Submitted:

03 January 2025

Posted:

06 January 2025

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

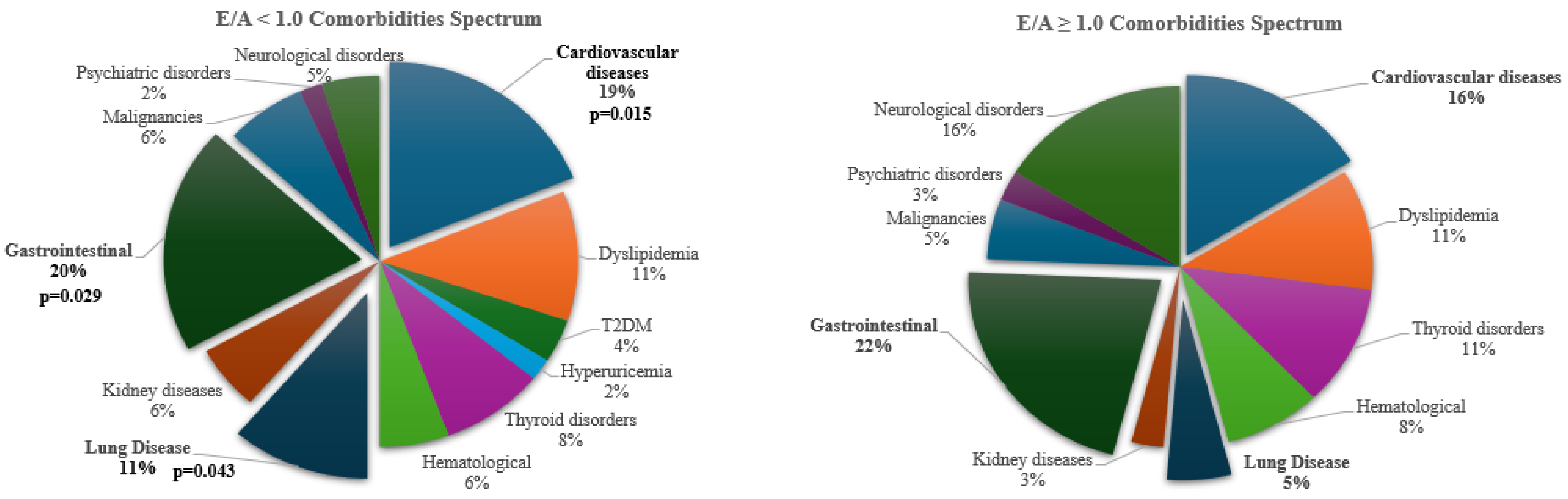

Background: The 2011 Very Early Diagnosis of Systemic Sclerosis (VEDOSS) criteria include patients at risk of progression and those with mild, non-progressive forms of SSc. Early diastolic and systolic dysfunction can indicate myocardial fibrosis in SSc patients, yet data on myocardial impairment in the VEDOSS population are limited. Objectives: This study aimed to identify subclinical echocardiographic changes and predictive markers of cardiac dysfunction in both very early and mild-longstanding forms of VEDOSS. Methods: We conducted a cross-sectional ob-servational study involving 81 patients meeting VEDOSS criteria followed up regular-ly within our Scleroderma referral center. Patients were categorized as early VEDOSS (e-VEDOSS) or mild-longstanding VEDOSS (ml-VEDOSS) based on disease duration (≥10 years). We analyzed clinical and demographic data, focusing on echocardio-graphic parameters such as the E/A ratio and left ventricular (LV) thickness. Statistical analyses included Chi-square, Fischer exact, and Student's T tests, with a significance threshold of p<0.05. Results: ml-VEDOSS patients were older and had longer diagnostic delays, with a higher burden of comorbidities. Autoantibody-positive patients exhibited lower E/A ratios and increased left atrial size. Notably, patients with reduced E/A ratios were older, had more comorbidities, and lower DLCO% values. Multivariable analysis confirmed DLCO% as the sole predictor of both diastolic and systolic impairment in both groups. Conclusion: Careful Monitoring of cardiac function in VEDOSS patients is crucial as subclinical alterations may occur even in the absence of symptoms. DLCO% emerged as an important predictor of diastolic dysfunction.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Definition

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Echocardiography Procedure

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Overall Patients’ Characteristics

3.2. Subclinical Echocardiographic Findings

3.3. Comparative Analysis Between Patients with Ad Without LV Diastolic Dysfunction (E/A Ratio Less than <1.0)

3.4. General Multivariable Regression Model

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ko, J.; Noviani, M.; Chellamuthu, V.R.; Albani, S.; Low, A.H.L. The Pathogenesis of Systemic Sclerosis: The Origin of Fibrosis and Interlink with Vasculopathy and Autoimmunity. Int J Mol Sci. 2023, 24, 14287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosa, I.; Romano, E.; Fioretto, B.S.; Manetti, M. The contribution of mesenchymal transitions to the pathogenesis of systemic sclerosis. Eur J Rheumatol. 2020, 7, S157–S164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herrick, A.L.; Assassi, S.; Denton, C.P. Skin involvement in early diffuse cutaneous systemic sclerosis: an unmet clinical need. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2022, 18, 276–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- LeRoy, E.C.; Medsger, T.A., Jr. Criteria for the classification of early systemic sclerosis. J Rheumatol. 2001, 28, 1573–6. [Google Scholar]

- van den Hoogen, F.; Khanna, D.; Fransen, J.; Johnson, S.R.; Baron, M.; Tyndall, A.; et al. 2013 classification criteria for systemic sclerosis: an American College of Rheumatology/European League against Rheumatism collaborative initiative. Arthritis Rheum. 2013, 65, 2737–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Goh, V.; Lee, J.; Espinoza, M.; Yuan, Y.; Carns, M.; et al. Clinical Phenotypes of Patients with Systemic Sclerosis With Distinct Molecular Signatures in Skin. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2023, 75, 1469–1480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellando-Randone, S.; Galdo, F.D.; Lepri, G.; et al. Progression of patients with Raynaud’s phenomenon to systemic sclerosis: a five-year analysis of the European Scleroderma Trial and Research group multicentre, longitudinal registry study for Very Early Diagnosis of Systemic Sclerosis (VEDOSS). The Lancet Rheumatology 2021, 3, e834–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avouac, J.; Fransen, J.; Walker, U.A.; et al. Preliminary criteria for the very early diagnosis of systemic sclerosis: results of a Delphi Consensus Study from EULAR Scleroderma Trials and Research Group. Ann Rheum Dis 2011, 70, 476–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lescoat, A.; Bellando-Randone, S.; Campochiaro, C.; Del Galdo, F.; Denton, C.P.; Farrington, S.; Galetti, I.; Khanna, D.; Kuwana, M.; Truchetet, M.E.; Allanore, Y.; Matucci-Cerinic, M. Beyond very early systemic sclerosis: deciphering pre scleroderma and its trajectories to open new avenues for preventive medicine. Lancet Rheumatol. 2023, 5, e683–e694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruni, C.; Frech, T.; Manetti, M.; et al. Vascular Leaking, a Pivotal and Early Pathogenetic Event in Systemic Sclerosis: Should the Door Be Closed? Front Immunol 2018, 9, 2045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D'Oria, M.; Gandin, I.; Riccardo, P.; Hughes, M.; Lepidi, S.; Salton, F.; et al. Correlation between Microvascular Damage and Internal Organ Involvement in Scleroderma: Focus on Lung Damage and Endothelial Dysfunction. Diagnostics (Basel). 2022, 13, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fioretto, B.S.; Rosa, I.; Matucci-Cerinic, M.; Romano, E.; Manetti, M. Current Trends in Vascular Biomarkers for Systemic Sclerosis: A Narrative Review. Int J Mol Sci. 2023, 24, 4097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, C.; Tang, S.; Zhu, D.; Ding, Y.; Qiao, J. Classical disease-specific autoantibodies in systemic sclerosis: clinical features, gene susceptibility, and disease stratification. Front Med. 2020, 7, 587773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bellando-Randone, S.; Galdo, F.D.; Lepri, G.; et al. Progression of patients with Raynaud’s phenomenon to systemic sclerosis: a five-year analysis of the European Scleroderma Trial and Research group multicentre, longitudinal registry study for Very Early Diagnosis of Systemic Sclerosis (VEDOSS). Lancet Rheumatol 2021, 3, e834–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blaja, E.; Jordan, S.; Mihai, C.M.; Dobrota, R.; Becker, M.O.; et al. The Challenge of Very Early Systemic Sclerosis: A Combination of Mild and Early Disease? J Rheumatol. 2021, 48, 82–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, R.L.; Caballero-Ruiz, B.; Clarke, E.L.; Kakkar, V.; Wasson, C.W.; Mulipa, P.; et al. Biological hallmarks of systemic sclerosis are present in the skin and serum of patients with Very Early Diagnosis of SSc (VEDOSS). Rheumatology (Oxford). 2024, keae698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Aoufy, K.; Melis, M.R.; Bandini, G.; et al. POS1593-HPR GASTROINTESTINAL INVOLVEMENT IS ALREADY REPORTED IN AN ITALIAN VEDOSS COHORT: RESULTS FROM A RHEUMATOLOGICAL NURSE ASSESSMENT. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases 2023, 82, 1172–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, S.; Lu, M. Detection of myocardial fibrosis: Where we stand. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2022, 9, 926378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cusmà Piccione, M.; Zito, C.; Bagnato, G.; Oreto, G.; Di Bella, G.; Bagnato, G.; Carerj, S. Role of 2D strain in the early identification of left ventricular dysfunction and in the risk stratification of systemic sclerosis patients. Cardiovasc Ultrasound. 2013, 11, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee SW, Choi EY, Jung SY, Choi ST, Lee SK, Park YB. E/E' ratio is more sensitive than E/A ratio for detection of left ventricular diastolic dysfunction in patients with systemic sclerosis. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2010, 28, S12–7.

- Pokeerbux, M.R.; Giovannelli, J.; Dauchet, L.; Mouthon, L.; Agard, C.; Lega, J.C.; Allanore, Y.; Jego, P.; Bienvenu, B.; Berthier, S.; et al. Survival and prognosis factors in systemic sclerosis: Data of a French multicenter cohort, systematic review, and meta-analysis of the literature. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2019, 21, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avouac J, Fransen J, Walker UA, Riccieri V, Smith V, Muller C, Miniati I, Tarner IH, Randone SB, Cutolo M, Allanore Y, Distler O, Valentini G, Czirjak L, Müller-Ladner U, Furst DE, Tyndall A, Matucci-Cerinic M; EUSTAR Group. Preliminary criteria for the very early diagnosis of systemic sclerosis: results of a Delphi Consensus Study from EULAR Scleroderma Trials and Research Group. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011, 70, 476–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruaro, B.; Smith, V.; Sulli, A.; Decuman, S.; Pizzorni, C.; Cutolo, M. Methods for the morphological and functional evaluation of microvascular damage in systemic sclerosis. Korean J Intern Med. 2015, 30, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lang, R.M.; Bierig, M.; Devereux, R.B.; Flachskampf, F.A.; Foster, E.; Pellikka, P.A. Recommendations for Chamber Quantification: A Report from the American Society of Echocardiography’s Guidelines and Standards Committee and the Chamber Quantification Writing Group, Developed in Conjunction with the European Association of Echocardiography, a Branch of the European Society of Cardiology. Journal of the American Society of Echocardiography 18, 1440–1463. [PubMed]

- Devereux, R.B.; Alonso, D.R.; Lutas, E.M.; Gottlieb, G.J.; Campo, E.; Sachs, I.; Reichek, N. Echocardiographic assessment of left ventricular hypertrophy: comparison to necropsy findings. Am J Cardiol 1986, 57, 450–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pyxaras, S.A.; Pinamonti, B.; Barbati, G.; Santangelo, S.; Valentincic, M.; Cettolo, F.; Secoli, G.; Magnani, S.; Merlo, M.; Lo Giudice, F.; Perkan, A.; Sinagra, G. Echocardiographic evaluation of systolic and mean pulmonary artery pressure in the follow-up of patients with pulmonary hypertension. Eur J Echocardiogr. 2011, 12, 696–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skinner, H.; Kamaruddin, H.; Mathew, T. Tricuspid Annular Plane Systolic Excursion: Comparing Transthoracic to Transesophageal Echocardiography. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2017, 31, 590–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagueh, S.F.; Appleton, C.P.; Gillebert, T.C.; Marino, P.N.; Oh, J.K.; Smiseth, O.A.; et al. Recommendations for the evaluation of left ventricular diastolic function by echocardiography. Eur J Echocardiogr 2009, 10, 165–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarz, E.R.; Dashti, R. The clinical quandary of left and right ventricular diastolic dysfunction and diastolic heart failure. Cardiovasc J Afr. 2010, 21, 212–20. [Google Scholar]

- Otto, C.M.; Nishimura, R.A.; Bonow, R.O.; Carabello, B.A.; Erwin JP 3rd Gentile, F.; et al. 2020 ACC/AHA Guideline for the Management of Patients with Valvular Heart Disease: Executive Summary: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation 2021, 143, e228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volkmann, E.R.; Fischer, A. Update on Morbidity and Mortality in Systemic Sclerosis-Related Interstitial Lung Disease. J Scleroderma Relat Disord. 2021, 6, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alfaddagh, A.; Martin, S.S.; Leucker, T.M.; Michos, E.D.; Blaha, M.J.; Lowenstein, C.J.; Jones, S.R.; Toth, P.P. Inflammation and cardiovascular disease: From mechanisms to therapeutics. Am J Prev Cardiol. 2020, 4, 100130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rangarajan, V.; Matiasz, R.; Freed, B.H. Cardiac complications of systemic sclerosis and management: Recent progress. Curr. Opin. Rheumatol. 2017, 29, 574–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giunta, A.; Tirri, E.; Maione, S.; et al. Right ventricular diastolic abnormalities in systemic sclerosis. Relation to left ventricular involvement and pulmonary hypertension. Ann Rheum Dis 2000, 59, 94–8. [Google Scholar]

- Bing, R.; Cavalcante, J.L.; Everett, R.J.; Clavel, M.A.; Newby, D.E.; Dweck, M.R. Imaging and Impact of Myocardial Fibrosis in Aortic Stenosis. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2019, 12, 283–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markusse, I.M.; Meijs, J.; de Boer, B.; Bakker, J.A.; Schippers, H.P.C.; Schouffoer, A.A.; Ajmone Marsan, N.; Kroft, L.J.M.; Ninaber, M.K.; Huizinga, T.W.J.; de Vries-Bouwstra, J.K. Predicting cardiopulmonary involvement in patients with systemic sclerosis: complementary value of nailfold videocapillaroscopy patterns and disease-specific autoantibodies. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2017, 56, 1081–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, C.Y.; Hsieh, S.C.; Wu, T.H.; Li, K.J.; Shen, C.Y.; Liao, H.T.; Wu, C.H.; Kuo, Y.M.; Lu, C.S.; Yu, C.L. Pathogenic Roles of Autoantibodies and Aberrant Epigenetic Regulation of Immune and Connective Tissue Cells in the Tissue Fibrosis of Patients with Systemic Sclerosis. Int J Mol Sci. 2020, 21, 3069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, C.; Jin, Z.; Homma, S.; Rundek, T.; Elkind, M.S.; Sacco, R.L.; Di Tullio, M.R. Effect of diabetes and hypertension on left ventricular diastolic function in a high-risk population without evidence of heart disease. Eur J Heart Fail. 2010, 12, 454–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- From, A.M.; Scott, C.G.; Chen, H.H. The development of heart failure in patients with diabetes mellitus and pre-clinical diastolic dysfunction a population-based study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010, 55, 300–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hinze, A.M.; Perin, J.; Woods, A.; Hummers, L.K.; Wigley, F.M.; Mukherjee, M.; Shah, A.A. Diastolic Dysfunction in Systemic Sclerosis: Risk Factors and Impact on Mortality. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2022, 74, 849–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcocer, L.A.; Bryce, A.; De Padua Brasil, D.; Lara, J.; Cortes, J.M.; Quesada, D.; Rodriguez, P. The Pivotal Role of Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme Inhibitors and Angiotensin II Receptor Blockers in Hypertension Management and Cardiovascular and Renal Protection: A Critical Appraisal and Comparison of International Guidelines. Am J Cardiovasc Drugs. 2023, 23, 663–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bütikofer, L.; Varisco, P.A.; Distler, O.; Kowal-Bielecka, O.; Allanore, Y.; Riemekasten, G.; Villiger, P.M.; Adler, S.; EUSTAR collaborators. ACE inhibitors in SSc patients display a risk factor for scleroderma renal crisis-a EUSTAR analysis. =Arthritis Res Ther. 2020, 22, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, H.; Tong, X.; Ning, Z.; Zhou, J.; Du, C.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Q.; Xu, D.; Zeng, X.; He, Z.X.; Zhao, X. Diffusing capacity of lungs for carbon monoxide associated with subclinical myocardial impairment in systemic sclerosis: A cardiac MR study. RMD Open. 2023, 9, e003391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| TOTAL n=81 |

e-VEDOSS n=51 |

ml-VEDOSS n=30 |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female, n(%) | 76 (93.8) | 49 (60.5) | 27 (33.3) | ns |

| Male, n(%) | 5 (6.2) | 2 (2.5) | 3 (3.7) | ns |

| Age at enrollment, mean±SD | 57.0±15.7 | 53.2±15.6 | 64.3±14.1 | 0.002 |

| Age at VEDOSS diagnosis, mean±SD | 48.2±17.9 | 48.6±15.9 | 47.5±14.5 | ns |

| Age at RP onset, mean±SD | 40.9±17.9 | 40.0±18.4 | 42.2±17.3 | ns |

| Disease Duration of VEDOSS, mean±SD | 9.4±7.7 | 4.7±2.8 | 16.8±7.0 | <0.001 |

| Disease duration of RP, mean±SD | 16.5±11.8 | 13.3±11.7 | 21.7±10.1 | 0.002 |

| Diagnostic delay, mean±SD | 7.4±10.3 | 8.7±11.2 | 5.1±8.1 | ns |

| Body Mass Index (Kg/m2), mean±SD | 23.4±5.9 | 22.1±5.9 | 25.2±5.9 | ns |

| Smoking habits, n(%) | 14 (17.3) | 11(13.5) | 3 (3.7) | ns |

| Alcohol Consumption, n(%) | 3 (3.7) | 2 (2.5) | 1 (1.2) | ns |

| Puffy hands, n(%) | 23 (28.4) | 12 (14.8) | 11 (13.5) | ns |

| ANA (positive) only, n(%) | 30 (37.0) | 22 (27.2) | 7 (8.6) | ns |

| Anticentromere (positive), n(%) | 23 (28.4) | 11 (13.5) | 13 (16.0) | ns |

| Anti-topoisomerase I (positive), n(%) | 5 (6.2) | 2 (2.5) | 3 (3.7) | ns |

| Gastrointestinal tract symptoms, n(%) | 36 (44.4) | 19 (23.5) | 17 (21.0) | ns |

| COMORBIDITIES, n(%) | ||||

| Cardiovascular diseases, | 37 (45.7) | 16 (19.8) | 21 (25.9) | 0.01 |

| Dyslipidemia | 21 (25.9) | 10 (12.3) | 11 (13.6) | ns |

| Hyperuricemia | 2 (2.5) | 0 (0) | 2 (2.5) | ns |

| Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus | 4 (4.9) | 2 (2.5) | 2 (2.5) | ns |

| Thyroid disorders | 18 (22.2) | 11 (13.5) | 7 (8.6) | ns |

| Lung Diseases | 14 (17.3) | 7 (8.6) | 7 (8.6) | ns |

| Kidney Diseases | 11 (22.2) | 5 (6.2) | 6 (7.4) | ns |

| Gastrointestinal diseases | 40 (49.4) | 21 (25.9) | 19 (23.5) | ns |

| Hematological disorders | 10 (12.3) | 4 (4.9) | 6 (7.4) | ns |

| Malignancies | 12 (14.8) | 6 (7.4) | 6 (7.4) | ns |

| Psychiatric disorders | 6 (7.4) | 4 (4.9) | 2 (2.5) | ns |

| Neurological disorders | 14 (17.3) | 7 (8.6) | 7 (8.6) | ns |

| Comorbidities count, mean±SD | 2.5±2.0 | 2.1±1.9 | 3.4±2.0 | 0.003 |

| Comorbidities count ≥ 3, n(%) | 40 (49.4) | 21 (25.9) | 19 (23.5) | ns |

| Comorbidities count ≥ 5, n(%) | 11 (22.2) | 4 (4.9) | 7 (8.6) | ns |

|

NVC PATTERN, n(%) Aspecific alterations Early pattern Active pattern Late pattern |

7 (8.6) 46 (57.8) 21 (25.) 7 (8.6) |

5 (4.9) 31 (38.3) 14 (17.3) 0 |

3 (3.7) 15 (18.5) 7 (8.6) 7 (7.4) |

ns 0.008 ns 0.006 |

| TREATMENT, n(%) | ||||

| Iloprost | 55 (67.) | 30 (37.0) | 25 (30.9) | 0.05 |

| Calcium Channel Blockers | 31 (38.3) | 14 (17.3) | 17 (21.0) | ns |

| Low-dose Aspirin | 56 (69.1) | 34 (42.0) | 22 (27.2) | ns |

| ACE-I/ARBs | 23 (28.4) | 8 (9.9) | 15 (18.5) | 0.002 |

| Beta-Blockers | 5 (6.2) | 2 (2.5) | 3 (3.7) | ns |

| Diuretics | 2 (2.5) | 1 (1.2) | 1 (1.2) | ns |

| Hydroxychloroquine | 23 (28.4) | 10 (12.3) | 13 (16.0) | 0.04 |

| Immunosuppressants | 3 (3.7) | 1 (1.2) | 2 (2.5) | ns |

| ECHOCARDIOGRAPHIC PARAMETERS | TOTAL n=61 |

|---|---|

| E deceleration time (m/s), mean±SD | 244.3±281.7 |

| E/E’ ratio, mean±SD | 6.9±1.9 |

| E wave, (m/s), mean±SD | 0.69±0.17 |

| A wave, (m/s), mean±SD | 0.75±0.19 |

| E/A ratio, mean±SD | 0.99±0.39 |

| E/A ratio < 1.0, n (%) | 37 (60.7) |

| LVED diameter, (mm), mean±SD | 40.3±4.8 |

| PWED thickness, (mm), mean±SD | 8.4±1.6 |

| PWED > 9 mm, n(%) | 19 (31.1) |

| IVS thckness, (mm), mean±SD | 9.3±1.8 |

| IVS > 10 mm, n (%) | 17 (27.9) |

| LVED volume 4CH Simpson, (ml), mean±SD | 67.7±16.6 |

| LVES volume 4CH Simpson, (ml), mean±SD | 25.5±11.8 |

| LVED volume 4CH AL, (ml/m2), mean±SD | 43.4±8.8 |

| LVES volume 4CH AL, (ml/m2), mean±SD | 14.7±4.3 |

| EF%, mean±SD | 64.5±4.8 |

| EF%<55% | 3 (4.9) |

| Mass ASE, (g), mean±SD | 123.2±123.9 |

| Mass/BSA, (g/m2), mean±SD | 66.3±17.3 |

| Relative wall thickness, mean±SD | 0.44±0.10 |

| Mass/height, (g/m), mean±SD | 65.8±18.2 |

| Aortic diameter, (mm2), mean±SD | 29.7±3.9 |

| LAES area, (cm2), mean±SD | 15.6±3.6 |

| LAES 4CH Simpson, (ml), mean±SD | 40.4±13.7 |

| LAES 4CH ind, (ml/m2), mean±SD | 24.4±7.5 |

| LAES diameter sup-inf 4CH, (mm/m2), mean±SD | 46.5±7.6 |

| RAES diameter AL, (mm), mean±SD | 46.1±5.8 |

| RAES 4CH Simpson, (ml), mean±SD | 30.3±8.9 |

| RAES 4CH ind, (ml/m2), mean±SD | 18.5±5.0 |

| RAES area, (cm2), mean±SD | 13.5±3.1 |

| TAPSE, (mmHg), mean±SD | 21.5±3.0 |

| TAPSE < 22 mmHg, n (%) | 36 (59.0) |

| TAPSE < 16 mmHg, n (%) | 1 (1.6) |

| TAPSE/sPAP, mean±SD | 0.72±0.32 |

| TAPSE/sPAP < 0.55, n (%) | 1 (1.6) |

| sPAP, (mmHg), mean±SD | 27.2±5.3 |

| Tricuspid maximum regurgitation gradient, (mmHg), mean±SD | 22.2±6.5 |

| Mitral Valve Insufficiency, n (%) | 42 (68.9) |

| Mitral Valve Sclerosis, n (%) | 25 (40.9) |

| Tricuspid Valve Insufficiency, n (%) | 33 (54.1) |

| Aortic Valve Insufficiency, n (%) | 13 (21.3) |

| Aortic Valve Sclerosis, n (%) | 11 (18.0) |

| Pericardial Effusion, n (%) | 4 (6.6) |

| Late pattern N=6 |

No late pattern N=55 |

p-value |

ACA/ATA+ N=24 |

ACA/ATA- N=37 |

p-value |

Puffy Hands N=18 |

No Puffy hands N=43 |

p-value |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E deceleration time (m/s), mean±SD | 225-2±46-1 | 246.7±298.9 | 0.86 | 213.4±56.2 | 261.6±349.9 | 0.55 | 230.5±52.8 | 194.4±47.9 | 0.02 |

| E/E’ ratio, mean±SD | 7.55±1.37 | 6.92±1.90 | 0.52 | 7.6±1.8 | 6.7±1.8 | 0.12 | 7.0±1.3 | 6.8±1.9 | 0.77 |

| E wave, (m/s), mean±SD | 0.70±0.22 | 0.68±0.16 | 0.86 | 0.71±0.17 | 0.65±0.17 | 0.27 | 0.68±0.19 | 0.69±0.16 | 0.78 |

| A wave, (m/s), mean±SD | 0.81±0.17 | 0.75±0.19 | 0.46 | 0.84±0.20 | 0.70±0.15 | 0.006 | 0.79±0.20 | 0.74±0.18 | 0.38 |

| E/A ratio, mean±SD | 0.92±0.40 | 1.0±0.39 | 0.61 | 0.84±0.27 | 1.08±042 | 0.02 | 0.92±0.4 | 1.02±0.39 | 0.39 |

| E/A ratio < 1.0, n (%) | 3 (50) | 34 (61.8) | 0.12 | 18 (75) | 19 (51.4) | 0.11 | 10 (55.6) | 27 (62.8) | 0.77 |

| LVED diameter, (mm), mean±SD | 38.5±3.6 | 40.5±4.9 | 0.34 | 39.4±5.6 | 40.8±4.4 | 0.45 | 40.2±6.2 | 40.4±4.07 | 0.86 |

| PWED thickness, (mm), mean±SD | 8.4±1.5 | 8.3±1.6 | 0.89 | 8.6±1.2 | 8.2±1.8 | 0.31 | 8.5±1.5 | 8.3±1.7 | 0.63 |

| PWED > 9 mm, n(%) | 4 (66.7) | 13 (23.6) | 0.04 | 9 (37.5) | 8 (21.6) | 0.24 | 8 (44.4) | 9 (20.9) | 0.11 |

| IVS thckness, (mm), mean±SD | 9.9±1.6 | 9.3±1.8 | 0.37 | 9.9±1.3 | 8.9±1.9 | 0.03 | 9.4±1.6 | 9.4±2.0 | 0.90 |

| IVS > 10 mm, n (%) | 2 (33.3) | 20 (36.4) | 0.39 | 10 (41.7) | 12 (32.4) | 0.58 | 6 (33.3) | 16 (37.2) | 1.0 |

| LVED volume 4CH Simpson, (ml), mean±SD | 69.7±22.2 | 67.5±16.1 | 0.76 | 66.9±17.3 | 68.3±16.4 | 0.75 | 24.8±3.5 | 85.3±363.2 | 0.49 |

| LVES volume 4CH Simpson, (ml), mean±SD | 24.8±9.7 | 25.6±12.1 | 0.88 | 24.0±9.9 | 26.4±12.8 | 0.46 | 68.3±17.8 | 68.7±16.3 | 0.93 |

| LVED volume 4CH AL, (ml/m2), mean±SD | 41.3±12.4 | 43.6±8.4 | 0.88 | 41.7±10.3 | 44.3±7.8 | 0.29 | 25.7±10.9 | 26.0±12.7 | 0.92 |

| LVES volume 4CH AL, (ml/m2), mean±SD | 14.8±5.6 | 14.7±4.2 | 0.54 | 14.7±6.2 | 14.7±2.9 | 0.92 | 43.1±10.5 | 44.3±8.2 | 0.64 |

| EF%, mean±SD | 64.5±6.8 | 64.6±4.6 | 0.92 | 64.9±5.7 | 64.4±4.3 | 0.64 | 15.6±6.2 | 14.6±3.2 | 0.42 |

| EF%<55% | 1 (16.7) | 2 (3.6) | 0.27 | 2 (8.3) | 1 (2.7) | 0.55 | 2 (11.1) | 1 (2.3) | 0.21 |

| Mass ASE, (g), mean±SD | 108.3±30.9 | 124.9±130.8 | 0.96 | 129.1±153.4 | 112±30.3 | 0.63 | 63.5±5.7 | 65.1±4.5 | 0.26 |

| Mass/BSA, (g/m2), mean±SD | 65.5±17.0 | 66.4±17.0 | 0.90 | 68.8±17.4 | 64.9±17.4 | 0.42 | 163.3±217.5 | 107.3±36.9 | 0.14 |

| Relative wall thickness, mean±SD | 0.48±0.08 | 0.44±0.1 | 0.35 | 0.48±0.09 | 0.42±0.10 | 0.04 | 68.3±19.5 | 66.5±17.0 | 0.73 |

| Mass/height, (g/m), mean±SD | 69.2±21.8 | 65.5±17.9 | 0.64 | 68.1±20.3 | 64.7±17.2 | 0.51 | 0.45±0.12 | 0.44±0.09 | 0.65 |

| Aortic diameter, (mm2), mean±SD | 29.7±2.4 | 29.6±4.1 | 0.96 | 29.7±3.7 | 29.6±4.1 | 0.94 | 65.3+20.6 | 67.5±17.8 | 0.68 |

| LAES area, (cm2), mean±SD | 16.1±2.7 | 15.6±3.7 | 0.75 | 16.7±4.1 | 15.1±3.2 | 0.11 | 28.5±2.5 | 30.0±4.3 | 0.19 |

| LAES 4CH Simpson, (ml), mean±SD | 41.6±10.5 | 40.3±14.3 | 0.83 | 46.7±18.7 | 37.2±8.9 | 0.01 | 15.4±3.3 | 16.1±3.8 | 0.52 |

| LAES 4CH ind, (ml/m2), mean±SD | 24.6±5.7 | 24.4±7.8 | 0.95 | 27.7±10.2 | 22.6±5.1 | 0.01 | 42.3±13.2 | 40.8±14.2 | 0.73 |

| LAES diameter 4CH, (mm/m2), mean±SD | 50.3±5.8 | 46.1±8.1 | 0.27 | 49.7±5.9 | 45.0±8.4 | 0.04 | 25.6±8.3 | 24.6±7.3 | 0.68 |

| RAES diameter AL, (mm), mean±SD | 47.2±1.7 | 46.0±6.1 | 0.74 | 47.8±45.4 | 45.4±5.8 | 0.22 | 46.9±6.0 | 46.7±9.1 | 0.91 |

| RAES 4CH Simpson, (ml), mean±SD | 32.9±9.6 | 30.0±8.9 | 0.55 | 30.1±8.1 | 30.5±9.5 | 0.91 | 44.8±4.5 | 47.0±6.2 | 0.27 |

| RAES 4CH ind, (ml/m2), mean±SD | 19.1±5.4 | 18.4±5.1 | 0.78 | 18.5±3.6 | 18.5±5.6 | 0.98 | 28.4±7.9 | 31.7±9.5 | 0.33 |

| RAES area, (cm2), mean±SD | 13.8±2.5 | 13.5±3.2 | 0.83 | 14.4±2.9 | 13.0±3.2 | 0.12 | 17.9±4.8 | 18.9±5.4 | 0.59 |

| TAPSE, (mmHg), mean±SD | 22.0±4.9 | 21.5±2.9 | 0.70 | 21.9±3.7 | 21.4±2.7 | 0.61 | 13.1±2.2 | 13.8±3.6 | 0.43 |

| TAPSE < 22 mmHg, n (%) | 4 (66.7) | 32 (58.2) | 1.0 | 14 (58.3) | 22 (59.4) | 1.0 | 12 (66.7) | 23 (53.5) | 0.40 |

| TAPSE < 16 mmHg, n (%) | 0 (0) | 1 (1.8) | 1.0 | 1 (4.2) | 0 (0) | 0.39 | 0 (0) | 1 (2.3) | 1.0 |

| TAPSE/sPAP, mean±SD | 0.98±0.31 | 0.69±0.32 | 0.24 | 0.71±0.38 | 0.72±0.29 | 0.92 | 21.8±3.3 | 21.3±2.8 | 0.59 |

| TAPSE/sPAP < 0.55, n (%) | 1 (16.7) | 3 (5.5) | 0.35 | 1 (4.2) | 3 (8.1) | 1.0 | 1 (5.6) | 3 (7.0) | 1.0 |

| sPAP, (mmHg), mean±SD | 28.0±4.2 | 27.1±5.5 | 0.83 | 26.7±4.4 | 27.7±6.2 | 0.63 | 0.7+±.36 | 0.69±0.33 | 0.29 |

| Tricuspid maximum regurgitation gradient, (mmHg), mean±SD | 21.9±3.4 | 22.2±6.7 | 0.93 | 22.4±4.8 | 22.1±7.4 | 0.88 | 27.7±3.9 | 26.8±6.3 | 0.75 |

| Mitral Valve Insufficiency, n (%) | 5 (83.3) | 37 (67.3) | 0.66 | 21 (87.5) | 21 (56.8) | 0.01 | 12 (66.7) | 30 (69.8) | 1.0 |

| Mitral Valve Sclerosis, n (%) | 3 (50) | 22 (40) | 0.68 | 17 (70.8) | 8 (21.6) | <0.001 | 9 (50) | 16 (37.2) | 0.40 |

| Tricuspid Valve Insufficiency, n (%) | 3 (50) | 30 (54.5) | 1.0 | 15 (62.5) | 18 (48.6) | 0.31 | 10 (55.6) | 23 (53.5) | 1.0 |

| Aortic Valve Insufficiency, n (%) | 4 (66.7) | 10 (18.2) | 0.02 | 10 (41.7) | 4 (10.8) | 0.01 | 5 (27.8) | 9 (20.9) | 0.74 |

| Aortic Valve Sclerosis, n (%) | 4 (66.7) | 9 (16.4) | 0.01 | 9 (37.5) | 4 (10.8) | 0.02 | 5 (27.8) | 8 (18.6) | 0.49 |

| Pericardial Effusion, n (%) | 0 (0) | 4 (7.3) | 1.0 | 1 (4.2) | 3 (8.1) | 1.0 | 2 (11.1) | 2 (4.7) | 0.57 |

| E/A <1.0 N=37 |

E/A>1.0 N=24 |

P-VALUE | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Female, n (%) | 35 (94.6) | 23 (95.8) | 1.0 |

| Male, n (%) | 2 (5.4) | 1 (4.2) | 1.0 |

| Age at enrollment, mean±SD | 66.3±9.6 | 46.5±13.8 | <0.001 |

| Age At VEDOSS Diagnosis, mean±SD | 56.8±10.0 | 37.0±14.2 | <0.001 |

| Age At RP Onset, mean±SD | 48.5±15.9 | 31.8±14.8 | <0.001 |

| Disease Duration of VEDOSS, mean±SD | 10.5±7.5 | 9.7±8.7 | 0.70 |

| Disease Duration of RP, mean±SD | 17.5±12.4 | 15.4±10.8 | 0.52 |

| Diagnostic Delay, mean±SD | 7.3±11.3 | 5.9±7.3 | 0.64 |

| Body Mass Index, (Kg/m2), mean±SD | 24.6±5.7 | 22.1±6.4 | 0.15 |

| Raynaud’s Phenomenon > 10 Years, n (%) | 26 (70.3) | 14 (58.3) | 0.41 |

| VEDOSS > 10 Years, n (%) | 18 (48.6) | 8 (33.3) | 0.29 |

| Smoking habits, n (%) | 2 (5.4) | 7 (29.2) | 0.02 |

| Alcohol consumption, n (%) | 2 (5.4) | 1 (4.2) | 1.0 |

| Raynaud’s Phenomenon, n (%) | 34 (91.9) | 22 (91.7) | 1.0 |

| Puffy Hands, n (%) | 11 (29.7) | 8 (33.3) | 0.78 |

| ANA (positive) only, n (%) | 14 (37.8) | 7 (29.2) | 0.58 |

| ANA (negative), n (%) | 6 (16.2) | 10 (41.7) | 0.03 |

| SSc Specific Antibodies (positive), n (%) | 17 (45.9) | 7 (29.2) | 0.28 |

| Comorbidity Count, mean±SD | 3.5±2.2 | 1.9±1.6 | 0.007 |

| Comorbidity Count>3, n (%) | 26 (70.3) | 9 (37.5) | 0.01 |

| Comorbidity Count>5, n (%) | 10 (27) | 1 (4.2) | 0.005 |

| PFTs Measurement, n (%) | |||

| FVC/DLCO > 1.5 | 18 (48.6) | 5 (20.8) | 0.03 |

| DLCO < 80% | 18 (48.6) | 5 (20.8) | 0.03 |

| FVC < 80% | 1 (2.7) | 1 (4.2) | 1.0 |

| NFC PATTERN, n (%) | |||

| Aspecific NFC alterations | 6 (16.2) | 1 (4.2) | 0.23 |

| Early | 21 (56.8) | 15 (62.5) | 0.79 |

| Active | 7 (18.9) | 5 (20.8) | 1.0 |

| Late | 3 (8.1) | 3 (12.5) | 1.0 |

| TREATMENTS, n (%) | |||

| Iloprost | 28 (75.7) | 16 (66.7) | 0.56 |

| Calcium Channel Blockers | 14 (37.8) | 8 (33.3) | 0.78 |

| Low dose Aspirin | 22 (59.5) | 16 (66.7) | 0.60 |

| ACE-I/ARBs | 14 (37.8) | 3 (12.5) | 0.04 |

| Beta-Blockers | 4 (10.8) | 0 (0) | 0.28 |

| Diuretics | 1 (2.7) | 1 (4.2) | 1.0 |

| Hydroxychloroquine | 14 (37.8) | 5 (20.8) | 0.25 |

| Immunosuppressants | 1 (2.7) | 2 (8.3) | 0.55 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).