Introduction

Fluorine is a highly reactive and electronegative element, which predominantly exists in nature as a bound form known as fluoride (Shanmugam & Selvaraj, 2022). Often referred to as a "double-edged sword," fluoride is found in varying concentrations in soil, water, and air. While small amounts can be beneficial, excessive intake over extended periods can lead to detrimental effects. Prolonged exposure to elevated levels of fluoride ultimately results in fluorosis, a serious condition that affects both humans and animals (Zou et al., 2012). Animals exposed to fluoride through contaminated vegetation, water, or inhaled fluoridated air over time can become toxic, leading to a gradual decline in their health. This extended exposure, regardless of the source, can result in fluorosis, impacting both humans and domestic and wild animals (Mohammadi et al., 2017). Mammals are generally more prone to fluorosis compared to birds, amphibians, reptiles, and fish. The primary indicators of high fluoride exposure in mammals include dental fluorosis, which harms their teeth, skeleton, and bones (Keirdorf et al., 2016). Livestock suffering from fluorosis may experience difficulties with foraging and movement, ultimately undermining their growth, reproduction, and overall performance (Ranjan et al., 2016).

Fluoride tolerance differs among animal species due to various factors, including age, species, body mass, dietary concentration levels, and frequency of exposure. Consequently, defining tolerance thresholds in livestock presents considerable challenges. A prior investigation has established that safe fluoride concentrations in the drinking water of cattle, sheep, goats, horses, and camels can reach up to 1 ppm (parts per million) (Choubisa, 2012). Although acute fluoride poisoning in wildlife is atypical, chronic fluoride toxicity has been documented in several terrestrial herbivorous mammals, resulting in osteo-dental fluorosis. Affected species include cervids such as red deer (Cervus elaphus L.), white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus), roe deer (Capreolus capreolus), mule deer (Odocoileus hemionus), elk (Cervus canadensis), and moose (Alces alces). Additionally, bovids including bison (Bison bison and B. bonasus), wild boar (Sus scrofa), fruit bats such as Pteropus giganteus, P. poliocephalus, and Rousettus aegyptiacus, as well as rodents including voles (Microtus agrestis and Clethrionomys glareolus), wood mice (Apodemus sylvaticus), and cotton rats (Sigmodon hispidus), have exhibited signs of chronic toxicity (Death et al., 2018). Furthermore, osteofluorosis associated with Metabolic Bone Disease has been reported in native frogs belonging to the genus Leiopelma in New Zealand. These findings highlight the vulnerability of wildlife to the adverse effects of prolonged fluoride exposure, which can lead to persistent lameness in affected individuals (Shaw et al., 2012). The primary aim of this study is to analyze the prevalence of skeletal and dental fluorosis in commonly present wild fauna while proposing potential mitigation measures to safeguard wildlife against fluoride pollution.

Fluorosis in Wildlife

Fluorosis has been recorded in various regions worldwide, including India (

Table 1). This condition poses a significant threat to both wildlife and the broader ecosystem. The effects of fluoride pollution differ across states, with notable impacts on wildlife populations within India. For example, the Gir Forest in Gujarat, which serves as a habitat for the Asiatic lion (Panthera leo persica), has reported substantial cases of fluorosis. The presence of elevated fluoride levels in water sources has resulted in dental and skeletal deformities in these lions, as well as in other herbivorous species such as spotted deer (Axis axis) and nilgai (Boselaphus tragocamelus) (The Times of India, 2014). In addition, the Indian state of Rajasthan, characterized by arid conditions and groundwater contaminated with fluoride, has documented instances of fluorosis in species including the blackbuck (Antilope cervicapra), chinkara (Gazella bennettii), and blue bull (Boselaphus tragocamelus). These animals exhibit severe dental and skeletal fluorosis as a consequence of prolonged exposure to fluoride from contaminated water and forage (Gahlot and Zakher, 2015).

Fluoride Exposure Sources for the Wild

Fluoride is ubiquitously present in various environmental media, including seawater, freshwater, groundwater, soil, dust, and mineral deposits. The emissions of fluoride from industrial activities accumulate in soil and vegetation and can subsequently contaminate freshwater sources. Prolonged consumption of herbicides and agricultural feeds contaminated with fluoride poses a significant risk of developing industrial fluorosis in animals. Moreover, the accumulation of volcanic ash can contribute to the pollution of both water and vegetation. It is important to note that the primary sources of fluoride exposure for wildlife consist of contaminated water and vegetation, which can be influenced by both natural phenomena and anthropogenic activities (Choubisa & Choubisa, 2015). Wildlife encounters fluoride exposure through several key avenues: fluoridated drinking water; vegetation and agricultural crops cultivated in fluoride-contaminated soil and water; fluoridated phosphate feed supplements; mineral additives; airborne dust resulting from industrial processes such as coal-fired power generation; and the manufacturing of materials, including steel, iron, aluminum, zinc, phosphorus, chemical fertilizers, bricks, glass, and plastics. These industrial processes release fluoride into the environment in both gaseous and particulate forms, thereby presenting potential health risks to wildlife and their habitats. Fluoride is largely eliminated from the body via sweat, urine, and feces. A notable quantity of fluoride accumulates in the eggs produced by wildlife and in the milk they generate, while some fluoride is retained in the body and stored in vital organs (Choubisa, 2024).

Fluorosis in Wild Animals

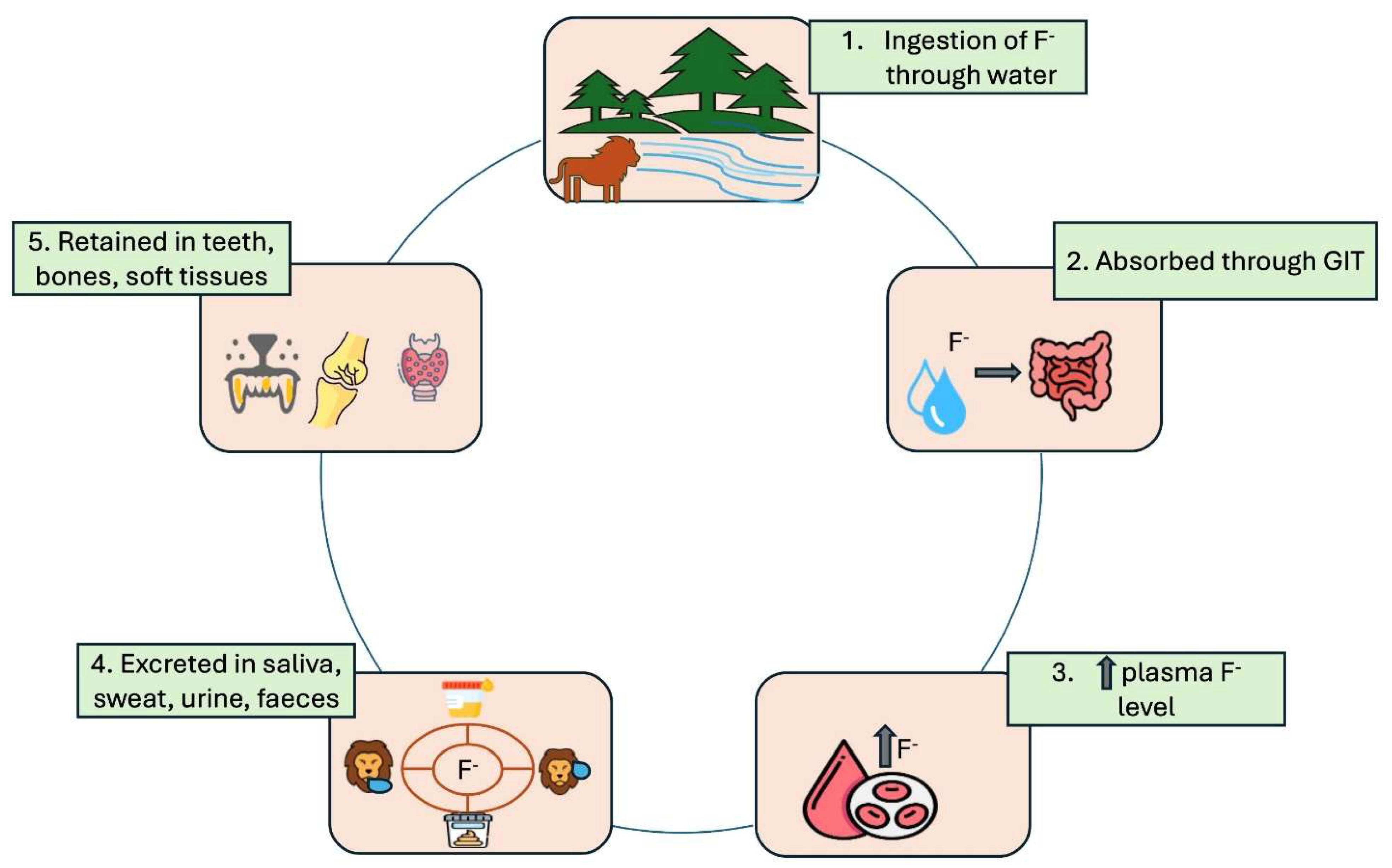

When fluoride is present in the environment at sufficiently high concentrations, animals ingest it through their food and water while grazing and drinking (Weinstein and Davison, 2003). Fluoride particularly targets mineralized tissues, with approximately 99% of retained fluoride residing in the hard tissues of bones and teeth. It is primarily integrated into actively mineralizing tissues such as bones and teeth, existing in the form of calcium hydroxyapatite crystals. Prolonged exposure to elevated levels of fluoride can result in chronic fluoride toxicity, which may lead to health issues in domestic animals (Flueck and Smith-Flueck, 2013); it is also anticipated that wild animals could experience similar effects. Only 10% of fluoride is absorbed by soft tissues from plasma, while the majority is accumulated by skeletal tissues. The kidneys serve as the primary excretory pathway for fluoride, with up to 70% of ingested fluoride being eliminated through urine, sweat, saliva, eggs, milk, and feces (Ranjan and Ranjan, 2015b) (

Figure 1). The remaining fluoride is absorbed and retained in the body, with 90% incorporated into skeletal tissues (Whitford, 1996).

Numerous studies have demonstrated that excessive fluoride exposure can significantly impact livestock productivity (Roy et al., 2018). The detrimental effects include incomplete enamel formation, mottled teeth, excessive dental wear (Kanduti et al., 2016), and skeletal deformities. Furthermore, research indicates that animals subjected to high levels of fluoride suffer from impaired oocyte maturation, resulting in reduced reproductive capabilities. These findings underscore the serious consequences of fluoride contamination for the health and productivity of livestock.

Calcium and phosphorus are vital components found in both the soft tissues (plasma) and hard tissues (bones and teeth) of animals. In bones and teeth, these minerals combine to form calcium hydroxyapatite crystals, represented by the formula Ca3(PO4)2·2Ca(OH)2. An excessive intake of fluoride (F-) from feed or water can displace hydroxide ions (OH-) due to their similar ionic sizes. This displacement leads to the formation of Ca3(PO4)2·Ca(F)2, resulting in a change in the color of calcium hydroxyapatite from white (OH-) to a brownish shade (F-). Livestock tissues with elevated calcium content, such as bones and teeth, are more prone to attract and accumulate fluoride. This accumulation can hinder the mineralization process of bones and teeth, posing particular risks to young and growing animals. Furthermore, fluoride can penetrate body tissues, potentially causing irreversible damage to vital organs, including the liver, kidneys, and brain, over time. These effects highlight the considerable health risks associated with fluoride overexposure in livestock (Pradhan et al., 2016).

Skeletal lesions resulting from fluoride toxicity in animals can manifest as varying degrees of periosteal hyperostosis, which may be localized or widespread, as well as Degenerative Joint Disease (DJD or arthritis), leading to significant pain and lameness. These changes ultimately compromise overall health, fitness, body condition, and reproductive success or performance. Notably, in ungulates, initial lesions typically appear in the metatarsus or metacarpus bones of the limbs. In macropods (marsupials), lesions are predominantly found in the hind limbs, while forelimb, spine, and rib lesions occur primarily in individuals with the highest concentrations of fluoride in their bones. In koalas, periosteal hyperostosis is usually observed in the mandibles, with DJD affecting their elbow joints. Similar joint issues have been documented in possums and other wildlife impacted by fluoride toxicity. The excessive accumulation of fluoride in muscles not only restricts bone movement, resulting in lameness but also leads to intermittent lameness, joint swelling, muscle wasting, and increased mortality among affected animals. These symptoms highlight the profound impact of fluoride toxicity on animal health and mobility.

The severity of bone deformities, including periosteal hyperostosis and osteophytosis, is directly correlated with elevated fluoride levels in bone tissue. In wildlife affected by fluoride exposure, bone fluoride concentrations frequently exceed typical values, often surpassing 1000 μg F/g. Research has identified a critical threshold of approximately 4000 μg F/g of dry bone; beyond this limit, significant lesions appear across various mammalian species. Notably, investigations indicate that animals exhibiting fluoride bone levels up to 2500 ppm do not present any macroscopic or microscopic alterations (Death et al., 2015). This observation emphasizes the critical thresholds at which fluoride-induced skeletal damage becomes evident in wildlife.

The detrimental effects of fluoride on various organ systems are collectively referred to as non-skeletal fluorosis. Symptoms associated with non-skeletal fluorosis may emerge in animals prior to the onset of visible dental deformities. Extended ingestion of high fluoride concentrations can result in fluorosis, impacting multiple organ systems and leading to a range of medical abnormalities. Fluoride compounds are characterized by high solubility and are rapidly absorbed within the digestive systems of animals. Due to the electronegative properties of fluoride, it binds strongly to calcium ions present in the gastrointestinal tract, thereby inhibiting their absorption and causing a marked decrease in serum calcium levels (Maiti et al., 2004). Consequently, affected calves may exhibit symptoms such as discomfort, diminished appetite, constipation, watery diarrhea, excessive gas, and abdominal distress. Chronic fluorosis can result in significant structural changes in the kidneys, including glomerular shrinkage and widening of Bowman's spaces, accompanied by inflammatory cell infiltration (Talpur et al., 2022).

Furthermore, fluorosis disrupts the normal functioning of the thyroid, parathyroid, and adrenal glands, leading to alterations in hormonal balances. There exist notable gaps in the current research concerning the impacts of fluoride on reproductive organs, gametogenesis, embryogenesis, and brain function, which could result in potential endocrine disruptions and modifications in bodily fluids (Swarup and Dwivedi, 2002).

Testing Fluoride Contamination in Wildlife

Screening wild animals for fluorosis presents notable challenges due to the difficulties associated with tracking and observing them in their natural habitats, particularly in dense jungles and remote ecosystems. Animals residing in areas with elevated natural fluoride levels—such as regions characterized by volcanic activity or specific rock formations like granite and basalt—are at risk of fluoride exposure through contaminated water, soil, and vegetation. In these environments, herbivores may ingest fluoride from plants or water, while carnivores can accumulate fluoride by consuming herbivores (Choubisa, 2013). Effective screening methods include sampling water, analyzing soil and vegetation, monitoring air quality, and collecting non-invasive samples such as feces or urine. For animals that are captured, blood and bone analysis using techniques like X-rays can verify fluoride accumulation. Additionally, long-term health monitoring programs focused on reproductive success, survival rates, and overall population health are crucial for understanding the broader ecological impact (Vikøren, 2021).

Fluoride exposure can result in stunted growth, reduced fertility, and increased disease susceptibility, particularly among species with small populations or those reliant on specific resources. Although fluorosis in wild animals is less studied than in domesticated species, understanding its effects on wildlife is essential for conservation efforts and ecosystem wellbeing—especially in regions where fluoride contamination, whether from natural or anthropogenic sources, is prevalent. Integrating wildlife health research, environmental monitoring, and conservation strategies will be critical for mitigating the risks posed by fluoride and safeguarding biodiversity in vulnerable ecosystems (Choubisa, 2023).

Mitigation Strategies

Chronic fluoride intoxication, commonly referred to as fluorosis, presents significant challenges once symptoms manifest in wildlife, as treatment options are generally ineffective. One of the most detrimental consequences of chronic fluoride toxicity is the decline in reproductive success, which carries profound implications for wildlife populations. Consequently, there exists a pressing need for proactive measures aimed at preventing and managing fluoride intoxication in these populations. Effective prevention strategies may include the monitoring of fluoride levels in natural habitats, the implementation of measures to curtail industrial fluoride emissions and the contamination of water sources, as well as educating stakeholders about the potential impacts of fluoride on wildlife. Conservation initiatives should prioritize the minimization of exposure and the mitigation of fluoride's effects on ecosystems to safeguard the health and sustainability of wildlife populations.

To address these concerns, the forestry department may implement several key actions to reduce fluoride exposure and its repercussions on wildlife (Shupe et al., 1979). A critical step involves curtailing fluoride exposure among young and pregnant wild animals. This may be accomplished by restricting grazing activities in proximity to factories that release fluoride or by relocating these animals to areas where industrial fluoride pollution is substantially lower or non-existent (Suttie et al., 1985). Furthermore, the management of fluoride emissions from industries can be enhanced through the adoption of advanced technologies designed to capture fluoride prior to its release into the environment (Swarup and Dwivedi, 2002). The defluoridation of water in areas prone to contamination represents one of the most effective mitigation strategies available (Wang et al., 2023). The cultivation of fluoride-mitigating plants, including Neem (Azadirachta indica), Arjun tree (Terminalia arjuna), Amla (Phyllanthus emblica), Tamarind (Tamarindus indica), and Banana (Musa spp.), offers a viable and natural strategy for reducing fluoride exposure among wild animals. These plant species are noted for their capability to tolerate or diminish fluoride accumulation in soil, water, and vegetation, thereby lowering the risk of fluorosis among herbivores and other wildlife.Neem contains bioactive compounds, such as Azadirachtin and Nimbin, which contribute to the neutralization of toxins and promote the excretion of fluoride (Alzohairy, 2016). The Arjun tree, with its arjunolic acid and tannins, binds fluoride, thereby reducing its absorption and assisting in its removal from the body (Dwivedi and Chopra, 2014). Amla is rich in Vitamin C and ellagic acid, functioning as an antioxidant that mitigates oxidative stress induced by fluoride while enhancing detoxification processes (Ranjan and Yasmin, 2015). Tamarind, which contains tamarindin and citric acid, facilitates the binding and excretion of fluoride (Patra et al., 2015). Collectively, these plants aid in reducing fluoride accumulation and its adverse effects, thereby promoting animal health within fluoride-contaminated environments.

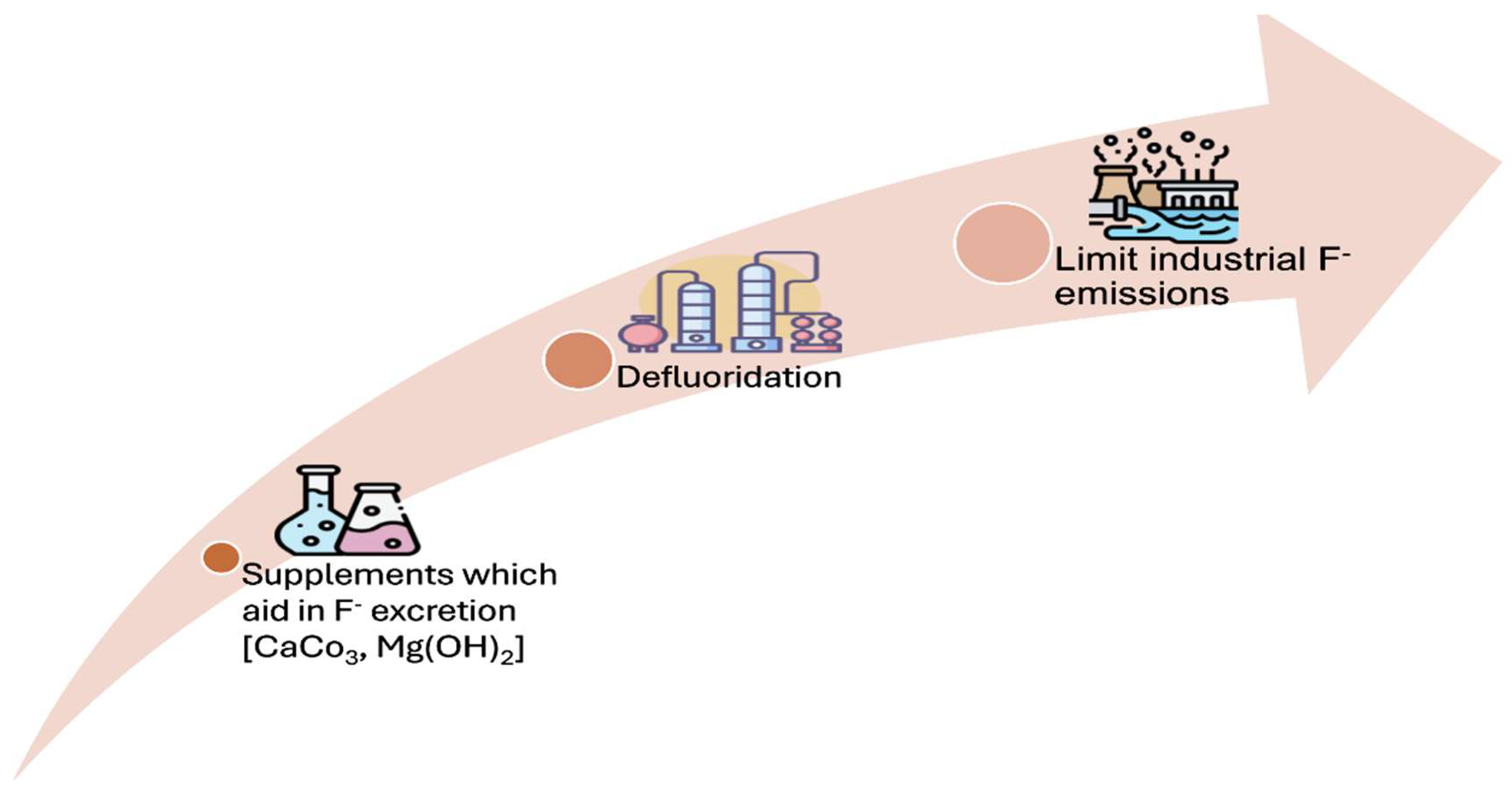

In addition, providing a balanced diet to wildlife may further alleviate the impacts of fluorosis. Strategies to mitigate fluoride toxicity could involve reducing fluoride intake or enhancing its elimination from the body. This may be achieved through the use of dietary supplements such as calcium carbonate or gluconate, aluminum salts, magnesium metasilicate, magnesium hydroxide, boron, and other compounds that promote fluoride removal or diminish its absorption (

Figure 2). These preventative measures are essential for safeguarding wildlife against the adverse effects of fluoride exposure, thereby ensuring their continued health and reproductive success in affected habitats (Choubisa et al., 2009).

Conclusion

Chronic exposure to fluoride presents significant risks to the health of wildlife and can result in a widespread condition known as fluorosis, recognized as a global concern. Excessive intake or exposure disrupts normal dental development and leads to the accumulation of fluoride in an animal’s bones throughout its life. Elevated fluoride concentrations can trigger skeletal disorders, such as osteofluorosis, more commonly referred to as skeletal fluorosis. Instances of both dental and skeletal fluorosis have been documented in various wildlife species inhabiting areas with high fluoride levels. Once the clinical signs of fluorosis become apparent in wildlife, treatment options are limited to reducing further exposure and associated risks. Given the limited research on fluoride toxicity in wildlife, there is an urgent need for comprehensive epidemiological studies. Such research should aim to enhance our understanding of fluorosis across different species of herbivorous and carnivorous wild animals, informing conservation efforts and helping to mitigate the effects of fluoride on wildlife populations.

References

- Alzohairy, M. A. Therapeutics Role of Azadirachta indica (Neem) and Their Active Constituents in Diseases Prevention and Treatment. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine: eCAM. 2016. 7382506.

- Choubisa, S.L., Choubisa, L., Choubisa, D., Osteo-dental Fluorosis in relation to nutritional status, living habits and occupation in rural areas of Rajasthan, India. Fluoride, 2009, 42(3): 210-215.

- Choubisa, S.L., Modasiya, V., Bahura, C.K., Sheikh, Z., Toxicity of fluoride in cattle of the Indian Thar Desert, Rajasthan, India. Fluoride, 2012, 45(4): 371-376.

- Choubisa, S.L. Fluorotoxicosis in Diverse Species of Domestic Animals Inhabiting Areas with High Fluoride in Drinking Water of Rajasthan, India. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, India Section B: Biological Sciences. 2013. 83.

- Choubisa, S.L., Choubisa, D., Neighbourhood Fluorosis in people residing in the vicinity of superphosphate fertilizer plants near Udaipur city of Rajasthan (India). Environ. Monit. Assess., 2015, 187(8): 497.

- Choubisa, S.L. Is it Safe for Domesticated Animals to Drink Fresh Water in the Context of Fluoride Poisoning?. 2023. Clin Res AnimSci. 3(2).

- Choubisa, S.L., Can fluoride exposure be dangerous to the health of wildlife? If so, how can they be protected from it? J. Vet. Med. Animal Sci., 2024, 7(1), 1144.

- Death, C., Coulson, G., Kierdorf, U., Kierdorf, H., Morris, W.K., Dental Fluorosis and skeletal fluoride content as biomarkers of excess fluoride exposure in marsupials. Sci. Total Environ., 2015, 533, 528-541.

- Death, C., Coulson, G., Kierdorf, U., Kierdorf, H., Ploeg, R., et al., Chronic excess fluoride uptake contributes to degenerative joint disease (DJD): Evidence from six marsupial species. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Safety, 2018, 162, 383-390.

- Dwivedi, S. & Chopra, D. (2014). Revisiting Terminalia arjuna - An Ancient Cardiovascular Drug. Journal of Traditional and Complementary Medicine, 4(4), 224–231.

- Flueck, W.T., Smith-Flueck, J.A.M., Severe dental Fluorosis in juvenile deer linked to a recent volcanic eruption in Patagonia. J. Wildl. Dis., 2013, 49(2): 355-366.

- Gehlot, Hemsingh, Jakher, G., Threats to existence of blackbuck (Antelope cervicapra) and Chinkara (Gazella bennetti) in the Thar region of Rajasthan, India. Int. J. Recent Biotechnol., 2015.

- Kanduti, D., Sterbenk, P., Artnik, B., Fluoride: A review of use and effects on health. Mater. Socio-Med., 2016, 28(2): 133.

- Kaushik, H., Forest department orders study of fluorosis among lions. The Times of India. 2014. 20-10.

- Kierdorf U, Kierdorf H, Sedlacek F, Fejerskov O. Structural changes in fluorosed dental enamel of red deer (Cervus elaphus L.) from a region with severe environmental pollution by fluorides. J Anat. 1996; 188(1): 183-195.

- Kierdorf, H., Kierdorf, U., Richards, A., Sedlacek, F., Disturbed enamel formation in wild boars (Sus scrofa L.) from fluoride polluted areas in Central Europe. Anatom. Rec., 2000, 259(1): 12-24.

- Kierdorf U, Death C, Hufschmid J, Witzel C, Kierdorf H. Developmental and post-eruptive defects in molar enamel of free-ranging eastern grey kangaroos (Macropus giganteus) exposed to high environmental levels of fluoride. PLoS One. 2016; 11(2): e0147427.

- Maiti, S.K., Das, P.K., Biochemical changes in endemic dental fluorosis in cattle. Indian J. Anim. Sci., 2004, 74(2): 169-171.

- Mohammadi, A.A., Yousefi, M., Yaseri, M., Jalilzadeh, M., Mahvi, A.H., Skeletal Fluorosis in relation to drinking water in rural areas of West Azerbaijan, Iran. Sci. Rep., 2017, 7(1): 17300.

- Pradhan, B.C., Baral, M., Pradhan, S.P., Pradhan, D., Assessment of fluoride in milk samples of domestic animals around Nalco, Angul Odisha, India. Int. J. Pharm. Sci. Res., 2016, (4): 29-40.

- Ranjan, R., Ranjan, A., Toxic Effects. In Fluoride Toxicity in Animals, Springer Int. Publ., 2015, pp. 35-51.

- Ranjan, S. & Yasmin, S. Amelioration of Fluoride Toxicity Using Amla (Emblica officinalis). Current Science, 108(11).2015. 2094–2098.

- Roy, M., Verma, R.K., Roy, S., Roopali, B., Geographical distribution of fluoride and its effect on animal health. Int. J. Curr. Microbiol. App. Sci., 2018, 7(3): 2871-2877.

- Samal, P., Patra, R. C., Gupta, A. R., Mishra, S. K., Jena, D. & Satapathy, D. Effect of Tamarindus indica Leaf Powder on Plasma Concentrations of Copper, Zinc, and Iron in Fluorotic Cows. Veterinary World, 9(10). 2016, 1121–1124.

- Shanmugam, T., Selvaraj, M., Sources of human overexposure to fluoride, its toxicities, and their amelioration using natural antioxidants. Fluoride, 2022, IntechOpen.

- Shaw, S.D., Bishop, P.J., Harvey, C., Berger, L., Skerratt, L.F., et al., fluorosis as a probable factor in metabolic bone disease in captive New Zealand native frogs (Leiopelma species). J. Zoo Wildl. Med., 2012, 43(3): 549-565.

- Shupe, J.L., Clinicopathologic features of fluoride toxicosis in cattle. J. Anim. Sci., 1980, 51(3): 746-758.

- Shupe JL, Olson AE, Peterson HB, Low JB. Fluoride toxicosis in wild ungulates. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1984; 185(11): 1295-300.

- Suttie, J.W., Hamilton, R.J., Clay, A.C., Tobin, M.L., Moore, W.G., Effects of fluoride ingestion on white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus). J. Wildl. Dis., 1985, 21(3): 283-288.

- Suttie JS, Dickie R, Clay AB, Nielsen P, Mahan WE, Baumann DP, Hamilton RJ. Effects of fluoride emissions from a modern primary aluminum smelter on a local population of white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus). J. Wildl. Dis. 1987, Jan; 23(1):135-43.

- Swarup, D., Dwivedi, K., Environmental pollution and effect of lead and fluoride on animal health. Indian Council of Agricultural Research, New Delhi, 2002, pp. 68-106.

- Talpur, B.R., Nizamani, Z.A., Leghari, I.H., Tariq, M., Rehman, A., Kumbhar, S., Hepato-nephrotoxic effects of induced fluorosis in rabbits and broilers. J. Anim. Health Prod., 2022, 10(2): 214-220.

- Vikøren, Turid. ESPIAL Fauna - Current state for fluoride exposure of animals in the vicinity of aluminium smelters. VI report. Veterinærinstituttet 2021.

- Walton KC. Tooth damage in field voles, wood mice and moles in areas polluted by fluoride from an aluminium reduction plant. Sci. Total Environ. 1987; 65 Choubisa SL, Choubisa L, Choubisa D. Osteo-dental fluorosis in relation to nutritional status, living habits and occupation in rural areas of Rajasthan, India. Fluoride. 2009; 42(3): 210-215. 257-260.

- Wang, F., Li, Y., Tang, D., Zhao, J., Yang, B., Zhang, C., Su, M., He, Z., Zhu, X., Ming, D., & Liu, Y. Epidemiological analysis of drinking water-type fluorosis areas and the impact of fluorosis on children's health in the past 40 years in China. Environ. Geochem. Health, 2023. 45(12): 9925–9940.

- Weinstein, L.H., Davison, A., Native plant species suitable as bioindicators and biomonitors for airborne fluoride. Environ. Pollut., 2003, 125(1): 3-11.

- Whitford, G.M., The metabolism and toxicity of fluoride. Monographs in Oral Science, Karger: Basel, 1996, 16.

- Zhou, J., Gao, J., Liu, Y., Ba, K., Chen, S., Zhang, R., Removal of fluoride from water by five submerged plants. Bull. Environ. Contam. Toxicol., 2012, 1-5.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).