Submitted:

19 December 2024

Posted:

06 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

This paper aims to develop a heading alignment procedure for drone navigation employing a single hover GNSS antenna combined with low-grade MEMs-IMU sensors. The design was motivated by the need for a drone-mounted differential interferometric SAR (DinSAR) application; however, the methodology proposed in this work can be applied to any Unmanned Aerial Vehicle (UAV) application that requires high-precision navigation data for short-flight missions utilizing cost-effective MEMS sensors. The method proposed here involves a Bayesian parameter estimation based on a simultaneous cumulative Mahalonobis metric applied to the innovation process of Kalman-like filters, which are identical except for the initial heading guess. The procedure is then generalized and called parametric alignment. The motivation for the multidimensional extension in the scenario is also presented. The method is highly applicable for cases where gyro-compassing is not available, usually for low-cost UAV applications. It employs the most straightforward optimization techniques that can be implemented using a real-time parallelism scheme. Numeric simulations and experimental evaluations using a real UAV demonstrate that the proposed method can provide initial heading alignment when the heading is not directly observable during takeoff.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Inertial Navigation System for Drones

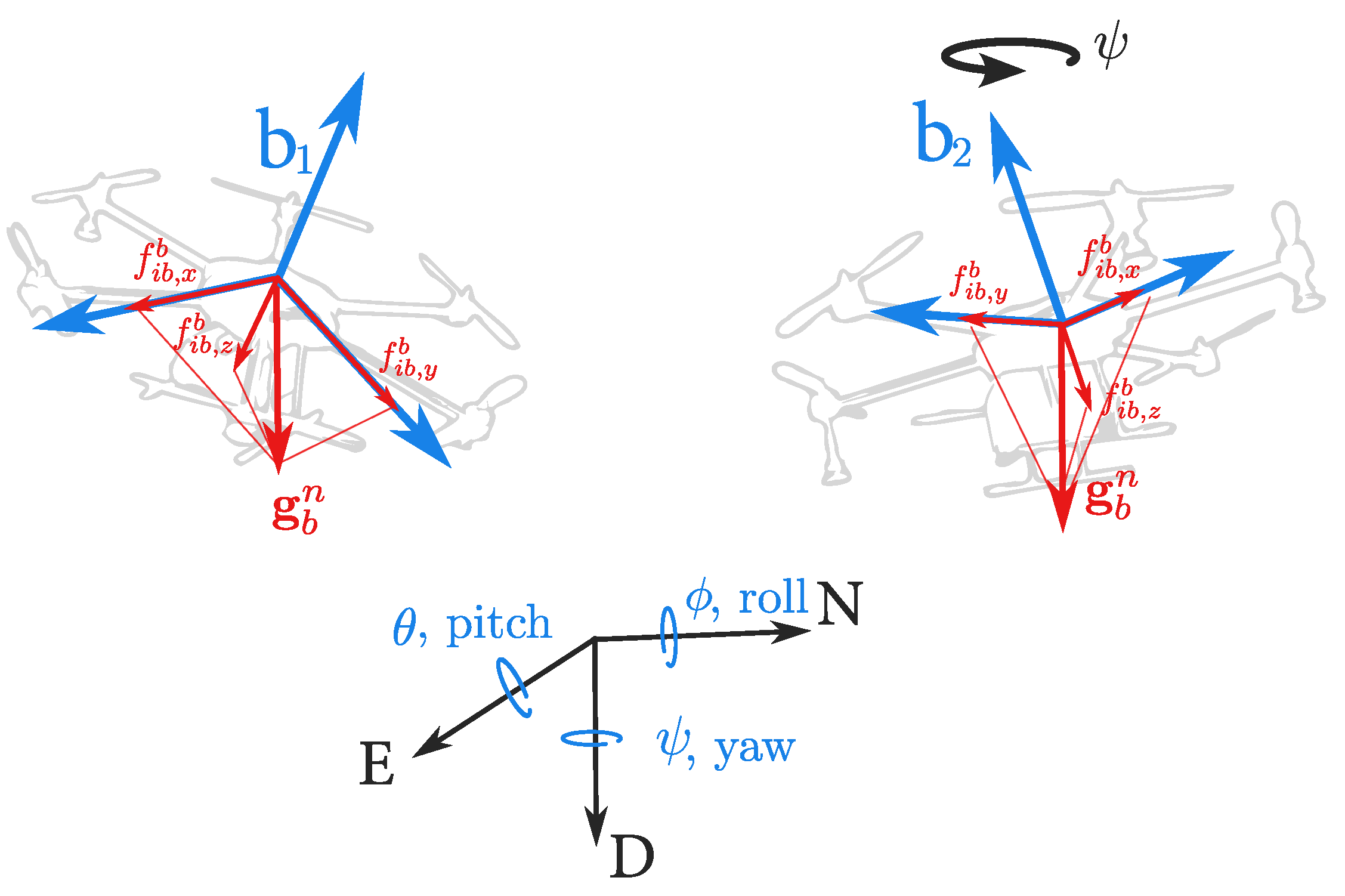

2.1. Dynamic and Measurement Models

2.2. Coarse Alignment: Pitch and Roll Angles

2.3. The Kalman Filter and its Role in Qualifying Parameters

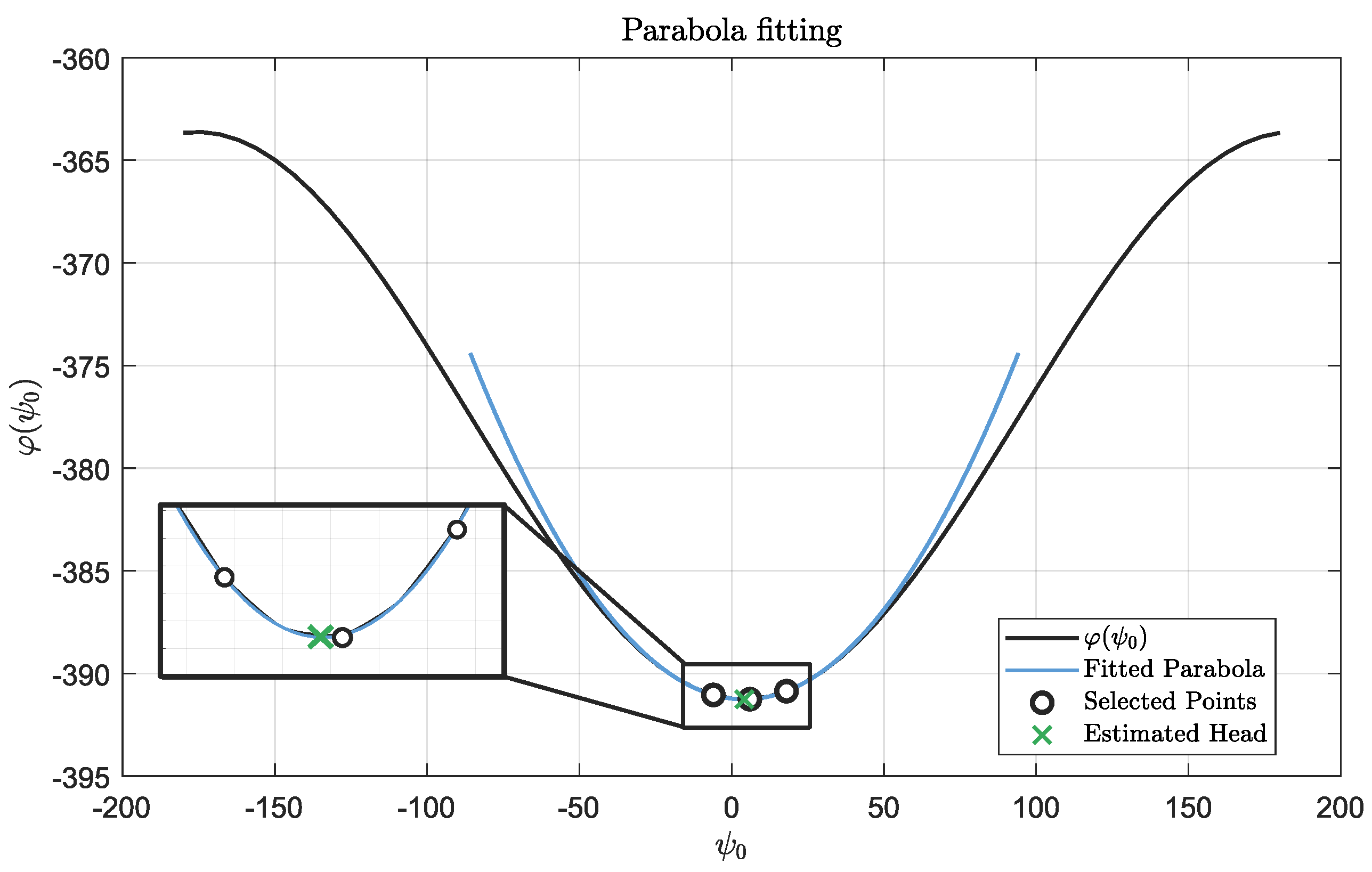

2.4. Unidimensional Quadratic Fit

3. Heading Alignment for UAV

3.1. Post-Mission Heading Alignment

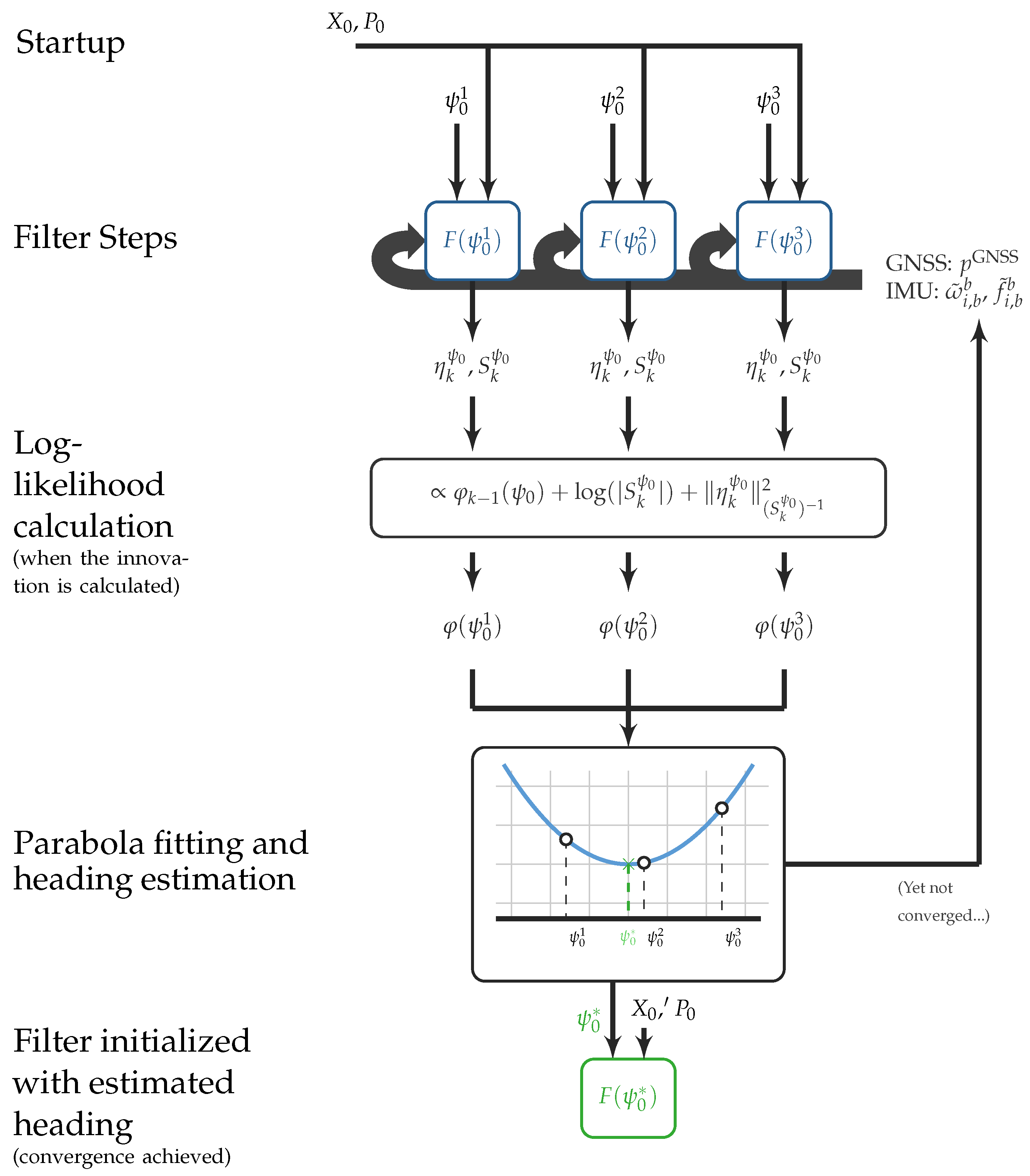

3.2. Real-Time Heading Aligment

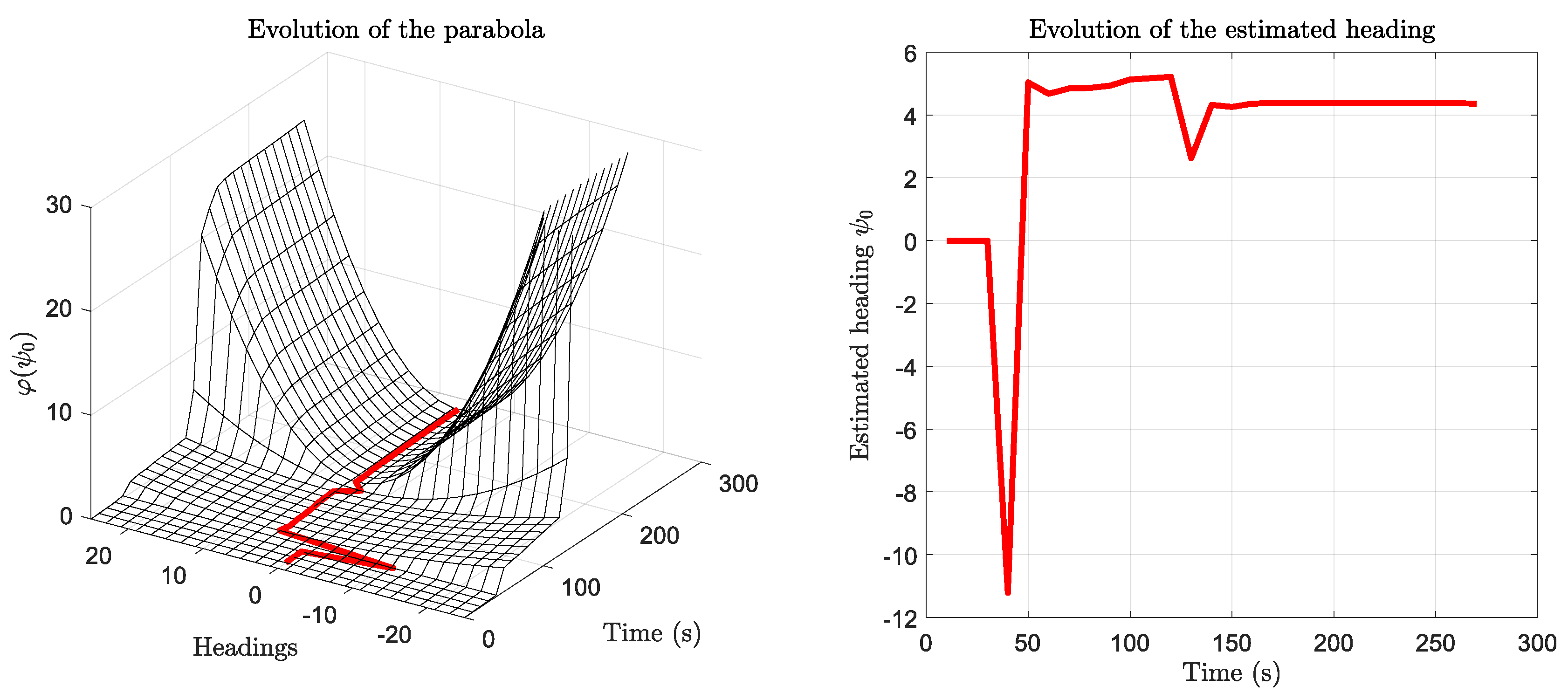

- Initialize a set of three filters , each parameterized by an initial heading otherwise equal initial conditions. The central value of would carry a rough estimate of the initial heading;

- Acquire streaming data from the GNSS and the IMU. Note that these are obtained at different sampling rates;

- Feed the independent filters with the measurements, executing the prediction step, Equation (6a), at the accelerometer/gyroscope sampling rate, and the update step, Equation (6d), at the GNSS sampling rate;

- During update step, compute for each filter the k-th term of the sum in Equation (12).

- Using the three values of , parameterize a parabola and find its minimum, representing an estimate of the initial heading .

- Finally, create a new filter initialized with the best initial heading estimate and fed the data collected so far.

3.3. Heading Alignment Performance Evaluation

4. Extension to Multidimensional Alignments

4.1. Multidimensional alignment

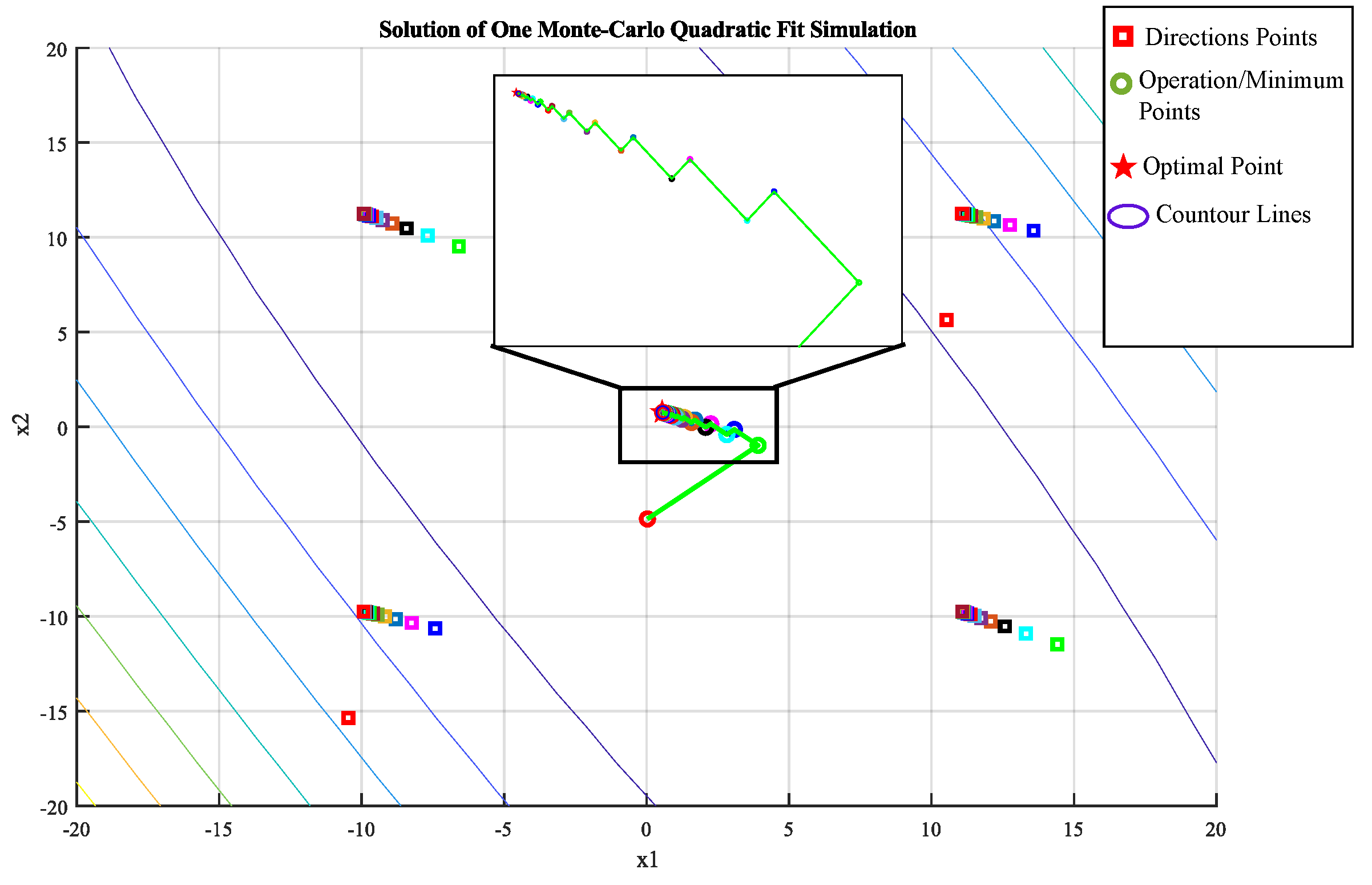

4.2. Quadratic Fit: Multidimensional Extension

4.3. The Minimizing Algorithm

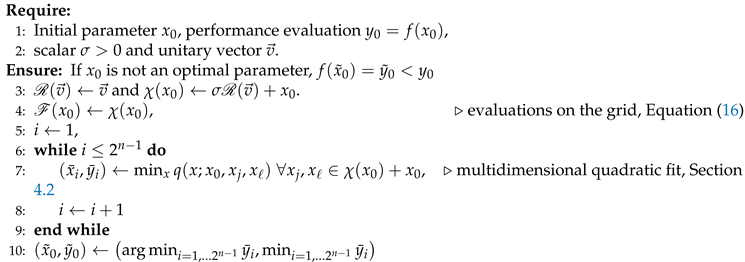

| Algorithm 1 A complete step of sigma-point evaluations |

|

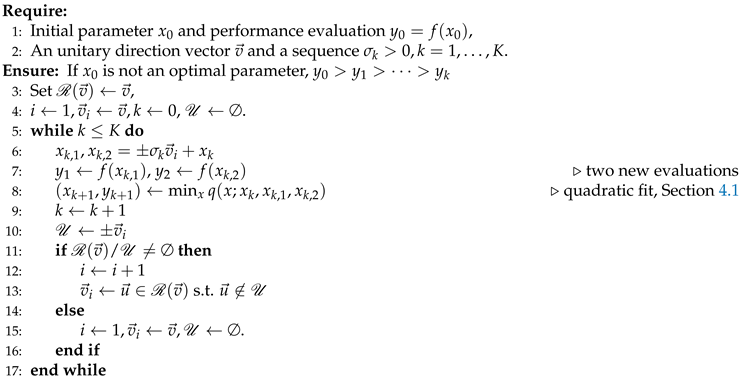

| Algorithm 2 A stepwise decreasing algorithm |

|

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PVA | Position, Velocity and Attitude |

| KF | Kalman Filter |

| IMU | Inertial Measurement Unit |

| INS | Inertial Navigation System |

| GNSS | Global Navigation Satellite System |

| MAP | Maximum a Posteriori |

| MMS | Minimum Mean Square |

References

- Gade, K. The Seven Ways to Find Heading. Journal of Navigation 2016, 69, 955–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, M.R.; Magalhães, G.M.; Zúñiga, Y.R.C.; do Val, J.B.R. GNSS/MEMS-INS Integration for Drone Navigation Using EKF on Lie Groups. IEEE Transactions on Aerospace and Electronic Systems 2023, 59, 7395–7408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groves, P.D. Principles of GNSS, Inertial, and Multisensor Integrated Navigation Systems; Artech House, 2013.

- Titterton, D.; Weston, J. Strapdown Inertial Navigation Technology, 2nd ed.; The Institution of Electrical Engineers, 2004.

- Rogers, R.M. Applied Mathematics in Integrated Navigation Systems, 2nd ed.; American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics, Inc., 2003.

- Goel, A.; Aseem, S.; Islam, U.L.; Ansari, A.; Kouba, O.; Bernstein, D.S. An Introduction to Inertial Navigation From the Perspective of State Estimation. IEEE Contr Syst Mag 2021, 45. [Google Scholar]

- Bar-Shalom, Y.; Li, X.R.; Kirubarajan, T. Estimation with Applications to Tracking and Navigation; Wiley-Interscience, 2001; p. 584.

- Blackman, S.; Popoli, R. Design and Analysis of Modern Tracking Systems; Artech House Publishers, 1999; p. 1230.

- Streit, R.; Angle, R.B.; Efe, M. Analytic Combinatorics for Multiple Object Tracking; Springer International Publishing AG, 2020.

- Blom, H.; Bar-Shalom, Y. The interacting multiple model algorithm for systems with Markovian switching coefficients. IEEE Transactions on Automatic Control 1988, 33, 780–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ristic, B.; Arulampalam, S.; Gordon, N. Beyond the Kalman Filter; Artech House Publishers, 2004; p. 318.

- Chopin, N.; Papaspiliopoulos, O. An Introduction to Sequential Monte Carlo; Springer, 2020; p. 350.

- Bourmaud, G.; Mégret, R.; Giremus, A.; Berthoumieu, Y. Discrete extended Kalman filter on Lie groups. In Proceedings of the 21st EUSIPCO, Marrakech, Morocco, 2013.

- Bourmaud, G.; Mégret, R.; Giremus, A.; Berthoumieu, Y. From Intrinsic Optimization to Iterated Extended Kalman Filtering on Lie Groups. J Math Imaging Vis 2016, 55, 284–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luenberger, D.G. Introduction to linear and nonlinear programming; Addison-Wesley: Reading, Mass., 1973.

- Särkkä, S. Bayesian filtering and smoothing, second edition ed.; Number 17 in Institute of Mathematical Statistics textbooks, Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 2023.

| 1 | Or, for that matter, to the derivatives in general, which may or may not exist. |

| 2 | The vector notation is used here to facilitate the understanding. |

| Number of Iterations | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean Gain (%) | K = 1 | K = 5 | K = 50 | K = 100 | K = 500 |

| 69.43 | 92.27 | 99.91 | 99.98 | 100 | |

| 27.89 | 78.33 | 98.77 | 99.58 | 99.99 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).