Submitted:

03 January 2025

Posted:

04 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Material

2.2. Experimental Design and Field Establishment

2.3. Sample Preparation and Measurement

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

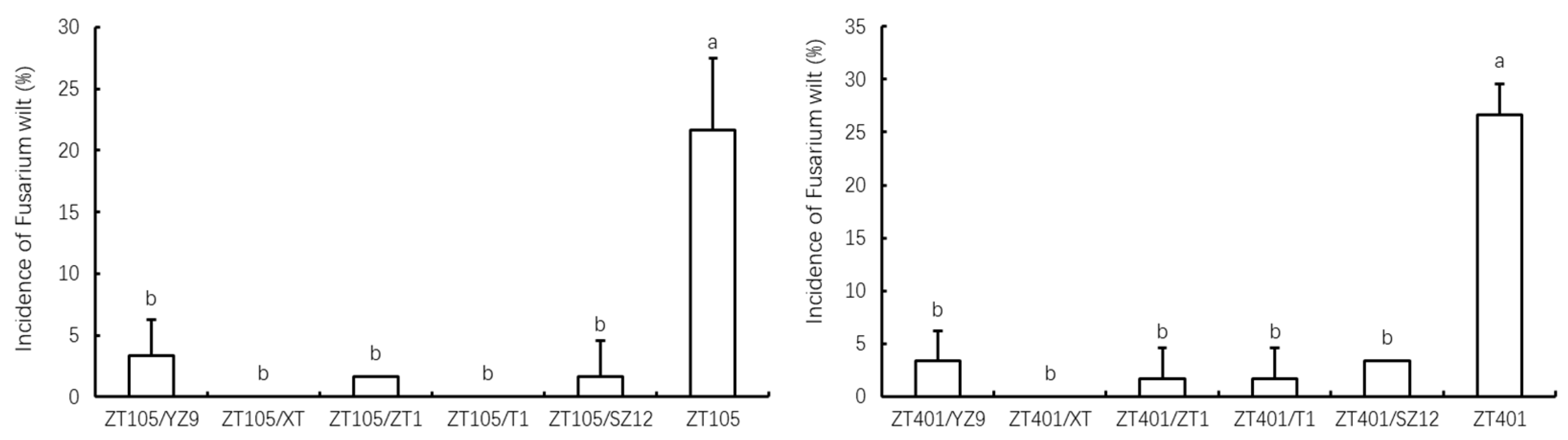

3.1. Fusarium Wilt Incidence

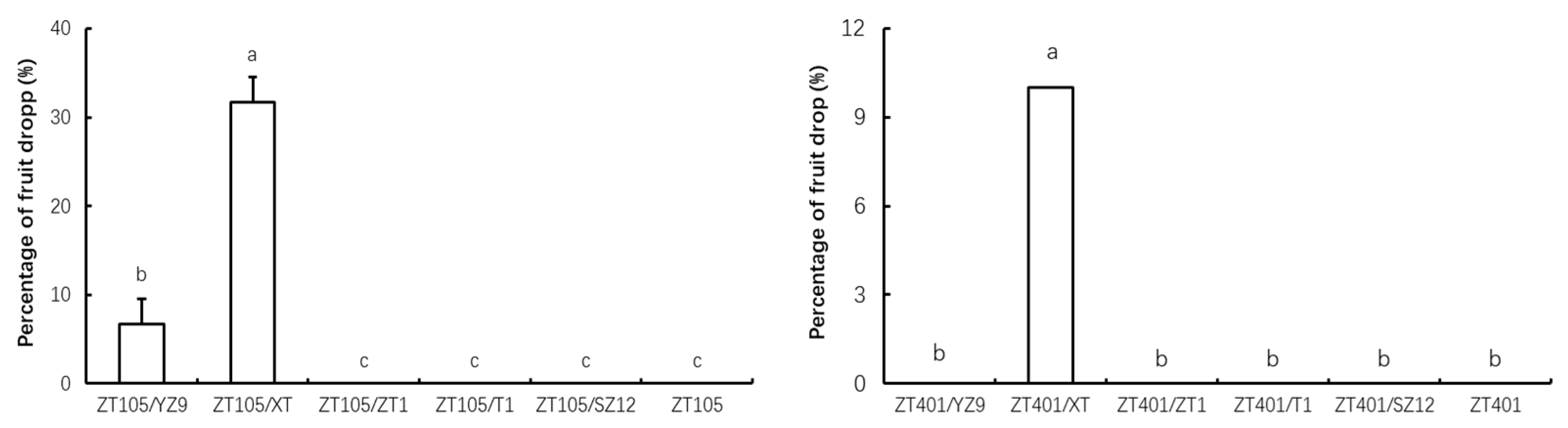

3.2. Mature Fruit Abscission

3.3. Flowering and Fruit Maturity

| Grafted combinations | Days to pistillate flowering (days after transplant DAT) |

Days to commercial ripening (days after pollination DAP) |

|---|---|---|

| ZT105/YZ9 | 41 | 40 |

| ZT105/XT | 39 | 38 |

| ZT105/ZT1 | 40 | 39 |

| ZT105/T1 | 40 | 39 |

| ZT105/SZ12 | 42 | 42 |

| ZT105 | 40 | 39 |

| ZT401/YZ9 | 42 | 43 |

| ZT401/XT | 41 | 42 |

| ZT401/ZT1 | 42 | 43 |

| ZT401/T1 | 42 | 43 |

| ZT401/SZ12 | 44 | 45 |

| ZT401 | 42 | 43 |

3.4. Fruit External Characteristics

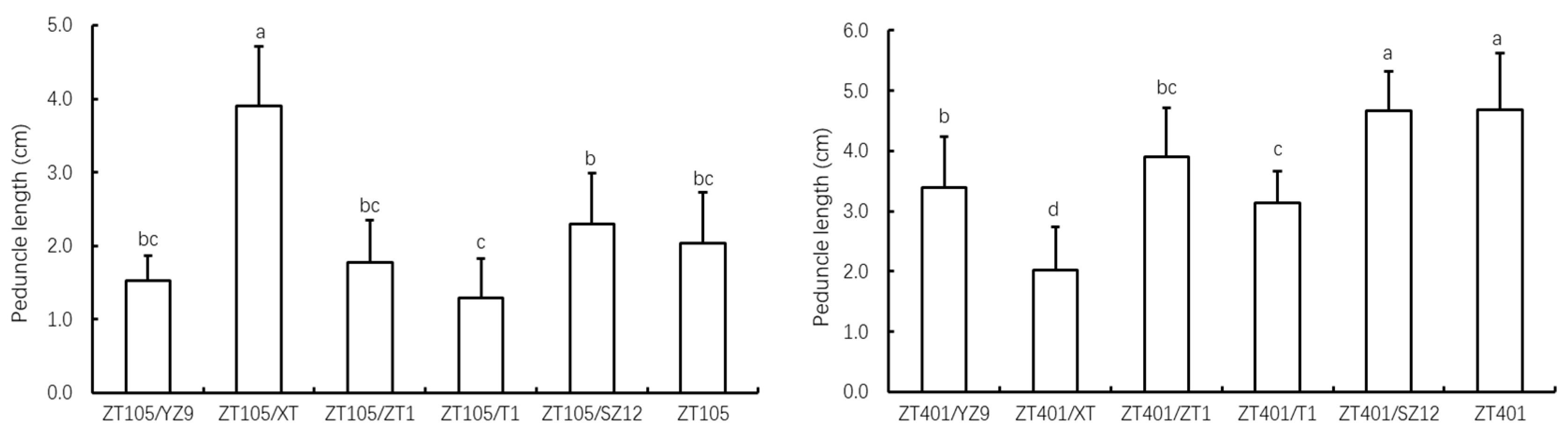

3.4.1. Peduncle Length

3.4.2. Fruit Size and Fruit Shape

3.5. Fruit Internal Quality

3.5.1. SSC and Sensory Sweetness

3.5.2. Fruit Texture

3.5.3. Flavor Quality

3.6. Fruit Yield

3.6.1. Single Fruit Weight

3.6.2. Fruit Number and Yield

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SSC | total Soluble Solid Content |

| MFA | Mature fruit abscission |

References

- Cohen, R.; Burger, Y.; Horev, C.; Koren, A.; Edelstein, M. Introducing grafted cucurbits to modern agriculture: the israeli experience. Plant Dis. 2007, 91, 916–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- San Bautista, A.; Calatayud, A.; Nebauer, S.G.; Pascual, B.; Maroto, J.V.; López-Galarza, S. Effects of simple and double grafting melon plants on mineral absorption, photosynthesis, biomass and yield. Sci. Hortic. 2011, 130, 575–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Wu, Y.; Chen, S.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, W.; Sun, X.; Zhao, Y. Using cucurbita rootstocks to reduce fusarium wilt incidence and increase fruit yield and carotenoid content in oriental melons. Hortscience 2014, 49, 1136–1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, W.; Zhao, X.; Huber, D.J.; Sims, C.A. Instrumental and sensory analyses of quality attributes of grafted specialty melons. J. Sci. Food. Agric. 2015, 95, 2989–2995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hai, R. Study on grafting seedling technology of muskmelon. MA thesis, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou, Zhejiang.

- Tian, S.; Diao, Q.; Cao, Y.; Yao, D.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, H.; Du, X.; Zhang, Y. Overview of research on virus-resistant breeding of melon. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Traka-Mavrona, E.; Koutsika-Sotiriou, M.; Pritsa, T. Response of squash (cucurbita spp.) As rootstock for melon (cucumis melo l.). Sci. Hortic. 2000, 83, 353–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, E.; Pollock, R.; Elkner, T.; Butzler, T.; Di Gioia, F. Fruit yield and physicochemical quality evaluation of hybrid and grafted field-grown muskmelon in pennsylvania. Horticulturae 2021, 7, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lecholocholo, N.; Shoko, T.; Manhivi, V.E.; Maboko, M.M.; Akinola, S.A.; Sivakumar, D. Influence of different rootstocks on quality and volatile constituents of cantaloupe and honeydew melons (cucumis melo. L) grown in high tunnels. Food Chem. 2022, 393, 133388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fita, A.; Picó, B.; Roig, C.; Nuez, F. Performance of cucumis melo ssp.agrestis as a rootstock for melon. The Journal of Horticultural Science and Biotechnology 2007, 82, 184–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, J.; Wang, J.; Li, N.; Ma, S. Research on the compatibility of grafted melon of different stocks. China Cucurbits Veg 2016, 29, 38–40. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, L.; Li, R.; Zeng, N.; Zhang, L.; Gao, P.; Li, P.; Liu, P.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, S. Evaluation of squash rootstocks for muskmelon production. J. Northern Agric 2016, 44, 38–41. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Yan, L.; Xing, N.; Gu, B.; Huang, Y.; Wang, Y. Effects of grafting on the prevention of monosporascus cannonballus and fruit quality in melon. J. Zhejiang Agric. Sci 2021, 62, 2051–2053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Fu, Q.; Zhu, H.; Wang, B. Effects of grafting on melon fruit growth and quality. China Veg 2014, 6, 13–19. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Lin, T.; Zhang, K.; Jiang, S.; Ma, G. Effects of different rootstocks on the growth and fruit quality of melon. Acta Agric. Shanghai 2023, 39, 40–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Mao, J.; Li, J.; Zhai, W. Effects of different rootstock grafting on the growth, yield and fruit quality of muskmelon. Xinjiang Agricultural Sciences 2021, 58, 1048–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, B.; He, K.; Hong, M.; Zhang, S.; Yan, S. Effects of different grafting rootstocks on growth, yield and fruit quality of melon. J. Zhejiang Agric. Sci 2024, 65, 1088–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Cheng, F.; Sun, L.; Ji, G.; Li, P.; Huang, T.; Li, M. Effects of grafting with different rootstocks on growth and fruit quality of cucumis melo under continuous cropping. Shandong Agric. Sci 2023, 55, 96. [Google Scholar]

- Bletsos, F.A. Use of grafting and calcium cyanamide as alternatives to methyl bromide soil fumigation and their effects on growth, yield, quality and fusarium wilt control in melon. J. Phytopathol. 2005, 153, 155–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.; Wang, C.; Zhao, X.; Xiao, S.; Chen, W.; Sun, J.; Jiao, Z. Influences of different grafting methods on the plant growth and fruit characters of muskmelon. China Cucurbits Veg 2017, 30, 34–37. [Google Scholar]

- Dai, J.; Wang, J.; Li, N.; Li, D.; Xu, D. Effects of different rootstock grafting on the growth characteristics of thin skin melon. China Cucurbits Veg 2024, 37, 88–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.E.; Zhang, H.F.; Ying, Q.S.; Yan, Y.L.; Wang, Y.H. Screening of rootstocks for autumn production “xuelihong’’ melon in ningbo. China Cucurbits Veg 2012, 25, 33–35. [Google Scholar]

- Kandemir, D. The selection of intra-inter specific cucurbita rootstocks for grafted melon seedlings. Emir. J. Food Agric. 2023, 35, 826–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, M.; Liu, C.; Guo, L.; Wang, J.; Wu, X.; Li, L.; Bie, Z.; Huang, Y. Compatibility evaluation and anatomical observation of melon grafted onto eight cucurbitaceae species. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Condurso, C.; Verzera, A.; Dima, G.; Tripodi, G.; Crinò, P.; Paratore, A.; Romano, D. Effects of different rootstocks on aroma volatile compounds and carotenoid content of melon fruits. Sci. Hortic. 2012, 148, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esteras, C.; Rambla, J.L.; Sánchez, G.; López Gresa, M.P.; González Mas, M.C.; Fernández Trujillo, J.P.; Bellés, J.M.; Granell, A.; Picó, M.B. Fruit flesh volatile and carotenoid profile analysis within thecucumis melo l. Species reveals unexploited variability for future genetic breeding. J. Sci. Food. Agric. 2018, 98, 3915–3925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Y.; Li, W.; Zhao, L.; Shen, T.; Sun, J.; Chen, H.; Kong, Q.; Nawaz, M.A.; Bie, Z. Melon fruit sugar and amino acid contents are affected by fruit setting method under protected cultivation. Sci. Hortic. 2017, 214, 288–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, A.R.; Perkins-Veazie, P.; Hassell, R.; Levi, A.; King, S.R.; Zhang, X. Grafting effects on vegetable quality. Hortscience 2008, 43, 1670–1672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaleem, M.M.; Nawaz, M.A.; Ding, X.; Wen, S.; Shireen, F.; Cheng, J.; Bie, Z. Comparative analysis of pumpkin rootstocks mediated impact on melon sensory fruit quality through integration of non-targeted metabolomics and sensory evaluation. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2022, 192, 320–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakata, Y.; Ohara, T.; Sugiyama, M. The history and present state of the grafting of cucurbitaceous vegetables in japan. PROCEEDINGS OF THE IIIRD INTERNATIONAL SYMPOSIUM ON CUCURBITS 2007, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, A.R.; Perkins-Veazie, P.; Sakata, Y.; López-Galarza, S.; Maroto, J.V.; Lee, S.; Huh, Y.; Sun, Z.; Miguel, A.; King, S.R.; et al. Cucurbit grafting. Crit. Rev. Plant Sci. 2008, 27, 50–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devi, P.; Perkins-Veazie, P.; Miles, C. Impact of grafting on watermelon fruit maturity and quality. Horticulturae 2020, 6, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyriacou, M.C.; Leskovar, D.I.; Colla, G.; Rouphael, Y. Watermelon and melon fruit quality: the genotypic and agro-environmental factors implicated. Sci. Hortic. 2018, 234, 393–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soteriou, G.A.; Papayiannis, L.C.; Kyriacou, M.C. Indexing melon physiological decline to fruit quality and vine morphometric parameters. Sci. Hortic. 2016, 203, 207–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colla, G.; Suarez, C.M.C.; Cardarelli, M.; Rouphael, Y. Improving nitrogen use efficiency in melon by grafting. Hortscience 2010, 45, 559–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Nie, L.; Zhao, W.; Cui, Q.; Wang, J.; Duan, Y.; Ge, C. Metabolomic analysis of the occurrence of bitter fruits on grafted oriental melon plants. PLoS One 2019, 14, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verzera, A.; Dima, G.; Tripodi, G.; Condurso, C.; Crinò, P.; Romano, D.; Mazzaglia, A.; Lanza, C.M.; Restuccia, C.; Paratore, A. Aroma and sensory quality of honeydew melon fruits (cucumis melo l. Subsp. Melo var. Inodorus h. Jacq.) In relation to different rootstocks. Sci. Hortic. 2014, 169, 118–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camalle, M.D.; Pivonia, S.; Zurgil, U.; Fait, A.; Zur, N.T. Rootstock identity in melon- pumpkin graft combinations determines fruit metabolite profile. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 13, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saftner, R.; Abbott, J.A.; Lester, G.; Vinyard, B. Sensory and analytical comparison of orange-fleshed honeydew to cantaloupe and green-fleshed honeydew for fresh-cut chunks. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2006, 42, 150–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pardo, J.E.; Alvarruiz, A.; Varón, R.; Gómez, R. Quality evaluation of melon cultivars. Correlation among physical-chemical and sensory parameters. J. Food Qual. 2000, 23, 161–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyriacou, M.C.; Rouphael, Y.; Colla, G.; Zrenner, R.; Schwarz, D. Vegetable grafting: the implications of a growing agronomic imperative for vegetable fruit quality and nutritive value. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yetışır, H.; Sari, N.; Yücel, S. Rootstock resistance to fusarium wilt and effect on watermelon fruit yield and quality. Phytoparasitica 2003, 31, 163–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soteriou, G.A.; Siomos, A.S.; Gerasopoulos, D.; Rouphael, Y.; Georgiadou, S.; Kyriacou, M.C. Biochemical and histological contributions to textural changes in watermelon fruit modulated by grafting. Food Chem. 2017, 237, 133–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dabirian, S.; Inglis, D.; Miles, C.A. Grafting watermelon and using plastic mulch to control verticillium wilt caused by verticillium dahliae in washington. Hortscience 2017, 52, 349–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colla, G.; Rouphael, Y.; Cardarelli, M.; Massa, D.; Salerno, A.; Rea, E. Yield, fruit quality and mineral composition of grafted melon plants grown under saline conditions. J. Horticult. Sci. Biotechnol. 2006, 81, 146–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, W.; Zhao, X.; Dickson, D.W.; Mendes, M.L.; Thies, J. Root - knot nematode resistance, yield, and fruit quality of specialty melons grafted onto cucumis metulifer. Hortscience 2014, 49, 1046–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouphael, Y.; Schwarz, D.; Krumbein, A.; Colla, G. Impact of grafting on product quality of fruit vegetables. Sci. Hortic. 2010, 127, 172–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, S.; Zhao, S.; Wang, C.; Dong, Y.; Jiao, Z.; Sun, S.X.E. Influences of grafting on aromatic compounds in muskmelon by solid phase microextraction with gc-ms. In IV International Symposium on Cucurbits, 2010365–375.

- Lee, J.M.; Oda, M. Grafting of herbaceous vegetable and ornamental crops. Horticultural Reviews 2003, 28, 61–124. [Google Scholar]

- Crino, P.; Bianco, C.L.; Rouphael, Y.; Colla, G.; Saccardo, F.; Paratore, A. Evaluation of rootstock resistance to fusarium wilt and gummy stem blight and effect on yield and quality of a grafted 'inodorus' melon. Hortscience 2007, 42, 521–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Experiment | Muskmelon cultivars | Rootstocks | Grafted combinations |

|---|---|---|---|

| A | ZT105 | YZ9 | ZT105/YZ9 |

| ZT105 | XT | ZT105/XT | |

| ZT105 | ZT | ZT105/ZT | |

| ZT105 | T1 | ZT105/ZT | |

| ZT105 | SZ12 | ZT105/SZ12 | |

| ZT105 | - | ZT105 (control) | |

| B | ZT401 | YZ9 | ZT401/YZ9 |

| ZT401 | XT | ZT401/XT | |

| ZT401 | ZT | ZT401/ZT | |

| ZT401 | T1 | ZT401/ZT | |

| ZT401 | SZ12 | ZT401/SZ12 | |

| ZT401 | - | ZT401 (control) |

| Grafted combinations | fruit length | fruit diameter | fruit shape | flesh thickness |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ZT105/YZ9 | 17.93±0.81 ab | 12.87±0.45 a | 1.40±0.09 a | 4.05±0.33 a |

| ZT105/XT | 18.55±0.69 a | 12.83±0.49 a | 1.45±0.08 a | 4.15±0.28 a |

| ZT105/ZT1 | 18.84±0.90 a | 12.87±0.52 a | 1.47±0.08 a | 4.21±0.40 a |

| ZT105/T1 | 17.67±0.66 b | 12.55±0.54 a | 1.41±0.05 a | 4.08±0.62 a |

| ZT105/SZ12 | 18.71±0.89 a | 12.68±0.48 a | 1.48±0.08 a | 4.25±0.31 a |

| ZT105 | 18.71±0.56 a | 12.68±0.57 a | 1.48±0.05 a | 4.15±0.31 a |

| ZT401/YZ9 | 17.17±0.93 a | 11.63±0.37 a | 1.48±0.09 a | 3.82±0.29 a |

| ZT401/XT | 16.86±1.04 a | 12.17±0.60 a | 1.39±0.07 a | 3.81±0.13 a |

| ZT401/ZT1 | 17.32±1.13 a | 12.02±0.42 a | 1.44±0.08 a | 3.88±0.27 a |

| ZT401/T1 | 17.44±1.15 a | 11.84±0.44 a | 1.47±0.10 a | 3.71±0.30 a |

| ZT401/SZ12 | 17.17±0.71 a | 12.14±0.41 a | 1.41±0.04 a | 3.89±0.20 a |

| ZT401 | 18.14±0.97 a | 12.25±0.50 a | 1.48±0.06 a | 3.79±0.18 a |

| Grafted combinations |

SSC (%) | Sweetness | Texture | Pumpkin flavor |

Aroma |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ZT105/YZ9 | 19.13±1.14 a | 8.33±0.96 a | 8.00±1.02 a | 1.00±0.00 b | 1.07±0.37 b |

| ZT105/XT | 18.13±0.85 a | 8.27±1.11 a | 7.87±1.01 a | 1.00±0.00 b | 3.27±1.01 a |

| ZT105/ZT1 | 18.34±0.70 a | 8.20±1.13 a | 8.07±1.01 a | 1.00±0.00 b | 1.00±0.00 b |

| ZT105/T1 | 18.39±1.07 a | 8.07±1.01 a | 7.93±1.11 a | 1.00±0.00 b | 1.00±0.00 b |

| ZT105/SZ12 | 18.11±0.86 a | 8.00±1.02 a | 8.33±0.96 a | 1.13±0.51 a | 1.00±0.00 b |

| ZT105 | 18.65±0.69 a | 8.27±1.11 a | 8.20±1.00 a | 1.00±0.00 b | 1.00±0.00 b |

| ZT401/YZ9 | 18.28±0.55 a | 7.87±1.01 a | 4.00±1.02 a | 1.00±0.00 b | 1.00±0.00 b |

| ZT401/XT | 18.01±0.74 a | 7.53±1.04 a | 3.80±1.00 a | 1.00±0.00 b | 1.27±0.69a |

| ZT401/ZT1 | 18.00±1.05 a | 7.80±1.00 a | 3.93±1.01 a | 1.00±0.00 b | 1.00±0.00 b |

| ZT401/T1 | 17.68±1.07 a | 7.67±1.09 a | 3.87±1.01 a | 1.00±0.00 b | 1.00±0.00 b |

| ZT401/SZ12 | 17.42±0.97 a | 7.60±0.93 a | 4.20±1.00 a | 4.53±1.80 a | 1.00±0.00 b |

| ZT401 | 17.56±0.61 a | 7.73±0.98 a | 4.00±1.02 a | 1.00±0.00 b | 1.00±0.00 b |

| Grafted Combinations |

Average Fruit Weight (kg) | Fruit Number Per Plot |

Fresh Weight Yield Per Plot(kg) |

|---|---|---|---|

| ZT105/YZ9 | 1.59±0.15 a | 17.00±1.0 b | 25.71±1.45 b |

| ZT105/XT | 1.67±0.11 a | 13.00±1.0 c | 21.18±1.15 c |

| ZT105/ZT1 | 1.62±0.15 a | 18.33±0.6 ab | 28.41±0.63 a |

| ZT105/T1 | 1.54±0.13 a | 18.67±0.6 a | 25.97±1.60 ab |

| ZT105/SZ12 | 1.67±0.13 a | 17.67±0.6 ab | 28.01±1.69 ab |

| ZT105 | 1.62±0.09 a | 14.33±0.6 c | 22.30±0.35 c |

| ZT401/YZ9 | 1.19±0.14 a | 35.00±1.0 a | 40.46±1.55 b |

| ZT401/XT | 1.31±0.11 a | 30.67±1.2 b | 39.35±1.76 bc |

| ZT401/ZT1 | 1.28±0.11 a | 35.33±0.6 a | 43.35±1.38 a |

| ZT401/T1 | 1.21±0.06 a | 36.67±1.5 a | 42.64±1.40 ab |

| ZT401/SZ12 | 1.30±0.10 a | 36.00±1.0 a | 44.53±0.64 a |

| ZT401 | 1.32±0.13 a | 29.00±1.0 c | 36.73±1.18 c |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).