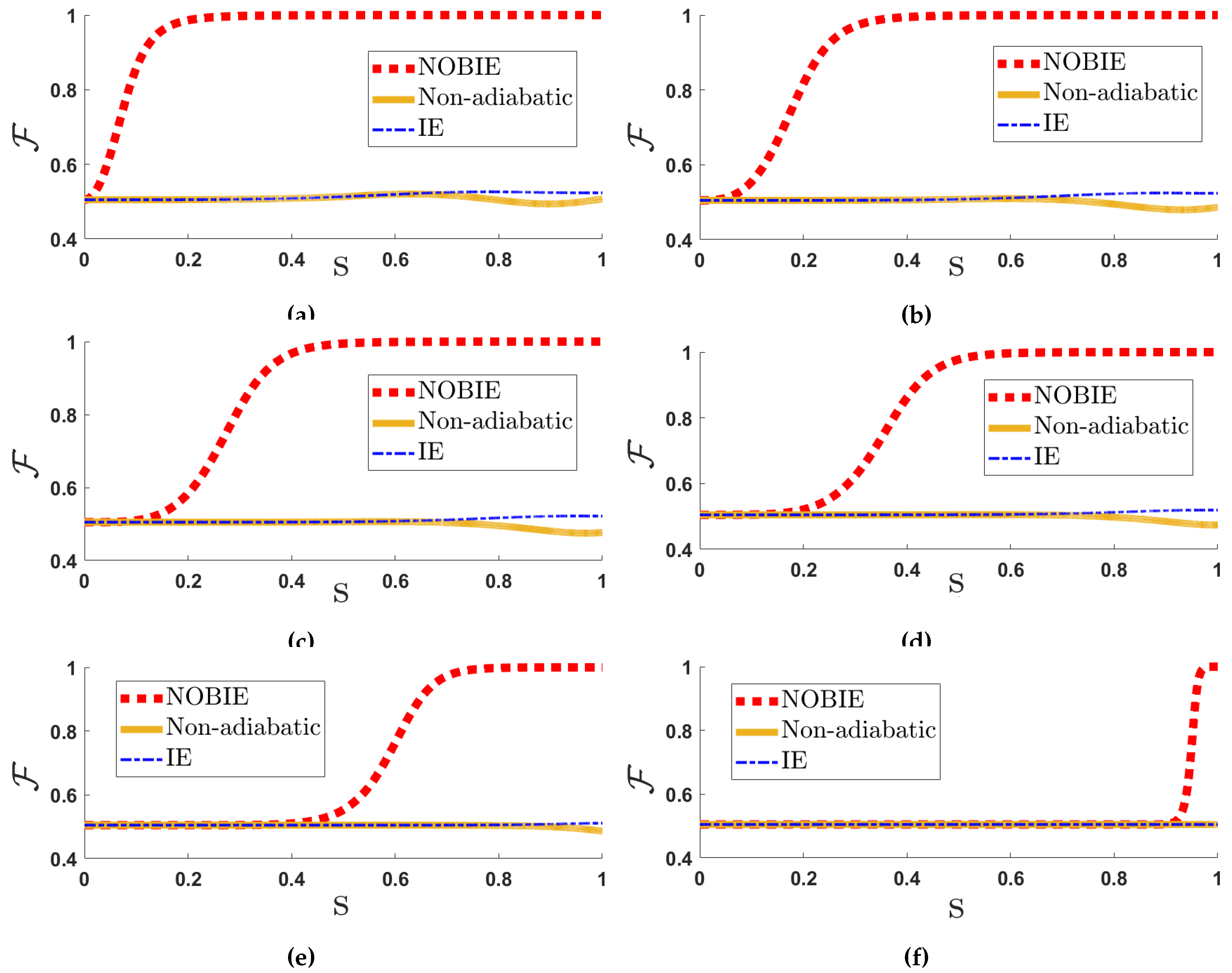

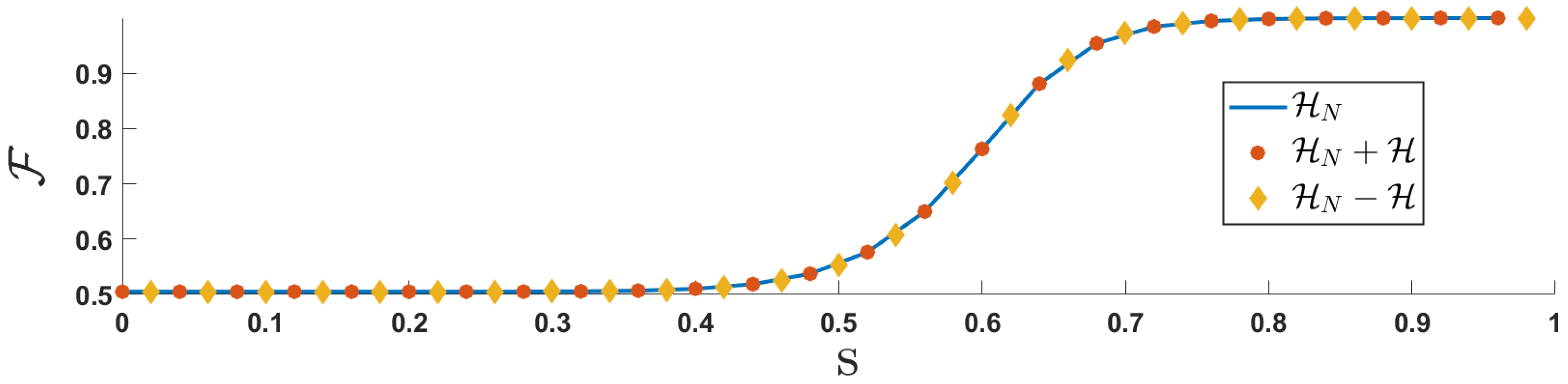

2. IE and NOBIE Methods for Two-Level Systems

2.1. IE Method for Two-Level Systems

2.2. NOBIE Method for Two-Level Systems

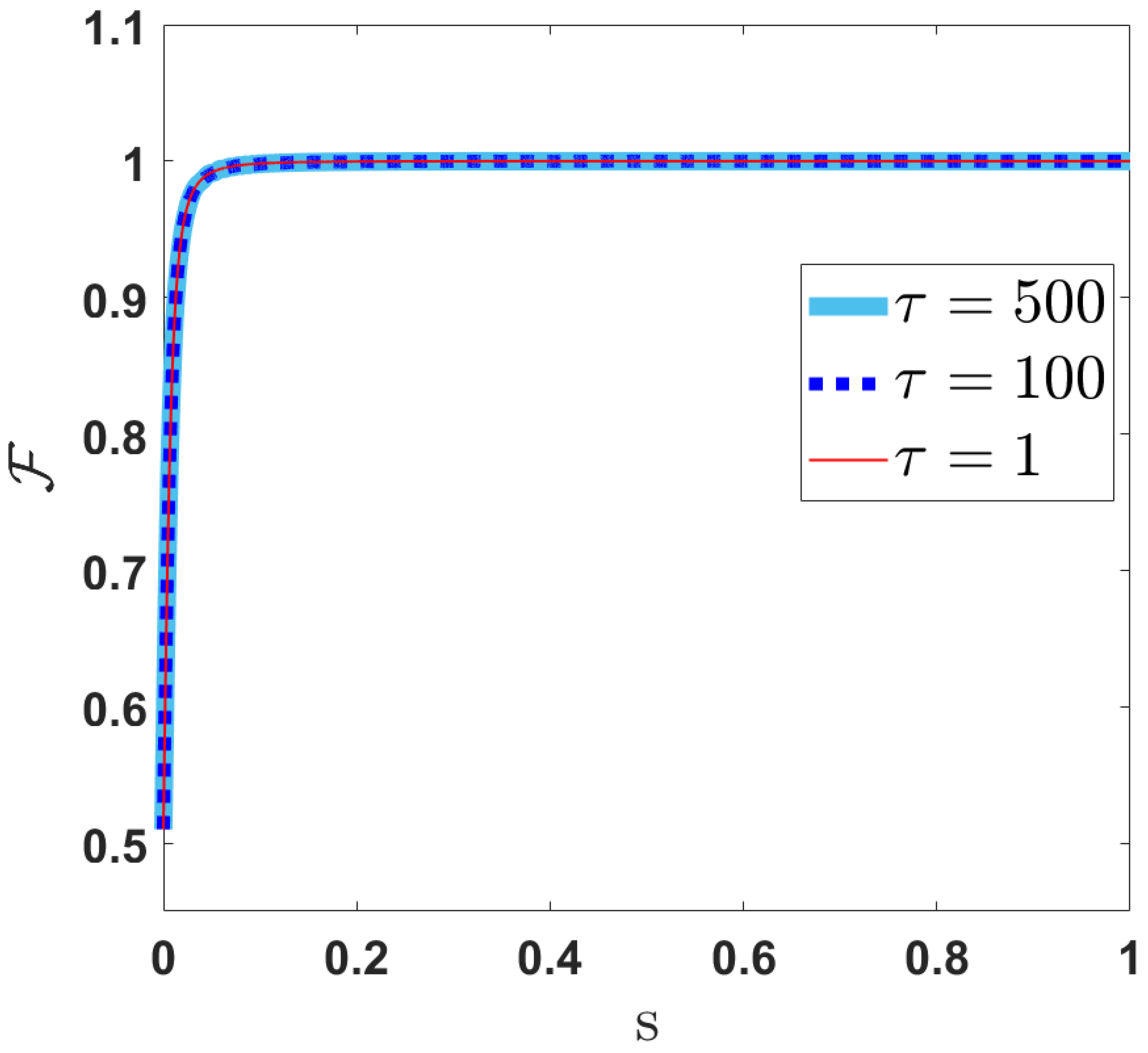

3. Discussion

4. Conclusion

Appendix A Numerical Simulation of Time-Ordered Evolution

- Step 1: Initialize the variables, , and (i.e., the total duration is specified for each figure in the main text.)

- Step 2: Define a set of values between and .

- Step 3: Iteratively find and for all the values of j.

- Step 4: Calculate using equation (A1).

- Step 5: Find .

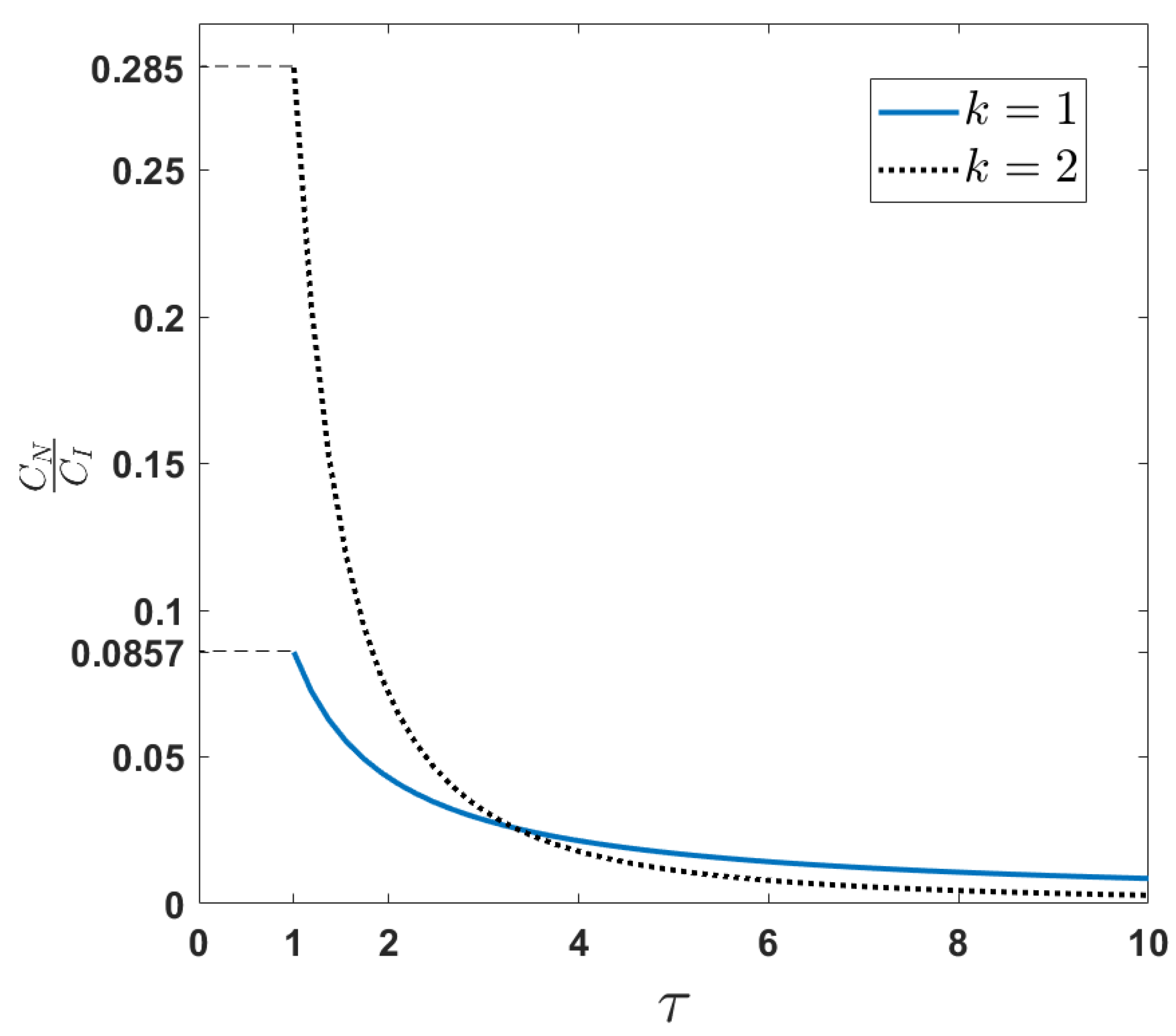

Appendix B: Analysis of Counter-Diabatic Driving

References

- L. Tisza “Generalized Thermodynamics," MIT Press, Cambridge, MA (1966).

- E. Torrontegui, S. Ibáñez, S. Martínez-Garaot, M. Modugno, A. del Campo, D. Guéry-Odelin, A. Ruschhaupt, X. Chen, and J. G. Muga, P. R. Berman, and C. C. Lin “Shortcuts to adiabaticity," Advances in Atomic,Molecular, and Optical Physics (Academic Press) 62, Chap. 2, pp. 117–169 (2013).

- D. Guéry-Odelin, A. Ruschhaupt, A. Kiely, E. Torrontegui, S. Martínez-Garaot, and J. G. Muga “Shortcuts to adiabaticity: Concepts, methods, and applications," Rev. Mod. Phys. 91, 045001 (2019).

- A. del Campo and K. Kim “Focus on Shortcuts to Adiabaticity," New Journal of Physics 21, 050201 (2019).

- Z. Yin, C. Li, J. Allcock, Y. Zheng, X. Gu, M. Dai, S. Zhang, and S. An “Shortcuts to adiabaticity for open systems in circuit quantum electrodynamics," Nat Commun 13, 188 (2022).

- G. Passarelli, R. Fazio, and P. Lucignano “Optimal quantum annealing: A variational shortcut-to-adiabaticity approach," Phys. Rev. A 105, 022618 (2022).

- Fu-Quan Dou, Yuan-Jin Wang and Jian-An Sun “Highly efficient charging and discharging of three-level quantum batteries through shortcuts to adiabaticity," Front. Phys. 17, 31503 (2022).

- T. Kiran and M. Ponmurugan “The invariant-based shortcut to adiabaticity for qubit heat engine operates under quantum Otto cycle," Eur. Phys. J. Plus 137, 394 (2022).

- K. Southwell “Quantum coherence," Nature 453, 1003 (2008).

- M. V. Berry “Transitionless quantum driving," J. Phys. A 42, 365303 (2009).

- K. Funo, J.-N. Zhang, C. Chatou, K. Kim, M. Ueda, and A. del Campo “Universal Work Fluctuations During Shortcuts to Adiabaticity by Counterdiabatic Driving," Phys. Rev. Lett. 118, 100602 (2017).

- Barış Çakmak “Finite-time two-spin quantum Otto engines: shortcuts to adiabaticity vs. irreversibility," arXiv:2102.11657 [quant-ph] (2021).

- S. Ibáñez, Xi Chen, E. Torrontegui, J. G. Muga, and A. Ruschhaupt “Multiple Schrödinger Pictures and Dynamics in Shortcuts to Adiabaticity," Phys. Rev. Lett. 109, 100403 (2012).

- H. R. Lewis and W. B. Riesenfeld “An exact quantum theory of the time dependent harmonic oscillator and of a charged particle in a time dependent electromagnetic field," J. Math. Phys. 10, 1458 (1969).

- Xi Chen, A. Ruschhaupt, S. Schmidt, A. del Campo, D. Guéry-Odelin, and J. G. Muga “Fast Optimal Frictionless Atom Cooling in Harmonic Traps: Shortcut to Adiabaticity," Phys. Rev. Lett. 104, 063002 (2010).

- E. Torrontegui, S. Ibáñez, Xi Chen, A. Ruschhaupt, D. Guéry-Odelin, and J. G. Muga “Fast atomic transport without vibrational heating," Phys. Rev. A 83, 013415 (2011).

- Xi Chen, E. Torrontegui, and J. G. Muga “Lewis-Riesenfeld invariants and transitionless quantum driving," Phys. Rev. A 83, 062116 (2011).

- Xi Chen, E. Torrontegui, Dionisis Stefanatos, Jr-Shin Li, and J. G. Muga “Optimal trajectories for efficient atomic transport without final excitation," Phys. Rev. A 84, 043415 (2011).

- E. Torrontegui, Xi Chen, M. Modugno, A. Ruschhaupt, D. Guéry-Odelin, and J. G. Muga “Fast transitionless expansion of cold atoms in optical Gaussian-beam traps," Phys. Rev. A 85, 033605 (2012).

- D. J. Griffiths and D. Schroeter “Introduction to Quantum Mechanics (3rd ed.)," Cambridge University Press, doi:10.1017/9781316995433 (2018).

- J. J. Sakurai and J. Napolitano “Modern Quantum Mechanics (2nd ed.)," Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/9781108499996 (2017).

- L. D. Landau “Zur Theorie der Energieübertragung II," Phys. Z. Sowjetunion 2, 46 (1932).

- C. Zener “Non-adiabatic crossing of energy levels," Proc. R. Soc. A 137, 696 (1932).

- Artur Ishkhanyan, Matt Mackie, Andrew Carmichael, Phillip L. Gould, and Juha Javanainen “Landau-Zener problem for trilinear systems," Phys. Rev. A 69, 043612 (2004).

- N. V. Vitanov and K.-A. Suominen “Nonlinear level-crossing models," Phys. Rev. A 59, 4580 (1999).

- Boyan T. Torosov and Nikolay V. Vitanov “Pseudo-Hermitian Landau-Zener-Stückelberg-Majorana model," Phys. Rev. A 96, 013845 (2017).

- O Abah, R Puebla, A Kiely, G De Chiara, M. Paternostro and S. Campbell “Energetic cost of quantum control protocols," New Journal of Physics, IOP Publishing 21, 10, 103048 (2019).

- O. Abah and E. Lutz “Performance of shortcut-to-adiabaticity quantum engines," Phys. Rev. E 98, 032121 (2018).

- T. Kiran and M. Ponmurugan “Invariant-based investigation of shortcut to adiabaticity for quantum harmonic oscillators under a time-varying frictional force," Phys. Rev. A 103, 042206 (2021).

- Y. Zheng, S. Campbell, G. D. Chiara, and D. Poletti “Cost of counterdiabatic driving and work output," Phys. Rev. A 94, 042132 (2016).

- B. Çakmak and Ö. E. Müstecaplıoglu “Spin quantum heat engines with shortcuts to adiabaticity," Phys. Rev. E 99, 032108 (2019).

- Hans De Raedt “Product formula algorithms for solving the time dependent Schrödinger equation," Comput. Phys. Rep. 7, 1 0167-7977 (1987).

- F. Jin, R. Steinigeweg, H. De Raedt, K. Michielsen, M. Campisi, and J. Gemmer “Eigenstate thermalization hypothesis and quantum Jarzynski relation for pure initial states," Phys. Rev. E 94, 012125 (2016).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).