Submitted:

03 January 2025

Posted:

06 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

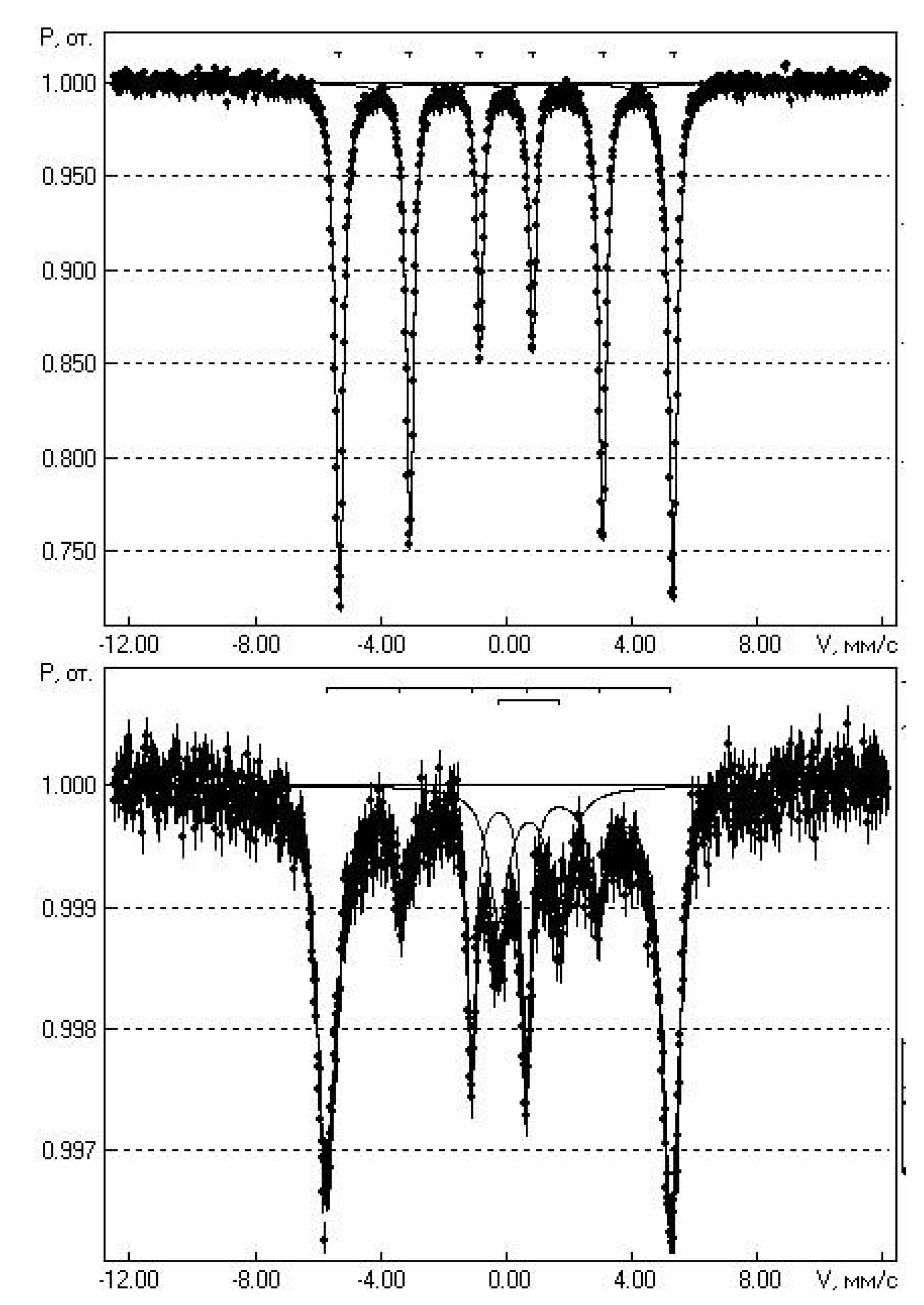

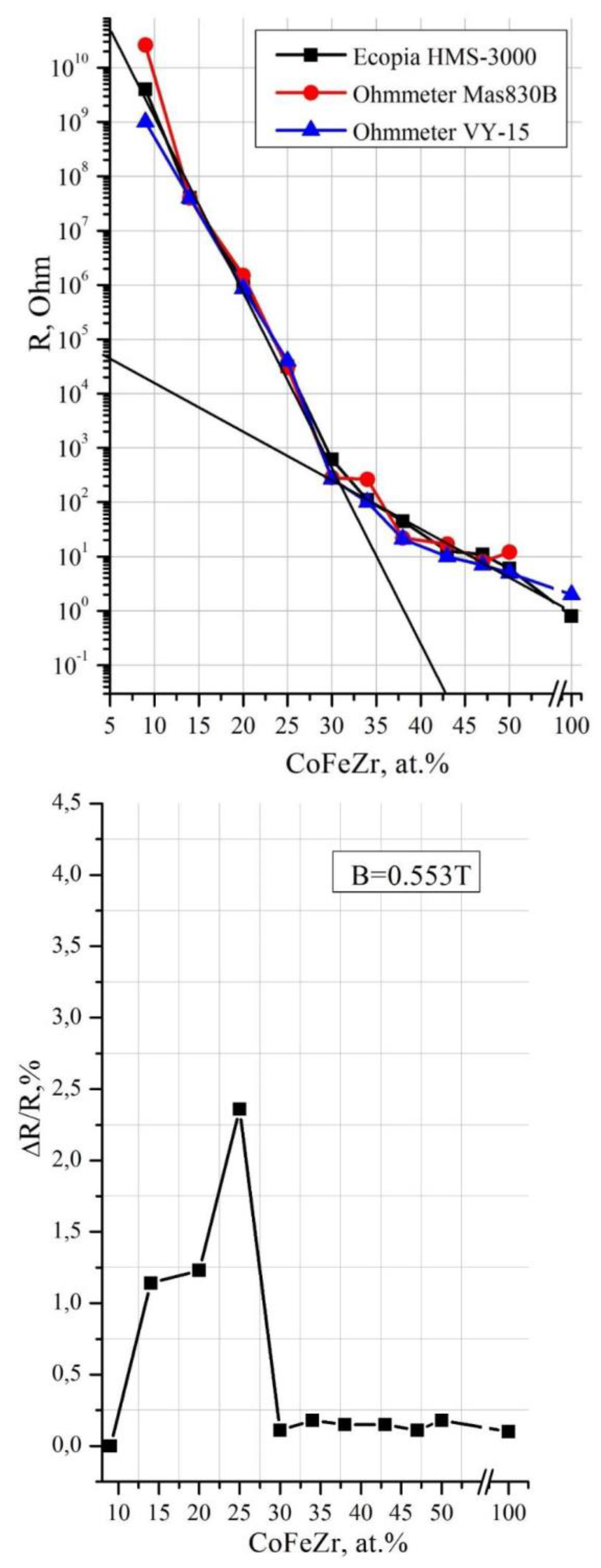

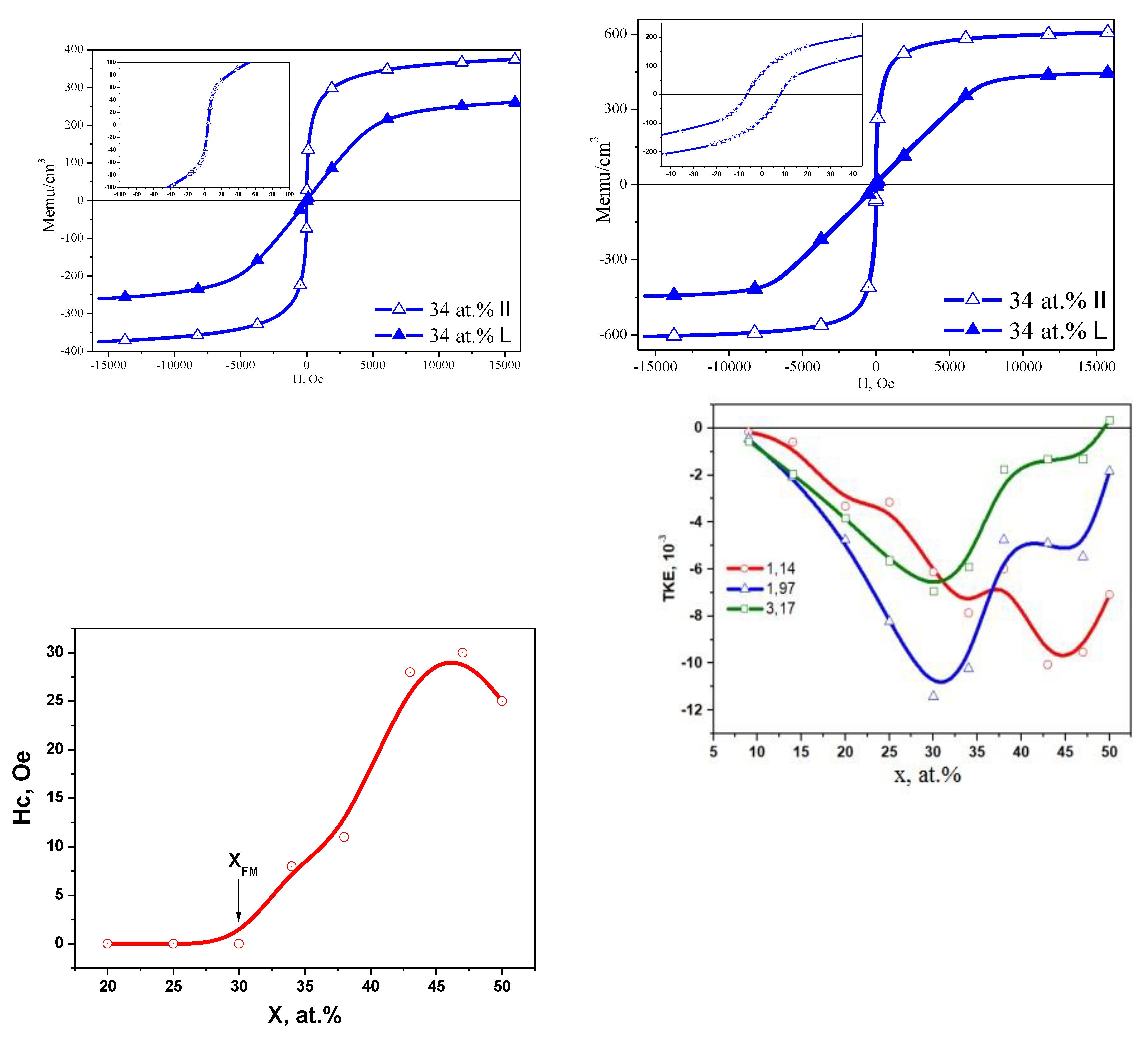

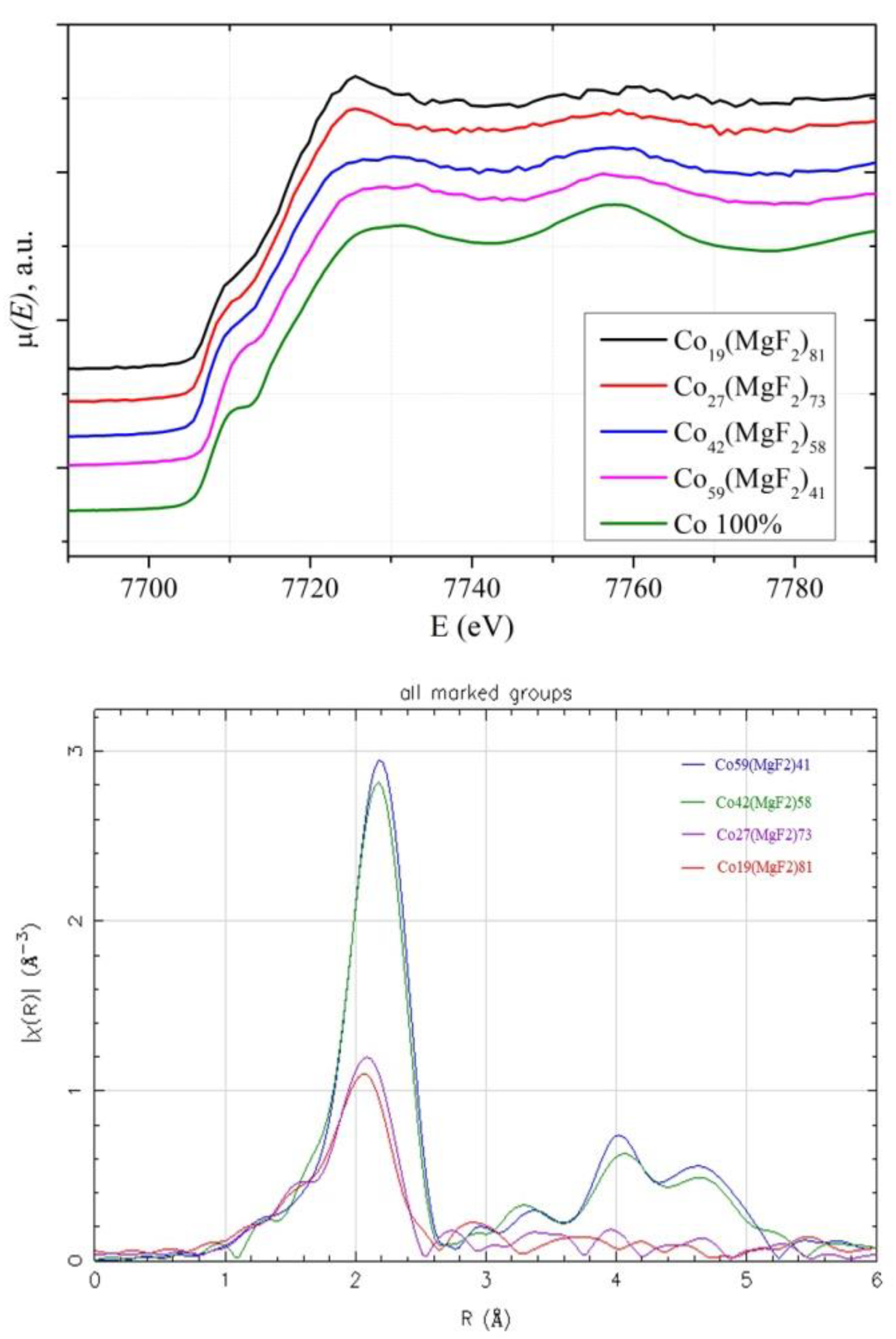

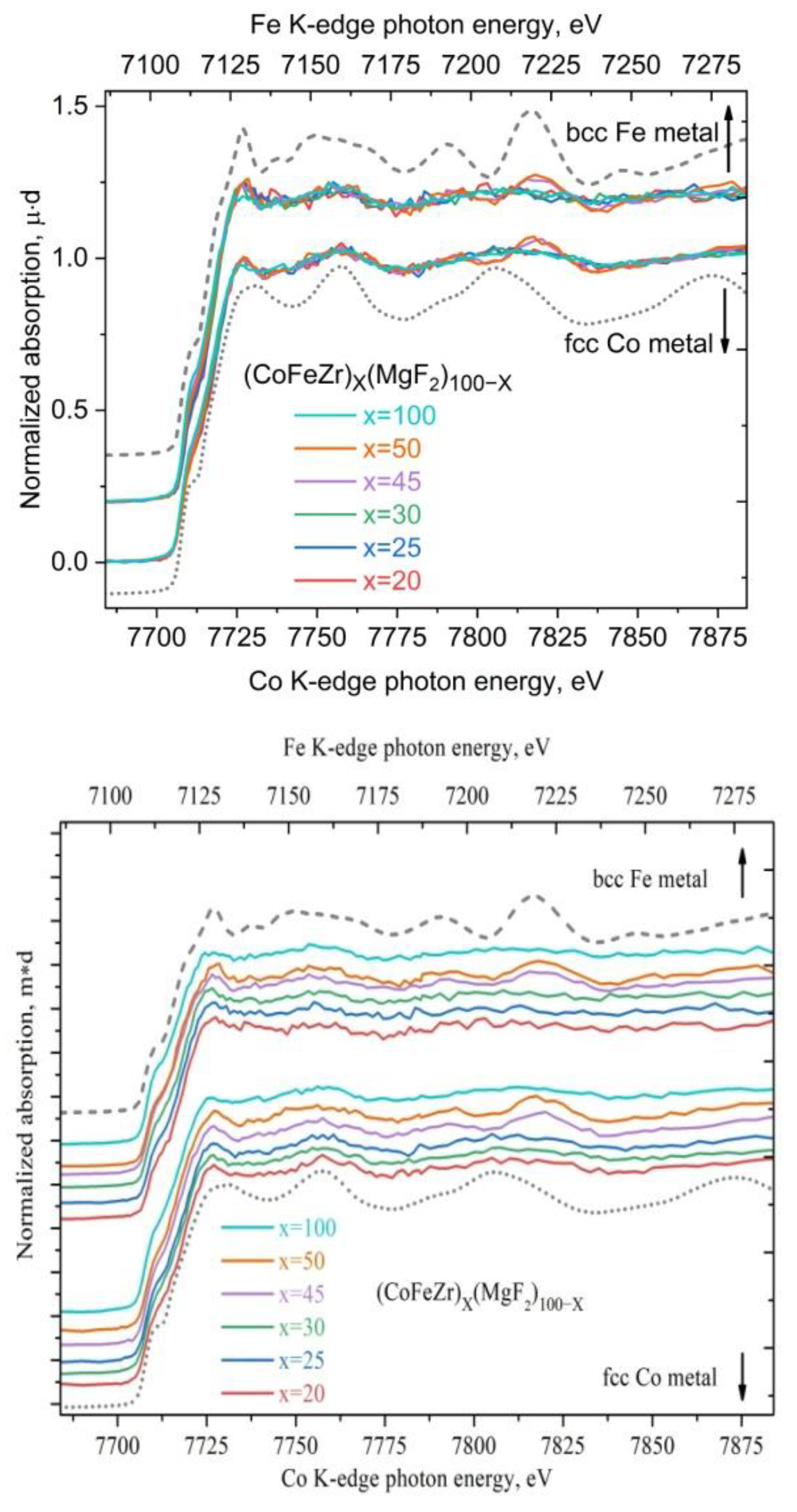

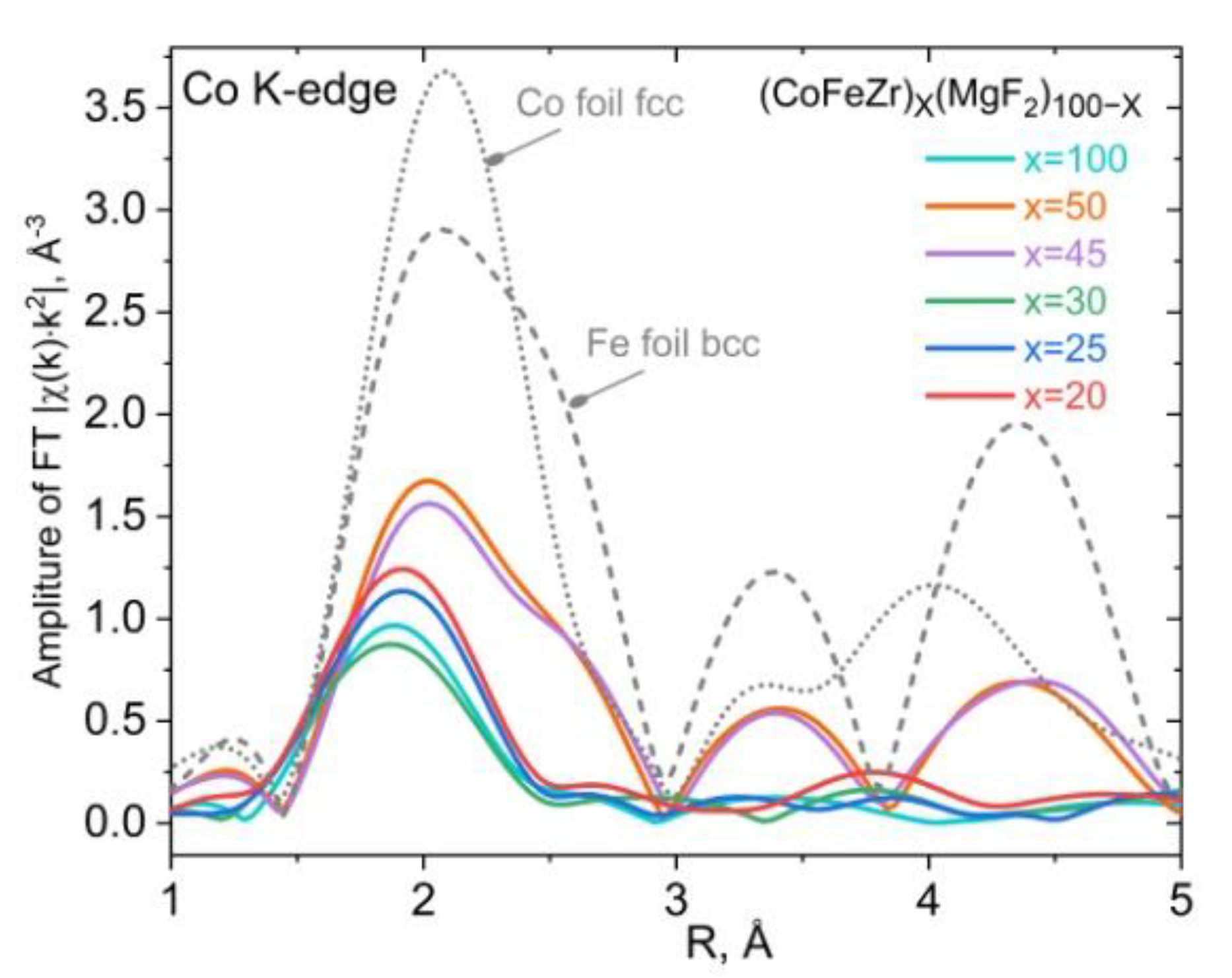

The article presents a comparative analysis of the results of complex studies of two nanocomposite systems: metal-dielectric Cox(MgF2)100-x and alloy-dielectric (CoFeZr)x(MgF2)100-x, obtained by ion-beam sputtering of composite targets in a wide range of compositions. Section 3 of this paper provides a mini-review of the investigations results about the features of the influence of the atomic composition and structural-phase state in the two systems on their nonlinear electroresistive, magnetoresistive, magneto-optical properties, published by us separately in each of the two systems in 2019-2023. In the metal-dielectric system Cox(MgF2)100−x, the formation of the hexagonal Co nanocrystals coincides with the achievement of the electric and magnetic percolation thresholds at xper=37 at.% and is accompanied by a transition from the superparamagnetic to the ferromagnetic state, which, with an increase of the metal content (>42 at.%), acquires a hard magnetic character with a coercive force of up to 95 Oe. In the alloy-dielectric system (CoFeZr)x(MgF2)100−x, the formation of the hexagonal CoFeZr nanocrystals coincides with the values of the electric and magnetic percolation thresholds at xper=34 at.%. Below this value, the nanocomposites exhibit superparamagnetic properties, and at high values of x > 34 at.%, they become soft magnets and remain so far beyond the percolation threshold and after the phase transition of nanocrystals from the hexagonal hcp to the cubical bcc structure at x = 43 at.%, with a maximum value of the coercive force Hc ≤30 Oe. One of the reasons for the significant decrease in Hc compared to the first system may be the formation of the paramagnetic phase FeF2 at the interphase boundaries of CoFeZr nanocrystals with the dielectric matrix MgF2, detected by the Mössbauer spectroscopy. Further in Section 4 for the first time, the concentration dependences of the oscillating fine structure of XANES K-absorption edges of Co atoms in the first system and Co and Fe atoms in the second system are presented, which undergoes changes at the percolation thresholds in each of the two systems and thus confirms the nonlinear nature of the electromagnetic properties changes in each of the two systems at the atomic level.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Objects and Methods of Research

3. Structural-Phase Transformations and Nonlinear Electromagnetic Properties of Variable-Composition Nanocomposites Cox(MgF2)100-x and (CoFeZr)x(MgF2)100-x

1.1. Metal-Dielectric Nanocomposites Cox(MgF2)100-x

2.2. Alloy-Dielectric Nanocomposites (CoFeZr)x(MgF2)100-x

4. XANES Spectra of the K-Edges of Co and Fe in Nanocomposites Cox(MgF2)100-x and (CoFeZr)x(MgF2)100-x

4.1. XANES Spectra of Co K-Edges in Cox(MgF2)100-x Nanocomposites

4.2. XANES Spectra of Co and Fe K-Edges in Nanocomposites (CoFeZr)x(MgF2)100-x

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- M.N.Baibich, J.M.Broto, A.Fert Van Dau, N. F.Petroff , P. Eitenne, G.Creuzet A.Friederich , J.Chazelas. Giant magnetoresistance of (001)Fe/(001)Cr magnetic superlattices. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1988, 61, 2472–2475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- J. Erkowitz, J.R. Mitchell, M.J.Carey, A.P.Young , S.Zhang, F.E.Parker, A. Hutten , G.Thomast. Giant Magnetoresistance in Heterogeneous Cu-Co Alloys. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1992, 68, 3745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- J.Q. Xiao , J.S. Jiang, C.L.Chien. Giant Magnetoresistance in Nonmnltilayer Magnetic Systems. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1992, 68, 3749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- M. P. Levy. Giant Magnetoresistance in Magnetic Layered and Granular Materials. Solid State Phys. Adv. Res. Appl. 1994, 47, 367–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- T. Miyazaki, N.Tezuka. Giant magnetic tunneling effect in Fe/Al2O3/Fe junction. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 1995, 139, L231–L234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- J.S.Moodera, L.R. Kinder, T.M. Wong, R. Meservey. Large Magnetoresistance at Room Temperature in Ferromagnetic Thin Film Tunnel Junctions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1995, 74, 3273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- H. Fujimori, S.Mitani, S.Ohnuma, T. Ikeda, T.Shima, T. Masumoto. High electrical resistivity behaviour of Fe- and Co-based soft magnetic heterogeneous alloys. Mater. Sci. Eng. A. 1994, 181–182, 897–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- H. Fujimori, S. Mitani, S. Ohnuma. Tunnel-type GMR in Co-Al-O insulated granular system - its oxygen-concentration dependence. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 1996, 156, 311–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S. Maekawa, U. Gafvert. Electron tunneling between ferromagnetic films. IEEE Trans. Magn. 1982, 18, 707–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S.A.Gridnev, Y.E. Kalinin, A.V. Sitnikov, O.V.Stogne. Nonlinear phenomena in nano- and microheterogeneous systems. BINOM. Knowledge laboratory [in Russian], Moscow. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Stognei, Electrical transfer and magnetic properties of amorphous nanogranular metal-dielectric composites. Abstract of a dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Physical and Mathematical Sciences, Voronezh State Technical University, Voronezh, 2004; p. 280.

- N . Kobayashi, S.Ohnuma, T.Masumoto, H. Fujimori. (Fe-Co)-(Mg-fluoride) insulating nanogranular system with enhanced tunnel-type giant magnetoresistance. J. Appl. Phys. 2001, 90, 4159–4162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D. Yao, S.Ge, B.Zhang, H. Zuo, X. Zhou. Fabrication and magnetism of Fe65 Co35 -MgF 2 granular films for high frequency application. J. Appl. Phys. 2008, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- T. Tregubova, O.Stognei, V. Kirpan. Magnetotransport properties of Cox(MgF2)100-x oxygen-free nanocomposites. EPJ Web of Conferences.Moscow International Symposium on Magnetism; 2018; p. 01014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- T. Tregubova, O. Stogney, I. Tregubov, V.Kirpan et al. Electrical and magnetoresistive properties of oxygen-free composites Cox(MgF2)100-x. Vestnik of Voronezh State Technical University. 2017, 13, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- E.A.Ganshina, S.A Ivkov, E.P. Domashevskaya et al. Effect of phase transformations of a metal component on the magneto-optical properties of thin-films nanocomposites (CoFeZr)x(MgF2)100-x. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 1666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- E.Ganshina, V. Garshin, N.Perova, G.Zykov, A. Aleshnikov, Y.Kalinin, A.Sitnikov. Magneto-optical properties of nanocomposites ferromagnetic-carbon. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2019, 470, 135–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- E.A Balykina, E.A.Gan’shina, G.S.Krinchik. Magnetooptic properties of rare-earth orthoferrites in the region of spin reorientation transitions. JETP 1987, 93, 1879–1887. [Google Scholar]

- В.Ravel, M.Newville. ATHENA, ARTEMIS, HEPHAESTUS: data analysis for X-ray absorption spectroscopy using IFEFFIT. J. Synchrotron Radiat. 2005, 12, 537–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- E.P. Domashevskaya, S.A.Ivkov, A.V. Sitnikov, O.V. Stogney, A.T.Kozakov, A.V.Nikolsky. Formation of nanocrystals of a metal or dielectric component depending on their *relative content in Cox(MgF2)1-x composites. Solid State Physics 2019, 61, 211–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- E.P. Domashevskaya, S.A Ivkov, O.V. Stogney, A.V.Sitnikov. Mutual influence of the relative content of the metallic and dielectric component on the phase composition and substructure of nanocomposites Cox(MgF2)1-x. 8th International Conference on Nanotechnology and materials science, Netherlands, Amsterdam, April 24-26. 2019; p. 81. [Google Scholar]

- S.A. Ivkov, K.A. Barkov, E.P.Domashevskaya et al. Nonlinear Transport and Magnetic/Magneto-Optical Properties of Cox(MgF2)100-x Nanostructures. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 2992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- E.P. Domashevskaya, S.A. Ivkov, A.V. Sitnikov et al. The features of CoFeZr nanocrystals formation in film composites of (CoFeZr)x(MgF2)100-x. Journal of Alloys and Compounds. 2021, 870, 159398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- E.P Domashevskaya, S.A. Ivkov, P.V. Seredin, D.L. Goloshchapovet al. Nonlinear electromagnetic properties of thinfilm nanocomposites (CoFeZr)x(MgF2)100−x. Magnetochemistry. 2023, 6, 160. [Google Scholar]

- M.E. Тhomas, K.A. Stefan, M.C. Thomas, T. Kim. Infrared properties of polycrystalline magnesium fluoride. Infrared Physics & Technology. 1998, 39, 213–222. [Google Scholar]

- V. Jaccarino, L.R. Walker. Discontinuous occurrence of localized moments. Phys. rev. Lett. 1965, 15, 258–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R. Grössinger, G. Hilscher, G. Wiesinger. Temperature and concentration dependence of magnetization, magnetocrystalline anisotropy and hyperfine parameters in Zr(Fe1-xAlx)2. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 1981, 23, 47–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. El-Hilo, K. O’Grady, R.W. Chantrell. Chantrell, The ordering temperature in fine particle systems. 1992, 117, 21–28. [Google Scholar]

- D. Norman. X-ray absorption spectroscopy (EXAFS and XANES) at surfaces. Journal of Physics C: Solid State Physics. 1986, 19, 3273–3311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- G. Bunker. Introduction to XAFS: A practical guide to absorption fine structure spectroscopy; Published in the United State of America by Cambridge university press: New York, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Ya. V. Zubavichus, Yu. L. Slovokhotov. X-ray synchrotron radiation in physicochemical studies. Advances in Chemistry (Rus) 2001, 70, 429–463. [Google Scholar]

- G. V. Fetisov. Synchrotron radiation: methods for studying the structure of matter. Moscow, FIZMATLIT. 2007. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).