1. Introduction

O-linked glycans are a post-translational modification of peptides conserved in all organisms, and have huge structural diversity, with each characteristic core structure nearby peptide linkage being highly conserved during the course of biological evolution.[

1]

O-linked glycans exist primarily in the form of glycosidic bonds to the hydroxyl groups of serine/threonine, and in the animal kingdom, mucin-type glycans having α-linked N-acetylgalactosamine (GalNAc) residue on serine/threonine are involved in most of the life event, including differentiation, growth, immunity, and symbiosis.[

2]

Cyclic peptides are molecules in which the peptide chains bond intramolecularly at separate positions to form a macrocyclic structure. The topological control of conformation and functional groups associated with cyclization allows remarkable physiological activity and physical properties to be achieved with a small number of amino acids.[

3] Cyclic peptide drugs, including physiologically active cyclic peptides discovered in nature, have been vigorously developed and approved.[

4]

With the discovery of soft ionization methods, mass spectrometry has become a major technique for the exploration and structural analysis of various biomolecules.[

5,

6] Mass spectrometry is actively used to explore biologically active peptides and their post-translational modifications due to its rapidity, comprehensiveness, resolution, and high sensitivity.[

7,

8] MS/MS fragmentation techniques are effective for peptide sequencing.[

9] In the case of cyclic peptides, the molecular weight do not change after the first cleavage of the peptide bond. Different analytical methods and characteristics from those used for linear peptides are required to understand the characteristics of the cyclic peptides.[

10]

Matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS) is a soft ionization method widely used for mass spectrometry of biomolecules.[

6] To analyze the internal structure of a target molecule using MALDI-TOF MS, fragmentation by post-source decay (PSD) after precursor ion selection, called TOF/TOF, is mainly used.[

11] In addition to the fragmentation pattern indicating the peptide sequence, minor fragmentation that was ignored in linear peptides becomes prominent during this PSD process for cyclic peptides, providing hints for exploring the internal structure.[

9] It has been reported that in the PSD of cyclic peptides, carbon and nitrogen involved in the peptide chain are desorbed as carbon monoxide and ammonia, respectively.[

10,

12] However, compared to linear peptides, there are limited reports on the fragmentation behavior of cyclic peptides. In particular, detailed studies on the fragmentation behavior of cyclic peptides with post-translational modifications such as cyclic glycopeptides are rare.[

13]

We systematically research on the synthesis and analysis of glycopeptides.[

14,

15,

16,

17,

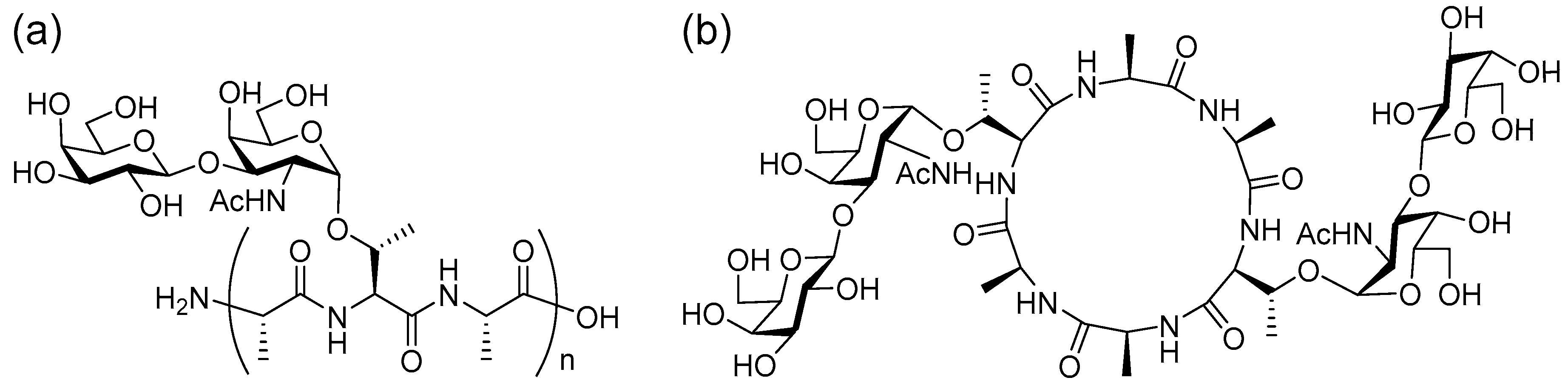

18] In the process, we found that cyclic glycopeptides replicated during the synthesis of linear antifreeze glycoproteins (AFGPs;

Figure 1a) in nature[

18,

19] have antifreeze activity.[

20] We also found that the glycan moiety of the cyclic antifreeze glycoproteins (

Figure 1b) can be directly observed by in-source decay (ISD) MALDI-TOF MS with modified matrix for glycan-selective ionization.[

21] In this study, we report the characteristic PSD patterns in MALDI-TOF/TOF MS analysis of cyclic glycopeptides and their peptide backbone.

2. Results and Discussion

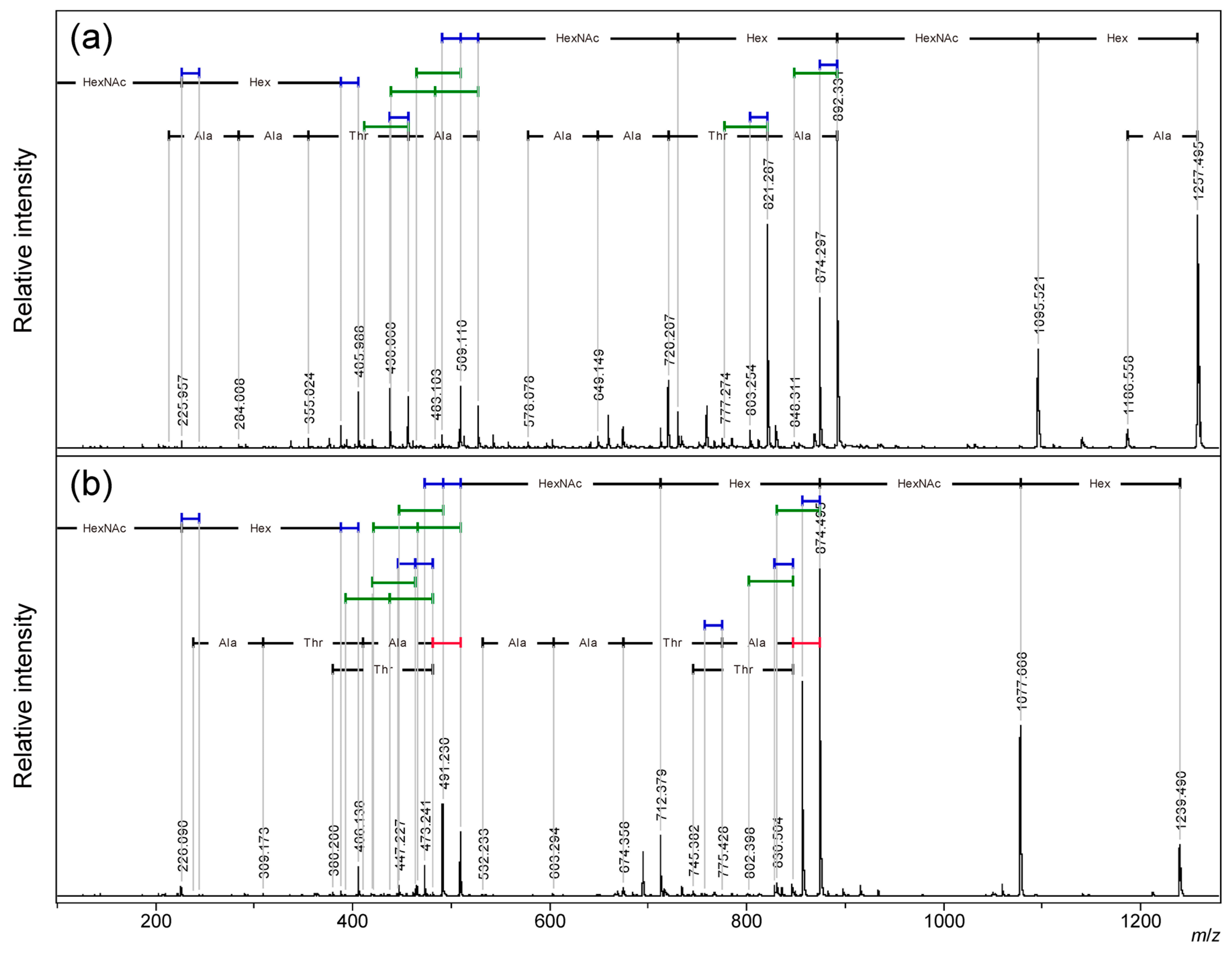

2.1. Comparative MALDI-TOF/TOF MS Analysis of Linear and Cyclic AFGP

In MALDI-TOF MS, sodium adduct ions were mainly observed in both linear and cyclic AFGP.[

18,

20] A comparative analysis was performed using TOF/TOF on the sodium adduct precursor ions [M + Na]

+ of the two-repeat (n=2) type linear and cyclic AFGP using sodium doped benzylhydroxylamine/2,5-dihydroxybenzoate salt (BOA/DHB/Na) matrix.[

21] (

Figure 2, S1:

m/

z 600-910, and S2:

m/

z 300-540)

At small

m/

z region, sodium adducts ions of glycan fragments found as two pairs of 18 Da neutral loss (blue bar in Figures)

m/

z 226 and 244 for N-acetylgalctosamine residue (HexNAc) and

m/

z 388 and 406 for additional galactose residue (Hex), as we reported as ISD MALDI-TOF MS analysis of synthetic AFGP mixtures and intact mucins.[

22] At the larger

m/

z region, sequential neutral loss of the two pairs of disaccharide branches from the precursor ion signal gave the sodium adduct ion of the core peptide with a free hydroxyl group of the threonine side chain and its dehydro-form as the main fragment ion signals. Following the loss of the glycan branches, sequential neutral losses of peptide skeleton were observed from linear AFGP.(

Figure 2a) A 28 Da neutral losses (red bar in Figures) were observed before the amino acid sequence signals only in cyclic AFGPs.(

Figure 2b) This could be due to the loss of CO from the oxazoline structure during the ring-opening reaction, preceding the loss of the amino acid. [

23,

24,

25] From both precursor linear and cyclic AFGPs, 18 Da and 44 Da (green bar in Figures) neutral loss fragments were observed after the neutral loss of glycans. Of these neutral losses, the 18 Da loss corresponding to the dehydro-form was stronger than the 44 Da loss, and stronger signals were observed from cyclic AFGP than the linear form. Although cyclic AFGP has no C-terminal or acidic side chain to produce CO

2, the neutral loss of 44 Da might be a fragment of different compositions. These "small" neutral losses pattern could be useful signals to probing detailed internal structural information of the target molecule.

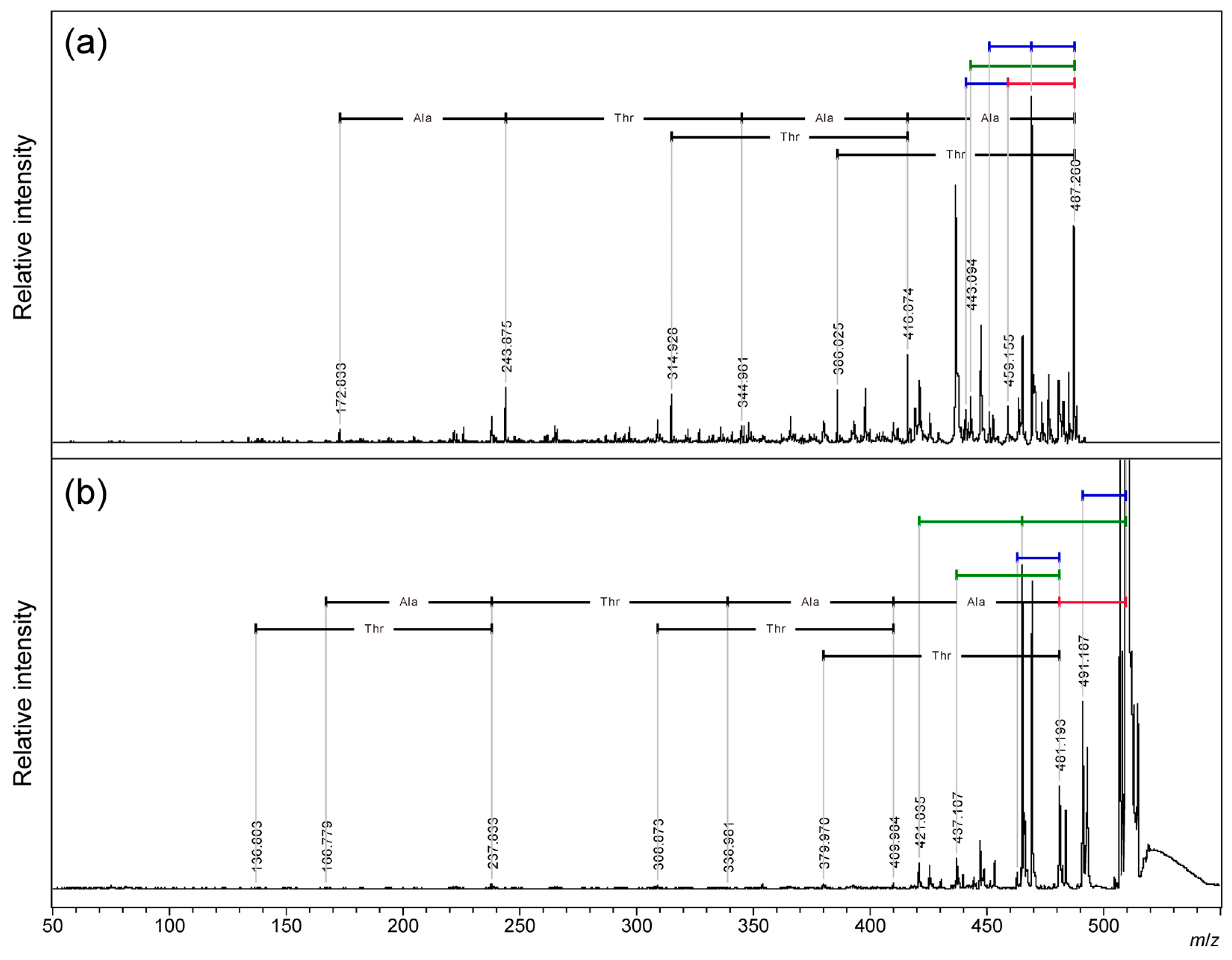

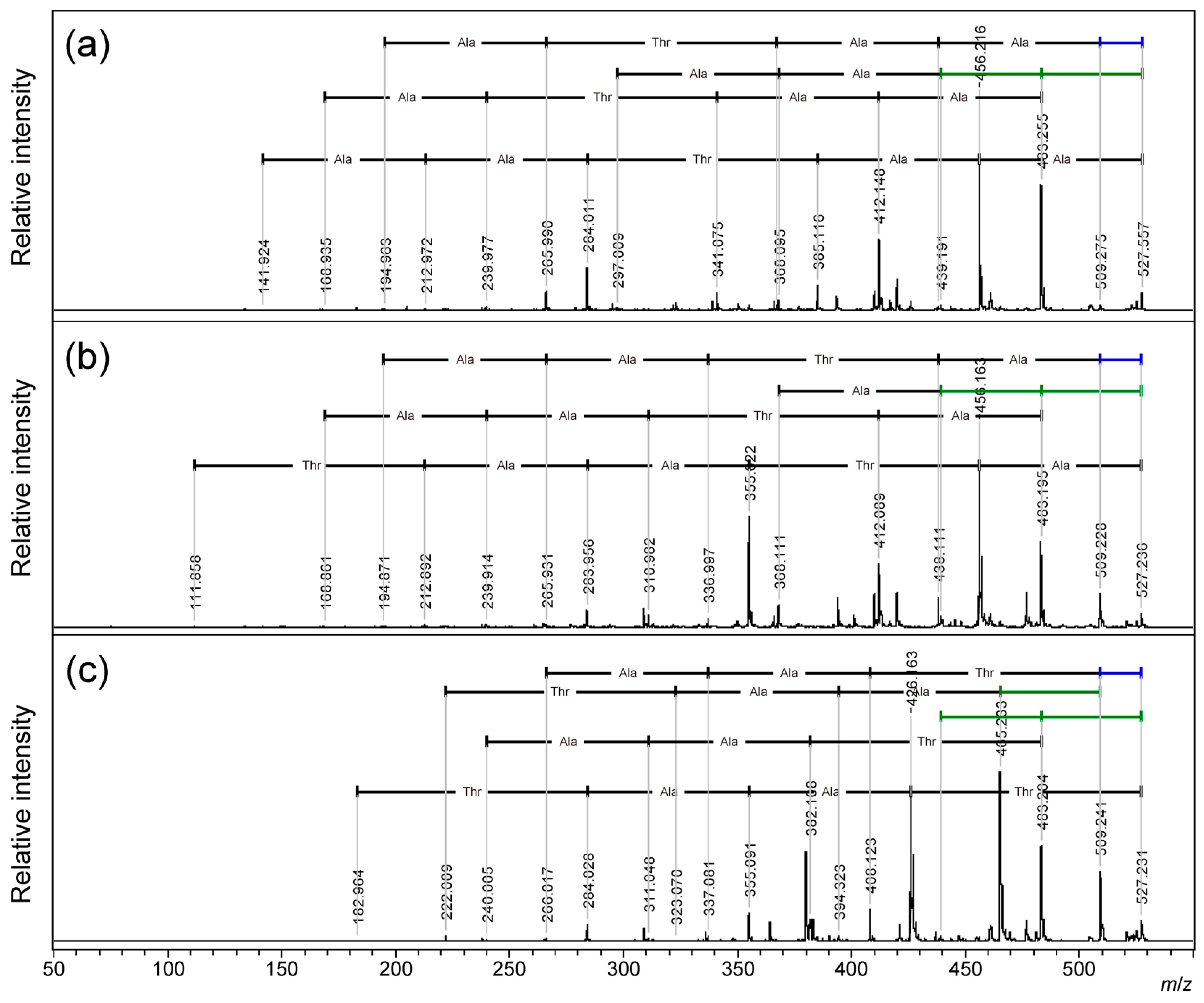

2.2. MALDI-TOF/TOF MS Analysis of Core Cyclic Peptide of Cyclic AFGP

To obtain detailed data on the PSD pattern of the non-sequencing small fragments, the skeleton peptide of cyclic AFGP [

26] was analyzed by MALDI-TOF/TOF MS from both proton and sodium adduct precursor ions. (

Figure 3 and

Figure S3:

m/

z 300-520;

Tables S3 and S4) Sequential neutral losses of amino acid residues from the proton adduct precursor ion were observed for both alanine and threonine residues. (

Figure 3a) From the sodium adduct ion of the cyclic peptide, sequential amino acid losses were observed after a 28 Da neutral loss from the precursor ion. For both precursor ions, losses of 18 Da or 44 Da were observed up to twice in total, independent of the 28 Da loss. The signal of the neutral loss of 18 Da was predominant from the proton adduct ion of the cyclic peptide, and the signals of the 44 Da loss were predominant from the sodium adduct ion. These signal patterns indicate that 18 Da and 44 Da neutral losses occur at the threonine side chain.

Consecutive neutral losses of H

2O and C

2H

4O (Exact Mass: 44.03) have been reported for N-terminal threonine-threonine- and threonine-serine-containing peptides in the PSD of proton adduct ions. [28] In 2015, Wang et al. reported PSD for sodium adduct ion of threonine-containing peptide gives characteristic neutral loss of 44 Da.[29] Our observation of 18 Da and 44 Da losses from cyclic AFGP and its skeleton peptide seems identical to these reports. However, both previous studies clearly showed the importance of the free N-terminus, and the intensity of the 44 Da neutral loss signal decreased significantly depending on the distance from the free N-terminus. No example of cyclic peptide. Therefore, we compared the PSD fragmentation patterns of the three types of linear peptide skeletons of two-repeat AFGP, ATAATA, TAATAA, and AATAAT by MALDI-TOF/TOF MS analysis of proton and sodium adduct precursor ions. (

Figure 4,

Figure 5 and

Figure S4:

m/

z 315-510, and S5:

m/

z 340-535) For proton adduct precursor ion, only TAATAA, having an N-terminal threonine residue gives a 44 Da neutral loss signal as the dominant fragmentation. (

Figure 4a;

Table S5) Proton adduct precursor ion of ATAATA and AATAAT peptides gave 18 Da neutral loss predominantly. (

Figure 4b,

Table S6,

Figure 4c, and

Table S7). Consecutive neutral losses of 18 and 44 Da were not observed. For all sequences, both b-ions and y-ions yielded the correct sequences from both terminals. In the case of linear peptides, the first neutral loss of 18 Da might cause loss of C-terminal dehydration to give b-ions, and further 18 Da losses might cause dehydration of the threonine side chain. The c-ions of the C-terminal threonine at

m/

z 386 (

Figure 4c) assist this PSD mechanism.

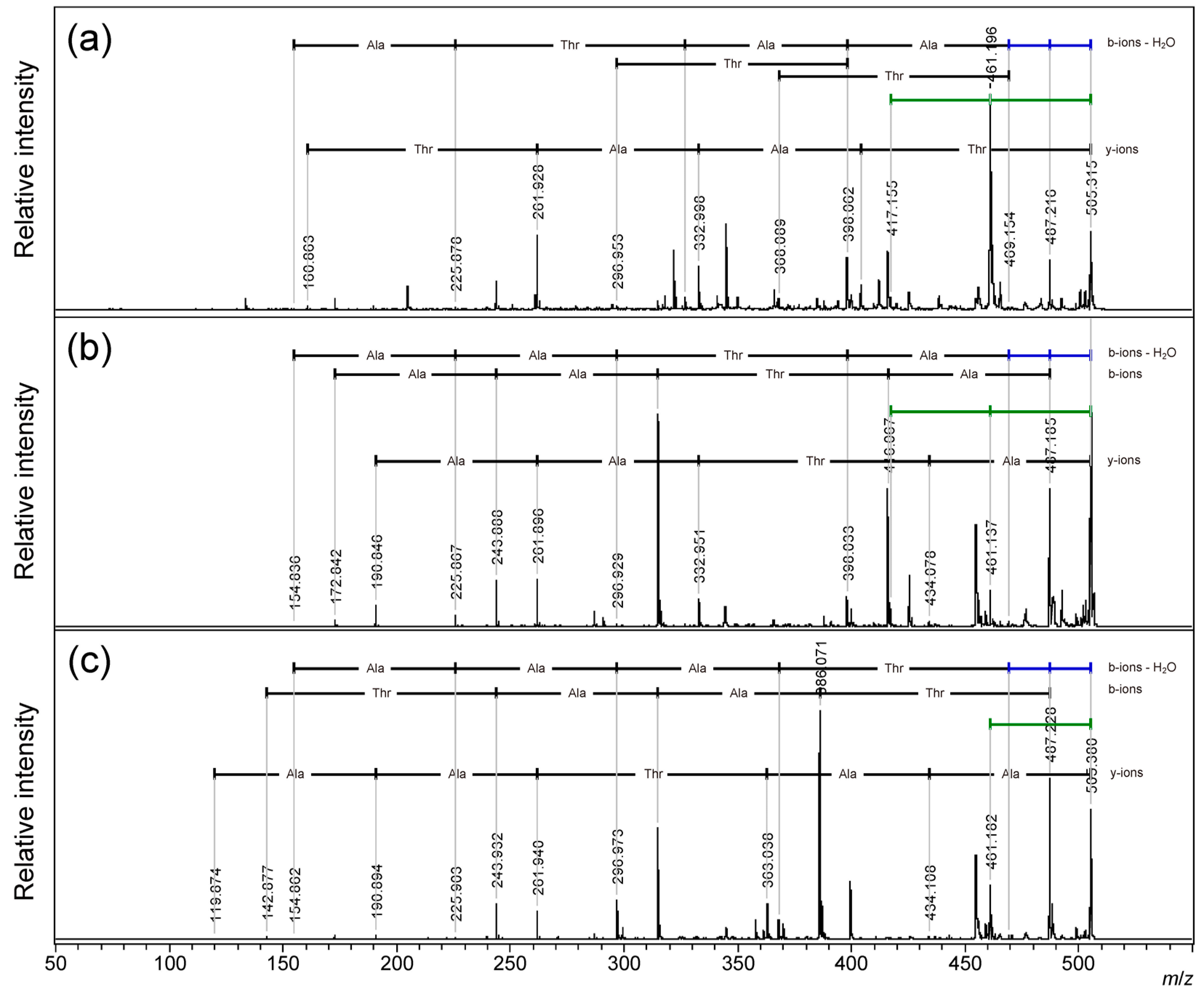

For sodium adduct precursor ions of the linear peptides, all peptides gave a signal of 44 Da neutral loss from the precursor ion as a major fragment signal, and b-ions gave correct sequences; however, the y-ion-like fragment gave the sequence from the C-terminus. (

Figure 5, S5;

Table S8–S10) As Wang et al. reported, [b + Na + OH]

+ ions generated to give the sequence from C-termina.[29] Consecutive neutral loss of the 44 Da pair was also observed for all peptides, although the secondary signals were fainted in strength. In comparison with the first b-ion signals, the presence of the sequence from the C-terminal and no sequence information of the N-terminal were observed for the sodium adduct precursor ions. The N-terminal threonine residue might have slightly strength the 44 Da loss signal. (

Figure 5a) No consecutive neutral losses of 18 Da pair were observed. All 18 Da neutral losses were b-ion-related neutral losses arising from the C-terminal carboxylate. This indicates 18 Da loss was not from the threonine side chain. In contrast to previous reports,[28,29] only the AATAAT sequence with a C-terminal threonine resulted in consecutive neutral losses of 18 Da and 44 Da, although the 18 Da loss might cause the C-terminal carboxylate to give b-ions, and the losses could be caused at the same threonine residue. (

Figure 5c)

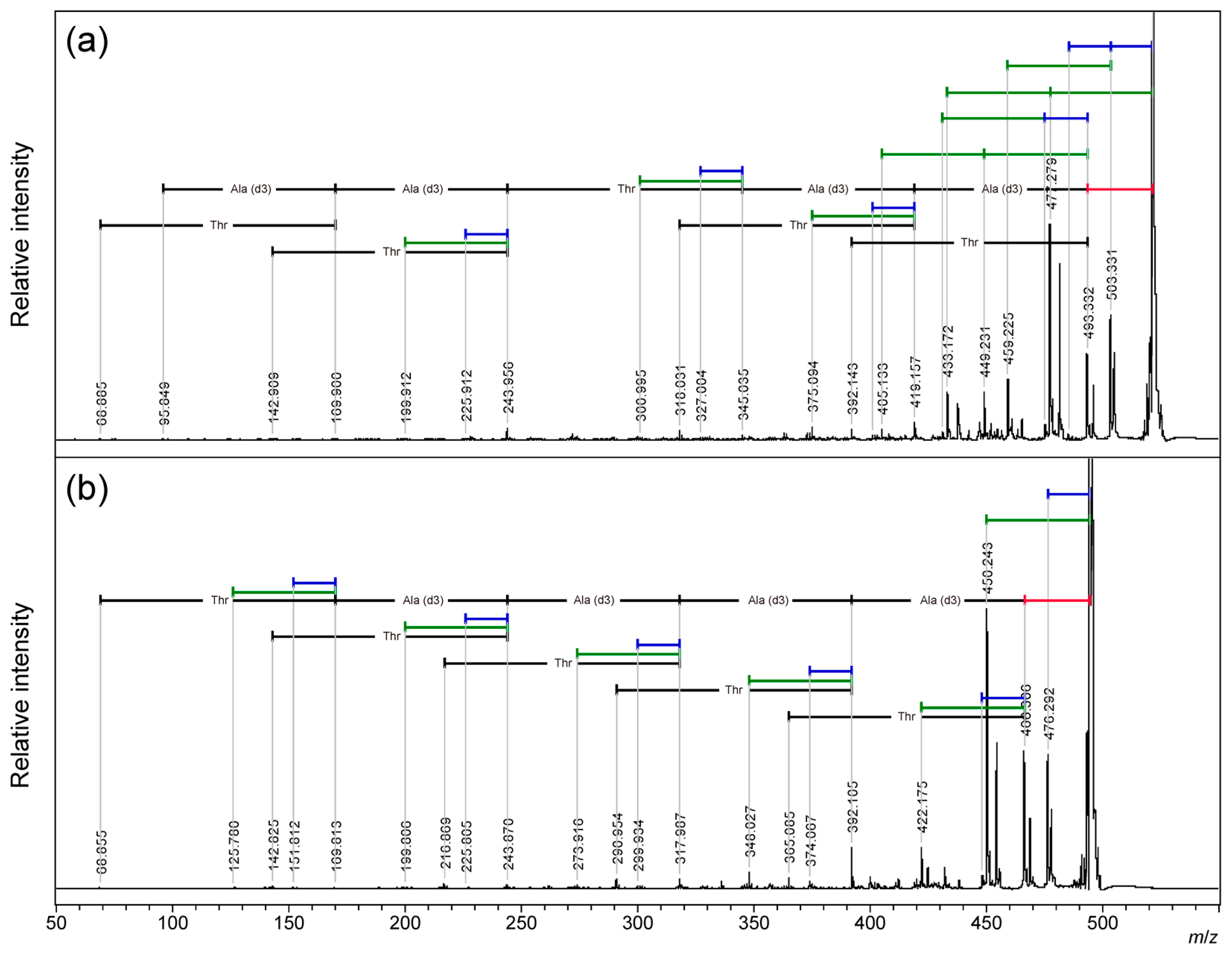

2.3. Searching for a Characteristic Fragmentation Mechanism Using Isotope-Labeled Derivatives

To clarify the origin of the 18 Da and 44 Da loss from the cyclic AFGP skeleton peptide, the alanine-3,3,3-d3 [A(d3)] modified peptide, cyclic TA(d3)A(d3)TA(d3)A(d3), and cyclic TA(d3)A(d3)A(d3)A(d3)A(d3), one of the two threonine residues was replaced with A(d3). MALDI-TOF/TOF MS analysis was performed on the sodium adduct precursor ions of the cyclic peptides. (

Figure 6, S6:

m/

z 330-530) From both precursor ions, a neutral loss of 44 Da was observed as the highest fragment peak. An additional neutral loss of 44 Da was observed only for the AFGP skeleton analog. The neutral loss of deuterium-labeled alanine (74 Da) was observed after a neutral loss of 28 Da. For the cyclic AFGP skeleton analog, losses of 18 Da or 44 Da were observed up to twice in total. (

Figure 6a;

Table S11) A loss of 18 or 44 Da after a 28 Da loss was also observed. From cyclic TA(d3)A(d3)A(d3)A(d3)A(d3), a 62 Da loss corresponding to the sequential loss of 18 and 44 Da was not observed, and a simplified fragmentation pattern was observed. (

Figure 6b;

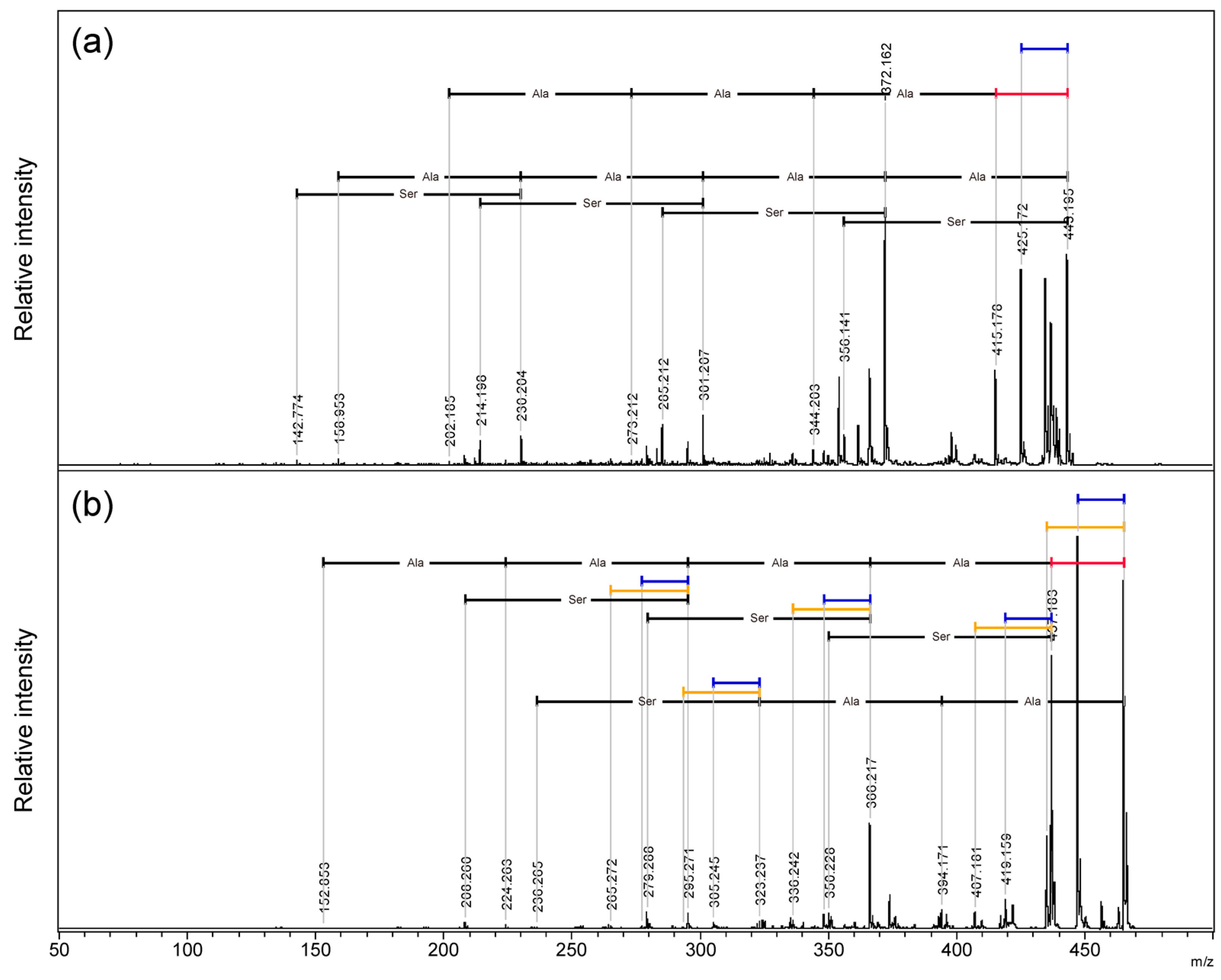

Table S12) In addition, MALDI-TOF/TOF MS of a cyclic SAAAAA peptide, in which threonine was replaced with serine, was performed. (

Figure 7, S7:

m/

z 270-470) From protonated precursor ion, the side chain was no longer released as an aldehyde and only a neutral loss of water was observed. In contrast to the threonine-containing cyclic peptide, at

m/

z 372, neutral loss of alanine residue without any other neutral loss was observed as the strongest fragment signal. Sequencing signals following a 28 Da neutral loss were also observed as minor signals compared to the direct neutral loss of amino acid sequence information. (

Figure 7a;

Table S13) From the sodium-added precursor ion, neutral loss of 18 Da was the strongest signal followed by 28 Da neutral loss, and the neutral loss of 30 Da corresponding CH

2O from serine side chain was a minor signal. Sequencing signals following a 28 Da neutral loss were the major sequencing signals. (

Figure 7b;

Table S14)

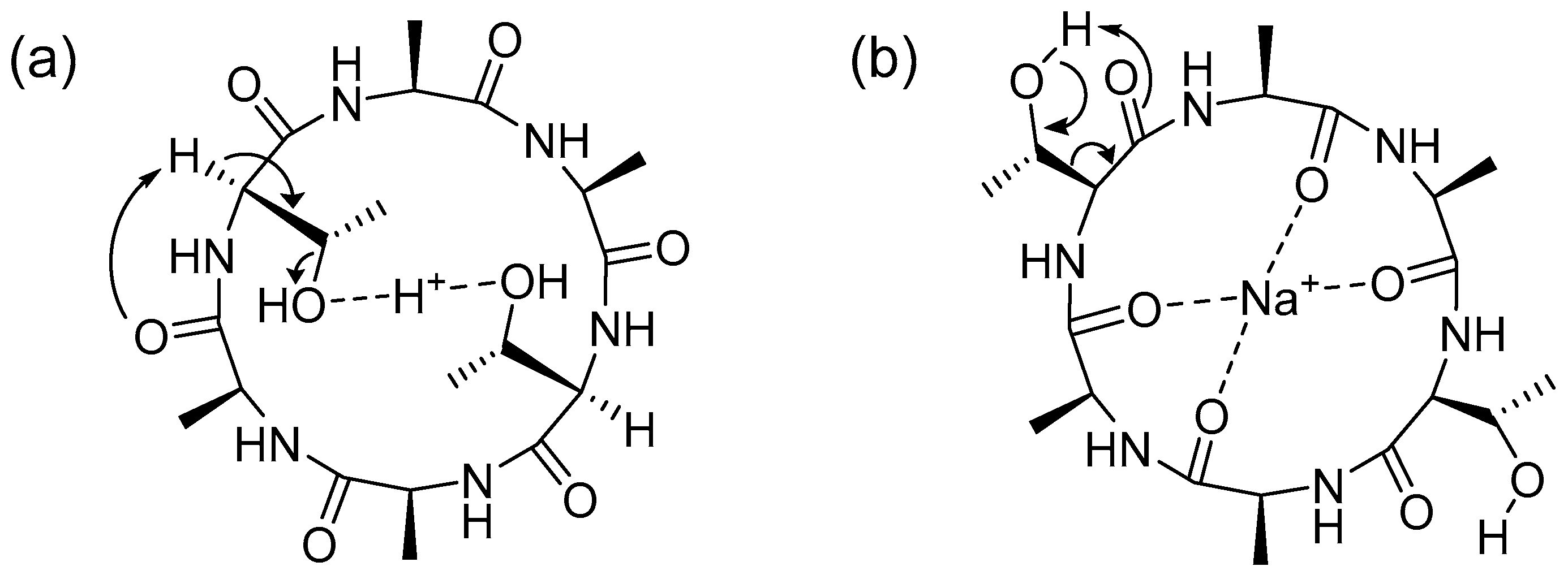

2.4. Side Chain Elimination Mechanism and Adduct Ion Selectivity of Cyclic Peptides

These fragmentation patterns clearly show that both the 18 Da and 44 Da neutral losses originate from the threonine side chain. For the cyclic peptide, the protonated precursor ion was dominated by a neutral loss of 18 Da. A 44 Da neutral loss was observed as the predominant fragment signal from the sodium adduct precursor ions. These different fragmentation reactions are expected to arise from differences in the coordination sites of the adduct ions. (

Figure 8) The protonated ions are expected to promote dehydration by coordinating with threonine hydroxyl groups. (

Figure 8a) The sodium adduct ions promoted the formation of a turn structure suitable for the loss of formaldehyde. (

Figure 8b) In the case of sodium adduct ions of linear and cyclic AFGP, glycosylation of the threonine hydroxyl group inhibits the conformation suitable for de-formaldehyde to give a 44 Da neutral loss even for the sodium adduct ion. (

Figure 2) De-glycoside reaction to give

an m/

z 406 signal (

Figure 2) as a free disaccharide also promoted the formation of a dehydrated peptide skeleton. Interestingly, the mechanism of the 44 Da neutral loss from the threonine side chain of the cyclic peptide might have different factors from the linear peptide previously reported [28,29] and our study using the linear peptide skeletons of AFGP. (

Figure 4 and

Figure 5) This is likely because threonine adopts a conformation suitable for neutral loss of acetaldehyde due to hydrophobic interactions between the methyl groups of alanine and threonine. [30] The hydrophobic interactions of the methyl groups are an important factor in the antifreeze activity of AFGP. [

18] Replacement of threonine with serine changes the conformation and antifreeze activity, [

18] as well as the selectivity and reactivity of neutral loss of the side chain. (

Figure 6 and

Figure 7) The hydroxyl groups of threonine and serine are the main stage of post-translational modification, and conformational changes associated with post-translational modification are the switch for protein function as well as functional control of drug candidates of cyclic (glycol)peptides. [

3,

14,31,32]

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Materials and Reagents

Fmoc-alanine-OH, Fmoc-threonine-OH, Fmoc-serine-OH, and 2-chloro trityl resin were purchased from Novabiochem® (Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany). L-Alanine-3,3,3-d3-N-Fmoc was purchased from CDN Isotopes Inc. (Pointe-Claire, Quebec, Canada). O-benzotriazole-N,N,N',N'-tetramethyluronium hexafluorophosphate (HBTU), 1-hydroxybenzotriazole hydrate (HOBt·H₂O), N,N-diisopropylethylamine (DIPEA), dichloromethane (DCM) (SP grade), dimethylformamide (DMF) (SP grade), methanol, piperidine, sodium hydroxide, 2,5-dihydroxybenzoic acid (DHB), sodium bicarbonate (NaHCO₃), O-benzylhydroxylamine (BOA), acetonitrile (HPLC grade), and diisopropylcarbodiimide (DIC) were purchased from FUJIFILM Wako Pure Chemical Corporation (Osaka, Japan). Hydroxybenzotriazole active ester (HOAt) was purchased from GenScript Biotech Corporation (Piscataway, NJ, USA). Hexafluoroisopropanol (HFIP), 2,2,2-trifluoroethanol (TFE), and thionyl chloride (SOCl₂) were purchased from Tokyo Chemical Industry Co. Ltd. (Tokyo, Japan). Trityl-OH ChemMatrix resin was purchased from Biotage AB (Uppsala, Sweden). Additionally, 700 µm STA µFocus plates measuring 24×16 c were purchased from Hudson Surface Technology (Fort Lee, USA).

3.2. Synthesis and Cyclization of Linear AFGP (n = 2)-Related Peptides

The Trityl-OH ChemMatrix resin was chlorinated by treatment with 2% SOCl₂ in DCM, and the reaction mixture was stirred overnight with four equivalents of the first amino acid and six equivalents of DIEA. After the completion of the reaction, MeOH was added to quench any unreacted sites, and the resin was washed three times with DMF, DCM, and DMF. Fmoc deprotection was performed using 20% piperidine in DMF under microwave irradiation (0–40 W) at 50°C for 3 min. The coupling reaction was carried out by adding 4 equivalents of the amino acid (or 1.5 equivalents of glyco amino acids), 4 equiv of HBTU, HOBt, and 6 equiv of DIEA under microwave irradiation (0–40 W) at 50°C for 9 min. For glyco-amino acids, two equivalents of HBTU and HOBt, and four equivalents of DIEA were added to the reaction. The resin was cleaved by stirring in HFIP/DCM (1:4 v/v) for 2 h followed by freeze-drying. The resulting product was then subjected to deacetylation by treatment with a NaOH/MeOH solution adjusted to pH 12.5.[33] The products were analyzed after deacetylation.

The synthesis of cyclic AFGP was carried out similarly to the naked peptide version.[

26] After cleavage, the sample was dissolved in TFE/DCM (1:1 v/v) solution at 1mM. Five equivalents of HOAt and DIC were added. The mixture was stirred overnight at room temperature, dried, and the sugars were deacetylated before analysis.

3.3. Synthesis of Linear Peptides and Their Cyclization

A 2-chrolo trityl resin was used for peptides without glycan. The resin was swollen in DCM, and four equivalents of Fmoc amino acid and six equivalents of DIEA were added. The mixture was then stirred overnight at room temperature. After the incorporation of the first residue, MeOH was added and the resin was washed three times with DMF, DCM, and DMF. Fmoc deprotection was performed using 20% piperidine in DMF.

The coupling reaction was performed by adding four equivalents of the amino acid, four equivalents of HBTU, HOBt, and six equivalents of DIEA under microwave irradiation (0–40 W) at 50°C for 9 min. The amino acids were then incorporated into the resin. Six linear peptides were synthesized using this method: H-TAATAA-OH, H-ATAATA-OH, H-AATAAT-OH, H-TA(d3)A(d3)TA(d3)A(d3)-OH, H-TA(d3)A(d3)A(d3)A(d3)A(d3)-OH, and H-SAAAAA-OH.

The first three peptides (H-TAATAA-OH, H-ATAATA-OH, and H-AATAAT-OH) were analyzed directly without further modification. H-TAATAA-OH was also subjected to cyclization, along with the remaining three peptides (H-TA(d3)A(d3)TA(d3)A(d3)-OH, H-TA(d3)A(d3)A(d3)A(d3)A(d3)-OH, and H-SAAAAA-OH), using the same way as for Cyclic AFGP synthesis. Resin cleavage was performed by stirring the resin in HFIP/DCM (1:4 v/v) for 2 h. After cleavage, the peptides were dissolved in a (1:1 v/v) TFE/DCM solution at a concentration of 1 mM. HOAt and DIC (five equivalents) were added to this solution, and the mixture was stirred overnight at room temperature. The products were then freeze-dried and analyzed.

3.4. MALDI-TOF/TOF Analysis

The matrix for the proton adduct ion analysis was prepared using DHB (10 mM) in a water/acetonitrile/TFA mixture (50:50:0.1, v/v/v). For the sodium adduct ion analysis, the matrix consisted of BOA/DHB/Na (12 mM/10 mM/1 mM) in a water/acetonitrile mixture (1:1, v/v).[

21] The samples were dissolved in a water/acetonitrile mixture (1:1, v/v) at a concentration of 1 μg/μL. A 0.35 μL aliquot of the sample solution was mixed with 0.35 μL of the matrix solution, spotted onto a MALDI plate (STA μFocus plate, 24 × 16, 700 μm), and air-dried before measurement.

All tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS) analyses were performed using an Ultraflex III MALDI-TOF/TOF instrument (Bruker, Bremen, Germany) equipped with a 200 Hz Smartbeam Nd:YAG laser (355 nm).

For the TOF/TOF analysis,[34] the precursor ions were initially accelerated to 8.0 kV in the MALDI ion source and selected within a time gate. The selected ions were further accelerated to 19.0 kV in the LIFT cell for fragmentation, and metastable post-source decay (PSD) ions were analyzed without additional fragmentation, such as collision-induced dissociation.

The two types of AFGP were analyzed using 1200 laser shots in parent mode (40% laser power) and 1200 laser shots in fragment mode (72% laser power). Similarly, the four types of cyclic peptides were analyzed with 400 laser shots in parent mode (40% laser power) and 800 laser shots in fragment mode (72% laser power).

4. Conclusions

In this study, we identified characteristic small-molecule neutral loss patterns using MALDI-TOF/TOF MS of linear and cyclic antifreeze glycoproteins and their skeleton peptides. These neutral losses occurred because of the elimination of carbon monoxide (28 Da) associated with ring opening, dehydration (18 Da) of the C-terminal, and competitive elimination of water (18 Da) and acetaldehyde (44 Da) from the threonine side chain. In the competitive elimination of the threonine side chain, the ratio changed significantly depending on the difference in the adduct ion, the presence or absence of a glycosylated threonine residue, and substitution with serine.

The selectivity of this neutral loss depends on the position of the hydrogen bond and conformational changes in the threonine side chain. This study proposes a new fragmentation mechanism for cyclic peptides using mass spectrometry, and shows the possibility of using this mechanism for conformational analysis. Applied research, such as the search for physiologically active cyclic (glyco)peptides and functional prediction, is expected.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Figure S1: Enlarged view of

Figure 2 (

m/

z 600-910); Figure S2: Enlarged view of

Figure 2 (

m/z 300-540); Figure S3: Enlarged view of

Figure 3 (

m/

z 300-520); Figure S4: Enlarged view of

Figure 4 (

m/

z 315-510); Figure S5: Enlarged view of

Figure 5 (

m/

z 340-535); Figure S6: Enlarged view of

Figure 6 (

m/

z 330-530); Figure S7: Enlarged view of

Figure 7 (

m/

z 270-470); Table S1: Mass list of fragment ion peaks from linear AFGP (n = 2, precursor ion

m/

z 1257.5) in

Figure 2a; Table S2: Mass list of fragment ion peaks from cyclic AFGP (precursor ion

m/

z 1239.5) in

Figure 2b; Table S3: Mass list of fragment ion peaks from proton adduct ion of cyclic AFGP core peptide (precursor ion

m/

z 487.2) in

Figure 3a; Table S4: Mass list of fragment ion peaks from sodium adduct ion of cyclic AFGP core peptide (precursor ion

m/

z 509.2) in

Figure 3b; Table S5: Mass list of fragment ion peaks from proton adduct ion of linear TAATAA (precursor ion

m/

z 505.2) in

Figure 4a; Table S6: Mass list of fragment ion peaks from proton adduct ion of linear ATAATA (precursor ion

m/

z 505.2) in

Figure 4b; Table S7: Mass list of fragment ion peaks from proton adduct ion of linear AATAAT (precursor ion

m/

z 505.2) in

Figure 4c; Table S8: Mass list of fragment ion peaks from sodium adduct ion of linear TAATAA (precursor ion

m/

z 527.2) in

Figure 5a; Table S9: Mass list of fragment ion peaks from sodium adduct ion of linear ATAATA (precursor ion

m/

z 527.2) in

Figure 5b; Table S10: Mass list of fragment ion peaks from sodium adduct ion of linear AATAAT (precursor ion

m/

z 527.2) in

Figure 5c; Table S11: Mass list of fragment ion peaks from sodium adduct ion of alanine deuterium-labeled cyclic AFGP core peptide (precursor ion

m/

z 521.2) in

Figure 6a; Table S12: Mass list of fragment ion peaks from sodium adduct ion of cyclic TA(d3)A(d3)A(d3)A(d3)A(d3) (precursor ion

m/

z 494.2) in

Figure 6b; Table S13: Mass list of fragment ion peaks from proton adduct ion of cyclic SAAAAA (precursor ion

m/

z 443.2) in

Figure 7a; Table S14: Mass list of fragment ion peaks from proton adduct ion of cyclic SAAAAA (precursor ion

m/

z 465.2) in

Figure 7b.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.H.; methodology, K.F. and S.U.; validation, K.F., S.U. and H.H.; formal analysis, K.F.; investigation, K.F.; resources, H.H.; data curation, K.F.; writing—original draft preparation, K.F. and H.H.; writing—review and editing, H.H.; visualization, K.F. and H.H.; supervision, H.H.; project administration, H.H.; funding acquisition, H.H. All the authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (B: 22H02191 and 23K23458 to H.H.), Core-to-Core (Type B: JPJSCCB20240004 to H.H.), and Grant-in-Aid for JSPS Fellows (23KJ0052 to S.U.) from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS).

Data Availability Statement

All data are available upon request.

Acknowledgments

The authors appreciate the support of laboratory management and technical assistance from Maki Morita.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

-

Essentials of Glycobiology, 4th ed.; Varki, A., Cummings, R.D., Esko, J.D., Stanley, P., Hart, G.W., Aebi, M., Mohnen, D., Kinoshita, T., Packer, N.H., Prestegard, J.H., et al., Eds.; Cold Spring Harbor (NY), 2022; pp. 265-278.

- Wandall, H.H.; Nielsen, M.A.I.; King-Smith, S.; de Haan, N.; Bagdonaite, I. Global functions of O-glycosylation: promises and challenges in O-glycobiology. FEBS J 2021, 288, 7183–7212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ji, X.; Nielsen, A.L.; Heinis, C. Cyclic Peptides for Drug Development. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl 2024, 63, e202308251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Chen, S. Cyclic peptide drugs approved in the last two decades (2001-2021). RSC Chem Biol 2022, 3, 18–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenn, J.B.; Mann, M.; Meng, C.K.; Wong, S.F.; Whitehouse, C.M. Electrospray ionization for mass spectrometry of large biomolecules. Science 1989, 246, 64–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, K. The origin of macromolecule ionization by laser irradiation (Nobel lecture). Angew Chem Int Ed Engl 2003, 42, 3860–3870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabre, B.; Combier, J.P.; Plaza, S. Recent advances in mass spectrometry-based peptidomics workflows to identify short-open-reading-frame-encoded peptides and explore their functions. Curr Opin Chem Biol 2021, 60, 122–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grabarics, M.; Lettow, M.; Kirschbaum, C.; Greis, K.; Manz, C.; Pagel, K. Mass Spectrometry-Based Techniques to Elucidate the Sugar Code. Chem Rev 2022, 122, 7840–7908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seidler, J.; Zinn, N.; Boehm, M.E.; Lehmann, W.D. De novo sequencing of peptides by MS/MS. Proteomics 2010, 10, 634–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, W.T.; Ng, J.; Meluzzi, D.; Bandeira, N.; Gutierrez, M.; Simmons, T.L.; Schultz, A.W.; Linington, R.G.; Moore, B.S.; Gerwick, W.H.; et al. Interpretation of Tandem Mass Spectra Obtained from Cyclic Nonribosomal Peptides. Analytical Chemistry 2009, 81, 4200–4209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suckau, D.; Cornett, D.S. Protein sequencing by ISD and PSD MALDI-TOF MS. Analusis 1998, 26, M18–M21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schilling, B.; Wang, W.; McMurray, J.S.; Medzihradszky, K.F. Fragmentation and sequencing of cyclic peptides by matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization post-source decay mass spectrometry. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom 1999, 13, 2174–2179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeric, I.; Versluis, C.; Horvat, S.; Heck, A.J. Tracing glycoprotein structures: electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometric analysis of sugar-peptide adducts. J Mass Spectrom 2002, 37, 803–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hinou, H.; Kikuchi, S.; Ochi, R.; Igarashi, K.; Takada, W.; Nishimura, S.I. Synthetic glycopeptides reveal specific binding pattern and conformational change at O-mannosylated position of alpha-dystroglycan by POMGnT1 catalyzed GlcNAc modification. Bioorg Med Chem 2019, 27, 2822–2831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinou, H. Aniline derivative/DHB/alkali metal matrices for reflectron mode MALDI-TOF and TOF/TOF MS analysis of unmodified sialylated oligosaccharides and glycopeptides. Int J Mass Spectrom 2019, 443, 109–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villones, L.L., Jr.; Ludwig, A.K.; Kikuchi, S.; Ochi, R.; Nishimura, S.I.; Gabius, H.J.; Kaltner, H.; Hinou, H. Altering the Modular Architecture of Galectins Affects its Binding with Synthetic alpha-Dystroglycan O-Mannosylated Core M1 Glycoconjugates In situ. Chembiochem 2023, 24, e202200783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakui, H.; Yokoi, Y.; Horidome, C.; Ose, T.; Yao, M.; Tanaka, Y.; Hinou, H.; Nishimura, S.I. Structural and molecular insight into antibody recognition of dynamic neoepitopes in membrane tethered MUC1 of pancreatic cancer cells and secreted exosomes. RSC Chem Biol 2023, 4, 564–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tachibana, Y.; Fletcher, G.L.; Fujitani, N.; Tsuda, S.; Monde, K.; Nishimura, S. Antifreeze glycoproteins: elucidation of the structural motifs that are essential for antifreeze activity. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl 2004, 43, 856–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devries, A.L.; Wohlschlag, D.E. Freezing Resistance in Some Antarctic Fishes. Science 1969, 163, 1073-+. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hachisu, M.; Hinou, H.; Takamichi, M.; Tsuda, S.; Koshida, S.; Nishimura, S. One-pot synthesis of cyclic antifreeze glycopeptides. Chem Commun (Camb) 2009, 1641–1643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barada, E.; Hinou, H. BOA/DHB/Na: An Efficient UV-MALDI Matrix for High-Sensitivity and Auto-Tagging Glycomics. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urakami, S.; Hinou, H. Sodium-Doped 3-Amino-4-hydroxybenzoic Acid: Rediscovered Matrix for Direct MALDI Glycotyping of O-Linked Glycopeptides and Intact Mucins. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.X.; Wang, B.; Wei, Z.L.; Zhang, H.; Guo, X.H. Structure and further fragmentation of significant [a+Na-H]+ ions from sodium-cationized peptides. Journal of Mass Spectrometry 2015, 50, 212–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, C.R.; Abutokaikah, M.T.; Harrison, A.G.; Bythell, B.J. Proton Mobility in b Ion Formation and Fragmentation Reactions of Histidine-Containing Peptides. J Am Soc Mass Spectr 2016, 27, 487–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farrugia, J.M.; O'Hair, R.A.J.; Reid, G.E. Do all b ions have oxazolone structures? Multistage mass spectrometry and ab initio studies on protonated-acyl amino acid methyl ester model systems. Int J Mass Spectrom 2001, 210, 71–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinou, H.; Hyugaji, K.; Garcia-Martin, F.; Nishimura, S.I.; Albericio, F. H-bonding promotion of peptide solubility and cyclization by fluorinated alcohols. Rsc Advances 2012, 2, 2729–2731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polfer, N.C.; Oomens, J.; Suhai, S.; Paizs, B. Spectroscopic and theoretical evidence for oxazolone ring formation in collision-induced dissociation of peptides. J Am Chem Soc 2005, 127, 17154–17155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neta, P.; Pu, Q.L.; Yang, X.Y.; Stein, S.E. Consecutive neutral losses of HO and CHO from N-Terminal Thr-Thr and Thr-Ser in collision-induced dissociation of protonated peptides Position dependent water loss from single Thr or Ser. Int J Mass Spectrom 2007, 267, 295–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.X.; Wang, B.; Wei, Z.L.; Cao, Y.W.; Guan, X.S.; Guo, X.H. Characteristic neutral loss of CHCHO from Thr-containing sodium-associated peptides. Journal of Mass Spectrometry 2015, 50, 488–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barchi, J.J.; Strain, C.N. The effect of a methyl group on structure and function: Serine vs. threonine glycosylation and phosphorylation. Front Mol Biosci 2023, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newcombe, E.A.; Delaforge, E.; Hartmann-Petersen, R.; Skriver, K.; Kragelund, B.B. How phosphorylation impacts intrinsically disordered proteins and their function. Essays Biochem 2022, 66, 901–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayakawa, S.; Matsushita, T.; Yokoi, Y.; Wakui, H.; Garcia-Martin, F.; Hinou, H.; Matsuoka, K.; Nouso, K.; Kamiyama, T.; Taketomi, A.; et al. Impaired O-Glycosylation at Consecutive Threonine TTX Motifs in Mucins Generates Conformationally Restricted Cancer Neoepitopes. Biochemistry 2020, 59, 1221–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Izumi, R.; Matsushita, T.; Fujitani, N.; Naruchi, K.; Shimizu, H.; Tsuda, S.; Hinou, H.; Nishimura, S. Microwave-assisted solid-phase synthesis of antifreeze glycopeptides. Chemistry 2013, 19, 3913–3920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suckau, D.; Resemann, A.; Schuerenberg, M.; Hufnagel, P.; Franzen, J.; Holle, A. A novel MALDI LIFT-TOF/TOF mass spectrometer for proteomics. Anal Bioanal Chem 2003, 376, 952–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).