1. Introduction

During the clinical application of magnetic nanoparticle hyperthermia MNH, it is desirable to have complete knowledge of the temperature distribution for achieving the therapeutic tumor temperature range (41–45°C) [

1]. Invasive temperature measurements can provide information on the tissue temperature at discrete points only when the number of probes that can be implanted is restricted by patient tolerance and practical aspects, and thus the tissue temperature knowledge is limited [

2]. Therefore, a mathematical model for calculating tissue temperature during the treatment could prove valuable in complementing the invasive temperature measurements. The difference between applied (cause) and heat generated (effect) field, experimentally seen in vitro and in vivo, is overwhelming, and so is the heat distribution [

3]. Bridging theory and experiment in these cases requires new efforts in terms of heat measurement techniques and simulation approaches. Once a match between the latter two has been achieved, then there will be real chances of a routine use of MNH as a treatment adapted to the specific requirements of each cancer case. One of the main shortcomings of many in vitro models is the disregard of both tumor and body physiological conditions. For the sake of simplicity, biological media are usually considered to be a blood-flooded matrix composed of cells and interstitial space in physical models of hyperthermia [

4,

5].

Specific heat, thermal and electrical conductivities, mass density as well as the dielectric constant of the involved biological media (tumor and healthy tissue) must also be included in models and simulations. In the case of deep-seated tumors, the perturbing effects of bones (with low dielectric constant and thermal conductivity) are usually neglected due to the added complexity and their relatively limited influence on the heat transfer [

6,

7]. Another important element is vascularization. The heat transfer process greatly depends on blood perfusion, which is different for tumors and normal tissue. Moreover, bifurcations in vessels have an impact on the cooling effect of blood [

8]. Finally, the heat sources, i.e., MNPs, must be included so as to complete the basic tumor model of MNH. These may exhibit size distribution, which influences their magnetic properties and therefore the heat generation process, and spatial distribution, which determines the formation of “hot spots” and the uniformity of heat deposition in the tissue where MNPs are infused [

9,

10].

Heat transfer in living tissues is a complicated process because it involves a combination of thermal conduction in tissues, convection and perfusion of blood, and metabolic heat production [

11,

12,

13]. Over the years, several mathematical models have been developed to describe heat transfer within living biological tissues. These models have been widely used in the analysis of hyperthermia in cancer treatment, laser surgery, cryosurgery, cryopreservation, thermal comfort and many other applications. The most widely used bioheat model was introduced by Pennes in 1948 [

14,

15]. Pennes proposed a new simplified bioheat model to describe the effect of blood perfusion and metabolic heat generation on heat transfer within a living tissue. Since the landmark paper by Pennes, the bioheat transfer equation (BHTE) of his model has been widely used by many researchers for the analysis of bioheat transfer phenomena. For any MNP construct, thermal modelling is critical for understanding the heating efficacy at cellular level. The BHTE can be used to predict temperature profiles during local hyperthermia [

16,

17]. Despite the development of more accurate temperature prediction models, the BHTE can still be applied to almost every case of thermal modelling [

17]. When applying the BHTE, the specified magnetic field strength, frequency, background temperature, estimated average perfusion, MNP concentration, and distribution in the target tissue yield an energy term which is then used to estimate the power absorption and temperature distribution within the target region [

18,

19,

20].

Blood perfusion can be the dominant form of energy removal when considering heating processes. It assumes that the blood enters the control volume at some arterial temperature, and then comes to equilibrium at tissue temperature. Thus, as the blood leaves the control volume, it carries away the energy, and therefore acts as an energy sink in MPH treatment. In many works blood perfusion is considered as a constant value that is characteristic of the tissue [

11,

21,

22,

23]. In reality, blood perfusion is not static; it varies with temperature and time. Tumor microvasculature exhibits unique thermal responses compared to healthy tissues, with an initial hyperperfusion that may decline under prolonged hyperthermic conditions due to vascular collapse or functional impairments [

24,

25,

26]. Incorporating such complexities is crucial for accurately simulating the thermal interaction between magnetic nanoparticles and tumors. Here, we address this gap by integrating temperature- and time-dependent blood perfusion models into a computational framework for MNH simulations.

This study estimates the thermal dissipation of 15 nm magnetite nanoparticles subjected to an alternating magnetic field of 20 mT and 100 kHz using micromagnetic simulations, providing the energy loss parameters necessary for the analysis. The power dissipation was integrated into a bioheat transfer model, and the finite element method (FEM) was employed to solve the heat transfer equations and compute spatial and temporal temperature distributions within a spherical tumor surrounded by healthy tissue. The blood perfusion rates in both tumor and healthy tissues were modeled as dynamic functions of temperature and time, capturing the physiological variability inherent to the process. Prior to the application of MPH in patients, safety and effectiveness must be ensured with the generation of an accurate and reliable treatment plan. Consequently, the need for a numerical model that considers variables such as the tissues density, specific heat and thermal conductivity, metabolic heat generation and blood perfusion rate is of high importance. Our model takes into account all the suitable boundary conditions and, more importantly, should be utilized within the framework of BHTE Equation tailored to varied perfusion. Accurate treatment planning can allow for the generation of a temperature spatiotemporal distribution which can provide better visualization of the heat transfer present in the tumor region than single-point thermometry. Thermal modelling that is in agreement with physical temperature measurements can complement focal thermal monitoring. By incorporating temperature-dependent and time-dependent blood perfusion rates into the FEM framework, this work delivers a more accurate representation of thermal dynamics during MNH, offering critical insights into optimizing this therapy for effective and safe clinical applications.

2. Materials and Methods

To determine the hysteresis losses of magnetic nanoparticles (MNPs), a detailed micromagnetic numerical model was developed with OOMMF software [

27], assuming single-domain, spheroidal particles with identical material composition. The particles interact with one another via magnetostatic dipole–dipole interactions, which were incorporated into the simulation framework. The model simulates the behaviour of an ensemble of MNPs by numerically integrating the Landau-Lifshitz-Gilbert (LLG) [

28] equation to calculate their magnetic response under an alternating magnetic field. The energy losses

were evaluated by calculating the hysteresis loop area and multiplying it by the applied magnetic field frequency. For these simulations, the Fe

3O

4 MNPs were characterized by the following magnetic parameters: a damping coefficient alpha = 0.02, a saturation magnetization of bulk magnetite Ms = 480 kA/m , and a first-order cubic magnetocrystalline anisotropy constant K= −13.5 kJ/m

3 [

29]. The volume concentration of MNPs in the simulated environment was set to

= 1%, and the anisotropy axes of individual particles were randomly oriented to mimic realistic spatial distributions. Simulations were performed at initial temperature of 300 K to ensure a thermally consistent representation of the system. Field amplitude and frequency were chosen as to simulate realistic clinical conditions and were set to 20 mT and 100 kHz respectively.

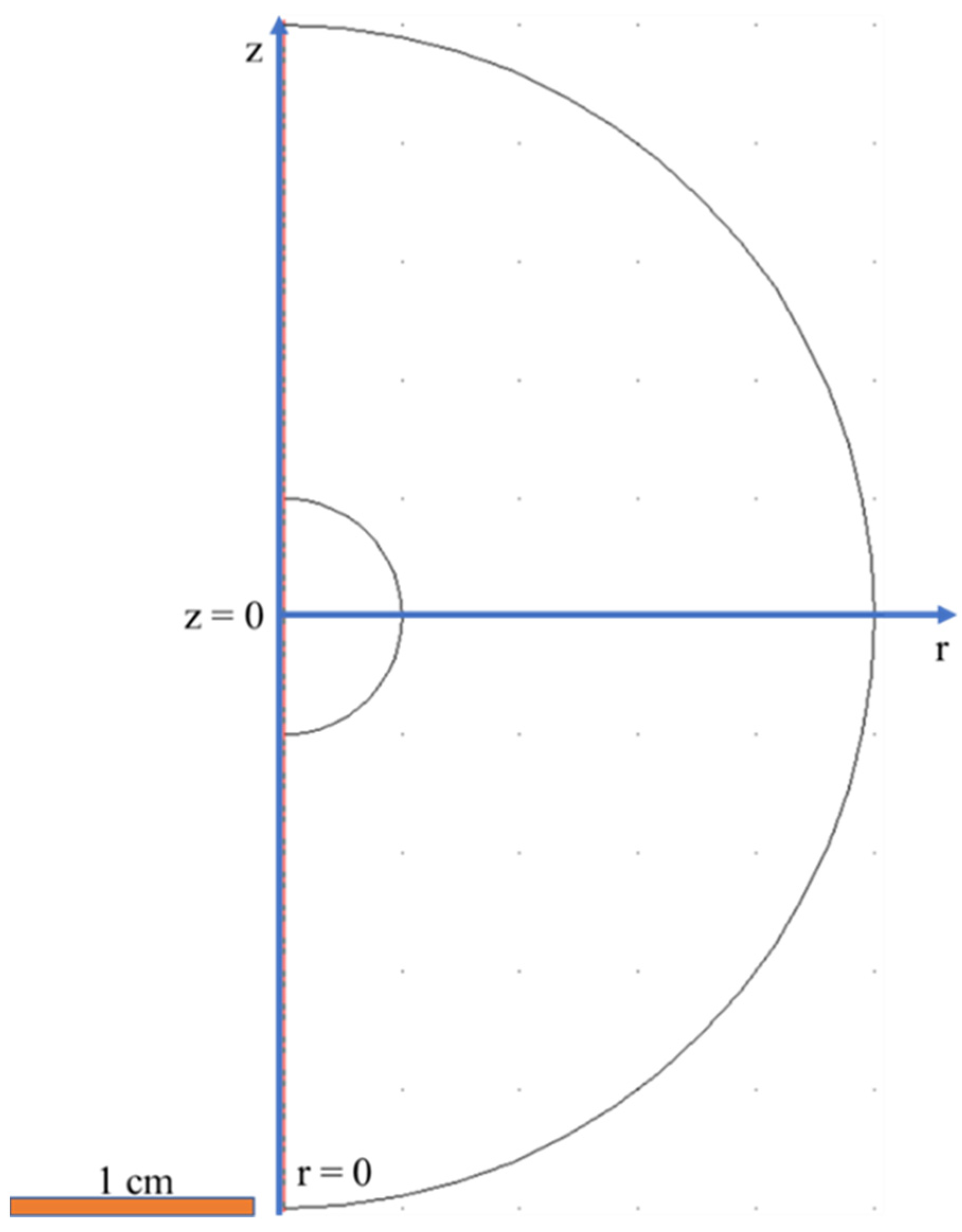

The finite element model (FEM) utilized in this study comprises a spherical tumor with a radius of 5 mm embedded within a healthy brain tissue region with a radius of 25 mm. This geometric configuration was adopted from the works by K. Maier-Hauff et al. [

30,

31]. The dimensions align with the realistic anatomical parameters observed in glioblastoma multiforme cases, enhancing the applicability of the model for clinically relevant scenarios. This configuration enables an accurate representation of the heat distribution within the tumor and surrounding healthy tissue during magnetic nanoparticle hyperthermia. In order to save computational time and space but simultaneously obtain accurate results for the realistic 3D space, we design our geometry in a 2D (r,z) axisymmetric model depicted in

Figure 1.

The heat transfer simulation was performed using COMSOL Multiphysics software [

32]. The time-dependent “Bioheat Τransfer” module is utilized to simulate the in vivo MNH scheme studied here. The governing Equation reads:

where

ρt,

ct,

T,

kt are density, specific heat, temperature and thermal conductivity of the tissue respectively. In addition,

Tb is the temperature of arterial blood,

Qmet is the metabolic heat generation in W/m

3 and

ρb,

cb,

ωb are density, specific heat and perfusion rate of blood respectively. Finally,

Qext is the energy deposition rate in W/m

3 which is generated by an external heating source (in our case the MNPs subjected to AC field) and is related to the MNPs hysteresis losses through:

Metabolic heat generation Qmet is usually very small compared to the external power deposition term Qext. It should be noted that metabolic heat generation is assumed to be homogeneously distributed throughout the tissue. The first term on the left part of Equation (1) describes the storage of thermal energy while the first term on the right is related to heat diffusion. The term cbρbωb(Tb − T), which accounts for the effects of blood perfusion, can be the dominant form of energy removal when considering heating processes. It assumes that the blood enters the control volume at some arterial temperature Tb, and then comes to equilibrium at tissue temperature. Thus, as the blood leaves the control volume, it carries away the energy, and therefore acts as an energy sink in MPH treatment. Power deposition due to eddy currents can be neglected due to the low amplitude and frequency of the applied alternating magnetic field (20 mT/100 kHz).

The thermophysical and other properties of the tumor and healthy tissue used for simulation are summarized in

Table 1. The properties of blood are summarized in

Table 2.

The simulations also adopt the temperature-dependent blood perfusion rate model introduced by Lang et al. [

35], for both the tumor, ω

b,tumor and the healthy tissue (ω

b,tissue) in (1/sec.). Those blood perfusion rates depend on the temperature in the following way:

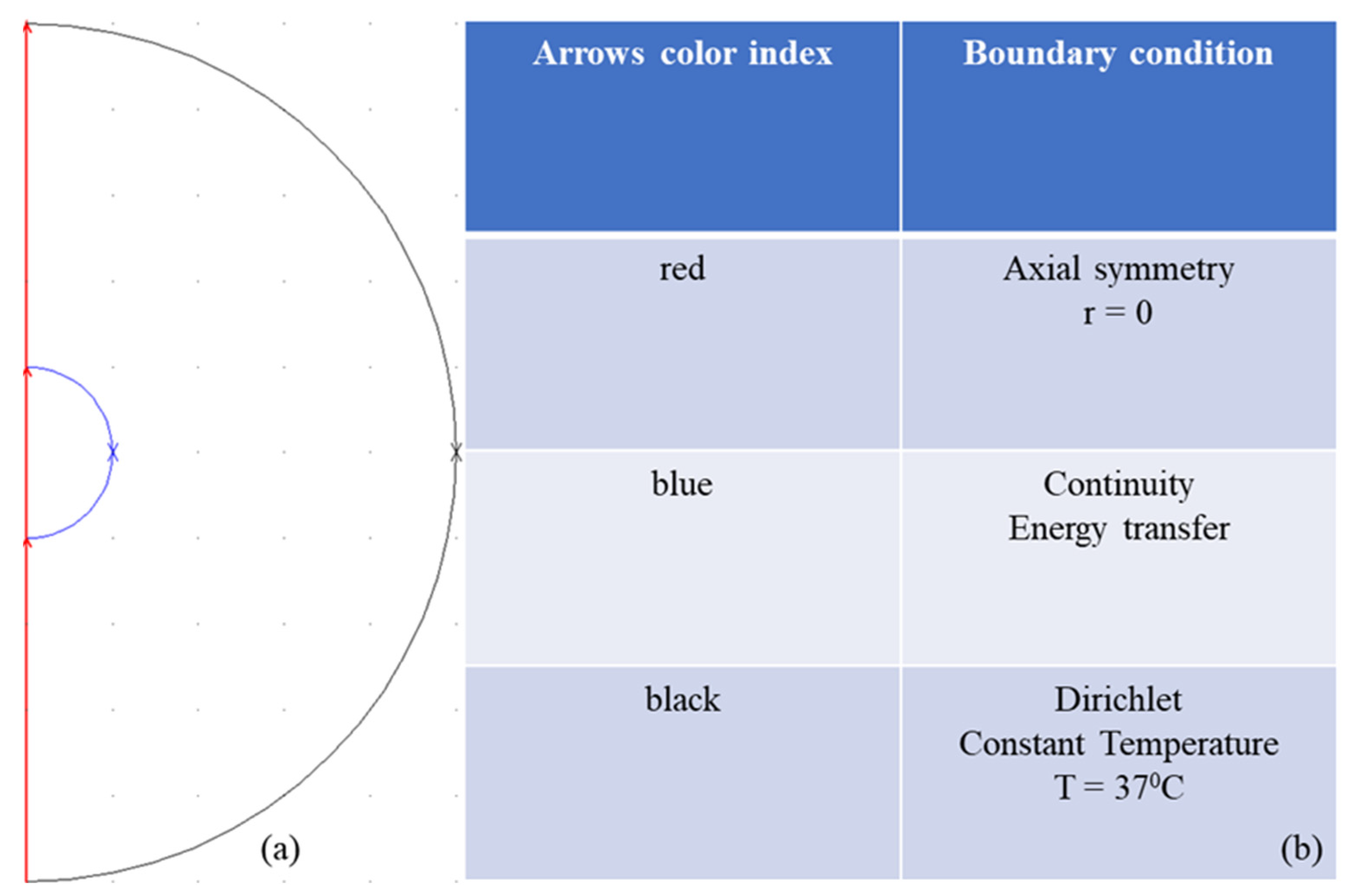

Under the “Initial Values” node, the normal body temperature of 37

0C (310.15 K) was set throughout the entire geometry. A general “Heat Source”

was added in the Tumor-MNPs composite domain, assuming that all the MNPs are uniformly dispersed within the tumor region, with a volume fraction of

. A “Temperature” node of constant temperature (Dirichlet boundary condition type) was selected to describe the conditions on the outer boundary of the healthy tissue. Assuming that a sufficient volume of healthy tissue spans between the heat source and the boundary, the metabolism and perfusion mechanisms should counterbalance the effect of the source, thus the temperature at the boundary should approximate the normal body temperature of 37

0C. Treatment time was equal to 3600 sec. (1 h). At tumor boundaries we set the continuity boundary condition. This boundary condition describes the energy transfer between the boundaries of the tumor and the external environment, which is the healthy tissue. The general relation that describes this, is the following:

where

n is the vector perpendicular to the boundary surface. This condition specifies that the heat flux in the normal direction is continuous across the boundary between material 1 (tumor) and material 2 (healthy tissue). The axial symmetry boundary condition is applied along the z-axis of the model. This condition is used in boundaries in order to reduce the overall size of the model and save system resources like CPU time and space. All the boundary conditions used are presented in

Figure 2.

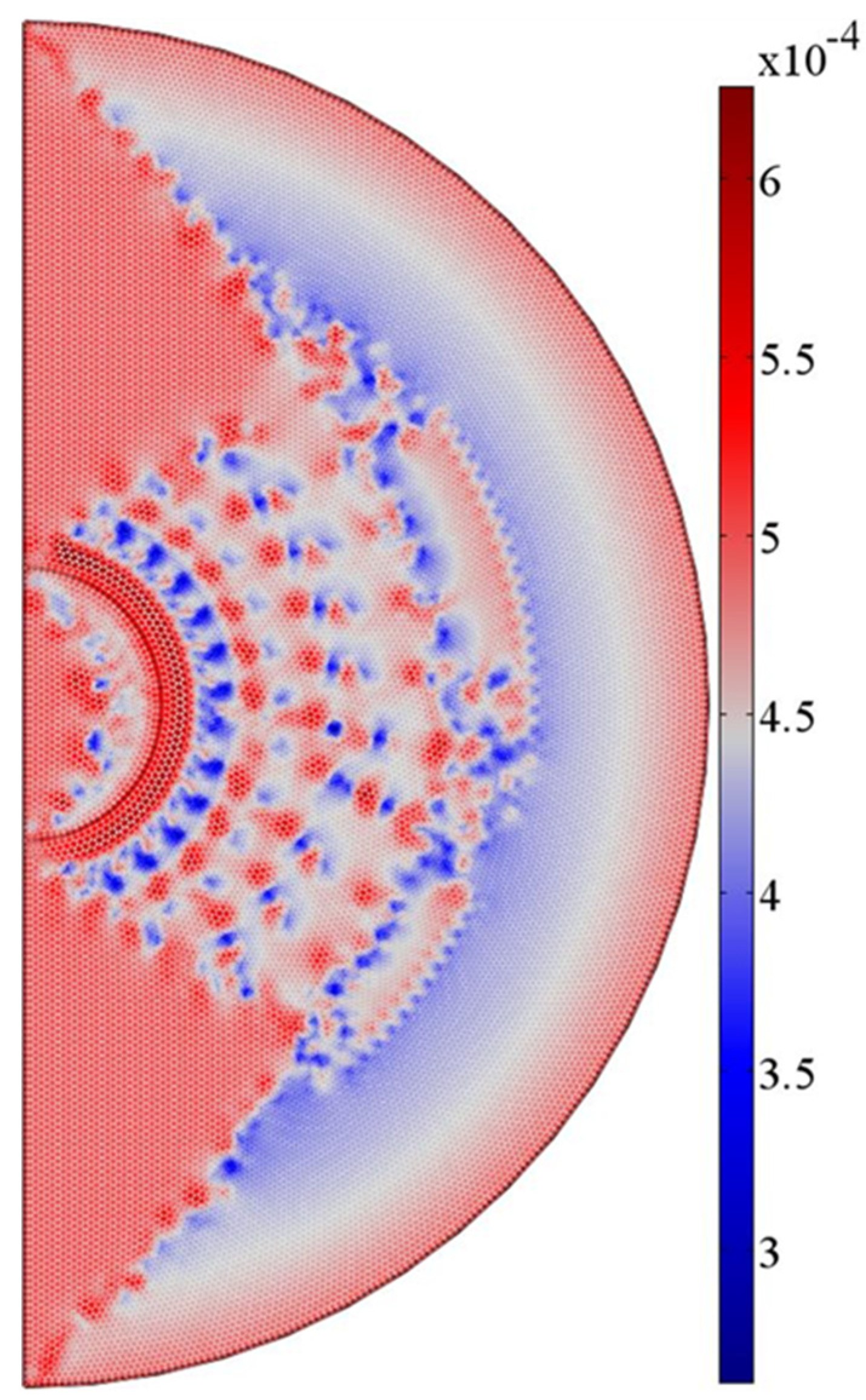

Since the model contains rotational symmetry, the computational domain can be represented in 2D using cylindrical coordinates. Because of the computation time saved by modelling in 2D, we can select a fine mesh that will provide extremely accurate results. An extra fine mesh was used throughout the entire geometry as shown in

Figure 3. It consisted of 11813 triangular domain elements and 586 boundary elements. The time-dependent study of 3,600 sec. is carried out for a time step of 0.1 seconds and a relative tolerance of 0.001. A direct time-dependent solver is used throughout the simulations that included 23,886 degrees of freedom (DOFs).

3. Results

3.1. Micromagnetic Simulation

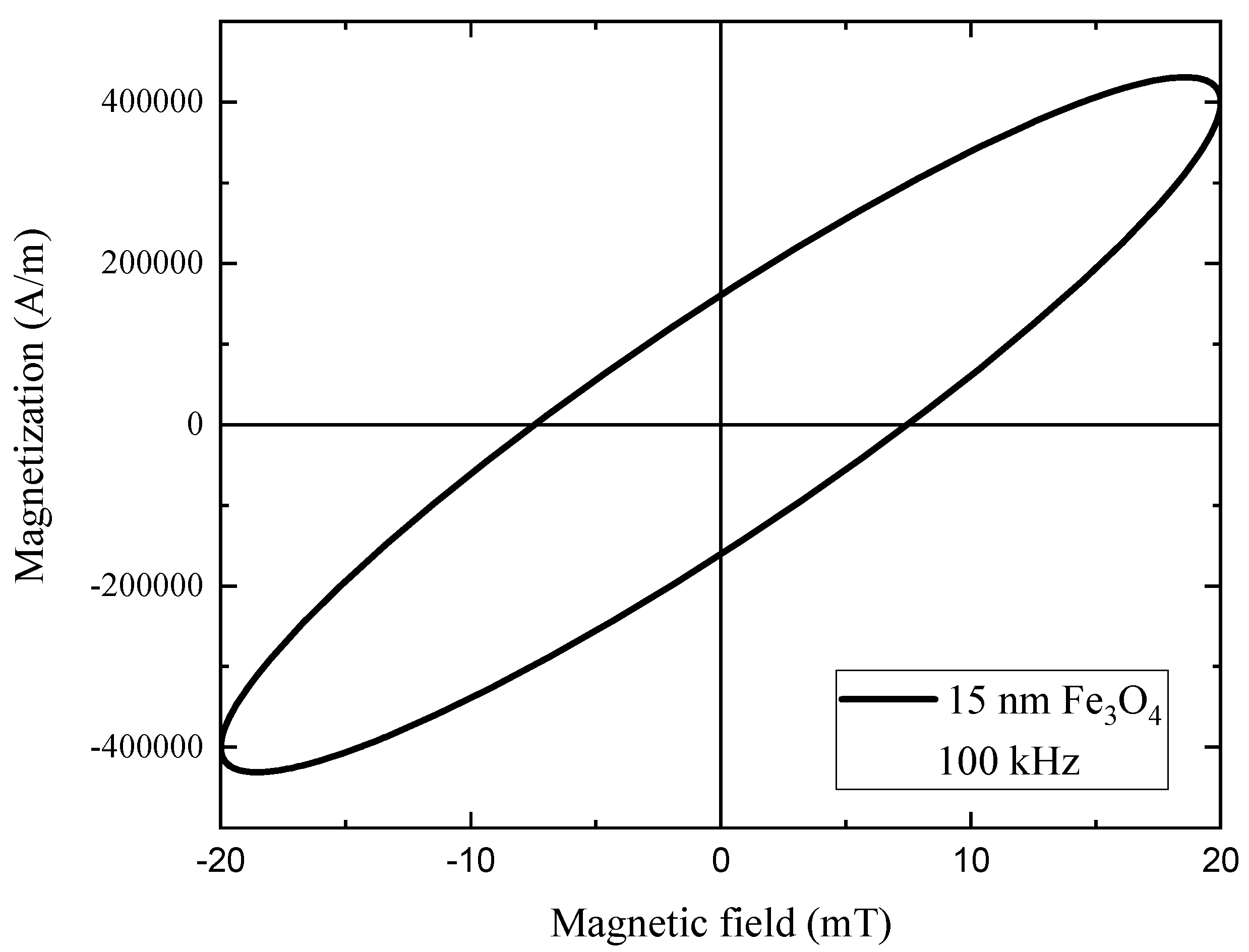

The hysteresis loop, depicted in figure 4, reflects the reduction in magnetization due to the nanoscale size of the particles compared to the bulk material [

36]. Furthermore, the low field of 20 mT cannot cause a complete saturated magnetization of the system of interacting nanoparticles since the characteristic field of the cubic anisotropy is as high as 2|K|/M_s = 60 mT, much higher than the coercive field obtained here (≈ 8 mT). By integrating the data of

Figure 4 we found that hysteresis loop area equals to 3.6 J/kg

MNPs. By multiplying this value to the driving frequency value, we found

.

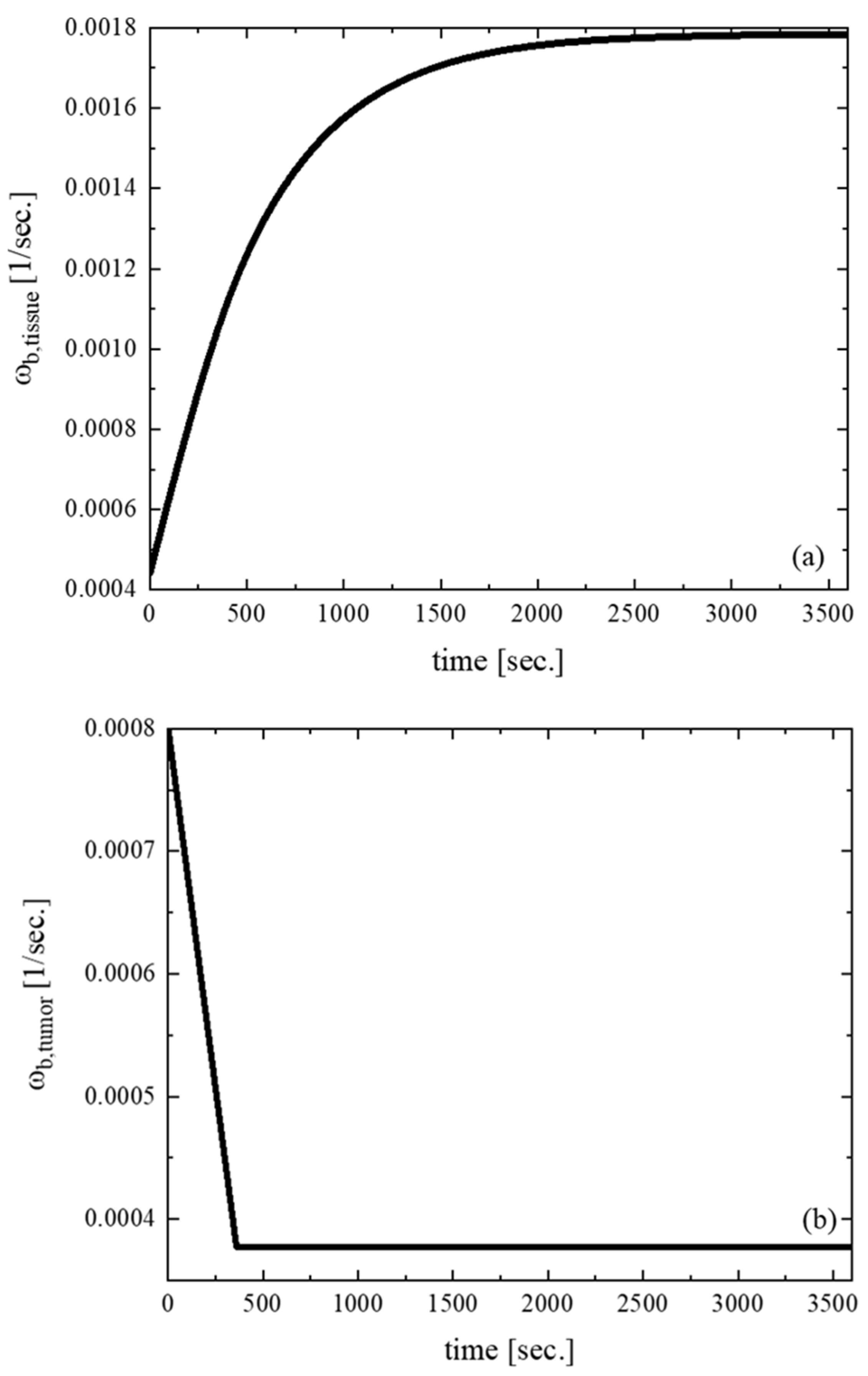

3.2. Blood Perfusion

After using COMSOL to numerically solve the time dependent Equation (1), we obtain the distributions of variables such as blood perfusion, temperature and MNPs volumetric power dissipation in order to appraise the validity of our method. First, we obtain the blood perfusion temporal distribution for the healthy tissue and tumor which is depicted in

Figure 5a,b respectively. The healthy tissue is characterized by a normal vascular system, which supplies the tissue with more blood as the temperature rises in order to extract heat. The vascular system of tumor is hypertrophic and consequently, at normal temperature, it provides greater blood flow. On the other hand, at higher temperatures the vascular system of tumor fails to increase the blood flow and therefore reduces it. Thus, it is easier to heat the tumor. This property is beneficial for the whole process of the in vivo MNH.

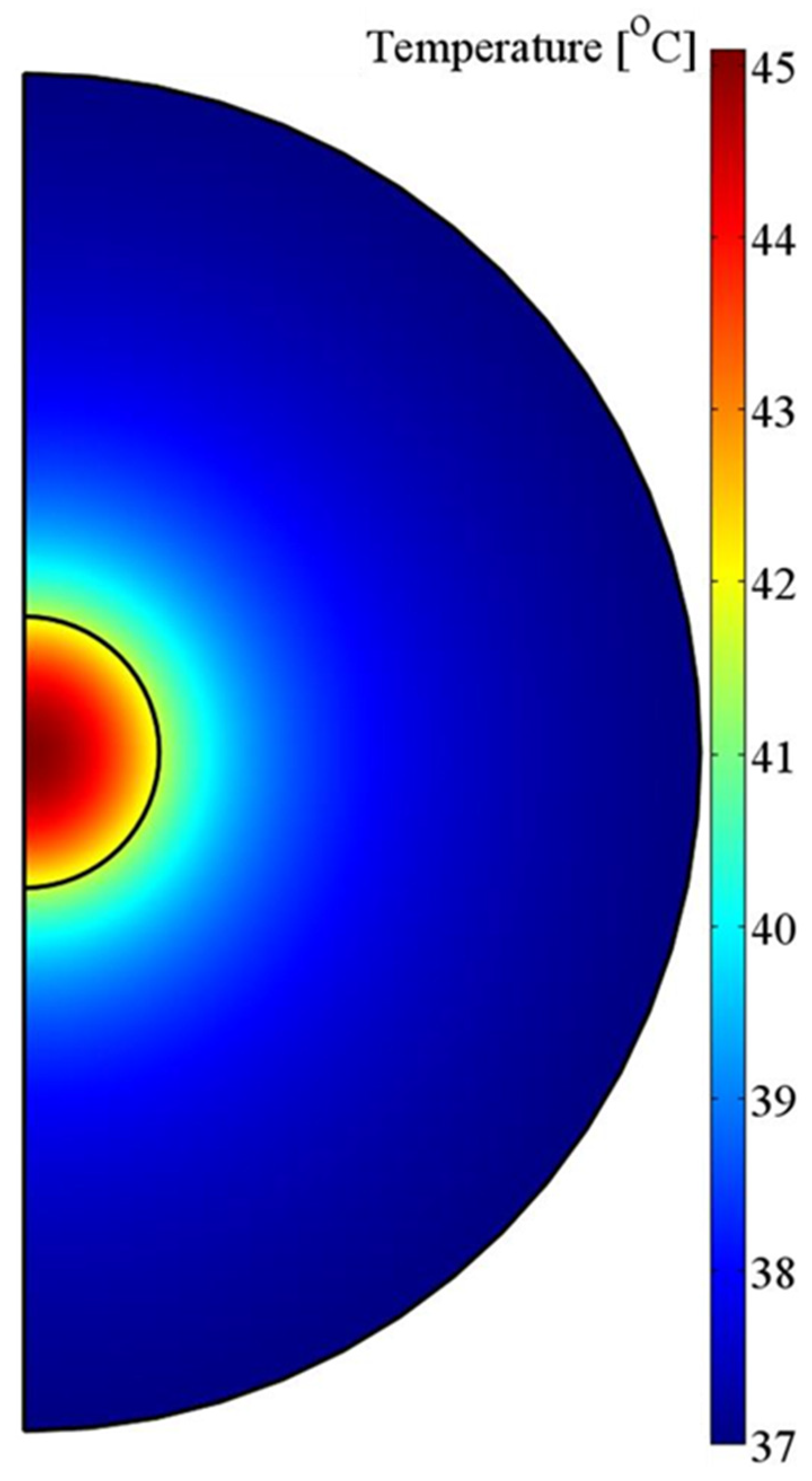

3.3. Heat Transfer

Then, we estimated Temperature distribution within the tumor volume. The heating source of the tumor are the MNPs with their losses given by equation (2). Since blood acts as a heat sink because of perfusion, an efficient amount of energy is required to attain an MNH appropriate temperature increase, which is illustrated in

Figure 6 after 3,600 sec. of MNH treatment.

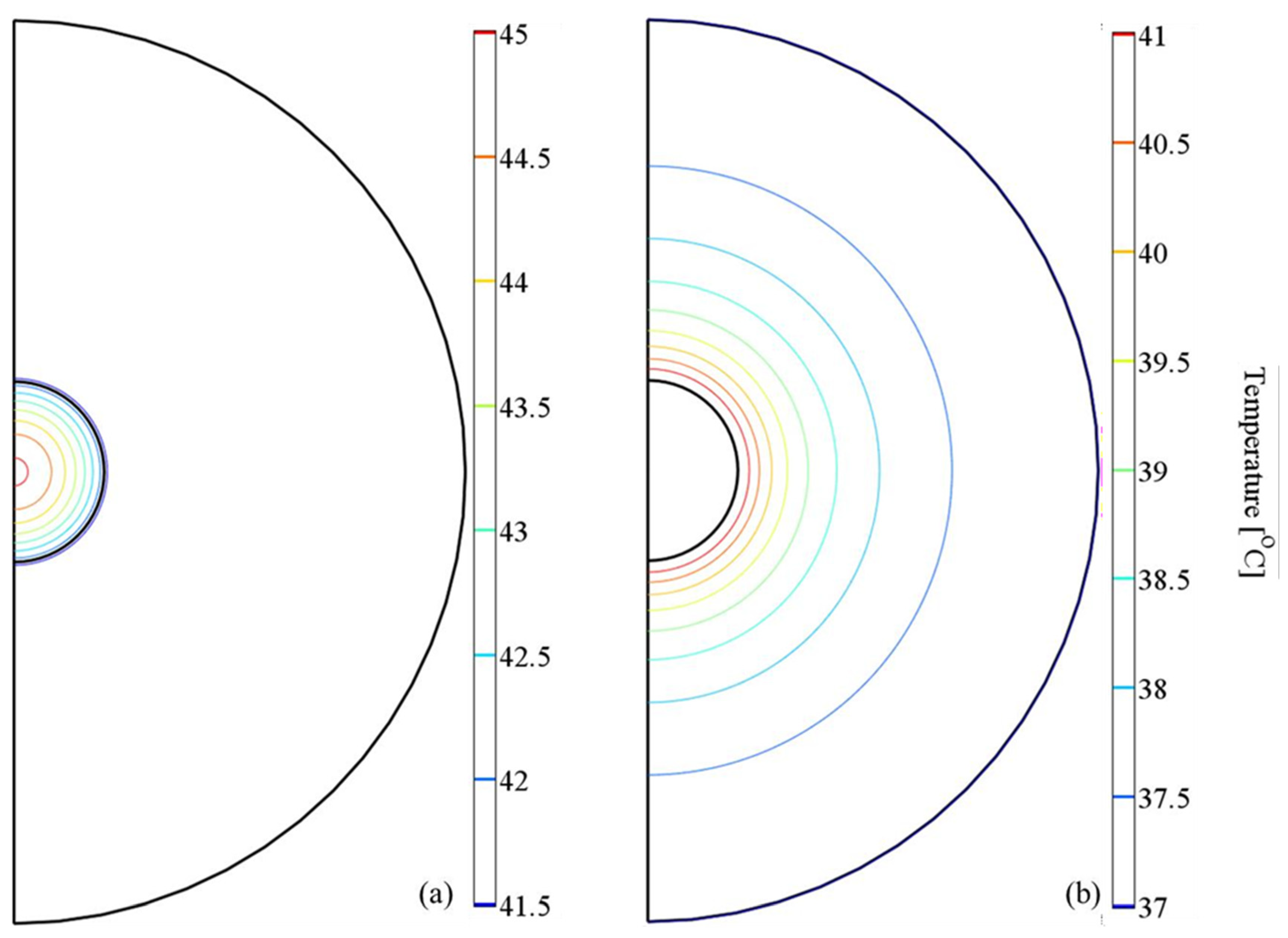

In order to prove the efficacy of our methodology, we present a contour temperature plot within the tumor volume in

Figure 7a. We see that the entire volume of the tumor enters the MNH window limits, i.e. between 41

0C to 45

0C, whereas tumor boundaries are above MNH threshold. On the other hand, temperature within the healthy tissue is not significantly increased, as illustrated in the contour temperature plot of

Figure 7b. The maximum temperature reached in healthy tissue volume is 41

0C. This temperature increase (ΔΤ = 4

0C) does not affect cellular mechanisms as has already been demonstrated in literature [

37].

To validate our method, temperature values attained both in the center and at the boundaries of the tumor are compared to the corresponding experimental temperature values obtained in a clinical studies [

30,

31] under the same particles (material, size, concentration) and field (amplitude and frequency) conditions. There the authors performed heating treatment to patients suffering from glioblastoma multiforme by intracranial injection of the magnetic fluid MFL AS (MagForce Nanotechnologies AG, Berlin, Germany [

38]), which is subject to European medical devices regulations [

39] and consisted of aminosilane coated magnetite nanoparticles (15 nm core size) dispersed in water. Temperature values attained both in the center and at the boundaries of the tumor are compared to the corresponding experimental temperature values obtained in [

30,

31] to evaluate our method. The results are presented in

Table 3 where the good agreement between experimentally measured and numerically calculated values is revealed.

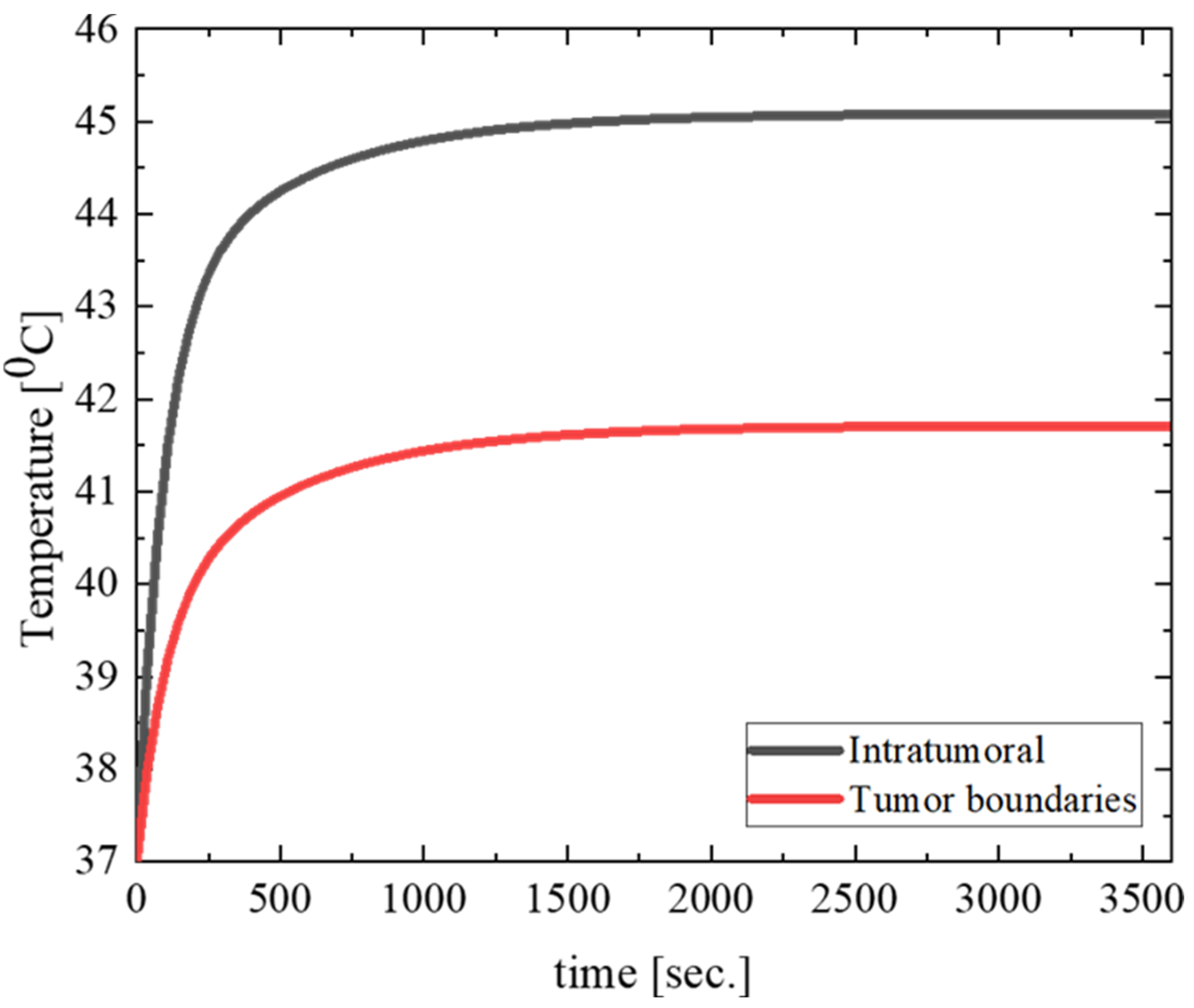

Time evolution of temperature in the center and tumor boundaries is also depicted in

Figure 8.

The results illustrated in

Figure 8 show a significant and rapid rise in temperature within the intratumoral region, which stabilizes after approximately 15 minutes, reaching a steady state. This elevated and sustained temperature is crucial for inducing thermal damage to tumor cells. Conversely, the tumor boundaries exhibit a slower rate of temperature increase and reach a lower steady-state temperature compared to the center. This gradient in temperature distribution can be attributed to the heat dissipation effects of surrounding healthy tissues, which have a more robust vascular response and blood perfusion rates. The distinct temperature profile highlights the efficiency of MNH in selectively heating the tumor core while sparing adjacent healthy tissue. Such differentiation in temperature dynamics between the tumor center and its periphery underscores the importance of the tumor's impaired vascular system, which limits heat dissipation. These characteristics ensure a therapeutically effective thermal dose to the tumor while minimizing potential thermal damage to the surrounding tissue. This behavior reaffirms the advantages of magnetic nanoparticle hyperthermia as a localized cancer treatment modality.

4. Discussion

This study investigates the thermal interaction between magnetic nanoparticles (MNPs) and a cancerous tumor using computational models to evaluate the impact of temperature- and time-dependent blood perfusion rates. The findings illustrate the complex interplay between nanoparticle heat dissipation, tissue perfusion, and tumor physiology, providing critical insights into the optimization of magnetic nanoparticle hyperthermia (MNH) for clinical cancer treatment. The results confirm that tumor tissues can be selectively heated during MNH due to their impaired vascular response, which contrasts with the robust blood perfusion system in healthy tissues. The tumor's hypertrophic vascular structure initially exhibits elevated blood perfusion compared to normal tissue. However, its inability to maintain this increase under hyperthermic conditions results in reduced heat dissipation, allowing for sustained temperature rise in the tumor core. These findings are consistent with previous studies that highlight the vulnerability of tumor vasculature to thermal stress, which enhances the therapeutic efficacy of hyperthermia treatments.

Micromagnetic simulations of 15 nm magnetite nanoparticles were used to accurately determine their thermal dissipation, incorporating realistic material properties such as saturation magnetization, damping coefficient, and anisotropy. The power dissipation derived from these simulations matches well with earlier studies using similar nanoparticle systems. The adoption of temperature- and time-dependent blood perfusion models in finite element simulations further advances the state-of-the-art by capturing dynamic physiological responses, addressing a critical limitation in previous literature that relied on static perfusion rates. From the bioheat transfer simulations, it is evident that the MNH treatment achieves therapeutic temperatures (41–45°C) in the tumor without overheating the surrounding healthy tissue. This selective heating highlights the potential of MNH to minimize adverse side effects, which is a persistent challenge in other cancer treatment modalities like chemotherapy and external beam radiotherapy. The use of realistic anatomical dimensions for the tumor and brain geometry, based on the work of Maier-Hauff et al. [

30,

31], ensures clinical relevance and applicability of the results to glioblastoma multiforme treatment scenarios. The findings also endorse the working hypothesis that the differential thermal and vascular responses of tumors and healthy tissues can be exploited to achieve precise and localized heating of tumors during MNH. However, several factors require further investigation. For example, nanoparticle distribution within the tumor and agglomeration effects could influence the overall heat generation, warranting more advanced modeling techniques. Similarly, the impacts of non-uniform tissue properties and variations in vascular density need to be explored to refine the predictive accuracy of computational models.

Future research should focus on validating these computational findings with experimental in vivo studies to establish robust correlations between modeling predictions and biological outcomes. Investigating the long-term effects of MNH treatment, including tumor recurrence and vascular recovery, would provide a more comprehensive understanding of its therapeutic potential. Furthermore, the combination of MNH with other treatment modalities, such as immunotherapy or targeted drug delivery, could open new avenues for enhancing therapeutic outcomes.

5. Conclusions

By employing the experimental conditions and MNPs parameters that were used in a clinical application of MNH found in literature, a bioheat transfer modelling was carried out in order to visualize the temperature profile within the biological tissues (tumor and healthy tissue). Simulations revealed that temperature increase and heating rate within the tumor are maintained in ideal therapeutic levels (within the moderate hyperthermia levels) without affecting thermally the healthy tissue. The results are also verified in literature and validate our technique.

The modelling of heat generation and transfer process in MNH will increase the understanding of physical phenomena and allow a successful transition of this technology from bench to bedside. In addition, modelling through simulation can be used in the planning of the MPH treatment and it also serves as a new alternative method for temperature mapping due to the difficulty in real-time clinical temperature measurement during the treatment. Conclusively, the beneficial role of modelling implementation in an in vivo MPH scheme can be illustrated through the following aspects:

MPH treatment can be optimized with respect to the heat application geometry by maximizing the therapeutic effect while minimizing unwanted side effects.

The outcome of the treatment can be evaluated based on model predictions.

It can also be used for extensive parametric studies in order to characterize the stability of various treatment parameters and conditions.

New treatment strategies can be proposed and evaluated.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.M.; methodology, N.M.; software, N.M. and S.M.; validation, N.M., V.T. and S.M.; formal analysis, N.M.; investigation, N.M., V.T. and S.M.; resources, N.M., V.T. and S.M.; data curation, N.M., V.T. and S.M; writing—original draft preparation, N.M.; writing—review and editing, N.M., V.T. and S.M; visualization, N.M., V.T. and S.M.; supervision, N.M., V.T.; project administration, N.M., V.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available in this article.

Acknowledgments

In this section, you can acknowledge any support given which is not covered.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Johannsen, M.; Gneveckow, U.; Taymoorian, K.; Thiesen, B.; Waldöfner, N.; Scholz, R.; Jung, K.; Jordan, A.; Wust, P.; Loening, S.A. Morbidity and Quality of Life during Thermotherapy Using Magnetic Nanoparticles in Locally Recurrent Prostate Cancer: Results of a Prospective Phase I Trial. Int. J. Hyperth. 2007, 23, 315–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saville, S.L.; Qi, B.; Baker, J.; Stone, R.; Camley, R.E.; Livesey, K.L.; Ye, L.; Crawford, T.M.; Thompson Mefford, O. The Formation of Linear Aggregates in Magnetic Hyperthermia: Implications on Specific Absorption Rate and Magnetic Anisotropy. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2014, 424, 141–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedayatnasab, Z.; Abnisa, F.; Daud, W.M.A.W. Review on Magnetic Nanoparticles for Magnetic Nanofluid Hyperthermia Application. Mater. Des. 2017, 123, 174–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Périgo, E.A.; Hemery, G.; Sandre, O.; Ortega, D.; Garaio, E.; Plazaola, F.; Teran, F.J. Fundamentals and Advances in Magnetic Hyperthermia. Appl. Phys. Rev. 2015, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Chen, C.; Wang, P.; Song, T. Mechanisms of Cellular Effects Directly Induced by Magnetic Nanoparticles under Magnetic Fields. J. Nanomater. 2017, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romeo, D.; Salieri, B.; Hischier, R.; Nowack, B.; Wick, P. An Integrated Pathway Based on in Vitro Data for the Human Hazard Assessment of Nanomaterials. Environ. Int. 2020, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, S.; Zhang, H.; Liu, Y.; Sun, F.; Yu, X.; Li, X.; Zhang, L.; Wang, L.; Mao, K.; Wang, G.; et al. Maximizing Specific Loss Power for Magnetic Hyperthermia by Hard-Soft Mixed Ferrites. Small 2018, 14, 1800135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yue, K.; Yu, C.; Lei, Q.; Luo, Y.; Zhang, X. Numerical Simulation of Effect of Vessel Bifurcation on Heat Transfer in the Magnetic Fluid Hyperthermia. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutz, S.; Hergt, R. Magnetic Nanoparticle Heating and Heat Transfer on a Microscale: Basic Principles, Realities and Physical Limitations of Hyperthermia for Tumour Therapy. Int. J. Hyperth. 2013. [CrossRef]

- Dutz, S.; Hergt, R. Magnetic Particle Hyperthermia - A Promising Tumour Therapy? Nanotechnology 2014. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spirou, S. V.; Basini, M.; Lascialfari, A.; Sangregorio, C.; Innocenti, C. Magnetic Hyperthermia and Radiation Therapy: Radiobiological Principles and Current Practice. Nanomaterials 2018, 8, 401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Socoliuc, V.; Peddis, D.; Petrenko, V.I.; Avdeev, M. V.; Susan-Resiga, D.; Szabó, T.; Turcu, R.; Tombácz, E.; Vékás, L. Magnetic Nanoparticle Systems for Nanomedicine—A Materials Science Perspective. Magnetochemistry 2020, 6, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obaidat, I.M.; Narayanaswamy, V.; Alaabed, S.; Sambasivam, S.; Muralee Gopi, C.V. V. Principles of Magnetic Hyperthermia: A Focus on Using Multifunctional Hybrid Magnetic Nanoparticles. Magnetochemistry 2019, 5, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PENNES, H.H. Analysis of Tissue and Arterial Blood Temperatures in the Resting Human Forearm. J. Appl. Physiol. 1948, 1, 93–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pennes, H.H. Analysis of Tissue and Arterial Blood Temperatures in the Resting Human Forearm. J. Appl. Physiol. 1998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giordano, M.A.; Gutierrez, G.; Rinaldi, C. Fundamental Solutions to the Bioheat Equation and Their Application to Magnetic Fluid Hyperthermia. Int. J. Hyperth. 2010, 26, 475–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bellizzi, G.; Bucci, O.M. On the Optimal Choice of the Exposure Conditions and the Nanoparticle Features in Magnetic Nanoparticle Hyperthermia. Int. J. Hyperth. 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louis, D.N.; Perry, A.; Reifenberger, G.; von Deimling, A.; Figarella-Branger, D.; Cavenee, W.K.; Ohgaki, H.; Wiestler, O.D.; Kleihues, P.; Ellison, D.W. The 2016 World Health Organization Classification of Tumors of the Central Nervous System: A Summary. Acta Neuropathol. 2016. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le, T.A.; Bui, M.P.; Yoon, J. Theoretical Analysis for Wireless Magnetothermal Deep Brain Stimulation Using Commercial Nanoparticles. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, A.; Attaluri, A.; Mallipudi, R.; Cornejo, C.; Bordelon, D.; Armour, M.; Morua, K.; Deweese, T.L.; Ivkov, R. Method to Reduce Non-Specific Tissue Heating of Small Animals in Solenoid Coils. Int. J. Hyperth. 2013, 29, 106–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sebeke, L.; Deenen, D.A.; Maljaars, E.; Heijman, E.; de Jager, B.; Heemels, W.P.M.H.; Grüll, H. Model Predictive Control for MR-HIFU-Mediated, Uniform Hyperthermia. Int. J. Hyperth. 2019, 36, 1039–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, H.W.; Horng, T.L. Bioheat Transfer and Thermal Heating for Tumor Treatment; Elsevier Inc., 2015; ISBN 9780124079007.

- Wu, L.; Cheng, J.; Liu, W.; Chen, X. Numerical Analysis of Electromagnetically Induced Heating and Bioheat Transfer for Magnetic Fluid Hyperthermia. IEEE Trans. Magn. 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, H.F.; Capistrano, G.; Mello, F.M.; Zufelato, N.; Silveira-Lacerda, E.; Bakuzis, A.F. Precise Determination of the Heat Delivery during in Vivo Magnetic Nanoparticle Hyperthermia with Infrared Thermography. Phys. Med. Biol. 2017, 62, 4062–4082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tay, Z.W.; Chandrasekharan, P.; Chiu-Lam, A.; Hensley, D.W.; Dhavalikar, R.; Zhou, X.Y.; Yu, E.Y.; Goodwill, P.W.; Zheng, B.; Rinaldi, C.; et al. Magnetic Particle Imaging-Guided Heating in Vivo Using Gradient Fields for Arbitrary Localization of Magnetic Hyperthermia Therapy. ACS Nano 2018, 12, 3699–3713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suriyanto; Ng, E. Y.K.; Kumar, S.D. Physical Mechanism and Modeling of Heat Generation and Transfer in Magnetic Fluid Hyperthermia through Néelian and Brownian Relaxation: A Review. Biomed. Eng. Online 2017, 16, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donahue, M.J.; Porter, D.G. OOMMF User’s Guide, Version 1.0. 1999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundara Mahalingam, S.; Manikandan, B. V.; Arockiaraj, S. Review - Micromagnetic Simulation Using OOMMF and Experimental Investigations on Nano Composite Magnets. In Proceedings of the Journal of Physics: Conference Series; Institute of Physics Publishing, April 2019; Vol. 1172; p. 012070. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrero, R.; Vicentini, M.; Manzin, A. Influence of Size, Volume Concentration and Aggregation State on Magnetic Nanoparticle Hyperthermia Properties versus Excitation Conditions. Nanoscale Adv. 2024, 6, 1739–1749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maier-Hauff, K.; Rothe, R.; Scholz, R.; Gneveckow, U.; Wust, P.; Thiesen, B.; Feussner, A.; Deimling, A.; Waldoefner, N.; Felix, R.; et al. Intracranial Thermotherapy Using Magnetic Nanoparticles Combined with External Beam Radiotherapy: Results of a Feasibility Study on Patients with Glioblastoma Multiforme. J. Neurooncol. 2007, 81, 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maier-Hauff, K.; Ulrich, F.; Nestler, D.; Niehoff, H.; Wust, P.; Thiesen, B.; Orawa, H.; Budach, V.; Jordan, A. Efficacy and Safety of Intratumoral Thermotherapy Using Magnetic Iron-Oxide Nanoparticles Combined with External Beam Radiotherapy on Patients with Recurrent Glioblastoma Multiforme. J. Neurooncol. 2011, 103, 317–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- COMSOL Multiphysics ® V E R S I O N 3. 5 A. 1998.

- Miaskowski, A.; Sawicki, B. Magnetic Fluid Hyperthermia Modeling Based on Phantom Measurements and Realistic Breast Model. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MCINTOSH, R.L.; ANDERSON, V. ERRATUM: “A COMPREHENSIVE TISSUE PROPERTIES DATABASE PROVIDED FOR THE THERMAL ASSESSMENT OF A HUMAN AT REST.”. Biophys. Rev. Lett. 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, J.; Erdmann, B.; Seebass, M. Impact of Nonlinear Heat Transfer on Temperature Control in Regional Hyperthermia. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 1999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.; Shima, M. Reduced Magnetization in Magnetic Oxide Nanoparticles. J. Appl. Phys. 2007, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalkidou, A.; Simeonidis, K.; Angelakeris, M.; Samaras, T.; Martinez-Boubeta, C.; Balcells, L.; Papazisis, K.; Dendrinou-Samara, C.; Kalogirou, O. In Vitro Application of Fe/MgO Nanoparticles as Magnetically Mediated Hyperthermia Agents for Cancer Treatment. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2011, 323, 775–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, A.; Scholz, R.; Maier-Hauff, K.; Johannsen, M.; Wust, P.; Nadobny, J.; Schirra, H.; Schmidt, H.; Deger, S.; Loening, S.; et al. Presentation of a New Magnetic Field Therapy System for the Treatment of Human Solid Tumors with Magnetic Fluid Hyperthermia. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2001, 225, 118–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubia-Rodríguez, I.; Santana-Otero, A.; Spassov, S.; Tombácz, E.; Johansson, C.; De La Presa, P.; Teran, F.J.; Morales, M.D.P.; Veintemillas-Verdaguer, S.; Thanh, N.T.K.; et al. Whither Magnetic Hyperthermia? A Tentative Roadmap. Materials (Basel). 2021, 14, 706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).