1. Introduction

It is a known fact that the ferrites belong to magnetic spinel structure having a chemical formula AB

2O

4 (where A & B are tetrahedral (A), and octahedral (B) sites, respectively). For instance, NiFe

2O

4, MgFe

2O

4, CuFe

2O

4, ZnFe

2O

4, MnFe

2O

4, FeFe

2O

4, CoFe

2O

4, CdFe

2O

4 etc., are the ferrite ceramics exhibiting the ferrimagnetic nature. These are classified into normal spinels, inverse spinels, and mixed spinels based on the degree of inversion (δ) which describes the cationic distribution at A, and B-sites. That is, δ=1 for normal spinel (Ex: ZnFe

2O

4, MgAl

2O

4, CdFe

2O

4 etc., in bulk form), δ=0 for inverse spinels (NiFe

2O

4, Fe

3O

4, CoFe

2O

4 etc., in bulk form), and δ=0.25 (0<δ<1) for mixed spinels (NiFe

2O

4, & MgFe

2O

4 etc., in nanoform) [

1,

2]. The pictorial representation of classification of spinels, and alignment of magnetic spins is shown in

Figure 1. The properties of ferrites in bulk form are usually different from nano as reported in literature [

2]. For example, NiFe

2O

4 is inverse spinel in bulk form, whereas the same shows mixed spinel structure in nanoform. This can be attributed to the cation distribution between A, and B-sites. Owing to this interesting behavior in nickel ferrite, several researchers worked on bulk, and nano nickel ferrites for various structure, optical, magneto-electric, morphological, electrochemical, microwave, and catalytic properties [

2].

Investigations were performed by scientists, and further started working on various rare-earth dopants, and substituents into the spinel nickel ferrite system. In this regard, Parida et al. [

3], reported the magnetic, and magnetoelectric behavior of Gd-doped nickel ferrite, and barium titanate nanocomposites. Sattibabu et al. [

4], investigated the neutron diffraction, and magnetic properties of NiFe

2-xSc

xO

4. Hao et al. [

5], provided the enhanced resistive switching, and magnetic nature of NiGdFe

2O

4 thin films. Chauhan et al. [

6], prepared the NiDyFe

2O

4 nanopowders via combustion technique, and studied the structure, microstructure, and electrical behavior. Dixit et al. [

7], reported the magnetic resonance behavior of NiGdCeFe

2O

4 nanoparticles. Sahariya et al. [

8], synthesized the iron deficient NiGdDyFe

2O

4 samples, and studied magnetic Compton scattering nature. Sonia et al. [

9], synthesized the NiGdFe

2O

4 nanocrystallites using Sol-Gel method, and investigated the structure, microstructure, and magneto-dielectric behavior. Ugendar et al. [

10], synthesized the iron deficient NiGdFe

2O

4, NiDyFe

2O

4, and NiHoFe

2O

4, and reported the magnetic behavior, Mossbauer study, and cationic distribution. Akhtar et al. [

11], prepared the graphene based NiReFe

2O

4 (Re=Yb, Gd & Sm) nanocomposites, and reported the structural, magnetic, bandgap, and conductive behavior. Guo et al. [

12], reported the structure, and magnetic nature of NiSmFe

2O

4 nanofibers. Chen et al. [

13], prepared the nickel ferrite hollow nanospheres via gel assisted hydrothermal method, and reported the magnetic properties. Dixit et al. [

14], prepared the NiCeFe

2O

4 nanoparticles, and reported the structure, magnetic nature, and electronic properties. Joshi et al. [

15], reported the structure, magneto-dielectric nature of NiGdFe

2O

4 nanoparticles. Shah et al. [

16], provided the review in detail on novel catalysts for visible light assisted dye degradation in case of spinel structured ceramics. Sabikoglu et al. [

17], reported the structural, and magnetic behavior of NiNdFe

2O

4 ceramics. Almessiere et al. [

18], also provided the structure, and magnetic nature of NiDyFe

2O

4 nanoparticles. Yao et al. [

19], prepared the NiGdFe

2O

4 thin films through Facile Sol-Gel method, and reported the structural, optical, magnetic behavior. Almessiere et al. [

20], evidently discussed the effect of dysprosium element on nickel ferrite in respect of magnetic behavior. Yehia et al. [

21], synthesized the NiGdFe

2O

4 nanoparticles, and investigated the structural, and magnetic properties along with the effect of Gd in the spinel system. From this vast literature survey, it was understood that the Ni

1-xGd

xFe

2O

4 (x=0.02-0.08) nanoparticles were prepared by several scientists reporting the structure, and magnetic nature. Moreover, the preferred methods were considered as sol-gel, autocombustion, solid state reaction, and thin film methods. At this juncture, an attempt was made to prepare the Ni

1-xGd

xFe

2O

4 (x=0.02-0.08) nanoparticles via hydrothermal method (provides benefits like inexpensive, easy synthesis, low temperature requirement, less time consumption, high crystallinity etc.) investigating the detailed structural (X-ray diffraction study), microstructural (grain size, and particle size analysis), electrical (dielectric, electrical conductivity, impedance parameters), magnetic (M-H curves, cation distribution), and thermal (TG-DTG & TG-DSC) properties.

4. Results, and Discussion

The X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns of x=0.02-0.08 evidenced the phase purity, crystallinity, unit cell dimensions etc. In

Figure 4, the ferrites showed significant intensity for all phases. All the samples expressed, the single-phase cubic spinel structure. But, on the other hand, a minute phase is detected at 2-theta angle at 43.56

o. This is obtained due to the trivalent rare-earth cations (Gd

3+) present in the nickel ferrite system. Shannon ionic radii table [

22], evidences a fact that the ionic radii of Ni

2+=0.060 nm, Gd

3+=0.0938 nm, Fe

2+=0.063 nm, and Fe

3+=0.049 nm cations can be responsible for either single-phase or multi-phase structure. On doping Gd into nickel ferrite system, due to high ionic radii difference (>15 %), Gd

3+ cations cannot replace Ni

2+/Fe

3+ ions without any consequences. The conversion of Fe

3+ to Fe

2+ becomes predominant upon occupying the Ni

2+ site. This reinforces the increase of unit cell dimensions. Herein, the high ionic radii difference, and different valency positions are responsible for the formation of secondary phases as suggested by Hume-Rothery rule [

23]. Thus, a small secondary phase is evolved at 43.56

o. The similar observation is reported by Raghuram et al. [

24]. The average crystallite size (D

a) of all diffraction peaks is calculated using Scherrer equation: D=0.9λ/βCosθ, where ‘β’ is the full width half maxima, and ‘θ’ is the angle of diffraction [

25]. The D

a value is first decreased from 24.8 nm to 18.7 nm (for x =0.2-0.4). Further, it is increased to 43.4 nm from x=0.4-0.8. This kind of variation is ascertained owing to the effect of micro-strain as a function of ‘x’. The maximum intensity is recorded for (311) plane of x=0.02-0.08. The lattice constants are computed using a=d (h

2+k

2+l

2)

0.5, where d=interplanar spacing, and (hkl) are the Miller indices. The results obtained (see

Table 1) suggested that the lattice constants are increasing from 0.8956 to 0.8975 nm with increase in ‘x’ from 0.02-0.08. This kind of manner is achieved owing to the high ionic radii of Gd

3+ cations, and conversion of ferric ions to ferrous ions within the cubic spinel system (NiFe

2O

4). Moreover, the phase shift provided in the inset of

Figure 1 towards lower 2-theta angles indicates the decrease of lattice constants. Subsequently, the unit cell volume (V=a

3) of x=0.02-0.08 showed the increasing trend from 0.622 to 0.626 (Å)

3. The theoretical density is calculated using ρ

x =ZMW/NV, where Z=8 (effective number of atoms per unit cell), MW= compositional molecular weight, N=6.023*10

23, and the other symbols have their own meaning. The obtained densities showed that the values are increasing from 5.047 to 5.143 g/cm

3 with x. This kind of trend is attributed to the increase of compositional molecular weight from 236.355 to 242.268 g/mole as a function of ‘x’. Similarly, the surface area (S=6/D

aρ

x) is calculated and found to be varying inversely proportional to the crystallite size. The values are found to be altering between 26.9 to 63.2 m

2/g.

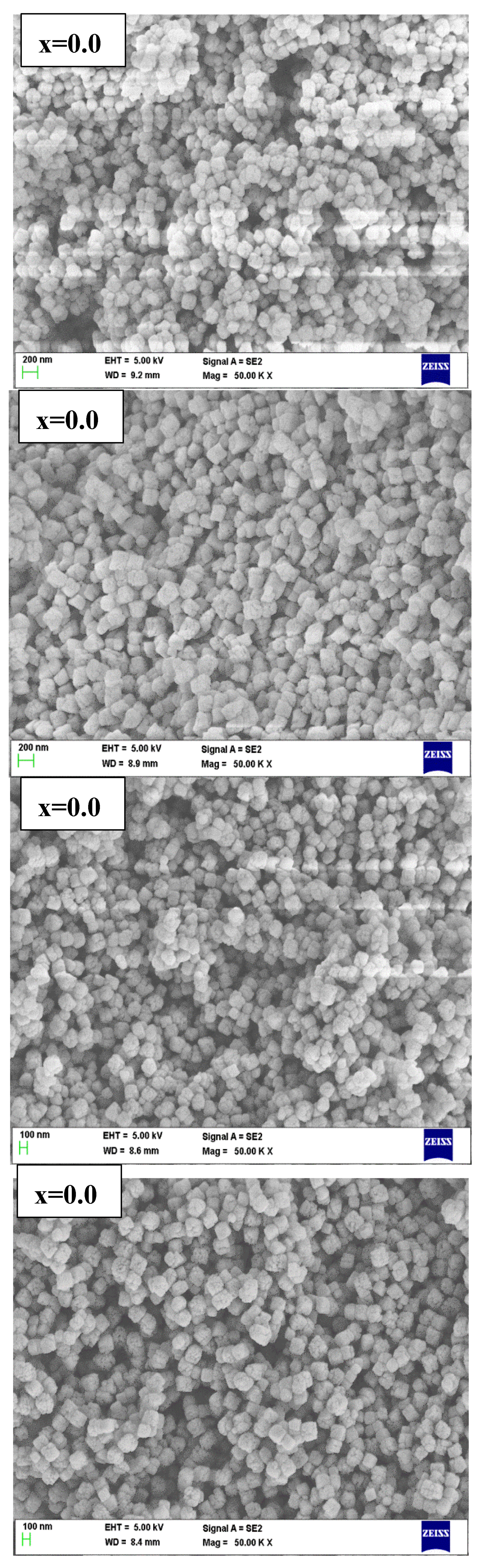

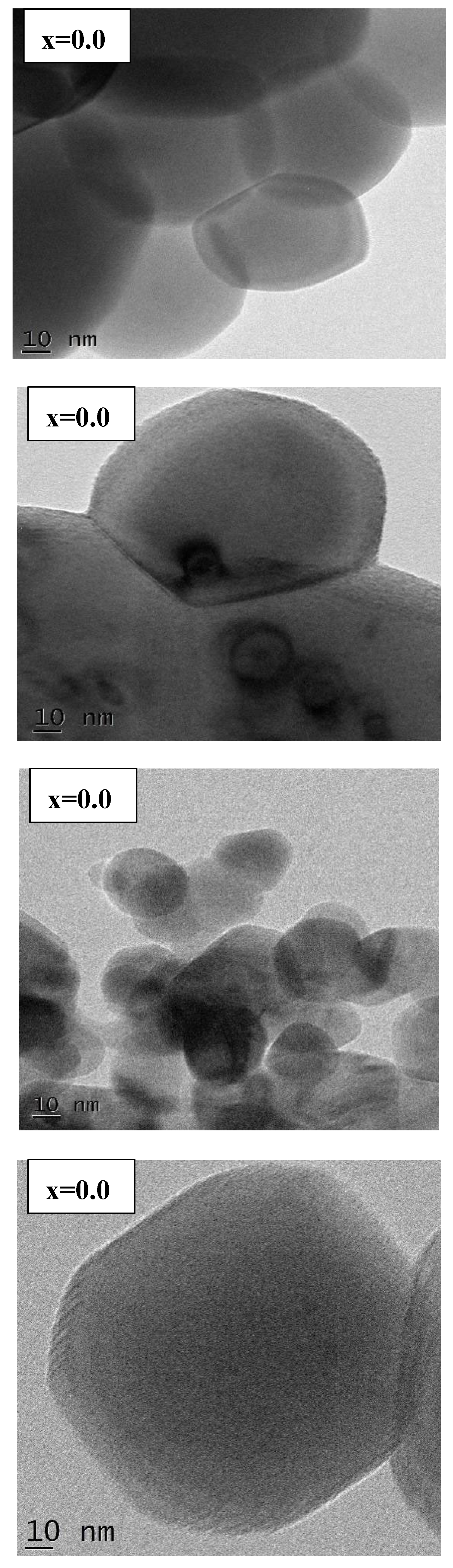

The surface morphology evidenced that the stones like (almost nanocubes) grains are found in FESEM images of x=0.02-0.08 (

Figure 5). Even in the HRTEM images (

Figure 6) also, the similar nanoparticles are noticed. For all FESEM images, in order to determine the grain size, the linear intercept method is used. According to this method, the average grain size G

a is calculated using an equation: 1.5L/MN, where L stands for test line length, M refers to magnification, and N shows the number of grains intersecting the test line [

24]. The results offered that the Ga value is varying unsystematically from 111 to 180 nm. That is, for x=0.02 (149 nm) to 0.04 (168 nm), it is increased, and for x=0.06 (111 nm) to 0.08 (180 nm), again it is increased. It is also observed that the homogeneity is increased with increase in Gd-content. Moreover, the shape of grain is little bit converted to almost nanocube with ‘x’. In HRTEM (

Figure 6) also, the nanoparticles are not of pure nanocubes. Minute amount of distortion happened. It may be due to selected spot of the sample dispersed in the copper grid. For x=0.08 sample, it looks to be nanocubes having smoothened corners. Due to magnetic interactions, the grains/particles are connected to each other within the morphology.

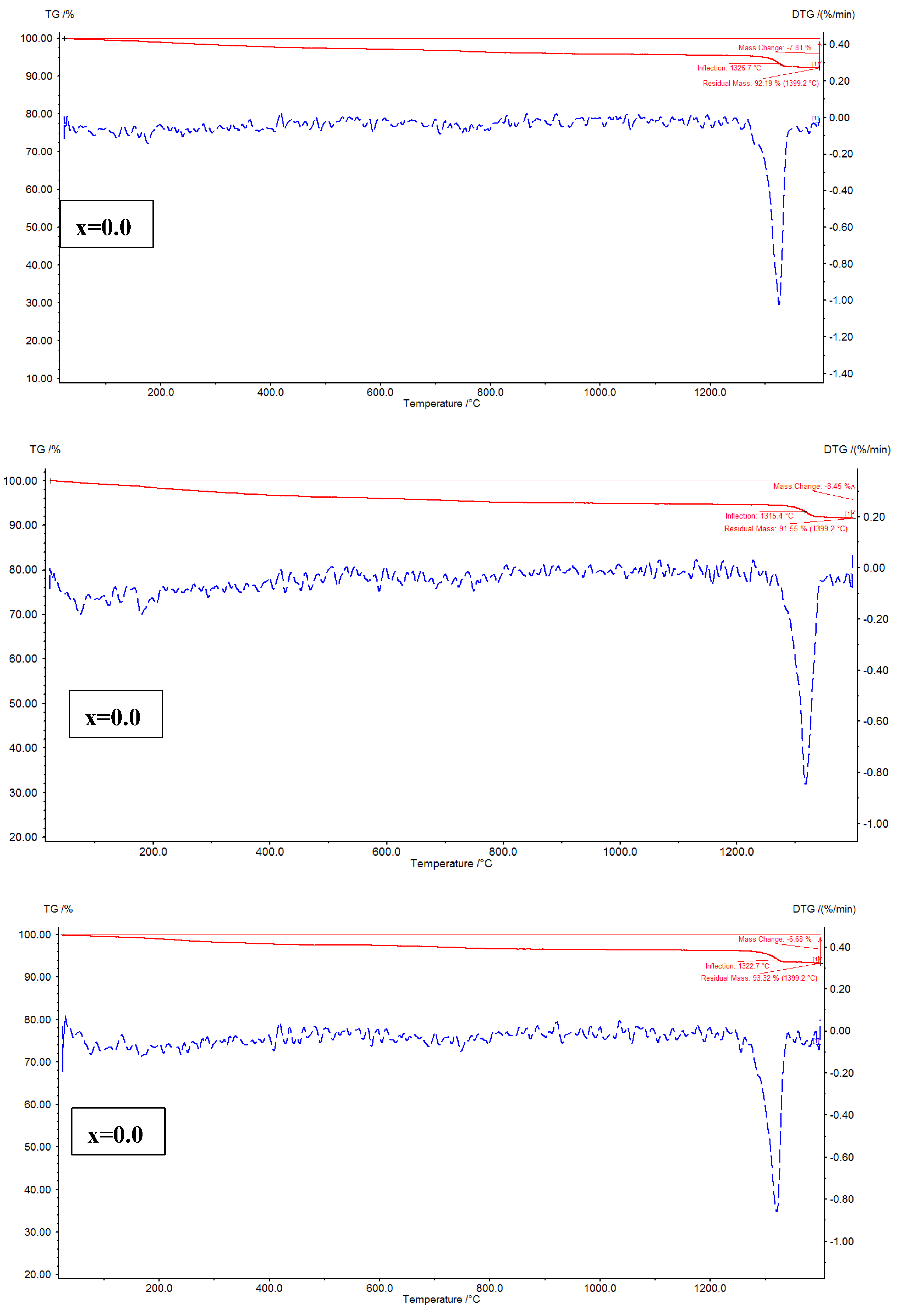

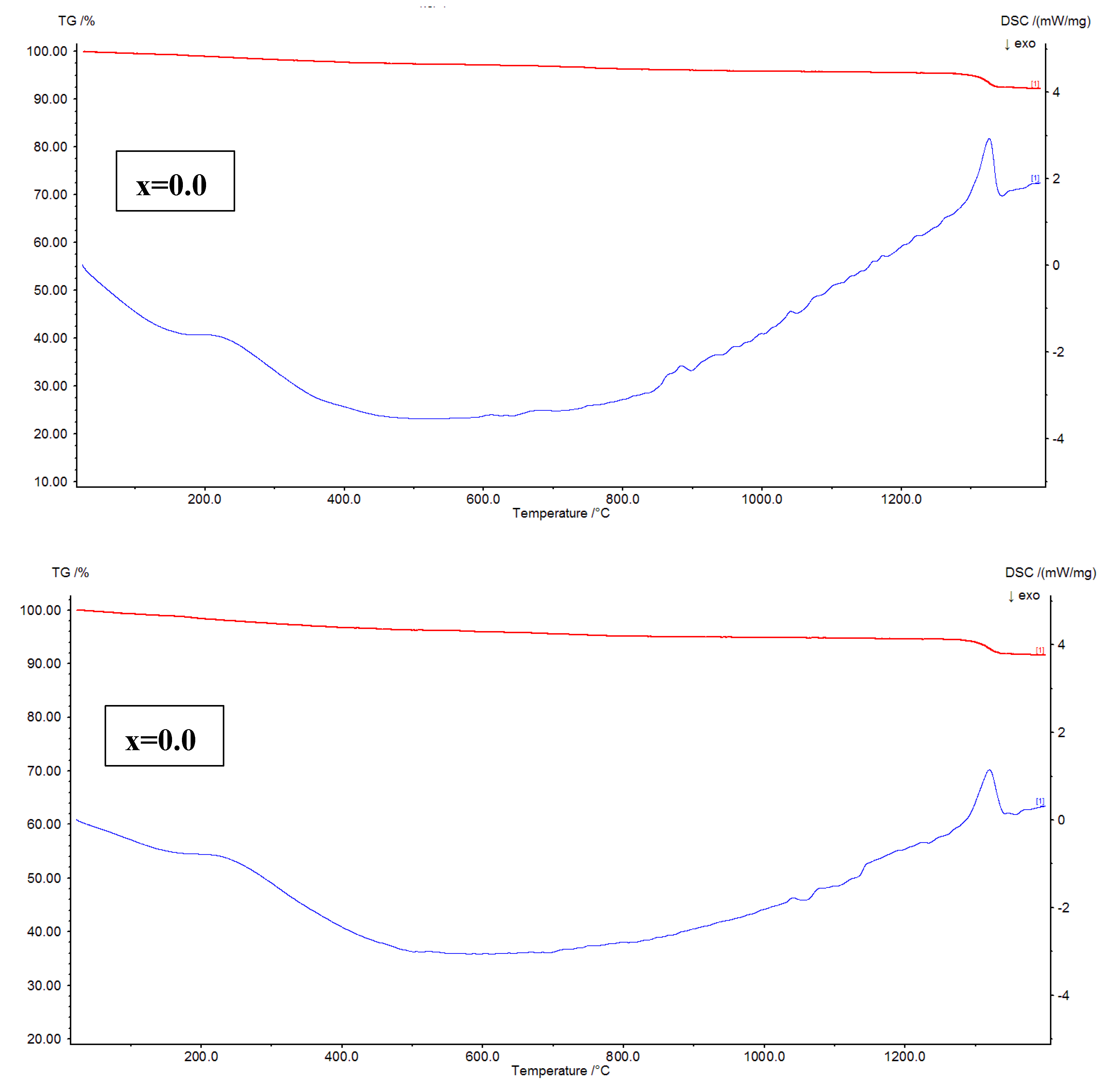

The thermal analysis of Ni

1-xGd

xFe

2O

4 (x=0.02 – 0.08) nanoparticles is performed using TG-DTG, and TG-DSC curves. It is well-known that the TG plots evidence the mass loss with increase of temperature, whereas the DTG plots offer the thermogram peaks where the hydrate ions can be removed, and decomposition of nitrates (organic/inorganic) takes place. Besides, the decomposition of metallic/non-metallic species can be identified. In

Figure 7, TG-DTG plots are shown. The plots addressed a fact that for x=0.02, and 0.04, the mass losses are noted to be 7.81, and 8.45 %, respectively. It is evident that the mass loss is increased from x=0.02 to 0.04. In the similar fashion, for x=0.06, and 0.08, the mass losses are found as 6.68 to 7.13 %, respectively. The similar trend is followed for these samples like x=0.02-0.04. As a whole, it is confirmed that the x=0.04 showed high mass loss while x=0.06 provided low mass loss. Further, the DTG plots of x=0.02-0.08 revealed three considerable peak temperatures around 200, 400, and 1330

oC. The thermogram peak temperatures of spinel ferrites at around 200

oC indicate the removal hydrate ions from the samples. Similarly, the nitrates can be removed from the samples at around 400

oC. The sharp peaks are seen at around 1330

oC for x=0.02-0.08 expressing the decomposition of residual species. For x=0.02-0.08, the residual peak temperature is increasing with increase in ‘x’ from 1315 to 1332

oC.

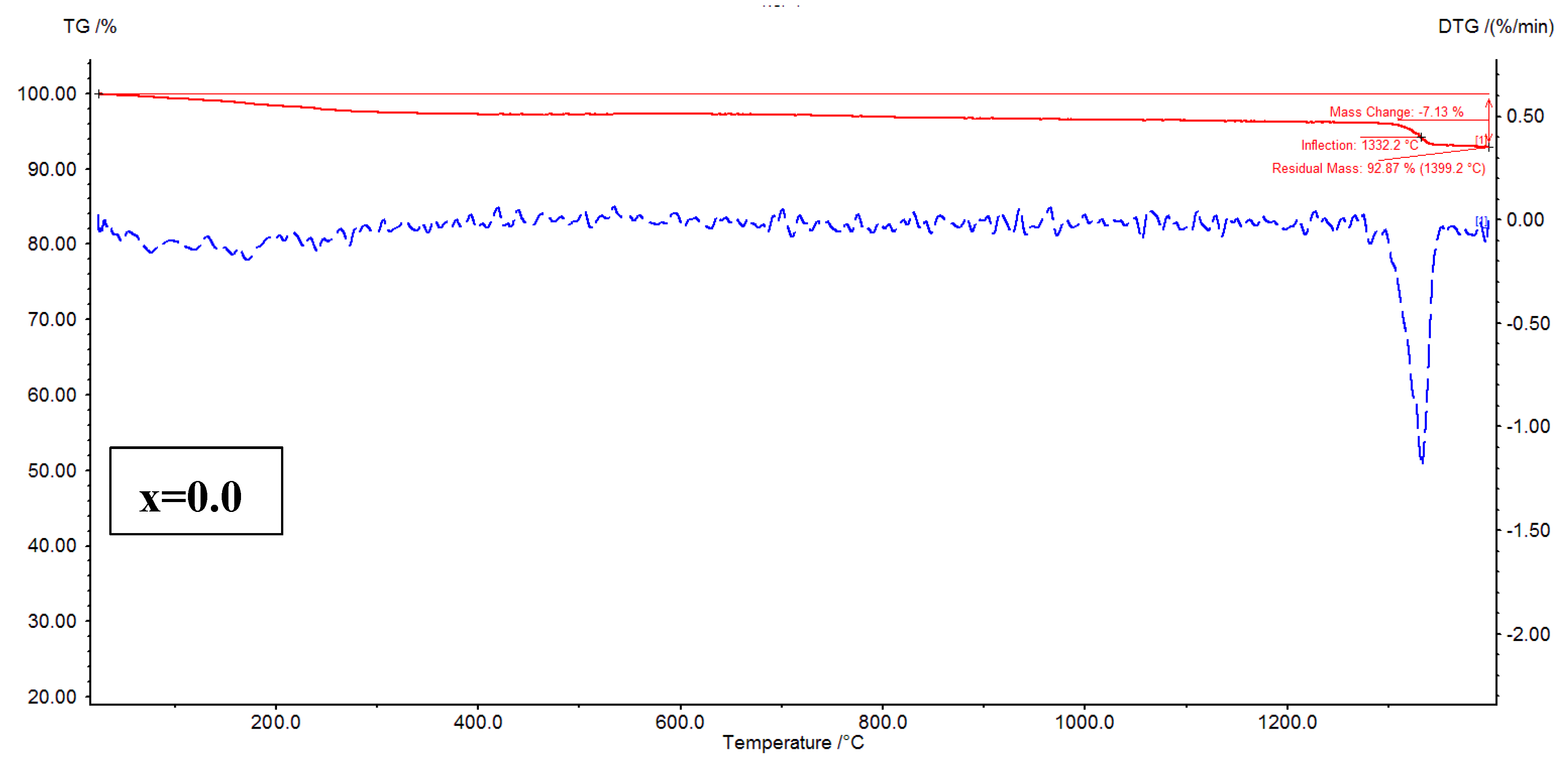

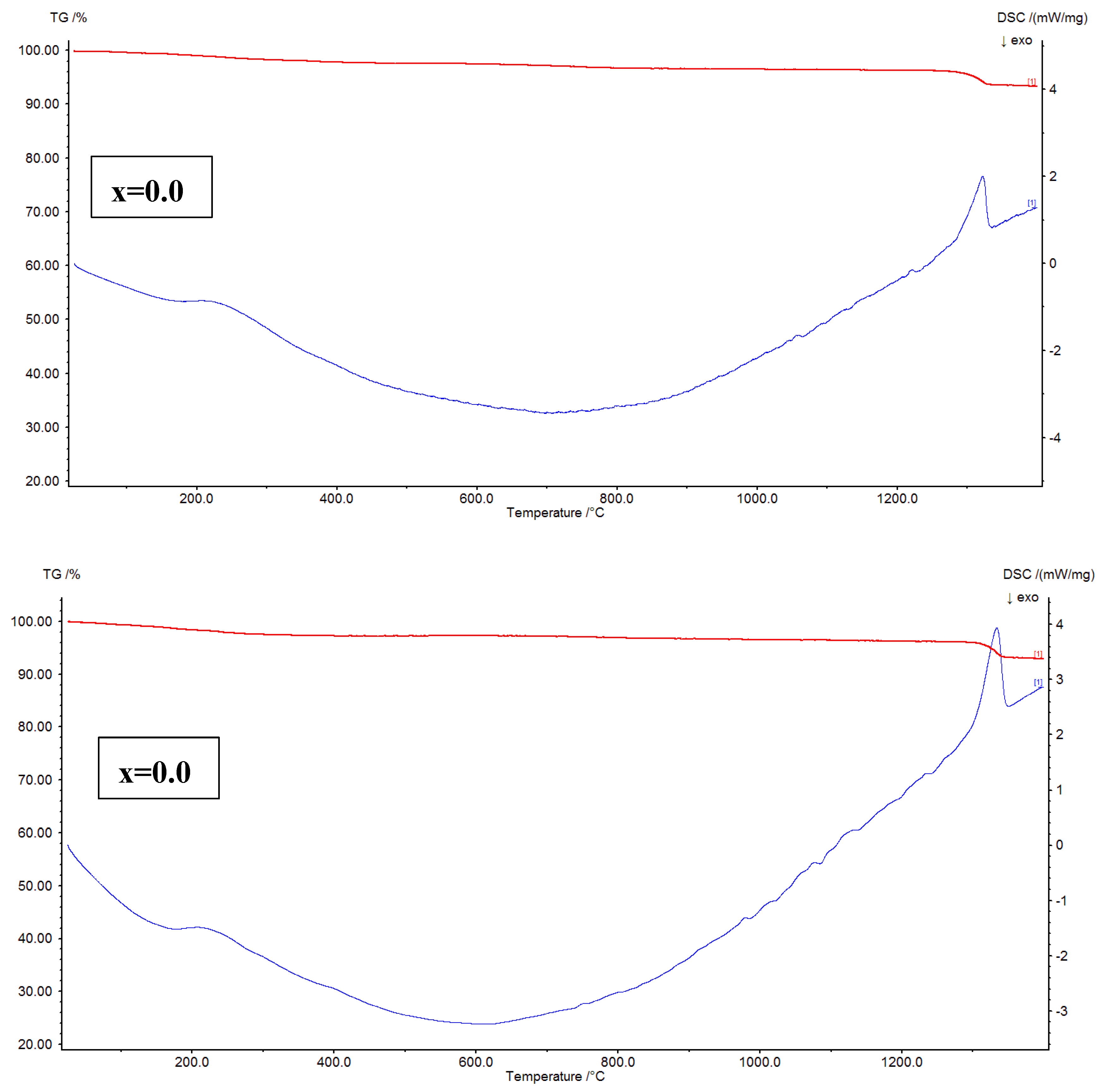

Figure 8 shows the TG-DSC plots of x=0.02-0.08. It is familiar that the TG-DSC curves represent the thermal transition temperatures such as glass transition (T

g), crystallization (T

c), and melting (T

m) temperatures. The grass transition temperatures are found to be decreased from 192 to 182 for x=0.02-0.04. For further increase of Gd-content, the T

g values are increased. This can be attributed to the ferri to paramagnetic transition. The variation trend of these temperatures is similar to the variation of crystallite size. Hence, it is confirmed that the crystallite size shows effect on thermal transition temperatures. After crossing T

g, the crystallization process will be initiated. Owing to this, beyond T

g, the atomic diffusion takes place, wherein, the atomic nuclei can be produced. Subsequently, the crystal grains are formed. Therefore, these crystal grains lead to the crystallization of samples at crystallization temperature. The T

c values of x=0.02-0.08 are found to be increasing from 910 to 1110

oC. From TG-DSC curves, endothermic or exothermic reaction can be understood for x=0.02-0.08. At crystallization temperatures, the energy is released owing to low free energy, and enthalpy. Hence, it comes under exothermic reaction suggesting the formation of Ni

1-xGd

xFe

2O

4 (x=0.02 – 0.08) compound. The endothermic peak temperatures (melting) are increased from 1310 to 1370

oC with increase in ‘x’ from 0.02-0.08. At these temperatures, the samples initiate absorbing heat, and shifts into the liquid form. Thus, these are connected to the endothermic reactions. Above the melting temperatures, the oxidation temperatures are considered for all nanoferrites.

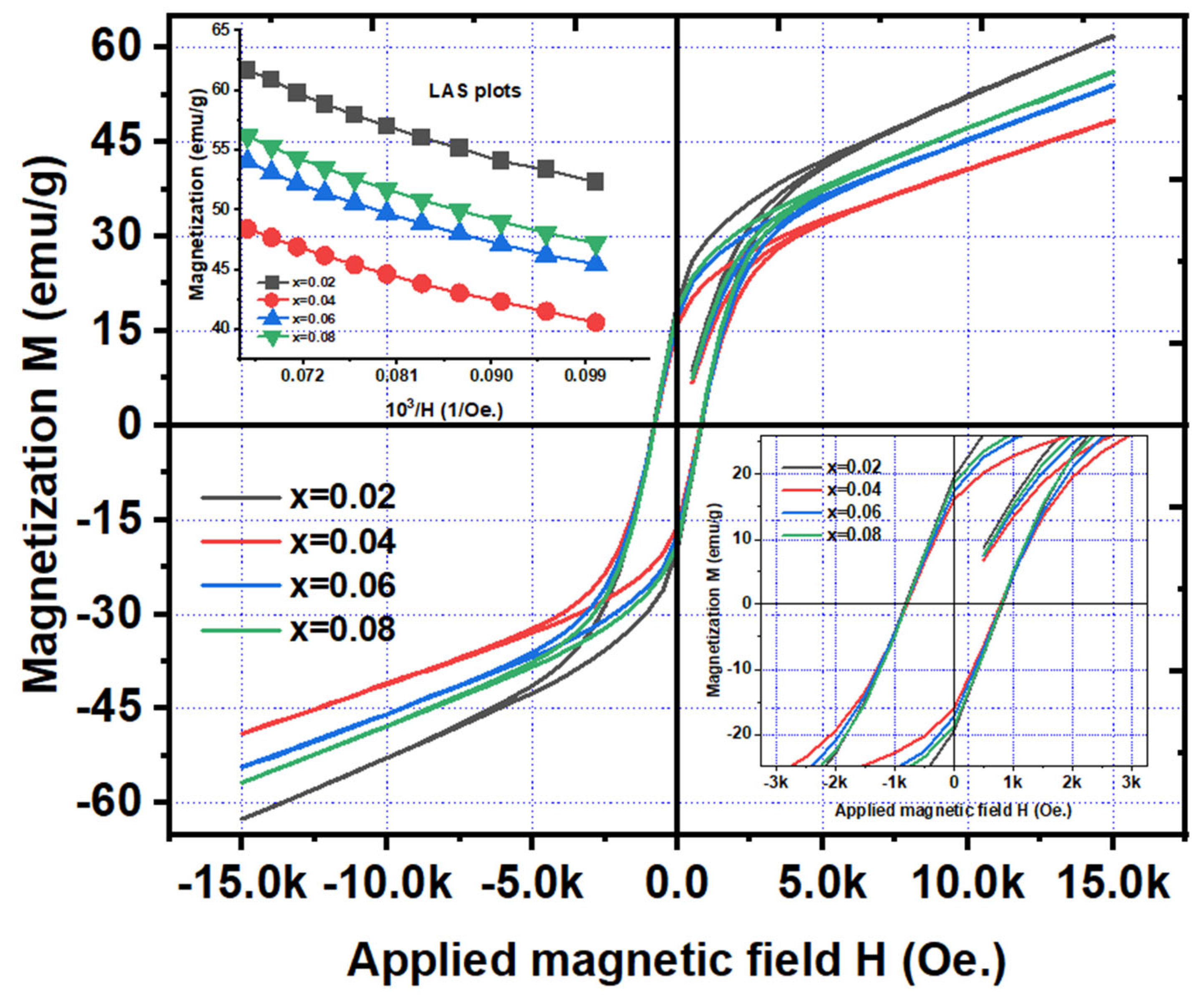

Figure 9 shows the magnetization versus applied magnetic field (M-H) curves of Ni

1-xGd

xFe

2O

4 (x=0.02 – 0.08) nanoparticles. It is observed that the well-define hysteresis curves are formed for x=0.02-0.08. Herein, the curves are not completely saturated suggesting the requirement of higher magnetic field than 15k Oe. However, the saturation magnetization (M

s) values are evaluated using the law of approach to saturation (LAS) plots (see the inset of

Figure 9). Therefore, the M

s values are extracted, and listed in

Table 3. The results indicate that the magnetization values are decreased from 62.1 to 49.1 emu/g (for x=0.02-0.04). For further increase of Gd-content, the magnetization is increased from 49.1 to 57.1 emu/g (for x=0.04-0.08). This trend is similar to the variation of crystallite size, and glass transition (magnetic transition) temperatures as a function of ‘x’. Similarly, the retentivity (M

r) is following the identical trend and found to be varying from 16.1 to 19.6 emu/g with Gd-content. The squareness (M

r/M

s) of x=0.02-0.08 shows that the values are altering between 0.316 to 0.328. It is a familiar fact that the M

r/M

s values <1/2 suggest the multi-domain magnetic structure while the similar values having >1/2 indicate the single-domain magnetic structure. But for the present NGF nanoparticles, it is noted that these values are less than ½. Hence, the magnetic structure of NGF samples is of multi-domain. The coercivity is observed to be varying between 789 to 824 Oe., as a function of ‘x’. High magnitude of anisotropy constant (K

1= H

cM

s/0.96) is noticed for all Gd-contents. It is attributed to the presence of Gd-element. Further, the magnetic moment n

B = M.W.*M

s/5585, is calculated [

26,

27,

28], and found to be altering between 2.095 to 2.627 μ

B/f.u., with increase in ‘x’. It is understood from the magnetization, and magnetic moment values of x=0.02-0.08 that the variation trend is similar. Joshi et al. [

15], reported the cation distribution of iron deficient NiGdFe

2O

4 indicating the Gd

3+ ions preferring the B-site. The Ni

2+ ions, ferric, and ferrous ions can occupy both the sites. From x=0.02-0.04, both the parameters are decreased owing the decrease of magnetic exchange interactions between two iron ions through oxygen (Fe-O-Fe) ions. For x=0.04-0.08, the similar interactions are increased leading to the increase of magnetic moment. The variation of superexchange interactions is mainly dependent of cation distribution with ‘x’. For this, the magnetic moments of cations are considered. Further, using Neel’s two sublattice model, the results magnetic moment is given by the subtraction of total magnetic moment of A-site from B-site (M

B-M

A). The cation distribution is provided in

Table 4. It indicates the preferential occupation of sites by the cations. According to this, the Gd

3+ ions first occupy the B-site, and therefore, the Ni

2+ will be migrated to A-site. As a result, the conversion of ferric to ferrous ions takes place predominantly. Thus, in the cation distribution, ferrous ion concentration is increased progressively. The observed coercivity is obtained due to the domain wall energy (ω

p), and critical diameter (D

c). Hence, ω

p=(2*K

B*T

c*K

1/a)

0.5 (where K

B is the Boltzmann constant in Kelvin, T

c is the Curie-transition temperature, and other symbols have their usual meaning), and D

c=1.4ω

p/M

s2 (symbols have their usual meaning) values are calculated for x=0.02-0.08 as listed in

Table 3. The crystallite size values, and critical diameter values are in almost same agreement. Hence, for all the samples, the achieved coercivity is due to domain wall rotation rather than domain wall displacement. The similar observations are found in literature [

2].

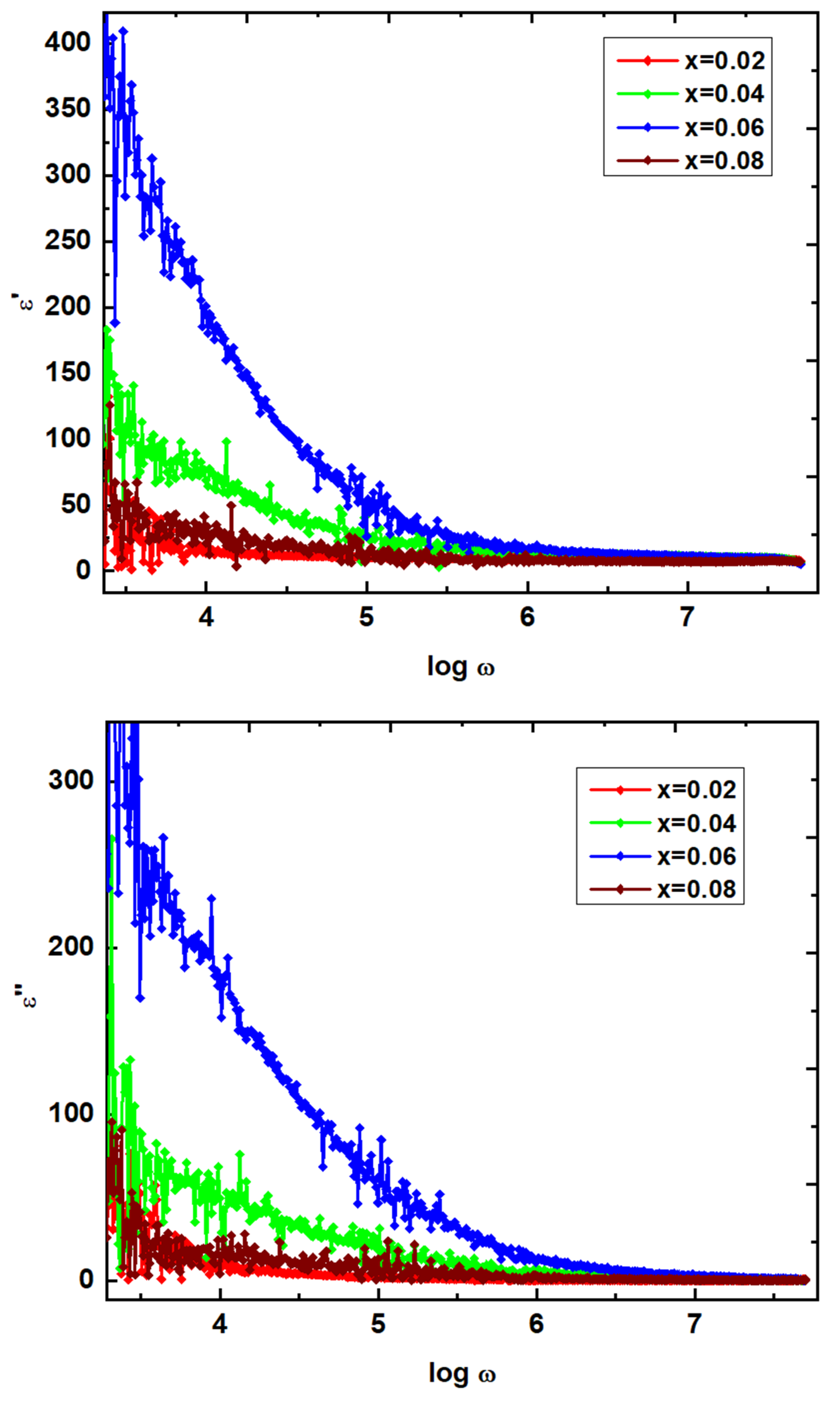

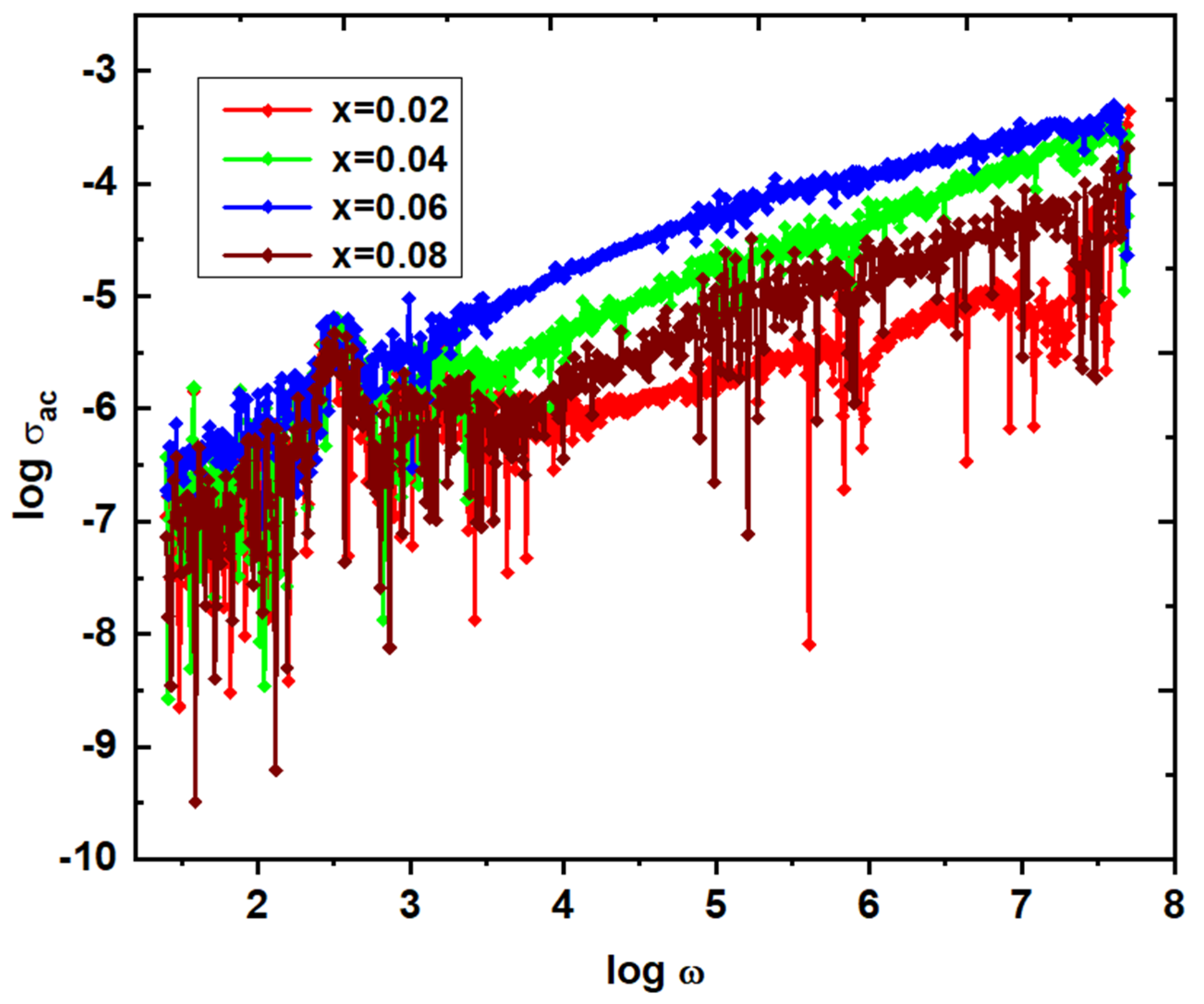

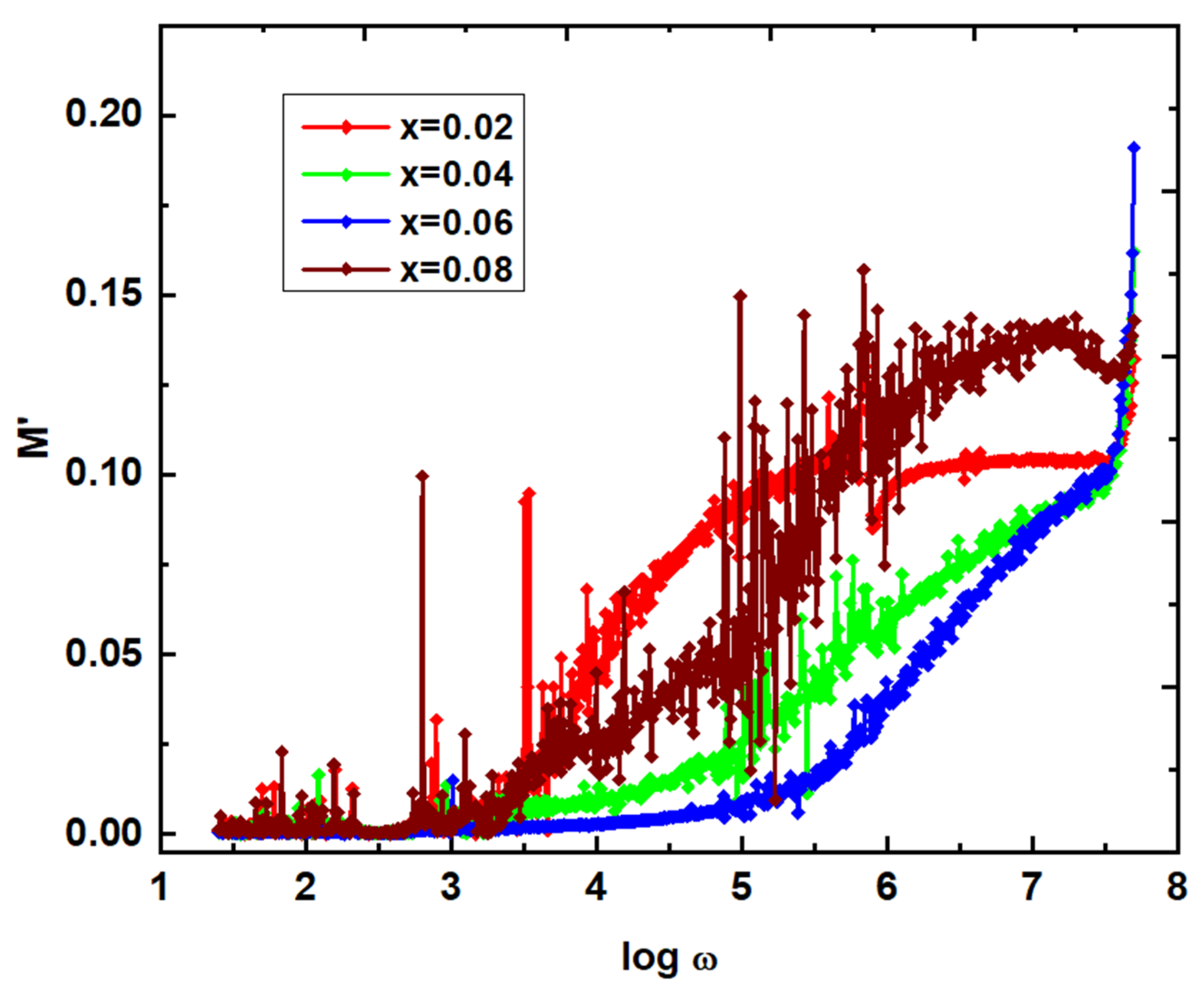

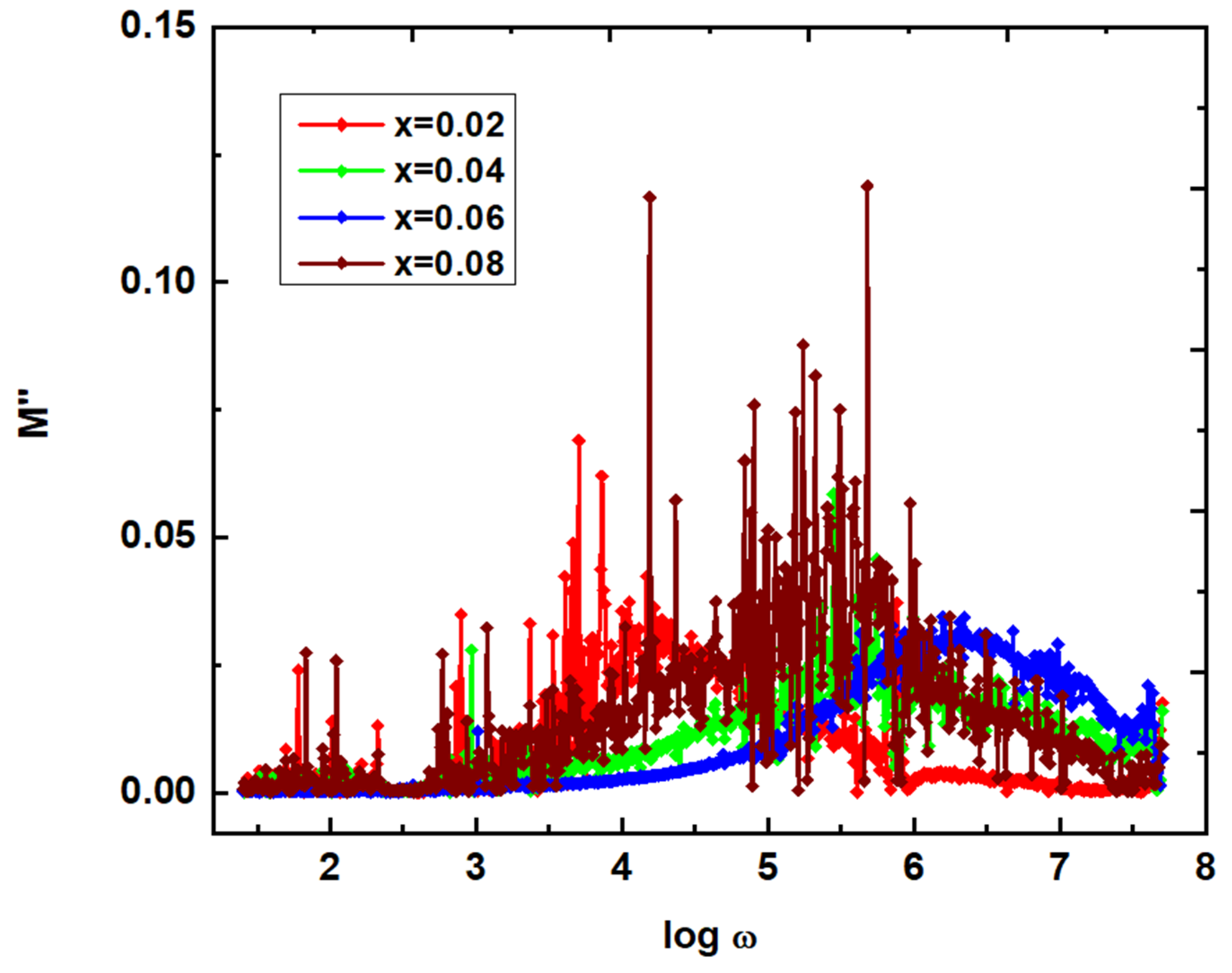

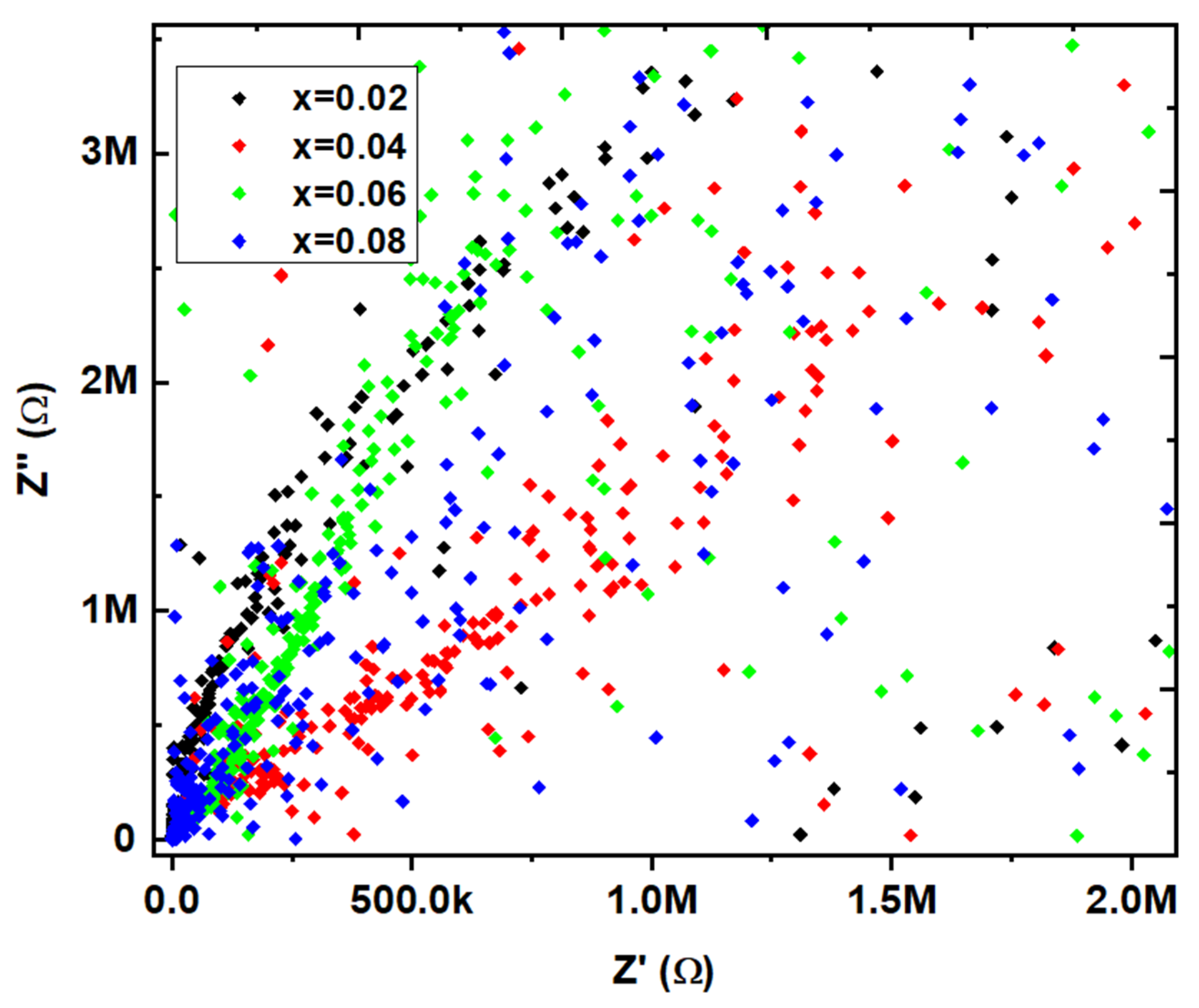

The dielectric behavior of Ni

1-xGd

xFe

2O

4 (x=0.02 – 0.08) nanoparticles is understood by studying the frequency dependence of dielectric constant (ɛ'), dielectric loss (ɛ"), and real & imaginary parts of dielectric modulus (M' & M"). It is evident from

Figure 10 that the ɛ', and ɛ" values are high in magnitude at 100 Hz. This behavior is due to inhomogeneous dielectric structure. In addition, the mechanism behind this can be well understood by Koop’s theory [

29]. It reveals the polycrystalline (NGF) materials pertain the grain, and grain boundaries which are considered as high resistive, and low resistive layers, respectively. At 100 Hz or even less than the similar frequency, the carriers will be piled at the grain boundary interface leading to the accumulation of carriers. This found effective at low frequencies of NGF samples. Hence, one can confirm that the high magnitude of ɛ', and ɛ" at low frequencies is attributed to the grain boundary’s effect. On the other hand, the magnitude of ɛ', and ɛ" comes down with increase in frequency, wherein the breakage of grain boundary interface takes place. Thus, the carriers enter the grain portion, wherein the conductivity is predominant. In the case of, NGF samples, the reduction in ɛ', and ɛ" suggested the breakage of grain boundary. In

Table 3, the ɛ', and ɛ" values of NGF are mentioned at 8 MHz. It is observed from these values that the x=0.06 content shows the high dielectric constant of 5.23, and low dielectric loss of 0.181. Moreover, the same composition offered high magnetization value of 54.5 emu/g, and low coercivity value indicate the composition suitable for microinductor applications. Further, the ac-electrical conductivity (σ

ac) is calculated using a formula: ɛ

oɛ"ω, and results at 8 MHz are reported in

Table 5. The log σ

ac ~ -4.092 suggests the low conductivity which is one of the required parameters for the microinductor devices. With increase of frequency, the conductivity of x=0.02-0.08 started increasing (see

Figure 11) owing to the thermal activation of charges at room temperature. Similarly, x=0.02 shows high ɛ'~7.44, and ɛ"~0.987, and hence the high conductivity is obtained. The real part of dielectric modulus (M'=ε'/(ε'

2+ε"

2)), and imaginary part of dielectric modulus (M"=ε"/(ε'

2+ε"

2)) are calculated, M' & and M" values (

Figure 12) are noted to be almost zero. This a common dielectric modulus behavior in case of any polycrystalline materials. It is attributed to the lack of restoring force to the carriers to reach the original positions. This is possible for carriers participating in long-range motion. The frequency dependent M" plots offered the relaxation at different frequencies. That is, x=0.02, 0.04, 0.06 & 0.08 at log ω=4.200, 5.611, 6.298 & 5.421, respectively. These results revealed that the relaxation frequency is increased from x=0.02-0.06, and beyond x=0.06, it is reduced. However, these relaxations usually provide two regions such as long-range (below relaxation), and short-range polarization mechanisms. In is clearly noticed that the plots of dielectric parameters, and conductivity show the scattering nature of data points. It is usually attributed to the presence of imperfections, and moisture in the samples. Moreover, these imperfections, and moisture can act as the scattering centres of charge carriers as indicated in the literature [

31]. Similarly, the Z' Vs. Z" plots are drawn (

Figure 13), and the trend of x=0.02-0.08 is not completely semicircle. It is established owing to the partial relaxation strength of carriers, wherein, the charges will go for long-range motion. However, it is remembered that the complete semicircle indicates the charges preferring the short-range motion. In this case, the charges will be confined to the potential well. Once the semicircles are imagined for Cole-Cole plots of x=0.02-0.08, the arcs pertain the centres lying below the real axis. Hence, it is confirmed that the relaxations are of non-Debye type.