Submitted:

19 October 2025

Posted:

21 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

Data Collection and Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

6. Limitations

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ALT | Alanin Aminotransferase |

| AST | Aspartate Aminotransferase |

| COPD | Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease |

| CTPA | Computed Tomography Pulmonary Angiography |

| CPR | Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation |

| ICU | Intensive Care Unit |

| LOS | Lenght of Stay |

| PE | Pulmonary Embolism |

| ROSC | Return of Spontaneous Circulation |

| TTE | Transthoracic Echocardiography |

| VA-ECMO | Venoarterial Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation |

| eCPR | Venoarterial Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation during CPR |

Appendix A

| Demographics | |

| Age (years) ± SD | 61,8 ± 15.3 |

| Sex (female) n (%) | 43 (54.4%) |

| Body Mass Index (Kg/m2) ± SD | 29.9 ± 7.7 |

| Past medical history | |

| Smoking n (%) | 32 (40.5) |

| Arterial hypertension, n (%) | 33 (41.8) |

| Dyslipidemia, n (%) | 29 (36.7) |

| History of cancer, n (%) | 16 (20.3) |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 11 (13.9) |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, n (%) | 9 (11.4) |

| Chronic renal disease, n (%) | 6 (7.6) |

| History of stroke, n (%) | 5 (6.3) |

| History of liver disease, n (%) | 3 (3.8) |

| Atrial fibrillation, n (%) | 3 (3.8) |

| Coronary artery disease, n (%) | 2 (2.5) |

| Previous myocardial infarction, n (%) | 2 (2.5) |

| Previous percutaneous coronary intervention, n (%) | 2 (2.5) |

| History of coagulopathy, n (%) | 1 (1.3) |

| History of platelet dysfunction, n (%) | 1 (1.3) |

| Chronic heart failure, n (%) | 1 (1.3) |

| Predisposing factors for venous thrombo-embolism | |

| Prolonged bed rest, n (%) | 19 (24.1) |

| Surgery 1-2 weeks previous (%) | 13 (16.5) |

| Immobilization, n (%) | 14 (17.7) |

| Hystory of thromboembolic disease, n (%) | 10 (12.7) |

| Active Cancer, n (%) | 9 (11.4) |

| Deep vein thrombosis, n (%) | 8 (10.1) |

| Hormonal contraceptives (%) | 4 (5.1) |

| Clinical Presentation | |

| Sudden Dyspnea, n (%) | 70 (88.6) |

| Cardiac arrest, n (%) | 40 (50.6) |

| Syncope, n (%) | 39 (49.4) |

| Cardiogenic shock, n (%) | 31 (39.2) |

| Chest pain, n (%) | 20 (25.3) |

| Fever, n (%) | 4 (5.1) |

| Hemoptysis, n (%) | 1 (1.3) |

| Cardiopulmonary resucitation, n (%) | 40 (50.6) |

| CPR duration (min), median [IQR] | 24 [9-43] |

| eCPR, n (%) | 3 (3.8) |

| Diagnostic tests | |

| CTPA, n (%) | 76 (96.2) |

| TTE at presentation, n(%) | 26 (32.9) |

| RV disfunction, n (%); n = 26 | 26 (100) |

| TAPSE [mm], (SD); n = 17 | 15.6 +- 9.6 |

| PASP [mmHg], (SD); n = 12 | 38 +- 29.9 |

| Intracavitary thrombus(%); n = 17 | 1 (5.6) |

| Treatment | |

| Un-fractioned Heparin, n(%) | 62 (78.5) |

| Argatroban, n(%) | 1(1.3) |

| Lepirudin, n(%) | 1(1.3) |

| Systemic thrombolysis, n(%) | 53 (67%) |

| Pre-hospital ST, n(%); n = 53 | 15 (28.3) |

| In-hospital ST, n(%); n = 53 | 38 (71.7) |

| Catheter directed therapies, n(%) | 28 (35.4) |

| Endovascular thrombectomy, n(%); n = 28 | 25 (89.3) |

| Catheter directed thrombolysis, n(%); n = 28 | 6(21.4) |

| Surgical embolectomy, n(%) | 1(1.3) |

| Support treatment | |

| Mechanical Ventilation, n(%) | 45 (58.4) |

| Norepinephrine, n(%) | 59 (74.7) |

| Epinephrine, n(%) | 23 (29.1) |

| Dobutamine, n(%) | 40 (50.6) |

| Vasopressin n(%) | 1 (1.3) |

| VA-ECMO n(%) | 9 (11.4) |

| Vital signs | |

| Systolic blood pressure [mmHg], median [IQR] | 115 [101-125] |

| Mean blood pressure [mmHg], median [IQR] | 77 [70-87] |

| Heart rate [beats per minute], median [IQR] | 90 [84-105] |

| SpO2/FiO2 ratio, ± SD | 316 ±108 |

| Outcomes | |

| Major bleeding*, n (%) | 20 (25.3) |

| Reperfusion failure, n (%) | 19 (24) |

| Stroke, n (%) | 4 (5.1) |

| Recurrent PE, n (%) | 5 (7.1) |

| Ventilator Associated Pneumonia, n (%) | 11 (13.9) |

| Multiorgan failure, n (%) | 18 (22.8) |

| Sepsis, n (%) | 9 (11.4) |

| Acute Kidney Injury, n(%) | 39 (49.4) |

| Renal replacement therapy, n(%) | 6 (7.6) |

| ICU LOS, days, median [IQR] | 5 [2-20] |

| LOS, days, median [IQR] | 13 [4-32] |

| 7- days mortality, n(%) | 22 (27.8) |

| 30-days mortality, n (%) | 27 (34.2) |

| 90- days mortality, n(%) | 29 (36.7) |

References

- Chopard, R.; Behr, J.; Vidoni, C.; Ecarnot, F.; Meneveau, N. An Update on the Management of Acute High-Risk Pulmonary Embolism. J Clin Med 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kobayashi, T.; Pugliese, S.; Sethi, S.S.; Parikh, S.A.; Goldberg, J.; Alkhafan, F.; Vitarello, C.; Rosenfield, K.; Lookstein, R.; Keeling, B.; et al. Contemporary Management and Outcomes of Patients With High-Risk Pulmonary Embolism. J Am Coll Cardiol 2024, 83, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Konstantinides, S. V.; Meyer, G.; Bueno, H.; Galié, N.; Gibbs, J.S.R.; Ageno, W.; Agewall, S.; Almeida, A.G.; Andreotti, F.; Barbato, E.; et al. 2019 ESC Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Acute Pulmonary Embolism Developed in Collaboration with the European Respiratory Society (ERS). Eur Heart J 2020, 41, 543–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pölkki, A.; Pekkarinen, P.T.; Hess, B.; Blaser, A.R.; Bachmann, K.F.; Lakbar, I.; Hollenberg, S.M.; Lobo, S.M.; Rezende, E.; Selander, T.; et al. Noradrenaline Dose Cutoffs to Characterise the Severity of Cardiovascular Failure: Data-Based Development and External Validation. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 2024, 68, 1400–1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaatz, S.; Ahmad, D.; Spyropoulos, A.C.; Schulman, S. Definition of Clinically Relevant Non-Major Bleeding in Studies of Anticoagulants in Atrial Fibrillation and Venous Thromboembolic Disease in Non-Surgical Patients: Communication from the SSC of the ISTH. Journal of Thrombosis and Haemostasis 2015, 13, 2119–2126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meneveau, N.; Séronde, M.-F.; Blonde, M.-C.; Legalery, P.; Didier-Petit, K.; Briand, F.; Caulfield, F.; Schiele, F.; Bernard, Y.; Bassand, J.-P. Management of Unsuccessful Thrombolysis in Acute Massive Pulmonary Embolism. Chest 2006, 129, 1043–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, B.W.; Schreiber, D.H.; Liu, G.; Briese, B.; Hiestand, B.; Slattery, D.; Kline, J.A.; Goldhaber, S.Z.; Pollack, C. V. Therapy and Outcomes in Massive Pulmonary Embolism from the Emergency Medicine Pulmonary Embolism in the Real World Registry. American Journal of Emergency Medicine 2012, 30, 1774–1781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calé, R.; Ascenção, R.; Bulhosa, C.; Pereira, H.; Borges, M.; Costa, J.; Caldeira, D. In-Hospital Mortality of High-Risk Pulmonary Embolism: A Nationwide Population-Based Cohort Study in Portugal from 2010 to 2018. Pulmonology 2024, 000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiménez, D.; Bikdeli, B.; Barrios, D.; Quezada, A.; Del Toro, J.; Vidal, G.; Mahé, I.; Quere, I.; Loring, M.; Yusen, R.D.; et al. Epidemiology, Patterns of Care and Mortality for Patients with Hemodynamically Unstable Acute Symptomatic Pulmonary Embolism. Int J Cardiol 2018, 269, 327–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vanni, S.; Socci, F.; Pepe, G.; Nazerian, P.; Viviani, G.; Baioni, M.; Conti, A.; Grifoni, S. High Plasma Lactate Levels Are Associated with Increased Risk of In-Hospital Mortality in Patients with Pulmonary Embolism. Academic Emergency Medicine 2011, 18, 830–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stadlbauer, A.; Verbelen, T.; Binzenhöfer, L.; Goslar, T.; Supady, A.; Spieth, P.M.; Noc, M.; Verstraete, A.; Hoffmann, S.; Schomaker, M.; et al. Management of High-Risk Acute Pulmonary Embolism: An Emulated Target Trial Analysis. Intensive Care Med 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Catastrophic PE n = 47 |

High-Risk PE n = 32 |

p value | |

| Demographics | |||

| Age [years], ± SD | 60.4 ± 16.5 | 63.8 ± 13.2 | 0.614 |

| Sex [male], n (%) | 19 (40.4) | 17 (53.1) | 0.077 |

| Body mass index [kg/m²], ± SD | 28.6 ± 6.2 | 31.7 ± 9 | 0.495 |

| Past medical history | |||

| Smoking, n (%) | 18 (38.3) | 14(47.8) | 0.815 |

| Arterial hypertension, n (%) | 16 (34) | 15 (53.12) | 0.108 |

| Dyslipidemia, n (%) | 14 (29.8) | 15 (46.9) | 0.156 |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 6 (12.8) | 5 (15.6) | 0.750 |

| History of stroke, n (%) | 2 (4.3) | 3 (9.4) | 0.475 |

| History of liver disease, n (%) | 1 (2.1) | 2 (6.3) | 0.383 |

| History of cancer, n (%) | 7(14.9) | 9 (28.1) | 0.167 |

| COPD, n (%) | 4 (8.5) | 5(13.5) | 0.473 |

| Atrial fibrillation, n (%) | 0 | 3 (9.4) | 0.063 |

| Chronic heart failure, n (%) | 0 | 1 (3.1) | 0.405 |

| Coronary artery disease, n (%) | 0 | 2 (6.3) | 0.161 |

| Chronic renal disease, n (%) | 4 (8.5) | 2 (6.3) | 0.533 |

| Predisposing factors for venous thrombo-embolism | |||

| Hormonal contraceptives (%) | 4 (8.5) | 0 | 0.140 |

| Surgery 1-2 weeks previous (%) | 7 (14.9) | 6 (18.8) | 0.764 |

| Prolonged bed rest, n (%) | 10 (21.3) | 9 (28.1) | 0.596 |

| Immobilization (%) | 7 (14.9) | 7 (21.9) | 0.552 |

| Hystory of thromboembolic disease (%) | 5(10.6) | 5 (15.6) | 0.540 |

| Active Cancer, n (%) | 3 (6.4) | 6 (18.8) | 0.149 |

| Clinical presentation | |||

| Sudden Dyspnea, n (%) | 40 (85.1) | 30 (93.75) | 1 |

| Syncope, n (%) | 29 (61.7) | 10 (31.3) | 0.005 |

| Chest pain, n (%) | 10 (21.3) | 10 (31.3) | 0.598 |

| Fever, n (%) | 0 | 4 (12.5) | 0.030 |

| Hemoptysis, n (%) | 0 | 1 (3.1) | 0.427 |

| Lung infarction, n (%) | 17 (36.2) | 7 (21.9) | 0.210 |

| Inferior Vena Cava Reflux, n(%) | 21 (44.7) | 17 (53.1) | 0.797 |

| Laboratory at admission | |||

| Lactate [mg/dl], median [IQR] | 74.9 [40.75-127.8] | 12.7 [8.2-22.7] | <0.001 |

| pH, median [IQR] | 7.238 [6.99-7.33] | 7.436 [7.36-7.47] | <0.001 |

| PaO2 [mmHg], median [IQR] | 113 [72.1-203.9] | 69.3 [51.6-88.9] | <0.001 |

| PaCO2 [mmHg], median [IQR] | 54.2 [42.4-74.8] | 35.6 [29.8-41] | <0.001 |

| Creatinine [mg/dl], mean (SD) | 1.54 [1.19-2.2] | 0.94 [0.66-1.26] | <0.001 |

| Bilirrubin [mg/dl], median [IQR] | 1 [0.5-1.6] | 0.8 [0.5-1] | 0.097 |

| AST [U/I], median [IQR] | 244.5 [110.3-681] | 28 [17.3-54.5] | <0.001 |

| ALT [U/I], median [IQR] | 242.5 [80.3-440.3] | 27.5[13-80.3] | <0.001 |

| GGT [U/I], median [IQR] | 95 [42-191] | 39 [22.8-67.3] | 0.002 |

| Hemoglobin [g/dl], median [IQR] | 12.9 [11.2-14.4] | 11.8 [10.4-13.3] | 0.148 |

| Leukocyte count [G/l], median [IQR] | 15 [10.4-20.6] | 12.7 [7.9-14.9] | 0.016 |

| Platelet count [G/l], median [IQR] | 176 [123-230.8] | 211 [174-290] | 0.07 |

| Fibrinogen [mg/dl], median [IQR] | 1.8 [0.5-3.5] | 4.5 [3.4-5.5] | 0.003 |

| aPTT [sec], median [IQR] | 46 [30.8-88.3] | 32.1 [25.2-36.9] | 0.001 |

| INR, median [IQR] | 1.58 [1.33 2.5] | 1.23 [1.12-1.32] | <0.001 |

| HS Troponin I | 1727.7 [3.7-3960] | 44.2 [1.03-392.4] | 0.011 |

| C-reactive protein [mg/dl], median [IQR] | 3.91 [1.4-10.5] | 5.27 [2.7-16.78] | 0.080 |

| Severity scoring systems at admission | |||

| SAPS II score, median [IQR] | 76 [60-90] | 30 [22-35.8] | <0.001 |

| SOFA score, median [IQR] | 11 [8-13] | 5 [3-6] | <0.001 |

| Supportive care | |||

| Mechanical Ventilation, n (%) | 38 (80.9) | 7 (21.9) | <0.001 |

| Noradrenaline, n (%) | 42 (89.4) | 17 (53.1) | <0.001 |

| Dobutamine, n(%) | 31 (66) | 9 (28.1) | 0.001 |

| Adrenaline, n (%) | 22 (46.8) | 1 (3.1) | <0.001 |

| Inferior Vena Cava Filter, n(%) | 9 (19.1) | 13 (40.6) | 0.122 |

| VA-ECMO, n(%) | 9 (19.1) | 0 | 0.009 |

| Treatment | |||

| Un-fractioned Heparin, n(%) | 36 (76.6) | 26 (81.3) | 1 |

| Systemic thrombolysis, n(%) | 39 (83) | 14 (43.8) | 0.001 |

| Alteplase, n(%) | 31 (66) | 10 (31.3) | 0.006 |

| Tenecteplase, n(%) | 7 (14.9) | 2 (6.3) | 0.300 |

| Catheter directed therapies, n(%) | 16 (34) | 12 (37.5) | 0.803 |

| Surgical embolectomy, n(%) | 1 (2.1) | 0 | 1 |

| Treatment sequence | |||

| Anticoagulation alone, n(%) | 3 (6.4) | 5 (15.6) | .001 |

| First line Systemic thrombolysis, n(%) | 38 (80.9) | 13 (40.6) | |

| First line Catheter directed Therapies, n(%) | 5 (10.6) | 14 (43.8) | |

| First line Surgical embolectomy, n(%) | 1 (2.1) | 0 | |

| Vital signs | |||

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg), median [IQR] | 90 [81.3-107] | 110 [91.5-126] | 0.006 |

| Mean blood pressure (mmHg), median [IQR] | 65 [59.5-76] | 76 [65-85] | 0.012 |

| Heart rate (bpm), median [IQR] | 102 [87.8-120] | 87 [85-110] | 0.029 |

| SpO2/FiO2 ratio, ± SD | 203 ± 83 | 260 ± 100 | 0.013 |

| Vital signs at 48hrs | |||

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg), median [IQR] | 104 [90-123] | 120 [111-125] | 0.014 |

| Mean blood pressure (mmHg), median [IQR] | 69 [65-81] | 78 [75-93] | 0.002 |

| Heart rate (bpm), median [IQR] | 100 [86-110] | 87 [82-97] | 0.015 |

| SpO2/FiO2 ratio, ± SD | 283 ± 119 | 344 ± 93 | 0.036 |

| Outcomes | |||

| Major bleeding*, n (%) | 14 (29.8) | 6 (18.8) | 0.194 |

| Stroke, n (%) | 4 (8.5) | 0 | 0.129 |

| Recurrent PE, n (%) | 1 (2.1) | 4 (12.5) | 0.159 |

| Ventilator Associated Pneumonia, n (%) | 6 (12.8) | 5 (15.6) | 1 |

| Multiorgan failure, n (%) | 16 (34) | 2 (6.3) | 0.002 |

| Sepsis, n (%) | 5 (10.6) | 4 (12.5) | 1 |

| Acute Kidney Injury, n(%) | 27 (57.4) | 12 (37.5) | 0.037 |

| Renal replacement therapy, n(%) | 5 (10.6) | 1 (3.1) | 0.231 |

| ICU LOS, days, median [IQR] | 6 [1-19.5] | 5 [4-22] | 0.302 |

| LOS, days, median [IQR] | 7 [1-36] | 15 [8.5-29.3] | 0.05 |

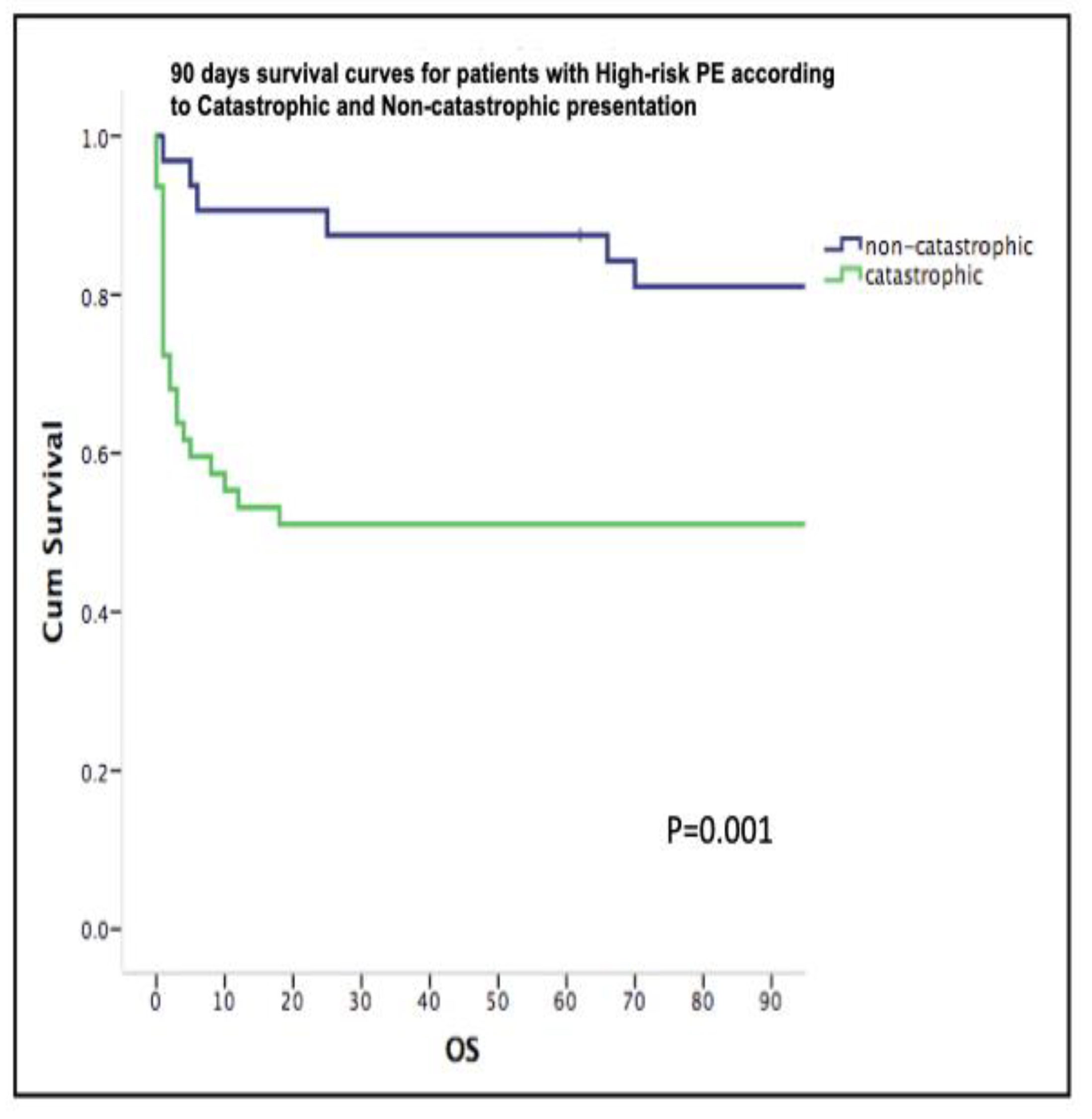

| 7 days mortality, n (%) | 19 (40.4) | 3 (9.4) | 0.002 |

| 30-days mortality, n (%) | 23 (48.9) | 4 (12.5) | 0.001 |

| 90-days mortality, n (%) | 23 (48.9) | 6 (18.8) | 0.009 |

| Reperfusion failure, n(%) | 16 (34) | 3 (9.4) | 0.015 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).