Submitted:

30 December 2024

Posted:

03 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

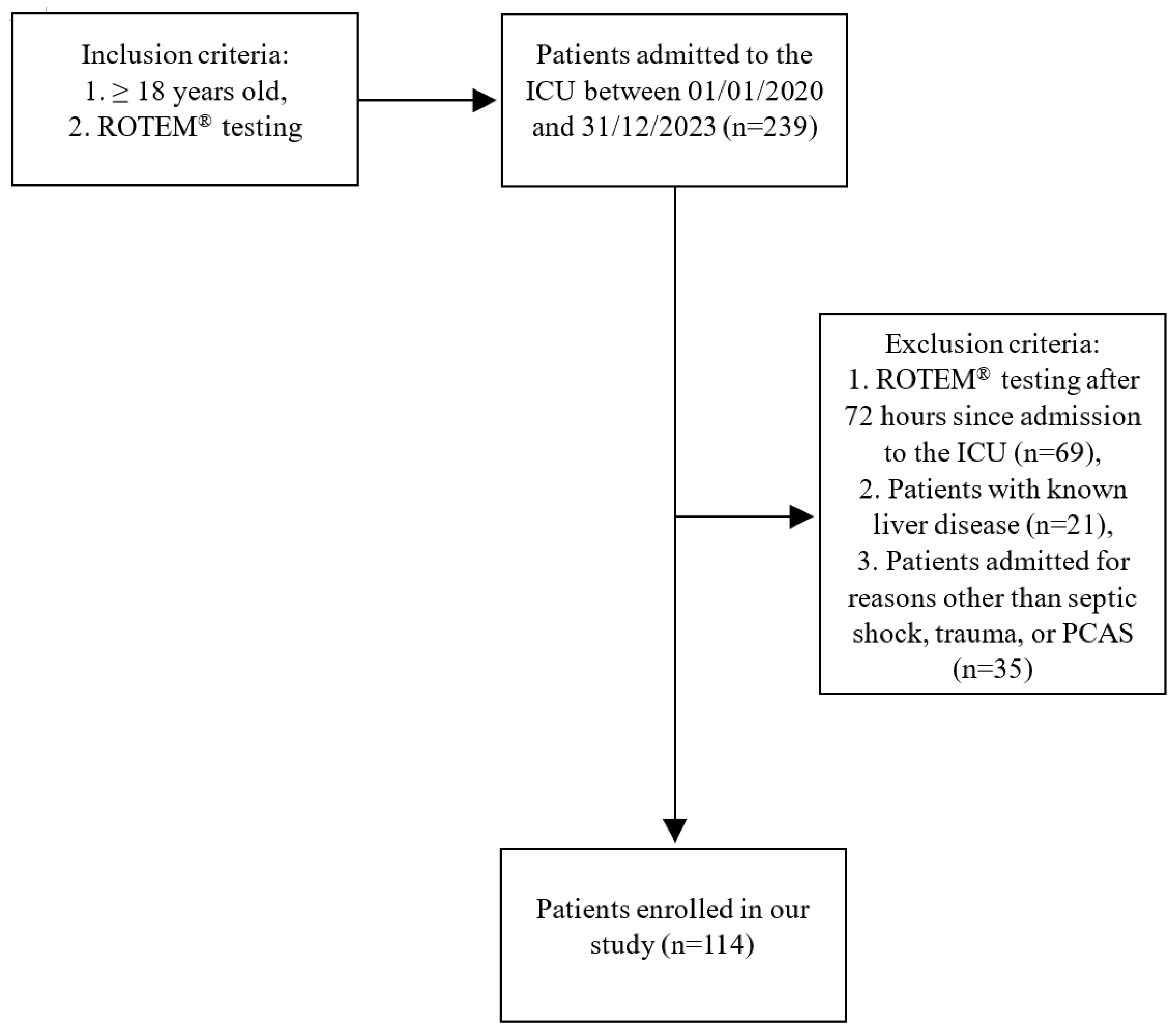

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Collected Clinical Data

2.2. Collected Laboratory Data

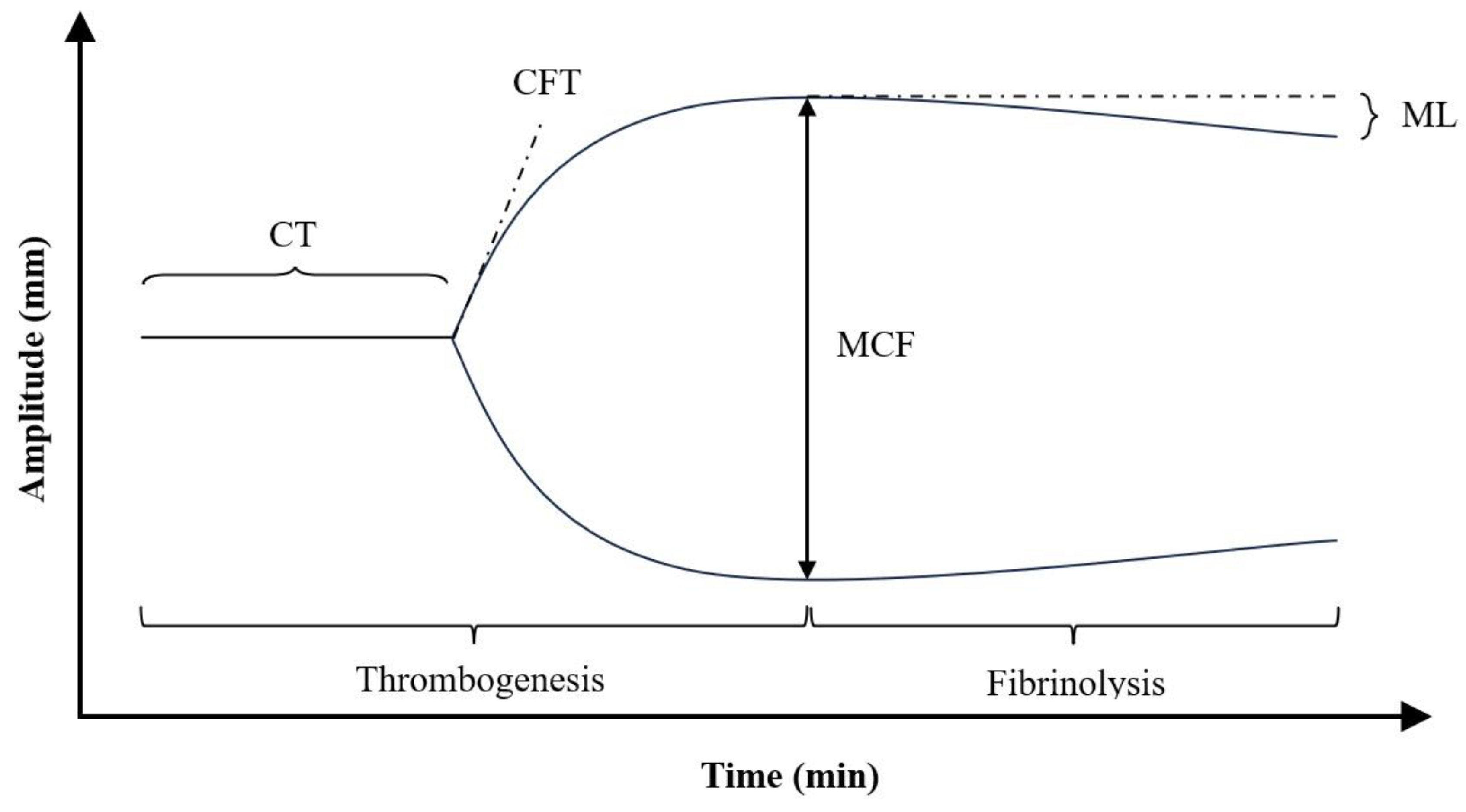

2.3. Principle of Operation of Rotational Thromboelastometry

2.4. Primary and Secondary Endpoints

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Authors Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Helms, J.; Iba, T.; Connors, J.M.; Gando, S.; Levi, M.; Meziani, F.; Levy, J.H. How to manage coagulopathies in critically ill patients. Intensive Care Med 2023, 49:273-290. [CrossRef]

- Levi, M.; Opal, S.M. Coagulation abnormalities in critically ill patients. Critical Care 2006, 10:222. [CrossRef]

- MacLeod, J.B.A.; Lynn, M.; McKenney, M.G.; Cohn, S. M.; Murtha, M. Early coagulopathy predicts mortality in trauma. J Trauma 2003, 55(1):39-44. [CrossRef]

- Johansson, P.I.; Stensballe, J.; Ostrowski, S.R. Shock induced endotheliopathy (SHINE) in acute critical illness – a unifying pathophysiologic mechanism. Crit Care. 2017, Feb 9;21(1):25. [CrossRef]

- Johansson, P.I.; Ostrowski, S.R. Acute coagulopathy of trauma: balancing progressive catecholamine induced endothelial activation and damage by fluid phase anticoagulation. Med Hypothes. 2010, Dec;75(6):564-7. [CrossRef]

- Singer, M.; Deutschman, C.S.; Seymour, C.W.; Shankar-Hari, M.; Annane, D.; Bauer, M.; Bellomo, R.; Bernard, G.R.; Chiche, J-D.; Coopersmith, C.M.; Hotchkiss, R.S.; Levy, M.M.; Marshall, J.C.; Martin, G.S., Opal, S.M.; Rubenfeld, G.D.; van der Poll, T.; Vincent, J-L.; Angus, D. C. The third international consensus definitions for sepsis and septic shock (Sepsis 3). JAMA 2016, 315(8):801-10. [CrossRef]

- Prakash, S.; Verghese, S.; Roxby, D.; Dixon, D.; Bihari, S.; Bersten, A. Changes in fibrinolysis and severity of organ failure in sepsis: a prospective observational study using point-of-care test-ROTEM. J Crit Care 2015, 30(2):264-70. [CrossRef]

- Daudel, F.; Kessler, U.; Folly, H.; Lienert, J.S.; Takala, J.; Jakob, S.M. Thromboelastometry for the assessment of coagulation abnormalities in early and established adult sepsis: a prospective cohort study. Crit Care 2009, 13(2): R42. [CrossRef]

- Collins, P.W.; Macchiavello, L.I.; Lewis, S.J.; Macartney, N.J.; Saayman, A.G.; Luddington, R.; Baglin, T.; Findlay, G.P. Global tests of haemostasis in critically ill patients with severe sepsis syndrome compared to controls. Br J Haematol 2006, 135(2):220-7. [CrossRef]

- Simmons, J.; Pittet, J-F. The coagulopathy of acute sepsis. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol 2015, 28(2):227-36. [CrossRef]

- Ostrowski, S.R.; Windeløv, N.A.; Ibsen, M.; Haase, N.; Perner, A.; Johansson, P.I. Consecutive thromboelastography clot strength profiles in patients with severe sepsis and their association with 28-day mortality; a prospective study. J Crit Care 2013, 28(3):317.e1-11. [CrossRef]

- Davies, G.R.; Pillai, S.; Lawrence, M.; Mills, G.M.; Aubrey, R.; D’Silva, L.; Battle, C.; Williams, R.; Brown, R.; Thomas, D.; Morris, K.; Evans, P.A. The effect of sepsis and its inflammatory response on mechanical clot characteristics; a prospective observational study. Intensive Care Med 2016, 42(12):1990-1998. [CrossRef]

- Czempik, P.F.; Wiórek, A. Rotational thromboelastometric profile in early sepsis: a prospective cohort study. Biomedicine 2024, 12(8):1880. [CrossRef]

- Brohi, K.; Gruen, R. L.; Holcomb, J.B. Why are bleeding trauma patients still dying? Intensive Care Med 2019, 45(5):709-711. [CrossRef]

- Brohi, K.; Singh, J.; Heron, M.; Coats, T. Acute traumatic coagulopathy. J Trauma 2003, 54(6):1127-30. [CrossRef]

- Cap, A.; Hunt, B.J. The pathogenesis of traumatic coagulopathy. Anaesthesia 2015, 70: Suppl 1:96-101, e32-4. [CrossRef]

- Simmons, J.W.; Powell, M.F. Acute traumatic coagulopathy: pathophysiology and resuscitation. Br J Anaesth 2016, 117(suppl 3):iii31-iii43. [CrossRef]

- Sillen, M.; Declerck, P.J. A narrative review on plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 and its (patho)physiological role: to target or not to target? Int J Mol Sci. 2021, Mar 8;22(5):2721. [CrossRef]

- Brohi, K.; Cohen, M.J.; Ganter, M.T.; Schultz, M.J.; Levi, M.; Mackersie, R.; Pittet, J-F. Acute coagulopathy of trauma: hypoperfusion induces systemic anticoagulation and hyperfibrinolysis. J Trauma 2008, 64(5):1211-7. [CrossRef]

- Puranik, N.G.; Verma, T.Y.P.; Pandit, G.A. The study of coagulation parameters in polytrauma patients and their effects on outcome. J Hematol 2018, 7(3):107-111. [CrossRef]

- Davenport, R. Pathogenesis of acute traumatic coagulopathy. Transfusion 2013, 53 Suppl 1:23S27S. [CrossRef]

- Smith, A.R.; Karim, S.A.; Reif, R.R.; Beck, W.C.; Taylor, J.R.; Davis, B.L.; Bhavaraju, A.V.; Jensen, H.K.; Kimbrough, M.K.; Sexton, K.W. ROTEM as a predictor of mortality in patients with severe trauma. J Surg Res 2020, 251:107-111. [CrossRef]

- Adrie, C.; Monchi, M.; Laurent, I.; Um, S.; Yan, S.B.; Thuong, M.; Cariou, A.; Charpentier, J.; Dhainaut, J-F. Coagulopathy after successful cardiopulmonary resuscitation following cardiac arrest: implication of the protein C anticoagulant pathway. J Am Coll Cardiol 2005, 46(1):21-8. [CrossRef]

- Gando, S.; Wada, T. Disseminated intravascular coagulation in cardiac arrest and resuscitation. J Thromb Haemost 2019, 17(8):1205-16. [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.H.; Lee, B.K.; Jeung, K.W.; Jung, Y.H.; Lee, S.M.; Cho, Y.S.; Yun, S-W.; Min, Y.I. Disseminated intravascular coagulation is associated with the neurologic outcome of cardiac arrest survivors. Am J Emerg Med 2017, 35(11):1617-1623. [CrossRef]

- Shinada, K.; Koami, H.; Mastuoka, A.; Sakamoto, Y. Prediction of spontaneous return f circulation in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest with non-shockable initial rhythm using point- of care testing: a retrospective observational study. World J Emerg Med 2023, 14(2):89-95. [CrossRef]

- Schöchl, H.; Cadamuro, J.; Seidl, S.; Franz, A.; Solomon, C.; Schlimp, C.J.; Ziegler, B. Hyperfibrinolysis is common in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: results from a prospective observational thromboelastometry study. Resuscitation 2013, 84(4): 454-9. [CrossRef]

- Kaomi, H.; Sakamoto, Y.; Sakurai, R.; Ohta, M.; Imahase, H.; Yahata, M.; Umeka, M.; Miike, T.; Nagashima, F.; Iwamura, T.; Yamada, K.C.; Inoue, S. Thromboelastometric analysis of the risk factors for return of spontaneous circulation in adult patients with out- of- hospital cardiac arrest. PLoS One 2017, 12(4):e0175257. [CrossRef]

- Lier, H.; Vorweg, M.; Hanke, A.; Görlinger, K. Thromboelastometry guided therapy of severe bleeding. Essener Runde algorithm. Hamostaseologie 2013, 33(1):51-61. [CrossRef]

- Ng, V.L. Liver disease, coagulation testing, and hemostasis. Clin Lab Med 2009, 29(2):265-82. [CrossRef]

- Levi, M.; Schultz, M.; van der Poll, T. Coagulation biomarkers in critically ill patients. Crit Care Clin 2011, 27(2):281-97. [CrossRef]

- Meybohm, P.; Zacharowski, K.; Weber, C.F. Point-of-care coagulation management in intensive care medicine. Crit Care 2013, 17(2):218. [CrossRef]

- Benes, J.; Zatloukal, J.; Kletecka, J. Viscoelastic methods of blood clotting assessment - a multidisciplinary review. Front Med (Lausanne) 2015, 14:2:62. [CrossRef]

- Spalding, G.J.; Hartrumpf, M.; Sierig, T.; Oesberg, N.; Kirschke, C.G.; Albes, M.J. Cost reduction of perioperative coagulation management in cardiac surgery: value of “bedside” thromboelastography (ROTEM). Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2007, 31(6):1052-7. [CrossRef]

- von Elm, E., Altman, D.G.; Egger, M.; Pocock, S.J.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Vandenbroucke, J.P.; STROBE Initiative. The strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. J Clin Epidemiol. 2008, Apr;61(4):344-9. [CrossRef]

- Curry, N.S.; Davenport, R.; Pavord, S.; Mallett, S.V.; Kitchen, D.; Klein, A.A.; Maybury, H.; Collins, P.W.; Laffan, M. The use of viscoelastic assays in the management of major bleeding: a British Society for Haematology guideline. Br J Haematol. 2018, Sep;182(6):789-806. [CrossRef]

- Taylor, F.B., Jr.; Toh, C.H.; Hoots, W.K.; Wada, H.; Levi, M.; Scientific Subcommittee on Disseminated Intravascular Co-agulation (DIC) of the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis (ISTH). Towards definition, clinical and la-boratory criteria, and a scoring system for disseminated intravascular coagulation. Thromb. Haemost. 2001, 86, 1327–1330. [CrossRef]

- Heubner , L.; Hattenhauer, S.; Güldner, A.; Petrick, P.L.; Rößler, M.; Schmitt, J.; Schneider, R.; Held, H.C.; Mehrholz, J.; Bodechtel, U.; Ragaller, M.; Koch, T.; Spieth, P.M. Characteristics and outcomes of sepsis patient with and without COVID-19. J Infect Public Health 2022, Jun;15(6):670-676. [CrossRef]

- Wilson, A.J.; Magee, F.; Bailey, M.; Pilcher, D.V.; French, C,; Nichol, A.; Udy, A.; Hodgson, C.L.; Cooper, D.J.; Reade, M.C.; Young, P.; Bellomo, R. Characteristics and outcomes of critically ill trauma patients in Australia and New Zealand (2005-2017). Crit Care Med. 2020, May;48(5):717-724. [CrossRef]

- Jansen, G.; Sauzet, O.; Borgstedt, R.; Entz, S.; Holland, F.O.; Lamprinaki, S.; Thies, K-C.; Scholz, S.S.; Rehberg, S.W. Incidence, characteristics and predictors of mortality following cardiac arrest in ICUs of a German university hospital: A retrospective cohort study. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2022, May 1;39(5):452-462. [CrossRef]

- Karwa, M.L.; Naqvi, A.A.; Betchen, M.; Puri, A.K. In-hospital triage. Crit Care Clin 2024, Jul;40(3):533-548. [CrossRef]

- Shafigh, N.; Hasheminik, M.; Shafigh, E.; Alipour, H.; Sayyadi, S.; Kazeminia, N.; Khoundabi, B.; Salarian, S. Prediction of mortality in ICU patients: A comparison between SOFA and other indicators. Nurs Crit Care. 2024, Nov;29(6):1619-1622. [CrossRef]

- Alhamdi, Y.; Toh, C-H. Recent advances in pathophysiology of disseminated intravascular coagulation: the role of circulating histones and neutrophil extracellular traps. F1000Res. 2017, Dec 18:6:2143. [CrossRef]

- Song, M.J.; Jang, Y.; Legrand, M.; Park, S.; Ko, R.F.; Suh, G.Y.; Oh, D.K.; Lee, S.Y.; Park, M.H.P.; Lim, C-M.; Jung, S.Y.; Lim, S.Y.; Korean Sepsis Alliance (KSA) investigator. Epidemiology of sepsis-associated acute kidney injury in critically ill patients: a multicenter, prospective, observational cohort study in South Korea. Crit Care. 2024, Nov 24;28(1):383. [CrossRef]

- Levi, M.; van der Poll, T. The role of natural anticoagulants in the pathogenesis and management of systemic activation of coagulation and inflammation in critically ill patients. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2008, Jul;34(5):459-68. [CrossRef]

- Kwaan. H.C. From fibrinolysis to plasminogen-plasmin system and beyond: a remarkable growth of knowledge, with personal observations on the history of fibrinolysis. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2014, Jul 40;(5):585-91. [CrossRef]

- Moore, H.B.; Moore, E.E.; Chapman, M.P.; McVaney, K.; Bryskiewicz, G.; Blechar, R.; Chin, T.; Burlew, C.C.; Pieracci, F.; West, F.B.; Fleming, C.D.; Ghasabyan, A.; Chandler, J.; Silliman, C.C.; Banerjee, A.; Sauaia, A. Plasma-first resuscitation to treat haemorrhage shock during emergency ground transportation in an urban area; a randomised trial. Lancet. 2018, Jul 28;392(10144):283-291. [CrossRef]

- Sperry, J.L.; Guyette, F.X.; Brown, J.B.; Yazer, M.H.; Triulzi, D.J.; Early-Young, B.J.; Adams, P.W.; Daley, B.J.; Miller, R.S.; Harbrecht, B.G.; Claridge, J.A.; Phelan, H.A.; Witham, W.R.; Putnam, A.T.; Duane, T.M.; Alarcon, L.H.; Callaway, C.W.; Zuckerbraun, B.S.; Neal, M.D.; Rosengart, M.R.; Forsythe, R.M.; Billiar, T.R.; Yealy, D.M.; Peitzman, A.B.; Zenati, M.S.; PAMPer Study Group. Prehospital plasma during air medical transport in trauma patients at risk for hemorrhagic shock. N Engl J Med. 2018, Jul 26;379(4):315-326. [CrossRef]

- Pusateri, A.E.; Moore, E.E.; Moore, H.B.; Le, T.D.; Guyette, F.X.; Chapman, M.P.; Sauaia, A.; Ghasabyan, A.; Chandler, J.; McVaney, J.; Brown, J.B.; Daley, B.J.; Miller, R.S.; Harbrecht, B.G.; Claridge, J.A.; Phelan, H.A.; Witham, W.R.; Putnam, A.T.; Sperry, J.L. Association of prehospital plasma transfusion wit survival in trauma patients with hemorrhagic shock when transport Times are longer than 20 minutes: a post hoc analysis of the PAMPer and COMBAT trials. JAMA Surg. 2020, Feb 1;155(2):e195085. [CrossRef]

- Drost, C.C.; Rovas, A.; Kümpers, P. Protection and rebuilding of the endothelial glycocalyx in sepsis – science or fiction? Matrix Biol Plus. 2021, Nov 3:12:100091. [CrossRef]

- Pape, T.; Hunkemöller, A.M.; Kümpers, P.; Haller, H.; David, S.; Stahl, K. Targeting the „sweet spot” in septic shock – a perspective on endothelial glycocalyx regulating proteins Heparanase-1 and -2. Matrix Biol Plus. 2021, Dec 2:12:100095. [CrossRef]

- Stahl, K.; Hillebrand, U.C.; Kiyan, Y.; Seeliger, B.; Schmidt, J.J.; Schenk, H.; Pape, T.; Schmidt, B.M.W.; Welte, T.; Hoeper, M.M.; Sauer, A.; Wygrecka, M.; Bode, C.; Wedemeyer, H.; Haller, H.; David, S. Effects of therapeutic plasma exchange on the endothelial glycocalyx in sepsis. Intensive Care Med. Exp. 2021, Nov 24;9(1):57. [CrossRef]

- El-Nawawy, A.A.; Elshinawy, M.I.; Khater, D.M.; Moustafa, A.A.; Hassanein, N.M.; Wali, Y.A.; Nazir, H.F. Outcome of early hemostatic intervention in children with sepsis and nonovert disseminated intravascular coagulation admitted to PICU: a randomized controlled trial. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2021, 22:e168-e177. [CrossRef]

- Gando, S.; Levi, M.; Toh, C-T. Trauma-induced innate immune activation and disseminated intravascular coagulation. J Thromb Haemost. 2024, Feb;22(2):337-351. [CrossRef]

- Wheeler, A.P.; Bernard, G.R. Treating patients with severe sepsis. NEJM 1999, 340:207-214. [CrossRef]

- Barbosa da Cruz, D.; Helms, J.; Aquino, L.R.; Stiel, L.; Cougourdan, L.; Broussard, C.; Chafey, P.; Riès-Kautt, M.; Meziani, F.; Toti, F.; Gaussem, P.; Anglés-Cano, E. DNA bound elastase of neutrophil extracellular traps degrades plasminogen, reduces plasmin formation, and decreases fibrinolysis: proof of concept in septic shock plasma. FASEB J. 2019, 33:14270-14280. [CrossRef]

- Hayakawa, M.; Katabami, K.; Wada, T.; Sugano, M.; Hoshino, H.; Sawamura, A.; Gando, S. Sivelestat (selective neutrophil elastase inhibitor) improves the mortality rate of sepsis associated with both acute respiratory distress syndrome and disseminated intravascular coagulation patients. Shock 2010, Jan;33(1):14-8. [CrossRef]

- Semeraro, N.; Ammollo, C.T.; Semeraro, F.; Colucci, M. Coagulopathy of acute sepsis. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2015, Sep;41(6):650-8. [CrossRef]

- Coleman, J.R.; Moore, E.E.; Kelher, M.R.; Jones, K.; Cohen, M.J.; Banerjee, A.; Silliman, C.C. Elucidating the molecular mechanisms of fibrinolytic shutdown after severe injury: the role of thrombin-activatable fibrinolysis inhibitor. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2023, Jun 1;94(6):857-862. [CrossRef]

- Favors, L.; Harrell, K.; Miles, V.; Hicks, R.C.; Rippy, M.; Parmer, H.; Edwards, A.; Brown, C.; Stewart, K.; Day, L.; Wilson, A.; Maxwell, R. Analysis of fibrinolytic shutdown in trauma patients with traumatic brain injury. Am J Surg. 2024, Jan:227:72-76. [CrossRef]

- Moore, H.B.; Moore, E.E.; Huebner, B.R.; Stettler, G.R.; Nunns, G.R.; Einersen, P.M.; Silliman, C.C.; Sauaia, A. Tranexamic acid is associated with increased mortality in patients with physiological fibrinolysis. J Surg Res. 2024, Dec:220:438-443. [CrossRef]

- Xie, Z.; Zhu, S.; Wang, J.; Zhang, M.; Lv, X.; Ma, Y.; Shan, H.; Zhong, Y. Relationship between coagulopathy score and ICU mortality: analysis of the MIMIC-IV database. Heliyon. 2024, Jul 14;10(14):e34644. [CrossRef]

- Richards, J.E.; Yang, S.; Kozar, R.A.; Scalea, T.M.; Hu, P. A machine learning-based coagulation risk index predicts acute traumatic coagulopathy in bleeding trauma patients. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2024, Sept 27. [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Wang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, J.; Wei, B. Predictive value of SYN-1 levels for mortality in sepsis patients in the emergency department. J Inflamm Res. 2024, Nov 26:17:9837-9846. [CrossRef]

- Johansson, P.I.; Vigstedt, M.; Curry, N.S.; Davenport, R.; Juffermans, N.P.; Stanworth, S.J.; Maegele, M.; Gaarder, C.; Brohi, K.; Stensballe, J.; Henriksen, H.H.; Targeted Action for Curing Trauma-Induced Coagulopathy (TACTIC) Collaborators. Trauma induced coagulopathy is limited to only one out of four shock induced coagulopathy (SHINE) phenotypes among moderate-severely injured trauma patients: an exploratory analysis. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med. 2024, Aug 19;32(1):71. [CrossRef]

- Matsumoto, H.; Annen, S.; Mukai, N.; Ohshita, M.; Murata, S.; Harima, Y.; Ogawa, S.; Okita, M.; Nakabayashi, Y.; Kikuchi, S.; Takeba, J.; Sato, N. Circulating Syndecan-1 levels are associated with chronological coagulofibrinolytic responses and the development of disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) after trauma: a retrospective observational study. J Clin Med. 2023, Jun29;12(13):4386. [CrossRef]

- Kravitz, M.S.; Kattouf, N.; Stewart, I.J.; Ginde, A.A.; Schmidt, E.P.; Shapiro, N.I. Plasma for prevention and treatment of glycocalyx degradation in trauma and sepsis. Crit Care. 2024, Jul 20;28(1):254. [CrossRef]

- Kozar, R.A.; Peng, Z.; Zhang, R.; Holcomb, J.B.; Pati, S.; Park, P.; Ko, T.C.; Paredes, A. Plasma restoration of endothelial glycocalyx in a rodent model of hemorrhagic shock. Anesth Analg. 2011, Jun;112(6):1289-95. [CrossRef]

- Guo, Q-Y.; Peng, J.; Shan, T-C.; Xu, M. Risk factors for mortality in critically ill patients with coagulation abnormalities: a retrospective cohort study. Curr Med Sci. 2024, Oct;44(5):912 922. [CrossRef]

- Greinacher, A.; Selleng, K. Thrombocytopenia in the intensive care unit patient. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program 2010, 2010:135-43. [CrossRef]

- Asiri, A.; Price, J.M.J.; Hazeldine, J.; McGee, K.C.; Sardeli, A.V.; Chen, Y-Y.; Sullivan, J.; Moiemen, N.S.; Harrison, P. Measurement of platelet thrombus formation in patients following severe thermal injury. Platelets. 2024, Dec;35(1):2420952. [CrossRef]

- Stettler, G.R.; Moore, E.E.; Moore, H.B.; Nunns, G.R.; Silliman, C.C.; Banerjee, A.; Sauaia, A. Redefining postinjury fibrinolysis phenotypes using two viscoelastic assays. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2019, Apr;86(4):679-685. [CrossRef]

- McKinley, T.O.; Lisboa, F.A.; Horan, A.D.; Gaski, G.E.; Mehta, S. Precision medicine applications to manage multiply injured patients with orthopaedic trauma. J Orthop Trauma. 2019, Jun:33 Suppl 6:S25-S29. [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | Summary measure (n = 114) |

| Age [years] | 49.3 (19.9) |

| Male | 76 (66.7%) |

| Septic shock | 51 (44.7%) |

| Trauma | 46 (40.4%) |

| CA | 17 (14.9%) |

| 30-day mortality | 52 (45.6%) |

| Time do death [days] | 10.8 (26.2) |

| Hospital length of stay [days] | 18.5 (7.0-35.0) |

| ICU length of stay [days] | 9.5 (2.0-19.25) |

| Surgery | 78 (68.4%) |

| CRRT | 70 (61.4%) |

| Characteristics | Survivors, n = 62 (54.4%) | Non-survivors, n =52 (45.6%) | p-value |

| Male | 44 (71%) | 32 (61.3%) | |

| Age [years] | 45.4 (19.5) | 54 (19.5) | 0.021 |

| APACHE II [points] | 24.8 (6.5) | 28.9 (7.3) | 0.002 |

| SAPS [points] | 59.6 (16.0) | 70.5 (17.2) | < 0.001 |

| Hospital LOS [days] | 35.9 (23.8) | 10.0 (10.0) | < 0.001 |

| ICU LOS [days] | 23.3 (22.7) | 7.0 (8.1) | < 0.001 |

| CT FIBTEM [seconds] | 73.0 (63.0-98.5) | 94.5 (69.0-220.5) | 0.009 |

| A5 FIBTEM [mm] | 11.6 (8.2) | 11.6 (8.7) | 0.995 |

| MCF FIBTEM [mm] | 14.4 (10.3) | 15.0 (11.2) | 0.777 |

| ML FIBTEM [%] | 0.0 (0.0-0.0) | 0.0 (0.0-0.0) | 0.592 |

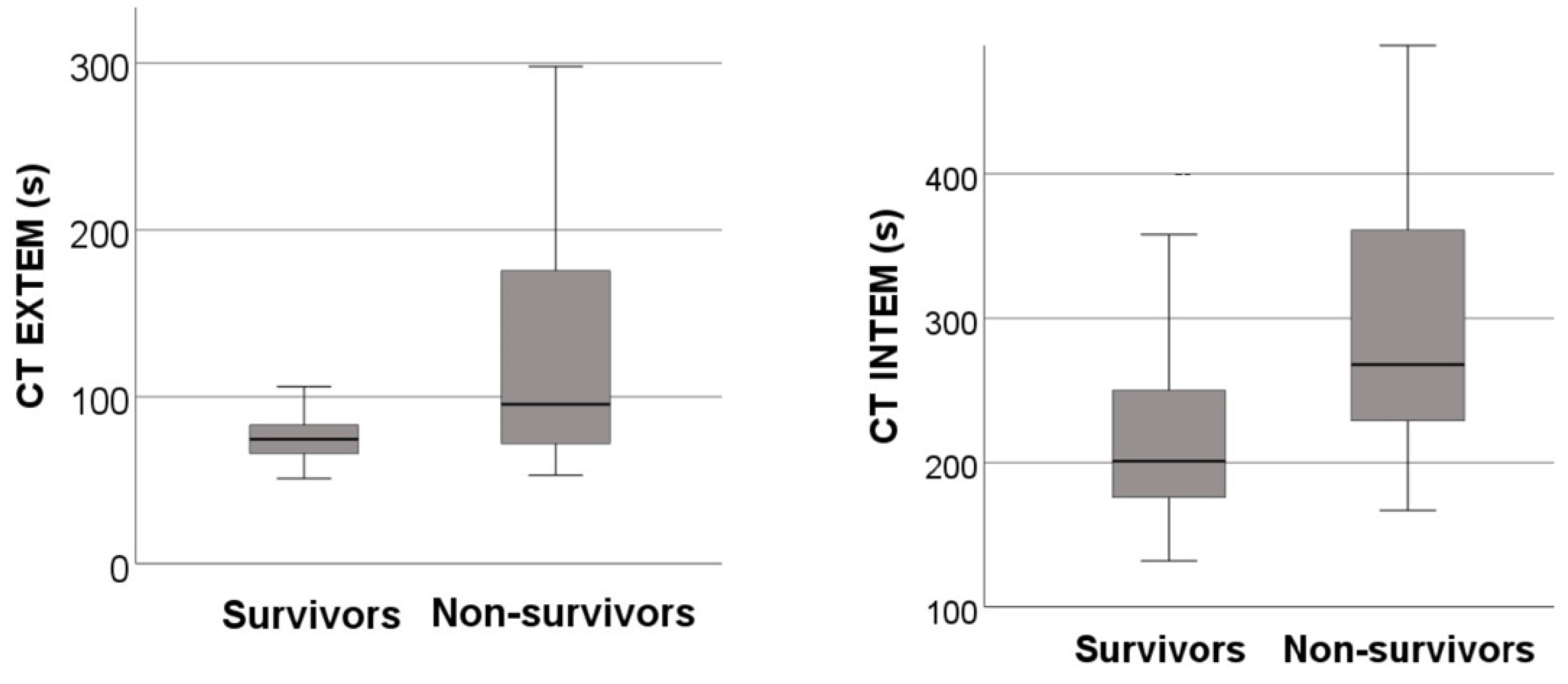

| CT EXTEM [seconds] | 74.5 (65.8-83.5) | 95.5 (72.0-176.3) | < 0.001 |

| MCF EXTEM [mm] | 57.4 (10.8) | 51.8 (17.1) | 0.044 |

| ML EXTEM [%] | 7.0 (3.0-13.0) | 4.0 (0.3-8.0) | 0.009 |

| CT INTEM [seconds] | 201.0 (175.8-251.0) | 268.0 (229.0-361.5) | < 0.001 |

| MCF INTEM [mm] | 53.6 (11.0) | 49.8 (14.8) | 0.138 |

| ML INTEM [%] | 7.0 (2.8-11.0) | 4.0 (0.0-9.0) | 0.035 |

| CT APTEM [seconds] | 67.0 (60.8-87.3) | 93.0 (75.3-186.0) | < 0.001 |

| MCF APTEM [mm] | 56.4 (10.1) | 52.1 (15.1) | 0.091 |

| ML APTEM [%] | 5.5 (2.0-11.0) | 3.0 (0.0-7.0) | 0.008 |

| INR | 1.3 (1.1-1.7) | 2.0 (1.4-3.4) | < 0.001 |

| aPTT [seconds] | 35.9 (32.7-49.4) | 54.6 (44.6-92.1) | < 0.001 |

| Fibrinogen [g/L] | 1.9 (1.2-2.9) | 2.2 (0.9-3.2) | 0.974 |

| D-dimer [μg/L] | 13.3 (6.0-35.2) | 17.4 (6.0-35.2) | 0.571 |

| pRBC [units] | 4.0 (2.0-9.0) | 2.0 (0.3-5.8) | 0.024 |

| FFP [units] | 2.0 (0.0-6.0) | 4.0 (2.0-8.0) | 0.022 |

| Platelets [units] | 0.0 (0.0-1.0) | 0.0 (0.0-1.8) | 0.5 |

| Cryoprecipitate [units] | 0.0 (0.0-0.0) | 0.0 (0.0-0.0) | 0.798 |

| Prothrombin concentrate [units] | 0.0 (0.0-0.0) | 0.0 (0.0-0.0) | 0.827 |

| Fibrinogen concentrate [grams] | 0.0 (0.0-2.0) | 2.0 (0.0-3.8) | 0.281 |

| mISTH-DIC | 17 (27.4) | 25 (48.1) | 0.023 |

| CRP [mg/L] | 39.1 (2.7-133.5) | 62.3 (3.1-133.5) | 0.491 |

| Procalcitonin [ng/mL] | 1.5 (0.6-11.6) | 4.2 (0.9-9.2) | 0.425 |

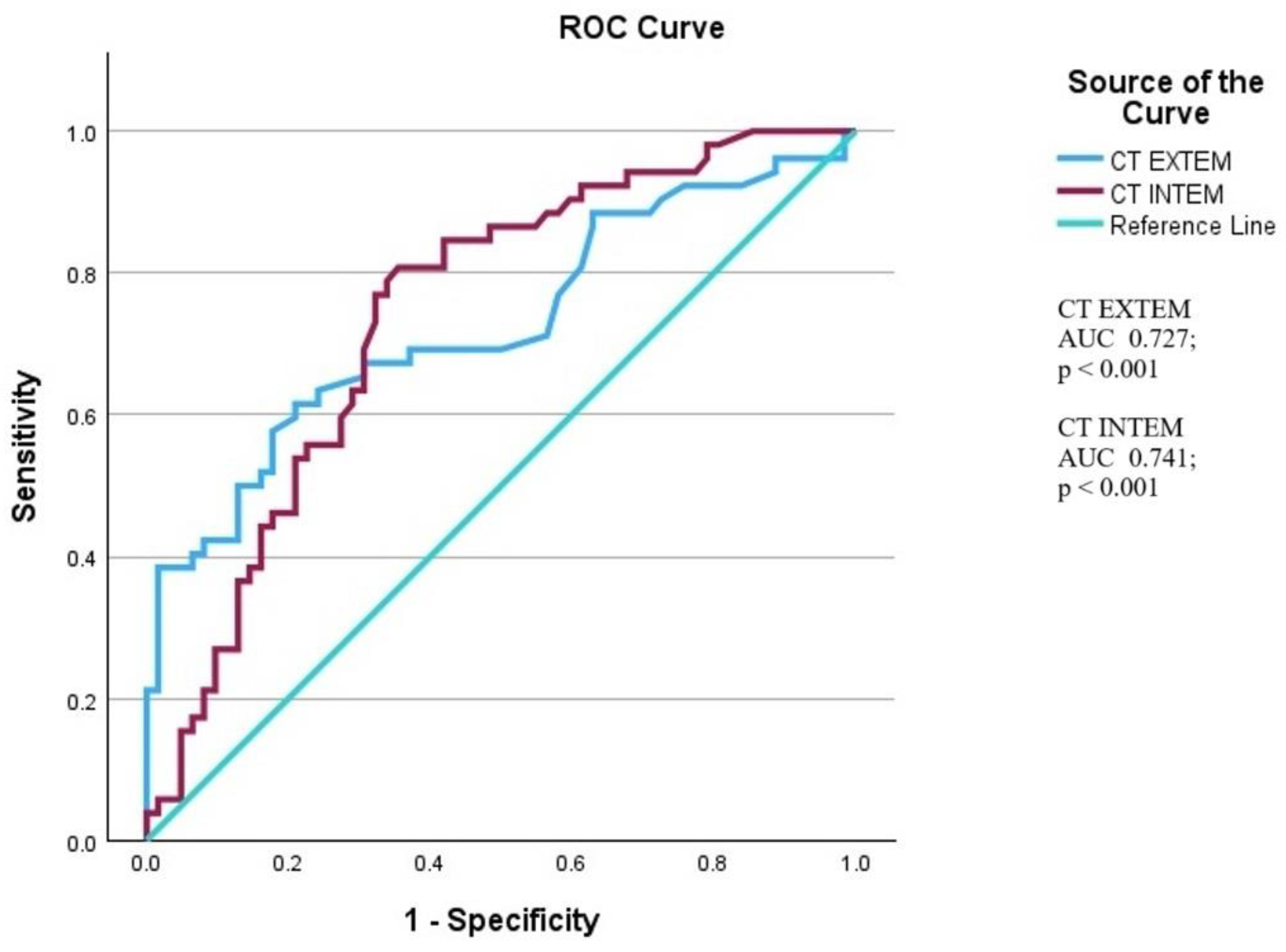

| Predictor | OR | 95% CI | p-value | |

| Model 1 including an external pathway of coagulation cascade | ||||

| CT EXTEM | 1.024 | 1.011-1.038 | < 0.001 | |

| Age in years | 1.027 | 1.003-1.051 | 0.026 | |

| APACHE II | 1.070 | 1.001-1.142 | 0.045 | |

| Model 2 including an internal pathway of coagulation cascade | ||||

| CT INTEM | 1.006 | 1.001-1.010 | 0.009 | |

| Age in years | 1.018 | 0.997-1.040 | 0.094 | |

| APACHE II | 1.065 | 1.001-1.134 | 0.047 | |

| CT EXTEM | CT INTEM | |||

| Outcome | r | p-value | r | p-value |

| Hospital length of stay | -0.331 | < 0.001 | -0.292 | 0.002 |

| mISTH-DIC | 0.390 | < 0.001 | 0.373 | < 0.001 |

| INR | 0.599 | < 0.001 | ||

| aPTT | 0.718 | < 0.001 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).