Submitted:

05 January 2025

Posted:

06 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

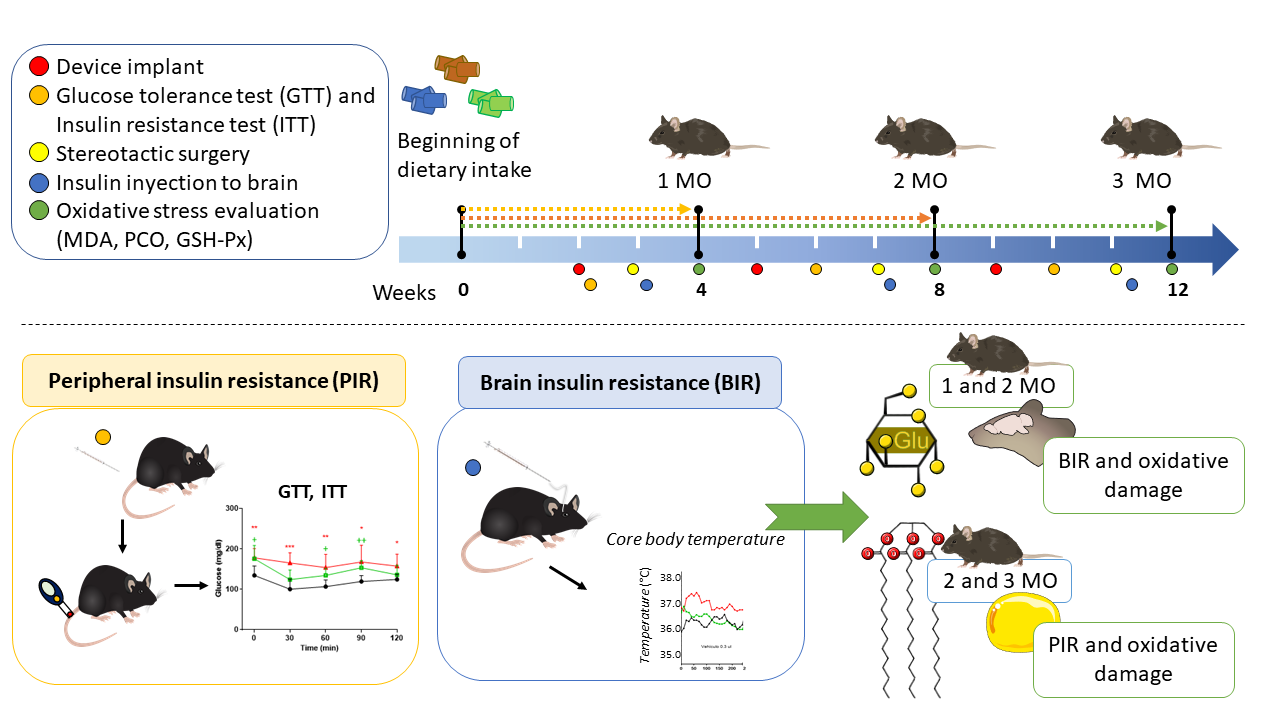

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals and Group Assignment

2.2. Evaluation of the Peripheral Insulin Resistance

2.3. Evaluation of Brain Insulin Resistance

2.4. Sacrifice and Tissue Sampling

2.5. Glutathione Peroxidase (GSH-Px) Activity

2.6. Malondialdehyde (MDA) Concentration

2.7. Determination of Protein Carbonyl Group (PCO)

2.8. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

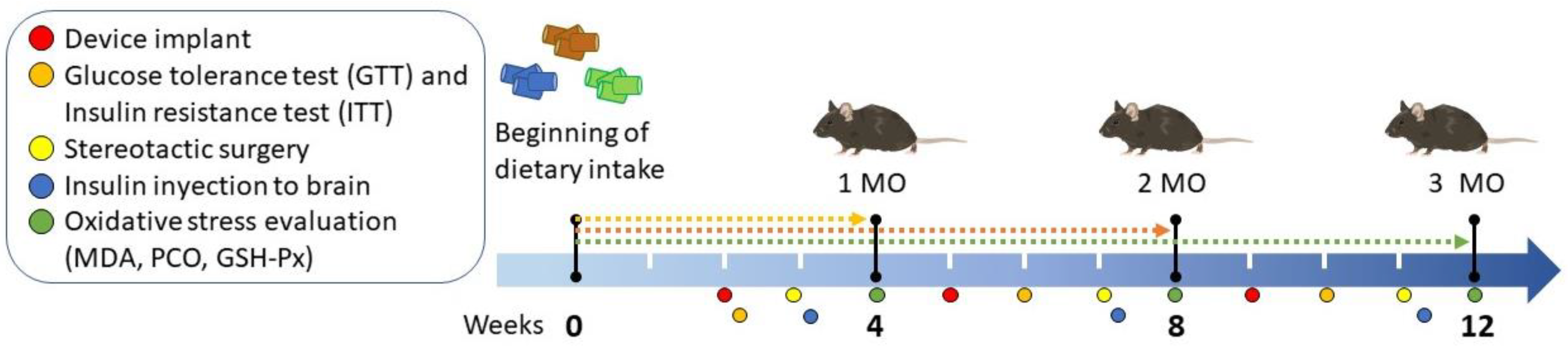

3.1. Obesity Induction by HFD

3.2. HFD Causes Glucose Intolerance in C57BL/6 Mice Starting from the First Month of this Diet

3.3. Peripheral Insulin Resistance is Established in C57BL/6 Mice fed HFD up to the Third Month of Administration

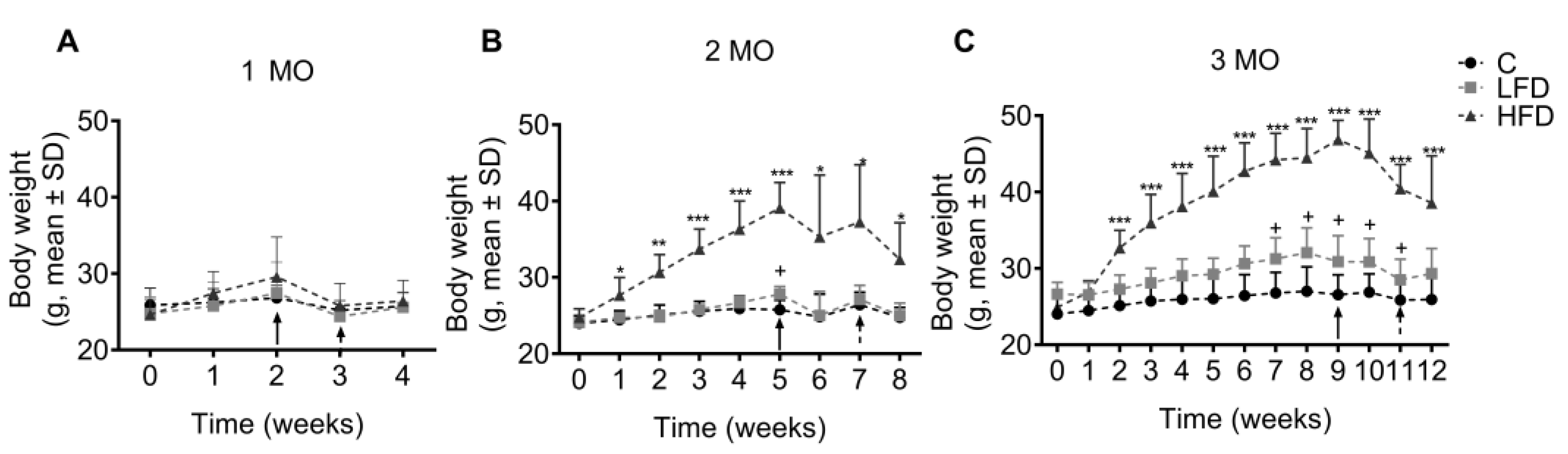

3.4. LFD Diet Promotes BIR in the First Two Months of Exposure

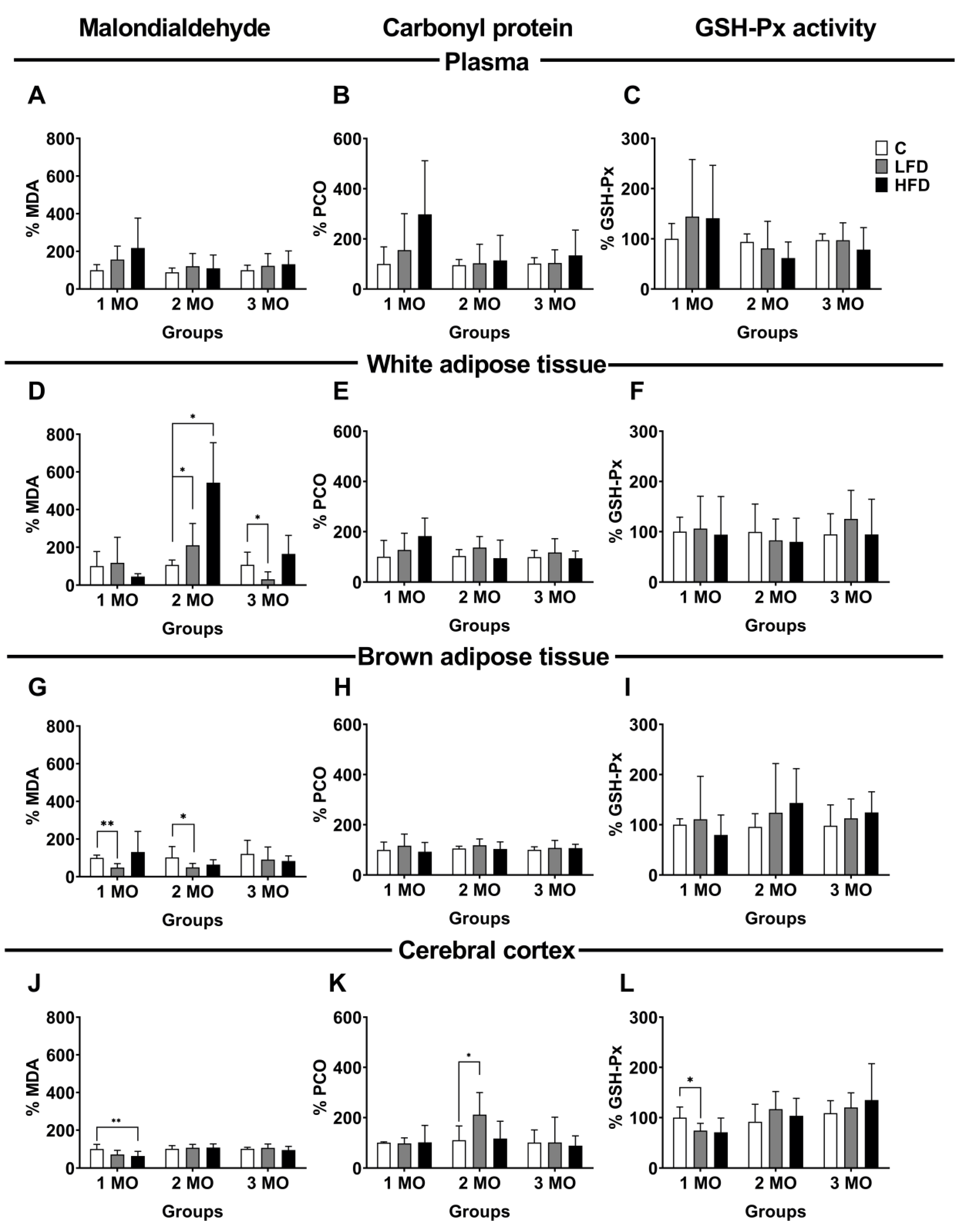

3.5. Oxidative Damage of Lipids, Proteins, and Enzymatic Activity in Plasma

3.6. Oxidative Damage of Lipids and Proteins and Enzymatic Activity in White Adipose Tissue

3.7. Oxidative Lipid and Protein Damage and Enzymatic Activity in Brown Adipose Tissue

3.8. Oxidative Damage of Lipids and Proteins and Enzymatic Activity in the Cerebral Cortex

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Institutional Review Board Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BIR | Brain insulin resistance |

| C | Control |

| CAT | Catalase |

| FFA | Free fatty acids |

| GLUT | Glucose transporter |

| GSH-Px | Glutathione peroxidase |

| GST | Glutathione S-transferase |

| GTT | Oral glucose tolerance test |

| HFD | High fat diet |

| IR | Insulin receptor |

| IRS | Insulin receptor substrate |

| ITT | Insulin tolerance test |

| LFD | Low fat diet |

| MDA | Malondialdehyde |

| MPI | 1-methyl-2-phenylindole |

| NADPH | Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate |

| PBS | Phosphate buffer solution |

| PCO | Carbonylated proteins |

| PIR | Peripherical insulin resistance |

| POA | Preoptic area |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| SOD | Superoxide dismutase |

| SP | Sodium pentobarbital |

| UCP1 | Uncoupling protein-1 |

References

- Osborn, O.; Olefsky, J.M. The Cellular and Signaling Networks Linking the Immune System and Metabolism in Disease. Nat Med 2012, 18, 363–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil, A.; Olza, J.; Gil-Campos, M.; Gomez-Llorente, C.; Aguilera, C.M. Is Adipose Tissue Metabolically Different at Different Sites? Int J Pediatr Obes 2011, 6, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, F.; Zhang, Z.; Bai, Y.; Che, Q.; Cao, H.; Guo, J.; Su, Z. Glucosamine Improves Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease Induced by High-Fat and High-Sugar Diet through Regulating Intestinal Barrier Function, Liver Inflammation, and Lipid Metabolism. Molecules 2023, 28, 6918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lagathu, C.; Yvan-Charvet, L.; Bastard, J.-P.; Maachi, M.; Quignard-Boulangé, A.; Capeau, J.; Caron, M. Long-Term Treatment with Interleukin-1β Induces Insulin Resistance in Murine and Human Adipocytes. Diabetologia 2006, 49, 2162–2173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elkanawati, R.; Sumiwi, S.; Levita, J. Impact of Lipids on Insulin Resistance: Insights from Human and Animal Studies. DDDT 2024, 18, 3337–3360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jung, S.-B.; Choi, M.J.; Ryu, D.; Yi, H.-S.; Lee, S.E.; Chang, J.Y.; Chung, H.K.; Kim, Y.K.; Kang, S.G.; Lee, J.H.; et al. Reduced Oxidative Capacity in Macrophages Results in Systemic Insulin Resistance. Nat Commun 2018, 9, 1551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurrle, S.; Hsu, W.H. The Etiology of Oxidative Stress in Insulin Resistance. Biomedical Journal 2017, 40, 257–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Mello, A.H.; Costa, A.B.; Engel, J.D.G.; Rezin, G.T. Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Obesity. Life Sciences 2018, 192, 26–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayala, A.; Muñoz, M.F.; Argüelles, S. Lipid Peroxidation: Production, Metabolism, and Signaling Mechanisms of Malondialdehyde and 4-Hydroxy-2-Nonenal. Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity 2014, 2014, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frijhoff, J.; Winyard, P.G.; Zarkovic, N.; Davies, S.S.; Stocker, R.; Cheng, D.; Knight, A.R.; Taylor, E.L.; Oettrich, J.; Ruskovska, T.; et al. Clinical Relevance of Biomarkers of Oxidative Stress. Antioxidants & Redox Signaling 2015, 23, 1144–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonos, E.S.; Kapetanou, M.; Sereikaite, J.; Bartosz, G.; Naparło, K.; Grzesik, M.; Sadowska-Bartosz, I. Origin and Pathophysiology of Protein Carbonylation, Nitration and Chlorination in Age-Related Brain Diseases and Aging. Aging 2018, 10, 868–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkins, C.L.; Davies, M.J. Detection, Identification, and Quantification of Oxidative Protein Modifications. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2019, 294, 19683–19708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morales, M.; Munné-Bosch, S. Malondialdehyde: Facts and Artifacts. Plant Physiol. 2019, 180, 1246–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jomova, K.; Raptova, R.; Alomar, S.Y.; Alwasel, S.H.; Nepovimova, E.; Kuca, K.; Valko, M. Reactive Oxygen Species, Toxicity, Oxidative Stress, and Antioxidants: Chronic Diseases and Aging. Arch Toxicol 2023, 97, 2499–2574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauterbach, M.A.R.; Wunderlich, F.T. Macrophage Function in Obesity-Induced Inflammation and Insulin Resistance. Pflugers Arch - Eur J Physiol 2017, 469, 385–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, F.; Pham, M.; Luttrell, I.; Bannerman, D.D.; Tupper, J.; Thaler, J.; Hawn, T.R.; Raines, E.W.; Schwartz, M.W. Toll-Like Receptor-4 Mediates Vascular Inflammation and Insulin Resistance in Diet-Induced Obesity. Circulation Research 2007, 100, 1589–1596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onyango, A.N. Cellular Stresses and Stress Responses in the Pathogenesis of Insulin Resistance. Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity 2018, 2018, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itani, S.I.; Ruderman, N.B.; Schmieder, F.; Boden, G. Lipid-Induced Insulin Resistance in Human Muscle Is Associated With Changes in Diacylglycerol, Protein Kinase C, and IκB-α. Diabetes 2002, 51, 2005–2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petersen, M.C.; Shulman, G.I. Mechanisms of Insulin Action and Insulin Resistance. Physiological Reviews 2018, 98, 2133–2223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, B.-C.; Lee, J. Cellular and Molecular Players in Adipose Tissue Inflammation in the Development of Obesity-Induced Insulin Resistance. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular Basis of Disease 2014, 1842, 446–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morigny, P.; Boucher, J.; Arner, P.; Langin, D. Lipid and Glucose Metabolism in White Adipocytes: Pathways, Dysfunction and Therapeutics. Nat Rev Endocrinol 2021, 17, 276–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christie, J.M.; Wenthold, R.J.; Monaghan, D.T. Insulin Causes a Transient Tyrosine Phosphorylation of NR2A and NR2B NMDA Receptor Subunits in Rat Hippocampus. Journal of Neurochemistry 1999, 72, 1523–1528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skeberdis, V.A.; Lan, J.; Zheng, X.; Zukin, R.S.; Bennett, M.V.L. Insulin Promotes Rapid Delivery of N -Methyl- d - Aspartate Receptors to the Cell Surface by Exocytosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2001, 98, 3561–3566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Lee, C.; Hsu, K. An Investigation into Signal Transduction Mechanisms Involved in Insulin-induced Long-term Depression in the CA1 Region of the Hippocampus. Journal of Neurochemistry 2004, 89, 217–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Der Heide, L.P.; Kamal, A.; Artola, A.; Gispen, W.H.; Ramakers, G.M.J. Insulin Modulates Hippocampal Activity-dependent Synaptic Plasticity in a N -methyl- d -aspartate Receptor and Phosphatidyl-inositol-3-kinase-dependent Manner. Journal of Neurochemistry 2005, 94, 1158–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Alavez, M.; Tabarean, I.V.; Osborn, O.; Mitsukawa, K.; Schaefer, J.; Dubins, J.; Holmberg, K.H.; Klein, I.; Klaus, J.; Gomez, L.F.; et al. Insulin Causes Hyperthermia by Direct Inhibition of Warm-Sensitive Neurons. Diabetes 2010, 59, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boucher, J.; Kleinridders, A.; Kahn, C.R. Insulin Receptor Signaling in Normal and Insulin-Resistant States. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology 2014, 6, a009191–a009191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhtar, A.; Sah, S.P. Insulin Signaling Pathway and Related Molecules: Role in Neurodegeneration and Alzheimer’s Disease. Neurochemistry International 2020, 135, 104707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arnold, S.E.; Arvanitakis, Z.; Macauley-Rambach, S.L.; Koenig, A.M.; Wang, H.-Y.; Ahima, R.S.; Craft, S.; Gandy, S.; Buettner, C.; Stoeckel, L.E.; et al. Brain Insulin Resistance in Type 2 Diabetes and Alzheimer Disease: Concepts and Conundrums. Nat Rev Neurol 2018, 14, 168–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kellar, D.; Craft, S. Brain Insulin Resistance in Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Disorders: Mechanisms and Therapeutic Approaches. The Lancet Neurology 2020, 19, 758–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuzawa-Nagata, N.; Takamura, T.; Ando, H.; Nakamura, S.; Kurita, S.; Misu, H.; Ota, T.; Yokoyama, M.; Honda, M.; Miyamoto, K.; et al. Increased Oxidative Stress Precedes the Onset of High-Fat Diet–Induced Insulin Resistance and Obesity. Metabolism 2008, 57, 1071–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pieri, B.L.D.S.; Rodrigues, M.S.; Farias, H.R.; Silveira, G.D.B.; Ribeiro, V.D.S.G.D.C.; Silveira, P.C.L.; De Souza, C.T. Role of Oxidative Stress on Insulin Resistance in Diet-Induced Obesity Mice. IJMS 2023, 24, 12088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carillon, J.; Romain, C.; Bardy, G.; Fouret, G.; Feillet-Coudray, C.; Gaillet, S.; Lacan, D.; Cristol, J.-P.; Rouanet, J.-M. Cafeteria Diet Induces Obesity and Insulin Resistance Associated with Oxidative Stress but Not with Inflammation: Improvement by Dietary Supplementation with a Melon Superoxide Dismutase. Free Radical Biology and Medicine 2013, 65, 254–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maciejczyk, M.; Żebrowska, E.; Zalewska, A.; Chabowski, A. Redox Balance, Antioxidant Defense, and Oxidative Damage in the Hypothalamus and Cerebral Cortex of Rats with High Fat Diet-Induced Insulin Resistance. Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity 2018, 2018, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodur, A.; İnce, İ.; Kahraman, C.; Abidin, İ.; Aydin-Abidin, S.; Alver, A. Effect of a High Sucrose and High Fat Diet in BDNF (+/-) Mice on Oxidative Stress Markers in Adipose Tissues. Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics 2019, 665, 46–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcalá, M.; Calderon-Dominguez, M.; Bustos, E.; Ramos, P.; Casals, N.; Serra, D.; Viana, M.; Herrero, L. Increased Inflammation, Oxidative Stress and Mitochondrial Respiration in Brown Adipose Tissue from Obese Mice. Sci Rep 2017, 7, 16082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mazzoli, A.; Spagnuolo, M.S.; Nazzaro, M.; Gatto, C.; Iossa, S.; Cigliano, L. Fructose Removal from the Diet Reverses Inflammation, Mitochondrial Dysfunction, and Oxidative Stress in Hippocampus. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Żebrowska, E.; Chabowski, A.; Zalewska, A.; Maciejczyk, M. High-Sugar Diet Disrupts Hypothalamic but Not Cerebral Cortex Redox Homeostasis. Nutrients 2020, 12, 3181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, Z.; Zhang, X.; Sun, Q.; Liu, Y.; Liao, N.; Wu, H.; Wang, X.; Hai, C. Evolution of Metabolic Disorder in Rats Fed High Sucrose or High Fat Diet: Focus on Redox State and Mitochondrial Function. General and Comparative Endocrinology 2017, 242, 92–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesquita, C.S.; Oliveira, R.; Bento, F.; Geraldo, D.; Rodrigues, J.V.; Marcos, J.C. Simplified 2,4-Dinitrophenylhydrazine Spectrophotometric Assay for Quantification of Carbonyls in Oxidized Proteins. Analytical Biochemistry 2014, 458, 69–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, A.T.C.; Francisqueti, F.V.; Hasimoto, F.K.; Ferraz, A.P.C.R.; Minatel, I.O.; Garcia, J.L.; Dos Santos, K.C.; Alves, P.H.R.; Lima, G.P.P.; Moreto, F.; et al. Brazilian Curcuma Longa L. Attenuates Comorbidities by Modulating Adipose Tissue Dysfunction in Obese Rats. Nutrire 2018, 43, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, T.; Fang, B.; Wu, F.; Liu, Y.; Cheng, L.; Li, Y.; Wang, R.; Zhu, L. Diet Change Improves Obesity and Lipid Deposition in High-Fat Diet-Induced Mice. Nutrients 2023, 15, 4978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Małodobra-Mazur, M.; Cierzniak, A.; Pawełka, D.; Kaliszewski, K.; Rudnicki, J.; Dobosz, T. Metabolic Differences between Subcutaneous and Visceral Adipocytes Differentiated with an Excess of Saturated and Monounsaturated Fatty Acids. Genes 2020, 11, 1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casimiro, I.; Stull, N.D.; Tersey, S.A.; Mirmira, R.G. Phenotypic Sexual Dimorphism in Response to Dietary Fat Manipulation in C57BL/6J Mice. Journal of Diabetes and its Complications 2021, 35, 107795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shetty, S.; Duesman, S.J.; Patel, S.; Huynh, P.; Toh, P.; Shroff, S.; Das, A.; Chowhan, D.; Keller, B.; Alvarez, J.; et al. Sex-Specific Role of High-Fat Diet and Stress on Behavior, Energy Metabolism, and the Ventromedial Hypothalamus. Biol Sex Differ 2024, 15, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wali, J.A.; Solon-Biet, S.M.; Freire, T.; Brandon, A.E. Macronutrient Determinants of Obesity, Insulin Resistance and Metabolic Health. Biology (Basel) 2021, 10, 336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, B.L.; Norhaizan, M.E. Effect of High-Fat Diets on Oxidative Stress, Cellular Inflammatory Response and Cognitive Function. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polyzos, S.A.; Kountouras, J.; Mantzoros, C.S. Adipose Tissue, Obesity and Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Minerva Endocrinol 2017, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milić, S.; Lulić, D.; Štimac, D. Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease and Obesity: Biochemical, Metabolic and Clinical Presentations. World J Gastroenterol 2014, 20, 9330–9337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Balland, E.; Cowley, M.A. Hypothalamic Insulin Resistance in Obesity: Effects on Glucose Homeostasis. Neuroendocrinology 2017, 104, 364–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boden, G. Obesity, Insulin Resistance and Free Fatty Acids. Current Opinion in Endocrinology, Diabetes & Obesity 2011, 18, 139–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.; Chen, Y.; Cline, G.W.; Zhang, D.; Zong, H.; Wang, Y.; Bergeron, R.; Kim, J.K.; Cushman, S.W.; Cooney, G.J.; et al. Mechanism by Which Fatty Acids Inhibit Insulin Activation of Insulin Receptor Substrate-1 (IRS-1)-Associated Phosphatidylinositol 3-Kinase Activity in Muscle. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2002, 277, 50230–50236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morrison, S.F.; Madden, C.J.; Tupone, D. Central Neural Regulation of Brown Adipose Tissue Thermogenesis and Energy Expenditure. Cell Metabolism 2014, 19, 741–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yahiro, T.; Kataoka, N.; Nakamura, Y.; Nakamura, K. The Lateral Parabrachial Nucleus, but Not the Thalamus, Mediates Thermosensory Pathways for Behavioural Thermoregulation. Sci Rep 2017, 7, 5031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kullmann, S.; Heni, M.; Veit, R.; Scheffler, K.; Machann, J.; Häring, H.-U.; Fritsche, A.; Preissl, H. Selective Insulin Resistance in Homeostatic and Cognitive Control Brain Areas in Overweight and Obese Adults. Diabetes Care 2015, 38, 1044–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kullmann, S.; Valenta, V.; Wagner, R.; Tschritter, O.; Machann, J.; Häring, H.-U.; Preissl, H.; Fritsche, A.; Heni, M. Brain Insulin Sensitivity Is Linked to Adiposity and Body Fat Distribution. Nat Commun 2020, 11, 1841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahm, J.R.; Jo, M.H.; Ullah, R.; Kim, M.W.; Kim, M.O. Metabolic Stress Alters Antioxidant Systems, Suppresses the Adiponectin Receptor 1 and Induces Alzheimer’s Like Pathology in Mice Brain. Cells 2020, 9, 249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toniolo, L.; Gazzin, S.; Rosso, N.; Giraudi, P.; Bonazza, D.; Concato, M.; Zanconati, F.; Tiribelli, C.; Giacomello, E. Gender Differences in the Impact of a High-Fat, High-Sugar Diet in Skeletal Muscles of Young Female and Male Mice. Nutrients 2024, 16, 1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maldonado-Devincci, A.M.; Odelade, A.E.; Irby-Shabazz, A.; Jadhav, V.; Nepal, P.; Chang, E.M.; Chang, A.Y.; Han, J. Longitudinal Sex-Specific Impacts of High-Fat Diet on Dopaminergic Dysregulation and Behavior from Periadolescence to Late Adulthood. Nutritional Neuroscience 2024, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Der Heijden, R.A.; Sheedfar, F.; Morrison, M.C.; Hommelberg, P.P.; Kor, D.; Kloosterhuis, N.J.; Gruben, N.; Youssef, S.A.; De Bruin, A.; Hofker, M.H.; et al. High-Fat Diet Induced Obesity Primes Inflammation in Adipose Tissue Prior to Liver in C57BL/6j Mice. Aging 2015, 7, 256–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barazzoni, R.; Gortan Cappellari, G.; Ragni, M.; Nisoli, E. Insulin Resistance in Obesity: An Overview of Fundamental Alterations. Eat Weight Disord 2018, 23, 149–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Komatsu, M.; Takei, M.; Ishii, H.; Sato, Y. Glucose-stimulated Insulin Secretion: A Newer Perspective. J of Diabetes Invest 2013, 4, 511–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, D.; Yan, N. GLUT, SGLT, and SWEET: Structural and Mechanistic Investigations of the Glucose Transporters. Protein Science 2016, 25, 546–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McNay, E.C.; Pearson-Leary, J. GluT4: A Central Player in Hippocampal Memory and Brain Insulin Resistance. Experimental Neurology 2020, 323, 113076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mueckler, M.; Thorens, B. The SLC2 (GLUT) Family of Membrane Transporters. Molecular Aspects of Medicine 2013, 34, 121–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Z.; Zhong, C. Decoding Alzheimer’s Disease from Perturbed Cerebral Glucose Metabolism: Implications for Diagnostic and Therapeutic Strategies. Progress in Neurobiology 2013, 108, 21–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Witek, K.; Wydra, K.; Filip, M. A High-Sugar Diet Consumption, Metabolism and Health Impacts with a Focus on the Development of Substance Use Disorder: A Narrative Review. Nutrients 2022, 14, 2940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ristow, M.; Zarse, K. How Increased Oxidative Stress Promotes Longevity and Metabolic Health: The Concept of Mitochondrial Hormesis (Mitohormesis). Experimental Gerontology 2010, 45, 410–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camiletti-Moirón, D.; Aparicio, V.; Nebot, E.; Medina, G.; Martínez, R.; Kapravelou, G.; Andrade, A.; Porres, J.; López-Jurado, M.; Aranda, P. High-Intensity Exercise Modifies the Effects of Stanozolol on Brain Oxidative Stress in Rats. Int J Sports Med 2015, 36, 984–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papakonstantinou, E.; Oikonomou, C.; Nychas, G.; Dimitriadis, G.D. Effects of Diet, Lifestyle, Chrononutrition and Alternative Dietary Interventions on Postprandial Glycemia and Insulin Resistance. Nutrients 2022, 14, 823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.H.; Cha, M.; Lee, B.H. Crosstalk between Neuron and Glial Cells in Oxidative Injury and Neuroprotection. IJMS 2021, 22, 13315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeiger, S.L.H.; McKenzie, J.R.; Stankowski, J.N.; Martin, J.A.; Cliffel, D.E.; McLaughlin, B. Neuron Specific Metabolic Adaptations Following Multi-Day Exposures to Oxygen Glucose Deprivation. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular Basis of Disease 2010, 1802, 1095–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bryant, N.J.; Govers, R.; James, D.E. Regulated Transport of the Glucose Transporter GLUT4. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2002, 3, 267–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zwick, R.K.; Guerrero-Juarez, C.F.; Horsley, V.; Plikus, M.V. Anatomical, Physiological, and Functional Diversity of Adipose Tissue. Cell Metabolism 2018, 27, 68–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega, S.P.; Chouchani, E.T.; Boudina, S. Stress Turns on the Heat: Regulation of Mitochondrial Biogenesis and UCP1 by ROS in Adipocytes. Adipocyte 2017, 6, 56–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pickering, A.M.; Vojtovich, L.; Tower, J.; A. Davies, K.J. Oxidative Stress Adaptation with Acute, Chronic, and Repeated Stress. Free Radical Biology and Medicine 2013, 55, 109–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, V.; Mehdi, M.M. Oxidative Stress, Inflammation and Hormesis: The Role of Dietary and Lifestyle Modifications on Aging. Neurochemistry International 2023, 164, 105490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).