1. Introduction

Digital transformation (DT) has become a priority for businesses seeking to remain competitive in a global environment increasingly influenced by digital technologies [

1]. The rapid transformation of the industrial ecosystem, driven by innovative digital technologies continues to gather pace [

2]. Advances such as the emergence of global platforms, the evolution of business models, and the multiple applications of artificial intelligence across industry is profoundly redefining business practices. However, this degree of change inevitably involves a range of challenges at both company and individual levels. Indeed, according to Bughin et al.[

3], more than 70% of digital transformation initiatives fail, often due to poor management of human and organizational factors. This failure rate raises the crucial question of how prepared companies are to integrate these technologies in a way that generates real added value. Indeed, DT goes beyond the integration of technological tools; it involves a significant restructuring of internal processes and organizational, economic and financial behaviors.

Acceptance of digital technologies, both at an individual and collective level, is a key factor in the success of transformation initiatives. As Vial[

4] explains, DT “is not simply a technological transformation, but a profound and continuous organizational reinvention” (p. 121). This change can only be effective if employees and managers adopt a positive attitude towards new technologies, which highlights the importance of understanding the behavioral and social factors that influence this adoption. Previous research has highlighted the importance of a holistic approach, integrating both technological capabilities and human dynamics. Wessel et al.[

5] concluded that “the success of a digital transformation depends not only on an organization’s ability to integrate advanced technologies, but also on its ability to create an organizational environment favorable to the adoption of these technologies” (p. 236). These authors emphasize that alignment between social and technological dynamics is essential to ensure a smooth and successful transition to a digital enterprise.

Furthermore, the management of human behavior in the face of digital innovation is a critical issue. Warner and Wäger [

6], in their research of DT in the context of strategic renewal, found that the dynamic capabilities of an organization play a key role in managing the DT process, especially when it comes to adapting to new technologies and organizational changes. In other words, it is not just about acquiring technologies, but about developing an organizational culture that encourages their adoption and effective use. In this context, this research study focuses on the analysis of the key factors that influence the acceptance of DT. It aims to identify the behavioral factors and innovative characteristics of digital technologies that influence employees’ attitudes towards DT. The results provide a better understanding of how these elements contribute to the success of DT initiatives in the Moroccan insurance industry.

Following this brief introduction, there are five further sections to the article. In

Section 2, relevant literature is reviewed and the research hypotheses are set out. In

Section 3, the research methodology is outlined. Results are presented in

Section 4 and some key emergent themes are identified and discussed in

Section 5. Finally, in

Section 6, the overall contribution of the research is discussed, along with the limitations of the study, and possible future areas for research in this field are noted.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Introduction

Digital transformation has become an essential strategic lever for companies aiming to maintain competitiveness in an ever-evolving global environment. Strategic, organizational, and technological dimensions reveal a significant impact on performance, innovation, and agility within organizations. According to Sebastian et al. [

7], DT involves a fundamental reinvention of operational processes through the integration of advanced technologies such as artificial intelligence, data analytics, and the Internet of Things. These tools go beyond mere technological adoption; they also entail a profound structural and cultural transformation. Furthermore, the role of organizational culture in the success of digital initiatives is widely emphasized in the literature. Fitzgerald et al. [

8] emphasize that a culture centered on experimentation, continuous learning, and adaptability is crucial to overcoming internal resistance to change. Additionally, dynamic capabilities, defined as an organization’s ability to respond quickly and effectively to market changes, are considered pivotal for developing and implementing coherent digital strategies [

9].

The potential benefits of DT are also well-documented. According to Fang and Liu [

10], adopting digital technologies not only enhances internal processes but also enriches the customer experience, opening new avenues for competitive differentiation. However, recent research underscores risks related to cybersecurity, data ethics, and organizational imbalances, which can hinder or disrupt the implementation of digital projects [

11,

12].

This section comprises three sub-sections. In

Section 2.2, some fundamental definitions and perspectives are briefly reviewed. This is followed in

Section 2.3 by an examination of some of the theory and practice around the acceptance of DT. Building upon this,

Section 2.4 then draws out the key determinants of DT from the extant literature and puts forward the related hypotheses to be tested in the primary research phase.

2.2. Digital Transformation: Definition and Importance

Digital transformation can be defined as a comprehensive process through which companies adopt and integrate digital technologies to improve performance, generate new sources of value, and adapt to changing market dynamics [

4,

13]. However, DT is not limited to simple technological adoption. According to Kleinert [

14], DT entails a fundamental reconfiguration of business models and organizational processes, as well as a major cultural shift. This requires a systemic approach that combines technological innovation, organizational transformation, and stakeholder engagement [

15].

Companies must rethink their internal processes and value chains to adapt to a digital economy characterized by uncertainty and rapid cycles of change [

16]. Fernandez-Vidal et al. [

17] emphasize DT’s central role as a catalyst for organizational agility and innovation, enabling companies to better meet market expectations. Warner and Wäger [

6] describe it as a transformation of operational paradigms, offering businesses the opportunity to thrive in a dynamic economic context. Moreover, DT redefines the organizational competencies needed to leverage interconnected digital ecosystems, enhancing collaboration and customer engagement [

18]. In the financial sector, technologies such as automation, artificial intelligence, and blockchain have improved operational efficiency while personalizing services to meet customer expectations [

19,

20].

Furthermore, DT promotes cost optimization through automation and improves value chains [

21]. It can also contribute to sustainability by reducing companies’ carbon footprints through optimized resource management and digitalized practices [

22,

23]. According to Sebastian et al. [

7], this transformation enhances companies’ dynamic capabilities, enabling them to adapt to market disruptions while maximizing financial and operational performance. DT acts as a driver of innovation, with technologies like the Internet of Things, cloud computing, and advanced analytics allowing companies to rethink business models and value chains [

5]. However, Faraj and Pachidi [

24] stress that the success of these initiatives depends on strategic alignment between organizational objectives, technological requirements, and stakeholder expectations.

2.3. The Acceptance of Digital Transformation

The acceptance of DT by employees and stakeholders is a critical factor for the success of digital initiatives. Perceived usefulness and ease of use of digital technologies remain major determinants of their acceptance, as highlighted by the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) developed by Davis [

25]. These concepts have been expanded in recent research to include elements such as compatibility with existing processes and organizational efficiency [

26]. Oh et al. [

27] conclude that balancing ease of use with advanced functionalities is crucial to ensuring sustainable adoption, particularly in complex digital environments.

The Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT), introduced by Venkatesh et al. [

28], enriches this perspective by identifying social influence and facilitating conditions as critical factors. Trenerry et al. [

29] argue that organizational engagement and employee training are essential to strengthening these dimensions and ensuring successful adoption of digital technologies. Moreover, Slavković et al. [

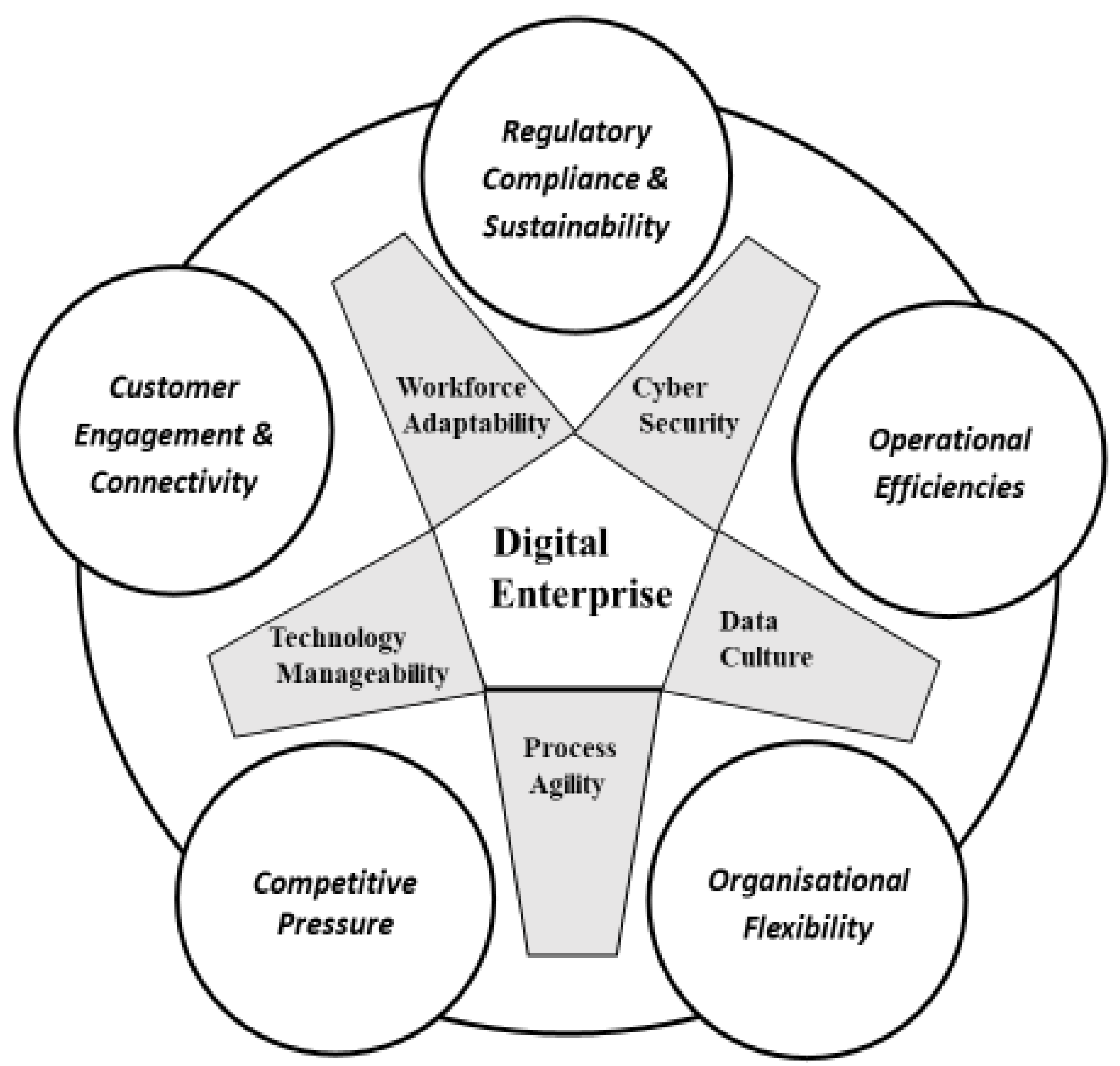

30] highlight the role of digital capabilities in aligning technology with organizational practices, emphasizing that employees’ digital citizenship plays a decisive mediating role in this process. In similar vein, Wynn and Lam [

31], in their study of DT in four major hospitality enterprises, found that workforce adaptability, process agility and a data culture were key requirements for a successful transition to a digital enterprise (

Figure 1).

Building on Rogers’ [

32] Diffusion of Innovation (DOI) theory, Steiber et al. [

33] explain that the acceptance of digital technologies depends on their perceived characteristics, such as relative advantage, compatibility, and complexity. These findings are supported by ElMassah and Mohieldin [

34], who highlight the importance of DT in localizing Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). The authors note that the perception of societal or environmental benefits can also drive employee engagement. Organizational factors, such as digital leadership and an innovation-driven culture, directly influence technology acceptance. Benitez et al. [

35] argue that leaders with strong digital capabilities foster better innovation performance, encouraging employee adoption of technologies. Schildt [

36] addresses this issue from an institutional logic perspective, showing that underlying organizational values must align with DT initiatives to ensure their success.

2.4. Key Determinants and Hypothesis Development

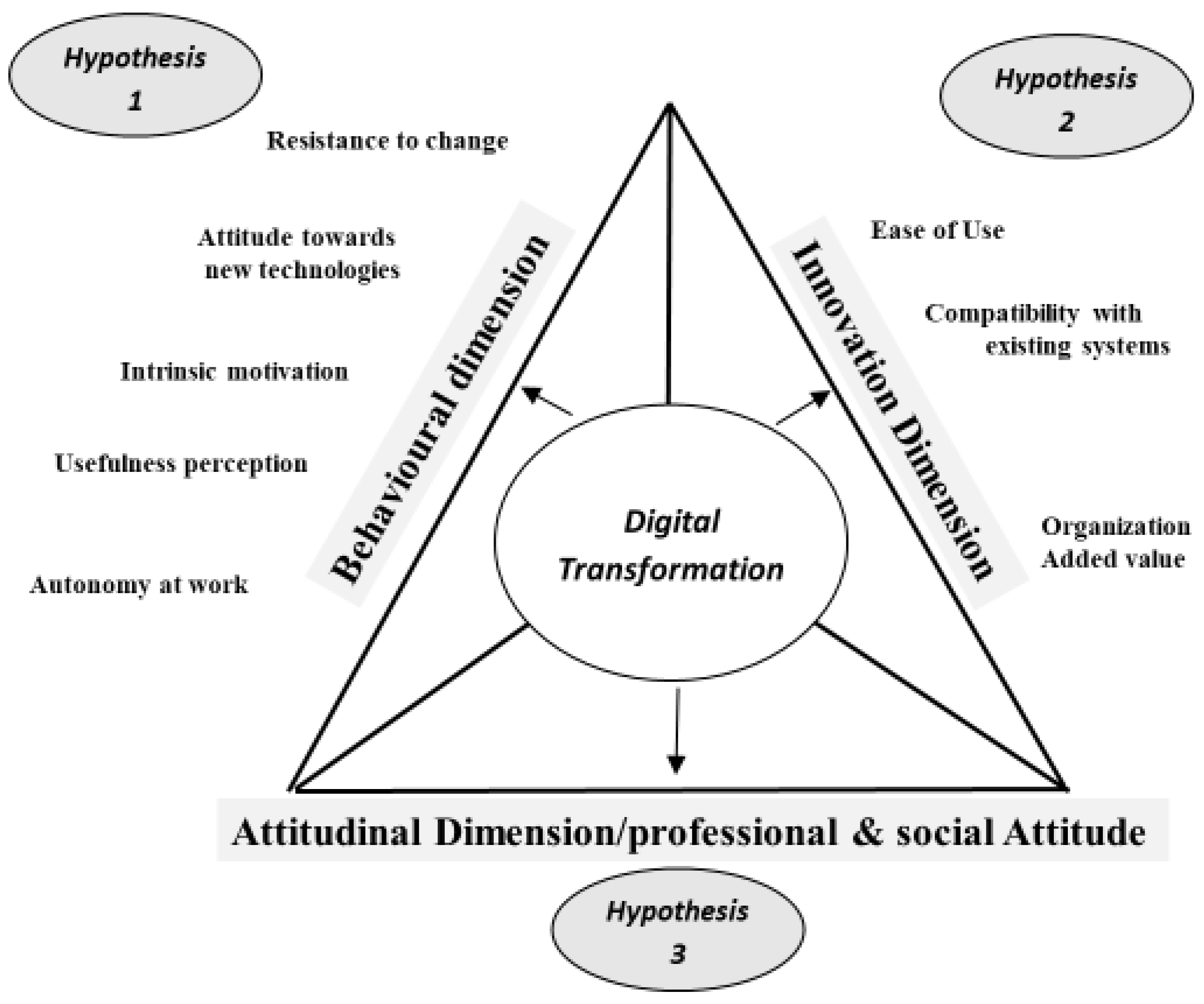

The acceptance of DT stems from a complex amalgamation of antecedents that depend not only on individuals but also on the organizations in which they operate. This has profoundly influenced management systems underpinning organizational coordination and control, and a range of models and frameworks are being used to assess the key determinants of successful DT in a rapidly evolving technology environment. These include a number of models that pre-date the digital era, such as those noted above (TAM; UTAUT; DOI), which can be applied to identify the determinants that directly impact workers’ intention to embrace DT in their professional activities. Such acceptance within organizational ecosystems relies on a triadic framework encompassing behavioral, innovation-related, and attitudinal dimensions (

Figure 2).

From the extant literature, including from the three models noted above (See

Table A1 in

Appendix A), five distinct factors (or determinants) relating to the behavioral dimension can be discerned: resistance to change; attitude toward new technologies; intrinsic motivation; perceived usefulness of technologies; and workplace autonomy. Regarding resistance to change, organizations perceive it as both a hindrance to economic development and an opportunity to understand their workers’ abilities and foster learning within a complex ecosystem [

37]. This resistance arises from feelings of fear of the unknown and loss of control [

38]. Resistance to change is thus considered an inhibitory determinant of DT acceptance. It materializes as anxiety and discomfort, stemming from employees stepping out of their comfort zones. However, proactive management of this resistance can facilitate transition [

39].

Despite its inhibitory nature, employee resistance to change also highlights positive aspects, as it prompts organizations to prioritize resources for facilitating workers’ adaptability to DT [

31] [

40]. In this context, supporting employees throughout the DT process can change resistance into anticipatory engagement [

41]. Conversely, positive attitudes toward new technologies can facilitate their use and support the acceptance of DT [

42]. Such positive attitudes toward adopting new technologies and integrating them into all professional activities enhance the success and acceptance of the transition, contributing to the sustainable improvement of organizational performance [

43].

Intrinsic motivation plays a crucial role in employees’ conscientious engagement in the DT process, driven by the personal and professional benefits they derive [

44]. High levels of employee motivation contribute to the ease of acceptance and flexibility in adopting complex digital tools, heightening the likelihood of success of DT [

29,

45]. The perceived usefulness of new technological advancements is a key predictor of the success and acceptance of DT within organizations [

46]. A strong perception of usefulness facilitates smoother acceptance and integration of the transition [

47]. The introduction of new technologies that promote workplace autonomy leads to higher job satisfaction and serves as a bridge to the successful acceptance of DT [

48]. Furthermore, the autonomy fostered by incorporating new technologies into management processes positively impacts the flexibility of transition acceptance [

49,

50].

The innovation dimension also has a significant impact on employees’ intention to embrace DT. This dimension has three main related factors: the ease of use of new technologies; their compatibility with existing systems; and their organizational added value. Regarding ease of use of technological advancements, Venkatesh et al. [

51] maintain that their user-friendliness reduces initial adoption barriers and increases acceptance levels. Furthermore, employees’ perception of the flexibility of these technologies positively influences their acceptance behavior toward DT [

52,

53]. Additionally, the perception of enhanced ease of use of new technologies can transform negative impressions into enthusiastic acceptance [

54]. Employees may exhibit acceptance of complex technologies from a learning and skills development perspective [

55].

As regards the compatibility of new technologies with existing organizational systems, Martínez-Peláez et al. [

56] argue that harmony between the implemented technological advancements and the existing management system encourages acceptance of DT and reduces employee resistance. Moreover, this alignment with existing practices helps reduce the costs of the transition and limits disruptions in management procedures and practice [

57,

58]. However, Amini and Javid [

59] argue that emphasizing the compatibility between existing systems and newly introduced technologies can constrain innovation. Chaudhuri et al. [

60] also point out that, irrespective of the technology compatibility issue, organizations often find themselves at a critical juncture in DT, requiring the adoption of scalable and transformative technologies, regardless of their complexity and the resources needed for their implementation.

Employees’ perception of the organizational added value generated by the introduction of new technologies enhances their involvement and commitment to accepting DT. Improvements in productivity and cost reduction support employees’ willingness to adopt these new technologies and associated process changes [

51]. Conversely, in scenarios where financial improvements are not in evidence, employees’ perception of the implementation of these technologies may take a negative turn [

61], potentially leading to resistance [

62].

The attitudinal dimension also demonstrates a significant correlation with employees’ intention to accept DT [

39,

63]. This dimension encompasses two main factors: professional attitude and social attitude. The first refers to employees’ willingness to develop skills and adapt to changes and new demands. This learning-oriented attitude fosters acceptance of new technologies [

64]; moreover, employees engaged in lifelong learning and actively seeking career advancement opportunities will demonstrate greater flexibility during the upheavals involved in DT [

65]. Social attitude plays a crucial role in technology acceptance [

53]. Specifically, the influence of colleagues and managers in promoting DT creates a positive sensory effect, encouraging employees to align with required initiatives and project goals [

66]. However, in some cases, social attitudes may negatively impact employees’ intentions when they perceive the technologies as irrelevant to specific organizational practices, thus hindering the acceptance of DT [

67].

Building upon this analysis of the extant literature, hypotheses were developed to test the relationships between the three main dimensions in the conceptual framework (

Figure 2) in the context of the Moroccan insurance industry: innovative characteristics of digital technologies; behavioral factors; and attitudinal (professional and social) influence on the acceptance of DT. These hypotheses are as follows:

: The behavioral dimension has a significant impact on the acceptance behavior of insurance employees with regard to DT.

: Resistance to change has a significant impact on the acceptance behavior of insurance employees towards DT.

: Attitude towards new technologies has a significant impact on the acceptance behaviour of insurance employees towards DT.

: Intrinsic motivation has a significant impact on the acceptance behavior of insurance employees towards DT.

: The perceived usefulness of technologies has a determining effect on the acceptance behavior of insurance employees with regard to DT.

: Autonomy at work significantly influences the acceptance behavior of insurance employees towards DT.

: The innovation dimension has a significant impact on the acceptance behavior of insurance employees with regard to DT

: The ease of use of technologies has a significant impact on the acceptance behavior of insurance employees with regard to DT.

: Compatibility with existing devices suggests a significant impact on employees’ acceptance behavior towards DT.

: Organizational added value contributes significantly to employees’ acceptance behavior towards DT.

: The attitudinal dimension exhibits a significant influence on the acceptance of insurance employees with regard to DT.

These hypotheses provided the basis for subsequent data analysis to identify and validate the key determinants for DT in the Moroccan insurance sector.

3. Research Method

3.1. Research Design

This study adopts a quantitative approach to analyze the factors influencing the acceptance of DT. This method was chosen for its ability to provide a comprehensive understanding of the phenomena under study, particularly by triangulating the results from quantitative data collected through surveys conducted with employees of Moroccan financial institutions, specifically insurance companies. The determinants of DT acceptance were drawn from a range of literature as discussed above, but they lean heavily on the theoretical models of TAM, UTAUT and DOI (See

Table A1 in

Appendix A). A post-positivist epistemological stance was adopted. This approach places particular emphasis on formulating core hypotheses based on a theoretical framework, with the aim of validating or refuting them within an appropriate empirical context.

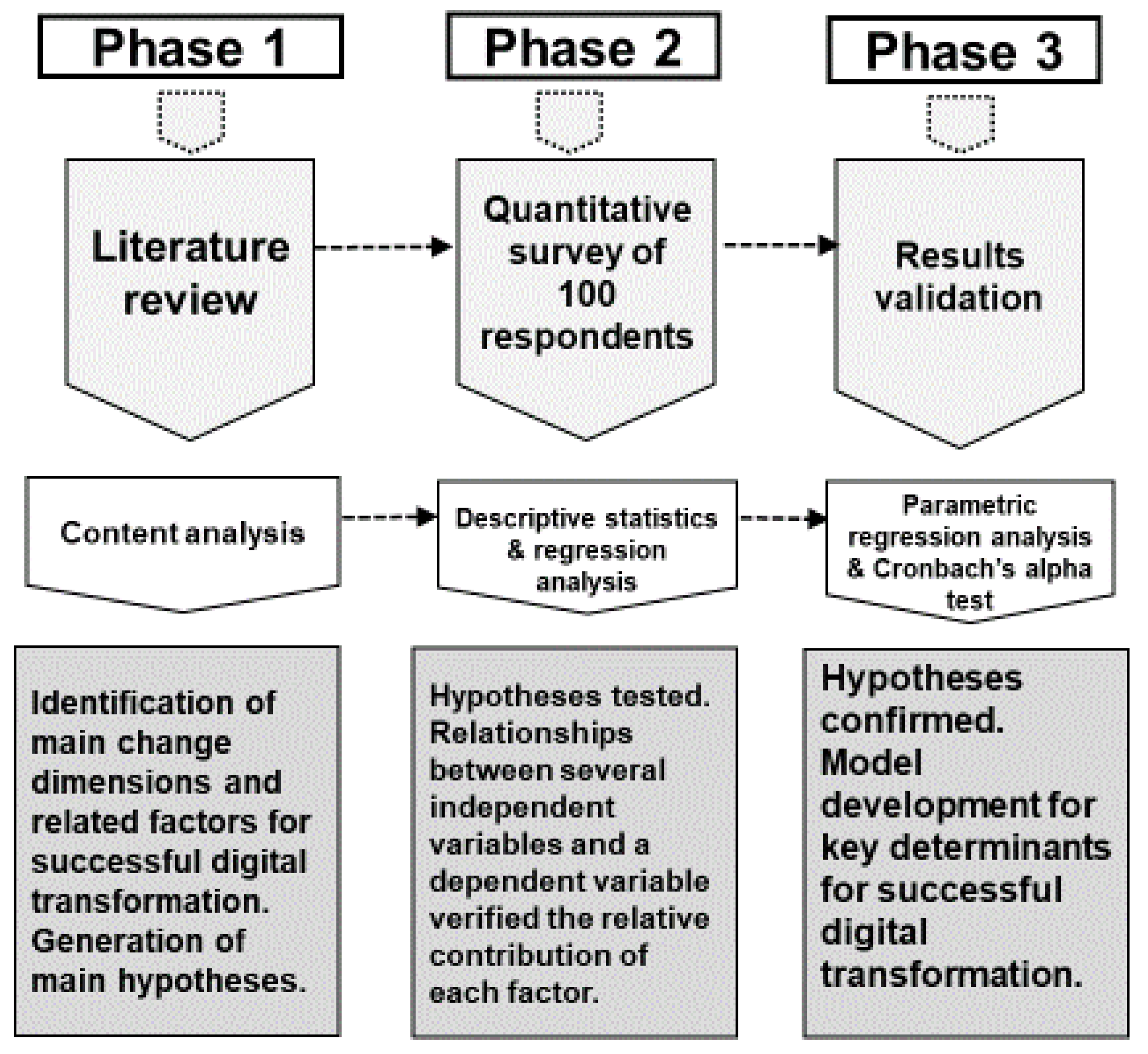

There were three main phases in the research study (

Figure 3). Phase 1 comprised a literature review that allowed for the identification of the basic conceptual framework for the hypotheses generation, as reported in

Section 2 above, and subsequent primary research.

Phase 2 involved a survey of 100 employees from Moroccan insurance companies, which are characterized by significant exposure to digital pressures where technological innovation is essential to maintaining competitiveness [

68,

69]. The sampling method used was non-probabilistic convenience sampling, selected to capture a diversity of opinions from various hierarchical levels. This method, commonly applied in exploratory studies, enables preliminary empirical analysis and hypothesis testing on a representative basis [

70].

The data were collected using a structured questionnaire consisting of 34 questions based on the TAM, UTAUT, and DOI theoretical models and related literature, and was divided into four main sections. The first section includes six demographic questions collecting general information such as age, gender, education level, and participants’ tenure. The second section contains eleven questions focused on behavioral factors, based on validated scales from the literature and measuring dimensions such as resistance to change, motivation, and attitude toward innovation. In section three, eight questions explored the innovative characteristics of technologies, including perceived usefulness and technological compatibility. Finally, the fourth section comprised nine questions evaluating participants’ overall attitudes toward DT, including professional and social acceptance. Responses were collected using a 7-point Likert scale ranging from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree,” allowing for nuanced insights into participants’ perceptions.

The analysis relies on using multiple linear regression models to measure the relative impact of each determinant on acceptance intention. All analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics software, version 27. The multiple linear regression model is a natural extension of the simple regression model for any number of explanatory variables, and more detail is provided in

Appendix B.

The quantitative data collected underwent a thorough analysis, including descriptive statistics and regression analyses, to explore and understand the relationships between various behavioral factors and the acceptance of DT. A multiple regression analysis was subsequently conducted to test the research hypotheses by examining the effect of behavioral, innovative, and attitudinal dimensions on the acceptance of DT.

Finally, in Phase 3, a parametric regression analysis was employed to validate the results, ensuring that the assumptions of linearity and normality of residuals were met, thereby guaranteeing the robustness of the conclusions.

4. Results

4.1. Demographic Characteristics of Respondents

Table 1 presents the demographic characteristics of the 100 employees who participated in the study, indicating the profile of the participants and their distribution according to the main socio-demographic variables.

The majority of participants (45%) are in the age group of 26 to 35, and 60% of respondents are men. Regarding the level of education, 50% of participants have a bachelor’s degree, while 20% have a master’s degree or higher. In terms of professional seniority, 40% of participants have between 6 and 10 years of experience, which suggests a sample mainly composed of relatively experienced employees in the insurance sector.

4.2. Descriptive Statistics of the Main Variables

The table below presents the descriptive statistics for the key variables influencing the acceptance of digital transformation, including their mean (X̅) and standard deviation (δ).

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics of the main independent variables (X).

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics of the main independent variables (X).

| Dimension |

Variables |

Coding |

|

|

| Behavioral |

Resistance to change |

RES-CH |

3.20 |

0.85 |

| Attitude towards new technologies |

ATT-TC |

4.80 |

0.72 |

| Intrinsic motivation |

INT-MT |

4.50 |

0.65 |

| Perceived usefulness of technologies |

PER-TC |

4.90 |

0.78 |

| Autonomy at work |

SE-USE |

3.80 |

0.80 |

| Innovative |

Ease of use |

EASE-USE |

5.10 |

0.75 |

| Compatibility with existing devices |

COMP-PR |

4.70 |

0.68 |

| Organizational added value |

VAL-ORG |

5.20 |

0.80 |

| Attitudinal |

Professional attitude |

PRO-ATT |

4.72 |

0.41 |

| Social attitude |

SOC-ATT |

4.65 |

0.38 |

The results show an overall favorable perception of the variables studied. In the behavioral dimension, the perceived usefulness of technologies (4.90) and the attitude towards new technologies (4.80) stand out as strong points, while resistance to change (3.20) is moderate. In the innovation dimension, ease of use (5.10) and organizational added value (5.20) obtain the highest scores, indicating a strong potential for adoption of new technologies. Finally, in the attitudinal dimension, professional (4.72) and social (4.65) attitudes demonstrate a positive predisposition of participants towards the DT. These results highlight an overall positive perception of the factors influencing the acceptance of the DT, despite some nuances concerning autonomy at work and resistance to change.

4.3. Responses of Respondents on “Intention to Accept Digital Transformation”

The table below presents respondents’ assessments of their “intention to accept digital transformation”, categorized by key dimensions and variables, along with their respective frequency distributions.

Table 3.

Responses from respondents on “intention to accept digital transformation” (Y).

Table 3.

Responses from respondents on “intention to accept digital transformation” (Y).

| Dimension |

Variables |

Frequencies |

| * |

** |

*** |

**** |

***** |

| Behavioral |

Resistance to change |

- |

- |

4% |

10% |

86% |

| Attitude towards new technologies |

- |

- |

9% |

15% |

76% |

| Intrinsic motivation |

- |

- |

7% |

21% |

72% |

| Perceived usefulness of technologies |

- |

- |

1% |

10% |

89% |

| Autonomy at work |

- |

- |

2% |

21% |

77% |

| Innovative |

Ease of use |

- |

- |

3% |

23% |

74% |

| Compatibility with existing devices |

- |

- |

- |

21% |

79% |

| Organizational added value |

- |

- |

2% |

10% |

88% |

| Attitudinal |

Professional attitude |

- |

- |

6% |

10% |

84% |

| Social attitude |

- |

- |

7% |

13% |

80% |

The results of the table show a strong intention to accept DT among respondents. The most used variables include the perceived usefulness of technologies (89%), organizational added value (88%) and compatibility with existing devices (79%), indicating very positive perceptions of these factors. Similarly, the professional (84%) and social (80%) attitude suggest a favorable climate for the adoption of new technologies. However, some aspects such as the motivation generated (72%) and autonomy at work (77%) show slightly lower scores, suggesting room for improvement to strengthen these behavioral determinants. These data confirm an overall positive predisposition, but with nuances in some dimensions.

4.4. Model Adjustment

The table below indicates how the results fit the model, including key statistical indicators adjusted, the standard error of the estimate, and the significance of changes in model fit.

Table 4.

Model fit.

| R |

|

adjusted |

Standard error of the estimate |

Modify

statistics |

| Variation of R-two |

Change in F |

ddl1

|

ddl2

|

Sign. Variation

in F |

| 0.92 |

0.94 |

0.91 |

0.081 |

0.02 |

0.137 |

99 |

891 |

0.000 |

The value of the correlation coefficient R = 0.92 gives the strength of the relationship between the independent variables (X) and the dependent variable (Y). This value expresses the appropriate adjustment of the observations to the statistical model used. However, the coefficient of determination (= 0.94) refers to the proportion of the variation of the response variable Y (acceptance of DT) explained by an assortment of explanatory variables using the multiple linear regression model. This value indicates that this statistical model used is capable of explaining the response variable at a rate of 94% in the sample proposed in the study. However, the Fisher statistics associated with the linear model are highly significant, suggesting a bilateral asymptotic significance of p = 0.000 < 0.05.

4.5. Assessment of Regression Model Quality (ANOVA)

Table 5 provides an assessment of the quality of the regression model (ANOVA), highlighting the distribution of variance via the sum of squares, degrees of freedom, F-statistic and significance level.

The ANOVA table mentions the contribution of the multiple linear model used in the explanation of the response variable Y (acceptance of DT). Based on the bilateral asymptotic significance of the F value (p = 0.000 < 0.05), the null hypothesis () is rejected, confirming the quality of the adjustment of the model used in the explanation of the dependent variable Y.

4.6. Non-Standardized Coefficients

Table 6 illustrates the non-standardized coefficients of the regression model, along with their statistical significance and 95% confidence intervals. The non-standardized coefficients make it possible to reconstruct the equation of the linear adjustment line, also called the equation of the regression line. The column of non-standardized coefficients β also provides information on the sign of this value (+ or -). This sign is important for interpreting the direction of the relationship between the dependent variable Y and the independent variables X. The value of these coefficients indicates the direction of variation of the relationship between the response variable “acceptance of the DT” and the other explanatory variables introduced in the study. For example, the explanatory variable “resistance to technological change” (RES-CH) exhibits a coefficient

= -3.079, suggesting an inverse interrelation with the dependent variable “acceptance of the DT”.

On the other hand, the other explanatory variables explain a positive impact on the intention to accept DT. In other words, the other determinants of the behavioral dimension such as an improvement in attitudes towards new technologies, high motivation, appropriate utility, and accomplished autonomy generate a positive impact on the intention to accept DT among insurers.

However, the innovation dimension, conglomerating the ease of use of digital tools, the compatibility with existing devices, and the organizational added value, also provides a positive influence on the intention of insurers to accept DT. Similarly, the attitudinal dimension bringing together professional and social attitude advances positive consequences on the ability of insurer employees to accept DT in the exercise of their daily tasks.

4.7. Parametric Regression Analysis

To further study the influence of dimensions on the acceptance of DT, a parametric regression analysis was undertaken. This statistical method is particularly suitable for evaluating the contribution of explanatory variables to a continuous dependent variable, respecting the fundamental assumptions of normality, homogeneity of variances and linearity.

Table 7 indicates that all the variables studied are significant (p < 0.05), which confirms their relevance in the model. The variable “perceived usefulness of technologies” (PER-TC) presents the highest β coefficient, highlighting its key role in the acceptance of DT. On the other hand, resistance to change (RES-CH) acts as an inhibiting factor, with a negative effect on the dependent variable. These results reinforce the overall relevance of the model and its ability to explain the determinants of acceptance. These results highlight the importance of technological adaptation and employee behavior in the success of DT.

5. Discussion

The results of this study demonstrate that the acceptance of DT is based on a combination of behavioral, innovative, and attitudinal factors. Descriptive statistics (

Table 2) reveal that innovative characteristics, such as ease of use (M = 5.10) and organizational added value (M = 5.20), achieve the highest averages, highlighting their crucial role in DT acceptance. These findings are supported by the frequencies observed in

Table 3, where 88% of participants consider organizational added value as “highly probable,” and 74% view ease of use favorably. This confirms that the innovative characteristics of digital technologies are major predictors of their adoption.

From a behavioral perspective, factors such as attitude toward new technologies (M = 4.80) and motivation (M = 4.50) also play an important role. These factors are rated as “highly probable” by 76% and 72% of respondents, respectively. However, resistance to change (M = 3.20) remains moderate, although 86% of participants consider it unlikely to be a significant obstacle to successful DT.

The multiple linear regression analyses (

Table 4 and

Table 5) confirm the excellent fit of the model. The R² value of 0.94 indicates that 94% of the variance in the dependent variable (acceptance of DT) is explained by the model. The significance of the F-statistic (p = 0.000 < 0.05) supports the robustness of the model.

Finally, the regression coefficients (

Table 6) highlight the variables with significant influence on the acceptance of DT. Among them, the perceived usefulness of technologies (β = 5.022, p < 0.001) and workplace autonomy (β = 4.028, p < 0.001) emerge as the most influential predictors.

Innovative characteristics, such as ease of use (β = 2.177, p < 0.001) and organizational added value (β = 2.017, p < 0.001), further reinforce the idea that positive perceptions of digital technologies are essential for their adoption. From a behavioral perspective, factors like attitude toward new technologies (β = 2.089, p < 0.01) and motivation (β = 3.067, p < 0.01) confirm their importance. Conversely, resistance to change (β = −3.079, p < 0.01) exerts a moderate negative influence on acceptance.

These results underline that the acceptance of DT depends on an effective alignment between technological innovation and individual behaviors. They also confirm that positive attitudes toward DT and favorable perceptions of technologies are critical in ensuring their success within organizations.

6. Conclusions

This study provides an in-depth understanding of the key factors that influence the acceptance of DT in the Moroccan insurance industry. It emphasizes the importance of combining behavioral, technological innovation, and attitudinal dimensions in such studies.

The results reveal that behavioral dimensions play a crucial role in the adoption of digital technologies. Factors such as resistance to change, attitude toward new technologies, motivation, perceived usefulness of technologies, and workplace autonomy significantly influence how employees perceive and integrate these innovations. Simultaneously, the innovation dimension, which includes ease of use, compatibility with existing systems, and organizational added value, emerges as a critical driver in encouraging the acceptance of new technologies. Lastly, the attitudinal dimension, encompassing professional and social attitudes, moderates the impact of digital innovations by reinforcing acceptance within social and professional groups.

These findings confirm that an integrated approach is indispensable for successful DT. Deploying innovative technologies alone is insufficient; it is essential to consider human factors, such as raising employee awareness about the benefits of technologies, reducing resistance to change, and fostering an organizational climate conducive to innovation. This study highlights the importance of supporting employees during their transition by valuing their autonomy and implementing tailored strategies to address their behavioral, technological, and social expectations.

This study clearly has limitations. It is based on an analysis of relevant literature and a 100-respondent survey. The survey respondents were selected through non-probabilistic convenience sampling. Generalizations from such a study must therefore be treated with caution. In addition, the study focuses on a specific context— the Moroccan insurance sector —which restricts the extrapolation of results to other regions or industries. Cultural, organizational, and economic specificities of Morocco generally influence the dynamics of technological acceptance. Nevertheless, the authors believe this research contributes to the development of theory and practice relating to DT. From a theoretical perspective, this research situates DT within the specific context of emerging economies, specifically Morocco. By exploring the interactions between behavioral, innovation, and attitudinal dimensions, it proposes a comprehensive framework that goes beyond traditional paradigms often limited to Western contexts. This contribution enriches the understanding of the complex dynamics of technological adoption, while emphasizing the importance of social acceptance and organizational compatibility in the success of digital projects.

From a practical standpoint, business leaders must adopt change management strategies that integrate training initiatives, organizational support mechanisms, and awareness campaigns. These efforts will strengthen employee engagement and maximize the success of DT. By focusing on the identified dimensions and related change factors, companies can develop tailored solutions to encourage the adoption of technologies while addressing behavioral and organizational barriers.

In conclusion, while this study has provided valuable insights into the factors influencing DT in Morocco’s insurance sector, it also provides a platform for future research. Future studies could explore these dynamics in other sectors or cultural contexts to broaden the understanding of critical change factors. DT is ultimately a multidimensional process that requires harmonious integration between technological innovations and human dimensions to ensure successful adoption. Future studies could explore several avenues. An examination of the interactions between behavioral dimensions and organizational change policies could be of value, particularly by investigating the effect of participative leadership strategies on the adoption of digital technologies. In addition, an intersectoral comparison could be conducted to identify similarities and differences in the factors influencing DT acceptance. The impact of DT on organizational performance and employee satisfaction represents another promising research area with significant practical implications for businesses. Future research can thus build on the findings reported here to further explore the complex dynamics of technological acceptance in diverse environments and through varied methodological approaches.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.A.-O.-M; M.W; O.K.; S.E.A and Z.R.; methodology, S.A.-O.-M; M.W; O.K.; S.E.A and Z.R; software, S.A.-O.-M; O.K.; S.E.A and Z.R; validation, S.A.-O.-M; M.W; O.K.; S.E.A and Z.R; formal analysis, S.A.-O.-M; M.W; O.K.; S.E.A and Z.R; investigation, S.A.-O.-M; O.K.; S.E.A and Z.R; resources, S.A.-O.-M; M.W; O.K.; S.E.A and Z.R; data curation, S.A.-O.-M; O.K.; S.E.A and Z.R; writing—original draft preparation, S.A.-O.-M; M.W; O.K.; S.E.A and Z.R; writing—review and editing, S.A.-O.-M; M.W; visualization, S.A.-O.-M; M.W; O.K.; S.E.A and Z.R; supervision, S.A.-O.-M; M.W; O.K.; S.E.A and Z.R project administration, S.A.-O.-M; M.W; O.K.; S.E.A and Z.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable

Data Availability Statement

The survey data used in this research is held within a university environment. Further enquiries can be made of the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A. Synthesis of Key Variables Derived from the TAM, UTAUT and DOI Models

Table A1.

Synthesis of key variables and concepts in the UTAUT, TAM, and DIO models.

Table A1.

Synthesis of key variables and concepts in the UTAUT, TAM, and DIO models.

| Variable |

UTAUT |

TAM |

DIO |

Authors |

| Resistance to change |

linked to Facilitating Conditions and Effort Expectancy, which address perceived barriers to adoption |

Potential negative influence on attitude towards use and intention |

Mentioned in the categorization of adopters, particularly for late adopters |

[25,28,32,71,72] |

| Attitude towards new technologies |

Approached via Intent to Use, influenced by factors such as Performance Expectancy |

Central variable: attitude towards use determines intention to use |

linked to the notions of compatibility and relative advantage |

[25,28,32,73,74,75] |

| Intrinsic motivation |

Associated with Effort Expectancy and the role of moderators |

Included in attitude towards use, influenced by ease of use |

Not directly mentioned in the model. |

[25,26,28,76] |

| Perceived usefulness of technologies |

Corresponds to Performance Expectancy, one of the main determinants of acceptance |

One of the two main variables under the name of Perceived Usefulness |

Equivalent to Relative Advantage, a key adoption factor |

[25,28,32,73,76] |

| Autonomy at work |

Addressed appears in the Facilitating Conditions that facilitate the autonomous use of technologies |

Not mentioned, but may influence attitude. |

Not directly mentioned. |

[28,77] |

| Ease of use |

Corresponds to Effort Expectancy, a key determinant of adoption |

Central variable under the name of Perceived Ease of Use, directly influencing the attitude |

Similar to the concept of complexity, one of the five main factors |

[25,28,32] |

| Compatibility with existing devices |

Indirectly covered by the Facilitating Conditions, which include integration with existing systems |

directly can influence Perceived Usefulness |

Mentioned as one of the main variables under the name of compatibility |

[28,32] |

| Organizational added value |

Addressed in Performance Expectancy, which includes organizational benefits |

Can be included in Perceived Usefulness, if the benefits are organizational |

Related to relative advantage, which considers organizational benefits |

[25,28,32] |

| Professional attitude |

Influence via moderators such as professional experience |

Influence on attitude towards use and intention |

Not directly mentioned. |

[25,28] |

| Social attitude |

Corresponds directly to Social Influence, a major determinant |

Explicitly can influence attitude towards use. |

Related to observability, which depends on social context |

[28,32] |

Appendix B. The Multiple Linear Regression Model Used in the Research Project

The linear model is the most frequently used statistical model for analyzing multidimensional data. The term “multiple” refers to the fact that there are several explanatory variables

to explain y (response variable). The information is supposed to be derived from the observation of a statistical sample of size

n (

n > p+1) of

. In this situation, the linear model is written assuming that the expectation of Y is the element of the subspace of

created by {

,

,

,

}, where 1 is the vector of

composed of “1”. In other words, the random variables (p+1) are checked:

where,

yi denotes the random variable to be explained, the

represent known, non-random numbers making explicit the explanatory variables, the

refer to the unknown, but non-random parameters to be estimated, and the

confer the random error terms of the model.

Using the least-squares estimator, the unknown model parameters

β, are estimated by minimizing the least-squares criterion (L.S.) or maximizing the likelihood (L.L.). In this survey the least squares (L.S.) criterion was used to estimate the parameter (

) ̂∈ ℝ (

p+1) that minimizes the sum of squared errors:

To estimate the unknown parameters

, the following optimization problem was solved:

To deduce the regression coefficients

β, the optimization problem was solved, conferring the minimum of F(

β), noting:

F (

). By matrix derivation of the last equation, the “normal equations” in

β were obtained as:

Assuming that the matrix (

is invertible, i.e., that the matrix

is of rank (p + 1) explaining the absence of collinearity between its columns. The parameter estimate

is given by:

References

- I. Park, D. Kim, J. Moon, S. Kim, Y. Kang, et S. Bae, « Searching for New Technology Acceptance Model under Social Context: Analyzing the Determinants of Acceptance of Intelligent Information Technology in Digital Transformation and Implications for the Requisites of Digital Sustainability », Sustainability, vol. 14, no 1, Art. no 1, janv. 2022. [CrossRef]

- T. Hess, C. Matt, A. Benlian, et F. Wiesböck, « Options for formulating a digital transformation strategy », in Strategic information management, Routledge, 2020, p. 151-173. Consulté le: 29 décembre 2024. [En ligne]. Disponible sur: https://www.taylorfrancis.com/chapters/edit/10.4324/9780429286797-7/options-formulating-digital-transformation-strategy-thomas-hess-christian-matt-alexander-benlian-florian-wiesb%C3%B6ck.

- J. Bughin, J. Deakin, et B. O’beirne, « Digital transformation: Improving the odds of success », McKinsey Q., vol. 22, p. 1-5, 2019.

- G. Vial, « Understanding digital transformation: A review and a research agenda », J. Strateg. Inf. Syst., vol. 28, no 2, p. 118-144, juin 2019. [CrossRef]

- L. Wessel, A. Baiyere, R. Ologeanu-Taddei, J. Cha, et T. Blegind-Jensen, « Unpacking the difference between digital transformation and IT-enabled organizational transformation », J. Assoc. Inf. Syst., vol. 22, no 1, p. 102-129, 2021.

- K. S. Warner et M. Wäger, « Building dynamic capabilities for digital transformation: An ongoing process of strategic renewal », Long Range Plann., vol. 52, no 3, p. 326-349, 2019.

- I.M. Sebastian, J. W. Ross, C. Beath, M. Mocker, K. G. Moloney, et N. O. Fonstad, « How big old companies navigate digital transformation », in Strategic information management, Routledge, 2020, p. 133-150. Consulté le: 29 décembre 2024. [En ligne]. Disponible sur: https://www.taylorfrancis.com/chapters/edit/10.4324/9780429286797-6/big-old-companies-navigate-digital-transformation-ina-sebastian-jeanne-ross-cynthia-beath-martin-mocker-kate-moloney-nils-fonstad.

- M. Fitzgerald, N. Kruschwitz, D. Bonnet, et M. Welch, « Embracing digital technology: A new strategic imperative », MIT Sloan Manag. Rev., vol. 55, no 2, p. 1, 2014.

- J. Wang et T. Bai, « How digitalization affects the effectiveness of turnaround actions for firms in decline », Long Range Plann., vol. 57, no 1, p. 102140, 2024.

- X. Fang et M. Liu, « How does the digital transformation drive digital technology innovation of enterprises? Evidence from enterprise’s digital patents », Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change, vol. 204, p. 123428, 2024.

- F. Almeida, J. D. Santos, et J. A. Monteiro, « The challenges and opportunities in the digitalization of companies in a post-COVID-19 World », IEEE Eng. Manag. Rev., vol. 48, no 3, p. 97-103, 2020.

- B. Metin, F. G. Özhan, et M. Wynn, « Digitalisation and Cybersecurity: Towards an Operational Framework », Electronics, vol. 13, no 21, p. 4226, 2024.

- S. Ziyadin, S. Suieubayeva, et A. Utegenova, « Digital Transformation in Business », in Digital Age: Chances, Challenges and Future, vol. 84, S. I. Ashmarina, M. Vochozka, et V. V. Mantulenko, Éd., in Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems, vol. 84. , Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2020, p. 408-415. [CrossRef]

- J. Kleinert, « Digital transformation », Empirica, vol. 48, no 1, p. 1-3, févr. 2021. [CrossRef]

- H. E. Adama et C. D. Okeke, « Digital transformation as a catalyst for business model innovation: A critical review of impact and implementation strategies », Magna Sci. Adv. Res. Rev., vol. 10, no 02, p. 256-264, 2024.

- L. Li, « Digital transformation and sustainable performance: The moderating role of market turbulence », Ind. Mark. Manag., vol. 104, p. 28-37, 2022.

- J. Fernandez-Vidal, F. A. Perotti, R. Gonzalez, et J. Gasco, « Managing digital transformation: The view from the top », J. Bus. Res., vol. 152, p. 29-41, 2022.

- S. Nambisan, M. Wright, et M. Feldman, « The digital transformation of innovation and entrepreneurship: Progress, challenges and key themes », Res. Policy, vol. 48, no 8, p. 103773, 2019.

- R. Kohli et N. P. Melville, « Digital innovation: A review and synthesis », 2019, Consulté le: 29 décembre 2024. [En ligne]. Disponible sur: https://deepblue.lib.umich.edu/handle/2027.42/146990.

- S. Abdallah-Ou-Moussa, M. Wynn, O. Kharbouch, et Z. Rouaine, « Digitalization and Corporate Social Responsibility: A Case Study of the Moroccan Auto Insurance Sector », Adm. Sci., vol. 14, no 11, p. 282, 2024.

- T. T. Sousa-Zomer, A. Neely, et V. Martinez, « Digital transforming capability and performance: a microfoundational perspective », Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag., vol. 40, no 7/8, p. 1095-1128, 2020.

- C. Xu, G. Sun, et T. Kong, « The impact of digital transformation on enterprise green innovation », Int. Rev. Econ. Finance, vol. 90, p. 1-12, 2024.

- A. Baird et L. M. Maruping, « The Next Generation of Research on IS Use: A Theoretical Framework of Delegation to and from Agentic IS Artifacts. », MIS Q., vol. 45, no 1, 2021, Consulté le: 29 décembre 2024. [En ligne]. Disponible sur: https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&profile=ehost&scope=site&authtype=crawler&jrnl=02767783&AN=149296195&h=DVYdWe0JBWknkL6JeNDoE2UtZaSaAxjABNdSqx%2Ff%2B9vKEh03AAfL9UUDufiG2GSNJIZj63lOgRWNXphK2iD5bQ%3D%3D&crl=c.

- S. Faraj et S. Pachidi, « Beyond Uberization: The co-constitution of technology and organizing », Organ. Theory, vol. 2, no 1, p. 2631787721995205, janv. 2021. [CrossRef]

- F. D. Davis, « Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology », MIS Q., p. 319-340, 1989.

- V. Venkatesh et H. Bala, « Technology Acceptance Model 3 and a Research Agenda on Interventions », Decis. Sci., vol. 39, no 2, p. 273-315, mai 2008. [CrossRef]

- K. Oh, H. Kho, Y. Choi, et S. Lee, « Determinants for successful digital transformation », Sustainability, vol. 14, no 3, p. 1215, 2022.

- V. Venkatesh, M. G. Morris, G. B. Davis, et F. D. Davis, « User acceptance of information technology: Toward a unified view », MIS Q., p. 425-478, 2003.

- B. Trenerry et al., « Preparing workplaces for digital transformation: An integrative review and framework of multi-level factors », Front. Psychol., vol. 12, p. 620766, 2021.

- M. Slavković, K. Pavlović, T. Mamula Nikolić, T. Vučenović, et M. Bugarčić, « Impact of digital capabilities on digital transformation: The mediating role of digital citizenship », Systems, vol. 11, no 4, p. 172, 2023.

- M. Wynn et C. Lam, « Digitalisation and IT strategy in the hospitality industry », Systems, vol. 11, no 10, p. 501, 2023.

- E. M. Rogers, A. Singhal, et M. M. Quinlan, « Diffusion of innovations », in An integrated approach to communication theory and research, Routledge, 2014, p. 432-448. Consulté le: 29 décembre 2024. [En ligne]. Disponible sur: https://www.taylorfrancis.com/chapters/edit/10.4324/9780203887011-36/diffusion-innovations-everett-rogers-arvind-singhal-margaret-quinlan.

- A. Steiber, S. Alänge, S. Ghosh, et D. Goncalves, « Digital transformation of industrial firms: an innovation diffusion perspective », Eur. J. Innov. Manag., vol. 24, no 3, p. 799-819, 2021.

- S. ElMassah et M. Mohieldin, « Digital transformation and localizing the sustainable development goals (SDGs) », Ecol. Econ., vol. 169, p. 106490, 2020.

- J. Benitez, A. Arenas, A. Castillo, et J. Esteves, « Impact of digital leadership capability on innovation performance: The role of platform digitization capability », Inf. Manage., vol. 59, no 2, p. 103590, 2022.

- H. Schildt, « The institutional logic of digitalization », in Digital transformation and institutional theory, Emerald Publishing Limited, 2022, p. 235-251. Consulté le: 29 décembre 2024. [En ligne]. Disponible sur: https://www.emerald.com/insight/content/doi/10.1108/S0733-558X20220000083010/full/html.

- « Komi, A. K. (2019). Le management des résistances... - Google Scholar ». Consulté le: 29 décembre 2024. [En ligne]. Disponible sur: https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=fr&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=Komi%2C+A.+K.+%282019%29.+Le+management+des+r%C3%A9sistances+%C3%A0+un+projet+d%E2%80%99innovation+par+l%E2%80%99intelligence+artificielle+dans+une+perspective+de+changement.+RIMHE%3A+Revue+Interdisciplinaire+Management%2C+Homme+%28s%29+%26+Entreprise%2C+%283%29%2C+29-54.&btnG=.

- J. Ricou et V. Moissonnier, « Outil 25. Les causes de résistance au changement », En, vol. 2, p. 78-79, 2022.

- B. Rusu, C. B. Sandu, S. Avasilcai, et I. David, « Acceptance of Digital Transformation: Evidence from Romania », Sustainability, vol. 15, no 21, p. 15268, 2023.

- P. C. Endrejat, F. E. Klonek, L. C. Müller-Frommeyer, et S. Kauffeld, « Turning change resistance into readiness: How change agents’ communication shapes recipient reactions », Eur. Manag. J., vol. 39, no 5, p. 595-604, oct. 2021. [CrossRef]

- « Kupiek, M. (2021). Digital leadership, agile change... - Google Scholar ». Consulté le: 29 décembre 2024. [En ligne]. Disponible sur: https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=fr&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=Kupiek%2C+M.+%282021%29.+Digital+leadership%2C+agile+change+and+the+emotional+organization%3A+Emotion+as+a+success+factor+for+digital+transformation+projects.+Springer+Nature.&btnG=.

- C. Guzmán-Ortiz, N. Navarro-Acosta, W. Florez-Garcia, et W. Vicente-Ramos, « Impact of digital transformation on the individual job performance of insurance companies in Peru », Int. J. Data Netw. Sci., vol. 4, no 4, p. 337-346, 2020.

- J. Allouche et R. Zerbib, « La transformation digitale : enjeux et perspectives », Rev. Sci. Gest., vol. 301302, no 1, p. 75-76, oct. 2020. [CrossRef]

- A. García-Jurado, J. J. Pérez-Barea, et F. Fernández-Navarro, « Towards Digital Sustainability: Profiles of Millennial Reviewers, Reputation Scores and Intrinsic Motivation Matter », Sustainability, vol. 13, no 6, Art. no 6, janv. 2021. [CrossRef]

- F. Kitsios, I. Giatsidis, et M. Kamariotou, « Digital transformation and strategy in the banking sector: Evaluating the acceptance rate of e-services », J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex., vol. 7, no 3, p. 204, 2021.

- B. Alturas, « Models of Acceptance and Use of Technology Research Trends: Literature Review and Exploratory Bibliometric Study », in Recent Advances in Technology Acceptance Models and Theories, vol. 335, M. Al-Emran et K. Shaalan, Éd., in Studies in Systems, Decision and Control, vol. 335. , Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2021, p. 13-28. [CrossRef]

- E. Y. Wong, R. T. Hui, et H. Kong, « Perceived usefulness of, engagement with, and effectiveness of virtual reality environments in learning industrial operations: the moderating role of openness to experience », Virtual Real., vol. 27, no 3, p. 2149-2165, sept. 2023. [CrossRef]

- P. T. Huu, « Impact of employee digital competence on the relationship between digital autonomy and innovative work behavior: a systematic review », Artif. Intell. Rev., vol. 56, no 12, p. 14193-14222, déc. 2023. [CrossRef]

- M. M. Siruri et S. Cheche, « Revisiting the Hackman and Oldham job characteristics model and Herzberg’s two factor theory: Propositions on how to make job enrichment effective in today’s organizations », Eur. J. Bus. Manag. Res., vol. 6, no 2, p. 162-167, 2021.

- J. R. Hackman, « Work redesign », ReadingAddison-Wesley, 1980.

- V. Venkatesh, F. D. Davis, et Y. Zhu, « Competing roles of intention and habit in predicting behavior: A comprehensive literature review, synthesis, and longitudinal field study », Int. J. Inf. Manag., vol. 71, p. 102644, août 2023. [CrossRef]

- L. M. Maruping, H. Bala, V. Venkatesh, et S. A. Brown, « Going beyond intention: Integrating behavioral expectation into the unified theory of acceptance and use of technology », J. Assoc. Inf. Sci. Technol., vol. 68, no 3, p. 623-637, mars 2017. [CrossRef]

- V. Venkatesh, H. Bala, et T. A. Sykes, « Impacts of Information and Communication Technology Implementations on Employees’ Jobs in Service Organizations in India: A Multi-Method Longitudinal Field Study », Prod. Oper. Manag., vol. 19, no 5, p. 591-613, sept. 2010. [CrossRef]

- M. Liu et al., « What influences consumer AI chatbot use intention? An application of the extended technology acceptance model », J. Hosp. Tour. Technol., vol. 15, no 4, p. 667-689, 2024.

- M. Molino, C. G. Cortese, et C. Ghislieri, « The promotion of technology acceptance and work engagement in industry 4.0: From personal resources to information and training », Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health, vol. 17, no 7, p. 2438, 2020.

- R. Martínez-Peláez et al., « Role of Digital Transformation for Achieving Sustainability: Mediated Role of Stakeholders, Key Capabilities, and Technology », Sustainability, vol. 15, no 14, Art. no 14, janv. 2023. [CrossRef]

- R. Kemp, « Technology and the transition to environmental sustainability: The problem of technological regime shifts », Futures, vol. 26, no 10, p. 1023-1046, déc. 1994. [CrossRef]

- S. Leroy, A. M. Schmidt, et N. Madjar, « Interruptions and Task Transitions: Understanding Their Characteristics, Processes, and Consequences », Acad. Manag. Ann., vol. 14, no 2, p. 661-694, juill. 2020. [CrossRef]

- M. Amini et N. Jahanbakhsh Javid, « A Multi-Perspective Framework Established on Diffusion of Innovation (DOI) Theory and Technology, Organization and Environment (TOE) Framework Toward Supply Chain Management System Based on Cloud Computing Technology for Small and Medium Enterprises », 1 janvier 2023, Social Science Research Network, Rochester, NY: 4340207. Consulté le: 30 décembre 2024. [En ligne]. Disponible sur: https://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=4340207.

- R. Chaudhuri, S. Chatterjee, M. M. Mariani, et S. F. Wamba, « Assessing the influence of emerging technologies on organizational data driven culture and innovation capabilities: A sustainability performance perspective », Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change, vol. 200, p. 123165, mars 2024. [CrossRef]

- M. Rožman, D. Oreški, et P. Tominc, « Artificial-Intelligence-Supported Reduction of Employees’ Workload to Increase the Company’s Performance in Today’s VUCA Environment », Sustainability, vol. 15, no 6, Art. no 6, janv. 2023. [CrossRef]

- A. I. Stoumpos, F. Kitsios, et M. A. Talias, « Digital Transformation in Healthcare: Technology Acceptance and Its Applications », Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health, vol. 20, no 4, Art. no 4, janv. 2023. [CrossRef]

- M. Fishbein, Prédire et modifier le comportement: L’approche de l’action raisonnée. [CrossRef]

- L. Kolb, « Keynote: The Triple E Framework: Using Research-Based Strategies for Technology Integration », présenté à SITE - Society for Information Technology & Teacher Education International Conference, Association for the Advancement of Computing in Education (AACE), 2020. Consulté le: 29 décembre 2024. [En ligne]. Disponible sur: https://www.learntechlib.org/primary/p/216133/.

- Y. K. Dwivedi et al., « Setting the future of digital and social media marketing research: Perspectives and research propositions », Int. J. Inf. Manag., vol. 59, p. 102168, 2021.

- M. Gerlich, « Perceptions and Acceptance of Artificial Intelligence: A Multi-Dimensional Study », Soc. Sci., vol. 12, no 9, Art. no 9, sept. 2023. [CrossRef]

- S. Jierasup et A. Leelasantitham, « A Change from Negative to Positive of Later Adoption Using the Innovation Decision Process to Imply Sustainability for HR Chatbots of Private Companies in Thailand », Sustainability, vol. 16, no 13, Art. no 13, janv. 2024. [CrossRef]

- J. Fernandez-Vidal, R. Gonzalez, J. Gasco, et J. Llopis, « Digitalization and corporate transformation: The case of European oil & gas firms », Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change, vol. 174, p. 121293, 2022.

- Y. Zhang et S. Jin, « How does digital transformation increase corporate sustainability? The moderating role of top management teams », Systems, vol. 11, no 7, p. 355, 2023.

- E. Bell, A. Bryman, et B. Harley, Business research methods. Oxford university press, 2022. Consulté le: 29 décembre 2024. [En ligne]. Disponible sur: https://books.google.com/books?hl=fr&lr=&id=hptjEAAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PP1&dq=Bell,+E.,+Bryman,+A.,+%26+Harley,+B.+(2022).+Business+research+methods.+Oxford+University+Press.&ots=Ddmi37A20C&sig=KkqdaSRmg8NFAfE63ujfZ2F4DzI.

- « SolvInnov ». Consulté le: 30 décembre 2024. [En ligne]. Disponible sur: https://solvinnov.com/literature/a-model-of-innovation-resistance/.

- J. N. Sheth et W. H. Stellner, Psychology of innovation resistance: The less developed concept (LDC) in diffusion research. College of Commerce and Business Administration, University of Illinois at …, 1979. Consulté le: 30 décembre 2024. [En ligne]. Disponible sur: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Jagdish-Sheth/publication/237065197_Psychology_of_Innovation_Resistance_The_Less_Developed_Concept_in_Diffusion_Research/links/0046351b1f0eb33955000000/Psychology-of-Innovation-Resistance-The-Less-Developed-Concept-in-Diffusion-Research.pdf.

- V. Venkatesh, H. Bala, et T. A. Sykes, « Impacts of Information and Communication Technology Implementations on Employees’ Jobs in Service Organizations in India: A Multi-Method Longitudinal Field Study », Prod. Oper. Manag., vol. 19, no 5, p. 591-613, sept. 2010. [CrossRef]

- I. Ajzen, « The Theory of planned behavior », Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process., 1991, Consulté le: 30 décembre 2024. [En ligne]. Disponible sur: https://sk.sagepub.com/hnbk/edvol/hdbk_socialpsychtheories1/chpt/theory-planned-behavior.

- M. Sherif et C. I. Hovland, « Social judgment: Assimilation and contrast effects in communication and attitude change. », 1961, Consulté le: 30 décembre 2024. [En ligne]. Disponible sur: https://psycnet.apa.org/record/1963-06591-000.

- G. C. Moore et I. Benbasat, « Development of an Instrument to Measure the Perceptions of Adopting an Information Technology Innovation », Inf. Syst. Res., vol. 2, no 3, p. 192-222, sept. 1991. [CrossRef]

- J. Ellul, « The autonomy of technology », Technol. Values Essent. Read., p. 67-75, 1964.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).