Submitted:

28 December 2024

Posted:

30 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Surface Preparation

2.2. Surface Characterization

2.3. Calcium Assay

2.4. Bacterial Strains and Culture

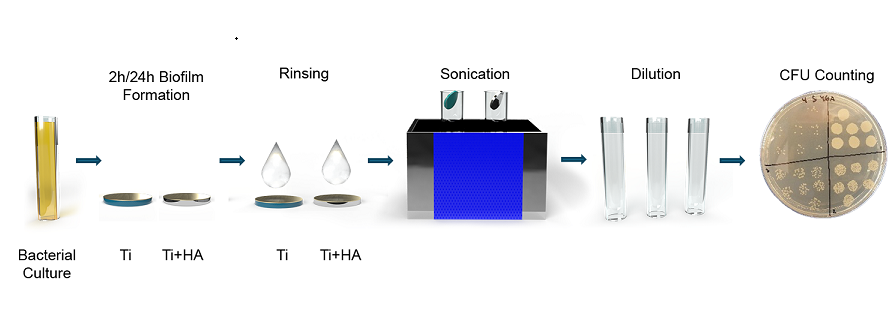

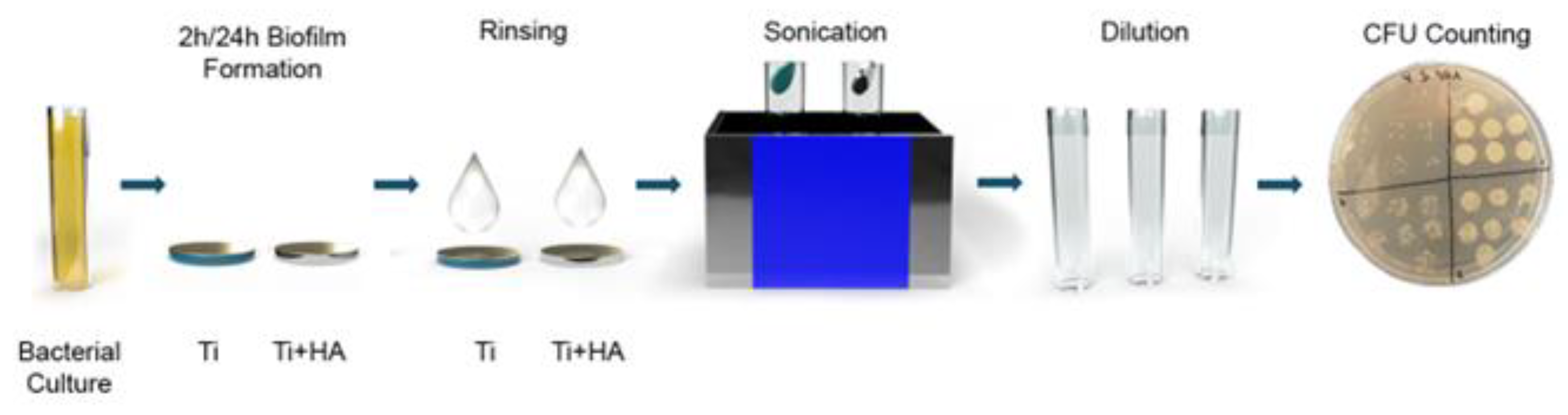

2.5. Biofilm Assay

2.6. Confocal Microscopy

2.7. Statistical analysis

3. Results

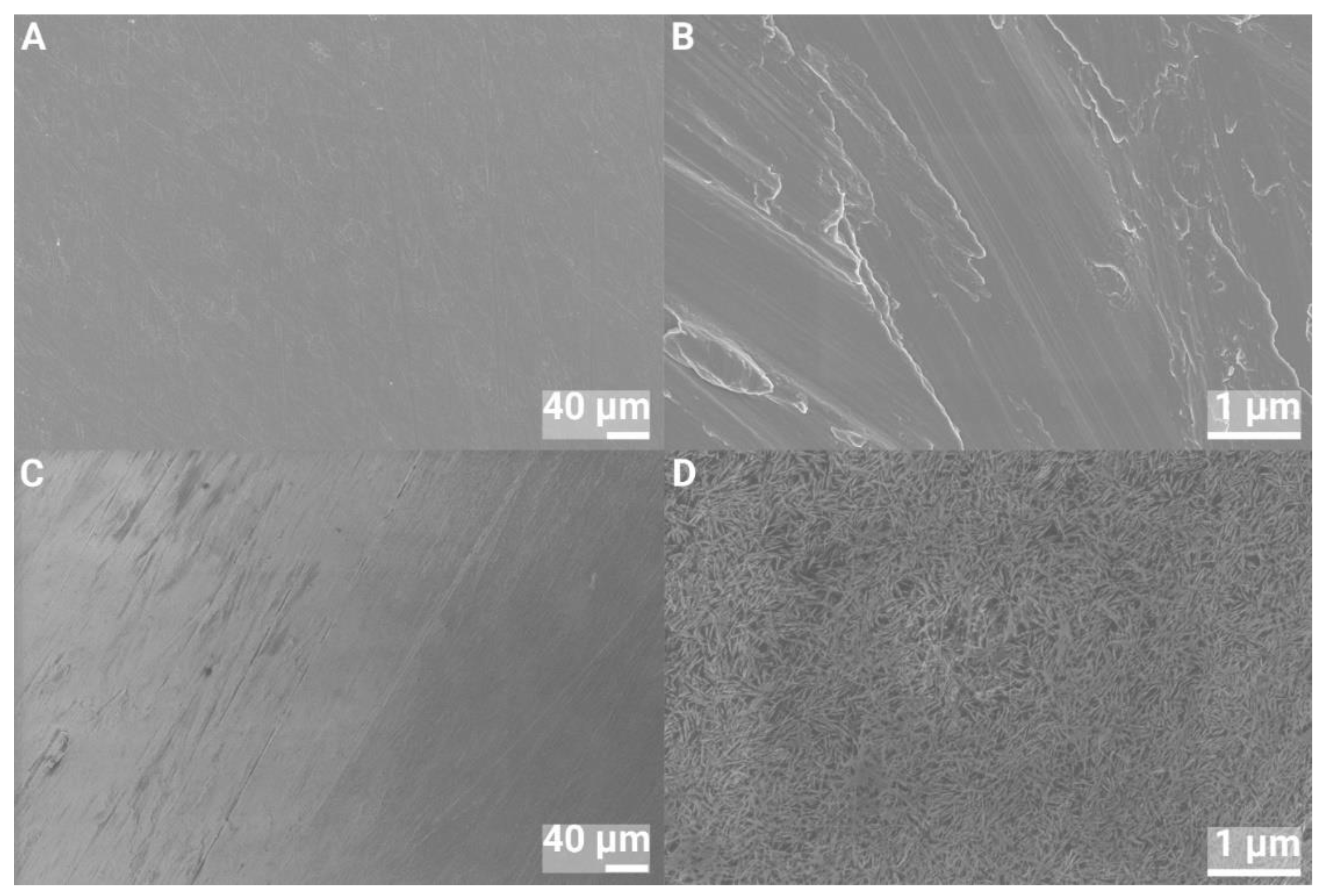

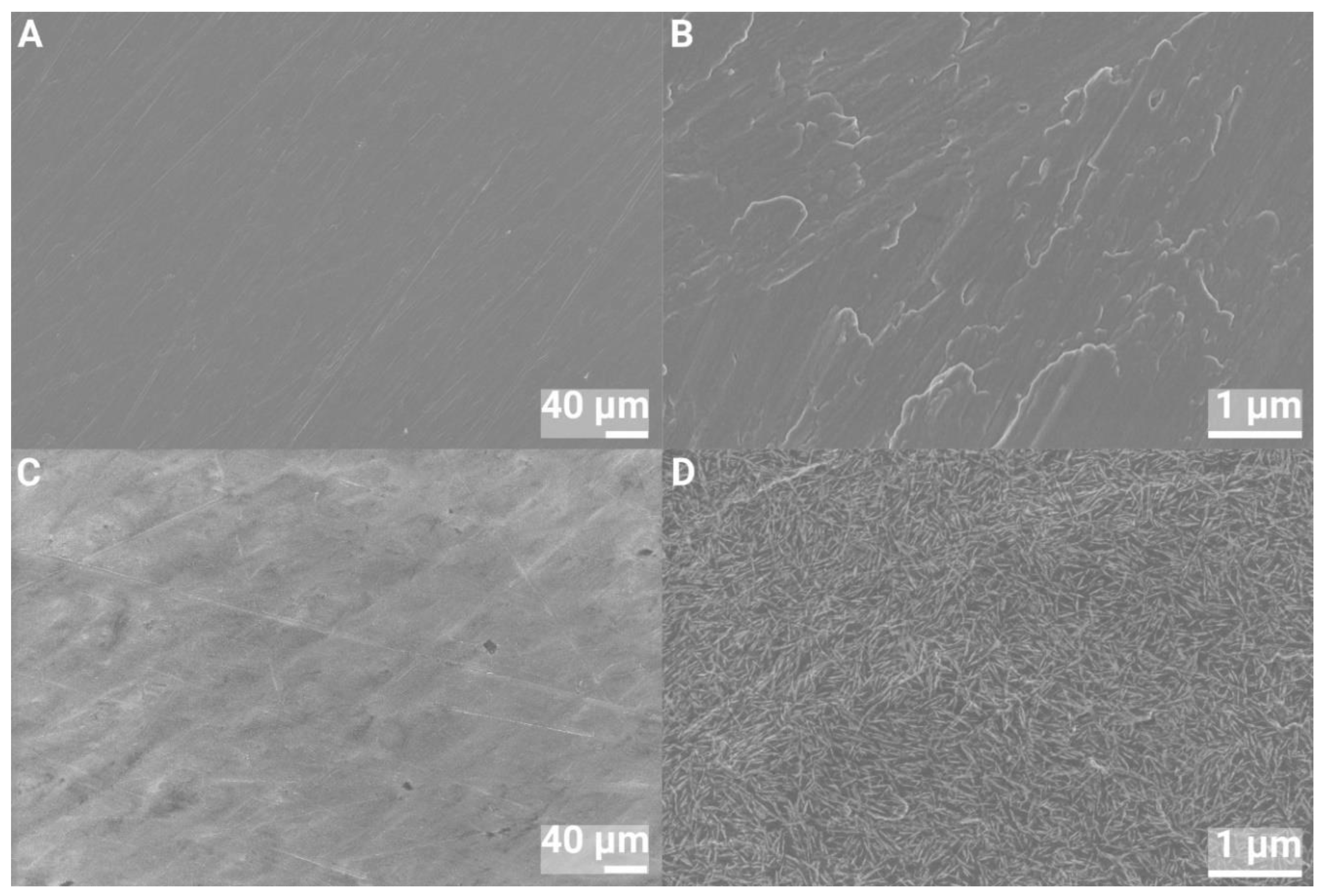

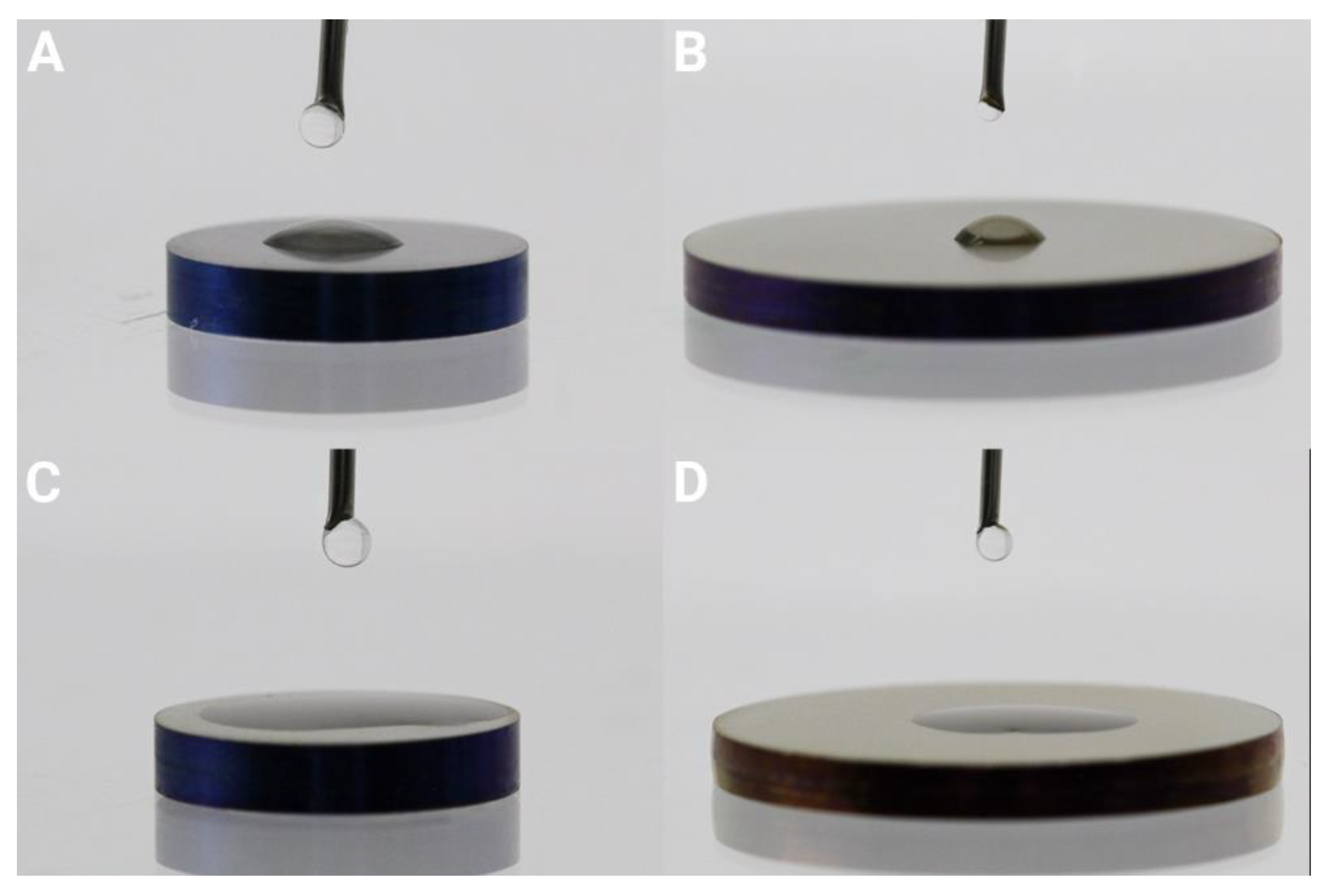

3.1. Surface Characterization

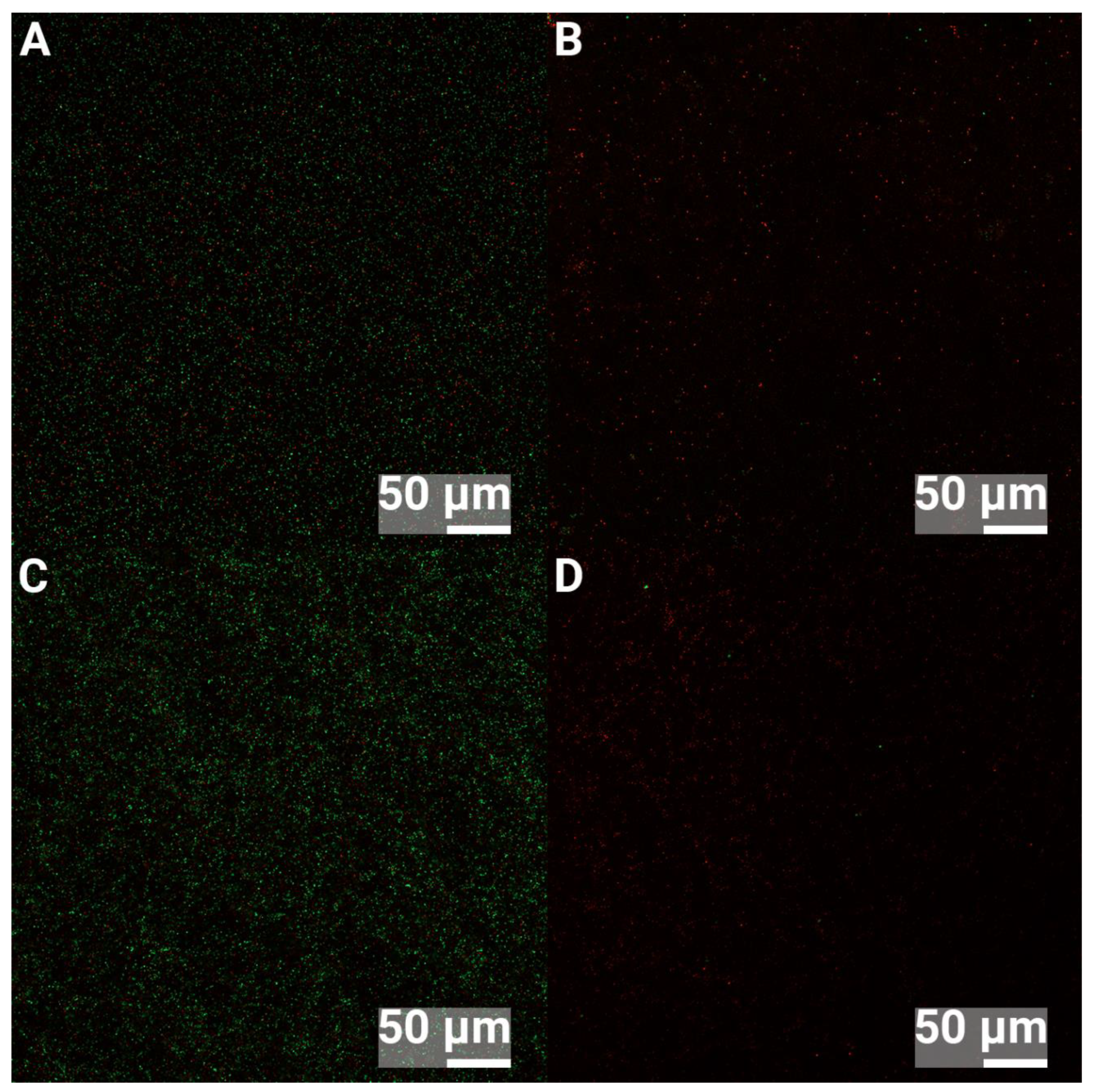

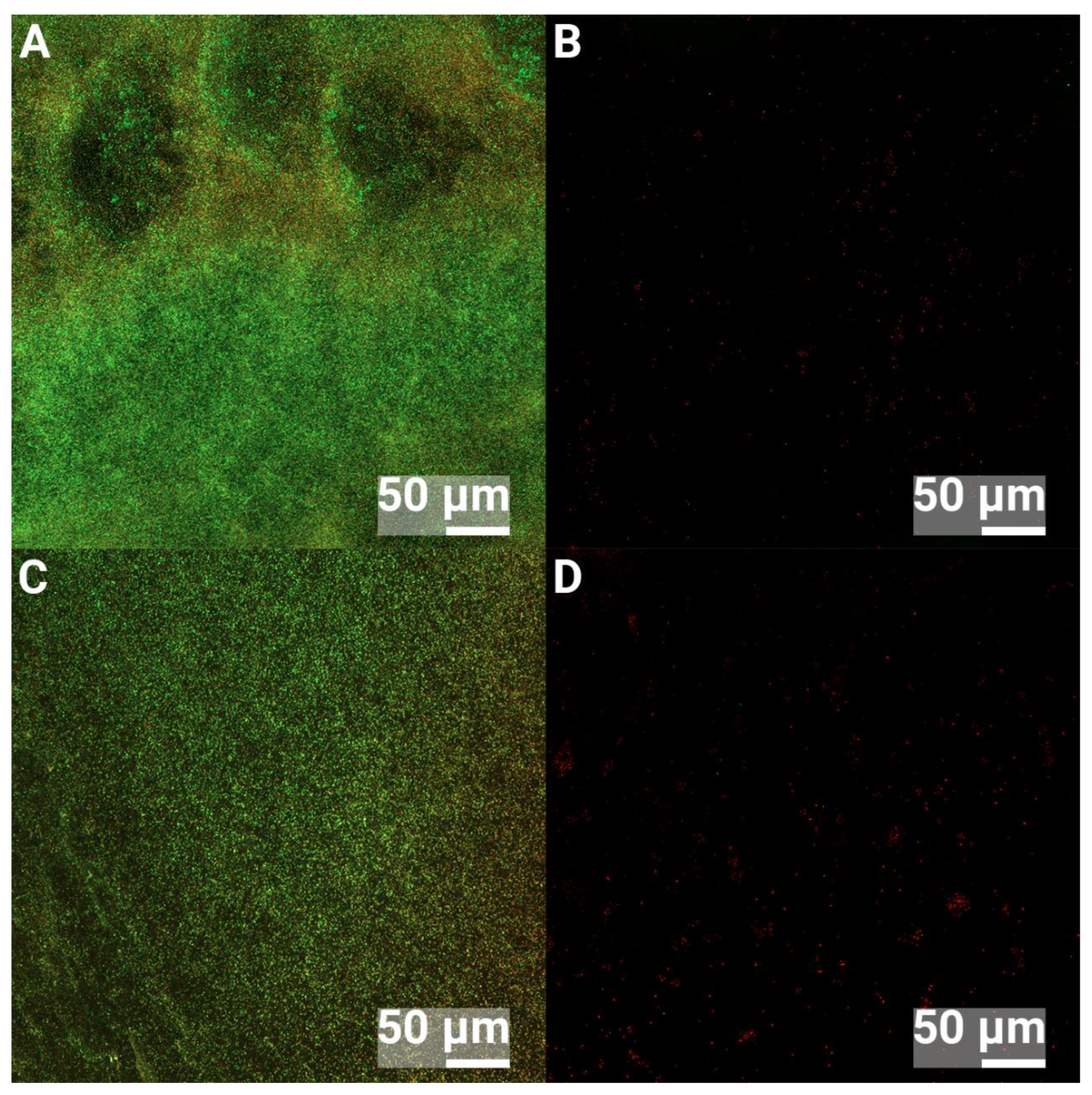

3.2. Confocal Microscopy

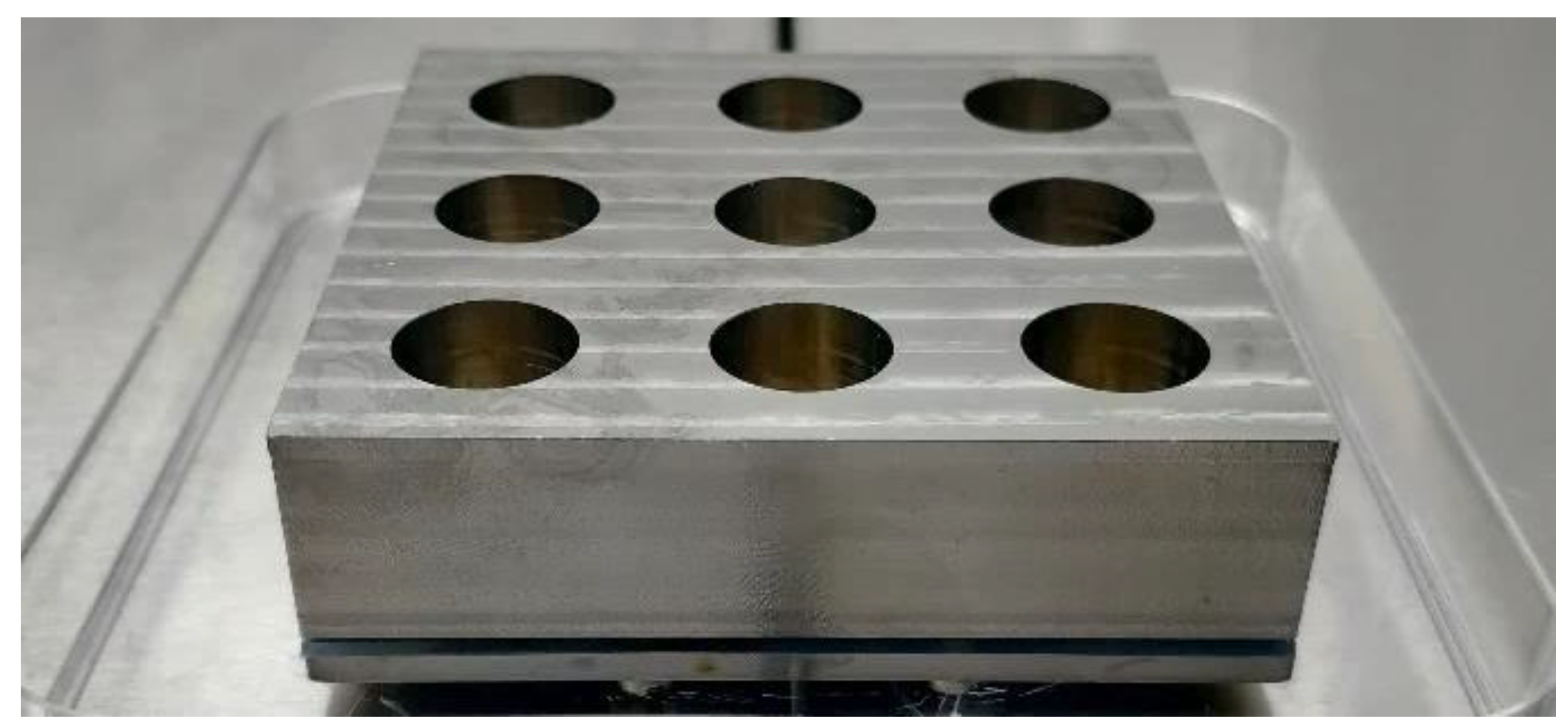

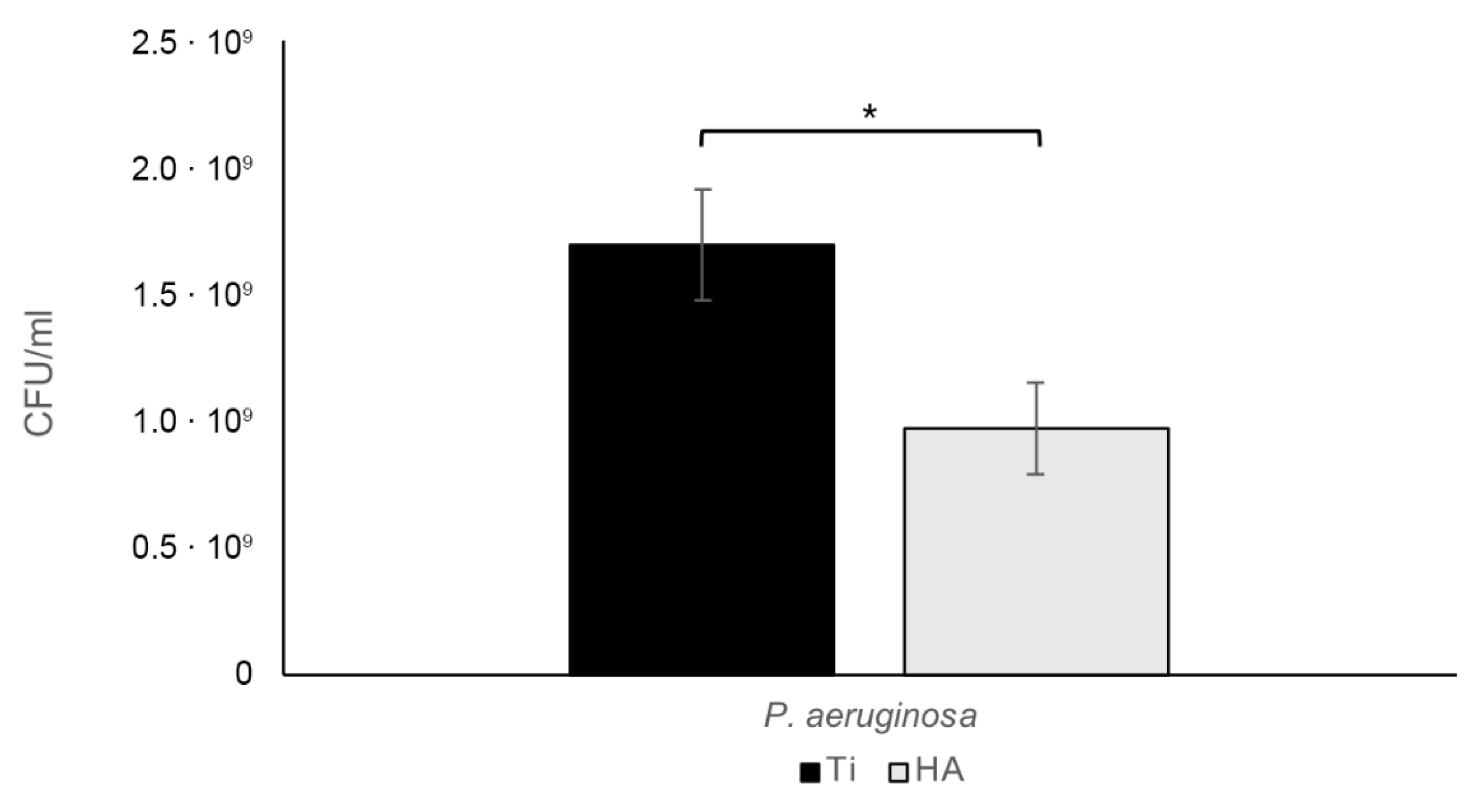

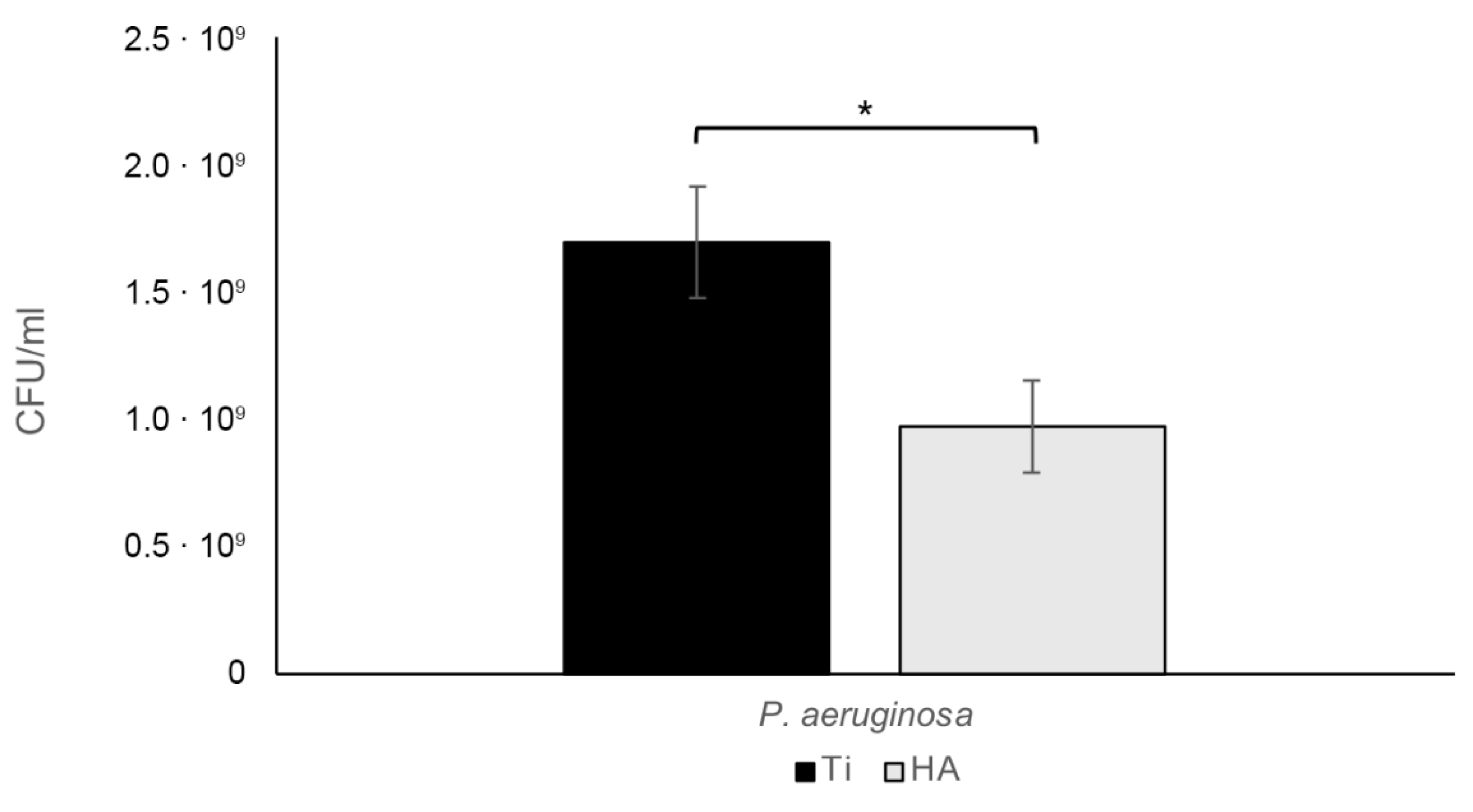

3.3. Biofilm Assay

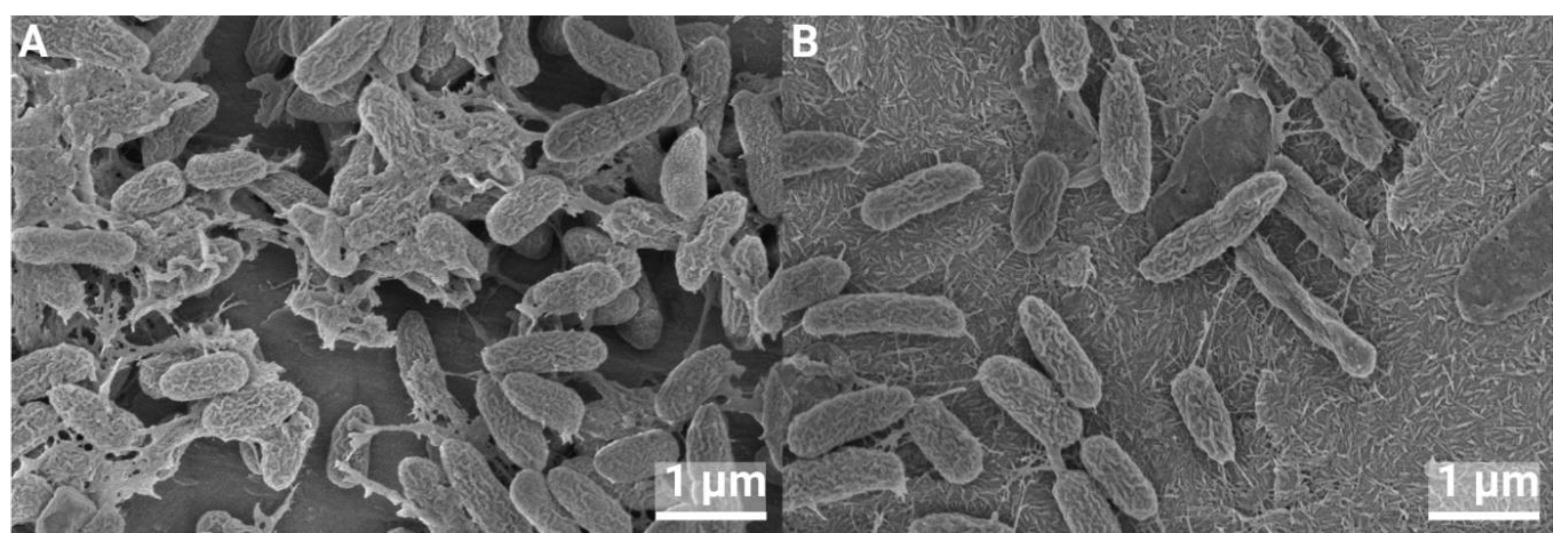

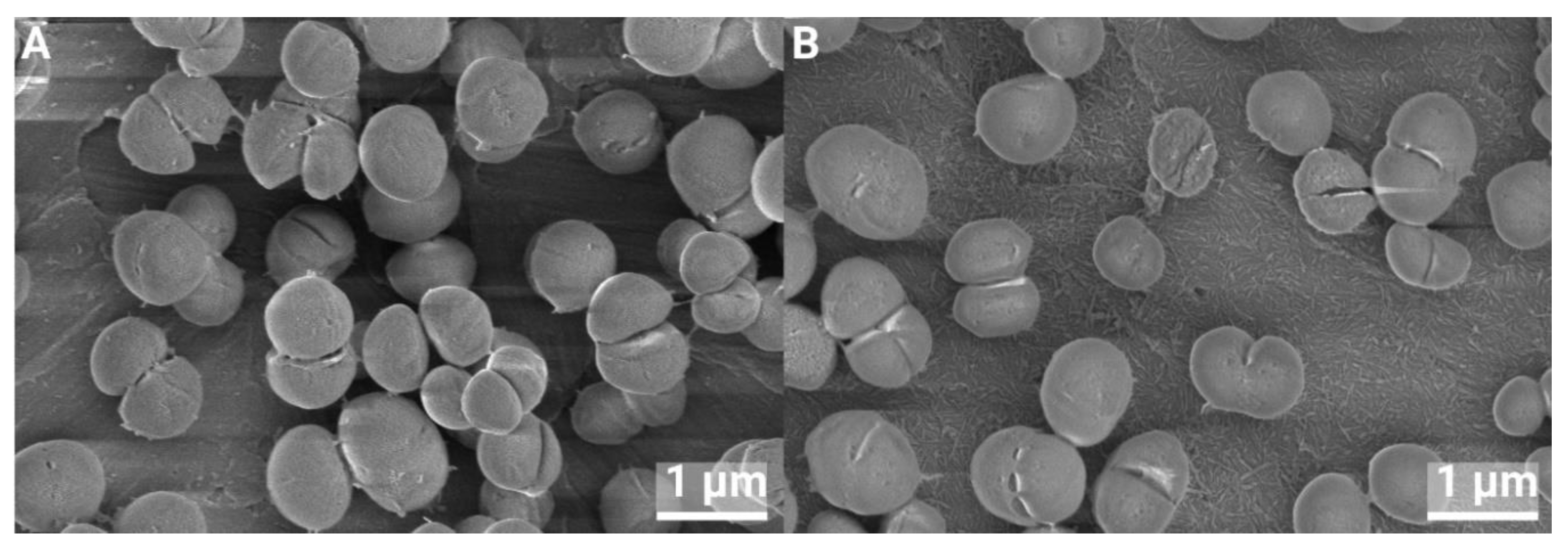

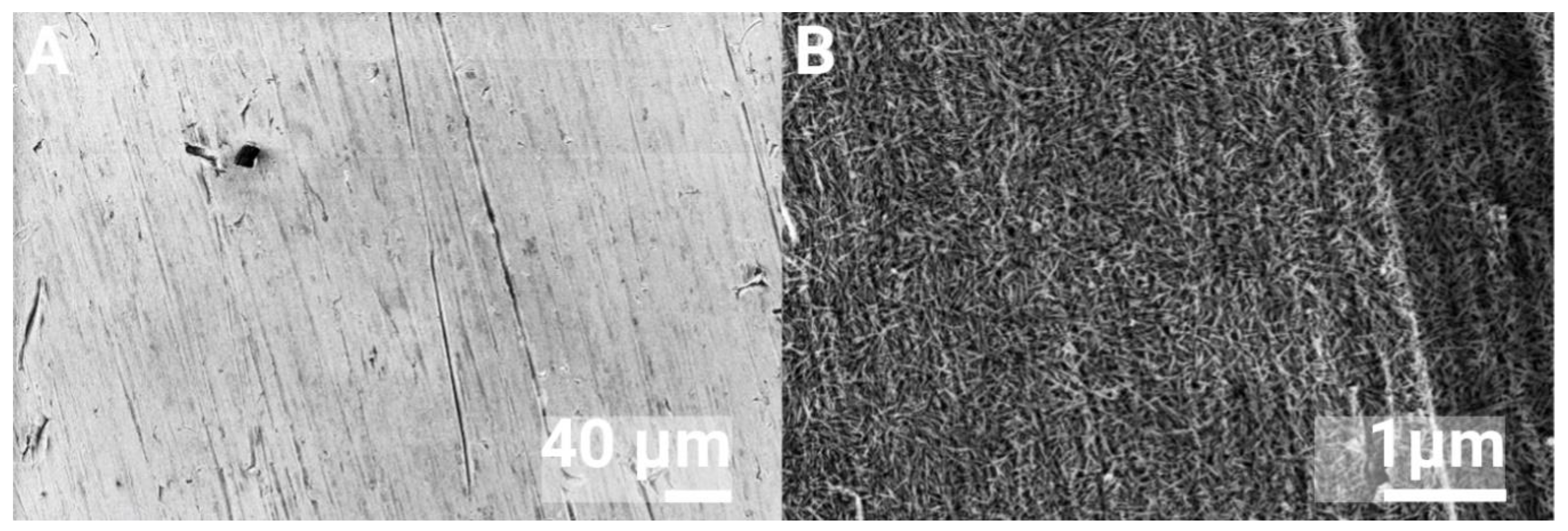

3.4. SEM of BIOFILMS

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aggarwal, V.K., M.R. Rasouli, and J. Parvizi, Periprosthetic joint infection: Current concept. Indian J Orthop, 2013. 47(1): p. 10-7. [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.W., et al., Clinical differences between delayed and acute onset postoperative spinal infection. Medicine (Baltimore), 2022. 101(24): p. e29366. [CrossRef]

- Clark, C.E. and H.L. Shufflebarger, Late-developing infection in instrumented idiopathic scoliosis. Spine (Phila Pa 1976), 1999. 24(18): p. 1909-12. [CrossRef]

- Parchi, P.D., et al., Postoperative Spine Infections. Orthop Rev (Pavia), 2015. 7(3): p. 5900. [CrossRef]

- Köder, K., et al., Outcome of spinal implant-associated infections treated with or without biofilm-active antibiotics: results from a 10-year cohort study. Infection, 2020. 48(4): p. 559-568. [CrossRef]

- Dapunt, U., et al., Surgical site infections following instrumented stabilization of the spine. Ther Clin Risk Manag, 2017. 13: p. 1239-1245. [CrossRef]

- Guo, G., et al., Distribution characteristics of Staphylococcus spp. in different phases of periprosthetic joint infection: A review. Exp Ther Med, 2017. 13: p. 2599 - 2608.

- Arciola, C.R., D. Campoccia, and L. Montanaro, Implant infections: adhesion, biofilm formation and immune evasion. Nat Rev Microbiol, 2018. 16(7): p. 397-409. [CrossRef]

- Sampedro, M.F., et al., A biofilm approach to detect bacteria on removed spinal implants. Spine (Phila Pa 1976), 2010. 35(12): p. 1218-24. [CrossRef]

- Elek, S.D. and P.E. Conen, The virulence of Staphylococcus pyogenes for man; a study of the problems of wound infection. Br J Exp Pathol, 1957. 38(6): p. 573-86.

- Zimmerli, W., et al., Pathogenesis of foreign body infection: description and characteristics of an animal model. J Infect Dis, 1982. 146(4): p. 487-97. [CrossRef]

- Poelstra, K.A., et al., A novel spinal implant infection model in rabbits. Spine (Phila Pa 1976), 2000. 25(4): p. 406-10. [CrossRef]

- Laratta, J.L., et al., A Dose-Response Curve for a Gram-Negative Spinal Implant Infection Model in Rabbits. Spine (Phila Pa 1976), 2017. 42(21): p. E1225-e1230. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y., et al., Animal Models for Postoperative Implant-Related Spinal Infection. Orthop Surg, 2022. 14(6): p. 1049-1058. [CrossRef]

- Alomar, A.Z., et al., INTRAOPERATIVE EVALUATION AND LEVEL OF CONTAMINATION DURING TOTAL KNEE ARTHROPLASTY. Acta Ortop Bras, 2022. 30(spe1): p. e243232. [CrossRef]

- Khajanchi, B.K., et al., Immunomodulatory and protective roles of quorum-sensing signaling molecules N-acyl homoserine lactones during infection of mice with Aeromonas hydrophila. Infect Immun, 2011. 79(7): p. 2646-57. [CrossRef]

- Thurlow, L.R., et al., Staphylococcus aureus biofilms prevent macrophage phagocytosis and attenuate inflammation in vivo. J Immunol, 2011. 186(11): p. 6585-96. [CrossRef]

- Hanke, M.L., A. Angle, and T. Kielian, MyD88-dependent signaling influences fibrosis and alternative macrophage activation during Staphylococcus aureus biofilm infection. PLoS One, 2012. 7(8): p. e42476. [CrossRef]

- Kristian, S.A., et al., Biofilm formation induces C3a release and protects Staphylococcus epidermidis from IgG and complement deposition and from neutrophil-dependent killing. J Infect Dis, 2008. 197(7): p. 1028-35. [CrossRef]

- Belgiovine, C., et al., Interaction of Bacteria, Immune Cells, and Surface Topography in Periprosthetic Joint Infections. Int J Mol Sci, 2023. 24(10). [CrossRef]

- Tucci, G., et al., Prevention of surgical site infections in orthopaedic surgery: a synthesis of current recommendations. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci, 2019. 23(2 Suppl): p. 224-239. [CrossRef]

- Milleret, V., et al., Rational design and in vitro characterization of novel dental implant and abutment surfaces for balancing clinical and biological needs. Clin Implant Dent Relat Res, 2019. 21 Suppl 1: p. 15-24. [CrossRef]

- Jeong, W.S., et al., Bacterial attachment on titanium surfaces is dependent on topography and chemical changes induced by nonthermal atmospheric pressure plasma. Biomed Mater, 2017. 12(4): p. 045015. [CrossRef]

- Skovdal, S.M., et al., Ultra-dense polymer brush coating reduces Staphylococcus epidermidis biofilms on medical implants and improves antibiotic treatment outcome. Acta Biomater, 2018. 76: p. 46-55. [CrossRef]

- Subramani, K., et al., Biofilm on dental implants: a review of the literature. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants, 2009. 24(4): p. 616-26.

- Savarino, L., et al., Biologic effects of surface roughness and fluorhydroxyapatite coating on osteointegration in external fixation systems: An in vivo experimental study. J Biomed Mater Res A, 2003. 66A(3): p. 652-661. [CrossRef]

- Scheeren Brum, R., et al., Early Biofilm Formation on Rough and Smooth Titanium Specimens: a Systematic Review of Clinical Studies. J Oral Maxillofac Res, 2021. 12(4): p. e1. [CrossRef]

- Saulacic, N. and B. Schaller, Prevalence of Peri-Implantitis in Implants with Turned and Rough Surfaces: a Systematic Review. J Oral Maxillofac Res, 2019. 10(1): p. e1. [CrossRef]

- Zeller, B., et al., Biofilm formation on metal alloys, zirconia and polyetherketoneketone as implant materials in vivo. Clin Oral Implants Res, 2020. 31(11): p. 1078-1086. [CrossRef]

- Meier, D., et al., Biofilm formation on metal alloys and coatings, zirconia, and hydroxyapatite as implant materials in vivo. Clin Oral Implants Res, 2023. 34(10): p. 1118-1126. [CrossRef]

- Hegde, V., et al., The Use of a Novel Antimicrobial Implant Coating In Vivo to Prevent Spinal Implant Infection. Spine (Phila Pa 1976), 2020. 45(6): p. E305-e311. [CrossRef]

- D'Almeida, M., et al., Chitosan coating as an antibacterial surface for biomedical applications. PLoS One, 2017. 12(12): p. e0189537. [CrossRef]

- Asri, L.A.T.W., et al., A Shape-Adaptive, Antibacterial-Coating of Immobilized Quaternary-Ammonium Compounds Tethered on Hyperbranched Polyurea and its Mechanism of Action. Adv Funct Mater, 2014. 24(3): p. 346-355. [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y., et al., Nanostructured titanium surfaces exhibit recalcitrance towards Staphylococcus epidermidis biofilm formation. Sci Rep, 2018. 8(1): p. 1071. [CrossRef]

- Albrektsson, T. and A. Wennerberg, On osseointegration in relation to implant surfaces. Clin Implant Dent Relat Res, 2019. 21 Suppl 1: p. 4-7. [CrossRef]

- Voigt, J.D. and M. Mosier, Hydroxyapatite (HA) coating appears to be of benefit for implant durability of tibial components in primary total knee arthroplasty. Acta Orthop, 2011. 82(4): p. 448-59. [CrossRef]

- Vidalain, J.P., Twenty-year results of the cementless Corail stem. Int Orthop, 2011. 35(2): p. 189-94. [CrossRef]

- Røkkum, M., A. Reigstad, and C.B. Johansson, HA particles can be released from well-fixed HA-coated stems: histopathology of biopsies from 20 hips 2-8 years after implantation. Acta Orthop Scand, 2002. 73(3): p. 298-306. [CrossRef]

- Overgaard, S., et al., Improved fixation of porous-coated versus grit-blasted surface texture of hydroxyapatite-coated implants in dogs. Acta Orthop Scand, 1997. 68(4): p. 337-43. [CrossRef]

- Nunes, F., et al., Effect of Smoke Exposure on Gene Expression in Bone Healing around Implants Coated with Nanohydroxyapatite. Nanomaterials (Basel), 2022. 12(21). [CrossRef]

- Adam, M., et al., In vivo and in vitro investigations of a nanostructured coating material - a preclinical study. Int J Nanomedicine, 2014. 9: p. 975-84. [CrossRef]

- Johansson, P., et al., Nanosized Hydroxyapatite Coating on PEEK Implants Enhances Early Bone Formation: A Histological and Three-Dimensional Investigation in Rabbit Bone. Materials (Basel), 2015. 8(7): p. 3815-3830. [CrossRef]

- Almeida, D., et al., In vivo osseointegration evaluation of implants coated with nanostructured hydroxyapatite in low density bone. PLoS One, 2023. 18(2): p. e0282067. [CrossRef]

- Bergamo, E.T.P., et al., Osseointegration of implant surfaces in metabolic syndrome and type-2 diabetes mellitus. J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater, 2024. 112(2): p. e35382. [CrossRef]

- Johansson, P., et al., Polyether ether ketone implants achieve increased bone fusion when coated with nano-sized hydroxyapatite: a histomorphometric study in rabbit bone. Int J Nanomedicine, 2016. 11: p. 1435-42. [CrossRef]

- Moris, V., et al., What is the best technic to dislodge Staphylococcus epidermidis biofilm on medical implants? BMC Microbiol, 2022. 22(1): p. 192. [CrossRef]

- Karbysheva, S., et al., Comparison of sonication with chemical biofilm dislodgement methods using chelating and reducing agents: Implications for the microbiological diagnosis of implant associated infection. PLoS One, 2020. 15(4): p. e0231389. [CrossRef]

- Guerreiro-Tanomaru, J.M., et al., Effect of addition of nano-hydroxyapatite on physico-chemical and antibiofilm properties of calcium silicate cements. J Appl Oral Sci, 2016. 24(3): p. 204-10. [CrossRef]

- Lamkhao, S., et al., Synthesis of Hydroxyapatite with Antibacterial Properties Using a Microwave-Assisted Combustion Method. Sci Rep, 2019. 9(1): p. 4015. [CrossRef]

- Ragab, H., et al., Synthesis and In Vitro Antibacterial Properties of Hydroxyapatite Nanoparticles. IOSR J Pharm Biol Sci, 2014. 9: p. 77-85. [CrossRef]

- Park, M., J.B. Sutherland, and F. Rafii, Effects of nano-hydroxyapatite on the formation of biofilms by Streptococcus mutans in two different media. Arch Oral Biol, 2019. 107: p. 104484. [CrossRef]

- Grenho, L., et al., Adhesion of Staphylococcus aureus, Staphylococcus epidermidis, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa onto nanohydroxyapatite as a bone regeneration material. J Biomed Mater Res A, 2012. 100(7): p. 1823-30. [CrossRef]

- Abdulkareem, E.H., et al., Anti-biofilm activity of zinc oxide and hydroxyapatite nanoparticles as dental implant coating materials. J Dent, 2015. 43(12): p. 1462-1469. [CrossRef]

- Zakrzewski, W., et al., Antimicrobial Properties and Cytotoxic Effect Evaluation of Nanosized Hydroxyapatite and Fluorapatite Dedicated for Alveolar Bone Regeneration. Appl Sci, 2024. 14(17): p. 7845.

- Whyte, W., et al., Suggested bacteriological standards for air in ultraclean operating rooms. Journal of Hospital Infection, 1983. 4(2): p. 133-139. [CrossRef]

- Lidwell, O.M., Airborne bacteria and surgical infection. The American Journal of Medicine, 1981. 70(3): p. 693-697. [CrossRef]

- Stocks, G.W., et al., Predicting bacterial populations based on airborne particulates: A study performed in nonlaminar flow operating rooms during joint arthroplasty surgery. American Journal of Infection Control, 2010. 38(3): p. 199-204. [CrossRef]

- Guarch-Pérez, C., et al., Bacterial reservoir in deeper skin is a potential source for surgical site and biomaterial-associated infections. Journal of Hospital Infection, 2023. 140: p. 62-71. [CrossRef]

- Granato, R., et al., Clinical, histological, and nanomechanical parameters of implants placed in healthy and metabolically compromised patients. J Dent, 2020. 100: p. 103436. [CrossRef]

- Baskar, K., T. Anusuya, and G. Devanand Venkatasubbu, Mechanistic investigation on microbial toxicity of nano hydroxyapatite on implant associated pathogens. Mat Sci Eng C, 2017. 73: p. 8-14. [CrossRef]

- Knabel, S.J., H.W. Walker, and P.A. Hartman, Inhibition of Aspergillus flavus and Selected Gram-positive Bacteria by Chelation of Essential Metal Cations by Polyphosphates. J Food Prot, 1991. 54(5): p. 360-365. [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y. and L. Yang, Calcium and Magnesium Ions Are Membrane-Active against Stationary-Phase Staphylococcus aureus with High Specificity. Sci Rep, 2016. 6(1): p. 20628. [CrossRef]

- Shao, H., et al., Advances in the superhydrophilicity-modified titanium surfaces with antibacterial and pro-osteogenesis properties: A review. Front Bioeng Biotechnol, 2022. 10: p. 1000401. [CrossRef]

- Kinnari, T.J., et al., Influence of surface porosity and pH on bacterial adherence to hydroxyapatite and biphasic calcium phosphate bioceramics. J Med Microbiol, 2009. 58(Pt 1): p. 132-137. [CrossRef]

| Element | C | O | Ti | Ca | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ti grade 4 | 3.13±0.23 | 12.90±0.45 | 83.97 ± 0.61 | - | - |

| nanoHA, Ti grade 4 | 2.06±0.25 | 28.09±1.09 | 69.11 ± 1.58 | 0.42±0.15 | 0.32±0.13 |

| Ti grade 2, heated 450 °C | 2.65±0.13 | 25.61±1.41 | 71.74±1.46 | - | - |

| nanoHA, Ti grade 2 | 1.75±0.19 | 30.09±1.25 | 67.72±1.28 | 0.25±0.04 | 0.19± 0.05 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).