Submitted:

31 December 2024

Posted:

02 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

In this present study, we aim to investigate the effects of adding tea polyphenols to feed on the immunity, antioxidant capacity, and gut microbiota of weaned lambs. Thirty weaned lambs (2 month old, average initial weight 9.32 ± 1.72 kg) were randomly divided into five groups with six lambs in each group. The goat kids were randomly divided into four groups: a control group (CON) fed the basal diet, and four other groups supplemented with 2, 4, 6 g/kg tea polyphenols and 50 mg/kg chlortetracycline in the basal diet (denoted as T1, T2, T3 and CTC groups, respectively). The results indicate that adding 4-6 g/kg tea polyphenols can raise the expression levels of antioxidant enzymes and their genes in lambs' intestines. It also increases the expression of Nrf2, iNOS, and IL-10, while reducing the levels and gene expression of cytokines (IL-1β, IL-6, IFN-γ, and TNF-α) (P<0.05). At the same time, it reduced the expression levels of signaling pathways TLR4, MyD88, and NFκB (P<0.05) activated intestinal protective mechanisms, and enhanced the immune defense of intestinal epithelium. Compared with other groups, feeding tea polyphenols significantly increased the acetic acid content in the cecum of lambs (P<0.05), effectively promoting intestinal health. Tea polyphenols significantly increase the Shannon and Simpson indices, boost the abundance of Verrucomicrobiota, and reduce that of Proteobacteria and Firmicutes (P<0.05). The relative abundance of Candidatus_Soleaferrea, Christensenellaceae R-7 group, and Prevotella in the tea polyphenol group is significantly higher than in the chlortetracycline group (P<0.05). Overall, these results indicate that tea polyphenols can effectively maintain the homeostasis of the gut microbiota and have anti-inflammatory and antioxidant effects similar to antibiotics.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Lambs and Experimental Protocol

2.3. Sample Collection

2.4. Determination of Serum Antioxidant Indicators

2.5. Determination of Intestinal Immune Indicators

2.6. RT-qPCR Analysis

2.7. Determination of Volatile Fatty Acids

2.8. DNA Extraction

2.10. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Effects of Tea Polyphenols on Serum Antioxidant Capacity of Weaned Lambs

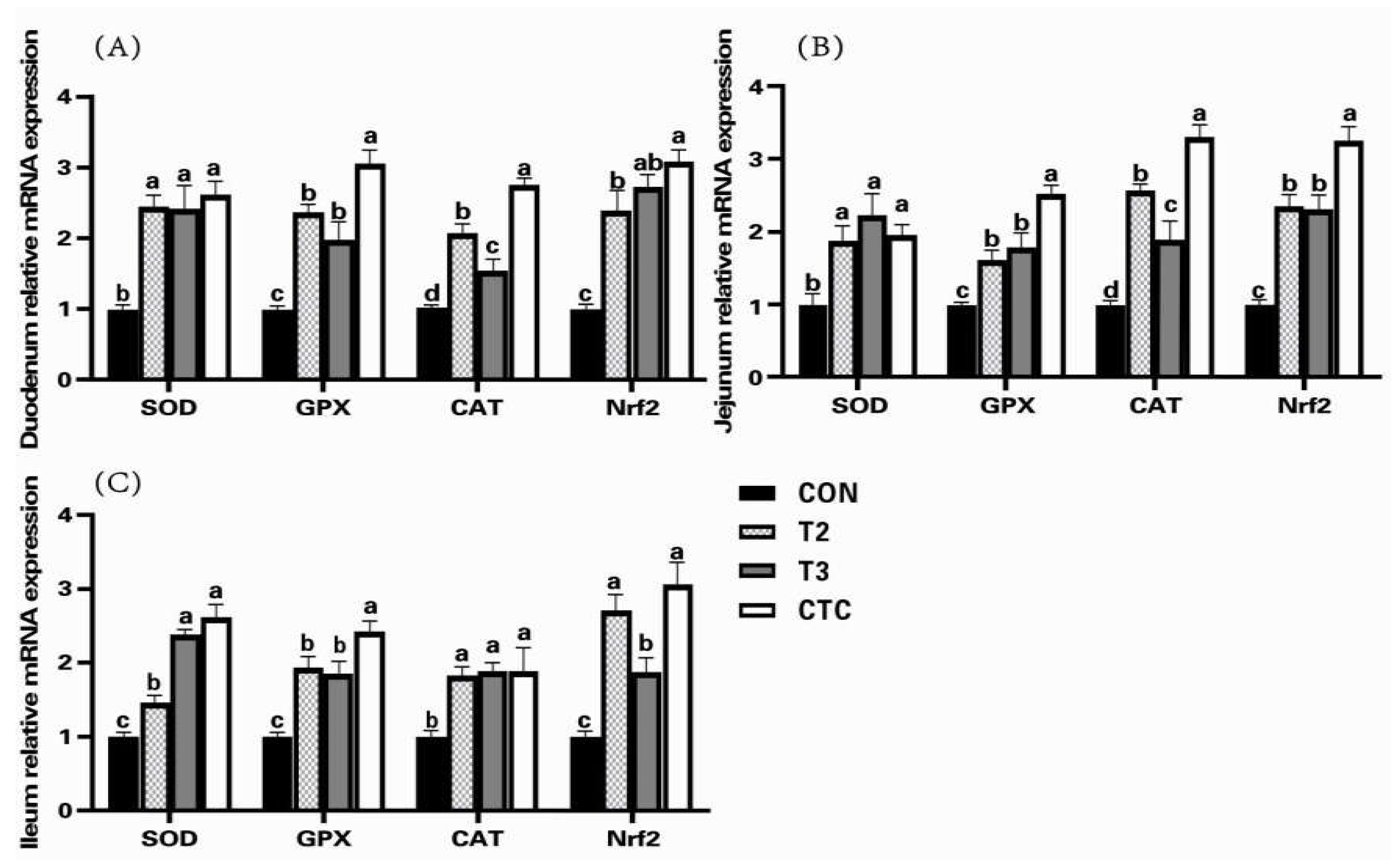

3.2. Effects of Tea Polyphenols on the Expression of Antioxidant Genes in the Intestines of Weaned Lambs

3.3. Effects of Tea Polyphenols on Intestinal Immune in Weaned Lambs

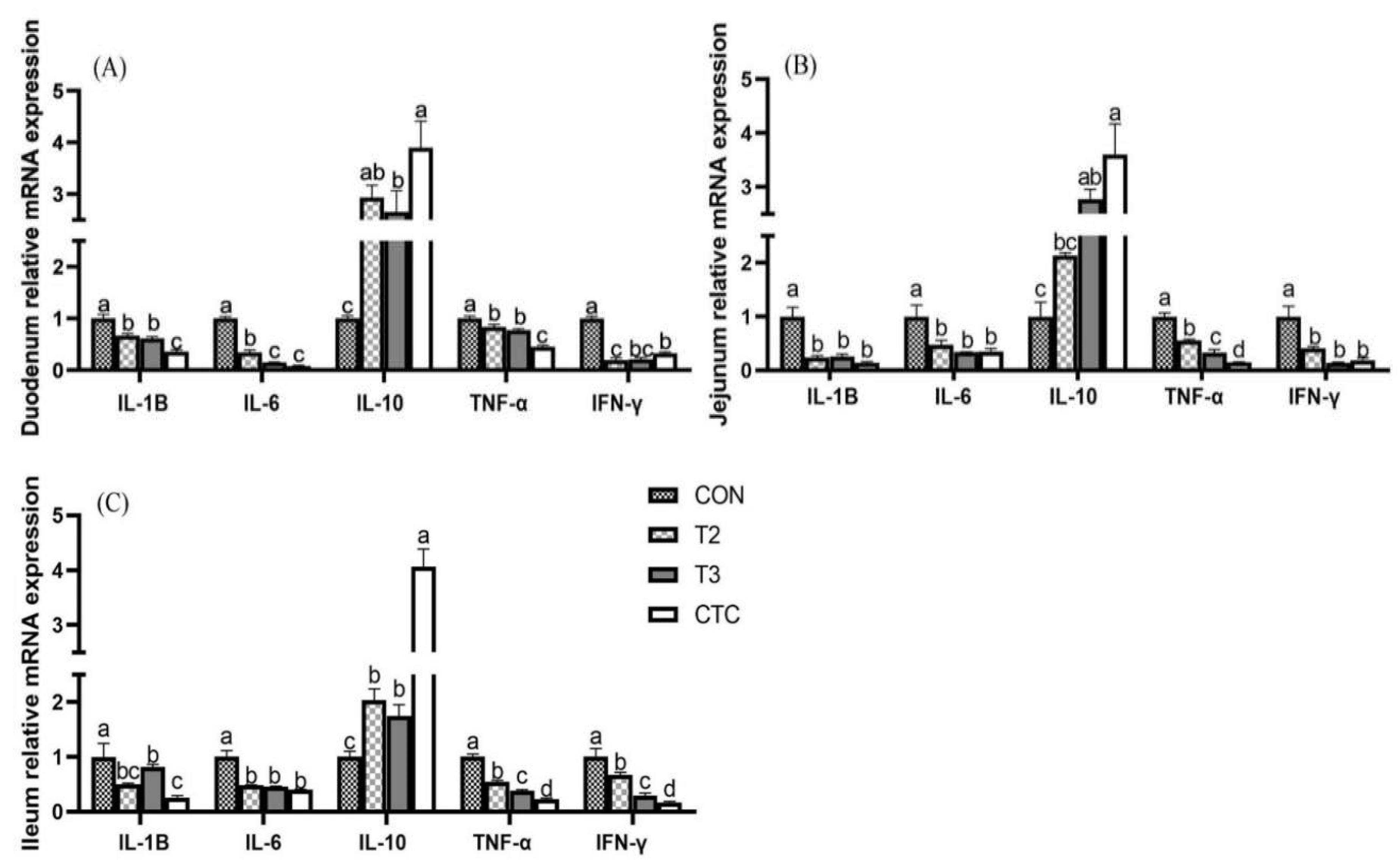

3.4. Effects of Tea Polyphenols on the Expression of Cytokine Genes in the Intestines of Weaned Lambs

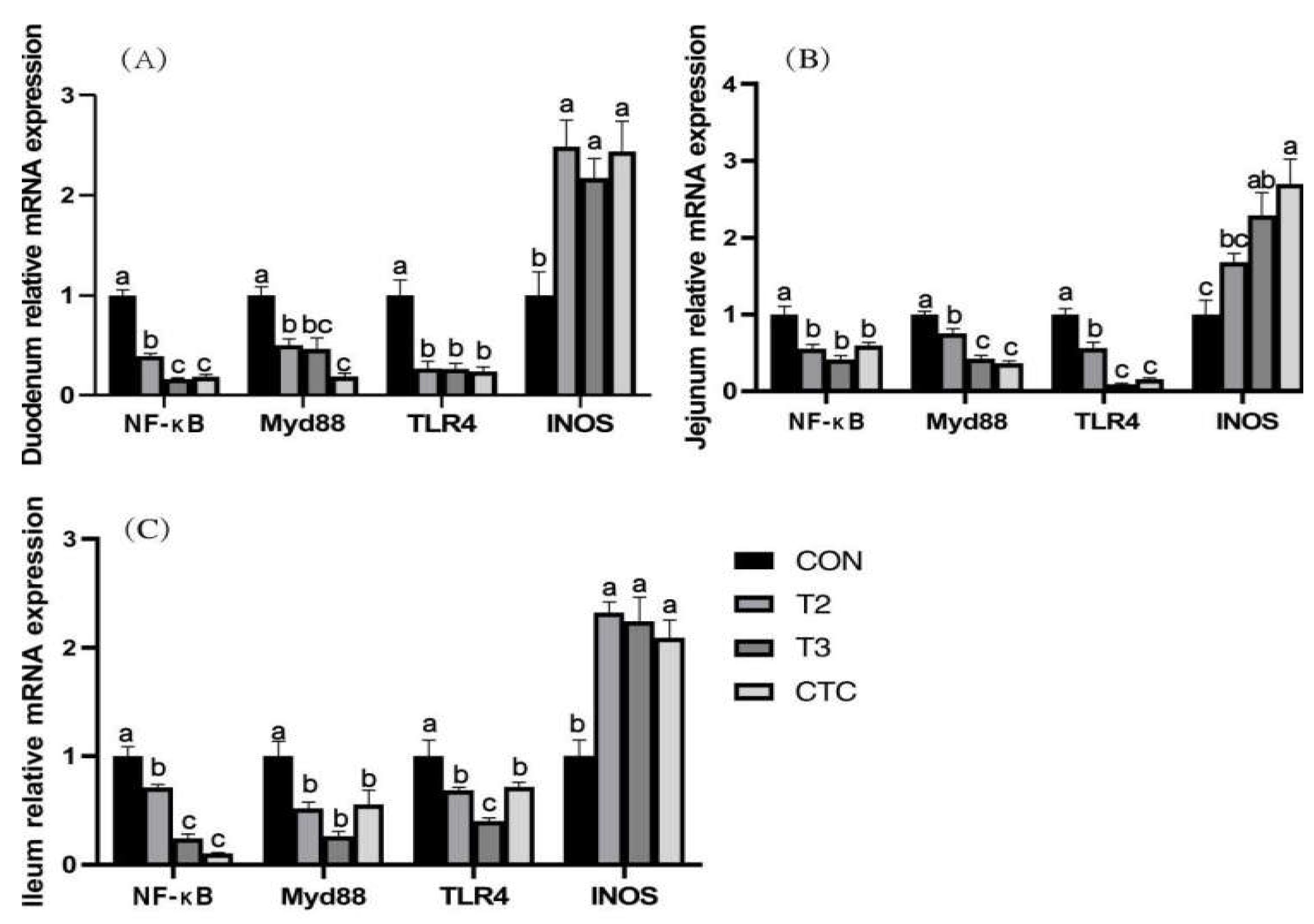

3.5. Effects of Tea Polyphenols on the Expression of the TLR4/NFκB Pathway-Related Genes and iNOS Gene Expression in the Intestines of Weaned Lambs

3.6. Effects of Tea Polyphenols on Volatile Fatty Acids in the Cecum of Weaned Lambs

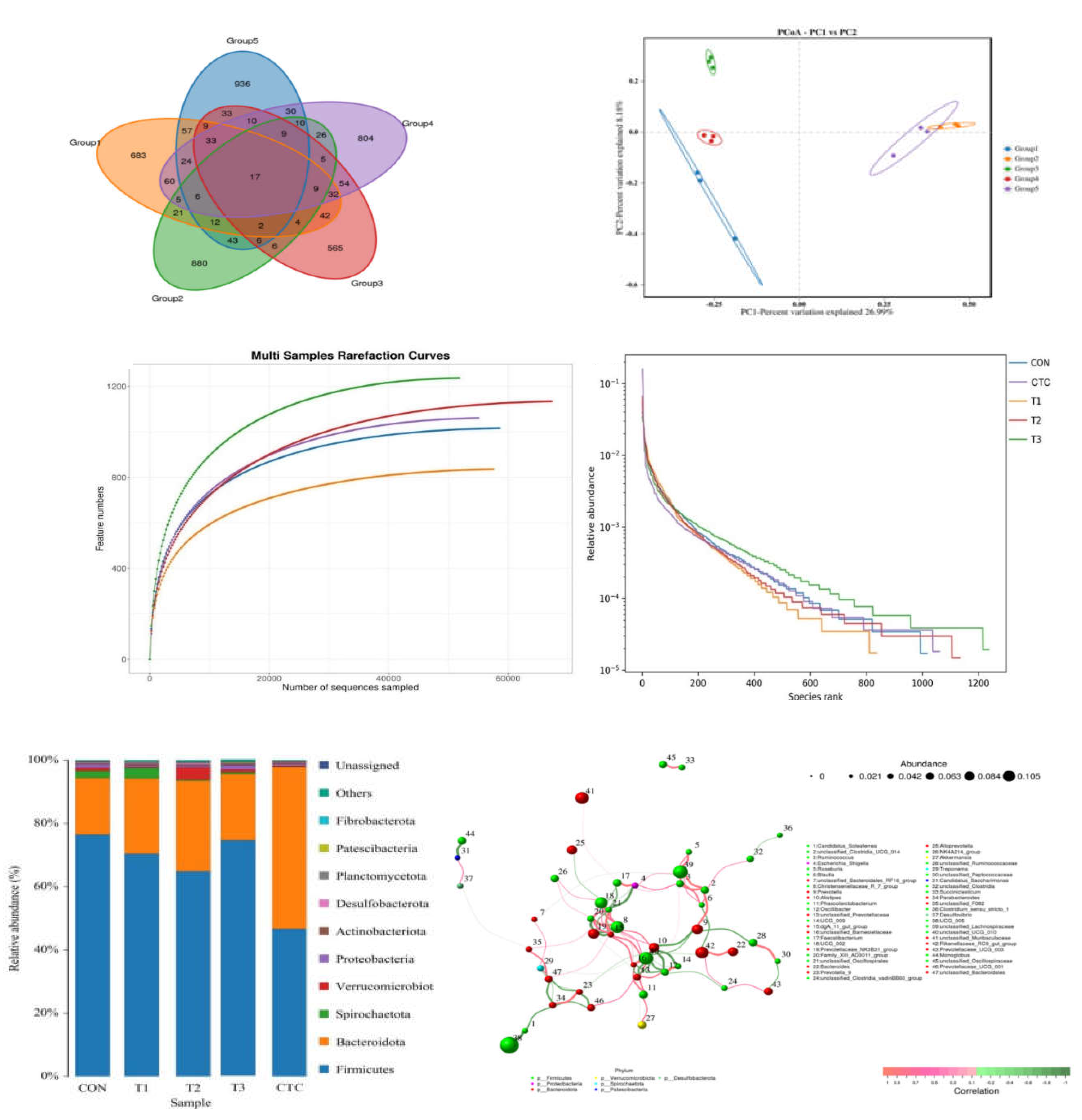

3.7. Effects of Tea Polyphenols on the Composition of Cecal Bacteria in Weaned Lambs

4. Discussion

4.1. Effects of Tea Polyphenols on Antioxidant Capacity and iNOS in Weaned Lambs

4.2. Effects of Tea Polyphenols on the Expression of Cytokines and TLR4/NFκB Pathway Related Genes in Lamb Intestinal Cells

4.3. Effects of Tea Polyphenols on Volatile Fatty Acids in the Intestinal Tract of Weaned Lambs

4.4. Eeffect of Tea Polyphenols on the Gut Microbiota of Weaned Lambs

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hammon, H.M.; Liermann, W.; Frieten, D.; Koch, C. Review: Importance of colostrum supply and milk feeding intensity on gastrointestinal and systemic development in calves. Animal. 2020, 14, s133–s143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.Q.; Ma, T.; Zhao, G.H.; Zhang, N.F.; Tu, Y.; Li, F.D.; Cui, K.; Bi, Y.L.; Ding, H.B.; Diao, Q.Y. Effect of Age and Weaning on Growth Performance, Rumen Fermentation, and Serum Parameters in Lambs Fed Starter with Limited Ewe-Lamb Interaction. Animals 2019, 9, 825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, W.J.; Zhang, W.J.; Niu, J.L.; Yao, J. Effect of Marine Red Yeast Rhodosporidium paludigenum on Diarrhea Rate, Serum Antioxidant Competence, Intestinal Immune Capacity, and Microflora Structure in Early-Weaned Lambs. Biomed Res Int 2022, 2228632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCoard, S.A.; Cristobal-Carballo, O.; Knol, F.W.; Heiser, A.; Khan, M.A.; Hennes, N.; Johnstone, P.; Lewis, S.; Stevens, D.R. Impact of early weaning on small intestine, metabolic, immune and endocrine system development, growth and body composition in artificially reared lambs. J Anim Sci. 2020, 98, skz356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Li, C.; Niu, X.L.; Zhang, Z.A.; Li, F.D.; Li, F. An intensive milk replacer feeding program benefits immune response and intestinal microbiota of lambs during weaning. BMC Vet Res. 2018, 14, 366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Wang, W.M.; Liu, T.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, G.X.; Li, F.D.; Li, F.; Yue, X.P.; Li, T.F. Effect of Early Weaning on the Intestinal Microbiota and Expression of Genes Related to Barrier Function in Lambs. Front Microbiol. 2018, 9, 1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, G.Z.; Yang, W.G.; Fan, C.J.; Lan, R.X.; Gao, Z.H.; Gan, S.Q.; Yu, H.B.; Yin, F.Q.; Wang, Z.J. The effects of fucoidan as a dairy substitute on diarrhea rate and intestinal barrier function of the large intestine in weaned lambs. Front Vet Sci. 2022, 9, 1007346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lourenco, J.M.; Hampton, R.S.; Johnson, H.M.; Callaway, T.R.; Rothrock, M.J.Jr.; Azain, M.J. The Effects of Feeding Antibiotic on the Intestinal Microbiota of Weanling Pigs. Front Vet Sci. 2021, 8, 601394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jibola-Shittu, M.Y.; Heng, Z.; Keyhani, N.O.; Dang, Y.X.; Chen, R.Y.; Liu, S.; Lin, Y.S.; Lai, P.Y.; Chen, J.H.; Yang, C.J.; Zhang, W.B.; Lv, H.J.; Wu, Z.Y.; Huang, S.S.; Cao, P.X.; Tian, L.; Qiu, Z.X.; Zhang, X.Y.; Guan, X.Y.; Qiu, J.Z. Understanding and exploring the diversity of soil microorganisms in tea (Camellia sinensis) gardens: toward sustainable tea production. Front Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1379879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanwar, J.; Taskeen, M.; Mohammad, I.; Huo, C.; Chan, T.H.; Dou, Q.P. Recent advances on tea polyphenols. Front Biosci (Elite Ed). 2012, 4, 111–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.X.; Wang, X.L.; Podio, N.S.; Wang, X.Y.; Xu, S.Y.; Jiang, S.H.; Wei, X.; Han, Y.N.; Cai, Y.Y.; Chen, X.Y.; Jin, F.; Li, X.B.; Gong, E.S. Research progress on the regulation of oxidative stress by phenolics: the role of gut microbiota and Nrf2 signaling pathway. J Sci Food Agric. 2024, 104, 1861–1873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bešlo, D.; Golubić, N.; Rastija, V.; Agić, D.; Karnaš, M.; Šubarić, D.; Lučić, B. Antioxidant Activity, Metabolism, and Bioavailability of Polyphenols in the Diet of Animals. Antioxidants (Basel). 2023, 12, 1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dangles, O. Antioxidant activity of plant phenols: chemical mechanisms and biological significance. Curr Org Chem. 2012, 16, 692–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao X, Shi X, Liu QQ, Li XJ. Tea polyphenols alleviates acetochlor-induced apoptosis and necroptosis via ROS/MAPK/NF-κB signaling in Ctenopharyngodon idellus kidney cells. Aquat Toxicol. 2022, 246, 106153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.; Gao, Z.P.; Qian, Y.J.; Li, X.; Wang, J.Y.; Ma, J.; Guo, J.J.; Fu, F.H. Effects of Different Concentrations of Ganpu Tea on Fecal Microbiota and Short Chain Fatty Acids in Mice. Nutrients. 2021, 13, 3715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kafantaris, I.; Kotsampasi, B.; Christodoulou, V.; Kokka, E.; Kouka, P.; Terzopoulou, Z.; Gerasopoulos, K.; Stagos, D.; Mitsagga, C.; Giavasis, I.; Makri, S.; Petrotos, K.; Kouretas, D. Grape pomace improves antioxidant capacity and faecal microflora of lambs. J Anim Physiol Anim Nutr (Berl). 2017, 101, e108–e121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.W.; Yin, F.Q.; Wang, J.L.; Wu, P.X.; Qiu, X.Y.; He, X.L.; Xiao, Y.M.; Gan, S.Q. Effect of tea polyphenols on intestinal barrier and immune function in weaned lambs. Front Vet Sci. 2024, 11, 1361507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.G.; Guo, G.Z.; Chen, J.Y.; Wang, S.N.; Gao, Z.H.; Zhao, Z.H.; Yin, F.Q. Effects of Dietary Fucoidan Supplementation on Serum Biochemical Parameters, Small Intestinal Barrier Function, and Cecal Microbiota of Weaned Goat Kids. Animals 2022, 12, 1591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Callahan, B.J.; McMurdie, P.J.; Rosen, M.J.; Han, A.W.; Johnson, A.J.; Holmes, S.P. DADA2: High-resolution sample inference from Illumina amplicon data. Nat Methods. 2016, 13, 581–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajković, E.; Schwarz, C.; Kapsamer, S.B.; Schedle, K.; Reisinger, N.; Emsenhuber, C.; Ocelova, V.; Roth, N.; Frieten, D.; Dusel, G.; Gierus, M. Evaluation of a Dietary Grape Extract on Oxidative Status, Intestinal Morphology, Plasma Acute-Phase Proteins and Inflammation Parameters of Weaning Piglets at Various Points of Time. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.J.; Kim, E.H.; Hahm, K.B. Oxidative stress in inflammation-based gastrointestinal tract diseases: challenges and opportunities. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012, 27, 1004–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, M.W.; Huang, H.J.; Wang, L.; Yin, L.M.; Yang, H.S.; Chen, C.Q.; Zheng, Q.K.; He, S.P. Tannic acid attenuates intestinal oxidative damage by improving antioxidant capacity and intestinal barrier in weaned piglets and IPEC-J2 cells. Front Nutr. 2022, 9, 1012207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, X.; Tan, B.; Song, M.H.; Ji, P.; Kim, K.; Yin, Y.L.; Liu, Y.H. Nutritional Intervention for the Intestinal Development and Health of Weaned Pigs. Front Vet Sci. 2019, 6, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, A.L.; Ma, T.T.; Zhong, Y.J.; Deng, S.; Zhu, S.P.; Fu, Z.Q.; Huang, Y.H.; Fu, J. Effect of tea polyphenols supplement on growth performance, antioxidation, and gut microbiota in squabs. Front Microbiol. 2024, 14, 1329036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.X.; Wang, T.T.; Li, Z.M.; Guo, Y.X.; Granato, D. Green Tea Polyphenols Upregulate the Nrf2 Signaling Pathway and Suppress Oxidative Stress and Inflammation Markers in D-Galactose-Induced Liver Aging in Mice. Front Nutr. 2022, 9, 836112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aziz-Aliabadi, F.; Noruzi, H.; Hassanabadi, A. Effect of different levels of green tea (Camellia sinensis) and mulberry (Morus alba) leaves powder on performance, carcass characteristics, immune response and intestinal morphology of broiler chickens. Vet Med Sci. 2023, 9, 1281–1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Ding, X.M.; Wang, J.P.; Bai, S.P.; Zeng, Q.F.; Su, Z.W.; Xuan, Y.; Zhang, K.Y. Tea polyphenols increase the antioxidant status of laying hens fed diets with different levels of ageing corn. Anim Nutr. 2021, 7, 650–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, J.; Shen, X.H.; Ai, Y.H.; Han, X.J. Tea polyphenols protect against ischemia/reperfusion-induced liver injury in mice through anti-oxidative and anti-apoptotic properties. Exp Ther Med. 2016, 12, 3433–3439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, X.; Song, J.L.; Yi, R.K.; Li, G.J.; Sun, P.; Park, K.Y.; Suo, H.Y. Comparison of Antioxidative Effects of Insect Tea and Its Raw Tea (Kuding Tea) Polyphenols in Kunming Mice. Molecules. 2018, 23, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imam, H.; Zhang, K.Q.; Wu, H.; Xiao, J.S.; Huang, M.Q.; Cao, Y.P. Epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG) inhibits lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammation in RAW 264.7 macrophage cells via modulating nuclear factor kappa-light-chain enhancer of activated B cells (NF-κB) signaling pathway. Food Sci Nutr. 2023, 11, 4634–4650. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, I.C.; Lin, Y.T.; Huang, J.S.; Wu, B.N.; Hsu, J.H.; Tan, M.S.; Dai, Z. K. Decreased Ambient Oxygen Tension Alters the Expression of Endothelin-1, iNOS and cGMP in Rat Alveolar Macrophages. Int J Med Sci. 2019, 16, 443–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, G.E.; Rowlands, D.J.; Li, F.Y.; Winter, P.de.; Siow, R.C. Activation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase by dietary isoflavones: role of NO in Nrf2-mediated antioxidant gene expression. Cardiovasc Res. 2007, 75, 261–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, S.J.; Liao, X.Y.; Zhu, Z.J.; Huang, R.; Chen, M.F.; Huang, A.H.; Zhang, J.; Wu, Q.; Wang, J.; Ding, Y. Antioxidant and anti-inflammation effects of dietary phytochemicals: The Nrf2/NF-κB signalling pathway and upstream factors of Nrf2. Phytochemistry. 2022, 204, 113429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mokra, D.; Joskova, M.; Mokry, J. Therapeutic Effects of Green Tea Polyphenol (‒)-Epigallocatechin-3-Gallate (EGCG) in Relation to Molecular Pathways Controlling Inflammation, Oxidative Stress, and Apoptosis. Int J Mol Sci. 2022, 24, 340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.B.; Kang, H.; Li, Y.; Park, Y.K.; Lee, J.Y. Fucoxanthin inhibits lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammation and oxidative stress by activating nuclear factor E2-related factor 2 via the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/AKT pathway in macrophages. Eur J Nutr. 2021, 60, 3315–3324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muzio, M.; Ni, J.; Feng, P.; Dixit, V.M. IRAK (Pelle) family member IRAK-2 and MyD88 as proximal mediators of IL-1 signaling. Science. 1997, 278, 1612–1615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, R.; Han, F.X.; Wang, H.R; Wang, J.J.; Cai, Z.L.; Guo, M.Y. Tea polyphenols alleviate TBBPA-induced inflammation, ferroptosis and apoptosis via TLR4/NF-κB pathway in carp gills. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2024, 146, 109382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, L.; Miao, Y.; Shan, B.; Zhao, C.Y.; Peng, C.X.; Gong, J.S. Theabrownin Isolated from Pu-Erh Tea Enhances the Innate Immune and Anti-Inflammatory Effects of RAW264.7 Macrophages via the TLR2/4-Mediated Signaling Pathway. Foods. 2023, 12, 1468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.X.; Li, Q.Q.; Yang, Y.J.; Guo, A.W. Biological Function of Short-Chain Fatty Acids and Its Regulation on Intestinal Health of Poultry. Front Vet Sci. 2021, 8, 736739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parada Venegas, D.; De la Fuente, M. K.; Landskron, G.; González, M.J.; Quera, R.; Dijkstra, G.; Harmsen, H. J. M.; Faber, K. N.; Hermoso, M. A. Short Chain Fatty Acids (SCFAs)-Mediated Gut Epithelial and Immune Regulation and Its elevance for Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. Front Immunol. 2019, 10, 277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Louis, P.; Flint, H.J. Formation of propionate and butyrate by the human colonic microbiota. Environ Microbiol. 2017, 19, 29–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Markowiak-Kopeć, P.; Śliżewska, K. The Effect of Probiotics on the Production of Short-Chain Fatty Acids by Human Intestinal Microbiome. Nutrients. 2020, 12, 1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, Q.Z.; Zhang, B.W.; Zheng, W.; Chen, X.J.; Zhang, J.; Yan, R.Y.; Zhang, T.; Yu, L.Y.; Dong, Y.S.; Ma, B.P. Liupao tea extract alleviates diabetes mellitus and modulates gut microbiota in rats induced by streptozotocin and high-fat, high-sugar diet. Biomed Pharmacother. 2019, 118, 109262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hee van der, B.; Wells, J.M. Microbial Regulation of Host Physiology by Short-chain Fatty Acids. Trends Microbiol. 2021, 29, 700–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, Y.; Cai, X.Y.; Fei, W.D.; Ye, Y.Q.; Zhao, M.D.; Zheng, C.H. The role of short-chain fatty acids in immunity, inflammation and metabolism. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2022, 62, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, X.N.; Chen, Z.J.; Sun, X.H.; Li, F.J.; Luo, J.Y.; Chen, T.; Xi, Q.H.; Zhang, Y.L.; Sun, J.J. Fermentation quality of herbal tea residue and its application in fattening cattle under heat stress. BMC Vet Res. 2021, 17, 348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khairudin, M.A.S.; Mhd Jalil, A.M.; Hussin, N. Effects of Polyphenols in Tea (Camellia sinensis sp.) on the Modulation of Gut Microbiota in Human Trials and Animal Studies. Gastroenterology Insights. 2021, 12, 202–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.; Zhou, C.F.; Tan, Z.; Cai, X.L.; Wang, S.B. Effects of Enteromorpha polysaccharide dietary addition on the diversity and relative abundance of ileum flora in laying hens. Microb Pathog. 2021, 158, 105004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Z.X.; Yang, Q.H.; Tan, B.P.; Lin, H.X.; Yi, Y.M. Effects of dietary tea polyphenols on intestinal microflora and metabonomics in juvenile hybrid sturgeon (Acipenser baerii♀ × A. schrenckii ♂). Aquac Rep. 2024, 35, 102020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, G.T.; Wang, Z.N.; Wu, G.X.; Zhang, R.F.; Dong, L.H.; Huang, F.; Zhang, M.W.; Su, D.X. Lychee (Litchi chinensis Sonn.) Pulp Phenolics Activate the Short-Chain Fatty Acid-Free Fatty Acid Receptor Anti-inflammatory Pathway by Regulating Microbiota and Mitigate Intestinal Barrier Damage in Dextran Sulfate Sodium-Induced Colitis in Mice. J Agric Food Chem. 2021, 69, 3326–3339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Chen, C.F.; Yang, H.; Yang, X.P. Tea polyphenols regulate gut microbiota dysbiosis induced by antibiotic in mice. Food Res Int. 2021, 141, 110153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ozato, N.; Saito, S.; Yamaguchi, T.; Katashima, M.; Tokuda, I.; Sawada, K.; Katsuragi, Y.; Kakuta, M.; Imoto, S.; Ihara, K.; Nakaji, S. Blautia genus associated with visceral fat accumulation in adults 20-76 years of age. NPJ Biofilms Microbiomes. 2019, 5, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.M.; Mao, B.Y.; Gu, J.Y.; Wu, J.Y.; Cui, S.M.; Wang, G.; Zhao, J.X.; Zhang, H.; Chen, W. Blautia-a new functional genus with potential probiotic properties? Gut Microbes. 2021, 13, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, Y.W.; Li, M.W.; Kong, K.Y.; Xie, Y.X.; Zeng, Z.; Fang, Z.F.; Li, C.; Hu, B.; Hu, X.J.; Wang, C.X.; Chen, S.Y.; Wu, W.J.; Lan, X.G.; Liu, Y.T. In vitro simulated digestion of and microbial characteristics in colonic fermentation of polysaccharides from four varieties of Tibetan tea. Food Res Int. 2023, 163, 112255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tett, A.; Pasolli, E.; Masetti, G.; Ercolini, D.; Segata, N. Prevotella diversity, niches and interactions with the human host. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2021, 19, 585–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, J.; Ren, Y.F.; Wen, X.; Yue, S.M.; Wang, Z.S.; Wang, L.Z.; Peng, Q.H.; Hu, R.; Zou, H.W.; Jiang, Y.H.; Hong, Q.H.; Xue, B. Comparison of coated and uncoated trace elements on growth performance, apparent digestibility, intestinal development and microbial diversity in growing sheep. Front Microbiol. 2022, 13, 1080182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, X.; Ouyang, K.; Long, T.H.; Liu, Z.G.; Li, Y.G.; Qiu, Q.H. Dynamic Variations in Rumen Fermentation Characteristics and Bacterial Community Composition during In Vitro Fermentation. Fermentation. 2022, 8, 276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Ingredients(%) | Content | Nutrient level | Content |

| Pennisetum × sinese | 50.00 | DM (%) | 90.80 |

| Corn | 29.00 | CP | 14.69 |

| Soybean meal | 10.00 | EE | 2.84 |

| Wheat bran | 7.50 | ADF | 26.23 |

| NaCl | 0.50 | NDF | 39.90 |

| CaHPO4 | 0.50 | Ca | 0.54 |

| Limestone | 0.50 | P | 1.10 |

| Premix1 | 2.00 | CA | 7.90 |

| Total | 100 | ME2 (MJ/Kg) | 10.43 |

| Gene | Primer sequences(5’-3’) | GenBank accession No. | Length(bp) |

| CAT | F:CACTCAGGTGCGGGATTTCT | XM_004016396.5 | 163 |

| R:CTGGATGCGGGAGCCATATT | |||

| INOS | F:ACGGGGACGGTAAAGACATC | XM_013971952.2 | 210 |

| R:CCGGGGTCCTATGGTCAAAC | |||

| GPX1 | F:CAGTTTGGGCATCAGGAAAACG | XM_004018462.5 | 128 |

| R:GCCTTCTCGCCATTCACCTC | |||

| SOD1 | F:CCATCCACTTCGAGGCAAAG | NM_001285550.1 | 124 |

| R:GCACTGGTACAGCCTTGTGTA | |||

| Nrf2 | F:TCTGCTGTCAAGGGACATGGA | NM_001314327.1 | 212 |

| R:CGCCGGTCTCTTCATCTAGT | |||

| NFκB | F:GAAGAGAAGGCGCTCACCAT | XM_018066509.1 | 107 |

| R:ATCACAGCCAAGTGGAGTGG | |||

| MYD88 | F:ACTCATTGAGAAGAGGTGCCG | XM_013973392.2 | 139 |

| R:CTTGATGGGGATCAGTCGCT | |||

| TNF-α | F:TGCACTTCGGGGTAATCGG | NM_001024860.1 | 144 |

| R:CGCTGATGTTGGCTACAACG | |||

| TLR4 | F:GGGTGCGGAATGAACTGGTA | NM_001285574.1 | 158 |

| R:CTGGGACACCACGACAATCA | |||

| IL-1β | F:AATGAGCCGAGAAGTGGTGT | XM_013967700.2 | 136 |

| R:CAGTGTCGGCGTATCACCTT | |||

| IL-10 | F:TACCCACTCTGGGGTCTTGT | XM_005690416.3 | 121 |

| R:CTGCCAAGCTCATTCACACG | |||

| IFN-γ | F:AGATCCAGCGCAAAGCCATA | NM_001285682.1 | 110 |

| R:TCTCCGGCCTCGAAAGAGAT | |||

| GAPDH | F:GATGCCCCCATGTTTGTGATG | XM_005680968.3 | 160 |

| R:CGTGGACAGTGGTCATAAGTC | |||

| IL-6 | F:ATCTGGGTTCAATCAGGCGAT | NM_001285640.1 | 247 |

| R:TGCGTTCTTTACCCACTCGT |

| Items | Groups | SEM | P-Value | ||||

| CON | T1 | T2 | T3 | CTC | |||

| MDA (nmol/mgprot) | 2.18a | 2.00a | 1.07b | 0.82b | 1.89a | 0.162 | 0.002 |

| GSH-Px (U/gprot) | 65.29c | 65.12c | 97.52b | 66.01c | 106.28a | 4.908 | <0.001 |

| CAT (U/mgprot) | 2.31c | 2.59bc | 2.94a | 2.77ab | 2.64b | 0.066 | 0.005 |

| T-SOD (U/mgprot) | 117.17b | 117.43b | 164.15a | 128.24b | 164.81a | 5.948 | <0.001 |

| T-AOC (mmol/gprot) | 0.56cd | 0.51d | 0.87a | 0.61c | 0.79b | 0.037 | <0.001 |

| Items | Groups | SEM | P-Value | ||||

| CON | T1 | T2 | T3 | CTC | |||

| Duodenum | |||||||

| IL-1β (pg/mL) | 75.10a | 59.79b | 54.73c | 49.77d | 43.75e | 2.054 | <0.001 |

| IL-6 (pg/mL) | 141.35a | 126.30b | 122.91b | 104.18c | 81.18d | 3.937 | <0.001 |

| IL-10 (pg/mL) | 43.64d | 49.91c | 52.24c | 58.08b | 65.22a | 1.429 | <0.001 |

| TNF-α (pg/mL) | 266.69a | 213.88b | 212.14b | 200.75b | 154.36c | 6.923 | <0.001 |

| NO (μmol/L) | 30.00d | 33.59c | 34.78c | 37.57b | 43.17a | 0.869 | <0.001 |

| iNOS (pg/mL) | 75.78d | 79.98cd | 82.96c | 103.65b | 110.26a | 2.668 | <0.001 |

| IFN-γ (pg/mL) | 569.04a | 560.0216a | 528.01a | 427.94b | 350.79c | 16.936 | <0.001 |

| Jejunum | |||||||

| IL-1β (pg/mL) | 66.60a | 62.55a | 56.39b | 48,84c | 39.63d | 1.858 | <0.001 |

| IL-6 (pg/mL) | 138.85a | 122.39b | 117.66b | 94.67c | 86.69c | 3.678 | <0.001 |

| IL-10 (pg/mL) | 42.19d | 48.13c | 53.50b | 56.03b | 63.60a | 1.450 | <0.001 |

| TNF-α (pg/mL) | 284.46a | 236.28b | 227.80b | 202.40c | 167.86d | 7.363 | <0.001 |

| NO (μmol/L) | 29.25d | 33.94c | 34.77c | 39.68b | 43.31a | 0.945 | <0.001 |

| iNOS (pg/mL) | 75.44d | 79.73cd | 84.99c | 95.46b | 106.99a | 2.229 | <0.001 |

| IFN-γ (pg/mL) | 610.97a | 543.99b | 489.79c | 422.83d | 367.66e | 16.964 | <0.001 |

| Ileum | |||||||

| IL-1β (pg/mL) | 74.59a | 64.91b | 56.55c | 52.49d | 41.83e | 2.104 | <0.001 |

| IL-6 (pg/mL) | 131.52a | 123.40a | 120.88a | 98.14b | 88.67b | 3.446 | <0.001 |

| IL-10 (pg/mL) | 45.29c | 47.88c | 49.79c | 56.67b | 65.39a | 1.459 | <0.001 |

| TNF-α (pg/mL) | 262.52a | 250.28ab | 229.75b | 184.37c | 167.63c | 7.312 | <0.001 |

| NO (μmol/L) | 31.11c | 32.42c | 35.22b | 36.84b | 43.06a | 0.832 | <0.001 |

| iNOS (pg/mL) | 68.669e | 78.74d | 91.25c | 103.74b | 111.23a | 2.990 | <0.001 |

| IFN-γ (pg/mL) | 633.22a | 507.41b | 455.66c | 431.73c | 341.65d | 18.064 | <0.001 |

| Items | Groups | SEM | P-Value | ||||

| CON | T1 | T2 | T3 | CTC | |||

| Acetic Acid | 448.80b | 660.50b | 1281.85a | 612.88b | 715.56b | 87.844 | 0.005 |

| Propionic Acid | 420.67 | 394.61 | 703.58 | 648.02 | 412.95 | 47.695 | 0.071 |

| Isobutyric Acid | 151.50 | 163.23 | 158.032 | 158.31 | 168.62 | 5.492 | 0.927 |

| Butyric Acid | 234.52 | 345.35 | 358.19 | 321.52 | 259.99 | 28.82 | 0.647 |

| Isovaleric Acid | 154.089 | 161.87 | 155.287 | 163.34 | 168.53 | 4.827 | 0.910 |

| Items | Groups | SEM | P-Value | ||||

| CON | T1 | T2 | T3 | CTC | |||

| ACE | 1123.65 | 1145.74 | 1390.47 | 1258.08 | 1075.16 | 52.046 | 0.343 |

| Chao-1 | 1112.59 | 1135.93 | 1384.40 | 1249.713 | 1067.87 | 52.204 | 0.339 |

| Simpson | 0.988a | 0.986a | 0.992a | 0.991a | 0.963b | 0.003 | 0.015 |

| Shannon | 7.68a | 7.69ab | 8.27ab | 8.17a | 7.09b | 0.140 | 0.021 |

| Coverage | >99 % | ||||||

| Items | Groups | SEM | P-Value | ||||

| CON | T1 | T2 | T3 | CTC | |||

| Firmicutes | 69.12a | 61.83ab | 50.29b | 65.36a | 48.03b | 2.587 | 0.006 |

| Bacteroidota | 28.22b | 34.27ab | 36.74ab | 26.04b | 42.87a | 1.952 | 0.014 |

| Spirochaetota | 0.98 | 0.99 | 1.05 | 0.68 | 0.27 | 0.191 | 0.735 |

| Verrucomicrobiota | 1.89b | 1.49b | 3.68a | 0.57b | 0.73b | 0.348 | 0.006 |

| Proteobacteria | 0.932ab | 0.785b | 0.57b | 1.57a | 0.43b | 0.128 | 0.014 |

| Actinobacteriota | 0.51 | 0.29 | 0.27 | 0.26 | 0.435 | 0.059 | 0.64 |

| Items | Groups | SEM | P-value | ||||

| CON | T1 | T2 | T3 | CTC | |||

| Alistipes | 2.00 | 3.71 | 2.92 | 1.99 | 1.22 | 0.377 | 0.284 |

| Blautia | 0.17b | 0.21b | 0.72a | 0.68a | 0.30ab | 0.078 | 0.019 |

| Candidatus_Soleaferrea | 0.41a | 0.47a | 0.65a | 0.42a | 0.18b | 0.045 | 0.002 |

| Christensenellaceae R-7 group | 5.83a | 7.31a | 4.13a | 5.10a | 2.69b | 0.531 | 0.035 |

| unclassified_Bacteroidales_RF16_group | 0.25 | 0.05 | 0.67 | 0.48 | 0.33 | 0.087 | 0.199 |

| Ruminococcus | 1.10 | 1.12 | 1.19 | 1.36 | 0.28 | 0.187 | 0.452 |

| Escherichia_Shigella | 0.06 | 0.14 | 0.7 | 1.22 | 0.03 | 0.254 | 0.557 |

| unclassified_Clostridia_UCG_014 | 1.52 | 0.58 | 1.42 | 1.29 | 0.87 | 0.171 | 0.414 |

| Roseburia | 0.38 | 0.52 | 0.36 | 0.91 | 0.418 | 0.109 | 0.136 |

| Prevotella | 1.11b | 0.30b | 5.85a | 3.20ab | 2.49b | 0.611 | 0.01 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).