Submitted:

28 January 2025

Posted:

28 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

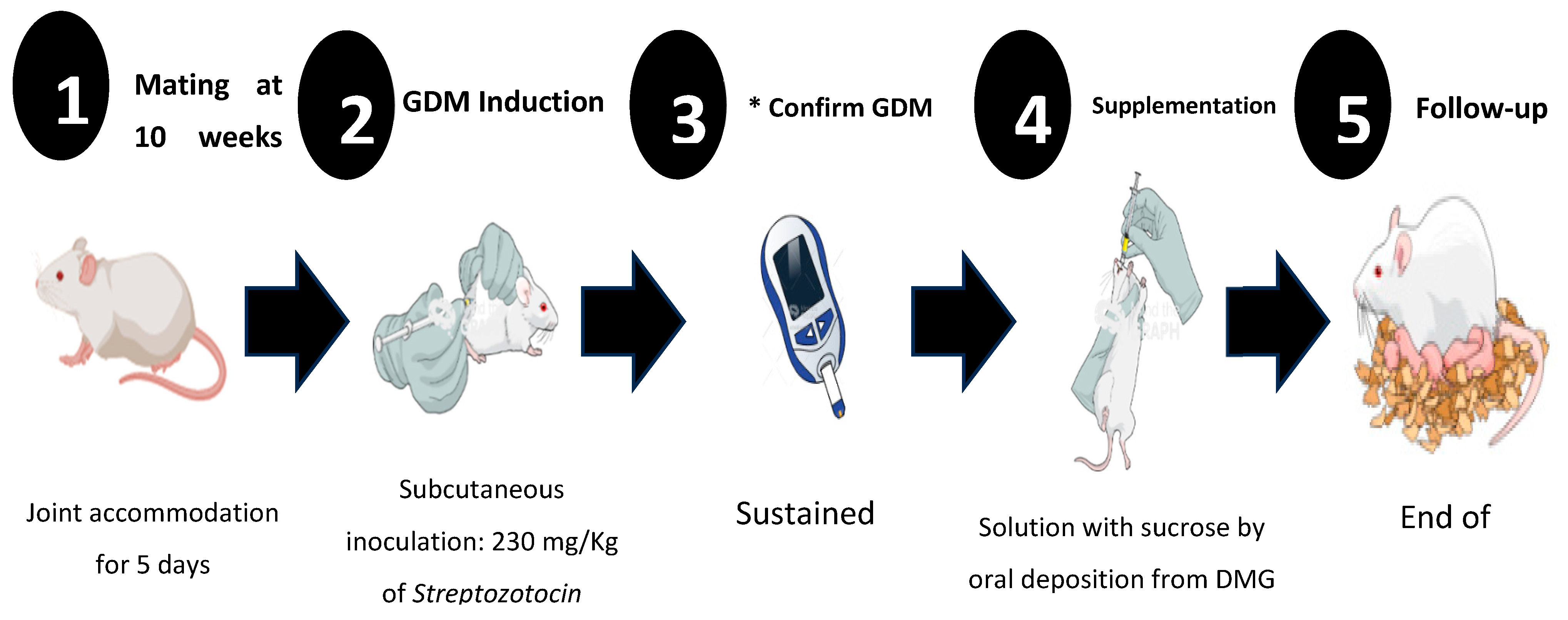

Study Design

Study Groups

Gestational Diabetes Mellitus Induction

Sucrose Supplementation

Calculation and Determination of Metabolic Parameters

Immunity Components Quantification

Redox Capacity Quantification

Statistical Analysis

3. Results

Morphometric Values and Glycemia

Metabolic Parameters

Insulin, Adiponectin, Leptin and HOMA-IR Index

Immune Parameters

Redox Activity

Oxidants Parameters

4. Discussion

Changes in Weight and BMI Related to GDM

Insulin Resistance and GDM

Metabolic Changes During GDM

Immune Response in GDM

Changes in Humoral Response During GDM

Modifications of Redox Mechanisms During GDM

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kanguru L, Bezawada N, Hussein J, Bell J. The burden of diabetes mellitus during pregnancy in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review. Glob Health Action. 2014; 7: 23987. [CrossRef]

- Silva-Zolezzi I, Samuel TM, Spieldenner J. Maternal nutrition: opportunities in the prevention of gestational diabetes. Nutr Rev. 2017; 75(1): 32-50. [CrossRef]

- International Diabetes Federation. IDF Diabetes Atlas, 8th edition. Brussels, Belgium: International Diabetes Federation, 2017 [Consultado 2020 Jul 20] Available in: http://www.diabetesatlas.org.

- Moon JH, Kwak SH, Jang HC. Prevention of type 2 diabetes mellitus in women with previous gestational diabetes mellitus. Korean J Intern Med. 2017; 32(1): 26-41. [CrossRef]

- American Diabetes Association Professional Practice Committee. 2. Classification and Diagnosis of Diabetes: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes-2022. Diabetes Care. 2022; 45(Suppl 1): S17-S38. [CrossRef]

- Ye W, Luo C, Huang J, Li C, Liu Z, Liu F. Gestational diabetes mellitus and adverse pregnancy outcomes: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2022; 377: e067946. [CrossRef]

- Greco E, Calanducci M, Nicolaides KH, Barry EVH, Huda MSB, Iliodromiti S. Gestational diabetes mellitus and adverse maternal and perinatal outcomes in twin and singleton pregnancies: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2024; 230(2): 213-225. [CrossRef]

- Ornoy A, Becker M, Weinstein-Fudim L, Ergaz Z. Diabetes during Pregnancy: A Maternal Disease Complicating the Course of Pregnancy with Long-Term Deleterious Effects on the Offspring. A Clinical Review. Int J Mol Sci. 2021; 22(6):2965. [CrossRef]

- Trumbo P, Schlicker S, Yates AA, Poos M. Food and Nutrition Board of the Institute of Medicine, The National Academies. Dietary reference intakes for energy, carbohydrate, fiber, fat, fatty acids, cholesterol, protein and amino acids. J Am Diet Assoc. 2002; 102(11): 1621-30. [CrossRef]

- Petersohn I, Hellinga AH, van Lee L, Keukens N, Bont L, Hettinga KA, et al. Maternal diet and human milk composition: an updated systematic review. Front Nutr. 2024; 10: 1320560. [CrossRef]

- Lovegrove A, Edwards CH, De Noni I, Patel H, El SN, Grassby T, et al. Role of polysaccharides in food, digestion, and health. Crit. Rev. Food Sci Nutr. 2017; 57(2): 237-253. [CrossRef]

- Mustad VA, Huynh DT, López-Pedrosa JM, Campoy C, Rueda R. The role of dietary carbohydrates in Gestational Diabetes. Nutrients. 2020; 12(2): 385. [CrossRef]

- Lekva T, Norwitz ER, Aukrust P, Ueland T. Impact of systemic inflammation on the progression of gestational diabetes mellitus. Curr Diab Rep. 2016; 16(4): 26. [CrossRef]

- Richardson AC, Carpenter MW. Inflammatory mediators in gestational diabetes mellitus. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2007; 34(2): 213-224. [CrossRef]

- Saito S, Nakashima A, Shima T, Ito M: Th1/Th2/Th17 and regulatory T-Cell paradigm in pregnancy. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2010; 63(6): 601-10. [CrossRef]

- Mor G. Introduction to the immunology of pregnancy. Immunol Rev. 2022; 308(1): 5 - 8. [CrossRef]

- Barbour LA, McCurdy CE, Hernandez TL, Kirwan JP, Catalano PM, Friedman JE. Cellular mechanisms for insulin resistance in normal pregnancy and gestational diabetes. Diabetes Care 2007; 30 (2): S112-9. [CrossRef]

- Kim JH, Bachmann RA, Chen J. Interleukin-6 and insulin resistance. Vitam. Horm. 2009; 80: 613-33. [CrossRef]

- Kirwan JP, Hauguel-De Mouzon S, Lepercq J, Challier JC, Huston-Presley L, Friedman JE, et al. TNF-alpha is a predictor of insulin resistance in human pregnancy. Diabetes 2002; 51: 2207-2213. [CrossRef]

- Khalid M, Petroianu G, Adem A. Advanced Glycation End Products and Diabetes Mellitus: Mechanisms and Perspectives. Biomolecules. 2022; 12(4): 542. [CrossRef]

- Harsem NK, Braekke K, Torjussen T, Hanssen K, Staff AC. Advanced glycation end products in pregnancies complicated with diabetes mellitus or preeclampsia. Hypertense Pregnancy. 2008; 24(8): 374-86. [CrossRef]

- [NOM-062-ZOO-1999]. Diario Oficial de la Federación, México. 15. Organización Mundial de Sanidad Animal. Available in: https://www.gob.mx/cms/uploads/attachment/file/203498/NOM-062-ZOO-1999_220801.pdf.

- Percie du Sert N, Hurst V, Ahluwalia A, Alam S, Avey MT, Baker M, et al. The ARRIVE guidelines 2.0: Updated guidelines for reporting animal research. Br J Pharmacol. 2020; 177(16): 3617-3624. [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Carrillo BE, Rosales-Gómez CA, Ramírez-Durán N, Reséndiz-Albor AA, Escoto-Herrera JA, Mondragón-Velásquez T, et al. Effect of Chronic Consumption of Sweeteners on Microbiota and Immunity in the Small Intestine of Young Mice. Int J Food Sci. 2019: 9619020. [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez-Pliego LE, Martínez-Carrillo BE, Reséndiz-Albor AA, Arciniega-Martínez IM, Escoto-Herrera JA, Rosales-Gómez CA, et al. Effect of Supplementation with n-3 Fatty Acids Extracted from Microalgae on Inflammation Biomarkers from Two Different Strains of Mice. J Lipids. 2018:4765358. [CrossRef]

- ElSayed NA, Aleppo G, Aroda VR, Bannuru RR, Brown FM, Bruemmer D, et al. on behalf of the American Diabetes Association. 2. Classification and Diagnosis of Diabetes: Standards of Care in Diabetes-2023. Diabetes Care. 2023; 46(Suppl 1): S19-S40. [CrossRef]

- Rosales-Gómez CA, Martínez-Carrillo BE, Reséndiz-Albor AA, Ramírez-Durán N, Valdés-Ramos R, Mondragón-Velásquez T, et al. Chronic Consumption of Sweeteners and Its Effect on Glycaemia, Cytokines, Hormones, and Lymphocytes of GALT in CD1 Mice. Biomed Res Int. 2018. 1345282. [CrossRef]

- Vilela BS, Vasques AC, Cassani RS, Forti AC, Pareja JC, Tambascia MA, et al. The HOMA-Adiponectin (HOMA-AD) Closely Mirrors the HOMA-IR Index in the Screening of Insulin Resistance in the Brazilian Metabolic Syndrome Study (BRAMS). PLoS One. 2016; 11(8): e0158751. [CrossRef]

- Carrizales-Luna JE, Reséndiz-Albor AA, Arciniega-Martínez IM, Gómez-López M, Campos-Rodríguez R, Pacheco-Yépez J, et al. Outcomes of nicotinic modulation on markers of intestinal IgA antibody response. Biomed Rep. 2022. 18(2): 13. [CrossRef]

- García-Iniesta L, Martínez-Carrillo BE, Valdés-Ramos R, Jarillo-Luna RA, Escoto-Herrera JA, Reséndiz-Albor AA. Relationship between Prolonged Sweetener Consumption and Chronic Stress in the Production of Carbonylated Proteins in Blood Lymphocytes. EJNFS. 2017. 7(4): 220-232. [CrossRef]

- Soma-Pillay P, Nelson-Piercy C, Tolppanen H, Mebazaa A. Physiological changes in pregnancy. Cardiovasc J Afr. 2016; 27(2): 89-94. [CrossRef]

- Baz B, Riveline JP., Gautier JF. Endocrinology of Pregnancy: Gestational diabetes mellitus: Definition, aetiological and clinical aspects. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 2016; 174: R43-R51. [CrossRef]

- Chandra M, Paray AA. Natural Physiological Changes During Pregnancy. Yale J Biol Med. 2024; 97(1): 85-92. [CrossRef]

- Plows JF, Stanley JL, Baker PN, Clare MR, Vickers MH. The Pathophysiology of Gestational Diabetes Mellitus. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018; 19: 3342. [CrossRef]

- Ryckman KK, Borowski KS, Parikh NI, Saftlas AF. Pregnancy Complications and the Risk of Metabolic Syndrome for the Offspring. Curr Cardiovasc Risk Rep. 2013; 7(3): 217-223. [CrossRef]

- Xiang AH, Li BH, Black MH, Sacks DA, Buchanan TA, Jacobsen SJ, et al. Racial and ethnic disparities in diabetes risk after gestational diabetes mellitus. Diabetologia. 2011; 54: 3016-3021. [CrossRef]

- Pintaudi B, Fresa R, Dalfra M, Dodesini AR, Vitacolonna E, Tumminia A, et al. The risk stratification of adverse neonatal outcomes in women with gestational diabetes (STRONG) study. Acta Diabetol. 2018; 55: 1261-1273. [CrossRef]

- Mousa A, Naqash A, Lim S. Macronutrient and Micronutrient Intake during Pregnancy: An Overview of Recent Evidence. Nutrients. 2019; 11: 443. [CrossRef]

- Jovanovic-Peterson L, Peterson CM., Reed GF, Metzger BE, Mills JL, Knopp RH, et al. The National Institute of Child Health and Human Development—Diabetes in Early Pregnancy Study Maternal postprandial glucose levels and infant birth weight: The Diabetes in Early Pregnancy Study. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 1991; 164:103-111. [CrossRef]

- Gou BH, Guan HM, Bi YX, Ding BJ. Gestational diabetes: weight gain during pregnancy and its relationship to pregnancy outcomes. Chin Med J (Engl). 2019; 132(2): 154-160. [CrossRef]

- Rayanagoudar G, Hashi AA, Zamora J, Khan KS, Hitman GA, Thangaratinam S. Quantification of the type 2 diabetes risk in women with gestational diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis of 95,750 women. Diabetologia. 2016; 59: 1403-1411. [CrossRef]

- Mat SHC, Yaacob NM, Hussain S. Rate of weight gain and its association with homeostatic model assessment-insulin resistance (HOMA-IR) among obese children attending Paediatric Endocrine Clinic, Hospital Universiti Sains Malaysia. J. ASEAN Fed. Endocr. Soc. 2021; 36: 149-155. [CrossRef]

- Duo Y, Song S, Zhang Y, Qiao X, Xu J, Zhang J, et al. Predictability of HOMA-IR for Gestational Diabetes Mellitus in Early Pregnancy Based on Different First Trimester BMI Values. J Pers Med. 2022; 13(1): 60. [CrossRef]

- Powe CE, Allard C, Battista MC, Doyon M, Bouchard L, Ecker JL, et al. Heterogeneous contribution of insulin sensitivity and secretion defects to gestational Diabetes Mellitus. Diabetes Care. 2016; 39(6): 1052-5. [CrossRef]

- Cheney C, Shragg P, Hollingsworth D. Demonstration of heterogeneity in gestational Diabetes by a 400-kcal breakfast meal tolerance test. Obstet Gynecol. 1985; 65(1): 17-23. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3880878/.

- Hashemipour S, Zohal M, Modarresnia L, Kolaji S, Panahi H, Badri M, et al. The yield of early-pregnancy homeostasis of model assessment -insulin resistance (HOMA-IR) for predicting gestational diabetes mellitus in different body mass index and age groups. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2023; 23(1): 822. [CrossRef]

- Rieck S, Kaestner KH. Expansion of beta-cell mass in response to pregnancy. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2010; 21: 151-158. [CrossRef]

- Usman TO, Chhetri G, Yeh H, Dong HH. Beta-cell compensation and gestational diabetes. J Biol Chem. 2023; 299(12): 105405. [CrossRef]

- Inoue S, Kozuma Y, Miyahara M, Yoshizato T, Tajiri Y, Hori D, et al. Pathophysiology of gestational Diabetes Mellitus in lean Japanese pregnant women in relation to insulin secretion or insulin resistance. Diabetol Int. 2020; 11: 269-73. [CrossRef]

- Štambuk T, Kifer D, Smirčić-Duvnjak L, Vučić Lovrenčić M, Gornik O. Associations between plasma protein, IgG and IgA N-glycosylation and metabolic health markers in pregnancy and gestational diabetes. PLoS One. 2023; 18(4): e0284838. [CrossRef]

- Luo N, Liu J, Chung BH, Yang Q, Klein RL, Garvey WT, et al. Macrophage Adiponectin Expression Improves Insulin Sensitivity and Protects Against Inflammation and Atherosclerosis. Diabetes. 2010; 59: 791-799. [CrossRef]

- McElwain CJ, McCarthy FP, McCarthy CM. Gestational Diabetes Mellitus and Maternal Immune Dysregulation: What We Know So Far. Int J Mol Sci. 2021; 22(8): 4261. [CrossRef]

- Atègbo JM, Grissa O, Yessoufou A, Hichami A, Dramane KL, Moutairou K, et al. Modulation of Adipokines and Cytokines in Gestational Diabetes and Macrosomia. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2006; 91: 4137-4143. [CrossRef]

- Christian LM, Porter K. Longitudinal changes in serum proinflammatory markers across pregnancy and postpartum: Effects of maternal body mass index. Cytokine. 2014; 70: 134-140. [CrossRef]

- Moyce Gruber BL, Dolinsky VW. The Role of Adiponectin during Pregnancy and Gestational Diabetes. Life (Basel). 2023; 13(2): 301. [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Pérez A., Vilariño-García T., Guadix P., Dueñas J.L., Sánchez-Margalet V. Leptin and nutrition in gestational diabetes. Nutrients. 2020; 12: 1970. [CrossRef]

- De Gennaro G, Palla G, Battini L, Simoncini T, Del Prato S, Bertolotto A, et al. The role of adipokines in the pathogenesis of gestational diabetes mellitus. Gynecol. Endocrinol. 2019; 35: 737-751. [CrossRef]

- Bao W, Baecker A, Song Y, Kiely M, Liu S, Zhang C. Adipokine levels during the first or early second trimester of pregnancy and subsequent risk of gestational diabetes mellitus: A systematic review. Metabolism. 2015; 64: 756-764. [CrossRef]

- Xu J, Zhao YH, Chen YP, Yuan XL, Wang J, Zhu H, et al. Maternal circulating concentrations of tumor necrosis factor-alpha, leptin, and adiponectin in gestational diabetes mellitus: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci. World J. 2014; 2014: 926932. [CrossRef]

- Mor G, Cardenas I, Abrahams V, Guller S. Inflammation and pregnancy: The role of the immune system at the implantation site. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2011; 1221: 80-87. [CrossRef]

- Berbudi A, Rahmadika N, Tjahjadi AI, Ruslami R. Type 2 diabetes and its impact on the immune system. Curr. Diabetes Rev. 2020; 16: 442-449. [CrossRef]

- Sheu A, Chan Y, Ferguson A, Bakhtyari MB, Hawke W, White C, et al. A proinflammatory CD4(+) T cell phenotype in gestational diabetes mellitus. Diabetologia. 2018; 61: 1633-1643. [CrossRef]

- Abell SK, De Courten B, Boyle JA, Teede HJ. Inflammatory and Other Biomarkers: Role in Pathophysiology and Prediction of Gestational Diabetes Mellitus. Int J Mol Sci. 2015; 16(6): 13442-73. [CrossRef]

- Sifnaios E, Mastorakos G, Psarra K, Panagopoulos ND, Panoulis K, Vitoratos N, et al. Gestational Diabetes and T-cell (Th1/Th2/Th17/Treg) immune profile. In Vivo. 2019; 33: 31-40. [CrossRef]

- Seck A, Hichami A, Doucouré S, Diallo Agne F, Bassène H, Ba A, et al. Th1/Th2 Dichotomy in Obese Women with Gestational Diabetes and Their Macrosomic Babies. J Diabetes Res. 2018; 2018: 8474617. [CrossRef]

- Winer DA, Winer S, Chng MH, Shen L, Engleman EG. B Lymphocytes in obesity-related adipose tissue inflammation and insulin resistance. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2014; 71: 1033-1043. [CrossRef]

- Nikolajczyk BS, Jagannathan-Bogdan M, Shin H, Gyurko R. State of the union between metabolism and the immune system in type 2 diabetes. Genes Immun. 2011; 12: 239-250. [CrossRef]

- Palming J, Gabrielsson BG, Jennische E, Smith U, Carlsson B, Carlsson LM, et al. Plasma cells and Fc receptors in human adipose tissue--lipogenic and anti-inflammatory effects of immunoglobulins on adipocytes. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2006; 343: 43-48. [CrossRef]

- Liang W, Qi Y, Yi H, Mao C, Meng Q, Wang H, et al. The Roles of Adipose Tissue Macrophages in Human Disease. Front Immunol. 2022; 13: 908749. [CrossRef]

- Zhuang Y, Zhang J, Li Y, Gu H, Zhao J, Sun Y, et al. B Lymphocytes Are Predictors of Insulin Resistance in Women with Gestational Diabetes Mellitus. Endocr Metab Immune Disord Drug Targets. 2019; 19(3): 358-366. [CrossRef]

- Luck H, Khan S, Kim JH, Copeland JK, Revelo XS, Tsai S, et al. Gut-associated IgA+ immune cells regulate obesity-related insulin resistance. Nat Commun. 2019; 10(1): 3650. [CrossRef]

- Štambuk T, Kifer D, Smirčić-Duvnjak L, Vučić Lovrenčić M, Gornik O. Associations between plasma protein, IgG and IgA N-glycosylation and metabolic health markers in pregnancy and gestational diabetes. PLoS One. 2023; 18(4): e0284838. [CrossRef]

- Nishikawa T, Edelstein D, Du XL, Yamagishi S, Matsumura T, Kaneda Y, et al. Normalizing mitochondrial superoxide production blocks three pathways of hyperglycaemic damage. Nature. 2000; 404: 787-790. [CrossRef]

- Sadowska J, Dudzińska W, Dziaduch I. Effects of different models of sucrose intake on the oxidative status of the uterus and ovary of rats. PLoS One. 2021; 16(5): e0251789. [CrossRef]

- Saucedo R, Ortega-Camarillo C, Ferreira-Hermosillo A, Díaz-Velázquez MF, Meixueiro-Calderón C, Valencia-Ortega J. Role of Oxidative Stress and Inflammation in Gestational Diabetes Mellitus. Antioxidants (Basel). 2023; 12(10): 1812. [CrossRef]

- Batty M, Bennett MR, Yu E. The Role of Oxidative Stress in Atherosclerosis. Cells. 2022; 11(23): 3843. [CrossRef]

- Maciejczyk M, Matczuk J, Żendzian-Piotrowska M, Niklińska W, Fejfer K, Szarmach I, et al. Eight-Week Consumption of High-Sucrose Diet Has a Pro-Oxidant Effect and Alters the Function of the Salivary Glands of Rats. Nutrients. 2018; 10: 1530. [CrossRef]

- Sadowska J, Dudzińska W, Skotnicka E, Sielatycka K, Daniel I. The impact of a diet containing sucrose and systematically repeated starvation on the oxidative status of the uterus and ovary of rats. Nutrients. 2019; 11: 1544. [CrossRef]

- Gasparini PVF, Matias AM, Torezani-Sales S, Kobi JBBS, Siqueira JS, Corrêa CR, et al. High-Fat and Combined High-Fat and Sucrose Diets Promote Cardiac Oxidative Stress Independent of Nox2 Redox Regulation and Obesity in Rats. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2021; 55(5): 618-634. PMID: 34705355. [CrossRef]

- Jarukamjorn K, Jearapong N, Pimson C, Chatuphonprasert W. A High-Fat, High-Fructose Diet Induces Antioxidant Imbalance and Increases the Risk and Progression of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease in Mice. Scientifica. 2016; 2016: 5029414. [CrossRef]

- Busserolles J, Rock E, Gueux E, Mazur A, Grolier P, Rayssiguier Y. Short-term consumption of a high-sucrose diet has a pro-oxidant effect in rats. Br J Nutr. 2002; 87: 337-342. [CrossRef]

| CL (–) Sucrose | CL (+) Sucrose | DMG (–) Sucrose | DMG (+) Sucrose | ||

| Mean ± SD (n = 6) |

Mean ± SD (n = 6) |

Mean ± SD (n = 6) |

Mean ± SD (n = 6) |

P* Value | |

| Weight (g) | 31.52 ± 2.67 | 27.65 ± 0.60 | 22.60 ± 1.68 | 25.38 ± 2.19 | 0.001* |

| BMI (g/cm2) | 0.315 ± 0.03 | 0.263 ± 0.01 | 0.220 ± 0.02 | 0.233 ± 0.02 | 0.001* |

| Median | Median | Median | Median | ||

| Glycaemia (mg/dL) | 207 | 219 | 577 | 586 | 0.001* |

| CL (–) Sucrose | CL (+) Sucrose | DMG (–) Sucrose | DMG (+) Sucrose | ||

| Mean ± SD (n = 6) |

Mean ± SD (n = 6) |

Mean ± SD (n = 6) |

Mean ± SD (n = 6) |

P Value* | |

| *10th day, beginning of Supplementation | |||||

| Insulin (pg/mL) | 0.743 ± 0.012 | 0.743 ± 0.012 | 0.743 ± 0.008 | 0.743 ± 0.008 | 0.994 |

| HOMA-IR Index | 0.239 ± 0.257 | 0.2557 ± 0.257 | 0.209 ± 0.031 | 0.226 ± 0.029 | 0.062 |

| Adiponectin (pg/mL) | 8.5178 ± 1.031 | 8.76 ± 0.883 | 9.29 ± 2.4 | 10.53 ± 0.751 | 0.102 |

| Leptin (pg/mL) | 0.058 ± 0.031 | 0.074 ± 0.009 | 0.028 ± 0.012 | 0.038 ± 0.009 | 0.001* |

| &23rd day, end of gestation and Supplementation | |||||

| Insulin (pg/mL) | 0.438 ± 0.018 | 0.436 ± 0.014 | 0.443 ± 0.024 | 0.445 ± 0.005 | 0.792 |

| HOMA-IR Index | 0.394 ± 0.1564 | 0.397 ± 0.1050 | 1.026 ± 0.0718 | 1.027 ± 0.0886 | 0.001* |

| Adiponectin (pg/mL) | 9.574 ± 0.778 | 7.792 ± 2.154 | 6.622 ± 3.139 | 7.631 ± 2.162 | 0.175 |

| Leptin (pg/mL) | 0.077 ± 0.029 | 0.101 ± 0.051 | 0.027 ± 0.018 | 0.043 ± 0.018 | 0.003* |

| CL (-) Sucrose | CL (+) Sucrose | DMG (–) Sucrose | DMG (+) Sucrose | ||

| Mean ± SD (n = 6) |

Mean ± SD (n = 6) |

Mean ± SD (n = 6) |

Mean ± SD (n = 6) |

P Value* | |

| Cell Immunity | |||||

| CD3+ (%) | 26.41 ± 0.85 | 27.59 ± 0.71 | 26.05 ± 0.42 | 27.46 ± 0.95 | 0.004* |

| CD3+/CD4+ (%) | 44.45 ± 0.77 | 42.80 ± 0.43 | 44.15 ± 0.91 | 41.78 ± 0.41 | 0.001* |

| CD3+/CD8+ (%) | 26.37 ± 0.79 | 30.40 ± 0.85 | 27.05 ± 0.30 | 26.92 ± 0.78 | 0.001* |

| IL-1β (pg/mL) | 0.46 ± 0.20 | 8.28 ± 0.35 | 10.63 ± 0.56 | 12.50 ± 0.20 | 0.001* |

| IL-6 (pg/mL) | 1.08 ± 0.16 | 10.89 ± 0.80 | 7.39 ± 0.11 | 10.72 ± 0.19 | 0.001* |

| INF-γ (pg/mL) | 0.20 ± 0.09 | 5.04 ± 0.46 | 6.36 ± 0.24 | 10.76 ± 0.51 | 0.001* |

| TNF-α (pg/mL) | 0.33 ± 0.14 | 4.31 ± 0.08 | 5.49 ± 0.18 | 8.32 ± 0.31 | 0.001* |

| Humoral Immunity | |||||

| IgA (OD) | 0.298 ± 0.037 | 0.537 ± 0.078 | 1.061 ± 0.627 | 0.939 ± 0.176 | 0.002* |

| IgG (OD) | 0.247 ± 0.093 | 0.421 ± 0.080 | 0.545 ± 0.249 | 0.422 ± 0.083 | 0.017* |

| CL (-) Sucrose | CL (+) Sucrose | DMG (–) Sucrose | DMG (+) Sucrose | ||

| Median (n = 6) |

Median (n = 6) |

Median (n = 6) |

Median (n = 6) |

P* Value | |

| Antioxidants Parameters | |||||

| TAC (µM) | 0.133 | 0.167 | 0.159 | 0.179 | 0.025* |

| Catalase (U/L) | 0.182 | 0.168 | 0.193 | 0.172 | 0.138 |

| SOD (U/mL) | 1.274 | 0.925 | 1.823 | 2.047 | 0.019* |

| GR (µM) | 98.86 | 92.06 | 87.53 | 83 | 0.049* |

| Oxidants Parameters | |||||

| TBARS (µM) | 0.0218 | 0.0075 | 0.0625 | 0.1430 | 0.006* |

| AGE (pM/dL) | 1218 | 1791 | 725 | 3034 | 0.001* |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).