Submitted:

02 January 2025

Posted:

03 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Molecular Imprinted Nanoparticles (MIP-NPs)

2.3. MWCNT Dispersion

2.4. Electrospinning Solution

2.5. Electrospinning Conditions and Device Fabrication

2.6. Interdigitated Electrodes (IDEs)

2.7. UV-Crosslinking Process

2.8. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

2.9. Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM)

2.10. Transmission Electron Microscope (TEM)

2.11. Focused Ion Beam (FIB)

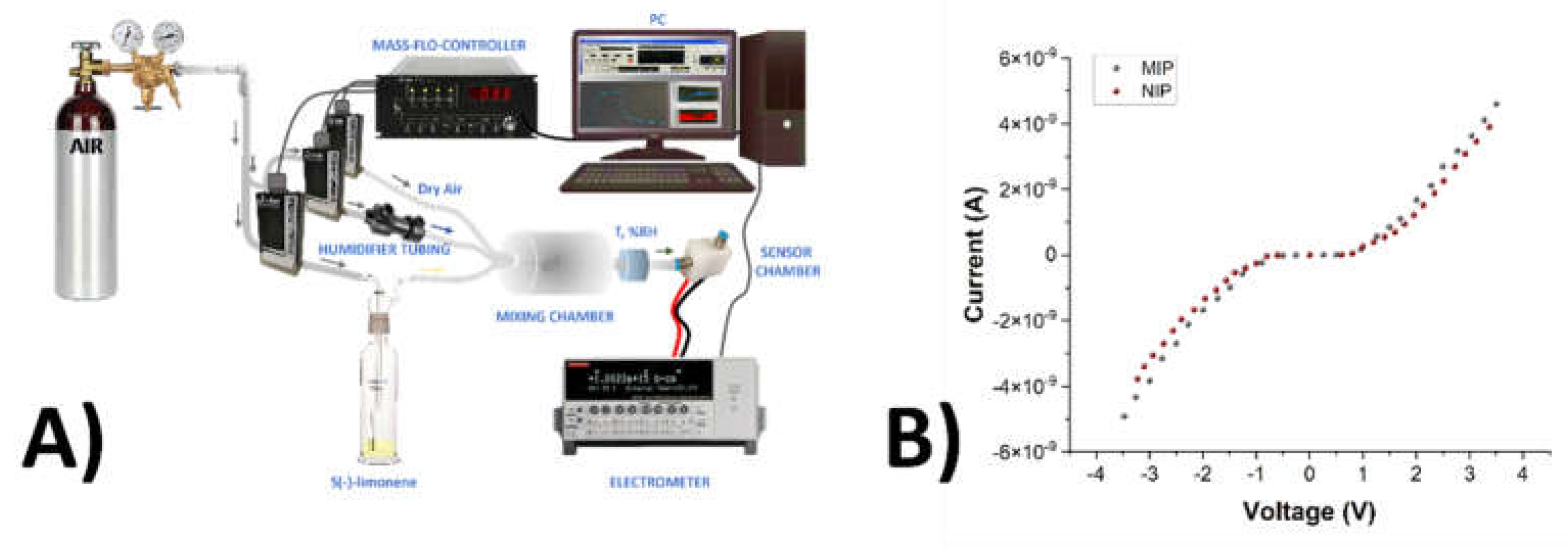

2.12. Electrical and Sensing Measurements

3. Results and Discussion

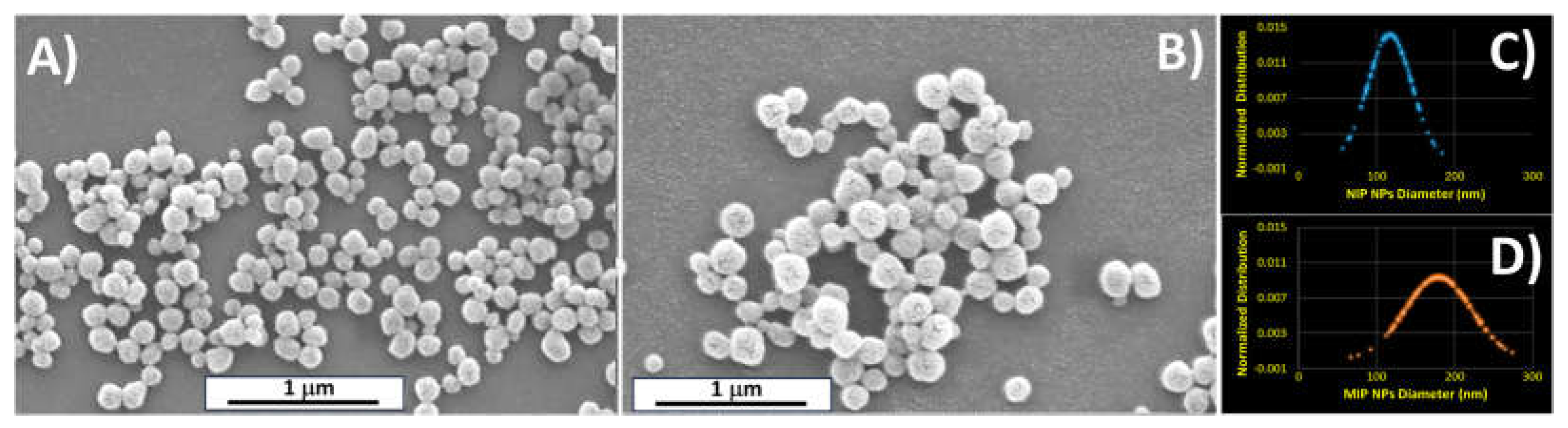

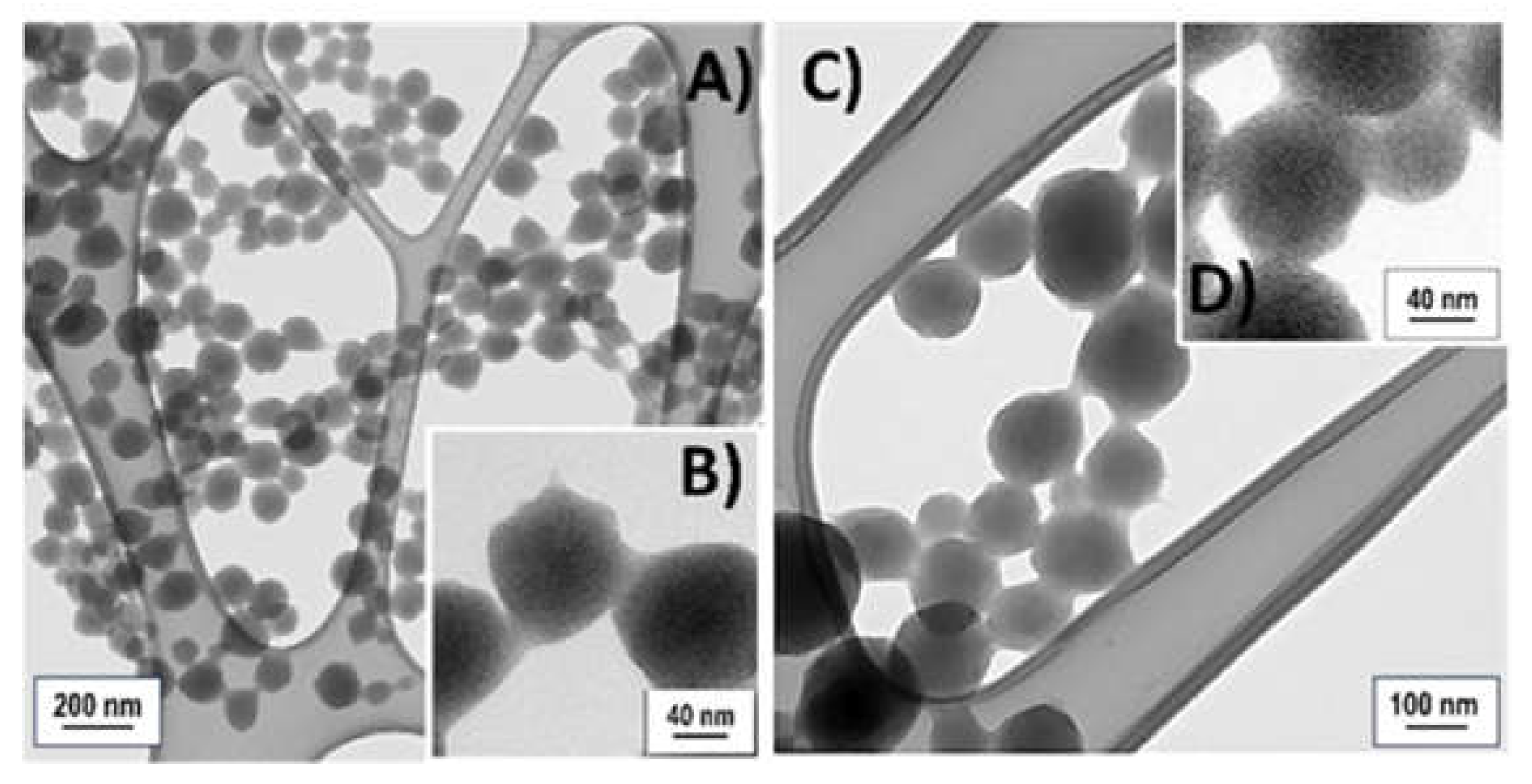

3.1. Particles Characterization

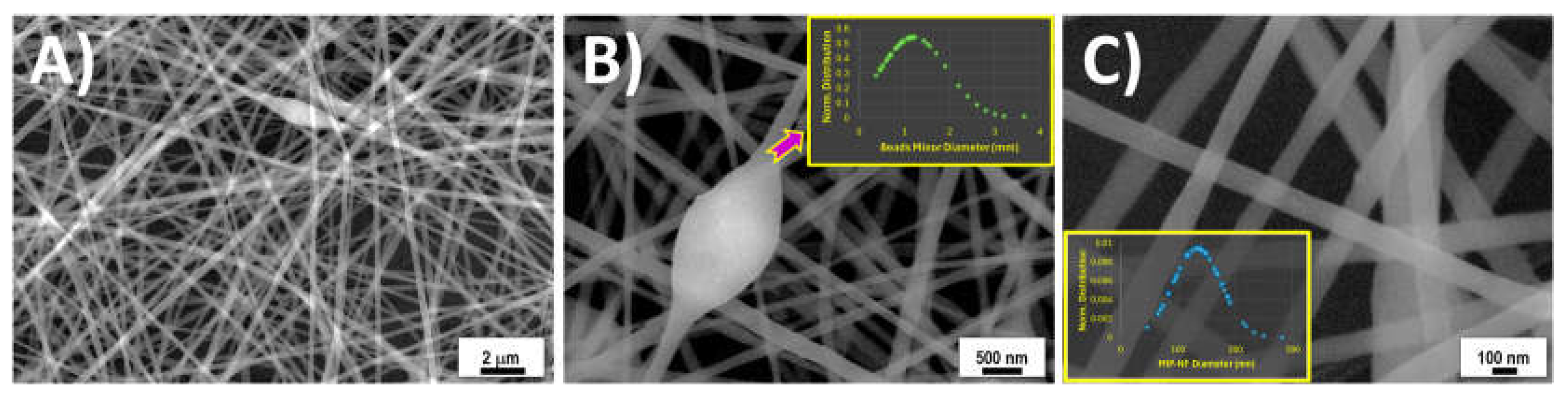

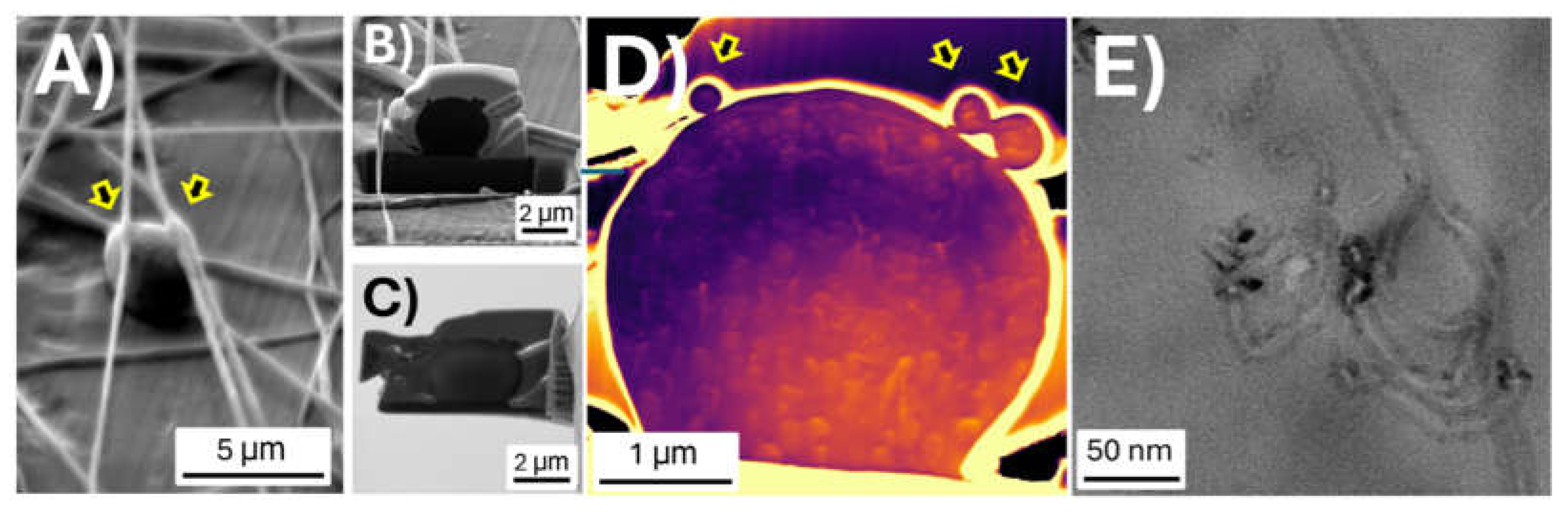

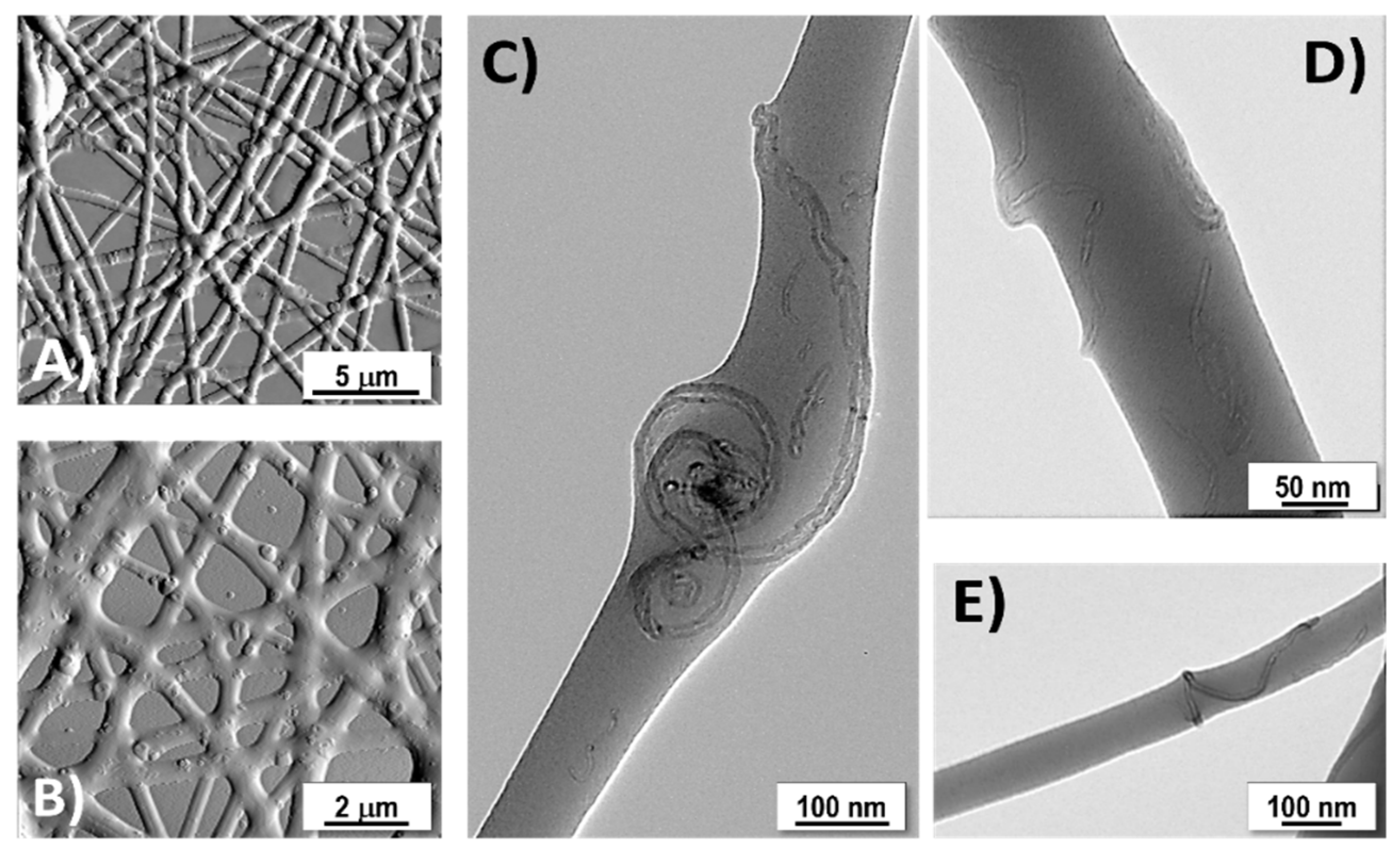

3.2. Fibre Characterization

3.3. Electrical Properties

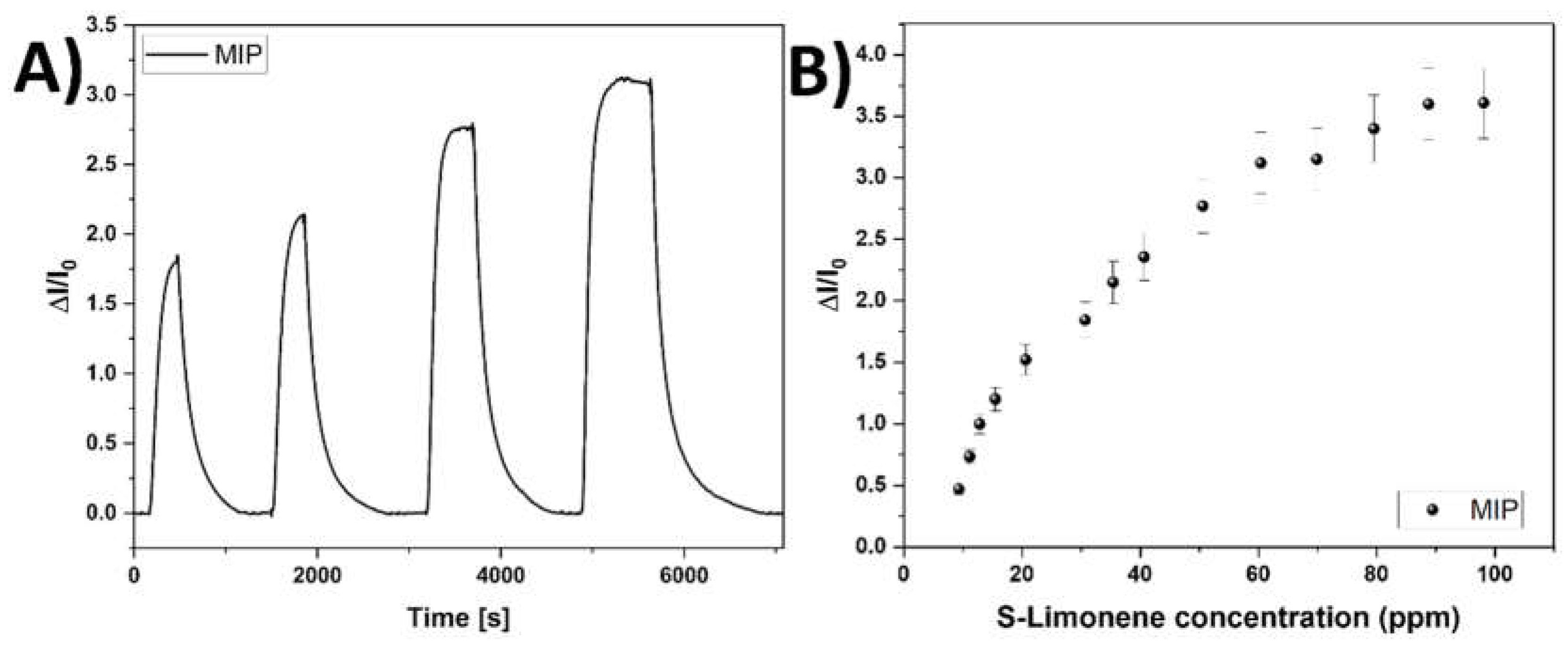

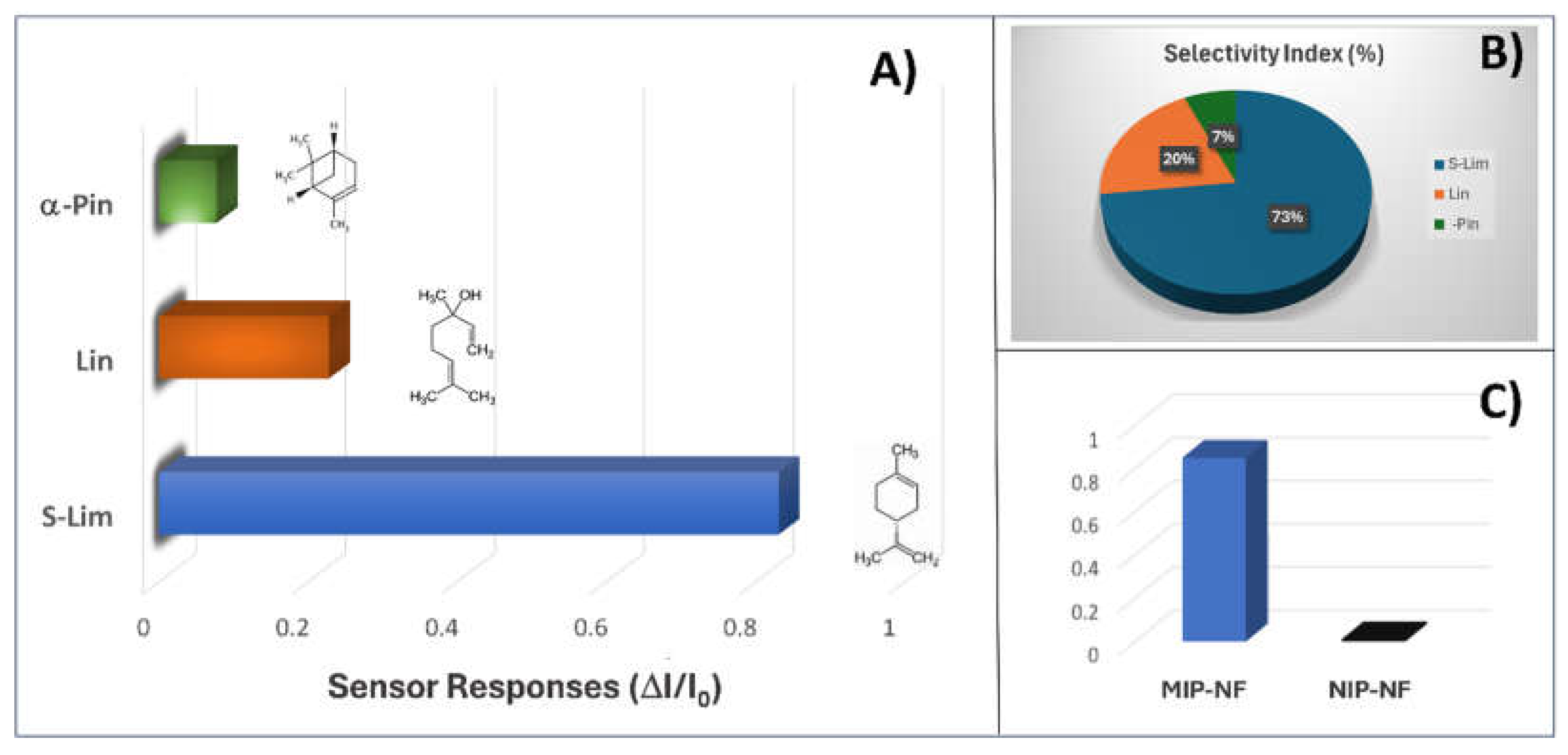

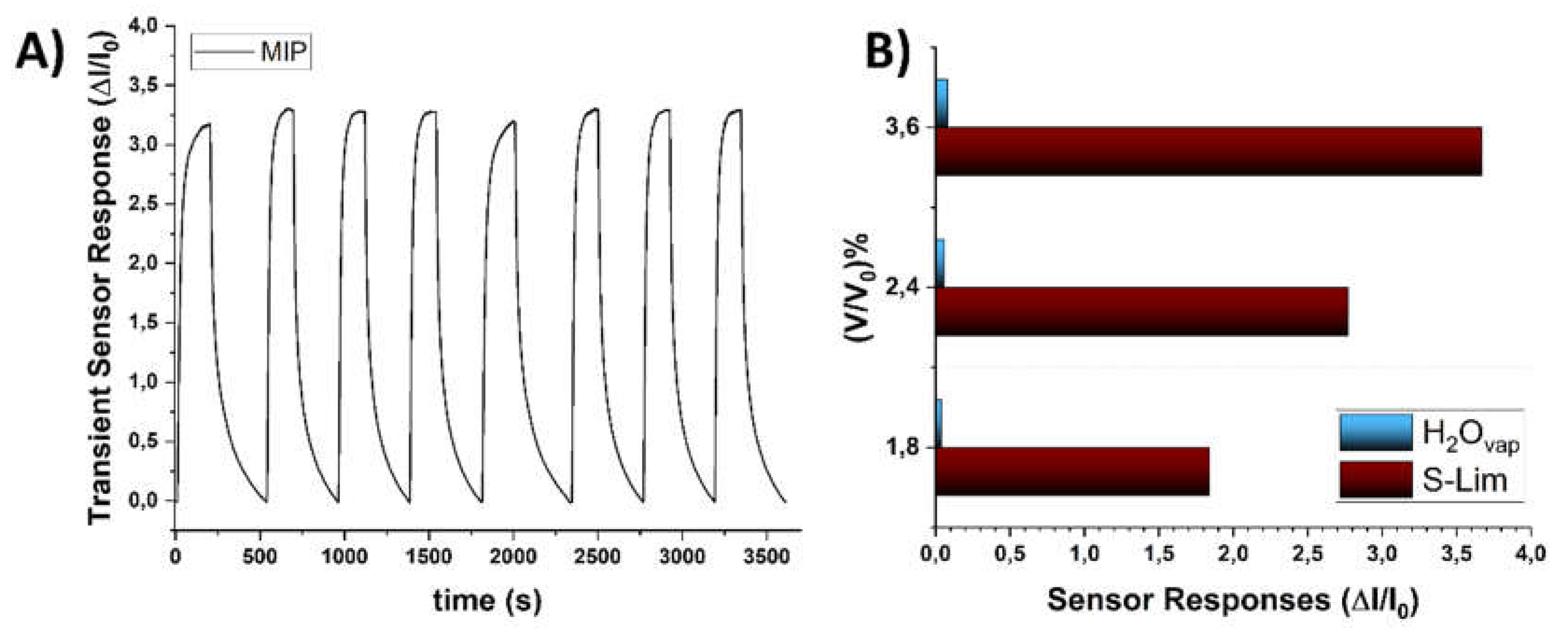

3.4. Sensor Features

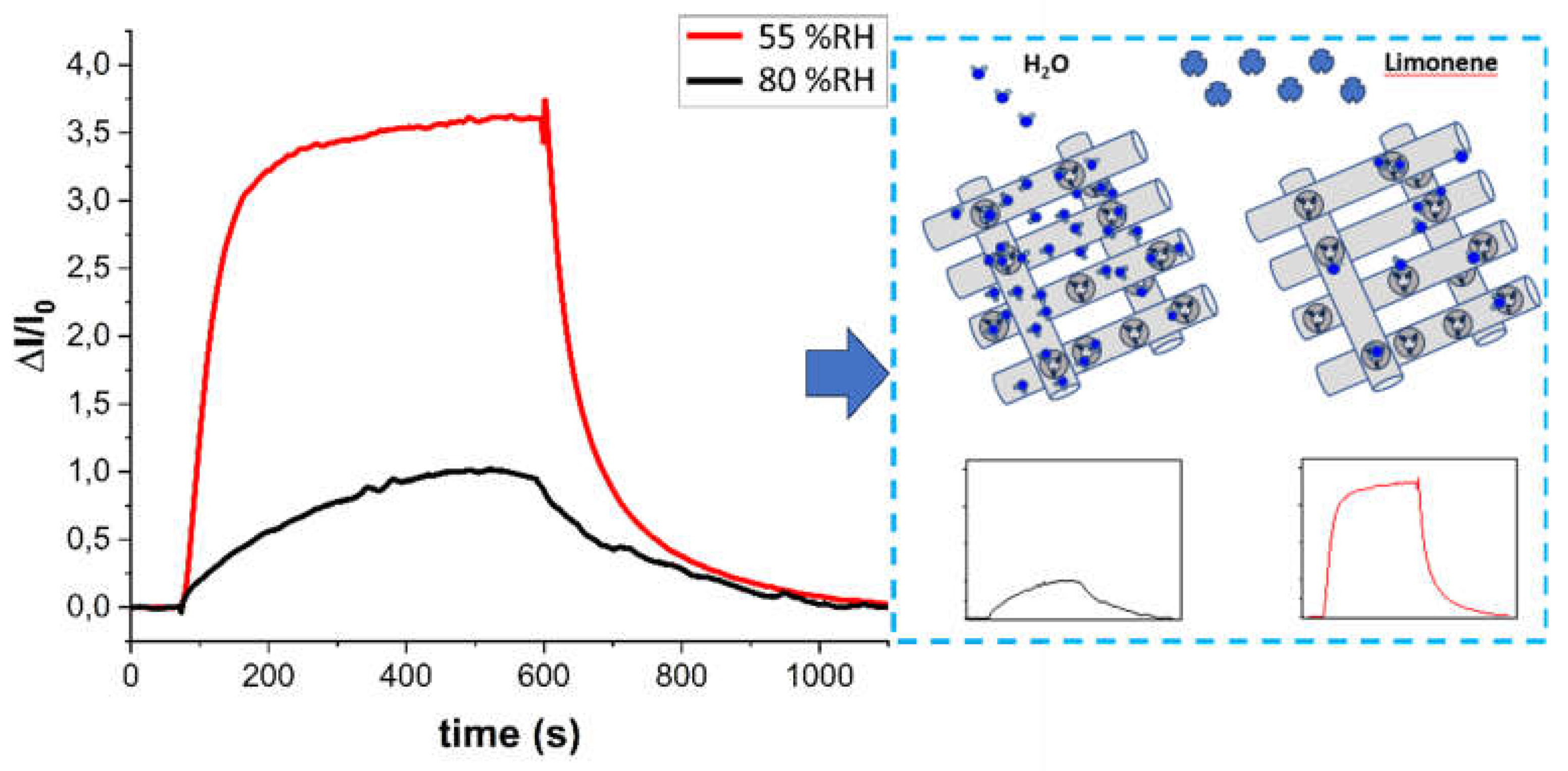

3.5. Humidity Interference

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Çakmakçı, R.; Salık, M.A.; Çakmakçı, S. Assessment and Principles of Environmentally Sustainable Food and Agriculture Systems. Agriculture 2023, 13, 1073. [CrossRef]

- Weih, M.; Hamnér, K.; Pourazari, F. Analyzing Plant Nutrient Uptake and Utilization Efficiencies: Comparison between Crops and Approaches. Plant Soil 2018, 430, 7–21. [CrossRef]

- Salim, N.; Raza, A. Nutrient Use Efficiency (NUE) for Sustainable Wheat Production: A Review. J Plant Nutr 2020, 43, 297–315. [CrossRef]

- Savary, S.; Willocquet, L.; Pethybridge, S.J.; Esker, P.; McRoberts, N.; Nelson, A. The Global Burden of Pathogens and Pests on Major Food Crops. Nat Ecol Evol 2019, 3, 430–439. [CrossRef]

- Oerke, E.-C.; Dehne, H.-W. Safeguarding Production—Losses in Major Crops and the Role of Crop Protection. Crop Protection 2004, 23, 275–285. [CrossRef]

- OERKE, E.-C. Crop Losses to Pests. J Agric Sci 2006, 144, 31–43. [CrossRef]

- Haq, I.U.; Rahim, K.; Yahya, G.; Ijaz, B.; Maryam, S.; Paker, N.P. Eco-Smart Biocontrol Strategies Utilizing Potent Microbes for Sustainable Management of Phytopathogenic Diseases. Biotechnology Reports 2024, 44, e00859. [CrossRef]

- Anaduaka, E.G.; Uchendu, N.O.; Asomadu, R.O.; Ezugwu, A.L.; Okeke, E.S.; Chidike Ezeorba, T.P. Widespread Use of Toxic Agrochemicals and Pesticides for Agricultural Products Storage in Africa and Developing Countries: Possible Panacea for Ecotoxicology and Health Implications. Heliyon 2023, 9, e15173. [CrossRef]

- Poland, J.; Rutkoski, J. Advances and Challenges in Genomic Selection for Disease Resistance. Annu Rev Phytopathol 2016, 54, 79–98. [CrossRef]

- Palmgren, M.; Shabala, S. Adapting Crops for Climate Change: Regaining Lost Abiotic Stress Tolerance in Crops. Frontiers in Science 2024, 2. [CrossRef]

- Roper, J.M.; Garcia, J.F.; Tsutsui, H. Emerging Technologies for Monitoring Plant Health in Vivo. ACS Omega 2021, 6, 5101–5107. [CrossRef]

- Oerke, E.-C. Remote Sensing of Diseases. Annu Rev Phytopathol 2024, 58, 225–252. [CrossRef]

- Fahey, T.; Pham, H.; Gardi, A.; Sabatini, R.; Stefanelli, D.; Goodwin, I.; Lamb, D.W. Active and Passive Electro-Optical Sensors for Health Assessment in Food Crops. Sensors 2020, 21, 171. [CrossRef]

- Galieni, A.; D’Ascenzo, N.; Stagnari, F.; Pagnani, G.; Xie, Q.; Pisante, M. Past and Future of Plant Stress Detection: An Overview From Remote Sensing to Positron Emission Tomography. Front Plant Sci 2021, 11. [CrossRef]

- Richard, B.; Qi, A.; Fitt, B.D.L. Control of Crop Diseases through Integrated Crop Management to Deliver Climate-smart Farming Systems for Low- and High-input Crop Production. Plant Pathol 2022, 71, 187–206. [CrossRef]

- Weiss, M.; Jacob, F.; Duveiller, G. Remote Sensing for Agricultural Applications: A Meta-Review. Remote Sens Environ 2020, 236, 111402. [CrossRef]

- Victor, N.; Maddikunta, P.K.R.; Mary, D.R.K.; Murugan, R.; Chengoden, R.; Gadekallu, T.R.; Rakesh, N.; Zhu, Y.; Paek, J. Remote Sensing for Agriculture in the Era of Industry 5.0—A Survey. IEEE J Sel Top Appl Earth Obs Remote Sens 2024, 17, 5920–5945. [CrossRef]

- Oerke, E.-C. Remote Sensing of Diseases. Annu Rev Phytopathol 2020, 58, 225–252. [CrossRef]

- Alsadik, B.; Ellsäßer, F.J.; Awawdeh, M.; Al-Rawabdeh, A.; Almahasneh, L.; Oude Elberink, S.; Abuhamoor, D.; Al Asmar, Y. Remote Sensing Technologies Using UAVs for Pest and Disease Monitoring: A Review Centered on Date Palm Trees. Remote Sens (Basel) 2024, 16, 4371. [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Huang, C.H.; Singh, G.P.; Park, B.S.; Chua, N.-H.; Ram, R.J. Portable Raman Leaf-Clip Sensor for Rapid Detection of Plant Stress. Sci Rep 2020, 10, 20206. [CrossRef]

- Gouinguené, S.P.; Turlings, T.C.J. The Effects of Abiotic Factors on Induced Volatile Emissions in Corn Plants. Plant Physiol 2002, 129, 1296–1307. [CrossRef]

- Vinicius da Silva Ferreira, M.; Barbosa, J.L.; Kamruzzaman, M.; Barbin, D.F. Low-Cost Electronic-Nose (LC-e-Nose) Systems for the Evaluation of Plantation and Fruit Crops: Recent Advances and Future Trends. Analytical Methods 2023, 15, 6120–6138. [CrossRef]

- Fundurulic, A.; Faria, J.M.S.; Inácio, M.L. Advances in Electronic Nose Sensors for Plant Disease and Pest Detection. In Proceedings of the CSAC 2023; MDPI: Basel Switzerland, September 20 2023; p. 14.

- Ali, A.; Mansol, A.S.; Khan, A.A.; Muthoosamy, K.; Siddiqui, Y. Electronic Nose as a Tool for Early Detection of Diseases and Quality Monitoring in Fresh Postharvest Produce: A Comprehensive Review. Compr Rev Food Sci Food Saf 2023, 22, 2408–2432. [CrossRef]

- Kashyap, B.; Kumar, R. Sensing Methodologies in Agriculture for Monitoring Biotic Stress in Plants Due to Pathogens and Pests. Inventions 2021, 6, 29. [CrossRef]

- Alsadik, B.; Ellsäßer, F.J.; Awawdeh, M.; Al-Rawabdeh, A.; Almahasneh, L.; Oude Elberink, S.; Abuhamoor, D.; Al Asmar, Y. Remote Sensing Technologies Using UAVs for Pest and Disease Monitoring: A Review Centered on Date Palm Trees. Remote Sens (Basel) 2024, 16, 4371. [CrossRef]

- Gold, K.M. Plant Disease Sensing: Studying Plant-Pathogen Interactions at Scale. mSystems 2021, 6. [CrossRef]

- Silva, G.; Tomlinson, J.; Onkokesung, N.; Sommer, S.; Mrisho, L.; Legg, J.; Adams, I.P.; Gutierrez-Vazquez, Y.; Howard, T.P.; Laverick, A.; et al. Plant Pest Surveillance: From Satellites to Molecules. Emerg Top Life Sci 2021, 5, 275–287. [CrossRef]

- Virnodkar, S.S.; Pachghare, V.K.; Patil, V.C.; Jha, S.K. Remote Sensing and Machine Learning for Crop Water Stress Determination in Various Crops: A Critical Review. Precis Agric 2020, 21, 1121–1155. [CrossRef]

- Perdomo, S.A.; Valencia, D.P.; Velez, G.E.; Jaramillo-Botero, A. Advancing Abiotic Stress Monitoring in Plants with a Wearable Non-Destructive Real-Time Salicylic Acid Laser-Induced-Graphene Sensor. Biosens Bioelectron 2024, 255, 116261. [CrossRef]

- Kesselmeier, J.; Staudt, M. Biogenic Volatile Organic Compounds (VOC): An Overview on Emission, Physiology and Ecology. J Atmos Chem 1999, 33, 23–88. [CrossRef]

- Guenther A, H.C.E.D.F.R.G.C.G.T.H.P.K.L.L.M.M.W.P.T.S.B.S.R.T.R.T.J., Z.P. A Global Model of Natural Volatile Organic Compound Emissions. J Geophys Res 1995, 100, 8873–8892. [CrossRef]

- Sindelarova, K.; Granier, C.; Bouarar, I.; Guenther, A.; Tilmes, S.; Stavrakou, T.; Müller, J.-F.; Kuhn, U.; Stefani, P.; Knorr, W. Global Data Set of Biogenic VOC Emissions Calculated by the MEGAN Model over the Last 30 Years. Atmos Chem Phys 2014, 14, 9317–9341. [CrossRef]

- Dudareva, N.; Negre, F.; Nagegowda, D.A.; Orlova, I. Plant Volatiles: Recent Advances and Future Perspectives. CRC Crit Rev Plant Sci 2006, 25, 417–440. [CrossRef]

- Maffei, M.E. Sites of Synthesis, Biochemistry and Functional Role of Plant Volatiles. South African Journal of Botany 2010, 76, 612–631. [CrossRef]

- Eirini, S.; Paschalina, C.; Ioannis, T.; Kortessa, D.-T. Effect of Drought and Salinity on Volatile Organic Compounds and Other Secondary Metabolites of Citrus Aurantium Leaves. In Proceedings of the NATURAL PRODUCT COMMUNICATIONS; SAGE PUBLICATIONS INC: 2455 TELLER RD, THOUSAND OAKS, CA 91320, April 5 2017; pp. 193–196. [CrossRef]

- Bracho-Nunez, A.; Welter, S.; Staudt, M.; Kesselmeier, J. Plant-Specific Volatile Organic Compound Emission Rates from Young and Mature Leaves of Mediterranean Vegetation. J Geophys Res 2011, 116, D16304. [CrossRef]

- Brillante, L.; Martínez-Lüscher, J.; Kurtural, S.K. Applied Water and Mechanical Canopy Management Affect Berry and Wine Phenolic and Aroma Composition of Grapevine ( Vitis Vinifera L., Cv. Syrah) in Central California. Sci Hortic 2018, 227, 261–271. [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Tang, J.; Yu, X. Environmental and Physiological Controls on Diurnal and Seasonal Patterns of Biogenic Volatile Organic Compound Emissions from Five Dominant Woody Species under Field Conditions. Environmental Pollution 2020, 259, 113955. [CrossRef]

- Toffolatti, S.L.; Maddalena, G.; Passera, A.; Casati, P.; Bianco, P.A.; Quaglino, F. Role of Terpenes in Plant Defense to Biotic Stress. In Biocontrol Agents and Secondary Metabolites; Elsevier, 2021; pp. 401–417. [CrossRef]

- Boncan, D.A.T.; Tsang, S.S.K.; Li, C.; Lee, I.H.T.; Lam, H.-M.; Chan, T.-F.; Hui, J.H.L. Terpenes and Terpenoids in Plants: Interactions with Environment and Insects. Int J Mol Sci 2020, 21, 7382. [CrossRef]

- Loreto, F.; Schnitzler, J.-P. Abiotic Stresses and Induced BVOCs. Trends Plant Sci 2010, 15, 154–166. [CrossRef]

- Kovalenko, Y.; Tindjau, R.; Madilao, L.L.; Castellarin, S.D. Regulated Deficit Irrigation Strategies Affect the Terpene Accumulation in Gewürztraminer (Vitis Vinifera L.) Grapes Grown in the Okanagan Valley. Food Chem 2021, 341, 128172. [CrossRef]

- Castorina, G.; Grassi, F.; Consonni, G.; Vitalini, S.; Oberti, R.; Calcante, A.; Ferrari, E.; Bononi, M.; Iriti, M. Characterization of the Biogenic Volatile Organic Compounds (BVOCs) and Analysis of the PR1 Molecular Marker in Vitis Vinifera L. Inoculated with the Nematode Xiphinema Index. Int J Mol Sci 2020, 21, 4485. [CrossRef]

- Malheiro, R.; Casal, S.; Cunha, S.C.; Baptista, P.; Pereira, J.A. Identification of Leaf Volatiles from Olive (Olea Europaea) and Their Possible Role in the Ovipositional Preferences of Olive Fly, Bactrocera Oleae (Rossi) (Diptera: Tephritidae). Phytochemistry 2016, 121, 11–19. [CrossRef]

- Ninkuu, V.; Zhang, L.; Yan, J.; Fu, Z.; Yang, T.; Zeng, H. Biochemistry of Terpenes and Recent Advances in Plant Protection. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22, 5710. [CrossRef]

- Aina, O.; Bakare, O.O.; Fadaka, A.O.; Keyster, M.; Klein, A. Plant Biomarkers as Early Detection Tools in Stress Management in Food Crops: A Review. Planta 2024, 259, 60. [CrossRef]

- Notario, A.; Sánchez, R.; Luaces, P.; Sanz, C.; Pérez, A.G. The Infestation of Olive Fruits by Bactrocera Oleae (Rossi) Modifies the Expression of Key Genes in the Biosynthesis of Volatile and Phenolic Compounds and Alters the Composition of Virgin Olive Oil. Molecules 2022, 27, 1650. [CrossRef]

- Herrera-Chacón, A.; Cetó, X.; del Valle, M. Molecularly Imprinted Polymers - towards Electrochemical Sensors and Electronic Tongues. Anal Bioanal Chem 2021, 413, 6117–6140. [CrossRef]

- Cieplak, M.; Kutner, W. Artificial Biosensors: How Can Molecular Imprinting Mimic Biorecognition? Trends Biotechnol 2016, 34, 922–941. [CrossRef]

- Malitesta, C.; Mazzotta, E.; Picca, R.A.; Poma, A.; Chianella, I.; Piletsky, S.A. MIP Sensors – the Electrochemical Approach. Anal Bioanal Chem 2012, 402, 1827–1846. [CrossRef]

- Wasilewski, T.; Orbay, S.; Brito, N.F.; Sikora, K.; Melo, A.C.A.; Melendez, M.E.; Szulczyński, B.; Sanyal, A.; Kamysz, W.; Gębicki, J. Molecularly Imprinted Polymers for the Detection of Volatile Biomarkers. TrAC Trends in Analytical Chemistry 2024, 177, 117783. [CrossRef]

- Hua, Y.; Ahmadi, Y.; Kim, K.-H. Molecularly Imprinted Polymers for Sensing Gaseous Volatile Organic Compounds: Opportunities and Challenges. Environmental Pollution 2022, 311, 119931. [CrossRef]

- Kim, W.; Noh, B.-I.; Cha, Y.L.; Chang, Y.-H.; Dai, S.; Kim, S.H.; Kim, D.-J. Development of Molecularly Imprinted Polymer Electrochemical Sensors for Strawberry Sweetness Biomarker Detection. ACS Appl Polym Mater 2024, 6, 8084–8092. [CrossRef]

- Antwi-Boampong, S.; Mani, K.S.; Carlan, J.; BelBruno, J.J. A Selective Molecularly Imprinted Polymer-Carbon Nanotube Sensor for Cotinine Sensing. Journal of Molecular Recognition 2014, 27, 57–63. [CrossRef]

- Tang, X.; Raskin, J.-P.; Lahem, D.; Krumpmann, A.; Decroly, A.; Debliquy, M. A Formaldehyde Sensor Based on Molecularly-Imprinted Polymer on a TiO2 Nanotube Array. Sensors 2017, 17, 675. [CrossRef]

- Koudehi, M.F.; Pourmortazavi, S.M.; Zibaseresht, R.; Mirsadeghi, S. << MEMS-Based PVA/PPy/MIP Polymeric- Nanofiber Sensor Fabricated by LIFT-OFF Process for Detection 2,4-Dinitrotoluene Vapor. IEEE Sens J 2021, 21, 9492–9499. [CrossRef]

- Alizadeh, T.; Rezaloo, F. Toluene Chemiresistor Sensor Based on Nano-Porous Toluene-Imprinted Polymer. Int J Environ Anal Chem 2013, 93, 919–934. [CrossRef]

- Alizadeh, T.; Rezaloo, F. A New Chemiresistor Sensor Based on a Blend of Carbon Nanotube, Nano-Sized Molecularly Imprinted Polymer and Poly Methyl Methacrylate for the Selective and Sensitive Determination of Ethanol Vapor. Sens Actuators B Chem 2013, 176, 28–37. [CrossRef]

- Dong, X.; Zhang, C.; Du, X.; Zhang, Z. Recent Advances of Nanomaterials-Based Molecularly Imprinted Electrochemical Sensors. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 1913. [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Cruz, A.; Ahmad, O.S.; Alanazi, K.; Piletska, E.; Piletsky, S.A. Generic Sensor Platform Based on Electro-Responsive Molecularly Imprinted Polymer Nanoparticles (e-NanoMIPs). Microsyst Nanoeng 2020, 6, 83. [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Pagett, M.; Zhang, W. Molecularly Imprinted Polymer (MIP) Based Electrochemical Sensors and Their Recent Advances in Health Applications. Sensors and Actuators Reports 2023, 5, 100153. [CrossRef]

- Rahman, S.; Bozal-Palabiyik, B.; Unal, D.N.; Erkmen, C.; Siddiq, M.; Shah, A.; Uslu, B. Molecularly Imprinted Polymers (MIPs) Combined with Nanomaterials as Electrochemical Sensing Applications for Environmental Pollutants. Trends in Environmental Analytical Chemistry 2022, 36, e00176. [CrossRef]

- Kikuchi, M.; Tsuru, N.; Shiratori, S. Recognition of Terpenes Using Molecular Imprinted Polymer Coated Quartz Crystal Microbalance in Air Phase. Sci Technol Adv Mater 2006, 7, 156–161. [CrossRef]

- Ghatak, B.; Ali, S.B.; Naskar, H.; Tudu, B.; Pramanik, P.; Mukherji, S.; Bandyopadhyay, R. Selective and Sensitive Detection of Limonene in Mango Using Molecularly Imprinted Polymer Based Quartz Crystal Microbalance Sensor. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE International Symposium on Olfaction and Electronic Nose (ISOEN); IEEE, May 2019; pp. 1–3. [CrossRef]

- Hawari, H.F.; Samsudin, N.M.; Ahmad, M.N.; Shakaff, A.Y.M.; Ghani, S.A.; Wahab, Y.; Za’aba, S.K.; Akitsu, T. Array of MIP-Based Sensor for Fruit Maturity Assessment. Procedia Chem 2012, 6, 100–109. [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, N.; Mustafa, G.; Rehman, A.; Biedermann, A.; Najafi, B.; Lieberzeit, P.A.; Dickert, F.L. QCM-Arrays for Sensing Terpenes in Fresh and Dried Herbs via Bio-Mimetic MIP Layers. Sensors 2010, 10, 6361–6376. [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Yazdani, M.; Murugappan, K. Non-Destructive Pest Detection: Innovations and Challenges in Sensing Airborne Semiochemicals. ACS Sens 2024, 9, 5728–5747. [CrossRef]

- Wen, T.; Nie, Q.; Han, L.; Gong, Z.; Li, D.; Ma, Q.; Wang, Z.; He, W.; Wen, L.; Peng, H. Molecularly Imprinted Polymers-Based Piezoelectric Coupling Sensor for the Rapid and Nondestructive Detection of Infested Citrus. Food Chem 2022, 387, 132905. [CrossRef]

- Hawari, H.F.; Samsudin, N.M.; Md Shakaff, A.Y.; Ghani, Supri.A.; Ahmad, M.N.; Wahab, Y.; Hashim, U. Development of Interdigitated Electrode Molecular Imprinted Polymer Sensor for Monitoring Alpha Pinene Emissions from Mango Fruit. Procedia Eng 2013, 53, 197–202. [CrossRef]

- Völkle, J.; Kumpf, K.; Feldner, A.; Lieberzeit, P.; Fruhmann, P. Development of Conductive Molecularly Imprinted Polymers (CMIPs) for Limonene to Improve and Interconnect QCM and Chemiresistor Sensing. Sens Actuators B Chem 2022, 356, 131293. [CrossRef]

- Olsen, B.G.; Stradiotto, N.R. Enantioselective Detection of (D)- and (L)-Limonene from Essential Oil Samples Using a Molecularly Imprinted Polypyrrole Electrochemical Sensor. ECS Meeting Abstracts 2024, MA2024-01, 2667–2667. [CrossRef]

- Fresco-Cala, B.; Batista, A.D.; Cárdenas, S. Molecularly Imprinted Polymer Micro- and Nano-Particles: A Review. Molecules 2020, 25, 4740. [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Wang, X.; Lu, W.; Wu, X.; Li, J. Molecular Imprinting: Perspectives and Applications. Chem Soc Rev 2016, 45, 2137–2211. [CrossRef]

- Macagnano, A.; Perri, V.; Zampetti, E.; Bearzotti, A.; De Cesare, F. Humidity Effects on a Novel Eco-Friendly Chemosensor Based on Electrospun PANi/PHB Nanofibres. Sens Actuators B Chem 2016, 232, 16–27. [CrossRef]

- Borah, A.R.; Hazarika, P.; Duarah, R.; Goswami, R.; Hazarika, S. Biodegradable Electrospun Membranes for Sustainable Industrial Applications. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 11129–11147. [CrossRef]

- Soares, R.M.D.; Siqueira, N.M.; Prabhakaram, M.P.; Ramakrishna, S. Electrospinning and Electrospray of Bio-Based and Natural Polymers for Biomaterials Development. Materials Science and Engineering: C 2018, 92, 969–982. [CrossRef]

- Keshvardoostchokami, M.; Majidi, S.S.; Huo, P.; Ramachandran, R.; Chen, M.; Liu, B. Electrospun Nanofibers of Natural and Synthetic Polymers as Artificial Extracellular Matrix for Tissue Engineering. Nanomaterials 2020, 11, 21. [CrossRef]

- Electrospinning for High Performance Sensors; Macagnano, A., Zampetti, E., Kny, E., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2015; ISBN 978-3-319-14405-4. [CrossRef]

- Papa, P.; Zampetti, E.; Molinari, F.N.; De Cesare, F.; Di Natale, C.; Tranfo, G.; Macagnano, A. A Polyvinylpyrrolidone Nanofibrous Sensor Doubly Decorated with Mesoporous Graphene to Selectively Detect Acetic Acid Vapors. Sensors 2024, 24, 2174. [CrossRef]

- Vanaraj, R.; Arumugam, B.; Mayakrishnan, G.; Kim, I.S.; Kim, S.C. A Review on Electrospun Nanofiber Composites for an Efficient Electrochemical Sensor Applications. Sensors 2023, 23, 6705. [CrossRef]

- Macagnano, A.; Avossa, J. Nanostructured Composite Materials for Advanced Chemical Sensors. In Advances in Nanostructured Materials and Nanopatterning Technologies; Elsevier, 2020; pp. 297–332. [CrossRef]

- Avossa, J.; Zampetti, E.; De Cesare, F.; Bearzotti, A.; Scarascia-Mugnozza, G.; Vitiello, G.; Zussman, E.; Macagnano, A. Thermally Driven Selective Nanocomposite PS-PHB/MGC Nanofibrous Conductive Sensor for Air Pollutant Detection. Front Chem 2018, 6. [CrossRef]

- Patel, K.D.; Kim, H.; Knowles, J.C.; Poma, A. Molecularly Imprinted Polymers and Electrospinning: Manufacturing Convergence for Next-Level Applications. Adv Funct Mater 2020, 30. [CrossRef]

- Dong, H.; Tong, L.; Cheng, M.; Hou, S. Utilizing Electrospun Molecularly Imprinted Membranes for Food Industry: Opportunities and Challenges. Food Chem 2024, 460, 140695. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Dai, Y.; Rong, J.; Zhang, T.; Xue, S.; Yang, D.; Pan, J.; Qiu, F. “Sandwich-like” Electrospinning Fiber-Based Molecularly Imprinted Membrane Constructed with Electrospun Polyethyleneimine as the Multifunction Interlayer for the Selective Separation of Shikimic Acid. Chemical Engineering Journal 2023, 463, 142501. [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Liu, H.; Lei, X.; Zhai, Y. Electrospun Nanofiber Membranes Containing Molecularly Imprinted Polymer (MIP) for Rhodamine B (RhB). Advances in Chemical Engineering and Science 2012, 02, 266–274. [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi, V.; Saraji, M.; Jafari, M.T. Direct Molecular Imprinting Technique to Synthesize Coated Electrospun Nanofibers for Selective Solid-Phase Microextraction of Chlorpyrifos. Microchimica Acta 2019, 186, 524. [CrossRef]

- Moraes Segundo, J. de D.P. de; Moraes, M.O.S. de; Brito, W.R.; Matos, R.S.; Salerno, M.; Barcelay, Y.R.; Segala, K.; Fonseca Filho, H.D. da; d’Ávila, M.A. Molecularly Imprinted Membrane Produced by Electrospinning for β-Caryophyllene Extraction. Materials 2022, 15, 7275. [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Wang, Y.; Liu, H.; He, R.; Zhao, X.; Wang, Y.; Qin, W.; Yin, S. Molecularly Imprinted Sensors Based on Highly Stretchable Electrospun Membranes for Cortisol Detection. Microchemical Journal 2024, 207, 112115. [CrossRef]

- Zahedi, P.; Fallah-Darrehchi, M.; Nadoushan, S.A.; Aeinehvand, R.; Bagheri, L.; Najafi, M. Morphological, Thermal and Drug Release Studies of Poly (Methacrylic Acid)-Based Molecularly Imprinted Polymer Nanoparticles Immobilized in Electrospun Poly (ε-Caprolactone) Nanofibers as Dexamethasone Delivery System. Korean Journal of Chemical Engineering 2017, 34, 2110–2118. [CrossRef]

- Demirkurt, M.; Olcer, Y.A.; Demir, M.M.; Eroglu, A.E. Electrospun Polystyrene Fibers Knitted around Imprinted Acrylate Microspheres as Sorbent for Paraben Derivatives. Anal Chim Acta 2018, 1014, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Hassanzadeh, M.; Ghaemy, M.; Amininasab, S.M.; Shami, Z. An Effective Approach for Fast Selective Separation of Cr(VI) from Water by Ion-Imprinted Polymer Grafted on the Electro-Spun Nanofibrous Mat of Functionalized Polyacrylonitrile. React Funct Polym 2018, 130, 70–80. [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, M.; Liu, F.; Wan, Y.; Huang, Z.; Ye, L.; Zhou, Q.; Shi, Y.; Lu, B. Selective and Simultaneous Determination of Trace Bisphenol A and Tebuconazole in Vegetable and Juice Samples by Membrane-Based Molecularly Imprinted Solid-Phase Extraction and HPLC. Food Chem 2014, 164, 527–535. [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Liu, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Wan, Y.; Gao, K.; Huang, Y.; Xia, W.; Wang, H.; Shi, Y.; et al. Molecularly Imprinted Nanofiber Membranes Enhanced Biodegradation of Trace Bisphenol A by Pseudomonas Aeruginosa. Chemical Engineering Journal 2015, 262, 989–998. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Guo, Y.; Chi, W.; Shi, H.; Ren, H.; Guo, T. Electrospun Nanofibers Containing P-Nitrophenol Imprinted Nanoparticles for the Hydrolysis of Paraoxon. Chinese Journal of Polymer Science 2014, 32, 1469–1478. [CrossRef]

- Yoshimatsu, K.; Ye, L.; Lindberg, J.; Chronakis, I.S. Selective Molecular Adsorption Using Electrospun Nanofiber Affinity Membranes. Biosens Bioelectron 2008, 23, 1208–1215. [CrossRef]

- Yoshimatsu, K.; Ye, L.; Stenlund, P.; Chronakis, I.S. A Simple Method for Preparation of Molecularly Imprinted Nanofiber Materials with Signal Transduction Ability. Chemical Communications 2008, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Piperno, S.; Tse Sum Bui, B.; Haupt, K.; Gheber, L.A. Immobilization of Molecularly Imprinted Polymer Nanoparticles in Electrospun Poly(Vinyl Alcohol) Nanofibers. Langmuir 2011, 27, 1547–1550. [CrossRef]

- Molinari, F.N.; De Cesare, F.; Macagnano, A. Housing Molecularly Imprinted Polymer Nanoparticles in Polyvinylpyrrolidone/Multiwall Carbon Nanotube Nanofibers to Detect Chiral Terpene Vapors. In Proceedings of the Eurosensors 2023; MDPI: Basel Switzerland, March 26 2024; p. 96. [CrossRef]

- Macagnano, A.; Molinari, F.N.; Papa, P.; Mancini, T.; Lupi, S.; D’Arco, A.; Taddei, A.R.; Serrecchia, S.; De Cesare, F. Nanofibrous Conductive Sensor for Limonene: One-Step Synthesis via Electrospinning and Molecular Imprinting. Nanomaterials 2024, 14, 1123. [CrossRef]

- Pratama, K.F.; Manik, M.E.R.; Rahayu, D.; Hasanah, A.N. Effect of the Molecularly Imprinted Polymer Component Ratio on Analytical Performance. Chem Pharm Bull (Tokyo) 2020, 68, 1013–1024. [CrossRef]

- Molinari, F.; Medrano, A. V.; Bacigalupe, A.; Escobar, M.M.; Monsalve, L.N. Different Dispersion States of MWCNT in Aligned Conductive Electrospun PCL/MWCNT Composites. Fullerenes, Nanotubes and Carbon Nanostructures 2018, 26, 667–674. [CrossRef]

- Ricca, M.; Foderà, V.; Giacomazza, D.; Leone, M.; Spadaro, G.; Dispenza, C. Probing the Internal Environment of PVP Networks Generated by Irradiation with Different Sources. Colloid Polym Sci 2010, 288, 969–980. [CrossRef]

- Biran, I.; Houben, L.; Kossoy, A.; Rybtchinski, B. Transmission Electron Microscopy Methodology to Analyze Polymer Structure with Submolecular Resolution. The Journal of Physical Chemistry C 2024, 128, 5988–5995. [CrossRef]

- Martin, H.J.; White, B.T.; Wang, H.; Mays, J.; Saito, T.; Dadmun, M.D. Effect of Solvent Quality and Monomer Water Solubility on Soft Nanoparticle Morphology. In; 2018; pp. 117–137. [CrossRef]

- Mueller, A. A Note about Crosslinking Density in Imprinting Polymerization. Molecules 2021, 26, 5139. [CrossRef]

- Golker, K.; Nicholls, I.A. The Effect of Crosslinking Density on Molecularly Imprinted Polymer Morphology and Recognition. Eur Polym J 2016, 75, 423–430. [CrossRef]

- Patel, B.; Pearson, R.; Watanabe, M. Bright Field and Dark Field STEM-IN-SEM Imaging of Polymer Systems. J Appl Polym Sci 2014, 131. [CrossRef]

- Raymo, F. Nanomaterials Synthesis and Applications: Molecule-Based Devices. In Springer Handbook of Nanotechnology; Springer Berlin Heidelberg: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2007; pp. 13–42. [CrossRef]

- Salalha, W.; Dror, Y.; Khalfin, R.L.; Cohen, Y.; Yarin, A.L.; Zussman, E. Single-Walled Carbon Nanotubes Embedded in Oriented Polymeric Nanofibers by Electrospinning. Langmuir 2004, 20, 9852–9855. [CrossRef]

- Dror, Y.; Salalha, W.; Khalfin, R.L.; Cohen, Y.; Yarin, A.L.; Zussman, E. Carbon Nanotubes Embedded in Oriented Polymer Nanofibers by Electrospinning. Langmuir 2003, 19, 7012–7020. [CrossRef]

- Sarabia-Riquelme, R.; Craddock, J.; Morris, E.A.; Eaton, D.; Andrews, R.; Anthony, J.; Weisenberger, M.C. Simple, Low-Cost, Water-Processable n -Type Thermoelectric Composite Films from Multiwall Carbon Nanotubes in Polyvinylpyrrolidone. Synth Met 2017, 225, 86–92. [CrossRef]

- Macagnano, A.; Molinari, F.N.; Mancini, T.; Lupi, S.; De Cesare, F. UV Light Stereoselective Limonene Sensor Using Electrospun PVP Composite Nanofibers. In Proceedings of the Eurosensors 2023; MDPI: Basel Switzerland, April 1 2024; p. 131. [CrossRef]

- Habboush, S.; Rojas, S.; Rodríguez, N.; Rivadeneyra, A. The Role of Interdigitated Electrodes in Printed and Flexible Electronics. Sensors 2024, 24, 2717. [CrossRef]

- Sarabia-Riquelme, R.; Craddock, J.; Morris, E.A.; Eaton, D.; Andrews, R.; Anthony, J.; Weisenberger, M.C. Simple, Low-Cost, Water-Processable n -Type Thermoelectric Composite Films from Multiwall Carbon Nanotubes in Polyvinylpyrrolidone. Synth Met 2017, 225, 86–92. [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Ma, P.C.; Chow, W.S.; To, C.K.; Tang, B.Z.; Kim, J. -K. Correlations between Percolation Threshold, Dispersion State, and Aspect Ratio of Carbon Nanotubes. Adv Funct Mater 2007, 17, 3207–3215. [CrossRef]

- Behnam, A.; Guo, J.; Ural, A. Effects of Nanotube Alignment and Measurement Direction on Percolation Resistivity in Single-Walled Carbon Nanotube Films. J Appl Phys 2007, 102. [CrossRef]

- Bauhofer, W.; Kovacs, J.Z. A Review and Analysis of Electrical Percolation in Carbon Nanotube Polymer Composites. Compos Sci Technol 2009, 69, 1486–1498. [CrossRef]

- Kovacs, J.Z.; Velagala, B.S.; Schulte, K.; Bauhofer, W. Two Percolation Thresholds in Carbon Nanotube Epoxy Composites. Compos Sci Technol 2007, 67, 922–928. [CrossRef]

- Penu, C.; Hu, G.; Fernandez, A.; Marchal, P.; Choplin, L. Rheological and Electrical Percolation Thresholds of Carbon Nanotube/Polymer Nanocomposites. Polym Eng Sci 2012, 52, 2173–2181. [CrossRef]

- Poulin, P.; Vigolo, B.; Launois, P. Films and Fibers of Oriented Single Wall Nanotubes. Carbon N Y 2002, 40, 1741–1749. [CrossRef]

- Serban, B.-C.; Cobianu, C.; Dumbravescu, N.; Buiu, O.; Bumbac, M.; Nicolescu, C.M.; Cobianu, C.; Brezeanu, M.; Pachiu, C.; Serbanescu, M. Electrical Percolation Threshold and Size Effects in Polyvinylpyrrolidone-Oxidized Single-Wall Carbon Nanohorn Nanocomposite: The Impact for Relative Humidity Resistive Sensors Design. Sensors 2021, 21, 1435. [CrossRef]

- Khan, W.S.; Asmatulu, R.; Eltabey, M.M. Electrical and Thermal Characterization of Electrospun PVP Nanocomposite Fibers. J Nanomater 2013, 2013, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Swenson, H.; Stadie, N.P. Langmuir’s Theory of Adsorption: A Centennial Review. Langmuir 2019, 35, 5409–5426. [CrossRef]

- Shanmgam, G.; Mathew, V.; Selvaraj, B.; Thanikachalam, P.M.; Kim, J.; Pichai, M.; Natarajan, A.; Almansour, A.I. Influence of Limonene from Orange Peel in Poly (Ethylene Oxide) PEO/I − /I 3 − Based Nanocrystalline Dye-Sensitized Solar Cell. ChemistrySelect 2022, 7. [CrossRef]

- Kandhasamy, M.; Shanmugam, G.; Kamaraj, S.; Selvaraj, B.; Gunasekeran, A.; Sambandam, A. Effect of D-Limonene Additive in Copper Redox-Based Quasi-Solid-State Electrolytes on the Performance of Dye-Sensitized Solar Cells. Mater Today Commun 2023, 35, 105505. [CrossRef]

- Peveler, W.J.; Yazdani, M.; Rotello, V.M. Selectivity and Specificity: Pros and Cons in Sensing. ACS Sens 2016, 1, 1282–1285. [CrossRef]

- Pan, X.; Xue, Q.; Zhang, J.; Guo, Q.; Jin, Y.; Lu, W.; Li, X.; Ling, C. Effective Enhancement of Humidity Sensing Characteristics of Novel Thermally Treated MWCNTs/Polyvinylpyrrolidone Film Caused by Interfacial Effect. Adv Mater Interfaces 2016, 3. [CrossRef]

- Shinde, D.B.; Vlassiouk, I. V.; Talipov, M.R.; Smirnov, S.N. Exclusively Proton Conductive Membranes Based on Reduced Graphene Oxide Polymer Composites. ACS Nano 2019, 13, 13136–13143. [CrossRef]

| Mean diameter [nm] | |

|---|---|

| MIP nps | 179,40 ± 43.00 |

| NIP nps | 117.15 ± 28.00 |

| R [Ohm] | W/L [µm] | Rs [Ohm/□] | |

|---|---|---|---|

| MIP fibres | 8.35∙108 ± 1.00∙108 | 2.86∙10-3 | 9.95∙103±1.20∙103 |

| NIP fibres | 1.54∙109 ± 1.85∙108 | 2.86∙10-3 | 18.35∙103±2.30∙103 |

| Type | Molar ratio | Sensing Layer | Transducer | Linear range [ppm] | LOD [ppm] | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T:Styrene:DVB | 0.06:1:1.5 | Film | QCM | 20-250 | 20 | [67] |

| T:MAA:EGDMA | 1:5:20 | Film | QCM | - | - | [66] |

| T:MAA:EGDMA | 1:4:20 | Film | QCM | 300 - 2100 | 7.43 | [69] |

| T:Styrene:DVB | 0.06:1:1.5 | Film | QCM/IDE | 50 | [71] | |

| T:MAA:EGDMA | 1:4:20 | Film | QCM | 1-1000 | - | [65] |

| T:MAA:EGDMA | 1:4:20 | Film | QCM | 10 | [64] | |

| MAA:EGDMA | 1:5:20 | Film | IDE | 1-400 | - | [70] |

| PAA:PVP:MWCNT | 1:4:8 | Nanofibers | IDE | 1-60 | 0.23 | [101] |

| Sensors | SENS (ppm-1) | LOD (ppb) | LOQ (ppb) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

MIP-NF sensors MINF sensors |

0.102 ± 0.022 0.037±0.001 |

190 226 |

630 - |

This study |

| [101] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).