1. Introduction

Short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) are the end products of microbial fermentation of indigestible carbohydrates (dietary fiber) [

1]. They are mainly produced in the large intestine, while food-derived SCFA are present in the small intestine. Thus, the content of SCFA in the large intestine reflects the combination of food intake and the formation of SCFA in situ. The most important SCFAs are acetate, propionate, and butyrate. They have been shown to have important signaling functions that affect host metabolism and physiology [

2,

3,

4]. Through the epigenetic regulation of gene transcription, SCFAs can influence various cellular processes. This modulation of gene expression is thought to be one of the mechanisms through which SCFAs exert their beneficial effects on host health [

5,

6].

Gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) is defined as any glucose intolerance that first appears in pregnancy [

7]. The prevalence varies between 1‒14 percent of all pregnancies, depending on the population and the diagnostic test used [

8]. 35 to 60 percent of women with GDM develop type 2 diabetes within 5 to 10 years after giving birth. In addition, they have a higher risk of complications during pregnancy, and their children are exposed to a higher risk of obesity and type 2 diabetes during adolescence and adulthood [

8,

9,

10]. It is known, that SCFAs in mother’s serum influence the metabolic changes that occur during pregnancy; glucose metabolism, maternal weight gain, levels of various metabolic hormones [

12,

13,

14]. SCFA concentrations in the serum were associated positively with maternal adiponectin levels, serum propionate correlated negatively with maternal leptin and no associations were observed with serum butyrate [

13].

Gomez-Arango et al. [

14] reported that SCFA production by gut bacteria was negatively associated with body mass index, meaning that higher SCFA concentrations resulted in lower body mass index. Their results also suggest that an increased number of butyrate-producing bacteria may contribute to lower blood pressure in overweight and obese pregnant women. Changes in isobutyrate, isovalerate and 2-methylbutyrate were inversely related to lower blood pressure, and increased valerate levels were associated with reduced carotid-femoral pulse wave velocity and consequently lower risk of cardiovascular complications [

15,

17].

A study by Fuller and colleagues [

18] found that FFA2 (free fatty acid receptors) signaling is essential for β-cell adaptation in pregnancy, indicating that gut microbiota, SCFA, and FFA2 work in balance during pregnancy to mediate glucose homeostasis. Based on the results they suggested that there may be a beneficial effect of SCFA on metabolic health during pregnancy, particularly in overweight and obese pregnant women. Further, it was shown that the level of propionic acid decreases with the course of pregnancy, however for obese pregnant women it is characteristic, that it increases. The increase in propionic acid levels in obese pregnant women and the correlation with glycosylated hemoglobin and fasting glucose levels could be considered a probable factor of glucose metabolism disorders in obese pregnant women [

19].

While SCFAs are an important source of energy for colonocytes and can also regulate host metabolism, excessive SCFA production and uptake may contribute to obesity and related metabolic disorders. SCFAs can be oxidized for energy, and their metabolites can be used for de novo lipid synthesis and gluconeogenesis [

20]. A meta-analysis has shown that among seven studies evaluated, people with obesity had significantly higher fecal SCFA content compared to lean controls [

21]. Excessive lipid synthesis and storage can contribute to the development of obesity, particularly when combined with a high-calorie diet and a sedentary lifestyle [

22].

The relationship between SCFA and body weight is complex and not fully understood. There are no data on the concentration or ratio of fecal SCFA in pregnant women with gestational diabetes. Therefore, the aim of this study was to determine the concentrations of SCFA in the feces of pregnant women with GDM in the second and third trimesters of pregnancy. In this study, we measured the concentrations of acetate, propionate, and butyrate. We hypothesized that fecal SCFA concentrations in overweight/obese women with GDM will differ from fecal SCFA concentrations in normal-weight women with GDM in the second and third trimesters of pregnancy.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Women Inclusion/Recruitment and Fecal Sample Collection

Women who were treated for GDM in an outpatient clinic at the University Medical Center Ljubljana in 2017 were invited to participate in our longitudinal study (approved by the Slovenian Medical Ethics Committee, No. 0120–323/2016–2). The diagnosis of GDM was based on an OGTT test. The exclusion criterion was at least six months without antibiotic therapy.

Out of 57 recruited GDM women, 45 provided fecal samples in both tested trimesters, 2nd and 3rd trimester. In both trimesters of pregnancy, GDM women were given a fecal collection kit with detailed instructions. The fecal samples collected were immediately stored in their home refrigerators at −20 °C and within 24 h collected and transferred on ice to the laboratory, where the samples were aliquoted, and stored at −80 °C until extraction of the SCFA. 45 GDM women were thoroughly phenotyped (age, BMI preconceptionally, gestational weight gain, insulin, glycated hemoglobin, blood pressure).

2.2. Extraction of SCFA

200 mg of feces were resuspended in 1 mL of 70% ethanol, vortexed and then centrifuged at 2500 rpm, for 10 min at 20 °C. The supernatant was transferred to a new Eppendorf tube and stored at –80 °C until further use, i.e., derivatization.

2.3. Derivatization and HPLC Analysis

Derivatization was performed as previously described [

23]. Briefly, 300 μL of each sample was mixed with 300 μL of reagent 1 (pyridine), reagent 2 (EDC-HCl), and reagent 3 (2-NPH-HCl) and incubated at 60 °C for 20 min, then 200 μL of reagent 4 (potassium hydroxide solution) was added. The mixture was shaken and allowed to react at 60° for 20 min. After the mixture was cooled, 3 mL of aqueous phosphoric acid solution (0.5 M) and 4 mL of ether were added and shaken for 3 min, followed by centrifugation for 15 min (2500 rpm, 20 °C). The upper ether layer was transferred and mixed with 4 mL of MQ water and centrifuged (15 min, 2500 rpm, 20 °C). Subsequently, 1 mL of the ether layer was transferred to a glass vial. The ether was eliminated with N

2. The obtained fatty acid hydrazide was dissolved in 1 mL methanol and 30 μL was subjected to HPLC.

HPLC was performed for simultaneous determination of acetate, propionate, and butyrate. The analyses were performed using a HPLC system (2965 HPLC system; Waters, Milleford, USA), a photodiode array detector (237 nm) and a fluorescence detector (excitation, 331 nm; emission, 500 nm). A C18 HPLC column was used (150 mm x 4.6 mm, particle size 5 µm; Kinetex XB; Phenomenex, Torrance, USA). The flow rate of the mobile phase was 1 mL/min and injection volume were 30 µL. The separation of SCFA was carried at 30 °C out using two eluents: A, 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid in ultra-pure water; B, acetonitrile. A discontinuous gradient was run as follows: 0–0.5 min, 30% B; 0.5–2.0 min, 30–50% B; 2.0–14.0 min, 50% B; 14.0–17.5 min, 50–70% B; 17.5–20.5 min, 70% B; 20.5–22.5 min, 70–100% B; 22.5–62.5 min, 100% B;62.5–63.0 min, 100–30% B; 63.0–65.0 min, 30% B. The retention times were identified by injection of acetate, propionate, and butyrate standards. The peaks of the compounds analyzed in the samples were also confirmed by spiking the samples with commercial standards.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Statistics were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics 26. Normality for each data set was evaluated with the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. The mean ± standard deviation was given for normally distributed data, whereas median value (25th and 75th percentile) was given for non-normally distributed data. Differences in fecal SCFA content among groups were analyzed by the ANOVA test. The correlations between individual parameters were analyzed using Spearman matrices. p-value less than 0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Characteristics of Women with Gestational Diabetes Mellitus

45 women provided fecal samples in their 2nd and 3rd trimester of pregnancy. As can be seen in

Table 1, the women were divided into the groups Normal weight (32 women) and Overweight/obese (13 women) according to their BMI before conception (

p < 0.001). Overweight/obese women gained significantly less weight during pregnancy (GWG) than women with a normal BMI before pregnancy (

p = 0.017). At the time of inclusion in the study (2nd trimester), insulin levels differed significantly between the groups (

p = 0.002) and serum gamma-glutamyl transferase concentrations (0.006), while S-ALT, S-AST, cholesterol, and triglycerides were comparable between the groups. In the second trimester, blood pressure was higher in the overweight/obese group than in the normal weight group, although not significantly. Glycated hemoglobin did not differ between the groups and was stable during pregnancy [

24].

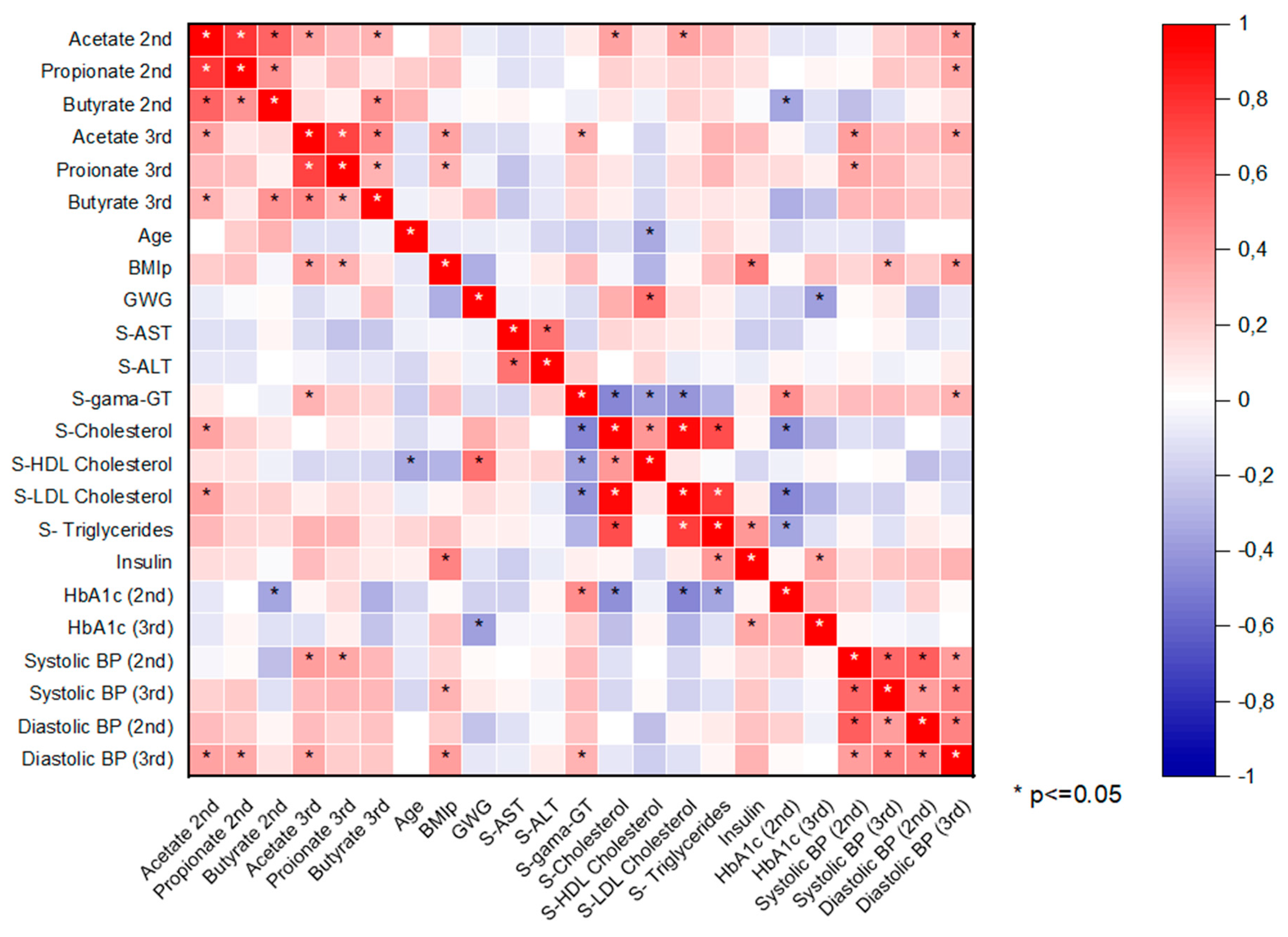

The heat map of the correlation between SCFAs and other variables is shown in

Figure 1. All major SCFAs (acetate, propionate, butyrate) correlated positively with each other in the 2nd and 3rd trimester. Acetate and propionate concentrations correlated positively with BMIp, but significantly only in the 3rd trimester. Acetate concentrations in the 2nd trimester correlated significantly (positive) with 2nd trimester serum cholesterol and serum LDL cholesterol. A positive correlation between acetate concentration and diastolic blood pressure (BP) was observed in both trimesters, although a significant correlation between the parameters was only observed in the 3rd trimester. A significant (negative) correlation was observed between the 2nd trimester butyrate concentrations and the 2nd trimester glycated hemoglobin values. A negative correlation was also observed between the 3rd trimester butyrate and 3rd trimester glycated hemoglobin, but the correlation was not significant. Glycated hemoglobin from the 2nd trimester correlated significantly (positive) with serum gamma-GT concentrations and negatively with cholesterol and triglyceride concentrations. Significant negative correlation between gestational weight gain (GWG) and glycated hemoglobin in the 3rd trimester was observed. Between GWG and 2nd trimester serum HDL cholesterol concentrations a significant positive correlation was seen. 2nd trimester serum gamma-GT correlated significantly (negative) with the 2nd trimester cholesterol values and significantly (positive) with the 2nd trimester glycated hemoglobin. 2nd trimester serum cholesterol concentrations and triglycerides correlated significantly (negative) with the 2nd trimester glycated hemoglobin concentrations. 2nd trimester insulin concentrations correlated significantly (positive) with BMIp and serum triglycerides.

3.2. SCFA in Relation to BMI Preconceptionaly

Two women in the 2nd trimester (one woman from the normal weight group and one from the overweight/obese group) and two in the 3rd trimester (both women from the normal weight group) did not provide a sufficient amount of feces for SCFA analysis. Therefore, of 45 GDM women, the SCFAs of 43 GDM women from the 2nd trimester and 43 GDM women from the 3rd trimester were analyzed. As presented in

Table 2, in total fecal SCFAs (acetate, propionate, and butyrate) differed significantly (

p < 0.05) between tested groups in both trimesters of pregnancy with higher concentrations in overweight/obese group. When analyzing SCFA separately, acetate and propionate differed significantly between groups in both tested trimesters, but not butyrate. SCFA concentrations did not differ significant between second and third trimester of pregnancy. Acetat:Propionat:Butyrate ratio was approx. 65:10:25 in both tested trimesters.

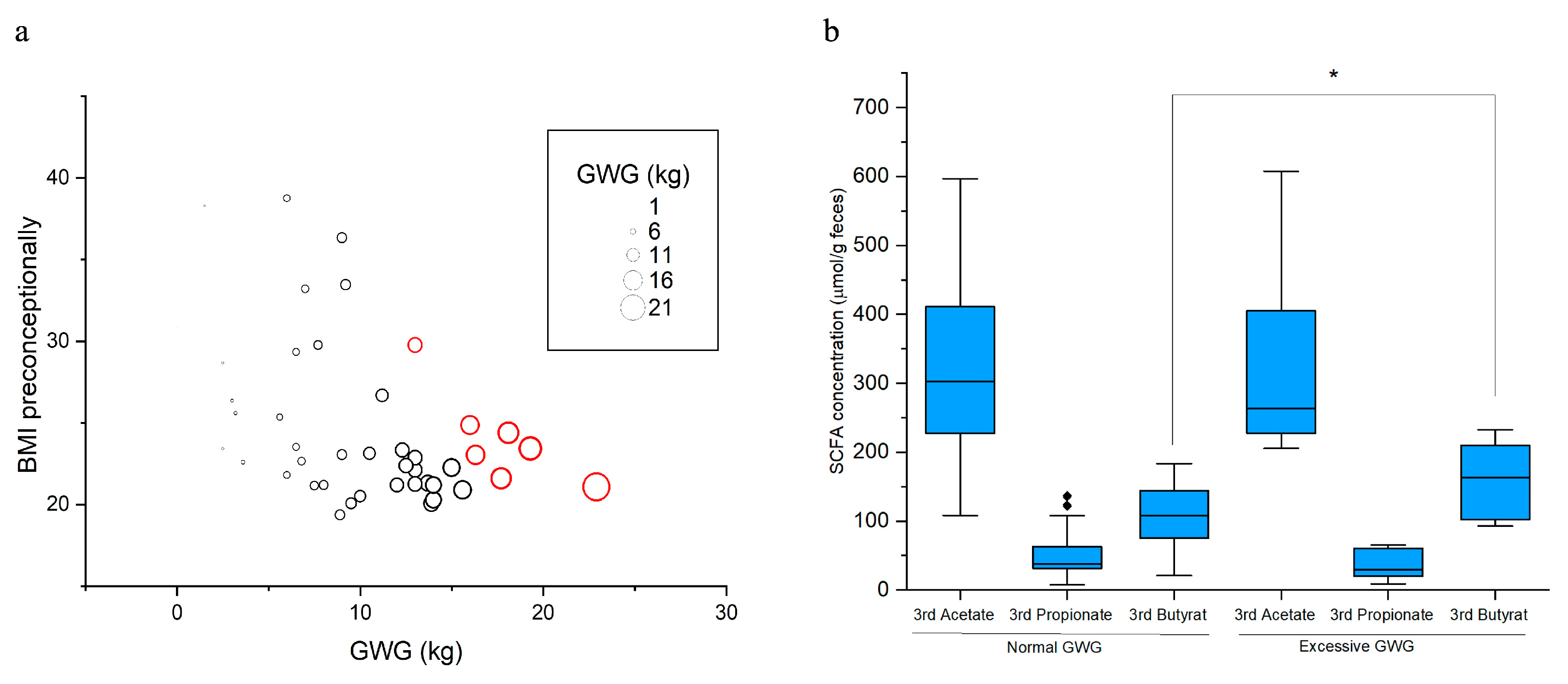

3.3. Butyrate and Excessive Gestational Weight Gain (GWG)

7 GDM women gained excessive weight (gestational weight gain exceeding recommendations, Excessive GWG) and 35 women gained normal weight during pregnancy (

Figure 2a). Groups were determined according to the IOM GWG guidelines [

25]. For two GDM women with normal GWG no data on butyrate concentration in the 3rd trimester were available and for three GDM woman no data on GWG were available. Women with excessive gestational weight gain (7 GDM women) had in third trimester of pregnancy significantly higher concentrations of fecal butyrate when comparing to women with normal gestational weight gain (33 GDM women) (

p = 0.037), but not acetate and propionate (

Figure 2b).

4. Discussion

Due to their importance, SCFA are the subject of many studies, which, however, are often not comparable due to different methodologies, e.g., SCFA concentrations can be reported per dry or wet weight of feces or as mM SCFA in fecal water. Here we report for the first time the concentrations of acetate, propionate, and butyrate in the feces of women with GDM. As the relationship between SCFA and body weight is not yet fully understood, we measured the concentrations of the three major SCFAs and hypothesized that fecal SCFA concentrations will differ between overweight/obese and normal weight pregnant women.

To the best of our knowledge, only three studies have been published that have quantified SCFA from the feces of pregnant women [

19,

25,

27]. Jost and colleagues [

25] found that SCFA concentrations in the feces of pregnant women were elevated compared to literature data that included SCFA analyzes in non-pregnant individuals. Increased SCFA concentrations during pregnancy are thought to reflect metabolic changes and low levels of inflammation, which are considered to be beneficial in the context of a healthy pregnancy [

12,

13,

25]. This may be consistent with our findings, as we measured relatively high concentrations of SCFA (μmol/g feces, wet weight) in the feces of pregnant women with GDM, which are higher than those reported in the literature for a healthy human population, including non-pregnant women [

28,

29,

30].

Høverstad et al. [

28] reported SCFA concentrations per wet weight of feces (mmol/kg feces = μmol/g feces) as 37.4 for acetate, 12.5 for propionate, and 12.4 for butyrate. Fernandes and colleagues [

30] also showed similar SCFA values for wet weight of feces in mmol/kg. The concentrations in our research (311.0 for acetate, 48.7 for propionate, and 120.5 for butyrate) were much higher. Higher concentrations could be due to pregnancy, but it is probably reasonable to also look for causes in the type of sampling, sample preparation and method chosen. Furthermore, in the studies mentioned above, SCFA were analyzed by gas chromatography, whereas in our study we analyzed SCFA by HPLC.

Instead of concentrations, the ratio between acetate, propionate, and butyrate (acetate:propionate:butyrate) is mentioned in the literature, which is about 60:20–25:15–20 in healthy people [

31,

32,

33,

34]. Jost et al. [

25] determined a slightly different ratio between the three basic SCFA in the feces of pregnant women, namely 65:15:20. Compared to studies with healthy, non-pregnant individuals, slightly more acetate and less propionate was measured. In our study, we obtained a similar ratio of 65:10:25. Compared to healthy people, the ratio differs mainly in propionate, which is present in lower concentrations in pregnant women [

19,

26] and pregnant women with GDM. Inulin propionate ester, which delivers propionate specifically to the large intestine, has been shown to reduce energy intake and prevent long-term weight gain in overweight adults. In addition, supplementation with inulin propionate significantly improved acute insulin secretion and β-cell function. This suggests that increasing colonic propionate improves glucose metabolism [

35,

36]. It is possible that the reduction of propionate in pregnant women is an adaptation of the gut microbiota to pregnancy, which allows an increase in insulin resistance and ensures an adequate supply of nutrients to the fetus. It should be noted that SCFA concentrations in our study did not differ significantly between trimesters of pregnancy.

Pregnant women with GDM and normal body weight before conception had significantly lower levels of acetate and propionate in feces in both trimesters of pregnancy compared to pregnant women who were overweight or obese before conception. This is consistent with a number of studies that do not exclusively support a beneficial role for SCFA. Metabolites of SCFA oxidation can be used for de novo lipid and glucose synthesis [

20] and epidemiological studies in mice have shown that higher fecal SCFA concentrations are positively correlated with higher body weight, whereas lower SCFA values are associated with leanness [

22,

29,

37]. In addition, metagenomic studies have shown that in obese humans, the gut microbiome is enriched in pathways involving microbial fermentation of carbohydrates [

22].

Pregnant women with excessive weight gain during pregnancy had significantly higher butyrate concentrations in their feces in the third trimester compared to pregnant women with normal gestational weight gain (

Figure 2b). Excessive weight gain during pregnancy increases the risk of a caesarean section, the birth of a macrosomic child, more difficult weight loss after birth and also obesity in the child later in life [

38,

39,

40]. Butyrate has been shown to influence the prevention of obesity and insulin resistance via the regulation of gut hormones [

41,

42]. More recently, butyrate has received particular attention due to its positive effects on intestinal homeostasis, but the role of butyrate in relation to weight gain and obesity remains controversial [

43].

In our study, acetate and propionate concentrations were significantly higher in pregnant women who were overweight or obese before pregnancy compared to normal-weight women, but butyrate concentrations were not. These were elevated in the 3rd trimester in the excessive gestational weight group. In our study, overweight and obese pregnant women gained significantly less weight during pregnancy than those who had a normal weight before pregnancy. Perhaps the overweight/obese pregnant women were additionally motivated by participating in the study. The pregnant women were properly instructed and educated about a healthy diet [

24], although patients and healthcare professionals are aware of the lack of care due to staff shortages in general in Slovenia [

44], and probably additional education and information would be in place. Regardless the conflicting publications on the role of SCFA, our study showed that higher acetate and propionate levels were associated with pre-pregnancy obesity and higher butyrate levels were associated with excessive weight gain during pregnancy.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.S.E., D.Ž.B., D.P.B. and J.A.A.; methodology, K.M., M.L. and J.A.A.; validation, M.S.E. and D.Ž.B.; formal analysis, K.M., M.L. and D.P.B.; investigation, K.M. and M.L.; resources, D.Ž.B, M.S.E. and D.P.B., data curation, K.M. and J.A.A.; writing—original draft preparation, K.M.; writing—review and editing, K.M., M.L., M.S.E., J.A.A. and D.P.B.; visualization, K.M.; supervision, D.Ž.B.; project administration, D.P.B. and J.A.A.; funding acquisition, D.Ž.B. and D.P.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Slovenian Research Agency (ARIS), national program grant P1-0198. Katja Molan was a recipient of a PhD grant from the Slovene Research Agency.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Slovenian Medical Ethics Committee, No. 0120–323/2016–2.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all study participants for their willingness to provide fecal samples. We would also like to thank all the medical staff who helped with recruitment, especially the nurse Melita Cajhen.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Koh, A.; De Vadder, F.; Kovatcheva-Datchary, P.; Ba¨ckhed, F. From dietary fiber to host physiology: Short-chain fatty acids as key bacterial metabolites. Cell 2016, 165, 1332–1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trompette, A.; Gollwitzer, E.S.; Yadava, K.; Sichelstiel, A.K.; Sprenger, N.; Ngom-Bru, C. Gut microbiota metabolism of dietary fiber influences allergic airway disease and hematopoiesis. Nat. Med. 2014, 20, 159–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Louis, P.; Hold, G.L.; Flint, H.J. The gut microbiota, bacterial metabolites and colorectal cancer. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2014, 10, 661–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, Y.; He, C.; An, Y.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Fu, W.; Wang, M.; Shan, Z.; Xie, J.; Yang, Y.; et al. The Role of Short Chain Fatty Acids in Inflammation and Body Health. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 7379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Canani, R.B.; Di Costanzo, M.; Leone, L.; Pedata, M.; Meli, R.; Calignan, A. Potential beneficial effects of butyrate in intestinal and extraintestinal diseases. J. Gastroenterol 2011, 17, 1519–1528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, R.A. and Riber, L. Epigenetic effects of short-chain fatty acids from the large intestine on host cells. Microlife 2023, 4, uqad032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Diabetes Association Professional Practice Committee; 2. Diagnosis and Classification of Diabetes: Standards of Care in Diabetes—2024. Diabetes Care 2024, 47, S20–S42. [CrossRef]

- Bener, A.; Saleh, N.M.; Al-Hamaq, A. Prevalence of gestational diabetes and associated maternal and neonatal complications in a fast-developing community: Global comparisons. Int J Womens Health 2011, 3, 367–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bellamy, L.; Casas, J.-P.; Hingorani, A.D.; William, D. Type 2 diabetes mellitus after gestational diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet 2009, 373, 1773–1779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rayanagoudar, G.; Hashi, A.A.; Zamora, J.; Khalid, S. Quantification of the type 2 diabetes risk in women with gestational diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis of 95,750 women. Diabetologia 2016, 59, 1403–1411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soderborg, T.K.; Borengasser, S.J.; Barbour, L.A. Microbial transmission from mothers with obesity or diabetes to infants: An innovative opportunity to interrupt a vicious cycle. Diabetologia 2016, 59, 895–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koren, O.; Goodrich, J.K.; Cullender, T.C.; Spor, A.; Laitinen, K.; Kling Bäck, H.; Ruth, L. Host remodeling of the gut microbiome and metabolic changes during pregnancy. Cell 2012, 150, 470–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priyadarshini, M.; Thomas, A.; Reisetter, A.C.; Scholtens, D.M.; Wolever, T.M.; Josefson, J.L.; Layden, B.T. Maternal short-chain fatty acids are associated with metabolic parameters in mothers and newborns. Transl Res. 2014, 164, 153–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziętek, M.; Celewicz, Z.; Szczuko, M. Short-Chain Fatty Acids, Maternal Microbiota and Metabolism in Pregnancy. Nutrients, 2021, 9, 1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez-Arango, L.F.; Barrett, H.L.; McIntyre, H.D.; Callaway, L.K.; Morrison, M.; Dekker Nitert, M.; SPRING Trial Group. Connections Between the Gut Microbiome and Metabolic Hormones in Early Pregnancy in Overweight and Obese Women. Diabetes 2016, 65, 2214–2223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.; He, F.J.; Dong, Y.; Huang, Y.; Wang, C.; Harshfield, G.A.; Zhu, H. Modest Sodium Reduction Increases Circulating Short-Chain Fatty Acids in Untreated Hypertensives: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial. Hypertension 2020, 76, 73–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laznik, G. and Reisp, M. Arterial hypertension and pulse wave velocity. Pielegniarstwo XXI wieku 2023, 22, 14–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuller, M.; Gomez-Arango, M.; Gibbons, S.M.; Angueira, A.R.; Brodsky, M.; Hayes, M.G.; Kovatcheva-Datchary, P.; Bäckhed, F.; Gilbert, J.A.; Lowe, W.L., Jr.; Layden, B.T. The short-chain fatty acid receptor, FFA2, contributes to gestational glucose homeostasis. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2015, 309, E840–E851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szczuko, M.; Kikut, J.; Maciejewska, D.; Kulpa, D.; Celewicz, Z.; Ziętek, M. The Associations of SCFA with Anthropometric Parameters and Carbohydrate Metabolism in Pregnant Women. Int J Mol Sci. 2020, 21, 9212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNeil, N.I. The contribution of the large intestine to energy supplies in man. Am. J. Clin. 1984, 39, 338–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.N.; Yao, Y.; Ju, S.Y. Short Chain Fatty Acids and Fecal Microbiota Abundance in Humans with Obesity: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turnbaugh, P.J.; Hamady, M.; Yatsunenko, T.; Cantarel, B.L.; Duncan, A.; Ley, R.E.; Sogin, M.L.; Jones, W.J.; Roe, B.A.; Affourtit, J.P. A core gut microbiome in obese and lean twins. Nature 2009, 457, 480–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torii, T.; Kanemitsu, K.; Wada, T.; Itoh, S.; Kinugawa, K.; Hagiwara, A. Measurement of short-chain fatty acids in human faeces using high-performance liquid chromatography: Specimen stability. Ann. Clin. Biochem. 2010, 47, 447–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Munda, A.; Starčič Erjavec, M.; Molan, K.; Ambrožič Avguštin, J.; Žgur Bertok, D.; Pongrac Barlovič, D. Association between pre-pregnancy body weight and dietary pattern with large-for-gestational-age infants in gestational diabetes. Diabetol. Metab. Syndr. 2019, 22, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Institute of Medicine (US) and National Research Council (US) Committee to Reexamine IOM Pregnancy Weight Guidelines. Weight Gain During Pregnancy: Reexamining the Guidelines. Editor 1, Rasmussen, K.M.; Editor 2, Yaktine, A.L., Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2009, PMID: 20669500.

- Jost, T.; Lacroix, C.; Braegger, C.; Chassard, C. Stability of the maternal gut microbiota during late pregnancy and early lactation. Curr Microbiol. 2014, 68, 419–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rautava, S.; Selma-Royo, M.; Oksanen, T.; Collado, M.C.; Isolauri, E. Shifting pattern of gut microbiota in pregnant women two decades apart—An observational study. Gut Microbes, 2023, 15, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Høverstad, T.; Fausa, O.; Bjørneklett, A.; Bøhmer, T. Short-chain fatty acids in the normal human feces. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1984, 19, 375–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwiertz, A.; Taras, D.; Schafer, K.; Beijer, S.; Bos, N.A.; Donus, C.; Hardt, P.D. ; Microbiota and SCFA in lean and overweight healthy subjects. Obesity 2010, 18, 190–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, J.; Su, W.; Rahat-Rozenbloom, S.; Wolever, T.M.S.; Comelli, E.M. Adiposity, gut microbiota and faecal short chain fatty acids are linked in adult humans. Nutr. and Diabetes. 2014, 4, e1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummings, J.H. Short chain fatty acids in the human colon. Gut 1981, 22, 763–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cook, S.I. and Sellin, J.H. Review article: Short chain fatty acids in health and disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1998, 12, 499–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hijova, E. and Chmelarova, A. Short chain fatty acids and colonic health. Bratisl Lek Listy 2007, 108, 354–358. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- den Besten, G.; van Eunen, K.; Groen, A.K.; Venema, K.; Reijngoud, D.J.; Bakker, B.M. The role of short-chain fatty acids in the interplay between diet, gut microbiota, and host energy metabolism. J. Lipid. Res. 2013, 54, 2325–2340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chambers, E.S.; Viardot, A.; Psichas, A.; Morrison, D.J.; Murphy, K.G.; Zac-Varghese, S.E.; MacDougall, K.; Preston, T.; Tedford, C.; Finlayson, G.S.; et al. Effects of targeted delivery of propionate to the human colon on appetite regulation, body weight maintenance and adiposity in overweight adults. Gut, 2015, 64, 1744–1754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pingitore, A.; Chambers, E.S.; Hill, T.; Maldonado, I.R.; Liu, B.; Bewick, G.; Morrison, D.J.; Preston, T.; Wallis, G.A.; Tedford, C.; et al. The diet-derived short chain fatty acid propionate improves beta-cell function in humans and stimulates insulin secretion from human islets in vitro. Diabetes Obes Metab 2017, 19, 257–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahat-Rozenbloom, S.; Fernandes, J.; Gloor, G.B.; Wolever, T.M.S. Evidence for greater production of colonic short-chain fatty acids in overweight than lean humans. Int. J. Obes. 2014, 38, 1525–1531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; Health and Medicine Division; Food and Nutrition Board; Harrison M, editor. Nutrition During Pregnancy and Lactation: Exploring New Evidence: Proceedings of a Workshop—In Brief. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US) 2020, Washington DC, National Academies Press, 481. [CrossRef]

- Galjaard, S.; Pexsters, A.; Devlieger, R.; Guelinckx, I.; Abdallah, Y.; Lewis, C.; van Calster, B.; Bourne, T.; Timmerman, D.; Luts, J. The influence of weight gain patterns in pregnancy on fetal growth using cluster analysis in an obese and nonobese population. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2013, 21, 1416–1422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kominiarek, M.A. and Peaceman, A.M. Gestational Weight Gain. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017, 217, 642–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samuel, B.S.; Shaito, A.; Motoike, T.; Rey, F.E.; Backhed, F.; Manchester, J.K.; Hammer, R.E.; Williams, S.C.; Crowley, J.; Yanagisawa, M.; et al. Effects of the gut microbiota on host adiposity are modulated by the short-chain fatty-acid binding G protein-coupled receptor, Gpr41. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2008, 105, 16767–16772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McNabney, S.M. and Henagan, T.M. Short Chain Fatty Acids in the Colon and Peripheral Tissues: A Focus on Butyrate, Colon Cancer, Obesity and Insulin Resistance. Nutrients 2017, 9, 1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.; Wang, J.; He, T.; Becker, S.; Zhang, G.; Li, D.; Ma, X. Butyrate: A Double-Edged Sword for Health? Adv. nutr. 2018, 9, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šimec, M.; Krsnik, S. , Erjavec, K. Quality of health care and interdisciplinary collaboration from the perspective of employees and patients. Pielegniarstwo XXI wieku 2023, 22, 221–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).