Submitted:

02 January 2025

Posted:

03 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Motivation of the Research

1.2. Literature Review

1.3. Original Contributions

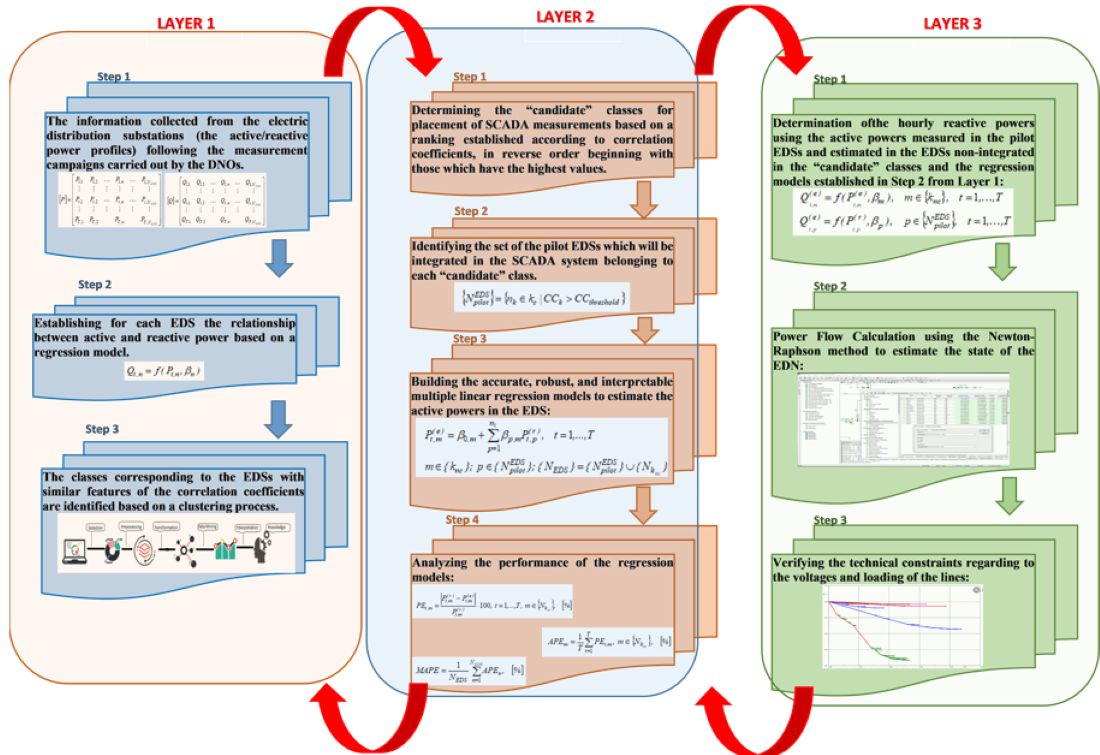

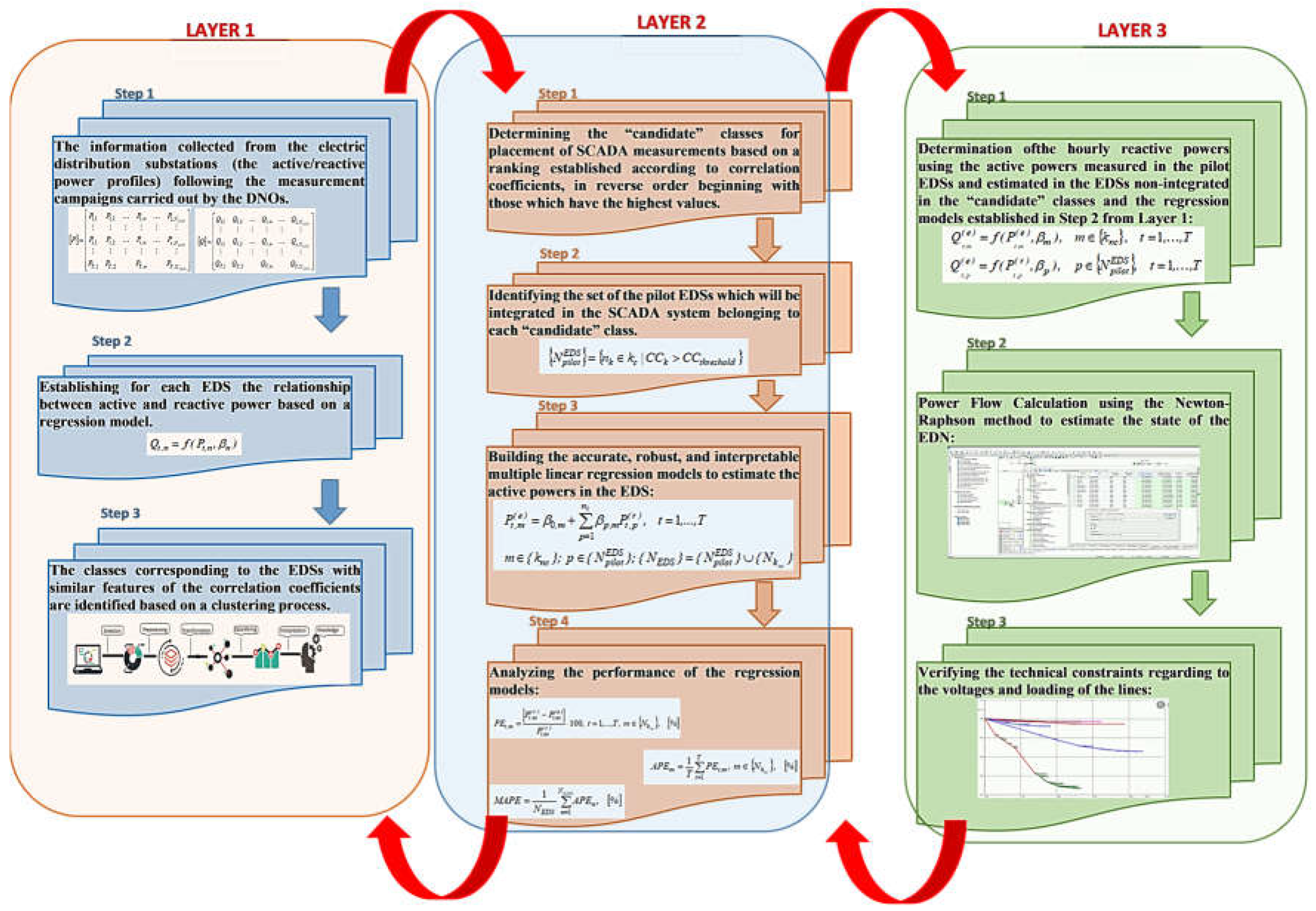

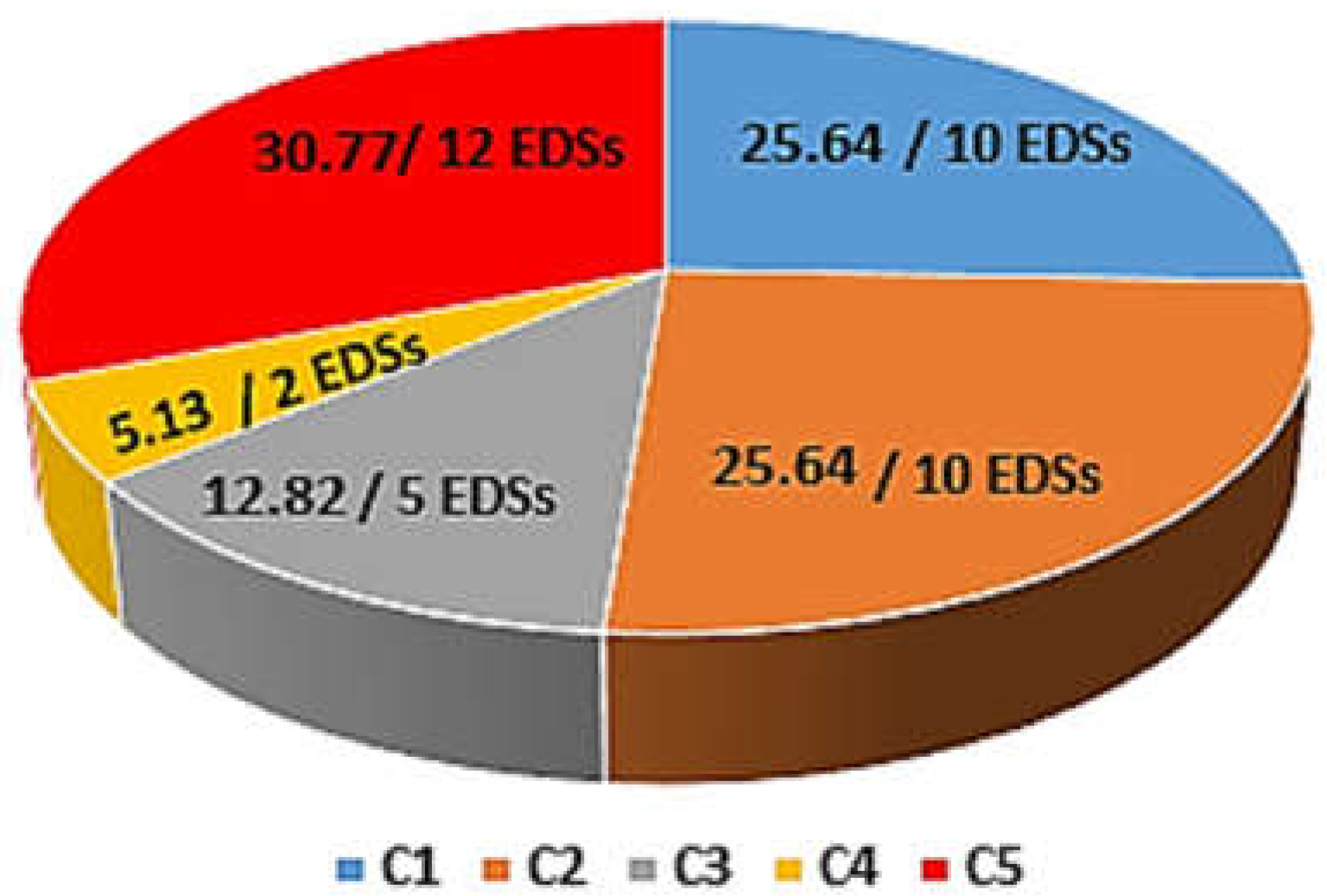

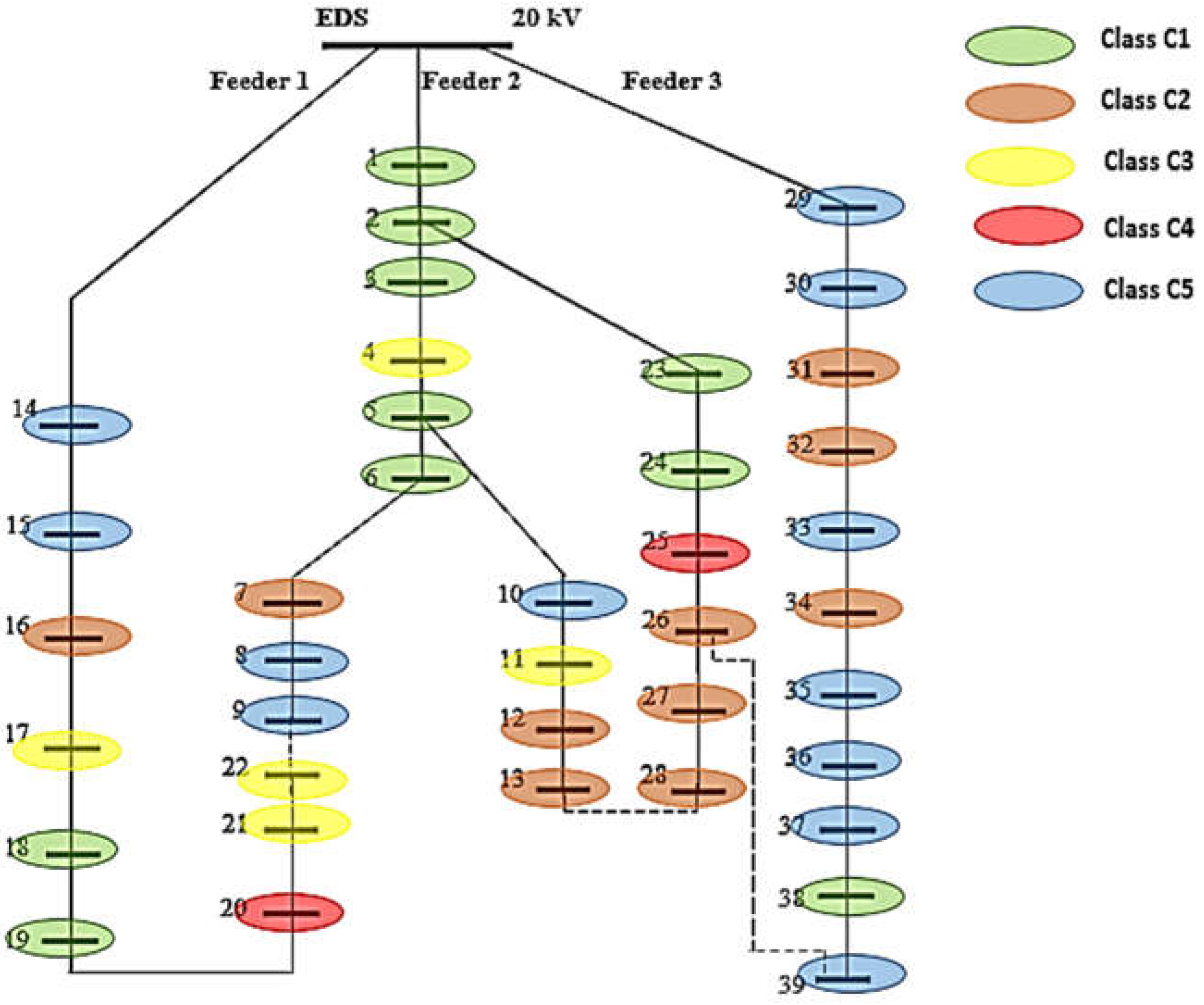

- The first layer allows the determination of the classes of the EDSs with similar features from the viewpoint of requested loads based on the K-means clustering algorithm.

- The second layer identifies the "candidate" classes and the pilot EDSs (representing the optimal solution) with the SCADA measurements placed. The optimal placement corresponds to the minimization of the estimation errors obtained using the multiple linear regression models between the EDSs from the classes not included in the set of the "candidate" classes and the pilot EDSs.

- The third layer allows the state estimation of the EDNs based on the load values measured in the pilot EDEs (with the SCADA system implemented) and the other EDSs obtained through the regression models. Also, the layer contains a module that verifies that it satisfies all the technical constraints, having integrated the functions to implement the strategies for optimal operation of the EDNs.

1.4. Paper Structure

2. Materials and Methods

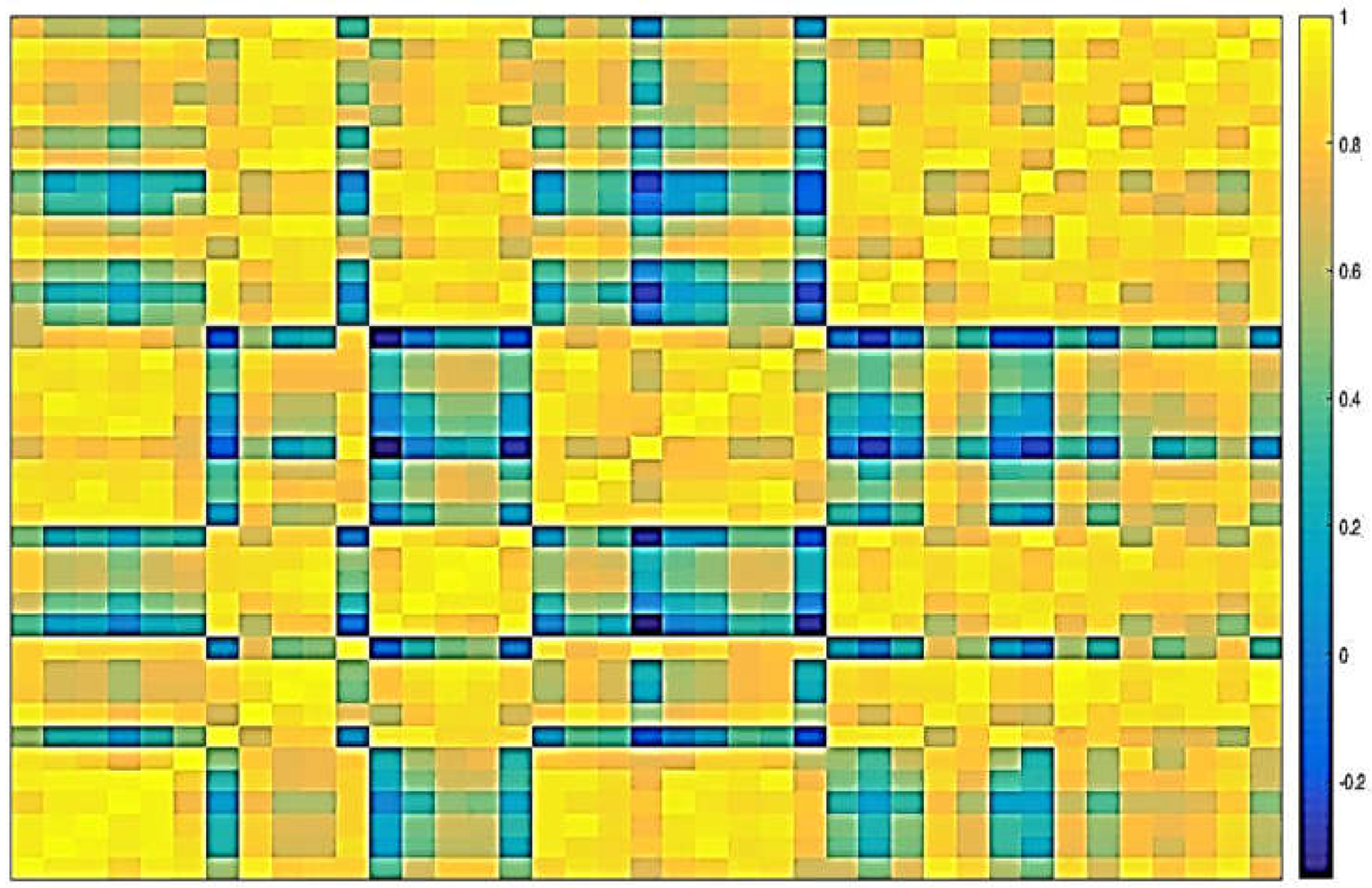

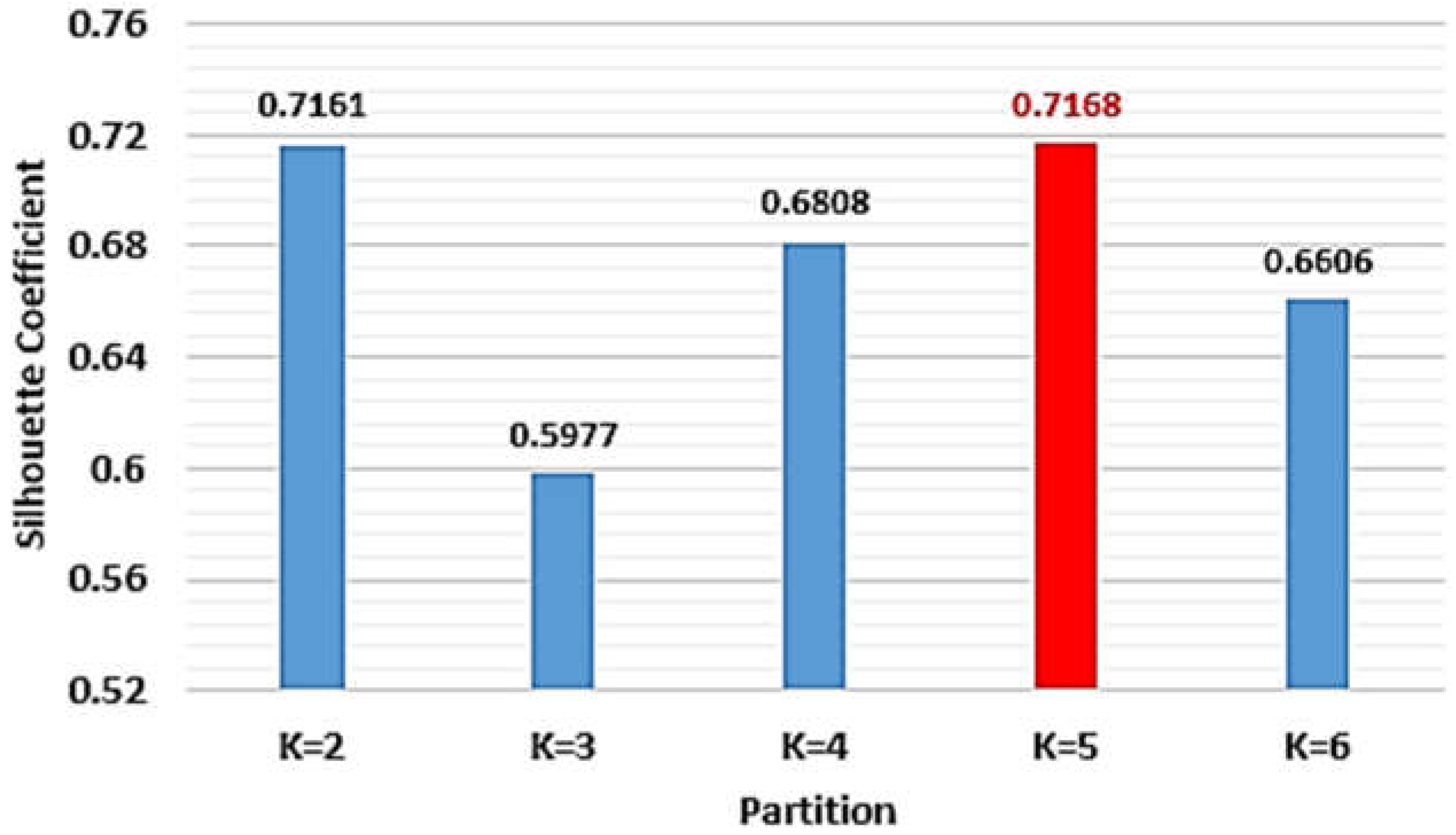

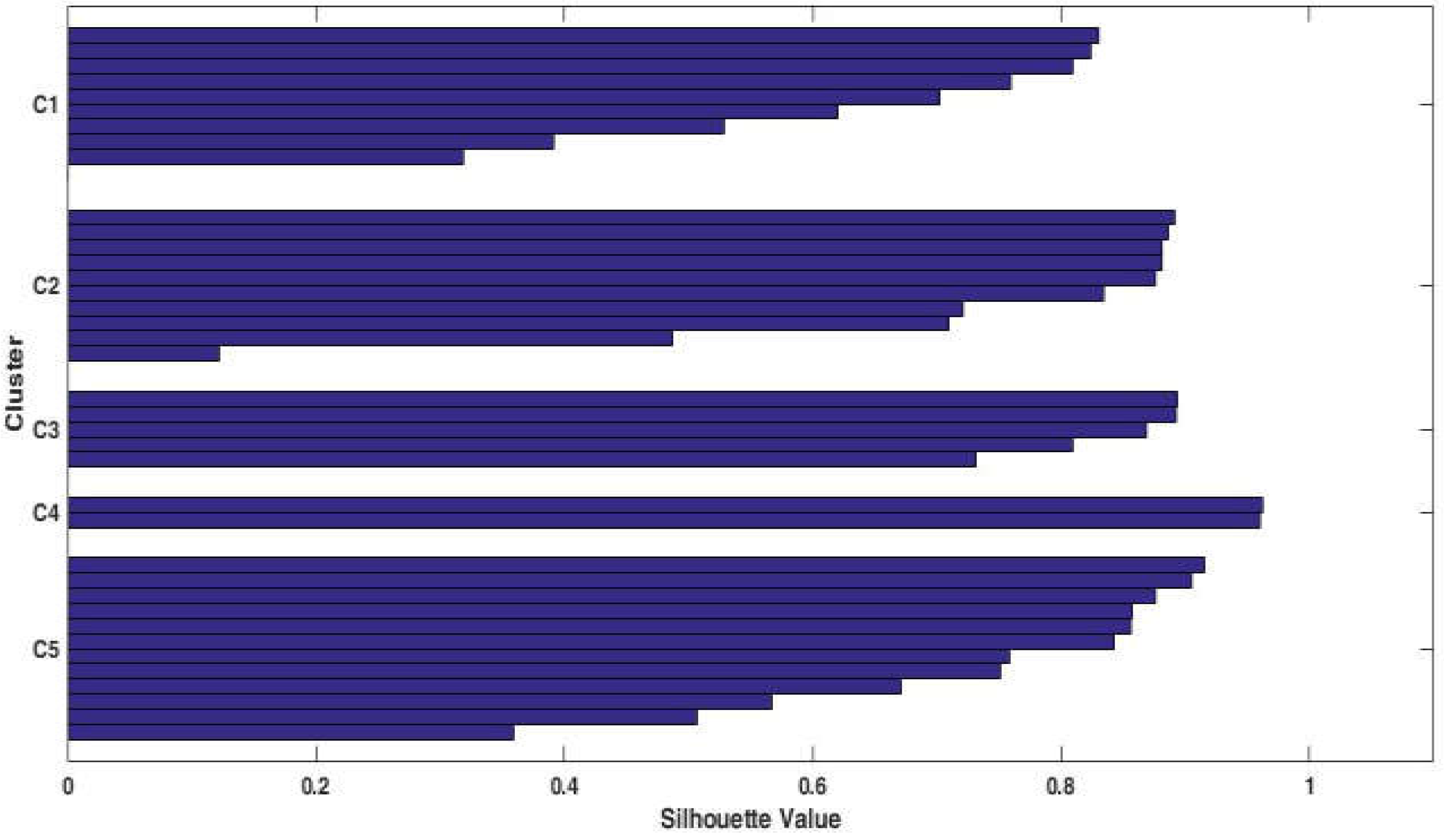

2.1. Layer 1

- The NEDS vectors associated with the columns of the matrix [CC] should be integrated into K classes:

- 2.

- Determination the maximum number in which the NEDS electric distribution substations can be distributed using the relation [22]:

- 3.

- The vectors CCn, n = 1, …, NEDS, will be randomly assigned in the K classes of the EDSs.

- 4.

- The centroids Ck, k = 1, …, K and K = 2, …, Kmax, representing vectors with the size (NEDSx1) are calculated.

- 5.

- The repartition of the EDSs in in one of the K classes, K = 2, …, Kmax, will be based on the minimization of an objective function OF having the following expression:

- 6.

- The positions of the Ck centroids are re-adjusting through their recalculation using relation (7). In the case when all vectors CCn, n = 1, …, NEDS, are considered and re-labelled, Step 5 is repeated.

- 7.

- The silhouette coefficient for each partition K = 2, …, Kmax, will be calculated using the formula [23]:

- 8.

- The value of the silhouette coefficient SC(k) for each partition K = 2, …, Kmax is recorded in the vector [SC] and the maximum value is identified:

- 9.

- Determination of the optimal partition containing Kopt classes:

2.2. Layer 2

2.3. Layer 3

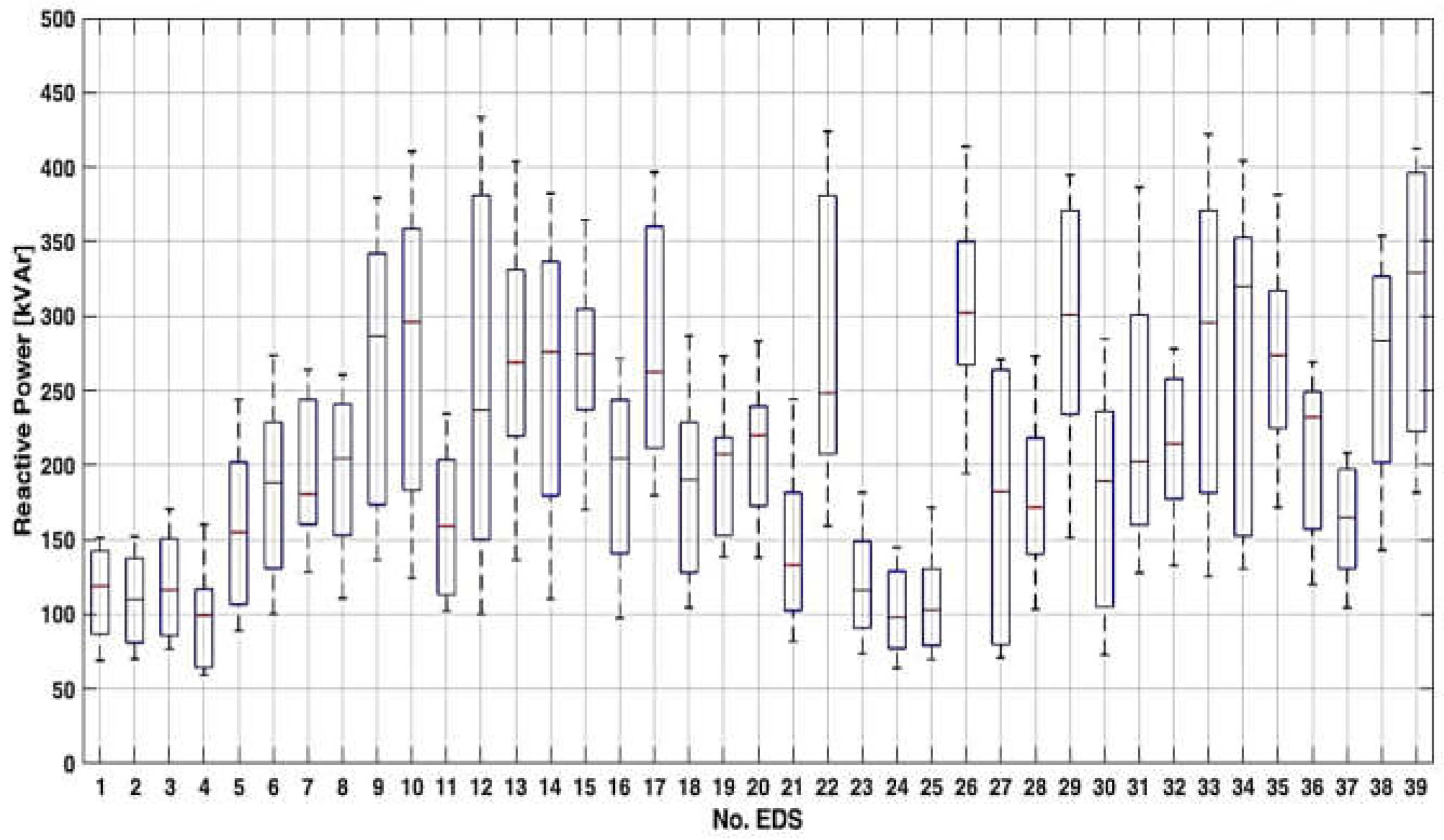

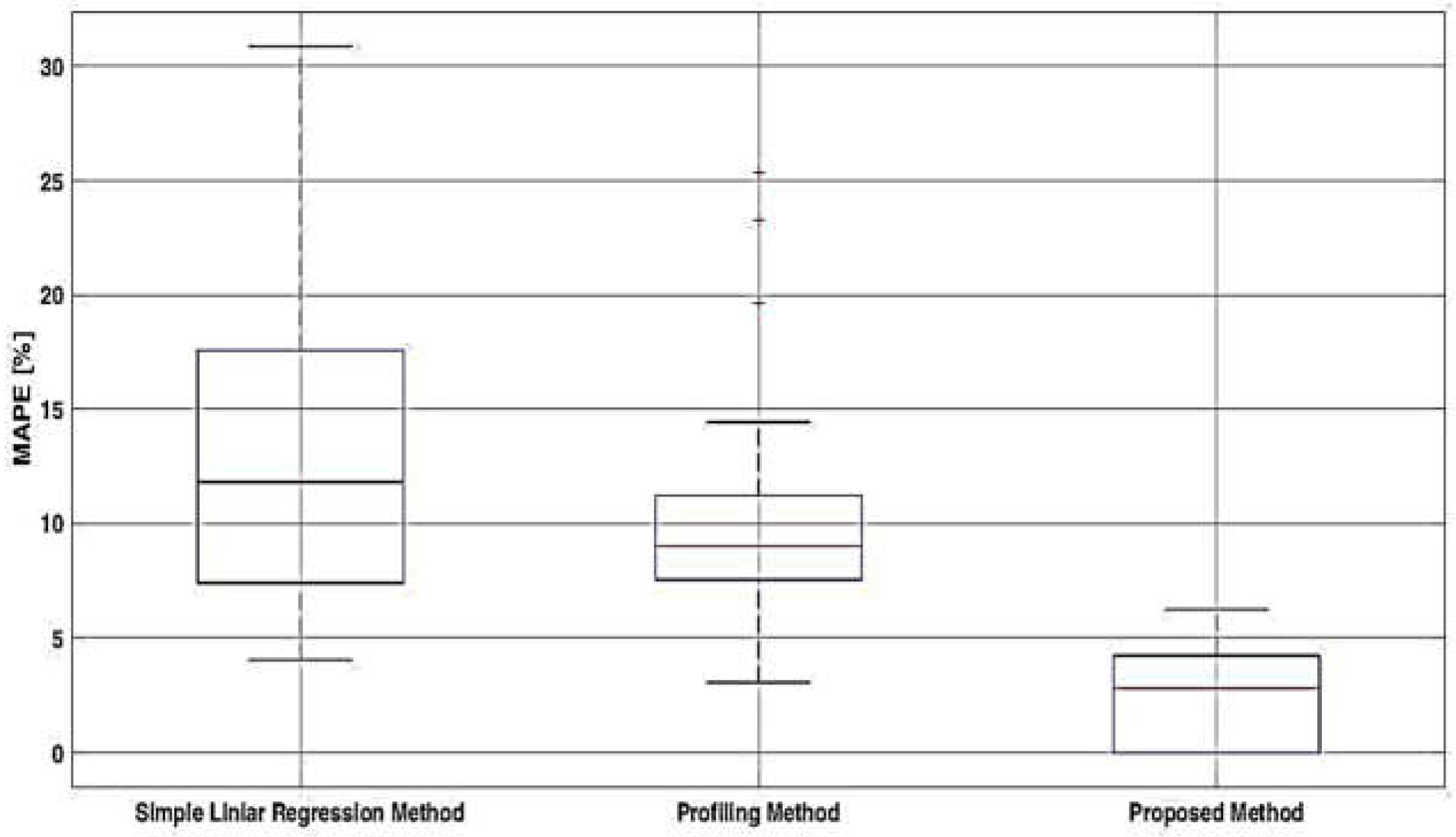

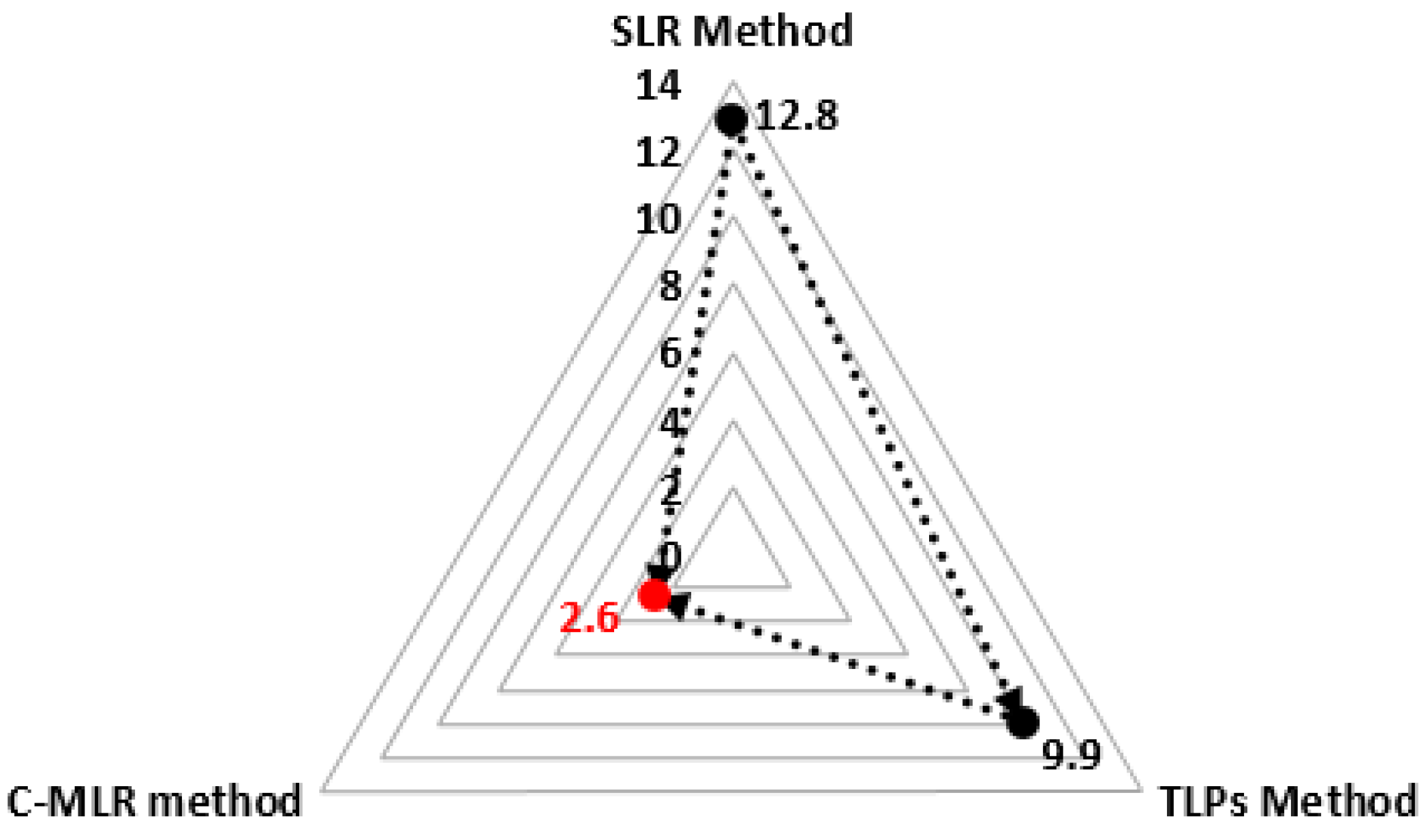

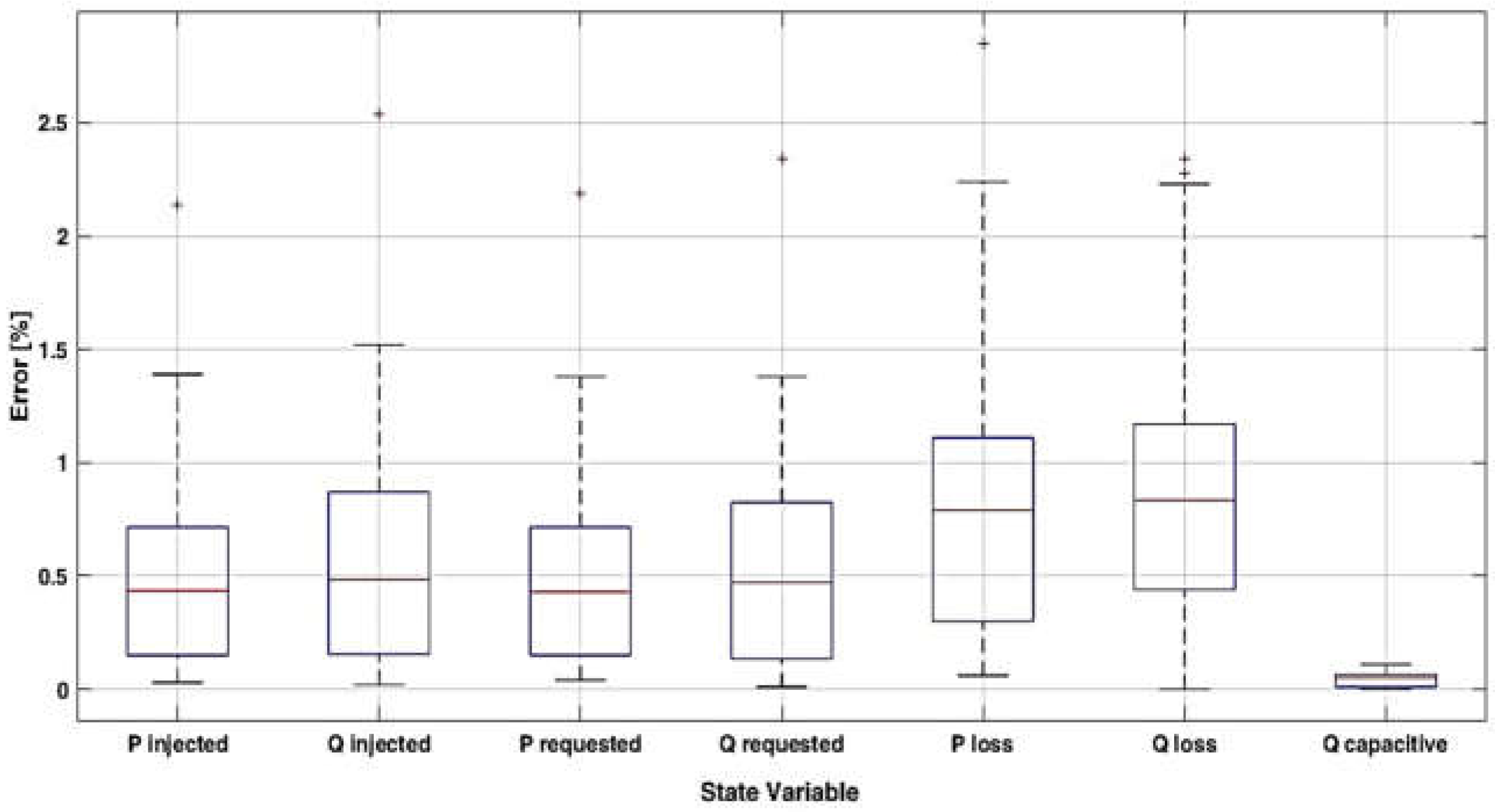

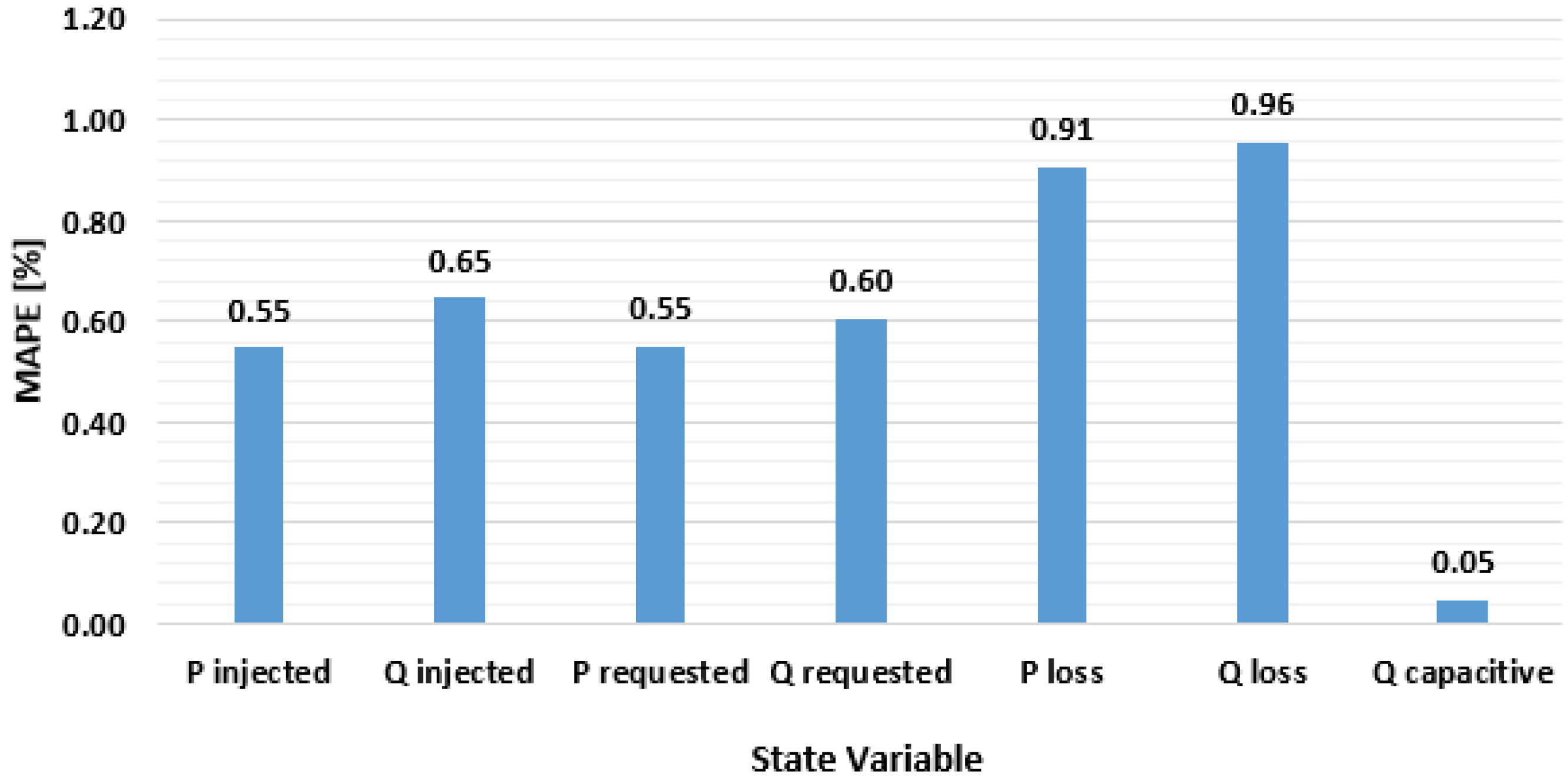

3. Results

4. Conclusions and Discussions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| EDN | electric distribution networks |

| DNO | distribution network operator |

| SCADA | supervisory, control, and acquisition system |

| EDS | electric distribution substations |

| MV | medium Voltage |

| HV | high Voltage |

| LV | low Voltage |

| RTU | remote terminal unit |

| MAPE | mean absolute percentage error |

| APE | average percentage error |

| PE | percentage error |

| SLR | simple linear regression |

| TLP | typical load profile |

| C-MLR | clustering-multiple linear regression |

Appendix A

| Branch |

Length [km] |

Feeder Allocated | Branch |

Length [mm2] |

Feeder Allocated | Branch |

Length [mm2] |

Feeder Allocated |

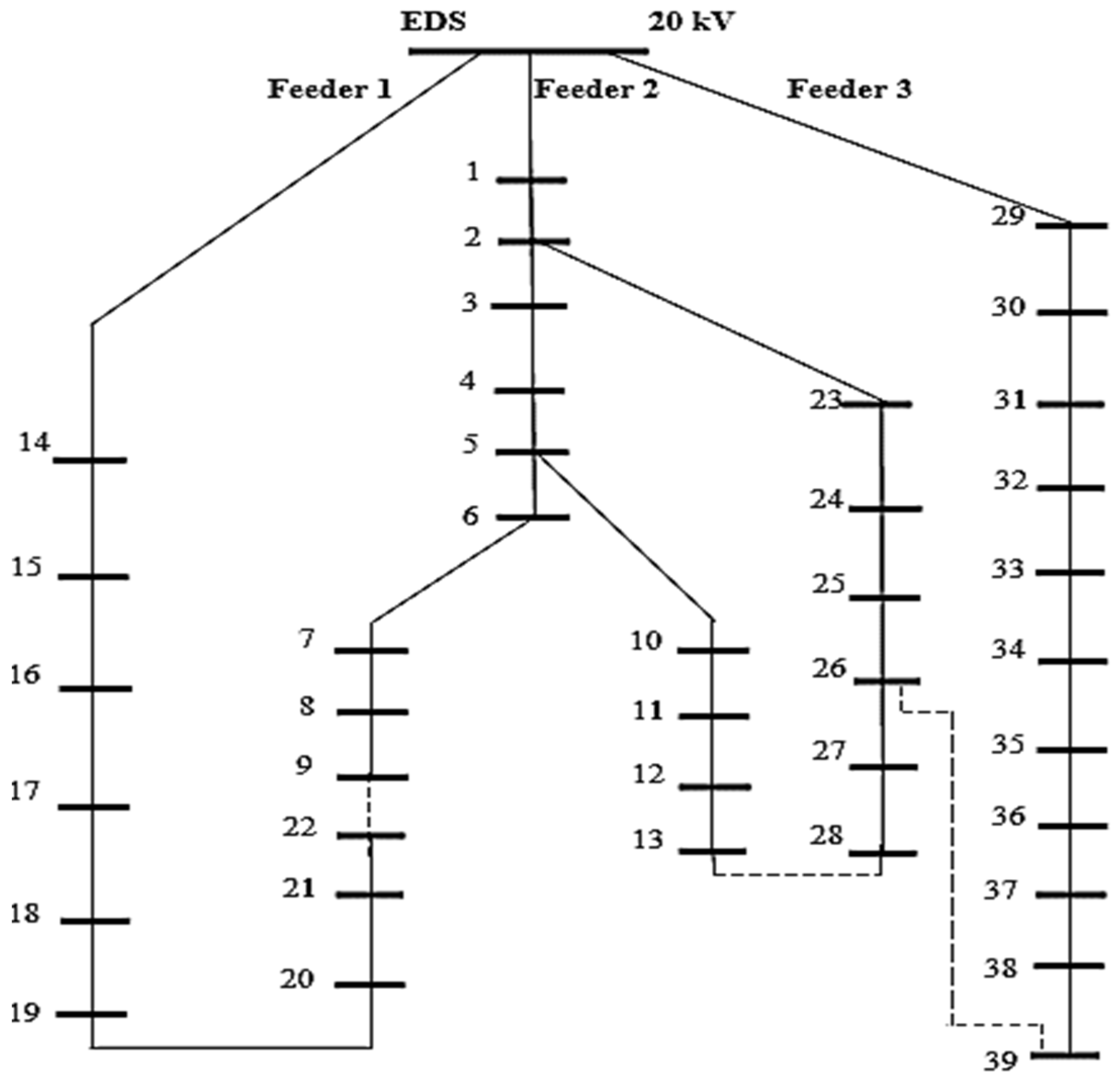

| EDS - 1 | 0.500 | Feeder 2 | 26 - 27 | 0.390 | Feeder 2 | 20 - 21 | 0.510 | Feeder 1 |

| 1 - 2 | 0.200 | Feeder 2 | 27 - 28 | 0.410 | Feeder 2 | 21 - 22 | 0.450 | Feeder 1 |

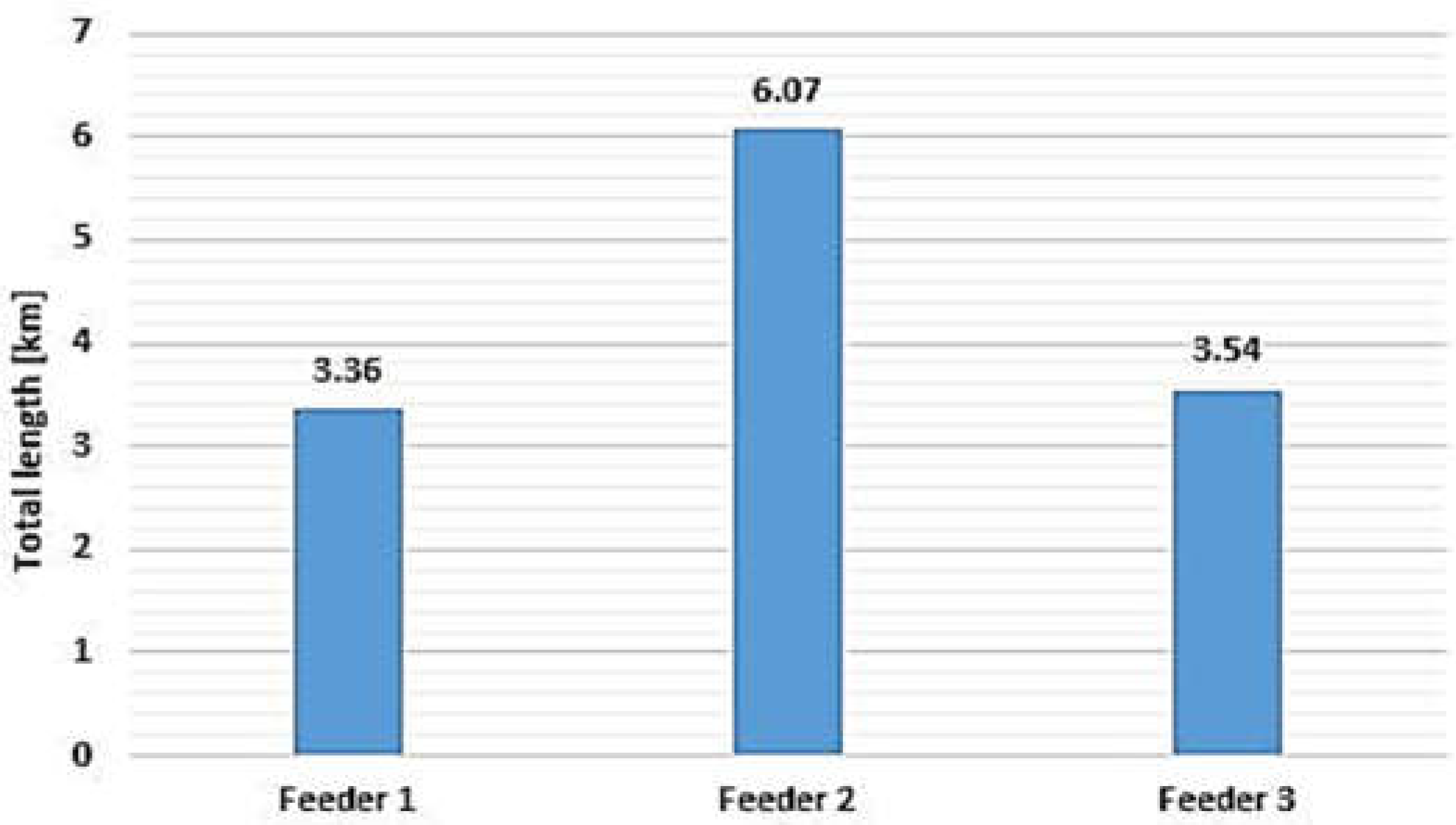

| 2 - 3 | 0.250 | Feeder 2 | 5 - 10 | 0.500 | Feeder 2 | EDS - 29 | 0.400 | Feeder 3 |

| 3 - 4 | 0.100 | Feeder 2 | 10 - 11 | 0.390 | Feeder 2 | 29 - 30 | 0.230 | Feeder 3 |

| 4 - 5 | 0.300 | Feeder 2 | 11 - 12 | 0.180 | Feeder 2 | 30 - 31 | 0.490 | Feeder 3 |

| 5 - 6 | 0.450 | Feeder 2 | 12 - 13 | 0.270 | Feeder 2 | 31 - 32 | 0.170 | Feeder 3 |

| 6 -7 | 0.280 | Feeder 2 | EDS - 14 | 0.600 | Feeder 1 | 32 - 33 | 0.340 | Feeder 3 |

| 7 - 8 | 0.310 | Feeder 2 | 14 - 15 | 0.180 | Feeder 1 | 33 - 34 | 0.480 | Feeder 3 |

| 8 - 9 | 0.210 | Feeder 2 | 15 - 16 | 0.290 | Feeder 1 | 34 - 35 | 0.210 | Feeder 3 |

| 2 - 23 | 0.350 | Feeder 2 | 16 - 17 | 0.350 | Feeder 1 | 35 - 36 | 0.350 | Feeder 3 |

| 23 - 24 | 0.260 | Feeder 2 | 17 - 18 | 0.230 | Feeder 1 | 36 - 37 | 0.370 | Feeder 3 |

| 24 - 25 | 0.400 | Feeder 2 | 18 - 19 | 0.400 | Feeder 1 | 37 - 38 | 0.210 | Feeder 3 |

| 25 - 26 | 0.320 | Feeder 2 | 19 - 20 | 0.350 | Feeder 1 | 38 - 39 | 0.290 | Feeder 3 |

| No. of EDS | Sr [kVA] | Feeder Allocated | No. of EDS | Sn [kVA] | Feeder Allocated | No. of EDS | Sn [kVA] | Feeder Allocated |

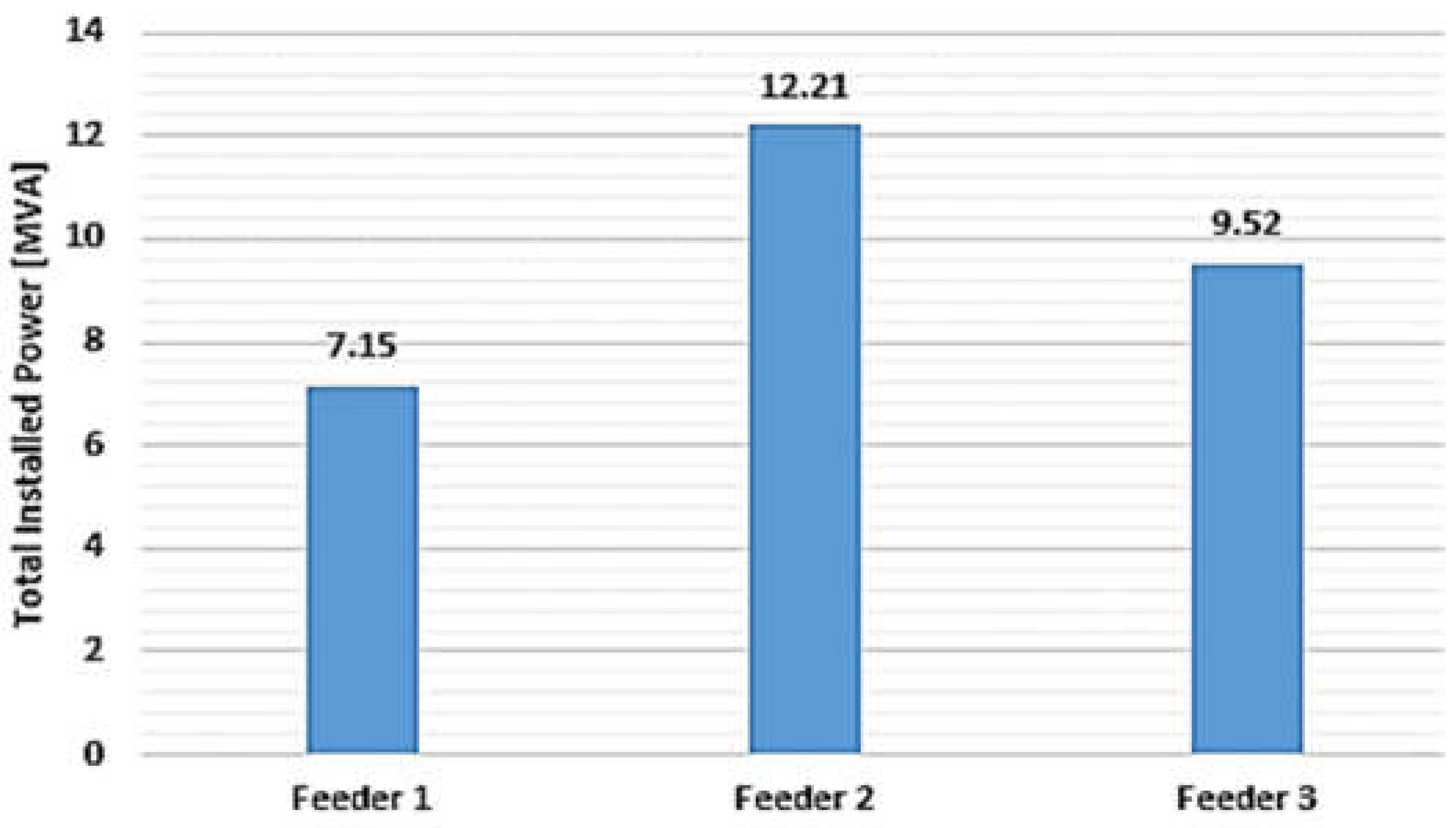

| 1 | 400 | Feeder 2 | 14 | 1000 | Feeder 1 | 27 | 630 | Feeder 2 |

| 2 | 400 | Feeder 2 | 15 | 1000 | Feeder 1 | 28 | 630 | Feeder 2 |

| 3 | 400 | Feeder 2 | 16 | 630 | Feeder 1 | 29 | 1000 | Feeder 3 |

| 4 | 400 | Feeder 2 | 17 | 1000 | Feeder 1 | 30 | 630 | Feeder 3 |

| 5 | 630 | Feeder 2 | 18 | 630 | Feeder 1 | 31 | 1000 | Feeder 3 |

| 6 | 630 | Feeder 2 | 19 | 630 | Feeder 1 | 32 | 630 | Feeder 3 |

| 7 | 630 | Feeder 2 | 20 | 630 | Feeder 1 | 33 | 1000 | Feeder 3 |

| 8 | 630 | Feeder 2 | 21 | 630 | Feeder 1 | 34 | 1000 | Feeder 3 |

| 9 | 1000 | Feeder 2 | 22 | 1000 | Feeder 1 | 35 | 1000 | Feeder 3 |

| 10 | 1000 | Feeder 2 | 23 | 400 | Feeder 2 | 36 | 630 | Feeder 3 |

| 11 | 630 | Feeder 2 | 24 | 400 | Feeder 2 | 37 | 630 | Feeder 3 |

| 12 | 1000 | Feeder 2 | 25 | 400 | Feeder 2 | 38 | 1000 | Feeder 3 |

| 13 | 1000 | Feeder 2 | 26 | 1000 | Feeder 2 | 39 | 1000 | Feeder 3 |

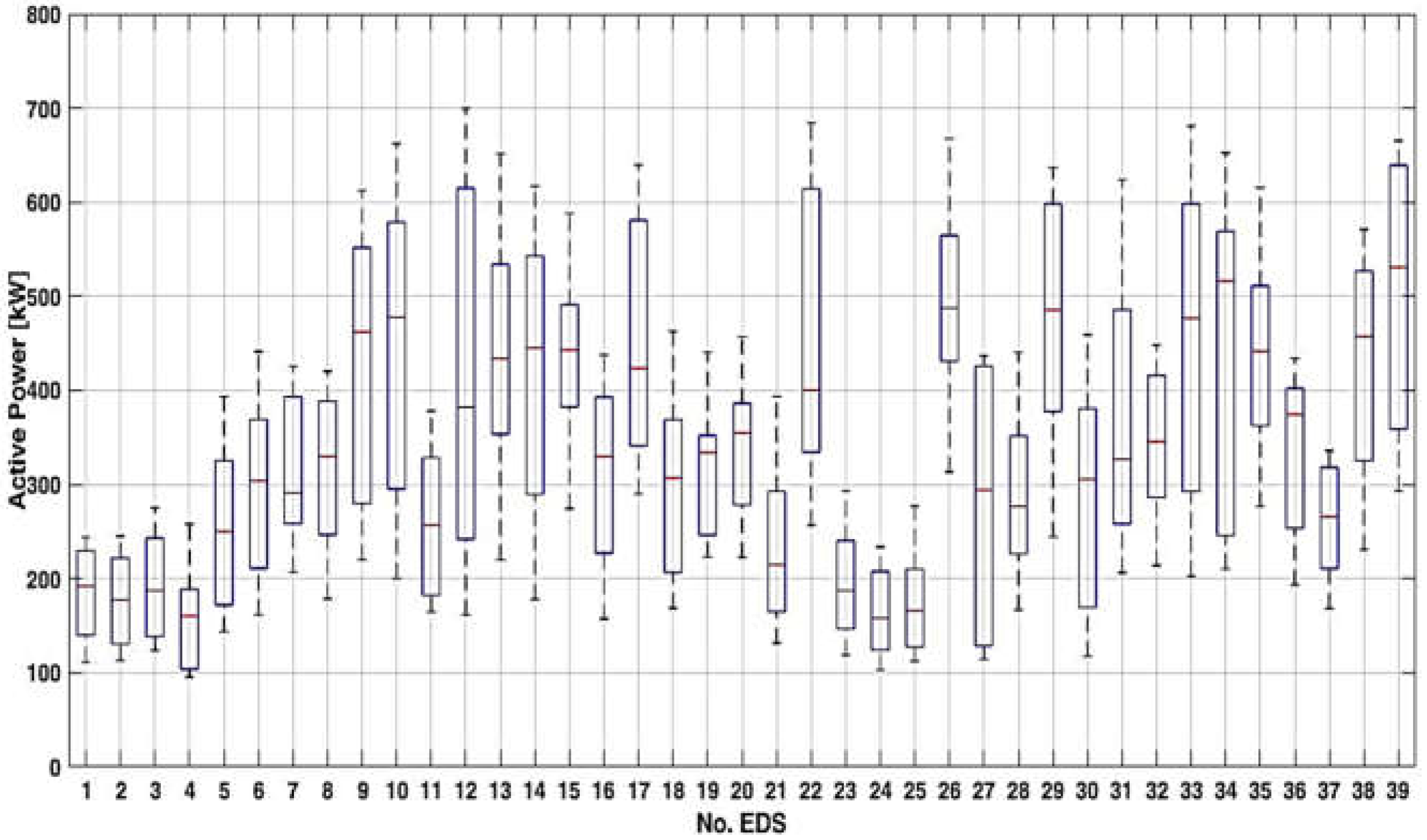

| No. EDS | Q0 | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | M | SD |

| 1 | 111.20 | 139.95 | 191.90 | 229.80 | 244.00 | 183.67 | 46.17 |

| 2 | 112.90 | 130.65 | 177.55 | 221.90 | 245.20 | 177.90 | 45.78 |

| 3 | 123.80 | 138.55 | 187.70 | 243.15 | 275.40 | 193.04 | 53.58 |

| 4 | 95.50 | 103.75 | 160.35 | 188.55 | 258.30 | 156.95 | 52.64 |

| 5 | 143.70 | 172.05 | 250.15 | 325.65 | 393.30 | 255.70 | 83.99 |

| 6 | 161.50 | 210.85 | 303.80 | 369.10 | 441.40 | 296.61 | 93.10 |

| 7 | 206.90 | 258.50 | 291.20 | 393.20 | 425.80 | 315.41 | 71.99 |

| 8 | 178.60 | 246.70 | 329.90 | 388.35 | 420.30 | 315.61 | 81.69 |

| 9 | 220.10 | 279.90 | 462.20 | 551.70 | 612.30 | 432.07 | 137.87 |

| 10 | 200.20 | 295.35 | 477.70 | 578.85 | 662.50 | 448.07 | 155.78 |

| 11 | 164.50 | 182.40 | 256.70 | 328.60 | 378.20 | 256.35 | 77.00 |

| 12 | 161.40 | 242.00 | 382.25 | 615.00 | 699.70 | 415.58 | 192.82 |

| 13 | 219.80 | 353.80 | 433.75 | 534.15 | 651.80 | 433.48 | 132.37 |

| 14 | 178.00 | 289.70 | 445.05 | 543.10 | 617.00 | 417.76 | 145.61 |

| 15 | 274.40 | 382.50 | 442.90 | 491.30 | 588.10 | 439.88 | 95.17 |

| 16 | 157.40 | 227.20 | 329.85 | 392.95 | 437.70 | 308.80 | 93.91 |

| 17 | 289.80 | 341.10 | 423.45 | 580.90 | 639.80 | 459.34 | 128.20 |

| 18 | 168.60 | 206.45 | 306.85 | 368.90 | 462.80 | 294.01 | 90.84 |

| 19 | 223.10 | 246.45 | 334.15 | 352.20 | 440.60 | 316.39 | 67.25 |

| 20 | 222.80 | 278.40 | 355.00 | 386.15 | 456.80 | 338.20 | 71.07 |

| 21 | 131.70 | 165.20 | 214.60 | 292.85 | 393.70 | 230.90 | 82.16 |

| 22 | 256.70 | 334.50 | 400.40 | 614.45 | 684.10 | 457.84 | 148.16 |

| 23 | 118.90 | 146.75 | 187.35 | 240.45 | 293.00 | 196.85 | 54.32 |

| 24 | 103.30 | 124.30 | 158.00 | 207.80 | 233.60 | 164.08 | 43.94 |

| 25 | 112.30 | 127.60 | 165.90 | 210.25 | 277.00 | 173.38 | 48.85 |

| 26 | 313.40 | 431.25 | 487.60 | 564.75 | 667.50 | 497.71 | 104.64 |

| 27 | 114.40 | 128.60 | 294.10 | 425.75 | 436.90 | 281.59 | 131.65 |

| 28 | 166.80 | 226.30 | 276.80 | 351.80 | 440.40 | 287.74 | 83.08 |

| 29 | 244.30 | 377.65 | 485.40 | 598.30 | 637.00 | 473.80 | 130.00 |

| 30 | 117.40 | 169.35 | 305.40 | 380.65 | 459.10 | 291.58 | 115.43 |

| 31 | 206.20 | 258.20 | 326.75 | 485.50 | 623.70 | 377.59 | 140.52 |

| 32 | 213.90 | 286.25 | 345.70 | 415.85 | 448.30 | 341.44 | 73.85 |

| 33 | 202.40 | 292.75 | 476.85 | 598.40 | 681.10 | 454.65 | 166.10 |

| 34 | 210.40 | 245.85 | 516.30 | 569.10 | 652.50 | 444.13 | 160.50 |

| 35 | 276.70 | 362.70 | 441.65 | 511.15 | 615.50 | 441.42 | 101.59 |

| 36 | 193.60 | 253.45 | 374.55 | 402.20 | 434.20 | 334.51 | 82.24 |

| 37 | 168.30 | 210.70 | 266.00 | 318.30 | 335.90 | 266.10 | 57.38 |

| 38 | 230.80 | 325.55 | 457.30 | 526.90 | 571.00 | 425.03 | 114.75 |

| 39 | 293.00 | 358.95 | 530.85 | 639.30 | 665.40 | 499.63 | 137.32 |

| No. EDS | Q0 | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | M | SD |

| 1 | 68.92 | 86.73 | 118.93 | 142.42 | 151.22 | 113.83 | 28.61 |

| 2 | 69.97 | 80.97 | 110.04 | 137.52 | 151.96 | 110.26 | 28.37 |

| 3 | 76.72 | 85.87 | 116.33 | 150.69 | 170.68 | 119.64 | 33.21 |

| 4 | 59.19 | 64.30 | 99.38 | 116.85 | 160.08 | 97.27 | 32.62 |

| 5 | 89.06 | 106.63 | 155.03 | 201.82 | 243.75 | 158.47 | 52.05 |

| 6 | 100.09 | 130.67 | 188.28 | 228.75 | 273.56 | 183.82 | 57.70 |

| 7 | 128.23 | 160.20 | 180.47 | 243.68 | 263.89 | 195.47 | 44.62 |

| 8 | 110.69 | 152.89 | 204.45 | 240.68 | 260.48 | 195.60 | 50.63 |

| 9 | 136.41 | 173.47 | 286.45 | 341.91 | 379.47 | 267.77 | 85.45 |

| 10 | 124.07 | 183.04 | 296.05 | 358.74 | 410.58 | 277.69 | 96.54 |

| 11 | 101.95 | 113.04 | 159.09 | 203.65 | 234.39 | 158.87 | 47.72 |

| 12 | 100.03 | 149.98 | 236.90 | 381.14 | 433.64 | 257.55 | 119.50 |

| 13 | 136.22 | 219.27 | 268.81 | 331.04 | 403.95 | 268.64 | 82.04 |

| 14 | 110.31 | 179.54 | 275.82 | 336.58 | 382.38 | 258.90 | 90.24 |

| 15 | 170.06 | 237.05 | 274.48 | 304.48 | 364.47 | 272.62 | 58.98 |

| 16 | 97.55 | 140.81 | 204.42 | 243.53 | 271.26 | 191.38 | 58.20 |

| 17 | 179.60 | 211.39 | 262.43 | 360.01 | 396.51 | 284.67 | 79.45 |

| 18 | 104.49 | 127.95 | 190.17 | 228.62 | 286.82 | 182.21 | 56.30 |

| 19 | 138.26 | 152.74 | 207.09 | 218.27 | 273.06 | 196.08 | 41.68 |

| 20 | 138.08 | 172.54 | 220.01 | 239.31 | 283.10 | 209.60 | 44.04 |

| 21 | 81.62 | 102.38 | 133.00 | 181.49 | 243.99 | 143.10 | 50.92 |

| 22 | 159.09 | 207.30 | 248.15 | 380.80 | 423.97 | 283.74 | 91.82 |

| 23 | 73.69 | 90.95 | 116.11 | 149.02 | 181.59 | 122.00 | 33.67 |

| 24 | 64.02 | 77.03 | 97.92 | 128.78 | 144.77 | 101.69 | 27.23 |

| 25 | 69.60 | 79.08 | 102.82 | 130.30 | 171.67 | 107.45 | 30.27 |

| 26 | 194.23 | 267.26 | 302.19 | 350.00 | 413.68 | 308.45 | 64.85 |

| 27 | 70.90 | 79.70 | 182.27 | 263.86 | 270.77 | 174.51 | 81.59 |

| 28 | 103.37 | 140.25 | 171.55 | 218.03 | 272.94 | 178.32 | 51.49 |

| 29 | 151.40 | 234.05 | 300.82 | 370.79 | 394.78 | 293.64 | 80.57 |

| 30 | 72.76 | 104.95 | 189.27 | 235.91 | 284.52 | 180.70 | 71.53 |

| 31 | 127.79 | 160.02 | 202.50 | 300.89 | 386.53 | 234.01 | 87.08 |

| 32 | 132.56 | 177.40 | 214.25 | 257.72 | 277.83 | 211.61 | 45.77 |

| 33 | 125.44 | 181.43 | 295.53 | 370.86 | 422.11 | 281.76 | 102.94 |

| 34 | 130.39 | 152.36 | 319.97 | 352.70 | 404.38 | 275.25 | 99.47 |

| 35 | 171.48 | 224.78 | 273.71 | 316.78 | 381.45 | 273.57 | 62.96 |

| 36 | 119.98 | 157.07 | 232.13 | 249.26 | 269.09 | 207.31 | 50.97 |

| 37 | 104.30 | 130.58 | 164.85 | 197.26 | 208.17 | 164.91 | 35.56 |

| 38 | 143.04 | 201.76 | 283.41 | 326.54 | 353.87 | 263.41 | 71.11 |

| 39 | 181.59 | 222.46 | 328.99 | 396.20 | 412.38 | 309.64 | 85.10 |

| Hour |

Pinj [MW] |

Qinj [MVAr] |

Preq [MW] |

Qreq [MVAr] |

ΔP [MW] |

ΔQ [MVAr] |

Qcap [MVAr] |

| 1 | 11.325 | 7.099 | 11.294 | 7.580 | 0.031 | 0.020 | 0.502 |

| 2 | 9.850 | 6.116 | 9.827 | 6.604 | 0.023 | 0.015 | 0.502 |

| 3 | 8.762 | 5.323 | 8.739 | 5.812 | 0.023 | 0.012 | 0.502 |

| 4 | 8.127 | 4.959 | 8.111 | 5.451 | 0.016 | 0.010 | 0.502 |

| 5 | 7.858 | 4.780 | 7.843 | 5.272 | 0.015 | 0.010 | 0.502 |

| 6 | 7.888 | 4.798 | 7.873 | 5.291 | 0.015 | 0.010 | 0.502 |

| 7 | 8.584 | 5.265 | 8.566 | 5.756 | 0.018 | 0.011 | 0.502 |

| 8 | 10.431 | 6.507 | 10.404 | 6.992 | 0.027 | 0.017 | 0.502 |

| 9 | 11.836 | 7.453 | 11.800 | 7.932 | 0.036 | 0.023 | 0.502 |

| 10 | 12.779 | 8.080 | 12.737 | 8.555 | 0.042 | 0.026 | 0.501 |

| 11 | 13.727 | 8.767 | 13.679 | 9.238 | 0.048 | 0.030 | 0.501 |

| 12 | 14.622 | 9.319 | 14.567 | 9.785 | 0.055 | 0.035 | 0.501 |

| 13 | 15.585 | 9.970 | 15.524 | 10.432 | 0.061 | 0.039 | 0.501 |

| 14 | 16.688 | 10.711 | 16.618 | 11.167 | 0.070 | 0.045 | 0.500 |

| 15 | 17.428 | 11.208 | 17.352 | 11.660 | 0.076 | 0.048 | 0.500 |

| 16 | 17.469 | 11.236 | 17.393 | 11.688 | 0.076 | 0.048 | 0.500 |

| 17 | 17.022 | 10.936 | 16.950 | 11.391 | 0.072 | 0.046 | 0.500 |

| 18 | 16.520 | 10.609 | 16.452 | 11.066 | 0.068 | 0.043 | 0.500 |

| 19 | 15.490 | 9.902 | 15.431 | 10.365 | 0.060 | 0.038 | 0.501 |

| 20 | 14.957 | 9.667 | 14.902 | 10.133 | 0.055 | 0.035 | 0.501 |

| 21 | 15.628 | 9.999 | 15.567 | 10.461 | 0.060 | 0.038 | 0.501 |

| 22 | 15.270 | 9.758 | 15.213 | 10.222 | 0.057 | 0.036 | 0.501 |

| 23 | 14.381 | 9.161 | 14.331 | 9.630 | 0.050 | 0.032 | 0.501 |

| 24 | 13.541 | 8.327 | 13.499 | 8.802 | 0.042 | 0.026 | 0.501 |

| Hour |

Pinj [MW] |

Qinj [MVAr] |

Preq [MW] |

Qreq [MVAr] |

ΔP [MW] |

ΔQ [MVAr] |

Qcap [MVAr] |

| 1 | 11.340 | 7.135 | 11.309 | 7.617 | 0.031 | 0.019 | 0.502 |

| 2 | 9.847 | 6.113 | 9.823 | 6.601 | 0.023 | 0.015 | 0.502 |

| 3 | 8.953 | 5.462 | 8.934 | 5.952 | 0.019 | 0.012 | 0.502 |

| 4 | 8.140 | 4.967 | 8.124 | 5.457 | 0.016 | 0.010 | 0.502 |

| 5 | 7.869 | 4.785 | 7.854 | 5.278 | 0.015 | 0.010 | 0.502 |

| 6 | 7.893 | 4.799 | 7.878 | 5.292 | 0.015 | 0.010 | 0.502 |

| 7 | 8.705 | 5.346 | 8.686 | 5.837 | 0.018 | 0.012 | 0.502 |

| 8 | 10.296 | 6.415 | 10.269 | 6.901 | 0.026 | 0.017 | 0.502 |

| 9 | 11.885 | 7.489 | 11.849 | 7.962 | 0.036 | 0.023 | 0.502 |

| 10 | 12.661 | 8.005 | 12.620 | 8.480 | 0.041 | 0.026 | 0.501 |

| 11 | 13.661 | 8.677 | 13.614 | 9.148 | 0.047 | 0.030 | 0.501 |

| 12 | 14.703 | 9.378 | 14.648 | 9.844 | 0.055 | 0.035 | 0.501 |

| 13 | 15.573 | 9.962 | 15.512 | 10.424 | 0.061 | 0.039 | 0.501 |

| 14 | 16.763 | 10.762 | 16.693 | 11.217 | 0.070 | 0.045 | 0.500 |

| 15 | 17.472 | 11.238 | 17.395 | 11.690 | 0.077 | 0.049 | 0.500 |

| 16 | 17.416 | 11.221 | 17.340 | 11.673 | 0.076 | 0.048 | 0.500 |

| 17 | 17.098 | 10.987 | 17.025 | 11.441 | 0.073 | 0.046 | 0.500 |

| 18 | 16.323 | 10.467 | 16.257 | 10.925 | 0.066 | 0.042 | 0.501 |

| 19 | 15.542 | 9.941 | 15.482 | 10.404 | 0.060 | 0.038 | 0.501 |

| 20 | 15.044 | 9.608 | 14.988 | 10.073 | 0.056 | 0.035 | 0.501 |

| 21 | 15.599 | 9.919 | 15.539 | 10.382 | 0.060 | 0.038 | 0.501 |

| 22 | 15.378 | 9.837 | 15.320 | 10.301 | 0.058 | 0.037 | 0.501 |

| 23 | 14.401 | 9.175 | 14.351 | 9.644 | 0.050 | 0.032 | 0.501 |

| 24 | 13.641 | 8.276 | 13.599 | 8.752 | 0.041 | 0.026 | 0.501 |

References

- Gnana Swathika, O.V.; Karthikeyan, A.; Karthikeyan, K.; Sanjeevikumar, P.; Sajju Karapparambil, T.; Babu, A. Critical review of SCADA And PLC in Smart Buildings and Energy Sector. Energy Reports, 2024, Volume 12, pp. 1518-1530. [CrossRef]

- Masri ,A; Al-Jabi, M. Toward fault tolerant modelling for SCADA based electricity distribution networks, machine learning approach. PeerJ Computer Science, 2021, Volume 7, e554. [CrossRef]

- European Commission, Distribution System Operators Observatory 2018. Overview of the electricity distribution system in Europe. 2019. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/jrc/en/publication/eur-scientific-and-technical-research-reports/distribution-system-operators-observatory-2018 (accessed on 28 December 2024).

- Meletiou, A.; Vasiljevska, J.; Prettico, G.; Vitiello, S. Distribution System Operator Observatory 2022, Publication Office of the European Union, Luxembourg, 2023. Available online: https://publications.jrc.ec.europa.eu/repository/handle/JRC132379.

- Eyisi, C.; Lotfifard, S. Load Estimation for Electric Power Distribution Networks. In Proceedings of the 46th Power Sources Conference, Orlando, Florida, USA, 9-12 June 2014.

- Xie, C.; Jia, D.; Liu, J.; Sun, X.; Zhou, J.; Research on Operation Risk Prevention and Control Technology of Intelligent Distribution Network Based on Ultra Short Term Load Forecasting. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE 1st China International Youth Conference on Electrical Engineering, Wuhan, China, 1 – 4 November 2020.

- Benato, R.; Dambone Sessa, S.; Giannuzzi, G. M.; Pisani, C.; Poli, M.; Sanniti, F. A Novel Dynamic Load Modeling for Power Systems Restoration: An Experimental Validation on Active Distribution Networks. IEEE Access, 2022, Volume 10, pp. 89861-89875. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Fadda, M. G.; Benigni, A. Decentralized Load Estimation for Distribution Systems Using Artificial Neural Networks, IEEE Transactions on Instrumentation and Measurement, 2019, Volume 68, pp. 1333-1342. [CrossRef]

- Kong, X.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, X.; Wang, C.; Chiang, H. -D.; Li, P. Adaptive Dynamic State Estimation of Distribution Network Based on Interacting Multiple Model. IEEE Transactions on Sustainable Energy, 2022, Volume 13, pp. 643-652.

- Wang, R.; Qiu, H.; Gao, H.; Li, C.; Dong Z. Y.; Liu, J. Adaptive Horizontal Federated Learning-Based Demand Response Baseline Load Estimation, IEEE Transactions on Smart Grid, 2024, Volume 15, pp. 1659-1669. [CrossRef]

- Ebrahimi, M., Rastegar, M.; Arefi, M.M. Real-Time Estimation Frameworks for Feeder-Level Load Disaggregation and PEVs’ Charging Behavior Characteristics Extraction, IEEE Transactions on Industrial Informatics, 2022, Volume 18, pp. 4715-4724.

- Zhang, Y.; Wen, H.; Wu, Q.; Ai, Q. Optimal Adaptive Prediction Intervals for Electricity Load Forecasting in Distribution Systems via Reinforcement Learning, IEEE Transactions on Smart Grid, 2023, Volume 14, pp. 3259-3270. [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.; Adnan, M.; Tariq, M; Poor, H.V. Load Forecasting Through Estimated Parametrized Based Fuzzy Inference System in Smart Grids, IEEE Transactions on Fuzzy Systems, 2021, Volume 29, pp. 156-165. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Li, G.; Huang, Y.; Jiang, J.; Bie, Z.; Li, X. Distributed Baseline Load Estimation for Load Aggregators Based on Joint FCM Clustering, IEEE Transactions on Industry Applications, 2023, Volume 59, pp. 567-577.

- Grigoras, G.; Cartina, G. The Fuzzy Correlation Approach in Operation of Electrical Distribution Systems, The International Journal for Computation and Mathematics in Electrical and Electronic Engineering, 2013, Volume 32, pp. 1044-1066.

- Rong, H. Load Estimation of Complex Power Networks from Transformer Measurements and Forecasted Loads, Complexity, 2020, 2941809. Available online: https://www.hindawi.com/journals/ complexity/2020/2941809/ . [CrossRef]

- Chemetova, S.; Santos, P.; Ventim-Neves, M. Load Forecasting in Electrical Distribution Grid of Medium Voltage, Technological Innovation for Cyber-Physical Systems, 2016, Volume 470, pp. 340 – 349.

- Ding, N.; Benoit, C.; Foggia, G.; Bésanger, Y.; Wurtz, F. Neural Network-Based Model Design for Short-Term Load Forecast in Distribution Systems, IEEE Transactions on Power Systems, 2016, Volume 31, pp. 72 -81. [CrossRef]

- Grigoras, G.; Scarlatache, F.; Cartina, G. Load Estimation for Distribution Systems Using Clustering Techniques, In Proceedings of the 13th International Conference on Optimization of Electrical and Electronic Equipment, Brasov, Romania, 24 – 26 May 2012.

- Tahyudin, I.; Firmansyah, G.; Ivansyah, A. G.; Ma'arifah, W.; Lestari, L. Comparison of K-Means Algorithms and Fuzzy C-Means Algorithms for Clustering Customers Dataset, In Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Smart Technology, Applied Informatics, and Engineering, Surakarta, Indonesia, 23 – 24 August 2022.

- Song, W.; Wang, Y.; Pan, Z.; A novel cell partition method by introducing Silhouette Coefficient for fast approximate nearest neighbor search, Information Sciences, 2023, Volume 642, 119216. [CrossRef]

- Grigoras, G.; Scarlatache, F. Processing of Smart Meters Data For Peak Load Estimation of Consumers, In Proceedings of the 9th International Symposium on Advanced Topics in Electrical Engineering, Bucharest, Romania, 9 – 7 May 2015.

- Shutaywi, M; Nezamoddin N. K. Silhouette Analysis for Performance Evaluation in Machine Learning with Applications to Clustering. Entropy, 2021, Volume 23, 759.

- Grigoras, G.; Dandea, V.; Neagu, B. -C.; Scarlatache, F. Load Estimation with the Clustering-Based Selection of the Electric Distribution Substations Integrated in SCADA System, In Proceedings of the 10th International Conference on Energy and Environment, Bucharest, Romania, 14 – 15 October 2021.

- Mirzargar, M.; Whitaker, R. T.; Kirby, R. M. Curve Boxplot: Generalization of Boxplot for Ensembles of Curve. IEEE Transactions on Visualization and Computer Graphics, 2014, Volume 20, pp. 2654-2663. [CrossRef]

- Kambale, W. V.; Deeb, A.; Bernabia, T.; Machot, F. A.; Kyamakya, K. A Boxplot Metadata Configuration Impact on Time Series Forecasting and Transfer Learning, In Proceedings of the 27th International Conference on Circuits, Systems, Communications and Computers (CSCC), Rhodes (Rodos) Island, Greece, 19 – 22 July 2023.

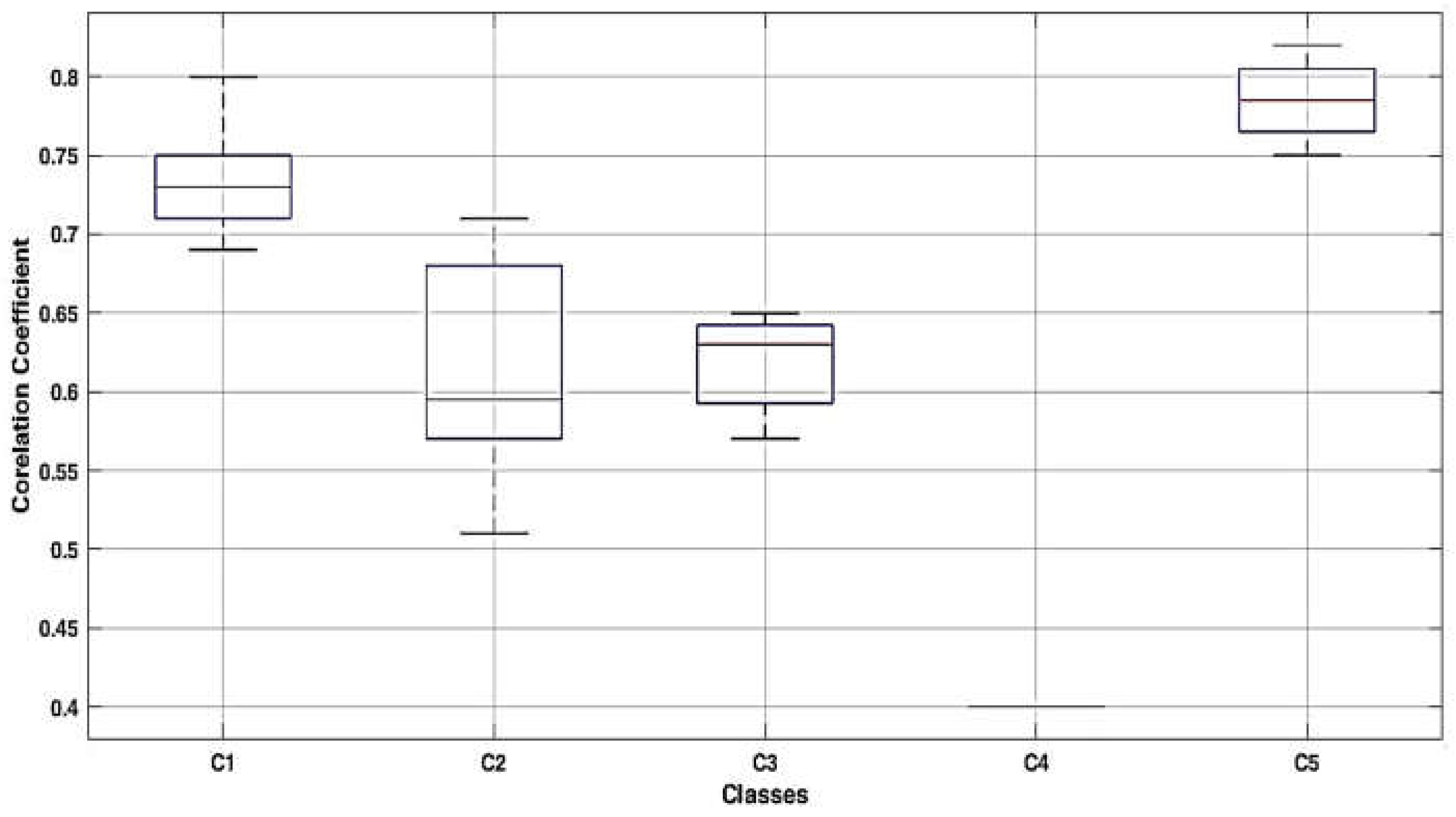

| Class | Q0 | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | M | SD |

| C1 | 0.69 | 0.71 | 0.73 | 0.75 | 0.8 | 0.74 | 0.04 |

| C2 | 0.51 | 0.57 | 0.595 | 0.68 | 0.71 | 0.62 | 0.07 |

| C3 | 0.57 | 0.59 | 0.63 | 0.64 | 0.65 | 0.62 | 0.03 |

| C4 | 0.40 | 0.40 | 0.40 | 0.40 | 0.40 | 0.40 | 0 |

| C5 | 0.75 | 0.77 | 0.79 | 0.81 | 0.82 | 0.79 | 0.02 |

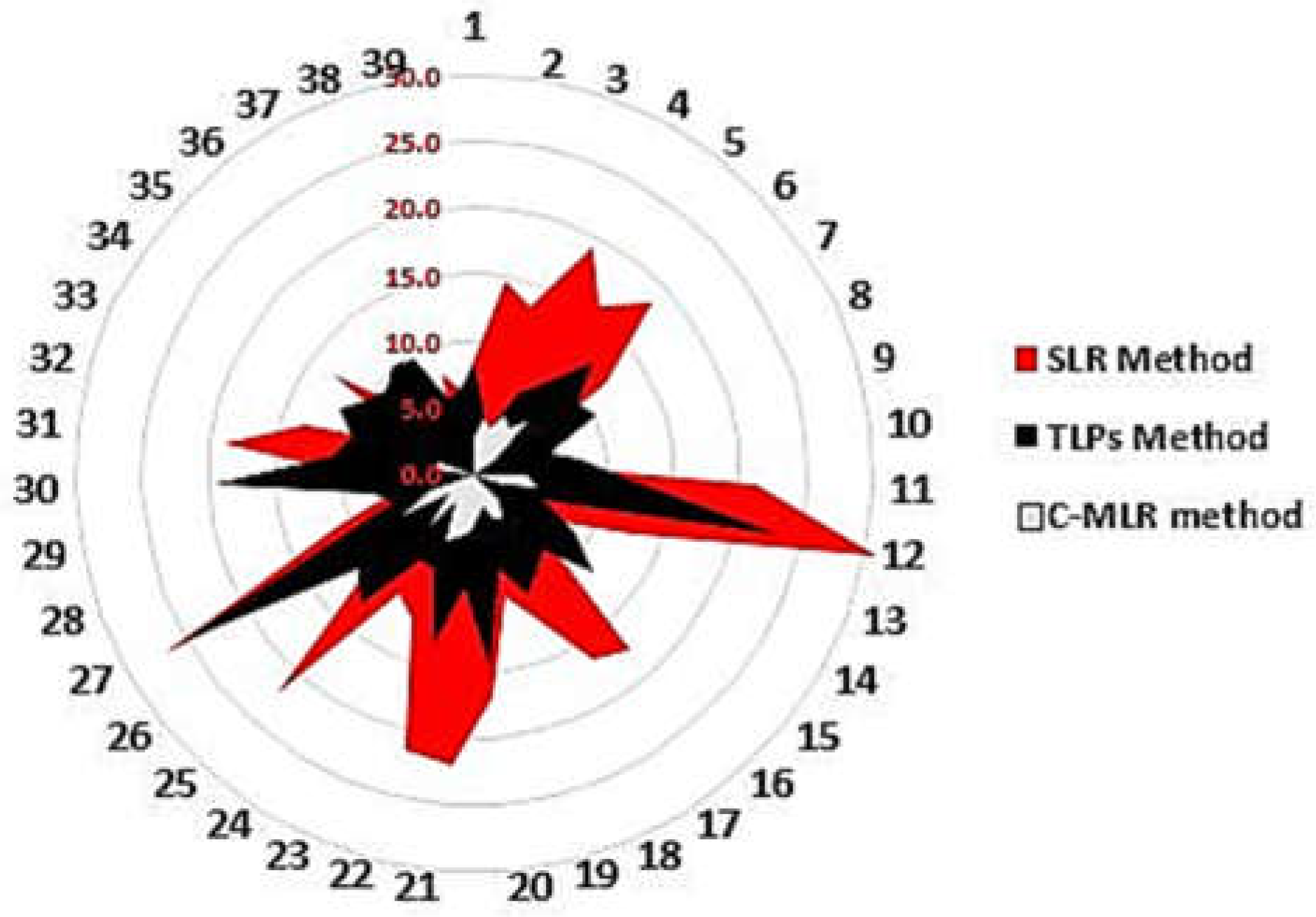

| No. EDS | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 |

| SLR Method | 8.6 | 14.7 | 13.3 | 19.4 | 15.8 | 18.5 | 12.0 | 4.2 | 6.4 | 5.2 | 21.2 | 30.9 | 12.8 | 7.3 | 5.8 | 17.8 | 16.6 | 11.8 | 9.6 | 16.9 |

| TLPs Method | 8.0 | 4.8 | 3.1 | 6.8 | 8.5 | 12.2 | 9.4 | 10.2 | 5.9 | 8.0 | 11.4 | 23.3 | 5.5 | 8.7 | 11.6 | 7.8 | 8.9 | 10.0 | 7.4 | 14.4 |

| C-MLR Method | 2.7 | 4.1 | 3.7 | 4.8 | 4.3 | 5.7 | 2.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 3.9 | 4.8 | 2.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 2.8 | 3.9 | 3.7 | 2.5 | 3.3 |

| No. EDS | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 | 31 | 32 | 33 | 34 | 35 | 36 | 37 | 38 | 39 | |

| SLR Method | 22.0 | 21.5 | 11.8 | 10.8 | 22.3 | 8.4 | 27.0 | 10.8 | 5.7 | 8.3 | 19.0 | 13.2 | 4.6 | 12.9 | 6.8 | 8.1 | 4.1 | 7.8 | 6.2 | |

| TPLs Method | 8.6 | 13.2 | 7.8 | 7.5 | 13.0 | 11.2 | 25.4 | 6.4 | 7.7 | 19.6 | 10.6 | 9.6 | 11.2 | 9.7 | 9.0 | 10.0 | 9.6 | 6.0 | 6.5 | |

| C-MLR Method | 4.3 | 5.0 | 5.4 | 2.7 | 5.2 | 2.4 | 6.3 | 3.6 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 3.3 | 2.8 | 0.0 | 4.4 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.5 | 0.0 |

| Class | Q0 | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 |

| SLR Method | 4.1 | 7.4 | 11.8 | 17.6 | 30.9 |

| TLPs Method | 3.1 | 7.6 | 9.0 | 11.2 | 25.4 |

| C-MLR Method | 0.0 | 0.00 | 2.8 | 4.2 | 6.3 |

| Hour | Pinj | Qinj | Preq | Qreq | ΔP | ΔQ | Qcap |

| 1 | 0.13 | 0.50 | 0.13 | 0.49 | 0.36 | 0.87 | 0.00 |

| 2 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.30 | 0.27 | 0.00 |

| 3 | 2.14 | 2.54 | 2.19 | 2.34 | 2.10 | 2.23 | 0.00 |

| 4 | 0.16 | 0.16 | 0.16 | 0.11 | 0.19 | 0.59 | 0.00 |

| 5 | 0.14 | 0.11 | 0.14 | 0.11 | 0.07 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| 6 | 0.07 | 0.02 | 0.06 | 0.01 | 0.20 | 0.21 | 0.09 |

| 7 | 1.39 | 1.52 | 1.38 | 1.38 | 2.85 | 2.34 | 0.05 |

| 8 | 1.31 | 1.43 | 1.31 | 1.32 | 2.24 | 2.28 | 0.02 |

| 9 | 0.42 | 0.47 | 0.42 | 0.38 | 1.13 | 1.05 | 0.09 |

| 10 | 0.93 | 0.94 | 0.93 | 0.88 | 1.51 | 1.54 | 0.07 |

| 11 | 0.48 | 1.04 | 0.48 | 0.98 | 0.91 | 0.93 | 0.03 |

| 12 | 0.55 | 0.63 | 0.56 | 0.60 | 0.49 | 0.57 | 0.02 |

| 13 | 0.08 | 0.08 | 0.08 | 0.08 | 0.37 | 0.54 | 0.06 |

| 14 | 0.45 | 0.47 | 0.45 | 0.45 | 0.06 | 0.13 | 0.09 |

| 15 | 0.25 | 0.27 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.80 | 0.80 | 0.06 |

| 16 | 0.30 | 0.14 | 0.30 | 0.13 | 0.78 | 0.77 | 0.06 |

| 17 | 0.45 | 0.46 | 0.44 | 0.44 | 1.08 | 1.04 | 0.08 |

| 18 | 1.20 | 1.36 | 1.20 | 1.29 | 2.13 | 2.17 | 0.11 |

| 19 | 0.33 | 0.39 | 0.33 | 0.37 | 0.57 | 0.61 | 0.05 |

| 20 | 0.58 | 0.61 | 0.58 | 0.59 | 0.90 | 1.19 | 0.03 |

| 21 | 0.18 | 0.80 | 0.18 | 0.77 | 0.30 | 0.34 | 0.06 |

| 22 | 0.70 | 0.80 | 0.70 | 0.76 | 1.03 | 1.09 | 0.05 |

| 23 | 0.14 | 0.15 | 0.14 | 0.14 | 0.30 | 0.28 | 0.00 |

| 24 | 0.73 | 0.61 | 0.73 | 0.58 | 1.09 | 1.15 | 0.06 |

| State variable | Q0 | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 |

| Injected active power | 0.03 | 0.15 | 0.44 | 0.72 | 2.14 |

| Injected reactive power | 0.02 | 0.16 | 0.49 | 0.87 | 2.54 |

| Requested active power | 0.04 | 0.15 | 0.43 | 0.72 | 2.19 |

| Requested active power | 0.01 | 0.14 | 0.47 | 0.83 | 2.34 |

| Active power loss | 0.06 | 0.30 | 0.79 | 1.11 | 2.85 |

| Reactive power loss | 0.00 | 0.44 | 0.84 | 1.17 | 2.34 |

| Capacitive reactive power | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.07 | 0.11 |

| Case |

WP inj [MWh] |

WQ inj [MVArh] |

WP req [MWh] |

WQ req [MVArh] |

ΔWP [MWh] |

ΔWQ [MVArh] |

WQcap [MVArh] |

| Real Data | 316.203 | 199.964 | 315.111 | 211.294 | 1.092 | 0.692 | 12.030 |

| Estimated Data | 315.766 | 199.950 | 314.670 | 211.286 | 1.096 | 0.693 | 12.028 |

| Error [%] | 0.138 | 0.007 | 0.140 | 0.004 | 0.330 | 0.032 | 0.014 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).