1. Introduction

Digital transformation reshapes workplaces, jobs, and tasks [

1]. Governments anticipate adopting new technologies and digital offerings to benefit companies and citizens. Therefore, the limited adoption of digital technologies [

2] warrants further investigation. Previous research has explored the use of new technologies and organisational change, emphasising the significance of external conditions on the one hand and the importance of personal attributes, such as self-efficacy and the capacity to organise and reflect on one's work, on the other [

3,

4]. Based on the premise that the desired benefits of the transformational process can only be realised when individuals are willing to adopt it [

5], the focus on individual factors is accentuated. The ongoing disruptive changes necessitate fundamentally transforming individual capabilities and adaptation readiness. New competency profiles must be developed and tailored to meet evolving work requirements [

6]. Higher education is responsible for preparing students and cultivating the necessary competencies. Hartmann et al. [

7] aim to identify and categorise what is termed “future skills,” defined as competencies needed to confront challenges in an uncertain and changing environment [

3]. Thus, a deeper exploration of new competencies for “learning 4.0” in workplaces [

8,

9] is essential. The transformational process impacts the current workforce due to job specifications and task changes. It is inadequate to acquire knowledge of specific technologies or work processes merely. The founding community for German research has published a discussion paper in collaboration with McKinsey, highlighting essential competencies for a changing world, divided into four categories: technological, digital, classic, and transformative competencies [

10]. The classic competencies encompass creativity and problem-solving abilities, which are enhanced through self-reflection and autonomous problem-solving. Innovative teaching concepts encourage independently acquired knowledge, such as design thinking or learning videos [

7]. Applying this to a new work context emphasises the need for active participation of employees in digital workplaces. For this purpose, this study investigates two fundamental antecedents of individual competence and learning in digital workplaces: 1) self-determined motivation and 2) innovation adoption. To address the existing knowledge gap about the prerequisites of individual digital competencies, we integrate research streams on innovation adoption and motivation alongside studies in education and learning, focusing on developing future learning concepts for the workforce and adaptability for transformation [

3]. As an empirical implication, we created a conceptual model and tested the presumed effect of self-determined motivation and innovation adoption on individuals` digital competencies and learning. Understanding the mechanisms that enable employees to succeed in new work environments allows organisations to act effectively and accelerate digital transformation. Given that digital competence and learning are critical factors for individuals, organisations, and nations, deeper insights are necessary to establish appropriate framing conditions or provide targeted support.

2. Literature Review and Hypothesis Development

Employees are indispensable to any economy and organisation. Goldin and Katz highlighted the relationship between economic growth, technology, and education concerning the U. S. labour market [

11]. They argue that human capital is a significant driver of economic development, emphasising the need for investments in knowledge of new technologies. Contemporary workplaces are characterised by uncertainty and disruptive changes by digital transformation. As there is no standard definition of digital transformation, this paper adopts the summary proposed by Vial [

12], which defines digital transformation as a process aimed at enhancing services or processes by instigating significant changes through the implementation and use of technology. Developing digital competence, knowledge management, and deployment presents a new challenge. Learning and knowledge are essential capabilities that foster continuous innovation and facilitate digital transformation [

13]. Previous research points to sustained learning effects through self-determined acquisition of relevant skills and knowledge [

14,

15]. This research emphasises personal responsibility and self-determination as essential for integrating digital technologies into everyday routine processes and developing sustained knowledge and learning. This paper investigates the relationship between self-determined motivation, innovation adoption, digital competence, and learning to understand better the mechanisms and leverage involved.

2.1. Dependent Variable: Learning

Current literature displays learning as a fundamental factor in performing in digital environments through knowledge and competence. However, there is no common concept of learning in digital transformation. Crossan et al. [

16] highlight the complexity and different viewpoints on individual, group, and organisational levels, as well as cognitive and behavioural factors. Learning enables individuals and organisations to perform and innovate under rapidly changing conditions [

17]. Fiol et al. define organisational learning as improving actions through better knowledge and understanding [

18]. Argyris and Schön underscore individuals’ needs and the effect on their well-being and motivation to enhance learning [

19]. This adaptability and continuous learning loops [

20] need to be established to perform in changing environments under uncertain conditions [

21]. Previous research implies the positive influence of organisational learning as a contextual factor on innovation adaption [

22] and digital competencies [

23]. In contrast, learning on an individual level is a process with modifications in response to a stimulus because of environmental interactions [

24]. This paper measured and tested learning on an individual level to better understand the mechanisms impacting the targeted transformation process [

25].

2.2. Independent Variables

2.2.1. Self-Determined Motivation

Self-determination Theory (SDT) has been studied across various fields to explain motivation, particularly in the workplace [

26]. It posits that employees' performance and well-being are influenced by their motivation for job-related activities [

27]. Deci and Ryan argue that all employees have fundamental needs for autonomy, competence, and relatedness. The level of satisfaction and type of motivation drive this effect. Autonomy refers to the perceived control over one’s behaviour, allowing for voluntary choices in action [

28]. Digital transformation is a disruptive phenomenon. The workforce increasingly faces digital technology and processes in both professional and personal contexts. Some individuals experience a loss of control as a result. When applying this theory to new digital workplaces, we assume that employees may struggle to meet the new digital requirements [

8], which could explain the lagging transformational process. Individuals desire to maintain their identity by making an ambitious contribution to their work (intrinsic motivation). However, they may be unable to do so due to a lack of competence, potentially leading to frustration, resignation, or even burnout [

29]. SDT emphasises autonomy as a basic human need that, when supported, results in more effective and sustained behavioural regulation [

28]. Even if employees initially lack intrinsic motivation to engage in digital transformation, it is possible to design external factors—such as a supportive work environment or an organisational learning culture that promotes freedom of choice—to foster autonomous motivation [

30]. We consider autonomy to have a significant positive impact on intrinsic motivation for developing digital competencies. Competence is the sense of being practical and contributing effectively with one’s capabilities to achieve desired outcomes [

28]. Interactions with the environment lead to the development of specific competencies through adaptation. Consequently, the need to acquire competencies motivates individuals to engage in learning [

27]. For successful digital transformation, new competencies are required. According to the age and duration of the job, these competencies were probably not necessary, or not needed to the same extent, during employees' studies or job training. We argue that fulfilling their basic need to feel competent enhances employees' intrinsic motivation to learn and acquire new digital competencies. Relatedness involves feeling respected and knowing that others are close, caring, and understanding [

28]. Social factors significantly influence employees’ motivation to contribute to their work and behaviour to benefit the environment [

30], creating a motivating and supportive atmosphere for digital transformation. Employees not intrinsically motivated to engage autonomously in digital transformation may internalise extrinsic motivation through collective interests. SDT was developed to understand intrinsic motivation and why individuals engage in activities out of genuine interest [

31]. Applying this theory to digitally transformed workplaces illustrates that motivation is a fundamental mechanism enabling employees to cope with changing situations. Based on this, we posit that employees are more motivated to acquire digital competencies and learn to apply digital technologies when their basic needs are satisfied through empowerment, strengthening, and connection [

26].

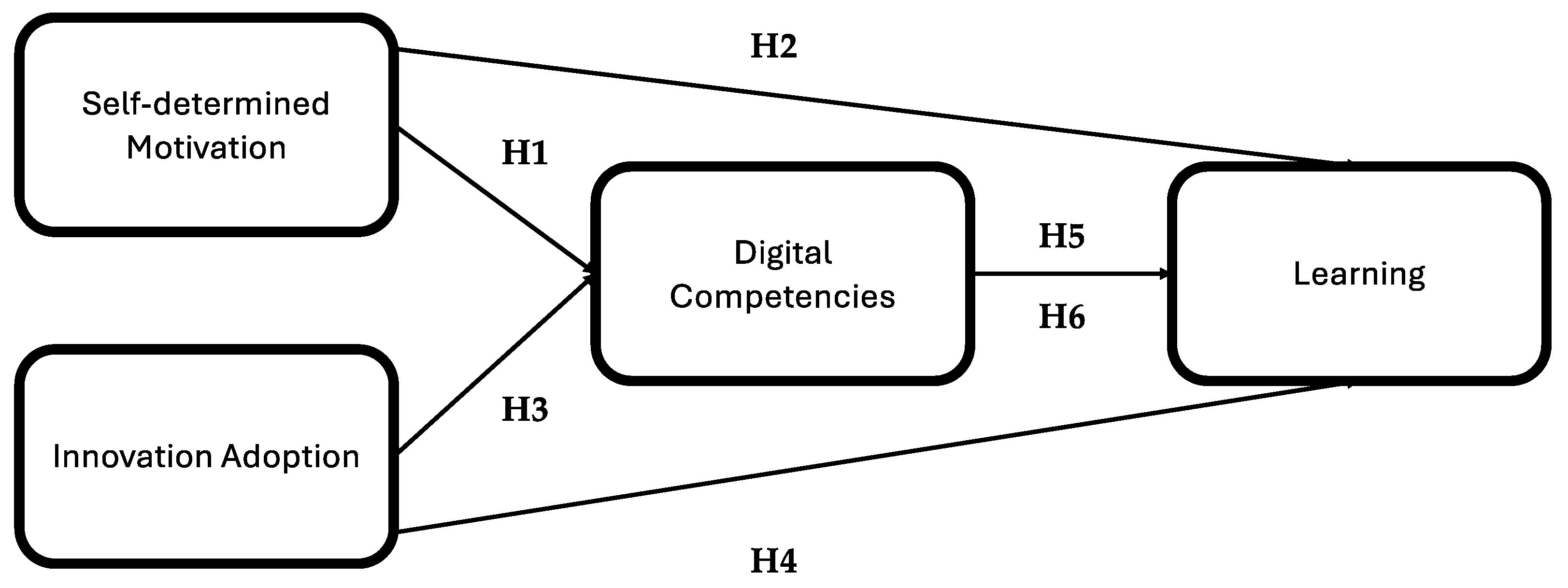

Hypothesis 1 (H1): An individual`s self-determined motivation positively affects their digital competencies in the context of digital transformation.

Hypothesis 2 (H2) An individual`s self-determined motivation positively affects learning in the context of digital transformation.

2.2.2. Innovation Adoption

The Diffusion of Innovation theory (DOI) is a social science theory that explains how innovation spreads over time as a process [

32]. Individuals and their perceptions of technology and processes play a crucial role. According to DOI, the stages of adoption depend on five perceived attributes: relative advantage, compatibility, complexity, trialability, and observability. Relative advantage refers to the degree to which an innovation is viewed as better than previous processes, products, or technology [

22]. This perception encourages the early adoption of innovations. Compatibility indicates how much an innovation aligns with an individual's values, needs, and past experiences [

4]. Innovations that conflict with existing norms and practices tend to be adopted more slowly. Complexity measures how easy or difficult an innovation is perceived in terms of understanding and usage [

32]. Thus, this attribute is synonymous with “ease of use.” Innovations that are simple to use will likely be adopted sooner. Trialability assesses the degree to which an innovation can be tested and explored over a limited period [

33]. Innovations will be adopted more quickly if individuals can familiarise themselves with them and experiment in a safe environment. Observability refers to how visible an innovation is, allowing individuals to see its results and reducing uncertainty [

34].

An innovation will be adopted quicker if it can be seen and discussed with others who have already adopted it. DOI was developed to describe the stages of how an innovation spreads over time, diffusing as a process. These aspects are antecedents to categorise users and their tendency to adopt innovation. The categorised groups (innovators, early adopters, early majority, late majority, and laggards) are essential for organisations to differentiate and develop strategies for how these personalities can be targeted [

34]. As far as this study wants to shed light on the effect of individual self-determined motivation and innovation adoption to accelerate digital transformation, it focuses on the individual perception of the five mentioned attributes. Individual innovation adoption is the personal attitude to accept an innovation (an idea, product, process, or service perceived as new)[

35]. We assume that the perceived attributes of innovation are relevant antecedents for the willingness of individuals to acquire digital competencies to work with the latest technologies and digital processes.

Hypothesis 3 (H3): Individual innovation adoption positively affects digital competencies in the context of digital transformation.

Hypothesis 4 (H4): Individual innovation adoption positively affects learning in the context of digital transformation.

2.3. Mediating Variable: Digital Competence

Knowledge and competence affect employees´ confidence in digital technology [

10,

36]. Digital competencies enable employees to participate actively in a digitalised environment [

29]. Organisations must identify their employees' existing and required competencies and develop solutions to transform their human capital, adapting to changing technologies [

37]. Recommendations and initiatives from the European Union emphasise the significance and scope of key competencies for all citizens, applicable in the private sphere, the labour market, and the economy. In their council recommendations, the EU suggests that member states promote these key competencies, defined as “a combination of knowledge, skills, and attitudes” necessary for lifelong learning [

38]. The European Commission developed a digital competence framework for citizens (DigComp), encompassing competence areas such as communication, networking, digital literacy, security, and content development [

39], with knowledge, skills, and attitudes outlined for each competence. The terms “competencies” and “skills” are often used interchangeably, yet they differ in specificity. The European Commission defines competencies in its “Recommendations for Lifelong Learning” as knowledge, skills, and attitudes necessary for various aspects of life, such as personal fulfilment, active participation, and employment [

38]. Stofkova et al. [

40] describe digital skills as formal learning, contributing to the knowledge needed to handle digital assets in the economy. In this context, skills represent a more detailed application of specific use cases within the broader competence framework. Research in HR development and education aims to identify the key competencies required for the labour market, especially in personnel development and education [

8,

29,

41,

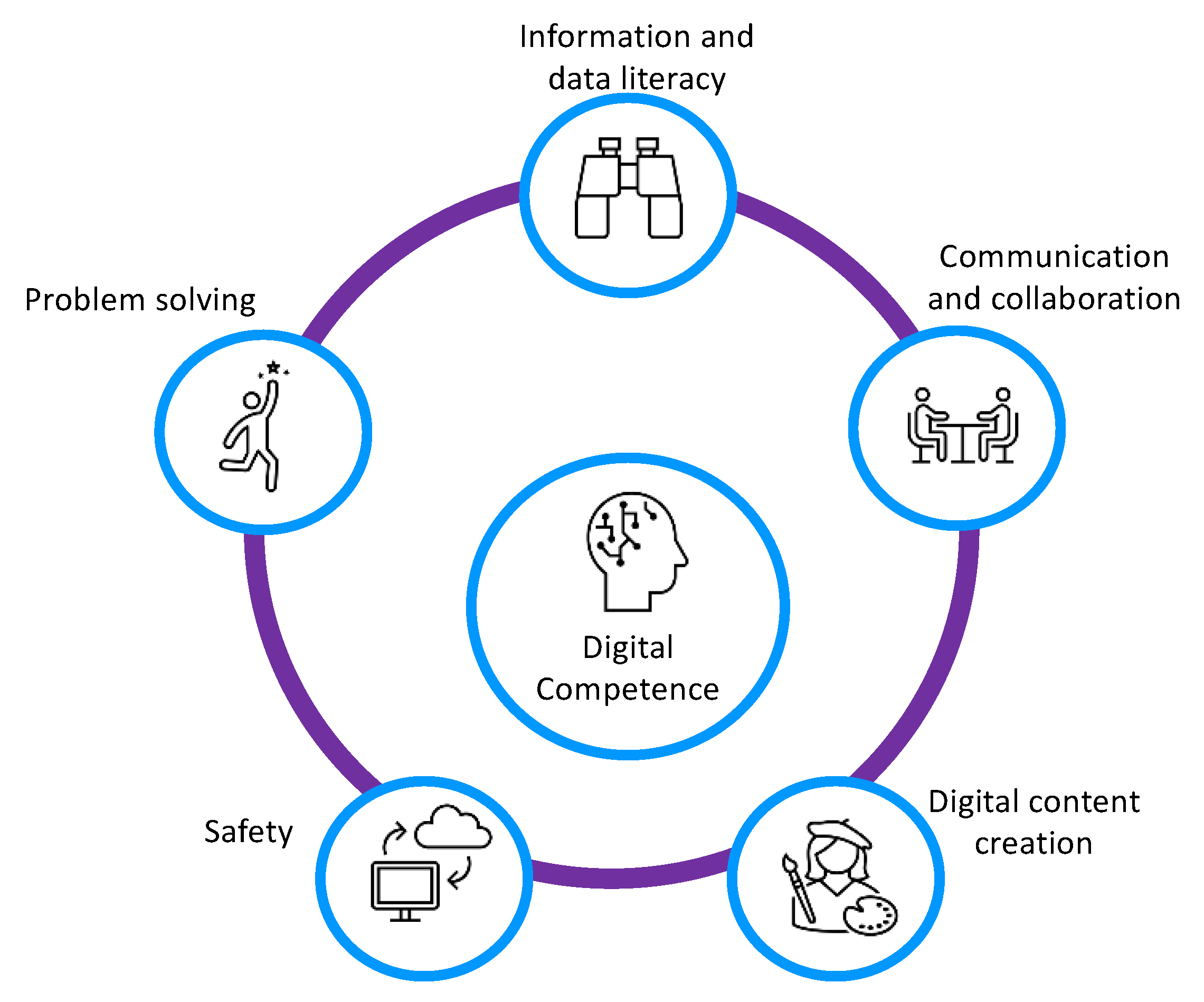

42]. This research paper adopts the DigComp framework to focus on digital competencies.

Previous research indicates that interaction with the environment and adaptation lead to learning over time [

27]. Suppose individuals possess the behavioural intention to adopt innovation and acquire self-directed knowledge. In that case, digital competence- such as the ability to operate digital learning platforms, search for suitable learning content, or use digital tools to design their learning paths [

43]- is expected to impact learning effectiveness. Therefore, we hypothesise a mediating effect of digital competence.

Hypothesis 5 (H5): Digital competencies mediate the effect of self-determined motivation on learning.

Hypothesis 6 (H6): Digital competencies mediate the effect of innovation adoption on learning.

The model constructed is presented in

Figure 1, based on the literature review and the proposed relationships.

3. Materials and Methods

Four variables were defined based on existing research and theories, and a conceptual model was developed. A questionnaire was designed to test this model according to items and measurements utilised in previous studies [

43,

44,

45]. The hypothesis and measures were tested using a questionnaire on LinkedIn and Prolific platforms. Different scales were used for the psychological separation to avoid common method bias (a 5-point Likert scale for digital competencies and a 7-point Likert scale for other items) [

46]. The statistical analysis in the software Smart PLS was conducted with standardised data.

3.1. Variables

Items to measure the dependent variable learning are adopted by Arranz et al. [

44] and Lee et al. [

47], measuring knowledge resources for behavioural and cognitive learning factors. These items are adequate to measure the desired outcome, as learning results from individual behaviours with their ability to explore, detect and solve problems, change established routines and perform in new digital environments [

48]. The independent variables are based on established scales. Self-determination motivation items were developed based on the Basic Needs Scale [

27], which was adopted in various studies [

49,

50]. This scale measures the dimensions of autonomy, competence and relatedness. To measure innovation adoption, the items were developed based on Roger´s Diffusion of Innovation theory [

32], which was widely applied in this research field to test innovation adoption [

51,

52]. The items in the survey measure the five perceived attributes of relative advantage, complexity, compatibility, trialability and observability, which are accepted in research as technological antecedents for innovation adoption on the individual level [

53]. The proposed mediating variable digital competence comprises the dimensions of the current level, willingness to increase this level, and importance for the job, as the European Commission emphasises [

54]. The items are based on the five competence areas developed by the DigComp framework (

Figure 2) as an appropriate measurement in the human-centred approach [

42].

For each of these five areas, the self-assessed current level and willingness to increase this level are asked. This is adapted by the O*net program [

55], which aims to investigate and provide information about the competencies relevant to the labour market and its impact on the U.S. economy. This database and measures are established and widely applied to analyse the needs of organisations and employees [

56].

3.2. Survey Design

To prevent common method bias, the dependent and independent variables measures were methodologically separated using various scales and psychologically divided by placing socio-demographic questions in between [

46]. The questionnaire consisted of 52 questions in English and was translated into German, adopted on existing scales applied in previous research. The survey was distributed in both languages via “LinkedIn” to reach an appropriate sample of employees with basic digital capabilities and extended with participants completing the questionnaire in English by a collector using the online platform Survey Monkey. Sample questions are displayed in

Table 1.

Participants were asked to share the survey link on social networks or directly, using purposive sampling, a commonly used approach in research [

59]. The survey was also conducted via the Prolific platform to expand the range of responses. Prolific is a marketplace for online survey research, which is also applied in other research on digital transformation in healthcare [

60]. The tools SmartPLS 4 and Jamovi were used to analyse the gathered data.

4. Results

The survey was responded to by 152 participants, 126 in English and 26 in German language. 52 % of the respondents are female, 47 % male, 1 % divers. Most participants are employees (25%) or seniors/experts (27%), 23 % are in management positions, 40 % are aged 41 and above, and most of the participants (47%) are aged between 25 and 40. The software Jamovi and Smart-PLS were used to analyse the data. Harman´s single-factor test (HSF) was used as a first measure. This analysis assumes that the manifestation of a single dominant factor points to common method bias. All items are summarised into one single factor, and the percentage of variance in total of this single factor is compared against the threshold of 0.5 [

61]. The variance was tested using the principal component analysis in Jamovi. The resulting 0.25 is beneath the threshold of 0.5, meaning the item characteristics differ [

62]. Based on this result, common method bias is not prevalent in this study. Next, the data distribution was checked with the Shapiro-Wilk test. Since p was lower than .05 for all items, the Shapiro-Wilk test is significant, and the data is not normally distributed. Because of that, Smart PLS 4 was used to test and analyse the results, applying PLS-SEM since normal distribution is not a precondition. PLS-SEM is an appropriate tool for multivariate analysis, which is widely applied in business research [

63].

4.1. Outer Model Results

Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was conducted in Jamovi to assess the model fit. An RSMEA of less than .05 indicates a good fit, .08 indicates a reasonable fit, and over .1 indicates a poor fit. The chi-square statistic represents the difference between the expected and observed data; a lower chi-square value indicates a better model fit. The results are presented in

Table 3, where the chi-square test suggests no exact fit, while the RSMEA shows a reasonable model fit.

However, these model fit indicators may be overly sensitive for constructs with many items [

64]. Therefore, the model was constructed and further tested in Smart PLS software, evaluating the outer model for reliability. Items with weaker loadings that do not meet the recommended threshold for indicator reliability should only be deleted to enhance composite reliability or internal consistency [

63]. Based on the results of the p-value test for statistical significance, four indicators with factor loadings below the threshold of 0.708 were removed (AUT2, COMP1 from the construct self-determined motivation; CPX2, CPX3 from the construct innovation adoption). After removing these items, Cronbach´s alpha for all variables is more significant than 0.7, and the items of each construct are related to each other. For convergent validity, the average variance extracted (AVE) should exceed 50%, which is also achieved after this elimination, thus ensuring internal consistency and item reliability [

65]. The results are displayed in

Table 4.

Next, discriminant validity was assessed by the heterotrait-monotrait (HTMT) ratio of correlation to detect validity problems [

66]. Each indicator's factor loading is more significant than all other constructs' loadings (

Table 5), except for self-determined motivation/innovation adoption, which is acceptable since both constructs are conceptually similar [

67]. This suggests that the items assess distinct constructs [

66].

The variance inflation factor (VIF) was checked for all items for collinearity statistics. Since VIF is lower than 3 for all items, multicollinearity is absent [

68].

4.2. Inner Model Results

R

2 measures the extent to which the independent variables predict the dependent variable. Values above 0.75 are described as substantial, 0.5 as moderate, and 0.25 as weak [

63]. The inner model results are displayed in

Table 6.

Digital competence can be predicted to be 53%, according to both independent variables: self-determined motivation and innovation adoption. The constructed model has good predicting power for the outcome variable learning (58%). The path coefficient 0.597 supports the hypothesised relationship between innovation adoption and digital competencies (H3) and is statistically significant with a p-value of 0.000). The relationship between self-determined motivation and digital competencies (H1) is weaker (0.158) and not statistically significant (p-value 0.090).

The mediation effect was calculated using Baron and Kenny´s steps (1986) for mediation. In contrast to self-determined motivation, which is dismissed, innovation adoption significantly impacts the dependent variable of learning (

Table 7).

The path coefficient of the independent variable to the hypothesised mediating variable digital competence shows a significant connection (

Table 8).

Adding the mediating, the effect between independent and dependent is significantly decreased, as presented in

Table 9 [

69].

Based on these steps, the proportion of the variance of a dependent variable that is explained by a mediation relationship (Variance Accounted For = VAF) is calculated (

Table 10):

The following applies:

a = path coefficient from IV to mediator

b = path coefficient from mediator to DV

c´= direct effect from IV to DV in the presence of the mediator

Table 10.

Results of the mediation analysis of digital competence.

Table 10.

Results of the mediation analysis of digital competence.

| Independent variable |

Direct effect |

Indirect effect |

Total effect |

VAF |

Mediation |

| Self-determined motivation |

0.140* |

0.159*x0.395**=0.063 |

0.417 |

0.151 |

No

mediation |

Innovation

adoption |

0.601** |

0.600**x0.395**=0.237 |

0.827 |

0.287 |

Partial

mediation |

According to Hair et al. [

70], a partial mediation of digital competence is observed for the relationship between innovation adoption and learning, confirming hypothesis H6.

The hypothesised positive effect on learning, moderated by digital competencies, is only supported for innovation adoption. Self-determined learning shows no impact neither on digital competence nor learning. Therefore, the supposed mediating effect of digital competence between self-determined motivation and learning (H5) is rejected.

Table 11 provides the conclusion of the investigated hypothesis.

5. Discussion

Digital transformation has a significant impact on the labour market [

71]. Maazmi et al. pointed out that an educated and adaptable workforce is a critical success factor for effective digital transformation [

72]. In recent papers, knowledge, skills, and competencies have often been used synonymously [

2,

73,

74,

75], lacking clear definitions or distinctions. Competence and learning are highlighted as essential prerequisites for digital transformation, yet concrete concepts and measurements are rare [

76,

77]. Therefore, this study helps close this gap by operationalising the developed concepts.

The provided measures are internally consistent and reliable, as demonstrated by the analysis of the outer model. The inner model analysis highlights the assumed relationship between innovation adoption, digital competencies, and learning. The results align with other studies [

8,

54,

78]. De Vries et al. created a heuristic innovation framework for the public sector. Like the measured items of the innovation construct in this study, innovation characteristics were supplemented by individual factors [

22]. Individual participation must be fostered to establish learning and using new technological innovations effectively [

83]. Talwar et al. [

79] emphasise the importance of engaging all stakeholders, as digitalisation strategies may fail due to resistance to innovation adoption. Companies must reconfigure digital competencies [

80] and encourage employees to innovate [

81].

We examined self-determined motivation and innovation adoption as fundamental theories and discussed them, confirming the hypothesised impact of innovation adoption on digital competencies. The independent variable innovation adoption shows a significant connection to digital competence (path coefficient 0.600 / p-value 0.000) and learning (path coefficient 0.601 / p-value 0.000); however, the expected positive effect of self-determined motivation could not be confirmed (0.159 / p-value 0.086 for digital competence, 0.140 / p-value 0.111 for learning). This absence of a statistically significant effect on digital competence and learning outcomes challenges the assumption derived from Self-determination Theory (SDT) that motivation drives workplace engagement and competence acquisition [

27]. Despite this theoretical grounding, our findings reveal that self-determined motivation alone cannot facilitate digital upskilling or promote learning in digital transformation contexts. This result contributes to the ongoing discussion since recent literature suggests that autonomy and intrinsic motivation must be embedded within a broader system of enablers (e.g. organisational support and structured workplace training offerings)[

82,

83,

84]. In fast-paced digital environments, where employees face continuous disruptions and novel technologies, motivation can be undermined by a lack of perceived support; where individuals are provided with opportunities to participate and learn safely, Gagné postulated that motivation might not translate into performance if individuals perceive their abilities or external resources as insufficient [

85].

Our results indicate that individuals will likely develop the necessary competencies and establish learning if they adopt innovation. Beyond innovation, other external factors appear to be more influential in developing digital competence than individual motivation. From a systems perspective, organisations function as open, adaptive entities that continuously evolve in response to technological advancements and workforce development needs. Our findings demonstrate that individual adoption of innovation is crucial for acquiring digital competencies, reinforcing the necessity of early engagement with emerging technologies. Employees' ability to integrate new digital competence is not solely reliant on their intrinsic motivation, indicating the influence of external system-based enablers, such as organisational support, infrastructure, and training initiatives. This emphasises the need for a change management system that embeds digital learning frameworks and facilitates structured workforce adaptation.

6. Conclusions

Digital transformation is a systemic process that requires organisations to develop interconnected frameworks for learning, innovation, and adaptation. Based on our results, we reflect on the current transitional state of digital work environments, where the uncertainty of new technologies challenges motivation as an antecedent for learning in organisational contexts. This underscores the need for change management that embeds structured learning opportunities and support mechanisms, urging practitioners to reconsider learning strategies and shifting to a holistic model that integrates individual, organisational and technological factors. It is indispensable for organisations to transform their current human capital towards new knowledge and mindsets with sustained learning. This study investigated the effects and relationships of motivation, innovation adoption, digital competencies, and learning as relevant factors in digital transformation. The results confirm the hypothesised mechanism of innovation adoption as a prerequisite to building digital competencies, which results in improved learning.

Of course, this study has its limitations. The relatively small sample size of 152 respondents does not allow for generalised results, but it is suitable for getting feedback and improving the questionnaire. The result might be biased due to the author's social network, which mainly comprises persons working in educational contexts or healthcare. This is acceptable; since the aim was to test the developed measures and construct, it was placed on social media for convenient access.

The results of this study are a starting point for a further research agenda. There is a need for more nuanced conceptual models to explore the interplay between intrinsic and extrinsic drivers in competence development. Longitudinal designs and industry-specific samples could provide deeper insight into how motivational dynamics evolve over time and in different digital maturity stages. Additionally, further research should investigate whether motivation moderates the relationship between innovation adoption and learning rather than acting as a direct antecedent. Empirically, future survey iterations could refine motivational items or contextualise them to better explain the relationships and effects on learning. A more diversified sample regarding sector, region and culture would increase the external validity.

This paper concludes with several contributions, which can be summarised in three ways. First, it enhances knowledge by testing the Self-Determination Theory (SDT) in digital work environments. Contrary to theoretical assumptions, the findings indicate that Self-determined motivation is insufficient to foster digital competence development and learning. External factors, such as organisational requirements and environmental conditions, appear more influential. Second, the study extends the Diffusion of Innovation Theory by introducing digital competencies as a key mediating variable in innovation adoption, emphasising that competence acquisition is critical for successful digital transformation. Third, it contributes to learning theory by proposing that organisations must understand the paths to establish sustained learning as a significant aspect of organisational adaptability to navigate digital transformation effectively. It has practical implications and advises managers to integrate employees and design training methods to develop content independently, with uncomplicated access and testing options.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, methodology, data collection and analysis, writing—original draft preparation: S.S.; writing—review and editing, supervision: I.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Internal and External consolidation of the University of Latvia, No. 5.2.1.1.i.0/2/24/I/CFLA/007, grant number 71-20/386.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study, in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data, in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Howcroft D, Taylor P. ‘Plus ca change, plus la meme chose?’-researching and theorising the ‘new’ new technologies. New Technol Work Employ. 2014;29:1–8. [CrossRef]

- Ohlert C, Giering O, Kirchner S. Who is leading the digital transformation? Understanding the adoption of digital technologies in Germany. New Technol Work Employ. 2022;37:445–68. [CrossRef]

- Ehlers U-D. Future Skills. Wiesbaden: Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden; 2020.

- Venkatesh, Morris, Davis, Davis. User Acceptance of Information Technology: Toward a Unified View. MIS Quarterly. 2003;27:425. [CrossRef]

- Dirsehan T, Can C. Examination of trust and sustainability concerns in autonomous vehicle adoption. Technol Soc. 2020;63:101361. [CrossRef]

- Oberländer M, Beinicke A, Bipp T. Digital competencies: A review of the literature and applications in the workplace. Comput Educ. 2020;146:103752. [CrossRef]

- Hartmann J, Heckner M, Plach U. Future Skills bei Studierenden - Messung und Einflussfaktoren . Die Neue Hochschule. 2023;:24–7. [CrossRef]

- van Laar E, van Deursen AJAM, van Dijk JAGM, de Haan J. Determinants of 21st-Century Skills and 21st-Century Digital Skills for Workers: A Systematic Literature Review. SAGE Open. 2020;10. [CrossRef]

- Carretero S, Vuorikari R, Punie Y. The Digital Competence Framework for Citizens. 2017.

- Suessenbach F, Winde M, Klier J, Kirchherr J. Future Skills 2021. 2021.

- Goldin C, Katz LF. The race between education and technology. harvard university press; 2009.

- Vial G. Understanding digital transformation: A review and a research agenda. The Journal of Strategic Information Systems. 2019;28:118–44. [CrossRef]

- Ellström D, Holtström J, Berg E, Josefsson C. Dynamic capabilities for digital transformation. Journal of Strategy and Management. 2022;15:272–86. [CrossRef]

- Kang HY, Kim HR. Impact of blended learning on learning outcomes in the public healthcare education course: a review of flipped classroom with team-based learning. BMC Med Educ. 2021;21:78. [CrossRef]

- Wintgen M, Krehl A, Heß M. Nachhaltiges Lernen durch Lehr- und Forschungsprojekt an der Hochschule Niederrhein. Die Neue Hochschule. 2023;:28–31. [CrossRef]

- Crossan MM, Lane HW, White RE, Djurfeldt L. ORGANIZATIONAL LEARNING: DIMENSIONS FOR A THEORY. The International Journal of Organizational Analysis. 1995;3:337–60. [CrossRef]

- Fiol CM, Lyles MA. Organizational Learning. Academy of Management Review. 1985;10:803–13. [CrossRef]

- Fiol CM, Lyles MA. Organizational Learning. Academy of Management Review. 1985;10:803–13. [CrossRef]

- Golembiewski RT. Organizational Leaming: A Theory of Action Perspective. J Appl Behav Sci. 1979;15:542–8. [CrossRef]

- Argyris C. Learning and Teaching: A Theory of Action Perspective. Journal of Management Education. 1997;21:9–26. [CrossRef]

- Starbuck WH, Greve A, Hedberg BLT. Responding to Crises. Journal of Business Administration. 1978;:111–37.

- De Vries H, Bekkers V, Tummers L. Innovation in the Public Sector: A Systematic Review and Future Research Agenda. Public Adm. 2016;94:146–66. [CrossRef]

- Ivaldi S, Scaratti G, Fregnan E. Dwelling within the fourth industrial revolution: organizational learning for new competences, processes and work cultures. Journal of Workplace Learning. 2022;34:1–26. [CrossRef]

- Lachman SJ. Learning is a Process: Toward an Improved Definition of Learning. J Psychol. 1997;131:477–80. [CrossRef]

- Ivory C, Sherratt F, Casey R, Watson K. Getting caught between discourse(s): hybrid choices in technology use at work. New Technol Work Employ. 2020;35:80–96. [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli W. Engaging Leadership: How to Promote Work Engagement? Front Psychol. 2021;12. [CrossRef]

- Deci EL, Ryan RM. Intrinsic Motivation and Self-Determination in Human Behavior. Boston, MA: Springer US; 1985.

- Ng JYY, Ntoumanis N, Thøgersen-Ntoumani C, Deci EL, Ryan RM, Duda JL, et al. Self-Determination Theory Applied to Health Contexts. Perspectives on Psychological Science. 2012;7:325–40. [CrossRef]

- Ehlers U-D. Future Skills-The Key to Changing Higher Education. Project Next Skills. 2020. www.NextSkills.org.

- Deci EL, Olafsen AH, Ryan RM. Self-Determination Theory in Work Organizations: The State of a Science. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior. 2017;4:19–43. [CrossRef]

- Gagné M. The Oxford Handbook of Work Engagement, Motivation, and Self-Determination Theory. 2014.

- Rogers EM. Diffusion of Innovations. New York: Free Press; 1962.

- Cain Mary, Mittman Robert, Institute for the Future., California HealthCare Foundation. Diffusion of innovation in health care. California Healthcare Foundation; 2002.

- Robinson L. A summary of diffusion of innovations. 2009.

- Varadarajan R. Innovation, Innovation Strategy, and Strategic Innovation. In: Innovation and Strategy. Emerald Publishing Limited; 2018. p. 143–66. [CrossRef]

- Ullrich A, Reißig M, Niehoff S, Beier G. Employee involvement and participation in digital transformation: a combined analysis of literature and practitioners’ expertise. Journal of Organizational Change Management. 2023;36:29–48. [CrossRef]

- Augier M, Teece DJ. Dynamic Capabilities and the Role of Managers in Business Strategy and Economic Performance. Organization Science. 2009;20:410–21. [CrossRef]

- Council of the European Union. Council Recommendation of 22 May 2018 on key competences for lifelong learning. 2018.

- European Commission, Centre JR, Vuorikari R, Kluzer S, Punie Y. DigComp 2.2, The Digital Competence framework for citizens – With new examples of knowledge, skills and attitudes. Publications Office of the European Union; 2022.

- Stofkova J, Poliakova A, Stofkova KR, Malega P, Krejnus M, Binasova V, et al. Digital Skills as a Significant Factor of Human Resources Development. Sustainability (Switzerland). 2022;14. [CrossRef]

- Goulart VG, Liboni LB, Cezarino LO. Balancing skills in the digital transformation era: The future of jobs and the role of higher education. Industry and Higher Education. 2022;36:118–27. [CrossRef]

- Biggins D, Holley D, Evangelinos G, Zezulkova M. Digital Competence and Capability Frameworks in the Context of Learning, Self-Development and HE Pedagogy. 2017. p. 46–53. [CrossRef]

- Dwivedi YK, Balakrishnan J, Das R, Dutot V. Resistance to innovation: A dynamic capability model based enquiry into retailers’ resistance to blockchain adaptation. J Bus Res. 2023;157:113632. [CrossRef]

- Arranz N, Arroyabe MF, Li J, de Arroyabe JCF. An integrated model of organisational innovation and firm performance: Generation, persistence and complementarity. J Bus Res. 2019;105:270–82. [CrossRef]

- Audretsch DB, Belitski M. Knowledge complexity and firm performance: evidence from the European SMEs. Journal of Knowledge Management. 2021;25:693–713. [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff PM, MacKenzie SB, Lee J-Y, Podsakoff NP. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology. 2003;88:879–903. [CrossRef]

- Lee J, Song H-D, Hong A. Exploring Factors, and Indicators for Measuring Students’ Sustainable Engagement in e-Learning. Sustainability. 2019;11:985. [CrossRef]

- Dörner O, Rundel S. Organizational Learning and Digital Transformation: A Theoretical Framework. In: Digital Transformation of Learning Organizations. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2021. p. 61–75. [CrossRef]

- Meske C, Junglas I. Investigating the elicitation of employees’ support towards digital workplace transformation. Behaviour & Information Technology. 2021;40:1120–36. [CrossRef]

- Roca JC, Gagné M. Understanding e-learning continuance intention in the workplace: A self-determination theory perspective. Comput Human Behav. 2008;24:1585–604. [CrossRef]

- Raman R, B S, G V, Vachharajani H, Nedungadi P. Adoption of online proctored examinations by university students during COVID-19: Innovation diffusion study. Educ Inf Technol (Dordr). 2021;26:7339–58. [CrossRef]

- Call DR, Herber DR. Applicability of the diffusion of innovation theory to accelerate model-based systems engineering adoption. Systems Engineering. 2022;25:574–83. [CrossRef]

- Othman A, Al Mutawaa A, Al Tamimi A, Al Mansouri M. Assessing the Readiness of Government and Semi-Government Institutions in Qatar for Inclusive and Sustainable ICT Accessibility: Introducing the MARSAD Tool. Sustainability (Switzerland). 2023;15. [CrossRef]

- Bikse V, Lusena-Ezera I, Rivza P, Rivza B. The development of digital transformation and relevant competencies for employees in the context of the impact of the covid-19 pandemic in latvia. Sustainability (Switzerland). 2021;13. [CrossRef]

- National Center for O*NET Development by the U.S. Department of Labor E and TA. O*Net Resource Center. 2023. https://www.onetcenter.org/overview.html. Accessed 17 Dec 2023. [CrossRef]

- Roemer L, Lewis P, Rounds J. The German O*NET Interest Profiler Short Form. Psychological Test Adaptation and Development. 2023;4:156–67. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen HTT, Pham HST, Freeman S. Dynamic capabilities in tourism businesses: antecedents and outcomes. Review of Managerial Science. 2023;17:1645–80. [CrossRef]

- Lee J, Song H-D, Hong A. Exploring Factors, and Indicators for Measuring Students’ Sustainable Engagement in e-Learning. Sustainability. 2019;11:985. [CrossRef]

- Mergel I, Edelmann N, Haug N. Defining digital transformation: Results from expert interviews. Gov Inf Q. 2019;36:101385. [CrossRef]

- Iyanna S, Kaur P, Ractham P, Talwar S, Najmul Islam AKM. Digital transformation of healthcare sector. What is impeding adoption and continued usage of technology-driven innovations by end-users? J Bus Res. 2022;153:150–61. [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff PM, Podsakoff NP, Williams LJ, Huang C, Yang J. Common Method Bias: It’s Bad, It’s Complex, It’s Widespread, and It’s Not Easy to Fix. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior. 2024;11:17–61. [CrossRef]

- Navarro D, Foxcroft D. Learning statistics with jamovi: a tutorial for psychology students and other beginners. 2019.

- Hair JF, Ringle CM, Sarstedt M. PLS-SEM: Indeed a Silver Bullet. Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice. 2011;19:139–52. [CrossRef]

- Montoya AK, Edwards MC. The Poor Fit of Model Fit for Selecting Number of Factors in Exploratory Factor Analysis for Scale Evaluation. Educ Psychol Meas. 2021;81:413–40. [CrossRef]

- Alojairi A, Akhtar N, Ali HM, Basiouni AF. Assessing Canadian business IT capabilities for online selling adoption: A Net-Enabled Business Innovation Cycle (NEBIC) perspective. Sustainability (Switzerland). 2019;11. [CrossRef]

- Ab Hamid MR, Sami W, Mohmad Sidek MH. Discriminant Validity Assessment: Use of Fornell & Larcker criterion versus HTMT Criterion. J Phys Conf Ser. 2017;890:012163. [CrossRef]

- Hair JF, Hult GTM, Ringle CM, Sarstedt M, Danks NP, Ray S. Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) Using R. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2021. [CrossRef]

- Akinwande MO, Dikko HG, Samson A. Variance Inflation Factor: As a Condition for the Inclusion of Suppressor Variable(s) in Regression Analysis. Open J Stat. 2015;05:754–67. [CrossRef]

- Sidhu A, Bhalla P, Zafar S. Mediating effect and review of its statistical measures. Empir Econ Lett. 2021;20:29–40.

- Hair Junior JF, Hult GTM, Ringle CM, Sarstedt M. A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM). Los Angeles: SA. 2014. [CrossRef]

- Dengler K, Matthes B. The impacts of digital transformation on the labour market: Substitution potentials of occupations in Germany. Technol Forecast Soc Change. 2018;137:304–16. [CrossRef]

- Al Maazmi A, Piya S, Araci ZC. Exploring the Critical Success Factors Influencing the Outcome of Digital Transformation Initiatives in Government Organizations. Systems. 2024;12:524. [CrossRef]

- Troise C, Tani M, Matricano D, Ferrara E. Guest editorial: Digital transformation, strategic management and entrepreneurial process: dynamics, challenges and opportunities. Journal of Strategy and Management. 2022;15:329–34. [CrossRef]

- Tjin A Tsoi SLNM, de Boer A, Croiset G, Koster AS, van der Burgt S, Kusurkar RA. How basic psychological needs and motivation affect vitality and lifelong learning adaptability of pharmacists: a structural equation model. Advances in Health Sciences Education. 2018;23:549–66. [CrossRef]

- Bikse V, Lusena-Ezera I, Rivza P, Rivza B. The Development of Digital Transformation and Relevant Competencies for Employees in the Context of the Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic in Latvia. Sustainability. 2021;13:9233. [CrossRef]

- Aggestam L, Svensson A. How digital applications can facilitate knowledge sharing in health care. The Learning Organization. 2025;32:58–74. [CrossRef]

- Banerjee P, Sharma N. Digital transformation and talent management in industry 4.0: a systematic literature review and the future directions. The Learning Organization. 2024;ahead-of-p ahead-of-print. [CrossRef]

- Wiśniewska S, Wiśniewski K, Szydło R. The Relationship between Organizational Learning at the Individual Level and Perceived Employability: A Model-Based Approach. Sustainability. 2021;13:7561. [CrossRef]

- Talwar S, Talwar M, Kaur P, Dhir A. Consumers’ resistance to digital innovations: A systematic review and framework development. Australasian Marketing Journal. 2020;28:286–99. [CrossRef]

- Shakina E, Parshakov P, Alsufiev A. Rethinking the corporate digital divide: The complementarity of technologies and the demand for digital skills. Technol Forecast Soc Change. 2021;162:120405. [CrossRef]

- Nylén D, Holmström J. Digital innovation strategy: A framework for diagnosing and improving digital product and service innovation. Bus Horiz. 2015;58:57–67. [CrossRef]

- Kreuder A, Frick U, Rakoczy K, Schlittmeier SJ. Digital competence in adolescents and young adults: a critical analysis of concomitant variables, methodologies and intervention strategies. Humanit Soc Sci Commun. 2024;11:48. [CrossRef]

- Alnasrallah W, Saleem F. Determinants of the Digitalization of Accounting in an Emerging Market: The Roles of Organizational Support and Job Relevance. Sustainability (Switzerland). 2022;14. [CrossRef]

- Harteis C, Goller M, Caruso C. Conceptual Change in the Face of Digitalization: Challenges for Workplaces and Workplace Learning. Front Educ (Lausanne). 2020;5. [CrossRef]

- Gagné M. The Oxford handbook of work engagement, motivation, and self-determination theory. Oxford University Press; 2014.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).