Submitted:

31 December 2024

Posted:

31 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

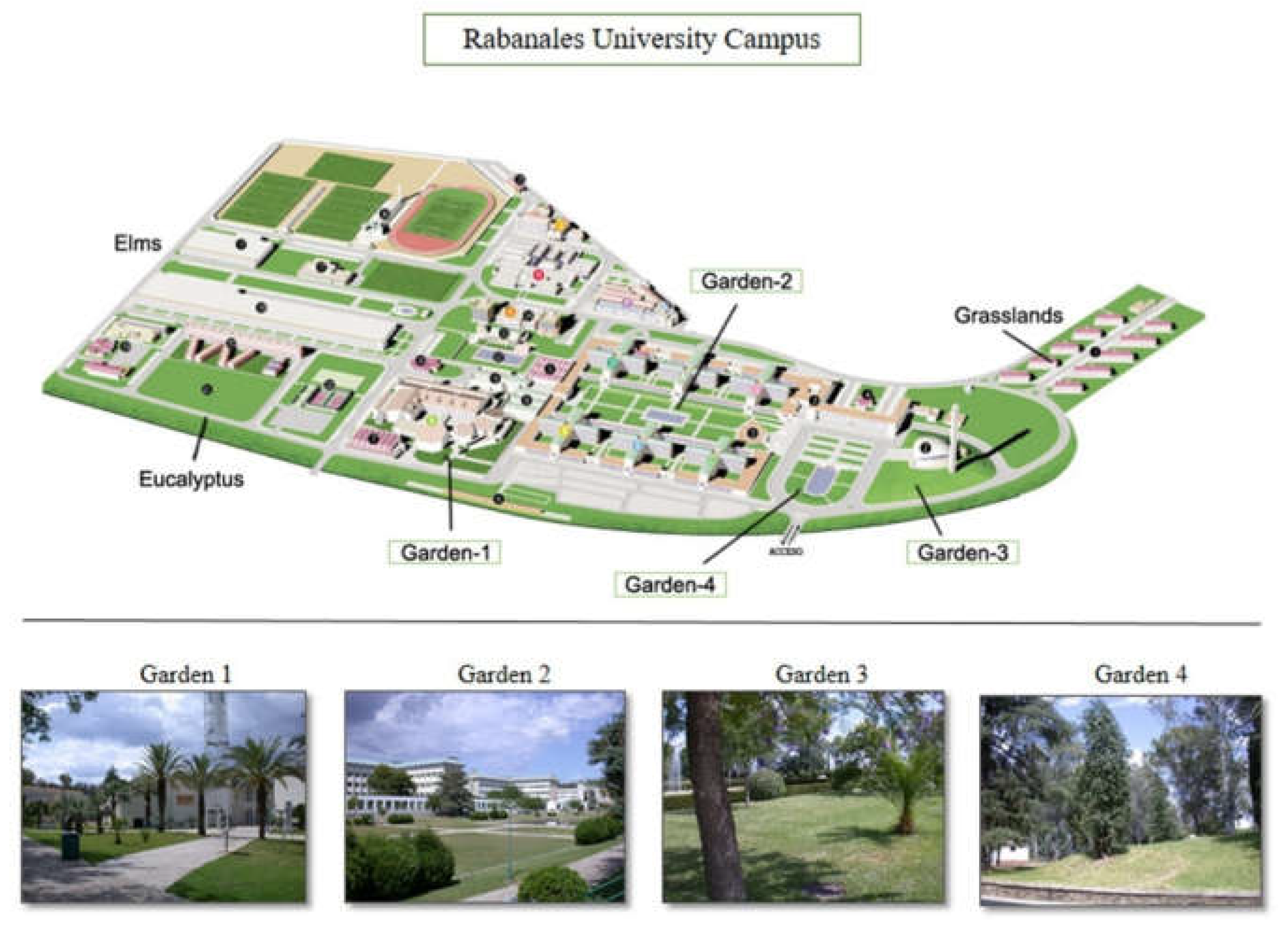

2.1. Study Areas

2.2. Sampling Method

2.3. Statistical Analyses

2.3.1. Comparing Ant Communities Among Campus Habitats

2.3.2. Species-Habitat Association

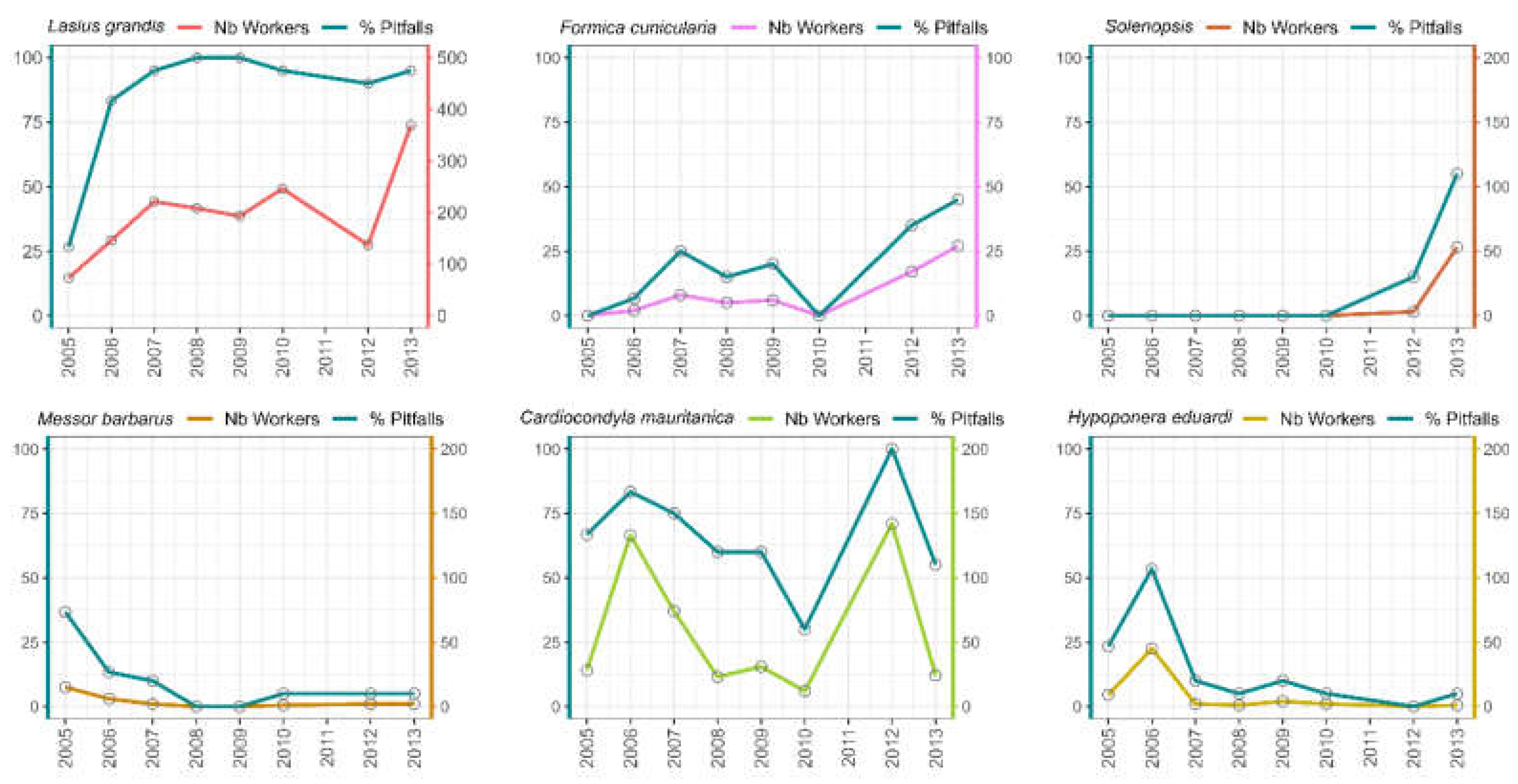

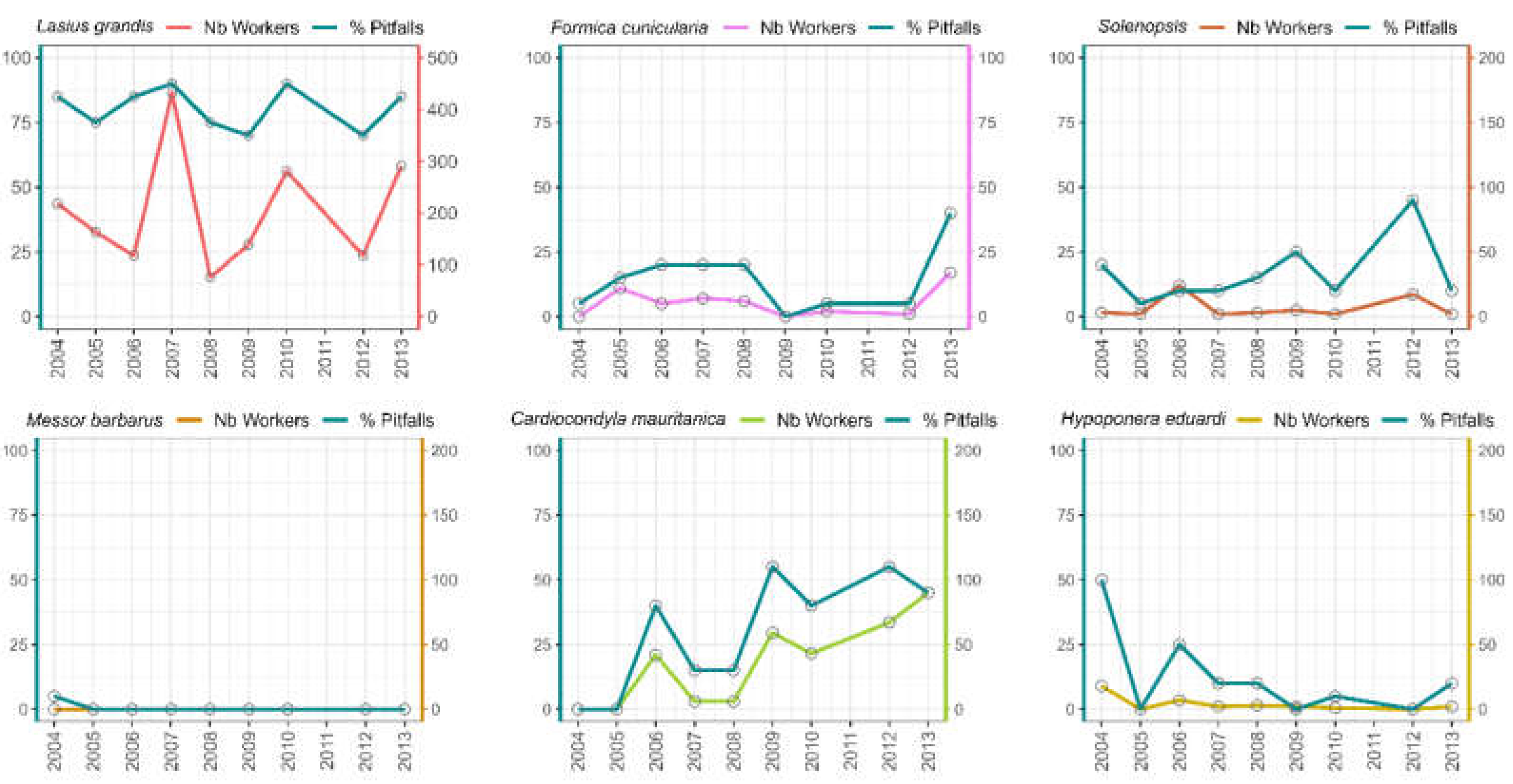

2.3.3. Species Population Dynamic over the Years

3. Results

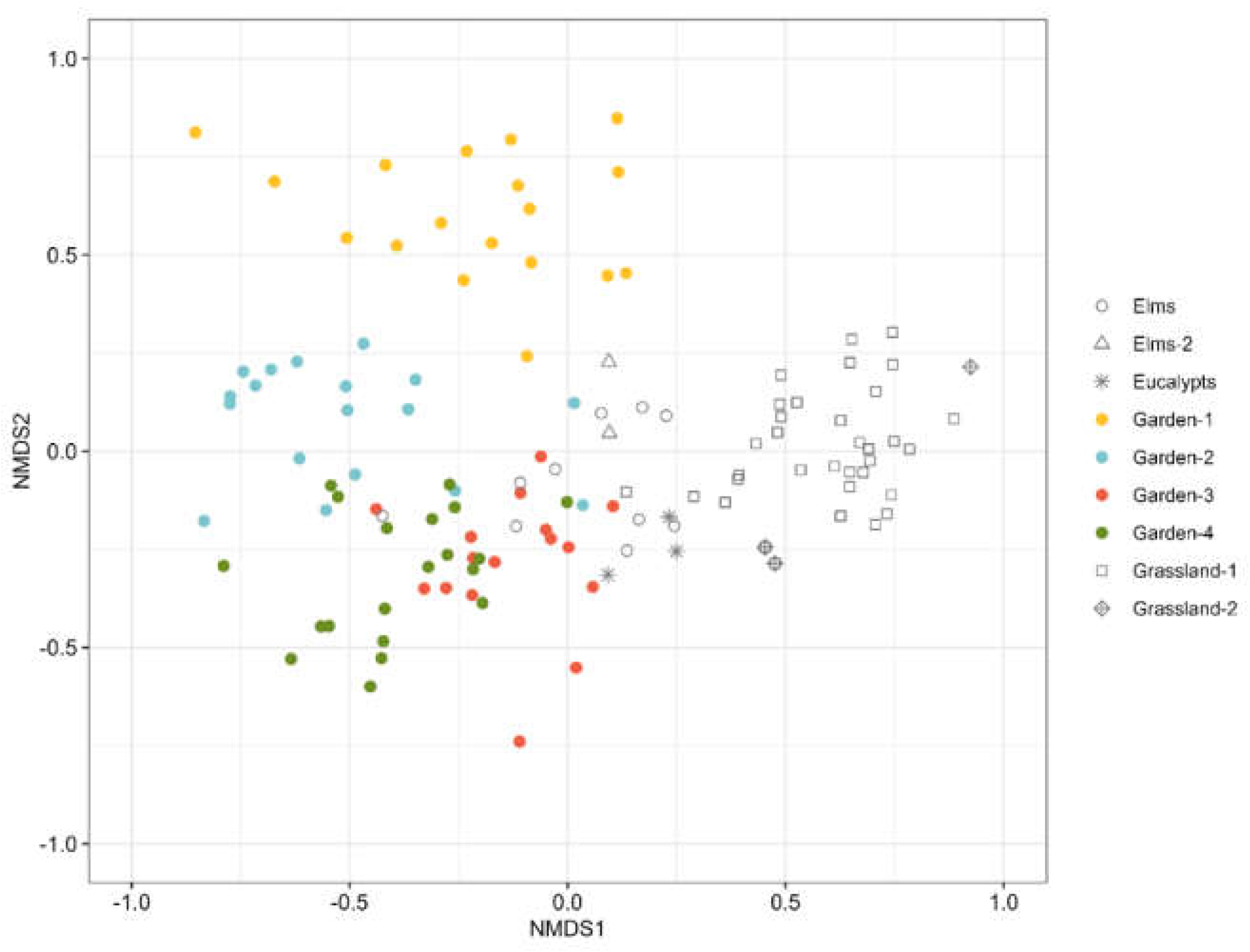

3.1. Comparing ant Communities Among Campus Habitats

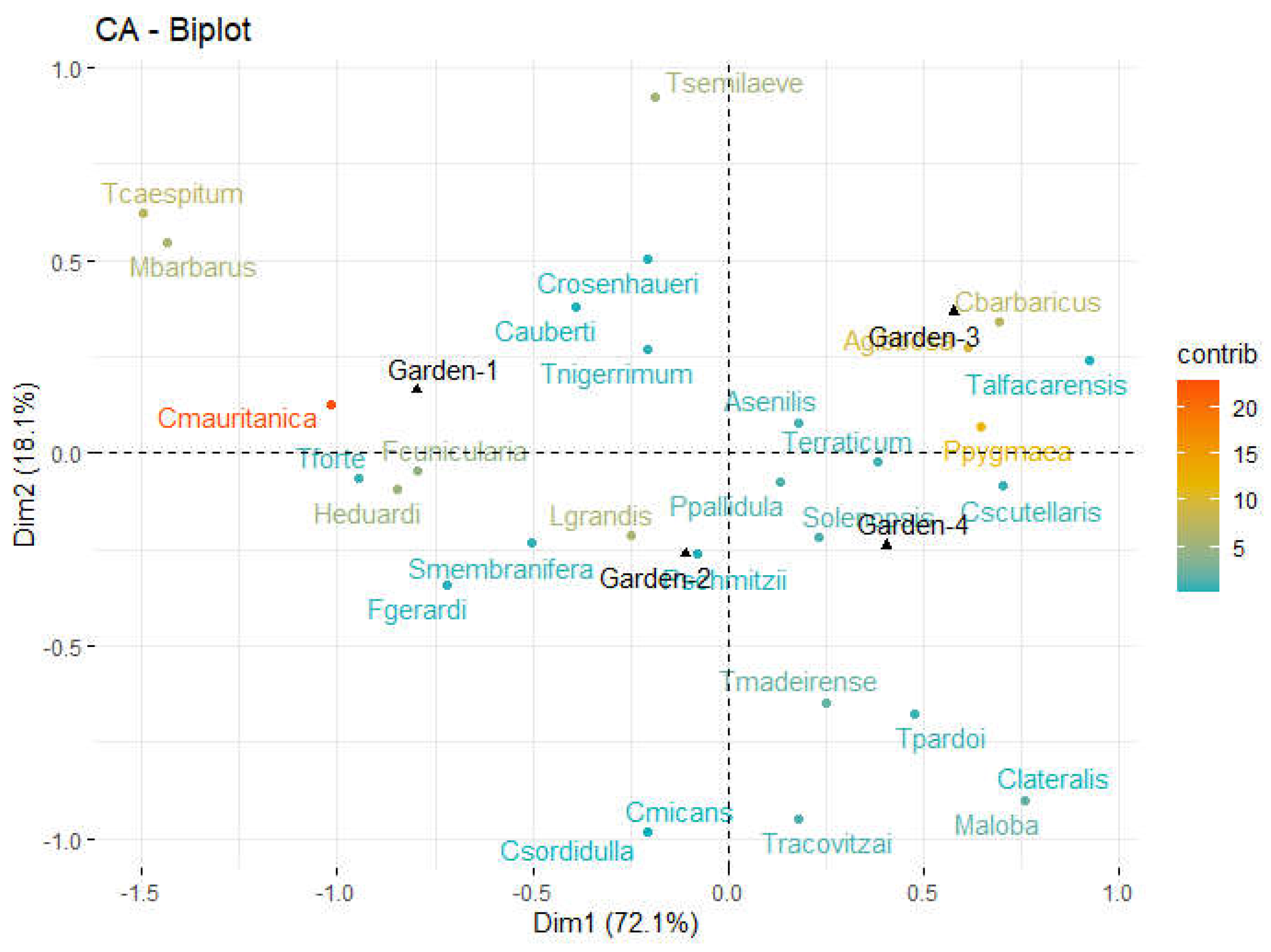

3.2. Species-Habitat Association

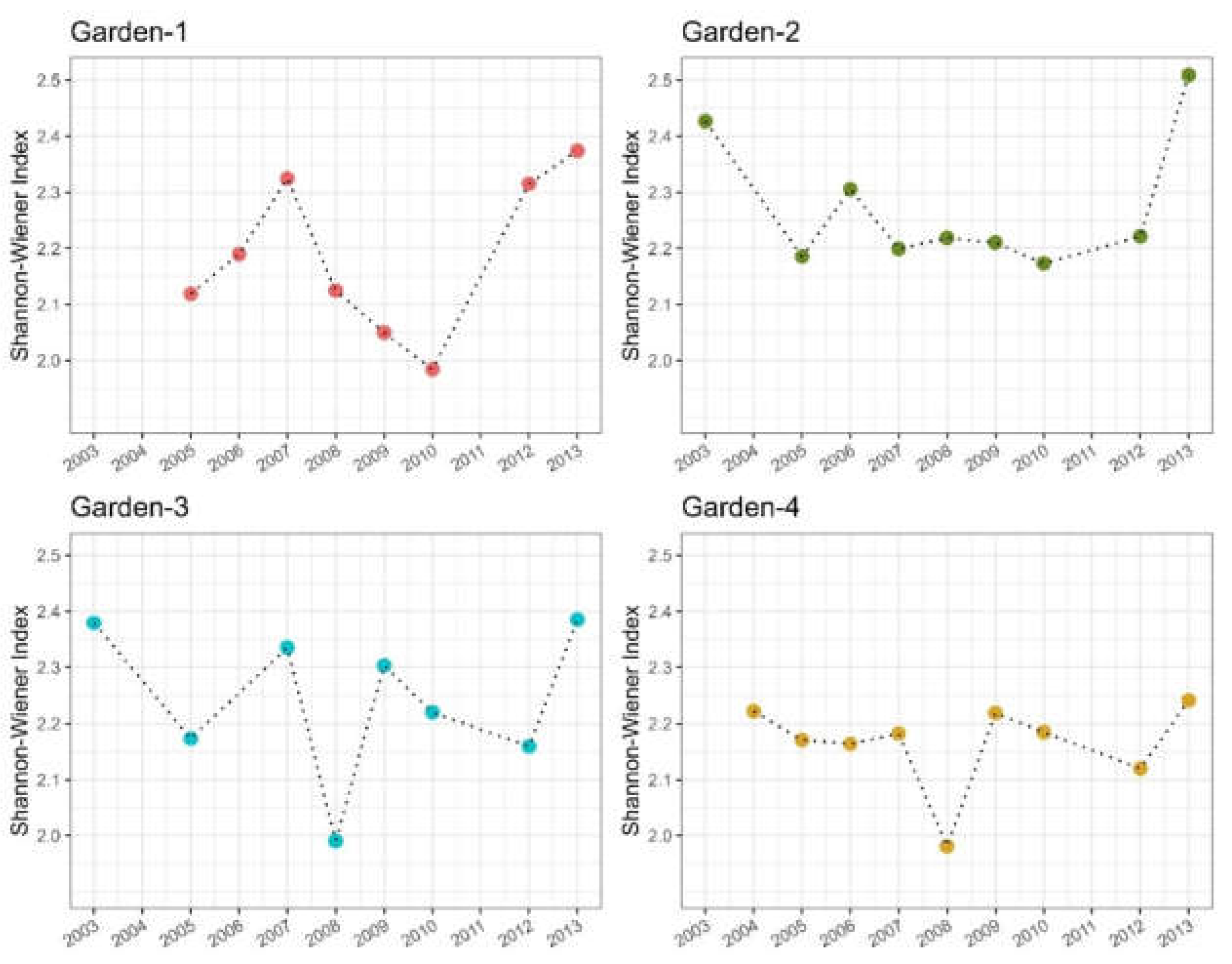

3.3. Relationship Between Species Abundance and Habitat Maturity

4. Discussion

Appendix A

References

- Szulkin, M.; Munshi-South, J.; Chamantier, A. Urban evolutionary biology. Oxford University Press, USA, 2020.

- Rega-Brodsky, C.C.; Aronson, M.F.J.; Piana, M.R.; et al. Urban biodiversity: State of the science and future directions. Urban Ecosystems 2022, 25, 1083–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trigos-Peral, G.; Maák, I.; Schmid, S.; Chodzik, P.; Czaczkes, T.J.; Witek, M.; Casacci, L.P.; Sánchez-Garcia, D.; Lörincz, A.; Kochanowski, M.; Heinze, J. Urban abiotic stressors drive changes in the foraging activity and colony growth of the black garden ant Lasius niger. Science of The Total Environment 2024, 915, 170157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, M.T.J.; Munshi-South, J. Evolution of life in urban environments. Science 2017, 358(6363), eaam8327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lososová, Z.; Chytrý, M.; Tichý, L.; Danihelka, J.; Fajmon. K.; Hájek, O.; Kintrová, K.; Láníková, D.; Otýpková, Z.; Řehořek, V. Biotic homogenization of Central European urban floras depends on residence time of alien species and habitat types. Biological Conservation 2012, 145, 179–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brassard, F.; Leong, C.M.; Chan, H.H.; Guénard, B. High Diversity in Urban Areas: How Comprehensive Sampling Reveals High Ant Species Richness within One of the Most Urbanized Regions of the World. Diversity 2021, 13(8), 358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langemeyer, J.; Gómez-Baggethun, E. Urban biodiversity and ecosystem services. In: Ossola, A., Niemelä, J. (Eds) Urban Biodiversity – From Research to Practice. Routledge, Oxon and New York, pp 36–53, 2018. 2018.

- Guénard, B.; Cardinal-De Casas, A.; Dunn, R.R. High diversity in an urban habitat: are some animal assemblages resilient to long-term anthropogenic change? Urban Ecosystems 2015, 18, 449–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menke, S.B.; Guénard, B.; Sexton, J.O.; Weiser, M.D.; Dunn, R.R.; Silverman, J. Urban areas may serve as habitat and corridors for dry-adapted, heat tolerant species; an example from ants. Urban Ecosystems 2011, 14, 135–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trigos-Peral, G.; Rutkowski, T.; Witek, M.; Ślipiński, P.; Babik, H.; Czechowski, W. Three categories of urban green areas and the effect of their different management on the communities of ants, spiders and harvestmen. Urban Ecosystems 2020, 23, 803–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes-López, J.L.; Carpintero, S. Comparison of the exotic and native ant communities (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) in urban green areas at inland, coastal and insular sites in Spain. European Journal of Entomology 2014, 111(3), 421–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ślipiński, P.; Zmihorski, M.; Czechowski, W. Species Diversity and nestedness of Ant Assemblages in an Urban Environment. European Journal of Entomology 2012, 109, 197–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llewellyn, T.; Gaya, E.; Murrell, D.J. Are Urban Communities in successional Stasis? A Case Study on Epiphytic Lichen Communities. Diversity 2020, 12(9), 330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vepsäläinen, K.; Ikonen, H.; Koivula, M.J. The structure of ant assemblages in an urban area of Helsinki, southern Finland. Annales Zoologici Fennici 2008, 45(2), 109–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gliessman, S.R. Agroecology: The Ecology of Sustainable Food Systems, 3rd ed.; CRC Press/Taylor & Francis: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- King, J.R.; Andersen, A.N.; Cutter, A.D. Ants as bioindicators of habitat disturbance: validation of the functional group model for Australia's humid tropics. Biodiversity Conservation 1998, 7, 1627–1638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, A.N.; Hoffmann, B.D.; Müller, W.J.; Griffiths, A.D. Using ants as bioindicators in land management> simplifying assessment of ant community responses. Journal of Applied Ecology 2002, 39, 8–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, A.N.; Majer, J.D. Ants show the way Down Under: Invertebrates as bioindicators in land management. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment 2004, 2, 291–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanov, K.; Keiper, J. Ant (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) diversity and community composition along sharp urban forest edges. Biodiversity Conservation 2010, 19, 3917–3933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buczkowski, G.; Richmond, D.S. The effect of urbanization on ant abundance and diversity: A temporal examination of factors affecting biodiversity. PLoS ONE 2012, 7(8), e41729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Czechowski, W.; Radchenko, A.; Czechowska, W.; Vepsäläinen, K. The ants of Poland with reference to the myrmecofauna of Europe. Fauna Polonia 4. Natura Optima Dux Foundation, Warsaw, 2012.

- Roig, X.; Espadaler, X. Propuesta de grupos funcionales de hormigas para la Península Ibérica y Baleares, y su uso como bioindicadores Proposal of functional groups of ants for the Iberian Peninsula and Balearic Islands, and their use as bioindicators. Iberomyrmex 2010, 2, 28–29. [Google Scholar]

- Andersen, A.N. A classification of Australian ant communities, based on functional groups which parallel plant life-forms in relation to stress and disturbance. Journal of Biogeography 1995, 22, 15–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnán, X.; Cerdá, X.; Retana, J. Partitioning the impact of environment and spatial structure on alpha and beta components of taxonomic, functional, and phylogenetic diversity in European ants. PeerJ 2015, 3, e1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabrero-Sañudo, F.J.; Cañizares García, R.; Caro-Miralles, E.; Gil-Tapetado, D.; Grzechnik, S.; López-Collar, D. Seguimiento de artrópodos bioindicadores en áreas urbanas: objetivos, experiencias y perspectivas. Ecosistemas 2022, 31(1), 2340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- arpintero, S.; Reyes-López, J.L. Effect of park age, size, shape and insolation on ant assemblages in two cities of. Southern Spain. Entomological Science 2014, 17, 41–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miguelena, G.J.; Baker, P.B. Effects of urbanization on the diversity, abundance, and composition of ant assemblages in an arid city. Environmental Entomology 2019, 48(4), 836–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tinaut Ranera, J.A. Estudio de los formícidos de Sierra Nevada. Ph.D. Thesis, . Universidad de Granada, Granada, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria, 2010. https://www.R-project.org/.

- Oksanen, J.; Simpson, G.L.; Guillaume Blanchet, F.; Kindt, R.; Legendre, P.; et al. vegan: Community Ecology package. R package version 2.0-10., 2024. Available at: http://CRAN.R-project.org/ package=vegan.

- Dufrêne, M.; Legendre, P. Species assemblages and indicator species: The need for a flexible asymmetrical approach. Ecological Monographs 1997, 67(3), 345–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Cáceres, M.; Legendre, P. Associations between species and groups of sites: indices and statistical inference. Ecology 2009, 90, 3566–3574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lê, S.; Josse, J.; Husson, F. FactoMineR: An R Package for Multivariate Analysis. Journal of Statistical Software 2008, 25(1), 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassambara, A.; Mundt, F. factoextra: Extract and Visualize the Results of Multivariate Data Analyses. R package version 1.0.5., 2020. Available at: https://CRAN.R-roject.org/package=factoextra.

- Wetterer, J.K. Worldwide Spread of the Moorish Sneaking Ant, Cardiocondyla mauritanica (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Sociobiology 2012, 59(3), 985–997. [Google Scholar]

- Taheri, A.; Wetterer, J.K.; Reyes-López, J. Tramp ants of Tangier, Morocco. Transactions of the American Entomological Society 2017, 143(2), 299–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hölldobler, B.; Wilson, E.O. The Ants. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1990.

- Jiménez-Carmona, F.; Heredia-Arévalo, A.M.; Reyes-López, J.L. Ants (hymenoptera: formicidae) as an indicator group of human environmental impact in the riparian forests of the Guadalquivir river (Andalusia, Spain). Ecological Indicators 2020, 118, 106762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lőrincz, Á.; Habenczyus, A.A.; Kelemen, A.; Ratkai, B.; Tölgyesi, C.; Lőrinczi, G.; Frei, K.; Bátori, Z.; Maák, I.E. Wood-pastures promote environmental and ecological heterogeneity on a small spatial scale. Science of The Total Environment 2024, 906, 167510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKinney, M.L. Urbanization as a Major Cause of Biotic Homogenization. Biological Conservation 2006, 127, 247–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKinney, M.L. Effects of urbanization on species richness: A review of plants and animals. Urban Ecosystems 2008, 11, 161–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearson, D.E.; Ortega, Y.K.; Eren, Ö.; Villareal, D.; Lekberg, Y.; Hierro, J. Exotic success following disturbance explained by weak native resilience and ruderal exotic bias. Journal of Ecology 2023, 111, 2412–2423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotton, J. Diversity, abundance, and species composition of ants in urban green spaces. Urban Ecosystems 2010, 13, 25–441. [Google Scholar]

- Stukalyuk, S.; Maák, I.E. The influence of illumination regimes on the structure of ant (Hymenoptera, Formicidae) community composition in urban habitats. Insectes Sociaux 2023, 70, 423–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penick, C.A.; Savage, A.M.; Dunn, R.R. Stable isotopes reveal links between human food inputs and urban ant diets. Proceedings of the Royal Society B-Biological Sciences 2015, 282, art 20142608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trigos-Peral, G.; Witek, M.; Csata, E.; Chudzik, P.; Heinze, J. Urban diet as potential cause of low body fat content in female ant sexuals. Myrmecological News 2024b, 34, 181–190. [Google Scholar]

- Gaber, H.; Ruland, F.; Jeschke, J.; Bernard-Verdier, M. Behavioural changes in the city: The common black garden ant defends aphids more aggressively in urban environments. Ecology and Evolution 2024, 4, e11639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vidal-Cordero, J.M.; Angulo, E.; Molina, F.P.; Boulay, R.; Cerdá, X. Long-term recovery of Mediterranean ant and bee communities after fire in southern Spain. Science of the Total Environment 2023, 887, 164132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zina, V.; Ordeix, M.; Franco, J.C.; Ferreira, M.T.; Fernandes, M.R. Ants as Bioindicators of Riparian Ecological Health in Catalonian Rivers. Forests 2021, 12, 625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gollan, J.R.; Lobry de Bruyn, L.; Reid, N.; Smith, D.; Wilkie, L. Can ants be used as ecological indicators of restoration progress in dynamic environments? A case study in a revegetated riparian zone. Ecological Indicators 2011, 11(6), 1517–1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, J.G.; Summerville, K.S.; Brown, R.L. Habitat associations of ant species (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) in a heterogeneous Mississippi landscape. Environmental Entomology 2008, 37(2), 453–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wetterer, J.K.; Espadaler, X.; Wetterer, A.L.; Cabral, S.G.M. Native and exotic ants of the Azores (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Sociobiology 2004, 44, 265–297. [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi, T. Influence of urbanization on ant distribution in parks of Tokyo and Chiba City, Japan I. Analysis of ant species richness. Ecological Research 2004, 19, 209–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, K.M.; Fisher, B.L.; LeBuhn, G. The influence of urban park characteristics on ant (Hymenoptera, Formicidae) communities. Urban Ecosystems 2008, 11, 317–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radchenko, A.G. , Elmes, G.W. Myrmica ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) of the Old World. Fauna Mundi 3, 2010.

| Species | Garden-1 | Garden-2 | Garden-3 | Garden-4 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aphaenogaster gibbosa (Latreille, 1798) | 14 | 11 | 80 | 56 | 161 |

| Aphaenogaster senilis Mayr, 1853 | 31 | 48 | 54 | 44 | 177 |

| Camponotus barbaricus Emery, 1905 | 0 | 21 | 55 | 16 | 92 |

| Camponotus lateralis (Olivier, 1792) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Camponotus micans (Nylander, 1856) | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Cardiocondyla mauritanica Forel, 1890 | 107 | 53 | 3 | 5 | 168 |

| Cataglyphis rosenhaueri Santschi, 1925 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 6 |

| Crematogaster auberti Emery, 1869 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 6 |

| Crematogaster scutellaris (Olivier, 1792) | 0 | 2 | 4 | 5 | 11 |

| Crematogaster sordidula (Nylander, 1849) | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Formica cunicularia Latreille, 1798 | 30 | 25 | 3 | 0 | 58 |

| Formica gerardi Bondroit 1917 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 5 |

| Hypoponera eduardi (Forel, 1894) | 26 | 20 | 1 | 1 | 48 |

| Lasius grandis Forel, 1909 | 141 | 137 | 38 | 107 | 423 |

| Messor barbarus Linnaeus, 1767 | 18 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 18 |

| Myrmica aloba Forel, 1909 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 10 |

| Pheidole pallidula (Nylander, 1849) | 79 | 100 | 100 | 127 | 406 |

| Plagiolepis pygmaea (Latreille, 1798) | 1 | 56 | 98 | 64 | 219 |

| Plagiolepis schmitzii Forel, 1895 | 8 | 15 | 6 | 6 | 35 |

| Solenopsis sp cfr | 14 | 29 | 21 | 33 | 97 |

| Strumigenys membranifera (Emery, 1869) | 5 | 7 | 1 | 0 | 13 |

| Tapinoma erraticum (Latreille, 1798) | 4 | 13 | 14 | 14 | 45 |

| Tapinoma madeirense Forel, 1895 | 1 | 18 | 4 | 12 | 35 |

| Tapinoma nigerrimum group (Nylander, 1856) | 13 | 8 | 8 | 4 | 33 |

| Temnothorax alfacarensis Tinaut & Reyes-López, 2020 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Temnothorax pardoi Tinaut, 1987 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 4 | 8 |

| Temnothorax racovitzai Bondroit, 1918 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 4 | 10 |

| Tetramorium caespitum (Linnaeus, 1758) | 23 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 23 |

| Tetramorium forte Forel, 1904 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 5 |

| Tetramorium semilaeve André, 1883 | 23 | 1 | 22 | 1 | 47 |

| Species | Greenery Category | Indicator Value (%) | P | |

| Lasius grandis | Garden | 85,1 | 0,001 | |

| Pheidole pallidula | Garden | 79,2 | 0,001 | |

| Cardiocondyla mauritanica | Garden | 70,7 | 0,001 | |

| Plagiolepis pygmaea | Garden | 69,3 | 0,002 | |

| Solenopsis spp. | Garden | 63,9 | 0,021 | |

| Formica cunicularia | Garden | 56,5 | 0,001 | |

| Hypoponera eduardi | Garden | 54,9 | 0,001 | |

| Tapinoma erraticum | Garden | 52,8 | 0,013 | |

| Strumigenys membranifera | Garden | 40,8 | 0,005 | |

| Temnothorax pardoi | Garden | 35,4 | 0,015 | |

| Messor barbarus | Natural/Seminatural | 87,9 | 0,001 | |

| Plagiolepis shcmitzii | Natural/Seminatural | 79,1 | 0,001 | |

| Tetramorium semilaeve | Natural/Seminatural | 77,2 | 0,001 | |

| Aphaenogaster gibbosa | Natural/Seminatural | 76,4 | 0,001 | |

| Aphaenogaster senilis | Natural/Seminatural | 76,2 | 0,001 | |

| Tapinoma nigerrimum | Natural/Seminatural | 70,4 | 0,001 | |

| Crematogaster auberti | Natural/Seminatural | 64,2 | 0,001 | |

| Temnothorax tyndalei | Natural/Seminatural | 57,2 | 0,001 | |

| Temnothorax alfacarensis | Natural/Seminatural | 54,9 | 0,001 | |

| Camponotus micans | Natural/Seminatural | 54,3 | 0,001 | |

| Cataglyphis velox | Natural/Seminatural | 51,9 | 0,001 | |

| Cataglyphis rosenhaueri | Natural/Seminatural | 45,3 | 0,009 | |

| Camponotus pilicornis | Natural/Seminatural | 43,9 | 0,001 | |

| Tetramorium forte | Natural/Seminatural | 41,2 | 0,025 | |

| Goniomma hispanicum | Natural/Seminatural | 36,7 | 0,003 | |

| Messor celiae | Natural/Seminatural | 31 | 0,011 | |

| (a) Gardens vs natural/seminatural areas | ||||

| Species | Maturity status | Indicator Value (%) | P | |

| Cardiocondyla mauritanica | 0 | 73,9 | 0,001 | |

| Messor barbarus | 0 | 71,1 | 0,001 | |

| Hypoponera eduardi | 0 | 60,3 | 0,001 | |

| Tetramorium semilaeve | 0 | 57,2 | 0,007 | |

| Tetramorium caespitum | 0 | 52,7 | 0,002 | |

| Plagiolepis pygmaea | 1 | 68,8 | 0,001 | |

| Solenopsis spp | 1 | 61.5 | 0,027 | |

| Formica cunicularia | 1 | 59,6 | 0,002 | |

| Strumigenys membranifera | 1 | 50,9 | 0,024 | |

| Temnothorax racovitzai | 1 | 44,5 | 0,025 | |

| Aphaennogaster gibbosa | 2 | 74,7 | 0,001 | |

| Camponotus barbarus | 2 | 62,5 | 0,006 | |

| Myrmica aloba | 2 | 37,3 | 0,045 | |

| (b)Young garden (maturity status = 0) vs mature gardens (unwatered, maturity status = 1; watered, maturity status = 2). | ||||

| Garden-1 | Garden-2 | Garden-3 | Garden-4 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Species | z | p | z | p | z | p | z | p | |

| Number of workers | L. grandis | 2,57 | 0,01 | 0,20 | 0,838 | 1,07 | 0,284 | -1,03 | 0,305 |

| F. cunicularia | 2,82 | 0,005 | 0,48 | 0,634 | 0 | 1 | - | - | |

| Solenopsis spp | 2,57 | 0,024 | 0,13 | 0,896 | -0,53 | 0,598 | 0,43 | 0,664 | |

| C. mauritanica | -0,8 | 0,936 | 2,59 | 0,009 | 1,18 | 0,237 | -3,23 | 0,001 | |

| H. eduardi | -3,14 | 0,002 | -2,39 | 0,017 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| M. barbarus | -1,84 | 0,06 | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| Number of pitfalls | L. grandis | 2,27 | 0,024 | -0,05 | 0,957 | -0,74 | 0,459 | -1,42 | 0,157 |

| F. cunicularia | 2,72 | 0,05 | 0,83 | 0,404 | 0,002 | 0,998 | - | - | |

| Solenopsis spp | 2,86 | 0,004 | 1,19 | 0,232 | -1,83 | 0,06 | 1,58 | 0,113 | |

| C. mauritanica | -0,44 | 0,659 | 2,90 | 0,004 | 0,88 | 0,381 | 0,82 | 0,413 | |

| H. eduardi | -3,11 | 0,002 | -2,05 | 0,041 | 0,001 | 0,999 | -0,001 | 0,999 | |

| M. barbarus | -2,69 | 0,007 | - | - | -- | - | - | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).