Submitted:

02 January 2025

Posted:

07 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

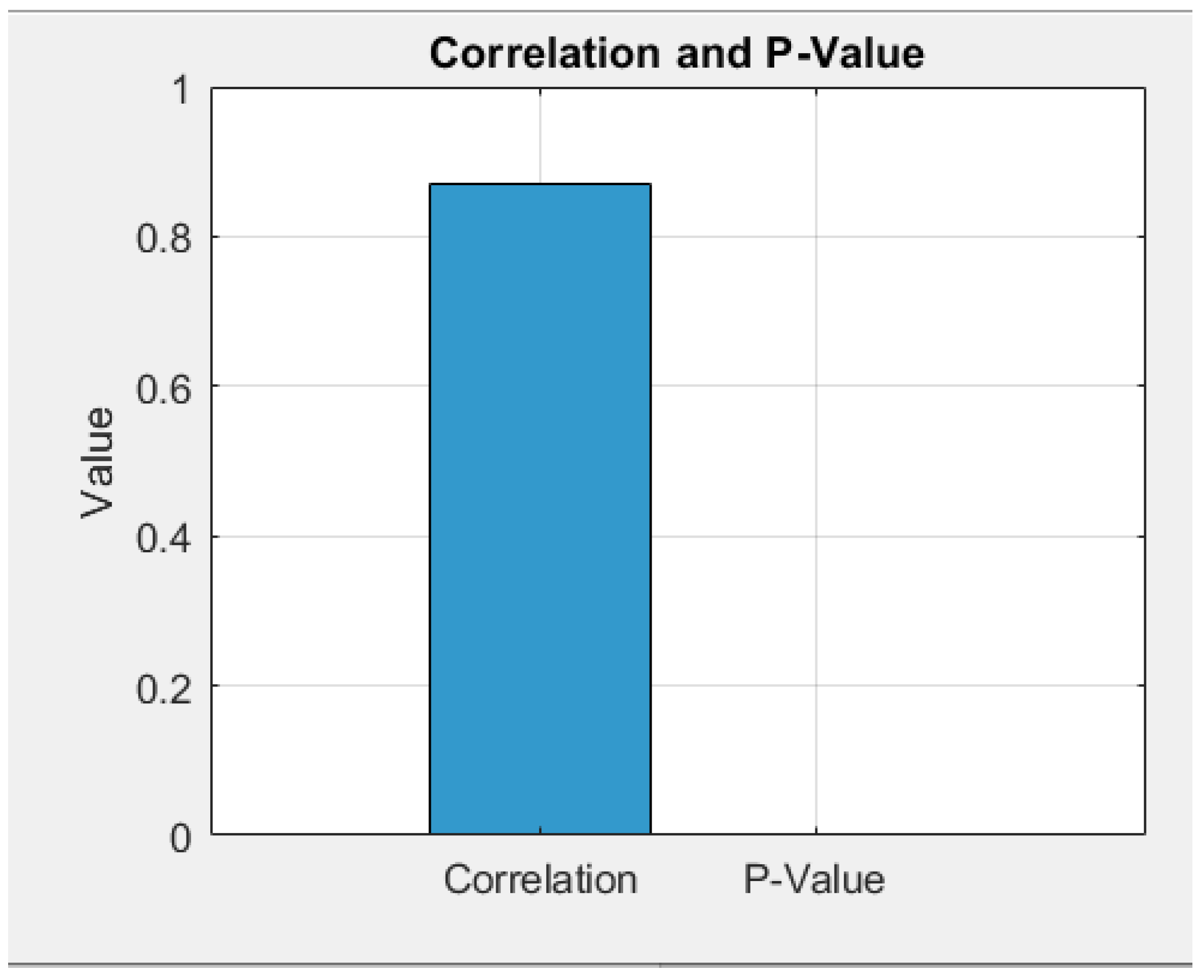

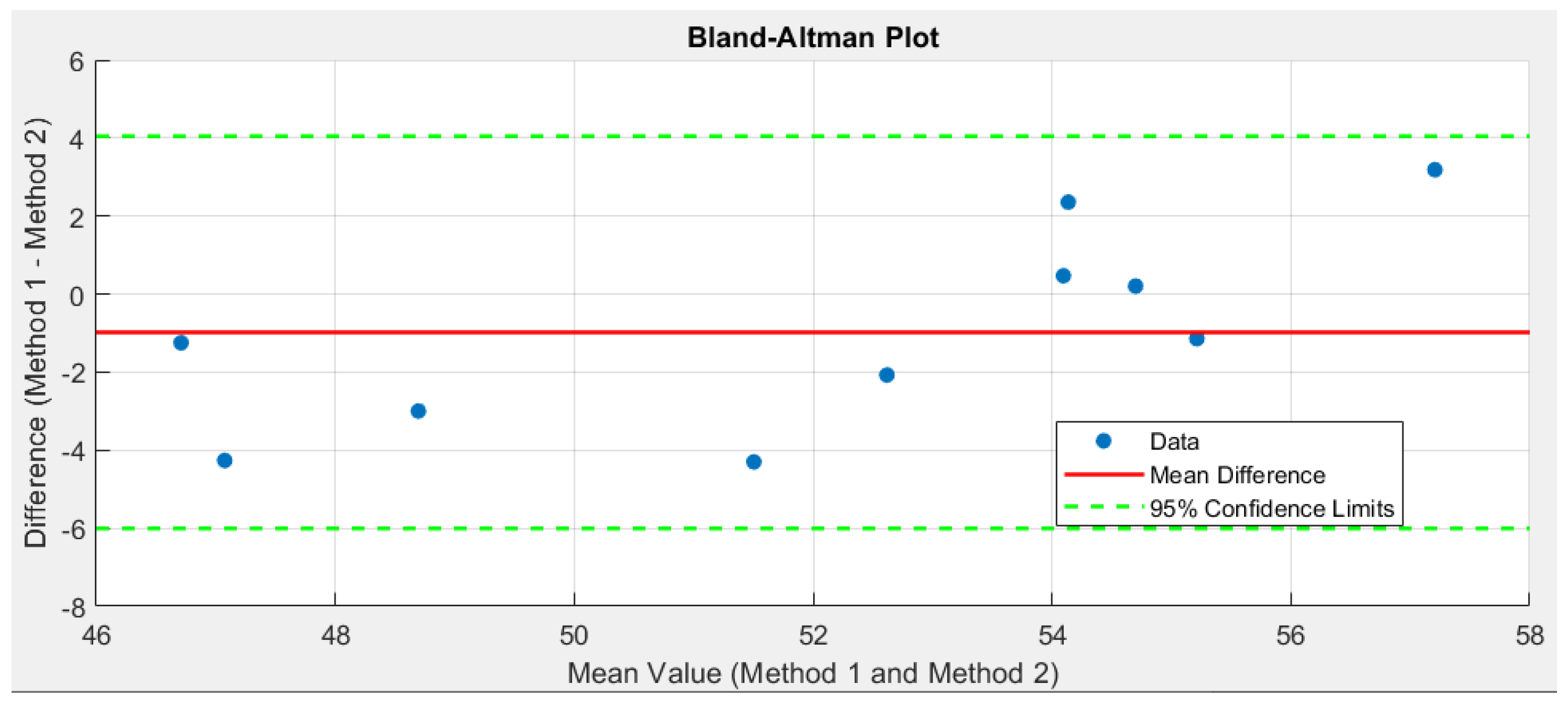

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

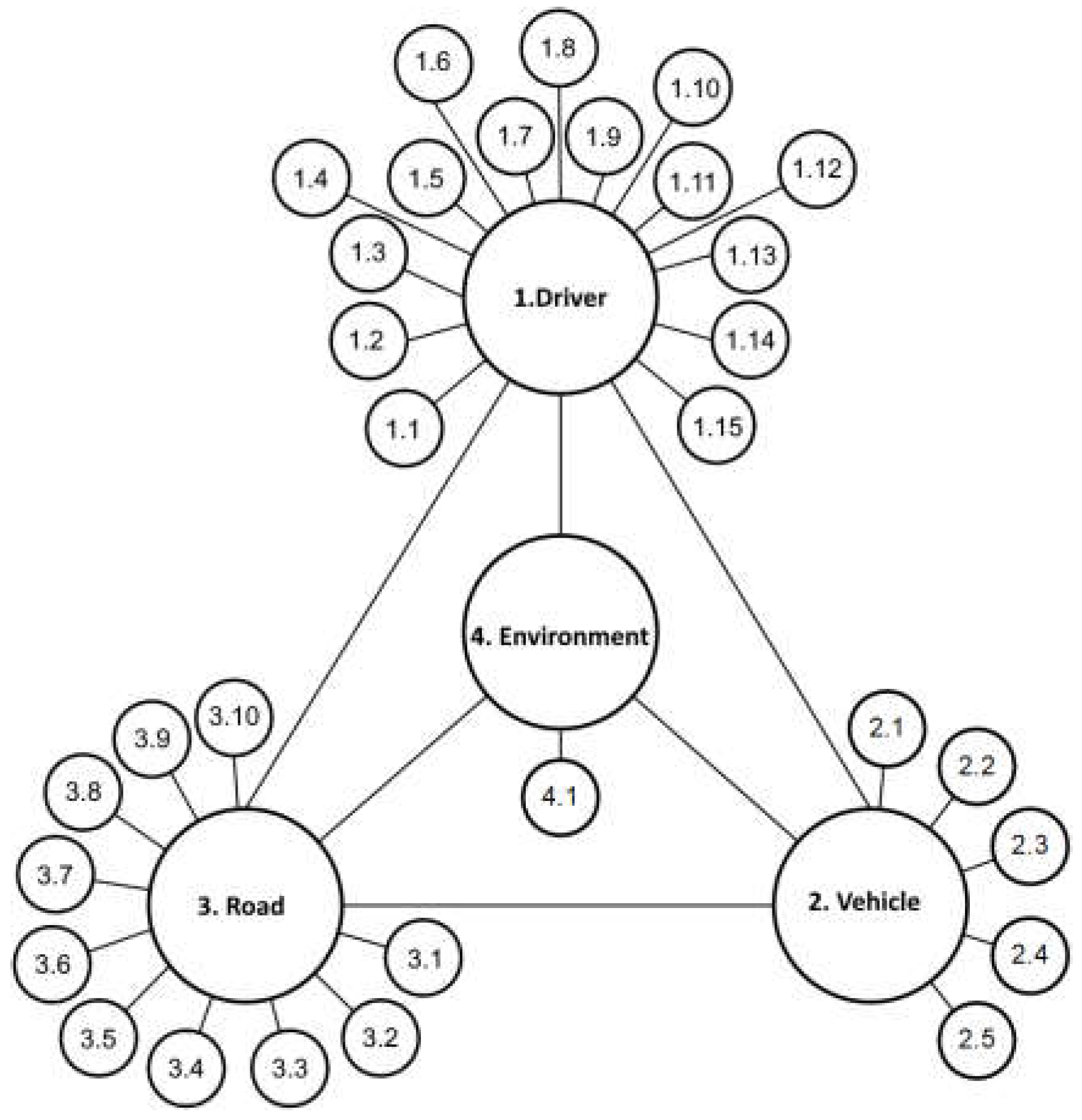

2.1. Data Classification and Structuring

2.2. Methodology for Predicting the Risk of Pedestrian-Involved Traffic Accidents Based on Factor Weighting by Relative Importance

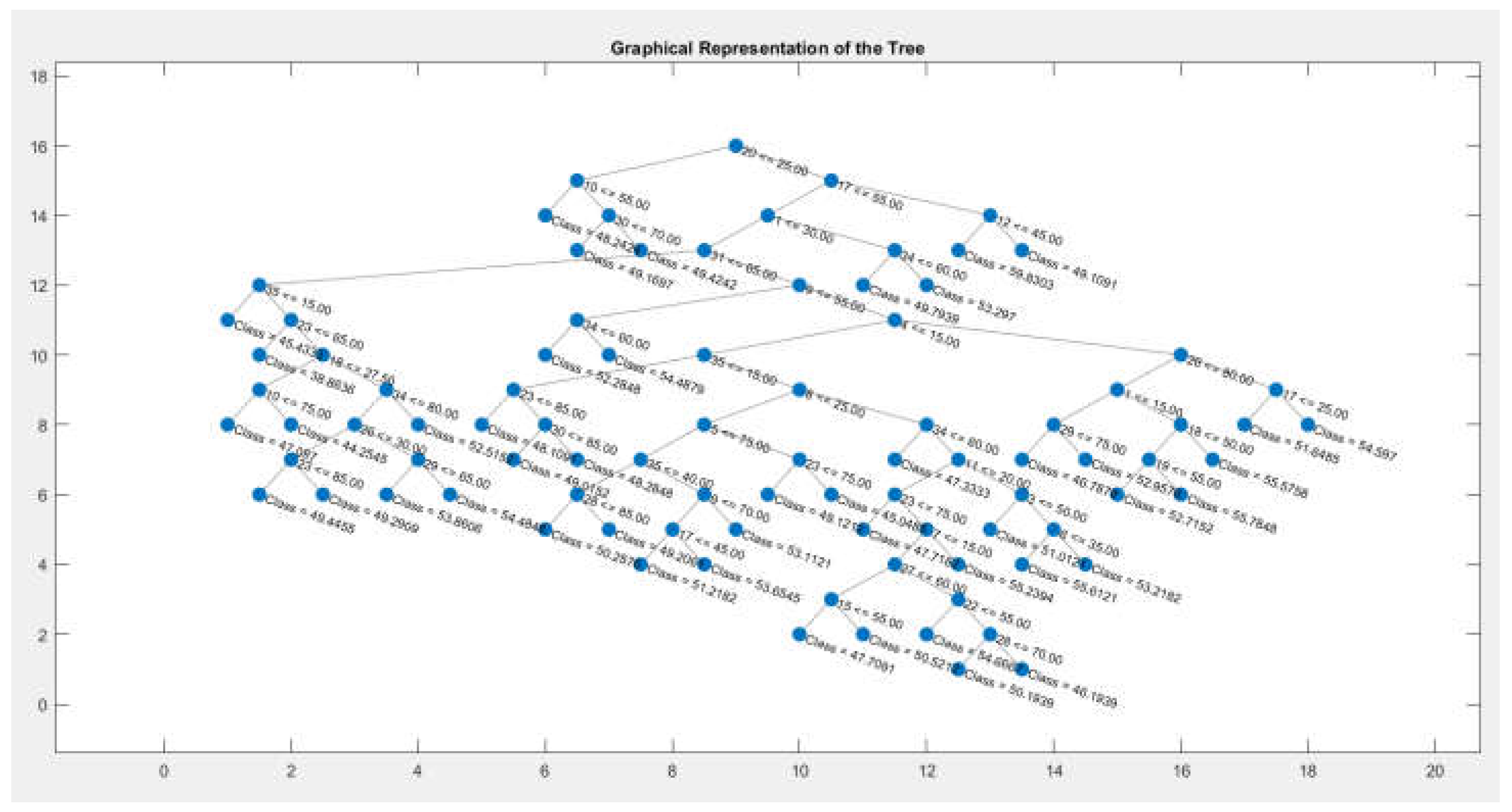

3. Experimental Results

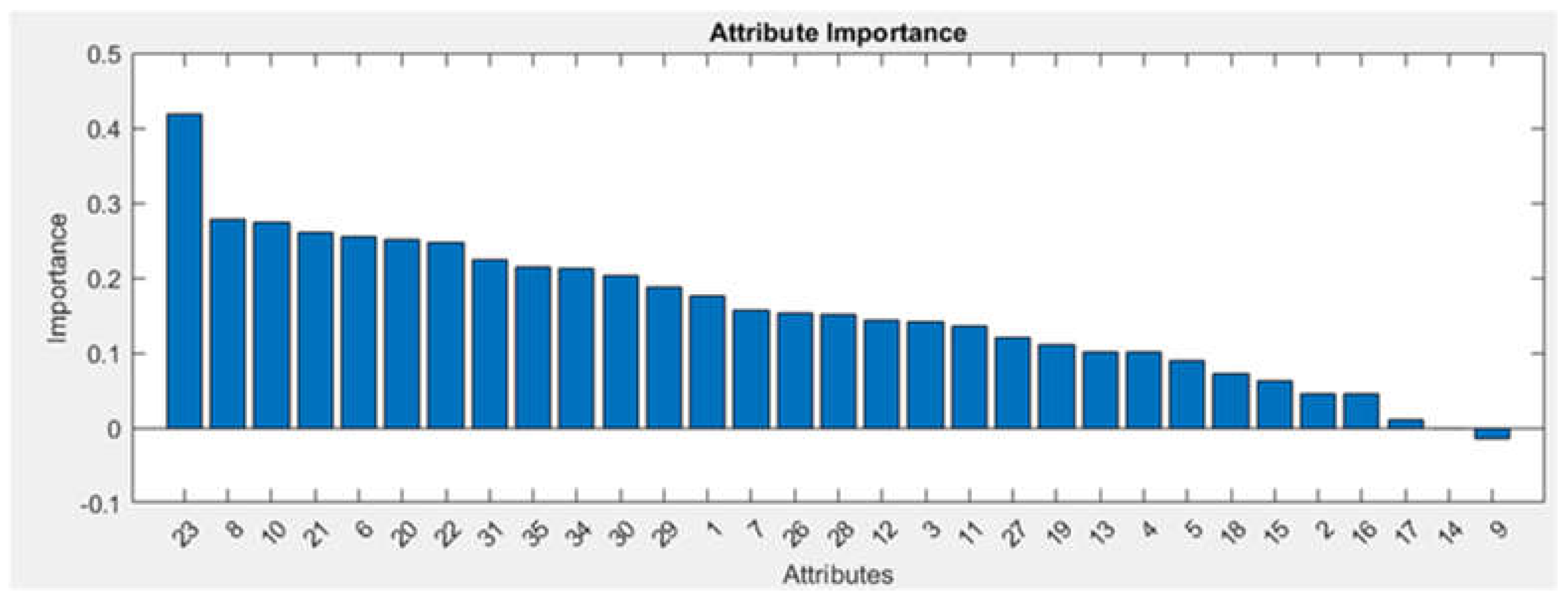

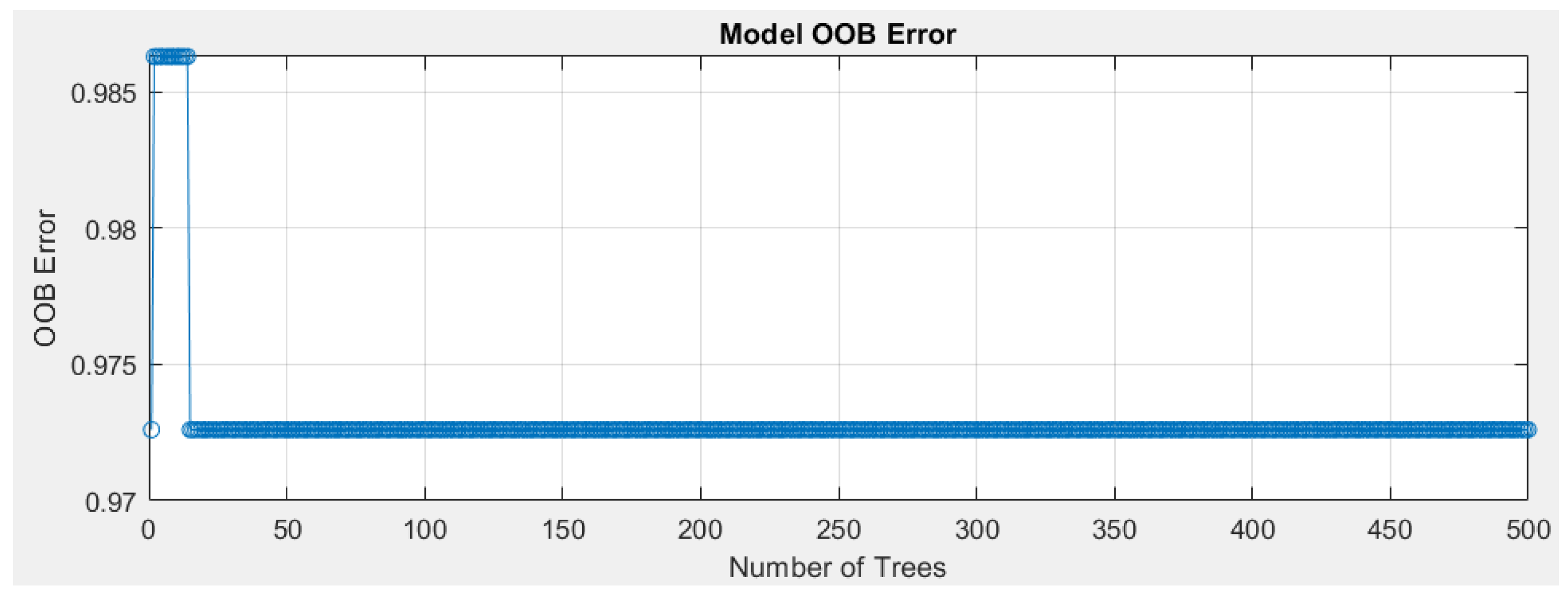

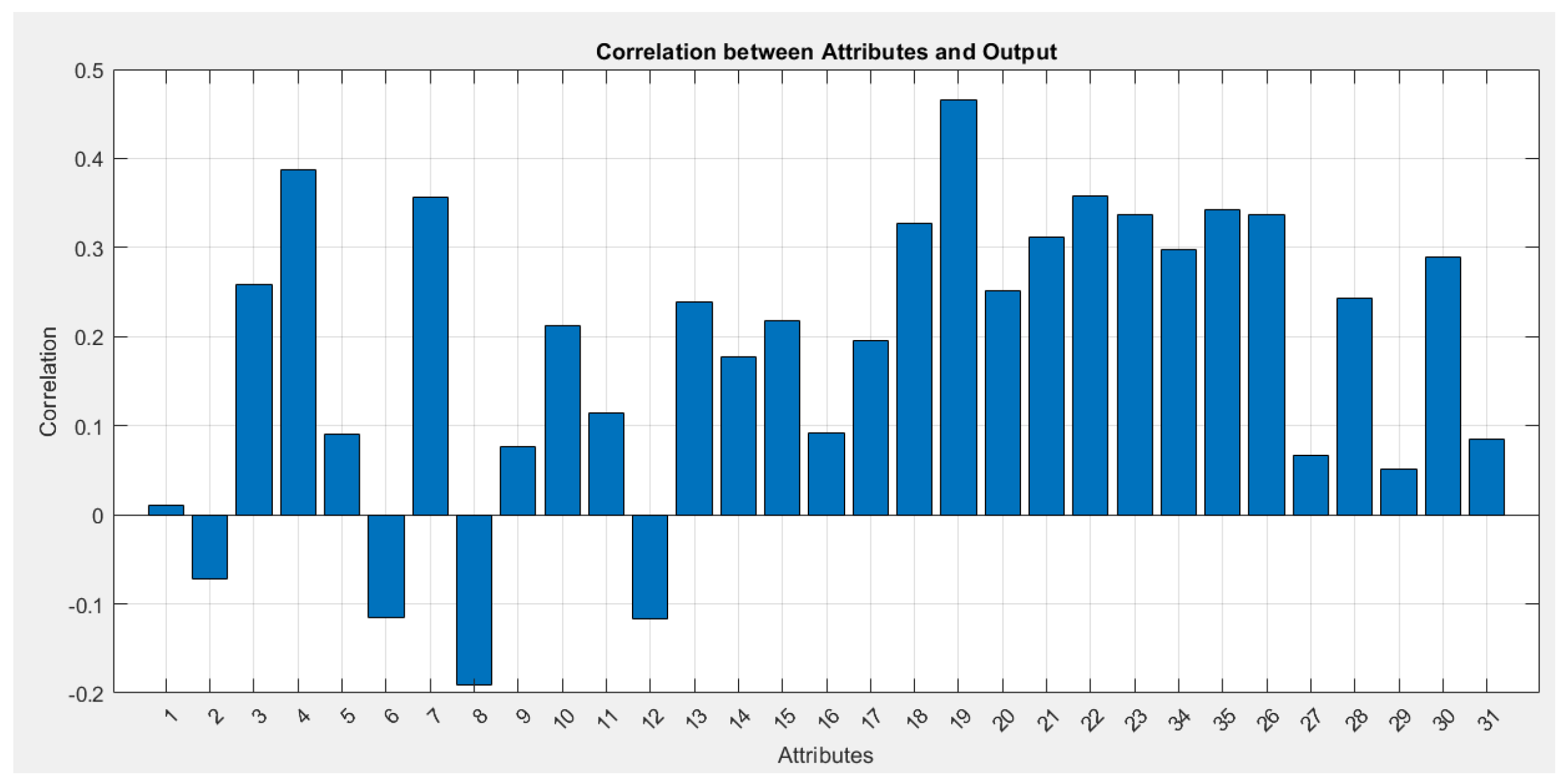

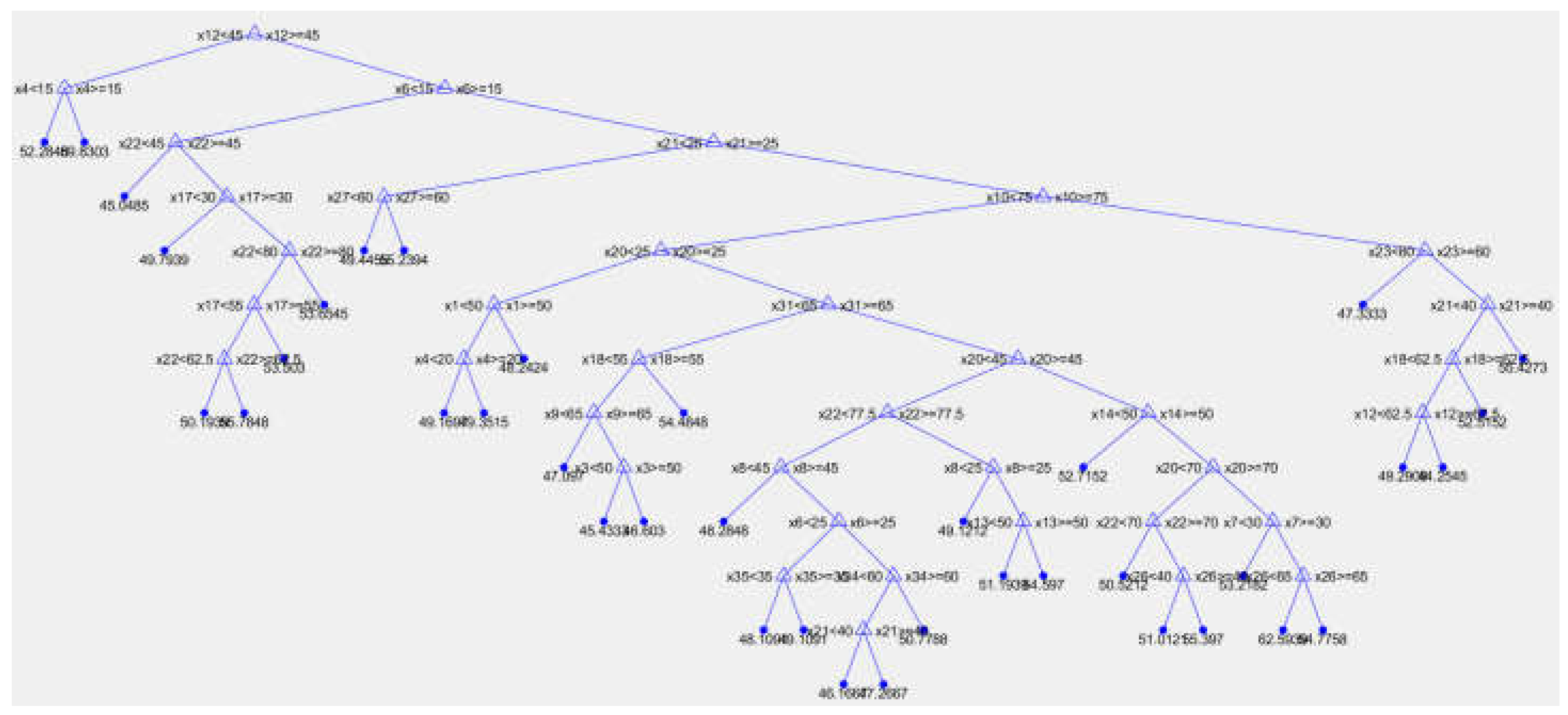

4. Methodology for Predicting the Risk of Pedestrian-Involved Traffic Accidents Using the Random Forest Method

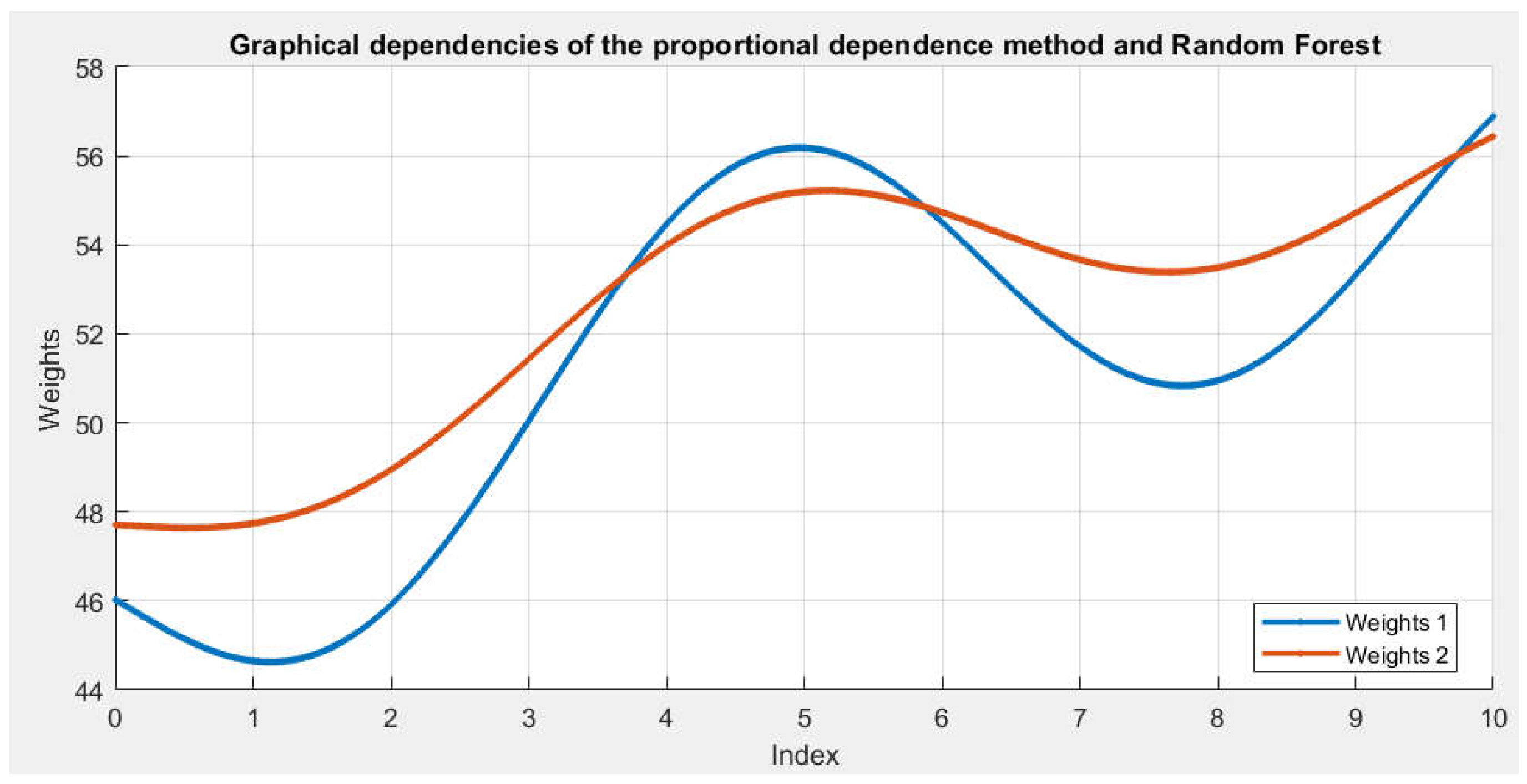

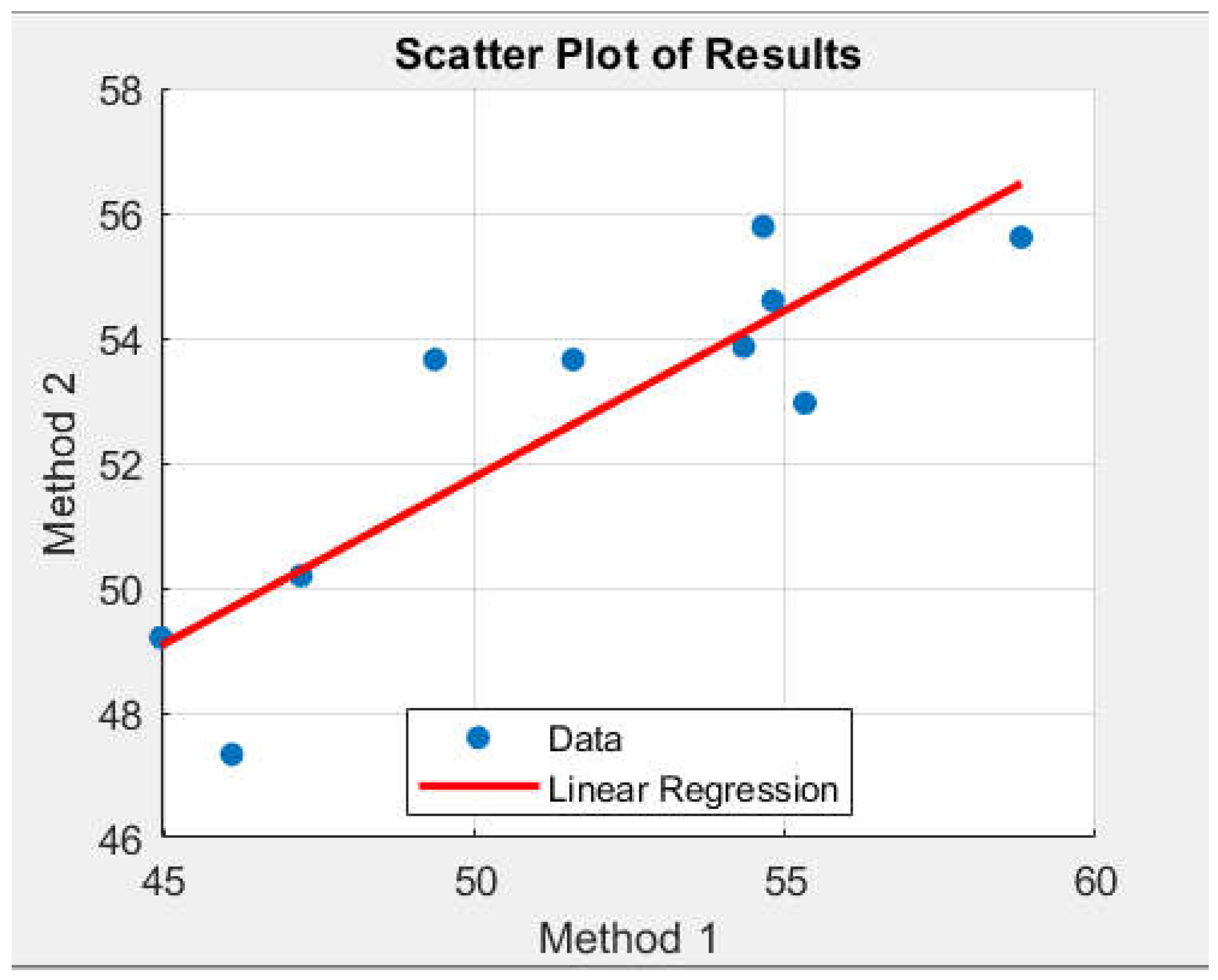

5. Comparative Analysis of the Proportional Dependence Methodology and Random Forest for Predicting Pedestrian Involved Traffic Accident Risk

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abdel-Aty, M.; Lee, J.; Yu, R. Analysis of pedestrian crashes using machine learning algorithms. Accident Analysis & Prevention 2019, 131, 285–293. [CrossRef]

- Stamov, G.; Stamova, I.; Simeonov, S.; Torlakov, I. On the Stability with Respect to H-Manifolds for Cohen–Grossberg-Type Bidirectional Associative Memory Neural Networks with Variable Impulsive Perturbations and Time-Varying Delays. Mathematics 2020, 8(3), 335. [CrossRef]

- Shahin Mirbakhsh, M.; Azizi, M. A Machine Learning Method for Improving the Safety of Pedestrians on Roadways. Journal of Industrial Safety Engineering 2024. https://journals.stmjournals.com/joise/article=2024/view=156953/.

- Theofilatos, A.; Yannis, G. A review of the effect of traffic and weather characteristics on road safety. Accident Analysis & Prevention 2014, 72, 244–256. [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; Abdel-Aty, M.; Shi, Q.; Yu, R. Assessing the impact of reduced visibility on traffic crash risk using microscopic data and surrogate safety measures. Transportation Research Part C: Emerging Technologies 2017, 74, 295–305. [CrossRef]

- Gospodinova, E.; Torlakov, I.; Metodieva, I. Model for Forecasting and Planning Solar Energy Production Using an Artificial Neural Network. In 2023 3rd International Conference on Electrical, Computer, Communications and Mechatronics Engineering (ICECCME); IEEE, 2023; pp. 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Mokhtarimousavi, S.; Anderson, J. C.; Azizinamini, A.; Hadi, M. Improved Support Vector Machine Models for Work Zone Crash Injury Severity Prediction and Analysis. Transportation Research Record 2019, 2673(11), 680–692. [CrossRef]

- Stamov, G.; Simeonov, S.; Torlakov, I.; Yaneva, M. Parallel Technique on Bidirectional Associative Memory Cohen-Grossberg Neural Network. In Recent Contributions to Bioinformatics and Biomedical Sciences and Engineering; Springer, 2023; pp. 16–20. [CrossRef]

- Gospodinova, E.; Torlakov, I. Information Processing with Stability Point Modeling in Cohen–Grossberg Neural Networks. Axioms 2023, 12(7), 612. [CrossRef]

- Breiman, L. Random forests. Machine Learning 2001, 45(1), 5–32. [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Zhang, Y.; Zhu, Z.; Wang, J. Real-time pedestrian detection and tracking for intelligent transportation systems using deep learning. Transportation Research Part C: Emerging Technologies 2020, 111, 62–78. [CrossRef]

- He, H.; Garcia, E. A. Learning from imbalanced data. IEEE Transactions on Knowledge and Data Engineering 2009, 21(9), 1263–1284. [CrossRef]

- Delen, S.; Sharda, R.; Bessonov, M. Identifying significant predictors of injury severity in traffic accidents using a series of artificial neural networks. Accident Analysis & Prevention 2006, 38(3), 434–444. [CrossRef]

- Alkheder, S.; Taamneh, M.; Taamneh, S. Severity prediction of traffic accident using an artificial neural network. Journal of Forecasting 2017, 36(1), 100–108. [CrossRef]

- Stamov, G.; Simeonov, S.; Torlakov, I. Visualization on Stability of Impulsive Cohen-Grossberg Neural Networks with Time-Varying Delays. In Contemporary Methods in Bioinformatics and Biomedicine and Their Applications; Springer, 2022; pp. 195–201. [CrossRef]

- Stamov, G.; Simeonov, S.; Torlakov, I. Software Analysis of Bidirectional Associative Memory (BAM) Cohen–Grossberg-Type Impulsive Neural Networks with Time-Varying Delays. In Proceedings of Seventh International Congress on Information and Communication Technology; Springer, 2022; pp. 371–378. [CrossRef]

- Gospodinova, E.; Torlakov, I.; Metodieva, I. Increasing the Productivity of an Electricity System Based on Energy Generated by Hydropower with the Help of Artificial Intelligence. In 2023 58th International Scientific Conference on Information, Communication and Energy Systems and Technologies (ICEST); IEEE, 2023; pp. 205–208. [CrossRef]

- Gospodinova, E.; Torlakov, I. Usage of High-Performance System in Impulsive Modelling of Hepatitis B Virus. In Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems; Springer, 2023; pp. 373–385. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Yau, K. K. W.; Chen, G. Risk factors associated with traffic violations and accident severity in China. Accident Analysis & Prevention 2016, 95, 503–511.

- Tang, J.; Liu, F.; Zou, Y.; Zhang, W.; Wang, Y. An improved fuzzy neural network for traffic speed prediction considering periodic characteristic. IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Transportation Systems 2017, 18(9), 2340–2350. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).