Submitted:

31 December 2024

Posted:

31 December 2024

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Data Used

2.3. Data-Processing and Derivation of the Land Surface Temperature (LST)

2.4. Derivation of the Urban Heat Island (UHI)

2.5. Spatial Analysis and Delineation of Urban-Rural Gradient Zones

3. Results

3.1. Spatio-Temporal Patterns of Urban Heat Island (UHI)

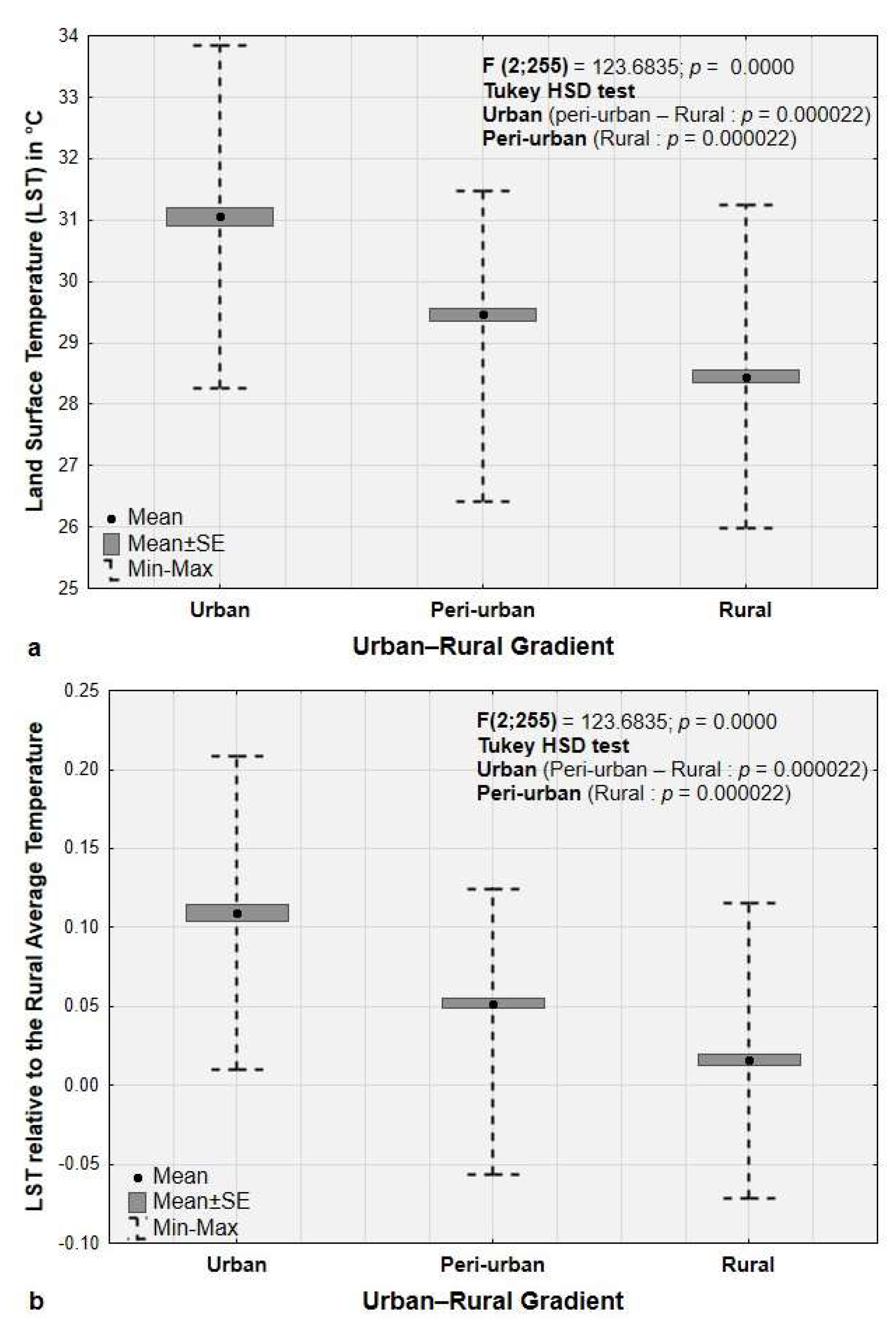

3.2. Variation in LST and UHI Across the Urban-Rural Gradient in 2024

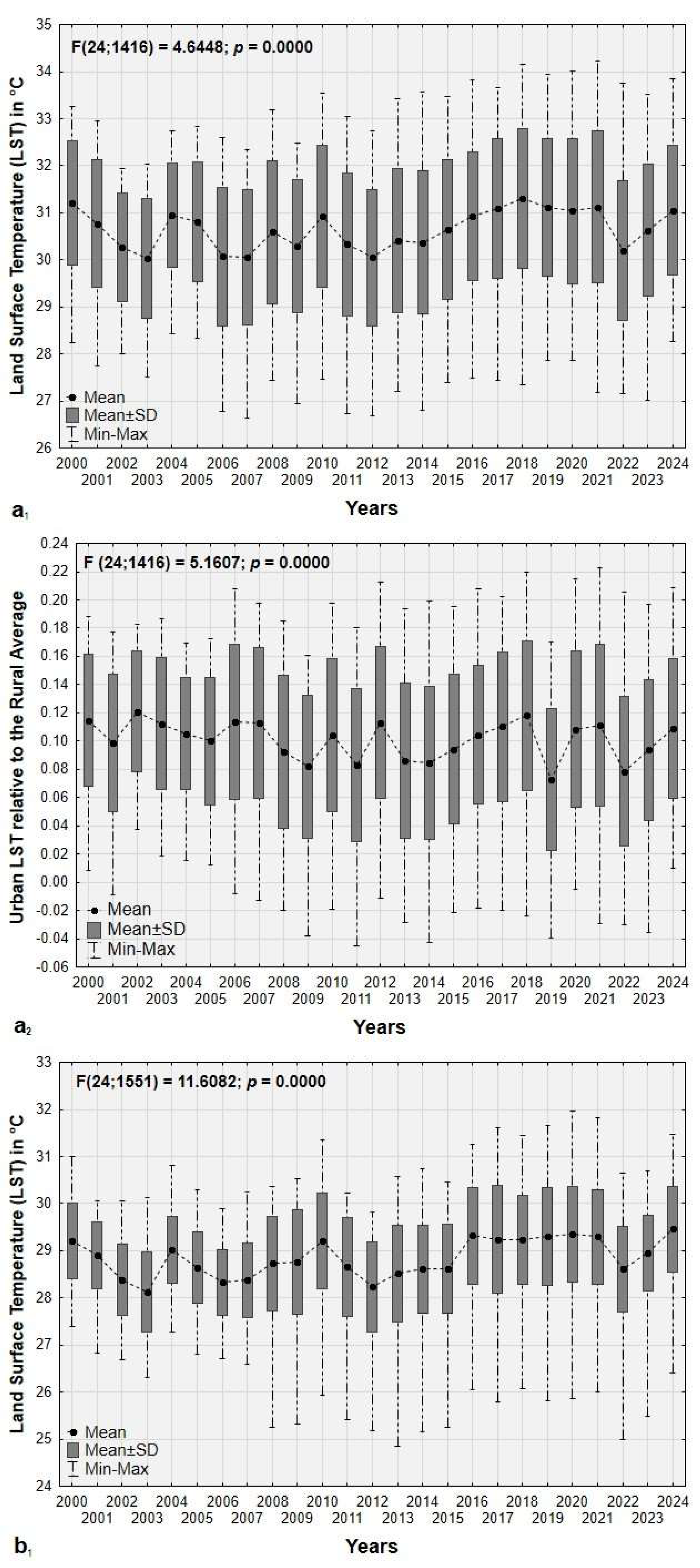

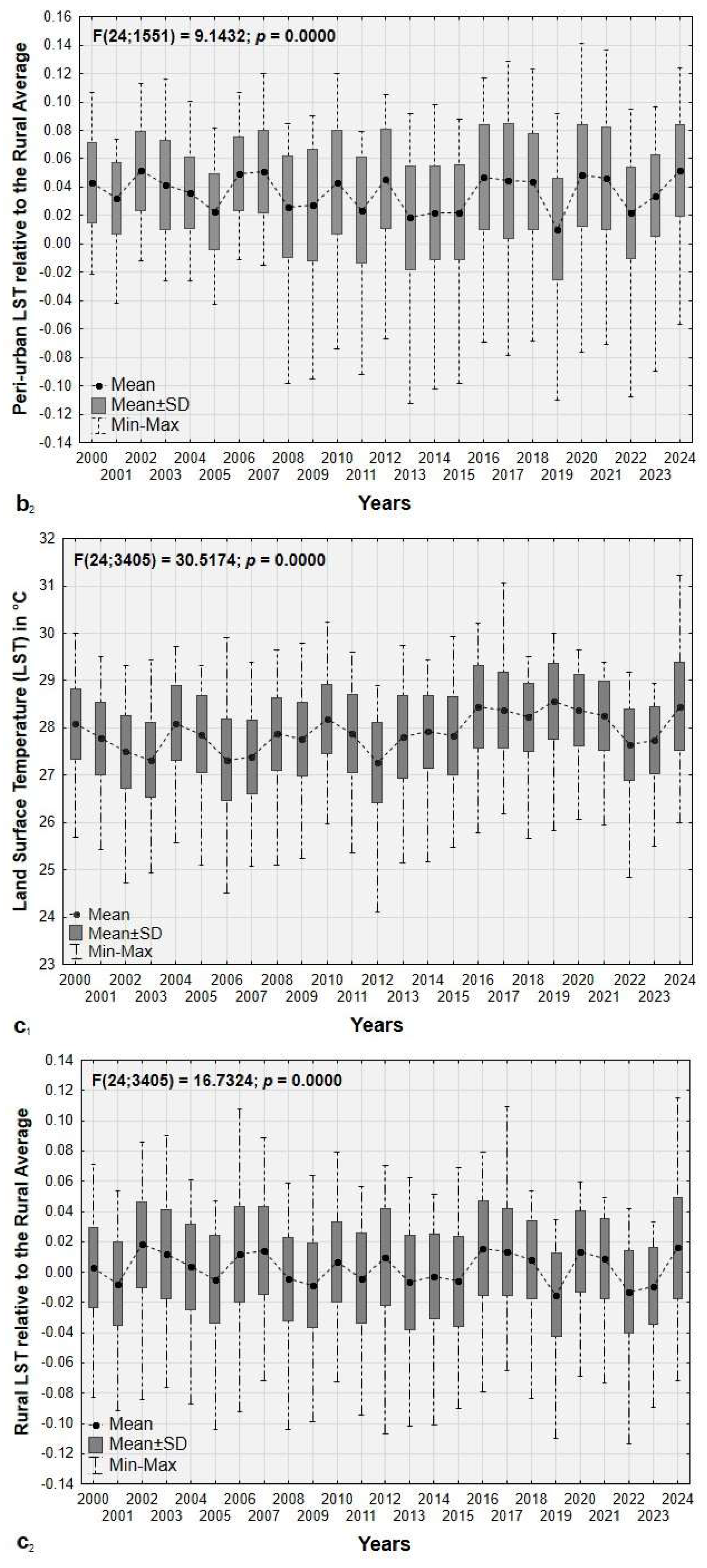

3.3. Historical Variations in LST and UHI Across the Urban-Rural Gradient

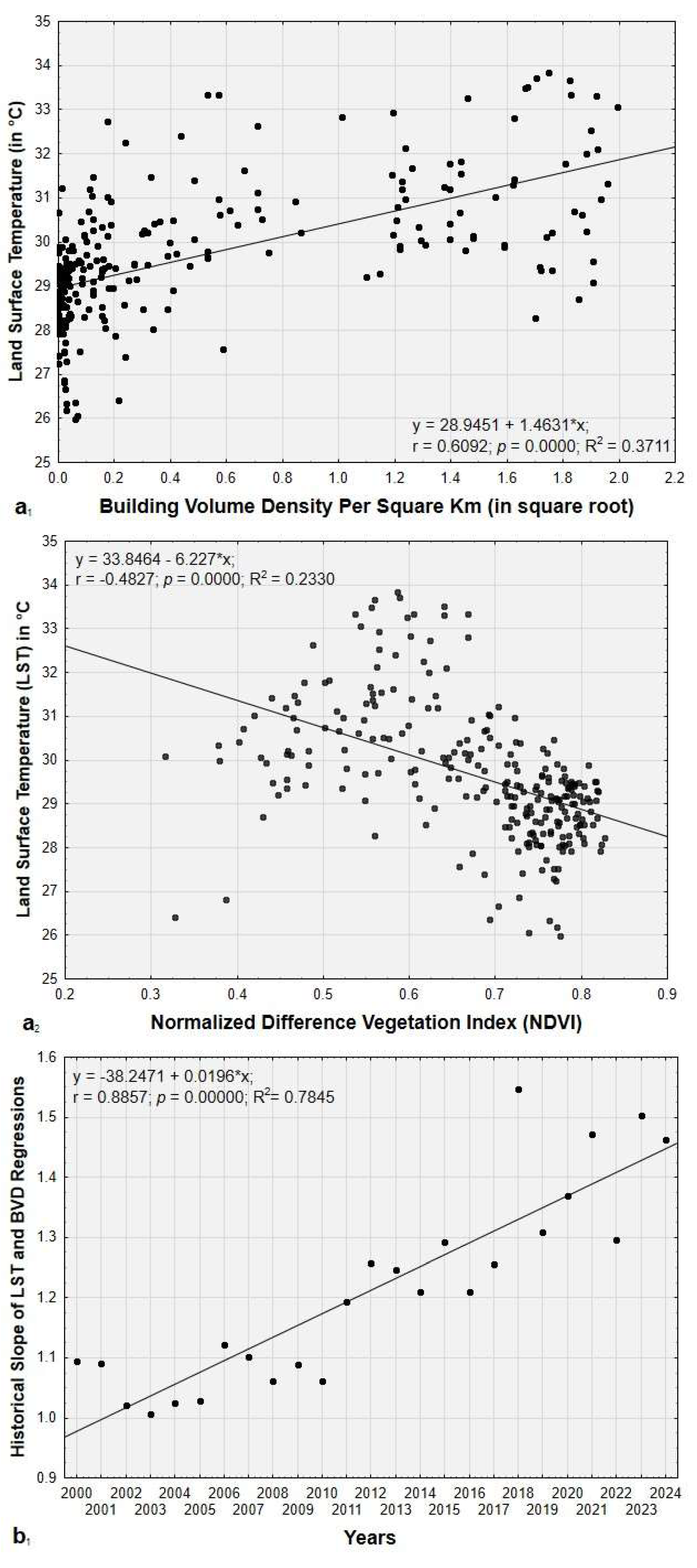

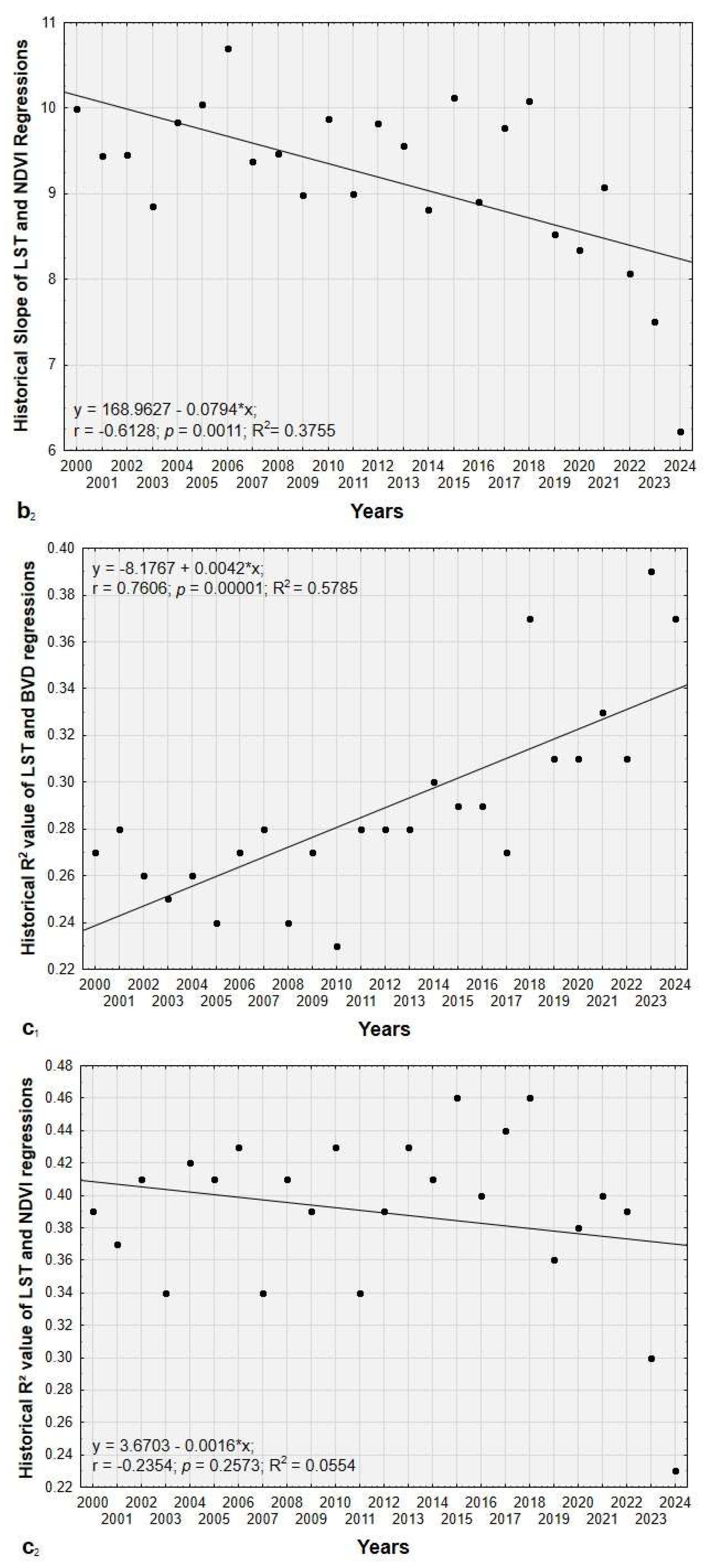

3.4. Building Volume Density (BVD) and Vegetation Effects

4. Discussion

4.1. Data and Spatial Analysis of the UHI

4.2. Spatio-Temporal Patterns of Urban Heat Island (UHI)

4.3. Impact of Building Architecture on the LST

4.4. Effective and Resilient Mitigation Strategies of UHI

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jato-espino, D. Spatiotemporal Statistical Analysis of the Urban Heat Island e Ff Ect in a Mediterranean Region. Sustain. Cities Soc., 2019, 46, 101427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwivedi, A.; Khire, M. V. Application of Split- Window Algorithm to Study Urban Heat Island e Ff Ect in Mumbai through Land Surface Temperature Approach. Sustain. Cities Soc., 2018, 41, 865–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolokotroni, M.; Giannitsaris, I.; Watkins, R. The Effect of the London Urban Heat Island on Building Summer Cooling Demand and Night Ventilation Strategies. 2006, 80, 383–392. [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Su, H.; Zhang, L.; Yang, H.; Zhang, R.; Li, X. Analysis of the Urban Heat Island Effect in Shijiazhuang, China Using Satellite and Airborne Data. 2015, 4804–4833. [CrossRef]

- Arnfield, A. J. Two Decades of Urban Climate Research : A Review of Turbulence, Exchanges of Energy and Water, and the Urban Heat Island. 2003, 26, 1–26. [CrossRef]

- Oke, T. R. Boundary Layer Climates - 2nd Ed.; 2002.

- Stewart, I. D.; Oke, T. R. Local Climate Zones for Urban Temperature Studies. Am. Meteorol. Soc. [CrossRef]

- Taha, H. Urban Climates and Heat Islands : Albedo, Evapotranspiration, and Anthropogenic Heat. 1997, 25, 99–103.

- Candra, A.; Lecturer, K.; Nitivattananon, V. Factors Influencing Urban Heat Island in Surabaya, Indonesia. Sustain. Cities Soc., 2016, 27, 99–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prilandita, N. Perceptions and Responses to Warming in an Urban Environment: A Case Study of Bandung City, Indonesia. 2009, V, 51–58.

- Martínez, F.; Fernando, N.; Aragonés, N.; Benítez, P.; Buitrago, M. J.; Casas, I.; Cortés, M.; Dürr, U.; Herrera, D.; Izquierdo, A.; et al. Assessment of the Impact of the Summer 2003 Heat Wave on Mortality. 2004, 18 (Supl 1), 250–258.

- Garcia-Herrera, R.; Díaz, J.; Trigo, R. M.; Luterbacher, J.; Fischer, E. M. A Review of the European Summer Heat Wave of 2003 A Review of the European Summer Heat Wave of 2003. 2010, 3389. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Qi, Z.; Ye, X.; Cai, Y.; Ma, W.; Chen, M. Analysis of Land Use / Land Cover Change, Population Shift, and Their Effects on Spatiotemporal Patterns of Urban Heat Islands in Metropolitan Shanghai, China. Appl. Geogr. 2013, 44, 121–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malley, C. O.; Piroozfarb, P. A. E.; Farr, E. R. P.; Gates, J. An Investigation into Minimizing Urban Heat Island ( UHI ) Effects : A UK Perspective. Energy Procedia 2014, 62, 72–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandal, J.; Pravin, P.; Samanta, S. Examining the Expansion of Urban Heat Island Effect in the Kolkata Metropolitan Area and Its Vicinity Using Multi-Temporal MODIS Satellite Data. Adv. Sp. Res. 2022, 69, 1960–1977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Stringer, L. C.; Chapman, S.; Id, M. D. How Urbanisation Alters the Intensity of the Urban Heat Island in a Tropical African City. 2021, 1–18. [CrossRef]

- Wemegah, C. S.; Yamba, E. I.; Aryee, J. N. A.; Sam, F.; Amekudzi, L. K. Assessment of Urban Heat Island Warming in the Greater Accra Region. Sci. African 2020, 8, e00426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balandi, J. B.; Meniko, J.-P. P. T. H.; Sambieni, K. R.; Sikuzani, Y. U.; Bastin, J.-F.; Musavandalo, C. M.; Elangi Langi, J. M.; Selemani, T. M.; Mweru, J. M.; Bogaert, J. Urban Sprawl and Changes in Landscape Patterns : The Case of Kisangani City and Its Periphery ( DR Congo ). 2023, 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Balandi, J. B.; Meniko, J.-P. P. T. H.; Sambieni, K. R.; Sikuzani, Y. U.; Bastin, J.-F.; Musavandalo, C. M.; Nguba, T. B.; Jesuka, R.; Sodalo, C.; Pika, L. M.; Bogaert, J. Anthropogenic Effects on Green Infrastructure Spatial Patterns in Kisangani City and Its Urban – Rural Gradient. 2024. [CrossRef]

- UN-Habitat. Habitat III RD Congo: Rapport Final. 2015, 1–93.

- Sabongo, P. Y. Etude Comparative de La Structure et de La Diversité Des Forêts à Gilbertiodendron Dewevrei (De Wild) J.Léonard Des Régions de Kisangani et de l’Ituri (RD Congo), Thèse de Doctorat. Université de Kisangani, 2015.

- Kottek, M.; Grieser, J.; Beck, C.; Rudolf, B.; Rubel, F. World Map of the Köppen-Geiger Climate Classification Updated. Meteorol. Zeitschrift 2006, 15, 259–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gabriel, K. B.; Omer, N. T. Etude Socio-Économique Des Conflits Des Guerres Armées Dans La Ville de Kisangani et Sa Périphérie En Province de La Tshopo (1997 à 2006). IJRDO - J. Soc. Sci. Humanit. Res. 2022, No. 5, 318–324.

- European Commission. GHSL Data Package 2023, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg; 2023. [CrossRef]

- Wan, Z. MODIS Land Surface Temperature Products Users ’ Guide. 2013.

- Azizi, S.; Azizi, T. Urban Climate Dynamics: Analyzing the Impact of Green Cover and Air Pollution on Land Surface Temperature—A Comparative Study Across Chicago, San Francisco, and Phoenix, USA. 2024.

- Didan, K.; Munoz, A. B.; Huete, A. MODIS Vegetation Index User ’ s Guide ( MOD13 Series. 2015, 2015 (June).

- Rendana, M.; Mohd, W.; Idris, R.; Rahim, S. A.; Abdo, H. G.; Almohamad, H.; Abdullah, A.; Dughairi, A.; Al-mutiry, M. Relationships between Land Use Types and Urban Heat Island Intensity in Hulu Langat District, Selangor, Malaysia. Ecol. Process. 2023, No. July. [CrossRef]

- Huang, Q.; Huang, J.; Yang, X.; Fang, C.; Liang, Y. Quantifying the Seasonal Contribution of Coupling Urban Land Use Types on Urban Heat Island Using Land Contribution Index : A Case Study in Wuhan, Sustain. Cities Soc. 2019, 44, 666–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marando, F.; Salvatori, E.; Sebastiani, A.; Fusaro, L.; Manes, F. Regulating Ecosystem Services and Green Infrastructure : Assessment of Urban Heat Island Effect Mitigation in the Municipality of Rome, Italy. Ecol. Modell. 2019, 392, 92–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sambieni, K. R. Dynamique Du Paysage de La Ville Province de Kinshasa Sous La Pression de La Périurbanisation: L’infrastructure Verte Comme Moteur d’aménagement. Thèse de Doctorat, Université de Liège, et ERAIFT. 2019, 1–261.

- Angel, S.; Parent, J.; Civco, D. L.; Blei, A.; Potere, D. The Dimensions of Global Urban Expansion: Estimates and Projections for All Countries, 2000-2050. Prog. Plann. 2011, 75, 53–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, L.; Zhang, T.; Wang, T. Evaluation of Collection-6 MODIS Land Surface Temperature Product Using Multi-Year Ground Measurements in an Arid Area of Northwest China. 2018, 1. [CrossRef]

- Wan, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Li, Z. Validation of the Land-Surface Temperature Products Retrieved from Terra Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer Data. 2002, 83, 163–180.

- Wen, C.; Mamtimin, A.; Feng, J.; Wang, Y.; Yang, F.; Huo, W.; Zhou, C.; Li, R.; Song, M.; Gao, J.; et al. Diurnal Variation in Urban Heat Island Intensity in Birmingham : The Relationship between Nocturnal Surface And. 2023.

- Dutta, D.; Rahman, A.; Paul, S. K.; Kundu, A. Urban Climate Impervious Surface Growth and Its Inter-Relationship with Vegetation Cover and Land Surface Temperature in Peri-Urban Areas of Delhi. Urban Clim., 2021, 37, 100799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- INS. Population de La Ville de Kisangani Repartie En Sexe, de 1990 à 2021. Kisangani 2022.

- Haodong, L.; Zheng, H.; Wu, L.; Deng, Y.; Chen, J.; Zhang, J. Spatiotemporal Evolution in the Thermal Environment and Impact Analysis of Drivers in the Beijing – Tianjin – Hebei Urban Agglomeration of China from 2000 to 2020. 2024.

- Ren, J.; Shi, K.; Kong, X.; Zhou, H. On-Site Measurement and Numerical Simulation Study on Characteristic of Urban Heat Island in a Multi-Block Region in Beijing, China. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2023, 95, 104615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, I.; Scalco, V.; Lamberts, R. Energy & Buildings Estimating the Impact of Urban Densification on High-Rise Office Building Cooling Loads in a Hot and Humid Climate. Energy Build. 2019, 182, 30–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, M.; Chen, L.; Leng, S.; Sun, R. Effects of Local Background Climate on Urban Vegetation Cooling and Humidification : Variations and Thresholds. Urban For. Urban Green. 2023, 80, 127840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziyan; Paschalis, A. ; Mijic, A.; Meili, N.; Manoli, G.; Reeuwijk, M. Van; Fatichi, S. Urban Climate A Mechanistic Assessment of Urban Heat Island Intensities and Drivers across Climates. Urban Clim. 2022, 44, 101215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omidvar, H.; Bou-zeid, E.; Li, Q.; Mellado, J. Plume or Bubble ? Mixed-Convection Flow Regimes and City-Scale Circulations. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Koluwa, S. K. De La Reparation Des Victimes de La Guerre de Six Jours à Kisangani. J. Soc. Sci. Humaniyies Res. 2020, 5, 44–56. [Google Scholar]

- Fengjiao, C.; Feng, S.; Feng, Q.; Yujie, W.; Tailong, Z.; Haiying, Y. Research Advances in the Influence of Vegetation on Urban Heat Island Effect. 2020, 56.

- Kwan, P.; Fung, C. K. W.; Jim, C. Y. Seasonal and Meteorological Effects on the Cooling Magnitude of Trees in Subtropical Climate. Build. Environ. 2020, 177, 106911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, S.; Andrade, H.; Vaz, T. The Cooling Effect of Green Spaces as a Contribution to the Mitigation of Urban Heat : A Case Study in Lisbon. Build. Environ. 2011, 46, 2186–2194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, P. K.; Jim, C. Y.; Siu, C. T. Effects of Urban Park Design Features on Summer Air Temperature and Humidity in Compact-City Milieu. Appl. Geogr. 2021, 129, 102439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Product ID | Layer | Spatial Resolution | Time scale |

|---|---|---|---|

| MOD11A2 V6.1 | LST Emissivity | 1000m | 01.01 – 31.12 |

| MOD13A2 | NDVI | 1000m | – 31.12 |

| GHS-BUILT-V | Building Volume | 1000m | Annual |

| Google Earth | GE Images | 1m | Annual |

| UHI (°C) | Level | Description |

|---|---|---|

| UHI ≤ 0 | Very low | Extreme low-temperature zone, meaning that there is no difference in LST between urban and rural areas. |

| 0<UHI ≤ 0.1 | Low | Low-temperature zone, which means that the LST variation between urban and rural areas is minimal. |

| 0.1<UHI ≤ 0.2 | Medium | Medium temperature region, meaning that the LST differs moderately between urban and rural areas. |

| 0.2<UHI ≤ 0.3 | High | High-temperature zone, meaning large urban/rural LST difference. |

| 0.3<UHI | Very high | Extremely high-temperature zone, meaning very large urban/rural LST difference. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).