Submitted:

02 January 2025

Posted:

03 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patients and Data

2.2. Treatment

2.3. Follow-Up and Long-Term Outcomes

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Patients and Treatment

3.2. Postoperative Staging, Pathohistological Characteristics and Long-Term Outcomes

3.3. Potential Prognostic Factors for Long-Term Outcomes

3.4. Univariate and Multivariate Regression Analysis and Risk Stratification

- Low-risk (LR) group: patients with a total number of positive lymph nodes fewer than 10.5 and without extrathyroidal extension,

- Intermediate-risk (IR) group: patients with either a total number of positive lymph nodes exceeding 10.5 or extrathyroidal tumor extension,

- High-risk (HR) group: patients with both total number of positive lymph nodes exceeding 10.5 and extrathyroidal tumor extension

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zanella, A.B.; Scheffel, R.S.; Weinert, L.; Dora, J.M.; Maia, A.L. New insights into the management of differentiated thyroid carcinoma in children and adolescents (Review). Int. J. Oncol. 2021, 58, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.; Ly, S.; Castroneves, L.A.; Frates, M.C.; Benson, C.B.; Feldman, H.A.; Wassner, A.J.; Smith, J.R.; Marqusee, E.; Alexander, E.K.; et al. A Standardized Assessment of Thyroid Nodules in Children Confirms Higher Cancer Prevalence Than in Adults. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2013, 98, 3238–3245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vergamini, L.B.; Frazier, A.L.; Abrantes, F.L.; Ribeiro, K.B.; Rodriguez-Galindo, C. Increase in the Incidence of Differentiated Thyroid Carcinoma in Children, Adolescents, and Young Adults: A Population-Based Study. J. Pediatr. 2014, 164, 1481–1485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Black, P.; Straaten, A.; Gutjahr, P. Secondary thyroid carcinoma after treatment for childhood cancer. Med Pediatr. Oncol. 1998, 31, 91–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonorezos, E.S.; Barnea, D.; Moskowitz, C.S.; Chou, J.F.; Sklar, C.A.; Elkin, E.B.; Wong, R.J.; Li, D.; Tuttle, R.M.; Korenstein, D.; et al. Screening for thyroid cancer in survivors of childhood and young adult cancer treated with neck radiation. J. Cancer Surviv. 2016, 11, 302–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moleti, M.; Aversa, T.; Crisafulli, S.; Trifirò, G.; Corica, D.; Pepe, G.; Cannavò, L.; Di Mauro, M.; Paola, G.; Fontana, A.; et al. Global incidence and prevalence of differentiated thyroid cancer in childhood: systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Endocrinol. 2023, 14, 1270518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, K.; Sharabiani, M.; Tumino, D.; Wadsley, J.; Gill, V.; Gerrard, G.; Sindhu, R.; Gaze, M.; Moss, L.; Newbold, K. Differentiated Thyroid Cancer in Children: A UK Multicentre Review and Review of the Literature. Clin. Oncol. 2019, 31, 385–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dinauer, C.A.W.; Tuttle, M.; Robie, D.K.; McClellan, D.R.; Svec, R.L.; Adair, C.; Francis, G.L. Clinical features associated with metastasis and recurrence of differentiated thyroid cancer in children, adolescents and young adults. Clin. Endocrinol. 1998, 49, 619–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaukar, D.A.; Rangarajan, V.; Nair, N.; Dcruz, A.K.; Nadkarni, M.S.; Pai, P.S.; Mistry, R.C. Pediatric thyroid cancer. J. Surg. Oncol. 2005, 92, 130–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgard, C.; Zacherl, M.J.; Todica, A.; Hornung, J.; Grawe, F.; Pekrul, I.; Zimmermann, P.; Schmid-Tannwald, C.; Ladurner, R.; Krenz, D.; et al. Primary presentation and clinical course of pediatric and adolescent patients with differentiated thyroid carcinoma after radioiodine therapy. Front. Oncol. 2023, 13, 1237472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francis, G.L.; Waguespack, S.G.; Bauer, A.J.; Angelos, P.; Benvenga, S.; Cerutti, J.M.; Dinauer, C.A.; Hamilton, J.; Hay, I.D.; Luster, M.; et al. Management Guidelines for Children with Thyroid Nodules and Differentiated Thyroid cancer: The American Thyroid Association guidelines task force on pediatric thyroid cancer. Thyroid 2015, 25, 716–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- A Lebbink, C.; Links, T.P.; Czarniecka, A.; Dias, R.P.; Elisei, R.; Izatt, L.; Krude, H.; Lorenz, K.; Luster, M.; Newbold, K.; et al. 2022 European Thyroid Association Guidelines for the management of pediatric thyroid nodules and differentiated thyroid carcinoma. Eur. Thyroid. J. 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dzodic, R. Sentinel Lymph Node Biopsy May Be Used to Support the Decision to Perform Modified Radical Neck Dissection in Differentiated Thyroid Carcinoma. World J. Surg. 2006, 30, 841–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polo, T.C.F.; Miot, H.A. Aplicações da curva ROC em estudos clínicos e experimentais. J. Vasc. Bras. 2020, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shapiro, N.L.; Bhattacharyya, N. Population-Based Outcomes for Pediatric Thyroid Carcinoma. Laryngoscope 2005, 115, 337–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lazar, L.; Lebenthal, Y.; Steinmetz, A.; Yackobovitch-Gavan, M.; Phillip, M. Differentiated Thyroid Carcinoma in Pediatric Patients: Comparison of Presentation and Course between Pre-pubertal Children and Adolescents. J. Pediatr. 2009, 154, 708–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, W.; Zhang, S.; Gao, Z.; Tao, Y.; Wang, X.; Cheng, J. Children and adolescents with differentiated thyroid cancer from 1998 to 2018: a retrospective analysis. J. Pediatr. Endocrinol. Metab. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puga, F.M.; Correia, L.; Vieira, I.; Caetano, J.S.; Cardoso, R.; Dinis, I.; Mirante, A. Differentiated Thyroid Cancer in Children and Adolescents: 12-year Experience in a Single Center. J. Clin. Res. Pediatr. Endocrinol. 2024, 16, 314–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balachandar, S.; La Quaglia, M.; Tuttle, R.M.; Heller, G.; Ghossein, R.A.; Sklar, C.A. Pediatric Differentiated Thyroid Carcinoma of Follicular Cell Origin: Prognostic Significance of Histologic Subtypes. Thyroid® 2016, 26, 219–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, X.-C.; Yu, W.-Q.; Shang, J.-B.; Wang, K.-J. Clinical characteristics and treatment of thyroid cancer in children and adolescents: a retrospective analysis of 83 patients. J. Zhejiang Univ. B 2017, 18, 430–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paulson, V.A.; Rudzinski, E.R.; Hawkins, D.S. Thyroid Cancer in the Pediatric Population. Genes 2019, 10, 723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, P.-Y.; Liu, J.; Xue, S.; Chen, G. Pediatric differentiated thyroid carcinoma: The clinicopathological features and the coexistence of Hashimoto's thyroiditis. Asian J. Surg. 2019, 42, 112–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taş, F.; Bulut, S.; Eğilmez, H.; Öztoprak, I.; Ergür, A.T.; Candann, F. Normal thyroid volume by ultrasonography in healthy children. Ann. Trop. Paediatr. 2002, 22, 375–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sugino, K.; Nagahama, M.; Kitagawa, W.; Ohkuwa, K.; Uruno, T.; Matsuzu, K.; Suzuki, A.; Tomoda, C.; Hames, K.Y.; Akaishi, J.; et al. Risk Stratification of Pediatric Patients with Differentiated Thyroid Cancer: Is Total Thyroidectomy Necessary for Patients at Any Risk? Thyroid® 2020, 30, 548–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wada, N.; Sugino, K.; Mimura, T.; Nagahama, M.; Kitagawa, W.; Shibuya, H.; Ohkuwa, K.; Nakayama, H.; Hirakawa, S.; Yukawa, N.; et al. Treatment Strategy of Papillary Thyroid Carcinoma in Children and Adolescents: Clinical Significance of the Initial Nodal Manifestation. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2009, 16, 3442–3449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaisman, F.; Bulzico, D.A.; Pessoa, C.H.C.N.; Bordallo, M.A.N.; De Mendonça, U.B.T.; Dias, F.L.; Coeli, C.M.; Corbo, R.; Vaisman, M. Prognostic factors of a good response to initial therapy in children and adolescents with differentiated thyroid cancer. Clinics 2011, 66, 281–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanella, A.B.; Scheffel, R.S.; Nava, C.F.; Golbert, L.; Meyer, E.L.d.S.; Punales, M.; Gonçalves, I.; Dora, J.M.; Maia, A.L. Dynamic Risk Stratification in the Follow-Up of Children and Adolescents with Differentiated Thyroid Cancer. Thyroid® 2018, 28, 1285–1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.-M.; Lo, C.-Y.; Lam, K.-Y.; Wan, K.-Y.; Tam, P.K. Well-differentiated thyroid carcinoma in Hong Kong Chinese patients under 21 years of age: a 35-year experience. J. Am. Coll. Surg. 2002, 194, 711–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tuttle, R.M.; Haugen, B.; Perrier, N.D. Updated American Joint Committee on Cancer/Tumor-Node-Metastasis Staging System for Differentiated and Anaplastic Thyroid Cancer (Eighth Edition): What Changed and Why? Thyroid 2017, 27, 751–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tuttle, R.M.; Tala, H.; Shah, J.; Leboeuf, R.; Ghossein, R.; Gonen, M.; Brokhin, M.; Omry, G.; Fagin, J.A.; Shaha, A. Estimating Risk of Recurrence in Differentiated Thyroid Cancer After Total Thyroidectomy and Radioactive Iodine Remnant Ablation: Using Response to Therapy Variables to Modify the Initial Risk Estimates Predicted by the New American Thyroid Association Staging System. Thyroid® 2010, 20, 1341–1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Momesso, D.P.; Tuttle, R.M. Update on Differentiated Thyroid Cancer Staging. Endocrinol. Metab. Clin. North Am. 2014, 43, 401–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lazar, L.; Lebenthal, Y.; Segal, K.; Steinmetz, A.; Strenov, Y.; Cohen, M.; Yaniv, I.; Yackobovitch-Gavan, M.; Phillip, M. Pediatric Thyroid Cancer: Postoperative Classifications and Response to Initial Therapy as Prognostic Factors. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2016, 101, 1970–1979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, T.Y.; Jeon, M.J.; Lee, Y.H.; Lee, Y.-M.; Kwon, H.; Yoon, J.H.; Chung, K.-W.; Kim, W.G.; Song, D.E.; Hong, S.J. Initial and Dynamic Risk Stratification of Pediatric Patients with Differentiated Thyroid Cancer. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2016, 102, 793–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haugen, B.R.; Alexander, E.K.; Bible, K.C.; Doherty, G.M.; Mandel, S.J.; Nikiforov, Y.E.; Pacini, F.; Randolph, G.W.; Sawka, A.M.; Schlumberger, M.; et al. 2015 American Thyroid Association Management Guidelines for Adult Patients with Thyroid Nodules and Differentiated Thyroid Cancer: The American Thyroid Association Guidelines Task Force on Thyroid Nodules and Differentiated Thyroid Cancer. Thyroid 2016, 26, 1–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Newman, K.D.; Black, T.; Heller, G.; Azizkhan, R.G.; Holcomb, G.W.; Sklar, C.; Vlamis, V.; Haase, G.M.; La Quaglia, M.P. Differentiated Thyroid Cancer: Determinants of Disease Progression in Patients <21 Years of Age at Diagnosis. Ann. Surg. 1998, 227, 533–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Massimino, M.; Collini, P.; Leite, S.F.; Spreafico, F.; Zucchini, N.; Ferrari, A.; Mattavelli, F.; Seregni, E.; Castellani, M.R.; Cantù, G.; et al. Conservative surgical approach for thyroid and lymph-node involvement in papillary thyroid carcinoma of childhood and adolescence. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2005, 46, 307–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Characteristics | Total | Children (≤16) | Adolescents (>16) | Pearson χ2 test |

| Follow-up (years) | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 16.2 (10.3) | 15.8 (10.7) | 16.5 (10.1) | ns# |

| Median (Range) | 15.6 (0.6-43.6) | 14.8 (0.7-39.9) | 16.3 (0.6-43.6) | |

| Patient characteristics | ||||

| Sex | ||||

| Female | 75 (75.76%) | 29 (74.36%) | 46 (76.67%) | ns |

| Male | 24 (24.24%) | 10 (25.64%) | 14 (23.33%) | |

| Age (years) | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 16.66 (3.41) | 13.08 (2.14) | 18.98 (1.61) | - |

| Median (Range) | 17 (7-21) | 13 (7-16) | 20 (17-21) | |

| Preoperative RT* | ||||

| Yes | 4 (4.04%) | 3 (7.69%) | 1 (1.67) | ns♦ |

| No | 95 (95.96%) | 36 (92.31%) | 59 (98.33%) | |

| Surgery | ||||

| Thyroid | ||||

| TT | 96 (96.97%) | 39 (100%) | 57 (95%) | ns♦ |

| Near TT | 3 (3.03%) | 0 (0%) | 3 (5%) | |

| CND | ||||

| Yes | 94 (94.95%) | 37 (94,87%) | 57 (95%) | ns♦ |

| No | 5 (5.05%) | 2 (5.13%) | 3 (5%) | |

| SLNB | ||||

| Yes | 50 (50.51%) | 18 (46.15%) | 32 (53.33%) | ns |

| No | 49 (49.49%) | 21 (53.85%) | 28 (46.67%) | |

| MRND | ||||

| Unilateral | 50 (50.51%) | 18 (46.15%) | 32 (53.33%) | ns |

| Bilateral | 18 (18.18%) | 11 (28.21%) | 7 (11.67%) | |

| No | 31 (31.31%) | 10 (25.64%) | 21 (35%) | |

| RAI treatment | ||||

| Yes | 74 (74.75%) | 32 (82.05%) | 42 (70%) | ns |

| No | 25 (25.25%) | 7 (17.95%) | 18 (30%) | |

| Postoperative external beam RT | ||||

| Yes | 4 (4.04%) | 1 (2.56%) | 3 (5%) | ns♦ |

| No | 95 (95.96%) | 38 (97.44%) | 57 (95%) | |

| Total | 99 (100%) | 39 (100%) | 60 (100%) | |

| Characteristics | Total | Children (≤16) | Adolescents (>16) | Pearson χ2 test |

| Thyroid cancer type | ||||

| PTC | 95 (95.96%) | 37 (94.87%) | 58 (96.67%) | ns♦ |

| FTC | 3 (3.03%) | 2 (5.13%) | 1 (1.67%) | |

| Hürthle cell | 1 (1.01%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (1.67%) | |

| TNM staging* | ||||

| pT | ||||

| pT1a | 20 (20.20%) | 7 (17.95%) | 13 (21.67%) | ns |

| pT1b | 28 (28.28%) | 7 (17.95%) | 21 (35%) | |

| pT2 | 17 (17.17%) | 5 (12.82%) | 12 (20%) | |

| pT3 | 20 (20.20%) | 11 (28.21%) | 9 (15%) | |

| pT4 | 14 (14.14%) | 9 (23%) | 5 (8.33%) | |

| pN | ||||

| pN0 | 27 (27.27%) | 11 (28.21%) | 16 (26.67%) | ns♦ |

| pN1a | 8 (8.08%) | 2 (5.13%) | 6 (10%) | |

| pN1b | 64 (64.65%) | 26 (66.67%) | 38 (63.33%) | |

| cM | ||||

| cM0 | 91 (91.92%) | 34 (87.18%) | 57 (95%) | ns♦ |

| cM1 | 8 (8.08%) | 5 (12.82%) | 3 (5%) | |

| Tumor size (mm) | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 22.3 (14.94) | 26.23 (16.77) | 19.75 (13.14) | ns# |

| Median (range) | 19 (0-70) | 22 (1-70) | 18 (0-60) | |

| Central lymph nodes (number) | ||||

| Positive | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 5.1 (6) | 5.23 (5.57) | 5.02 (6.3) | ns# |

| Median (range) | 4 (0-29) | 4 (0-20) | 3 (0-29) | |

| Total | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 10. 76 (7.66) | 10.82 (7.2) | 10.72 (8) | ns# |

| Median (range) | 8 (0-30) | 11 (0-25) | 7.5 (0-30) | |

| Lateral lymph nodes (number) | ||||

| Positive | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 4.69 (6.18) | 6.26 (7.04) | 3.67 (5.36) | ns# |

| Median (range) | 2 (0-25) | 4 (0-24) | 2 (0-25) | |

| Total | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 17.45 (13.4) | 19.84 (14.55) | 17.44 (12.12) | ns# |

| Median (range) | 16 (0-60) | 19 (1-60) | 15 (1-48) | |

| Multifocality | ||||

| No | 50 (50.51%) | 12 (30.77%) | 38 (63.33%) | <0.01 |

| Yes | 49 (49.49%) | 27 (69.23%) | 22 (36.67%) | |

| Capsular invasion | ||||

| No | 44 (44.44%) | 10 (25.64%) | 34 (56.67%) | <0.01 |

| Yes | 55 (55.56%) | 29 (74.36%) | 26 (43.33%) | |

| Extrathyroidal extension | ||||

| No | 65 (65.66%) | 21 (53.85%) | 44 (73.33%) | <0.05 |

| Yes | 34 (34.34%) | 18 (46.15%) | 16 (26.67%) | |

| Evidence of disease | ||||

| NED | 91 (91.92%) | 34 (87.18%) | 57 (95%) | ns♦ |

| ED | 8 (8.08%) | 5 (12.82%) | 3 (5%) | |

| Total | 99 (100%) | 39 (100%) | 60 (100%) | |

| Outcome | Total | Children (≤16) | Adolescents (>16) | Pearson χ2 test |

| Event | ||||

| NED pts | ||||

| With recurrence | 17 (18.68%) | 5 (14.71%) | 12 (21.05%) | ns |

| Without recurrence | 74 (81.32%) | 29 (85.29%) | 45 (78.95%) | |

| Total | 91 (100%) | 34 (100%) | 57 (100%) | - |

| ED pts | ||||

| With progression | 7 (87.5%) | 5 (100%) | 2 (66.67%) | ns♦ |

| Without progression | 1 (12.5%) | - | 1 (33.33%) | |

| Total | 8 (100%) | 5 (100%) | 3 (100%) | - |

| Adverse events in all pts | ||||

| With adverse event | 24 (24.24%) | 10 (25.64%) | 14 (23.33%) | ns |

| Without adverse event | 75 (75.76%) | 29 (74.36%) | 46 (76.67%) | |

| Total | 99 (100%) | 39 (100%) | 60 (100%) | - |

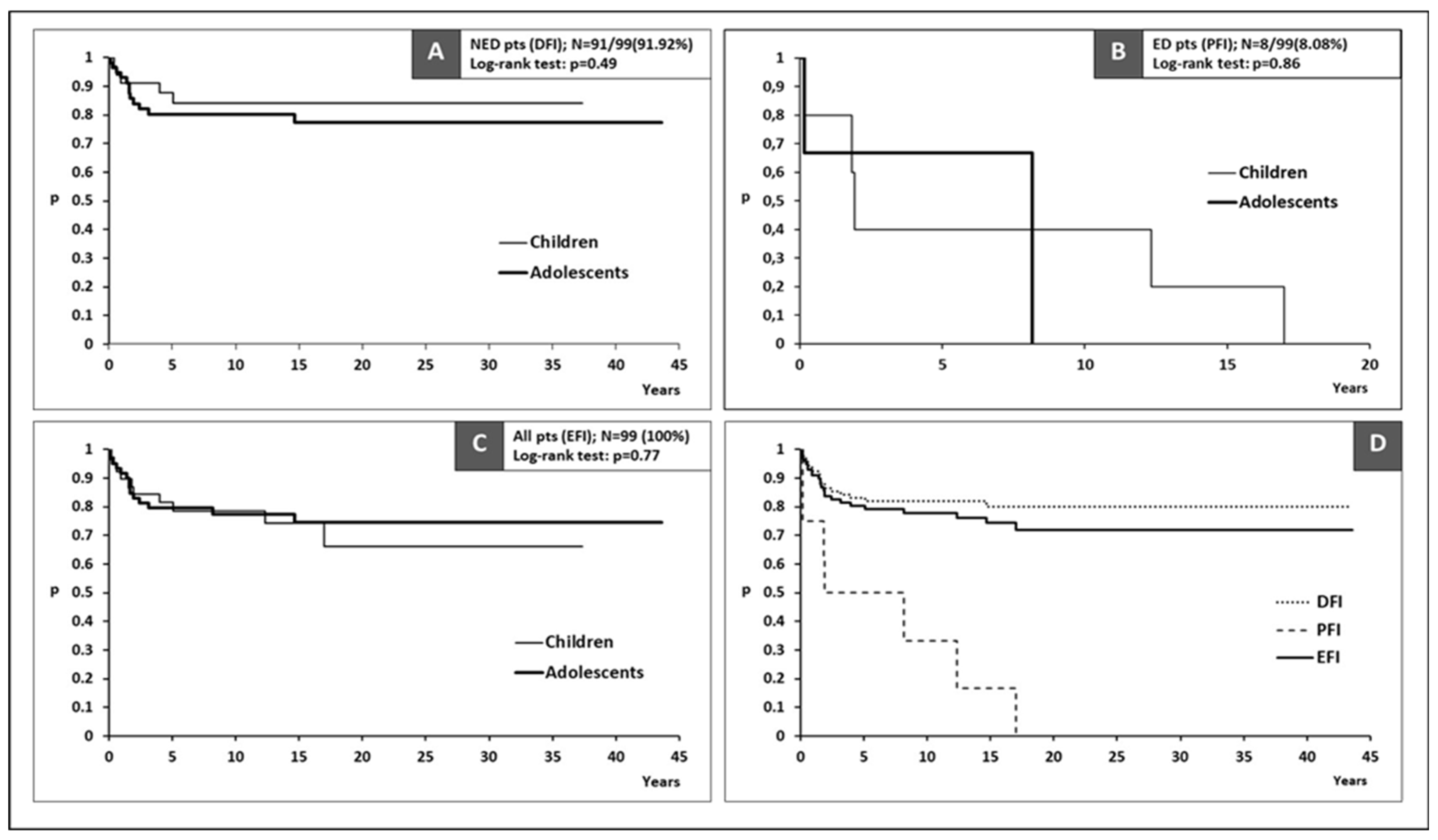

| Time to event | ||||

| DFI (years) for NED pts | ||||

| Median (95%CI) | NR | NR | NR | ns* |

| PFI (years) for ED pts | ||||

| Median (95%CI) | 5 (>1.8) | 1.9 (>1.8) | 8.1 (>0.2) | ns* |

| EFI (years) for all pts | ||||

| Median (95%CI) | NR | NR | NR | ns* |

| Characteristics | Event (relapse/progression) | Event-free interval (years) | |||

| Without | With | Test | Median EFI (95%CI) | Log-rank test | |

| Age (years) | |||||

| Children | 29 (38.67%) | 10 (41.67%) | ns | NR (>17) | ns |

| Adolescents | 46 (61.33%) | 14 (58.33%) | NR | ||

| Sex | |||||

| Female | 56 (74.67%) | 19 (79.17%) | ns | NR | ns |

| Male | 19 (25.33%) | 5 (20.83%) | NR | ||

| Tumor size (ROC) | |||||

| ≤30.5 mm | 64 (85.33%) | 11 (45.83%) | <0.01 | NR | <0.01 |

| >30.5 mm | 11 (14.67%) | 13 (54.17%) | 4.8 (>1.6) | ||

| Multifocality | |||||

| No | 41 (54.67%) | 9 (37.5%) | ns | NR | ns |

| Yes | 34 (45.33%) | 15 (62.5%) | NR (>17) | ||

| cM1 at diagnosis | |||||

| No | 74 (98.67%) | 17 (70.83%) | <0.01 | NR | <0.01 |

| Yes | 1 (1.33%) | 7 (29.17%) | 5 (>1.8) | ||

| Capsular invasion | |||||

| No | 41 (54.67%) | 3 (12.5%) | <0.01 | NR | <0.01 |

| Yes | 34 (45.33%) | 21 (87.5%) | NR (>12.3) | ||

| Positive LN (ROC) | |||||

| ≤10.5 | 58 (77.33%) | 4 (16.67%) | <0.01 | NR | <0.01 |

| >10.5 | 17 (22.67%) | 20 (83.33%) | 12.3 (>3.2) | ||

| Extrathyroidal extension | |||||

| No | 59 (78.67%) | 6 (25%) | <0.01 | NR | <0.01 |

| Yes | 16 (21.33%) | 18 (75%) | 14.7 (>1.8) | ||

| Total | 75 (100%) | 24 (100%) | - | - | - |

| Characteristics | Logistic regression for event (relapse/progression) | |||

| Univariate | Multivariate | |||

| OR (95%CI) | Wald Test | OR (95%CI) | Wald Test | |

| Tumor size (ROC) | ||||

| >30.5 mm: ≤30.5 mm | 6.9 (2.5-19.2) | <0.01 | - | ns |

| Initially metastatic | ||||

| Yes: No | 30.5 (3.5-264.2) | <0.01 | - | ns |

| Capsular invasion | ||||

| Yes: No | 8.4 (2.3-30.7) | <0.01 | - | ns |

| Positive LN (ROC) | ||||

| >10.5: ≤10.5 | 17.1 (5.1-56.7) | <0.01 | 6.4 (1.7-24.6) | <0.01 |

| Extrathyroidal extension | ||||

| Yes: No | 11.1 (3.8-32.5) | <0.01 | 5.1 (1.4-18.3) | <0.01 |

| Characteristics | Cox regression for EFI | |||

| Univariate | Multivariate | |||

| HR (95%CI) | Wald Test | HR (95%CI) | Wald Test | |

| Tumor size (ROC) | ||||

| >30.5 mm: ≤30.5 mm | 5.63 (2.49-12.71) | <0.01 | - | ns |

| Initially metastatic | ||||

| Yes: No | 6.6 (2.72-16.01) | <0.01 | - | ns |

| Capsular invasion | ||||

| Yes: No | 6.76 (2.01-22.69) | <0.01 | - | ns |

| Positive LN (ROC) | ||||

| >10.5: ≤10.5 | 11.36 (3.87-33.36) | <0.01 | 6.48 (2.05-20.51) | <0.01* |

| Extrathyroidal extension | ||||

| Yes: No | 8.02 (3.17-20.29) | <0.01 | 3.83 (1.42-10.36) | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).