Submitted:

01 April 2025

Posted:

01 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Source and Selection

2.2. Analysis

3. Results

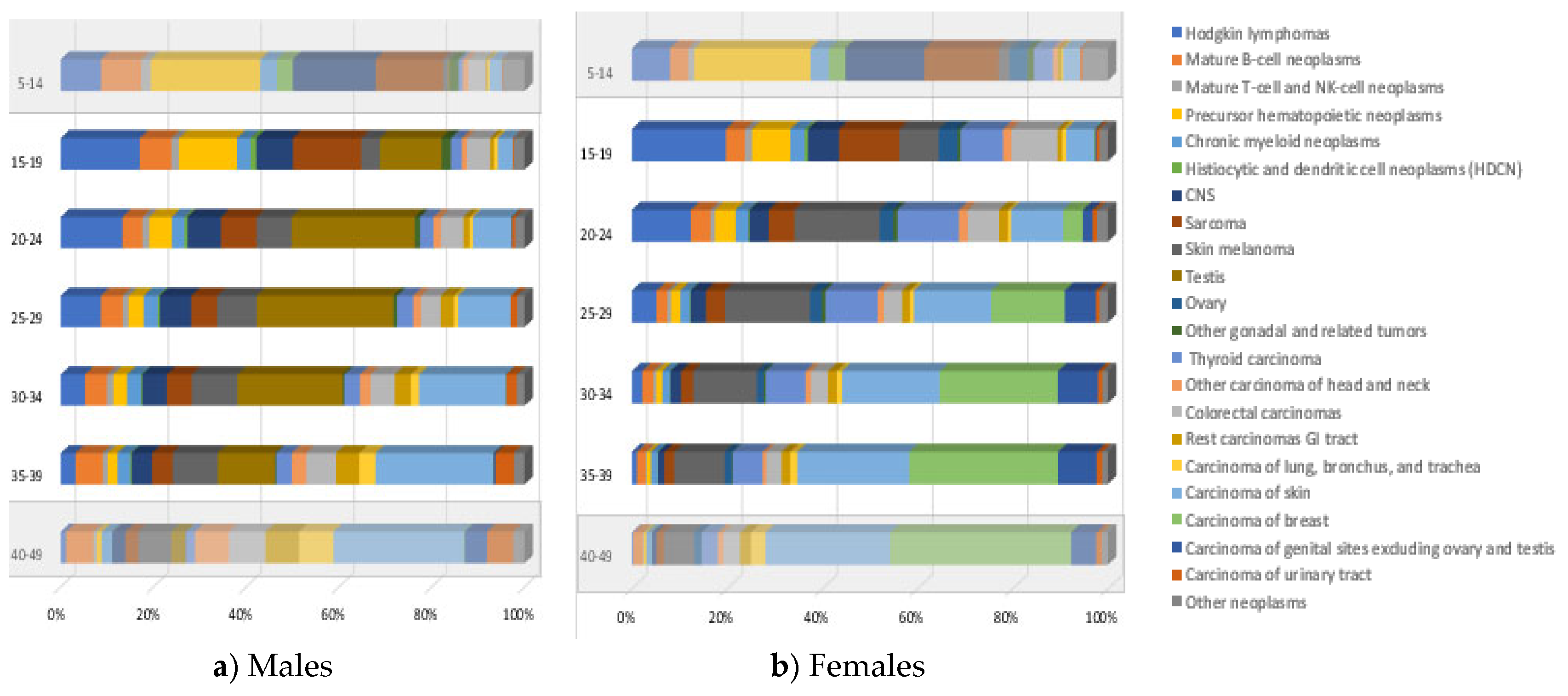

3.1. Incidence

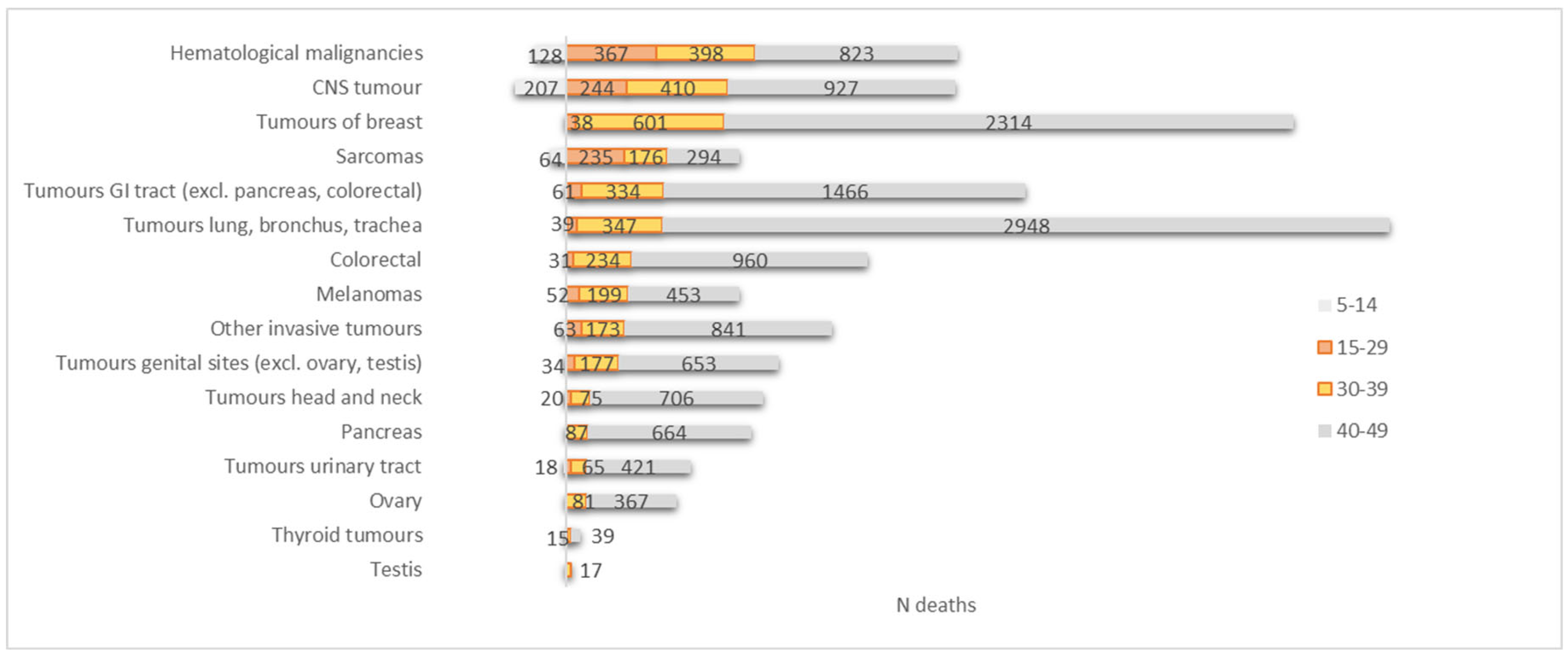

3.2. Mortality

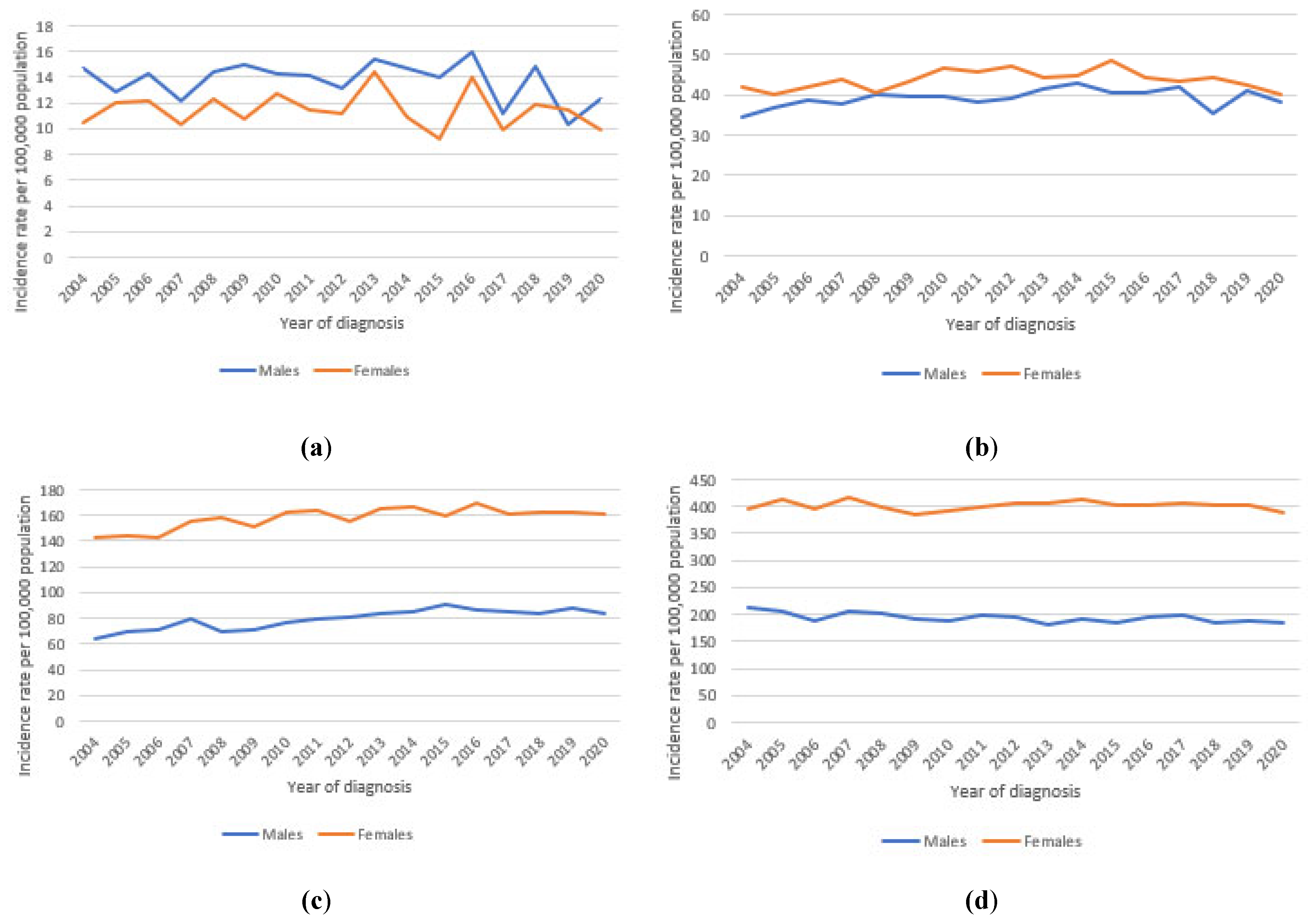

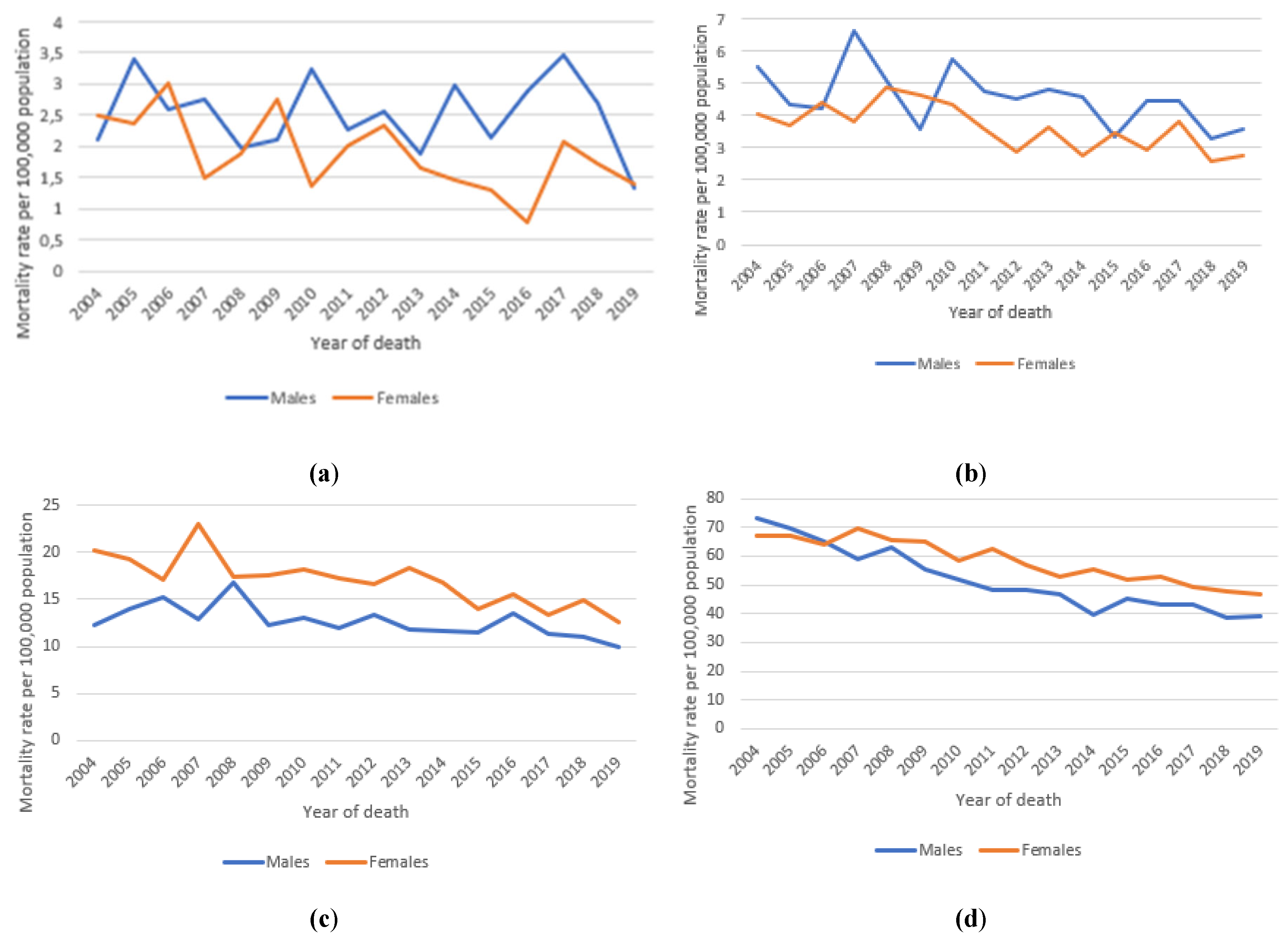

3.3. Long-Term Trends in Incidence and Mortality

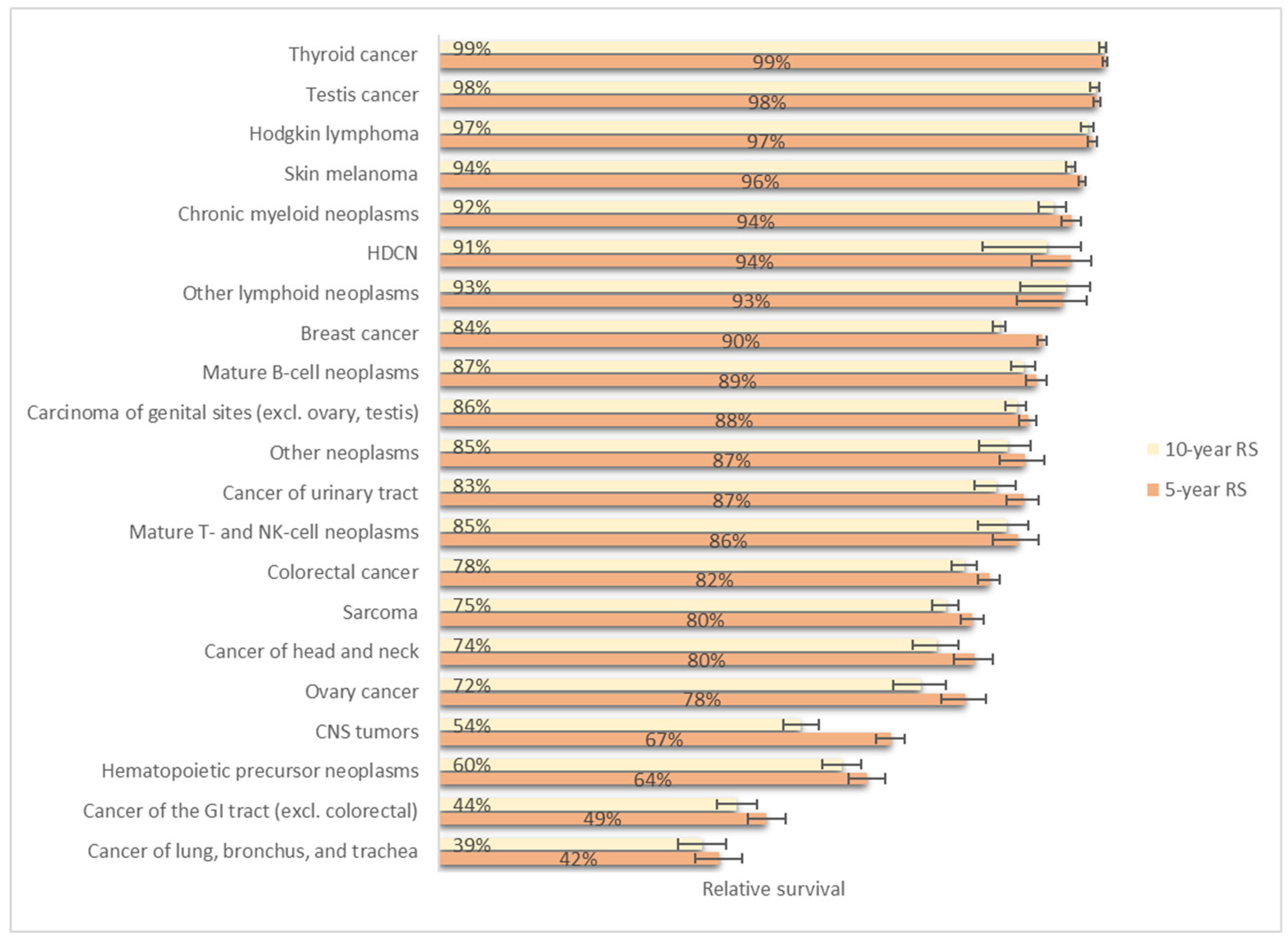

3.4. Relative Survival

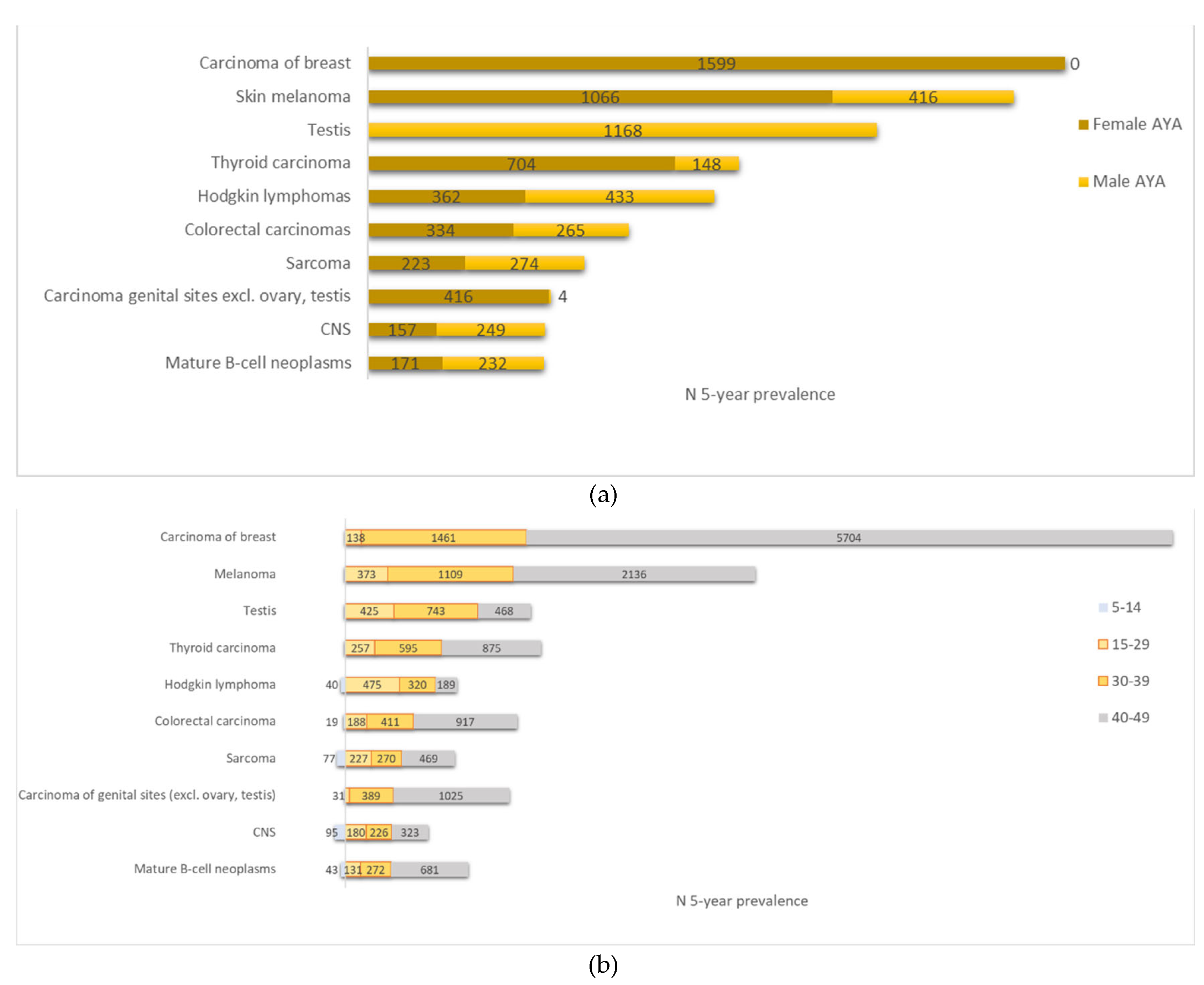

3.5. Prevalence

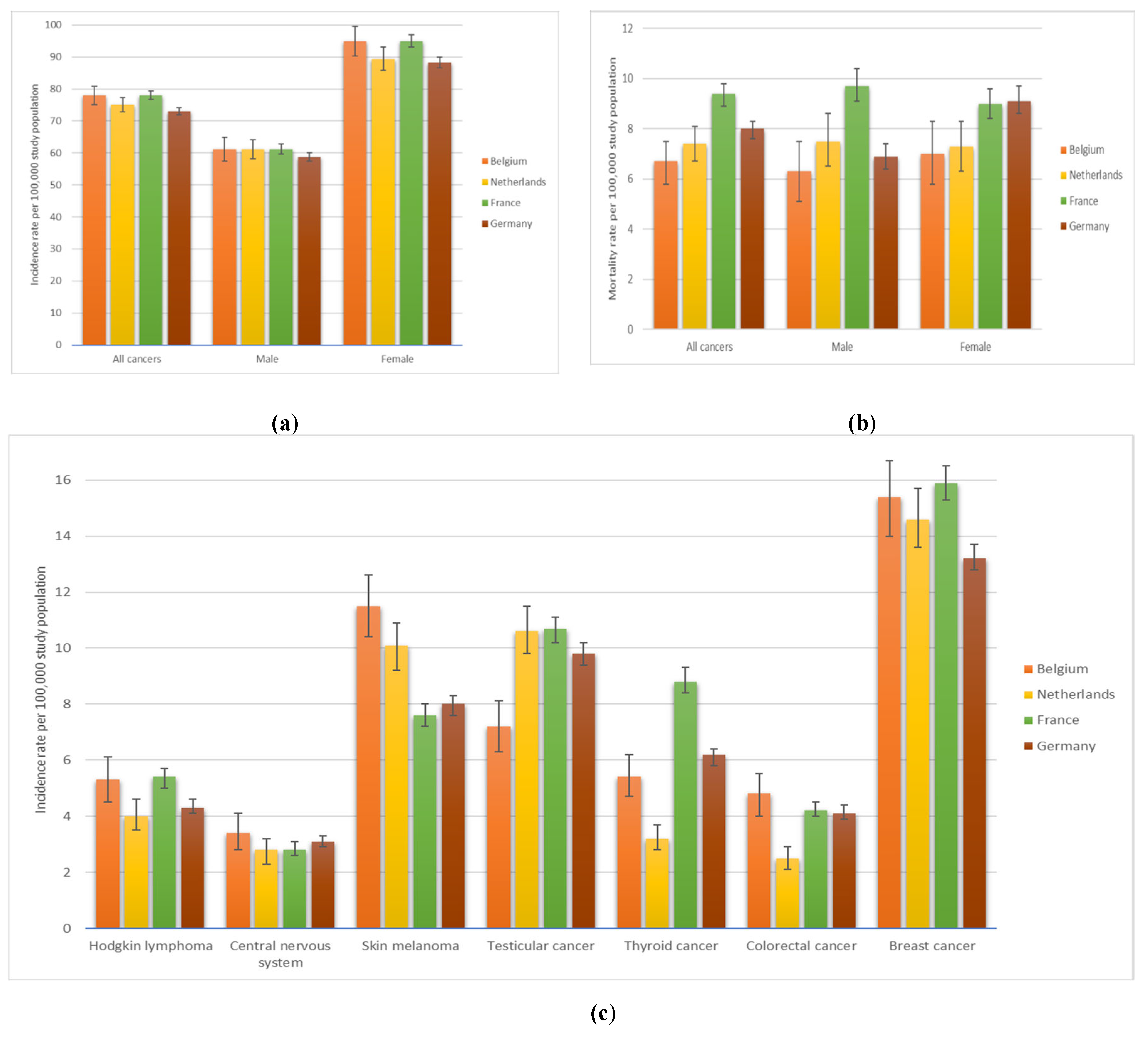

3.6. International Comparison

4. Discussion

4.2. Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Belgian Cancer Registry. https://kankerregister.org/default.aspx?lang=EN.

- StatBel. Structure of the Population Based on the National Register: 2024. https://statbel.fgov.be/.

- GBD 2019 Adolescent Young Adult Cancer Collaborators. The Global Burden of Adolescent and Young Adult Cancer in 2019: A Systematic Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Oncol. 2022, 23, 27–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trama, A.; Stark, D.; Bozovic-Spasojevic, I.; Gaspar, N.; Peccatori, F.; Toss, A.; Bernasconi, A.; Quarello, P.; Scheinemann, K.; Jezdic, S.; Blondeel, A.; Mountzios, G.; Bielack, S.; Saloustros, E.; Ferrari, A. Cancer Burden in Adolescents and Young Adults in Europe. ESMO Open 2023, 8, 100744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Harper, A.; Ruan, Y.; Barr, R.; Frazier, L.; Ferlay, J.; Steliarova-Foucher, E.; Fidler-Benaoudia, M. International Trends in the Incidence of Cancer Among Adolescents and Young Adults. Journal of the National Cancer Institute 2020, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC), WHO. Cancer Incidence in Five Continents (CI5). https://ci5.iarc.fr/ci5plus/.

- You, L.; Lv, Z.; Li, C.; Ye, W.; Zhou, Y.; Jin, J.; Han, Q. Worldwide Cancer Statistics of Adolescents and Young Adults in 2019: A Systematic Analysis of the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. ESMO Open 2021, 6, 100255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Global Burden of Disease (GBD) 2021; Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME)., 2024. http://www.healthdata.org/results/data-visualizations.

- Trama, A.; Botta, L.; Stiller, C.; Visser, O.; Cañete-Nieto, A.; Spycher, B.; Bielska-Lasota, M.; Katalinic, A.; Vener, C.; Innos, K.; Marcos-Gragera, R.; Paapsi, K.; Guevara, M.; Demuru, E.; Mousavi, S.M.; Blum, M.; Eberle, A.; Ferrari, A.; Bernasconi, A.; Lasalvia, P. Survival of European Adolescents and Young Adults Diagnosed with Cancer in 2010–2014. European Journal of Cancer 2024, 202, 113558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trama, A.; Botta, L.; Foschi, R.; Ferrari, A.; Stiller, C.; Desandes, E.; Maule, M.M.; Merletti, F.; Gatta, G. Survival of European Adolescents and Young Adults Diagnosed with Cancer in 2000-07: Population-Based Data from EUROCARE-5. Lancet Oncol 2016, 17, 896–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, K.D.; Fidler-Benaoudia, M.; Keegan, T.H.; Hipp, H.S.; Jemal, A.; Siegel, R.L. Cancer Statistics for Adolescents and Young Adults, 2020. CA Cancer J Clin. 2020, 70, 443–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrari, A.; Stark, D.; A Peccatori, F.; Fern, L.; Laurence, V.; Gaspar, N.; Bozovic-Spasojevic, I.; Smith, O.; De Munter, J.; Derwich, K.; Hjorth, L.; T A van der Graaf, W.; Soanes, L.; Jezdic, S.; Blondeel, A.; Bielack, S.; Douillard, J.-Y.; Mountzios, G.; Saloustros, E. Adolescents and Young Adults (AYA) with Cancer: A Position Paper from the AYA Working Group of the European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) and the European Society for Paediatric Oncology (SIOPE). ESMO Open 2021, 6, 100096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barr, R. Common Cancers in Adolescents. Cancer treatment reviews 2007, 33, 597–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- US Department of Health And Human Services; US National Institutes of Health; US National Cancer Institute; Adolescent and Young Adult Oncology Progress Report Group. Closing the Gap: Research and Care Imperatives for Adolescents and Young Adults with Cancers, 2006. https://www.livestrong.org/sites/default/files/what-we-do/reports/ayao_prg_report_2006_final.pdf.

- Saloustros, E.; Stark, D.; Michailidou, K.; Mountzios, G.; Brugieres, L.; Peccatori, F.; Jezdic, S.; Essiaf, S.; Douillard, J.-Y.; Bielack, S. The Care of Adolescents and Young Adults with Cancer: Results of the ESMO/SIOPE Survey. ESMO Open 2017, 2, e000252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Convention Entre Le Comité de l’assurance Du Service Des Soins de Santé de l’INAMI et Les Établissements Hospitaliers Pour Le Financement Des Équipes de Référence AJA Visant à Soutenir Des Soins Sur Mesure Aux AJA Atteints d’un Cancer. Note CSS 2023/321 (8 November 2023). Overeenkomst Tussen Het Verzekeringscomité van de Gezondheidszorgdienst van Het RIZIV En de Ziekenhuizen Voor de Financiering van AJA-Referentieteams Met Als Doel Op Maat Gemaakte Zorg Te Ondersteunen Voor AYA’s (Adolescenten En Jongvolwassenen) Die Getroffen Zijn Door Kanker. Nota CSS 2023/321 (8 November 2023). https://www.inami.fgov.be/fr/actualites/cancer-une-prise-en-charge-sur-mesure-pour-les-adolescents-et-jeunes-adultes-grace-a-notre-financement-d-equipes-de-reference-aja ; https://www.riziv.fgov.be/nl/nieuws/zorg-op-maat-voor-adolescenten-en-jongvolwassenen-met-kanker-dankzij-onze-vergoeding-van-aya-referentieteams (accessed 2024-08-22).

- Barr, R.; Ries, L.; Trama, A.; Gatta, G.; Steliarova-Foucher, E.; Stiller, C.; Bleyer, A. A System for Classifying Cancers Diagnosed in Adolescents and Young Adults. Cancer 2020, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steliarova-Foucher, E.; Stiller, C.; Lacour, B.; Kaatsch, P. International Classification of Childhood Cancer, Third Edition. Cancer 2005, 103, 1457–1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Cancer Institute. Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program. AYA Site Recode 2020 Revision. 2020. https://seer.cancer.gov/ayarecode/aya-2020.html.

- Berkman, A.M.; Mittal, N.; Roth, M.E. Adolescent and Young Adult Cancers: Unmet Needs and Closing the Gaps. Current Opinion in Pediatrics 2023, 35, 84–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Victorson, D.; Garcia, S.; Sanford, S.; Snyder, M.; Lampert-Okin, S.; Salsman, J. A Qualitative Focus Group Study to Illuminate the Lived Emotional and Social Impacts of Cancer and Its Treatment on Young Adults. Journal of Adolescent and Young Adult Oncology 2019, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- BSPHO: Yves Benoit, An Van Damme, Christophe Chantrain, Anne Uyttebroeck. Cancer Incidence in Belgium, 2010. Special Issue: Cancer in Children and Adolescents, 2013. https://kankerregister.org/en/publicaties/cancer-incidence-belgium-2010-special-issue-cancer-children-and-adolescents.

- Cancer in Children and Adolescents in Belgium, 2004-2020, D/2023/11.846/1; Belgian Cancer Registry, 2023. https://kankerregister.org/en/publicaties/cancer-children-and-adolescents-belgium-2004-2020.

- Cancer in Children and Adolescents in Belgium, 2004-2016; D/2019/11.846/1. Belgian Cancer Registry, 2019. https://kankerregister.org/en/publicaties/cancer-children-and-adolescents-belgium-2004-2016.

- Cancer in Adolescents and Young Adults, Belgium 2004-2022; D/2025/11.846/1; Belgian Cancer Registry: Brussels, 2025; https://kankerregister.org/en/publicaties/cancer-adolescents-and-young-adults-belgium-2004-2022.

- Federale Overheidsdienst Volksgezondheid, Veiligheid van de Voedselketen En Leefmilieu/Service Public Federal Sante Publique, Securite de La Chaine Alimentaire et Environnement. Koninklijk Besluit Houdende Vaststelling van de Normen Waaraan Het Zorgprogramma Voor Oncologische Basiszorg En Het Zorgprogramma Voor Oncologie Moeten Voldoen Om Te Worden Er-Kend/Arrêté Royal Fixant Les Normes Auxquelles Le Programme de Soins de Base En Oncologie et Le Programme de Soins d’oncologie Doivent Répondre Pour Être Agréés.; 2003. https://etaamb.openjustice.be/nl/koninklijk-besluit-van-21-maart-2003_n2003022324 https://etaamb.openjustice.be/fr/arrete-royal-du-21-mars-2003_n2003022324.

- Federale Overheidsdienst Volksgezondheid, Veiligheid van de Voedselketen En Leefmilieu/Service Public Federal Sante Publique, Securite de La Chaine Alimentaire et Environnement. Wet Houdende Diverse Bepalingen Betreffende Gezondheid/Loi Portant Dispositions Diverses En Matière de Santé.; 2006. https://etaamb.openjustice.be/nl/wet-van-13-december-2006_n2006023386.html https://etaamb.openjustice.be/fr/loi-du-13-decembre-2006_n2006023386.

- Statbel. Mortality, Life Expectancy and Causes of Death. 2023. https://statbel.fgov.be/en/themes/population/mortality-life-expectancy-and-causes-death.

- ESMO/SIOPE Adolescents and Young Adults Working Group.

- Centraal Bureau voor de Statistiek (CBS). https://www.cbs.nl/nl-nl (accessed 2025-01-27).

- Integraal Kankercentrum Nederlands (IKNL). https://nkr-cijfers.iknl.nl/ (accessed 2025-01-27).

- Institut National de la Statistique et des Etudes Economiques (Insee). https://www.insee.fr/ (accessed 2025-01-27).

- Institut National du Cancer. https://www.e-cancer.fr/ (accessed 2025-01-27).

- DeStatis Statistisches Bundesamt. https://www.destatis.de/EN/Themes/Society-Environment/Population/ (accessed 2025-01-27).

- Zentrum Für Krebsregisterdaten, Robert Koch Institut. https://www.krebsdaten.de/Krebs/ (accessed 2025-01-27).

- Eurostat’s task force, M. and W. papers. Revision of the European Standard Population. 2013. https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/documents/3859598/5926869/KS-RA-13-028-EN.PDF.pdf/e713fa79-1add-44e8-b23d-5e8fa09b3f8f?t=1414782757000.

- Ahmad, O.B.; Boschi Pinto, C.; Lopez, A.D. Age Standardization of Rates: A New WHO Standard; GPE Discussion Paper Series: No 31; 2001; pp. 10–12. [Google Scholar]

- EDERER, F.; AXTELL, L.; CUTLER, S. The Relative Survival Rate: A Statistical Methodology. Natl Cancer Inst Monogr 1961, 6, 101–121. [Google Scholar]

- Joinpoint Regression Program, Version 5.0.2. 2023. https://surveillance.cancer.gov/joinpoint/.

- National Cancer Institute - Surveillance Research Program. Number of Joinpoints—Joinpoint Help System. https://surveillance.cancer.gov/ help/joinpoint/setting-parameters/advanced-tab/number-of-joinpoints (accessed 2024-01-02).

- Li, W.; Liang, H.; Wang, W.; Liu, J.; Liu, X.; Lao, S.; Liang, W.; He, J. Global Cancer Statistics for Adolescents and Young Adults: Population Based Study. Journal of Hematology & Oncology 2024, 17, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Xu, L.; Sun, J.; Song, M.; Wang, L.; Yuan, S.; Zhu, Y.; Wan, Z.; Larsson, S.; Tsilidis, K.; Dunlop, M.; Campbell, H.; Rudan, I.; Song, P.; Theodoratou, E.; Ding, K.; Li, X. Global Trends in Incidence, Death, Burden and Risk Factors of Early-Onset Cancer from 1990 to 2019. BMJ Oncology 2023, 2, e000049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ugai, T.; Sasamoto, N.; Lee, H.-Y.; Ando, M.; Song, M.; Tamimi, R.M.; Kawachi, I.; Campbell, P.T.; Giovannucci, E.L.; Weiderpass, E.; Rebbeck, T.R.; Ogino, S. Is Early-Onset Cancer an Emerging Global Epidemic? Current Evidence and Future Implications. Nature Reviews Clinical Oncology 2022, 19, 656–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toss, A.; Quarello, P.; Mascarin, M.; Banna, G.L.; Zecca, M.; Cinieri, S.; Peccatori, F.A.; Ferrari, A. Cancer Predisposition Genes in Adolescents and Young Adults (AYAs): A Review Paper from the Italian AYA Working Group. Current Oncology Reports 2022, 24, 843–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finkelstein, D.M.; Horick, N.K.; Ramchandani, R.; Boyd, K.L.; Rana, H.Q.; Bychkovsky, B.L. Are Rare Cancer Survivors at Elevated Risk of Subsequent New Cancers? BMC Cancer 2019, 19, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macq, G.; Silversmit, G.; Verdoodt, F.; Van Eycken, E. The Epidemiology of Multiple Primary Cancers in Belgium (2004–2017): Incidence, Proportion, Risk, Stage and Impact on Relative Survival Estimates. BMC Cancer 2023, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Muscat, J.E.; Chinchilli, V.M.; Behura, C.G. Trends in Cancer Incidence and Mortality in US Adolescents and Young Adults, 2016–2021. Cancers 2024, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voeltz, D.; Baginski, K.; Hornberg, C.; Hoyer, A. Trends in Incidence and Mortality of Early-Onset Cancer in Germany between 1999 and 2019. European Journal of Epidemiology 2024, 39, 827–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, W. F.; Pfeiffer, R.M.; Tucker, M.A.; Rosenberg, P.S. Divergent Cancer Pathways for Early-Onset and Late-Onset Cutaneous Malignant Melanoma. Cancer 2009, 115, 4176–4185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, S.; Kim, K.; Moon, S.; Ko, K.-P.; Kim, I.; Lee, J.; Park, S. Indoor Tanning and the Risk of Overall and Early-Onset Melanoma and Non-Melanoma Skin Cancer: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Cancers 2021, 13, 5940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Marmol, V. Prevention and Screening of Melanoma in Europe: 20 Years of the Euromelanoma Campaign. Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology 2022, 36, 5–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stichting Tegen Kanker - Fondation Contre le Cancer. Ondanks preventie neemt huidkanker toe - Malgré la prévention, les cancers de la peau sont en hausse. https://kanker.be/resource/ondanks-preventie-neemt-huidkanker-toe/ - https://cancer.be/ressource/malgre-la-prevention-les-cancers-de-la-peau-sont-en-hausse/ (accessed 2025-02-02).

- LeClair, K.; Bell, K.; Furuya-Kanamori, L.; Doi, S.; Francis, D. Evaluation of Gender Inequity in Thyroid Cancer Diagnosis: Differences by Sex in US Thyroid Cancer Incidence Compared With a Meta-Analysis of Subclinical Thyroid Cancer Rates at Autopsy. JAMA Internal Medicine 2021, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Meer, D.J.; Karim-Kos, H.E.; van der Mark, M.; Aben, K.K.H.; Bijlsma, R.M.; Rijneveld, A.W.; van der Graaf, W.T.A.; Husson, O. Incidence, Survival, and Mortality Trends of Cancers Diagnosed in Adolescents and Young Adults (15-39 Years): A Population-Based Study in The Netherlands 1990-2016. Cancers 2020, 12, 3421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iglesias, M.L.; Schmidt, A.; Ghuzlan, A.A.; Lacroix, L.; Vathaire, F. de; Chevillard, S.; Schlumberger, M. Radiation Exposure and Thyroid Cancer: A Review. Archives of Endocrinology and Metabolism 2017, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massimino, M.; Evans, D.; Podda, M.; Spinelli, C.; Collini, P.; Pizzi, N.; Bleyer, A. Thyroid Cancer in Adolescents and Young Adults. Pediatric Blood & Cancer 2018, 65, e27025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaridze, D.; Maximovitch, D.; Smans, M.; Stilidi, I. Thyroid Cancer Overdiagnosis Revisited. Cancer Epidemiol. 2021, 74, 102014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van den Bruel, A.; Francart, J.; Dubois, C.; Adam, M.; Vlayen, J.; De Schutter, H.; Stordeur, S.; Decallonne, B. Regional Variation in Thyroid Cancer Incidence in Belgium Is Associated With Variation in Thyroid Imaging and Thyroid Disease Management. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism 2013, 98, 4063–4071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levine, O.; Zbuk, K. Colorectal Cancer in Adolescents and Young Adults: Defining a Growing Threat. Pediatric Blood & Cancer 2019, 66, e27941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connell, L.C.; Mota, J.M.; Braghiroli, M.I.; Hoff, P.M. The Rising Incidence of Younger Patients With Colorectal Cancer: Questions About Screening, Biology, and Treatment. Current Treatment Options in Oncology 2017, 18, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frostberg, E.; Rahr, H.B. Clinical Characteristics and a Rising Incidence of Early-Onset Colorectal Cancer in a Nationwide Cohort of 521 Patients Aged 18-40 Years. Cancer Epidemiology 2020, 66, 101704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vuik, F.E.; Nieuwenburg, S.A.; Bardou, M.; Lansdorp-Vogelaar, I.; Dinis-Ribeiro, M.; Bento, M.J.; Zadnik, V.; Pellisé, M.; Esteban, L.; Kaminski, M.F.; Suchanek, S.; Ngo, O.; Májek, O.; Leja, M.; Kuipers, E.J.; Spaander, M.C. Increasing Incidence of Colorectal Cancer in Young Adults in Europe over the Last 25 Years. Gut 2019, 68, 1820–1826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danial, D.; Youssef, E.D.; Maryam, B.M.; Mohammad, A.; Moein, B.M.; Liliane, D. Risk Factors of Young-Onset Colorectal Cancer: Analysis of a Large Population-Based Registry. Canadian Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology 2022, 2022, 3582443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hua, H.; Jiang, Q.; Sun, P.; Xu, X. Risk Factors for Early-Onset Colorectal Cancer: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Frontiers in Oncology 2023, 13, 1132306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricoli, J.; Bleyer, A. Adolescent and Young Adult Cancer Biology. The Cancer Journal 2018, 24, 267–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cervical cancer screening program. https://baarmoederhalskanker.bevolkingsonderzoek.be/en (accessed 2025-02-02).

- Johanne Spanggaard Piltoft, L.C.; Larsen, S. B.; Dalton, S. O.; Johansen, C.; Baker, J. L.; Cederkvist, L.; Andersen, I. Early Life Risk Factors for Testicular Cancer: A Case-Cohort Study Based on the Copenhagen School Health Records Register. Acta Oncologica 2017, 56, 220–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Risco Kollerud, R.; Ruud, E.; Haugnes, H.S.; Cannon-Albright, L.A.; Thoresen, M.; Nafstad, P.; Vlatkovic, L.; Blaasaas, K.G.; Næss, Ø.; Claussen, B. Family History of Cancer and Risk of Paediatric and Young Adult’s Testicular Cancer: A Norwegian Cohort Study. British Journal of Cancer 2019, 120, 1007–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garolla, A.; Vitagliano, A.; Muscianisi, F.; Valente, U.; Ghezzi, M.; Andrisani, A.; Ambrosini, G.; Foresta, C. Role of Viral Infections in Testicular Cancer Etiology: Evidence From a Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Frontiers in Endocrinology 2019, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fénichel, P.; Chevalier, N. Is Testicular Germ Cell Cancer Estrogen Dependent? The Role of Endocrine Disrupting Chemicals. Endocrinology 2019, 160, 2981–2989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hermansen, M.; Hjelmborg, J.; Thinggaard, M.; Znaor, A.; Skakkebæk, N.E.; Lindahl-Jacobsen, R. Smoking and Testicular Cancer: A Danish Nationwide Cohort Study. Cancer Epidemiology 2025, 95, 102746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaddam, S.J.; Chestnut, G.T. Testicle Cancer.; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island (FL), 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Hochberg, J.; Waxman, I.M.; Kelly, K.M.; Morris, E.; Cairo, M.S. Adolescent Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma and Hodgkin Lymphoma: State of the Science. British Journal of Haematology 2009, 144, 24–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brenner, H.; Gondos, A.; Pulte, D. Ongoing Improvement in Long-Term Survival of Patients with Hodgkin Disease at All Ages and Recent Catch-up of Older Patients. Blood 2008, 111, 2977–2983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, J.; Pang, W.S.; Lok, V.; Zhang, L.; Lucero-Prisno, D.E.; Xu, W.; Zheng, Z.-J.; Elcarte, E.; Withers, M.; Wong, M.C.S.; NCD Global Health Research Group, A. of P. R. U. (APRU). Incidence, Mortality, Risk Factors, and Trends for Hodgkin Lymphoma: A Global Data Analysis. Journal of Hematology & Oncology 2022, 15, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, B.L.; Day, C.N.; Hoskin, T.L.; Habermann, E.B.; Boughey, J.C. Adolescents and Young Adults with Breast Cancer Have More Aggressive Disease and Treatment than Patients in Their Forties. Ann Surg Oncol 2019, 26, 3920–3930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, R.H.; Anders, C.K.; Litton, J.K.; Ruddy, K.J.; Bleyer, A. Breast Cancer in Adolescents and Young Adults. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2018, 65, e27397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Saini, S.; Ganguly, N.K. Year-Round Breast Cancer Awareness: Empowering Young Women in the Fight against Breast Cancer. Indian Journal of Medical Research 2023, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotsopoulos, J.; Lubinski, J.; Moller, P.; Lynch, H.T.; Singer, C.F.; Eng, C.; Neuhausen, S.L.; Karlan, B.; Kim-Sing, C.; Huzarski, T.; Gronwald, J.; McCuaig, J.; Senter, L.; Tung, N.; Ghadirian, P.; Eisen, A.; Gilchrist, D.; Blum, J.L.; Zakalik, D.; Pal, T.; Sun, P.; Narod, S.A. Hereditary Breast Cancer Clinical Study Group. Timing of Oral Contraceptive Use and the Risk of Breast Cancer in BRCA1 Mutation Carriers. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2014, 143, 579–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lalloo, F.; Varley, J.; Moran, A.; Ellis, D.; O’dair, L.; Pharoah, P.; Antoniou, A.; Hartley, R.; Shenton, A.; Seal, S.; Bulman, B.; Howell, A.; Evans, D. BRCA1, BRCA2 and TP53 Mutations in Very Early-Onset Breast Cancer with Associated Risks to Relatives. Eur J Cancer 2006, 42, 1143–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trama, A.; Bernasconi, A.; McCabe, M.G.; Guevara, M.; Gatta, G.; Botta, L.; Group, the Rarecare. W; Ries, L.; Bleyer, A. Is the Cancer Survival Improvement in European and American Adolescent and Young Adults Still Lagging behind That in Children? Pediatric Blood & Cancer 2019, 66, e27407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keegan, T.H.M.; Ries, L.A.G.; Barr, R.D.; Geiger, A.M.; Dahlke, D.V.; Pollock, B.H.; Bleyer, W.A.; for the National Cancer Institute Next Steps for Adolescent and Young Adult Oncology Epidemiology Working Group. Comparison of Cancer Survival Trends in the United States of Adolescents and Young Adults with Those in Children and Older Adults. Cancer 2016, 122, 1009–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moke, D.; Tsai, K.-Y.; Hamilton, A.; Hwang, A.; Liu, L.; Freyer, D.; Deapen, D. Emerging Cancer Survival Trends, Disparities, and Priorities in Adolescents and Young Adults: A California Cancer Registry-Based Study. JNCI cancer spectrum 2019, 3, pkz031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).