Submitted:

30 December 2024

Posted:

31 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

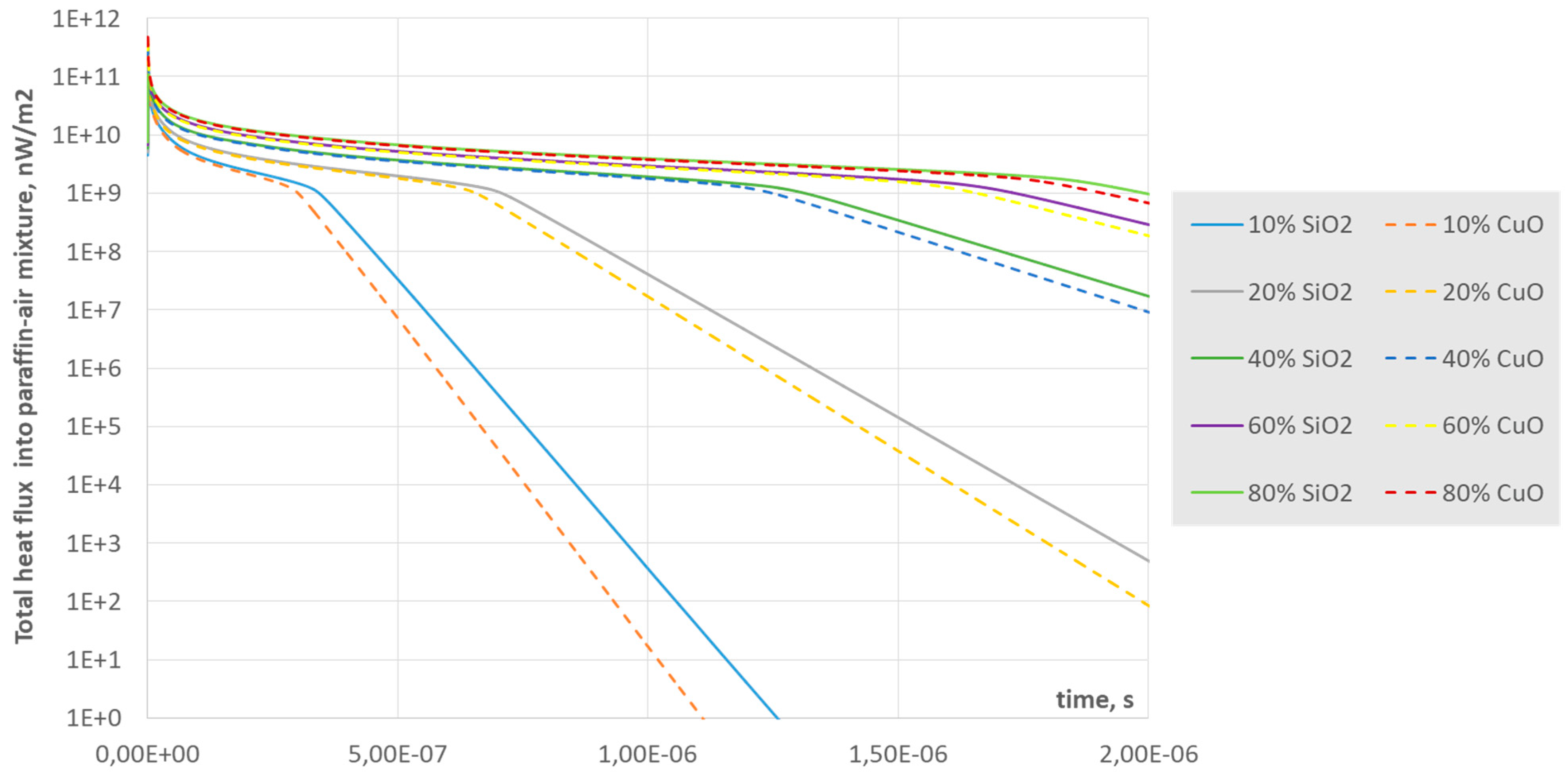

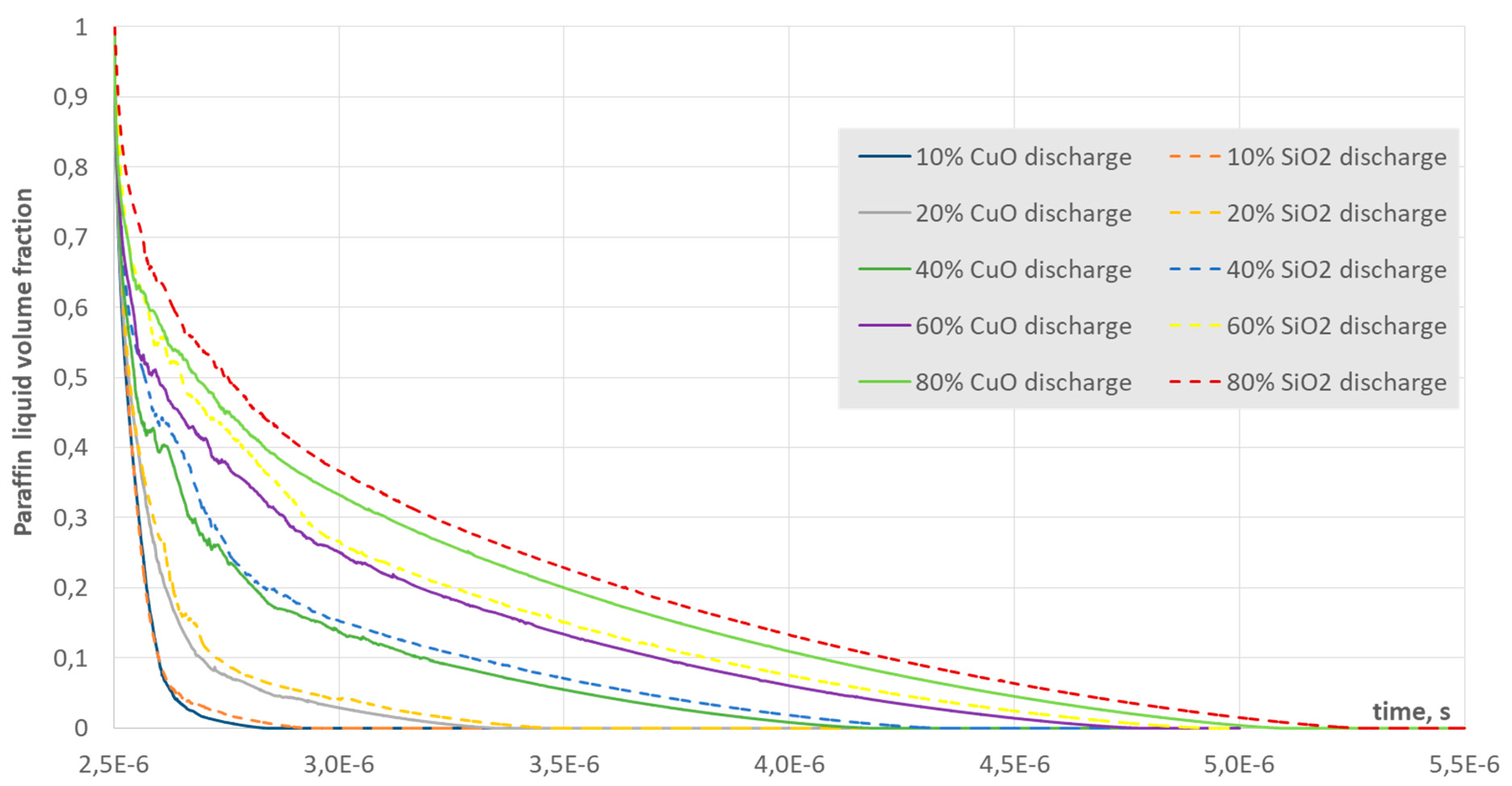

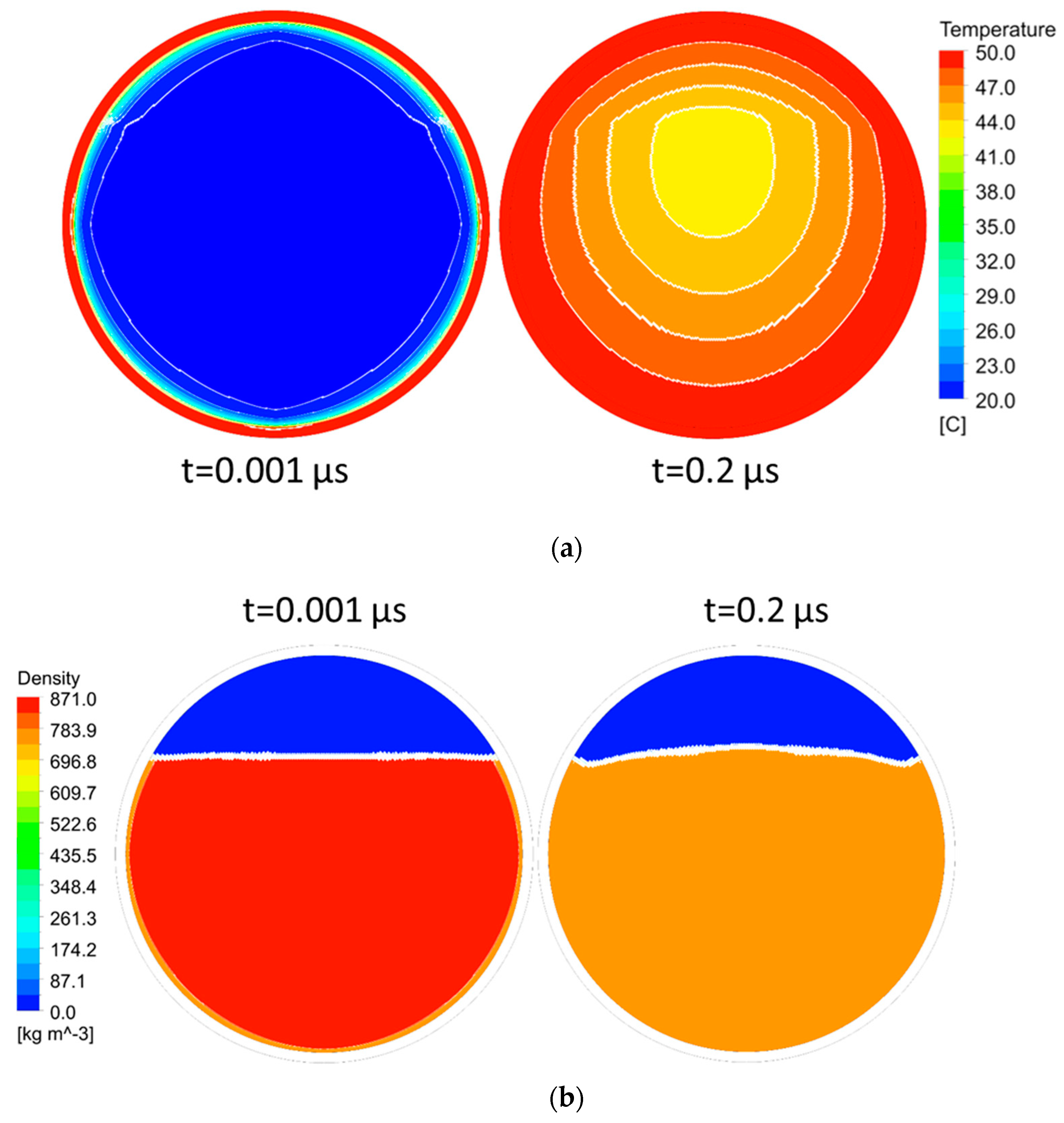

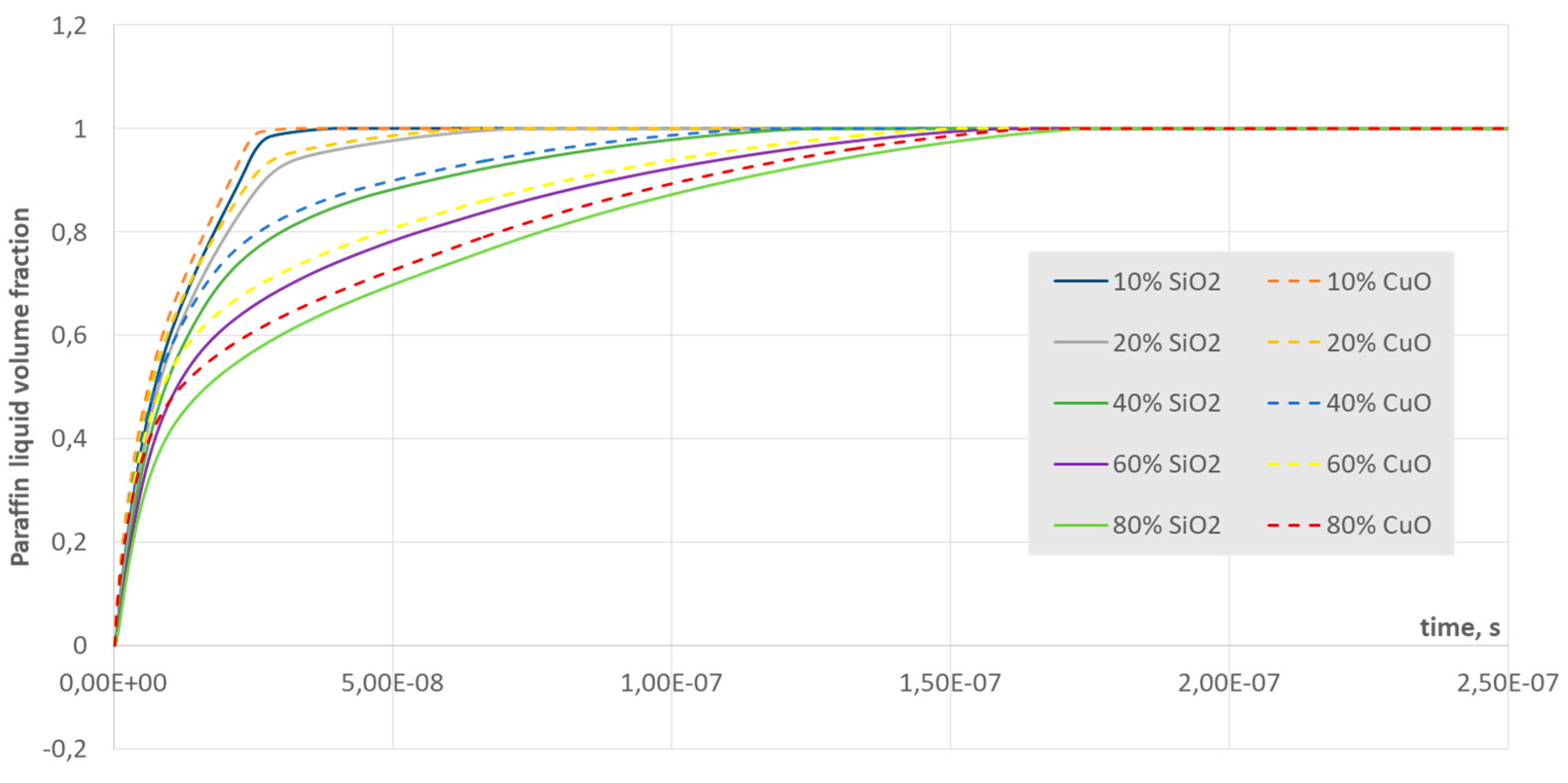

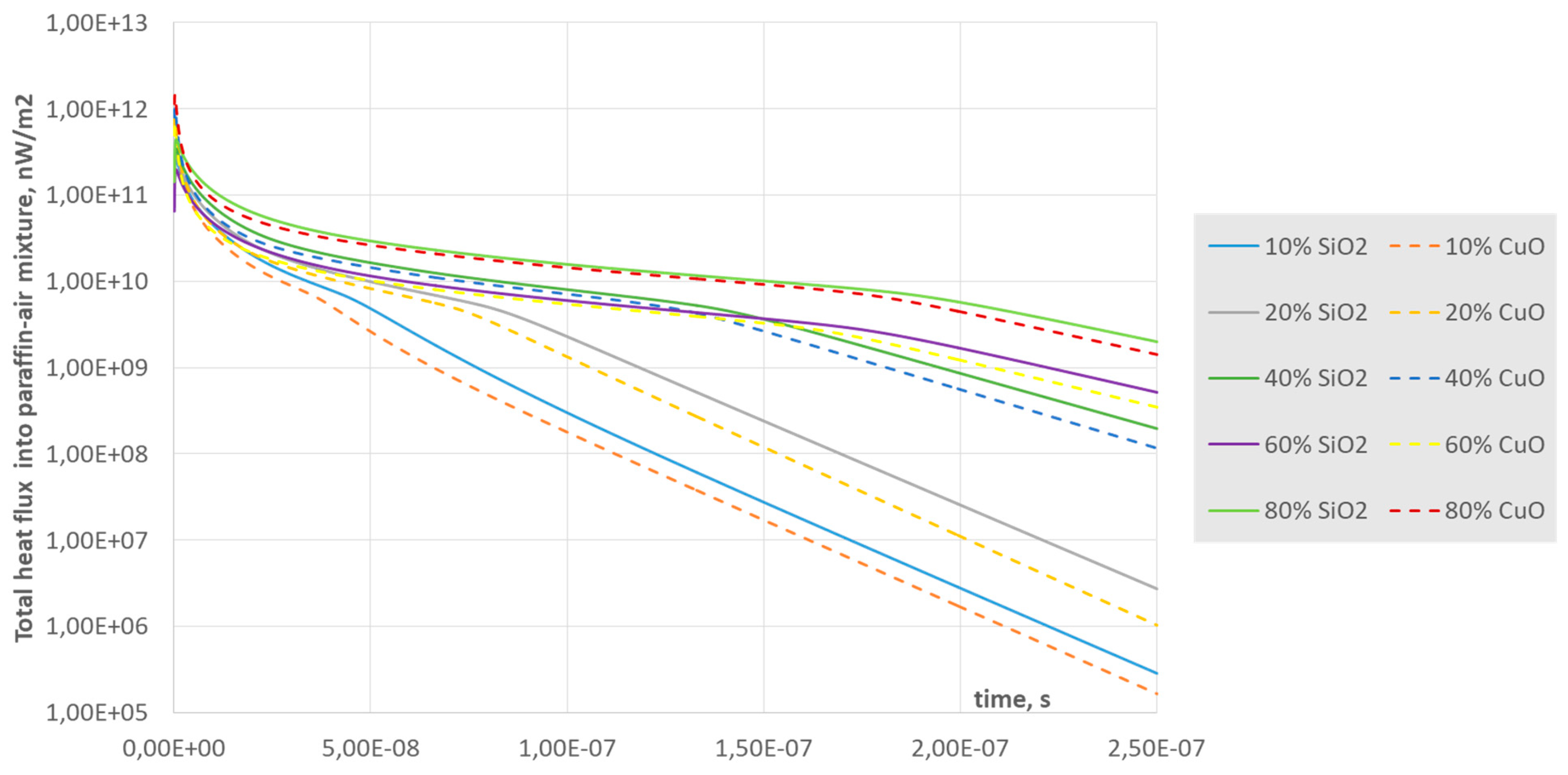

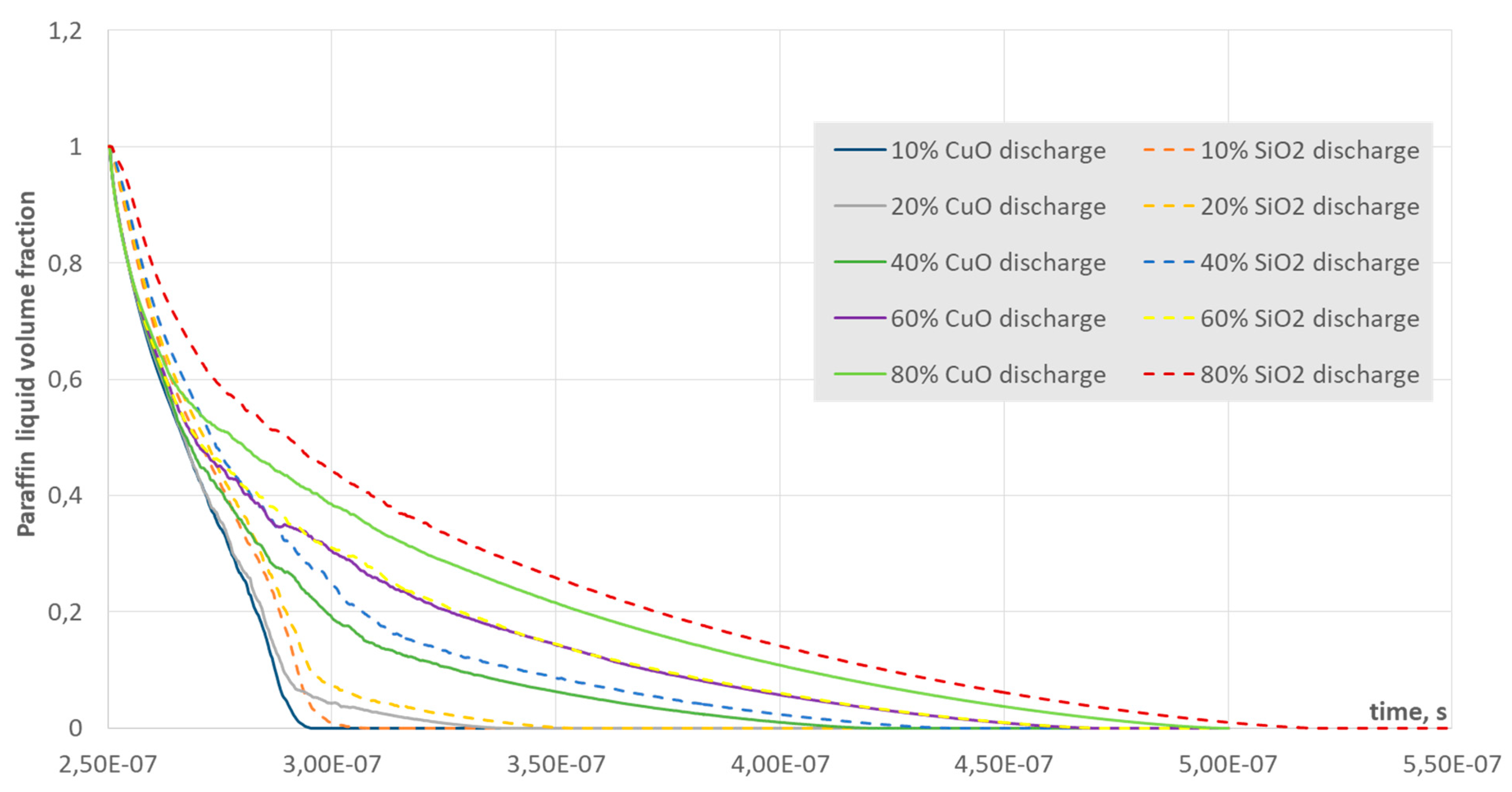

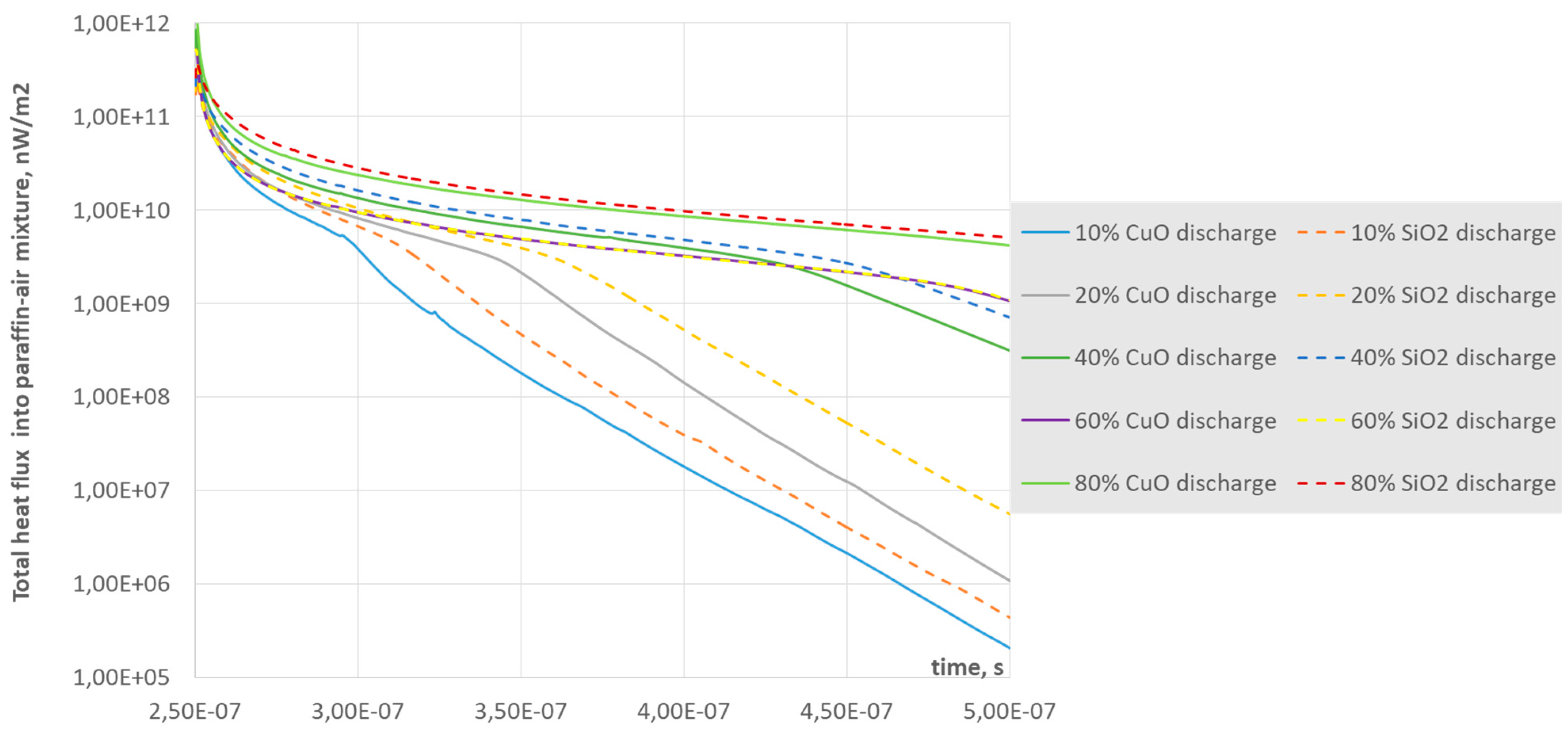

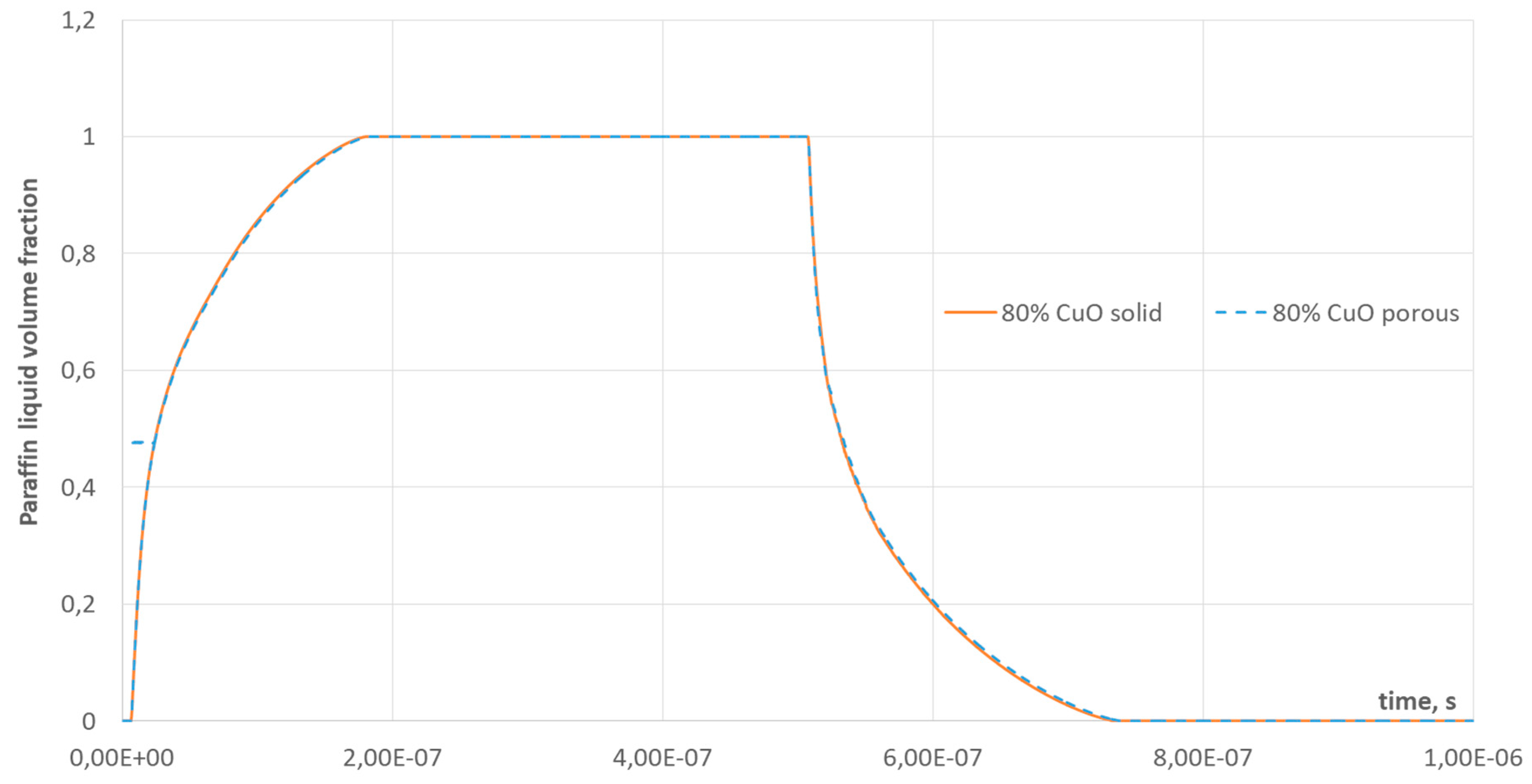

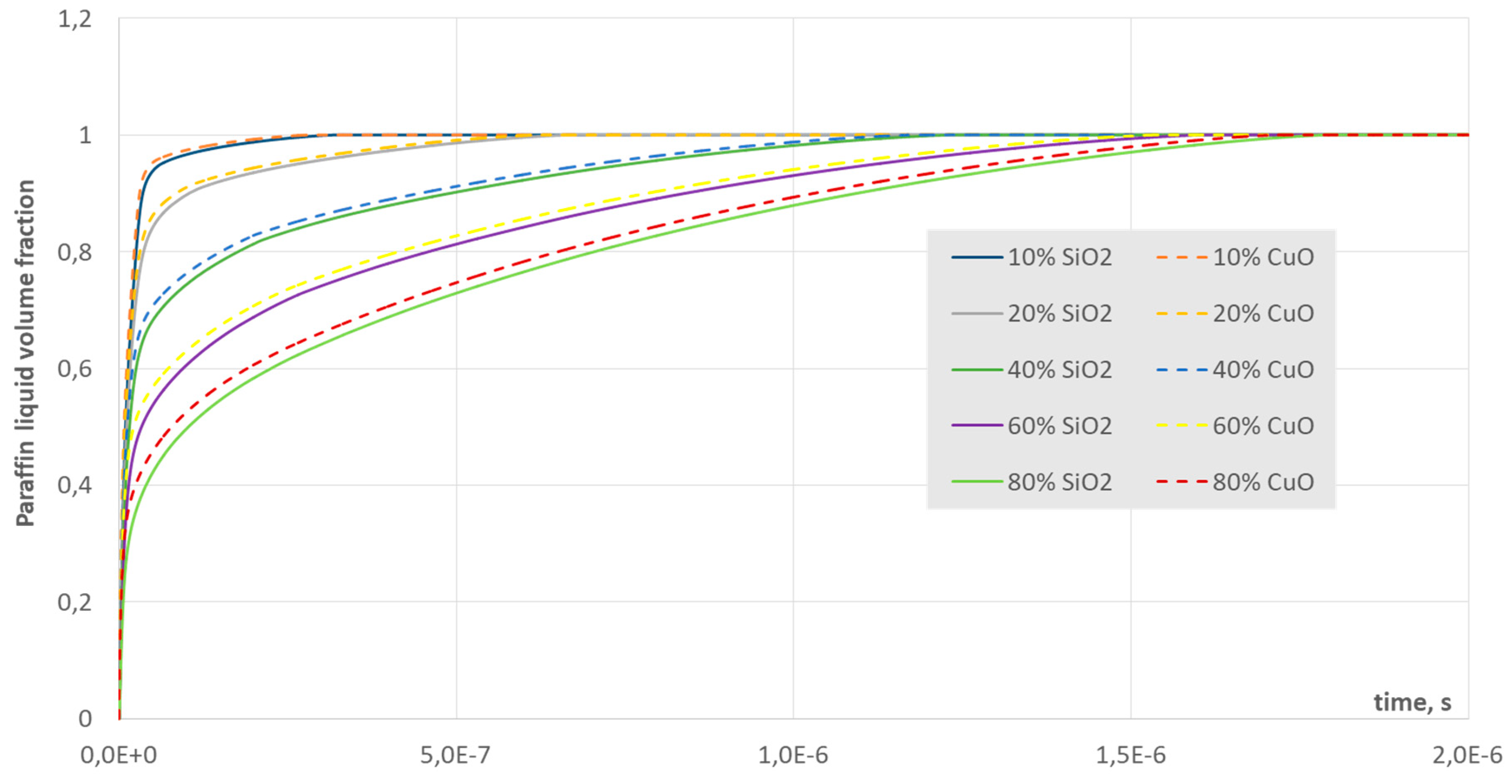

This study investigates the thermal performance of paraffin-based nanocontainers within porous wall environments, with a focus on optimizing energy storage and transfer efficiency in building applications. Phase change materials (PCMs) such as paraffin offer significant potential in thermal management due to their ability to store and release latent heat during phase transitions. In this study, paraffin nanocontainers with two specific dimensions, 200 nm and 700 nm, were simulated under varying volume fractions (0%, 10%, 20%, 40%, 60%, and 80%) to assess their melting and solidification characteristics. Two types of encapsulating shells, silicon dioxide (SiO₂) and copper oxide (CuO), were applied to analyze the effect of shell material on thermal behavior. The RANS approach in a laminar formulation and the volume of fluid (VOF) method were utilized to simulate interfacial behavior between the paraffin and air within the nanocontainers. Boundary conditions were set at an external temperature of 50°C and an initial temperature of 20°C, while the enthalpy-porosity model was used to simulate phase transitions. The type of shell material significantly influences the heat transfer rate and phase transition times. SiO₂ and CuO shells displayed differences in melting and solidification times, with CuO shells exhibiting faster phase change dynamics. For both dimensions of nanocontainers, the presence of porous walls facilitated a higher heat flux compared to solid walls, improving thermal efficiency. These findings underscore the potential of paraffin-based PCMs in energy-efficient building design, especially in applications requiring precise thermal control. This research contributes to advancing PCM integration in building materials.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials

2.1. Material Used

2.2. Theproblemstatement

2.3. The Boundary Conditions

3. Results

4. Conclusions

- The melting time of paraffin does not depend on the material of the wall (the thermal conductivity differs by an order of magnitude). After the paraffin has melted, some time passes before the entire volume of the now liquid paraffin is heated.

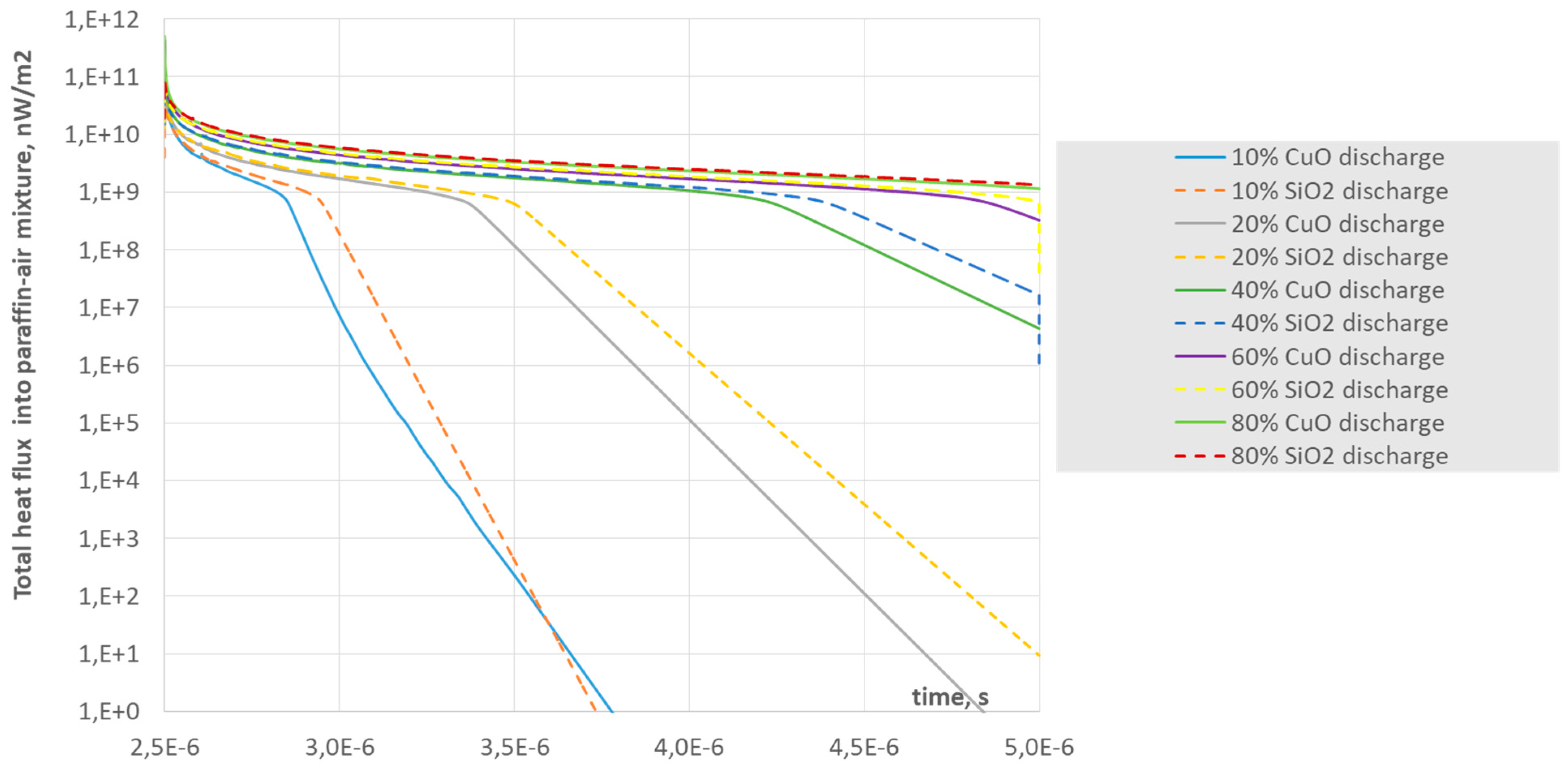

- CuO shells enhanced heat transfer rates compared to SiO₂, reducing both melting and solidification times. This suggests that CuO-based nanocontainers are more effective for rapid thermal response applications.

- Differences in container dimensions (200 nm vs. 700 nm) influenced the heat flux and liquid fraction changes during phase transitions. Smaller dimensions exhibited faster thermal responses, highlighting their suitability for applications where space and weight constraints exist.

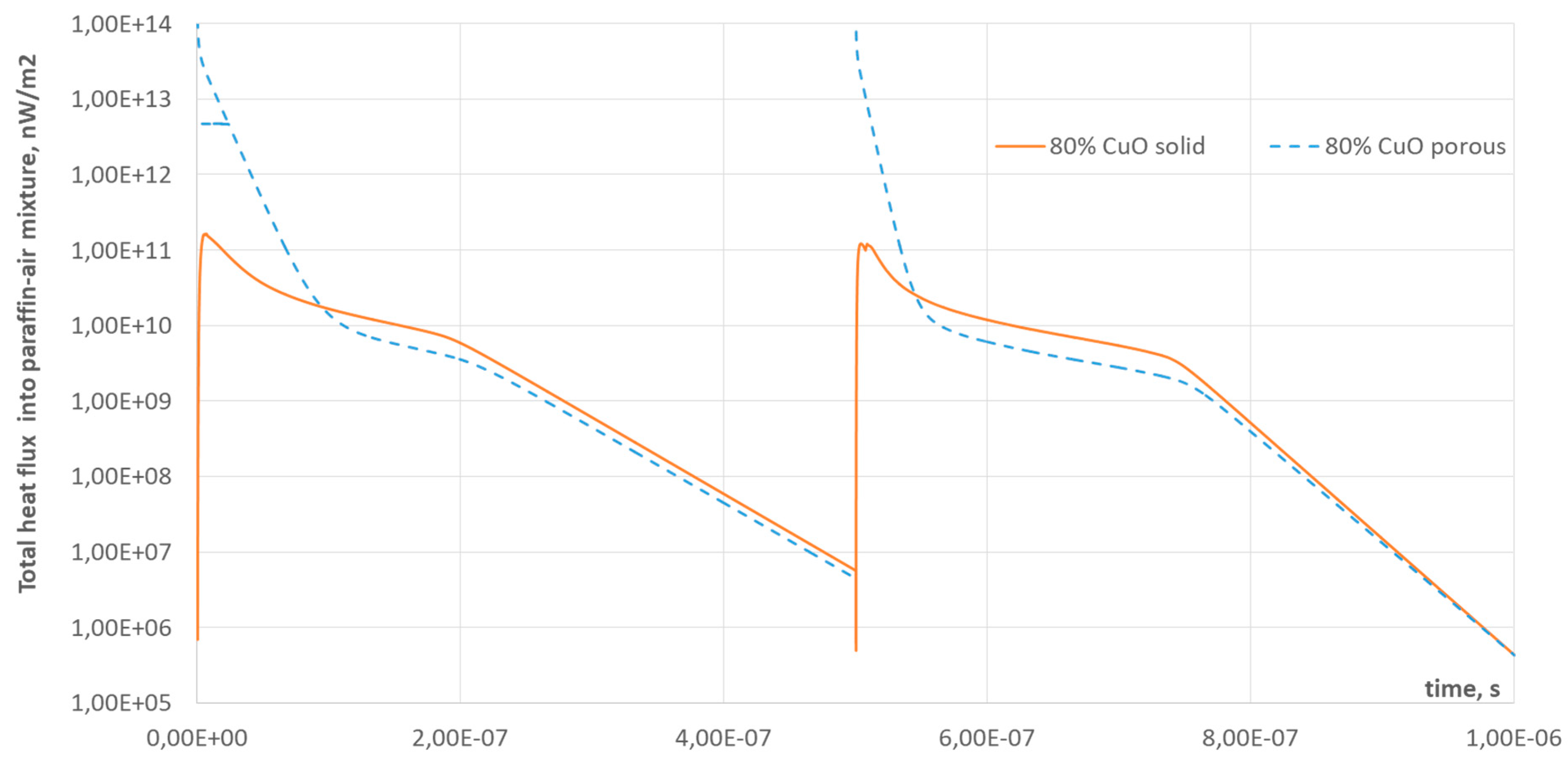

- Porous walls significantly improved the heat flux during both melting and solidification processes. This enhancement supports the use of porous PCM structures in building materials to maximize thermal regulation and efficiency.

- The addition of nanographite particles within the PCM led to a 21% reduction in melting time, offering a promising approach for accelerating thermal response in PCM-based systems.

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Goia, F., Perino, M., Serra, V. Experimental analysis of the energy performance of a full-scale PCM glazing prototype. Solar Energy. 2014. 100. Pp. 217–233. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.SOLENER.2013.12.002. [CrossRef]

- Li, S., Zou, K., Sun, G., Zhang, X. Simulation research on the dynamic thermal performance of a novel triple-glazed window filled with PCM. Sustainable Cities and Society. 2018. 40. Pp. 266–273. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.SCS.2018.01.020. [CrossRef]

- Alqaed, S. Effect of annual solar radiation on simple façade, double-skin facade and double-skin facade filled with phase change materials for saving energy. Sustainable Energy Technologies and Assessments. 2022. 51. Pp. 101928. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.SETA.2021.101928. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H., Fransson, Å., Olofsson, T. Influence of Phase Change Materials (PCMs) on the thermal performance of building envelopes. E3S Web of Conferences. 2020. 172. Pp. 21002. https://doi.org/10.1051/E3SCONF/202017221002. URL: https://www.e3s-conferences.org/articles/e3sconf/abs/2020/32/e3sconf_nsb2020_21002/e3sconf_nsb2020_21002.html (date of application: 28.04.2022). [CrossRef]

- de Gracia, A., Navarro, L., Castell, A., Ruiz-Pardo, Á., Alvárez, S., Cabeza, L.F. Experimental study of a ventilated facade with PCM during winter period. Energy and Buildings. 2013. 58. Pp. 324–332. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enbuild.2012.10.026. [CrossRef]

- Soares, N., Costa, J.J., Gaspar, A.R., Santos, P. Review of passive PCM latent heat thermal energy storage systems towards buildings’ energy efficiency. Energy and Buildings. 2013. 59. Pp. 82–103. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.ENBUILD.2012.12.042. URL:. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enbuild.2012.12.042 (date of application: 27.04.2022). [CrossRef]

- De Gracia, A., Navarro, L., Castell, A., Ruiz-Pardo, Á., Álvarez, S., Cabeza, L.F. Thermal analysis of a ventilated facade with PCM for cooling applications. Energy and Buildings. 2013. 65. Pp. 508–515. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.ENBUILD.2013.06.032. [CrossRef]

- Duan, S., Feng, J., Yu, W., Huang, J., Wu, X., Zeng, K., Lei, Z., Qiu, L., Wang, L., Luo, R. The influences of ball milling processing on the morphology and thermal properties of natural graphite-based porous graphite and their phase change composites. Journal of Energy Storage. 2022. 55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.est.2022.105800. [CrossRef]

- Torres-Rodríguez, A., Morillón-Gálvez, D., Aldama-Ávalos, D., Hernández-Gómez, V.H., García Kerdan, I. Thermal performance evaluation of a passive building wall with CO2-filled transparent thermal insulation and paraffin-based PCM. Solar Energy. 2020. 205. Pp. 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.SOLENER.2020.04.090. [CrossRef]

- Tetuko, A.P., Sebayang, A.M.S., Fachredzy, A., Setiadi, E.A., Asri, N.S., Sari, A.Y., Purnomo, F., Muslih, C., Fajrin, M.A., Sebayang, P. Encapsulation of paraffin-magnetite, paraffin, and polyethylene glycol in concretes as thermal energy storage. Journal of Energy Storage. 2023. 68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.est.2023.107684. [CrossRef]

- Wu, S., Wang, H., Xiao, S., Zhu, D. Numerical simulation on thermal energy storage behavior of Cu/paraffin nanofluids PCMs. Procedia Engineering. 2012. 31. Pp. 240–244. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.proeng.2012.01.1018. [CrossRef]

- Chen, C., Zhang, H., Gao, X., Xu, T., Fang, Y., Zhang, Z. Numerical and experimental investigation on latent thermal energy storage system with spiral coil tube and paraffin/expanded graphite composite PCM. Energy Conversion and Management. 2016. 126. Pp. 889–897. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enconman.2016.08.068. [CrossRef]

- Kazaz, O., Karimi, N., Kumar, S., Falcone, G., Paul, M.C. Heat transfer characteristics of fluids containing paraffin core-metallic shell nanoencapsulated phase change materials for advanced thermal energy conversion and storage applications. Journal of Molecular Liquids. 2023. 385. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molliq.2023.122385. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y., Feng, D., Zhang, X., Feng, Y. Directional enhancement and potential reduction of thermal conductivity induced by one-dimensional nanoparticle addition in pure PCMs. International Journal of Heat and Mass Transfer. 2023. 215. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijheatmasstransfer.2023.124478. [CrossRef]

- Martínez, A., Carmona, M., Cortés, C., Arauzo, I. Experimentally based testing of the enthalpy-porosity method for the numerical simulation of phase change of paraffin-type PCMs. Journal of Energy Storage. 2023. 69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.est.2023.107876. [CrossRef]

- Costa, J.A.C., Martinelli, A.E., do Nascimento, R.M., Mendes, A.M. Microstructural design and thermal characterization of composite diatomite-vermiculite paraffin-based form-stable PCM for cementitious mortars. Construction and Building Materials. 2020. 232. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2019.117167. [CrossRef]

- Baccega, E., Bottarelli, M., Cesari, S. Addition of granular phase change materials (PCMs) and graphene to a cement-based mortar to improve its thermal performances. Applied Thermal Engineering. 2023. 229. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2023.120582. [CrossRef]

- Pagkalos, C., Dogkas, G., Koukou, M.K., Konstantaras, J., Lymperis, K., Vrachopoulos, M.G. Evaluation of water and paraffin PCM as storage media for use in thermal energy storage applications: A numerical approach. International Journal of Thermofluids. 2020. 1–2. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijft.2019.100006. [CrossRef]

- Torres-Rodríguez, A., Morillón-Gálvez, D., Aldama-Ávalos, D., Hernández-Gómez, V.H., García Kerdan, I. Thermal performance evaluation of a passive building wall with CO2-filled transparent thermal insulation and paraffin-based PCM. Solar Energy. 2020. 205. Pp. 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.solener.2020.04.090. [CrossRef]

- Soares, N., Matias, T., Durães, L., Simões, P.N., Costa, J.J. Thermophysical characterization of paraffin-based PCMs for low temperature thermal energy storage applications for buildings. Energy. 2023. 269. Pp. 126745. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.ENERGY.2023.126745. [CrossRef]

- Javidan, M., Asgari, M., Gholinia, M., Nozari, M., Asgari, A., Ganji, D.D. Investigation of convection and radiation heat transfer of paraffinic materials and storage of thermal energy in melting process of PCMs in the cavity with transparent inner walls. Energy Reports. 2022. 8. Pp. 5522–5532. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.EGYR.2022.04.025. [CrossRef]

- Faraj, K., Khaled, M., Faraj, J., Hachem, F., Castelain, C. A review on phase change materials for thermal energy storage in buildings: Heating and hybrid applications. Journal of Energy Storage. 2021. 33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.est.2020.101913. [CrossRef]

- Bouhal, T., Meghari, Z., Fertahi, S. ed D., El Rhafiki, T., Kousksou, T., Jamil, A., Ben Ghoulam, E. Parametric CFD analysis and impact of PCM intrinsic parameters on melting process inside enclosure integrating fins: Solar building applications. Journal of Building Engineering. 2018. 20. Pp. 634–646. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JOBE.2018.09.016. [CrossRef]

- Hamidi, Y., Aketouane, Z., Malha, M., Bruneau, D., Bah, A., Goiffon, R. Integrating PCM into hollow brick walls: Toward energy conservation in Mediterranean regions. Energy and Buildings. 2021. 248. Pp. 111214. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.ENBUILD.2021.111214. [CrossRef]

- Wijesuriya, S., Tabares-Velasco, P.C. Experimental apparatus and methodology to test and quantify thermal performance of micro and macro-encapsulated phase change materials in building envelope applications. Journal of Energy Storage. 2020. 32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.est.2020.101770. [CrossRef]

- Zeinelabdein, R., Omer, S., Mohamed, E. Parametric study of a sustainable cooling system integrating phase change material energy storage for buildings. Journal of Energy Storage. 2020. 32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.est.2020.101972. [CrossRef]

- Gholamibozanjani, G., Farid, M. A comparison between passive and active PCM systems applied to buildings. Renewable Energy. 2020. 162. Pp. 112–123. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.renene.2020.08.007. [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y., He, F., Meng, X., Wang, Z., Zhang, M., Yu, H., Gao, W. Thermal behavior analysis of hollow bricks filled with phase-change material (PCM). Journal of Building Engineering. 2020. 31. Pp. 101447. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JOBE.2020.101447. [CrossRef]

- Konuklu, Y., Ostry, M., Paksoy, H.O., Charvat, P. Review on using microencapsulated phase change materials (PCM) in building applications. Energy and Buildings. 2015. 106. Pp. 134–155. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enbuild.2015.07.019. [CrossRef]

- Marani, A., Nehdi, M.L. Integrating phase change materials in construction materials: Critical review. Construction and Building Materials. 2019. 217. Pp. 36–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2019.05.064. [CrossRef]

- Li, D., Wu, Y., Wang, B., Liu, C., Arıcı, M. Optical and thermal performance of glazing units containing PCM in buildings: A review. Construction and Building Materials. 2020. 233. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2019.117327. [CrossRef]

- Lamrani, B., Johannes, K., Kuznik, F. Phase change materials integrated into building walls: An updated review. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews. 2021. 140. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2021.110751. [CrossRef]

- da Cunha, S.R.L., de Aguiar, J.L.B. Phase change materials and energy efficiency of buildings: A review of knowledge. Journal of Energy Storage. 2020. 27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.est.2019.101083. [CrossRef]

- Sun, X., Liu, L., Mo, Y., Li, J., Li, C. Enhanced thermal energy storage of a paraffin-based phase change material (PCM) using nano carbons. Applied Thermal Engineering. 2020. 181. Pp. 115992. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.APPLTHERMALENG.2020.115992. [CrossRef]

- Wijesuriya, S., Tabares-Velasco, P.C., Biswas, K., Heim, D. Empirical validation and comparison of PCM modeling algorithms commonly used in building energy and hygrothermal software. Building and Environment. 2020. 173. Pp. 106750. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.BUILDENV.2020.106750. [CrossRef]

- Mahdi, J.M., Lohrasbi, S., Ganji, D.D., Nsofor, E.C. Simultaneous energy storage and recovery in the triplex-tube heat exchanger with PCM, copper fins and Al2O3 nanoparticles. Energy Conversion and Management. 2019. 180. Pp. 949–961. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.ENCONMAN.2018.11.038. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X., Li, W., Huang, Y., Zhang, S., Wang, K. Study on shape-stabilised paraffin-ceramsite composites with stable strength as phase change material (PCM) for energy storage. Construction and Building Materials. 2023. 388. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2023.131678. [CrossRef]

- Goia, F., Boccaleri, E. Physical–chemical properties evolution and thermal properties reliability of a paraffin wax under solar radiation exposure in a real-scale PCM window system. Energy and Buildings. 2016. 119. Pp. 41–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.ENBUILD.2016.03.007. [CrossRef]

| Paraffin Volume Fraction | t, μs, SiO2 | t, μs, CuO | p, nW, SiO2 | p, nW, CuO | diff for t(%) | diff for p(%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10% | 0.0397 | 0.0322 | 2.021 | 2.088 | 20.86% | 3.28% |

| 20% | 0.0733 | 0.066 | 2.860 | 2.943 | 10.48% | 2.83% |

| 40% | 0.1265 | 0.1184 | 4.431 | 4.529 | 6.61% | 2.19% |

| 60% | 0.1613 | 0.1521 | 3.098 | 3.153 | 5.87% | 1.76% |

| 80% | 0.1759 | 0.1666 | 7.697 | 7.821 | 5.43% | 1.59% |

| Paraffin Volume Fraction | t, μs, SiO2 | t, μs, CuO | p, nW, SiO2 | p, nW, CuO | diff for t(%) | diff for p(%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10% | 0.058 | 0.046 | 2.082 | 2.124 | 22.73% | 1.97% |

| 20% | 0.104 | 0.088 | 2.902 | 2.892 | 16.22% | 0.36% |

| 40% | 0.189 | 0.171 | 4.461 | 4.559 | 10.13% | 2.18% |

| 60% | 0.222 | 0.221 | 3.158 | 3.207 | 0.50% | 1.55% |

| 80% | 0.270 | 0.249 | 7.726 | 7.891 | 8.10% | 2.11% |

| Solid | Porous | diff, % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| t charge, μs | 0.180 | 0.182 | 1.10% |

| power charge, nW | 7.84 | 671.31 | 195.38% |

| t discharge, μs | 0.235 | 0.240 | 1.81% |

| power discharge, nW | 11.95 | 646.42 | 192.74% |

| Paraffin Volume Fraction | t, μs, SiO2 | t, μs, CuO | p, nW, SiO2 | p, nW, CuO | diff for t(%) | diff for p(%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10% | 0.321 | 0.282 | 26.793 | 27.107 | 13.04% | 1.16% |

| 20% | 0.669 | 0.622 | 49.927 | 50.319 | 7.39% | 0.78% |

| 40% | 1.234 | 1.173 | 96.379 | 96.801 | 5.03% | 0.44% |

| 60% | 1.606 | 1.538 | 143.462 | 143.952 | 4.38% | 0.34% |

| 80% | 1.792 | 1.719 | 189.450 | 190.165 | 4.19% | 0.38% |

| Paraffin Volume Fraction | t, μs, SiO2 | t, μs, CuO | p, nW, SiO2 | p, nW, CuO | diff for t(%) | diff for p(%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10% | 0.341 | 0.433 | 27.286 | 26.827 | 23.79% | 1.69% |

| 20% | 0.850 | 0.974 | 50.792 | 50.702 | 13.57% | 0.18% |

| 40% | 1.685 | 1.837 | 98.478 | 96.445 | 8.60% | 2.09% |

| 60% | 2.281 | 2.431 | 141.335 | 139.004 | 6.35% | 1.66% |

| 80% | 2.595 | 2.770 | 178.764 | 175.190 | 6.53% | 2.02% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).