Submitted:

31 December 2024

Posted:

02 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

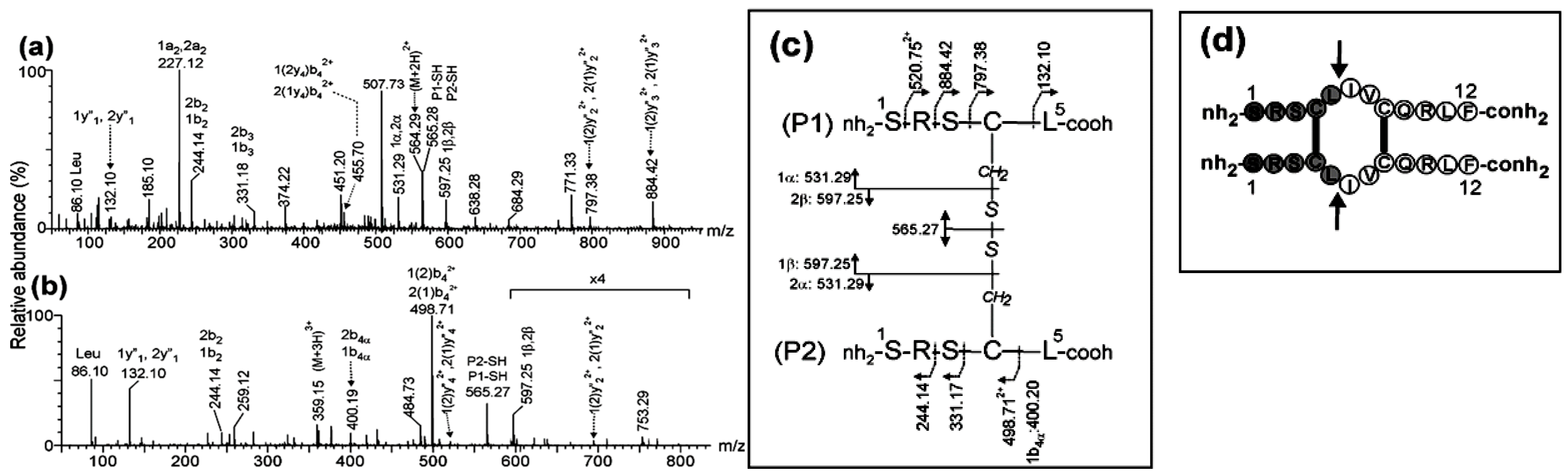

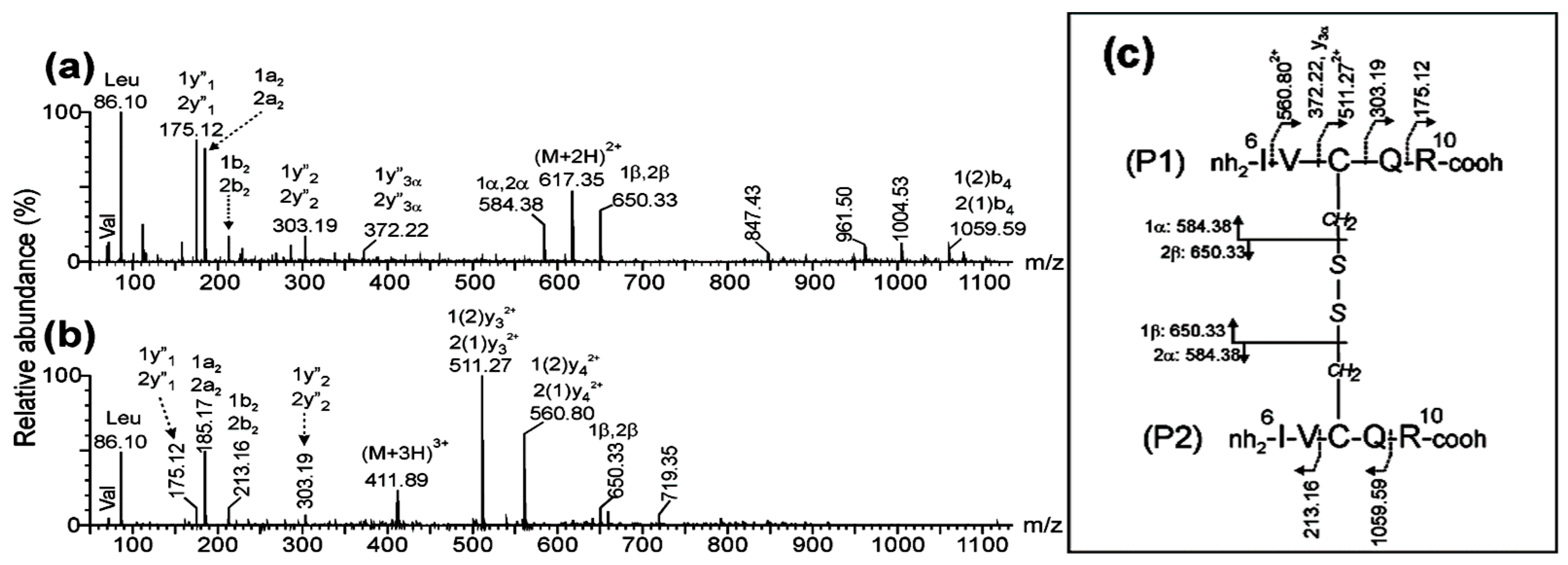

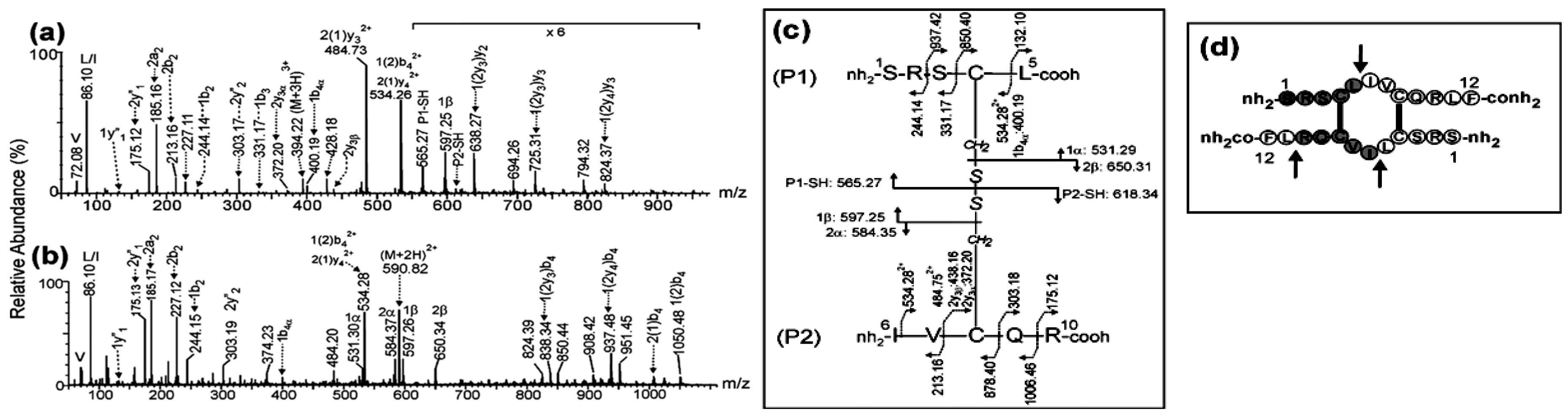

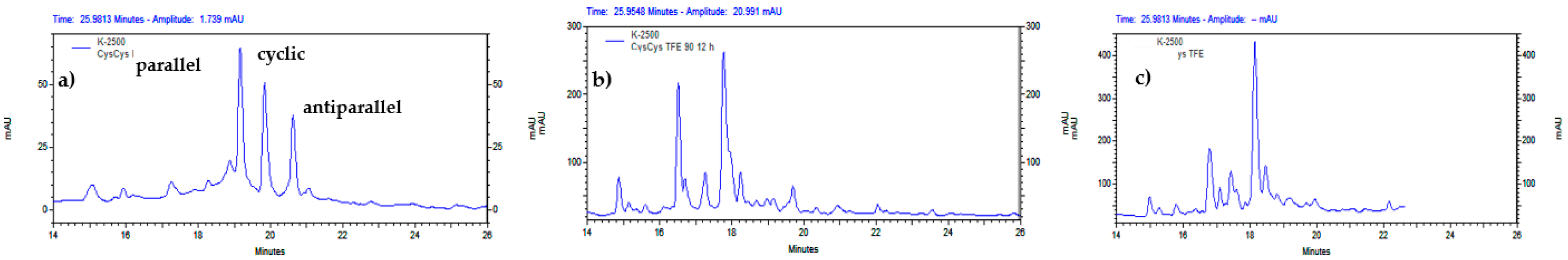

2.1. Differentiating Cyclic Parallel and Antiparallel Dimers of Cm-p5 by Chymotryptic Digestion and ESI-MSMS Analysis

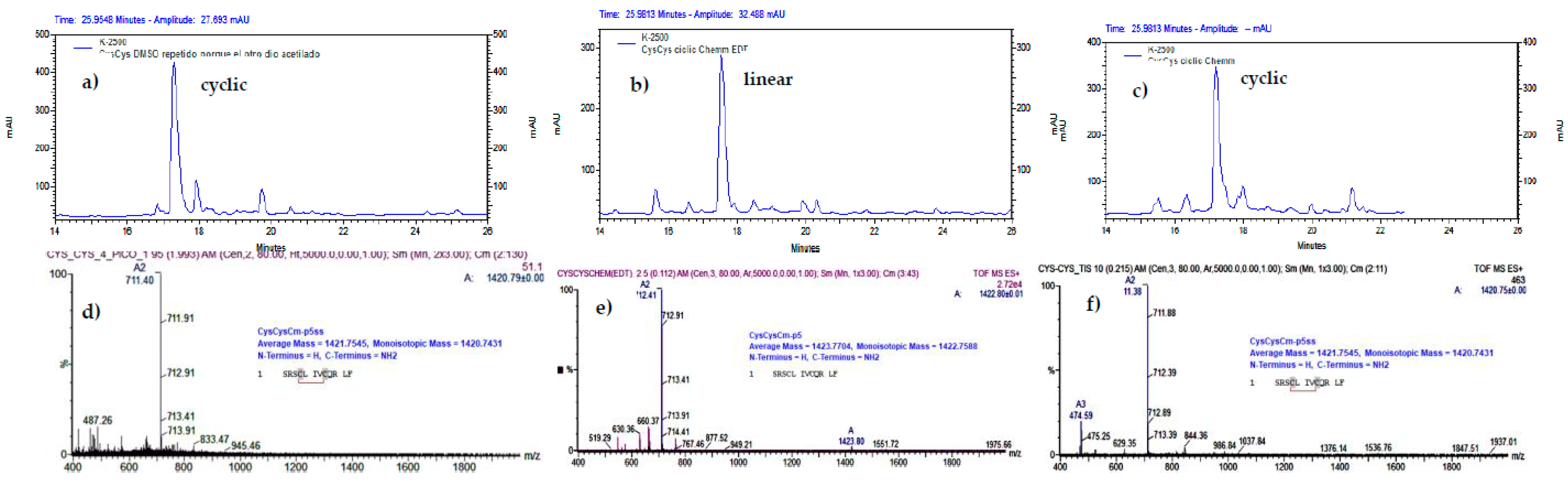

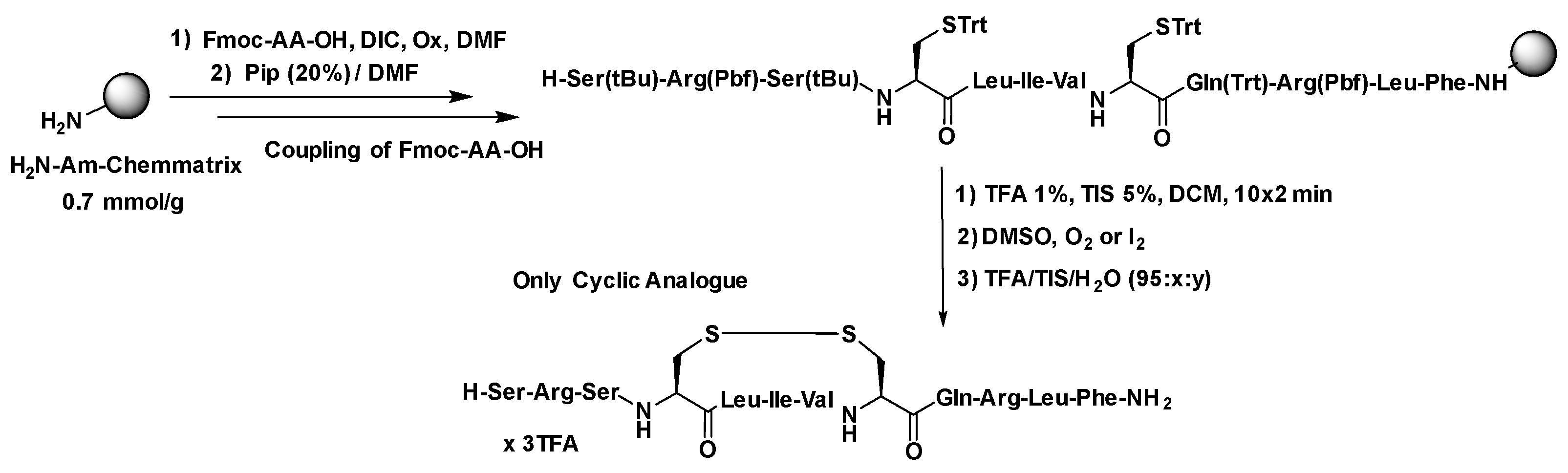

2.2. Selective Synthesis of the Cyclic Monomer CysCysCm-p5ss

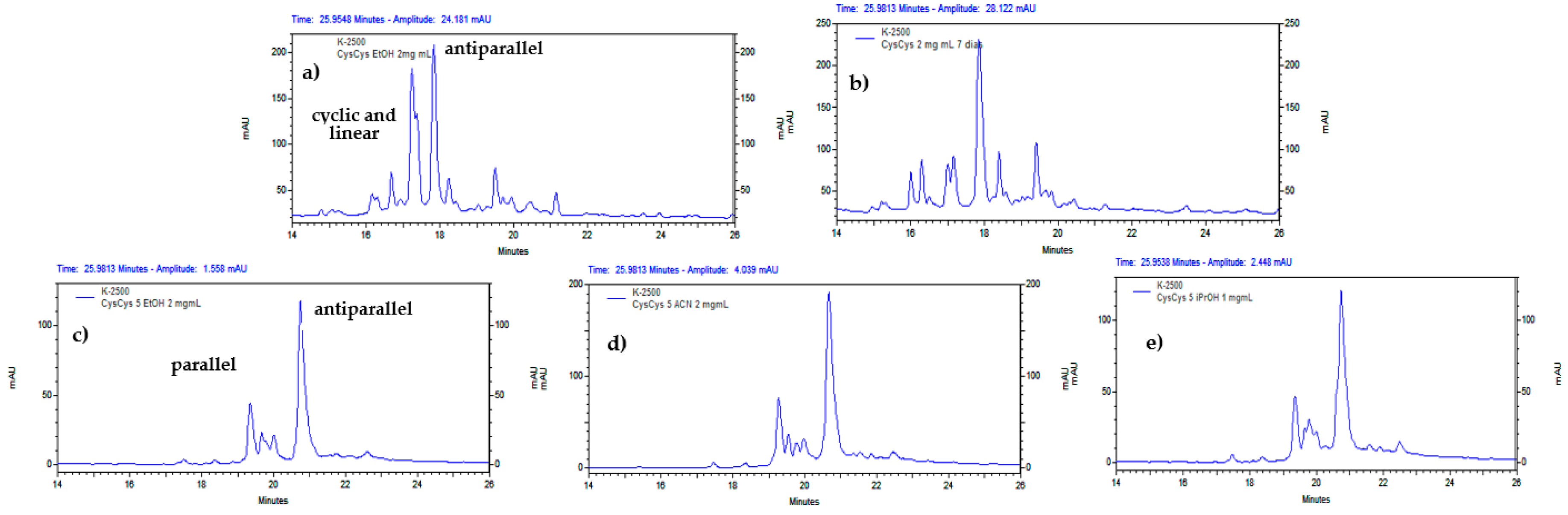

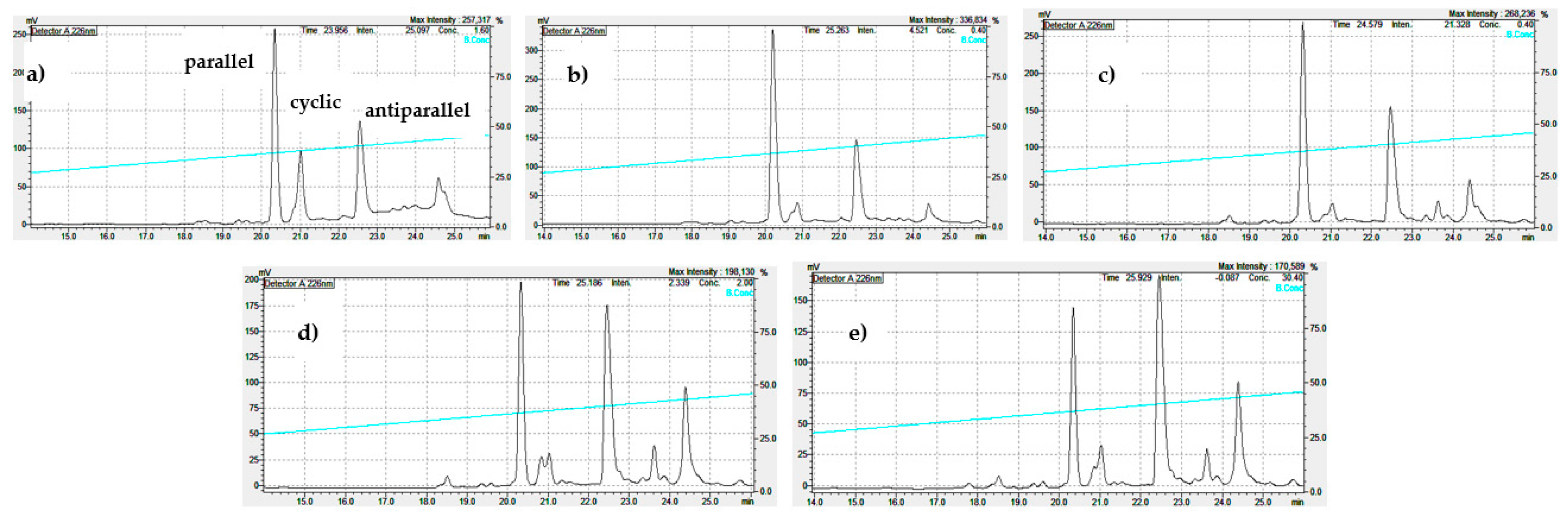

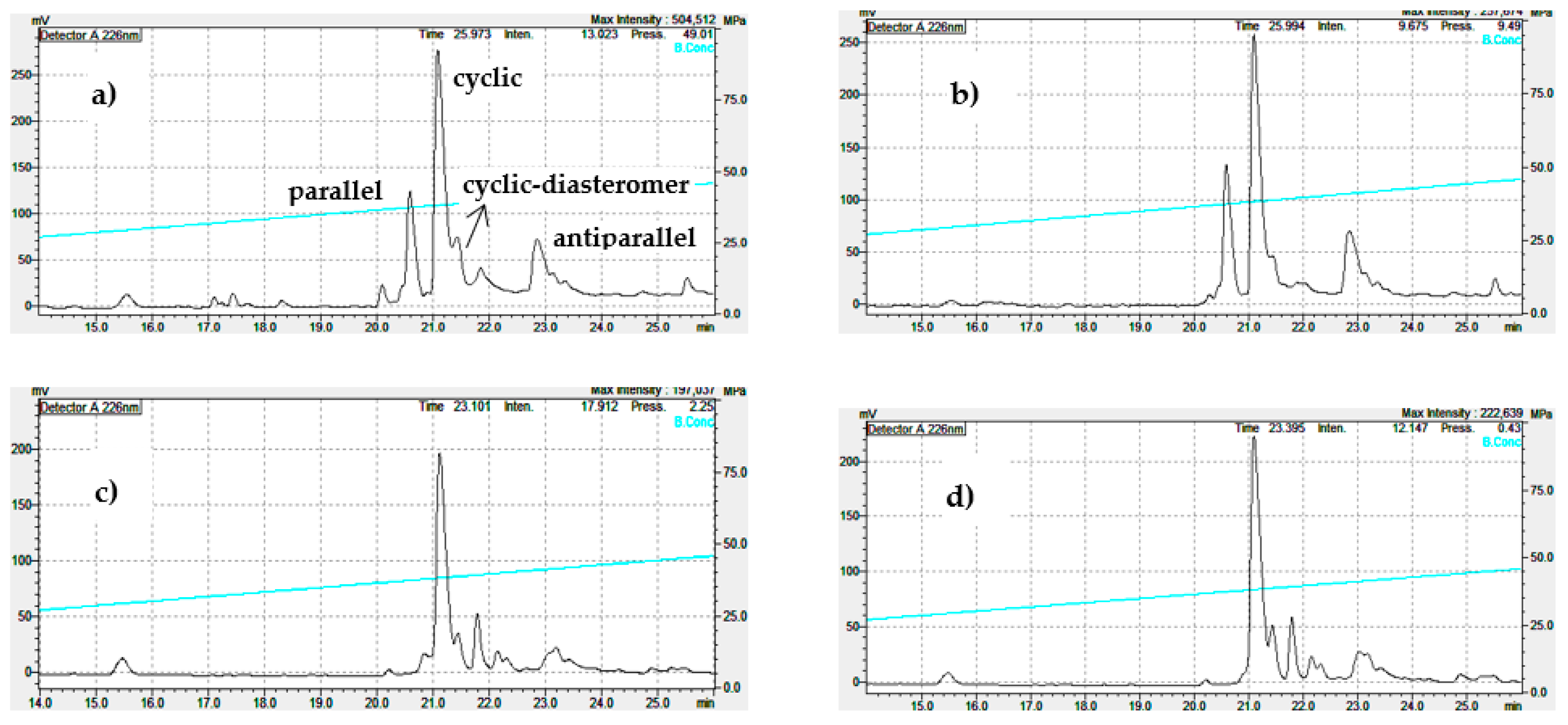

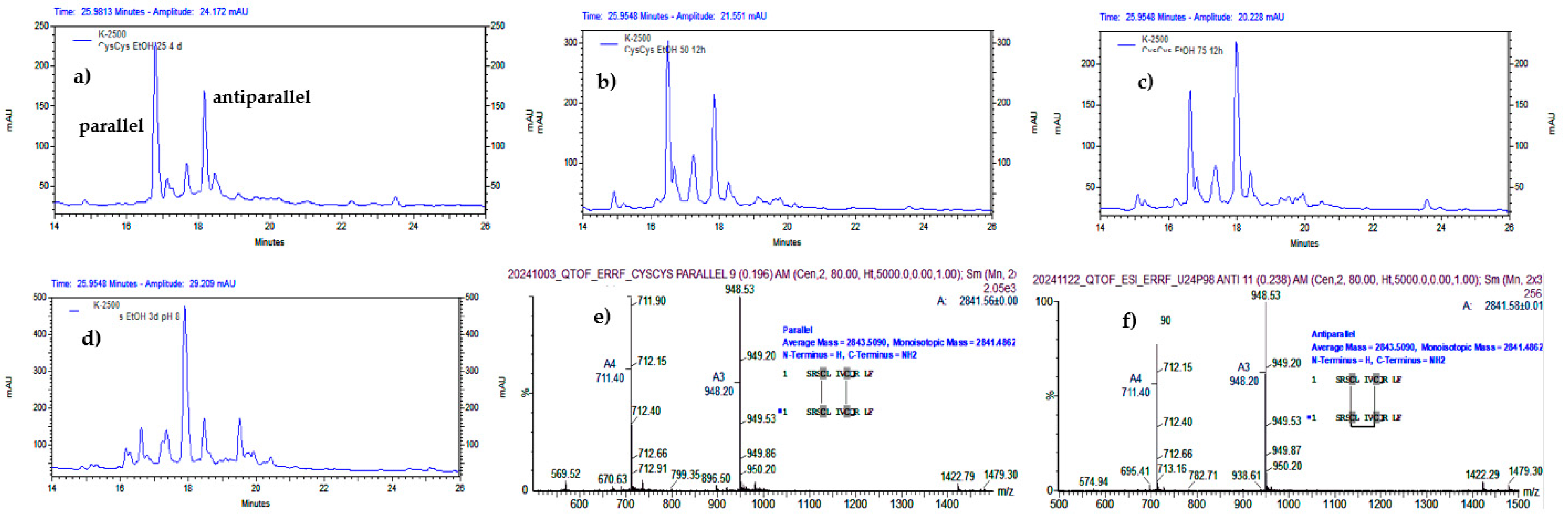

2.3. Selective Synthesis of the Antiparallel Dimer (CysCysCm-p5)2ss-ss

2.4. Selective Synthesis of the Parallel Dimer (CysCysCm-p5)2(ss)2

3. Discussion

3.1. Differentiating Cyclic Parallel and Antiparallel Dimers of Cm-p5 by ESI-MS/MS

3.2. Selective Synthesis of the Cyclic Monomer CysCysCm-p5ss

| Exp. | Chemmatrix | Oxidation | Cleavage mixture | Cyclic | Linear | Racemic | Yield | Dimers |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.7 mmol/g, 0.15 g | 40% DMSO, 3 h | TFA/EDT 2.5%/TIS 1%/H2O 2.5% | 0% | >95% | - | 48% | - |

| 2 | TFA/TIS 2.5%/H2O 2.5% | >95% | - | - | 34% | - | ||

| 3 | 0.41 mmol/g, 0.1 g | 40% DMSO, 6 h | TFA/TIS 2.5%/H2O 2.5% | 10% | >80% | - | 45% | - |

| 4 | 50% DMSO, 12 h | 25% | >70% | - | 47% | |||

| 5 | 0.49 mmol/g, 0.2 g | 35% DMSO, 3 h | TFA/TIS 2%/H2O 2% | 0% | >95% | 35% | ||

| 6 | 0.41 mmol/g | 35% DMSO, 3 h | TFA 10% | >98% | - | - | - | - |

| 7 | I2/DMF-Trt, 30 min | |||||||

| 8 | O2, 6 h | |||||||

| 9 | 0.41 mmol/g, 0.2 g | 35% DMSO, 3 h | TFA/TIS 1%/H2O 3.5% | 25% | 75% | 43% | - | |

| TFA/TIS 1%/H2O 1% | 50% | 50% | 50% | - | ||||

| 10 | 0.41 mmol/g, 0.1 g | 35% DMSO, 3 h | TFA/TIS 1% | 68% | 27% | 35% | - | |

| 11 | I2/DMF-Trt, 30 min | 80% | - | 10% | 32% | - | ||

| 12 | O2, 6 h | 71% | 25% | 37% | - | |||

| 13 | 0.2 mmol/g, 0.1 g | I2/DMF, 30 min | 70% | - | 5% | |||

| 14 | 40% DMSO, 3 h | 61% | 37% | - | - | - | ||

| 15 | TFA/PhSiH3 1% | 48% | 47% | |||||

| MBHA | ||||||||

| 16 | 0.46 mmol/g, 0.2 g | I2/DMF, 30 min | TFA/TIS 2%/H2O 2% | 43% | - | 9.7% | 62% | 27% |

| 17 | 1.11 mmol/g, 0.13 g | I2/DMF, 30 min | 41% | - | 10% | 32% | 34% | |

| 18 | 1.11 mmol/g, 0.17 g | 60% DMSO, 3 h | TFA/TIS 1.5%/H2O 1.5% | 28% | 43% | 1.8% | 57% | 22% |

| 19 | 1.35 mmol/g, 0.15 g | I2/THF, 30 min | 57% | - | 9.8% | 30% | 6.7% | |

| 20 | 1.35 mmol/g, 0.15 g | I2/DMF, 30 min | 56% | - | 7.6% | 26% | 9% |

3.3. Selective Synthesis of the Dimers

| Exp. | Solvent mixture | Time | Parallel | Acyclic | Cyclic | Antiparallel |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CysCysCm-p5 at 0.5 mg/ml | ||||||

| 1 | ACN 50% | 30% | - | - | 40% | |

| 2 | MeOH 50% | 40% | 10% | 10% | 25% | |

| 3 | H2O | 40% | - | 25% | 10% | |

| 4 | EtOH 5% | 60% | - | - | 39% | |

| 5 | EtOH 25% | 67% | - | - | 32% | |

| 6 | EtOH 50% | 57% | - | - | 43% | |

| 7 | EtOH 75% | 44% | - | - | 55% | |

| 8 | EtOH 90% | 36% | - | - | 64% | |

| CysCysCm-p5 at 1 mg/ml | ||||||

| 10 | EtOH 22% | 45% | - | 10% | 31% | |

| 11 | EtOH 45% | 41% | - | 12% | 28% | |

| 12 | EtOH 67% | 28% | - | 13% | 45% | |

| 13 | EtOH 81% | 12% | 4% | 11% | 51% | |

| 14 | DMF 5% | 40% | - | 10% | 35% | |

| 15 | TFE 5% | 6 h | 30% | 30% | 10% | 20% |

| 16 | TFE 5% | 12 h | 50% | 5% | 10% | 20% |

| 17 | TFE 90% | 30% | - | 10% | 50% | |

| CysCysCm-p5 at 2 mg/ml | ||||||

| 18 | EtOH 90% | 8% | 5% | 7% | 68% | |

| 19 | EtOH 5% | 10% | 5% | 5% | 73% | |

| 20 | ACN 5% | 10% | 5% | 5% | 71% | |

| 21 | iPrOH 5% | 10% | 5% | 5% | 70% | |

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Peptide Characterization

4.1.1. Analytical RP-HPLC

4.1.2. ESI-MS

4.1.3. Proteolytic Digestion and Desalting of Chymotryptic Peptides

4.2. Peptide Synthesis

4.2.1. Peptide Cleavage

4.2.2. Two-Stage Procedure for Detachment/Deprotection of Rink Amide Resin

4.2.3. Liquid Phase Peptide Cyclization

4.2.4. On Resin Peptide Cyclization with DMSO, O2 or I2

4.2.5. Concentrated Iodine Oxidation of Acm Containing Peptide

4.2.5. Low Scale Experiments with EtOH

4.2.6. Dimerization Scale-Up to Afford the Antiparallel Dimer

4.2.7. Dimerization Scale-Up to Afford Parallel Dimer

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lei, J.; Sun, L.; Huang, S.; Zhu, C.; Li, P.; He, J.; Mackey, V.; Coy, D.H.; He, Q. The antimicrobial peptides and their potential clinical applications. Am. J. Translat. Res. 2019, 11, 3919–3931. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kościuczuk, E.M.; Lisowski, P.; Jarczak, J.; Strzałkowska, N.; Jóźwik, A.; Horbańczuk, J.; Krzyżewski, J.; Zwierzchowski, L.; E., B. Cathelicidins: family of antimicrobial peptides. A review. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2012, 39, 10957–10970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.J.; Gallo, R.L. Antimicrobial peptides. Curr. Biol. 2016, 26, R14–R19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bechinger, B.; Gorr, S.U. Antimicrobial Peptides: Mechanisms of Action and Resistance. J. Dent. Res. 2017, 96, 254–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huan, Y.; Kong, Q.; Mou, H.; Yi, H. Antimicrobial Peptides: Classification, Design, Application and Research Progress in Multiple Fields. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 582779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otvos, L.; Wade, J.D. Current challenges in peptide-based drug discovery. Front. Chem. 2014, 6, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, J.; Gilon, C.; Hoffman, A.; Kessler, H. N-Methylation of Peptides: A New Perspective in Medicinal Chemistry. Acc. Chem. Res. 2008, 41, 1331–1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meanwell, N.A. The Influence of Bioisosteres in Drug Design: Tactical Applications to Address Developability Problems. In Tactics in Contemporary Drug Design. Springer: Berlin, Heidelberg 2013, 9, 283–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, X.; Jin, K. A gold mine for drug discovery: Strategies to develop cyclic peptides into therapies. Med. Res. Rev. 2019, 40, 753–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reguera, L.; Rivera, D.G. Multicomponent Reaction Toolbox for Peptide Macrocyclization and Stapling. Chem. Rev. 2019, 119, 9836–9860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera, D.G.; Ojeda-Carralero, G.M.; Reguera, L.; Van der Eycken, E.V. Peptide macrocyclization by transition metal catalysis. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2020, 49, 2039–2059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- White, C.J.; Yudin, A.K. Contemporary strategies for peptide macrocyclization. Nat. Chem. 2011, 3, 509–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chow, H.Y.; Zhang, Y.; Matheson, E.; Li, X. Ligation Technologies for the Synthesis of Cyclic Peptides. Chem. Rev. 2019, 119, 9971–10001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shinbara, K.; Liu, W.; van Neer, R.H.P.; Katoh, T.; Suga, H. Methodologies for Backbone Macrocyclic Peptide Synthesis Compatible With Screening Technologies. Front. Chem 2020, 8, 447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gang, D.; Kim, D.W.; Park, H.S. Cyclic Peptides: Promising Scaffolds for Biopharmaceuticals. Genes 2018, 9, 557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoo, K.K.; Norton, R.S.; Hughes, A.B. Role of Disulfide Bond in Peptide and Protein Conformation. In Amino Acids, Peptides and Proteins in Organic Chemistry: Analysis and Function of Amino Acids and Peptides. Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA 2011, 5, 395–417. [Google Scholar]

- Góngora-Benítez, M.; Tulla-Puche, J.; Albericio, F. Multifaceted Roles of Disulfide Bonds. Peptides as Therapeutics. Chem. Rev. 2014, 114, 901–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Abarrategui, C.; McBeth, C.; Zhen-Yu, J.S.; Heffron, G.; García, M.; Alba-Menéndez, A.; Migliolo, L.; Reyes-Acosta, O.; Campos-Dias, S.; Brandt, W.; Porzel, A.; Wessjohann, L.; Starnbach, M.; Franco, O.L.; Otero-González, A.J. Cm-p5: an antifungal hydrophilic peptide derived from the coastal mollusk Cenchritis muricatus (Gastropoda: Littorinidae). FASEB Journal 2015, 29, 3315–3325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales-Vicente, F.E.; González-García, M.; Díaz Pico, E.; Moreno-Castillo, E.; Garay, H.E.; Rosi, P.E.; Jimenez, A.M.; Campos-Delgado, J.A.; Rivera, D.G.; Chinea, G.; Pietro, R.C.L.R.; Stenger, S.; Spellerberg, B.; Kubiczek, D.; Bodenberger, N.; Dietz, S.; Rosenau, F.; Paixao, M.E.; Standker, L.; Otero-González, A.J. Design of a Helical-Stabilized, Cyclic, and Nontoxic Analogue of the Peptide Cm-p5 with Improved Antifungal Activity. ACS Omega 2019, 4, 19081–19095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Garcia, M.; Morales-Vicente, F.; Diáz-Pico, E.; Garay, H.; Rivera, D.G.; Grieshober, M.; Olari, L.R.; Grob, R.; Conzelmann, C.; Kruger, F.; Zech, F.; Prelli, C.B.; Muller, J.A.; Zelikin, A.; Raber, H.; Kubiczek, D.; Rosenau, F.; Munch, J.; Stenger, S.; Spellerberg, B.; Franco, O.L.; Rodriguez Alfonso, A.A.; Standker, L.; Otero-González, A.J. Antimicrobial activity of cyclic-monomeric and dimeric derivatives of the snail-derived peptide Cm-p5 against viral and multidrug-resistant bacterial strains. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubiczek, D.; Raber, H.; Gonzalez-García, M.; Morales-Vicente, F.; Staendker, L.; Otero-Gonzalez, A.J.; Rosenau, F. Derivates of the Antifungal Peptide Cm-p5 Inhibit Development of Candida auris Biofilms In Vitro. Antibiotics 2020, 9, 363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garay, H.; Espinosa, L.A.; Perera, Y.; Sánchez, A.; Diago, D.; Perea, S.E.; Besada, V.; Reyes, O.; González, L.J. Characterization of low-abundance species in the active pharmaceutical ingredient of CIGB-300: A clinical-grade anticancer synthetic peptide. J. Pep. Sci. 2018, 24, e3081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Hansen, L.; Badalassi, F. Investigation of On-Resin Disulfide Formation for Large-Scale Manufacturing of Cyclic Peptides: A Case Study. Org. Process Res. Dev. 2020, 24, 1281–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Postma, T.M.; Albericio, F. Disulfide Formation Strategies in Peptide Synthesis. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2014, 3519–3530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mormann, M.; Eble, J.; Schwoppe, C.; Mesters, R.M.; Berdel, W.E.; Peter-Katalinic, J.; Pohlentz, G. Fragmentation of intra-peptide disulfide bonds of proteolytic peptides by nanoESI collision induced dissociation. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2008, 392, 831–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poole, L.B. The basics of thiols and cysteines in redox biology and chemistry. Free Radical Biology and Medicine 2014, 80, 148–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harriss, M.G.; Milne, J.B. The trifluoracetic acid solvent system. Part III. The acid, HB(OOCCF3)4 and the solvent autoprotolysis constant. Can. J. Chem. 1971, 49, 3612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabodevilla, J.F.; Odriozola, L.; Santiago, E.; Martínez-Irujo, J.J. Factors affecting the dimerization of the p66 form of HIV-1 reverse transcriptase. Eur. J. Biochemistry 2001, 268, 1163–1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodríguez, A.P.; Morejón, M.C.; Rivera, D.G.; Wessjohann, L.A. Peptide macrocyclization assisted by traceless turn inducers derived from Ugi peptide ligation with cleavable and resin-linked amines. Org. Lett. 2017, 19, 4022–4025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuncer, S.; Gurbanov, R.; Sheraj, I.; Solel, E.; Esenturk, O.; Banerjee, S. Low dose dimethyl sulfoxide driven gross molecular changes have the potential to interfere with various cellular processes. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).